Kirkdale Cave

A Time Machine to a different era of

geological time in the heart of our ancestral home

|

This

is a new experiment. Using Google’s Notebook LM, listen to an AI powered

podcast summarising this page. This should only be treated as an

introduction, and the AI generation sometimes gets the nuance a bit wrong.

However it does provide an introduction to the themes of this page, which are

dealt with in more depth below. Listen to the podcast for an overview, but it

doesn’t replace the text below, which provides the accurate historical

record. |

|

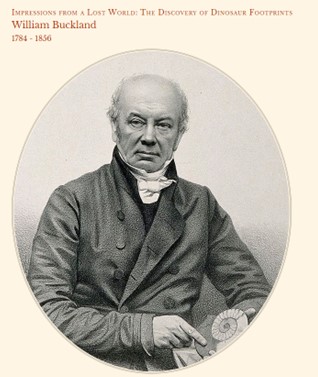

William Buckland and the Bone Caves

The

story of William Buckland’s amazing discovery, five hundred metres from our

ancestral home |

The geographic guide to Kirkdale cave

will help you to locate it.

The

discovery of Kirkdale Cave

In 1821, the

woodland clearing only 50 metres from Kirkdale minster, close to the ford

across the Hodge Beck, was part of a quarry. It was being worked for road stone

and quarry workers cut through the cave entrance. They spread stone chippings

on the road, not noticing small bones.

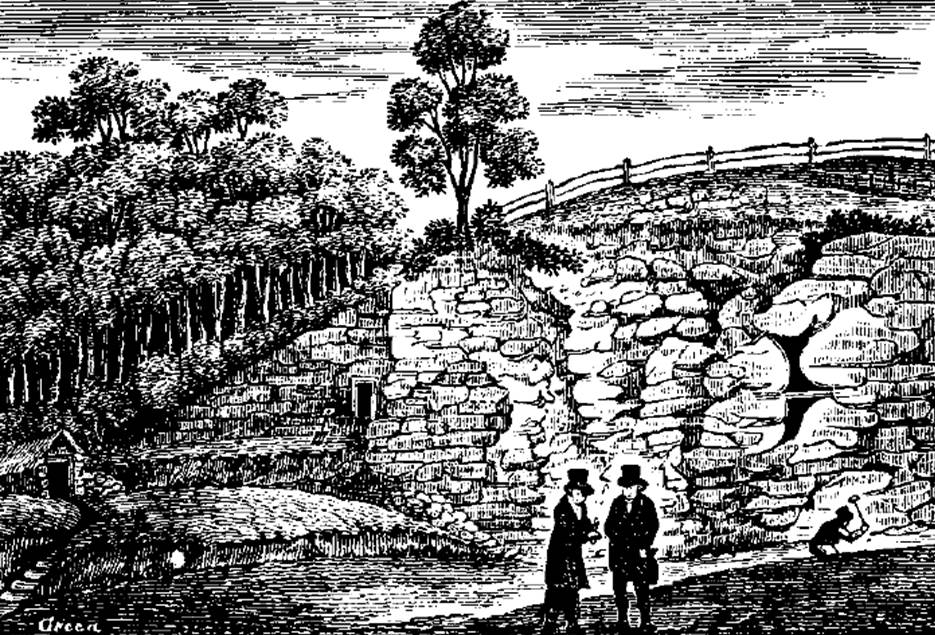

Kirkdale

Cave from Rev. George Young D.D, A Picture of Whitby and its environs,

1840.

The cave was

later found to have been covered by many inches depth of animal bones beneath a

layer of dried mud. The vicar of Kirkdale spotted the bones and reported his

find to the Reverend William Buckland, who was a professor of minerology and

geology at Oxford University.

Buckland

came to the site in 1822. The discovery at Kirkdale was made at the beginning

of a new age of Enlightenment and new approaches to stratigraphic dating were

being developed.

Some of the

fossils were sent to William Clift, the curator of the museum of the Royal

College of Surgeons, who identified some of the bones as the remains of hyenas

larger than any of the modern species. The analysis enabled Buckland to report

to the Royal Society in London the discovery of:

• Straight tusked elephant, rhinoceros,

hippopotamus, bison and giant bear finds from an earlier warmer period of the

earth’s history; and

• Mammoth, woolly rhinoceros, reindeer,

horse and sabre tooth tiger remains from the later cold spells.

Buckland had

begun his investigation believing that the fossils in the cave were diluvial.

