|

|

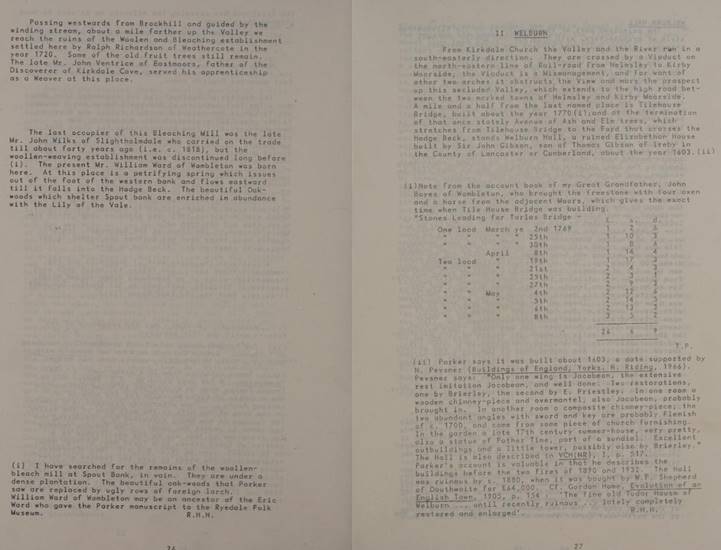

Kirkdale

The history of the church and early history of Kirkdale

|

|

Headlines are in brown.

Dates are in red.

Hyperlinks to other pages are in dark blue.

References and citations are in turquoise.

Context and local history are in purple.

Geographical context is in green.

Introduction

The Saxon Church of Kirkdale is an

exquisite historical jewel which lies about a mile west of Kirkbymoorside,

south of the North York Moors, and overlooks the Hodge Beck. Within the porch

at the entrance door is housed a Yorkshire treasure. It is a Saxon sundial, and

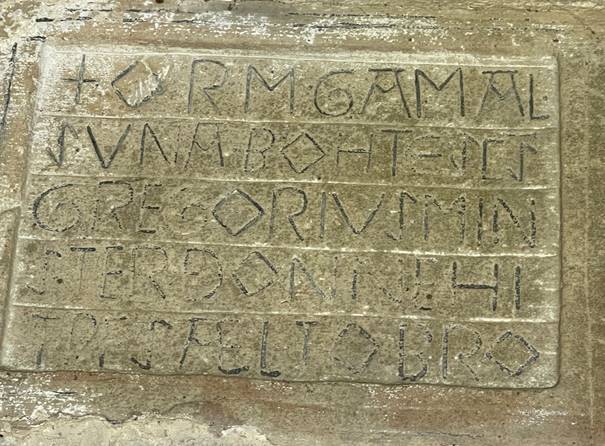

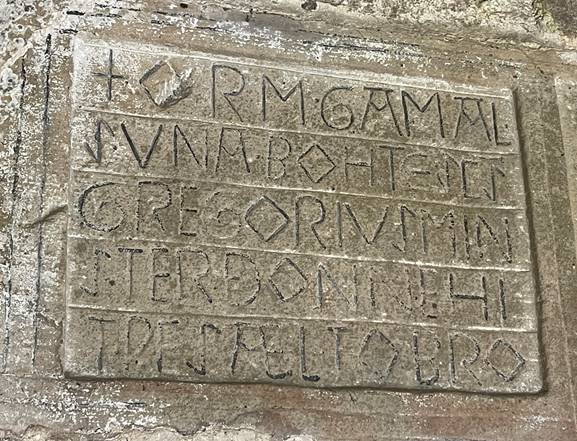

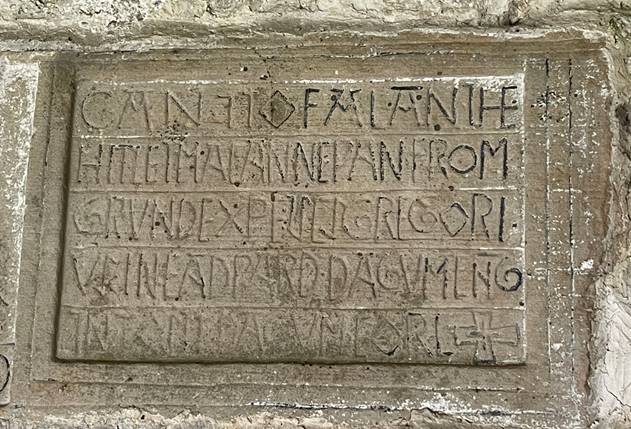

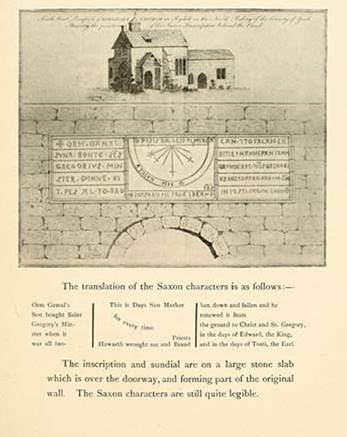

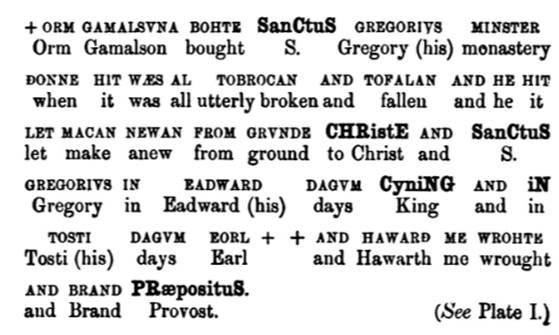

it bears the following inscription:

“Orm the son of Gamel acquired St

Gregory’s Minster when it was completely ruined and collapsed, and he had it

built anew from the ground to Christ and to St Gregory in the days of King

Edward and in the days of Earl Tostig”.

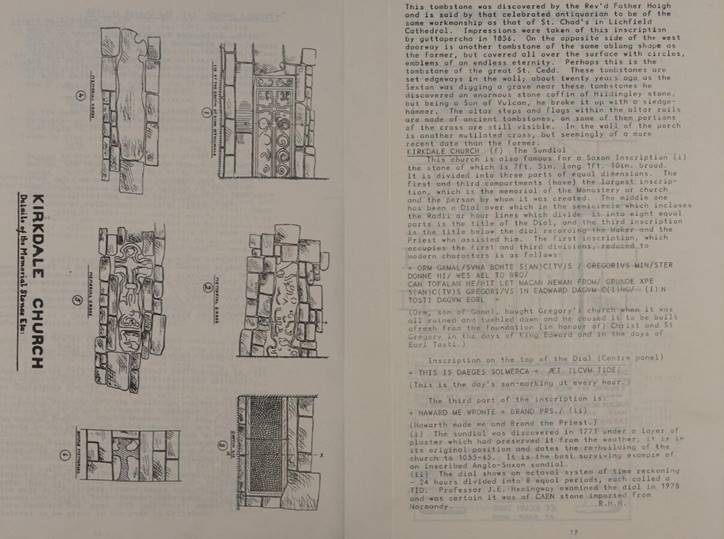

The sundial

itself bears the inscription “This is the day’s sun circle at each hour”

and then “The priest

and Hawarth me wrought and Brand”

One would look far before finding a

place which surpasses Kirkdale for the combination of beauty of setting with

historic and architectural interest. Situated in that belt of limestone which

separates Ryedale from the North Yorkshire Moors, through which the streams

have scoured narrow valleys, Kirkdale can scarcely be seen from any direction

until one is close at hand. The Hodge Beck, rising above Bransdale, flows

southward through a wooded gorge and then, just below the old mill at Hold

Caldron, it enters a subterranean channel, leaving a surface bed to carry the

flood water after heavy rain. The Beck rises again at the spring at Howkeld and eventually rejoins the surface bed near Welburn

Hall. At Kirkdale a ford crosses the bed of the stream; normally dry, in time

of flood it can be covered by up to three feet of water

(St Gregory’s Minster, Kirkdale, Arthur Penn, Parochial Church Council).

Much of the existing church is late

Saxon. Within the church are the remains of grave slabs and crosses of an

earlier period.

Etymology

Kirkdale is variously applied to the church of

St Gregory’s Minster, to the lower part of the valley, and later to the parish (St Gregory’s Minster,

Kirkdale, North Yorkshire, Archaeological Investigations and Historical Context, Philip Rahtz and Lorna

Watts, 2021, 1).

Kirk is an Anglo

Saxon place name which is usually associated with a pre

existing church. Kirk

suggests the existence of a church prior to the ninth century. It has been

suggested that the churches at Kirkdale and Kirkbymoorside might have formerly

belonged to the monastic estate of Lastingham.

The word dale comes

from the Old English word dæl, from which the

word "dell" is also derived. It is also related to Old Norse

word dalr (and the modern Icelandic word dalur), which may perhaps have influenced its

survival in northern England. The Germanic origin is assumed to be *dala-. Dal- in various combinations is common

in placenames in Norway. It is used most frequently in the North of England and

the Southern Uplands of Scotland.

Vale, from the modern

English valley and French vallée are not

related to dale.

The reference to Kirkdale minster

on the sundial is likely the English equivalent of monasterium,

which was not an association with later monasticism, but to more varied types

of religious establishment. So minster does not

particularise the religious purpose of the original building. It doesn’t mean

that it was a monastery, nor a minster in the modern sense.

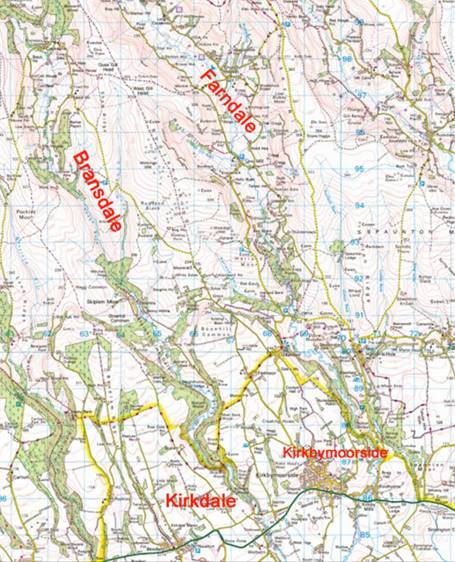

The Geography of Kirkdale

The valley of Kirkdale, which extends

from the larger dale of Bransdale, is one of many north

to south dales along the southern edge of the North York Moors, before these

valleys open out into the rich agricultural land of the Vale of Pickering and

the Vale of York. Kirkdale is the southern extension of Bransdale, which

follows the Hodge Beck. It lies west of the settlement of Kirkbymoorside. To

the south, the River Dove which flows from Farndale

through Kirkbymoorside and the Hodge Beck join at a confluence.

