|

|

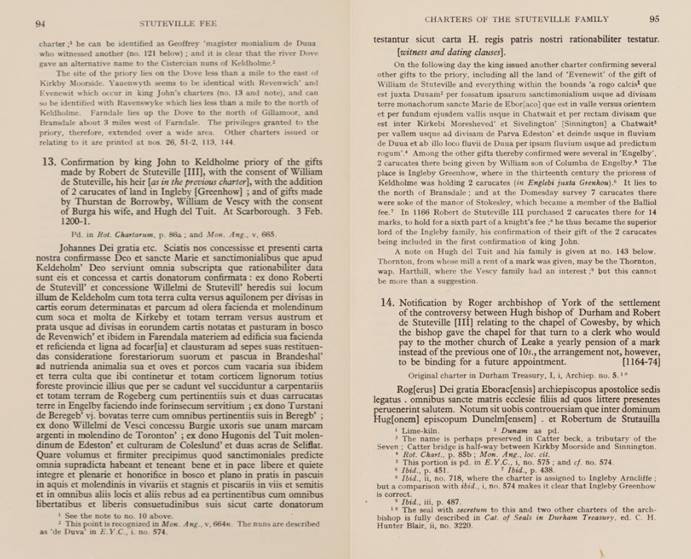

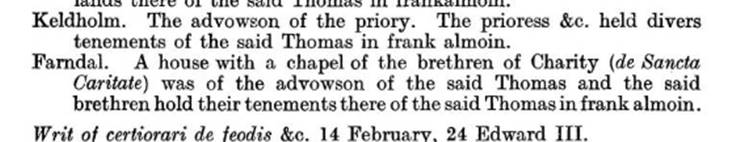

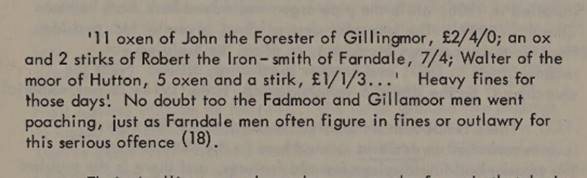

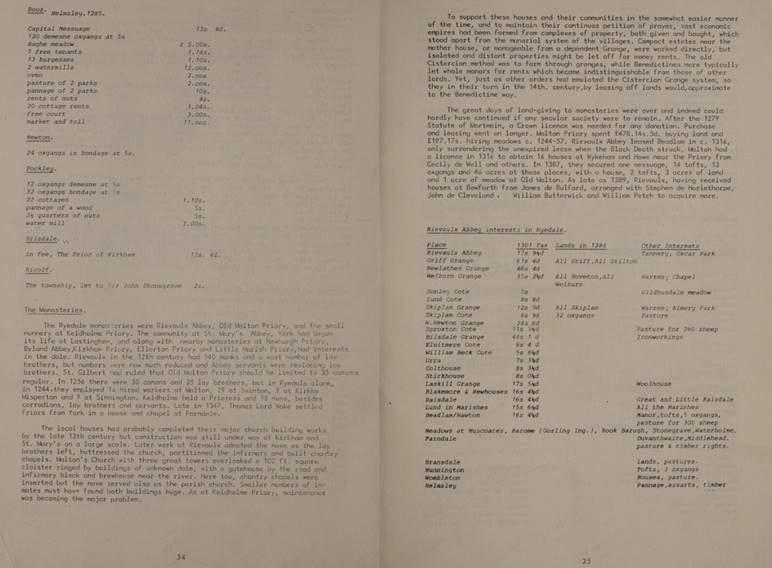

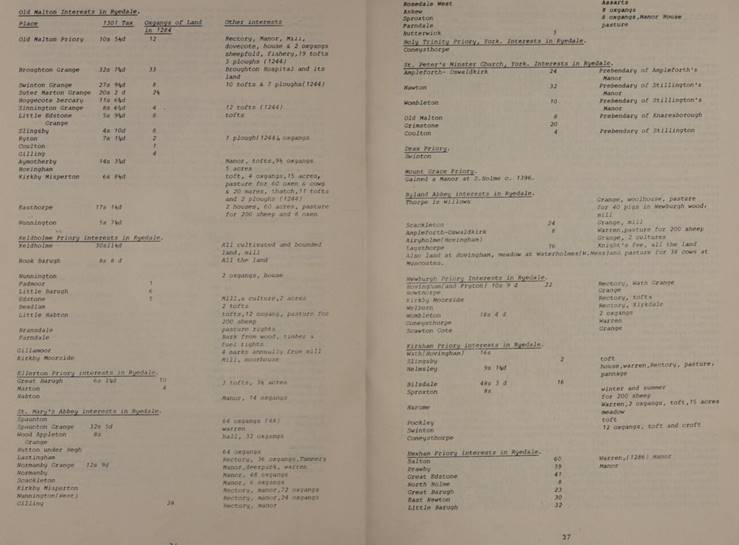

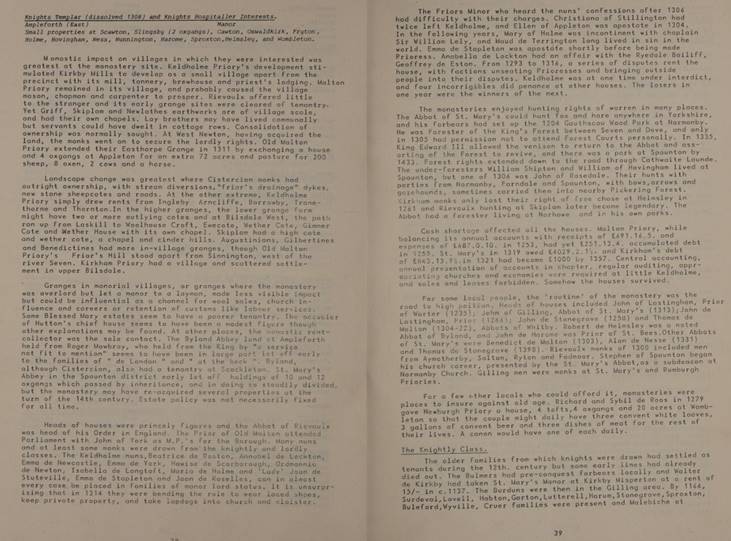

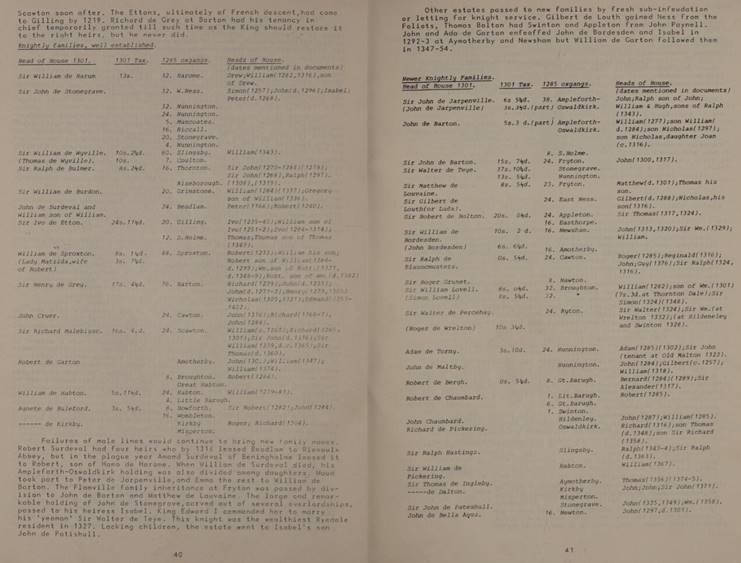

Farndale

Historical and geographical information

|

|

Introduction

Dates are in red.

Hyperlinks to other pages are in dark blue.

Headlines of the history of the Farndale

are in brown.

References and citations are in turquoise.

Contextual history is in purple.

This webpage about the valley of Farndale has the

following section headings:

- The

Farndales who lived in Farndale

- The

Geography of Farndale

- Farndale,

an Overview

- Kirkbymoorside

- Farndale

before the Norman Conquest

- The

Feudal Era and Farndale

- Farndale

since 1500

- Farndale

Timeline

- The

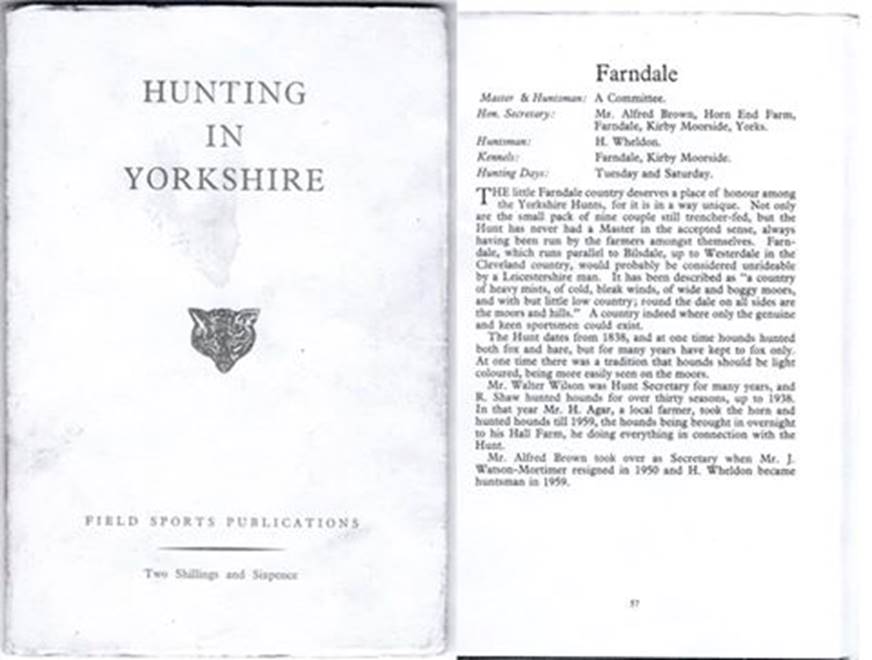

Farndale Hunt

- Wordsworth’s

Farndale

- A

photographic journey of Farndale

The Farndales who lived in Farndale

Our early ancestors were the inhabitants

of Farndale by about 1230. We know of

some of those who lived in Farndale in medieval times (see FAR00001 and

FAR00002).

We know a little of the forest of Farndale (FAR00003

and FAR00004). Edmund

the hermit was of course not our ancestors and indeed until the mid thirteenth century, the area was forested hunting

grounds, with grants given to monks as a source of timber, and with little

evidence of habitation. But there is evidence in the mid thirteenth century of

a campaign of cutting back the land for cultivation and renting it to villeins.

It is the poor peasant folk of Farndale who are probably our earliest ancestors

- perhaps William the Smith of Farndale, 1240 (FAR00009),

John the Shepherd of Farndale, 1250 (FAR00010),

Roger milne (miller) of Farndale, 1265 (FAR00013A)

and Simon the miller of Farndale, 1282 (FAR00021)

were our early ancestors living in Farndale.

Over time, folk started to adopt names

which described them by place or occupation. Examples are Nicholas de Farndale,

the first personal name linked to Farndale (see FAR000006

and Farndale 1), Peter de

Farndale (see FAR000008

and Farndale 2), Gilbert de

Farndale (FAR00018

and Farndale 3), and Simon de

Farndale (FAR00021

and Farndale 4). So our ancestors started to called themselves de Farndale,

and in time just used the Farndale name. That process signalled the start of a

spread of our ancestors out of Farndale to the surrounding lands. At that time,

such movements were no doubt as bold and significant as later emigrations to

Australia, Canada and New Zealand. We know for instance

that De Johanne de Farndale, 1275 (FAR00014) moved

further afield to Egton.

In this genealogical exploration of the

Farndale family, we are therefore most interested in Farndale the place before

about 1400. After that, those who chose to define themselves as ‘of Farndale’

were those who had moved on to live in other places. By the fifteenth century

there were no members of the family still living in Farndale, and none have

returned.

Nevertheless an exploration of the earliest history

of Farndale the place is integral to the family story. It is our beginnings. It

is the cradle of the Farndale family. It is where it all started.

