The Jarrow March 1936

The story of the Jarrow March of

1936, of which Johnny Farndale, was the youngest member

Economic

Slump

Although the

First World War caused a post war economic boom in Britain, it masked a slow

industrial decline from the country's Victorian ambition. As wartime demands

gradually fell away, by 1920 Britain was plunged into an economic slump with

high levels of unemployment and poverty. The situation was made far worse by

the world wide recession of 1929, Unemployment was at 10% throughout the

1920's, and peaked at 22% in 1932.

Britain's

traditional industries were particularly hard hit meaning that the North of

England, Wales and Scotland, which had economies heavily dependent upon

manufacturing, were disproportionately affected by the slump. This meant that

these regions actually suffered far higher levels of unemployment than the

national average. The effects were long-lasting, rather than following a

regular economic cycle of prosperity and recession.

During the

1920's, the National Unemployed Workers' Movement (“NUWM”) organised a

serious of hunger marches to London in the hope that these would force

the Government to radically rethink its economic policies. The term hunger

march was first used to describe a march by London's poor in 1908. The marches

achieved nothing. The official view was that the government was being

high-jacked to serve the aims of their Communist organisers.

The end of

the world-wide recession in 1932 allowed Britain to begin a slow path to

recovery. By 1936, economic growth had reached 4% and mini-booms were being

seen in housing and consumer spending. However, the recovery was badly uneven.

Those areas which had seen their traditional means of employment devastated

during the slump were very slow to see any improvement.

Jarrow

The town of

Jarrow, lying on the southern bank of the River Tyne, had undergone a massive

period of expansion during the Victorian era. Its economy was based on

precisely those industries - iron, steel, shipbuilding - which were so badly

hit by the post war depression.

Charles Mark

Palmer, the so-called King of Jarrow, had created an industrial empire

in the town but gradually each of these businesses failed in turn. Unemployment

stood at 3,300 in 1930 or 75% of the working population and at 6,793 in 1932 or

80% of the population. When Palmer's Shipyard failed in 1934, the town lost its

last purpose for existing. As the town's newly elected MP, the firebrand Red

Ellen Wilkinson, so forcefully pointed out in the Commons in December 1935,

the years go on and nothing is done. This is a desperately urgent matter and

something should be done to get work to these areas which, heaven knows, want

work.

The

hunger-march had become an accepted form of protest and in July 1936 the town's

political leaders set in progress plans to mount a march from Jarrow to deliver

a petition to Parliament calling for the opportunity to work. Over 1,200 men

came forward to take part, but it was decided to limit numbers to the 200

fittest and hardiest to make the logistics manageable. A fund was started to

pay for supplies and equipment and this would continue to collect donations as

the men marched south. Rallies were scheduled for the march's overnight stops

to spread the word of what it was trying to achieve. As one marcher put it, we

were more or less missionaries of the distressed areas, not just Jarrow.