Kirkdale is at the flood plain of the

Hodge Beck, with a long history of downcutting, braiding and terracing. The

flood plain must always have been an attractive focus for settlement, pasture

and arable. The church and churchyard are situated at a wide area before the

dale narrows to pass through a steep valley with a high cliff, to emerge

further south into the Vale of Pickering. (Archaeology

at Kirkdale, Supplement to the Ryedale Historian No 18 (1996 to 1997), Lorna Watts, Jane Grenville and Philip Rahtz, 2). (St

Gregory’s Minster, Kirkdale, North Yorkshire, Archaeological Investigations and

Historical Context, Philip Rahtz and Lorna Watts, 2021, 1).

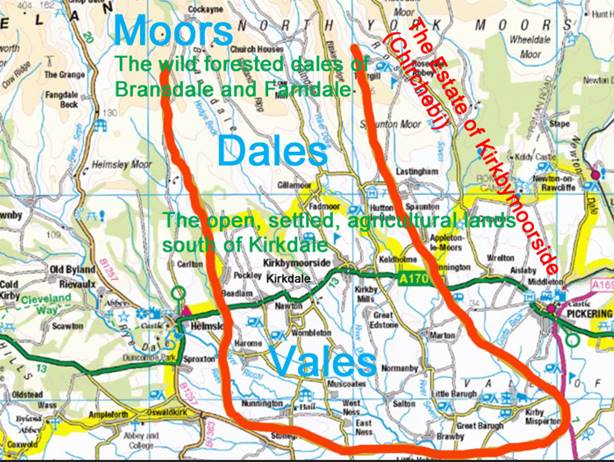

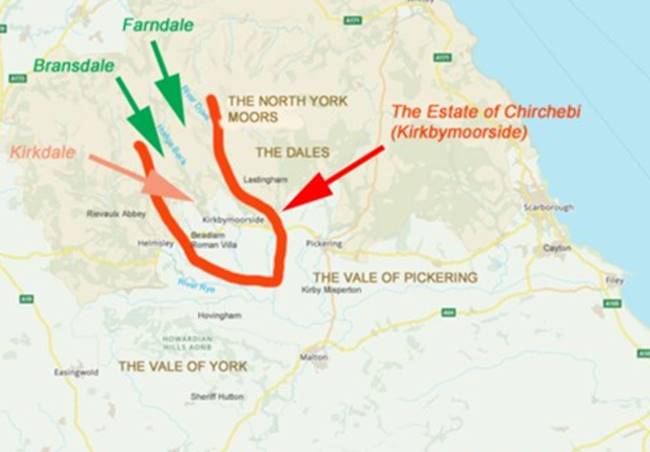

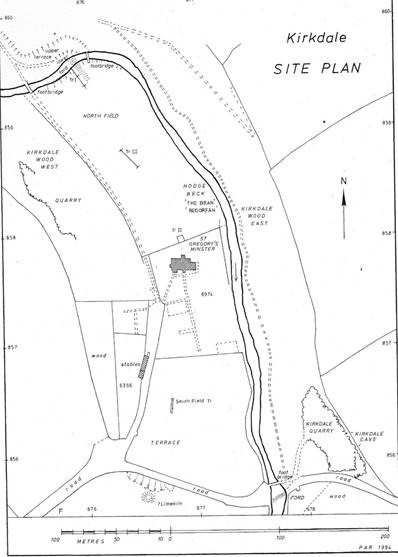

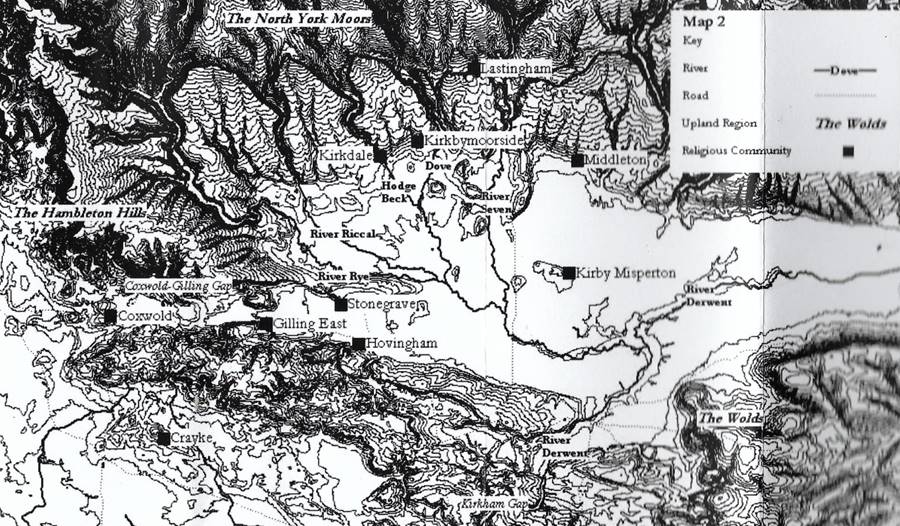

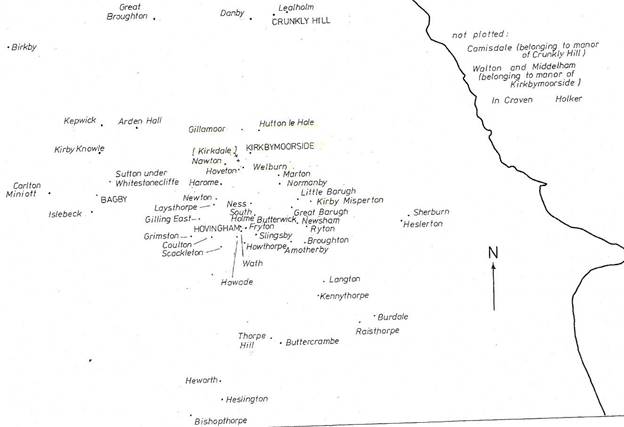

Maps

showing relationship of Kirkdale to Farndale and the lands of the Chirchebi

Estate

The

lands of Kirkdale

To

the north of Kirkdale lie the North Yorkshire Moors, the windswept and barren

heights. Flowing down from the moors, following river courses, are the dales,

relatively steeply sided valleys, with Bransdale following the Hodge Beck and Farndale following the River Dove. The dales

flow down to the wide, flat agricultural lands of two vast vales, the Vale of

York which sweeps south towards York and the Vale of Pickering, temporarily a

prehistoric lake, which flows east towards Pickering and beyond.

The

vales are ancient agricultural lands. The dales beyond the

southern extremities were probably impenetrable and heavily forested for much

of their ancient history. The moors have always been a harsh and bitter

place.

Kirkdale

therefore lies at the edge of the wild lands of the dales and the moors, but at

the northwest corner of vast agricultural lands, at the southern point of the

dales, where there is some protection, and access to stone, mineral and wood

resources, and to hunting opportunities. The church is positioned to avoid

excessive flood damage, but is at a location which has

historically been liable to flooding.

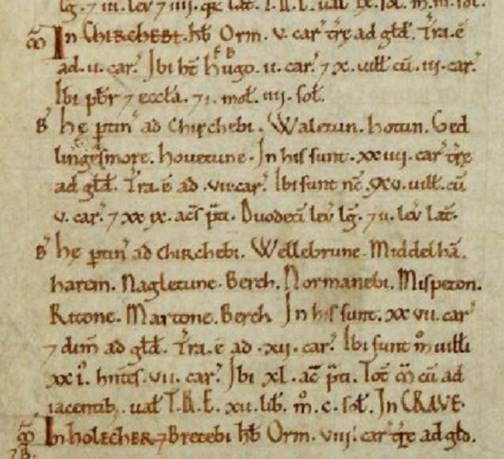

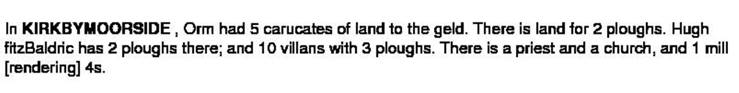

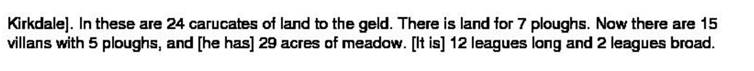

It

is clear from the

Domesday Book

that Kirkdale was at the centre of a section of those vast agricultural lands,

stretching from Kirkby Misperton and Muscoates to the

south to Gillamor at the approach to the dales in the

north. The River Dove and the Hodge Beck flowed out of the dales and through

Kirkdale and Chirchebi (Kirkbymoorside).

Since

Kirkdale cave has revealed animal remains dating to the last interglacial

period (130,000 to 115,000 Years Before Present (“YBP”), this is an

ancient place, where animals have long roamed and where our distant ancestors

later lived and worked, even before historical written records provided more

direct evidence of their presence.

In

time, after the Norman conquest, the new Norman overlords would seek more

agricultural land by probing higher into the dales, as the wooded dales were assarted (“slashed and burned”) to provide

extensions of the farmed land, into Farndale and Bransdale.

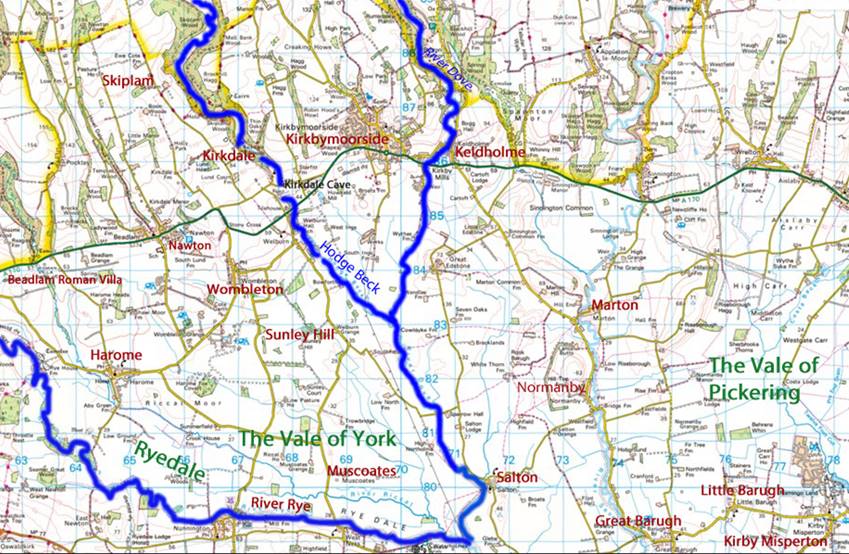

The

main geographical features in the surrounding area include:

·

Hodge Beck which flows

from its source in Bransdale. It has been associated with Redofra

or Redover in the Rievaulx Chartulary.