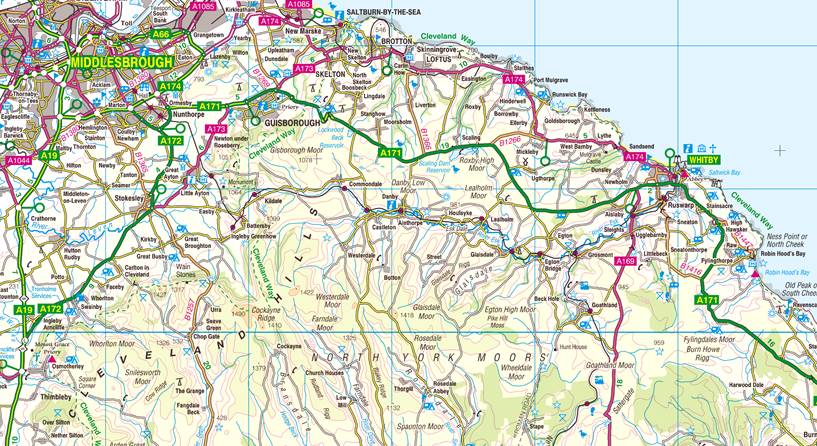

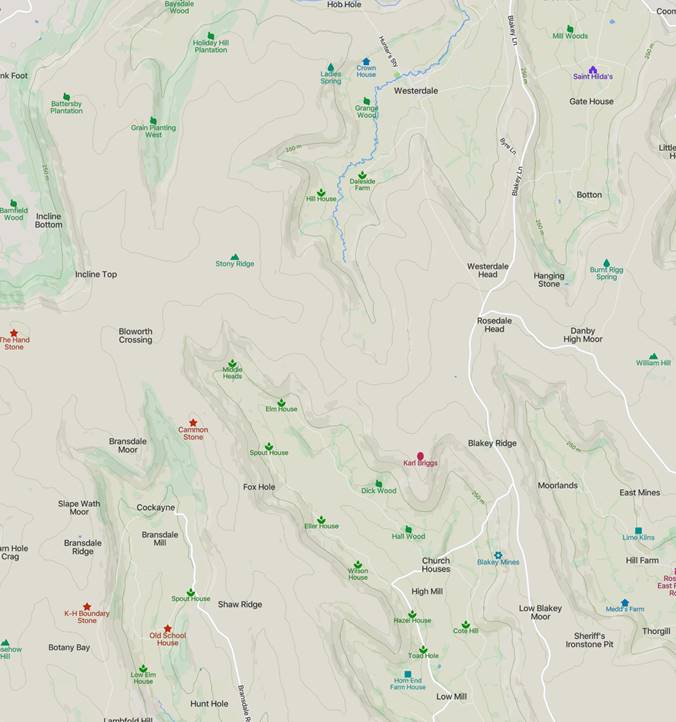

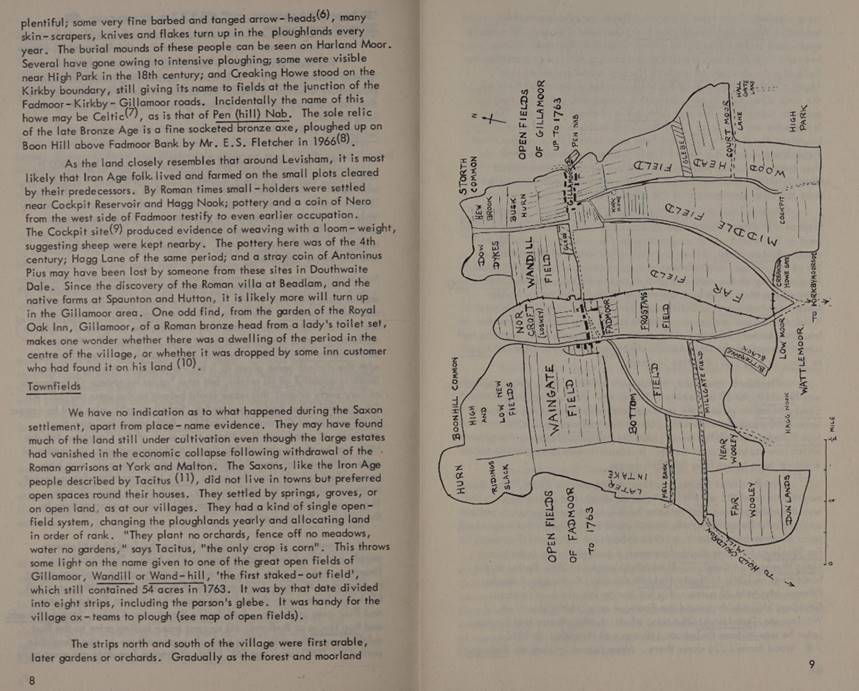

The Geography of Farndale

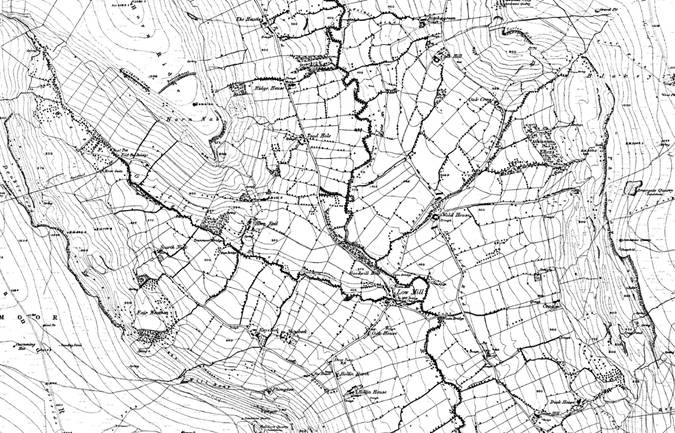

Farndale location

Farndale 2023

Farndale 1857

Farndale, an Overview

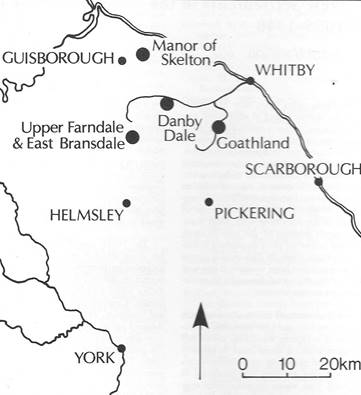

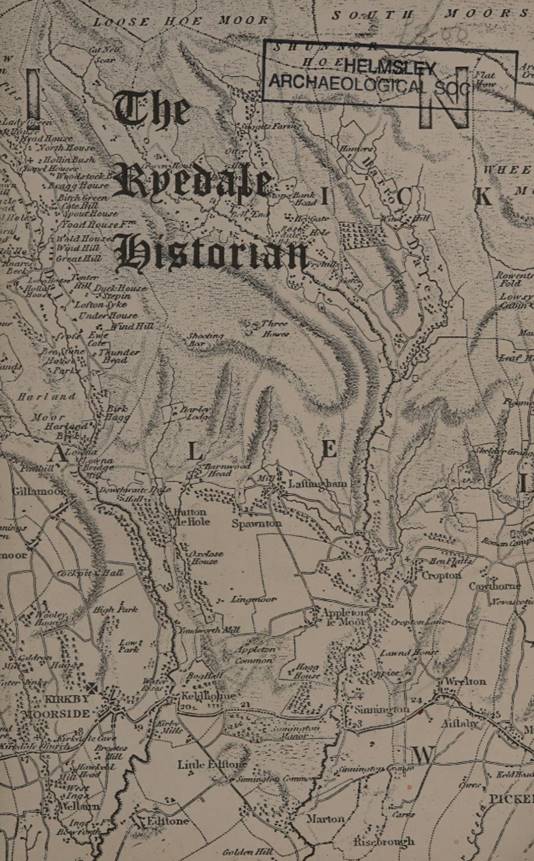

Farndale is a valley located

in the North York Moors National Park in North Yorkshire. The nearest town is

Kirkbymoorside located five miles to the south. Pickering is thirteen miles to

the south-east and Helmsley twelve miles to the south-west.

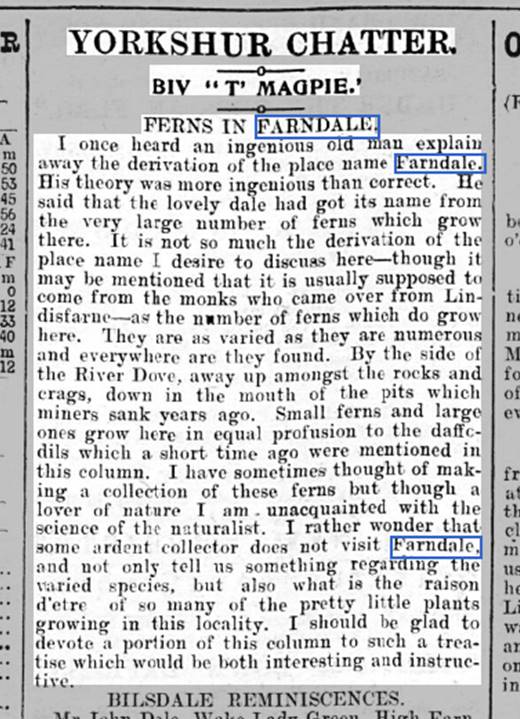

Farndale

was first recorded as Farnedale, and means Fern Valley. It has sometimes been interpreted

as a derivation of the Gaelic word fearna meaning

alder, since the alder tree is still common in the dale. Farndale’s river, the

Dove, probably originates in the Celtic word dubo,

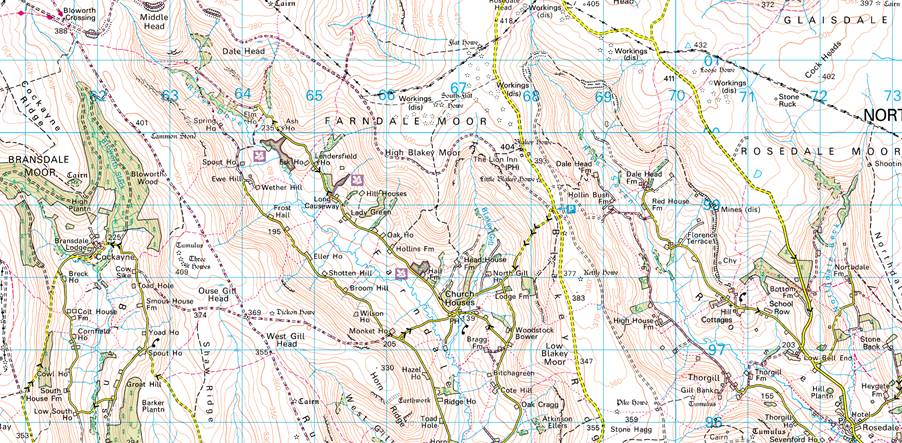

the black or shady stream. High up on the west side of the valley is a large

boulder, known as the Duffin Stone. This stone might identify one of the two

original forest clearings, named Duvaneesthaut

in the Rievaulx Abbey charter of 1154.

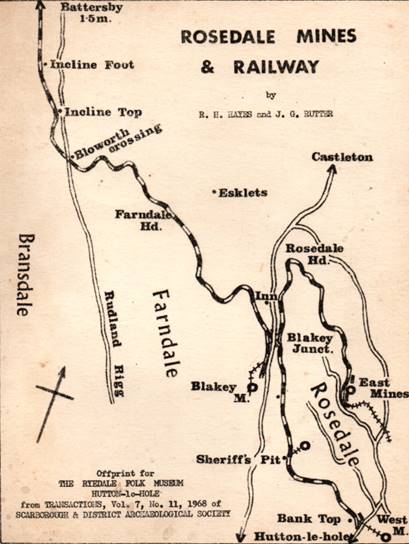

Farndale is surrounded by

some of the wildest moorland in England, and is

sandwiched between Bransdale and Rosedale. To the north-east sits Blakey Ridge

at over 400 m above sea level, and to the north-west, Cockayne Ridge reaching

up to 454 m above sea level is one of the highest points of the North York

Moors. Around the north of Farndale, between Bloworth

Crossing and Blakey is the track bed of the old Rosedale Ironstone Railway

(Rosedale Branch) which forms part of two Long Distance Footpaths these being

Wainwright's Coast to Coast Walk and The Lyke Wake Walk.

Farndale is a scattered agricultural community

with traditional Yorkshire dry stone walls. The valley is popular with walkers

due to its famous wild daffodils, which can be seen around Easter time all

along the banks of the River Dove. To protect the daffodils the majority of

Farndale north of Lowna was created a Local Nature

Reserve in 1955.

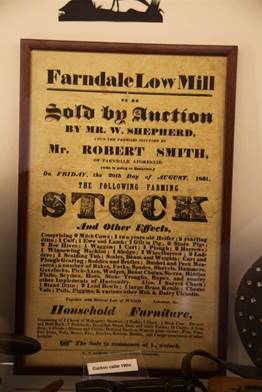

Farndale is home to two hamlets. Church Houses is

at the top of the valley and Low Mill further down. Low Mill is at the heart of

the daffodil walking routes.

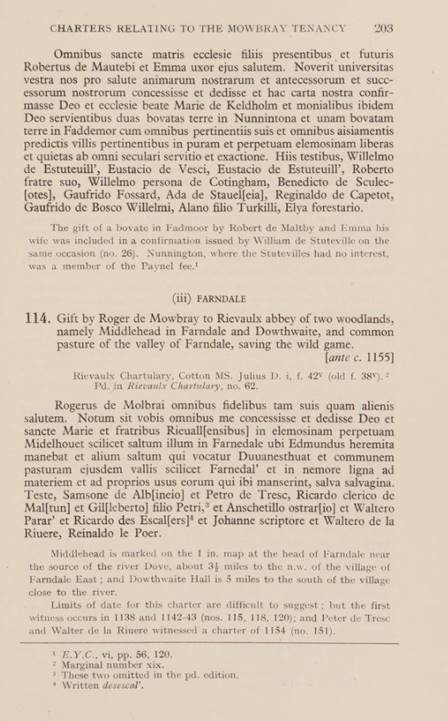

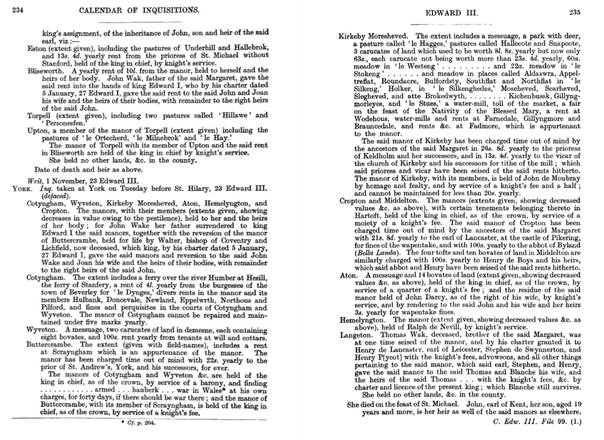

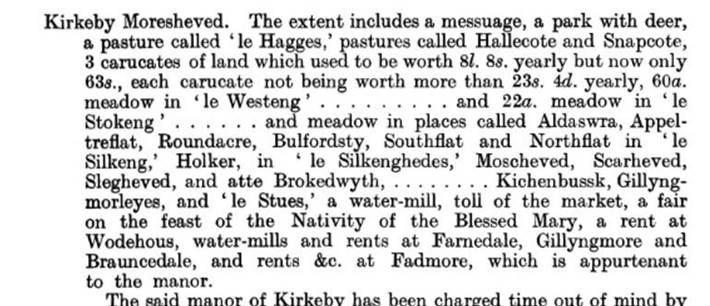

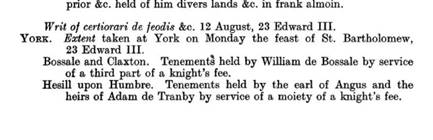

Kirkbymoorside

Kirkbymoorside lies only 25

miles north of York.

The name Kirkbymoorside

suggests one of the key reasons for the settlement’s establishment, that being

the shelter offered by the southern slopes of the moors into which the town

nestles. Our prehistoric ancestors left behind flint and stone axes, and traces

of their Celtic language in the street names of Tinley Garth (garden) and Howe

End (a ’howe’ being a burial mound). Anglo-Saxon and Viking artefacts include a

silver coin dating from around 790, found within the grounds of the parish

church of All Saints.

There is some disagreement

over the spelling of the village: the alternative is Kirbymoorside,

which is how the railway companies spelt the name on the station, as how it is

traditionally pronounced). Signposts read "Kirkbymoorside".

"Kirk" means church and "-by" is the Viking word for

settlement, so that the name translates as "settlement with a church by

the moorside", or as Ekwall argues, Moorside is

"Moresheved" which means "top of the

moor".[5] A valley near the town is known as Kirkdale.

Kirkbymoorside is noted as Chirchebi

in the Domesday Book of 1086. With William the Conqueror came the ’Harrying of

the North’; Saxon landowners gave way to his supporters and in Kirkbymoorside Torbrant was replaced by Hugh Fitzbaldric

and then Robert de Stuteville. The Stuteville family built a moated wooden

castle on Vivers Hill behind the church with

commanding views of the town and beyond. The town grew in importance and

prospered under the Wake family to whom it passed in the 13th Century and in

1254 the Wednesday Market, which still thrives today, was established along

with an annual fair.

Torbrand, the Anglo-Saxon owner, was

"evicted" by the Conqueror, and his home and lands given to Robert D'Estoteville or Stuteville, a Norman who had accompanied

the Conqueror to England. The family rose high in the royal favour,

and figured largely in the annals of Norman England. The De Mowbrays appear to have become possessed, in some way or other, of a

portion of the lordship, and Henry I. deprived both Roger de Mowbray and Roger

de Stuteville of their lands here for rebellion, and bestowed them on Nigel de

Albini, who married the heiress of the Mowbrays, and assumed that name. Shortly

afterwards a dispute arose between the families as to the right of possession,

and the king (Henry II.) restored the barony of Kirbymoorside

to the Stutevilles. It remained with this family till Joan, the daughter and

heiress of Nicholas Estoteville, conveyed it in

marriage to Hugh de Wake.

The Norman baron Robert de

Stuteville built a wooden moated castle on Vivers

Hill.

It has served as a trading

hub at least since 1254, when it became a market town.

The estate passed to the

Wake family in the 13th century, who brought prosperity to the town. However,

it was badly hit by the Black Death of the mid-14th century, after which the

wooden castle lay in ruins. In the 14th century the Black Death hit Kirkbymoorside

and soon the wooden castle was in decay and a loss of order within the town

followed.

Prosperity returned after

1408, when the Neville family took over, although little remains of the

fortified manor they built to the north of the town. The Nevilles remained

Catholic and took part in the Rising of the North of 1569.

Farndale Before the

Norman Conquest

According to

Bede, the Angles came from Ageln in the Jutland

peninsula of Denmark. Archaeological evidence is sparse for the earliest phase

of their settlement in this area.

After the

Angles were converted to Christianity, they left more substantial evidence.

Christianity came to Yorkshire not through the establishment route from Rome

via Canterbury, but from the north and ultimately from the west. Monasteries

were established on sites resembling Lindisfarne, which offered qualities of

remoteness but also access to settlements. Lindisfarne as well as sites such as

Iona in Scotland, were near to navigational routes which were then primarily by

sea.

Whitby was

founded by Aidan himself and Hilda was its most famous abbess. Another cell was

later established in Forge Valley near Scarborough. The founding of an early

monastery at Lastingham is vividly described by Bede. Closer to Farndale, the

little church of St Gregory at Kirkdale near Kirbymoorside

is secluded, lying across the narrow valley.

This part of

Yorkshire saw two Viking settlements, both fairly peaceful,

with no evidence of armed conquest except for the taking of York, the political

centre and market of the area. York fell to the Danes in 867. The extent and

range of settlement isn’t clear. In the early tenth century came a second wave

of Scandinavian speakers, with Norwegian tongues into northern Yorkshire from

Cumberland.

The place

names of the pre Norman countryside provide glimpses

of pastures, valleys, marshes, farms. The sculpture and churches in the tenth

and eleventh centuries hint at a growth of population around the edges of the

moorland and on the lowlands and the coast. Monuments suggest a framework of

parishes along the tabular hills stretching into the low ground.

