The Story of the Farndale Research

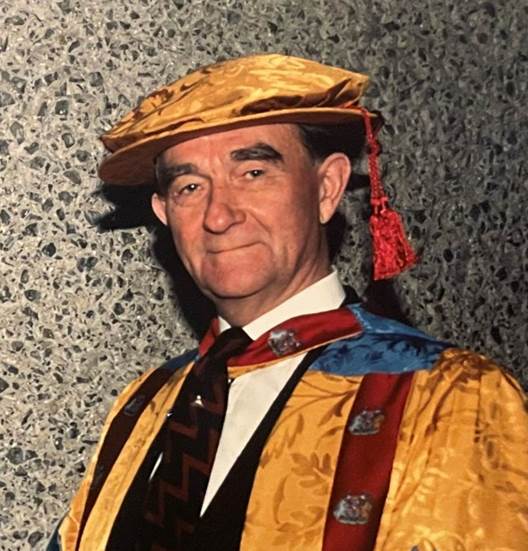

Martin Farndale received an Honorary

Doctorate of Letters from the University of Greenwich in 1995

A history of the genealogy

The

passion behind the genealogy

Martin

Farndale (1929 to 2000) began to work on the genealogy of his family in the

1950s. It became his passion even though he worked on the family history

alongside an extraordinary military career which took him from Regimental

Command to command of the British army based in Germany in the 1980s and to

command of the Northern Army Group of NATO, the north half of the defensive

force of Western Europe during the Cold War.

Martin was a

passionate historian and as well as his genealogical work, he wrote definitive

histories of the Royal Artillery, a task which he started early in his military

career and continued until he died. He wrote the History

of the Royal Artillery, France 1914-1918, published in 1987. He wrote the History

of the Royal Artillery, The Forgotten Fronts and the Home Base, 1914-1918,

published in 1988. He wrote the History

of the Royal Artillery in the Second World War (The Years of Defeat 1939-41),

published in 1996. He wrote the History of the

Royal Artillery (The Far East Theatre 1941-1946, which was published

posthumously. He also wrote many articles for the British Army Review and the

Royal Artillery Journal.

He was also

Chairman of the English Heritage Battlefields Trust from

1993, a trust which endeavours to preserve battlefields from being destroyed by

new roads and building. Martin succeeded in saving the site of the Battle of

Tewkesbury (1471) from developers. He took part as a guest lecturer during a

number of battlefield tours covering both the First and Second World Wars.

Following his command of the Regiment, he became Honorary Colonel of First

Regiment Royal Horse Artillery and of the 3rd Battalion the Yorkshire

Volunteers in later years and continued to be passionately involved with those

Regiments and their historical heritage.

From 1989

until his death, he worked tirelessly to create a museum of artillery at the

Royal Arsenal, Woolwich. This was known as the Royal Artillery Museum Project

and became Royal Artillery Museums Limited, of which he was Chairman. The

museum opened a year after his death in May 2001 and was known as Firepower. It

housed the vast regimental collection of guns, medals, books and archives and

provided an interactive museum of the history of artillery. The principal

building of the museum was now known as the Farndale Building and a plaque at

the entrance was dedicated to Martin and stated without his vision,

dedication, leadership and commitment, this museum would not exist. The

collection is now the

Royal Artillery Museum.

Martin

became a Freeman

of the City of London and a member of the

Wheelwrights Livery. He was appointed Companion of the Most Honourable

Order of the Bath in 1980 and Knight Commander of the Order of the Bath in

1983. He was a member of the

Royal Patriotic Fund. He was Chairman of the Royal United Services

Institute.

His passion

in the Farndale family history and his pioneering work, and meticulous

collection of historical records is the root of the Farndale Story. He put

together family trees on sheets of paper which he would spread out across the

breadth of rooms to show off his latest discovery. In an age before computers

he visited Parish Churches one by one, and explored parish records, taking

meticulous notes to piece together the jigsaw. He had boxes of index cards in

his Study which provided the only means by which to build the family story in a

time when there were no genealogical databases or websites and no computers

with excel spreadsheets and modern tools for word processing. When he came to

write up sections of the story it was done by typewriter. He nevertheless

identified most of the members of the Farndale story through time and found

many of the medieval records which it has been possible to explore more easily

in recent years. The scaffolding of the family history was already complete

long before computers made the task an easier one to undertake.