He initially concluded that they had been deposited there by a deluge that had

washed them from far away, possibly the Biblical flood. On further analysis

Buckland realised that such an analysis made no sense.

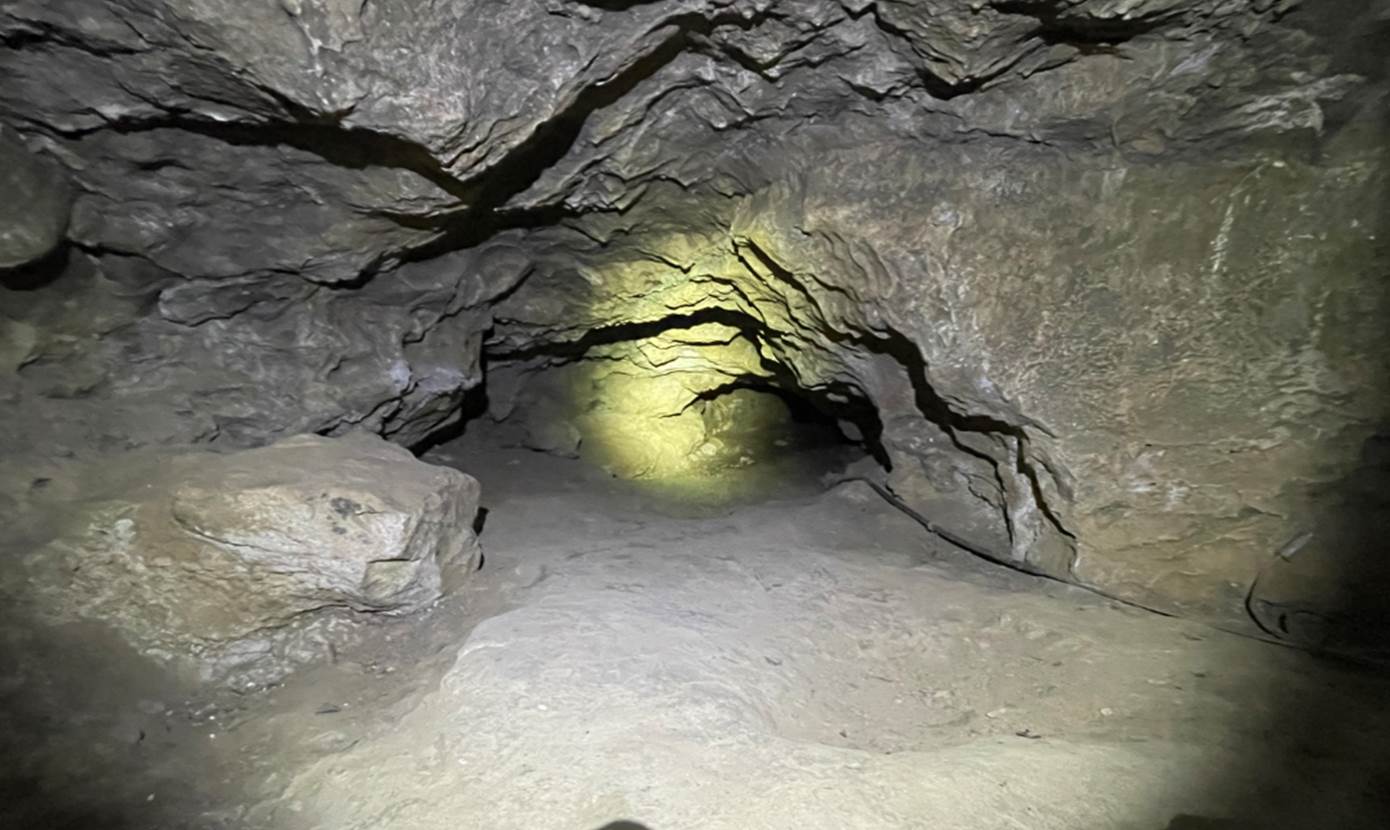

The hyena

bones were abundant and evidenced that hyena had dragged animal parts into the

cave to eat them. The mouth of the cave is not larger than one metre in height,

so Buckland concluded that the varied animal remains were the prey of hyena,

dragged into the cave. He came to realise that the cave had never been open to

the surface through its roof, and that the only entrance was too small for the

carcasses of animals as large as elephants or hippos to have floated in. He

began to suspect that the animals had lived in the local area, and that the

hyenas had used the cave as a den and brought in remains of the various animals

they fed on. This hypothesis was supported by the fact that many of the bones

showed signs of having been gnawed prior to fossilisation, and by the presence

of objects which Buckland suspected to be fossilised hyena dung. Further

analysis, including comparison with the dung of modern spotted hyenas living in

menageries, confirmed the identification of the fossilised dung.

