|

|

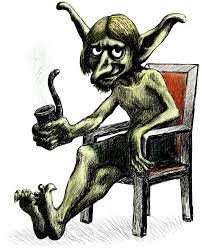

The Farndale Hob

|

|

The Yarn of the Farndale

Hob

Jonathan Grey was

a farmer who lived with his wife Margery in Farndale. He was woken one night

in the early hours by a noise coming from the barn. Margery woke up and within

a few minutes the whole household were awake. They gathered in the kitchen.

None of them

was brave enough to go and look. They all went back to bed, but they didn’t

sleep very well that night. The steady thump of the flail continued until first

light and then it stopped. Jonathan and his men crept cautiously to the barn

door and looked inside. They couldn’t believe their eyes,

more corn had been threshed than any one of them could have done in a whole

day.

And the next

night the unseen thresher was at work again. And by the time all

of the corn had been threshed they’d got used to the noise and slept

though it. But by then the unseen helper had become a regular hand on the farm.

In the spring the

mysterious assistant brought in the hay, in the summer he mowed and in the

autumn he sowed. But at sheep shearing time he excelled himself dealing with

whole flocks in a single night. There was no doubt about it good luck had come

to the farm.

Now most folk

believed that the work was being done by one of those small, brown, hairy folk all Yorkshire call hobs. Now these hobs are mostly

friendly to humans provided they’re not deliberately annoyed. And the one sure

way of annoying a hob is to suggest that they should cover up, because hobs

cannot stand clothes. But generally they’re helpful,

especially if they have a skill, like the one at Runswick Bay. Now that one

lives in a cave called the Hob Hole and he can cure the hiccups when no one

else can. All you have to do is to take the

unfortunate child to the mouth of the cave and call out: Hob Hole Hob, Hob

Hole Hob, my poor bairn’s gotten t’kin cough. So tak’t off, tak’t off. Within

a few days the cough will be gone.

Jonathan Grey

was well satisfied with his hob and he discussed with

his wife how they could reward the hob. Margery suggested that she put out a

bowl of her best cream every night in the barn. The following morning the bowl

was empty.

The hob stayed

on doing the work of two for the wages of a bowl of cream. In the course of

time Jonathan and Margery became quite wealthy. But everyone’s luck runs out

eventually and Margery in the prime of life sickened and died.

Jonathan was

grief stricken and it was only then that he discovered that Margery had done

almost as much work as the hob. When the worst of his grief had passed Jonathan

decided he should take another wife.

Jonathan’s

second wife was of a saving disposition. She resented every mouthful the farm

lads and lassies ate and above all she grudged the bowl of cream put out for

the hob every night.

Yon hob fed

on the best of cream while the rest of us is well satisfied with butter milk

and ya canna be sure tis the hob that drinks the cream likely as not it’s cats

or rats that leaves the bowl clean in the morning. Husband, we’re likely to be

ruined by your feckless ways.

Jonathan took

no notice, as long as he was master the hob would have

his reward. But one night while Jonathan was out working late his wife put out

the bowl as usual but it contained nothing but skimmed

milk.

That night for

the first time in years the hob was quiet. No corn was threshed, no harness

mended, no wool carded and no spinning done.

Spring came but

there was no help from the hob with the haymaking, nor with the sheep shearing

in the summer. The harvest came and went but the hob did no mowing, tying or carrying. This was bad news

and the farm was suffering but worse was to follow.

Churn as she

might the wife’s butter wouldn’t come. The cream only rolled itself into tiny

balls all farmers’ wives call pins and needles. Her cheeses went black with

mould, her hams and bacons went rotten. Foxes stole the geese she was fattening

for the Christmas market and the cows went dry. Sheep got foot rot and pigs

swine fever. For every piece of good luck in the past there now seemed to be

three calamities.

The house

became haunted, it sounded as if a host of demons were throwing things around

in the kitchen. There were blood-curdling screams though nothing was ever seen.

Unseen hands snatched off the bedclothes while candles snuffed themselves out.

Furniture moved of its own accord, doors locked and barred themselves while

farmyard gates opened allowing the animals to wander off onto the trackless

moor.