Northwards from the Wolds, the windswept

moors of Hambleton and Cleveland remain as they have been throughout

pre-historic times, a refuge of broken peoples, a home of lost cultural causes.

Bede described the area as ‘vel bestiae commorari vel hommines bestialiter

vivere conserverant.’ (‘a land fit only for

wild beasts, and men who live like wild beasts.’). Although there are many

pre-historic remains on the North Yorkshire moors, the wooded valleys were very

remote and isolated. The Romans built roads around it and the Vikings skirted

it also. When the Romans left and the Saxons and Vikings arrived, some people

did move into the dales and left their burial mounds and crosses across the

moors. Thus the people who today come from the ‘dales

on the moors’ of North Yorkshire have remained a particular folk for several

hundred years and developed very special characteristics. In many respects they

remain to this day a unique Yorkshire Tribe. (Early

man in North East Yorkshire, 1930 p 219-20 by F Elgee)

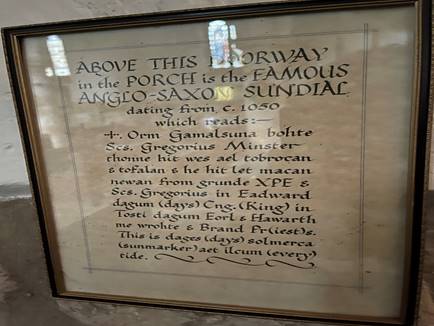

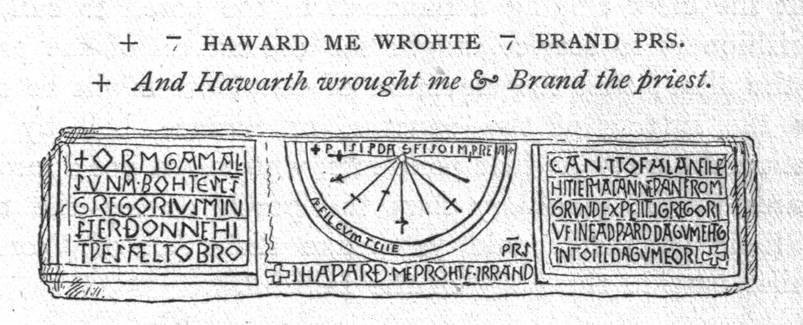

Within the porch of

the Saxon Church of St Gregory at Kirkdale, about a mile west of

Kirkbymoorside, above the entrance door is housed a Saxon sundial. It bears the

inscription “Orm the son of Gamel acquired St Gregory’s Church when it was

completely ruined and collapsed, and he had it built anew from the ground to

Christ and to St Gregory in the days of King Edward and in the days of Earl

Tostig”. The inscription refers to Edward the Confessor and to Tostig, the

son of Earl Godwin of Wessex and brother of Harold II, the last Anglo Saxon

King of England. Tostig was the Earl of Northumbria between 1055 and 1065. It

was therefore during that last peaceful decade, immediately before the Norman

conquest, that Orm, son of Gamel rebuilt St Gregory’s Church.

Orm

was prominent in Northumbria in the middle years of the eleventh century. He

married into the leading aristocratic clan of the region. His wife Aethelthryth

was the daughter of Ealdred, Earl of Northumbria in the mid eleventh century.

His brother in law was Siward, Earl of Northumbria

until 1055, famous for his exploits against Macbeth, the King of Scots. Orm’s

name suggests that he was of Scandinavian descent, but by his lifetime, he was

very much a Christian, and a part of the Saxon world.

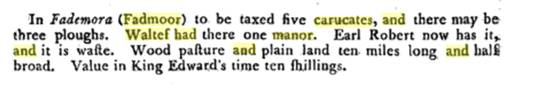

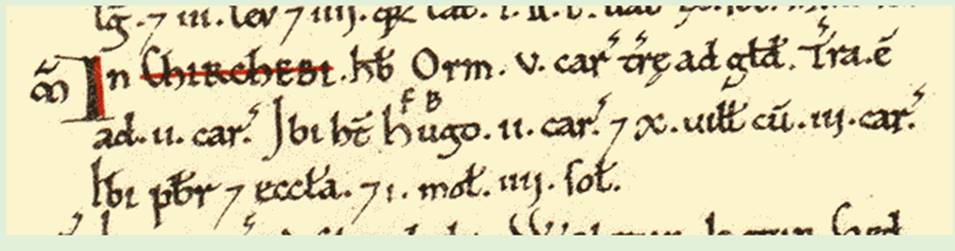

Chirchebi is known to us today as Kirkbymoorside. The Domesday Book

recorded that Chirchebi comprised five carucates of land. A carucate was

a medieval land unit based on the land which eight oxen could till in a year.

So presumably this area of land described the five carucates of cultivated land

around Kirkdale. [I need to do a bit more work on Saxon Chirchebi to

confirm this]. Before the Conquest, civilised Chirchebi was in

the possession of Orm and it comprised ten villagers, one priest, two

ploughlands, two lord’s plough teams, three men’s plough teams, a mill and a

church.

However this area of civilisation was part of a much wider wild estate

which Chirchebi formed, which was said to be twelve leagues (about 42

miles) long by the time of the Normans.

Earl Waltef who had a manor and 5

carucates at Fadmoor which comprised three

ploughlands.

So whilst there was a small

community of folk living at Kirkdale, within this wider estate, the bulk of the

estate was deep forest, stretching up through the dales towards the highlands

of the North York Moors. This forest was probably largely impenetrable, and

certainly not settled. It may have been used for hunting. Centuries before, the

Venerable Bede had described this region as ‘a land fit only for wild beasts,

and men who live like wild beasts’.

Within this uninhabited

woodland, there lay a forested valley, which was then unknown, but which was

nestling quietly in those woods, the place which in time would become the

cradle of the modern Farndale family. The land which was to become Farndale was

little more than a possession, and a place which the owner himself did not

likely know, and which after the Conquest, would continue to be possessed,

transferred, perhaps sometimes hunted within, for another two centuries.

The Feudal Era and Farndale

Medieval Farndale and East

Bransdale

By 1086 the ownership of Chirchebu had passed to Hugh, son of Baldric. Count

Robert of Mortain held Fadmoor

and it was waste. Later it fell into the hands of Hugh

son of Baldric before passing first to Roger de Mowbray and later to William

and then Nicholas de Stuteville in 1200. (Domesday Book and Victoria

County History of Yorkshire).

From the Essay New

Settlements in the North Yorkshire Moors, 1086 to 1340 by Barry Harrison,

in Medieval Rural Settlement in North East England,

Architectural and Archaeological Society of Durham and Northumberland, Research

Report No 2, Edited by BE Vyner, 1990:

The North Yorks Moors was an

appropriate area for the study of medieval agriculture, since it appears to

have been largely empty of settlements in 1086.The only developed manor in the

moorlands proper was in the Esk Valley where a 12

carucate holding was located at Danby,

In

1086 the area which included the land which would become known in time as

Farndale, lay within the great multiple of Kirkbymoorside, said to be 12

leagues long and in the possession of Hugh FitzBaldric, a German archer who had

served William the Conqueror and became the Sheriff of the County of York in

1069.

The estate passed to the Stuteville family in 1086, when Hugh

died. The Stutevilles were deprived of it in 1106 when it was granted to Nigel d’Aubigny, one of Henry I’s ‘new men’.

On his death in 1129 his widow Gundreda

administered the estate on behalf of her under age

son, Roger de Mowbray. It was she who granted the whole of Welburn and Skiplam together with the western side of Bramsdale to Rievaulx Abbey who developed the whole area as

a series of granges and cotes, including Colt House and Stirk House in Brandsale. It was only to be expected that the monks would

seek to extend their properties into the Mowbray territory further east.

Therefore, at some time before 1155, Roger granted to the monks a wood in

Farndale called Midelhoved (the “Middle Heads”)

(Ordnance Survey Grid NZ 628018) and another wood called Duvanesthuart,

probably in the area of Duffin Stone Farm (Ordnance Survey NZ 645988), at the

north western end of the Dale, together with common pasture rights and

permission to take building timber and wood ‘for those who stay there’. Duvanesthuart embodies an Irish-Norse personal name, but

there is nothing to suggest that it was a functioning settlement by the mid

twelfth century. The whole area was regarded as a private forest of the

Mowbrays – the grant was made ‘saving Roger’s wild beasts’ (ie

reserving Roger’s right to hunt), and it seems to have anticipated that the

monks would want to build a new dwelling there probably for use as a grange or

cote.

The House Mowbray

Sir Roger de Mowbray (1120 to 1188) was an Anglo-Norman

nobleman. He had substantial English landholdings. A supporter of King Stephen,

with whom he was captured at Lincoln in 1141, he rebelled against Henry II. He

made multiple religious foundations in Yorkshire. He took part in the Second

Crusade and later returned to the Holy Land, where he was captured and died in

1187. Roger was the son of Nigel d'Aubigny by his

second wife, Gundreda de Gournay. On his father's

death in 1129 he became a ward of the crown. Based at Thirsk with his mother,

on reaching his majority in 1138, he took title to the lands awarded to his

father by Henry I both in Normandy including Montbray,

from which he would adopt his surname, as well as the substantial holdings in

Yorkshire and around Melton. Roger supported the Revolt of 1173–74 against

Henry II and fought with his sons, Nigel and Robert, but they were defeated at Kinardferry, Kirkby Malzeard and

Thirsk. Roger left for the Holy Land again in 1186, but encountered further misfortune

being captured at the Battle of Hattin in 1187. His ransom was met by the

Templars, but he died soon after and, according to some accounts, was buried at

Tyre in Palestine. There is, however, some controversy surrounding his death

and burial and final resting-place.

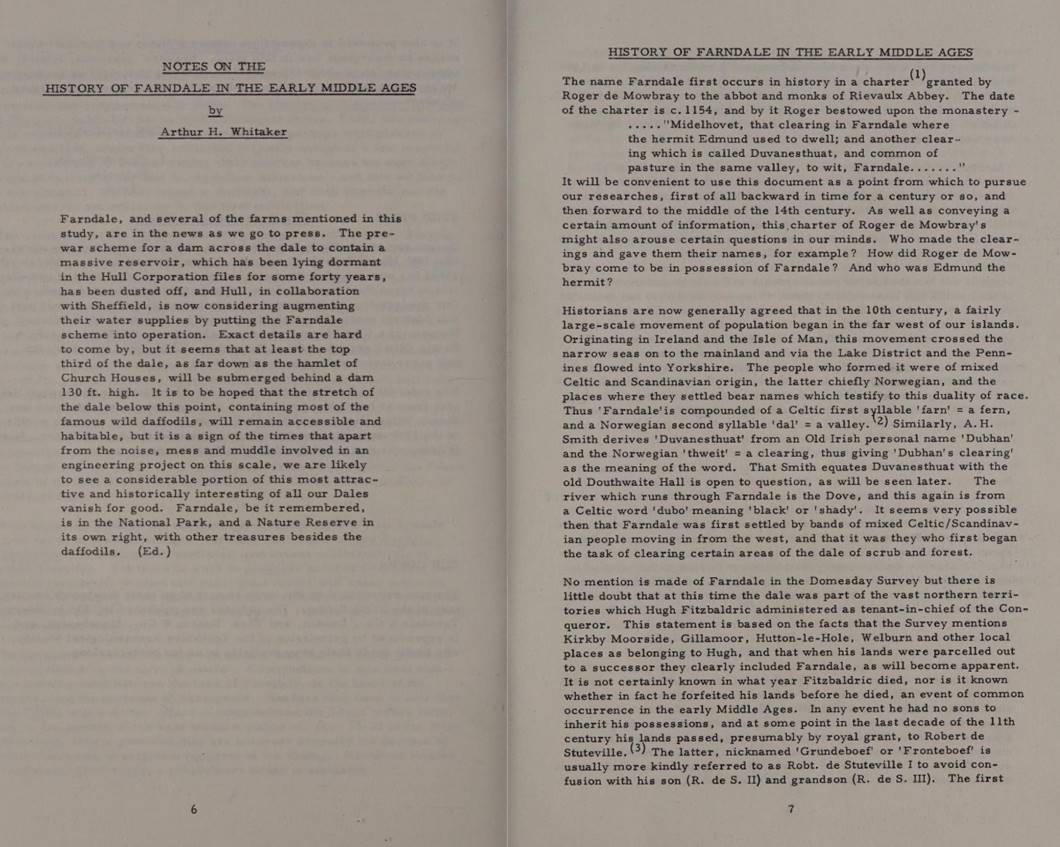

And so, in 1154, we are introduced to Farndale the place for the first time in

the Chartulary of Rievaulx Abbey when Gundreda, on behalf of her

guardian, gave land to the abbey.

“Gundreda, wife of Nigel de Albaneius, greetings to all the sons of St. Ecclesiff. Know that I have given and … confirmed, with the

consent of my son, Eogeri de Moubrai,

God and St. Marise Eievallis and the brothers there.

. . for the soul of my husband Nigel de Albaneius,

and for the safety of the soul of my son, Roger de Molbrai,

and of his wife, and of their children, and for the soul of my father and

mother, and of all my ancestors, whatever I had in my possession of cultivated

land in Skipenum, and, where the cultivated land

falls towards the north, whatever is in my fief and that of my son, Roger de Moubrai, in the forest and the plain, and the pastures and

the wastins, according to the divisions between Wellebruna and Wimbeltun, and as

divided from Wellebruna they tend to Thurkilesti, and so towards Cliveland,

namely Locum and Locumeslehit, and Wibbehahge and Langeran, and Brannesdala, and Middelhoved,

as they are divided between Wellebruna and Faddemor, and so towards Cliveland.”

Roger of Molbrai, to all the faithful,

both his own and strangers. Let it be known that I have granted

. . to the Rievallis brothers, in perpetual

alms, Midelhovet - scil. that meadow in Farnedale where Edmund the Hermit dwelt, and another meadow

called Duvanesthuat, and the common pasture of the

same valley - scil., Farnedale:

and in the forest wood for material, and for the own uses of those who remained

there, save the salvage. Witness Samson de Alb[aneia]; and Peter of Tresc; and Anschetillo Ostrario; and Walter

Parar; and Eicardo de Sescal

[or ? Desescal.]; and John the Scribe; and Walter de

la Eiviere; [and] Eiinaldo

le Poer.

And so, as we first lay our historical goggles onto Farndale the

place in 1154, we appear to enter a Lord of the Rings World, with a dash

of Game of Thrones. The House Mowbray (a competitor to the House

Stuteville) has given to the monks, who live in their exquisite Elven home at Rievaulx, a place called Midelhovet,

where Edmund the Hermit used to dwell, and another called Duvanesthuat,

together with the common pasture within the valley of Farndale.