The

Peaceful Protest

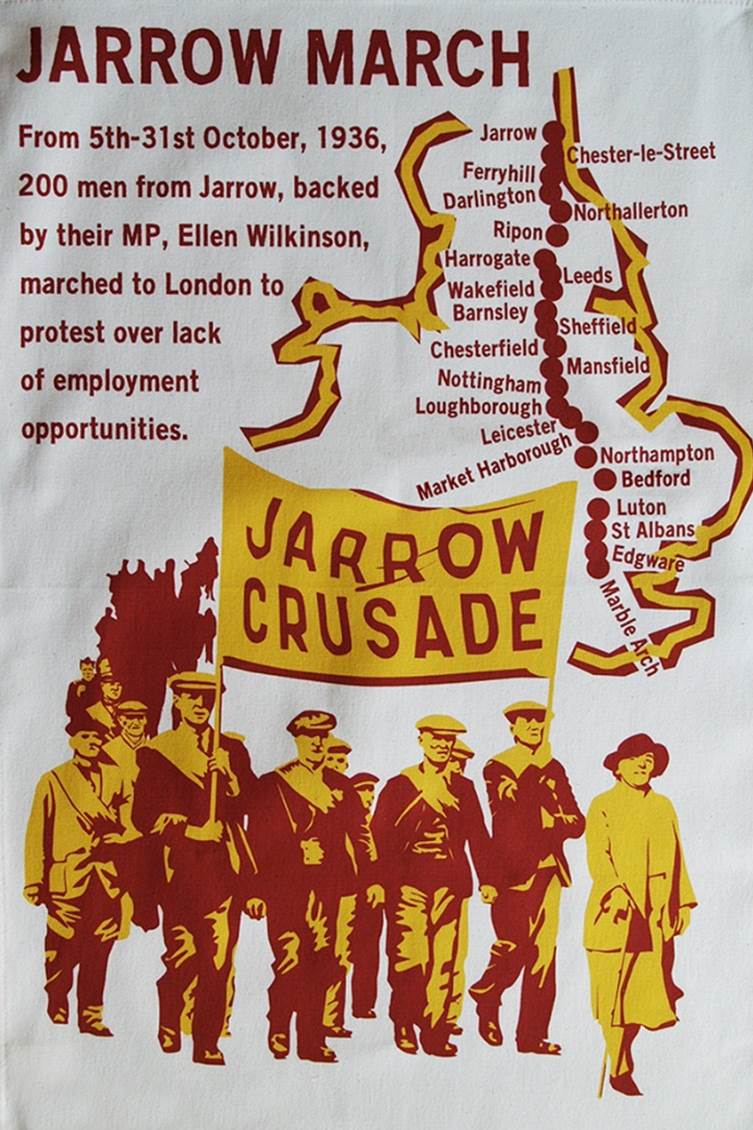

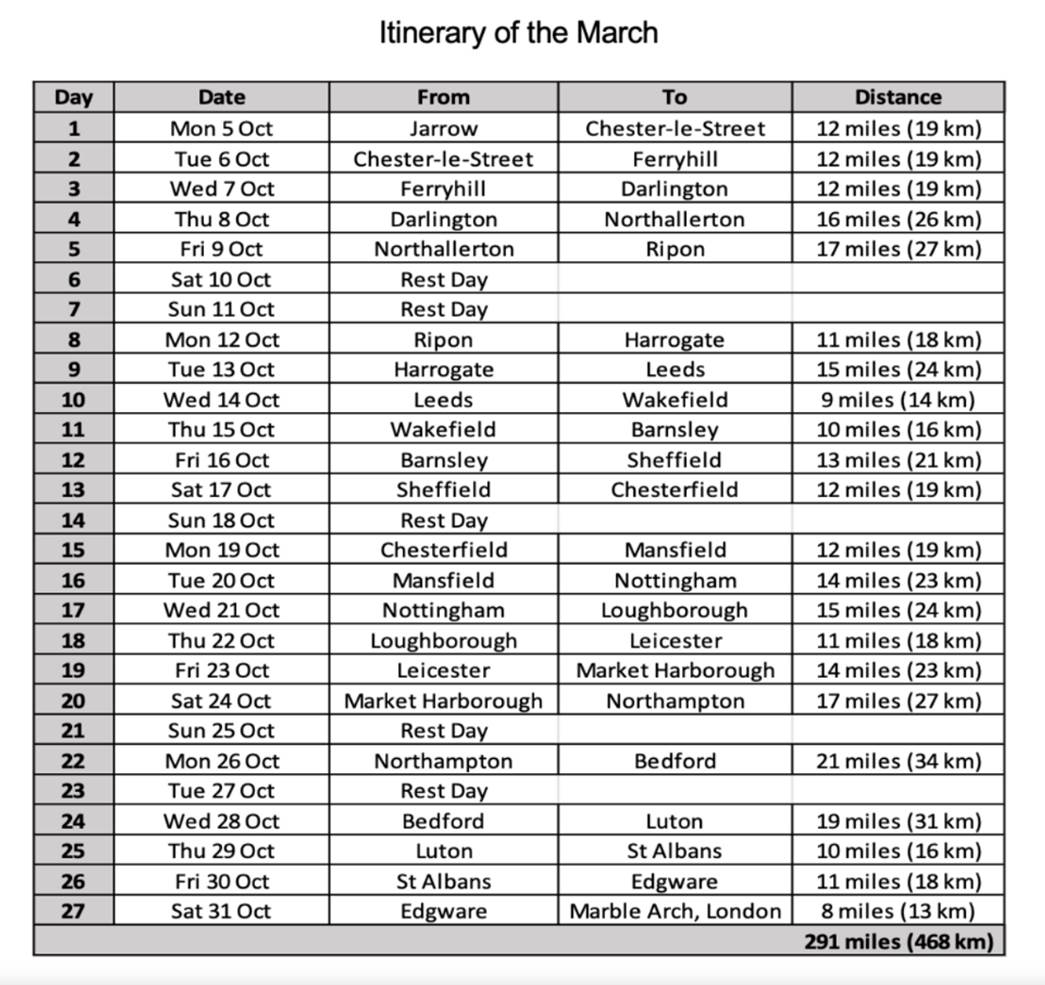

On Monday 5

October 1936, the date set for the start of the March, the Marchers received

the blessing of the Bishop of Jarrow at a dedication service in Christ Church.

This gave the venture a boost in credibility, but the service was condemned by

Hensley Henson, the Bishop of Durham, who was opposed to the Trades Union

movement and Socialism. Henson condemned the hunger marches as a whole as

nothing but a vehicle for the Labour Party and his colleague in Jarrow, James

Gordon, was later obliged to state that the service was not intended to condone

the March. To add injury to insult, the Marchers later discovered that their