No servants or

labourers would stay on the farm. Jonathan was at his wits end. He’d long

suspected that his wife must have offended the hob in some way and although at first she denied it eventually she confessed that one night

she’d put out skimmed milk instead of cream. Jonathan was in despair,

he knew what revenge an offended hob could take. He tried his best to make amends but it was all to no avail. At last

he decided to leave the farm and try his luck elsewhere.

All

of their goods

fitted easily onto one farm cart and the last thing to come out was their old

feather bed. Jonathan placed it on top of all their other broken bits and

pieces and the old churn from the dairy was upturned at the back of the cart.

The grudging wife climbed up and sat on the feather bed. Jonathan took his seat

and picked up the reins.

The horse moved

off. They’d just gone round the first bend when Jonathan came face-to-face with

one of his neighbours. Ado Jonathan lad, you can’t have come to this surely?

Aye, we’ve

come to this, we’re flitting.

And then there was a strange voice.

Aye, we’re

flitting.

Sat there

cross-legged on the upturned churn was the oldest, ugliest, hairiest little man

you’ve ever seen. His eyes bulged with malicious glee.

Lyric by Giles

Watson, 2013. Based on a story recorded by H.L.

Gee, Folk Tales of Yorkshire, London, 1952, pp. 17-22: The Farndale

Hob. She left skim-milk in the jug – Now that was over hasty – And I was used

to clotted cream. That’s when I turned nasty. I came the day when poor Ralph

died, Who used to shear and mow: They found him on the

open moor Beneath a drift of snow, And that same night I set to work To thresh

the harvest corn, And year on year, no one dared To laugh my work to scorn. I

drove the oxen in a team, Sheared sheep and hauled the hay For

a daily jug of cream – And generations passed away. She claimed that cream was

luxury And times were getting hard: I took one taste

and spat it out, And screaming through the yard, I turned the milk-churns over,

I made the butter spatter, I filled the early hours with A grim unholy clatter,

I banged the copper kettle, I haunted all her dreams; I ripped off her

bedclothes With heart-rending screams. She thinks she can escape from me By moving down the street, But I will patter after her On

little hobnailed feet: She left skim-milk in the jug – Now that was over hasty

– And I was used to clotted cream. That’s when I turned nasty.

Yorkshire Hobs

The Northern Weekly Gazette, 6 December 1902:

HOBMEN OF

WENSLEYDALE AND HOBGARTH.

So far as

the writer’s information goes, the traditions of the North Riding have

preserved the deeds of but very few hobmen. Their

number can almost be counted on the fingers of both hands. Indeed, if we

include in the known list, Elfi, the Farndale dwarf, and the two

dwarfs who for long lived in houses near to Mickleby

and Roxby, we find written up on the pages of tradition that mention is made of

one dozen of these little folk. Of course, once every ale would have its hobman, and doubtless the larger dales, such, for instance,

as Wensleydale, would claim to have no less than a score at the very least. But

the memory of all, save one, has been forgotten.

The

following, as far as the writer knows, is a full list of the North Riding hobmen, occasionally spoken of as goblins, brownies and

dwarfs: the hobman of (1) Hob Hole, Runswick Bay; (2)

Hob hill, near to Upleatham; (3) Hob Moor, York;

Hob or Hart Hill, Glaisdale; (4) Hogarth near Rosedale; (5) Hobthrush

Hall, Scarrs; (6) Obtrush

Roque, Kirkbymoorside; (7) Sorrowsikes in Wensleydale; (8) Gunnerside

in Swaledale; (9) Elfi, the Farndale dwarf; (10) the

dwarf of Mickleby; and (11) the dwarf of Roxby.

Some lore

students will be inclined to include in the above the little chap who has had

under his command the Whorleton elves, but there is

sufficient known in connection with his character which casts some doubt on the

advisability of such a course. In no single instance is it recorded of him as

having done one kindly action, and he is mentioned in several stories. Now it

must be remembered, nay, insisted upon, that the genuine hobman

was by nature given to kindly deeds, and many stories set forth this theory is

being the true character of his order. Certainly he

was prone to take offence, but when such a sad event transpired, the genuine hobman neither indulged in malice nor revenge, but just

took himself away. Again hobmen

were not subject either to the spells or commands or prayers of witches; Such

among these little folk as were not hobs, but belonged either to the goblin or

elf order, and as such the more careful student will in future consider them.

