By Anne Farndale

Dedicated to my dearest grandchildren, Jamie and Sarah.

This was a very long time before you were born.

“A cluster of Summer trees,

a glimpse of the sea,

A pale evening moon.”

Kobori Enshiu

K

K

Kobori Enshū, 小堀 遠州 (1579 to 12 March 1647) was a Japanese aristocrat, garden designer, painter, poet, and tea master during the reign of Tokugawa Ieyasu. He excelled in the arts of painting, poetry, Ikebana flower arrangement, and Japanese garden design. He was known best as a master of the tea ceremony. His style soon on became known as "Enshū-ryū". In light of his ability, he was tasked with teaching the 3rd Tokugawa shōgun, Tokugawa Iemitsu the ways of tea ceremony. In this role, he designed many tea houses including the Bōsen-seki in the subtemple of Kohō-an at the Daitoku-ji, and the Mittan-seki at the Ryūkō-in of the same temple as well as the Hassō-an.

A Cluster of summer trees was his haiku poem about a meandering garden path. The haiku followed strict rules. Not only must it be expressed in seventeen syllables but there are a number of traditional restrictions of the subject matter. Haiku must always be written in harmony with the current seasons of the year, and there is a strong tendency to adhere to certain customary themes; certain flowers, trees, insects, animals, festivals and landscape being the usual occasions of the poems.

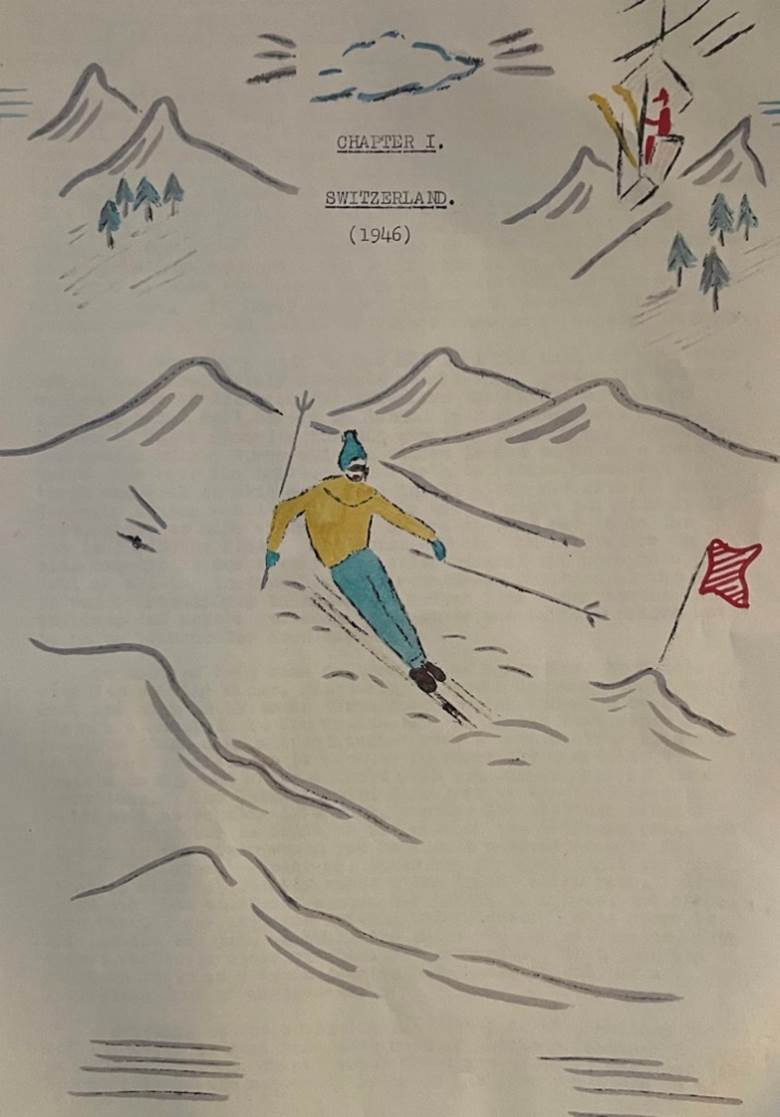

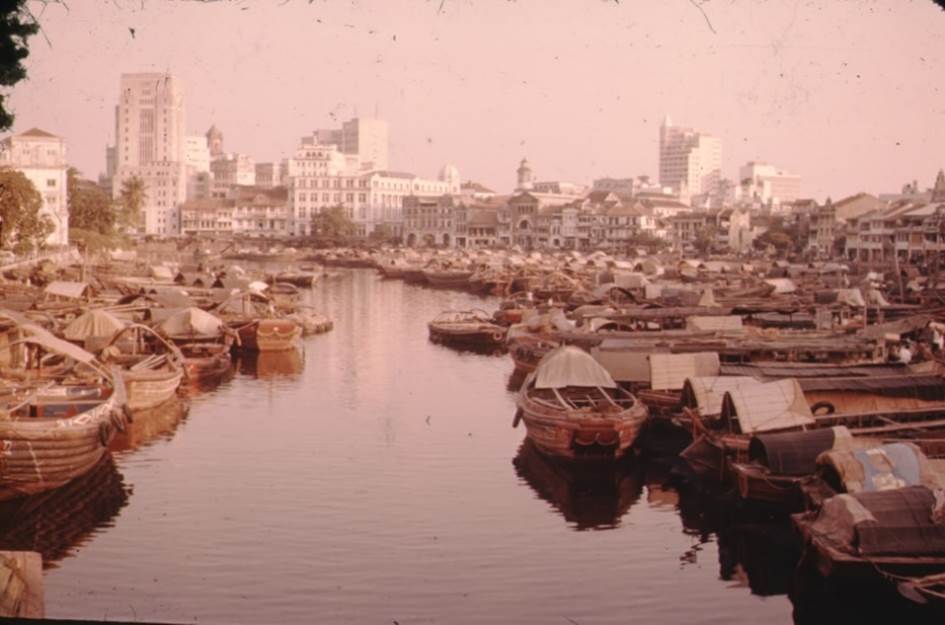

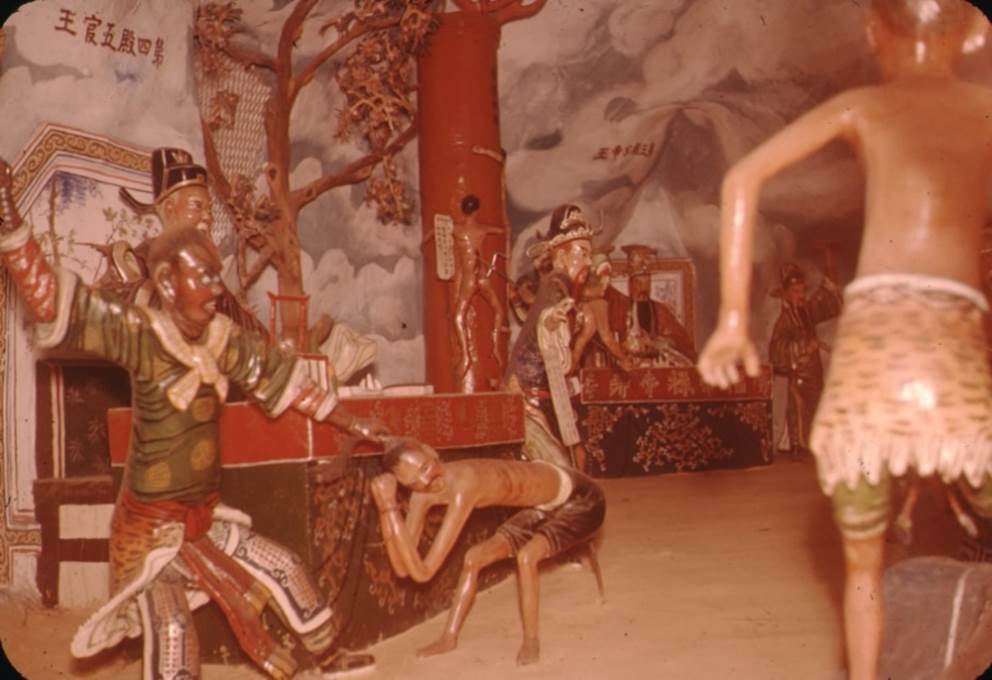

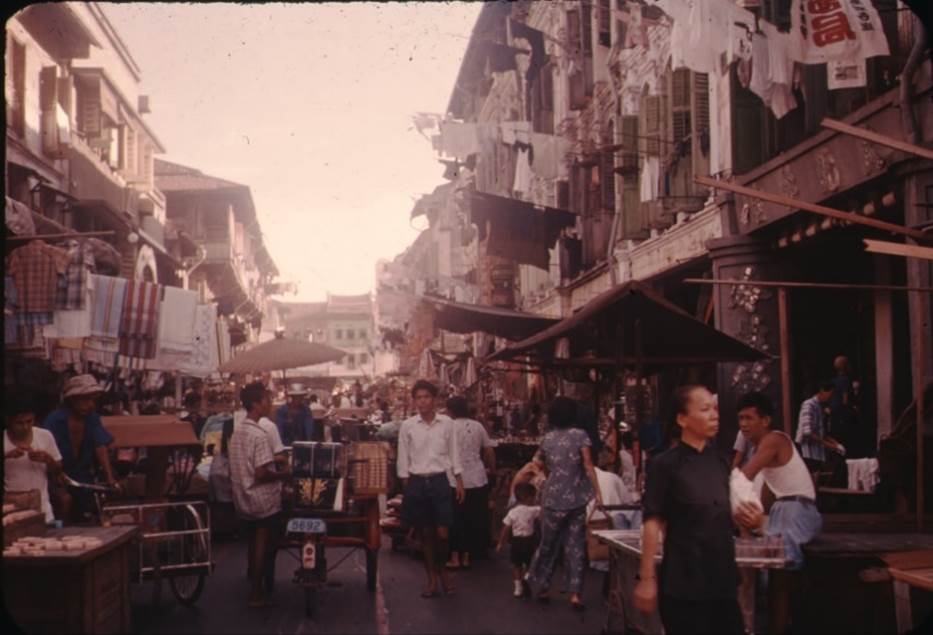

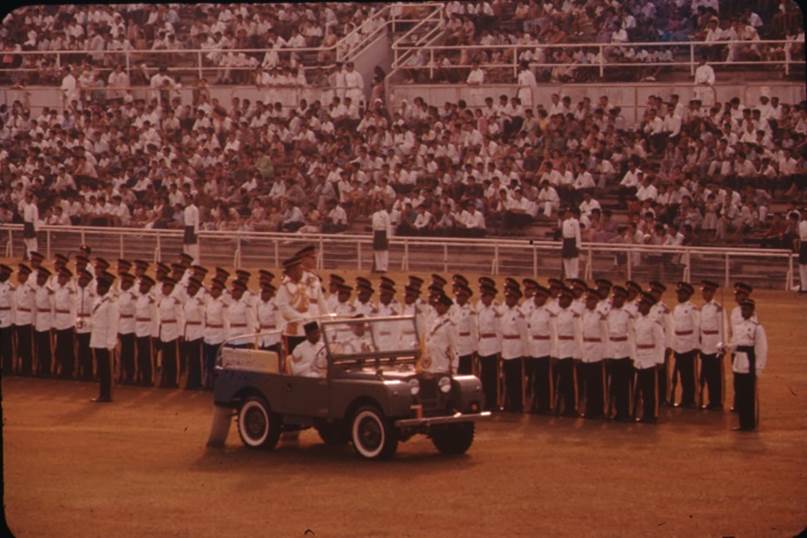

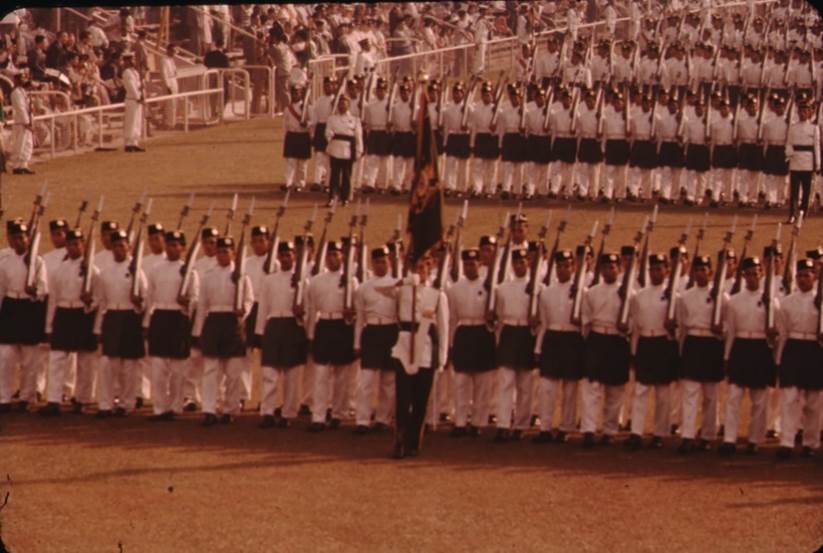

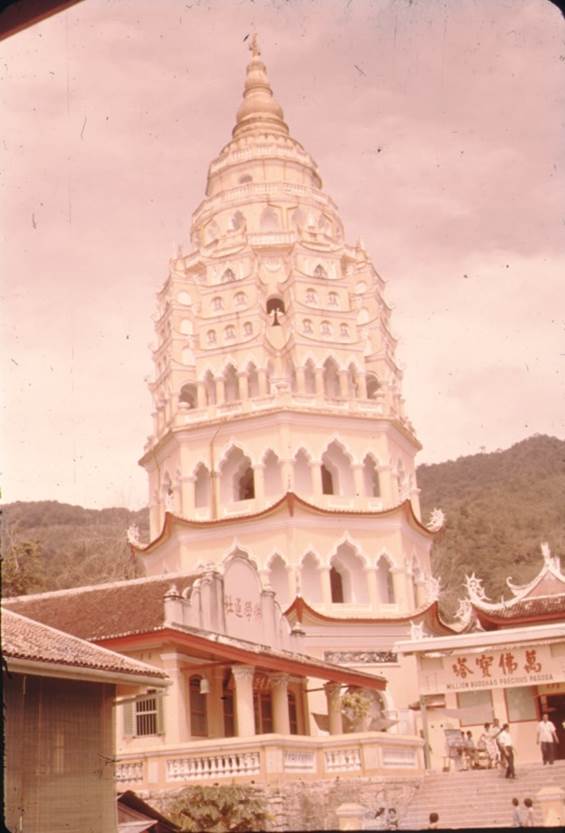

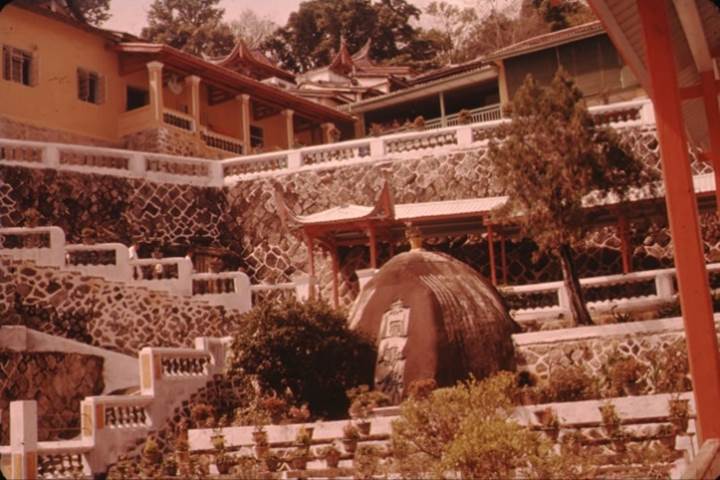

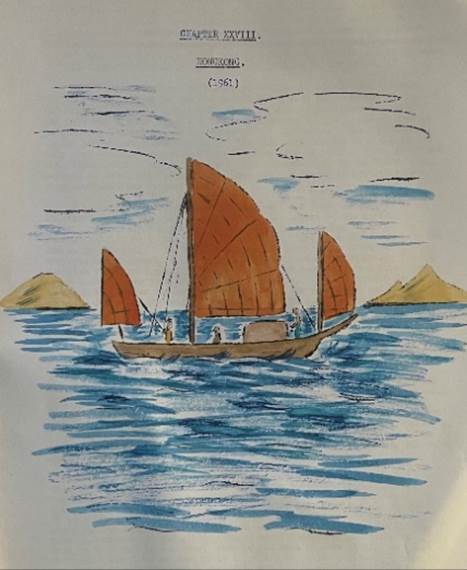

Chapter Illustrations were drawn by Anne Farndale. All the photographs were taken by Anne and Martin, during their travels at the time.

Preface

I was exceptionally lucky with my opportunities for travel, initially with my parents, then with my job in the Foreign Office, and later as an army wife. This is not intended to be a travel book in the ordinary sense, but simply a collection of word pictures of places far and near between 1946 (when I was 18) and 1962 (when I was 34). It is a snapshot album to thumb through on a warm summer’s day. It is an attempt to capture and distil the essential essence and mood of a diversity of countries visited.

Contents

I – Switzerland (1946)

II – Paris (1947)

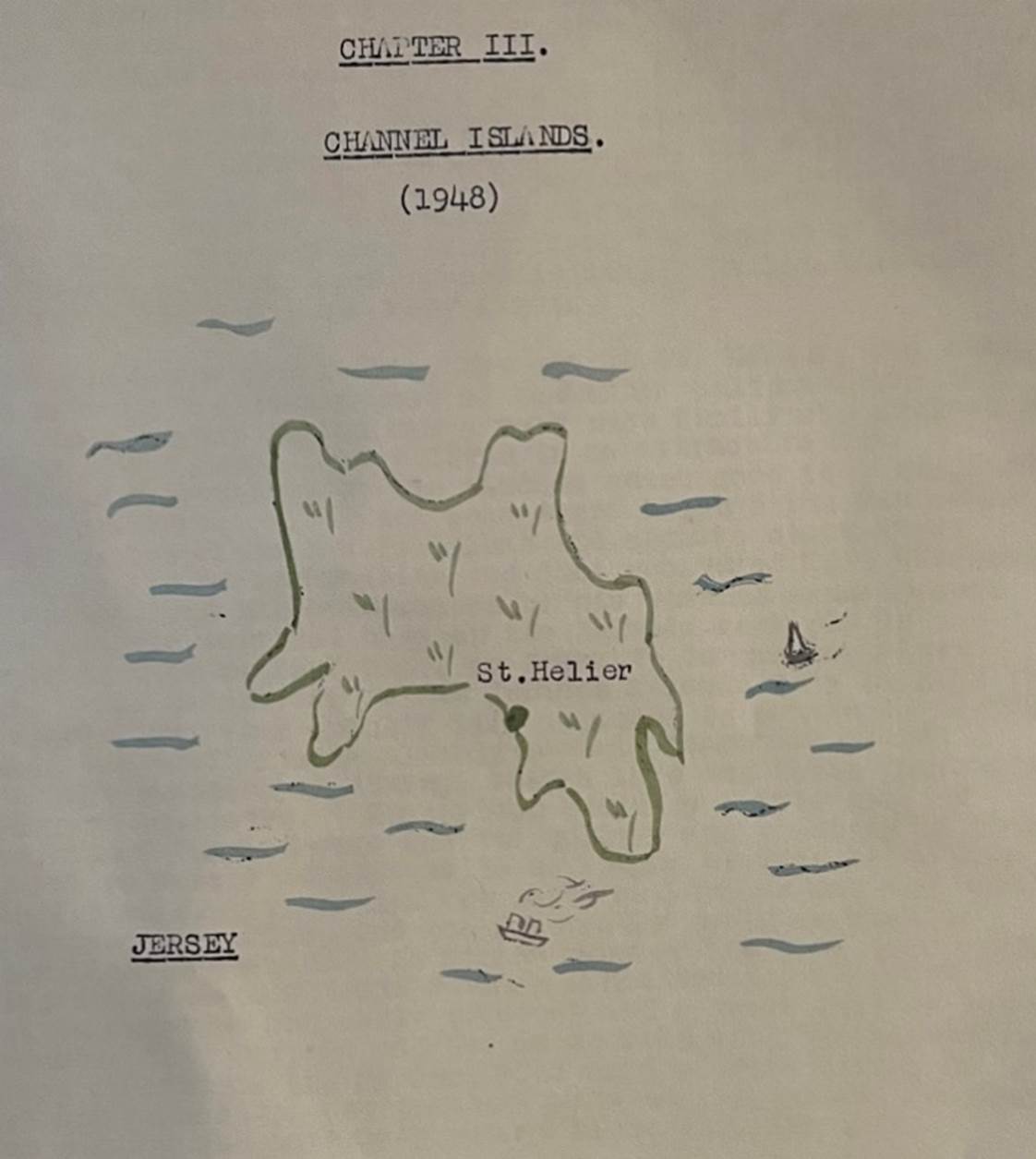

III – The Channel Islands (1948)

IV – Egypt (1949)

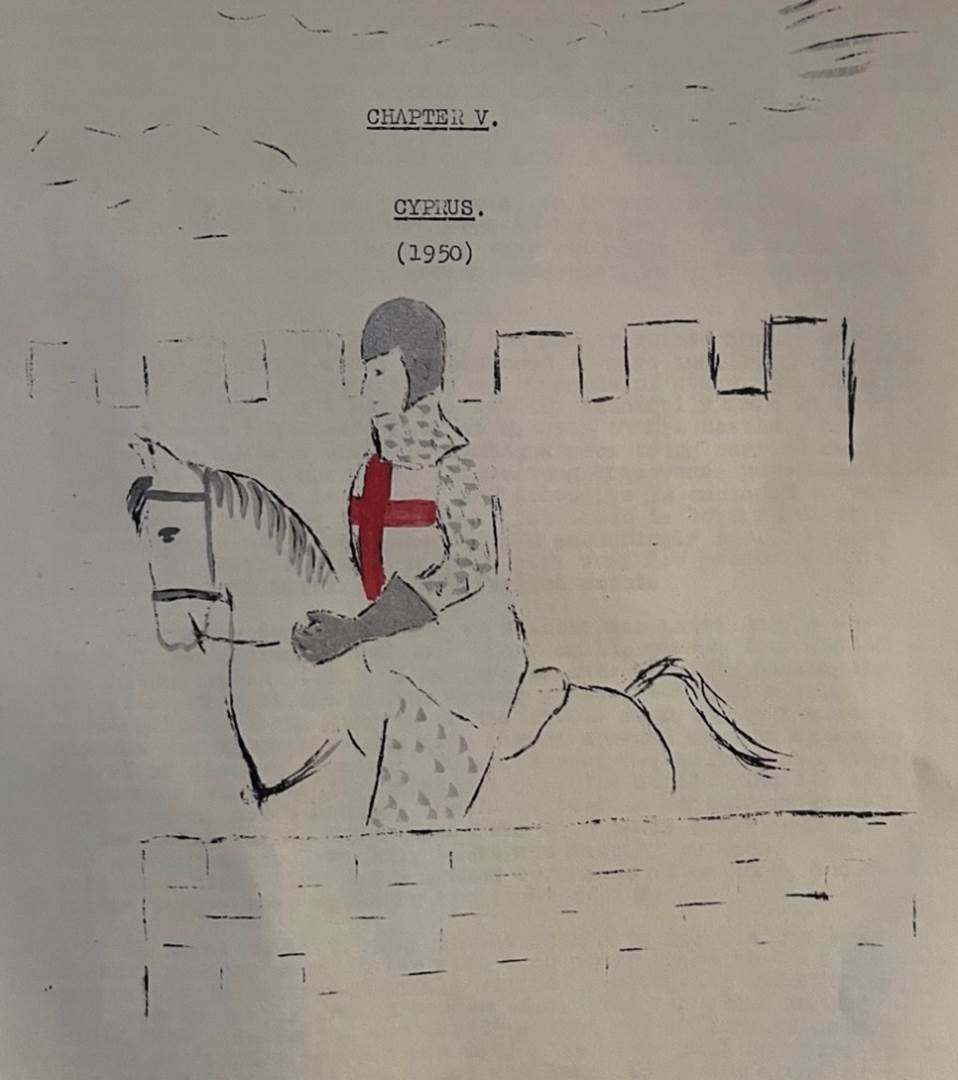

V – Cyprus (1950)

VI – Germany

(1951)

VII - More about Germany

VIII – Denmark and Sweden (1951)

IX – Austria and Bavaria (1952)

X – Holland (1952)

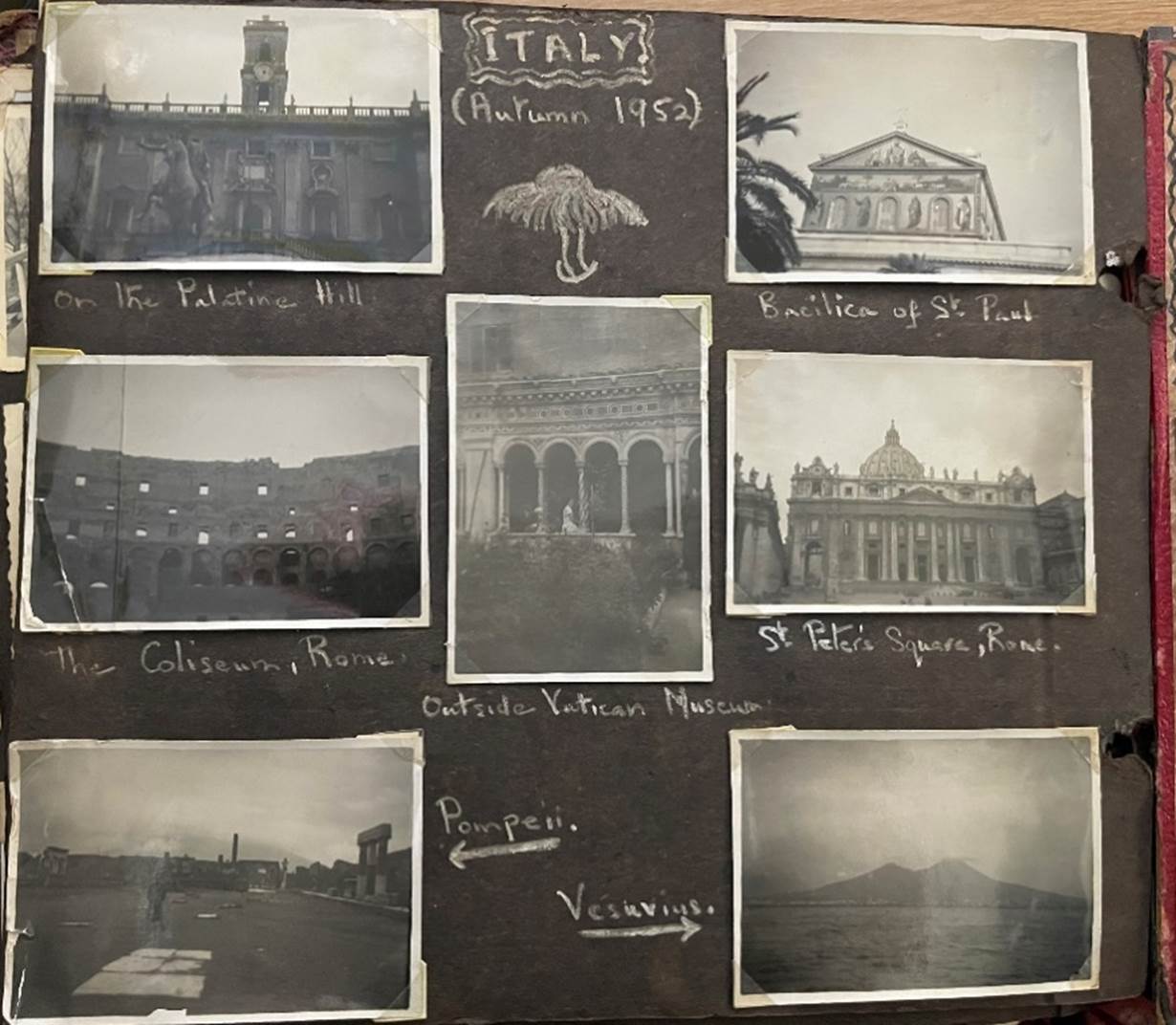

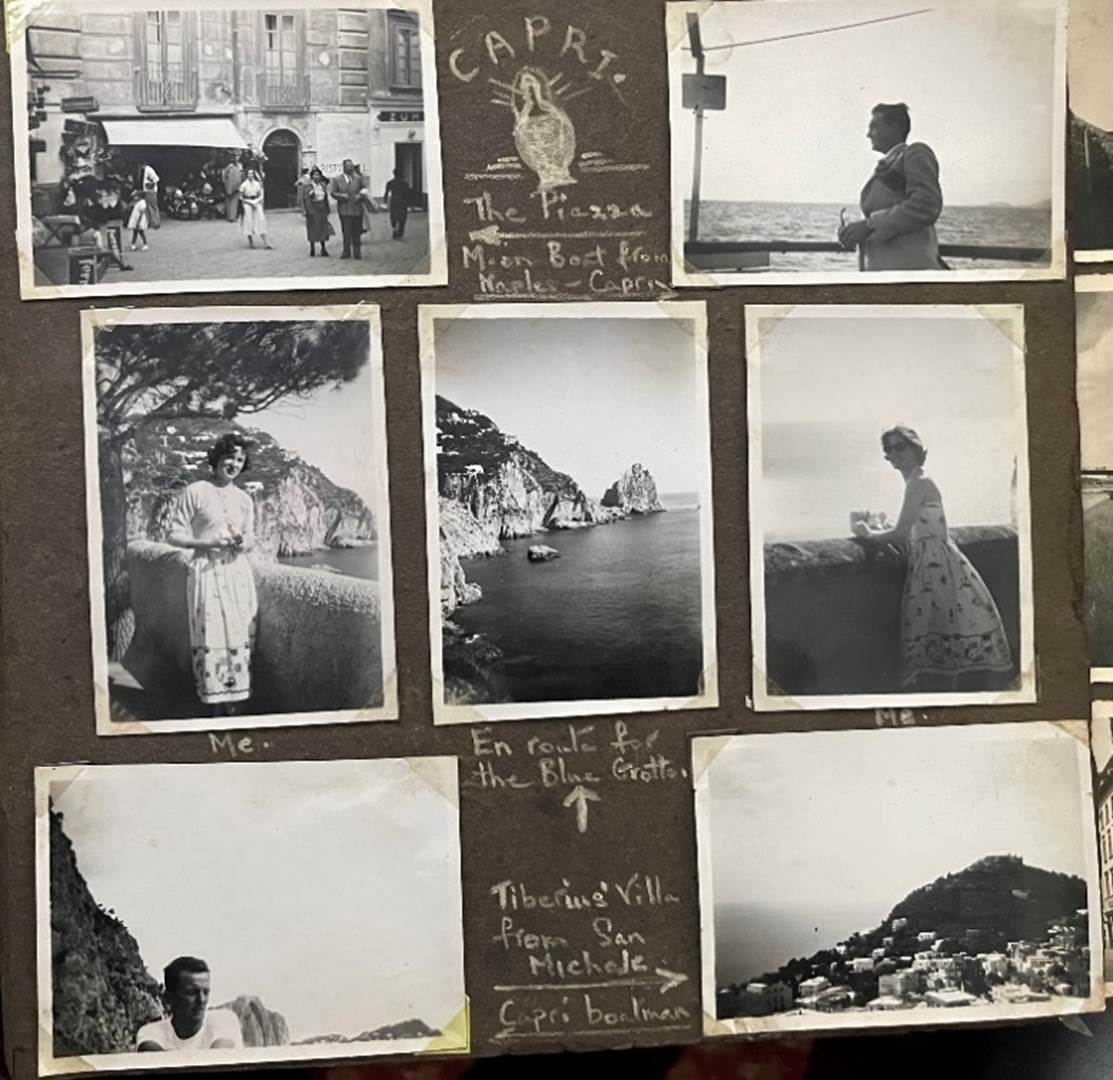

XI – Italy (1952)