His

reconstruction of an ancient ecosystem from detailed analysis of fossil

evidence was admired at the time, and considered to be an example of how

geo-historical research should be done. The minute and painstaking accuracy of

his observation and description of the bones set new standards of scientific

method. The Kirkdale cave discoveries helped to inspire a landmark in the

development of geological study.

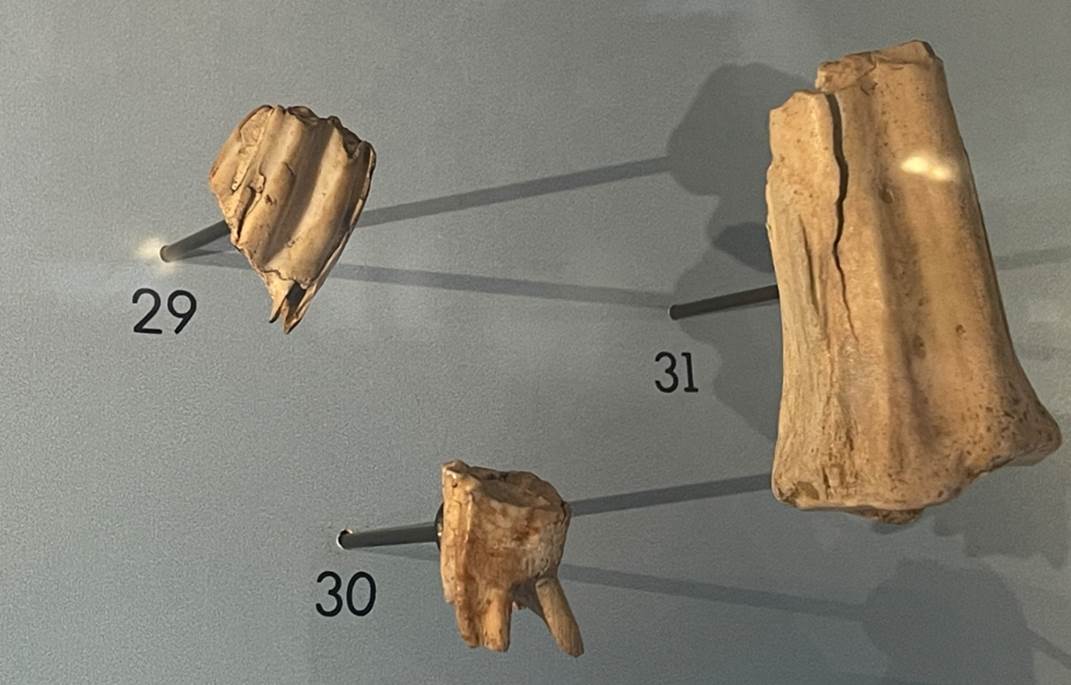

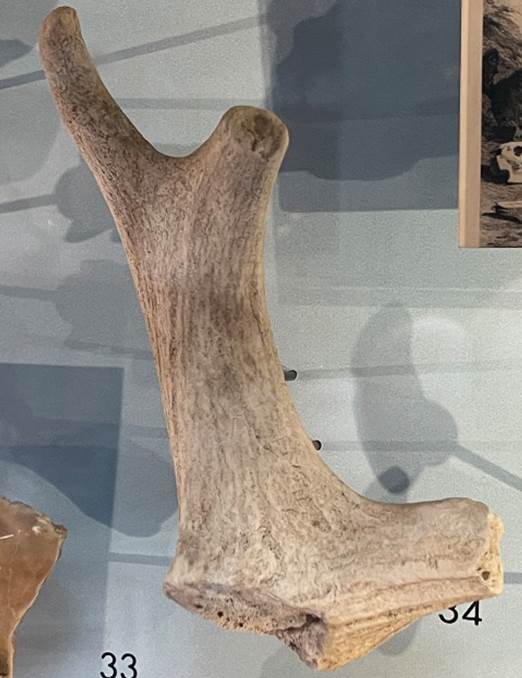

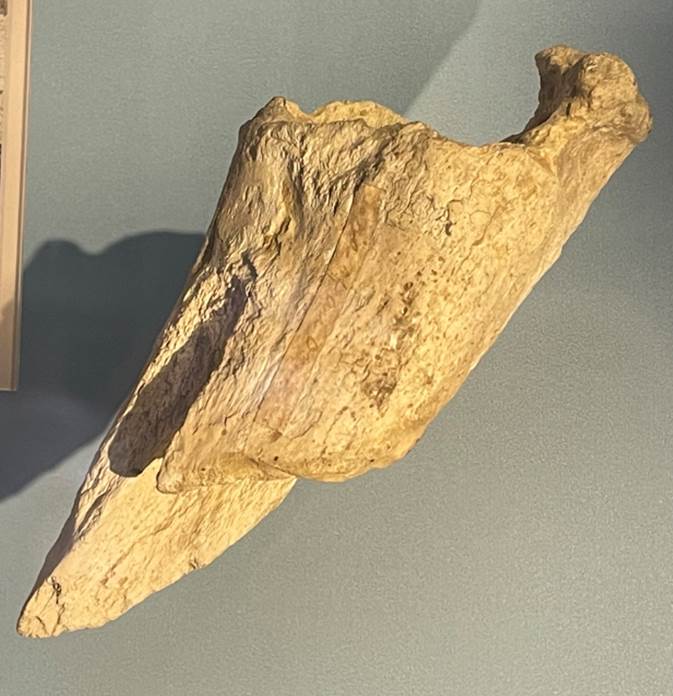

31 – Ox

tibia, Pleistocene, Kirkdale Cave

32 – Deer

tooth, Cervus sp, Pleistocene, Kirkdale Cave

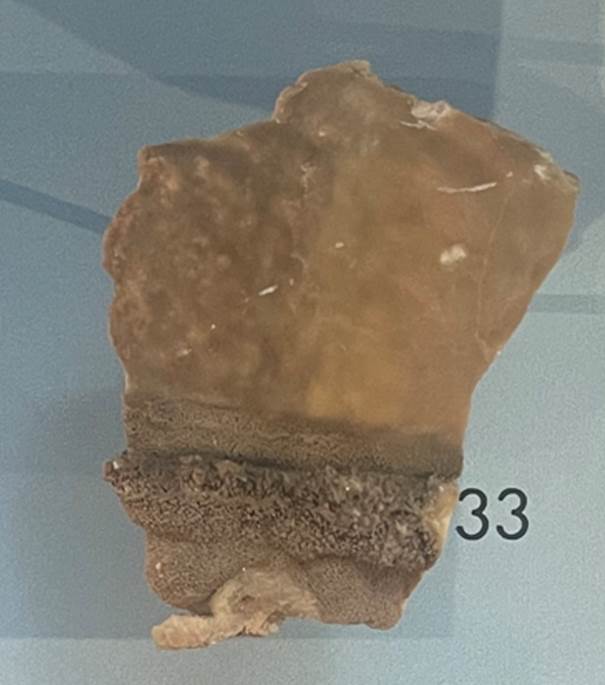

33 – Cave

Earth, Pleistocene, Kirkdale Cave

34 – Red

deer antler, cervus elephus,

Pleistocene, Kirkdale Cave

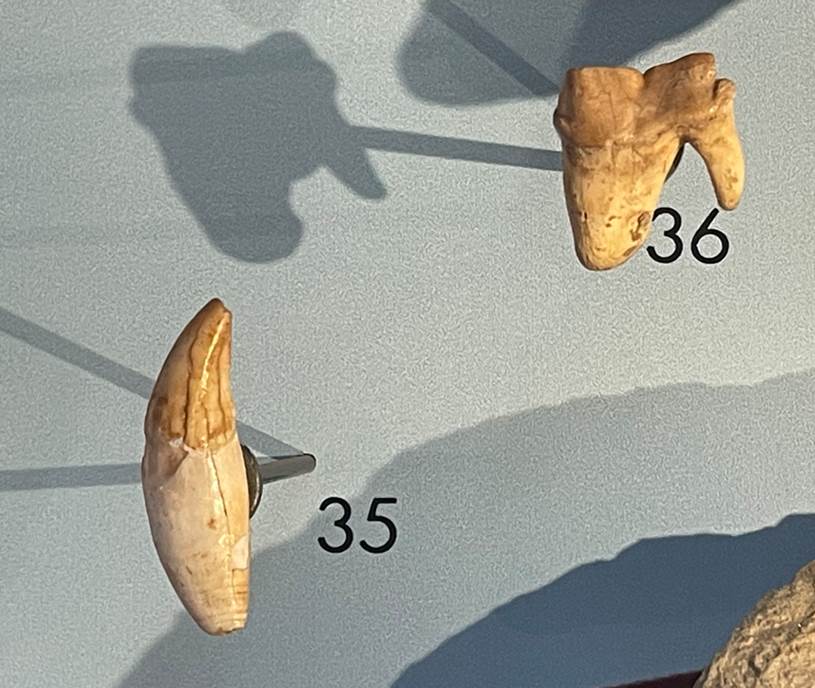

35 –

Hyena tooth, Pleistocene, Kirkdale Cave

36 –

Hyena tooth, Pleistocene, Kirkdale Cave

37 = Bear

tibia, Ursus sp, Pleistocene, Kirkdale Cave

(Kirkdale

fossils displayed at the Scarborough Rotunda Museum)

Enlightenment

Realisation

A few days

before reading his formal paper about his Kirkdale conclusions, Buckland gave a

colourful account at a dinner held by the Geological Society: The hyaenas,

gentlemen, preferred the flesh of elephants, rhinoceros, deer, cows, horses,

etc., but sometimes, unable to procure these, and half starved, they used to

come out of the narrow entrance of their cave in the evening down to the

water's edge of a lake which must once have been there, and so helped

themselves to some of the innumerable water-rats in which the lake abounded.