The Wensleydale hob, had many friends among his brethren in the dale, all of

whom, as has been stated, at least so far as the writer's knowledge of the

subject goes, are now forgotten.

The Hobthrush was believed to have been a small man who

helped a household around the hearth and kitchen. Throughout Yorkshire

there are place names, traditions and tales about the naked goblins, there is

no doubt there is an influence from Scandinavia in the tales. The Nisse

and tomte were similar entities from Denmark and Sweden. The “nisse”

would sweep the floor and clean the house for the family it attached itself to.

In Sweden a being called “tomte” and in Holland, Kaboutermannekin

did similar jobs.

In Otia Imperialia,

Gervase de Tilbury wrote that hobs are called “portuni” in

England and “neptuni” in France. This suggests a possible link with

water and water demons. “Portuni” were also said to join a horseman

invisibly and lead him into a ditch, laughing.

In the

thirteenth century Master Rypon of Durham, mentions “Thrus”,

a certain demon who would grind corn until the householder gave him a new tunic

one day. He refused to grind corn saying in English – “Suld syche a proude

grome grynd corn?” This line echoes the Swedish tomte:

“The young spark is fine, He dusts himself! Nevermore will he sift.”

Robin

Goodfellow appeared in a tale comparable to the Hart Hall Hob of Glaisdale in The Mad Pranks and Merry Jests of Robin Goodfellow (1628):

Robin Goodfellow often would in the night visit farmers houses and helpe

maydes breake hempe, to bowlt, to dresse flaxe, to spin and do other workes,

for hee was excellent in everything. One night hee

comes to a farmers house, where there was a goode handsome mayde; this mayde

having much work to do. Robin one night did helpe her, and

is sixe houres did bowlt more than she could have done I twelve houres. The

mayde wondred the next day how her worke came, and to know the doer, she

watched the next night that did follow. About twelve of the clocke, in came

Robin, and fell braking of hempe and for to delight himself he sung his mad

song. The mayde, seeing him bare in clothes, pittied him, and against the next

night provided him a wast coate.

Robin comming the next night to worke, as he did before, espied the wast coate, where at he started and said: “Because thou lay’st me himpen, hampen, I will neither bolt nor stampen:

‘Tis not your garments new or old, That Robin loves: I feele no cold. Had you

left me milke or creame, You should have a pleasing

dreame. Because you left no drop or crum, Robin never more will come.” So went

hee away laughing, ho, hoh!

Himpen, Hampen was also known in an earlier

couplet as Hemton Hamtom but should be clearly read as hardin hemp, as in the

Hart Hall Hob tale. “Hardin” means hessian, while “hemp” was a rough working

shirt.

The name for a

hob in the south became Robin Goodfellow. In Northern England and the

North Midlands the term commonly known for hobs was Hobthrus,

-thrust, thrush. In Lincolnshire there is a Jacob Thrust and in Cheshire, Hob –

dross.

“Hob like

Rob and Robin, Dob and Dobbin is a diminutive of Robert. Thus

Robert the Bruce was contemptuously styled King Hob,” writes Dr Bruce Dickins

in Yorkshire Folklore (1947) “Yet Robert was a well known man’s name, and the

unsavoury records of witch trials show that the demon was given a Christian

name.”

Hob is also

common in many South Yorkshire place names including Hob Beck, Ilkley; Hobcroft Road, Sheffield, Later Changed to Dobcroft,

although Hobcroft is a surname in South Yorks; Hobcross

Hill, Doncaster; Hob Lane, Huddersfield; Hobb Stones Wood; Hob’s Hurst House,

Chatsworth.

Near Sheffield

is the village of Dore, and a Hobthrush story very similar to Grimms “The

Elves and the Shoemaker” came from there. The story tells how a poor

shoemaker found a piece of leather he had cut made into a pair of shoes. He

sold them and bought enough to make two pairs and so on. He stayed up one night

and saw Hobthrust making shoes faster than the shoemaker could fling them out

of the window. Hence the Sheffield saying when a man is heard to boast about

his output of knives etc, the rejoiner is “Ah, tha can mak ‘em faster than

Hobthrust can throw shoes out o’ t’window!”