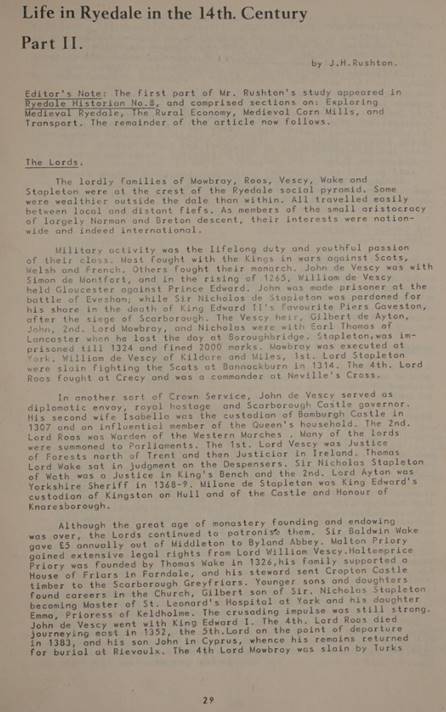

Rievaulx,

in its Elven valley, taken by the website author in 2016

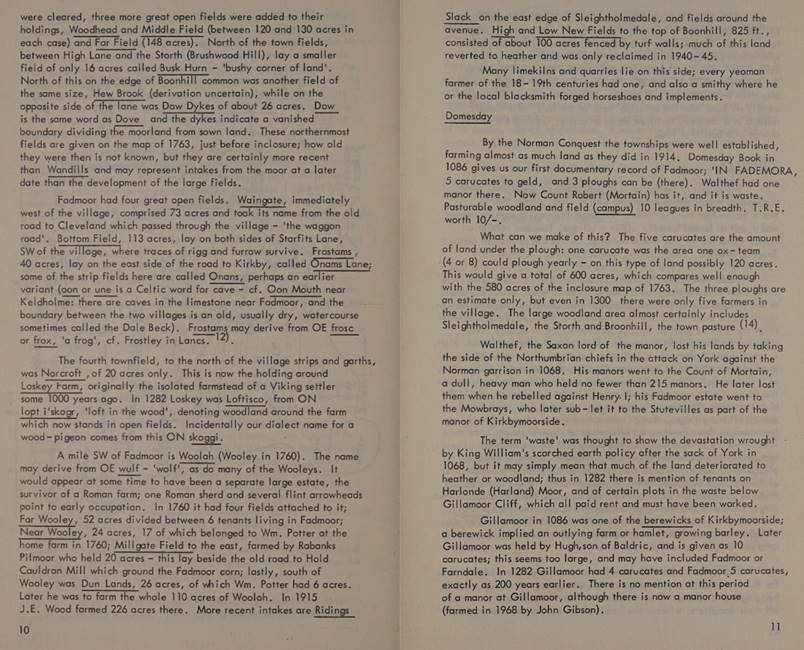

Midelhovet

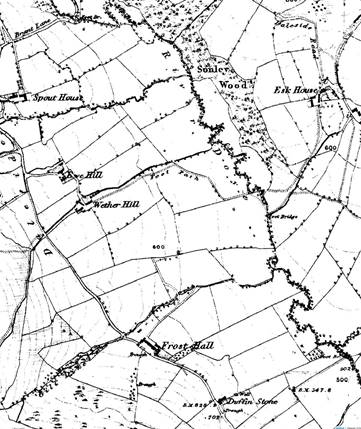

is almost certainly the area in Farndale known today as Middle Head and Duvanesthuat is probably the place where the Duffin Stone

lies today.

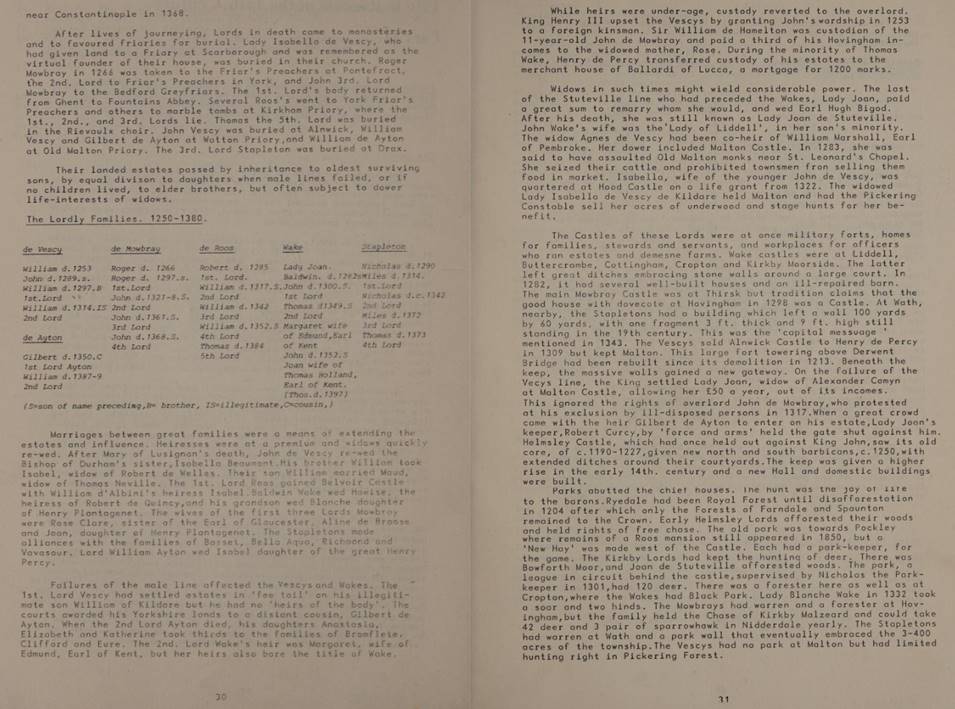

The

northwestern end of Farndale showing Middle Head and the Duffin Stone. The area of Middle Head in 2021

We

are also introduced to the first individual who roamed the lands of Farndale,

who used to live at Midelhovet some years prior to 1154. Edmund the hermit of

Farndale was a legendary figure who lived in a cave in the North York Moors in

the 12th century. He was said to be a holy man who performed miracles and

healed the sick. He was also reputed to have been a descendant of King Alfred

the Great and a cousin of King Stephen. I don’t suppose he was our ancestor,

since he was a hermit, but this is our first introduction to a character

roaming the place.

So by this time, the dale had become known as Farndale.

The name Farndale seems to come from the Celtic ‘farn, or fearn’ meaning ‘fern’

and the Norwegian ‘dalr’, meaning

‘dale;’ and so was the ‘dale where the ferns grew.’ There are historical

accounts which have suggested that the first people to settle in Farndale were

bands of mixed Celtic and Scandinavian stock and that it was they who began to

clear areas in which to build and grow crops. I still need to review the

historical evidence to see if there is evidence of such. We have no records of

them until the 13th Century. Until I see evidence otherwise, I think that

Farndale was likely uninhabited forest until the twelfth century, but this

needs more work to check the archaeological record of Farndale.

Of course whilst Farndale is today dominated by moorland bracken and ferns,

ferns are naturally a woodland plant, so it must have been the ferns of the

forested Farndale which gave rise to its name. Perhaps it was Edmund who must

have known the valley intricately, who first chose its name.

Unfortunately for the monks of

Rievaulx, the Stutevilles came back into favour with the accession of Henry II

and Roger de Mowbray was compelled to hand back Kirbymoorside,

along with many others fees. The Stutevilles favoured

the Benedictine monks of St Mary’s Abbey, York and their own small house of

nuns was founded at Keldholme near Kirbymoorside.

(Ordnance Survey NZ 710863).

The House Stuteville

The Stuteville came to the

region after the Norman Conquest in 1066. The Stuteville family lived in

Cumberland. Their name, however, is a reference to Estouteville-en-Caux,

Normandy, the family's place of residence prior to the Norman Conquest of

England in 1066. The surname Stuteville was first found in Cumberland where

they held a family seat as Lords of the Manor and Barons of Lydesdale

Castle on the western borders of England and Scotland. This ancient family were

derived d'Estouteville-en-Caux in Normandy where the

family held the Castle Ambriers and Robert d'Estouteville was Governor of the Castle 11 years prior to

the Battle of Hastings, in 1055, and defended it against the Count of Anjou.

Robert III de Stuteville

(who died in 1186) was an English baron and justiciar. He was son of Robert II

de Stuteville (from Estouteville in Normandy), one of

the northern barons who commanded the English at the battle of the Standard in

August 1138. His grandfather, Robert Grundebeof, had

supported Robert of Normandy at the battle of Tinchebray

in 1106, where he was taken captive and kept in prison for the rest of his

life.

Robert III de Stuteville

was witness to a charter of Henry II of England on 8 January 1158 at

Newcastle-on-Tyne. He was a justice itinerant in the counties of Cumberland and

Northumberland in 1170–1171, and High Sheriff of Yorkshire from Easter 1170 to

Easter 1175. The king's Knaresborough Castle and Appleby Castle were in his

custody in April 1174, when they were captured by David of Scotland, Earl of

Huntingdon. Stuteville, with his brothers and sons, was active in support of

the king during the war of 1174, and he took a prominent part in the capture of

William the Lion at Alnwick on 13 July (Rog. Hov. ii.

60). He was one of the witnesses to the Spanish award on 16 March 1177, and

from 1174 to 1181 was constantly in attendance on the king, both in England and

abroad. He seems to have died in the early part of 1186.

He claimed the barony,

which had been forfeited by his grandfather, from Roger de Mowbray, who by

way of compromise gave him Kirby Moorside. He is the probable founder of

the nunneries of Keldholme and Rosedale, Yorkshire, and was a benefactor of

Rievaulx Abbey.

Rievaulx Abbey was unable to

sustain its claim to the Farndale property and a little before 1166, Robert de

Stuteville granted Keldholme Priory timber and wood in Farndale together with a

vaccary, pasture and cultivated land in East Bransdale.

This implies that there was

some earlier settlement in the area, but not very much. The Keldholme property

in Bransdale, which could still be identified in a survey of 1610, never

amounted to more than 40 or 50 acres at Cockayne at the head of the valley.

The next mention of

Farndale, also Farendale, Farendal,

Farnedale in the thirteenth century, is found

at the beginning of the 13th century (Cal. Rot. Chart. 1199–1216 (Rec. Com.), 86). It formed part of the fee

of the lords of Kirkbymoorside, of which manor it was parcel.

For an extent in 1281–2 see

Yorks. Inq. (Yorks. Arch. Soc.), i, 249.

Robert de Stuteville had

given the nuns of Keldholme the right of getting wood for burning and building

in Farndale, (Cal.

Rot. Chart. 1199–1216 (Rec. Com.), 86) and in or about 1209 the Abbot of St. Mary's obtained from King

John rights in the forest of Farndale which the king had recovered from

Nicholas de Stuteville. (Pipe R. 11 John, m. 11) The abbot and Nicholas came to an agreement concerning common of

wood and pasture here, this being renewed in 1233. (Feet of F. Yorks. 17 Hen.

III, no. 14).

At about the same time

Robert gave to St Mary’s Abbey, who held the nearby manor of Spaunton, as much

timber and wood as they required together with pasture and pannage of pigs in

Farndale. The contemporaneous documents suggest that Farndale was regarded

primarily as a resource for timber and pasture in the mid twelfth century, with

little evidence of settlement.

In the mid thirteenth

century, Lady Joan de Stuteville successfully prosecuted the Abbot of St Mary’s

York, for exceeding his rights taking wood from Farndale by actually

assarting 100 acres of land. Only a few years later, the Inquisition Post Mortem taken after Joan’s death in 1276 reveals settlement on a grand

scale.

Joan de Stuteville,

heiress of Cottingham (incl. the honors of Liddel and

Rosedale), also known as "Joan de Wake", was born in 1216, the

daughter of Nicholas II de Stuteville.

Only a few years later, the Inquisition Post Mortem taken after Joan’s death in 1276, reveals settlement on a grand

scale. In Farndale, bond tenants holding by acres and paying a standard rent of

1-0d for each acre produced £27-5-0d, presumably for 545 acres. In East

Bransdale, bondmen held another 141 acres paying a standard rent of 6d per

acre, but they are said to hold ‘by cultures’. The

significance of these terms is explained in the IPM of Joan’s Son, Baldwin Wake, taken only six years later in 1282,

where the bondmen are said to hold their land ‘not by the bovate of land, but by more or less’. Thus standard

bovate holdings, usually in the lowlands and in some of the older settled

moorland villas, have been dispensed with in favour of holdings of varied size

rented by the acre.

The 1282 extent shows a

considerable increase over that of 1276, but this probably means nothing more

than that a new and up-to-date survey was used as the basis for the later

document. The Farndale rents now amounted £ 38-8-8d together with a nut-rent and

a few boon works and if the rate of 1s 0d per acre still applied, this would

give a total acreage held in bondage of no less than 768 acres. In

Bransdale rents were up to £4-14-3d which would give us about 188 acres at the

old rent of 6d per acre. For the first time the number of bondmen are given - 25 in East Bransdale and 90 in Farndale.

Assarting is the act of

clearing forested lands for use in agriculture or other purposes. In English

land law, it was illegal to assart any part of a

royal forest without permission. This was the greatest trespass that could be

committed in a forest, being more than a waste: while waste of the forest

involves felling trees and shrubs, which can regrow, assarting involves

completely uprooting all trees—the total extirpation of the forested area. The

term assart was also used for a parcel of land

assarted. Assart rents were those paid to the British

Crown for the forest lands assarted. The etymology is from the French word essarter meaning to remove or grub out woodland. In

northern England this is referred to as ridding.

In the Middle Ages, the

land cleared was usually common land but after assarting, the space became

privately used. The process took several forms. Usually

it was done by one farmer who hacked out a clearing from the woodland, leaving

a hedged field. However, sometimes groups of individuals or even entire

villages did the work and the results were divided

into strips and shared among tenant farmers. Monastic communities, particularly

the Cistercians, sometimes assarted, as well as local lords. The cleared land

often leaves behind an assart hedge, which often

contains a high number of woodland trees such as small leafed

lime or wild service and contains trees that rarely colonise planted hedges,

such as hazel.

Assarting has existed

since Mesolithic times and often it relieved population pressures. During the

13th century, assarting was very active, but decreased with environmental and

economic challenges in the 14th century. The Black Death in the late 1340s depopulated

the countryside and many formerly assarted areas returned to woodland.

Assarting was described by

landscape historian Richard Muir as typically being "like bites from an

apple" as it was usually done on a small scale

but large areas were sometimes cleared. Occasionally, people specialized in

assarting and acquired the surname or family name of 'Sart'.

Field names in Britain

sometimes retain their origin in assarting or colonisation by their names such

as: 'Stocks'; 'Stubbings'; 'Stubs'; 'Assart'; 'Sart'; 'Ridding'; 'Royd'; 'Brake'; 'Breach'; or 'Hay'.

The

sheer scale is impressive enough, but there are features which point to a

planned campaign of settlement. It is difficult to imagine how men of

villain status, compelled to pay rents of 1s 0d per acre for minute holdings of

marginal land, could also have managed to undertake their own assarting. It

seems more likely that the land had been reclaimed in advance of letting, as at

Goathland, by the Lord’s agents, while the standard rents suggest a single

campaign on a large scale rather than piece meal assaulting. A number of key questions cannot be answered from the sources we have used so

far. It is not clear whether settlement of the two Dales completed by 1282.

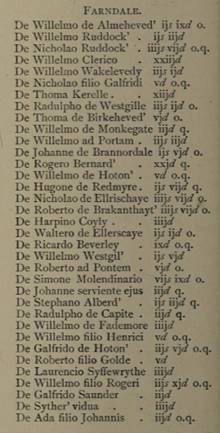

The Lay

Subsidy Assessments of 1301 give us a brief glimpse of the settlement pattern, listing

numerous contributors bearing the names of the farms which are still to be

found in Farndale, such as Wakelevedy (‘Wake Lady Green’), Westgille

(“West Gill”), Monkegate (Monket

House) and Ellershaye (“Eller House”), and which are

scattered all round the dale.