In 1823 he

published his well received findings in his work Reliquiae

Diluvianae, or “Observations

on the Organic Remains contained in Caves, Fissures and Diluvial Gravel, and on

other Geological Phenomena, Attesting the Action of an Universal Deluge”.

In 1995, the

cave was extended from its original length of 175 metres to 436 metres by

Scarborough Caving Club. A survey was published in Descent

magazine.

All the

bones at Kirkdale were deposited across the cave floor. Later, on a single

occasion, a sediment of mud was introduced. This covered thousands of bone

remains. Perhaps this mud was carried in by a rush of water, which might have

been part of the glacial melt flooding through Newton Dale which caused the

ancient Lake Pickering to reach a depth of 250 metres. Thereafter a gradual

reduction in the depth of Lake Pickering followed over many years, as water

escaped through Kirkham Gorge, to flow towards the Humber Region.

Calcite

deposits overlying the bone-bearing sediments have been dated as 121,000 ± 4000

YBP using uranium-thorium dating. This dates the Kirkdale material to the

Ipswichian or Eemain Interglacial era. This was an

interglacial period which began about 130,000 YBP at the end of the Penultimate

Glacial Period and ended about 115,000 YBP at the beginning of the Last Glacial

Period. The climate then was warmer than it is today, with a higher global sea

level and smaller ice-sheets. During the Last Inter Glacial, polar temperatures

were about 3 to 5 °C higher than today. The global sea level was at least 6.6

metres above present levels and the global surface temperature was about 1 °C