North Yorkshire

has possibly more hobs and hob related place names than the whole of England.

This may be due to the large amount of Viking settlements in the moors, and

where the Hob tales bloomed. Often locations and farms hold related names such

as, Hob Cross, Hob Hill, Hob Green, Hob Thrush Grange, Hobdale, Hob Holes,

Hobgarth, Hob’s Cave etc.

In 1905, the “Evolution of a Yorkshire Town” by George Calvert,

contains a list of known Hobs just in the Pickering district in 1823: Lealham

Hob, Hob o’ thrush, T’ Hob o’ Hobgarth, Cross Hob o’ Lastingham, Farndale

Hob of High Farndale, T’Hob o’ Stockdale, Scugdale Hob, Hedge Hob o’

Bransdale, Woot Howe Hob, T’Hob o’ Brakken Howe etc.

The Hob from

Hob Hill, Upleatham, who assisted the Oughtred family as late as 1820 was the

normal type of Hob, he assisted in herding, turned hay, and tailed turnips. They

did nothing to annoy him but one day a man left his coat on the winnowing

machine overnight. The Hob turned into a poltergeist and caused so much trouble

they decided to flit. The day the Oughtreds were

moving a friend came by and visited them. He asked Oughtred if he was moving

when the Hob replied “Aye getting ti flit ti morn.”

Oughtred then decided to stay and kept the Hob under control by magic.

This story

compares to the Farndale Hob, who was also a elf like

fellow with long shaggy hair. He attached himself to a farm belonging to

Jonathan Gray. The Hob worked very hard all the time, but only asked for two

things. Firstly, noone should see him work. Secondly,

he should be left a jug of cream nightly. Unfortunately

Jonathan’s wife died and later he remarried. The new wife was mean with money

and swapped the jug of cream for skimmed milk. The Hob stopped work and instead

of leaving he became mischievous and things started to

go wrong about the farm. Soon no-one would work for Jonathan

so he was resolved to move from the farm. A friend who had been away saw

Jonathan in his cart moving home. “Noo, then Jonathan, what’s gahin on?”

he asked. Jonathan exclaimed his problems and added “So you see, we’re

flitting.” And to his horror, the lid of a milk churn raised

and a small, brown and wizened face peered out. “Aye,” said the Hob, “We’re

flitting.”

The Hob at Hobgarth in Glaisdale collected sheep and repaired fences

that had been broken down by a vindictive neighbour. (c.1760) He was described

as a little old fellow, with very long hair, large feet, hands, eyes and mouth stooping much as he walked and carrying a

long holly stick.

At Hob Hole,

Runswick Bay, lived a Hob in a cave that was destroyed many years ago by jet diggers but the legend persists. The Hob could cure children

of Kink cough now known as Whooping Cough. When a child was suffering from

whooping cough, the mother would carry the patient down to the beach and walk

along to the mouth of the Hob Hole. There she would call out: “Hob Hole Hob,

My bairn’s gotten t’kink

cough, Tak it off, Tak it off.” There is no mention in records whether any

payment or gift for his services and there is no notes

if it was successful or not. What may be a coincidence is that a few yards away

from the Hob’s Hole is the Claymore Well Bogles. The bogles lived at Claymore

Well and could be heard washing and beaching their clothes. They would beat

them with an old fashioned implement known as a

“battledore.” The bogles would for one night a week do their washing and the

noise of them would fill the night air of neighbouring town, Kettleness. Again the records

don’t state what the bogles looked like or if anyone ventured down the well.

The Over Silton

Hobthrush lived in Hobthrush Hall, in a cave running under the Scarrs, cliffs

which rise a little north west of the village. He

served the tenant of the farm on which he lived,

churning cream put out for him overnight. One evening the customary reward of

bread and butter was forgotten and in disgust Hobthrush left the neighbourhood

forever.

Another Hob

lived in Hob’s Cave, Mulgrave Woods. If you wished to beckon him, you should

call out. Hobthrush Hob! Where is thou!

and the reply: Ah’s tying on mab left – fuit shoe,

An ah’ll be wiv thee – Noo!

