|

|

Doncaster Parish Church to the time of William Farndale

|

|

The original medieval

parish church of St George burnt down on the last day of February 1853. This

fire resulted in the loss of the medieval library which was above the south

porch. The current Doncaster Minster is therefore an impressive Victorian

structure built after 1853.

In order to

enter the world of William Farndale (FAR00038),

Chaplain of Doncaster Parish Church by 1355 and Vicar of Doncaster Parish

Church from 8 January 1396 to 31 August 1403, we need to understand the earlier

church.

First

century CE

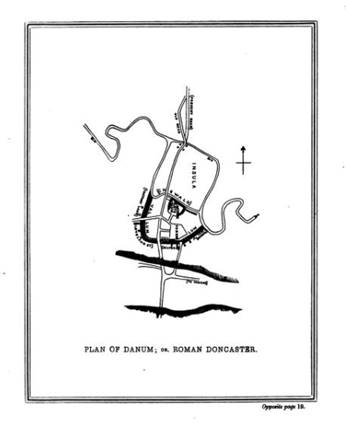

In Roman Doncaster, the present

market-place was in all probability used then for the same purpose that it is

now. It would also contain, as most Roman market-places did, the public Temple.

At all events, on whatever other site such Temple may have stood, it could

hardly have been on that of the Church of St. George; for, in the times of

which we are speaking, that site was unquestionably the true Castrum, or

Pretorian Camp, a military fortress, or barrack, enclosed within special

defences of its own

After the Romans had abandoned Britain,

this Castrum, or military enclosure, became at a later period the site of a

castle belonging for some centuries to the feudal lords of Doncaster. By whom

it was built, or when it was destroyed, there is not a fragment of evidence to

show; but that such castle did stand here, we have the positive testimony both

of Camden and Leland. The latter, 300 years ago, about a.p.

1538, visited the town, and saw part of the outworks of the Castle still

remaining. “‘ The church,” he says, ‘‘ stands in the very area where ons (once) the castelle of the towne stood, long since clene

decayed, the dikes partly yet to be seen, and foundation of part of the walles. There is likelihood,”’ he adds, ‘‘ that when this

church” (the Perpendicular St. George’s) ‘‘ was erected, much of the ruines of the castelle was taken

for the foundation, and filling up of the waullis of

it.” In Pryme’s MS. Diary, it is stated that part of

the walls were in existence so late as a.p. 1694.

Though, therefore, we have really no account whatever of the Castle of

Doncaster, either as to the time of its being built or destroyed, and though it

is impossible to say what Leland might have understood by ‘‘long since clene decayed,” still, we have his ocular testimony and the

tradition which was then reported to him, in proof of the fact that the castle

did stand here, and that, moreover, it comprised within its area and special

defences, the ground now occupied by St. George’s Church and churchyard.

If, in the early days of Doncaster, this

ground was occupied by a castle and castleyard,

specially defended by walls, could it conveniently have contained, at one and

the same time, a Parish Church and churchyard? The two uses are very

incompatible. A Parish Church, being required for public daily or hourly use,

ought to be within daily and hourly access, without the risk of interruption.

The same with the cemetery. But the public cemetery and church of the

parishioners would hardly have been open to such uninterrupted access, and

ready for use at any moment, if, between the people without and the cemetery

and church within, there was constant risk of ‘Veto’ from portcullis or

sentinel. No place, again, would have been so wholly inappropriate to the

tranquillity proper for holy offices and services as the noisy precincts of a

barrack-yard.

That Doncaster Castle may have had, as

almost all castles had, its own chapel within its own walls, is likely enough.

But that, so long as it was the chief military and feudal garrison of the town,

it should have contained within its enclosure the Parish Church and Parish

cemetery, when there was room for them elsewhere, appears, at all events, very

unlikely.

Those, therefore, who think that on the

site of St. George’s have stood all the Parish Churches of Doncaster, in

succession, from that of Paulinus downwards, have to meet this choice of

difficulties. They must either insist on what is improbable, viz., that the

earlier Parish Churches of the town were imprisoned within the walls of its

fortress ; or they must get rid of the fortress before the time of Paulinus, a.p. 633. But this would be to annihilate Doncaster Castle

before that very period of history when such strongholds were most abundant and

most needed. In short, to destroy it so early, would be to allow it scarcely

any existence at all.

If however there should have been, all

this while, another site in Doncaster free from this difficulty of contested

occupation ; one in the very heart of the town, open and accessible at all

times ; and if it could be shown that on that site there had existed an

ecclesiastical building, not only of great antiquity, but of antiquity greater,

so far as we can at present judge, than any portion of St. George’s ; if,

beside such other church, there should also have been, surrounding it, a

cemetery of considerable extent; is there not, in these circumstances, and

considering the comparatively smaller size of the ancient town which would

hardly require two cemeteries, fair reason for conjecturing that this, after

all, may have been the site of the original Parish Church?

(from Rev

Jackson, History of the ruined church of Mary Magdalene, 1853)

627

CE

Edwin of

Northumbria (586 to 633) was baptised in York about 15

years after the death of Augustine.

When Augustine

came to Britain, he does not appear to have attempted to bring his mission to

Northumbria. However Edwin, King of Northumbria, married the daughter of

Ethelbert, the converted king of Kent and it was agreed that she should freely

exercise her religion. She was accompanied by a zealous pupil of Augustine,

Paulinus, and this provided the basis for Edwin’s conversion. From that time,

Paulinus was increasingly employed in conversion across the region of

Northumbria. One of the areas of Paulinus’ conversion was on the banks of the

Gleni and the Swale and at Campodonum (South Yorkshire, the History and Topography of the

Deanery of Doncaster in the Diocese and County of York by Rev Joseph Hunter,

1828, page xiv, Bede’s Ecclesiastical

History, Chapter 9, 14).