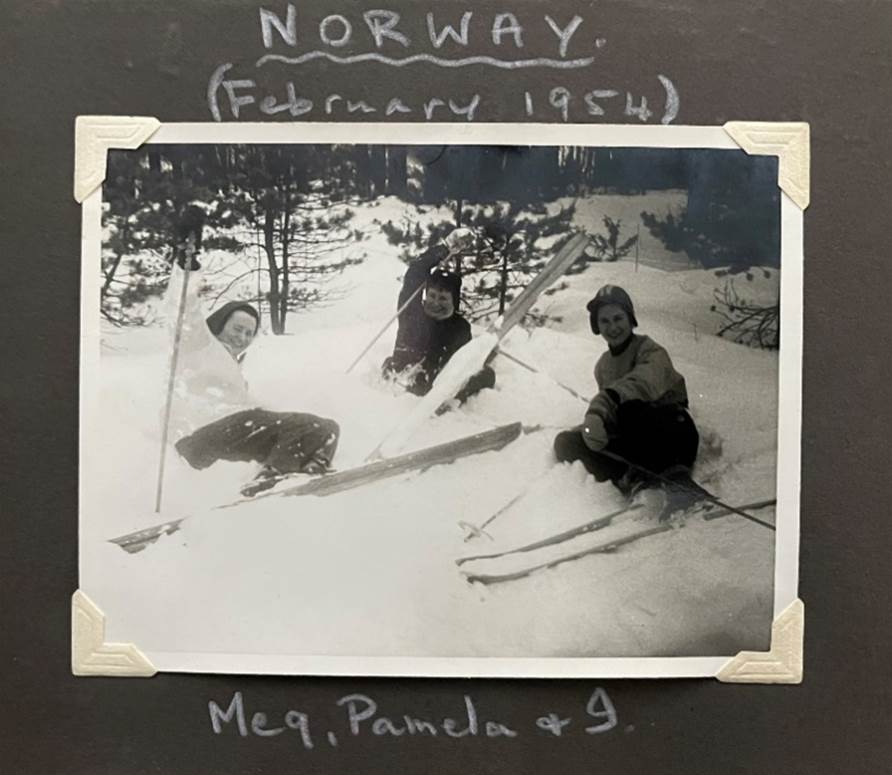

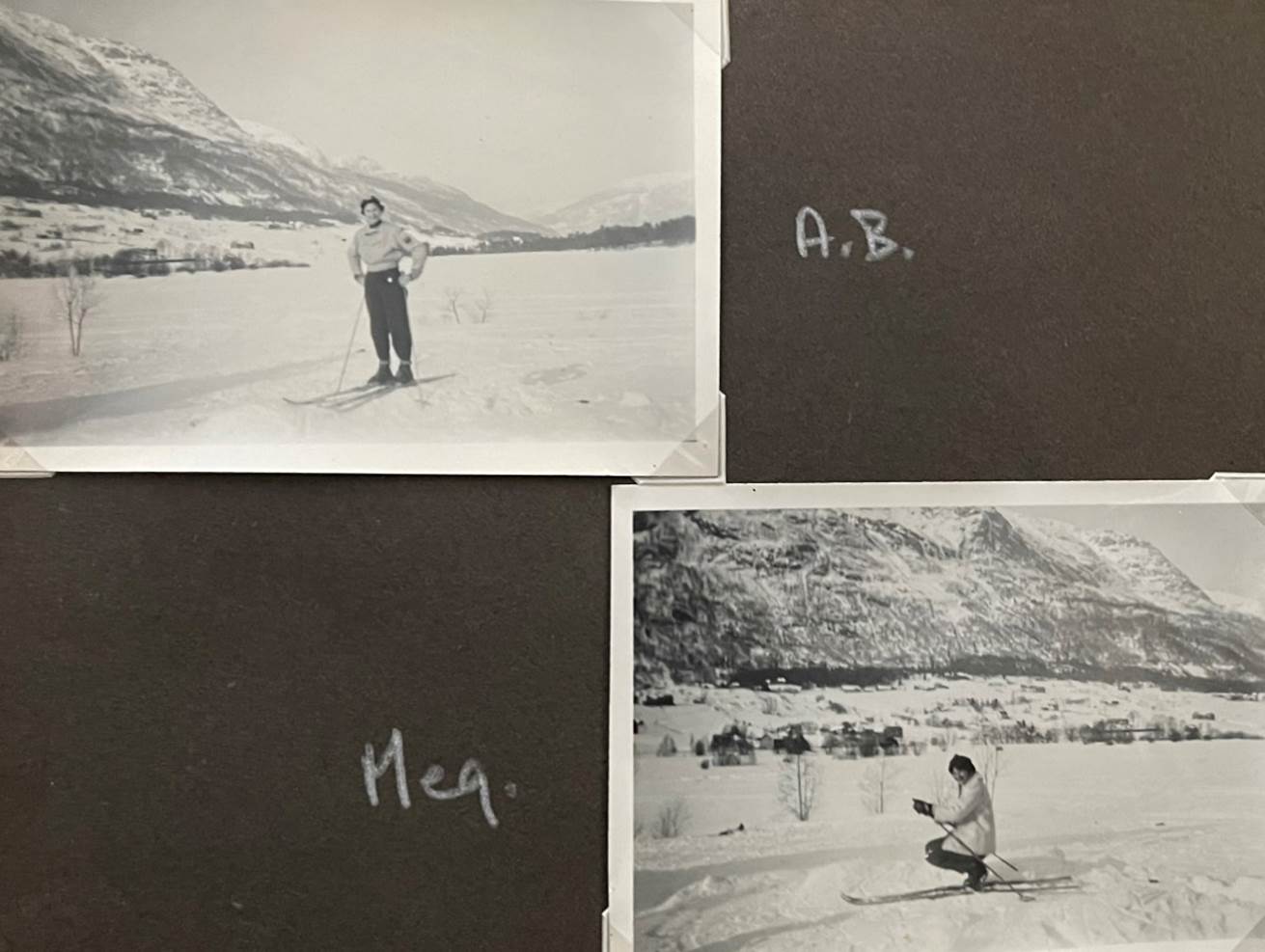

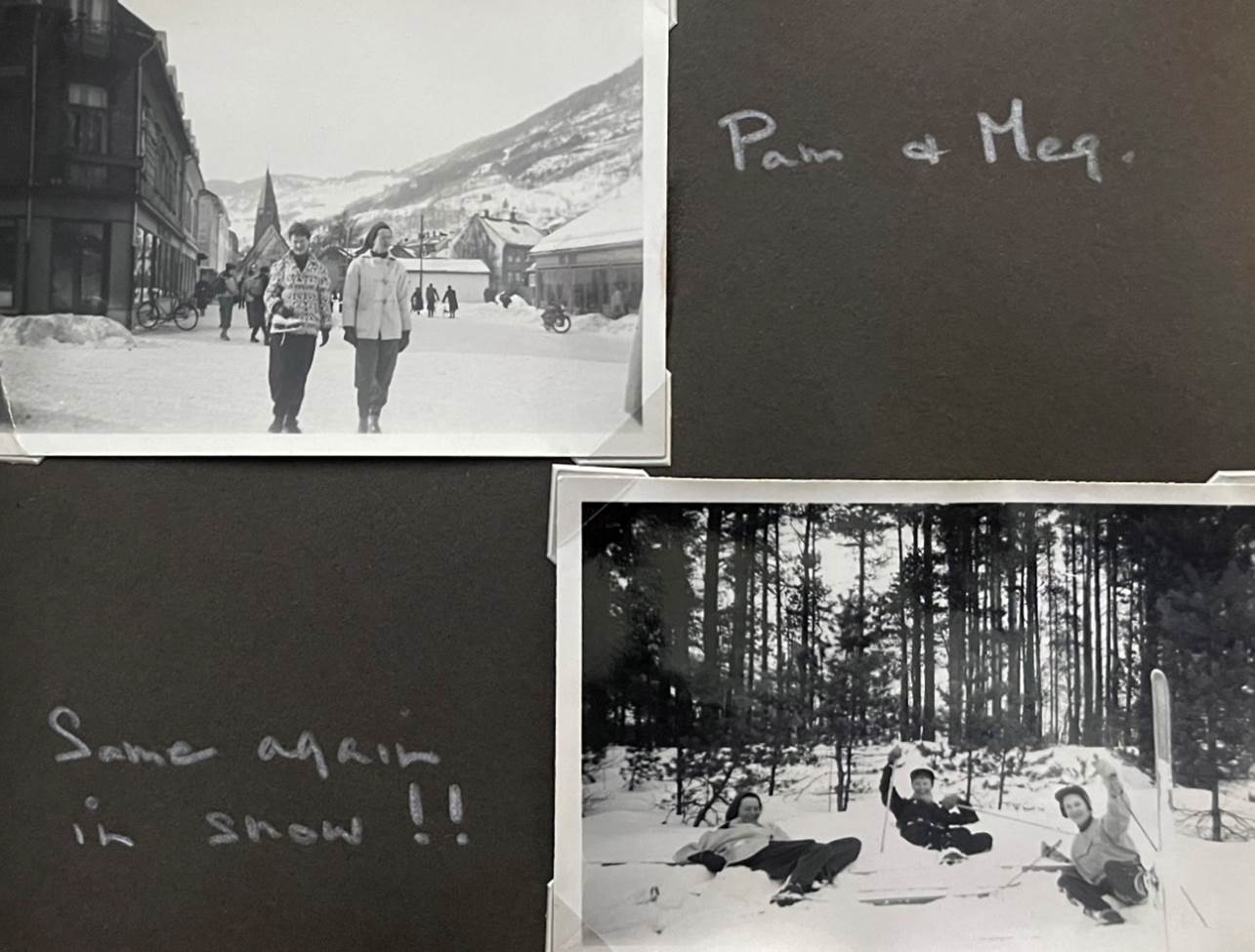

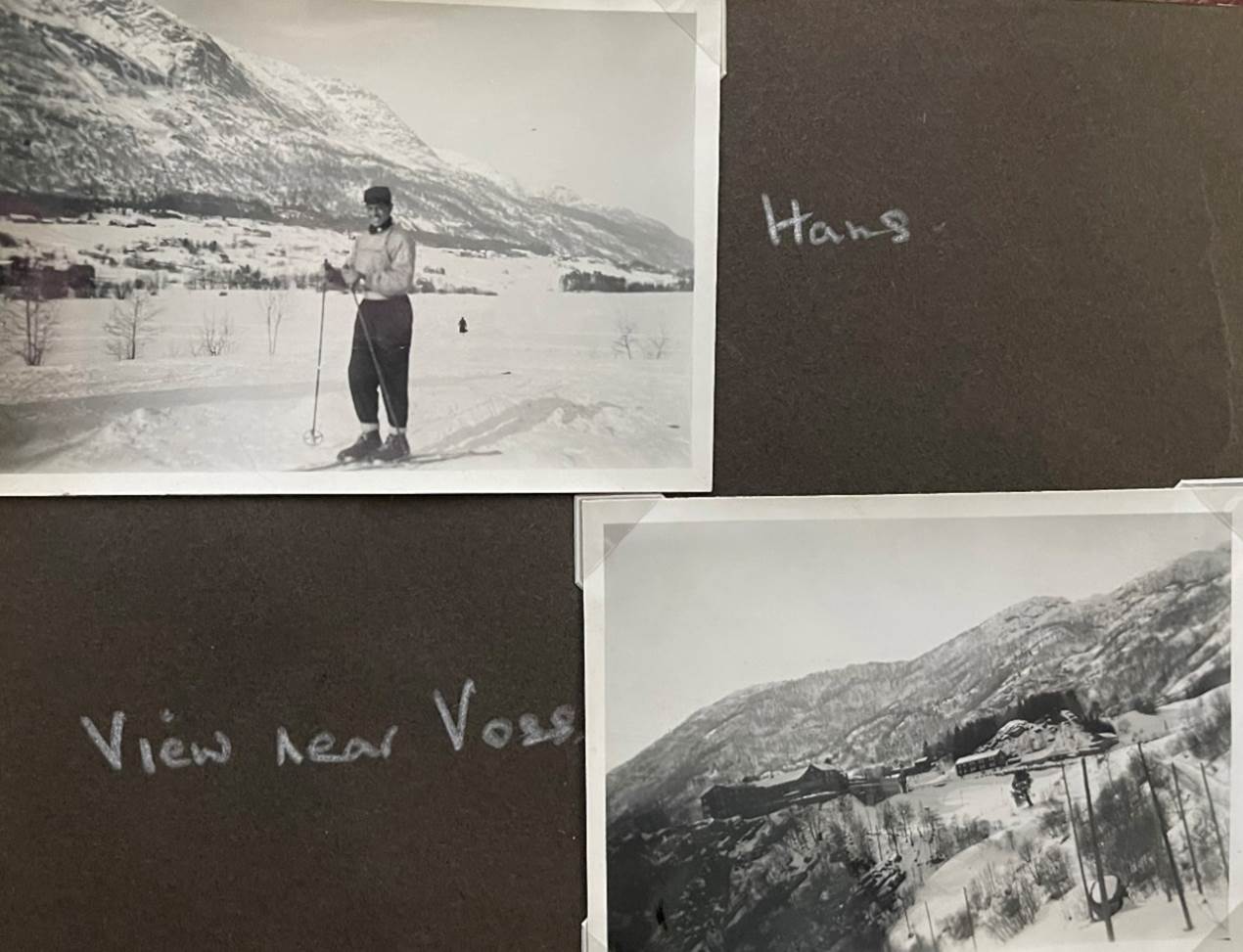

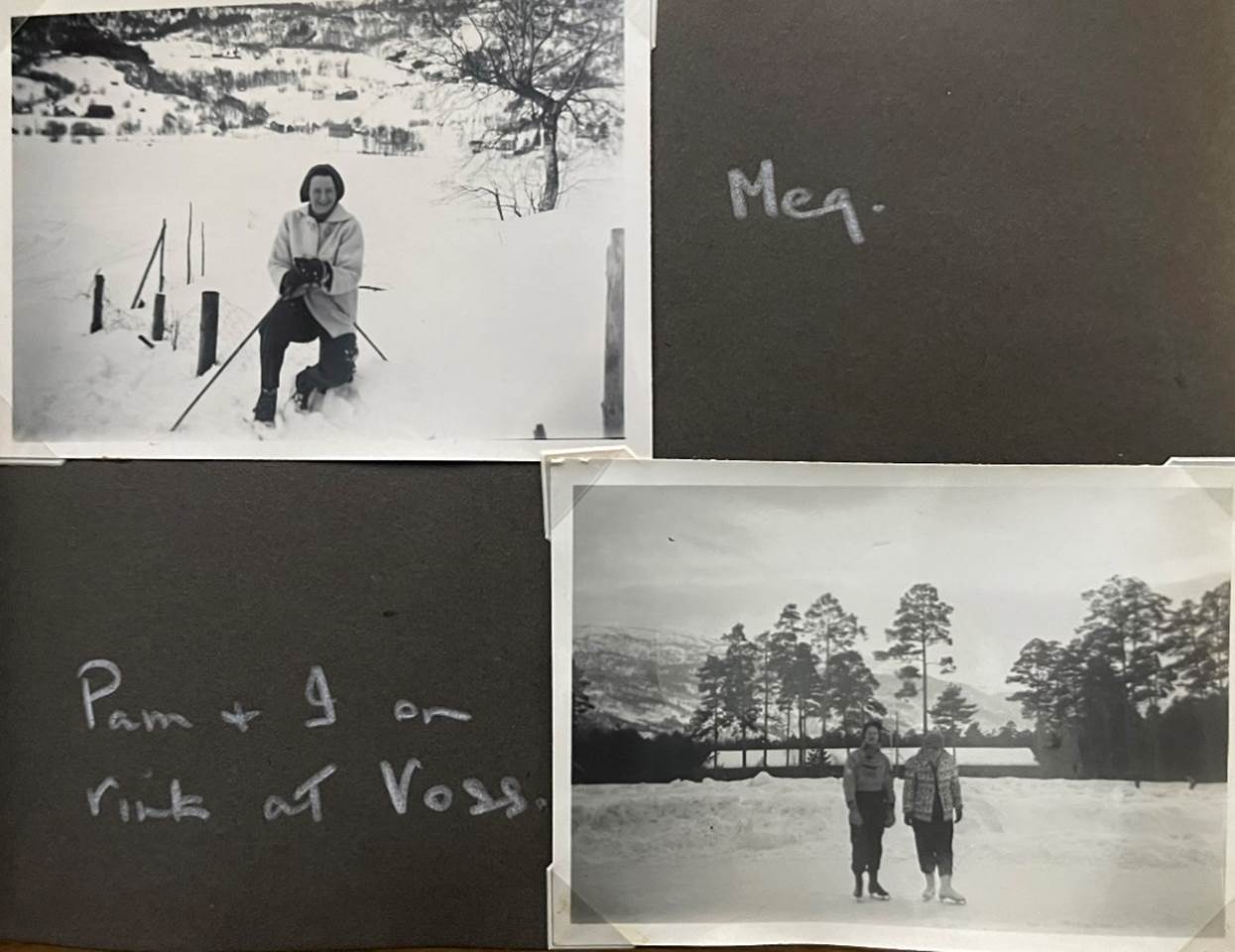

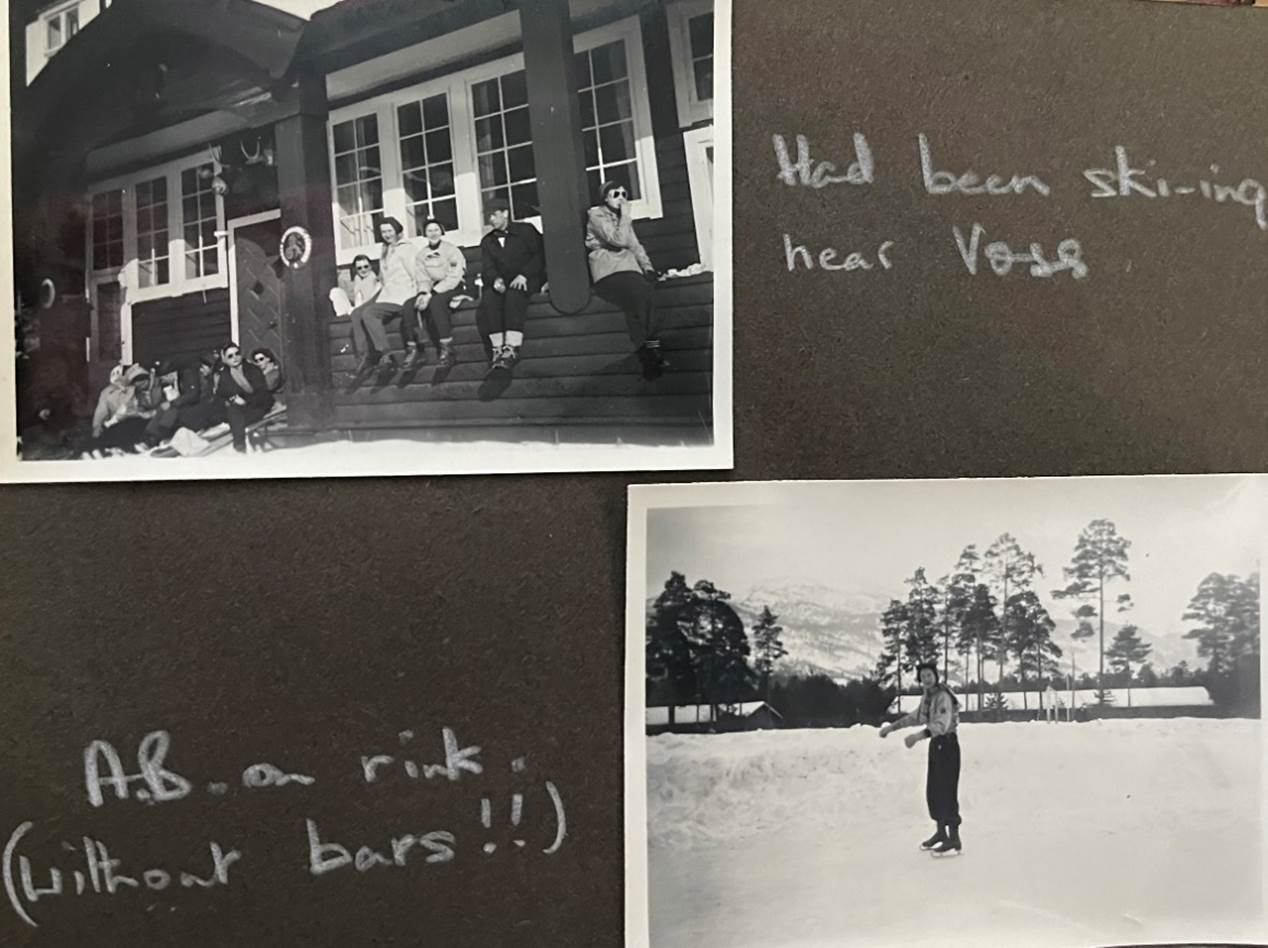

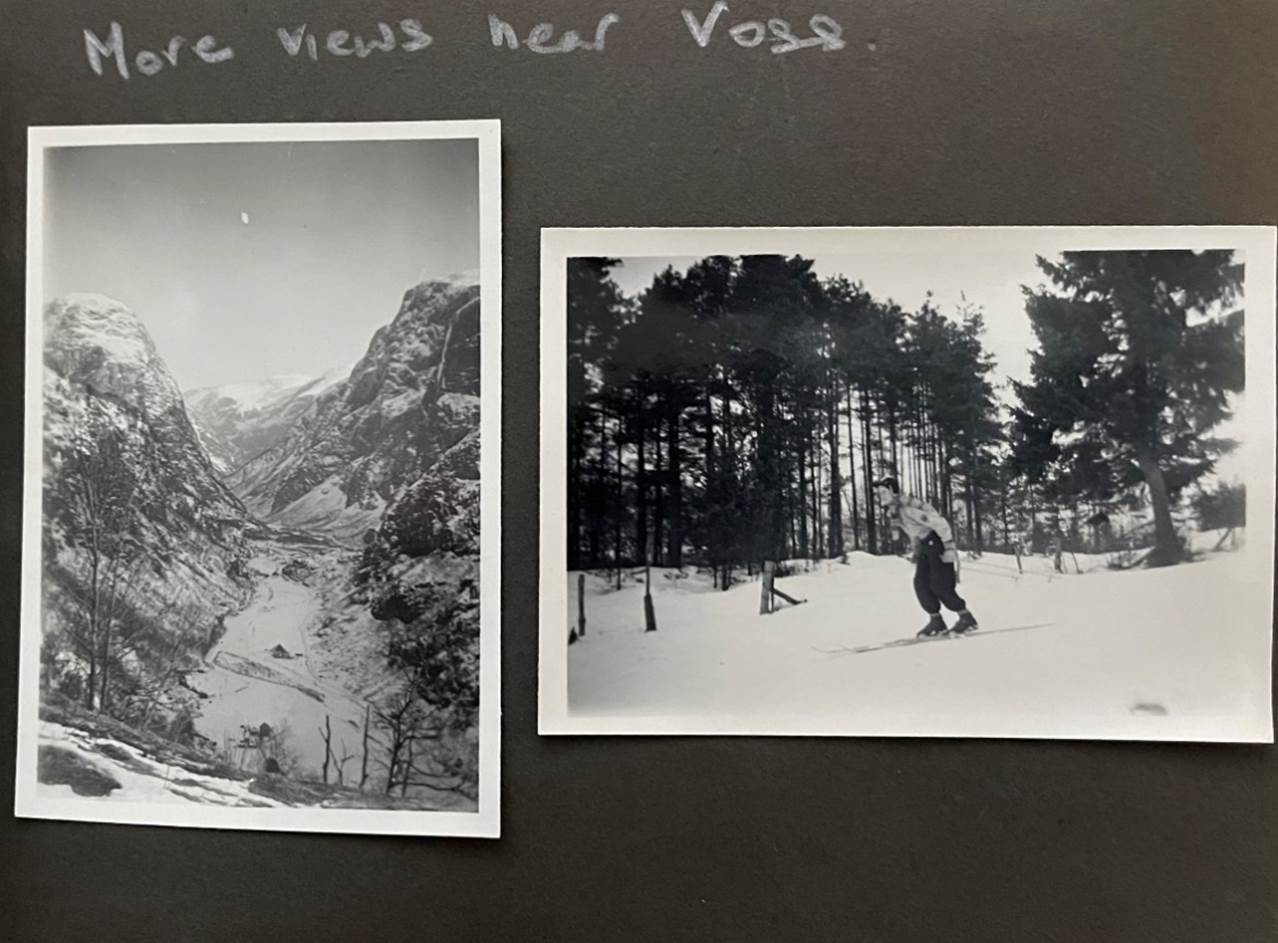

XII – Norway (February 1954)

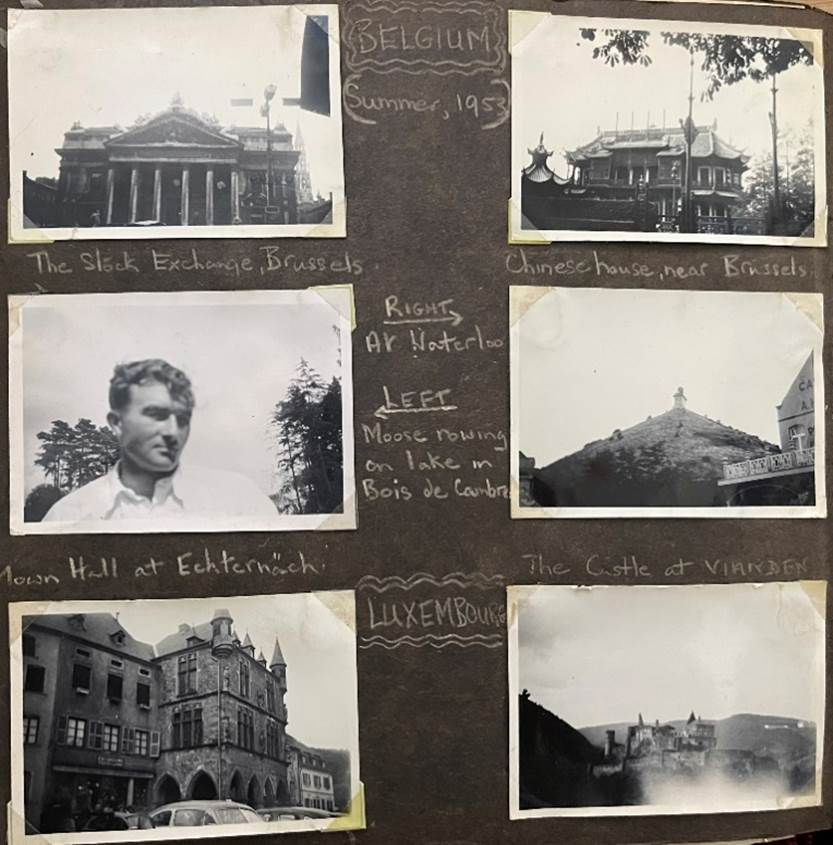

XIII – Belgium (1953)

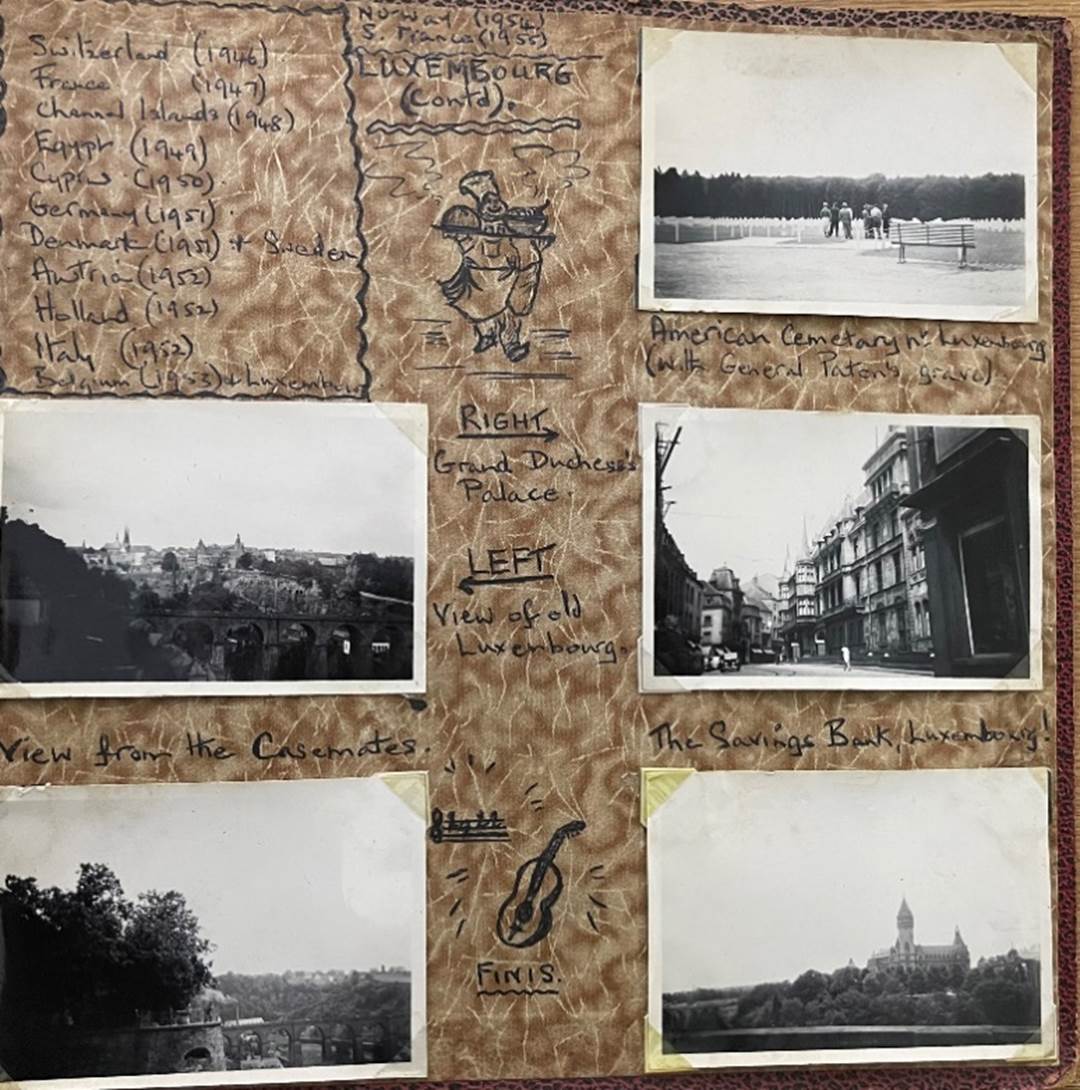

XIV – Luxembourg (1953)

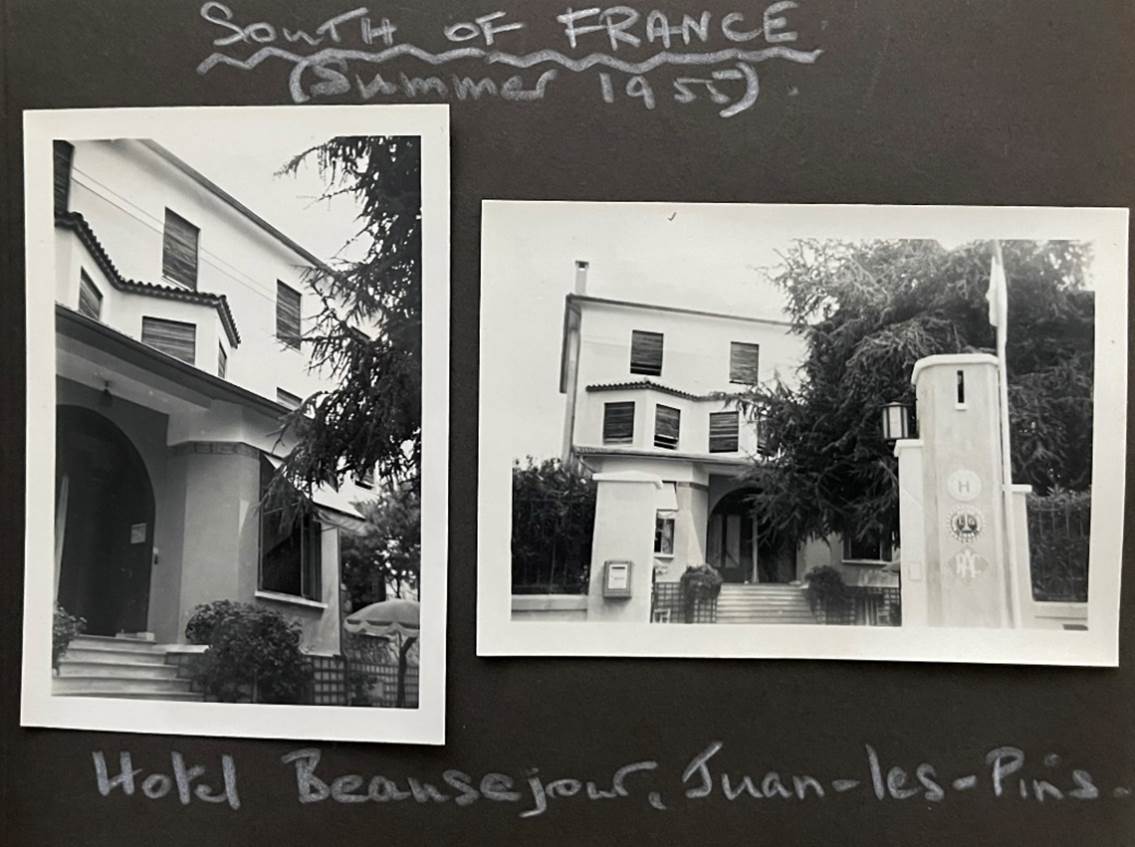

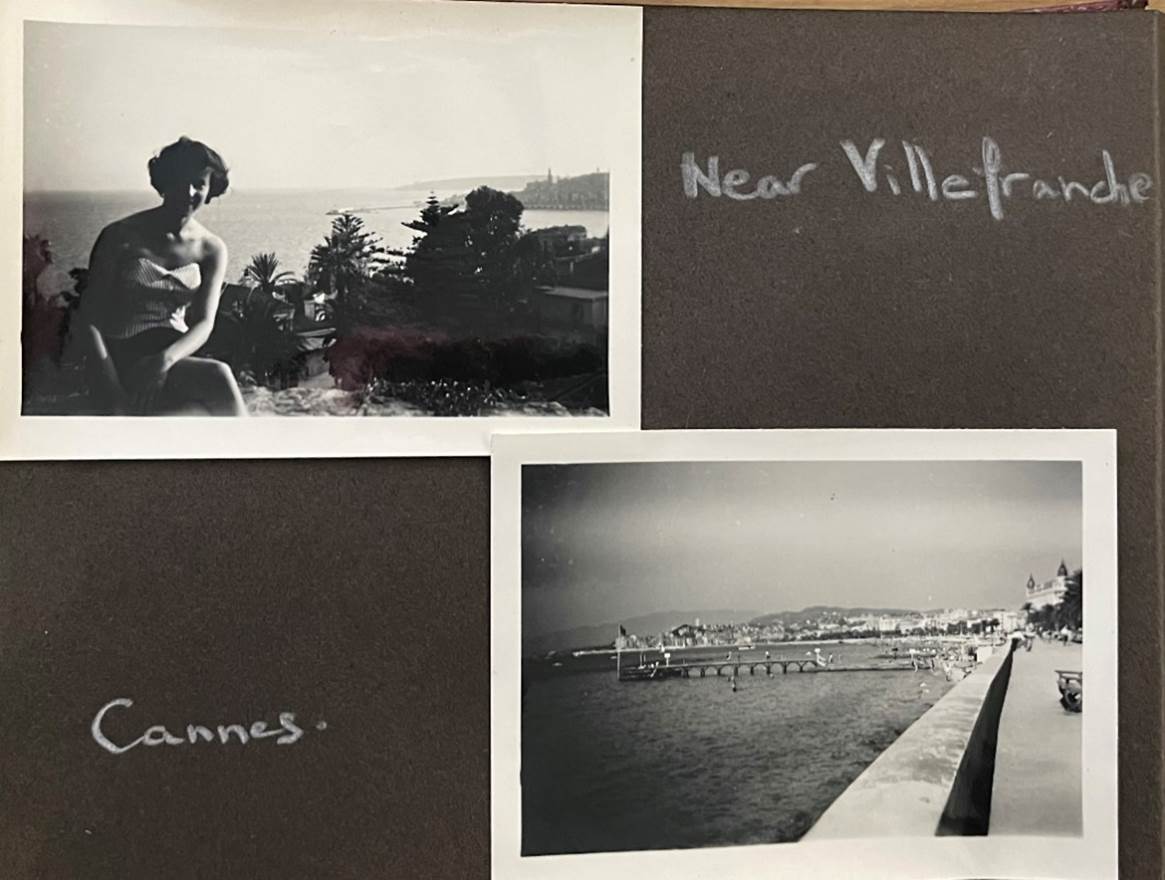

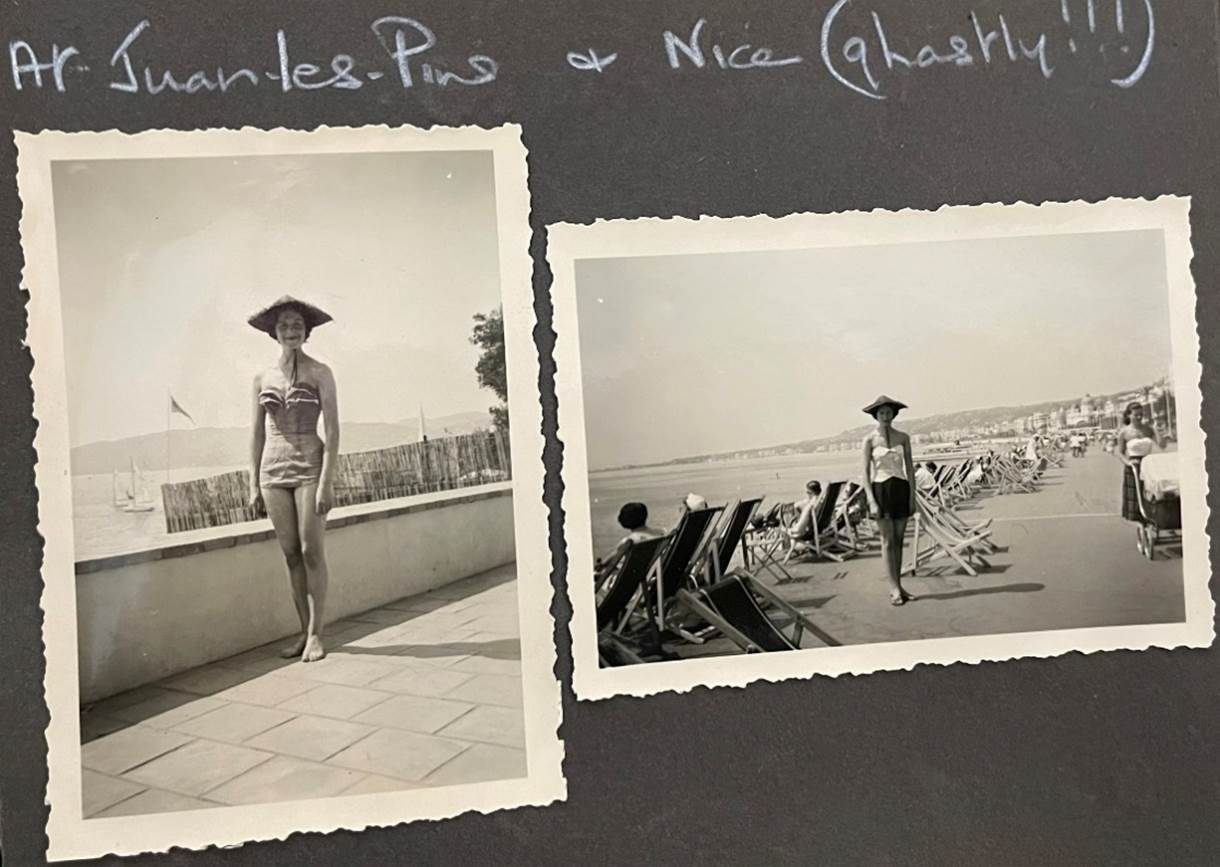

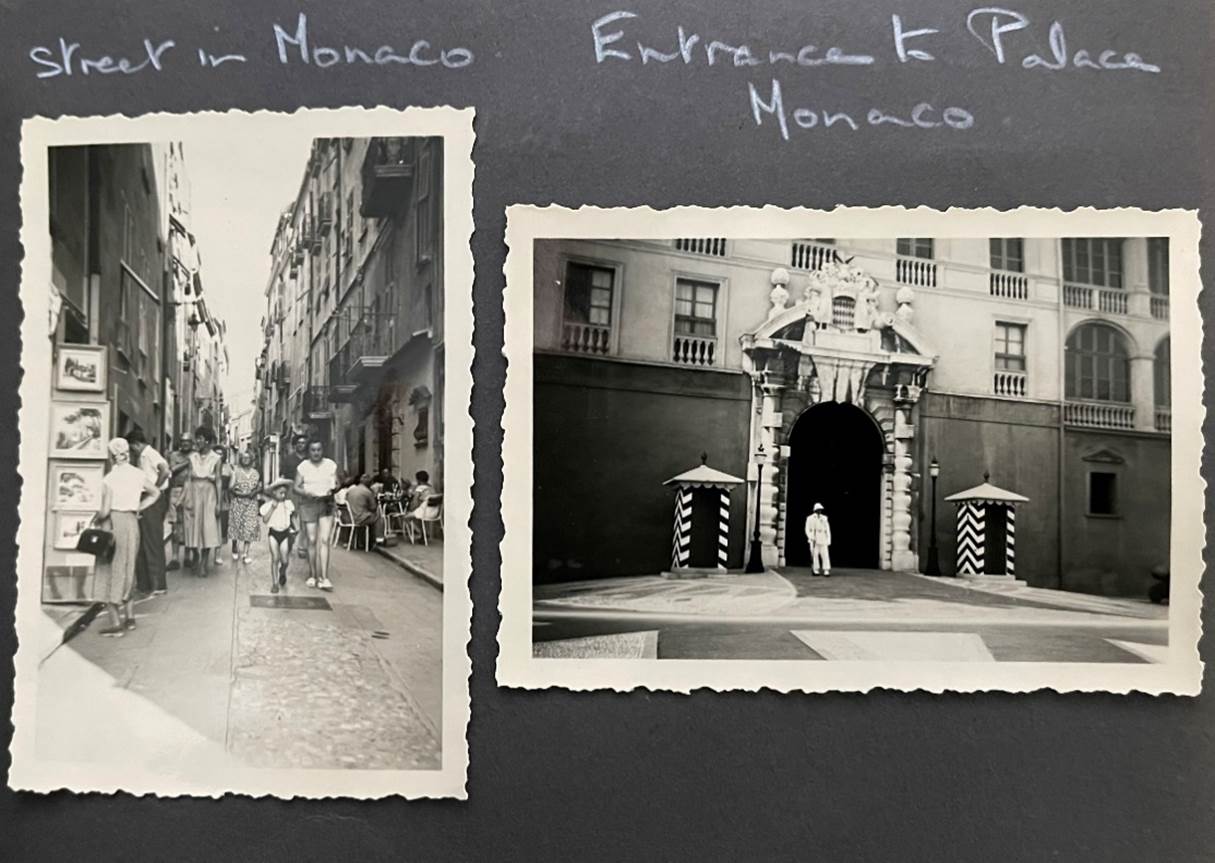

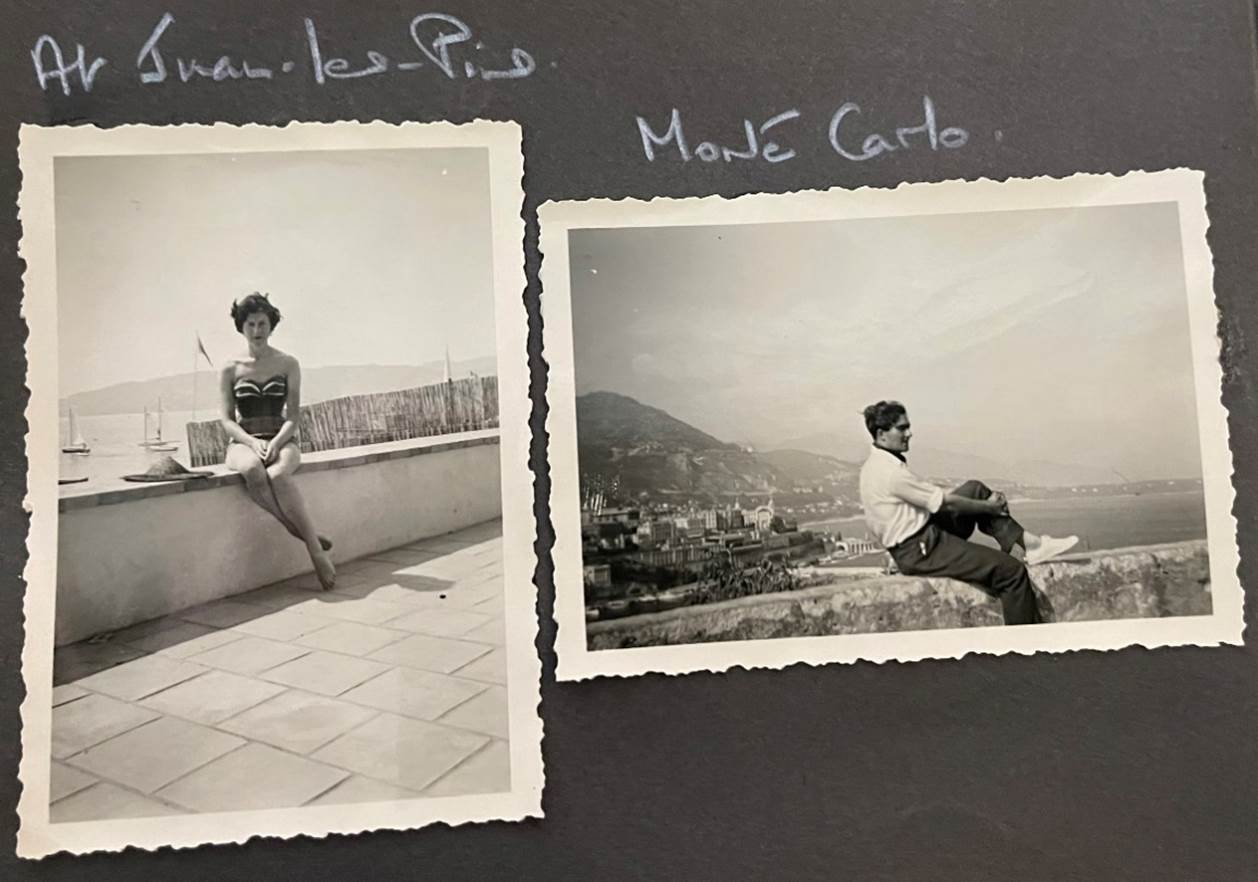

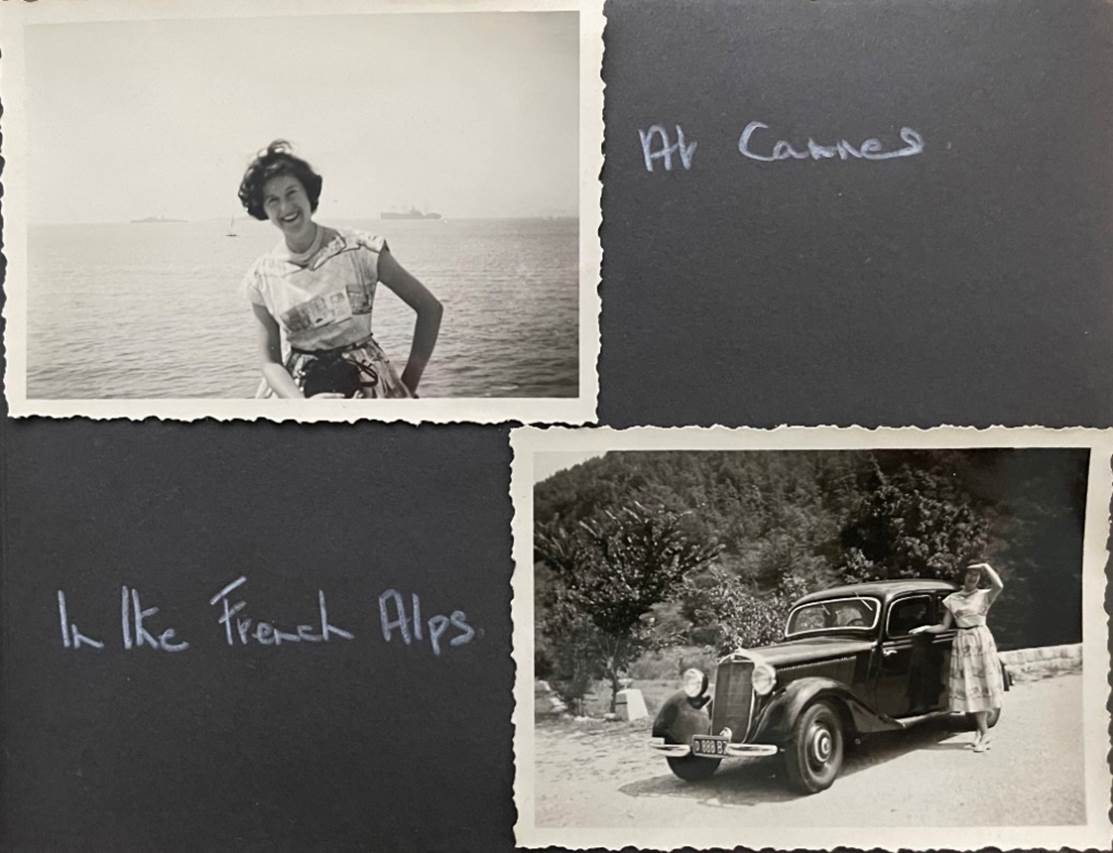

XV – The South of France (Summer 1955)

XVI – Battlefield Tour (1956)