The Hobs enrich

Yorkshire folklore with their strange behaviour, nudity and off

the cuff remarks.

During the

Victorian age it was believed that the Hobs were remnants of folklore brought

to these shores by the Angles and Scandinavians. Ancient burial grounds,

barrows or prehistoric settlement sites were often named after Hobs. Examples

are Hob Hole in Baysdale which is a prehistoric

settlement.

According to J.Phillips in Mountains and Sea coast of Yorkshire (1853):-

“These beliefs persisted till well on into the nineteenth century. How many

of them survive today?”

The Bridlington Free Press, 19 March 1924:

YORKSHIRE

FANCIES. GOBLINS AND FAIRIES.

The folklore

of Yorkshire and the north of England have been considerably influenced by the

Danish invasions. The Danish occupation of these parts has left a very strong

impression in various ways, on place names, racial characteristics, literature and beliefs. The old Scandinavian mythology, more

perhaps than any other, was the expression of a people's attitude towards wild

nature. Children, as they were, of a cold climate, a stern soil

and giant hills, the northmen and their neighbours

grew to be the daring warriors, giant men careless of life and limb and fired

with a desire for adventure and discovery. It was partly this restlessness

which impelled them to cross the stormy seas in their frail ships and to

plunder the coast of north and eastern Britain. These Hrothgar like war

invaders who came in the wind from the north, those sea wolves, brought with

them their own crude religion, their own bloodthirsty superstitions cover their

own campfire legends of heroes and men of valour, of impossible tasks

accomplished, of daring feats and mighty fights with man and beast. Such ideas

became infused with the Pagan beliefs of the troubled people of our land, and

though they have long since been kissed away by the loftier message of

Christianity as the sun lifts up a morning mist, still

their influence is not wholly departed, and quaint beliefs still linger, and

have so lingered as to earn the title of being Yorkshire fancies.

The

existence of dwarfs and trolls or goblins was never doubted by the Norsemen.

... Of the

innumerable brownies and goblins that are have been

the subject of old wives tales, none the better known than the Hob of Farndale.

The eccentricity of this curious little person is certainly amusing and the

story of his attachment to the Grey family was remarkable enough for Tennyson

to have made mention of him in Walking to the Mail. We have not the space to

get the story in detail, nor is it required, since it is well known. We

condensed the version given by Shaw Jeffrey in “Whitby Lore and legend”.

Some 70

years ago, in the wildest and most romantic part of one of those fine dales

which lie from 17 to 18 miles from Whitby, there lived a farmer named Jonathan Grey.

The prosperity of the family was aided by an uncommon advantage. Jonathan's grand father had had a servant, Ralph, who was a stout and

lusty fellow, but who was unfortunately frozen to death in a wreath of snow

whilst returning from the fair. Some little time after the death of the

luckless Ralph a visitor of an uncommon kind appeared in the house of his

master. One of the family who happened to be awake at midnight heard a thump

the thump of a flail in the barn. The whole house was awakened

and all were of the opinion that it was no mortal thresher. Night after night

this strange visitor worked on the farm doing the work of a dozen men. The

farmer, feeling that some recompense was due to one who worked so hard, ordered

that a jug of cream and other viandes should be

placed in the barn nightly. On the death of the old man, Ralph passed, together

with the stock and crop, to the next in succession from him to Jonathan.

Jonathan married a wife who was well off and was kind to the nightly visitor,

but she died and Jonathan married again. His second

partner was a woman of a saving disposition. She grudged the viandes set nightly in the barn and in

spite of her husband put skimmed milk out in place of cream. From that

day forward not a jot of work would the visitor do.

Moreover, not only did bad luck come up on the whole household, but strange

noises were heard at the dead of night, kettles were turned into drums, pewter

plates into symbols, bed clothes were pulled off and bed beds lifted up, and then succeeded a concert of knockings,

groanings, scratchings, hissings, howlings, drummings, thumpings, so that no

rest whatever could be had in the house. The unlucky pair endured these

torments for some time until at last they resolved to seek another abode. Accordingly having taken a farm at some distance Jonathan

began the removal of his property. He had just set out from his habitation with

the last cartload of his household goods and farming utensils, when he was met

by an old acquaintance. “Hey, Jonathan, what are ye about?” “we

are flitting,” he replied with a sigh. “yes,” said a

strange voice close by, “we're flitting.” The pair stared at the pile of odds

and ends until in their amazement they saw an awful looking figure seated on an

old churn, a figure with tremendous eyes, which seemed to dance with malicious glee.