dole had been stopped as the March had made them unavailable for work.

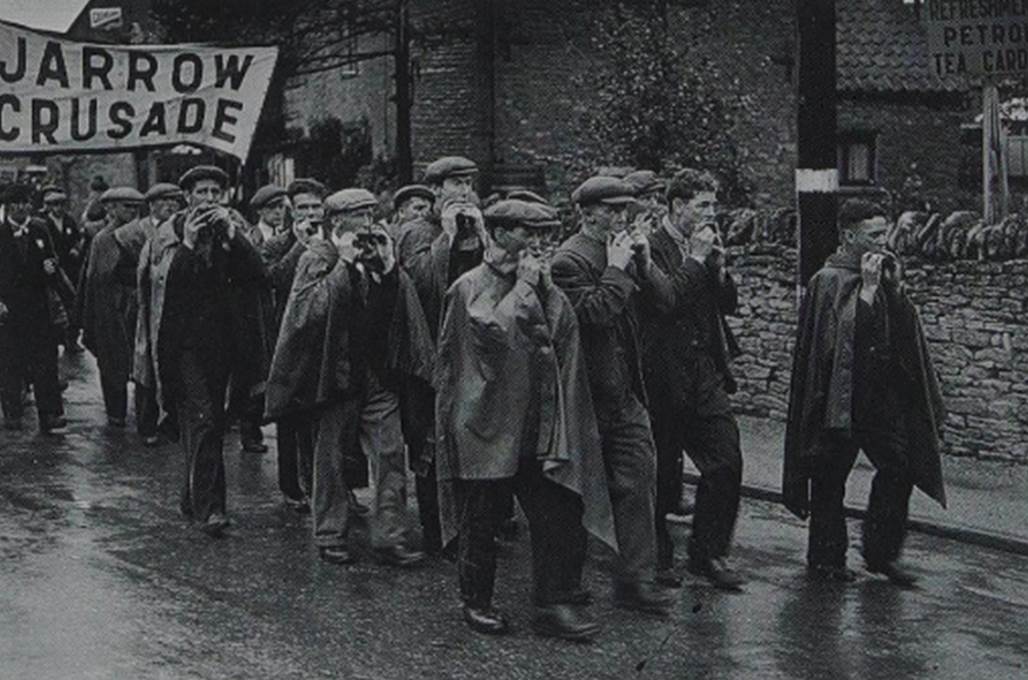

Immediately

after the service, the Marchers assembled at Jarrow Town Hall and made their

last preparations before setting off. Although 200 men had been accepted for

the venture, only 185 made it to the start-line due to sickness and other

changes in personal circumstance. Around half of those taking part were

veterans of the First World War and the Marchers walked in step and in military

ranks to show their discipline and proclaim their past service. They took a

10-minute break every hour, in the military manner, and a harmonica band

encouraged the singing of popular songs of the day to keep their spirits up.