warmer compared to the pre-industrial era.

The

specimens were an original part of the archaeology collection of the Yorkshire

Museum and it is said that "the scientific interest aroused founded the

Yorkshire Philosophical Society".

While

criticised by some, William Buckland's analysis of Kirkland Cave and other bone

caves was widely seen as a model for how careful analysis could be used to

reconstruct the Earth's past, and the Royal Society awarded William Buckland

the Copley Medal in 1822 for his Kirkdale paper. At the presentation the

society's president, Humphry Davy, said: By these inquiries, a distinct

epoch has, as it were, been established in the history of the revolutions of

our globe, a point fixed from which our researches may be pursued through the

immensity of ages, and the records of animate nature, as it were, carried back

to the time of the creation.

There is no

prehistoric evidence of human habitation from the Kirkdale excavations. There

have been local finds of later worked flint. It is possible that there was some

prehistoric ritual landscape in the area and this would be consistent with

later early religious use which often followed at prehistoric ritual sites.

The

discoveries in Kirkdale cave caused a sensation at the time. The fossilised

remains were embedded in a silty layer sandwiched between layers of stalagmite.

Later

discoveries by Buckland

The

energetic Buckland went on to explore twenty further caves in the next two

years, and even imported a hyena to Oxford to observe the habits of killing and

dismembering its prey in order to test his hypotheses.