Jonathan surveyed him with a mixture of fear and vexation and exclaimed, “If

thou art flitting, we’ll e’en flit back again.”

The Yorkshire Post and Leeds Intelligencer, 6 August 1929 also

told the tale.

Alfred

Lord Tennyson, Walking to the Mail:

'John'. I'm

glad I walk'd. How fresh the meadows look Above the

river, and, but a month ago, The whole hill-side was

redder than a fox. Is yon plantation where this byway joins The

turnpike?

'James'. Yes.

'John'. And

when does this come by?

'James'. The

mail? At one o'clock.

'John'. What is

it now?

James'. A

quarter to.

'John'. Whose

house is that I see?

No, not the

County Member's with the vane: Up higher with the yewtree

by it, and half A score of gables.

'James'. That?

Sir Edward Head's:

But he's

abroad: the place is to be sold.

'John'. Oh,

his. He was not broken?

'James'. No,

sir, he,

Vex'd with a morbid devil in his blood

That veil'd the world with jaundice, hid his face

From all men,

and commercing with himself,

He lost the

sense that handles daily life--

That keeps us

all in order more or less--

And sick of

home went overseas for change.

'John'. And

whither?

'James'. Nay,

who knows? he's here and there.

But let him go;

his devil goes with him,

As well as with

his tenant, Jockey Dawes.

'John'. What's

that?

'James-. You

saw the man--on Monday, was it?--

There by the

hump-back'd willow; half stands up

And bristles;

half has fall'n and made a bridge;

And there he

caught the younker tickling trout--

Caught in

'flagrante'--what's the Latin word?--

'Delicto'; but

his house, for so they say,

Was haunted

with a jolly ghost, that shook

The curtains,

whined in lobbies, tapt at doors,

And rummaged

like a rat: no servant stay'd:

The farmer vext packs up his beds and chairs,

And all his

household stuff; and with his boy

Betwixt his

knees, his wife upon the tilt,

Sets out, and meets a

friend who hails him,

"What!

You're flitting!" "Yes, we're flitting," says the ghost

(For they

had pack'd the thing among the beds).

"Oh,

well," says he, "you flitting with us too--

Jack, turn

the horses' heads and home again".

'John'. He left

'his' wife behind; for so I heard.

'James'. He

left her, yes. I met my lady once:

A woman like a

butt, and harsh as crabs.

'John'. Oh,

yet, but I remember, ten years back--

'Tis now at

least ten years--and then she was--

You could not

light upon a sweeter thing:

A body slight

and round and like a pear

In growing,

modest eyes, a hand a foot

Lessening in

perfect cadence, and a skin

As clean and

white as privet when it flowers.

'James'. Ay,

ay, the blossom fades and they that loved

At first like

dove and dove were cat and dog.

She was the

daughter of a cottager,

Out of her

sphere. What betwixt shame and pride,

New things and

old, himself and her, she sour'd

To what she is:

a nature never kind!

Like men, like

manners: like breeds like, they say.

Kind nature is

the best: those manners next

That fit us

like a nature second-hand;

Which are

indeed the manners of the great.

'John'. But I

had heard it was this bill that past,

And fear of

change at home, that drove him hence.

'James'. That

was the last drop in the cup of gall.

I once was near

him, when his bailiff brought

A Chartist pike. You should have seen him wince

As from a

venomous thing: he thought himself

A mark for all,

and shudder'd, lest a cry

Should break

his sleep by night, and his nice eyes

Should see the

raw mechanic's bloody thumbs

Sweat on his blazon'd chairs; but, sir, you know

That these two

parties still divide the world--

Of those that

want, and those that have: and still

The same old

sore breaks out from age to age

With much the

same result. Now I myself, [6]

A Tory to the

quick, was as a boy

Destructive,

when I had not what I would.