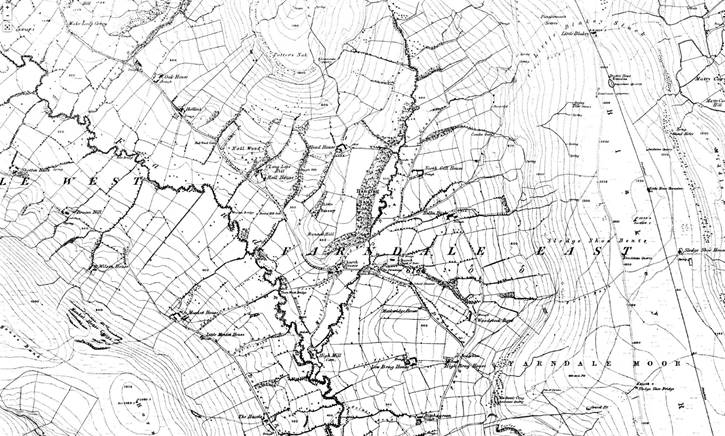

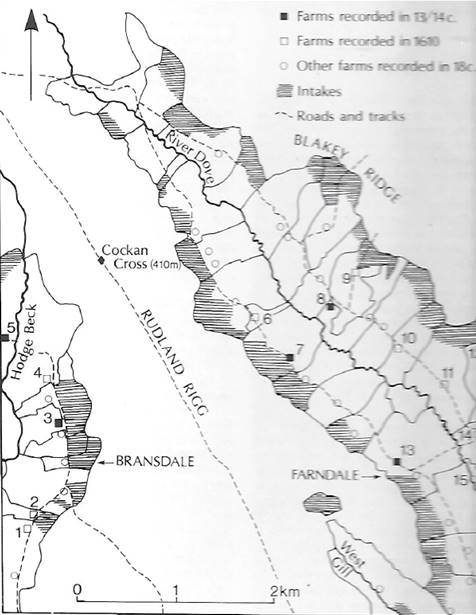

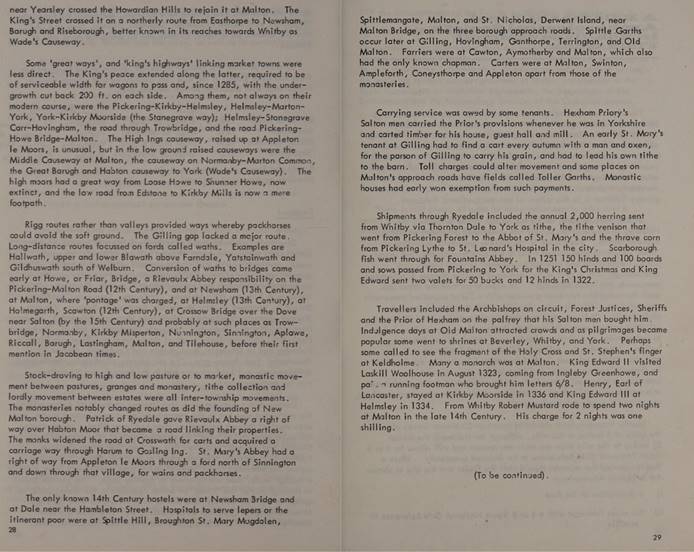

Medieval settlement in upper

Farndale and east Bransdale – the numbered farms are those which still bear

names mentioned in the sources up to 1610.

The 1570 document described 71 tenements in Farndale, 40 on the

east side and 31 on the west, together with two mills and a few cottages paying

altogether just over £54 in rent.

As the thirteenth century

Inquisitions Post Mortem make clear, the size of farms

was never uniform. Some farms must have fallen out of cultivation in the later middle ages and may have been combined with others, thus

effecting a considerable reduction in the overall number of tenements. Even so,

there was still remarkably little differentiation among the peasantry as late

as 1610. Farms of 10 to 15 acres producing rents of about as many shillings

were still very common. Only five tenants paid over £20 0d rent and only two

paid more than £25 0d.

Farndale since 1500

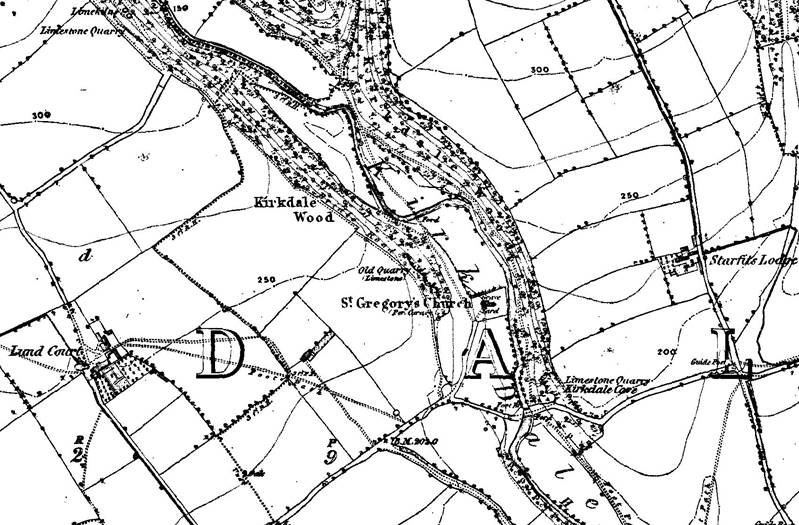

Kirkbymoorside, 1857

Kirkdale, 1857

1857

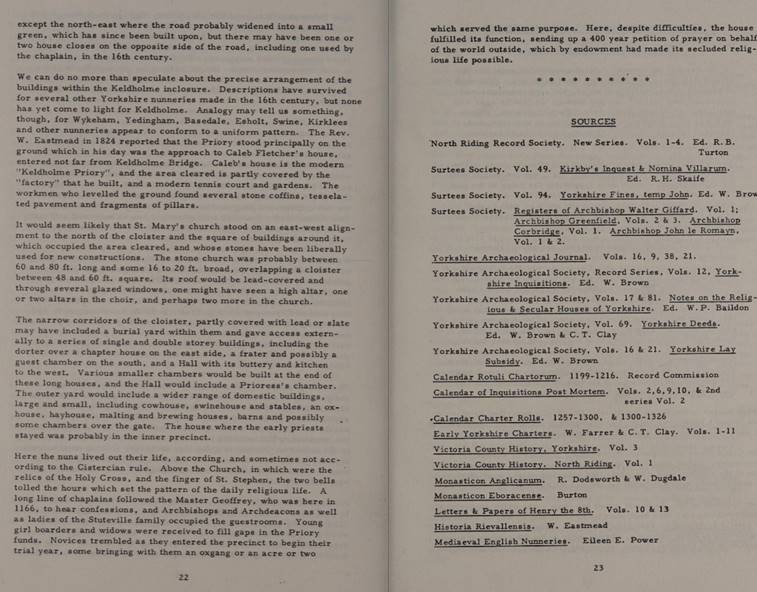

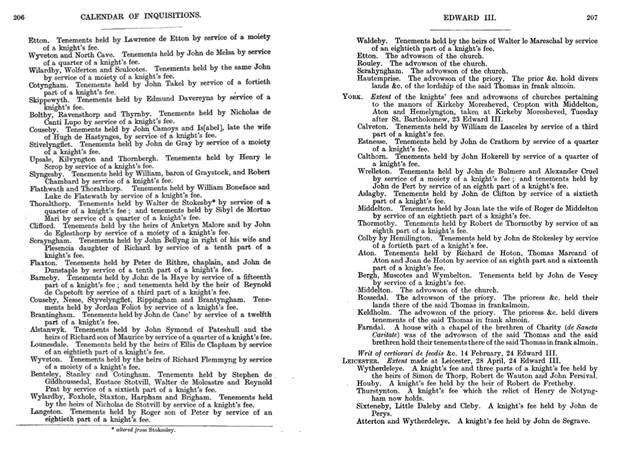

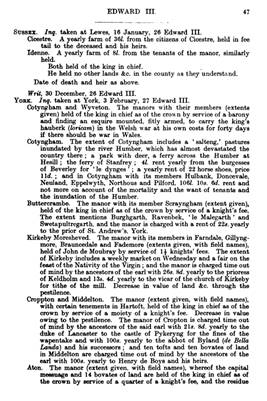

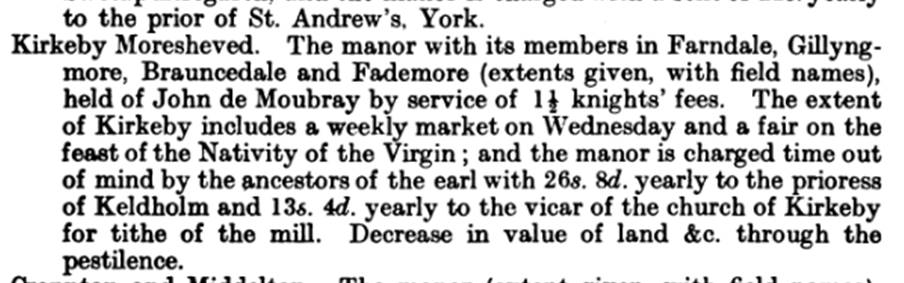

The Victoria County History –

Yorkshire, A History of the County of York North Riding: Volume 1 Parishes:

Kirkby Moorside, 1914:

Kirkby Moorside is a parish

covering about 13,700 acres, chiefly of moorland. It is practically enclosed

between two streams, the Dove and the Hodge Beck its tributary, which, flowing

down through Farndale and Bransdale respectively, unite to the south of the

town of Kirkby Moorside. The ground is thus well watered and fertile, on a

subsoil of inferior oolite with Upper and Lower Lias

in the dales. There are brick and tile works at Kirkby

Moorside and Cockayne, and jet, coal and limestone have been worked in

Bransdale and Farndale. About half the total area is in cultivation, the

chief crops raised being oats and barley. …

The townships of Bransdale Eastside and Farndale Low Quarter have only a few houses

scattered here and there among the hills. These with Bransdale Westside

from Kirkdale parish and the rest of Farndale from Lastingham were in 1873

formed into the modern parish of Bransdale-cum-Farndale. In the extreme north

of Bransdale, between two branches of the Hodge Beck, is the little hamlet of

Cockayne, with an old chapel of ease and a hall used by the Earl of Feversham as a shooting-lodge.

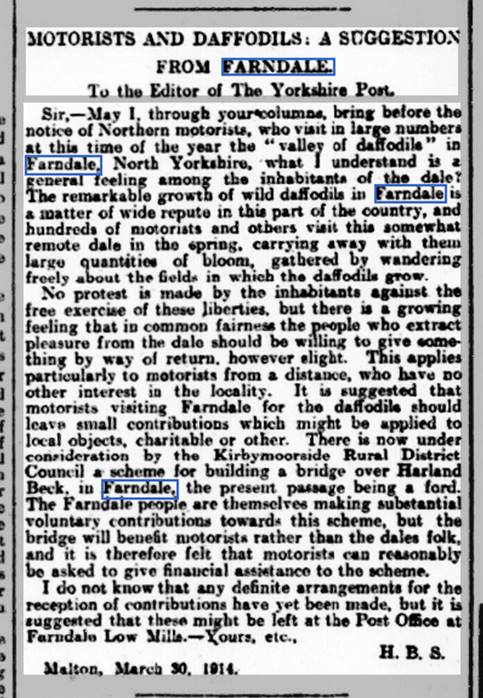

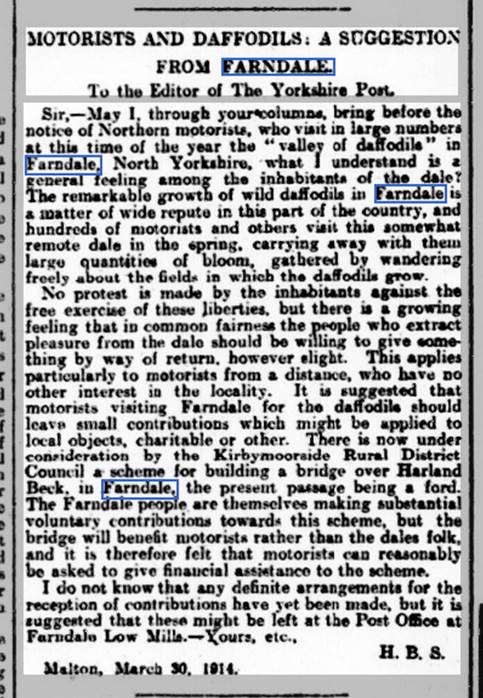

(Yorkshire Gazette, 4 April

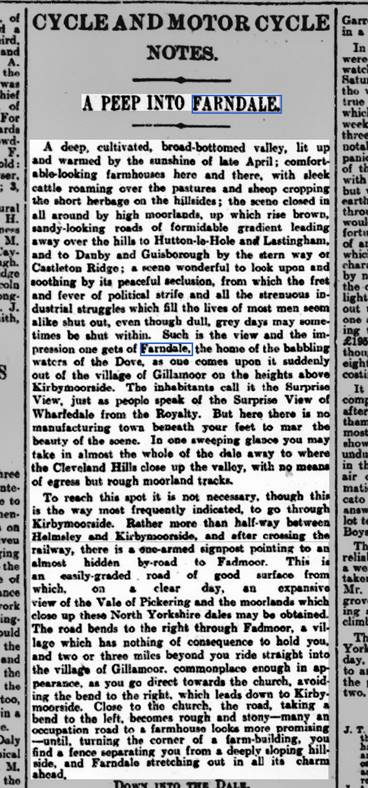

1903)

(Yorkshire Post and Leeds Intelligencer, 31 March 1914) (Yorkshire Post, 15

May 1914)

Farndale Timeline

Bede described the area where Farndale lay as ‘vel

bestiae commorari vel hommines bestialiter

vivere conserverant.’: ‘a land fit only for wild beasts,

and men who live like wild beasts.’.

1035

Orm Gamallson

of Kirkdale was the Lord of Chirchebi, later Kirkbymoorside, which

included the lands which would one day be called Farndale.

Both Orm and Gamel are

Scandinavian names, so Orm is likely to be descended from the Scandinavian

settlers of North Yorkshire. It is possible that he benefited from the handing

out of English Estates by King Canute (1016-1035).

The territory of King Cnut

Orm

was prominent in Northumbria in the middle years of the eleventh century. He

married into the leading aristocratic clan of the region. His wife Aethelthryth

was the daughter of Ealdred, Earl of Northumbria in the mid eleventh century.

His brother in law was Siward, Earl of

Northumbria until 1055, famous for his exploits against Macbeth, the King of

Scots.

On November 24, 1034,

Malcolm II died of natural causes. One month later, his son, Duncan MacCrinan, was elected king. For six uneasy years, Duncan

ruled Scotland with a thirst for power countermanded by his incompetence on the

battlefield. In 1038, Ealdred, earl of Northumbria, attacked southern Scotland,

but the effort was repelled and Duncan's chiefs

encouraged him to lead a counterattack. Duncan also wanted to invade the

Orkneys Islands to the north. Over the objections of all of

his advisers, he chose to do both. In 1040, Duncan opened up

two fronts. The attack on the Orkneys was led by his nephew, Moddan, and Duncan led a force toward Northumbria. Both

armies were soon routed and reformed only to be pursued by Thorfinn, mormaer of

Orkney. Macbeth joined Thorfinn and, together, they were victorious, killing Moddan. On August 14, 1040, Macbeth defeated Duncan's army,

killing him in the process. Later that month, Macbeth led his forces to Scone,

the Scottish capital, and, at age 35, he was crowned king of Scotland.

Siward, Orm’s brother in law, is perhaps most famous for his expedition in

1054 against Macbeth, King of Scotland, an expedition that cost Siward his

eldest son, Osbjorn. The origin of Siward's conflict

with the Scots is unclear. According to the Libellus

de Exordio, in 1039 or 1040, the Scottish king

Donnchad mac Crínáin had attacked northern

Northumbria and besieged Durham. Within a year, Macbeth had deposed and killed

Donnchad. The failed siege occurred a year before Siward attacked and killed

Earl Eadwulf of Bamburgh, and though no connection between the two events is

clear it is likely that they were linked.

The Annals of Lindisfarne

and Durham, written in the early 12th century, related under the year 1046 that

"Earl Siward with a great army came to Scotland, and expelled king

Macbeth, and appointed another; but after his departure Mac Bethad

recovered his kingdom". Historian William Kapelle thought that this

was a genuine event of the 1040s, related to the Annals of Tigernach entry for

1045 that reported a "battle between the Scots" which led to

the death of Crínán of Dunkeld, Donnchad's father;

Kapelle thought that Siward had tried to place Crínán's

son and Donnchad's brother Maldred on the Scottish throne. Another historian,

Alex Woolf, argued that the Annals of Lindisfarne and Durham entry was probably

referring to the invasion of Siward in 1054, but misplaced under 1046.

1055

“Orm the son of Gamel

acquired St Gregory’s Church when it was completely ruined and collapsed, and

he had it built anew from the ground to Christ and to St Gregory in the days of

King Edward and in the days of Earl Tostig”. (inscription on the Sundial at the Saxon Church of St Gregory) The inscription refers to Edward the Confessor and to Tostig,

the son of Earl Godwin of Wessex and brother of Harold II, the last Anglo Saxon

King of England. Tostig was the Earl of Northumbria between 1055 and 1065. It

was therefore during that last peaceful decade, immediately before the Norman

conquest, that Orm, son of Gamel rebuilt St Gregory’s Church at Kirkdale.