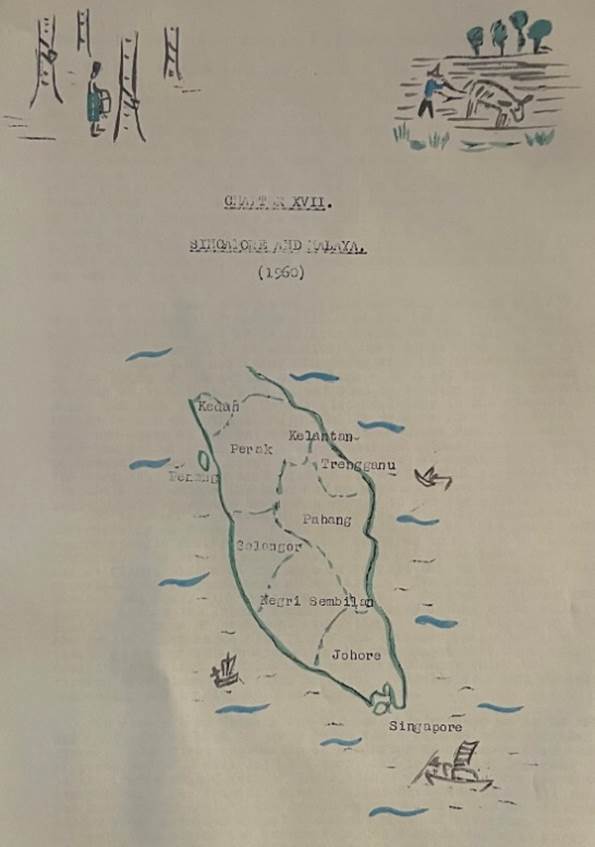

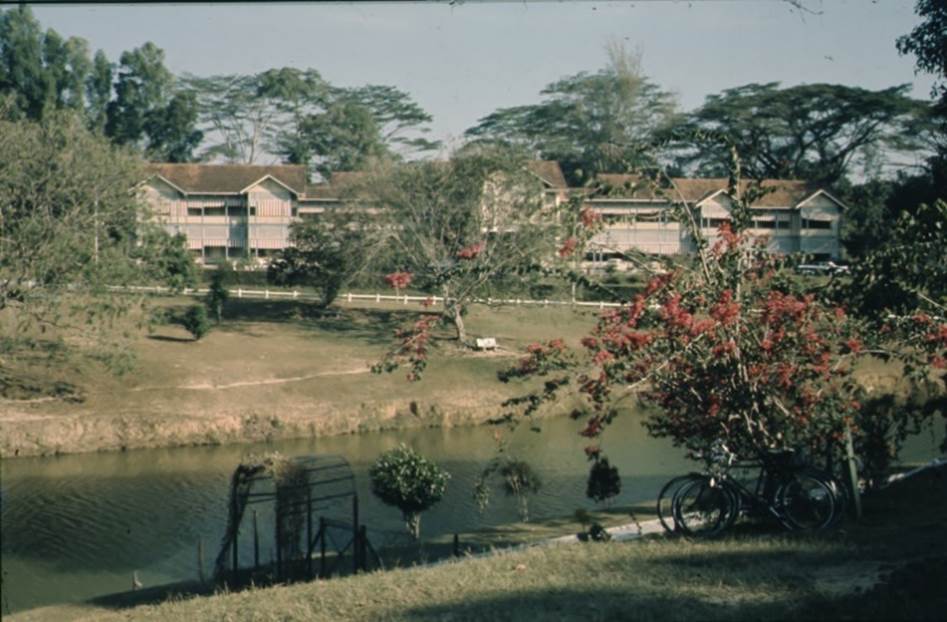

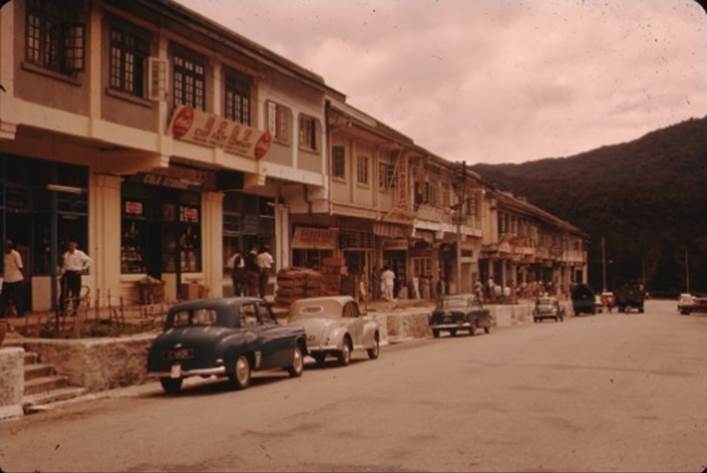

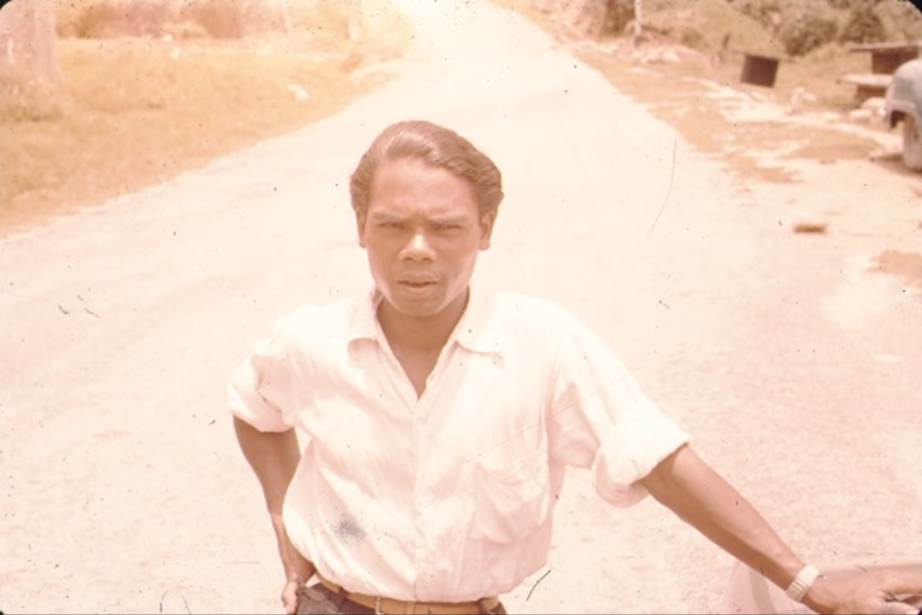

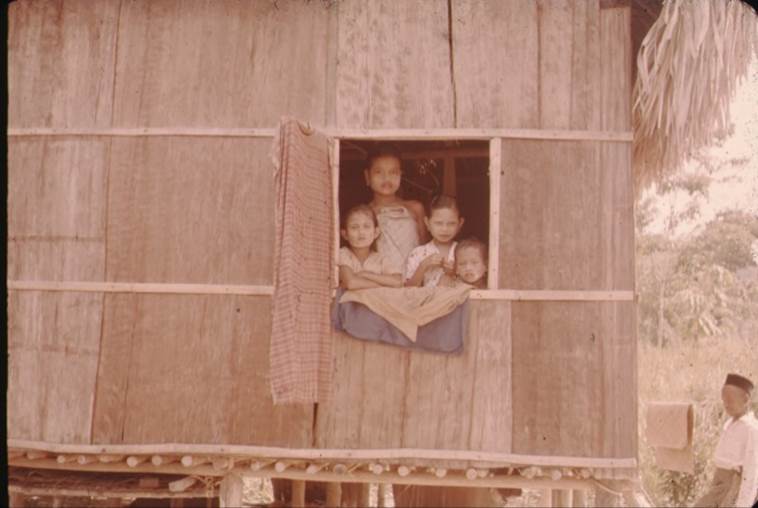

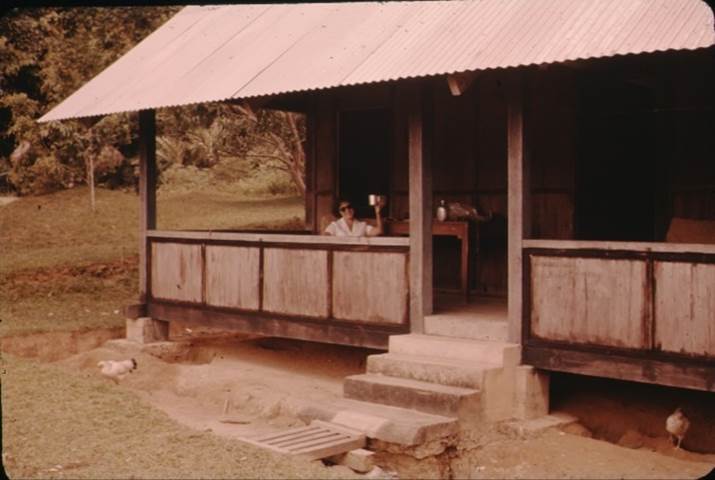

XVII – Singapore and Malaya (1960)

XVIII – More about Singapore and Malaya (1960 to 1961)

XIX – Muslim beliefs

XX – A Chinese aspect

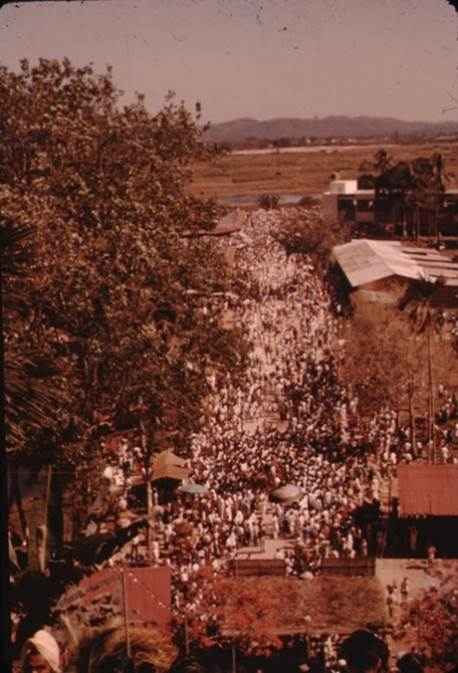

XXI – Some Hindu beliefs and festivals

XXII – The East Coast of Malaya (1960)

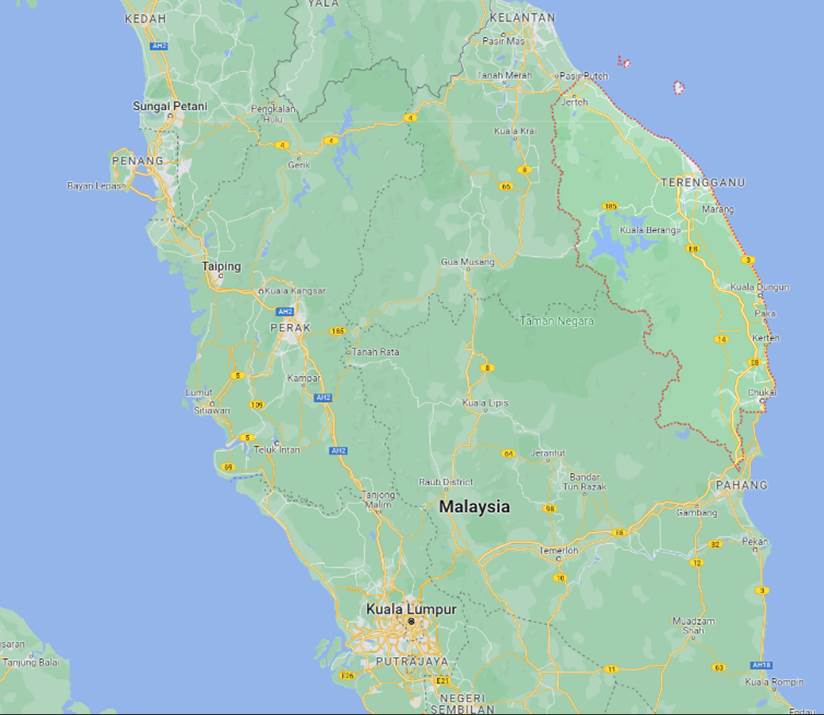

XXIII – An unusual weekend (August 1960)

XXIV – Bangkok (1960)

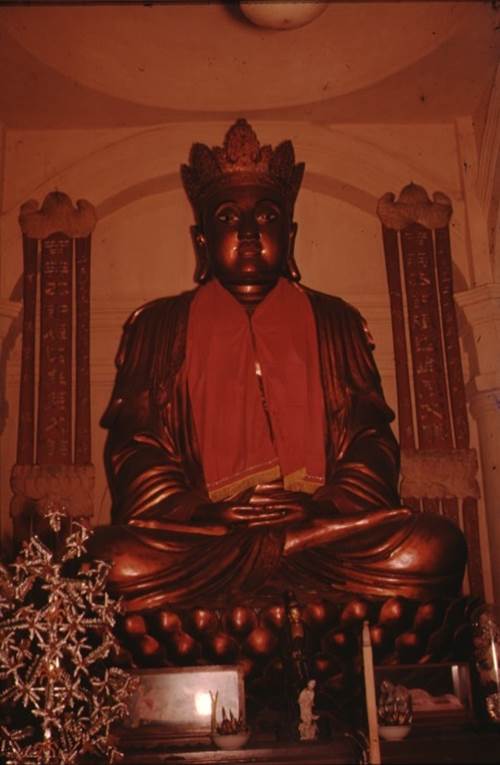

XXV – Buddhism

XXVI – Penang and the Cameron Highlands (1961)

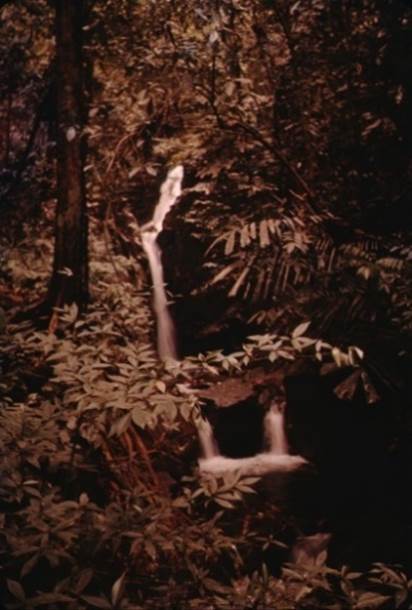

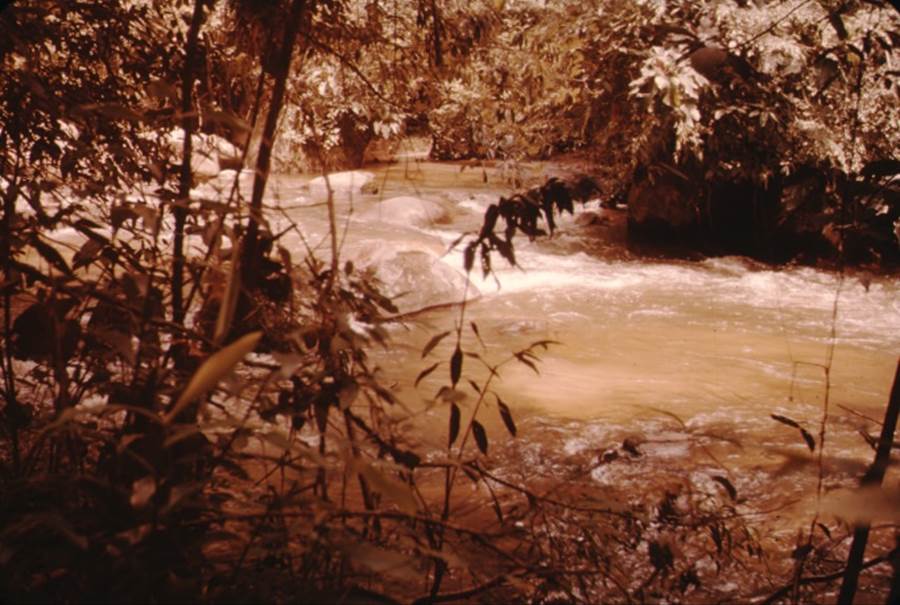

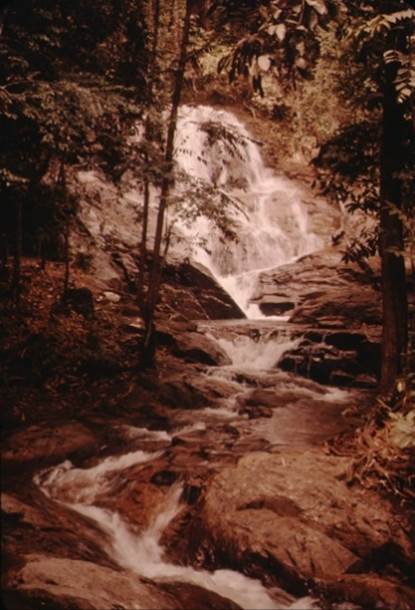

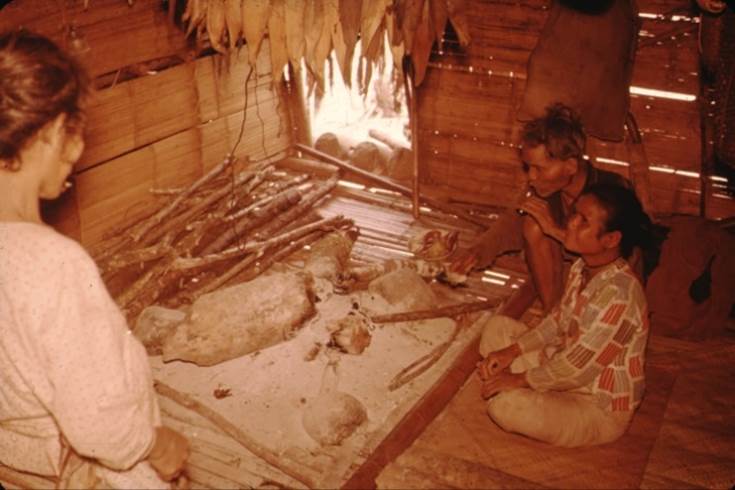

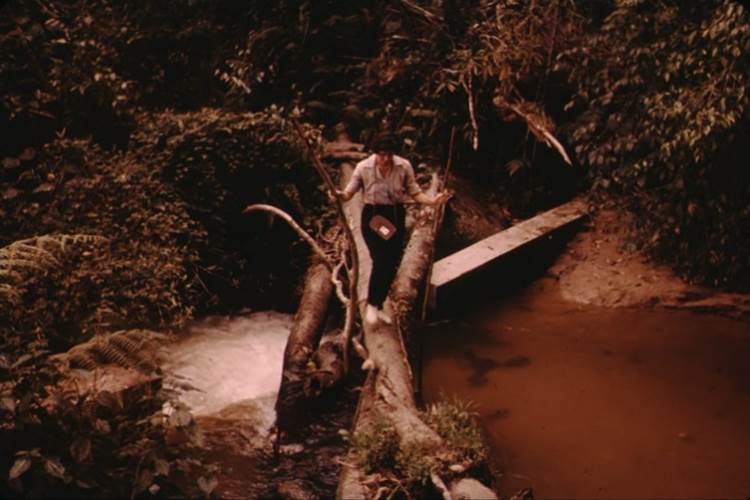

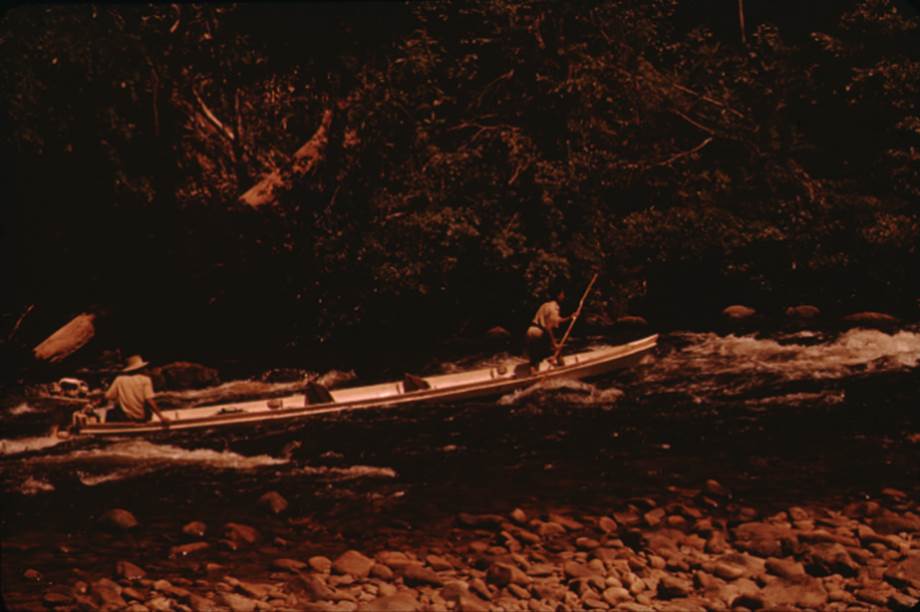

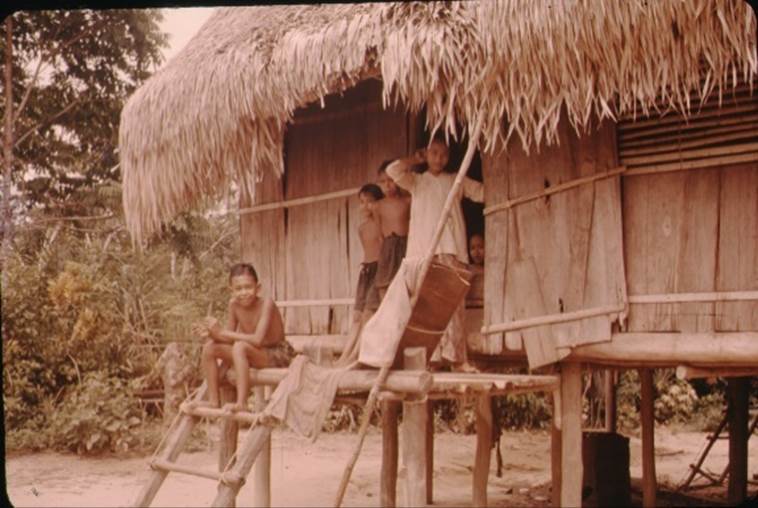

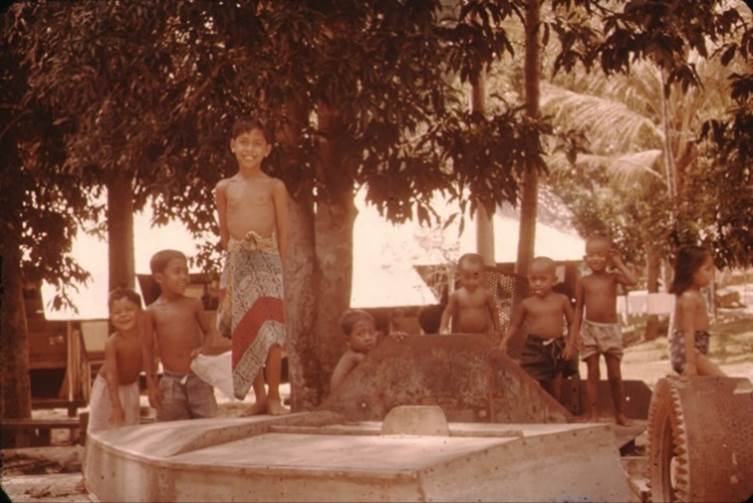

XXVII – The National Park, Malaya (1961)