I was at

school--a college in the South:

There lived a flayflint near; we stole his fruit,

His hens, his

eggs; but there was law for 'us';

We paid in

person. He had a sow, sir. She,

With meditative

grunts of much content, [7]

Lay great with

pig, wallowing in sun and mud.

By night we dragg'd her to the college tower

From her warm

bed, and up the corkscrew stair

With hand and

rope we haled the groaning sow,

And on the leads we kept her till she pigg'd.

Large range of

prospect had the mother sow,

And but for

daily loss of one she loved,

As one by one

we took them--but for this--

As never sow

was higher in this world--

Might have been

happy: but what lot is pure!

We took them

all, till she was left alone

Upon her tower,

the Niobe of swine,

And so return'd unfarrowed

to her sty.

'John.' They

found you out?

'James.' Not

they.

'John.'

Well--after all--What know we of the secret of a man?

His nerves were

wrong. What ails us, who are sound,

That we should

mimic this raw fool the world,

Which charts us

all in its coarse blacks or whites,

As ruthless as

a baby with a worm,

As cruel as a

schoolboy ere he grows

To Pity--more

from ignorance than will,

But put your

best foot forward, or I fear

That we shall

miss the mail: and here it comes

With five at

top: as quaint a four-in-hand

As you shall

see--three pyebalds and a roan.

Elfi of Farndale

Gordon Home's Pickering: The Evolution of an English Town (1905):

The other story is known as "The

Legend of Elphi." Elphi

the Farndale dwarf was doubtless at one time the central figure of many a

fireside story and Elphi's mother was almost equally

famous. The most tragic story in which they both play their leading parts is

that of Golpha the bad Baron of Lastingham

and his wicked wife. The mother helped in hiding some one Golpha

wished to torture. In his rage he seized the mother, and

sentenced her to be burnt upon the moor above Lastingham.

Elphi to save his mother, called to his aid

thousands of dragon-flies, and bade them carry the

news far and wide, and tell the fierce adders, the ants, the hornets, the wasps

and the weasels, to hurry early next day to the scene of his mother's execution

and rescue her. Next morning when the wicked Golpha,

his wife, and their friends gathered about the stake and taunted the old dame,

they were set upon and killed, suffering great agonies. But Elphi

and his mother were also credited with all the power of those gifted with a

full knowledge of white magic, and their lives seem to have been spent in

succouring the weak. Mr Blakeborough tells me that the remembrance of these two

is now practically forgotten, for after most careful enquiry during the last

two years throughout the greater part of Farndale, only one individual has been

met with who remembered hearing of this once widely known dwarf.

The hob-men who were to be found in

various spots in Yorkshire were fairly numerous around Pickering. There seem to

have been two types, the kindly ones, such as the hob of Hob Hole in Runswick

Bay who used to cure children of whooping-cough, and also

the malicious ones. Calvert gives a long list of hobs but does not give any

idea of their disposition.

References

Yorkshire Hobs – article by Bruce Dickins, Yorkshire Dialect Society 1947

Literature and Pulpit in Medieval England – GR Oswt 1933

County Folklore – Folklore Society 1882 – 1914

Folk Tales from the North Yorks Moors – Peter Walker 1990

The Dalesman March 1978

Hob stories

Lealholm Hob.

Hob o' Trush.

T'Hob o' Hobgarth,

Cross Hob o' Lastingham.

Farndale Hob o'

High Farndale.

Some hold Elphi to have been a hob of Low Farndale.

T'Hob of Stockdale.

Scugdale Hob.

Hodge Hob o'

Bransdale.

Woot Howe Hob.

T'Hob o' Brackken

Howe.

T'Hob o' Stummer Howe.

T'Hob o' Tarn Hole.

Hob o' Ankness.

Dale Town Hob

o' Hawnby.

T'Hob o' Orterley.

Crookelby Hob.

Hob o' Hasty

Bank.

T'Hob o' Chop Gate.

Blea Hob.

T'Hob o' Broca.

T'Hob o' Rye Rigg.

Goathland Hob

o' Howl Moor.

T'Hob o' Egton High Moor.