Before them they carried a blue-and-white banner proclaiming the Jarrow

Crusade though in Jarrow it was never known as anything other than The

March. Again in the military tradition, behind them followed a bus with a

field kitchen, a medical facility, and camping equipment for when beds were not

available.

The Jarrow

March was one of a number of concurrent protests. The sixth National Hunger

March was setting off from 6 regional centres and these were due to unite in

London a week after the arrival of the Jarrow men. Meanwhile, a group of blind

veterans were marching in protest at the treatment of the nation’s 67,000

registered blind persons. The National Marches were seen as hostile and

confrontational, and this undoubtedly aided the high level of publicity given

to the Jarrow March which, by contrast, was recognised for its moderation and

quiet dignity.

Ellen

Wilkinson temporarily left the march at its first stopping point, in

Chester-le-Street, to attend the Labour Party's annual conference in Edinburgh.

Although it was proclaimed to be non-political, the Jarrow March was a product

of the town’s Labour Council and she may have hoped to gain some support from

her colleagues. In this she was to be disappointed, however. The Parliamentary

Labour Party (“PLP”) was a minority part of the National Government and

anxious to distance itself from any accusations of Communism. So, neither the

PLP nor the Trade Union Congress (“TUC”) offered endorsement. David

Riley, the Chairman of Jarrow Borough Council and a leading light in the

organisation of the March, later complained that they felt that they had been stabbed

in the back.

As they

moved south, the reception extended to the Marchers varied from indifferent to

warm. Local accommodation was secured in a series of schools, church halls or

other buildings, and often gifts were made of food and clean clothing. Often

the weather was bad, cold with driving rain.

Very quickly

the March began attracting wide publicity and the Government in London, afraid

that it was gaining Royal attention, acted to limit sympathy for it, claiming

that such Marches only resulted in unnecessary hardship for those taking

part in them. Wilkinson continued to push for an official reception for the

Marchers, but received no encouragement from Prime Minister Stanley Baldwin

during heated exchanges in the Commons. In truth Baldwin was in an impossible

position, for opening Parliament’s doors to the Jarrow Marchers would have set

a dangerous precedent.

The March

reached Edgware in northern London on Friday 30 October 1936, leaving a

relatively short eight mile walk to Marble Arch the following day. It had been

denied permission to deliver its petition to Parliament and so Ellen Wilkinson

had to make the last stage of the journey alone.

Ellen

Wilkinson’s address in Trafalgar Square

The original

petition, calling for Government aid for Jarrow, had 11,000 signatures and was

carried in an oak box. An additional petition had been made available to those

who had wanted to sign on the way.

A new

session in the House of Commons was convened on 3 November 1936. The March had

been timetabled to take advantage of this and next day the Petition was

presented. A very brief discussion followed after which the House returned to

its normal business.

The March

garnered a lot of publicity, a lot of soft words, but achieved little real

change. This was not lost on the marchers themselves and the return journey

home by train was a sombre affair.

Not until

the outbreak of the Second World War in 1939 did Jarrow start to recover from

its long period of depression. When Red Ellen published her history of

Jarrow that same year she titled it, The Town that was Murdered.

Johnny

Farndale

Johnny

Farndale was the youngest member of the 185 men who set off on the Jarrow

marches in October 1936.

