|

|

Towns

The evolution of towns in northern Britain

|

|

Headlines are in brown.

Dates are in red.

Hyperlinks to other pages are in dark blue.

References and citations are in turquoise.

Context and local history are in purple.

Geographical context is in green.

1100

After the

Norman Conquest people living in towns did retain some degree of autonomy

and wealth. There was an influx of urban immigration resulting from the

Conquest, but the indigenous urban population remained influential.

There was a growth of:

·

Primitive

bankers (‘moneyers’)

·

Moneylenders

(including the Jewish communities)

·

Goldsmiths

·

Merchants

·

Administrators

and royal officers.

Life was not always straightforward.

There was congestion and poverty. There were episodes such as Henry I’s purge

on moneylenders leading to castration and hand amputations.

A new type of town, the borough, emerged

in Norman England. In contrast to agricultural towns, they did not rely

directly on agriculture, but on other means such as trade, crafts

or other services. Often land was set out around castles for borough towns, for

instance at Thirsk, Skelton and Scarborough.

Thirteenth century

Each borough developed in its own way.

The town of Whitby moved away from the old

village on the east cliff down to the waterside and absorbed the old Flora

estate into Flowergate.

None matched the scale of York as a

centre for craftsmen.

Fourteenth century

Population expansion led to new

settlements growing in the countryside. Towns were created more rapidly than at

any other time. Over 50 were established between 1200 to 1320.

London was the biggest with a population

of circa 80k. Norwich was second at 20k. The next level of towns were perhaps circa 5k. Most towns had under 2k.

Many now held annual fairs.

Towns started to be defined as boroughs

with their own charters and local systems of government evolved.

By 1377, York had 7,248 adults paying

the poll tax, and may have had a population of about 15,000. It has absorbed

many migrants from the countryside, particularly impacted by the devastation

caused by the outbreaks of plague in rural

areas.

A concentration of small crafts made York the industrial centre of Yorkshire and it

developed specialities such as 11 goldsmiths, 12 pin makers, manufacturers of

rivets, armour plate and locks as well as York pewterers.

Outside York, the largest boroughs were Scarborough (1,391 taxpayers), Whitby (641), Pickering

(435) and Northallerton (373). Towns

such a Kirkbymoorside (511) were about the same size, though included the by

then populous Farndale.

Fifteenth century

The customs and liberties of the

burgesses of Malton were recorded in writing. The burgesses had a free court

with 2 bailiffs and 2 under bailiffs, a burgess clerk and 12 sworn burge4sses

would form a jury. The court met twice a year around Mihalemas

and on the morrow of St Hilary. They levied four pence fines or could impose

prison, a pillory, a thew or the rack.

The Borough of Malton had gone a long

way to removing control by the lord.

(John Rushton, The History of Ryedale, 2003, 142 to

143).

The Victorian Age

Coal, steam and machinery reshaped

society by concentrating populations in towns around mines, factories and workshops..

In the 1851 census 54% of England’s

population lived in towns (in France, only 19%).

In the following two decades:

·

Total

production nearly doubled.

·

The

length of the railways douvbled.

·

The

number of railway pasengers

doubled.

·

Freight

tripled.

·

The

tonnage of steamships increased by 600%.

·

About

1.5M new houses were built.

·

The

rate of income tax halved from 7d in £ (2.9%) to 4d (1.6%).

·

Old

buildings were demolished en masse.

The new towns were smelly, smoky and noisy. Development was uneven. There were new

civic buildings, monuments and public utilities. This

was accompanied by slums and rows of uniform red brick houses.

Cities were also starting to develop

globally – New York, Calcutta, Shanghai, Essen, St Petersburg.

New literature from Dickens and later HG

Wells reflected the change as did art.

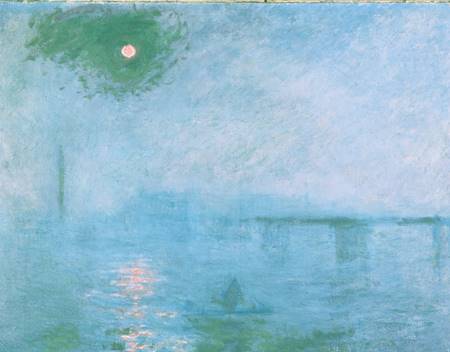

Charing Cross Bridge, Fog on the Thames,

1903

In 1850 a quarter of the population lived

in large towns of over 100,000, mostly industrial centres, like Bradford, Sheffield and Leeds.