·

Welburn

which is 1 km south of Kirkdale, and referred to in the Domesday book, where

Roman finds have been discovered.

·

Kirkdale

likely had an important relationship with Kirkbymoorside (Chirchebi) which

developed from a centralised estate centre to a small urban settlement, whose

landowners, by the time of the Norman Conquest and probably prior to that, were

active in York and the wider area.

·

There

was a Roman Villa at Beadlam which might have been part of one estate

including Kirkdale (St Gregory’s Minster, Kirkdale,

North Yorkshire, Archaeological Investigations and Historical Context, Philip Rahtz and Lorna Watts,

2021, 287).

·

Lastingham

lies in a sheltered valley on the edge of scarcely settled moors.

·

Hovingham,

Kirkbymoorside and Kirkdale by the middle

Anglo Saxon period, were secure locations within a wider territory, and within

a network of road and exchange networks.

·

Lower

down the vale, Sherburn

and Kirkby Misperton were at island crossing points within low lying

marshes.

·

Pickering,

Old Malton and Hovingham are likely to

have been the centres of major estates within the wider administrative

framework.

Archaeology at

Kirkdale

Archaeological research at Kirkdale

started in late 1994 focused on the church building itself, above and below

ground, and the fields to the north and the south along the river. The

Kirkdale evaluation project started in 1995. This work continued to 1998, with

further work to the exterior of the church in 2000 and 2014. The excavations

were dug by hand.

The

work was led by Professor Philip

Arthur Rahtz (11 March 1921 – 2 June 2011), founder

of the University of York’s Archaeology Department in 1979, and Lorna Watts.

Much

of the present interpretation depends on the excavation of a small sample of

only about 0.36% of the area around the church.

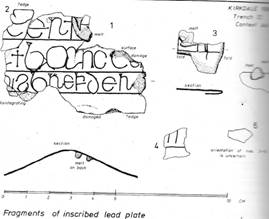

The

excavations were at Kirkdale itself, with three trenches in the North Field –

Trench II at the church boundary wall, Trench III in the middle of the field

and Trench I to the north by the Hodge Beck. There was also an excavation in

the south field.

Archaeological

excavations at Kirkdale

(St Gregory’s Minster, Kirkdale, North Yorkshire,

Archaeological Investigations and Historical Context, Philip Rahtz and Lorna Watts,

2021, 10, 283).

The earlier history of the church is

evidenced by artefacts at Kirkdale dating to as early as the late eighth

century CE:

Close scrutiny

of the surviving fabric of Orm's church reveals three large stone crosses,

much weathered, built into it, two in the outside of the south wall of the nave

and one in the outside of the west wall to the north of the tower.

These are gravestones of Anglo-Scandinavian

design introduced to northern and eastern England by the Danes and Norwegians

who settled here in the late ninth and early tenth centuries. They are most

probably to be dated to the tenth century or early eleventh, and presumably

were gravestones in the cemetery of the church which preceded Orm's rebuilding.

Heather O’Donaghue

(Viking Age Lastingham, Heather O’Donaghue,

Professor of Old Norse at the University of Oxford, 2016) refers to the Christ like figure on the Kirkdale cross, built in to the

wall of the church, having a forked beard, suggesting Scandinavian influence.

It

may seem a little odd to us that builders should use among their materials

gravestones which had been erected in the fairly recent past, especially at a

place where good building stone lies ready to hand:

but the practice was not uncommon in buildings of this period; there is a

nearby parallel, for example, in the church at Middleton between Kirkbymoorside

and Pickering.

There is a cross which was removed from

the west wall of the church and which was once

suggested to have been inscribed Cyning Aethilwald, but which

inscription is now lost. This cross had been the basis of a theory that

Kirkdale rather than Lastingham was the real site of the monastery founded by

St Cedd in the Seventh Century. However the theory is

not generally accepted.

Two elaborate grave covers,

have been called the Cedd Stone and the Ethelwald

Stone. These two tomb-slabs are to be seen

inside the church, under the arcade which separates the nave from the north

aisle.

These too were incorporated into the

fabric at Orm's rebuilding: They were moved to their present position at the

time of the restoration of 1907-09. Scholarly opinion dates these to the

Anglian or pre-Scandinavian period, that is before about 870 CE. One of them

appears to be of the eighth century and the other of the ninth. On the strength

of this dating the history of the church on this site may be taken back to

about 750 CE, conceivably even earlier. For their day they are very handsome

pieces which display craftsmanship of a high order. Furthermore, certain

features of their design strongly suggest that they originally stood inside a

church. These indications show that the persons once buried beneath them were

of significant status and prestige. The church, which originally housed these

tombs, may well have been an imposing one.

One

of these, upon which is a fine cross, was said, a century ago, to bear the

inscription in runic characters, 'Cyning Æthilwald,'

but no writing is now decipherable. This inscription was one of the foundations

of the theory that Kirkdale was the true site of the monastery founded by S.

Cedd in the 7th century.

The

inscription on the sundial makes it clear that the church built by Orm replaced

an earlier one on the site which was, 'completely ruined and collapsed'

when Orm acquired it.

The

earlier church may have been associated with the celebrated early Anglo-Saxon

monastery of Lastingham, only seven miles to the north-east of

Kirkdale. Lastingham was founded by St. Cedd in about 655.

He was a native of Northumbria, a monk and missionary who became the first

bishop of the East Saxons (i.e. Essex) in about 654 and died in 664. He kept up

his links with his native region, and it was in the course of

one of his sojourns in Northumbria after he had become a bishop that he founded

Lastingham. The sort of architecture favoured by Cedd may still be seen at the

imposing, barn-like church of Bradwell-on-Sea in Essex. The monastery at

Lastingham was an important one, and it is by no means impossible that it had

daughter-houses. A nearby and contemporary parallel is Hackness,

founded in 680 CE as the daughter-house of the monastery of Whitby. It is

therefore possible that Kirkdale may have originated as a satellite of

Lastingham.

Since

very early times Kirkdale Church has been known as St. Gregory's Minster, which

implies the existence of a religious house.

It

is dedicated to St. Gregory, the Pope who sent Augustine's mission in 597 CE to

convert the Angli to Christianity.

There

was for a time a certain amount of disagreement between the Roman and

Lindisfarne missions, which was resolved at the Synod of Whitby in 664 CE. St.

Cedd was at Whitby and agreed to the adoption of Roman customs. It may well be

that the dedication of a foundation, established by a Lindisfarne missionary,

to St. Gregory, was a deliberate attempt to foster unity.

Chronological history of Kirkdale to Norman times

The Palaeolithic record,

130,000 to 115,000 YBP

Geological formation

The valley of Kirkdale and Bransdale is the

result of wearing by the river, which in former millennia cut down the land

roughly to the level of the present flood plain at Kirkdale. This flow would

have been interrupted between c 18,000 to 13,000 BCE at the end of the last

glaciation, when drainage from the Vale of Pickering was impeded at the coast.

This resulted in Lake Pickering, which probably extended into tributary valleys

such as Kirkdale. (St Gregory’s Minster,

Kirkdale, North Yorkshire, Archaeological Investigations and Historical Context, Philip Rahtz and Lorna Watts,

2021, 1).

Kirkdale Cave

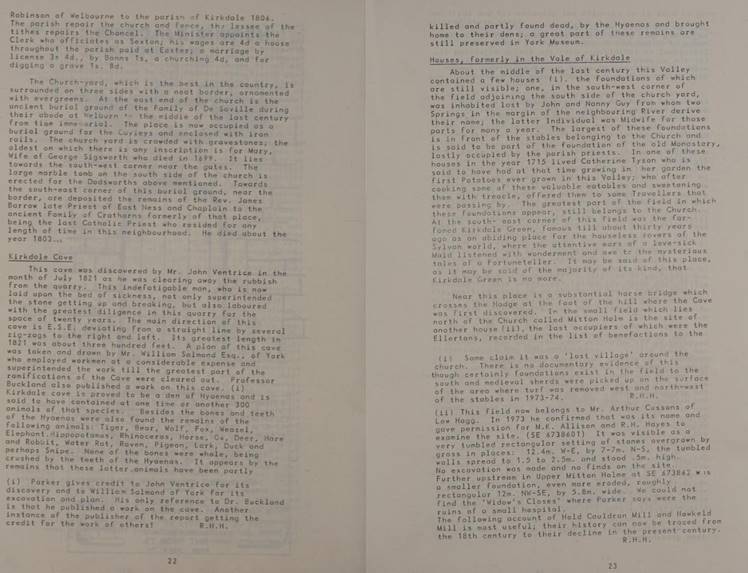

Kirkdale Cave is

a cave and fossil site located in Kirkdale. It was discovered by workmen in

1821 and found to contain the fossilised bones of a variety of mammals no

longer indigenous to Britain, including hippopotami (the farthest north any

such remains have been found), elephants and cave hyenas.

In 1821, a quarry close to the Minster

was being worked for road stone. The quarry men cut through a cave entrance.

They spread stone chippings on the road, not noticing small bones. This cave

was later found to have been covered by many inches

depth of animal bones beneath a layer of dried mud. The local vicar later

spotted the bones and reported his find to the Reverend William Buckland, who

was a professor of minerology and geology at Oxford University. Buckland came

to the site in 1822. The discovery at Kirkdale occurred in the wake of new

forms of stratigraphic dating developed during the Enlightenment. Some of the

fossils were sent to William Clift the curator of the museum of the Royal

College of Surgeons who identified some of the bones as the remains of hyenas

larger than any of the modern species. Buckland later reported to the Royal

Society in London the discovery of:

·

Straight

tusked elephant, rhinoceros, hippopotamus, bison and giant bear finds from the

earlier warmer period; and

·

Mammoth,

woolly rhinoceros, reindeer, horse and sabre tooth tiger remains from the later

cold spells.

Buckland began his investigation

believing that the fossils in the cave were diluvial, that is that they had

been deposited there by a deluge that had washed them from far away, possibly

the Biblical flood.

On further analysis Buckland concluded

that the bones were the remains of animals brought in by hyenas who used it for

a den, and not a result of the Biblical flood floating corpses in from distant

lands, as he had first thought. His reconstruction of an ancient ecosystem from

detailed analysis of fossil evidence was admired at the time, and considered to

be an example of how geo-historical research should be done. The minute and

painstaking accuracy of his observation and description of the bones set new standards

of scientific method. The Kirkdale cave discoveries helped to inspire a

landmark in the development of geological study.