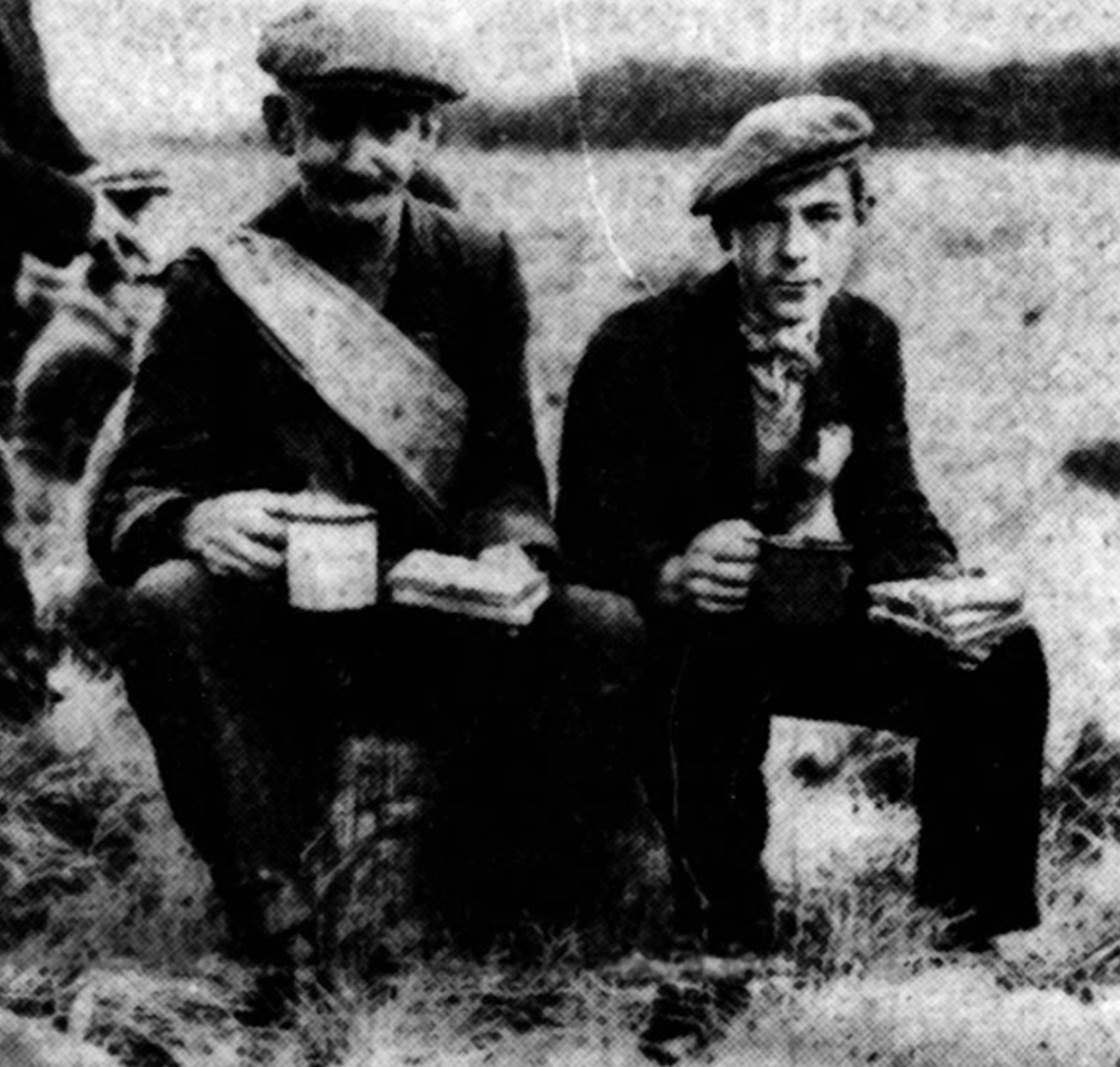

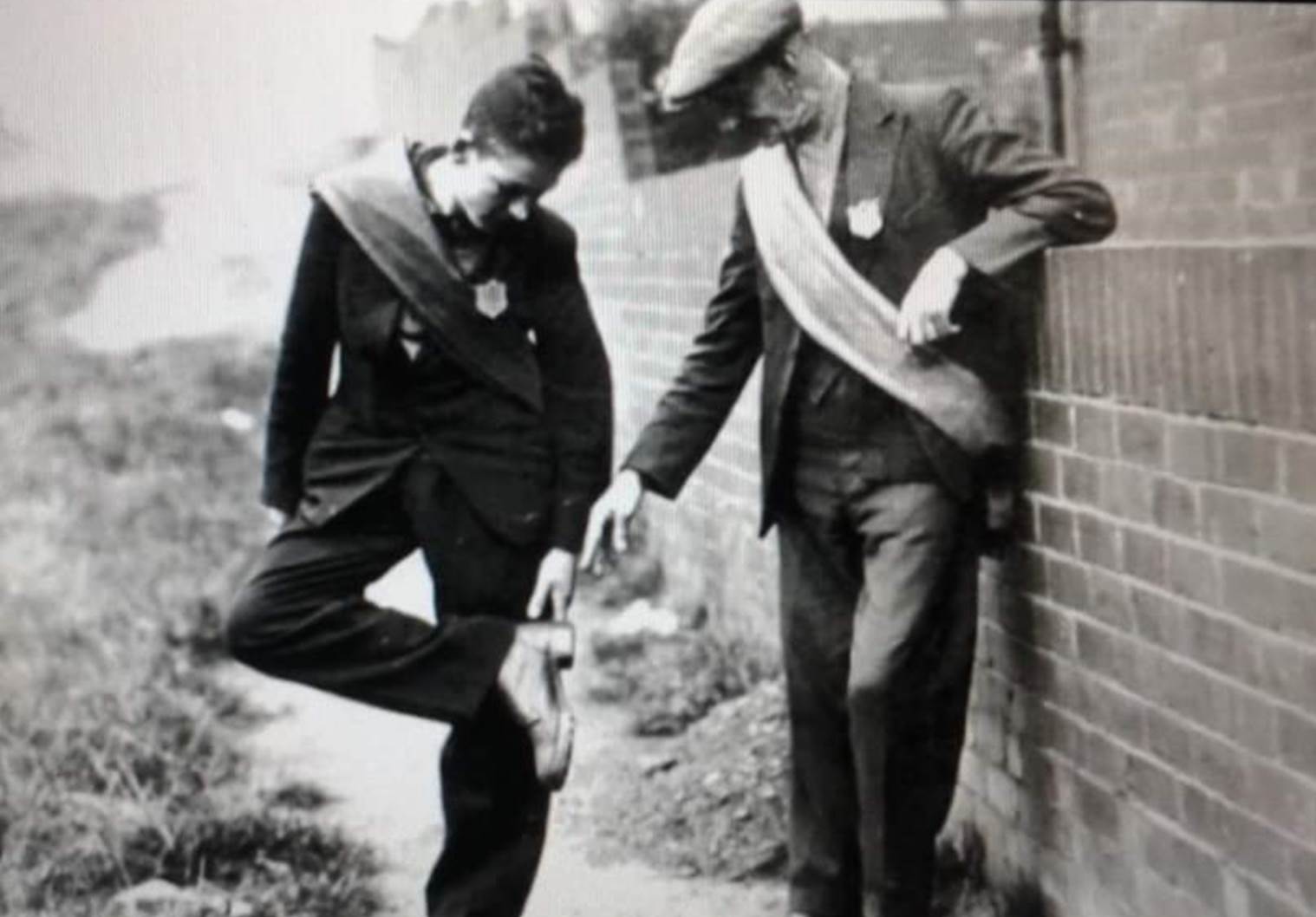

Boer War veteran George Smith, aged

61, and 18 year old John Farndale, the oldest and youngest member of the Jarrow

band of workers

George Smith, the oldest marcher,

examines the boots of the youngest marcher, John Farndale

On 5 November 1936 hundreds of

people watched the departure of the special train containing the Jarrow

Marchers from Kings Cross station today. Mr P Malcolm Stewart, formerly

Commissioner for Distressed Areas, said goodbye to them, and also on the

platform was Miss Ellen Wilkinson MP, who had been with the men during their

crusade, and who presented the petition in the House of Commons. The men

expressed disappointment at the reception of their petition, but were gratified

at the general attitude of people in London towards them. Alderman J W

Thompson, Mayor of Jarrow, who returned with the men, said to a Press

Association reporter: “It was as I expected. I cannot say that I am

disappointed at the way the petition was received, but I feel now that the people

in the South have a more intimate knowledge of our plight in Jarrow, and from

that I expect some result.” One of the marches, John Farndale, of Clyde Rd,

Jared, has taken a job as a baker's assistant in London, and another, Thomas

Dobson, of Stanley Street, Jarrow, is staying at Hendon Cottage Hospital for a

few days for treatment before returning.

or

Go

Straight to Johnny Farndale

There

is a BBC podcast, the

Jarrow Crusade.