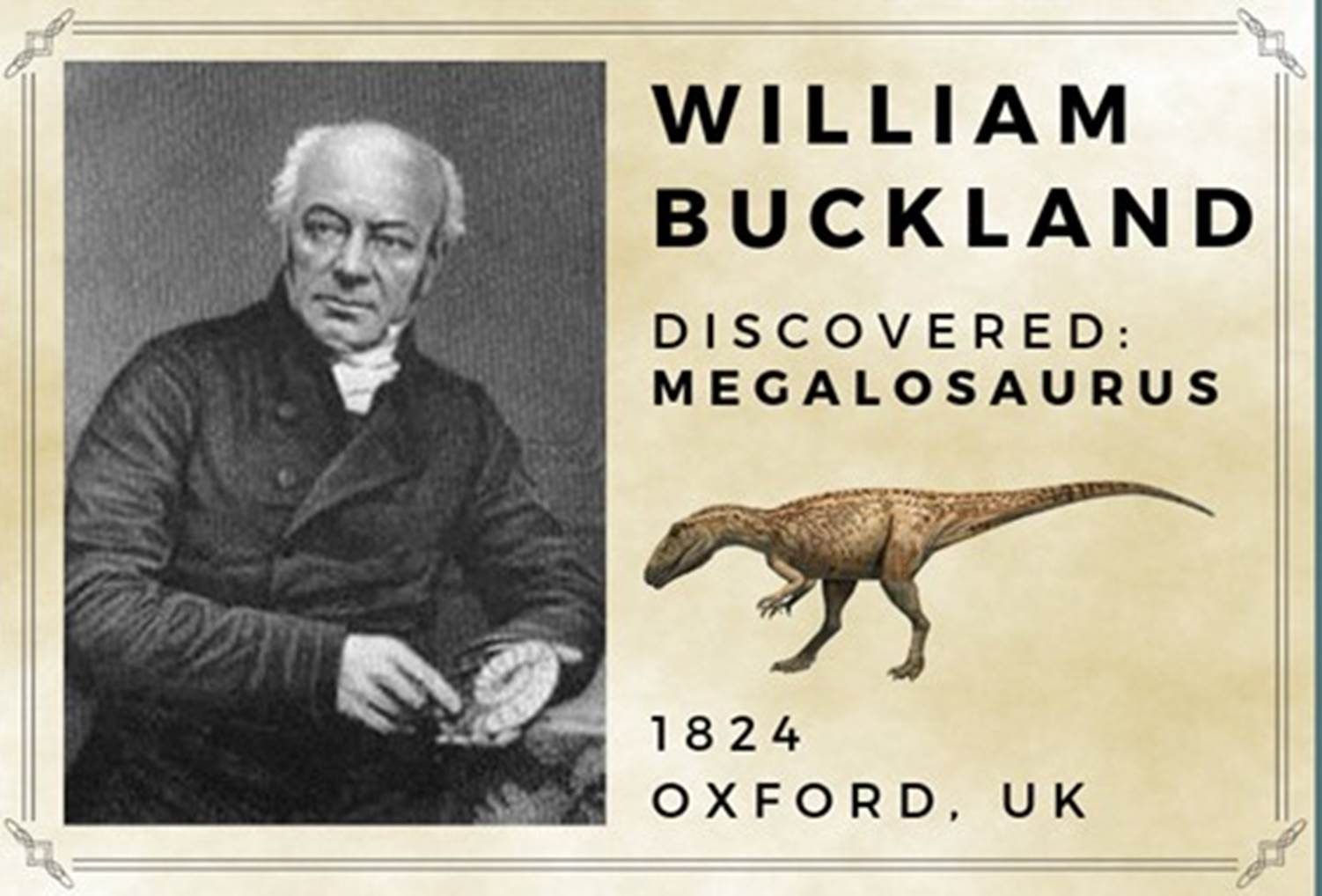

Three years

after his Kirkdale discovery, William Buckland discovered the footprints of a

giant lizard which he called Megalosaurus, but which would later be

called dinosaurs.

William

Buckland also explored and interpreted the Bronze Age Ryedale Windy Pits.

A time

machine

This was before

the age of humans in Britian, but a place of very deep antiquity, and the very

place where our ancestors would later live, in a different period of geological

time.

A vast epoch

of time then passed before the first human settlers following the last great

Ice Age entered Britain across Doggerland, the

lowlands of what is now the North Sea, probably following animals such as

reindeer. The first people arrived in the area of the North Yorks Moors about

10,000 years ago. They were hunters, hunting wild animals across the moors and

in the forests. Relics of this early hunting, gathering and fishing community

have been found as a widespread scattering of flint tools and the barbed flint

flakes used in arrows and spears.

or

Explore the Kirkdale Cave portal to the

past

You will

find a chronology, together with source material on the Kirkdale page.