The hyena bones were abundant and

evidenced that hyena had dragged animal parts into the cave to eat them. The

mouth of the cave is not larger than one metre in height, so Buckland concluded

that the varied animal remains were the prey of hyena, dragged into the cave.

He came to realise that the cave had never been open to the surface through its

roof, and that the only entrance was too small for the carcasses of animals as

large as elephants or hippos to have floated in. He began to suspect that the

animals had lived in the local area, and that the hyenas had used the cave as a

den and brought in remains of the various animals they fed on. This hypothesis

was supported by the fact that many of the bones showed signs of having been

gnawed prior to fossilisation, and by the presence of objects which Buckland

suspected to be fossilised hyena dung. Further analysis, including comparison

with the dung of modern spotted hyenas living in menageries, confirmed the

identification of the fossilised dung.

All the bones at Kirkdale were

accumulated across the cave floor and later a sediment of mud was introduced on

a single occasion. This covered thousands of bone

remains. Perhaps this mud was carried in by a rush of water, perhaps from

glacial melt flooding through Newton Dale to lift Lake Pickering to a height of

250 metres. Thereafter a gradual reduction in the depth of Lake Pickering

followed over many years, as water escaped through Kirkham Gorge, to flow

towards the Humber Region.

A humorous cartoon in 1822 depicting

Buckland’s discovery

31 – Ox tibia, Pleistocene, Kirkdale

Cave

32 – Deer tooth, Cervus sp, Pleistocene, Kirkdale Cave

33 – Cave Earth, Pleistocene, Kirkdale

Cave

34 – Red deer antler, cervus elephus,

Pleistocene, Kirkdale Cave

35 – Hyena tooth, Pleistocene, Kirkdale

Cave

36 – Hyena tooth, Pleistocene, Kirkdale

Cave

37 = Bear tibia, Ursus sp, Pleistocene, Kirkdale Cave

(Displayed at the Scarborough Rotunda

Museum)

A few days before reading the formal

paper, he gave the following colourful account at a dinner held by the

Geological Society: The hyaenas, gentlemen, preferred the flesh of

elephants, rhinoceros, deer, cows, horses, etc., but sometimes, unable to

procure these, & half starved, they used to come out of the narrow entrance

of their cave in the evening down to the water's edge of a lake which must once

have been there, & so helped themselves to some of the innumerable

water-rats in wh[ich] the lake abounded.

In 1823 he published his findings to

great critical acclaim in his work Reliquiae Diluvianae; or Observations

on the Organic Remains con rained in Caves, Fissures and Diluvial Gravel, and

on other Geological Phenomena, Attesting the Action of an Universal Deluge.

The cave was extended from its original

length of 175 metres (574 ft) to 436 metres (1,430 ft) by Scarborough Caving

Club in 1995. A survey was published in Descent magazine.

Calcite deposits overlying the

bone-bearing sediments have been dated as 121,000 ± 4000 YBP using

uranium-thorium dating, confirming that the material dates from the Ipswichian

interglacial.

The Eemian or

last interglacial was the interglacial period which began about 130,000 YBP at

the end of the Penultimate Glacial Period and ended about 115,000 YBP at the

beginning of the Last Glacial Period. The

climate then was warmer than today, with a higher global sea level and smaller ice-sheets. During the Last Inter Glacial, polar

temperatures were about 3-5 °C higher than today, the global sea level was at

least 6.6 m above present and the global surface

temperature was about 1 °C warmer compared to the pre-industrial era.

The specimens were an original part of

the archaeology collection of the Yorkshire Museum and

it is said that "the scientific interest aroused founded the Yorkshire

Philosophical Society".

While criticized by some, William

Buckland's analysis of Kirkland Cave and other bone caves was widely seen as a

model for how careful analysis could be used to reconstruct the Earth's past,

and the Royal Society awarded William Buckland the Copley Medal in 1822 for his

Kirkdale paper. At the presentation the society's president, Humphry Davy,

said: by these inquiries, a distinct epoch has, as it were, been established

in the history of the revolutions of our globe: a point fixed from which our researches may be pursued through the immensity of ages, and

the records of animate nature, as it were, carried back to the time of the

creation.

There is no prehistoric evidence of

human habitation from the Kirkdale excavations. There have been local finds of

later worked flint. There is inconclusive evidence of a stone monolith, but if

that is what it was, it could have been transported there in floods. It is

possible that there was some prehistoric ritual landscape in the area and this would be consistent with later early religious

use which often followed at prehistoric ritual sites. All this however is pretty inconclusive.

(St

Gregory’s Minster, Kirkdale, North Yorkshire, Archaeological Investigations and

Historical Context, Philip Rahtz and Lorna Watts, 2021, 284).

The discoveries in Kirkdale cave caused

a sensation at the time. The fossilised remains were embedded in a silty layer

sandwiched between layers of stalagmite. The energetic Buckland went on to

explore twenty further caves in the next two years, and even imported a hyena

to Oxford to observe the habits of killing and dismembering its prey in order to test his hypotheses.

Three years after his Kirkdale

discovery, William Buckland discovered the footprints of a giant lizard which

he called Megalosaurus, but which would later be called dinosaurs.

This was before the age of humans in

Britian, but a place of very deep antiquity, and the very place where our

ancestors would later live, in a different period of geological time.

A vast epoch of time then passed before

the first human settlers following the last great Ice Age entered Britain

across Doggerland, the lowlands of what is now the

North Sea, probably following animals such as reindeer. The first people

arrived in the area of the North Yorks Moors about

10,000 years ago. They were hunters, hunting wild animals across the moors and

in the forests. Relics of this early hunting, gathering and fishing community

have been found as a widespread scattering of flint tools and the barbed flint

flakes used in arrows and spears.

18,000 YBP – The Devensian

Period, the end of the last Ice Age

The Devensian ice sheets created the

natural topography of Yorkshire and Ryedale, which provided a natural landscape

for the dense network of religious communities of the seventh and eight

centuries. This was a landscape of strategic corridors through which royal and

aristocratic patrons competed. The geology of the upland areas directed the

meltwaters through rivers into the lowlands which provide water supplies and

rich alluvial deposits, creating four main regions of the Holderness peninsula,

the Vale of Pickering, the Vale of York and the Humberhead

Levels. The Hodge Beck and the River Dove ran off into the Vale of Pickering to

form Lake Pickering, a pro glacial lake. In time Lake Pickering drained off

into the Derwent, leaving extensive marshland.

Ryedale thus became an area of key

strategic importance. The area became as natural core for agriculture and human

habitation and the Vale of York and the Vale of

Mowbray were well suited to pastoral farming.

(Power,

Religious Patronage and Pastoral Care, Religious communities, mother parishes

and local churches in Ryedale c650 to c1250, Thomas Pickles D Phil Oxon,

Lecturer in Medieval History, The Kirkdale Lecture 2009)

Iron Age

By the late Iron Age, the area was

dominated by the Parisii around Holderness and the Brigantes in the Vale of York.

The Pre

Roman Period

It is clear that within a radius of some

15 to 20 km of Kirkdale there is complex archaeologically derived evidence of

secular and religious activity from at least the pre Roman

period (St Gregory’s Minster, Kirkdale, North Yorkshire,

Archaeological Investigations and Historical Context, Philip Rahtz and Lorna Watts,

2021, 3). This was essentially a rural area, with non

nucleated settlements, with contact between the settlements by north to

south routes through the valleys on the sides of the moors and east to west

through the Vale of Pickering.

Kirkdale is only about 25km north of the

major Roman regional capital, Eboracum (York). Eboracum

(York) would have become increasingly accessible from Kirkdale to the

south during the Roman period, with the construction of new roads.

Thurkilsti

was a pre Roman road from the North York Moors which

passed close to the west side of Kirkdale and on to Welburn,

just south of the Kirkdale ford and to Hovingham where it later joined the Roman roads (St Gregory’s Minster, Kirkdale, North Yorkshire,

Archaeological Investigations and Historical Context, Philip Rahtz and Lorna

Watts, 2021, 3).

During the Roman period, Kirkdale was in

the Roman hinterland. By the late Roman period, Kirkdale was probably part of a

stable, well regulated area

with dispersed settlement, probably dependent on major villa based estates such

as at Beadlam and Hovingham.

The significance of Ryedale was

reinforced by an extensive Roman road network.

·

Wade’s

Causeway ran from Malton across Wheeldale Moor

towards Whitby.

·

A

Roman road ran from Malton to the Vale of York via the Coxwold Gilling gap

where it joined Hambleton Street which stretched from Bernicia to Lincoln.

There have been structures in the area

dating to the Roman period, such as the Roman

villa at Beadlam, only 2 km west of Kirkdale,

discovered in the 1960s. The region around Beadlam was administered from the Roman

town of Isurium Brigantum

(modern Aldborough, near Boroughbridge).

Beadlam probably sat at the centre of a working

estate that provided its owners with an income. Comparable estates show

evidence for arable farming and pasture, the management of woodlands, quarrying

and various industrial activities. Many of the buildings at Beadlam

show evidence of metalworking. Since most of the population of Roman Britain

lived in the countryside, it is likely that sites like Beadlam

would have played an important part of the rural economy and had goods to trade

with larger settlements such as Malton or Aldborough.

Compared to the south of Roman Britain,

the north was largely dominated by the Roman army, most notably the many forts

along Hadrian’s Wall, and evidence of elaborate civilian buildings like Beadlam is quite rare. However, Beadlam

is one of a cluster of potential villa sites in the Vale of Pickering around

Malton, which include Langton, Oulston and Hovingham.

Excavations at each of them have

revealed a rich array of Roman objects, including jewellery, pottery and

expensive glassware, showing that such luxury items were in high demand even at

the farthest extent of the empire. Evidence of occupation at Beadlam before the construction of the villa suggests that

its owners were members of existing elites who had now adopted a Roman

lifestyle. It was quite common in Yorkshire and across Roman Britain for Iron

Age farmsteads to be developed with a Roman-style building. Other possible

owners could have been retired soldiers who had been rewarded with land for

their service, absentee landowners living elsewhere in the empire, or even the

Roman emperor himself, who owned various estates in the province of Britannia.

The villa complex was probably

constructed in about 300 CE and was occupied until about 400 CE, just before

the end of Roman Britain. The villa at Beadlam had

about 30 rooms, which were spread across three ranges built around a large

courtyard. The northern range, the only one visible today, is a typical

Romano-British winged-corridor house. This house comprised communal rooms in

the centre and two private suites of well-appointed rooms on either side,

connected by a long veranda.