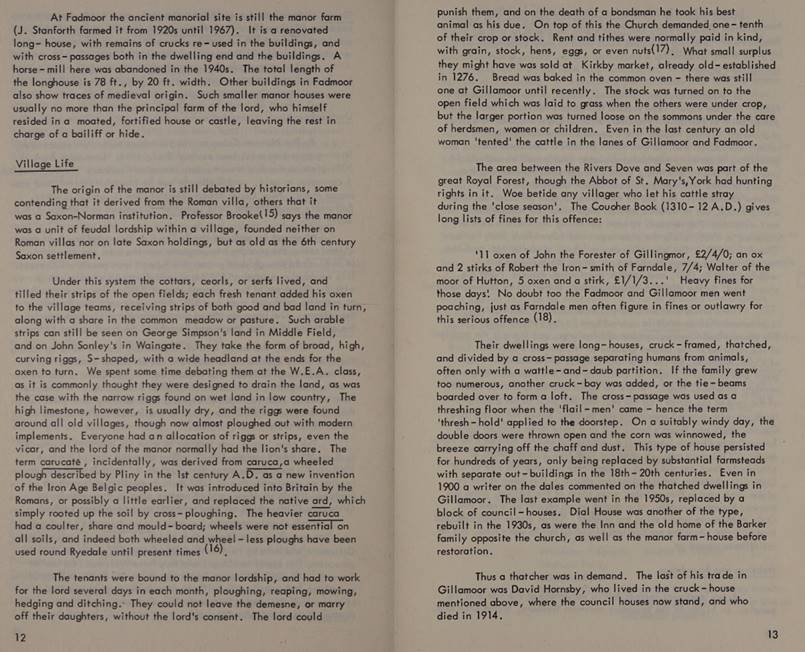

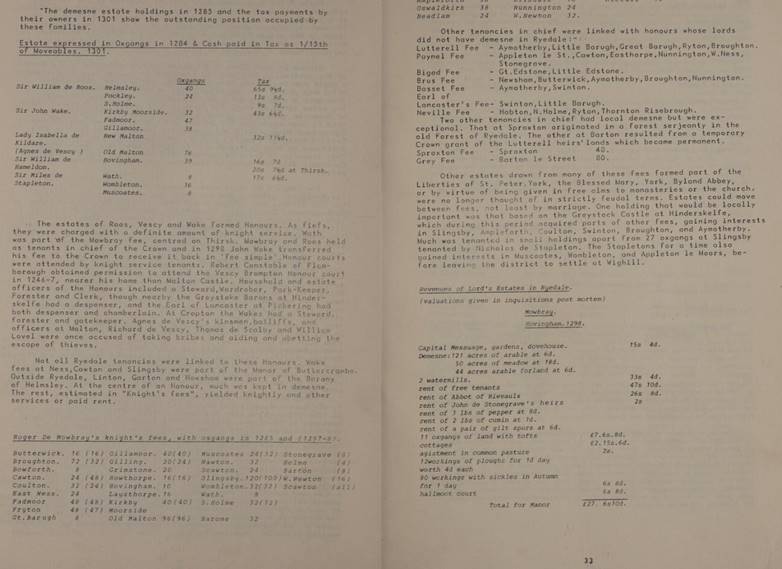

Kirkdale Church

Photos of the Church and

the sundial taken in 2021

The sundial at Kirkdale is one of a number of late Anglo Saxon sundials in the area. The Kirkdale sundial is

particularly intricate in its design and he best preserved as it was coated I plaster for many centuries prior to 1771 and was

protected by the porch.

The central panel contains the sundial and an Old English

inscription above it which reads “This is the day’s sun-marker at every hour”.

The left panel reads “Orm the son of Gamel acquired St Gregory’s Church when

it was completely ruined.” The right hand panel

reads “and collapsed, and he had it built anew from the ground to Christ and

to St Gregory in the days of King Edward and in the days of Earl Tostig”.

At the foot of the panel, a further inscription reads “Hawarth

made me, and Brad the priest”.

King Edward referred to in the panel is King Edward the Confessor,

1042 to 1066, who restored the Kingdom of Wessex to the English throne. He was

a deeply pious and religious man who presided over the rebuilding of

Westminster Abbey. He left much of the running of the country to Earl Godwin

and his son Harold. Edward died childless in 1066, 8 days after the completion

of Westminster Abbey. There was then a power struggle. Despite no bloodline,

Harold Godwinson was elected to be king by the witan (the high council of

nobles and religious leaders). William, Duke of Normandy claimed that Edward

had promised the throne to him. Harold defeated an invading Norwegian army at

the Battle of Stamford Bridge in Yorkshire, but then marched south to face

William of Normandy in Sussex and was killed at the Battle of Hastings. This

was the end of the Anglo Saxon kings and the beginning

of the Norman dynasty.

Tostig, the son of Earl Godwin of Wessex and brother of Harold

II, the last Anglo Saxon King of England was the Earl of Northumbria between

1055 and 1065. It was therefore in the course of that decade that Orm, son of Gamel rebuilt

St Gregory’s Church.

The surviving parts of Orm’s church adopt a style reflective of

the Romanesque architecture of the eleventh century mainland Europe and it is

possible that Orm may have travelled to Rome when Tostig made a pilgrimage

there in 1061.

Domesday Book recorded that Chirchebi comprised five

carucates of land. A carucate was a medieval land unit based on the land which

eight oxen could till in a year. So presumably this area of land described the

five carucates of cultivated land around Kirkdale. Before the Conquest,

civilised Chirchebi was in the possession of Orm and it comprised ten

villagers, one priest, two ploughlands, two lord’s plough teams, three men’s

plough teams, a mill and a church.

A carucate or carrucate

(Latin, carrūcāta or carūcāta) was a medieval unit of land area

approximating the land a plough team of eight oxen could till in a single

annual season.

However this area of civilisation was part of a much wider wild estate

which Chirchebi formed, which was said to be twelve leagues (about 42

miles) long by the time of the Normans.

Earl Waltef who had a manor and 5

carucates at Fadmoor which comprised three

ploughlands.

1066

By 1086 the ownership of Chirchebu

had passed to Hugh, son of Baldric. The landholdings of Orm

Gamallson of Kirkdale, were forfeited to Hugh fitzBaldric after the conquest.

Hugh Fitz Baldric

Hugh fitzBaldric

was a German archer in the service of William the Conqueror and was made

Sherrif of the County of York, replacing William Malet after his capture in

1069.

Hugh FitzBaldric

was born in about 1045 in Cottingham, Yorkshire (now part of Hull). He married

Emma de Lascelles in 1050. They had a daughter Erneburga Fitz Baldric (1075-?).

Hugh FitzBaldric

died in about 1086 in Cottingham, Yorkshire, aged about 41 years old.

Hugh first appeared in the

historical record around 1067 when he was the witness to a charter of Gerold de

Roumara. Hugh held the office of Sheriff of Yorkshire

from 1069 to around 1080, succeeding William Malet in that office.

When the land of the Saxon

earls was confiscated after the Norman Conquest, it would

appear that Orm’s property was acquired by, or granted to Ralph de

Mortimer; and Barch’s by Hugh FitzBaldric.

Ralph de Mortimer was the

only son of Roger, who derived his surname from Mortemer en

Lions in the Pays de Caux, between Neufchatel and Aumale in France. Ralph de Mortimer died in his castle of

St. Victor-en-Caux on 5

August 1100 (or 1104) and was buried in the Abbey church there. He left two

sons, Hugh and William; and a daughter, Hawise, who became the wife of Stephen,

Earl of Albemarle and Holderness. Hugh’s descendants became the Earls of March;

William died childless. The family seems to have no recorded connection with

Gilling, except for a later reference (in the 12th century) when

Peter de Ros, who was linked with the Mortimers by marriage, gave two carucates

of land to St. Mary’s Abbey, York. It is likely that this land so granted was

Orm’s, which had probably come into the Ros family by marriage. The Ros family

also had land of Ralph de Mortimer’s in Whenmore. In

the 12th century the land was in the possession of the Mowbrays and the

Stutevilles.

Barch’s portion was granted to Hugh FitzBaldric

(i.e. Hugh the son of Baldric). It is not known which Norman family he came

from, if indeed he was Norman. It has been stated that he was a German archer

in the service of William the Conqueror. However, before 1067 he “witnessed a

charter of Gerald, granting the Nuns of St. Amand in Rouen the church of his

fief of Roumare”. Immediately after the capture of

York by William in September 1069, Hugh FitzBaldric

appears to have been made Sheriff of the County of York by the King. He fell

into trouble by supporting Robert Duke of Normandy against William and

presumably lost his lands. However, nothing more is heard of him.' John

Marwood’s History of Gilling, Chapter 8: After the Saxons: The Ettons of Gilling.

Hugh had lands in

Yorkshire and Lincolnshire, and was listed in Domesday

Book as a tenant-in-chief. Hugh's tenure of the estate at Cottingham in

Yorkshire is considered to mean that he was a feudal baron. Katharine

Keats-Rohan states that Hugh lost his lands after the conclusion of Domesday

Book in 1086, likely for supporting Robert Curthose as king against William

Rufus after the death of William the Conqueror. But I. J. Sanders states that

Hugh's lands were divided after his death and does not mention any forfeiture

of the lands.

One of Hugh's holdings

included the village of Bossall in the hundred of Bulford (now in the Ryedale district of North

Yorkshire). In 1086, there were 19 residents and a priest, as well as a church,

in the small community. This property produced an annual income of "3

pounds in 1086; 2 pounds 10 shillings in 1066".

It is possible that the

Hugh fitz Baldric who witnessed a charter of Robert

Curthose's in 1089 is the same person as the former sheriff.

Domesday Book records that

Walter de Rivere and Guy of Croan were son-in-laws of

Hugh.

Hugh gave some of his

English lands to Préaux Abbey in Normandy and St

Mary's Abbey in York.

Hugh was memorialized in

the liber vitae of Thorney Abbey.

When the land of the Saxon

earls was confiscated [by the Normans] after the Conquest it

would appear that Orm’s property was acquired by, or granted to, Ralph

de Mortimer; and Barch’s by Hugh FitzBaldric.

... let us follow what

is known about Barch’s portion. As we have already

seen, it was granted to Hugh FitzBaldric (i.e. Hugh

the son of Baldric). It is not known which Norman family he came from, if

indeed he was Norman. It has been stated that he was a German archer in the

service of William the Conqueror. However, before 1067 he “witnessed a charter

of Gerald, granting the Nuns of St. Amand in Rouen the church of his fief of Roumare”. Immediately after the capture of York by William

in September 1069, Hugh FitzBaldric appears to have

been made Sheriff of the County of York by the King. He fell into trouble by

supporting Robert Duke of Normandy against William and presumably lost his

lands. However, nothing more is heard of him.

In

England Hugh son of Baldric was an important tenant-in-chief in Yorkshire, and

to a smaller extent in Lincolnshire; he also held two manors in

Nottinghamshire, single holdings in Wiltshire and Berkshire, and interests in

four holdings in Hampshire. In Yorkshire Hugh son of Baldric held about 50

manors with many berewicks and sokeland,

assessed at approximately 410 carucates. The greater part of these holdings

passed, presumably by royal grant, to Robert de Stuteville. 'The estates of

Hugh son of Baldric, Domesday lord of Cottingham, weredivided

after his death and the bulk of his lands in Yorkshire passedto

Robert I de Stuteville.' Ivor JohnSanders,

English Baronies: AStudy of Their Origins and Descent

1086-1327

Count Robert of Mortain held Fadmoor and it was waste. Later it fell into the hands of Hugh son of Baldric before passing first to Roger de Mowbray

and later to William and then Nicholas de Stuteville in 1200.

1086

The Kirkbymoorside estate passed to the Stuteville family (Robert

I de Stuteville) in 1086, when Hugh died.

There is more information

about the Domesday Book here.

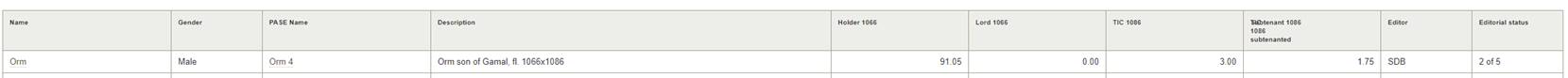

Orm (son of Gamal) is

associated with 61 places before the Conquest; 0 after

the Conquest.

Kirkby Moorside was

transferred to Hugh son of Baldric. It contained

Households: 10 villagers. 1 priest. Land and resources

Ploughland: 2 ploughlands. 2 lord's plough teams. 3 men's plough teams. Other

resources: 1 mill, value 4 shillings. 1 church. Tenant-in-chief in 1086: Hugh son of Baldric. Lord in 1086: Hugh son of Baldric. Lord in 1066: Orm (son of Gamal).

From the Essay New

Settlements in the North Yorkshire Moors, 1086 to 1340 by Barry Harrison,

in Medieval Rural Settlement in North East England, Architectural and

Archaeological Society of Durham and Northumberland, Research Report No 2,

Edited by BE Vyner, 1990: The North Yorks Moors was

an appropriate area for the study of medieval agriculture, since it appears to

have been largely empty of settlements in 1086.The only developed manor in the

moorlands proper was in the Esk Valley where a 12

carucate holding was located at Danby, Crumbeclive (Crunkley Hill in Glaisdale) and Lealholm.

This was an extensive area, said to measure seven leagues in length by three

leagues in width, within which Danby (six carucates) was the major focus of

settlement. The long valleys on the south side of the watershed appear to have

functioned mainly as resources for woodland and pastures for settlements in the

Vale of Pickering and although some settlements in the moors may have been

subsumed into consolidated Domesday entries for lowland manors, the

descriptions of moorland tracts granted to the new monasteries (Whitby,

Guisborough, Rievaulx and Byland) in the early and mid 12th

century contain very little evidence of functioning communities of any kind.

So we

start with a clear palate, to understand how agriculture developed after the

Norman Conquest.

1106

The Stutevilles were deprived of the Kirkbymoorside estate in 1106

when it was granted to Nigel d’Aubigny, one of Henry I’s ‘new men’.

Nigel d’Aubigny was one of Henry I’s “new men”. Nigel d'Aubigny

(Neel d'Aubigny or Nigel de Albini, died 1129), was a

Norman Lord and English baron who was the son of Roger d'Aubigny

and Amice or Avice de Mowbray. His paternal uncle William was lord of Aubigny,

while his father was an avid supporter of Henry I of England. His brother

William d'Aubigny Pincerna

was the king's Butler and father of the 1st Earl of Arundel. He was the founder

of the noble House of Mowbray. He is described as "one of the most

favoured of Henry's 'new men'". While he entered the king's service as

a household knight and brother of the king's butler, William d'Aubigny, in the years following the Battle of Tinchebrai in 1106 Nigel was rewarded by Henry with

marriage to an heiress who brought him lordship in Normandy and with the lands

of several men, primarily that of Robert de Stuteville. The Mowbray honour

became one of the wealthiest estates in Norman England. From 1107 to about

1118, Nigel served as a royal official in Yorkshire and Northumberland. In the

last decade of his life he was frequently traveling with

Henry I, most likely as one of the king's trusted military and administrative

advisors. Nigel's first marriage, after 1107, was to Matilda de L'Aigle, whose prior marriage to the disgraced and

imprisoned Robert de Mowbray, Earl of Northumbria, had been annulled based on

consanguinity. She brought to the marriage with Nigel her ex-husband's lordship

of Montbray (Mowbray). Following a decade of

childless marriage and the death of her powerful brother, Nigel in turn

repudiated Matilda based on his consanguinity with her former husband, and in

June 1118 Nigel married to Gundred de Gournay (died

1155), daughter of Gerard de Gournay and his wife Edith de Warenne,

and hence granddaughter of William de Warenne, 1st

Earl of Surrey. Nigel and Gundred had son who would

be known as Roger de Mowbray after the former Mowbray lands he would inherit

from his father, and he was progenitor of the later noble Mowbray family. Nigel

died in Normandy, possibly at the abbey of Bec in 1129.