The fragmentation of development was

chaotic, and as pioneers of urban growth, Britain made many mistakes.

However

death rates and infant mortality were low on the global scale, below Sweden,

but above France, Germany, Spain, Russia and US. Inevitably infant mortality

was higher in poorer areas.

The greater representation of government

and the network of local authorities coped relatively well with the new growth.

By the 1880s:

·

Britain

strove to a better minimum health standard than other countries.

·

Cities

had invested in sewers and water facilities.

·

Sanitary

inspectors reduced over crowding and adopted measures

to control pollution.

By the 1840s, the average number per

house in the East End was 6.4 and 30% of homes were well furnished (ie including a piano!).

The

growth in non agricultural production meant the

population had to be fed by imports. Since 1822 Britain’s balance of trade has

remained permanently in deficit. It had to be balanced by invisible earnings

from banking, insurance and shipping, and returns from

foreign investments.

This

brought new kinds of wealth (commerce, manufacturing, food and drink, tobacco)

and new wealthy families, like the Rothschilds and the Guinness’s. Someone of

the very richest, like the Duke of Westminster, continued to derive their

wealth from their land holdings, but now because they benefitted from mineral

rights.

There

were very significant disparities of wealth:

By

1914, 92% of wealth was owned by 10% of the population.

In

the 1860s:

·

The

population was around 20M.

·

4,000

people had incomes over £5,000 per year.

·

1.4M

had around £100.

·

A

farm labourer might earn £20.

·

Women

workers earned about half of men’s wages.

There

was a rise in wages from mid century, with a significant

rise in 1873.

However in rural areas, wages lagged behind.

Living

standard improved with a fall in the birth rate. The sharpest increase in

spending was tobacco – the mechanically produced Wills Woodbines at 1d for five were popular from the

1880s to the 1960s. The consumption of alcohol fell sharply.

The

Industrial Towns, depicted in Disraeli’s Sybil, established their own traditions and institutions.

·

In

textile towns such as in Lancashire and elsewhere, people played together, sang

in choral societies together, voted together and holidayed together.

·

Mining

industries formed brass bands.

·

New

sports grounds and works teams emerged.

·

Neighbourhood

clubs provided some security for unemployment, burial costs, clothes, medicine and Christmas.

·

Charities

expanded.

·

There

was a multiplication of cooperative societies, savings banks

and friendly societies (like the Independent Order of Oddfellows, and the Ancient Order of Foresters). By

1901 there were 5.47M members of friendly societies.

·

There

was a growth in trade unions.

o

“Combination”

by workers became legal in the 1820s.

o However

the Master and Servants Acts 1823 and 1867 continued to punish workers for

breaking contracts.

o The Employers and

Workmen Act 1875

recognised a right to collective bargaining and soon led to unionisation being

seen as a right.

o This was a contrast to the position in

France, Germany and US. The British workforce became

more unionised.

o Unions tended to be peaceful but adversarial

with employers.

o The Victorian Working Class had a

recognised and independent place in the social order.

·

Medical

insurance developed.

·

Voluntary

hospitals were funded by donations.

There

were increasing attempts to improve the quality of life in towns.

·

A

growth of parks, gardens and allotments.

·

New

suburban districts with villas with gardens.

·

Gardeining became a popular hobby.

·

The

planned urban estates of Regency London, Bath and

Edinburgh.

·

Communities

of workers were created by such people as Titus Salt.

There

was a new sentiment for rural England from the towns. In many cases, these new

organisations were largely driven by the provision of amenity for town

dwellers.

·

The

Commons Preservation Society 1865

·

The

English Dialect Society 1873

·

The

Society for the Preservation of Ancient

Buildings 1877

·

The

Folklore Society 1878

·

The

Lake District Defence Society 1883

·

The

Society for the Protection of Birds 1889

·

The

National Trust for Places of Historic

Interest or Natural Beauty 1895

·

The

Folk Song Society 1898

·

The

English Folk Dance Society 1911

·

The

National Trust Act 1907 allowed the Trust to declare land

inalienable.

·

Thomas

Hardy novels

·

A E

Housman’s A

Shropshire Lad

1896

(Robert Tombs, The English and

their History, 2023, 477 to 492).