The western suite included a room with a

heating system (hypocaust) and in the east suite there was an elaborate

reception room with a fine mosaic. It may be that these suites were

self-contained and belonged to different households, who shared the use of the

other rooms. A similar house lay just west of the courtyard and may have been

occupied by another household. On the eastern side were further buildings that

seem to have been used for industrial or agricultural processes.

It seems likely that there may have been

some religious site at Kirkdale in the late Roman period, whether pagan or

Christian or an amalgam of both. There is evidence of an early burial

(including an infant) to the north east of the church

at “Trench NB”. The first recognised structural phase is “Foundation P” at the

north exterior of the church, which used blocks which might have been from the

fully Roman period (or might have been reused) and might have been part of a

detached structure, such as a funerary building or mausoleum. It is not clear

whether late Roman Christianity might have reached Kirkdale. It was evident in York and it was arguably present in the excavations at the

nearby Beadlam villa, but this remains uncertain.

Hovingham was a much more significant Roman

villa, perhaps on a palatial scale, nearly 10km southwest from Kirkdale, and it

could have had very extensive holdings, which could have embraced a wider

estate including Beadlam and Kirkdale.

Lastingham might have had a Roman predecessor to

the later monastery, possibly a nymphaeum.

Villas at Appleton

le Street, Blandsby Park and Langton indicate that Ryedale

was a major agricultural producer in the Roman period. The landscape of the

Vale of Pickering was likely well settled, and this might have extended into

the rural hinterland. Agricultural produce would have been required at

significant scale to support the northern Roman army.

In the Roman period, the area around

Kirkdale probably included a small number of dominant settlements in this area

of rural hinterland. The population would have been within the military and

administrative orbits of the Roman interests.

(St

Gregory’s Minster, Kirkdale, North Yorkshire, Archaeological Investigations and

Historical Context, Philip Rahtz and Lorna Watts, 2021, 284 to 288).

A pre

Christian past?

C L R Tudor, a Brief

Account of Kirkdale Church with Plans, Elevations, Sections, Details and

Perspective Views (London 1876) suggested

that Kirkdale’s Christian association did not mark

the beginning of the site’s importance. He wondered about its possible

association as a Druid site. In support of a longer history, many commentators

have remarked on the quietness, beauty and timelessness of the site.

The adjacent stream, Hodge Beck, long

referred to by its primitive Welsh name Redofram

or stream, has a distinctive characteristic. In dry weather it ceases to flow

above ground and uses underground channels of fissured limestone. This occurs

either side of the present church, between the mill above the church where the

water goes underground and the church at Welburn where it reemerges. Madge Allison, a local

archaeologist, had recognised the importance of this, citing J G Frazer’s The Golden Bough,

as something unusual that would promote a reaction to the landscape, in its

variable physical setting of the beck. The spectacle of the waters of the Hodge

Beck on either side of the site of the later Church, which are periodically

lost to sight, provides a suitable location for pre Christian

phenomenological experience. The Hodge Beck was not the only example of

disappearing water, with similar occurrences at Lastingham. Underground

openings might have been used to communicate via discolouration by means of

dyes and meetings might have been timed to coincide with water flow changes.

The location of Kirkdale is both

accessible, whilst not obvious. It could be accessed by long distance

routeways, but its location was aside and at the edge of the more populated

vales.

If there were pre

Christian practices at Kirkdale, then the shift from pre Christian to

Christian might have been a more natural one.

(St

Gregory’s Minster, Kirkdale, North Yorkshire, Archaeological Investigations and

Historical Context, Philip Rahtz and Lorna Watts,

2021, 306).

Fifth Century CE

The late c 4th and c 5th

transitional period after the end of Roman rule, provides limited

archaeological evidence. It is likely that settlement was very localised.

What happened to the Roman estates and

populations around Kirkdale in the post Roman period is uncertain, but the

interests of some of the dominant landholders probably continued. The nature of

lordship in the area around Kirkdale was not overtly Anglo Saxon. There is an

absence of obviously culturally Anglo Saxon grave

goods. In might be surmised that the population in the area remained more

indigenous, at least for a while, rather than immediately overwhelmed by the

Angloi Saxon incomers. Over time however, the population would have gradually

assumed a new mixed Anglo Saxon identity.

At Beadlam, a large number

of coins date to the later fourth century CE and might reflect locally

secure conditions after the Romans had left. Beadlam

seems to have continued as an important supplier of grain, as evidenced by the

presence of a grain dryer. Beadlam’s material culture

suggests continued post Roman activity. It cannot be said with any certainty

that Kirkdale had any association with Beadlam, but

its proximity might suggest its continued importance during this little known period.

The Kingdom of Deira emerged from the

mid fifth century and Bede’s Historia Ecclesia suggests that there was a

gradual consolidation of small controlling groups.

The absence of hillforts and the non defensive nature of places like Hovingham raise questions about how control was physically

maintained during this period.

(St

Gregory’s Minster, Kirkdale, North Yorkshire, Archaeological Investigations and

Historical Context, Philip Rahtz and Lorna Watts, 2021, 288 to 289).

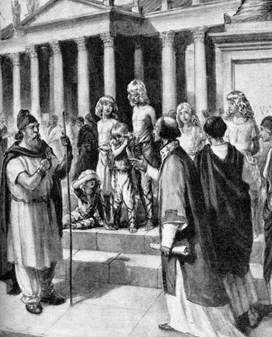

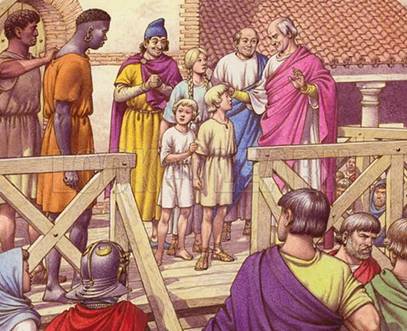

The

historian Procopius (500 to 565 CE) described the people of Brittia

as Angiloi to Pope Gregory the Great. Gregory

had seen fair haired slaves for sale and replied that they were not Angles,

but angels. His pun is sometimes taken to define the origin of the English

and Gregory continued to class them as a single peoples.

It

is significant that Bede described the incident as Gregory’s encounter with a Deiran boy in Rome about to be sold into slavery. Kirkdale

lay firmly in the Kingdom of Deira.

Bede's Ecclesiastical History of England, Book II, Chapter 1:

Nor must we pass by in silence the story of the blessed Gregory, handed down

to us by the tradition of our ancestors, which explains his earnest care for

the salvation of our nation. It is said that one day, when some merchants had

lately arrived at Rome, many things were exposed for sale in the market place, and much people resorted thither to buy:

Gregory himself went with the rest, and saw among other wares some boys put up

for sale, of fair complexion, with pleasing countenances, and very beautiful

hair. When he beheld them, he asked, it is said, from what region or country

they were brought? and was told, from the island of Britain, and that

the inhabitants were like that in appearance. He again inquired whether those

islanders were Christians, or still involved in the errors of paganism, and was

informed that they were pagans. Then fetching a deep sigh from the bottom of

his heart, “Alas! what pity,” said he, “that the author of darkness should own

men of such fair countenances; and that with such grace of outward form, their

minds should be void of inward grace.” He therefore again asked, what was the

name of that nation? and was answered, that they were called Angles.

“Right,” said he, “for they have an angelic face, and it is meet that

such should be co-heirs with the Angels in heaven. What is the name of

the province from which they are brought?” It was replied,

that the natives of that province were called Deiri.

“Truly are they De ira,” said he, “saved from

wrath, and called to the mercy of Christ. How is the king of that province

called?” They told him his name was Aelli; and

he, playing upon the name, said, “Allelujah,

the praise of God the Creator must be sung in those parts.”

So

three puns from this story give us some historical perspective:

·

An

Angle from Deira was the inspiration for the nation of England.

·

A

pun on Deira itself, de ira, ‘of anger’ were

an inspiration on Gregory, in Bede’s image, that the Deirans

had been saved from wrath.

·

King

Aelli of Deira was the King who inspired the word Allelujah.

Kirkdale

finds itself firmly within the ambit of England’s origin story, being a

significant place within the lands of Deira, and the place of a church which

soon afterwards was dedicated to Pope Gregory.

By

the late sixth century, groups now referred to as the Anglo Saxons were gaining

control over the land, including at Lastingham.

597 CE

Pope

Gregory sent Augustine, Prior of a Roman monastery, to Kent on an ambassadorial

and religious mission to convert the Angli,

and he was welcomed by King Aethelberht.

The

English church would come to own a quarter of cultivated land in England and

reintroduce literacy at least amongst the Church. English identity began in a

religious concept. Hence there grew a single and distinct English church. It

adopted Roman practices in its dogma and liturgy (as later confirmed at the

Synod of Whitby in 663 CE), but it venerated English saints and developed its

own character.

604 CE

St

Gregory (540 to 604 CE) died on 12 March 604. He was the bishop of Rome from 3

September 590 to his death. He is known for instituting the first recorded

large-scale mission from Rome, the Gregorian mission, to convert the then

largely pagan Anglo-Saxons to Christianity. Gregory is also well known for his

writings, which were more prolific than those of any of his predecessors as

pope. Gregory was more inclined to remain retired into the monastic lifestyle

of contemplation. The mainstream form of Western plainchant, standardised in

the late 9th century, was attributed to Pope Gregory I and so took the name of

Gregorian chant.

627 CE

By

the early seventh century CE, there was an incipient state structure under King

Edwin of Deira’s peripatetic government, which held gatherings on estates where

food renderings were consumed. Deira’s land was between the Humber and the

Tees. York was an important centre. Edwin

converted to the Christian religion, along with his nobles and many of his

subjects, in 627 and was baptised at Eoforwic (York) and he built the first wooden church amidst the Roman

ruins which was later replaced by a larger stone church.

The first recorded church at York was a wooden structure built

hurriedly in 627 to provide a place to baptise Edwin, King of Northumbria. The

location of this church, and its pre-1080 successors, is unknown. It was

probably in or beside the old Roman principia (the military

headquarters), which may have been used by the king when in residence in York.

Archaeological evidence indicates the principia was located partly

beneath the post-1080 Minister site, but excavations undertaken in 1967-73

found no remains of the pre-1080 churches. It can therefore be inferred that

Edwin's church, and its immediate successors, was near the current Minster

(possibly to the north, underneath the modern Dean's Park) but not directly on

the same site.

633 CE

Edwin died and overall control of the Kingdom

of Northumbria passed to the northern Kingdom of Bernicia.

655 CE

The

Battle

of the Winwead was fought on 15 November 655 between

King Penda of Mercia and Oswiu of Bernicia, ending in the Mercians' defeat and

Penda's death. According to Bede, the battle marked the effective demise of

Anglo-Saxon paganism. It marked a temporary Northumbrian ascendency.

