|

|

Alum

Historical and geographical information

|

|

Alum

The Jurassic shales and sandstone of

Cliff Ridge and Gribdale contain bands of ironstone,

jet and alum, as well as whinstone.

The oldest of these industries was alum.

This mineral had been used since ancient times for many purposes including

medicinal (as cure for haemorrhages, nits and dandruff, and other ailments).

Its main uses since the middle gages were to increase the suppleness and

durability of leather and in the textile industry as a mordant to make

vegetable dyes fast.

Prior to the middle of the fifteenth

century the supply of alum came from Turkey and a flourishing trade was done

between Asia Minor and Italy. The Italians required the alum for their dyeing

establishments, and after the capture of Constantinople by the Turks in 1453

they objected to buying it from Islam and sought other sources of supply. John

di Castro, who had been a dyer of cloth in Constantinople and had watched the

manufacture of alum, was driven back to Italy. There, at Tolfa, he discovered

an alum rock and was duly rewarded by the Pope, who thereupon began the great

papal monopoly in alum; an industry thus began at Tolfa which still exists, and is the source of the commercial Roman alum.

Although German miners had settled in

England long before the reign of Queen Elizabeth, the queen did much to

encourage home industries and in order to escape the

payment of tribute to the Pope she invited to Britain "certain foreign chymistes and mineral masters." Among them was Cornelius

Devoz, to whom was granted the privilege of "mining

and digging in our realm of England for allom and

copperas." After that there is a gap in our knowledge of the alum

industry, but the Belham Bank works near Guisborough are supposed to have been

opened in 1595. According to A. Anderson the first alum works in England were

erected at Guisborough in 1608. The person responsible was either Sir Thomas

Chaloner, who according to T. Pennant suspected the presence of alum because

the trees in the district were of a weak colour, and according to G. Young

because of the taste of the water issuing from the shales; or Sir J. Bouchier,

who is said to have improved upon the method of manufacture. At any rate,

Chaloner apparently induced Italians to leave the papal works at Tolfa and come

to Yorkshire, for which he was excommunicated and heavily cursed by the Roman

Church.

Alum Shale is found in beds immediately

beneath the sandstone of the North York Moors.

Alum mining has been a North Yorkshire

industry since alum was first discovered in the hills around Guisborough by Sir

Thomas Chaloner the younger in the 1590s. At the end of the 16th century Thomas

Chaloner visited alum works in the Papal States where he observed that the rock

being processed was similar to that under his

Guisborough estate. At that time alum was important for medicinal uses, in

curing leather and for fixing dyed cloths and the Papal States and Spain

maintained monopolies on its production and sale. Chaloner secretly brought

workmen to develop the industry in Yorkshire, and alum was produced near

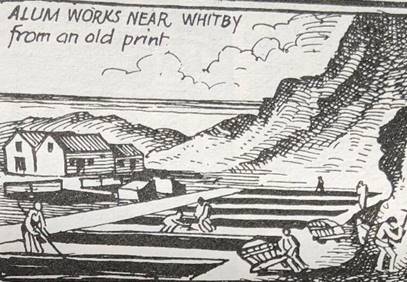

Sandsend Ness 5 km from Whitby in the reign of James I. Once the industry was

established, imports were banned and although the methods in its production

were laborious, England became self-sufficient. Whitby grew significantly as a

port as a result of the alum trade and by importing

coal from the Durham coalfield to process it.

In 1610 James I made Alum production a

monopoly of the Crown.

In 1616 Alum production began at Selby

Hagg, near Hagg Farm, Skelton around this date. It is said that ships anchored

off Saltburn to transport the finished product. They brought with them casks of

urine, which was mixed with the liquid that had been obtained from the calcined

shale. It is not presently known where this process was carried out initially,

as later in the century it was done in an Alum House sited near Cat Nab in

Saltburn. The shale liquid ran from Selby Hagg by gravity down a trough

that followed the course of Millholme Beck.

From the early seventeenth century until

the 1860s it was extensively mined at Guisborough and along the East Cleveland

coast. The actual extraction of alum from shale was a long and expensive

process and it took an average of 50 tons of shale to produce one ton of alum.

In the 16th-century alum was essential in the textile industry

as a fixative for dyes. Initially imported from Italy where there was a Papal

monopoly on the industry, the supply to Great Britain was cut off during the

Reformation. In response to this need Thomas Challoner set up Britains first

Alum works in Guisborough. He recognised that the fossils found around the

Yorkshire coast were similar to those found in the Alum quarries in Europe. As

the industry grew, sites along the coast were favoured as access to the shales

and subsequent transportation was much easier.

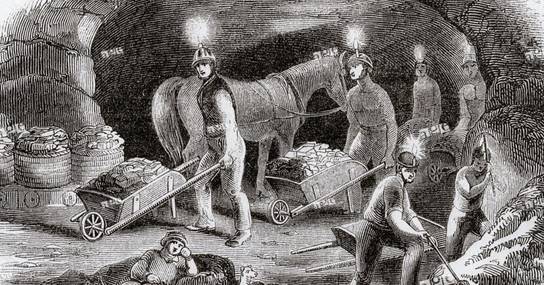

Alum mine, Cleveland

In

the mid eighteenth century the price of alum was particularly high and reached

a peak of £24 per ton in 1765. It therefore became commercially viable to mine

in places where this had not been the case previously. Several new mines were

therefore opened including one east of Ayton at Ayton Bank, just north of

Hunter’s Scar.