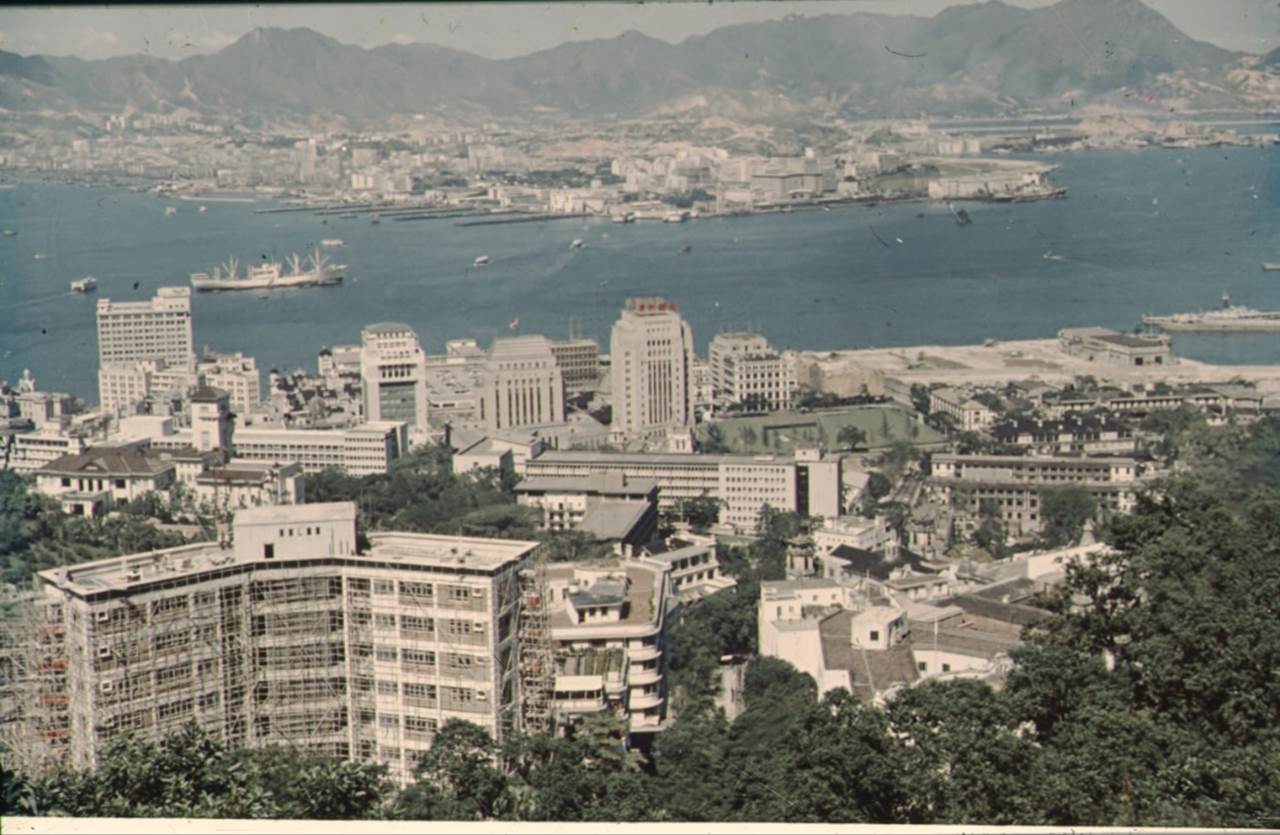

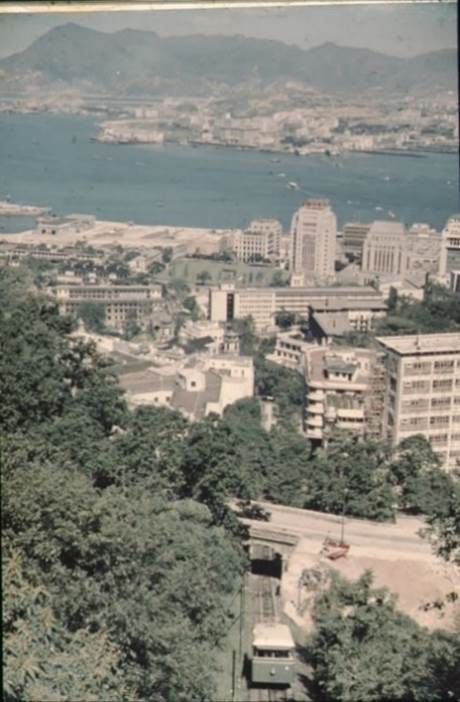

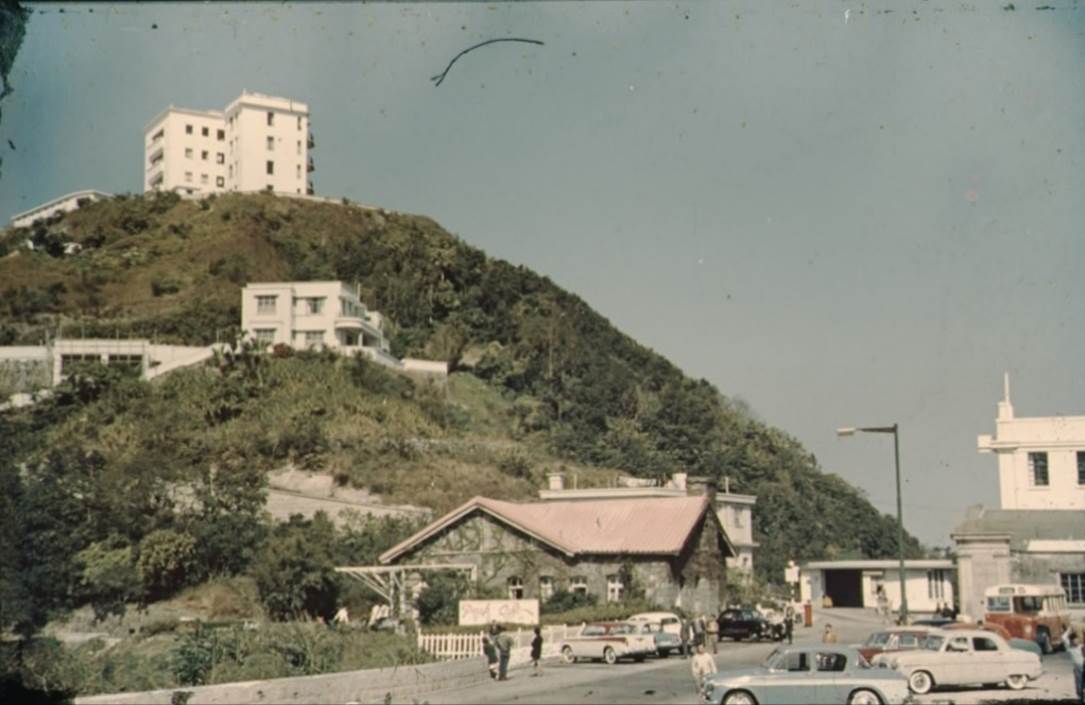

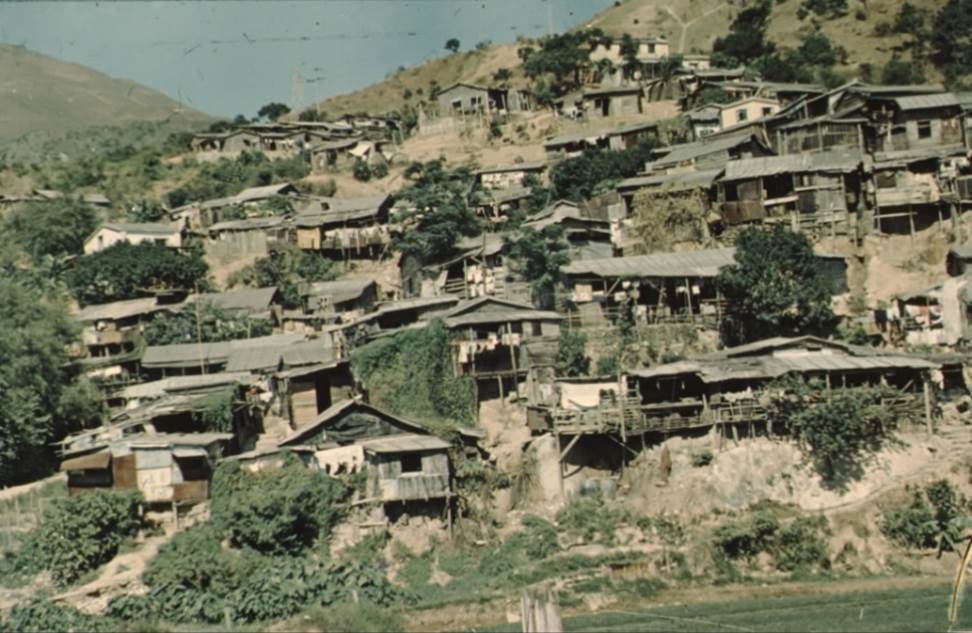

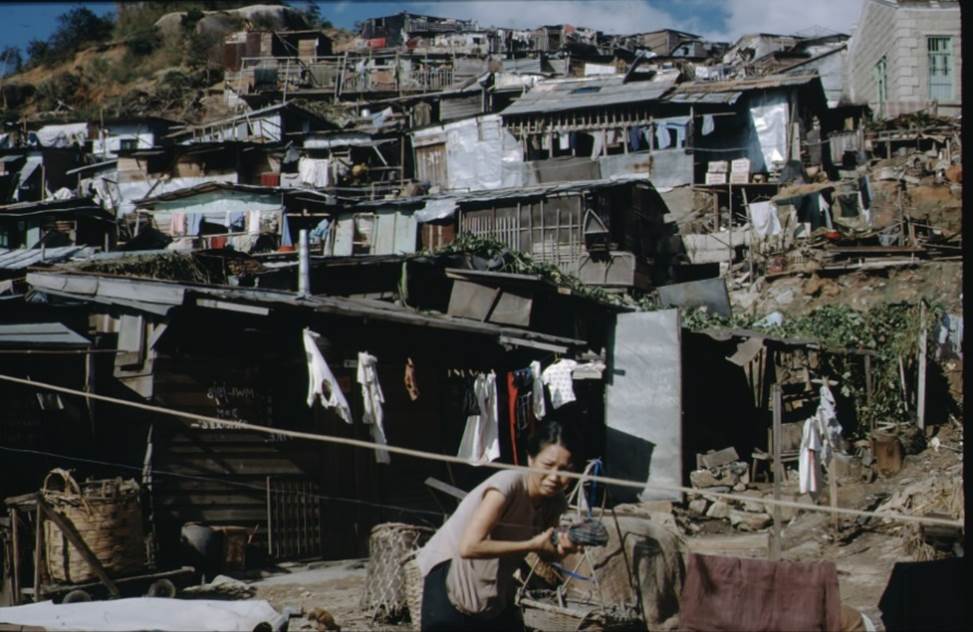

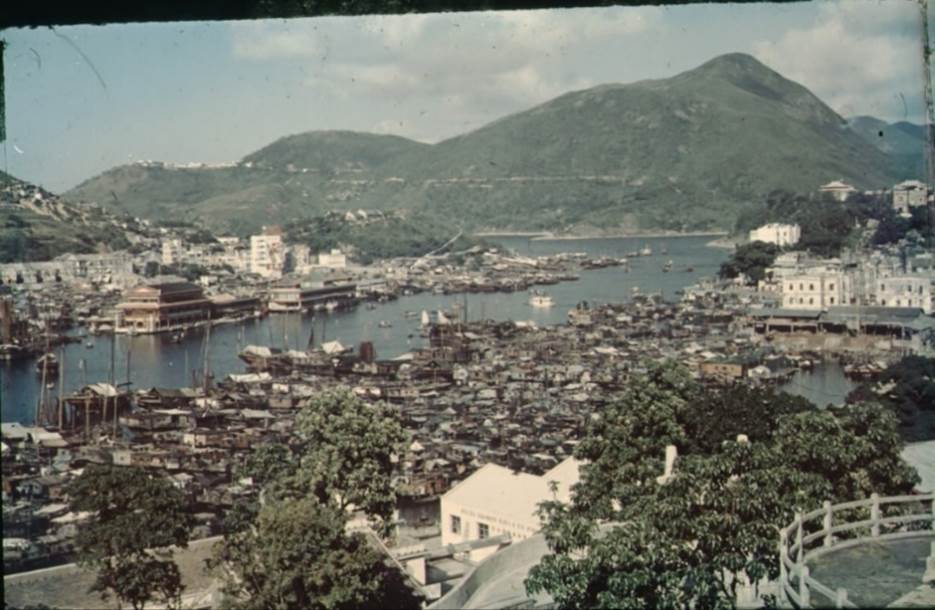

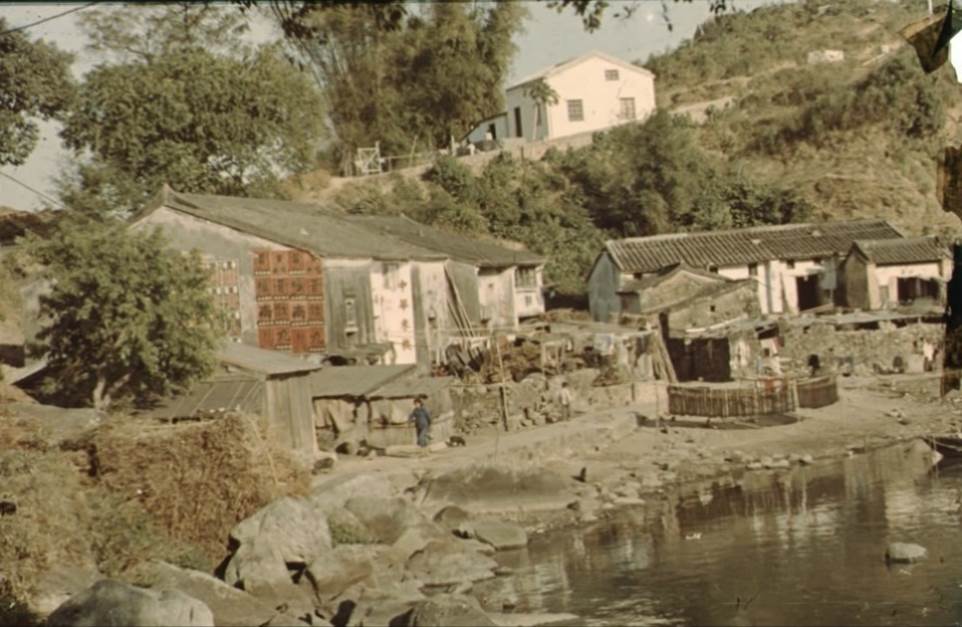

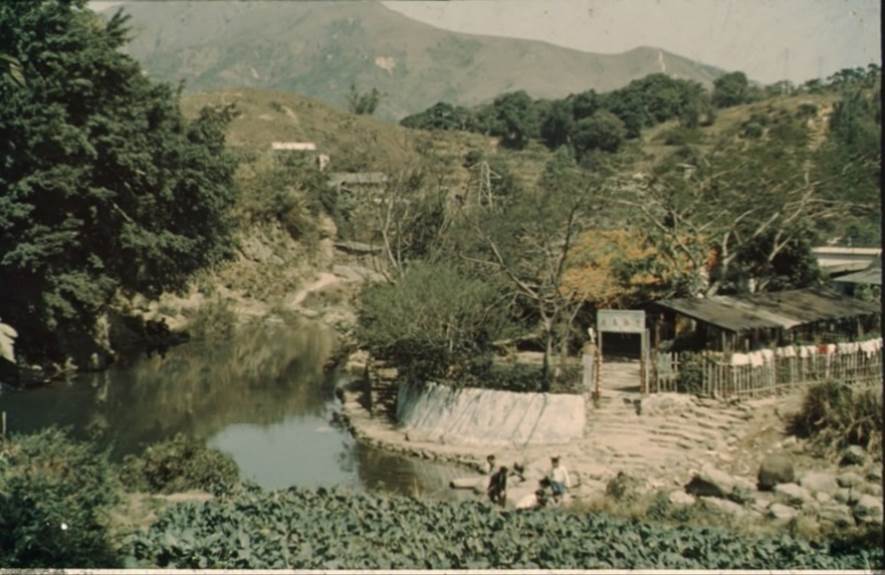

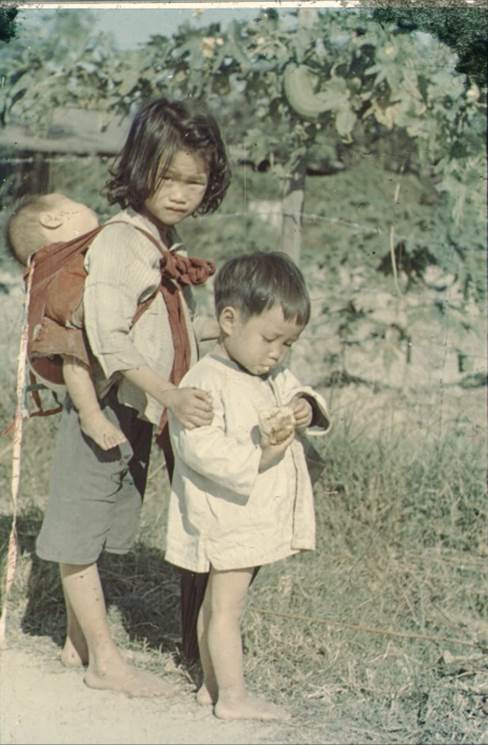

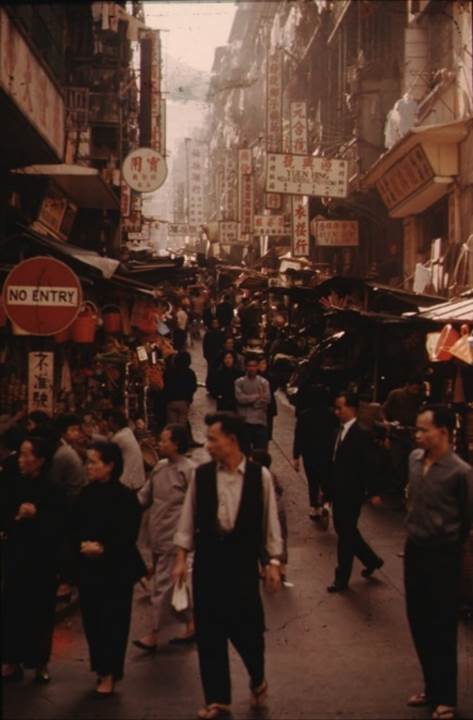

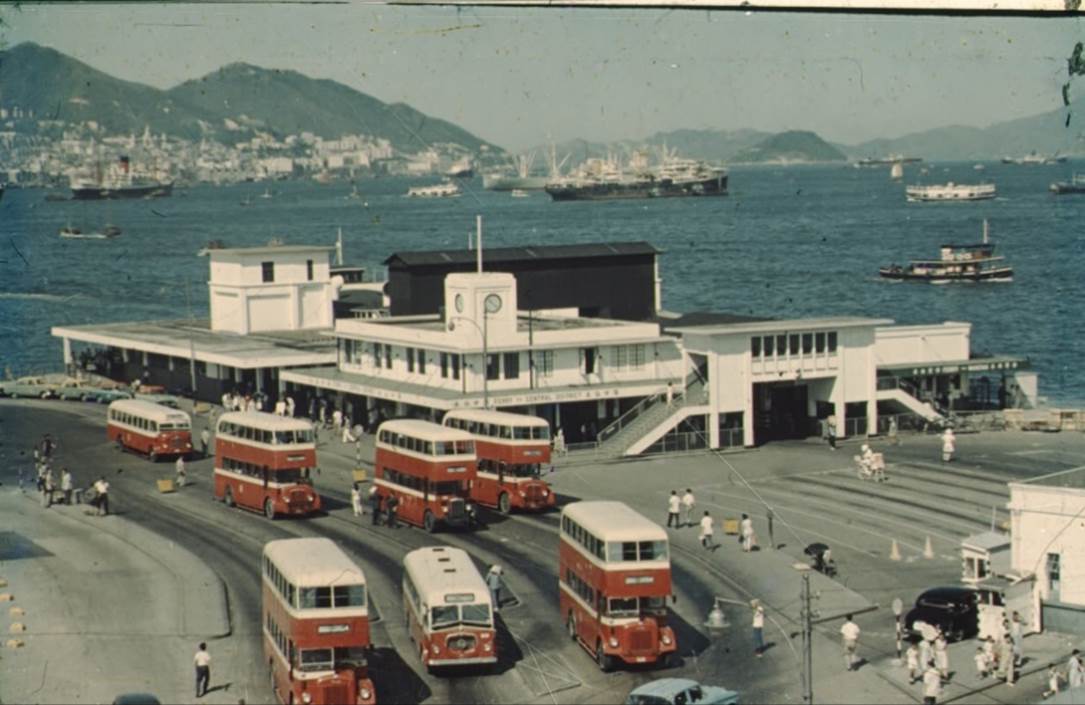

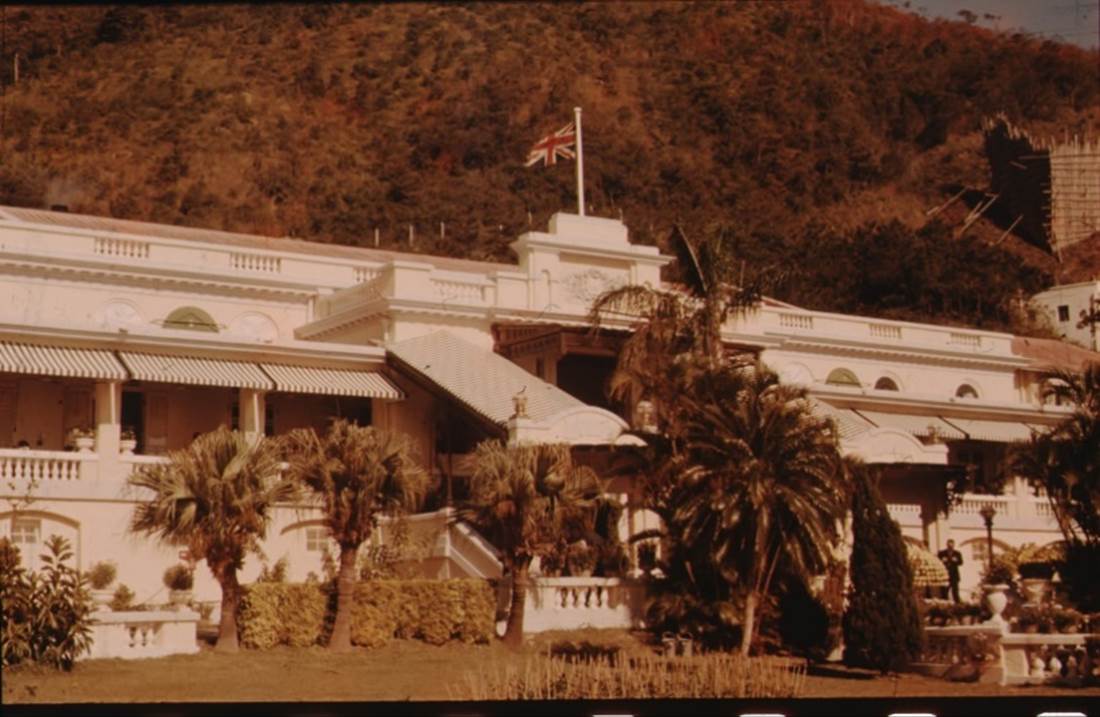

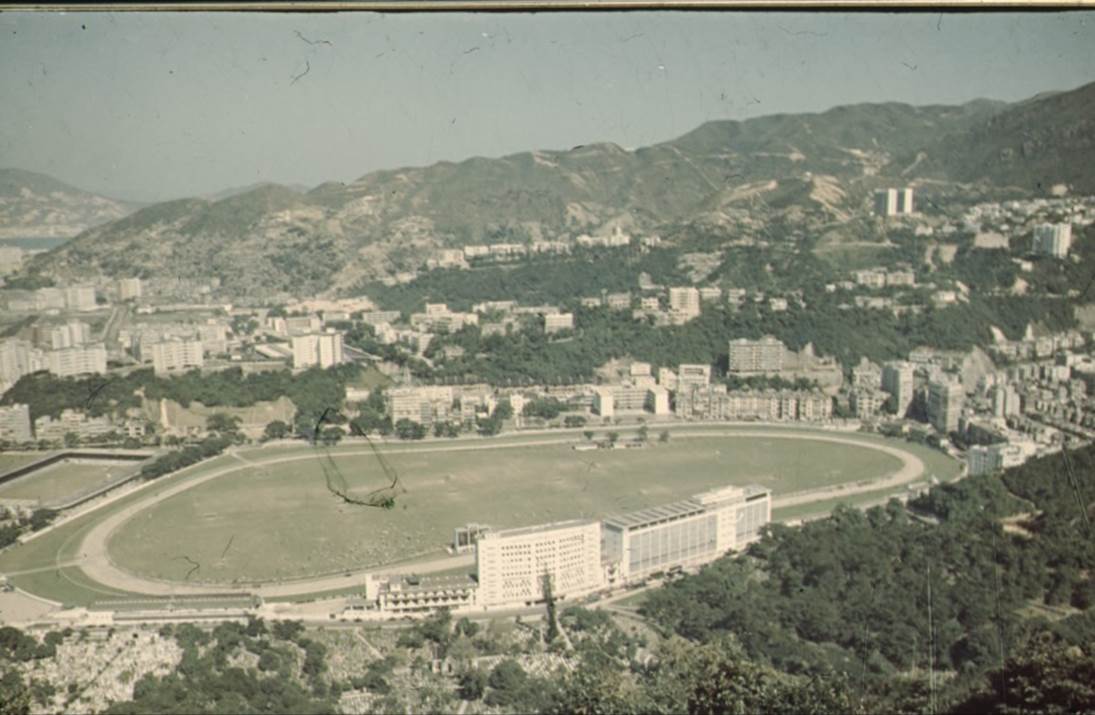

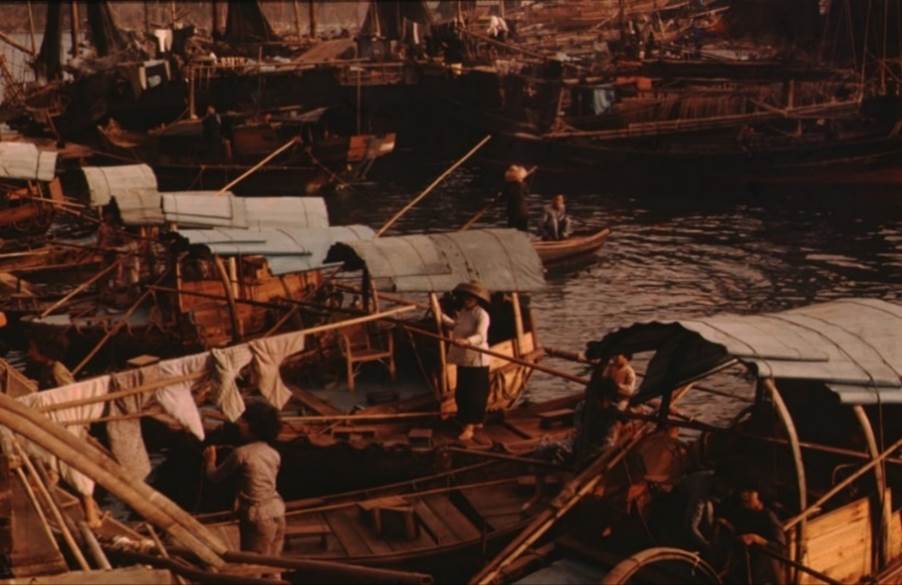

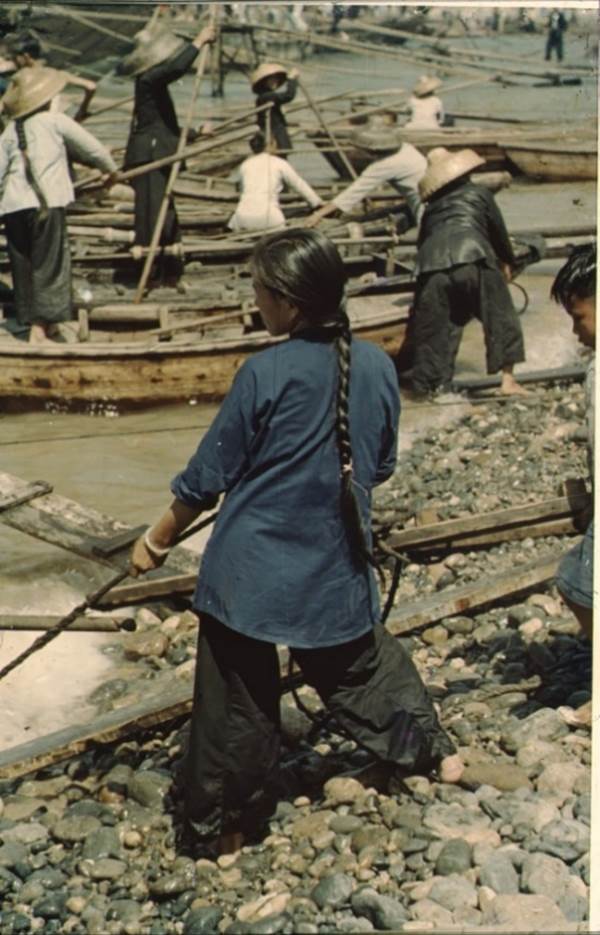

XXVIII – Hong Kong (1961)

XXVIV – The Journey Home overland (January to March 1962)

I – Switzerland (Christmas 1946)

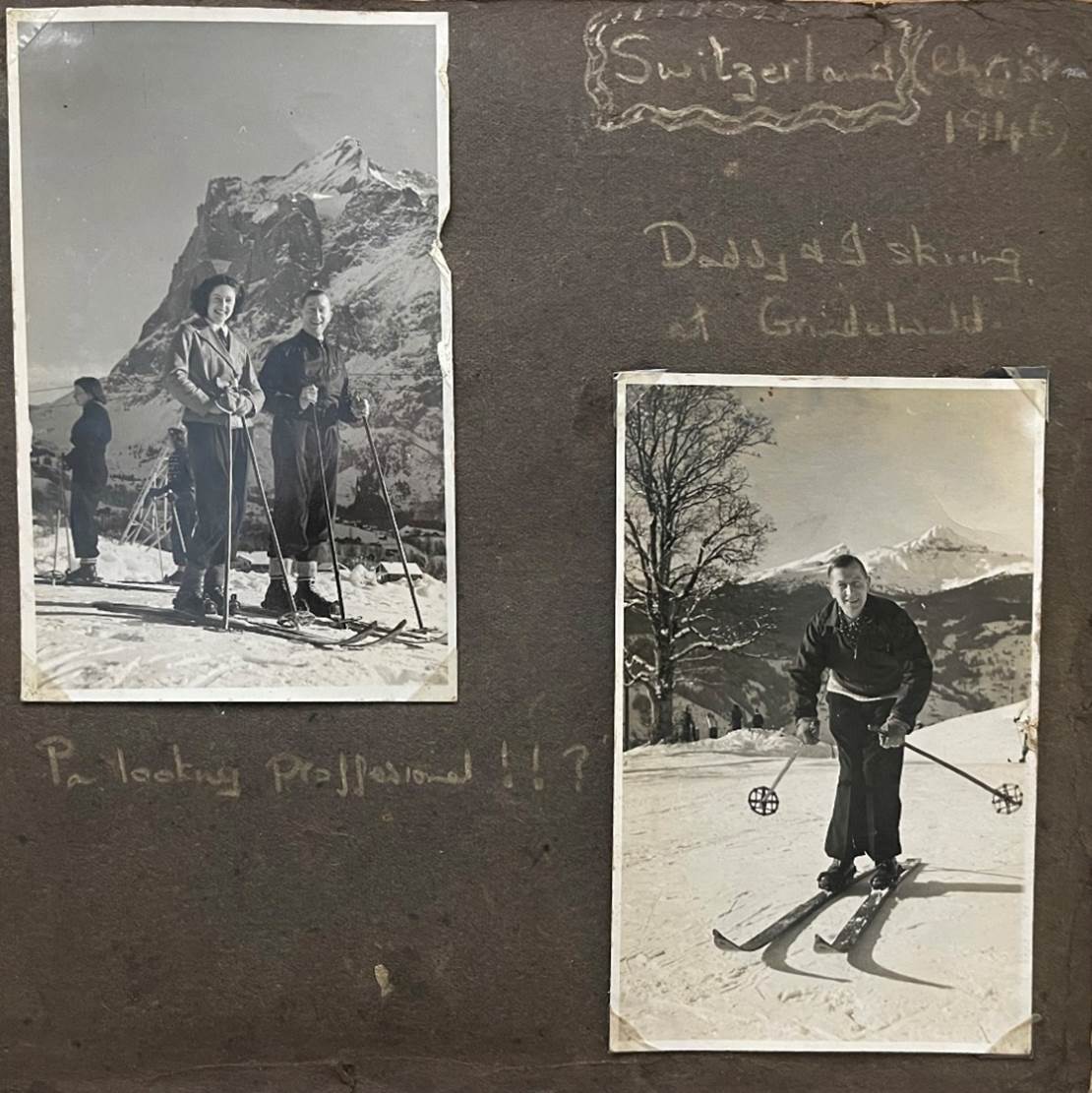

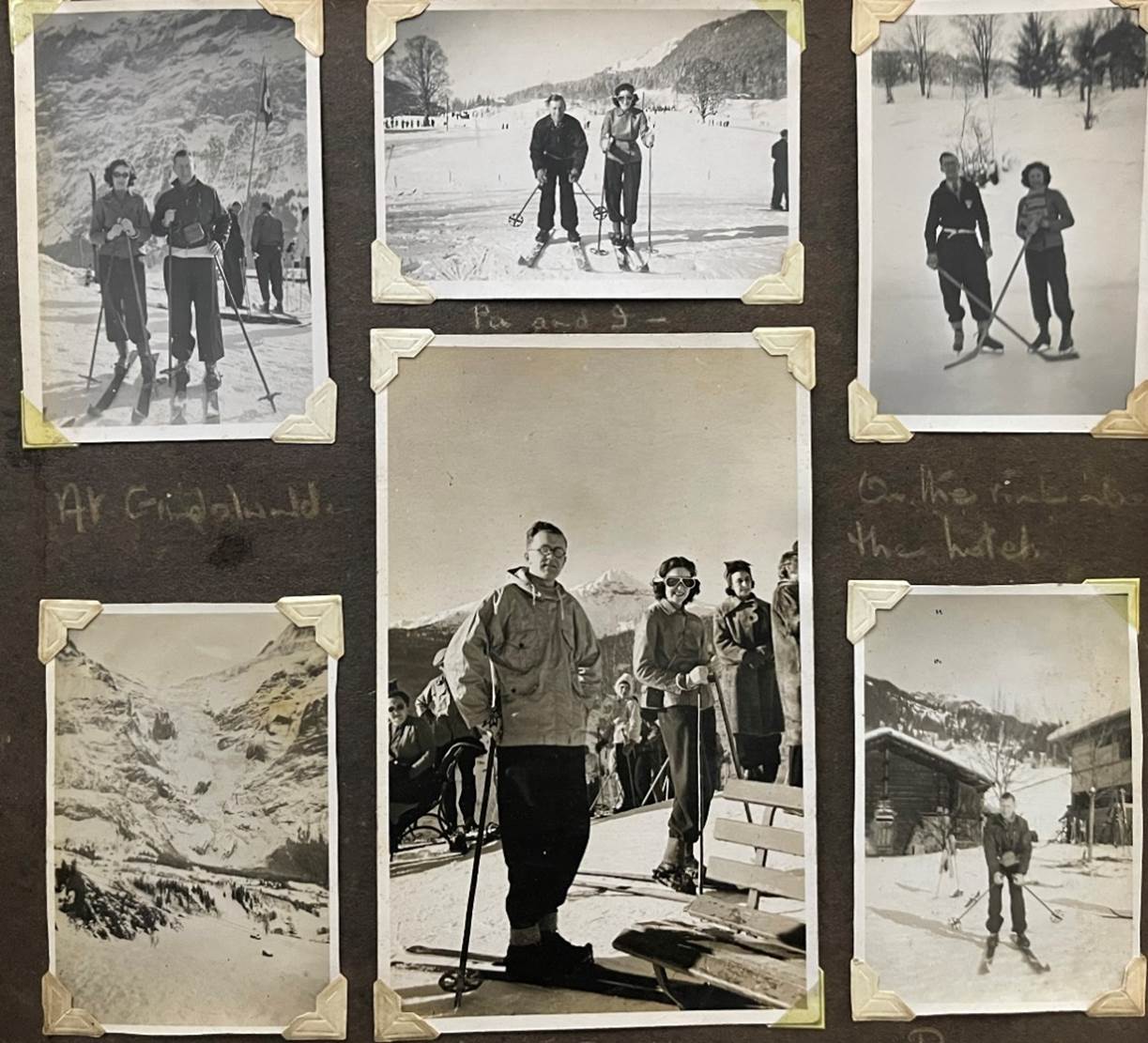

The year after the War, my parents and I went to Switzerland for the winter sports. Still at school this was the first taste of abroad and a great thrill after years of wartime austerity.

A vivid impression remains of the journey through France; of ersatz coffee, dirty trains, lack of washing water and general dinginess, and then suddenly a complete change from the moment we reached the Swiss frontier! Charming people, good food and cleanliness. Then our arrival at our destination, Grindelwald in the Bernese Oberland. We were met at the station by a horse drawn sleigh and driven through an unbelievably beautiful world of whiteness and ice crystals and the sound of bells to our hotel. Freezing outside, but beautifully warm as soon as we went indoors. Why is it that we in England have no idea how to make our houses warm and comfortable in winter. The Swiss houses with their double windows and enormous feathery counterpanes are the height of luxury when it is snowing outside.

The next day, a ride up the ski lift and then for my father and I, our first wobbly attempts at skiing. After a few days we were able to discover for ourselves the thrill of gliding downhill quite fast before we land landed in a jumbled heap at the bottom. Other memories include steaming cups of hot chocolate and creamy cakes, après ski, tea dances in ski boots at a very Swiss cafe near the hotel, of a trip to the Kleine Scheidegg by train and back on skis, five miles in all, along the side of some fearsome chasms, collapsing in the snow I might add alarmingly frequently, as more experienced skiers whizzed past to do the run in 5 minutes flat. The Swiss boy who had invited me on this expedition was a very good skier himself and gave me a good deal of skiing instruction with remarkable patience on the way. It was a drastic way to learn and rather like being thrown in at the deep end before you can swim. There is no alternative but to go on towards the town far below.

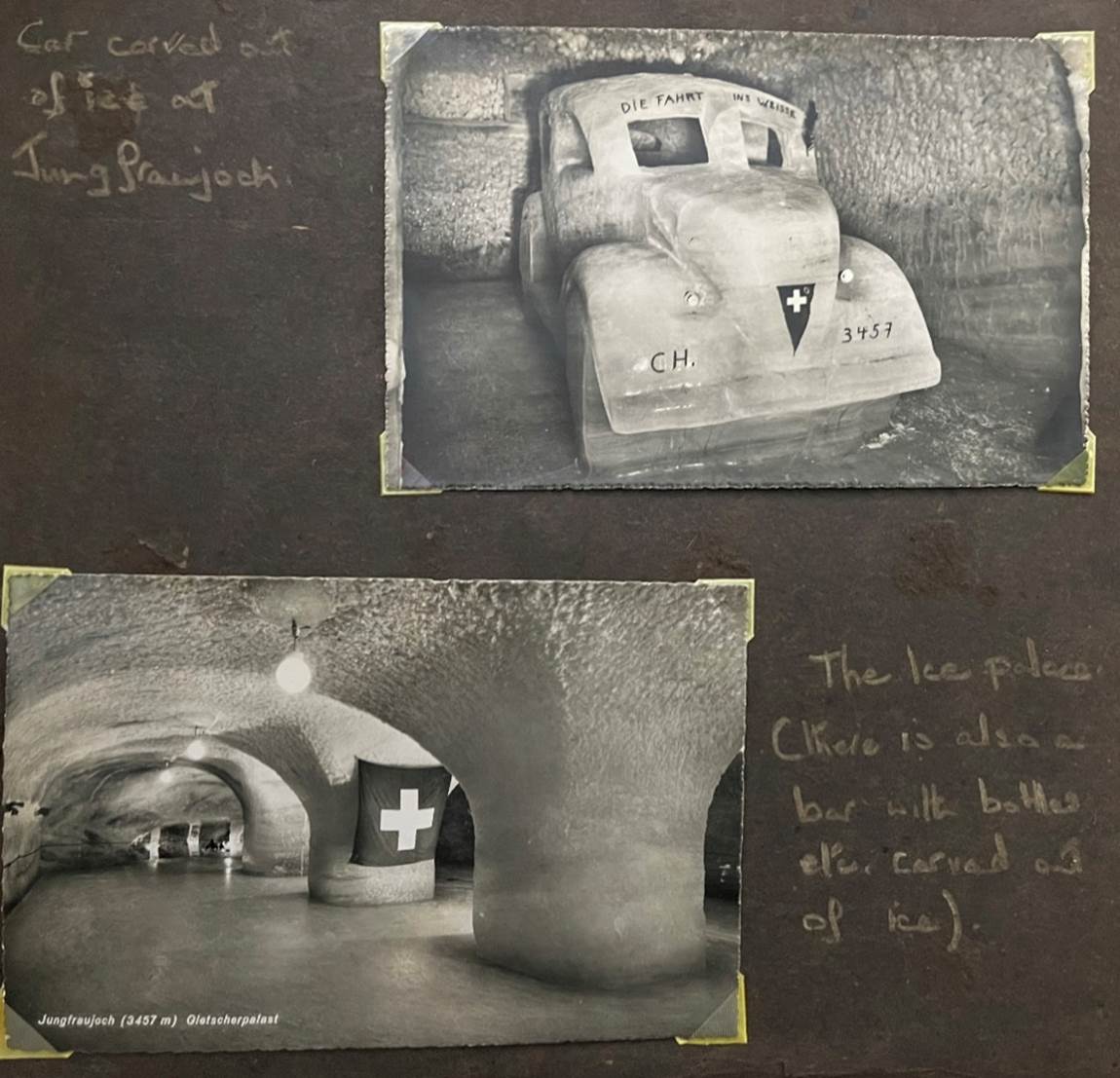

On another trip with my parents we again went to Scheidegg, with its curling rinks, glittering ski runs, and dazzlingly bright sun and then on by train through an endless tunnel carved through a mountain to Jungfraujoch. At 11,000 feet this is a fabulous place with a breathtaking view. Breathtaking literally, as at such an altitude it becomes increasingly difficult to breathe deeply and after a short walk you become more and more breathless. The Saint Bernard dogs kept at the hotel have to be changed at regular intervals because the altitude affects them. The hotel is built on one side of the mountain peak and sitting in the dining room you look down a sheer drop to the valley far below under the hotel. You can walk right inside a glacier, which apparently moves a few inches every year. There is an ice rink there and a mock bar built of course out of ice with, need I say it, iced bottles and glasses. Also there is a full size car made of solid ice which you can sit inside with the most realistic steering wheel and controls. Then down the mountain again on a train journey made possible only by a remarkable feet of engineering.

Christmas at the hotel was fun with lots of organised gaiety, but the Swiss in fact make much more of New Year (another Hogmanay) and a small pig was chased round the dining room by the chef, the unfortunate victim appearing later on a large dish.

Other memories include a visit to Interlaken with shops full of peacetime frivolities, though as a holiday resort the town only comes into its own for the summer months. A visit to a watch makers with every kind of watch and clock made by the world famous Swiss craftsmen. One I remember could go for a year without winding and tell you the date, time and a lot of surplus information besides. I also remember skating out of doors on a tennis court flooded and frozen over and a sleigh trip with my parents, again to the accompaniment of snowbells, to visit a nearby glacier of blue ice.

This was a lovely holiday and a memorable introduction to the continent. It is often said that the Swiss are charming because tourism is their main asset. Even if this is true they are still a delightful people and once you have been there, it is a country that will always draw you back.

II – Paris (May 1947)

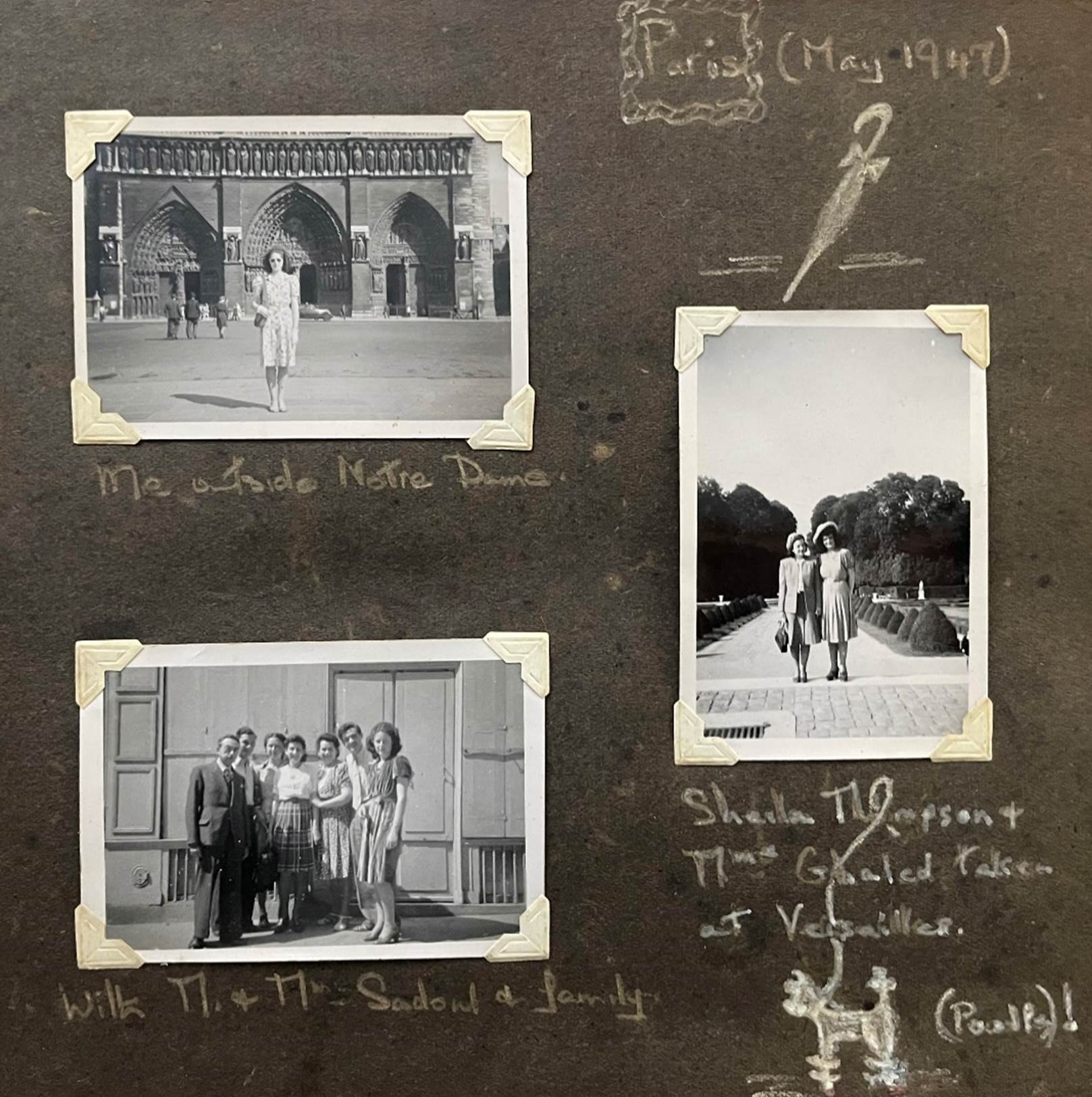

We left Newhaven on the Channel Steamer and were seen off by our respective parents. Sheila, who was nursing, was on holiday, and I - by the greatest luck - was missing two weeks of my domestic science course. Not being at all domestically minded at that stage, this added considerably to the enjoyment! Our destination, Paris, and a holiday with a French family.

We were met at Paris by ‘Papa’, who escorted us back to his house and introduced us to the rest of the family. ‘Papa’ spoke a little English and practised it continually at length, while ‘Mama’, their daughter and two sons, spoke not a word. As a result, our French improved in sheer self-defence, though interspersed by a good deal of sign language.

We were staying quite near the iced-cake Sacre Coeur and immediately started to work our way through a formidable list of sightseeing ‘musts’. Montmartre, the Louvre, Tiuleries, Notre Dame with its exquisite rose window; we saw Napoleon's tomb, Place de la Concorde, the Arc de Triomphe, Rue de Rivoli and the rest. We were also taken around one of Paris's oldest hospitals, the Hotel Dieu, a rather grim building by the Cathedral of Notre Dame. The wards were full and most depressing, particularly the eye ward where the cataract patients were sitting in bed immobile with their eyes bandaged, waiting to know whether their operations had been successful. The operating theatre was very well equipped and modern, which at least was a comforting thought. We visited a typically Parisienne fair which extended noisily right down the grass verge in the middle of a wide street. Everywhere we were struck by the design of Paris, particularly around the Arc de Triomph where the roads form a star from that central point. It is far safer to view all for all this from, say, the top of the Tour Eiffel, as standing on the ground you spend most of your time avoiding the Paris taxis, which race along as an alarming speed and generally come straight towards you for the fun of it.

Paris with its elegant air, has a gaiety that is quite unique - its language voluble, volatile and essentially feminine. If Paris is a woman, she is one with ridiculously high heels, leading a poodle, while London is, of course, a man with a bowler hat or a pearly king. The market, the pavement cafes, fresh croissants for breakfast, artists by the Seine, and vin ordinaire all mean Paris to me.

The family took us on various sightseeing trips, and we also set off by train to Versailles to visit a friend of a friend, who had been an opera singer in her day. She was still very dramatic and theatrical and somewhat overwhelming in a small room. After a delicious lunch she took us to see the Palace of Versailles and she showed us everything with sweeping knowledge and panache. Unfortunately, after tramping round Paris for days, added to endless miles of Versailles, we were so completely exhausted that eventually we were unable to take another step and missed seeing Le Petit Triannon. This reminds me of a rather charming ghost story I once heard. Two English ladies (who must have been equally tired and dropped to sleep) had visited La Petit Triannon, and both declared quite firmly afterwards that they had seen Marie Antoinette, her shepherds and shepherdesses, quite clearly. The odd thing was that they were able to describe details afterwards found to be correct, which they could not have possibly known - for example, the costumes worn and the gardens exactly as they were so long ago. Could it only have been a dream? I wonder.

We went to a Roman Catholic service at the famous Madeleine, and were amazed at the number of collections there were. So many that we began to wonder whether you could just get up and go round with the hat yourself!

Then a glimpse of haute couture. We were lucky enough to be given tickets to see Heim’s spring collection. The whole thing was conducted with great aplomb and finish, an unforgettable picture of colour, line and liquefaction.

We decided that we couldn't leave Paris without paying a visit to the Folies Bergeres, and were duly escorted there by a Monsieur and Madame, our hosts. In fact, old ‘Papa’ had been persuaded quite easily with a gleam in his eye, and ‘Mama’ came along too, to keep an eye on him. The show itself was extremely well produced, with statuesque beauties on the stage. The theatre itself was a plushy, Toulouse Lautrec atmosphere.

We also went to l'opera. Up the famous staircase and into the auditorium. A wonderful white tie and diamonds atmosphere about it all, with an enormous chandelier overhead and eternal air of expectancy before the curtain rises.

And then back to reality with a bump. For some days before we were due to leave for home, there were rumours of yet another rail strike. This possibility soon became a reality and we were stranded, nobody knew for how long. We decided we must fly back, but a great many other people had the same idea. We went to the British Embassy only to find it packed with would be travellers. After waiting for what seemed like an eternity, we were given tickets for the flight home that night. At all the airport, Sheila found that she was to travel in a tiny single engined aeroplane, while I was to go in a larger one. Poor Sheila felt every bump on the flight and she became steadily greener. The plane was so minute that she was sitting near enough the controls to notice the petrol gauge. It was pointing at nought and they were still over the sea. It was obviously out of order and fortunately she landed safely. In spite of such a fright, it was amusing to look back on with feet well and truly planted on terra firma.

My next visit to France on holiday was to be on my honeymoon, but a good many exciting things were to happen, and a lot of travelling was still to be done, before that eventful day.

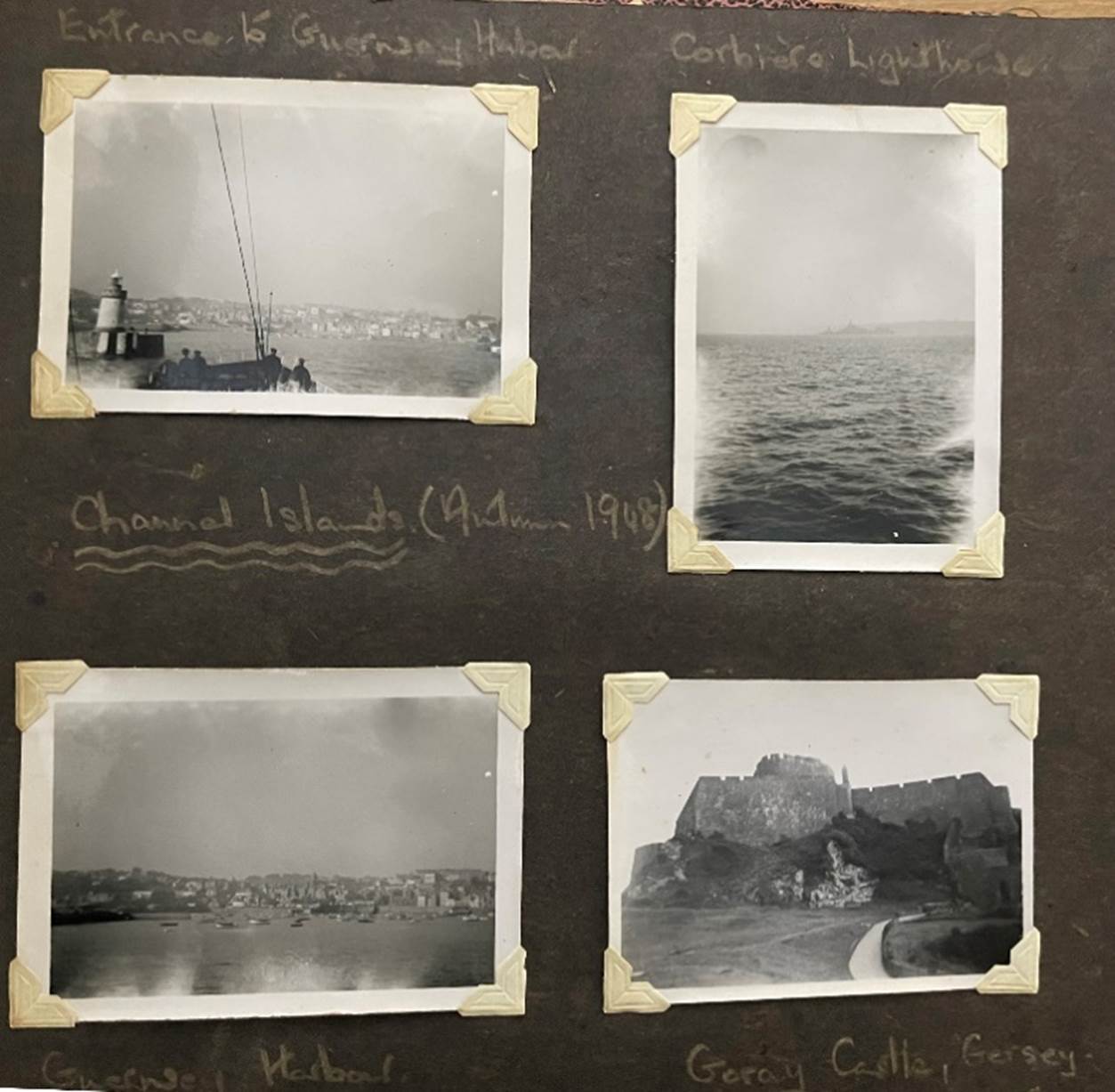

III – The Channel Islands (1948)

My parents and I reached the Channel Islands after a very choppy sea, crossing in late September. Our destination was Jersey and its capital St Hillier. Jersey, Guernsey, Alderney, and Sark - the very names of the islands bring to mind lush green meadows and sleek, contented cows peacefully chewing the cud, or gazing into space with their soft velvet eyes. The tiny island of Jethou is privately owned, and Herm is rented from the crown, and in winter, the tough, rocky little islands stand firm as the waves pound their shores. The islands are full of tradition and history, French and English closely interwoven. The people originally come came of Norman stock, and though the official languages now are both French and English, many of the people in the country districts only speak Norman patois. The Channel Islands are, in fact, the oldest possessions of the crown, and through the centuries the Islanders wholehearted patriotism and loyalty has never dimmed. In modern times, there is a very little crime and St. Helier is the only town with paid police! Elsewhere, the honorary constables of the parish keep order quite easily. Many retired people from the United Kingdom settle in the islands, lured there initially by low taxation; drinks and tobacco too are very cheap.

Our hotel was overlooked looking the sea at Saint Helier, and being rather late in the season most of the other holiday makers had left. On the ship we had met a very nice family who invited us to tea at their farm. They lived in an attractive old farmhouse with shutters at the windows, which gave it a distinctively French appearance. They had been there through the war years and told us how close the islanders had come to starvation. The son, in his early 20s, had just recovered from tuberculosis, which we imagined had been caused by his wartime experiences. All the men who were not born on the islands were put in concentration camps in France, or taken to Germany as slave labour. The prosperity of the islands depends very largely on agriculture, and very quickly life appeared to return to normal. In 1948, the small farmer already seemed prosperous again, with a high standard of living, though land and rents there are always very expensive. Jersey and Guernsey cattle are, of course, famed far and wide for the quality and quantity of their milk, but we were told that it is no longer profitable to make butter for sale. There are a few gates and fences, and the cattle are tethered by chains, and are frequently moved so that no grazing land is wasted. In winter, many of the cows wear coats to keep out the cold! The farmers concentrate to a great extent on tomatoes and early potatoes, and a great deal of labour is imported from Britain and France to help with the harvesting. Welshman and Bretons (as we were told when we were living in Wales) can understand one another quite easily, as the languages are so similar and have many common links with the past.

Saint Helier is a clean, prosperous and bustling town, with a modern harbour, narrow streets and good shops; also modern theatres and cinemas. There is also motor racing and sailing nearby to divert the visitor. Flowers abound and flourish in the clear island air and in summer there is a pageant of flower bedecked vehicles and floats, the blooms later disintegrating in the hilarious Battle of Flowers, a similar carnival to those of the Riviera. All round the coast are sweeping bays with long sandy beaches and high cliffs. We drove around the island and saw them all, St. Aubins, St Ouens, Plemont, St Brelade’s and Bouley Bay, and returned to Saint Helier via the rugged Old Castle of Gorey. We also saw the 6th century Fishermen's Chapel of Saint Brelade’s, which has comparatively modern frescoes on the thick walls, (only about 600 years old!). The Chapel is steeped in legend, and one could believe almost anything of this lovely, musty age-old place. It is amazing to think that it has stood firmly through 1,400 years of history, and was already an ancient monument in the reign of William the Conqueror! We walked round a vast underground hospital, built during the war by Russian prisoners, many of whom died in its construction. It was never used, and when we saw it, it was just a vast, echoing, massive, concrete. A constant reminder of the wasted effort and futility of war.