There

followed religious foundations in Deira after the Battle of Winwead

in the Vale of Pickering and in the area

between York and Whitby, which appear to have included Lastingham, Kirkdale, Coxwold, Hovingham and Kirby Misperton.

657 CE

Whitby

continued to have an ongoing importance as a port, which was enhanced by the

foundation of a monastery there. The first monastery was founded in 657 CE by

the Anglo-Saxon King of Northumbria, Oswiu (Oswy).

The monastery at

Lastingham

Bede,

in his History of the English Church and People (731

CE), recorded

a small monastic community was founded at Lastingham (some 10km northeast of Kirkdale) under

royal patronage, partly to prepare an eventual burial place for Æthelwald, Christian king of Deira, partly to assert the

presence and lordship of Christ in a trackless moorland wilderness haunted by

wild beasts and outlaws.

663 CE

The Synod of Whitby

Aidan

had come to Northumbria from Iona, bringing with him a set of practices that

are known as the Celtic Rite. As well as superficial differences over the computus (calculation of the date of Easter), and

the “cut of the tonsure” (the practice of cutting or shaving some or all of the hair on the scalp as a sign of religious devotion

or humility), these involved a pattern of Church organisation fundamentally

different from the diocesan structure that was evolving on the continent of

Europe. Activity was based in monasteries, which supported peripatetic

missionary bishops. There was a strong emphasis on personal asceticism, on

Biblical exegesis, and on eschatology. Aidan was well known for his personal

austerity and disregard for the trappings of wealth and power. Bede several

times stresses that Cedd and Chad absorbed his example and traditions. Bede

tells us that Chad and many other Northumbrians went to study with the Irish

after the death of Aidan.

Lastingham

had been founded in the Lindisfarne/Iona/Celtic tradition.

There

was for a time some disagreement between the Roman and Lindisfarne missions.

This caused conflict within the church until the issue was resolved at the Synod of Whitby in 663 by Oswiu of Northumbria opting

to adopt the Roman system.

The

schism had come about because the church in the south were tied to Rome, but

the northern church had become increasingly influenced by the doctrines from

Iona. The Synod was held in the monastery at Streoneschalch

near to Whitby.

St

Cedd was at Whitby and agreed to the adoption of Roman customs.

A

scribe, probably Bede, who recorded the events of the Synod of Whitby

685 CE

Whilst there may have been

some continued subdivision of the local area into great estates, the locality

of Kirkdale at this time was in well regulated and well used landscape. The

Vale of Pickering was a self contained

area, off centre to the main north south route through York, but accessible to

the North Sea. Hovingham continued to be an administrative centre. Kirkdale was

therefore well protected from the more troublesome border areas and a suitable

place for agricultural and religious prosperity. Kirkdale is unusual in being a

settlement which has not been subject to constant renewal. (St Gregory’s Minster, Kirkdale, North Yorkshire,

Archaeological Investigations and Historical Context, Philip Rahtz and Lorna Watts,

2021, 290).

Foundation

of Kirkdale

The circumstances under

which a church of the Anglo Saxon period was

established at Kirkdale are unknown. By about 685 CE, it seems likely that the

early church at Kirkdale was dedicated to St Gregory, Pope Gregory who sent

Augustine’s mission to England in 597 CE.

The Church might have been

established at the time of the establishment of a new cemetery or there may

have been an existing burial practice, so far undetected by archaeology. The

preferred model is that the initial use was of a church only, without an associated

monastery. The natural resources in the immediate vicinity and risk of flooding

was probably not favourable to a permanent monastery

settlement.

It is most likely that the

sponsors of the new church were from the social elite

and they probably lived elsewhere, probably in Kirkbymoorside.

Ongoing connections with

Lastingham may have changed over time.

Dedication to St Gregory was

unusual. There appear to have been strong links between the Deirans

and Pope Gregory.

It is significant that

Bede reported Gregory’s encounter with a Deiran boy

in Rome, about to be sold into slavery and is said to have referred to his

nationality as Angli, in his word play with

angels; his word play with De Ira; and its King

Aella’s association with Alleluia. This suggests some linkage between Deira and

the Deiran king and Pope Gregory.

The

Gregorian link extends further to associations with the royal dead of Deira and

Gregory. When King Edwin of Deira fell at the Battle

of Hatfield Chase

on 12 October 633 about 8 miles north of Doncaster, which marked the effective

end of Deiran kingship, Edwin was temporarily placed

in a porticus or chapel dedicated to St Gregory in York (later completed

by his successor Oswald) and his body was then moved to be finally buried at

Whitby again in a porticus dedicated to Gregory. Philip

Ratz et al have speculated that as the journey from York to Whitby would

have taken more than a day, and as Kirkdale is at about the mid

way point, it is possible that his body lay there temporarily. There is

no surviving evidence of this. It might be implied from a mid

eleventh century dedication stone. It is possible therefore that there

may have been some association with St Gregory from as early as 633 CE.

Another link with St

Gregory is that Cedd, the founder of Lastingham was described by Bede to have

baptised the king of East Anglia at Rendelsham in a

church also dedicated to St Gregory. This might also reinforce some linkage

between Cedd and Lastingham and Kirkdale.

Dedication to St Gregory

might link Kirkdale to a period of general conversion in the area from about

569 CE and might also have emphasised the direction of the English church’s

association with Rome after the Synod of Whitby in 663 CE.

There

is a possible association of Kirkdale with Cornu Vallis, the horned

valley, a name which suggests some association with cattle in the distant past.

Augustine’s mission was likely to have included instruction from Gregory to

deal with pagan shrines. This might suggest a possibility that Kirkdale was

already a known meeting place. Cornu Vallis is referred to as a place

where Abbot Ceolfrith

of Monkwearmouth-Jarrow visited in 716 CE, and this might suggests

links between Kirkdale and the Tyne valley and Jarrow. Ceolfrith had been

a monk at Gilling and Ripon, and had an association

with the area.

(St Gregory’s

Minster, Kirkdale, North Yorkshire, Archaeological Investigations and

Historical Context, Philip Rahtz and Lorna Watts, 2021, 292 to 293).

Ceolfrith was born around 642 CE in Northumbria.

He became a monk at the monastery of St. Peter’s, Wearmouth. In 674 CE, Ceolfrith founded the twin monasteries of Wearmouth and

Jarrow (which have also been associated with Cornu Vallis) along the River Wear

in Northumbria. These monasteries became centres of learning, culture, and

religious devotion.

Cornu Vallis has also been

associated with Hornsea on the East Coast of Yorkshire, Spurn Head and with

Bass Rock on the Firth of Forth. The

exact location of Cornu Vallis remains debated. Cornu Vallis played a role in Ceolfrith’s journey in Anglo-Saxon Northumbria. Bede’s

abbot Ceolfrith (also known as Ceolfrid)

travelled to a place called Cornu Vallis, which some scholars believe could

have been Kirkdale. The Latin name “Cornu Vallis” may reference the horn-shaped

valley, aligning with the topography of Kirkdale.

The

Life of Ceolfrith by an Anonymous Monk of Jarrow

of the Eighth Century,

chapter XXIX, tells of the appointment of Hwartbert

as abbot of Monkwearmouth Jarrow, who wrote a letter which he sent with gifts

to Ceolfrith who was found at Aelfberht’s

monastery, which is situated at a place called Cornu Vallis. The notes suggest

that Ceolfrith had ridden south towards the mouth of

the Humber.

The creation of a church

at Kirkdale has been attributed to the Laestingas, an

elite sub group of the Deirans,

potentially associated with a larger area than Lastingham itself.

T Pickles,

Power, Religious Patronage and Pastoral Care: Religious Communities, Mother

Parishes and Local Churches in Ryedale, c. 650-c. 1250, The Kirkdale Lecture,

2009 (York: Trustees of the Friends of St Gregory’s Minster,

Kirkdale, 2009), at 25-6 has noted the overlapping jurisdiction of the

parishes of Lastingham, Kirbymoorside, Kirby

Misperton and Kirkdale, suggest that the much larger territory of the Laestingas, and the original parish of Lastingham,

had been divided subsequently into several smaller areas.

Kirkdale

and Lastingham are about 6 km apart and have long been closely associated.

It

is likely that Kirkdale also had a close relationship with Kirkbymoorside (Chirchebi).

Physically Kirkdale

was more similar to Kirkbymoorside than Lastingham.

Kirkbymoorside was slightly better placed in terms of water supply, protection

from flooding, land based resources and higher

surveillance points, which made it more suitable as a central place. By the

late eighth century, a coin find suggests that it was sharing in the monetary

economy which has been evidenced between Whitby

and the Humber.

It may well be that these relationships

were more fluid and not fixed.

(St Gregory’s Minster, Kirkdale, North Yorkshire,

Archaeological Investigations and Historical Context, Philip Rahtz and Lorna Watts,

2021, 290 to 292).

St

Gregory’s Minster, Kirkdale, Arthur Penn, Parochial Church Council surmises that the church might have

been built in around 654 CE, but that theory rests on the unlikely premise that

Kirkdale was the place of the Lastingham monastery. However, as the church was

dedicated to St Gregory, likely to have been a deliberate attempt to foster

unity following the Synod of Whitby, it seems likely to have been founded in

the years following the Synod say around 665 CE. Cedd had died in 664 CE.

Perhaps the church was founded by his successor and younger brother Chad.

It is possible that the site marks an

early Anglo Saxon monastery, of which the Church is

the surviving part (Archaeology at Kirkdale,

Supplement to the Ryedale Historian No 18 (1996 to 1997), Lorna Watts, Jane Grenville and Philip Rahtz, 1), though the use of minister does

not necessarily mean that is the case.

More recent excavations

tend to suggest that the church at Kirkdale was important.

There is a local legend

that the original intention was to build the church near Nawton and Wombleton, but a stone, chosen to mark the

spot, was mysteriously found the next morning in Kirkdale. It was moved back to

the intended site, but once again returned to the dale. So

the church was built there. The story was later recorded in the diary of a

schoolmaster of Appleton le Moors, F C

Dawson, in his entry after a visit to Kirkdale on 14 June 1843.

The original

parish churches emerged at about this time. A parish was a district that

supported a church by payment of tithes in return for spiritual services. Some

churches were linked to manor houses and others originated as the districts of

missioning monasteries. The church at Whitby was near a major settlement,

whilst the church of St Gregory’s at Kirkdale was located remotely in a dale.

By 1145, Kirkdale was described as the church of Welburn. Recent excavations

tend to confirm the view that an important church was at Kirkdale (John Rushton, The History of Ryedale, 2003, 19).