1129

On Nigel d’Aubigny death in 1129 his

widow Gundreda administered the estate on behalf of

her under age son, Roger de Mowbray (1120 to 1188).

Nigel’s widow Gundreda administered

the estate on behalf of her under aged son Roger de Mowbray.

It was she who granted the whole of Welburn and Skiplam together with the western side of Bramsdale to Rievaulx Abbey who developed the whole area as

a series of granges and cotes, including Colt House and Stirk House in Brandsale.

1133

Henry II became King.

1138

On reaching his majority in 1138, Roger de Mowbray took title to

the lands awarded to his father by Henry I both in Normandy including Montbray, from which he would adopt his surname, as well as

the substantial holdings in Yorkshire and around Melton.

Sir Roger de Mowbray

(1120–1188) was an Anglo-Norman nobleman with substantial English landholdings.

A supporter of King Stephen, with whom he was captured at Lincoln in 1141, he

rebelled against Henry II. He made multiple religious foundations in Yorkshire.

He took part in the Second Crusade and later returned to the Holy Land, where

he was captured and died in 1187. Roger was the son of Nigel d'Aubigny by his second wife, Gundreda

de Gournay. On his father's death in 1129 he became a ward of the crown. Based

at Thirsk with his mother, on reaching his majority in 1138, he took title to

the lands awarded to his father by Henry I both in Normandy including Montbray, from which he would adopt his surname, as well as

the substantial holdings in Yorkshire and around Melton. King Stephen - Soon

after, in 1138, he participated in the Battle of the Standard against the Scots

and, according to Aelred of Rievaulx, acquitted himself honourably. Thereafter,

Roger's military fortunes were mixed. Whilst acknowledged as a competent and

prodigious fighter, he generally found himself on the losing side in his

subsequent engagements. During the anarchic reign of King

Stephen he was captured with Stephen at the battle of Lincoln in 1141.

Soon after his release, Roger married Alice de Gant (d. c. 1181), widow

of Ilbert de Lacy and daughter of Walter de Gant. Roger and Alice had two sons,

Nigel and Robert. Roger also had at least one daughter, donating his lands at

Granville to the Abbaye aux Dames in Caen when she became a nun there. In 1147,

he was one of the few English nobles to join Louis VII of France on the Second

Crusade. He gained further acclaim, according to John of Hexham, defeating a

Muslim leader in single combat. King Henry II - Roger supported the Revolt of

1173–74 against Henry II and fought with his sons, Nigel and Robert, but they

were defeated at Kinardferry, Kirkby Malzeard and Thirsk. Roger left for the Holy Land again in

1186, but encountered further misfortune being captured at the Battle of Hattin

in 1187. His ransom was met by the Templars, but he died soon after and,

according to some accounts, was buried at Tyre in Palestine. There is, however,

some controversy surrounding his death and burial and final resting-place.

Mowbray was a significant benefactor and supporter of several religious

institutions in Yorkshire including Fountains Abbey. With his mother he

sheltered the monks of Calder, fleeing before the Scots in 1138, and supported

their establishment at Byland Abbey in 1143. Later, in 1147, he facilitated

their relocation to Coxwold. Roger made a generous donation of two carucates of

land (c.240 acres), a house and two mills to the Order of Saint Lazarus,

headquartered at Burton St Lazarus Hospital in Leicestershire, after his return

from the crusades in 1150. His cousin William d'Aubigny,

1st Earl of Arundel and his wife Adeliza, the widow of King Henry I, had been

amongst the earliest patrons of the order and, when combined with Roger's

experiences in the Holy Land, may have encouraged his charity. His family

continued to support the Order for many generations and the Mowbrays lion

rampant coat of arms was adopted by the Hospital of Burton St Lazars alongside

their more usual green cross. He also supported the Knights Templar and gave

them land in Warwickshire where they founded Temple Balsall. Roger is credited

with assisting the establishment of thirty-five churches. The House of Mowbray,

the senior line of which would become Barons Mowbray, descended from Roger's

son Nigel, who died on crusade at Acre in 1191.

Robert II de Stuteville, one of the northern barons, commanded the

English at the battle of the Standard in August 1138

Robert II de Stuteville was

born about 1084 in Yorkshire. Son of Robert (Estouteville)

d'Estouteville I. Brother of Nicolas I (Estouteville) Stuteville and Emma (Estouteville)

de Grentmesnil. Husband of Erneburge

(Fitzbaldric) Stuteville. Husband of Jeanne (Talbot)

de Stuteville.

Father of Burga (Stuteville) Pantulf,

Nicholas (Stuteville) de Stuteville, Alice (Stuteville) Fleming, Osmund

(Stuteville) de Stuteville, John (Stuteville) de Stuteville, Patrick

(Stuteville) de Stuteville and Robert (Stuteville) de Stuteville III. Not

believed to have held lands in England. A supporter of Robert Curthose with his

father, he was captured at St.Pierre-sur-Dive

shortly before the battle of Tinchebrai. Died after

1138 after about age 54 in Cottingham, Yorkshire.

The landowners enjoyed significant revenues

from rents, fines, reliefs, benevolences, maritages (the fee paid by a vassal

following the feudal lord’s decision on a marriage), wardships and

opportunities for escheat (the reversion of land when owners died without

heirs). They were also relieved of many of the costs of running modern estates,

because they were owed duties of service. The value of these estates is best

seen not in monetary terms, but in the works they undertook. The castles were

obviously works of significant labour. The growth of monasteries also reflected

the power held by the nobility, including the costs of building churches.

(South

Yorkshire, the History and Topography of the Deanery of Doncaster in the

Diocese and County of York by Rev Joseph Hunter, 1828, page xvi to xviii).

1141

Roger de Mowbray was a supporter of King Stephen, with whom he was

captured at Lincoln in 1141, he rebelled against Henry II.

1154

Gundreda, on behalf of her guardian, gave land to Rievaulx abbey land

which included a place called Midelhovet, where Edmund the Hermit used

to dwell, and another called Duvanesthuat,

together with the common pasture within the valley of Farndale.

See full details at FAR00002.

By 1166, Roger de Mowbray having fallen out of favour with Henry

II, the lands of Kirkbymoorside had passed to the House Stuteville. Robert III

de Stuteville claimed the barony, which had been forfeited by his grandfather,

from Roger de Mowbray, who by way of compromise gave him Kirby Moorside. Roger gave Robert Kirkby

Moorside for 10 knights' fees in satisfaction of his claim (Victoria County History – Yorkshire, A History of the County of

York North Riding: Volume 1 Parishes: Kirkby Moorside, 1914).

Robert III de Stuteville, Baron of Cottingham, was

son of Robert II de Stuteville (from Estouteville in

Normandy), one of the northern barons who commanded the English at the battle

of the Standard in August 1138. His grandfather, Robert Grundebeof,

had supported Robert of Normandy at the battle of Tinchebray

in 1106, where he was taken captive and kept in prison for the rest of his

life. Robert III de Stuteville was witness to a charter of Henry II of England

on 8 January 1158 at Newcastle-on-Tyne. He was a justice itinerant in the

counties of Cumberland and Northumberland in 1170–1171, and High Sheriff of

Yorkshire from Easter 1170 to Easter 1175. The King's Knaresborough Castle and

Appleby Castle were in his custody in April 1174, when they were captured by

David of Scotland, Earl of Huntingdon. Stuteville, with his brothers and sons,

was active in support of the king during the war of 1174, and he took a

prominent part in the capture of William the Lion at Alnwick on 13 July (Rog. Hov. ii. 60). He was one of the witnesses to the Spanish

award on 16 March 1177, and from 1174 to 1181 was constantly in attendance on

the king, both in England and abroad. Stuteville by his wife, Helewise de Murdac, had two sons William and Nicholas and two

daughters, Burga, who was married to William de Vesci and Helewise, who was

married firstly to William de Lancaster, secondly to Hugh de Morville and

thirdly to William de Greystoke. He may have also had sons Robert, Eustace and

Osmund. Robert de Stuteville was probably brother of the Roger de Stuteville

who was sheriff of Northumberland from 1170 to 1185, and

defended Wark on Tweed Castle against William the Lion in 1174. Roger received

charge of Edinburgh Castle in 1177, and he built the first Burton Agnes Manor

House. However Roger may have been his kinsman, not

his brother, as son of Osmund de Stuteville (b. about 1125, of Burton Agnes,

Yorkshire, England, d. before Sep 1202) and his wife (m. abt

1146) Isabel de Gressinghall, daughter of William

Fitz Roger de Gressinghall. He is the probable

founder of the nunneries of Keldholme and Rosedale, Yorkshire, and was a

benefactor of Rievaulx Abbey. He seems to have died in the early part of 1186.

He claimed the barony, which had been forfeited by his grandfather, from Roger

de Mowbray, who by way of compromise gave him Kirby Moorside. The Stutevilles favoured the Benedictine monks of St Mary’s

Abbey, York and their own small house of nuns was founded at Keldholme near Kirbymoorside.

Rievaulx Abbey was unable to sustain its claim to the Farndale

property and a little before 1166, Robert de Stuteville granted Keldholme

Priory timber and wood in Farndale together with a vaccary, pasture and

cultivated land in East Bransdale

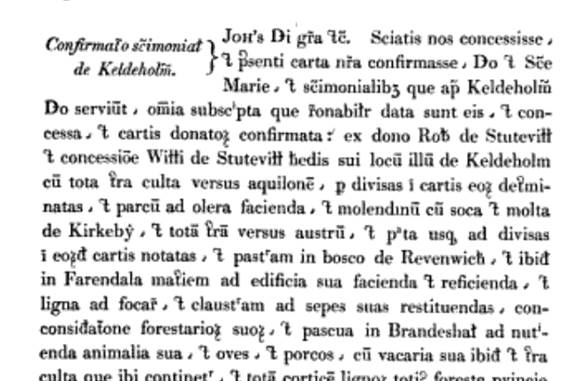

Rotuli Chartarum, 1199-1216, page 86: Confirmation of Keldeholm. Know

that we have granted and confirmed the present charter regarding Keldeholm, all the signatures that were given to them.

Grant of charters confirmed by the gift of Robert de Stuteville and the

grant of William de Stuteville to his son, that place of Keldholme, with the

whole tract of land towards the north of Kirkeby and the whole tract

towards the south and as divided as marked by the eord

cartis and pasture in the forest of Ravenwich, and there in Farendala

hay, and pasture in the forest of Ravenwich … (this translation needs

to be reworked!)

1173

Roger

supported the Revolt of 1173–74 against Henry II and fought with his sons,

Nigel and Robert, but they were defeated at Kinardferry,

Kirkby Malzeard and Thirsk.

The

Stutevilles came back into favour with the accession of Henry II and Roger de

Mowbray was compelled to hand back Kirbymoorside,

along with many others fees.

1186

Roger left for the Holy Land

again in 1186 to join the Second Crusade, but encountered further misfortune

being captured at the Battle of Hattin in 1187. His ransom was met by the

Templars, but he died soon after and, according to some accounts, was buried at

Tyre in Palestine.

Robert III de Stuteville

died in 1186.

1200

The arrangement of 1166

between Roger de Mowbray and Robert III de Stuteville was not ratified in the

king's courts, and the dispute broke out again between William de Stuteville,

son of Robert, and William de Mowbray, grandson of Roger, in 1200. However in time, William de Mowbray confirmed the previous

agreement and gave 9 knights' fees in augmentum

(Victoria

County History – Yorkshire, A History of the County of York North Riding:

Volume 1 Parishes: Kirkby Moorside, 1914).

In or about 1209 the Abbot of St. Mary's obtained from King John

rights in the forest of Farndale which the King had recovered from Nicholas de Stutevill. Pipe R. 11 John, m. 11.

Robert de Stuteville had given the nuns of Keldholme the right of

getting wood for burning and building in Farndale, (Cal. Rot. Chart. 1199–1216 (Rec. Com.), 86) and in or about 1209 the Abbot of St. Mary's obtained from King

John rights in the forest of Farndale which the king had recovered from

Nicholas de Stuteville. (Pipe R. 11 John, m. 11)

Keldholme Priory had right of pasture in Bransdale and Farndale by

grant of its founder, Robert de Stutevill.

Ryedale Historian,. Vol 1, 1965:

Nicholas de Stuteville (also Lord of Liddell, Stoteville, Estuiteville) (c1182

to 1233) came from the Anglo-Norman family Stuteville .

He was a younger son of Robert III de Stuteville (who died in 1183) and his

wife Helewise. After the death of his elder brother William de Stuteville , the possessions of the family, which included

Liddell in Cumberland and Cottingham in Yorkshire, came first in royal

administration. King Johann Ohneland left it to his

confidant Brian de Lisle , who exploited the goods

ruthlessly. It was not until 1205, when probably Williams minor son Robert

died, Nicholas could inherit the inheritance of his brother. However, the king

demanded an extraordinarily high fee of 10,000 marks from him before the

possessions were handed over to him. Since he could not raise this money, he

had to hand over to King Knaresborough Castle . As from 1213 rebelled a noble opposition to

the king, to mare Ville closed like many other northern English barons Easter

1215 the rebels in Stamford on. With the recognition of the Magna Carta 1215,

the king also had to return Knaresborough Castle to Stuteville. However, Stuteville continued to support the

rebels as the Barons opened war against the king. As a rebel, he was on 16

December 1215 by Pope Innocent III excommunicated .

Apparently, he was captured on May 20, 1217 in the victorious for the royal

party battle of Lincoln . Mare Ville fell into the

captivity of William Marshal, 1st Earl of Pembroke ,

the Regent for the minor King Henry III. who hoped for a high ransom from

him. Mare Ville paid over 1000 Mark

ransom, but before he was released, he had to goods from Kirby Moorside and

Handed over to Liddel , who provided annual income of

£200. And he probably died before the

end of the war of the barons in September 1217, at the latest before 30 March

1218. Lord Of Stuteville (1191 - 1233).

For rights in the forest of Farndale in 1209, 1210 and 1211, see FAR00003.

1217

The William de Stuteville of

1200 was succeeded by his brother Nicholas de Stuteville, who fought against

the King at Lincoln in 1217 and was taken prisoner there. He bound his manors

of Kirkbymoorside and Liddell to pay 1,000 marks as his ransom (Victoria County History –

Yorkshire, A History of the County of York North Riding: Volume 1 Parishes:

Kirkby Moorside, 1914).

1225

Entries in the Curia Regis

for 1225 and 1227 refer to Nicholas de Stuteville and pastures at Hoton (Hutton), Spaunton and Farendal. See FAR00005.

1229

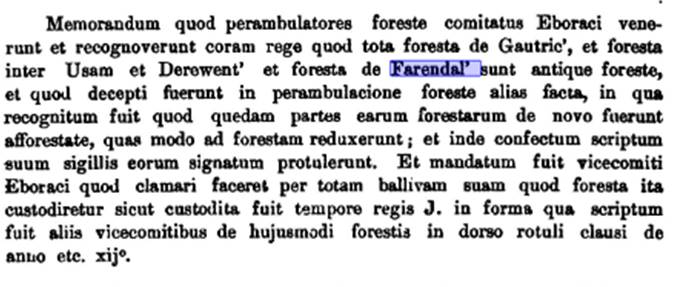

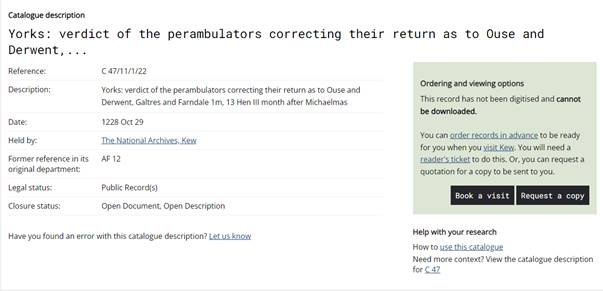

In 1229 Henry III decreed, ‘the whole of the forest of Galtres and the forest between the Ouse and the Derwent,

and the forest of Farndale, are ancient forests.’ But the forest was not

much used.