The ship passed Corbiere lighthouse and called at Saint Peters Port, Guernsey on the way home. The town rises up steeply from the water, and it was with regret that we took a last look at the harbour filled with fishing smacks and sailing boats, as the ship pulled slowly away and headed out to the open sea.

IV – Egypt (1949)

I had joined the Foreign Office three weeks earlier with the fervent hope of being sent abroad, somewhere exciting, as soon as possible. By a great stroke of luck, a secretary was needed urgently in Egypt, and so I found myself en route for Cairo by air to do my first ever job. I flew out by Dakota, without the luxury of a pressurised cabin. Inside the aeroplane it was either far too hot or freezing cold, and feeling rather ill, I began to have second thoughts about this thrilling expedition! However, after 14 hours we reached our destination, and the sight of the desert and pyramids below in the white misty light of morning, soon blotted out the discomfort of the trip, for this at last was the East!

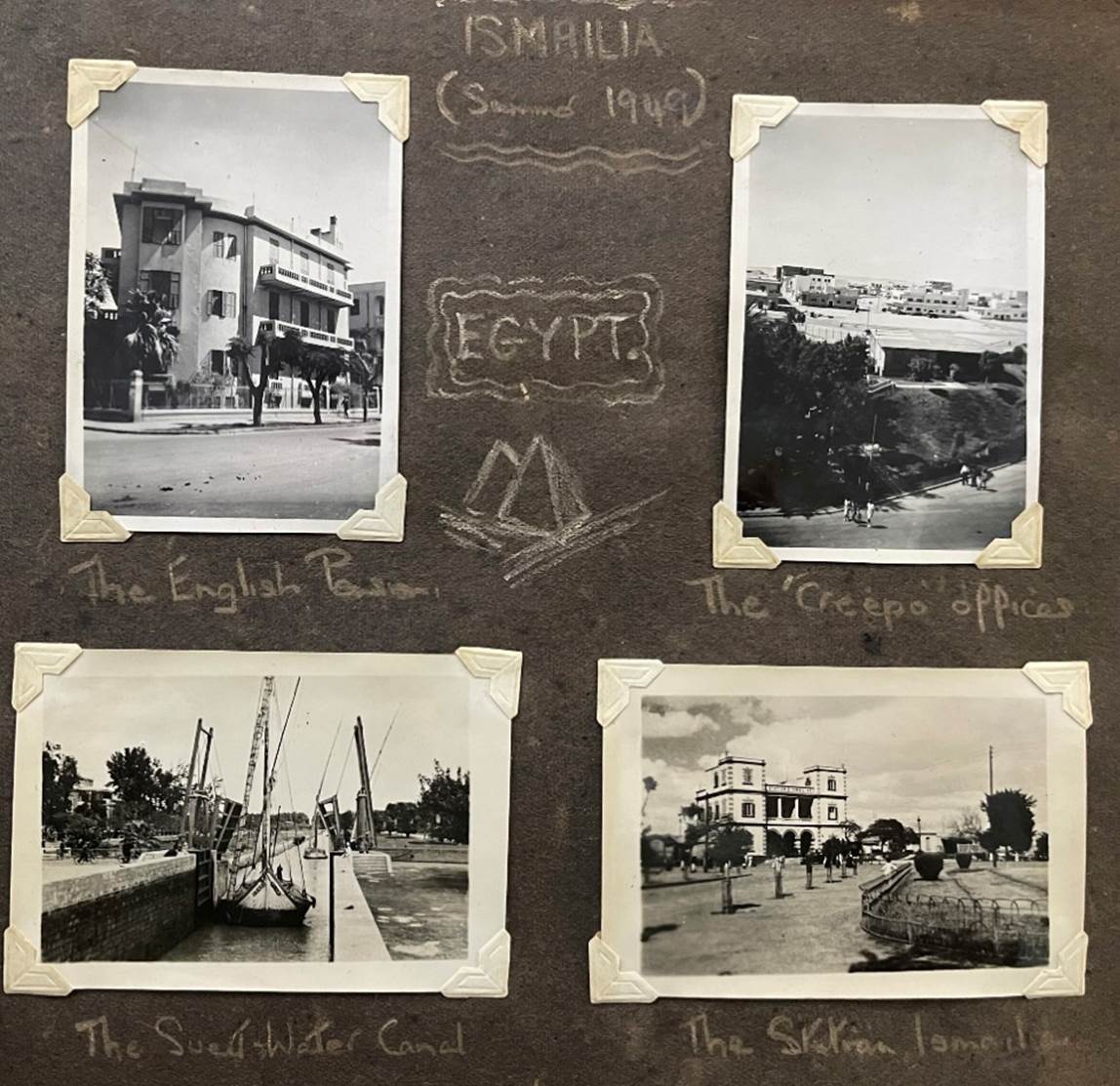

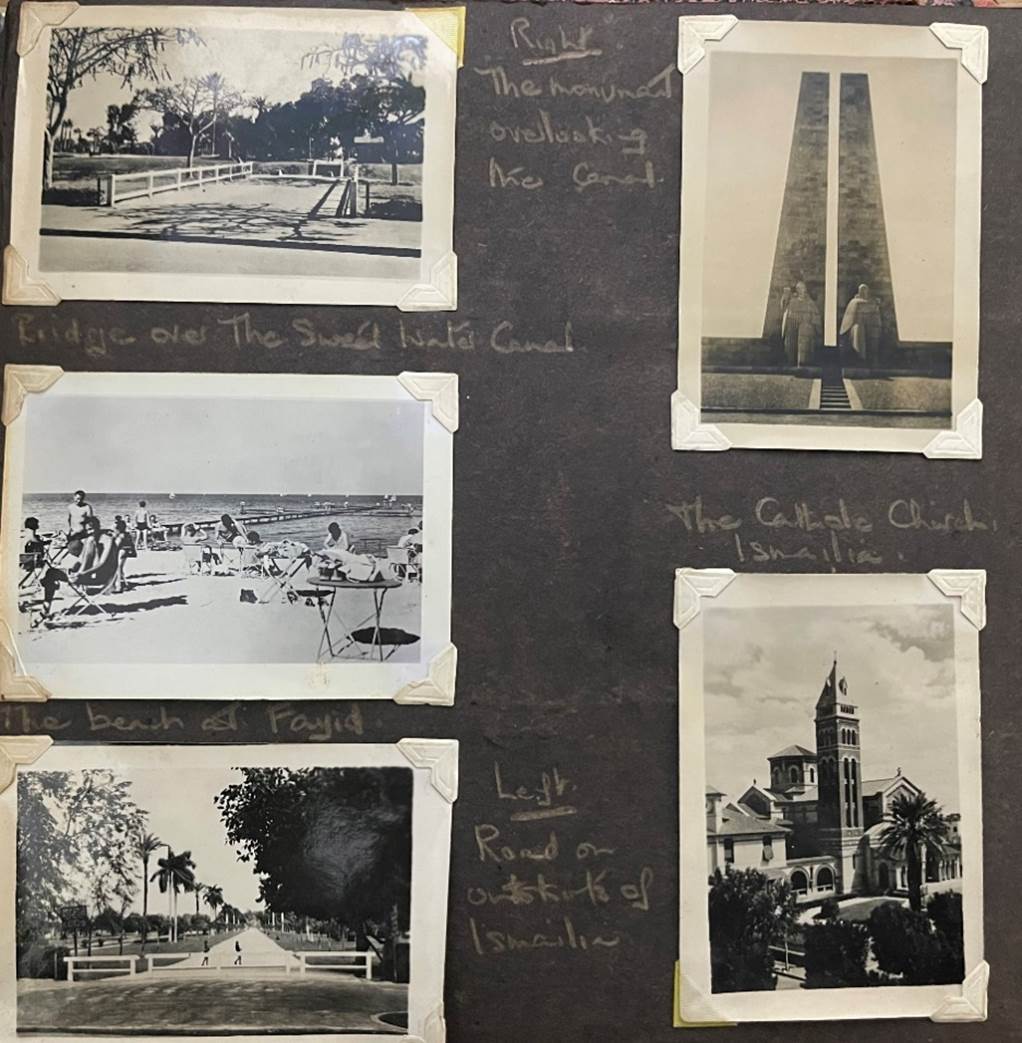

On arrival, I was met by the head secretary in Cairo, a charming girl, and after breakfast at the Semirimis Hotel, set off by car, for Ismailia, 50 miles away, where I was to be seconded.

The Middle East with its jostling, teeming humanity, its abject poverty and fabulous wealth, its women in purdah draped in deepest black, and men with flowing gallabea and red flower-pot tarbush; its smells, its flies, its goli goli men, and above all its essentially Moorish flavour, seems to me to contain the very essence of the ‘East’ in a way that the Far East never does. The Egyptians perhaps lack the finer qualities of the true Arab. The first impression one gets of Egypt is of bright, garish colour with endless miles of sand and dust as you drive along. To a naive and impressionable English girl, everything seemed very strange, mysterious and exciting.

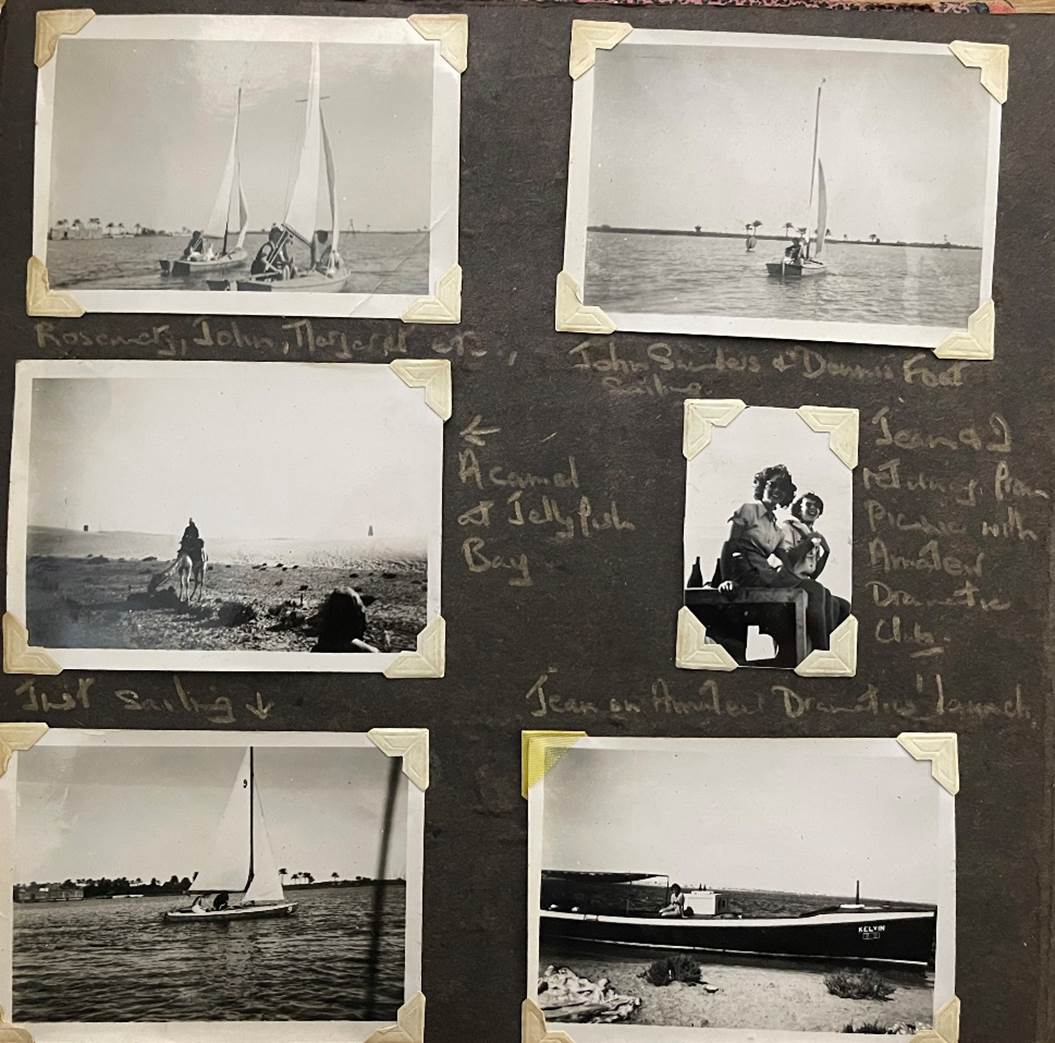

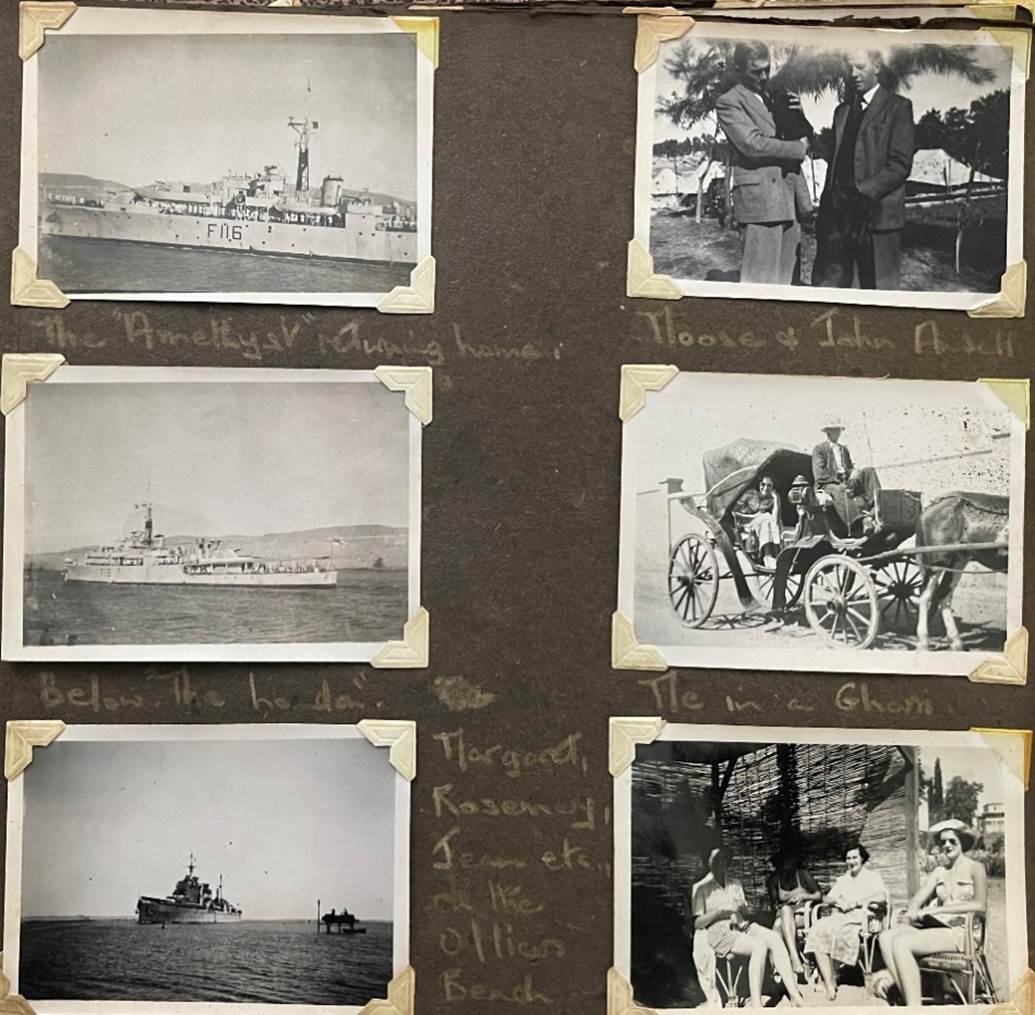

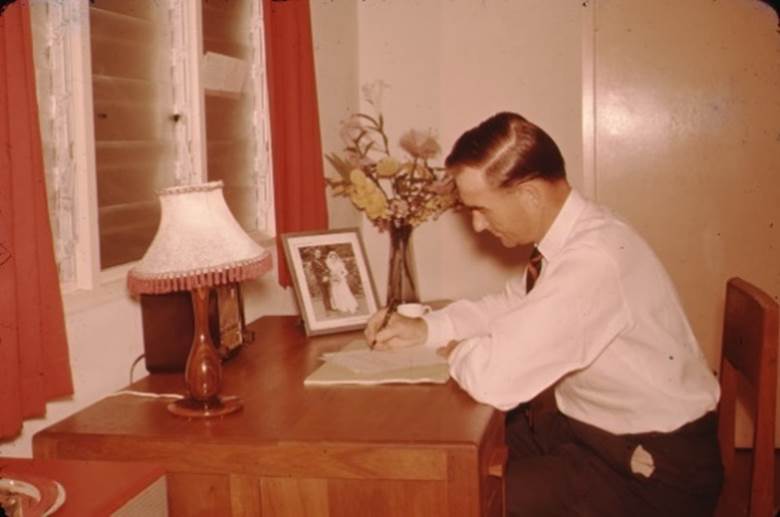

Then Ismailia on the Suez Canal. This is to be a journal of travel impressions and not of work. So enough to say that my job was interesting, busy and varied, also extremely hot and tiring on occasions when the electricity failed, which it frequently did, stopping all the fans, at a temperature of about 105 degrees. I met a great many people, by far the nicest of course, being my future husband. He had only recently passed out of Sandhurst and we had both left England on the same day, though he arrived after me by ship. Brian Montgomery, Monty’s brother was our administrative officer and he and his wife looked after their girls very well, inviting us often to lunch, drinks or sailing.

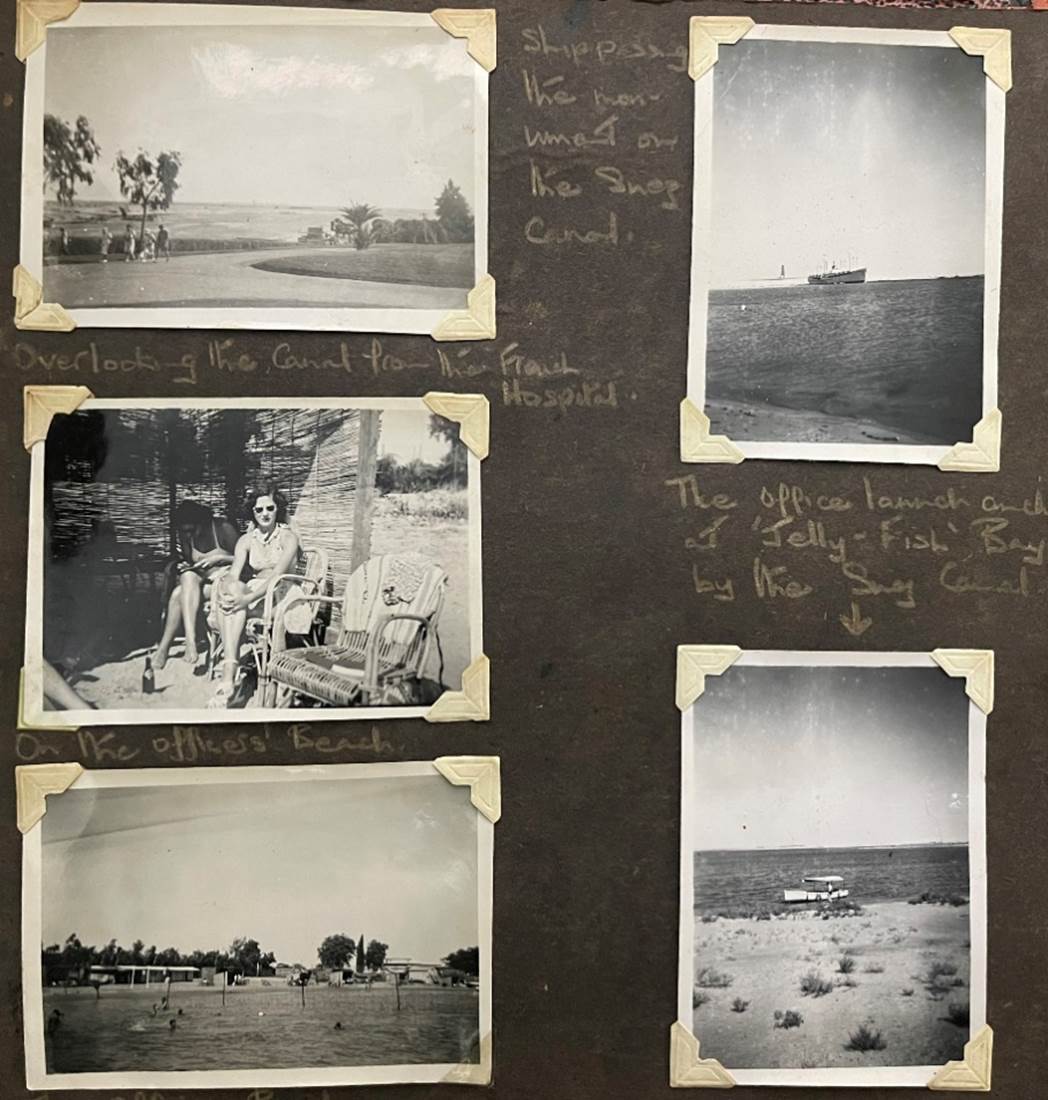

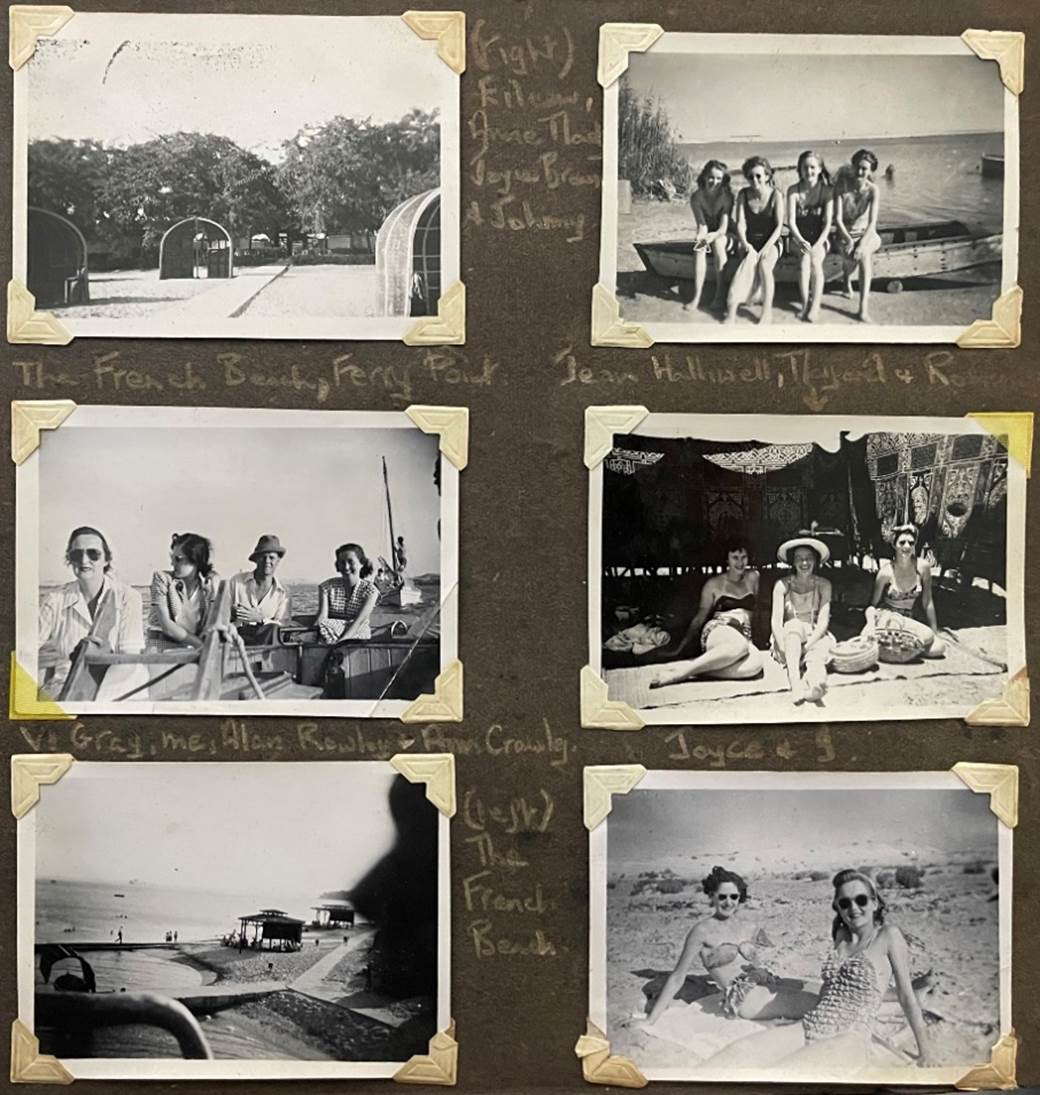

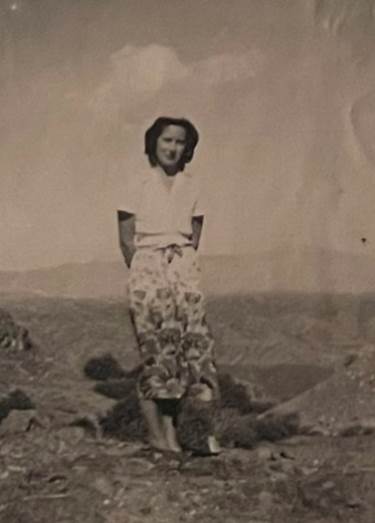

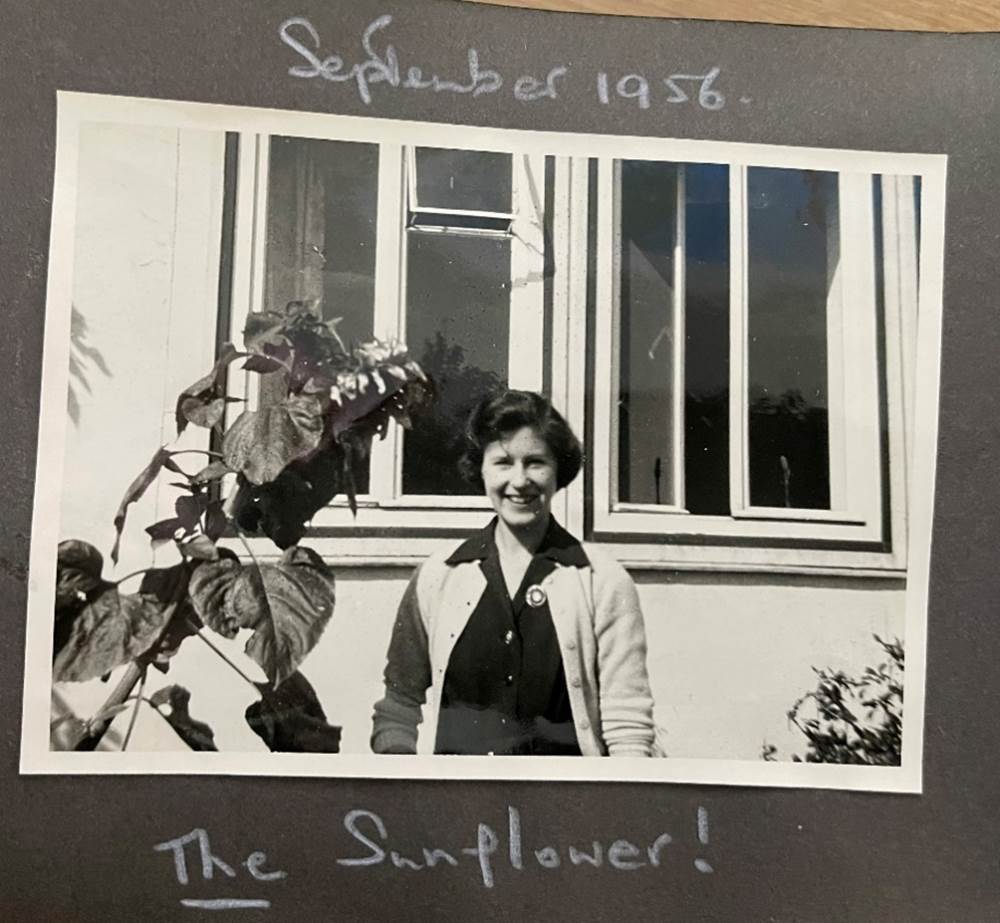

Anne Buckingham

The Canal Company pilots particularly lived in great luxury in Ismailia, and normally did a long tour of up to twenty years out there. The canal was considered to be a prize, and the peak of a pilot’s career. Many of the French houses had their own swimming pools, and it must have been a great blow to many of these families to have to leave Egypt so soon afterwards. The town of Ismailia was quite small and not impressive. The best place to be was the French beach facing onto the bright blue Suez Canal, and there was also the officer's beach, which was not quite so exclusive. The French beach, I remember, had the most marvellous igloo-shaped shelters made of cane to sit inside; the only other place I have seen anything similar was on the North German coast, but there it was essential to keep out the icy blast and not the sun!

We only worked in the mornings and three evenings a week from five to seven thirty pm. This meant that all our afternoons were free for swimming or sailing, and we had staff cars at our disposal to take us wherever we wanted to go. On one occasion, the horn of one of these cars suddenly started to blow and continued right through the town - nobody even bothered to look round to see what the noise was! Horns are always blown almost continuously anyway, in the normal course of events in Egypt. Sailing on Lake Timpsah was wonderful. And there were enticing sandy islands to visit for picnics and bathing. For dancing, there was the Greek club with its rooftop restaurant, the sailing club, and best of all, the French club, which was run by the inimitable Monsieur George. Late at night, or on special occasions, he would sing ‘La Mer’ and other delectable French tunes in the most delightful way. Dancing on a small floor, out of doors and in such surroundings was quite perfect. Unfortunately Monsieur George became very anti British at a later date when the troubles there came to a head.

The Sweetwater Canal, which runs between Cairo and Ismailia, is a distinctly un-sweet stretch of water. There was a story told of a carload of European travellers who swerved off the road, landed in the canal and as a result had to have 14 injections to ward off every possible disease! Most of the locals wash themselves and their clothes quite happily in it, and suffer from bilharzia as a result, though they seem to become immune to a good many other diseases.

Fayid, about 20 miles from Ismailia was a big Army base, and officers from Ismailia used to go there periodically to do CinC’s guard duties. One of these included the guarding of the perimeter defences to prevent ammunition and stores from being stolen. The rich sheiks, anxious to make a profit out of arms deals, employed almost subhuman fellaheen from the desert to slide in and steal. This was a dangerous task as they had to climb in through the barbed wire; they were often covered in grease so that they were very difficult to catch. If seen, they were shot on site, and if they were wounded and caught, would beg to be killed and not handed over to the Egyptian authorities, a preferable alternative to being left to rot in the local gaol.

And now, memories of Port Said - the enormous de Lesseps statue in the harbour gazing down on his handiwork; a glimpse of the Arab quarter (then out of bounds to Europeans); the big hotels by the harbour such as the Moorish Eastern Exchange; and the famous Selfridges of Port Said, Simon Artz, whose main customers are tourists from visiting liners. We had lunch at a restaurant on the roof of one of the nicest hotels, with a wonderful view across the water, and afterwards crossed by ferry to Port Tufik across the harbour, to bathe at the club.

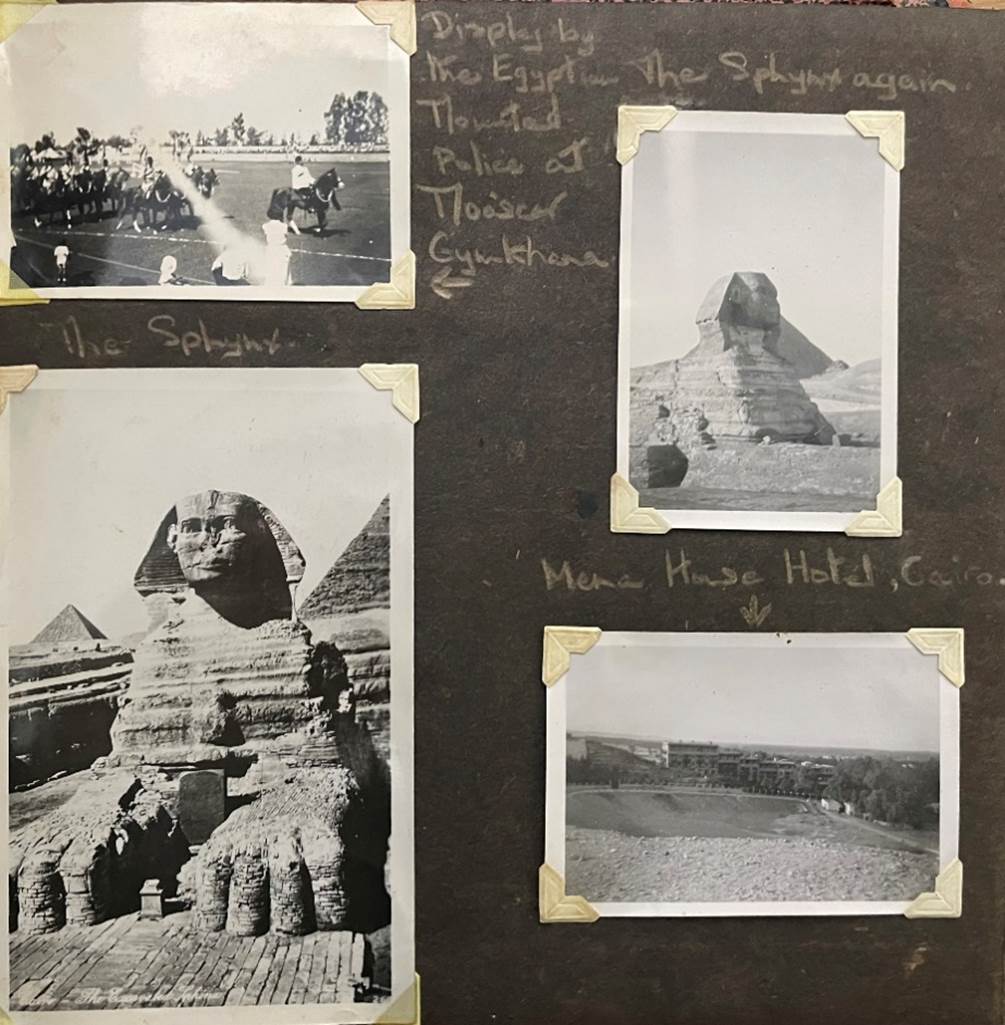

A visit to Cairo, memories of the famous Muski with its gold and silver, its intricate inlaid boxes and other mosaic patterned knickknacks; the Muski with its teeming life, its bartering, its sudden air of leisureliness as you sip Turkish coffee and decide that you cannot possibly buy all the things that entrance you; the sight of kebab sizzling on a spit along the street; and old man contentedly puffing at a curly and foul smelling hubble bubble pipe; Moorish ironwork and doors of swaying beads; and then above the bustle and clatter of life, the sound of the muezzins calling the faithful to prayer from a nearby mosque. Perhaps it is Ramadan, the month when Muslims throughout the world fast during the hours of daylight. The Old Shepherds Hotel was still standing when I was in Cairo and was unique in the same way that Raffles is unique in Singapore. The British still used the elegant Turf Club too, but now, of course, we are no longer persona grata.

Anne Buckingham in the desert

I shall never forget a visit to the museum to see the sarcophagus of Tutankhamun and the exquisitely elongated and beautiful Nefertiti. The colours were vivid beyond belief and were quite undimmed after so many centuries. The objects found in the tombs of the kings were of great variety and interest, and anything they might need in the next World was buried with them. The discovery of Tutankhamen's tomb, the curse on anyone opening it, and the strange deaths of the archaeologists involved, make the truth seem a good deal stranger than fiction. As a result of this thrilling discovery, we have been left with an amazingly clear picture of life as it was lived in the time of the Pharaohs.

A trip to the pyramids included the inevitable camel ride, after a visit to the luxurious Manor House Hotel nearby. At that time, excavations were being carried out between the paws of the Sphinx and sometime later an amazingly well preserved barque was found. I remember walking up an endless slope into the heart of the Great Pyramid, and finally reaching the tiny central burial chamber, completely empty, but with a cold and sinister chill pervading it. Each stone block of the pyramids is enormous, and how these were ever lifted into position or transported at all entirely by hand, is of course one of the great wonders of the ancient world.

Unfortunately I did not go down the Nile to Luxor and Thebes, where such an amazing collection of tombs were excavated; the trip by boat takes 5 days and from all accounts it is a quite unique experience. Another so far unfulfilled ambition, a visit to Petra in southern Jordan, the famous ‘Rose Red City, half as old as time’ with its truly fabulous ruins.

My future husband, Martin, visited Mount Sinai while he was in the Middle East and has described St. Catherine's Monastery, where life today has changed very little since the time of our Lord. The Greek Orthodox monks still grind their own corn and are self supporting, apart from the occasional visits of camel caravans with stores. The only way to get to the monastery is on horseback, or by driving over rugged tracks. Martin went there on an army exercise which entailed a considerable amount of careful map reading. The library there contains a remarkable collection of books and ancient manuscripts. The Codex Siniactus was unearthed there; before the recent discovery of the Dead Sea Scrolls. This was reputed to be the oldest collection of writings in the world. They were taken from Saint Catherine's Monastery to Russia in the 15th or 16th century, and were later bought by the British Museum, where they are now. The tomb of Saint Catherine behind the altar in the Chapel, is of solid silver, and in a side Chapel the roots of the Burning Bush are also encased in silver. All provisions used to be hauled up in a hole in the wall of the monastery, but are now taken by more orthodox means! The monastery itself is in a valley, with Mount Sinai towering above. There is a small Chapel on the top of Mount Sinai, and from there you can look down on the spot where the Golden Calf was made. The bones of the monks are dug up sometime after burial and are then neatly stacked in the Bone House. Saint Stephen, himself a grisly skeleton, is on guard at the entrance.

And now to Cyprus, Island of antiquity. The Middle East is certainly a storehouse of pictures of the past, for the 20th century traveller.

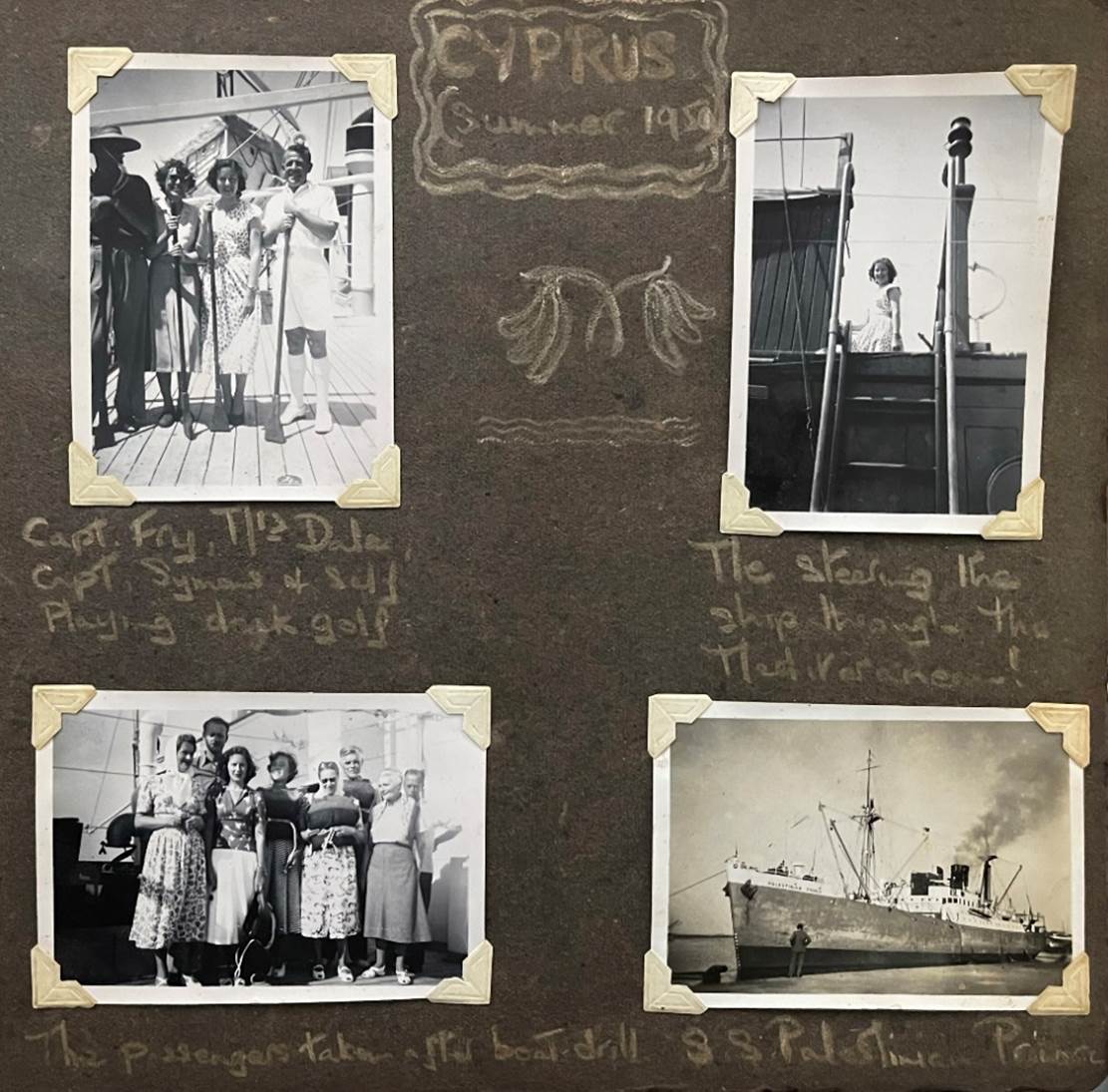

V – Cyprus (June 1950)

I went to Cyprus on holiday in June; to this lovely island were old and new, east and West are so intermingled. In 1950, all was peaceful, but even then the storm clouds were beginning to gather with the one word ‘Enosis’ scrawled on walls and hoardings. The Cypriots themselves were friendly and charming, and I think most of them would have continued to be, but were either terrorised or swayed by the inflammatory speeches of Archbishop Makarios, Grivas and his agitators, and by propaganda. The youths of Cyprus soon joined the terrorists imported from Greece by Grivas and the peace loving, ordinary people had little choice but to follow or to be killed.