In contrast to the

trackless moorland wilderness haunted by wild beasts and outlaws where

Lastingham was built, in Kirkdale, an ancient route from north to south

descended out of Bransdale to form a crossroads with an ancient route from west

to east along the southern edge of the moors. Travellers needed shelter,

medical attention and perhaps spiritual sustenance. It may well have been to

provide these Christian ministrations and to teach the gospel in the region

that a small community of monks or a priest was established there as a minster

dedicated to Gregory the Great, as an English Apostle. The two finely decorated

stone tomb covers, generally agreed to date from the eighth century, hint that

this early church had wealthy patrons, perhaps royal patrons.

So we don't know exactly when the first

church was built at Kirkdale. It may have been a daughter house of the monastic

community at nearby Lastingham, which was founded in AD 659. The first church

at Kirkdale was a minster, or mother church for the region. It may have

included a chancel, a rarity for Anglo-Saxon churches.

The Friends of

St Gregory's Minster Kirkdale suggest

that at least one of the 8th century patrons may have been venerated

locally as a saint.

The three

fragments of Anglo-Saxon cross shafts built into the church walls date to the

9th and 10th centuries.

Pope Gregory had

encouraged the conversion of pagan holy places to Christianity and the church

at Kirkbymoorside is near a large burial mound.

It is assumed in the early

Anglo Saxon period, that all land was ultimately held

by the King, but was gradually dispersed, but by the ninth century CE the land

was held by a broader elite, as the political structure gradually changed.

Kirkdale was probably sponsored by the social elite. A structure on the north east side of the church may have been associated with

burial and there may have been sequences of burial and building. (St Gregory’s Minster,

Kirkdale, North Yorkshire, Archaeological Investigations and Historical Context, Philip Rahtz and Lorna

Watts, 2021, 283).

The scale of building at

Kirkdale is evidence of robust economic activity that could be relied upon by

its benefactors. This would have required the sourcing of stone and its

transportation on viable routeways, its cutting to the required sizes, the tools

to do this, and the manufacture of wood for scaffolding and mortar. This could

have been achieved by central control, but probably involved a variety of

landowners, at least to some degree.

It is likely that there

were different interrelationships across Ryedale and beyond. The sculpture

suggests that there might have been an association with Lastingham and

Hovingham as important ‘saint rich’ centres, although it is possible to

interpret Kirkdale sculpture as rivalry. It is also likely that there were

allegiances and links with Cornu Vallis and perhaps with Monkwearmouth

and Jarrow, which might have bridged several generations.

(St Gregory’s Minster, Kirkdale, North Yorkshire,

Archaeological Investigations and Historical Context, Philip Rahtz and Lorna Watts,

2021, 296 to 297).

This was perhaps the time

when the Old English Beowulf was told orally as an

epic poem.

750 CE

By 750 CE there was a

reference to the pope involving land distribution relative to Stonegrave, Coxwold and Donemuthe

(probably on the Tyne), which involved the Archbishop of York and his brothers,

one of whom was the king of Northumbria. It is likely that Kirkdale would have

had contact with Alcuin’s church of York

which by that time was a very significant intellectual status, with an

important library.

By the eighth century, the

kings and the church were part of a socially stratified society, with political

and economic control in the hands of an elite. The

Kirkdale archaeologists have found evidence of symbolism and the burial of

‘special’ dead, so in the middle Anglo Saxon period, Kirkdale likely had a

significance as a place in the surrounding hierarchy of the time. Kirkdale

might have been attached to a local estate and the presence of the church at

Kirkdale must have been a spiritual force which consolidated local hierarchies,

providing social cohesion,. It must have been an important expression

of Christianity which would have created local identity.

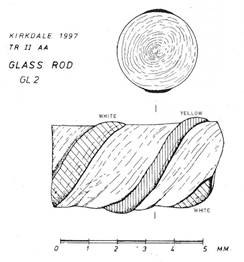

Kirkdale

probably had an important relationship by the eighth century with what was by

then perceived as the past. This might have been visible in its use of earlier

Roman materials and as a symbol of enhanced associations with Christian Rome,

including through its dedication to St Gregory. The archaeologists have

identified blown glass (artefact GL2) in the Roman fashion which might suggest

a continuation of techniques from the Roman period. There may have been an

importance of Romanitas, a Latin word, first

coined in the third century CE, meaning "Roman-ness" a link with

things Roman, the collection of political and cultural concepts and practices

by which the Romans defined themselves.

Artefact GL2

(St Gregory’s Minster, Kirkdale, North Yorkshire,

Archaeological Investigations and Historical Context, Philip Rahtz and Lorna Watts,

2021, 297 to 298).

Early ninth

century

Important sculptural artefacts of the

late eighth and early ninth centuries have been found at Kirkbymoorside and

Kirkdale. By this time minsters were associated with pastoral care. What is

thought to have been part of an ecclesiastical chair at Kirkbymoorside suggests

that it might have been a mother church, reinforced by its dedication to All

Saints. So there may have been a relationship between Kirkbymoorside and Kirkdale. However

the preferred model is that Kirkdale became dependent upon the secular aristocratic

centre of Kirkbymoorside, whilst possibly having an as yet undefined

relationship with Lastingham.

It has been surmised that:

·

Lastingham,

Kirkbymoorside and Kirkdale might have been three separate and autonomous

units.

·

Lastingham,

Kirkbymoorside and Kirkdale might have been interconnected either (1)

Lastingham, a major ecclesiastical centre, with Kirkbymoorside a secular and

ecclesiastical dependent and Kirkdale an ecclesiastical dependent; or (2)

Kirkbymoorside as a secular estate with Lastingham a dependent monastery,

perhaps suitable for transhumance or seasonal grazing of livestock, and

Kirkland a dependent church.

·

An

ecclesiastical estate at Lastingham, a secular estate at Kirkbymoorside, each

having an influence over Kirkdale.

Kirkdale was most likely a continuing

element within a potentially flourishing economy, with a governmental framework

in which a strongly aristocratic church would have played an important

political role, including in Kingship. Churches would have played an important

political role in contemporary power politics.

The Vale of Pickering came to have a

significant concentration of religious establishments.

The significant artefacts excavated

relative to this period have been found in excavations to the north of the

church, at the west exterior, and in Trench II adjacent to the northern

churchyard wall at the southern edge of the northern field. These finds are

probably late eighth century and possibly early ninth century. These objects

were associated with the early church, from which they had become displaced

during later reconstruction. What survives is a tiny fraction of the original stone built structure – stone, glass and lead items which

were able to withstand decay. It could be imagined that there would also have

been non organic objects including altar cloths,

vestments and paintings, which are no longer present. The presence of items

such as glass suggest a contemporary active nexus of exchange. They could have

been newly acquired or recycled.

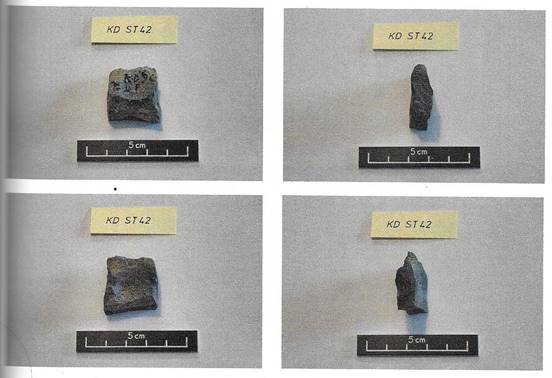

Find ST 42, found in Trench II, stands

out from other stone found at Kirkdale. It may have

been imported from a significant, possibly Italian centre and was perhaps a

relic fragment.

Artefact ST 42

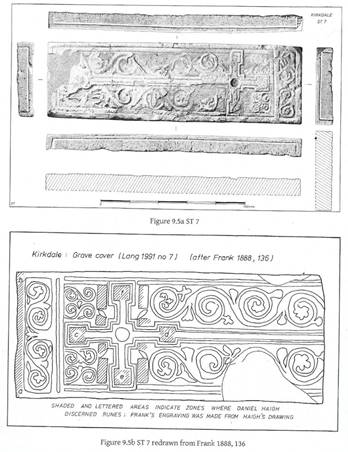

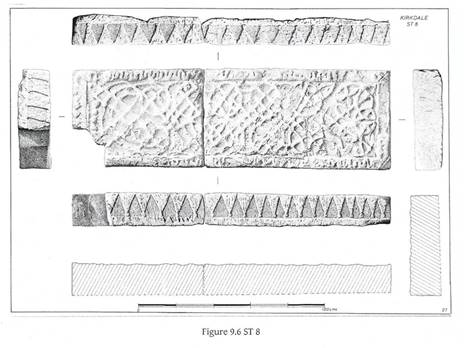

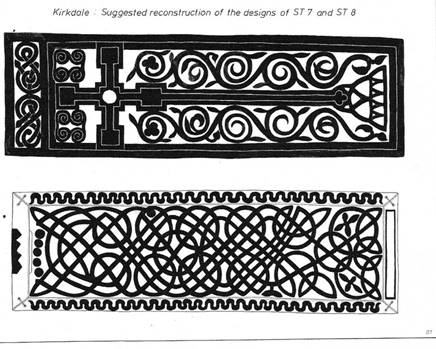

The above ground grace structures

referred to above, were designated ST 7 and ST 8 by the archaeologists. They

were found at the west exterior of the Church and have been interpreted to have

been significant above ground grave structures, likely

associated with elite members of society. Their position in the building might

have been focused with vibrant paint and possibly the play of light.

Artefact ST 7

Artefact ST 8

Reconstructed designs of ST7 and ST 8

ST8

ST7

Artefact OM 3

(St Gregory’s

Minster, Kirkdale, North Yorkshire, Archaeological Investigations and

Historical Context, Philip Rahtz and Lorna Watts,

2021, 293 to 295).

Late ninth

century to early tenth century CE

There are theories that the minster fell

into ruin, perhaps as a result of Danish raids, long

before the sundial tells us that Orm Gamalson rebuilt it. However

this might be the wrong interpretation.

How Kirkdale navigated the transition

from the Anglo Saxon to the Anglo Scandinavian period is opaque. Its placename

incorporating the Scandinavian dalr suggests

that it assumed a Scandinavian identity. The name Kirkdale, the church of the

dale, would have been no guidance in a landscape with multiple valleys flowing

down from the moors, which implies there was a continuation of it being a well known centre.

The archaeologists have found the

presence of graves which appear to be from the Anglo-Scandinavian period.

There might have been unrest, disruption

to religious observance and worse during the early Anglo Scandinavian period,

however the area around Kirkdale was off centre to the known Danish upheaval,

so it is possible that there was a relatively smooth change in local leadership

of the area.