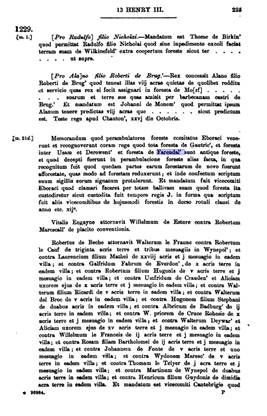

The Close Rolls, 13 Henry III for 1229: It should be remembered that the walkers of the forest

of the county of York came runt and recognized before the King that the whole

forest of Gautric and the forest between Usam and Derewent and the

forest of Farendal are ancient forest, and that

they had been deceived in the perambulation of the forest other times in

which it was recognized that certain parts of those forests had been reforested

, which they just brought back to the forest; and thence they brought forth the

finished writing, which was sealed with their seals.

1233

The

abbot and Nicholas II de Stuteville (son of Nicholas I de Stuteville) came to

an agreement concerning common of wood and pasture here, this being renewed in

1233. In 1232 Nicholas quitclaimed common of pasture in Farndale to the Abbot

of St. Mary's, York. (Feet of F. Yorks. 17 Hen. III, no. 14). Nicholas (Coll. Topog. et Gen. i, 11; Baildon, Mon. Notes (Yorks. Arch. Soc., 232). He had an elder son

Robert, who was enfeoffed of 1 knight's fee in Middleton. Nicholas succeeded to

Kirkby Moorside and Buttercrambe. ‘The Abbot grants

that if the cattle of Nicholas or of his heirs or of his men at Kikby, Fademor, Gillingmor or Farndale,

hereafter enter upon the common of the said wood and pasture of Houton,

Spaunton and Farendale, they shall have free way in

and out without ward set; provided they do not tarry in the said pasture.’ 17th

year of the Reign of Henry III. (Yorkshire Fines Vol LXVII). See FAR00007.

At about the same time

Robert gave to St Mary’s Abbey, who held the nearby manor of Spaunton, as much

timber and wood as they required together with pasture and pannage of pigs in

Farndale. The contemporaneous documents suggest that Farndale was regarded

primarily as a resource for timber and pasture in the mid twelfth century, with

little evidence of settlement.

The William de Stutevill of 1200 was succeeded by his brother Nicholas,

who fought against the king at Lincoln and was taken prisoner there. He bound

his manors of Kirkby Moorside and Liddell to pay 1,000 marks as his ransom. His

son Nicholas in 1232 quitclaimed common of pasture in Farndale to the Abbot of

St. Mary's, York (Feet of F. Yorks. 17 Hen. III, no. 14).

Nicholas died in 1233,

leaving two daughters and co-heirs, Joan wife of Hugh Wake, and Margaret, whose

marriage had been granted to William de Mastac (Victoria County History –

Yorkshire, A History of the County of York North Riding: Volume 1 Parishes:

Kirkby Moorside, 1914).

1241

Hugh Wake died in or about

1241 and Joan obtained the custody of his heirs till their full age.

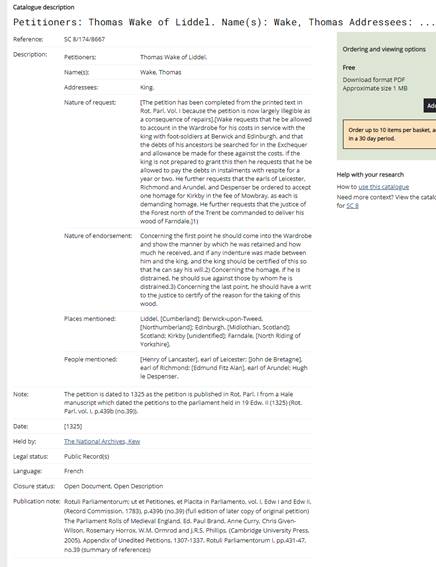

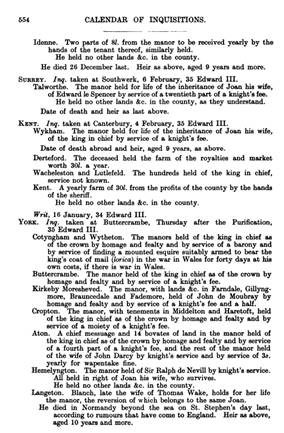

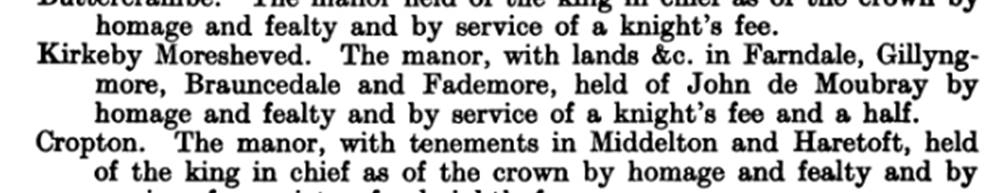

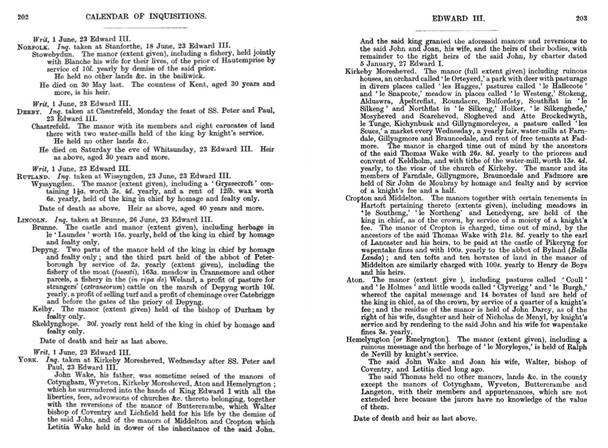

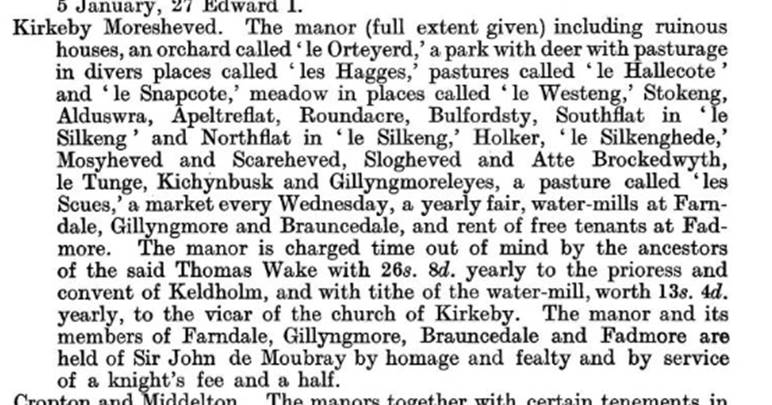

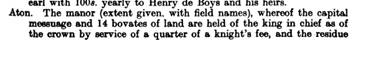

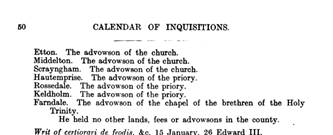

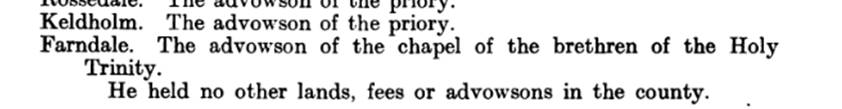

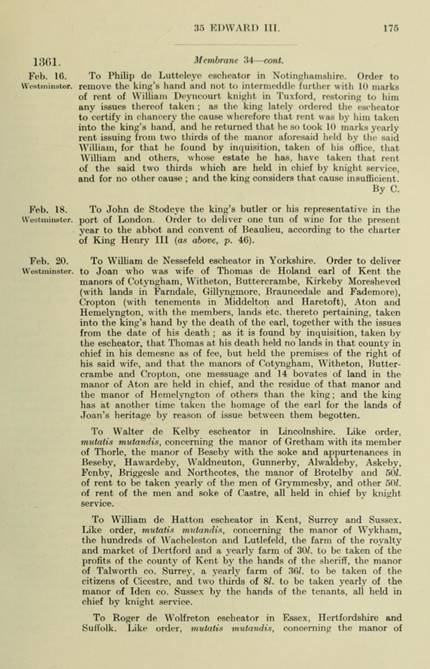

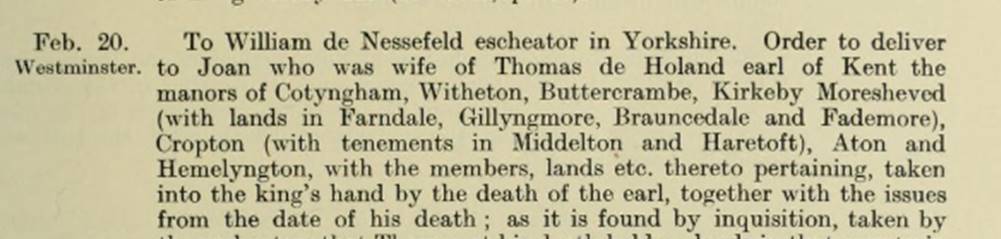

Inquisitions Post Mortem, Edward I,

File 31, Pages 252-262, Calendar of Inquisitions Post Mortem: Volume 2, Edward

I. Originally published by His Majesty's Stationery Office, London, 1906: Extent, Tuesday the eve of the Annunciation, 10 Edw. I. Kerkeby Moresheved.

The manor (full extent given with names of tenants), including the park

a league in circuit with 140 deer (ferarum), a wood

called Westwode a league in length, a messuage and

great close in Braunsedale held by Nicholas son of

Robert Nussaunt rendering an arrow at Easter, rents

of nuts and woodhens, 'gersume,' marchet

and the tenth pig, a messuage called La Wodehouse, waste places called Coteflat, Loftischo, Godefreeruding, Harlonde, and

beneath Gillemore Clif, dales called Farndale

and Brauncedale, and waste places called Arkeners and Sweneklis, held of

Roger de Munbray. Knights' fees pertaining to the manor:—

Circa 1250

In the mid thirteenth century, Lady Joan de Stuteville

successfully prosecuted the Abbot of St Mary’s York, for exceeding his rights

taking wood from Farndale by actually assarting 100

acres of land.

Joan de Stuteville was said to be afforesting her woods here in

the reign of Edward I (1239 to 1307). (Hund.

R. (Rec. Com.), i, 117.)

There is an undated Yorkshire Deed from about this time: Grant

by Nicholas Devias, being in good health and lawful

power (in mea bona sanitate et ligia

potestafe) to Alice his wife, for life, of an annual

rent of 10 li, which lady Joan de Stotevile gave him

for his service, namely, 20s. from the land in Farndale, held of him by

Adam de Ellerschae, and eleven marcs

from his two water-mills in Famedale, and two and

a half marcs from his water-mill in Brauncedale, payable half-yearly at Michaelmas and Easter. Paying

yearly at Christmas one silver penny for all service, etc. Witnesses, Sir

Richard Foliot, Sir Adam Newmarch [de Novo mercato), Sir Henry Biset, Sir Thomas de Hetun, William de Pligt Peter de Giptun, Clement de Nortun, Robert

de Slucropt, Colin de Nortun

and many others. (The Yorkshire

Archaeological Journal, Vol 16, 1893, page 92)

1253

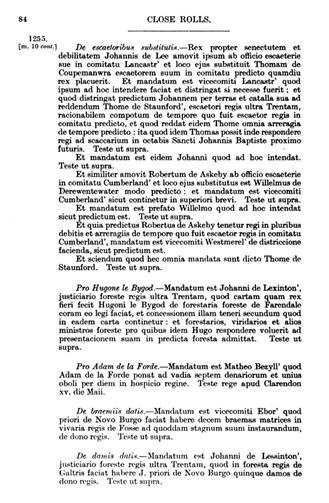

The Close Rolls, 37 Henry III for 1253: For Hugh le Bigod. The King committed to Hugh le Bigod the

whole forest of Farnedala, which the king

recovered by the consideration of the court towards the Abbot of St. Mary, to

be guarded until the King's return from Vasconia, or

as long as it pleased the King, in the same manner as the aforesaid Abbot had

that forest; and J de Lessinton was ordered to

release that forest to the same Hugh to be kept as aforesaid. Test as above.

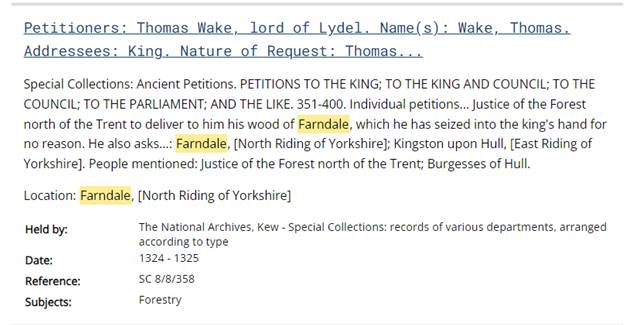

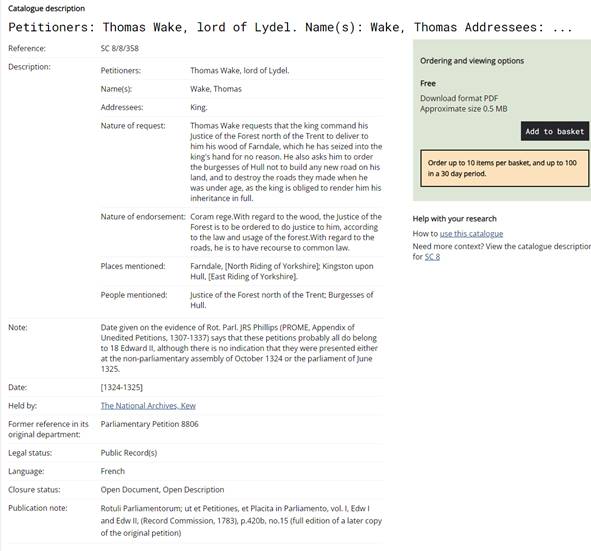

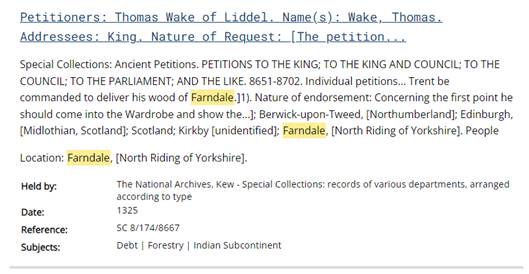

1254

In 1254 Henry III granted to

Hugh le Bigod and Joan his wife a weekly market on Wednesday at Kirkbymoorside

and a yearly fair there on the eve, day and morrow of the Nativity of St. Mary

1255

In 1255 Margaret was dead,

and Joan Wake had her lands. She married as her second

husband Hugh le Bigod, but as a widow was known as Joan de Stuteville.

Before her death she

enfeoffed in the manor of Kirkby Moorside her son Baldwin Wake, of whom the

King took homage as her heir in 1276.

The Close Rolls,

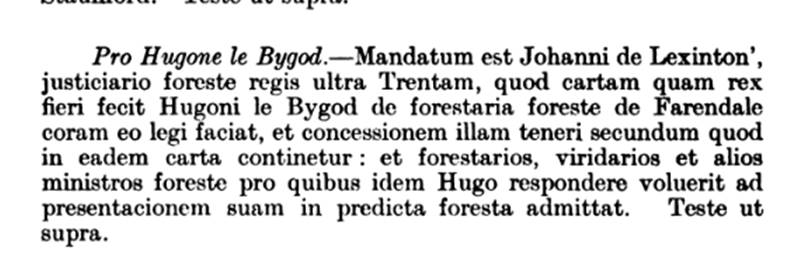

39 Henry III for 1255: For Hugh le Bygod. It was ordered

to John de Lexinton, justiciar of the King's forest

beyond Trent, that the charter which the king caused to be made to Hugh le Bygod concerning the forestry of the forest of Farendale

he shall make a law before him, and that grant shall be held according to what

is contained in the same charter: and he shall admit the foresters,

greenkeepers and other ministers of the forest for whom the same Hugh is

willing to answer for his presentation in the aforesaid forest.

The

Calendar of the Liberate Rolls, 1251 to 1260, Page 212, 1255: Allocate

to Hugh le Bygot, in his fine of 500 marks for the forestership of Farndale,