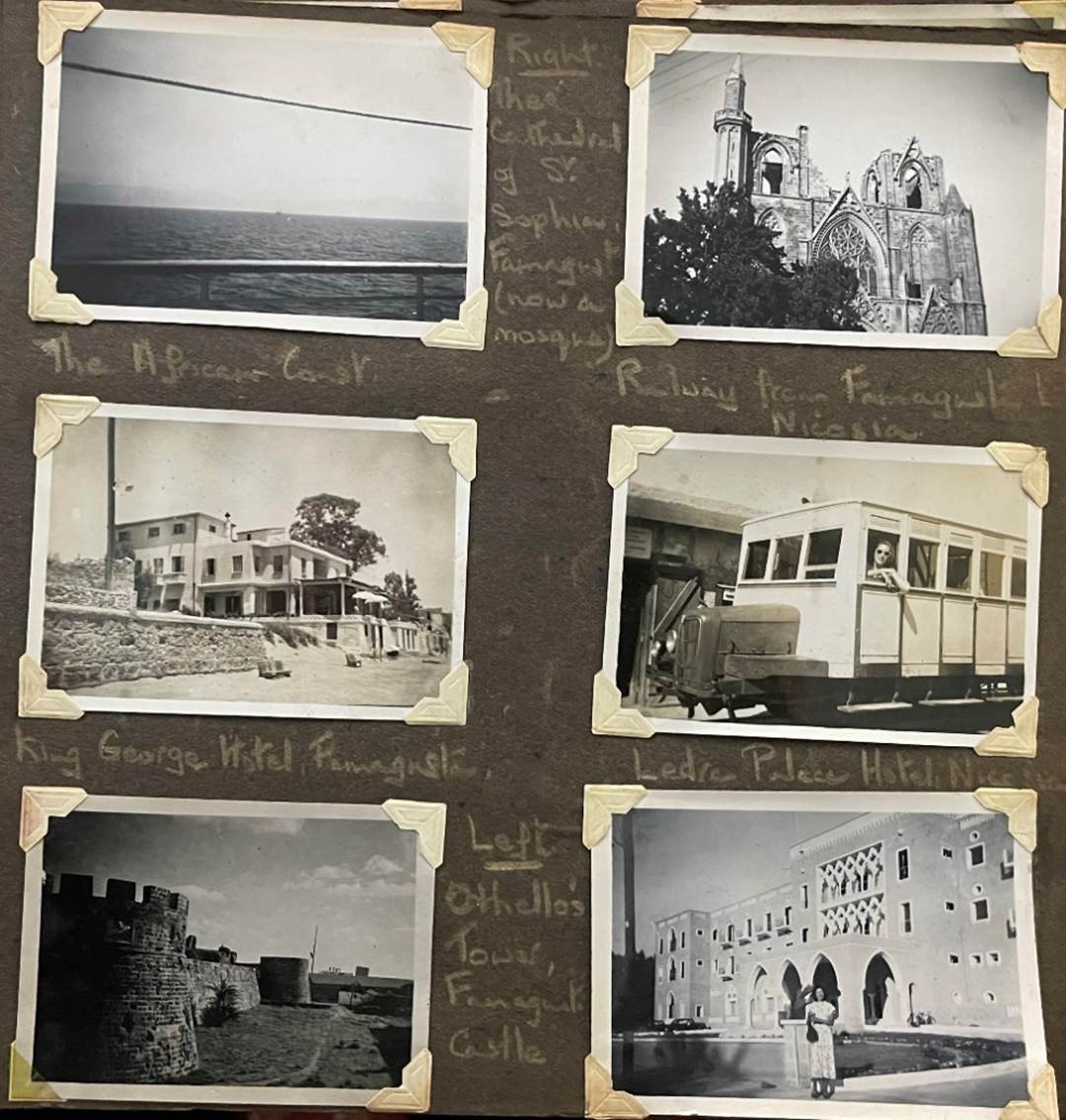

But now back to happier times, to Cyprus on holiday. After disembarking at Larnaca, we drove to Famagusta on the opposite side of the island. This is a very old walled town which has an attractive harbour and Moorish associations with Shakespeare's Othello.

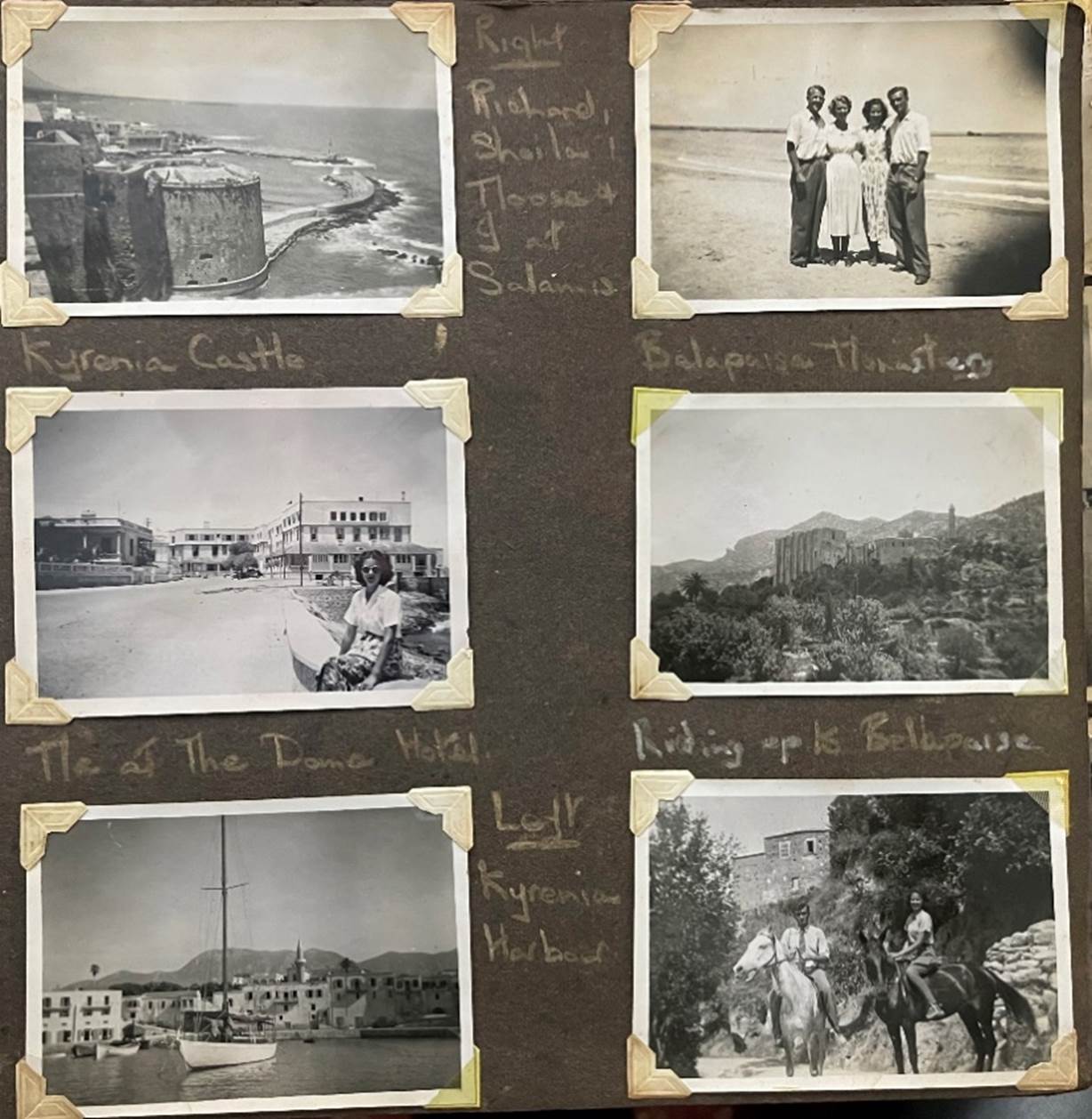

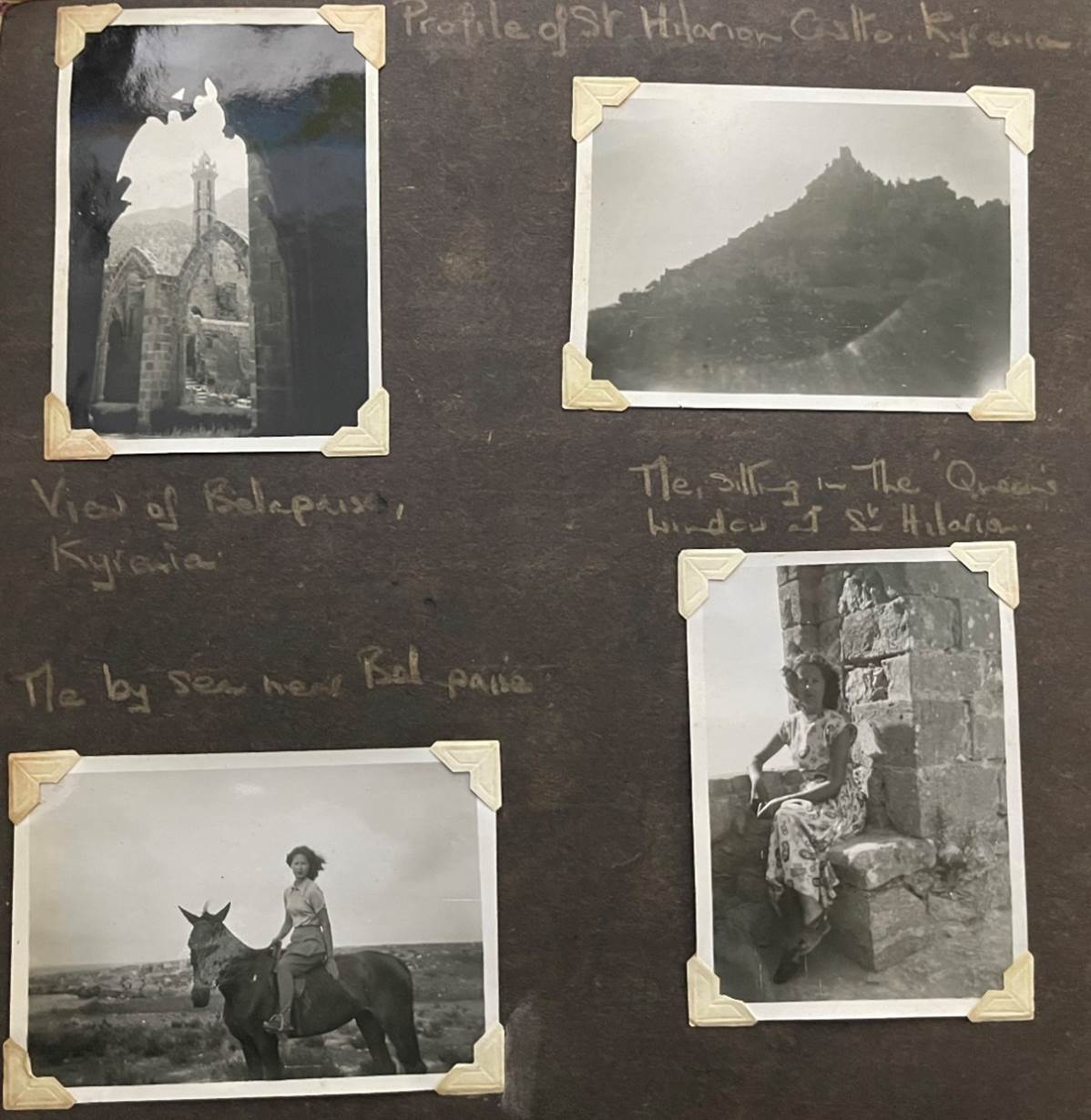

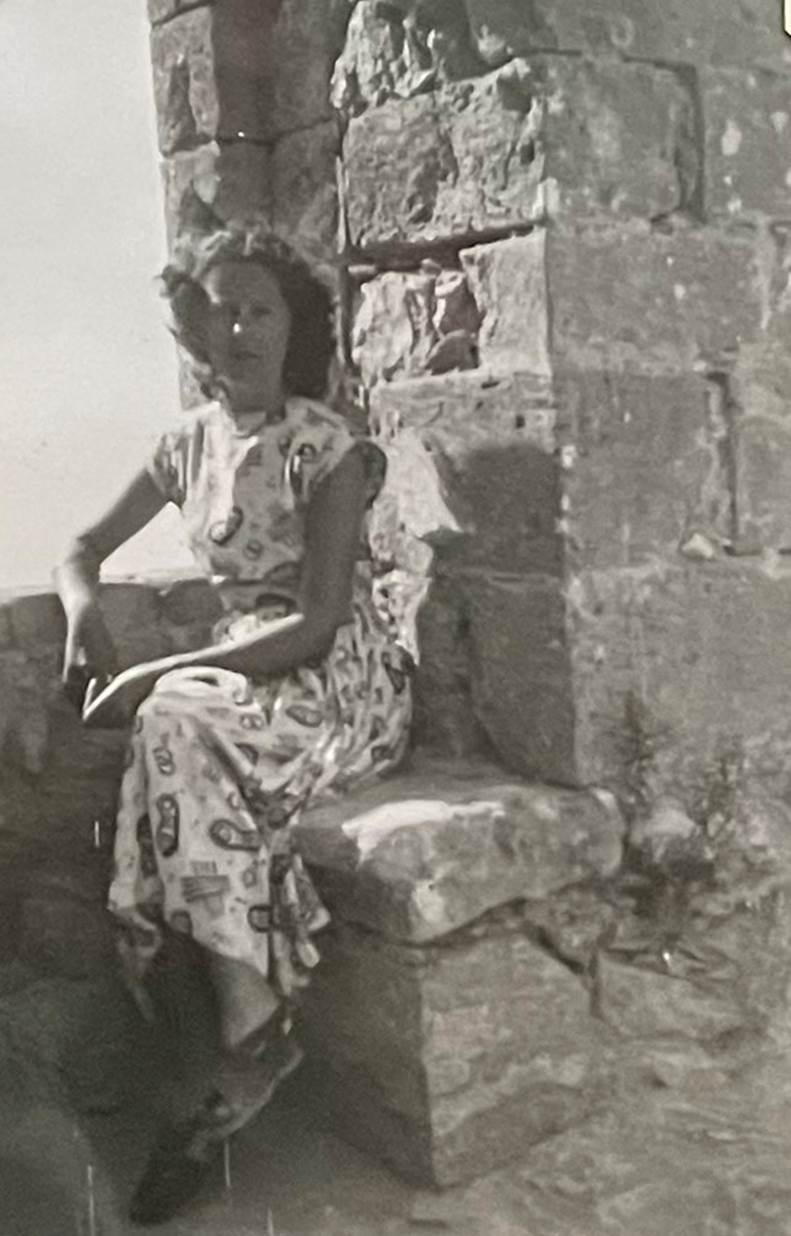

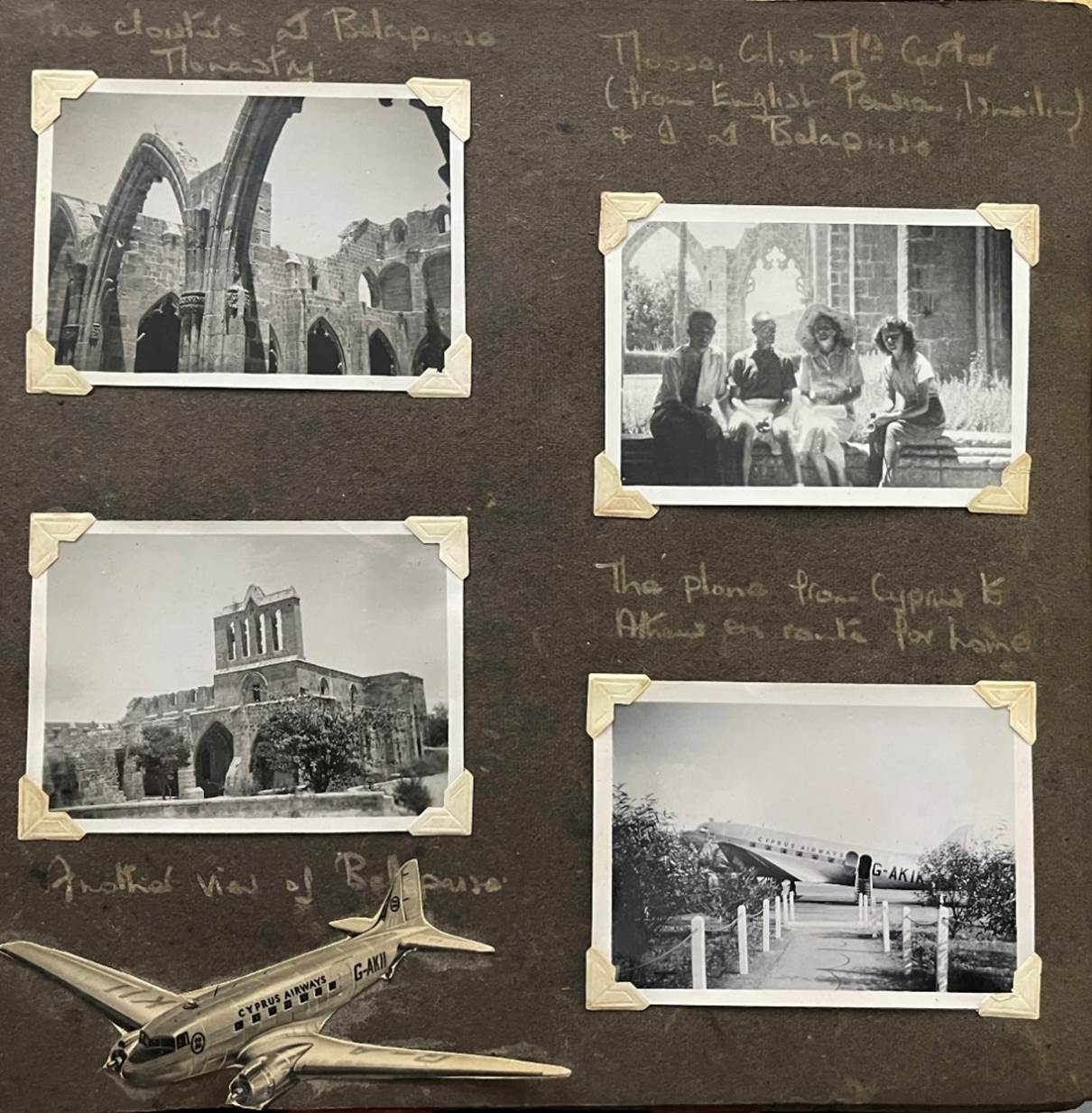

We visited St Hilarion, the craggy ruined castle set up on a rocky pinnacle, which is supposed to have inspired the story of Snow White. After walking up hundreds of steps, the view is breathtaking and I remember sitting thankfully down in the famous Queen’s window right at the top of the castle. We drove to Salamis where excavations were being carried out. Since that time a good many interesting discoveries have been made. Salamis is steeped in legend, and Aphrodite is supposed to have risen from the waves near there. The beach is lovely and when we were there was quite deserted and scorchingly hot. Cyprus abounds in small secluded beaches with very few people about, wonderful after bathing on the English coast.

The train from Famagusta to Nicosia was quite unlike any train I had ridden before! Very small, with a tiny engine, all rather like a toy. I believe we were the only passengers and at every halt, the engine driver would enter into a long conversation either with us or the people standing on the platform. Nicosia was extremely hot, with narrow crowded streets and potpourri of peoples - Greeks, Turks, Egyptians, Maltese and others. I remember visiting the Cathedral of Saint Sophia with its high twin towers, now a mosque. While we were in Nicosia we stayed at the Ledra Palace Hotel, which was then newly built, and the in the evening, as in Ismailia, there was dancing outside. We went to a nightclub which seemed luxurious after dark, but rather tawdry, seen again in the light of the day.

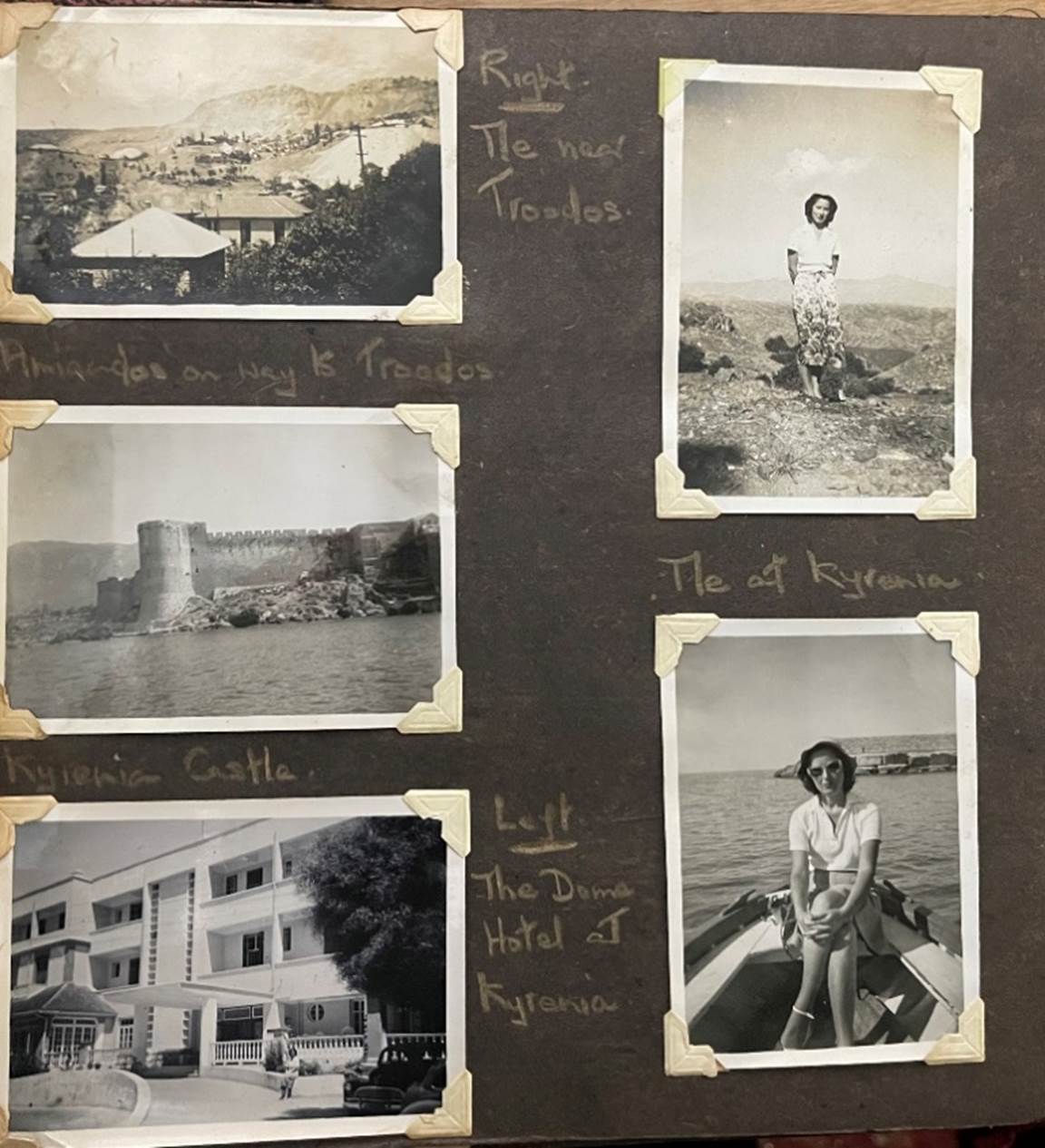

We drove to the Troodos in the mountains for the day, up a steep winding road, often with such sharp turns that it was impossible to get round at all without backing and manoeuvring, and once we nearly went over the edge. The car, which we had hired kept spluttering and Martin sucked out gallons of petrol before we finally reached the top! We drove past Amiandos on the way, a mining village, which was later to be the scene of a good many terrorist ambushes. All I can remember of Troodos itself is pine trees, views and little lizards (which abound everywhere on the island) darting about. Apart from the old summer camp, there is very little else there, it is so high that on the hottest day it is beautifully cool up there. In the winter you can ski in the mountains of Troodos and then come down to Kyrenia where it is warm enough to bathe.

Driving through the countryside we were struck by the primitive methods of farming, with no sign of any modern equipment, tools. The men in the country districts nearly all wore the traditional black, baggy pantaloons.

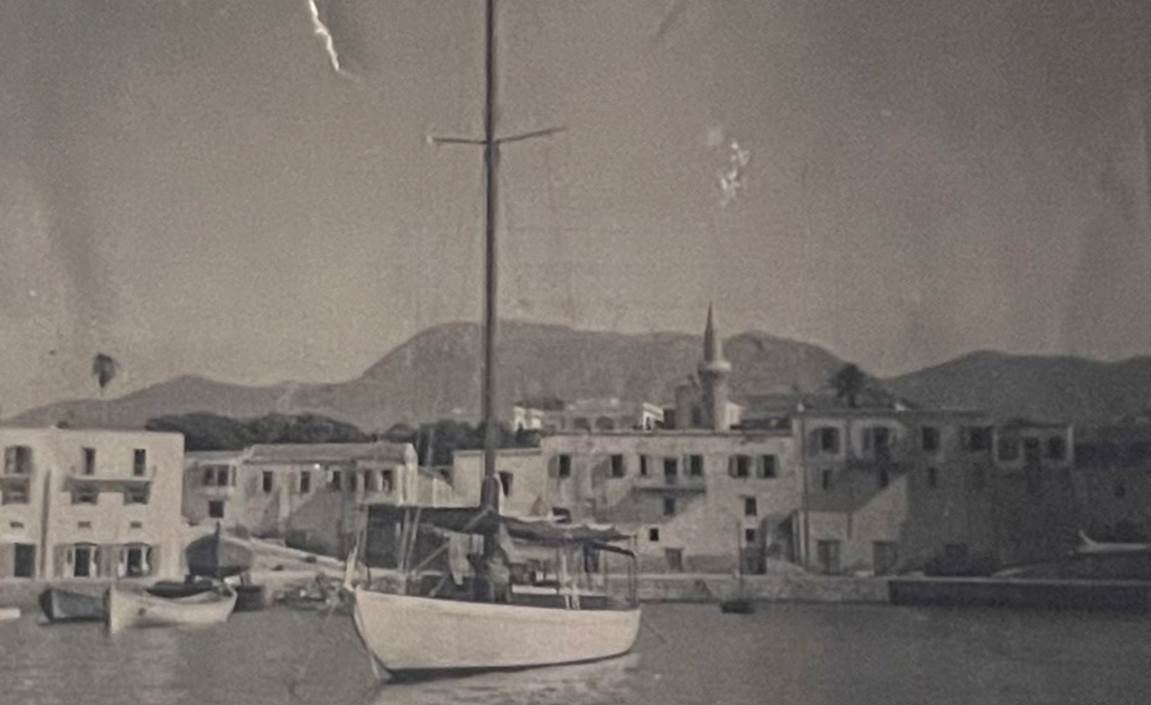

Moving to Kyrenia, we were surprised at the number of retired English people there seemed to be about. It is a most lovely town and it is easy to understand why they should want to settle their. The harbour is quite beautiful with the castle on one side and a skyline of mosques and pastel houses on the other, and of course, colourful sailing boats bobbing jauntily on the blue water. We stayed at the Dome, another new and enormous hotel overlooking the sea.

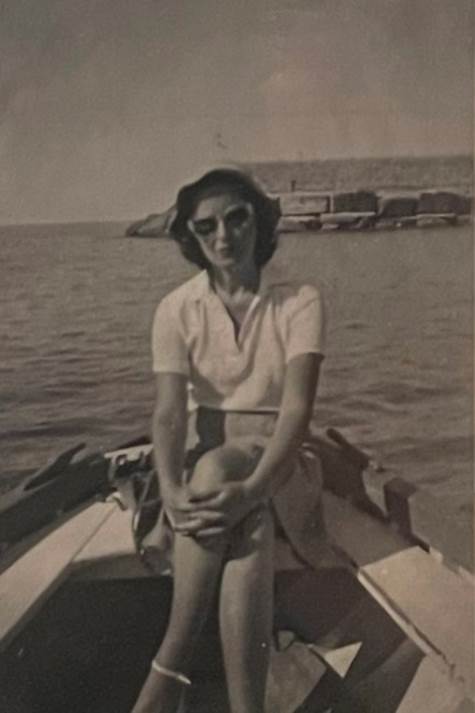

Anne Buckingham in Kyrenia The inner harbour at Kyrenia

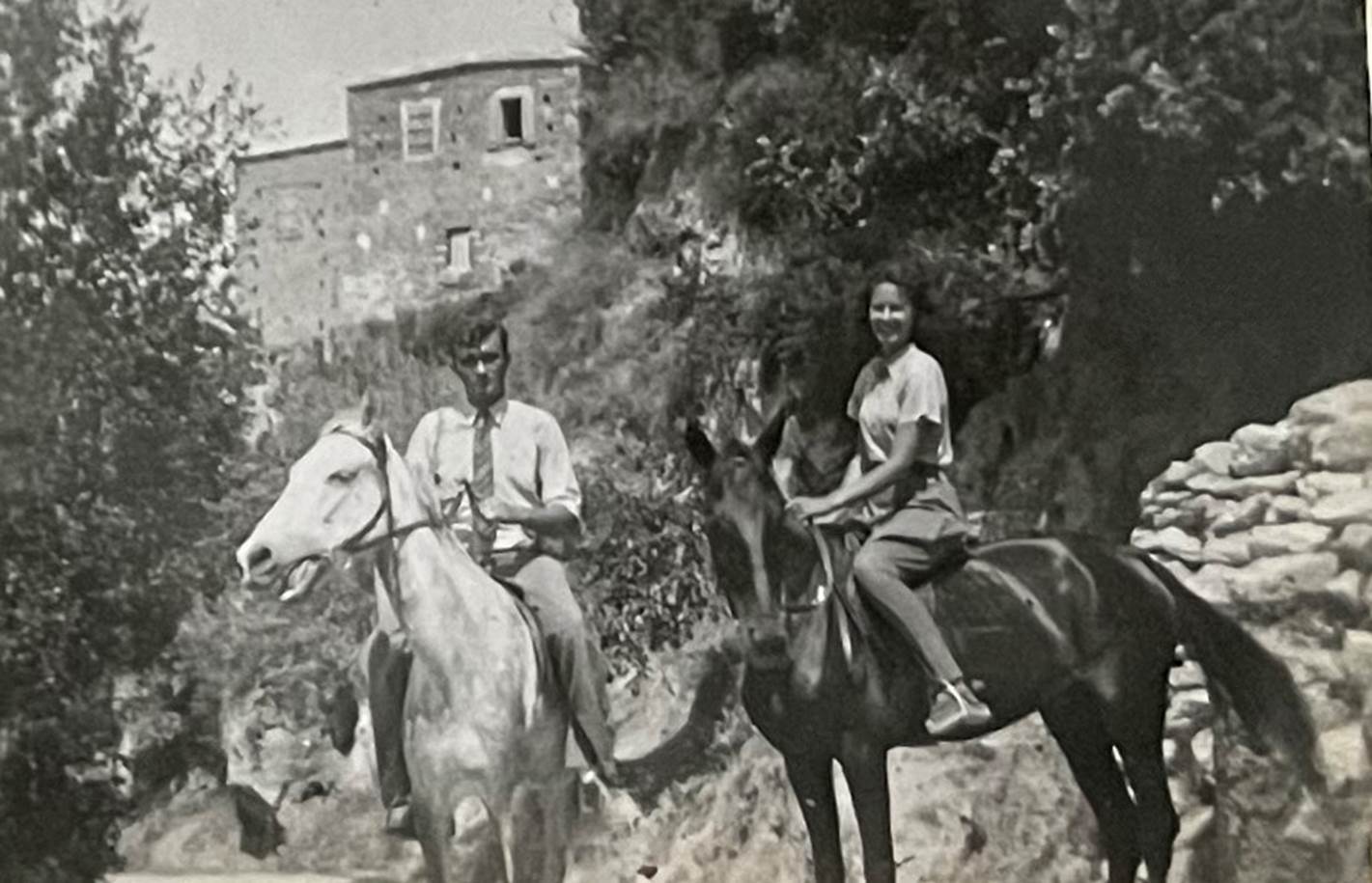

One day we were driven a couple of miles out to Mrs Newman’s farm to have tea. This is run just like an English farm, but with banana trees growing in the garden, the illusion is somewhat dispelled. We borrowed horses from the local stables and rode up to Bellapaix. Martin very nobly rode the horse which had bitten me the day before. It continued to look very disgruntled and looked as if it were biding its time before taking another bite. We rode up winding paths through vineyards, and everything was quiet except for the chirping of crickets and the sound of the horses hooves. Occasionally a lizard dusted out from behind a stone, and then, at the top of the hill, was the monastery, a most interesting ruin with Gothic archways and its refractory, all surprisingly well preserved.

Bellapaix

My memories of Cyprus are very happy ones and I should love to go there again some day. Of the countries I have visited, the people of Cyprus, Switzerland, Denmark and Malaya have all been equally welcoming in the eyes of a visitor.

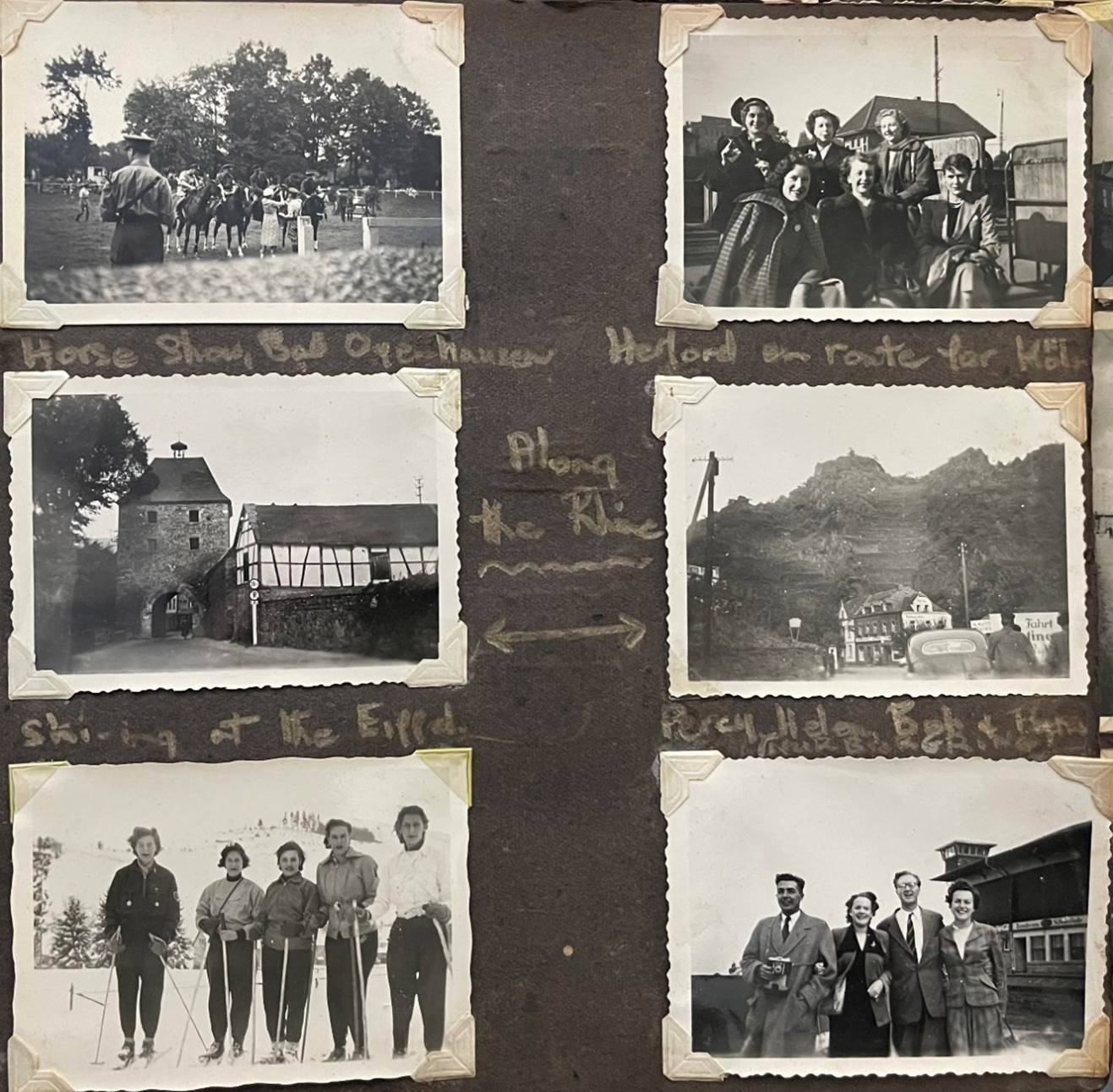

VI – Germany (1951 and 1955)

Germany - I sometimes feel that I know it better than England, having spent three years there at that time and many more years later, and travelled all over the country in every direction.

On my first visit I was working, and was seconded to Bad Salzuflen, a most attractive spa which has beautiful gardens and old beamed houses and shops. There are several spas in the area, and people from all over Germany go to them to take the waters. Part of the cure in Salzuflen seems to consist of sitting on platforms half way up tall rows of hedges and sniffing, as the water drips continually down through the foliage! Most of the spas came into being about the end of the 18th century, and the Kurhaus is the centre of spa life; Bad Oyenhausen is bigger and Pyrmont more elegant, but Salzuflen has great charm. Once a year the enchanting candle fest takes place there, and the view across the gardens from the slope of the Kurhaus is breathtaking. As soon as it is dark, thousands of tiny lights twinkle high and low. The gardeners and their families start to light the night lights hours before so that all will be ready when darkness falls. They shine out among the flowers, float on the slow stream, winding its way through the gardens and bestow a dreamlike air on the familiar scene, as they flicker bravely in the breeze.

When I first arrived, eight of us were living in a rambling old house which had just been condemned. Six of the girls chose to move to a new mess on the other side of the gardens, but two of us stayed where we were. The office was moving to Herford, 5 miles away quite soon and we thought that it would be far better to wait and move into smaller houses over there and save travelling to and fro everyday. And so for another six weeks we lived very comfortably in this rambling old house, rather eerie with so many empty rooms, and vaguely expected that at any moment it might crumble about our ears. One evening we went to the Kurhaus theatre to see “The Green Table”, an extraordinary ballet performed by the famous Ballet Joose. The subject, an odd one for dancing, was a group of politicians with the future in their hands, and was interesting because it was so unexpected and different. In German ballet there is very little toe dancing and a good deal of mime; it is unethereal, but effective and is in keeping with the German character.

We drove to Lemgo several times to the club and near there we explored a strange and sinister wooden house. Quite small and very dark, every inch inside seemed to be carved. It was built by an architect who had spent some years in India, he originally made the furniture to receive his future bride. She refused to marry him on the eve of the wedding, and he never recovered from the shock. For the rest of his life he continued to carve strange designs in the wood, and became a complete recluse. There are ornate models of Indian temples and a staircase covered in the carvings, and the house has a suffocating and sad chill, and I for one was thankful to go out into the sun and air. We visited a schloss nearby where the owner has a large collection of old musical instruments, and they are sometimes played there at concerts. From there, on to Hameln of Pied Piper fame. On the banks of the Weser, the town has many old gabled houses and cobbled streets. There is the pied Pipers house to be seen and a 17th century house in Osterstrasse, which is now a museum. Every Sunday morning in the summer, a modern Pied Piper still plays his pipes in the streets, followed by a throng of shouting and dancing children.