Perhaps most

importantly, Martin understood the importance of preserving records. He

relentlessly pursued his immediate family to work through their photographs and

make sure they were properly labelled. He also made sure that all those many

documents that seemed so unimportant in their contemporary setting, were

retained to tell their story to future generations. Long after his death, his

sister has often recalled to me how absolutely terrible he was at insisting

photograph albums and other material were subsumed into the family collection.

He also had discussions with members of the wider family and took notes of

their own stories, which have been passed down, and provide first hand records

of their lives. Furthermore, having identified the extended family members

through his genealogical research, he started lines of correspondence with

those members of the family who lived in such places as New Zealand, Canada,

the United States and Australia. He left albums of material which tell the full

story of the history of branches of the family such as the Australians,

including photographs, documents, newspaper clips, explanations and more. The

richness of the material which he left is unique.

When he came

to a dilemma which he couldnít resolve, he employed professional genealogists

to resolve questions in the family story. There was extensive research into

military histories of individual Farndales. I still have extensive rounds of

correspondence with relatives, genealogists and others, with whom he engaged,

in his relentless pursuit to preserve the heritage of his kin.

Martin Baker

Farndale died at the age of 71 in a London hospital on 10 May 2000. He is

buried at Wensley Church, Wensleydale, in North Yorkshire beside his parents

and in the heart of our familyís historical stage.

In his last

few days in a London Hospital, there was a discussion about the legacy of

family history which he had left. To Martinís only child, Richard Farndale, the

family history was his Dadís obsession, a part of his Dadís world which dated

back as far as he could remember, and regarding which he had dutifully nodded

when family stories were retold, and patiently looked on when yet another

family tree was unfurled for explanation. It was not yet an obsession which had

passed down to the next generation. The richness of the legacy and the

privilege of the unique perspective which it gave, was not yet appreciated.

Foolishly perhaps, as one does during the last days of a life, particularly one

that ended too soon, a promise was made. Personal computers were just beginning

to be used more widely and the internet had recently emerged as a new tool full

of possibility. The promise was made to turn Martinís work into a website, so

that the family story which Martin had preserved could be enjoyed more widely

by the family and others who might find it of interest. There was a happy glint

in Martinís eye which embedded itself into his sonís memory. The deal was

sealed. There was no going back.

Twenty

first century genealogy

It was

almost exactly at the moment that Martin Farndale finished his genealogical

research, that exponential new opportunities started to emerge as means by

which a genealogy could be developed. Genealogical databases were created by

such organisations as Ancestry and Find my Past which allowed

most of the records upon which genealogists rely, to be accessed at home from a

personal computer. No longer was it necessary to travel between parish churches

as Martin had done. Medieval records also became accessible and search tools

improved so that over time, searching for a name like Farndale, which bore a

uniqueness that meant that any search revealed helpful information, became much

easier. Archived Newspapers also became accessible so that stories associated

with the names that had already been found brought life to individualsí

experiences. Database tools and hyperlinking between documents provided a new

means to analyse the information as it was collected. Since the information

could be published on a world wide web, members of the wider family came to

find the genealogy and send emails to share their own stories. Photographs

could be scanned and incorporated into the wider story.

The

underlying structure of the research, worked on by Martin since the 1950s and

the meticulous collection of family records that would otherwise have been

lost, provided the underlying basis of the research, without which the later

work would have been too daunting. Martin Farndaleís deep interest in

genealogical story telling was an incentive to explore its boundaries in a new

age of possibilities. It is also extraordinary for a son to work on the same

material worked on by Martin, and solve problems which he was grappling with,

sometimes to solve them with new tools, and in doing so, to feel a

connectedness. I recommend genealogy to pass through generations as a means to

continue to share a family passion through time.

The

genealogical journey has provided a structure from which to explore the history

of the places with which this family have been associated, and to explore the

nationís story from a particular and unique perspective. It is a direct path

into history which makes its understanding far more profound than a more

isolated exploration of the past. The research has brought me to a direct

perspective on Britainís history from Roman, Anglo Saxon and Scandinavian

times, to Norman and medieval and later industrial and modern periods. The

simplest form of genealogy is like stamp collecting. It can be fun to build

family trees and collect family members, but it is hard to find passion in the

scaffolding of a family tree. The more profound reward of genealogy is to be

found in the stories and the journeys it takes you on, and the wider historical

context which gives it meaning. When genealogy combines with history, to follow

a more multi disciplinary route, it becomes a far

more powerful tool of exploration.

The Farndale Family Website and the Farndale Story are manifestations of

a passion, that started some time in the 1950s, and has passed to another

generation. It is not a commercial venture, but it is hopefully a source of

material which will be helpful not only to family descendants, but to those

interested in local and social history.