It is difficult to interpret how

Kirkdale might have been affected by the sub division

of previously extensive estates into smaller units during this period of

increasing feudalisation and reestablishment around manors in the late ninth

century. It may well be that the church at Kirkdale might have become more

specifically responsible for the dispersed population around it, contrasting

with a greater concentration of population in the settlement of Kirkbymoorside.

When the Scandinavian government was

exercised from York, Kirkdale might have found

itself in more regular contact with York. The elite associated with Kirkdale in

time acquired property in York, but it is not known when this happened, but

this might have caused greater interconnectedness with York.

The Scandinavian dominance was the

beginning of a period of more profound change, with a tightening of the sense

of northern-ness, as a counterpoint to the southern English court.

(St

Gregory’s Minster, Kirkdale, North Yorkshire, Archaeological Investigations and

Historical Context, Philip Rahtz and Lorna Watts,

2021, 298 to 300).

Tenth century

to early eleventh century CE

The church appears to have been

destroyed by fire, most evident in excavations on its south side. There is

archaeological evidence of burning and interior fittings of wood and cloth were

inflammable.

Burials suggest that the building

continued to be in use. Any such fire must have been before it was rebuilt by

about 1055, but might not have been so long before as

has previously been interpreted.

The archaeologists suggest that St

Gregory’s minster might have reached its most extensive form before the 1055

building, although not in the nave, so this does not necessarily mean that

there were more parishioners. It probably continued to take an Anglo Saxon form

and not Anglo Scandinavian in form, and parallels have been identified with St Mary’s, Deerhurst in Gloucestershire.

The building therefore probably

continued to attract considerable patronage, and the most obvious candidate is Orm

Gamalson of the later sundial inscription or his family, as the sundial does

not make clear whether Orm’s purchasing of the building and then its later

rebuilding, were close in time.

Orm and his father Gamal were

descendants of a family that gained power when the Scandinavian King Cnut

rewarded his followers for their help in the conquest of England in 1014 to

1016. Their forebears probably included Thurbrand the

Hold (died 1024). Thurbrand was a Northumbrian

magnate in the early 11th century. Perhaps based in Holderness and East

Yorkshire, Thurbrand was recorded as the killer of

Uhtred the Bold, Earl of Northumbria. The killing appears to have been part of

the war between Sweyn Forkbeard and Cnut the Great against the English king Æthelred the Unready, Uhtred being the latter's chief

Northumbrian supporter. The family were likely players in multi

generational Northumbrian politics and feuds. They were known political

figures in the north. They had the wealth to rebuild the church on a

significant scale.

Following the fire, the area of Trench

II in the North Field became a builders yard, where

debris from the church was taken and later components of the new building

programme were prepared within the shelter of a shed like building. Disturbed

graves at the west exterior of the church reflect the chaos of the fire and its

aftermath.

(St

Gregory’s Minster, Kirkdale, North Yorkshire, Archaeological Investigations and

Historical Context, Philip Rahtz and Lorna Watts,

2021, 301 to 302).

1014

Wulfstan, Archbishop of York’s Serman to

the English People.

Wulfstan was appointed Archbishop of

York in 1002 during the trubulent times of fresh

waves of settlement from the wicinglas, the people

of the fjord settlements. By the end of the tenth century, England was a

sophisticated European state and in this context

Wulfstan envisaged a sophisticated model of society. 1014 was a year of crisis,

when King Aetheraed had been driven into exile,

expelled by Sweyn Forkbeard who was accepted as King of the English before

dying in 1014. Thus his young son Cnut became King.

Wufstan had long served in Aethelraed’s

administration. In this context he wrote his sermon to the English people, Sermo Lupi ad Anglos (Lupi being the Latin

for wolf, Wulfstan’s pen name). The sermon provided a contemporary definition

of morality and was a landmark in the evolution of English civilisation.

The sermon began with a sense of

foreboding: Beloved people, know that this is true: this world is in haste and it approaches its end. And so, because of the

nation’s sins, things must of necessity grow far more evil

before Antichrist’s advent: and then indeed they shall be appalling and

terrible widely throughout the world.

It continued: the devil has too much

led stray the nation … if we are to expect any cure, then we must

deserve it of God better than we hitherto have done…. God’s houses are

too cleanly despoiled … Nor has anyone been faithful in thought towards another

as duly he should … people have not very often cared what they have wrought by

word or by deed …

He then recounted that There was a

historian in the days of the Britons called Gildas, who wrote about their

misdeeds, how they by their sins so overly much angered God that in the end he

permitted the army of the English to conquer their lands and destroy withal the

Britons power …

He therefore continued And let us do as our need is: submit to what is

right and in some measure abandon what is not right …

(“When

the Danes Most Greatly Persecuted them, Wulfstan Archbishop of York’s Sermon to

the English People, translated from the

Anglo Saxon by S A J Bradley, Published by the Trustees of the Friends of St

Gregory’s Minster, Kirkdale)

1055

The church

rebuilt by Orm

The introduction has recorded that the Saxon sundial,

bears the inscription “Orm the son of Gamel acquired St Gregory’s Minster

when it was completely ruined and collapsed, and he had it built anew from the

ground to Christ and to St Gregory in the days of King Edward and in the days

of Earl Tostig”.

The inscription refers to Edward the

Confessor and to Tostig, the son of Earl Godwin of Wessex and brother of Harold

II, the last Anglo Saxon King of England. Tostig was the Earl of Northumbria

between 1055 and 1065. It was therefore during that last relatively peaceful

decade, immediately before the Norman conquest, that Orm, son of Gamel rebuilt

St Gregory’s Church.

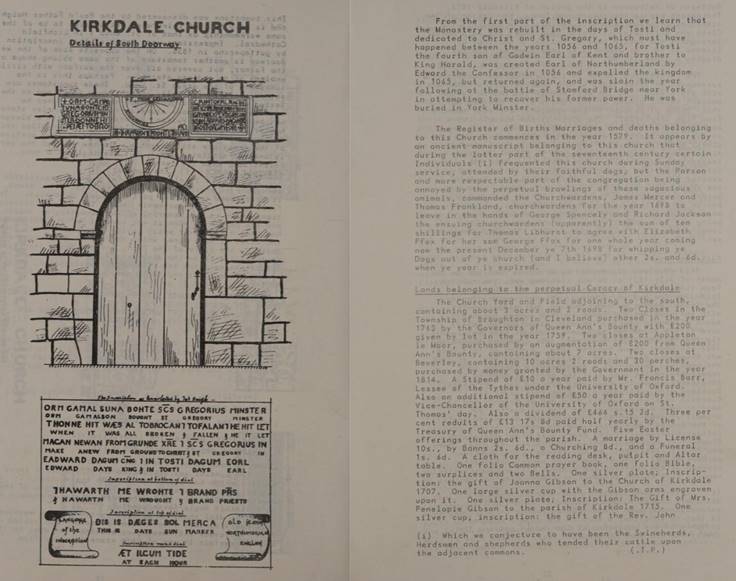

The sundial consists of a stone slab

nearly eight feet long (236 cm) by about twenty inches wide (51 cm), divided

into three panels. The central panel contains the dial, and the Old English

inscription above it may be translated as "This is the day's sun-marker

at every hour." The panels to left and tight contain the further

inscription in Old English which furnishes precious information about the early

history of the church:

Left-hand panel: "Orm the son of

Gamel acquired St. Gregory's Minster when it was completely ruined.”

Right-hand panel: “and collapsed, and he had it built anew from the ground

to Christ and to St. Gregory, in the days of king Edward and in the days of

earl Tostig."

At the foot of the central panel a

further inscription reads: "Hawarth

made me: and Brand (was) the priest."

Short though it is, this inscription

provides us with a wealth of information. It enables us to date the earliest

phase of the existing fabric with some precision. Tostig, the son of Earl

Godwin of Wessex and the brother of Harold II the last Anglo-Saxon king of

England, was earl of Northumbria from 1055 to 1065. It was therefore during

that decade that Orm the son of Gamel rebuilt St. Gregory's church. It is very

rarely that we can date the construction of an early medieval church so

precisely.

The sundial was preserved in a coat of

plaster until it was discovered in 1771.

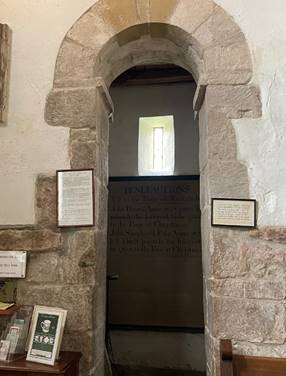

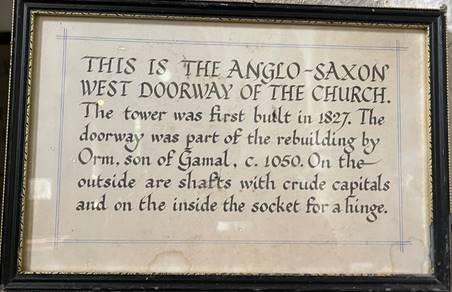

What survives of Orm's church in the

existing visible fabric appears to be the south, west, and what remains of the

east walls of the nave; the archway in the west wall of the nave (now opening

into the much later west tower) which probably formed the original entrance to

Orm's church; and the jambs, angle-shafts, bases and capitals of the arch which

leads from the nave into the chancel. The latter archway is some four centuries

later than Orm's church, but it appears that the masons who were responsible for

it re-used what they could of an earlier chancel arch. It is therefore

reasonable to infer that Orm's church had a chancel,

though not all Anglo-Saxon parish churches did, though it was probably a great

deal smaller than the existing one.

Much of the present nave in undoubtedly

Orm’s building. The western entrance arch and the responds of the chancel arch

belong to that period. Old masonry including grave slabs and crosses, was later

used in the west and south walls.

So the Scandinavian named Orm rebuilt the

minster – not Viking destruction, but Scandinavian reconstruction.

Characteristically Anglo-Saxon

architectural features are (1) the size and manner of laying of the qunins of the south-west and north-west outside corners of

the nave; (2) the height and narrowness of the western arch; and (3) the

simplicity of the bases and capitals of the angle-shafts of the western and

chancel arches.

It is possible to discover a little bit

about Orm from the slender documentation which survives from the eleventh

century. Both Orm and Gamel are Scandinavian names. The sundial at Old Byland

church was commissioned by 'Sumerled the housecarl', another Scandinavian name,

and the housecarls were the eilte troops who formed

the backbone of Canute's armies.

Orm Gamalson is an Old Norse name which

roughly translates as Dragon Oldson.

Orm was a prominent person in

Northumbria in the middle years of the eleventh century. He married into the