The Germans seemed to be a very odd mixture. On the surface the North Germans seemed austere, though, in the Rhineland they are gayer and more carefree. Yet in spite of this feeling of austerity, they have in the past produced an amazing amount of genius in poetry, music, painting and philosophy. To think of only a few names, Bach, Beethoven, Handel, Mozart, Strauss, Schumann, Schubert, Brahms, Wagner, Holbein, Durer, Goethe, Schiller, Kant, Marx, Nietzsche and many more. As a race they have an artistic flair which shows itself in many ways. At Christmas this is particularly noticeable, when the shops are full of the most original toys and decorations. Food is made to look delectable and the chocolates and sweets often seemed far too perfect to eat. The houses have gay reeds swathed in ribbon hanging over their doors, and inside there is often an advent ring with four candles, one to blow out for each week in Advent. On All Souls night, tiny candles flicker from the graves, and a few weeks later, St. Nicholas appears to herald Christmas. Yet in contrast, many of the people looked unbelievably drab at that timey, and are dressed in the most sobre, square shouldered and belted way, the women with hats jammed hard on their heads and secured firmly with elastic onto the chin stop. Everywhere one is struck by such contrasts, by beauty and austerity intermixed. Nothing could be more uninspired than the German Hausfrau, with her passion for cleanliness, and beating her rugs out in the snow.

As a nation, Germany has amazing recuperative powers, and when I was first there five years after the war ended, it was amazing to see how many new buildings had risen from the rubble. Often the building would go on right through the night by the light of lamps and as soon as the roof was on, a wreath would be hung on high for good luck. In spite of the speed of rebuilding, I can still remember very vividly the unbelievable devastation of the Ruhr, Berlin and Hamburg. Brunswick two was largely a ruin, and I still see the look of hatred on the face of a middle-aged German as he realised that we were English. In Berlin, though, the people were surprisingly friendly, preferring us to their Russian neighbours.

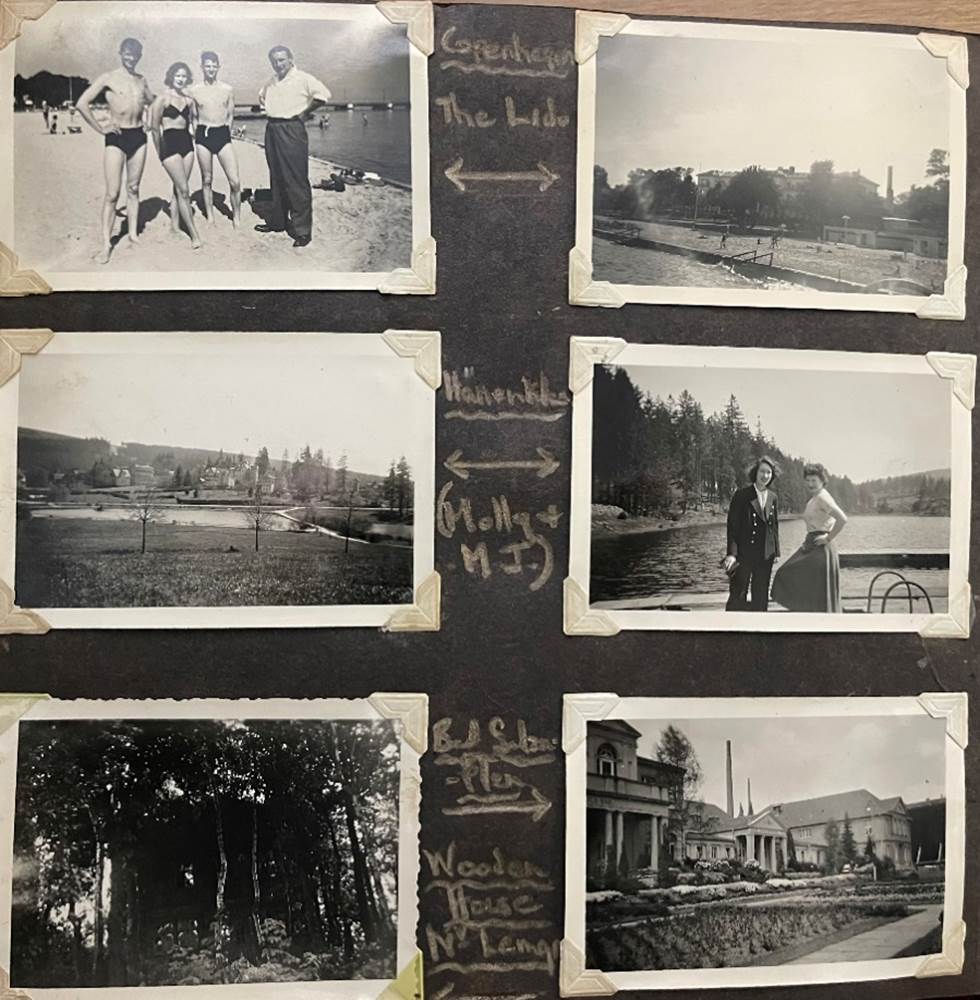

One long weekend, three of us went down to the Harz mountains by train, and stayed at the small officers leave centre at Hahenklee. This closed down soon after, but was considered to be much nicer than the larger one at Bad Harpsburg nearby. The Harz Mountains are beautiful, with thick pine covered slopes and green valleys; Hahenklee itself was so near the Russian border, that apparently in the winter it was quite easy to ski across by mistake and there were maps and warnings in the bedrooms, in an endeavour to avoid losing guests! We had arrived by train at Goslar, a lovely and ancient town. All round the market place were luxurious old houses built for prosperous merchants, and one particularly beautiful one with wood carvings on its facade, dates back to the early 16th century. The shops were filled with local wood carvings, and every kind of souvenir, and in Bad Harzburg, there were witches of every shape and size - wizards and fairies have haunted the Harz Mountains from time immemorial!

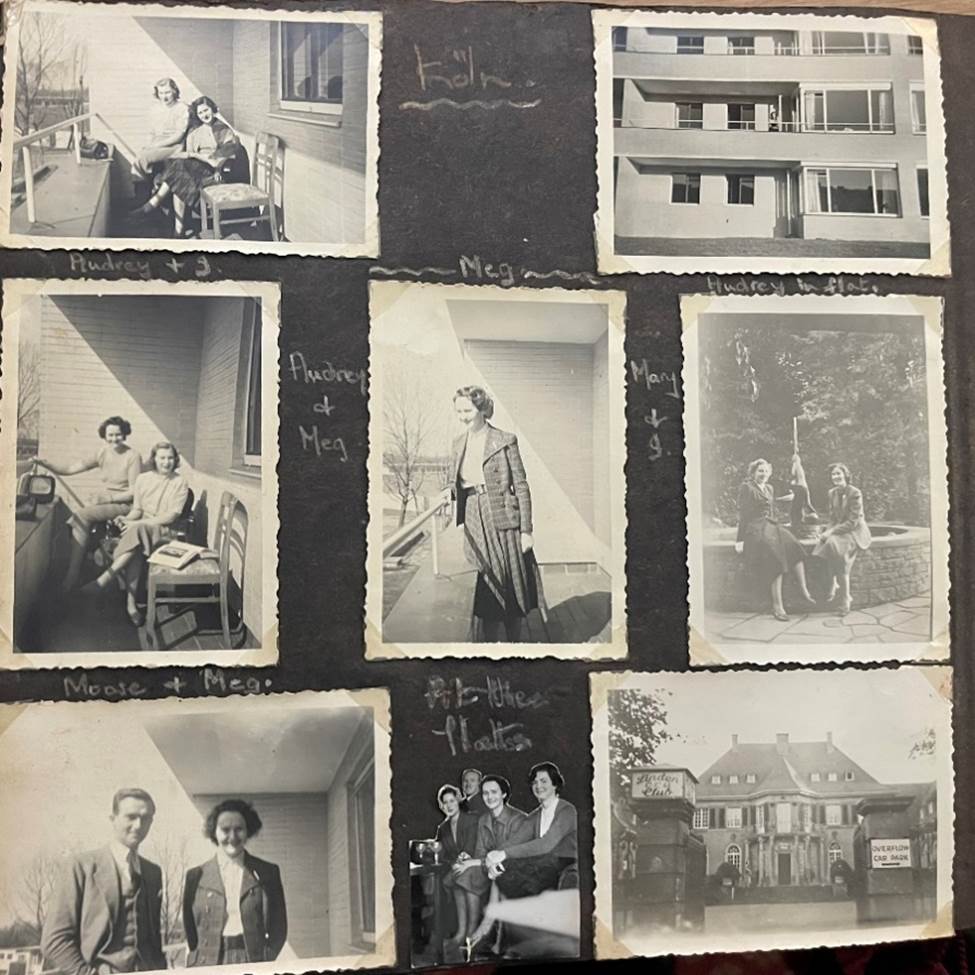

After living for a few months in Herford, we all moved en masse to Cologne and into a new and enormous block of flats, immediately christened “The Queen Mary”, as it had large funnels on the flat roof. There were three of us living in each flat, and three maids between two flats. Our cook was a doctor's daughter who had lived in England and had a domestic science degree. We were very fortunate in having her. The flats themselves were well equipped and centrally heated, a boon in the icy German winters. Cologne was generally being rebuilt, though there was still a great deal of damage to be seen and we were told that many families were still living in deep tunnels far below the ground, the smaller children were unable to get up to the surface for weeks at a time.

It is quite amazing how Cologne Cathedral, that superb masterpiece, still stood after the war while everything round it was destroyed. This was one of the first Gothic churches to be built in Germany, and contains among other treasures the shrine containing the relics of the three wise men, which was brought from Rome in the 12th century. Cologne contains many interesting holy relics, and the crucifix in Saint Gereon’s church is the oldest statue of Christ on the cross in existence. The people of Cologne are famous for their exuberant sense of fun and at carnival time, the town goes wild. On Shrove Tuesday, there is a gay procession through the streets and everything staid and serious is made fun of. The streets are turned into fun fairs and anything may happen.

Asked to sum up my gastronomic impressions of Germany in a few words, I think I would just say - black bread, pumpernickel, beer, caviar, enormous fruit flans covered in thick cream, bockwurst and bratwurst (boiled or fried sausage, eaten on a freezing station platform, they are delicious), vast chateaubriand which disappear in record time when consumed by enormous German gourmands, and lastly the delicious continental coffee which we in England seemed quite unable to produce. The German gasthauses are generally very well run with excellent service, which I suppose one might cynically put down to unemployment in the country, and anything you care to order from the enormous menu will be served, however late it is. I cannot help comparing this with English restaurant service - on a motor tour near the Welsh border we were told shortly that the meal was off at seven thirty pm and some continental visitors were turned away at the same time. Although there are no licencing hours, there seems to be little drunkenness. The locals become quite jolly on their frothing beer, but not unpleasantly so.

We thought nothing of travelling 100 miles or more to a dance at weekends, and I went to Bad Oyenhausen several times to visit my cousin and have a foretaste of army life at the headquarters there. I remember on one occasion a party of us were invited to a cocktail party at the naval base at Krefeld, and afterwards went on to the local Golf Club dance. We had not had much opportunity to meet the German people socially, and so this was an unusual occasion. Most of the men were rich, Ruhr industrialists and there was a great atmosphere of richness, elegance and gold. We went to several race meetings at Hanover and Dortmund and generally travelled about a great deal at every opportunity.

Dusseldorf is to me the most delightful town in Germany, and is an oasis of pleasure in an industrial area. The Konigsallee, broad and straight, is full of the most entrancing shops, and the nightlife of Dusseldorf is very gay. Many old customs are still retained there, and on Saint Martin's Day, the Saint rides through the streets on a White Horse, accompanied by a crowd carrying flaming torches. An unforgettable memory of Gigli singing at the Opera House, still with a glorious voice, he sang encore after encore to resounding cheers, and I feel very privileged to have heard him sing in person before he died. At Cologne, the Opera House was bombed and we went to operas at the university, though now a new Opera House has been built.

We sometimes went to the Mohne See to sail on the calm lake, and stayed at the club there and in that peaceful scene it was hard to visualise that night of terror a few years before when the dam was blown up and the water gushed out with such force that it had reached the streets of Essen several miles away. The skiing at Winterberg was fair, and there was a large leave centre there. I remember spending one Christmas there when there was no snow, and everyday we waited and gazed longingly at the slopes, but they remained green to the last. When there was snow, it was generally very thick and heaped in great mountains on the side of the road by the snow ploughs. There was a high ski jump there and it was amazing to watch quite small boys take off from the top and land unconcerned in the valley far below. We went to Soest fairly near there and an hours run from Dortmund, and remember that everything looked green. Many of the buildings were built with stone containing glauconite from the hills south of the town, which turns green with the years, and I was reminded vaguely of the green rooves of my lovely Copenhagen seen a short time before.

Driving along the bumpy roads, you would often see an enormous stork's nest perched high on a rooftop, and this was a very lucky sight. Apart from the autobahns, most of the German roads were very bad with deep ruts on either side, There was rarely room for two cars to pass, without one being forced into the ditch and much nerve and determination was needed to stay in the middle of the road! Occasionally in the winter, a Volkswagen bus would set off with several of us packed in, to take us to ski on the Belgian border. We stayed at a village in and skied down the gentle slopes nearby. Several of the old houses in the village still bore shell scars from the 1914 to 1918 War.

At Easter a couple of us set off by train, our first stop being Wiesbaden where we would spend a few hours. A prosperous and well laid out spar, I remember its long straight roads, and flags of many nations fluttering in the breeze. Before the First World War, Wiesbaden was a millionaire's resort and still boasts many palatial houses. Numerous festivals take place there which helped to attract tourists, and the town is one of the best wine growing areas in the country.

Our next stop was Frankfurt am Main, where we intended to stay. Frankfurt, home of Goethe and near the birthplace of the fairytale Grimms, is an important economic and industrial centre, where remarkable progress was made very quickly after the wartime devastation. When Mary and I arrived, we found that most of the hotels were full and were given the address of a German family who had a room to let. This was very comfortable, right in the middle of the town, and gave us an interesting insight into the German family life. We were told that a nearby park was well worth a visit, but we had hardly arrived there when it started to pour with rain. The only place we could see to shelter was what we discovered to be the American Service Club in the grounds. The rain fell in a steady downpour and we asked if we could get something to eat at the canteen there, but were told by a Sergeant that we could only pay in dollars. We were just going to the door, when he suddenly appeared with an enormous smack for each of us. He was obviously simply being kind, and so we accepted his help gratefully as he preceded to advise us about what we could see in the short time we were in Frankfurt. After a long discussion, he insisted on taking us on a quick tour of the town that evening, and as there was only one of him and two of us, we felt that it would be alright to go. I'm very glad we did. We spent a most amusing evening touring the town, and looked in on five night clubs, which we could not possibly have done on our own. We finally arrived home at two am and said goodbye, with the promise that if he come to Cologne, we would show him round in return. We left Frankfurt and next morning went by train to Freiburg, almost on the Swiss frontier.

The sun was shining and it was as hot as summer when we arrived. Freiburg is an enchanting town. Its famous Gothic cathedral, completed in the 14th century, is a superb architectural achievement and round its thick walls the old houses are grouped in perfect harmony. Another memory of Freiburg is of the university with literally hundreds of bicycles propped up outside. A girl who was working with me in Germany had been to the university there and always said it had been the happiest and jolliest time of her life. We took a trip up a nearby mountain, and poor Mary was seized with a violent attack of hayfever and so she missed most of the views on the way up. The cable car was a somewhat alarming affair which swayed a good deal as we were suspended in mid air, but as we climbed higher and higher, the view of the mountains and distant valleys was wonderful. At the top, we were rewarded with a panorama of Swiss Alps before us. Suddenly the skis darkened and a violent storm broke with thunder and lightning flashing all around us. We sat in the tiny restaurant up there for a long time, drinking hot chocolate, and at last the storm abated and it was deemed safe to take the cable car down the mountain again, and then the long train journey back to Cologne after seeing three interesting towns in four days.

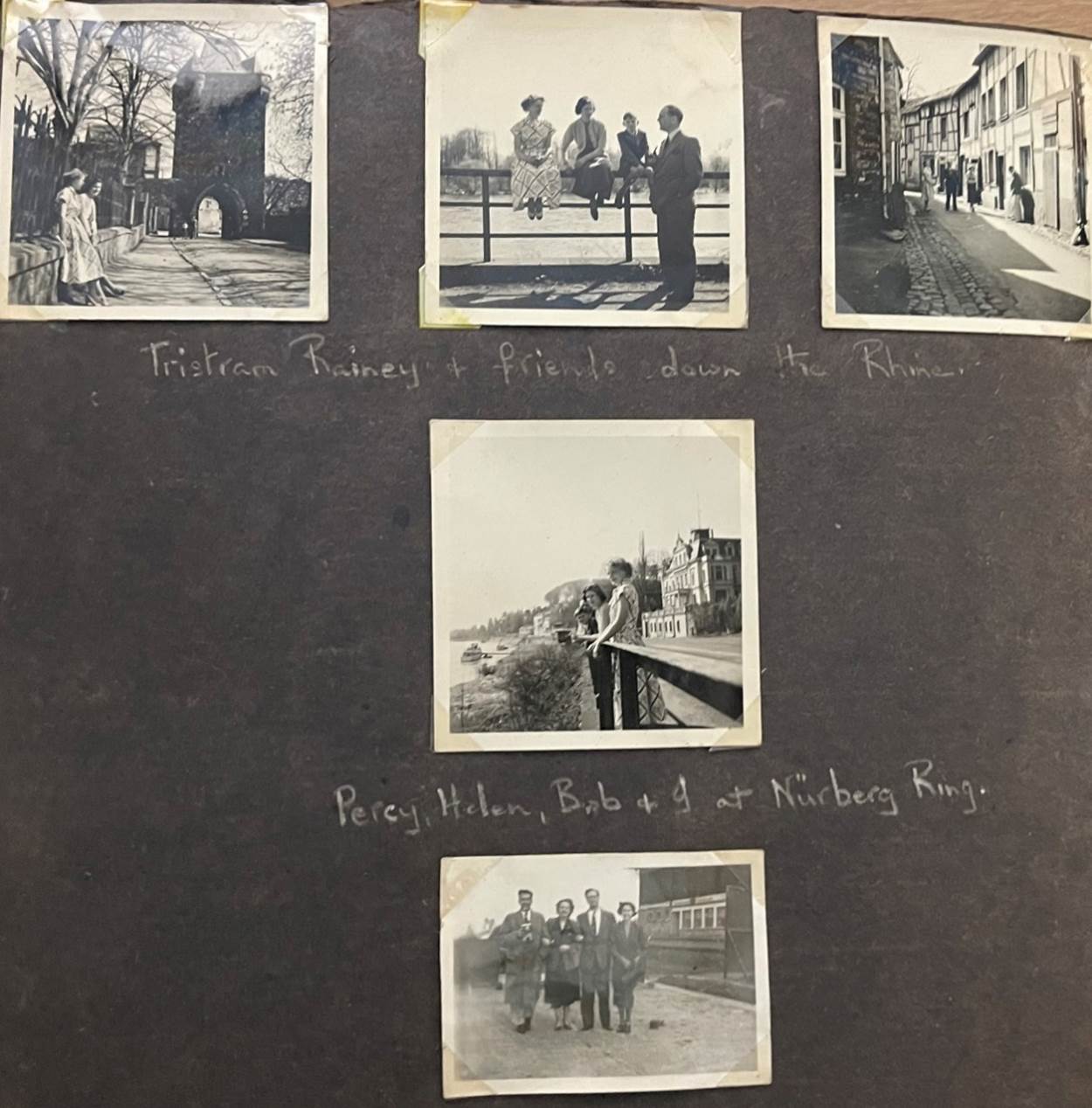

VII - More about Germany (1951 and 1955)

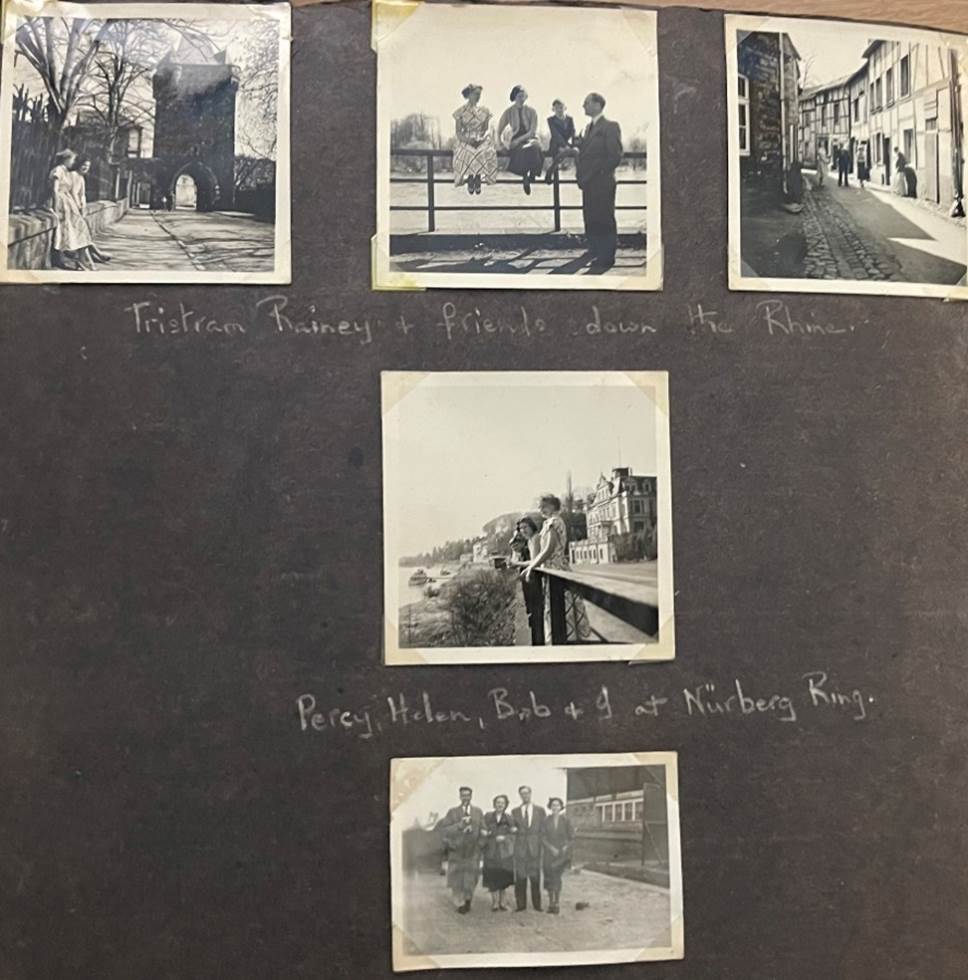

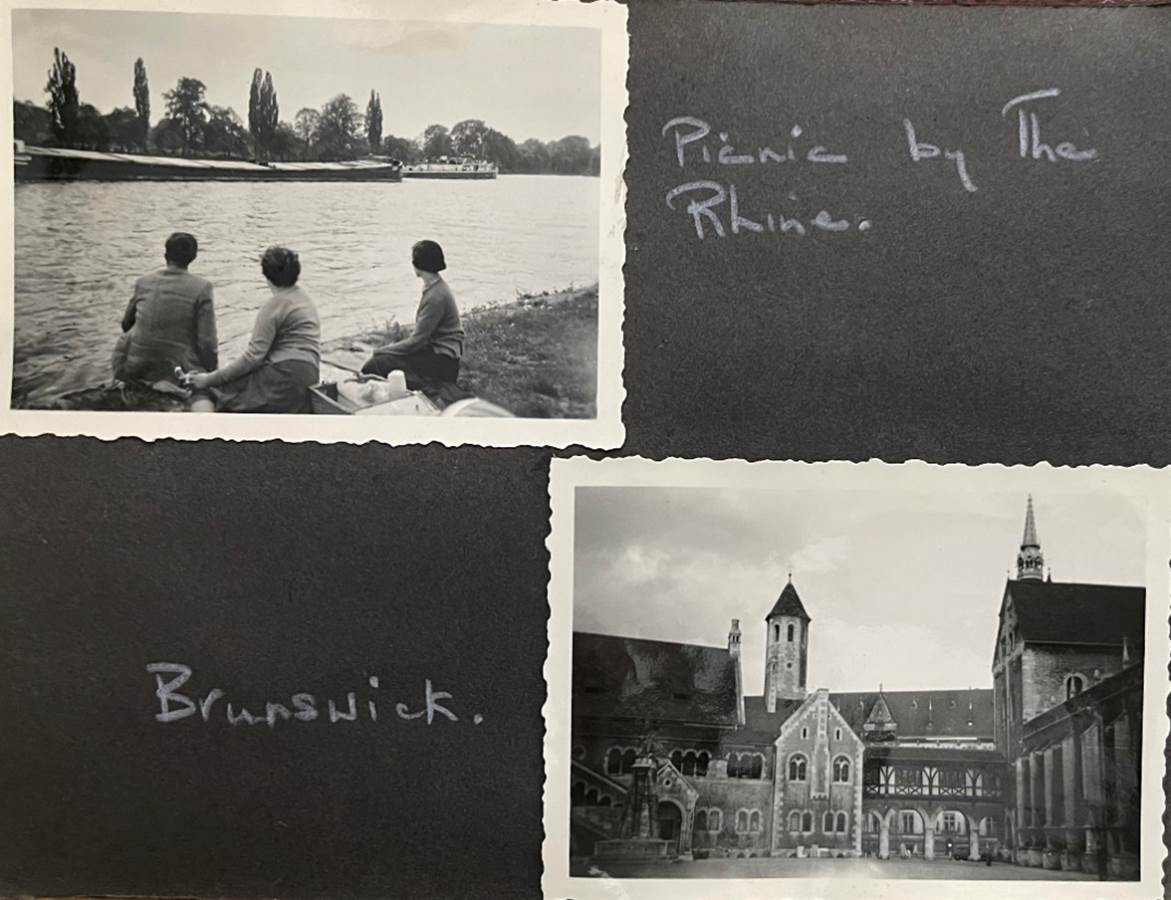

Often at weekends we would drive through the Rhineland, or perhaps take a short trip on one of the jaunty little flag bedecked steamers to the accompaniment of an accordion and singing. Canoeing is a very popular pastime on the Rhine and a good deal of skill is needed to balance the tiny shallow boats, as larger craft sweep past them. I particularly remember a year after the trip to Freiburg, Martin came down to Cologne for Easter. He had just arrived in Germany, and for his first Rhineland trip we went by boat to the Drachenfels, and ate a delicious lunch in a restaurant suspended high on the side of a rocky crag; with a sheer drop to the blue Rhine far below us. We gazed down on a unique view as the river wound its way through a landscape of vineyards, ancient castles and rare scenery, and were very happy.

At the time of the Weinfest, the Rhineland is particularly gay, and after a long and tiring drive, it is wonderful to sit outside a little guest house in the sun, sipping wine in its own setting. The Moselle vintages are lighter and slightly sharper than Rhine wines and at the time of the Weinfest all you have to do to decide which is your favourite, is to buy one glass of wine. From then on, you can go on sampling different kinds until your head swims, in the midst of much hilarity.

The Rhine and Moselle meet at Koblenz, with the old and solid fortress of Ehrenbreitstein still standing guard over the peaceful scene. South of Koblenz is the famous Lorelei, an enormous rock hanging over a particularly fast flowing and a dangerous stretch of river. The story goes that the maiden of Bacharach was accused of witchcraft and in despair threw herself into the Rhine. Ever since, she has been luring boats towards the rocks and the seamen to their deaths. Two particularly attractive little towns by the Rhine are Rudesheim and Assmannshausen, with old timbered houses and narrow cobbled streets. Assmannshausen is opposite Bingen, and near there in the middle of the river is the mice tower. Legend has it that Hatto, a wicked and greedy Bishop retired to his isolated tower during a famine, well stocked up with provisions. He had for some time been hoarding stocks of flour and other essentials, but instead of sharing his good fortune with his starving flock, he kept it all for himself. Somehow, the mice found their way across the river and devoured him.

During one trip to the Moselle and wooded Eiffel area, we drove round the famous motor racing circuit at Nurburgring, but we manoeuvred the winding course at about 30 miles an hour and there were no screeching brakes to disturb the country silence.

We often caught the train from Cologne to Bonn, the Federal Capital. The Bundeshaus, (Parliament House), Presidency and Chancellery are near the Schaumberg Palace in Koblenzerstrasse, but in spite of this impressive array of buildings, Bonn to me does not seem like a capital city. We walked around the house where Beethoven was born in Bonngasse, and it is easy to understand how, living in the Rhineland which he loved so well, he could capture the spirit of the romantic and mysterious Rhine in his music. Today, so long after his death, his spirit still lives in the town.

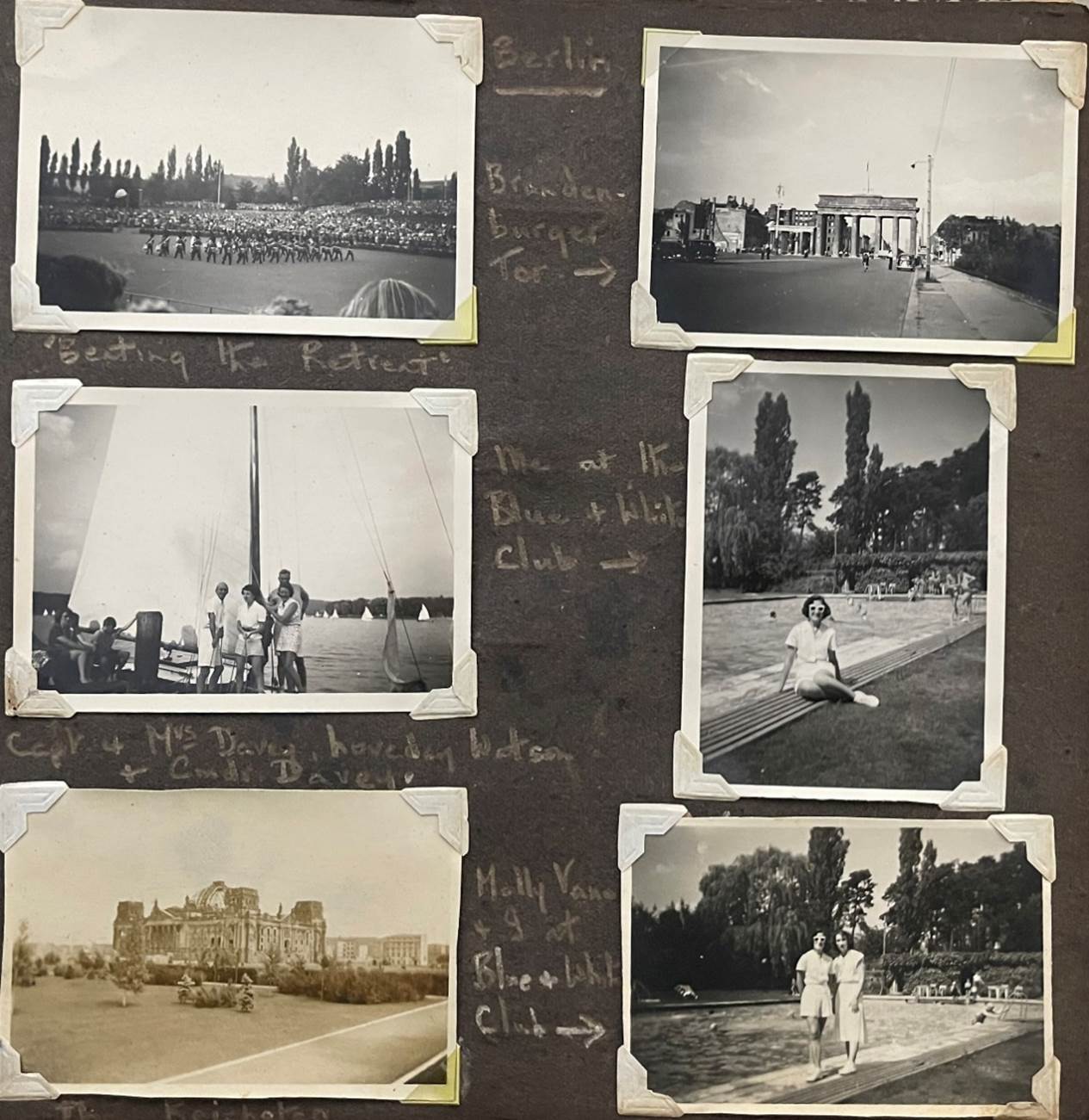

One weekend, another girl and myself set off by train to Berlin. We travelled through the night with tightly drawn blinds, and were not supposed to look out at all as we passed through the Russian zone. There was a good deal of noise and shouting on some of the station platforms and curiosity getting the better of us, we peered out to see crowds of young people en route for Berlin and a youth rally in the eastern sector. In 1952, Berlin, never architecturally beautiful was a vast ruin. The devastation was unbelievable wherever you looked. We stayed at the Savoy Hotel, which amazingly enough appeared to be intact, and quickly set off on a tour of exploration. We walked down the Kurfurstendamm, Berlin's main shopping street, and saw that most of the shops were temporarily one story affairs surprisingly filled with a great variety of good things. Everywhere we went where, we were struck by the friendliness of the people, and could not help admiring their cheerfulness in such surroundings. We watched a beating of the retreat by British soldiers and were surprised at the interest of the people watching, though of course a military display of any kind all is enthralling.

We drove down the Unter den Linden towards Brandenburger Tor and stopped to look at the Russian War Memorial just inside the western sector, which was guarded by two very undersized and scruffy Russian soldiers, and nearby saw the sinister ruined Reichstag. Behind the Brandenburger Tor, we could see a long road with drab buildings in the Russian sector. And from a few yards away, crowds of youths, obviously up for the rally, gazed curiously towards the West. They were so near, and yet were living in another world of colourless regimentation, and monotonous communist propaganda. Suddenly the cheerfulness of the West Germans was easy to understand, for freedom is a vital constituent of life, even when your world lies ruined about your feet.

A friend in Berlin had just become engaged to a naval commander, and she invited us to go sailing, only a few miles from the centre of Berlin. There were six of us, and after a delicious picnic lunch and most enjoyable day, we had to be towed back to the clubhouse as the wind had completely dropped. This was a very undignified return for the Navy! Fortunately we did not drift too near the Russian side of the lake, though at one point it looked quite close. That night we had to catch the train and unfortunately missed the intriguing nightlife that Berlin has to offer. There is apparently one nightclub there where ponies can be ridden around the dance floor, and another where all the tables are linked by telephone. There are various rather dubious ones where the bartenders are dressed as women.

Germany was a wonderful centre for visits to the neighbouring countries, and with plenty of leave it was possible to arrange many interesting trips during my tour there.

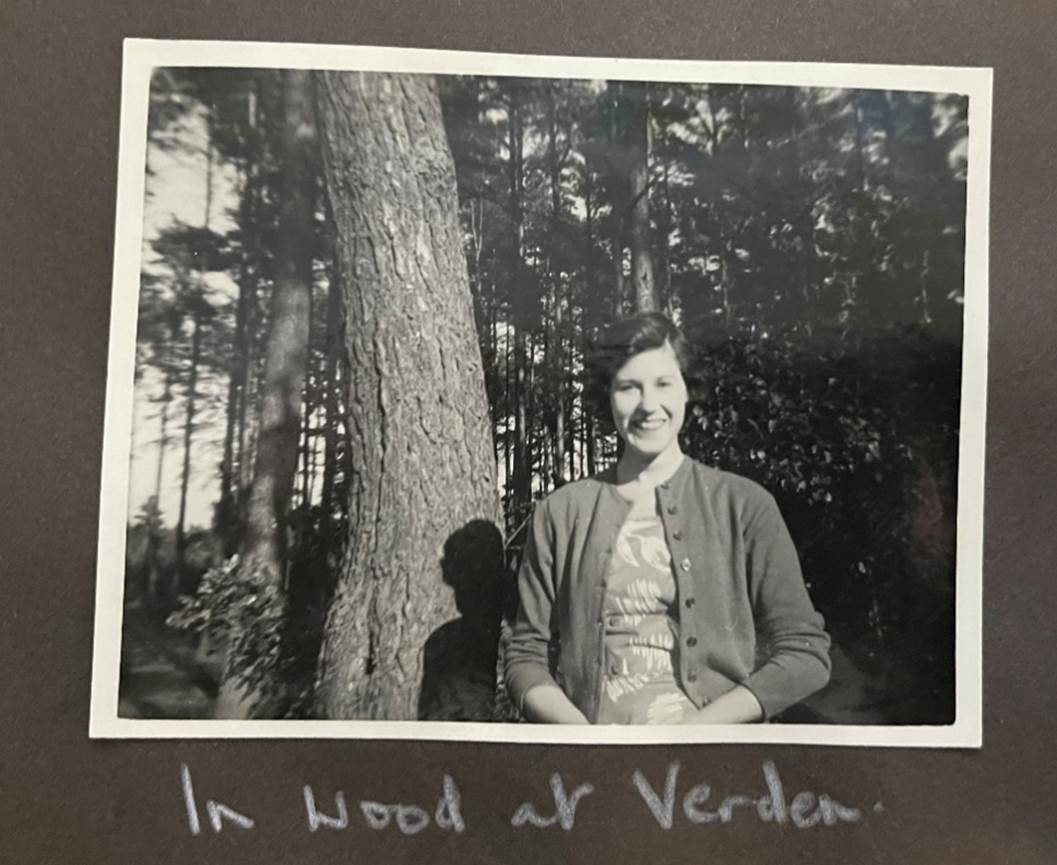

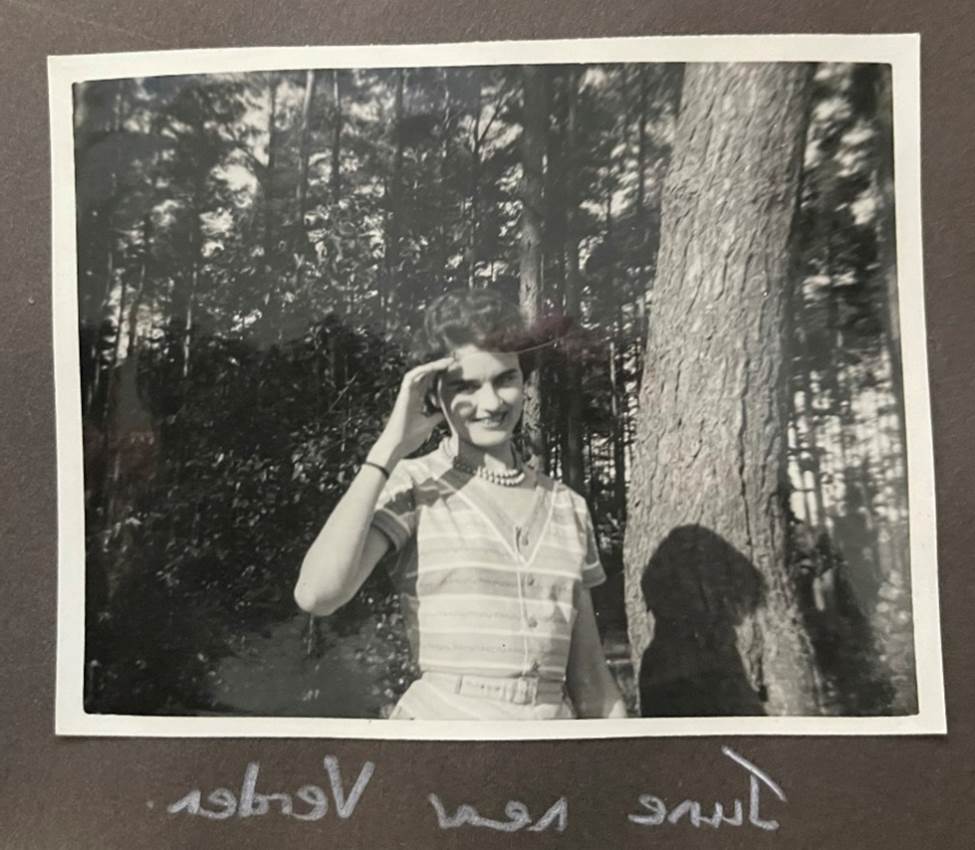

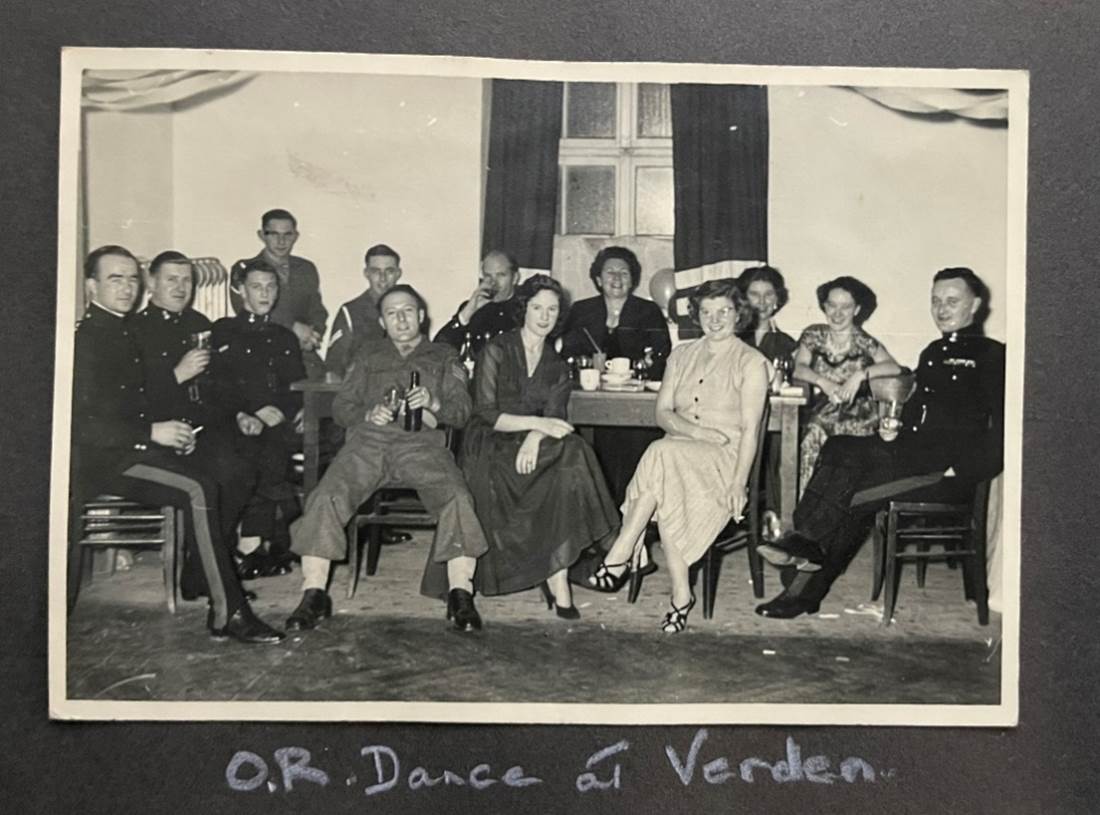

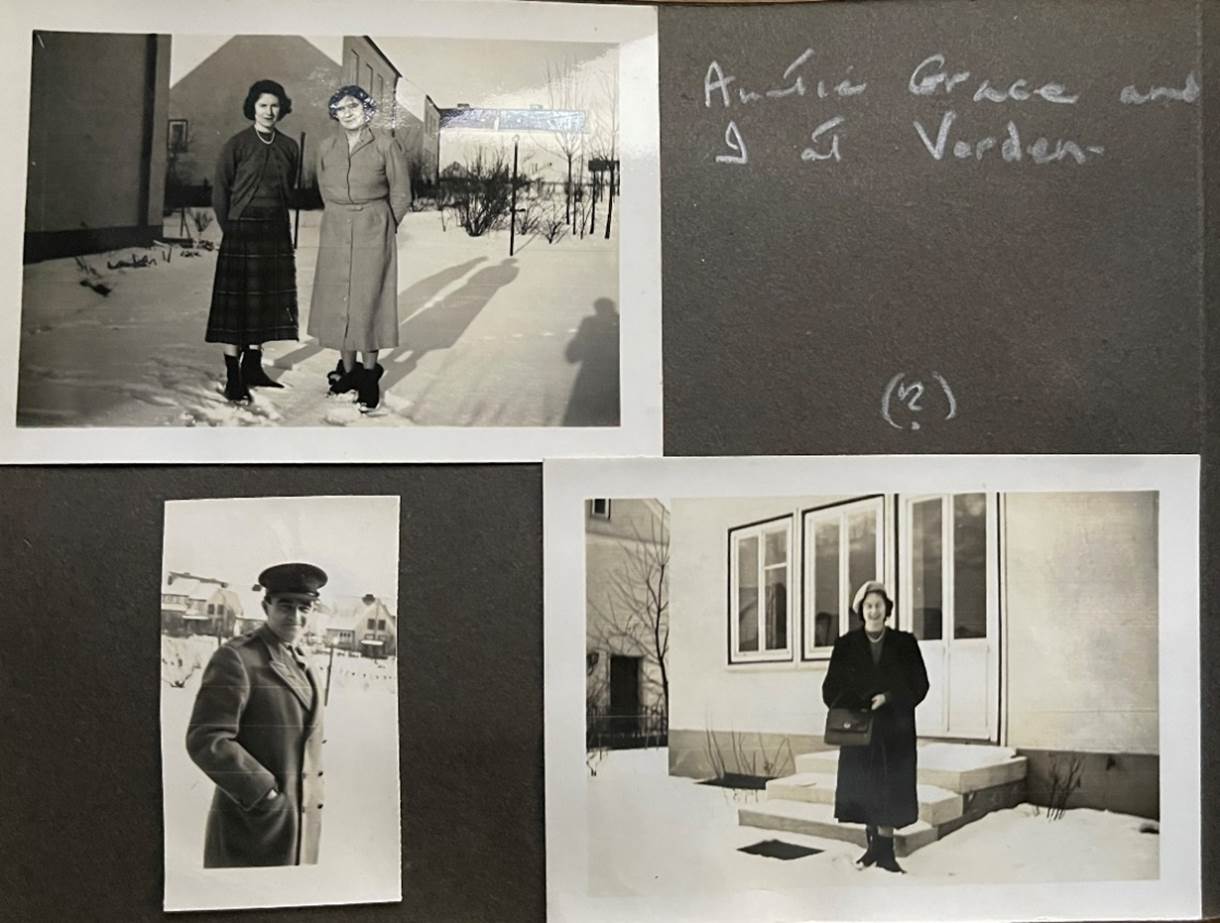

My next visit to Germany was after my marriage in 1955, where I had my first taste of life as an army wife. We moved into a roomy and comfortable quarter in Verden in North Germany, where Martin was at the headquarters of 7th Armoured Division, the famous desert rats. As soon as we arrived, we found ourselves caught up in a non-stop world of cocktail and dinner parties, and these went on at a steady pace most of the time we were there. There were lots of exceptionally nice people there at that time, and we met several of them again in various parts of the world.