Long Road from Jarrow: a journey through Britain then and

now, 2017, Stuart Maconie

Then and Now Jarrow,

Paul Perry, 1999 is a pictorial history of Jarrow.

The

novels The Jarrow Lass by Janet Macleod

Trotter, 2001, Return to Jarrow, Janet Macleod

Trotter, 2004, and A Child of Jarrow, Janet MacLeod

Trotter, 2011, tell of Catherine Cookson’s grandmother in Jarrow at that time.

See

also The Town that was Murdered, the Life Story of Jarrow,

Ellen Wilkinson, 1939, especially pages 191 to 213.

J’Accuse, the Autobiography of a headteacher in Jarrow

1934 to 1963, Claude Robinson, 1986, especially

p60 to p66.

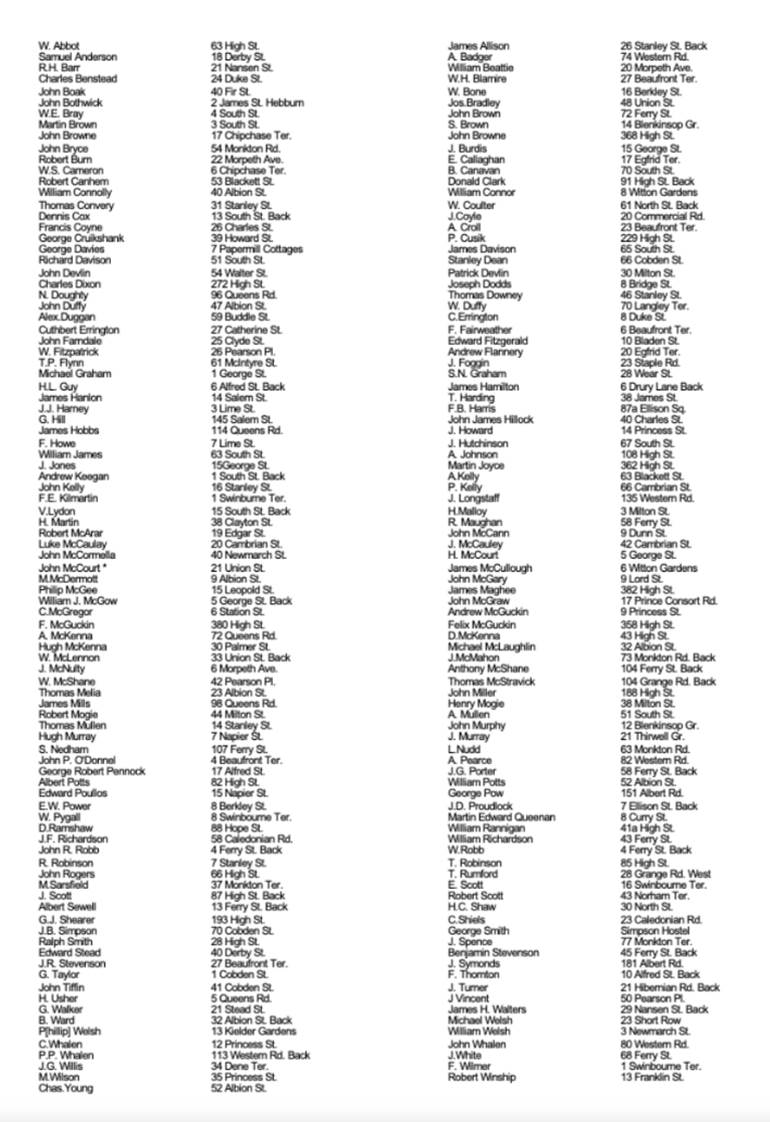

Who were the

Jarrow Marchers? You Tube Documentary