Cockshaw

Alum Works at Gribdale quarried and processed the

shale to produce alum crystals in the eighteenth century.

At the peak of alum production the industry required 200

tonnes of urine every year, equivalent to the produce of 1,000 people. The

demand was such that it was imported from London and Newcastle, buckets were

left on street corners for collection and reportedly public toilets were built

in Hull in order to supply the alum works. This unsavoury liquor was left until

the alum crystals settled out, ready to be removed. An intriguing method was

employed to judge when the optimum amount of alum had been extracted from the

liquor when it was ready an egg could be floated in the solution.

The last Alum works on the Yorkshire Coast closed in 1871. This was due to the

invention of manufacturing synthetic alum in 1855, then subsequently the

creation of aniline dyes which contained their own fixative.

There are many sites

along the Yorkshire Coast which bear evidence of the alum industry. These

include Loftus Alum Quarries where the cliff profile

is drastically changed by extraction and huge shale tips remain. Further South

are the Ravenscar Alum Works, which are well preserved and enable visitors to

visualise the processes which took place

Alum and Skelton

In the Skelton

area Alum production began from about 1603. The first profitable site in

Yorkshire was opened in 1603 at Spring Bank, Slapewath,

which was then part of Skelton. This was the project of John Atherton, joint

owner by marriage of a third part of the Skelton Estate.

Britain at this time was an Agricultural

nation and Wool was its chief export.

Alum was used in the dyeing process as

the setting agent and was also needed in the tanning of hides. It was therefore

a highly valued product, which up to this time had been imported. Rich rewards

seemed to beckon those who could create a home industry. The process was

complex. The alum bearing rock was quarried, broken up and ‘calcined’ or built

into large clamps with alternating layers of wood and these piles would be

ignited and a controlled burning would last for weeks. It needed many tons of

shale to produce 1 ton of alum. The

burnt, ‘calcined’, shale was then steeped in water-filled stone troughs until a

certain specific gravity had been reached (tested for, the story goes, by

floating an egg in the liquid). The liquid was then run off and boiled in large

pans heated by coal for 24 hours and mixed with an alkali, obtained from urine

or seaweed.

Thomas Chaloner of Guisborough is

reputed to have sold his personal urine for one penny a Firkin, which was about

8 gallons. How often he earned or spent a penny or earned one is not recorded.

History shows that we have had many odd

names for imperial measures, pecks and gills etc. A ‘Firkin a Fortnight’ for

pee.

Next the mixture was transferred to

small coolers to crystallize, the resulting crystals of alum being further

boiled and condensed to get rid of impurities. Many legends survive, but it is

not known how this long and involved chemical process was discovered in these

times, when people believed in alchemy and the modern science of Chemistry was

a mystery.

It is reported that the workers suffered

terrible conditions – the heaps of shale gave off poisonous sulphurous fumes

and at times their wages of 6 pence a day were often withheld or ‘given in half

rotten meat and corn.’

The alum workers were described at one

point as: ‘poor snakes, tattered and naked, ready to starve for want of food

and clothes.’

Other Alum mines were eventually opened

by the Skelton Estate, notably at Coombe Bank, Boosbeck

and Selby Hagg between Skelton and Brotton and were worked on and off during

the next two centuries. The Selby Hagg works were located to the east of Hagg

Farm, near Skelton-in-Cleveland, and would seem to have had three distinct

periods of operation.

During the first of these, from about

1617 to 1643, the Alum house may have been located within the quarry.

The second phase ran from 1670 to 1685,

and the third from 1765 to 1775. The alum houses for these latter two phases

were located at Saltburn.

Most successful were the ones on the

coast which did not have the cost of transporting fuel and the finished product

for shipment.

The Alum workings at Hummersea,

Loftus were worked well into the 19th Century.

Major Robert Bell Turton

of Kildale Hall, N Yorks The Alum Farm, 1937: "There was a house at Spring

Bank, near Mygrave [now Margrove

Park] erected, but not completed for the manufacture of Alum. On the 15th

November 1603 an agreement was made between John Atherton and Katherine his

wife of the one part and Mr Leycolt of the other,

under which the Athertons were, at their own cost, to

complete the house and furnish it with the necessary appliances, namely, four

Furnaces and four pans of lead and iron for boiling Alum, Coolers of lead for

congealing , and convenient Cisterns of lead for keeping and saving the

"mothers" or strong liquors of alum and Copperas [green vitriol or

Iron Sulphate]. They were also to set up a lead-finer with furnace, a balnium for trial of the earth for alum and copperas, pits,

pipes, vessels for draining the earth and making liquors and all other

necessary implements."