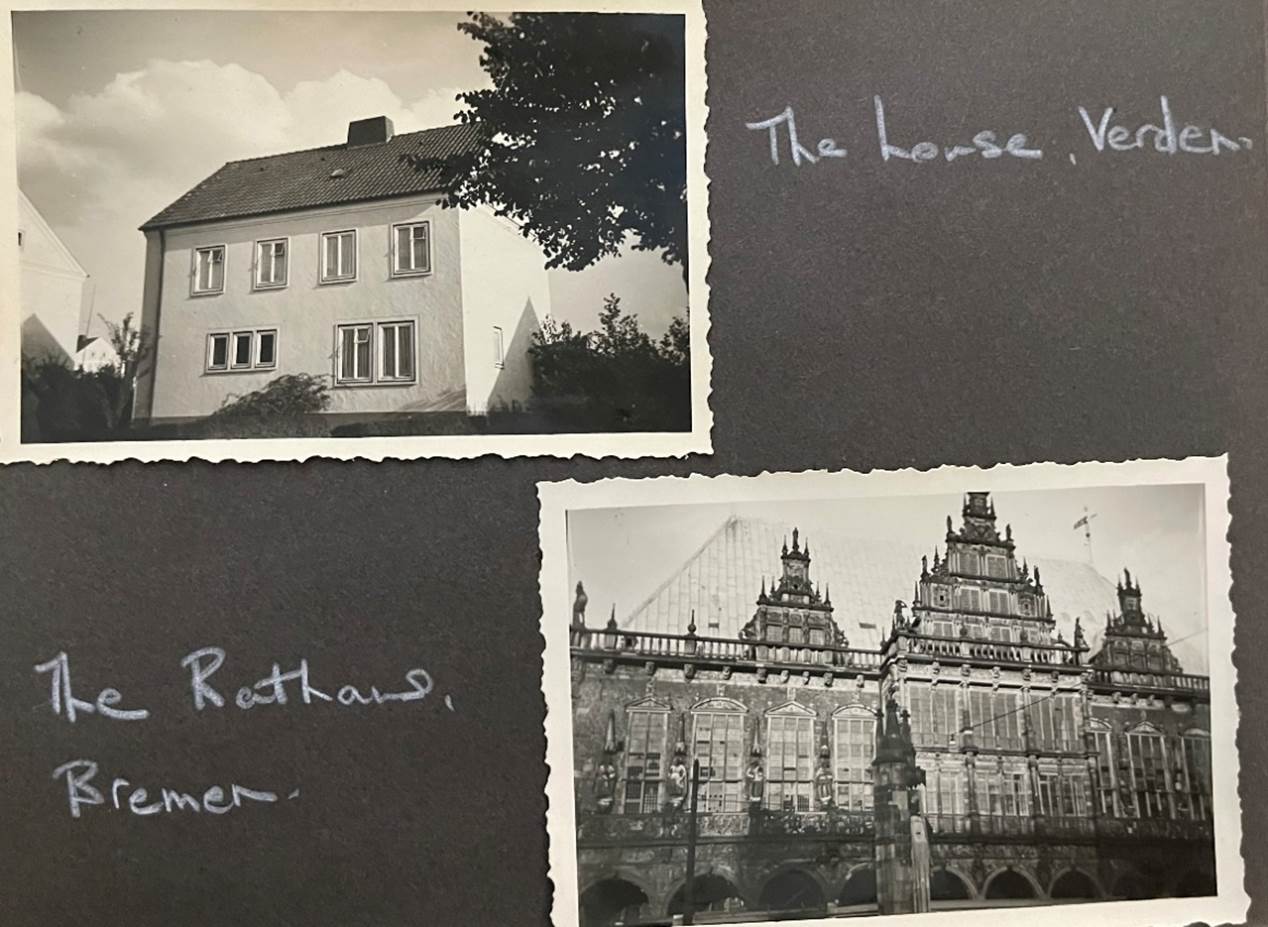

Verden itself was a rather nondescript, medium sized town, perhaps best known for its enormous riding school and horse shows. We saw many Olympic horsemen jumping there, and the most perfect displays of dressage that I have ever seen. The nearest large town was Bremen, 30 miles away, where we often went at weekends. The Germans in the north seemed very dour after the carefree people of Cologne. The winters were bitterly cold, and when I think of the people of Verden, I am reminded of the stall holders at the market sitting stoically by their loaded stalls when the air was so icy that it practically took your breath away. On one of my visits to the market, the Royal Artillery very nearly lost their Macelwaine Cup! This is an enormous silver cup presented each year to the winners of the Royal Artillery Rugby finals. We had collected one of the members of the visiting team from the station the night before, and he had inadvertently left it in our car. The next day I wandered around the stalls, and when I returned to the unlocked car sometime later, discovered, to my surprise, a large silver cup still sitting on the back seat!

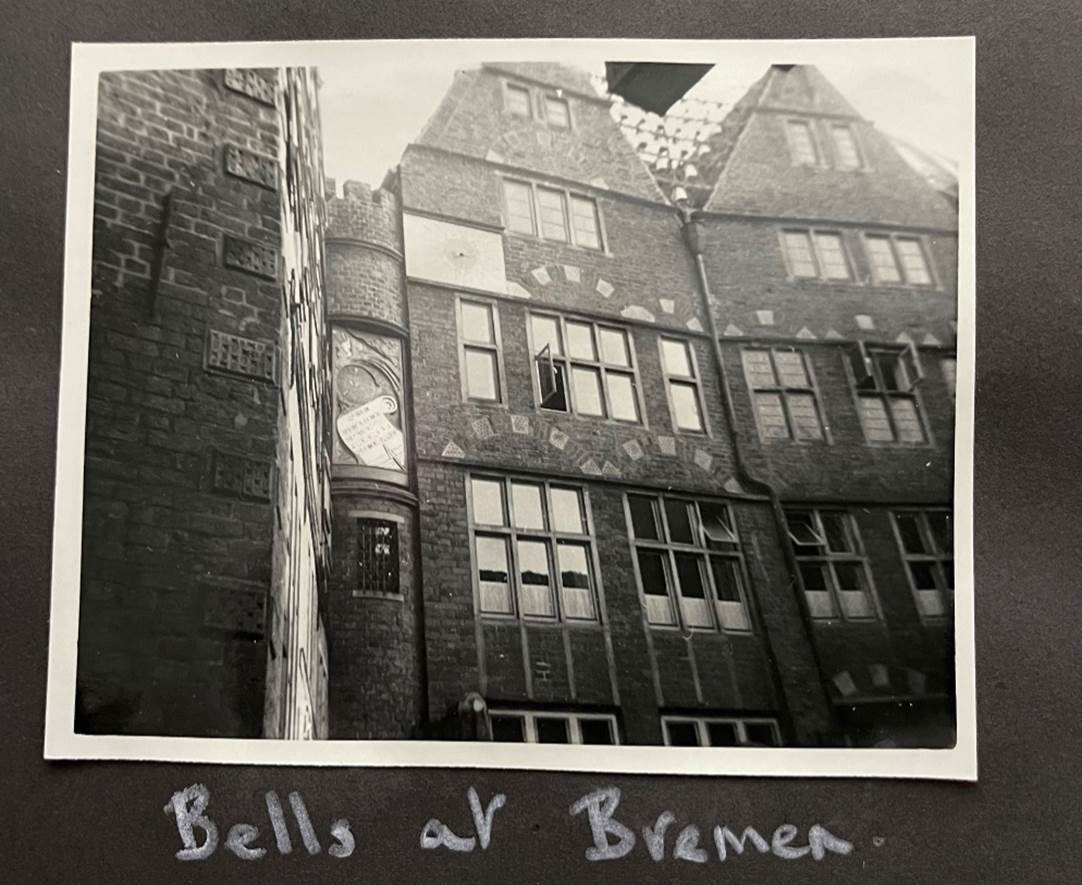

We found Bremen to be a fascinating old town. Luckily the beautiful marktplatz (market square) escaped bomb damage in the war, and the green roofed cathedral and town hall stood unscathed. So much of old Germany has gone forever, and this was a particularly historic and interesting part of the town. We walked down Bottcherstrasse, a narrow street nearby; of most original appearance, and with a cosmopolitan air. One of the high red brick houses has a glass staircase leading to a museum. There are quaint shops selling musical instruments, china, glass etc. A restaurant with Bavarian decor and a myriad of arch ways and beams, making a most unusual overall design. There is a set of bells hung in an inverted V shape under one of the pointed roofs, and when the clock strikes, little scenes start to revolve.

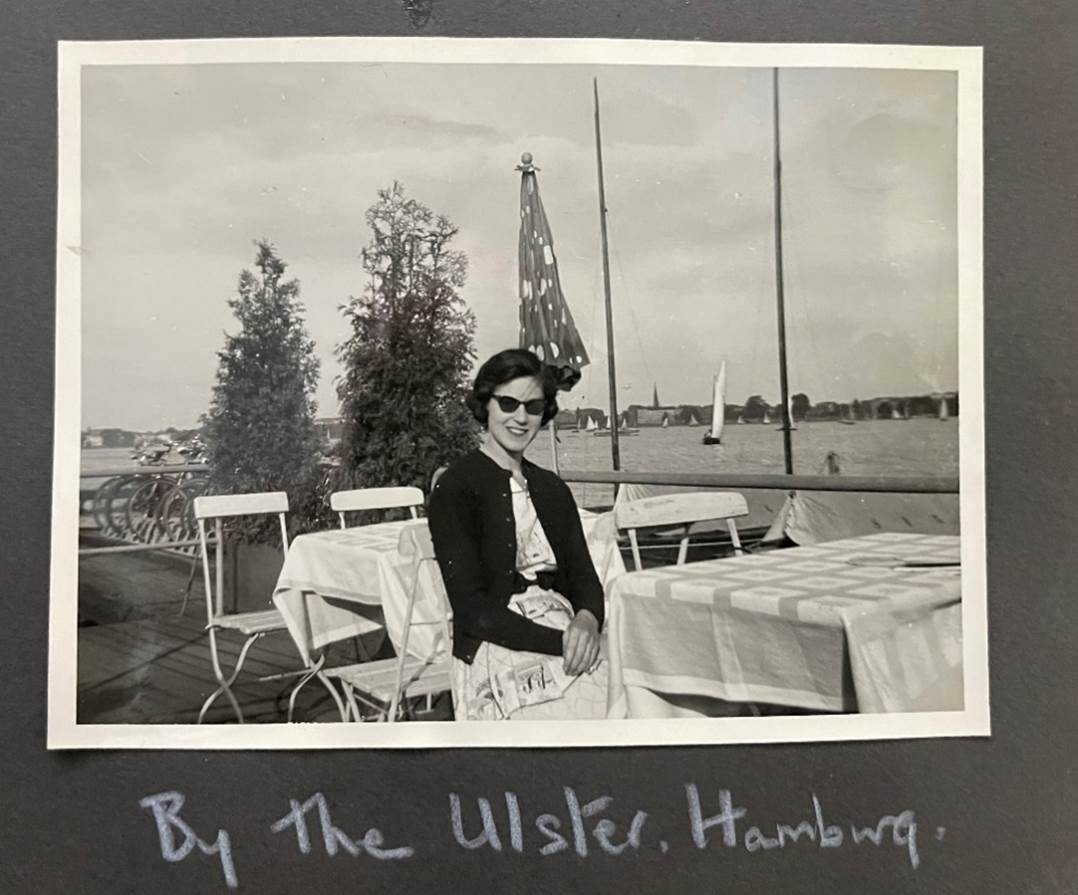

We often visited Hamburg, 90 miles from Verden, and would think nothing of setting off after lunch, speeding up the autobahn and returning home the same night. The dockside covers an enormous area and again it is quite amazing how rapidly the port started functioning again after the devastation and havoc of the bombing. During the worst incendiary raids, the whole town was practically a ball of fire, and the roads were so red hot that it was impossible to put out the fires. In 1955, a great deal of rebuilding had been done, and wonderful shops and Parisienne elegance abounded. The most attractive part of the town is the Alster, and it is wonderful to sit in one of the open fronted restaurants by the side of the lake, watching the tiny sailing boats bobbing on the water. The palatial Four Seasons looks over the lake and has the distinction of being one of the most expensive hotels in Europe. It is very strange to find such a tranquil lake in the heart of a large city, and in the winter when the water is frozen, it becomes an enormous outdoor skating rink.

One weekend we drove up to the Baltic coast equipped with an old army tent and cooking utensils. We eventually came to Travemunde with its casino and gay holiday atmosphere. It was far too cold to bathe there even though it was in the middle of summer. There was a bitterly cold wind blowing in from the sea. It is difficult to imagine it ever being really warm there, but it is possible to hire wickerwork shelters of igloo shape which are dug low in the sand in an endeavour to keep out the icy blast! We drove along the coast until at last we found a suitable camping site, and from our field we could see the Russians only a short distance away across the water. The Germans as a race take camping most seriously and are often equipped luxuriously with modern caravans, tents and every conceivable gadget.

We stayed with friends at Luneburg. The town is mediaeval in appearance and the gables on the houses are of many kinds, baroque and gothic, and the famous old town hall is also a mixture of styles which blend attractively together. We saw the spot on Luneburg Heath where Monty accepted the German surrender, and the monument commemorating that great day, which has since been transplanted to the grounds of the Royal Military Academy, Sandhurst.

Other scattered memories of North Germany include visits to Celle with cobbled streets, castle and tiny gilded rococo theatre, old gabled houses and shops, and an outstandingly good ratskeller under the rathaus (town hall). Many of the larger rathauses in Germany have similar restaurants in the basement, They presumably came into existence originally to keep the mayor and corporation in good humour while debating the towns affairs! Other memories? Of choosing live fish from a bowl, to be eaten at a restaurant at Soltau, of many visits to Hohne, the large military camp a couple of miles from Belsen. When we visited that tragic place, it was overgrown and neglected, a place obviously to be forgotten by the Germans. There was a most surprising feeling of peace there, even though the remains of the gas chambers were still there to be seen near the entrance, and also the horrifying mounds of earth with 1,000 persons buried here and 500 there, all around that dreadful place. The people of the village of Belsen declared often after the war that they had no idea of what had been going on in the camp, though the victims had to walk from the railway siding right through the village. None of the guards were local people, though, but, as generally happened with concentration camps, came from districts as far away as possible. I met a man in Cologne in the Control Commission, who had been one of the first to go in after the camp was liberated. He said he would never forget the horror of it or the disgrace to humanity, the degradation and the shame.

Many service wives in Germany did welfare work at Displaced Persons camps, and for a time I was area secretary of the camp at Seedorf. This work entailed numerous letters to welfare and adoption societies at home, and to the Red Cross. The societies in England would arrange such things as holidays, regular letters and parcels from ‘adopters’ at home, training courses in England for young people, etc. We made regular visits to the camp, about 30 miles from Verden. We would arrive there in a Volkswagen bus, loaded with clothing and food parcels. The camp consisted of a series of dreary wooden huts, each of which housed several families. Some of the rooms were spotlessly clean, with the owners’ few possessions neatly arranged, but others were merely hovels. There were many nationalities in the camp, including a few White Russian emigres who had been there for years, and many of them suffering from tuberculosis. Most of their fit relations had emigrated, but those left behind not able to be accepted in any country until they were cured. Their plight was pathetic, for there were few jobs available in the area. There was little to do all day and not much hope for the future. I remember one particularly sad case of a mother of five children. She was quite young, paralysed and with a brain disease, and while she lay helpless in bed, the grandmother was struggling to look after the whole family. Another woman was alone with a mentally ill daughter. She had managed to find a cleaning job in the village. As she was so poor she had to leave the poor girl locked in her room all day while she was away.

We left Verden and moved into our next home at Mende and for exactly 2 weeks. Almost as soon as we arrived we heard that the Regiment was going to Malta, and busloads of wives were duly dispatched on the first leg of their journey home. Our husbands followed later and encamped temporarily at Shornecliffe, eventually moving not to the sunny Mediterranean but to South Wales.

VIII – Denmark and Sweden (1951)

Bad Salzuflen, Hanover, Flensburg and the Danish border. A timetable, maps, and then Denmark, land of the Vikings. A Foreign Office friend and I were on our way to Copenhagen on holiday. After a long train journey, our spirits soared as we boarded the Danish boat for the trip between the islands towards our destination. After the dour Germans, the Danes on board seemed to be a strikingly pleasant and attractive race. Everything was clean and airy fresh, and this feeling was emphasised by a delicious meal of small smorgasbord (which we were to come to know very well) and best of all, a glass of creamy milk. In Germany we had become quite used to tinned milk, so that this very ordinary drink had become nectar out of a bottle. The Americans had milk specially flown down to Germany from Denmark every day, but we were not so fortunate. Then another short train journey, and again we were struck by the friendliness of the Danish people. Several of them spoke English on the train and were a font of information and advice.

Our hotel in Copenhagen was in the enormous Kongens Nytorv Square, near the splendid Hotel d'Angleterre, and ahead of us was Nyhavn, the canal, with many fishing boats on its calm water and on either side were tall terraced houses. Looking down Nyhavn from Kongens Nytorv, the houses on the right side were rather dignified and include Hans Andersen's house, number 67. On the opposite side, Copenhagen's more lurid nightlife is to be found. Hot and smoky cafes, vcellers for dancing and drinking, where artists and fishermen congregate, and the usual assortment of intriguing left bank characters. The whole has a rather nautical air, as befits such a seafaring nation as Denmark, with figureheads from ships over some of the doors, and tattoo shops. Several of these have pictures of the Danish king outside smilingly showing his tattooed arm.

Copenhagen is a sophisticated town of elegant and beautiful women, enticing shops; it is a town of contrasts, and a good deal of its charm lies in this sophistication mixed with the simpler life of the markets, canals and harbour, one complements the other. The markets are very gay, with a riot of flowers and rich dairy produce., and the fish market at Gemmel Strand is supposed to be the oldest in the world, it is well over 700 years old. There seemed to be green roofs everywhere in Copenhagen. In Radhuspladsen the town hall has a green tower, and another attractive one is the twisted spire of the Stock Exchange. It takes about 20 years for copper to turn green, because of the large amount of salt in the air. Yet another green spire is that of Our Saviour's Church, topped by a golden ball and nine feet high statue of the Saviour. We climbed up and up and eventually, quite exhausted, found ourselves in a gallery with enormous bells overhead, and this led onto a sunlit platform with a wonderful view of Copenhagen toylike below. This Spire is the second highest in Copenhagen, beaten only by the town hall. With a deep breath we realised that we were still not at the top. We plodded up yet another 150 steps, the spiral getting narrower all the time, and at last came to a sudden halt with the golden ball directly above us.

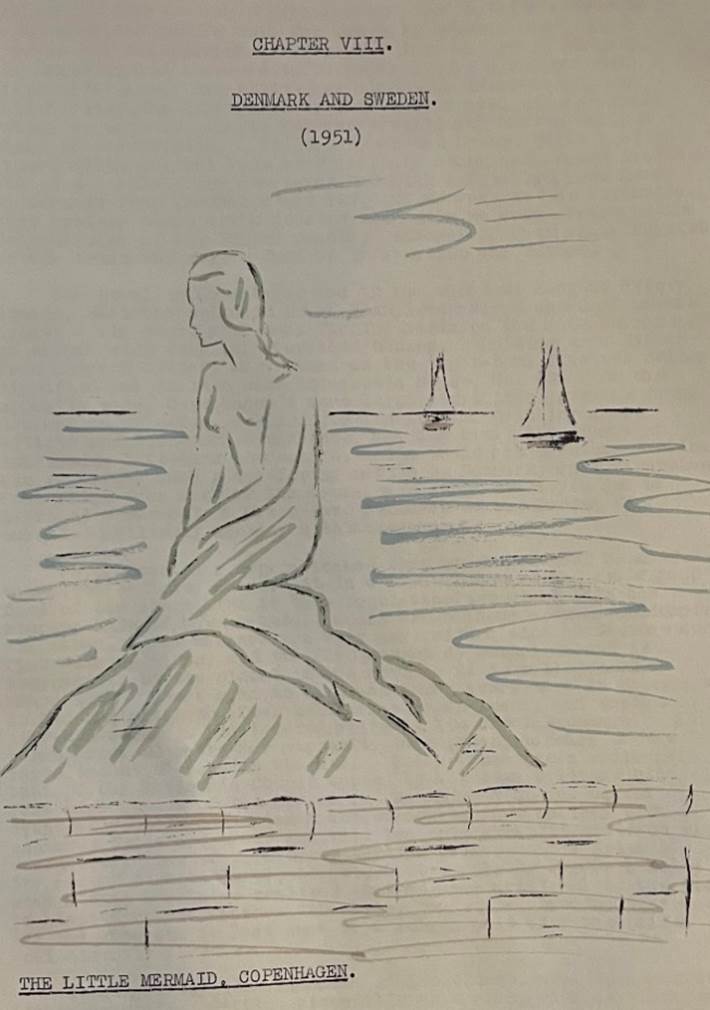

Walking along the promenade of Langelinie, we discovered The Little Mermaid. Sitting gracefully on a rock, with her back to the sea, she is quite small and perfectly lovely. Her sculptor was Edward Eriksen and his wife was the model. A short distance away is the Gefion fountain, with four enormous oxen constantly splashing in the foam, harnessed to a plough, guided by the goddess Gefion, the whole effect is one of terrific power and movement.

Copenhagen is not really an old city and has had a somewhat hazardous past. In 1728, two fifths of the buildings were destroyed by fire and to make matters worse, Napoleon’s bombardments also did considerable damage. We visited many castles, including Rosenberg., the Rose Palace of Copenhagen, which was built by Christian V, also Christianborg, part of which is used as Parliament House. Fredensborg, north of Copenhagen, is the summer palace and contains a collection of very rare original Flora Danica porcelain. This is part of a set which took more than a decade to make and originally contained nearly 2000 pieces, making a complete pictorial encyclopaedia of Danish flora. Some of it was destroyed when Christianborg was burnt down and some were stolen, a few of the pieces that are left are in museums, but the rest is still to be seen at Fredensborg.

Unfortunately, we did not visit the Royal Copenhagen porcelain factory where the girls work in an open air atmosphere of trailing greenery. The girls who do nothing more than routine painting, are on piecework and it is a very coveted job for those who are artistically inclined. The few experienced artists who paint the Flora Danica and model figures are very highly paid, and for many of them it is a lifelong work. When the colours are first painted, they're very bright, but turned pastel after firing. Only metallic. colours are able to stand up to the terrific heat comma and the other colours have to be added after firing.

We were taken to dinner at a restaurant with, of all things, a Scottish village decor, and another evening, we very naturally visited the Tivoli Gardens. Tivoli is only open during the summer months and we were lucky to be there a week before it closed. It is a unique place, quiet and dignified, with no trace of a fun fair atmosphere. This is provided for at Drrehavsbakken in the Deer Forest, which is a much noisier and rowdier place, and is one of the largest amusement parks in Northern Europe. Tivoli has elegant flower bedecked restaurants with candle lit tables, fairy lights and rainbow fountains. The Chinese Pagoda restaurant has a genuinely eastern atmosphere and excellent Chinese prints on the walls. There is a new concert hall and an air of enjoyment and leisure. When we were there we watched a performance by the Royal Danish Ballet; The Danish ballerinas and corps de ballet are among the best in the world, and the performance was one of perfect beauty and grace. We watched the performance out of doors on a warm autumn evening, and it was certainly an experience to remember. We imagined that the idea of the Festival of Britain Gardens must have originated at Tivoli, but ironically the creator of Tivoli got his inspiration from the old Vauxhall Gardens in London, and his aim was to create a sophisticated London atmosphere mingled with a touch of Italy.

The Danes as a race are very civically minded. The old people are well cared for and for the workers there are ‘colony’ gardens. These consist of plots of land with little wooden chalets, where they can take their families for weekends for a nominal rent. When the university is closed for the holidays, visitors can rent the students’ bedrooms and can enjoy an inexpensive holiday in the peaceful book bedecked rooms. The Brondbyhus is a hotel near Copenhagen for young offenders who have been convicted. They have approved jobs and can live at the hostel for just three pounds a week. It is run by the Danish Welfare Association, with government assistance, and has proved a great success, and few of the inhabitants have returned to a life of crime. Kofoeds Skole is a sombre building founded by Hans Christian Kofoed to care for the homeless. Its aim is to give them back their self respect and encourage them to make a fresh start, and the scheme might well be copied to advantage by other countries. Each new arrival is given a working card and gains points for having a bath, cleaning his shoes, washing and ironing his clothes, taking vitamin pills and for doing odd jobs. Every day he has to do these things in order to get food and a bed, and soon, without realising, he becomes accustomed to an ordered life, and in successful cases, the desire to make a fresh start is felt. The young men can later go to agricultural schools for training.

A large number of Danish homes are modern and centrally heated and, as in Holland and Germany, they all seemed to have rows of trailing pot plants in the windows. Thinking of houses, one's mind automatically returns to food, which in Denmark is a particularly fascinating subject. The Danes, as is well known, practically live on smorrebrod, of which there are literally hundreds of possible varieties of topping for the rye bread. The choice is really almost endless. Smor means butter and brod means bread, and some of the more delicious toppings include liver pate, smoked salmon with anchovy fillets, shrimps and other seafood in mayonnaise, pickled held hearings and raw onion rings, smoked eel with scrambled eggs and a host of others.

We visited a famous Copenhagen restaurant which has a 3 feet long smorrebrod menu, and they send their delicious packages all over the world by air. A meal in Denmark often starts with a ‘sheltered’ dish, not hot, as all food is served warm, and this will almost inevitably be followed by a smorrebrod. During a meal the host has the privilege of toasting each guest in turn whenever he feels so inclined, the toast being skaal and as schnaps is particularly strong, the guests frequently become somewhat dazed. I remember going to lunch in London with the man I was working for and his wife. They had been to Denmark and Sweden and had brought a stock of schnaps back with them. I can vaguely recall working during the afternoon in a very pleasant rosy haze! Cherry Heering Brandy is another Danish speciality. At the end of a meal the Danes, who are a very polite race, say tak for mad - thank you for a good meal, and I remember in Norway one said tak for matten which is very similar.

The Danes are very fortunate in having a really good bathing beach only a few miles from the centre of Copenhagen. We were driven out there by some people we met at the hotel who later took us on other expeditions. We went to Elsinore or Kronborg Castle, which is its real name, and from there Sweden is only 20 minutes away across the water by ferry. Hamlet is performed there regularly in the courtyard and some famous British actors have played there, including Olivier, Gielgud and Michael Redgrave. The odd thing is that nobody seems to know whether Shakespeare ever actually visited Denmark, and if Hamlet really existed at all, it would have been many years before the castle was built! In spite of all this, Elsinore. Is undoubtedly the perfect setting for the play, and one could almost imagine the ghost materialising on the parapet.

On midsummer's eve all over Denmark, the witches are burnt, a slightly grisly reminder of the only too real witch hunts of the Middle Ages. Gigantic bonfires are built along the coast and the ragdoll witches are tied to stakes. As soon as it is dark, the fires are lit and tongues of vicious orange flame leap into the sky and then to the sound of singing the witches topple into the flames and are consumed.

We visited Malmo in Sweden for the day. This is only a short trip by boat and many Danes cross frequently to shop. We only had time for a quick sightseeing tour and particularly remember seeing large numbers of enormous new blocks of flats, again gaily decorated with innumerable fllower pots, and bright, coloured blinds. I suspect that Malmo was not particularly representative of the country as a whole.

On another trip to Denmark many years later I went with my family to Jutland and to the museum at Silkeborg, to see the remarkable and famous Tolland man. He apparently has a perfectly preserved and human expression after 2,000 years. He was discovered in a bog and had to be quickly immersed in a 100% alcohol solution to prevent him deteriorating, a cheering debut into the 20th century! Permanent preservation was such a costly business that it was decided only to preserve his head. It is incredible to think that through the centuries, his wise and tranquil expression has remained unchanged.

Denmark is a country of undoubted charm, and returning to Germany, everything seemed rather dull in comparison.

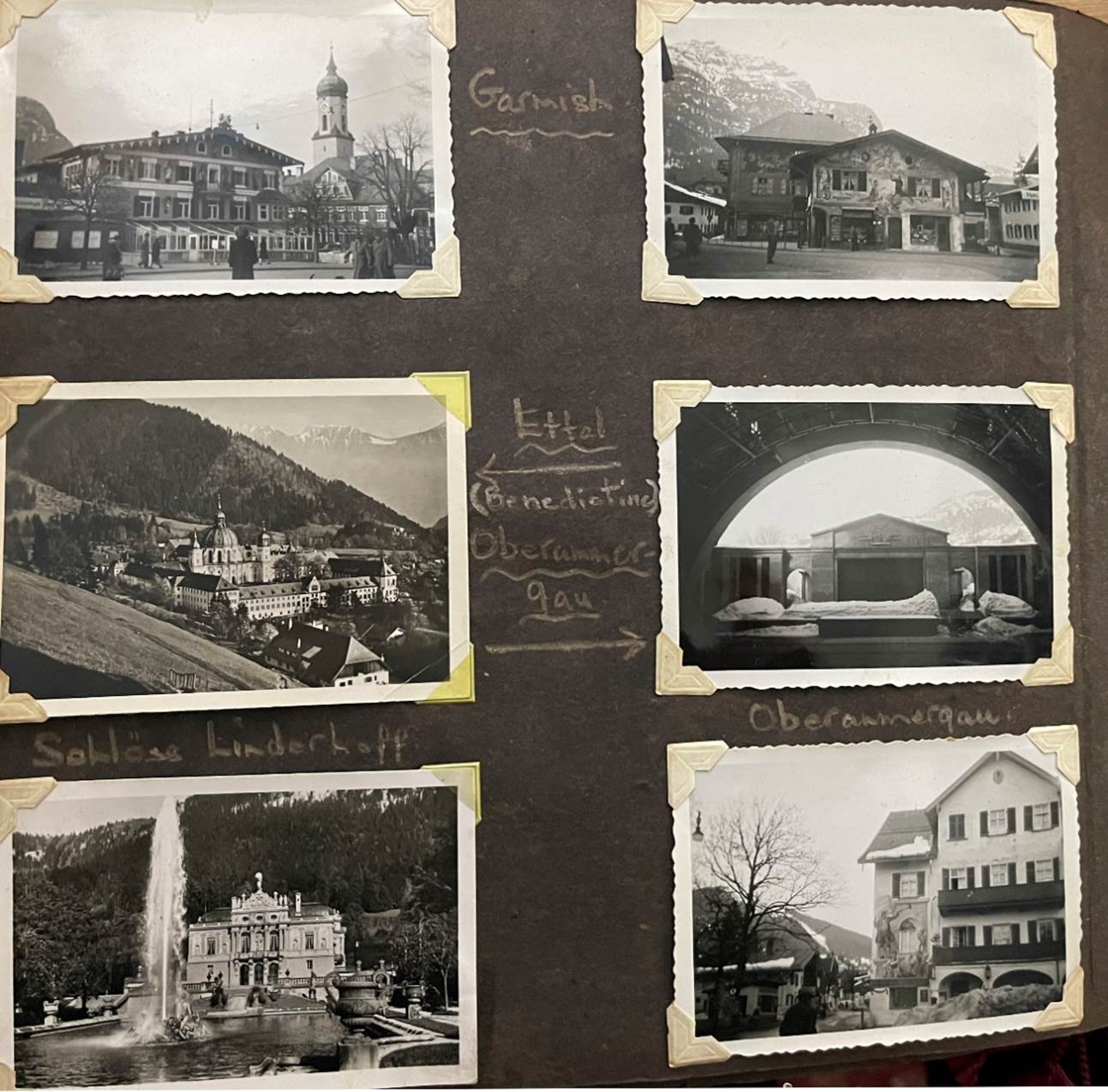

IX – Austria and Bavaria (1952)

Intending to leave my flat in Cologne at 5:30 AM, I sleepily heard the doorbell ring. It was the taxi, and the alarm clock had failed to go off. I tore round the deserted flat like a tornado, grabbed a chunk of bread and marmalade, forced a few things still to be packed into my case, and five minutes later we were heading for the station.

I was going to Austria via Munich, and thence to the ski centre at Lermoos. The journey seemed to be never ending, and three changes of train were necessary. This, as usual, entailed a good deal of sign language, as disgracefully my German extended little further than the market, and none of the porters seemed to understand English. At long last, the train stopped at Ehrwalt and I was then transported to a delightfully Austrian gasthaus at Lermoos, to find Janet (from the next door flat in Cologne) already in Schonste. She had arrived the week before by military train and was already in the top skiing class.

Lermoos and Ehrwalt were both service ski centres and we were allowed to use them as we were given the equivalent rank of captain while we were working in Germany. The Austrian centres were generally much nicer than the German ones, and the skiing better, and in fact, Lermoos consisted of a number of small gasthauses staffed entirely by Austrians.

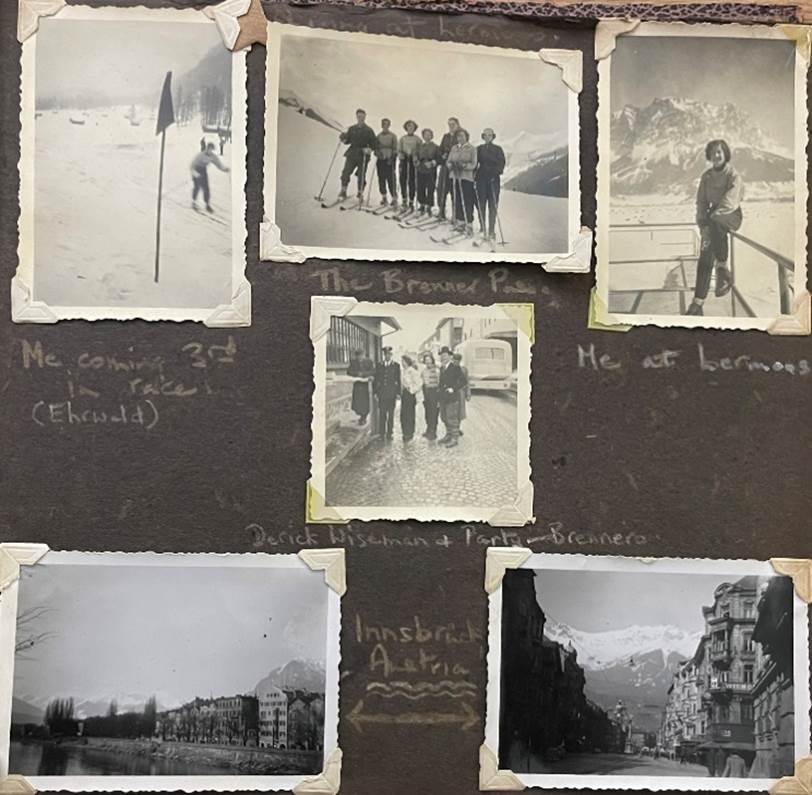

The next morning, with the rest of my ski class, I glided smoothly up the mountainside on the ski lift and discovered one of our wives from Cologne who had just arrived on holiday with her husband. We then had a wonderful time sliding and gliding down the slopes, and soon got the feel of our skis again. The last part of the run ended in full view of the largest hotel, where crowds of people were generally sitting on the balcony sunning themselves and having drinks, so it was advisable. to fall over elsewhere, if at all possible, or it was better to ski in really fast stopping dramatically with a neat Kristiana and flurry of snow at the hotel entrance! Our class consisted, I think, of six girls and one major who seemed to land more often than the rest of us in a tangled heap in the snow. He and some friends hired a car to drive to Innsbruck a few days later, and asked me to go to. After a beautiful drive through miles of craggy whiteness, we reached our destination, that sleepy town with the mountains rising crownlike, all around. We motored a little further to the Italian border at Brennaro, and then back to Lermoos in the evening.