Bede describes

the catechizing and baptising of Paulinus during times when he

instructed crowds in Bernicia and in Deira. He often followed river courses and

baptised along the river Swale, where it flows beside the town of Catterick and

in Cambodonum, where there was also a royal

dwelling, he built a church which was afterwards burnt down, together with the

whole of the buildings, by the heathen who slew Edwin [this was when Penda

defeated Edwin at Hatfield in 633 CE]. In its place later kings built a

dwelling for themselves in the region known as Loidis.

This altar escaped from the fire because it was of stone, and is still

preserved in the monastery of the most reverend abbot and priest Thrythwulf, which is in the forest of Elmet. (Bede’s Ecclesiastical History, Chapter 14). Loidis is modern Leeds. Cambodonum

has been interpreted as various locations in the West Riding, but it probably

derives from “Field of the Don” and is more likely a reference to Doncaster.

So, it is

likely that a church was erected in the place of modern Doncaster at this time.

If this is correct, then Paulinus also tells us that Edwin had a royal

residence (villa regia) at Campodonum. The

praetorium of the Roman Castrum might have been an ideal site for an occasional

royal residence. This would suggest that the church at Doncaster was burnt down

by Penda after the Battle of Hatfield Chase in 633 CE. So no sooner was the

first church built, that it was destroyed and the progress of Christianity in

Doncaster was interrupted.

Bede’s work

also suggests that a second Christian church, after the church at York in 627

CE, was built in Doncaster under Paulinus’ supervision.

(South Yorkshire, the History and Topography of the

Deanery of Doncaster in the Diocese and County of York by Rev Joseph Hunter,

1828, page 4 to 5, 34)

633

CE

Edwin was

killed by the pagan Penda at the heath field on Hatfield Chase, 10km northeast

of Doncaster. It appears that Penda immediately attacked Doncaster and

destroyed the church, and probably the royal residence, as we don’t hear of

Northumbrian kings returning. However the altar was preserved in a monastery in

the wood at Elmet,

around modern Leeds.

However the

church was rebuilt, the monastery at the mouth of the river referred to by

Alfred of Beverly. The early churches were more like monasteries than early

parish churches (see Kirkdale). Early religious

men lived around these places and made ecursions into

the countyryside, before the time of parish churches.

764

CE

In 764 the chronicler Symeon

of Durham in his Historia Regum groups York with

London, Doncaster, and other places, repentino igne vastatae (destroyed by a sudden fire). (A History of the County of York: the City of York.

Originally published by Victoria County History, London, 1961).

Multae

urbes, monsteriaque, atque villae, per diversa loca necnon

et regna, repentino igne vastatae sunt; verbi gratia, Stirburgwenta civitas, Homunic, Lundonia civitas, Eboraca

civitas, Donacester, aliaque

multa loca illa plaga concepit.

Many cities, towns, and villages, in different places,

as well as kingdoms, were destroyed by a sudden fire; for example, the city of Stirburgwent, Homunich, the city

of London, the city of York, Doncaster, and many other places were conceived by

that plague.

There is evidence of fire in the area of the Roman

castrum, but these marks may have been the result of the devastation by Penda.

This was a time when Alcuin of York, in the Kingdom of

Charlemagne, was despairing of the fate of his homeland.

813

CE

Alfred of Beverly recorded the destruction of the monastery

at the mouth of the Don by Danes, which may have been a reference to Doncaster –

Monasterium ad ostium Doni amnis precaverunt, sed non impune; “They prayed

to the monastery at the mouth of the river Don, but not with impunity”.

1086

Shortly after

the Norman Conquest, Nigel Fossard refortified the

town and built Conisbrough Castle. By the time of

Domesday Book, Hexthorpe in the wapentake of Strafforth

was said to have a church and two mills. The historian David Hey says these

facilities represent the settlement at Doncaster. He also suggests that the

street name Frenchgate indicates that Fossard invited fellow Normans to trade in the town.

Doncaster was ceded to Scotland in the Treaty of Durham and never formally

returned to England!

Rev Jackson’s

book (see below) tells us: “At the Conquest there was a Church and a single

Priest , whose nomination lay with the Fossards,

feudal Lords of the town. In the reign of William Rufus, Nigel Fossard , leaning with the special favour of those times

towards the establishment of monastic houses, made to the newly founded Abbey

of St. Mary's, near the walls of York, a donation which is thus described in

his charter.”

There was significant

building of monasteries and parish churches during this period. The building of

churches was attractive since this allowed the lords to extract tithes from

distant churches to which it had been paid and settle it on churches of their

choosing, perhaps closer to their own residence. During this period churches

were built at places including Coningsborough,

Campsall, and Doncaster. Joseph Hunter lists 60 places where Churches were

built. Most of these churches had one officiating minister at their foundation,

the persona or rector. The churches were often placed under the

patronage of monastic institutions. The church at Doncaster was distinguished

from others by being given the title of dean. Certain of these churches were

parish churches in form, but were also referred to as chapels, which meant that

they were given rights of baptism, nuptial benediction and of sepulture, but were not able to participate in tithes from

the lands around them. These churches included St Mary Magdalene at Doncaster and

the chapel at Loversall.

(South Yorkshire, the History and Topography of the Deanery

of Doncaster in the Diocese and County of York by Rev Joseph Hunter, 1828, page

xvi to xx).

1088

Early in the

reign of William II (William Rufus), Nigel Fossard was

amongst the benefactors who founded the abbey of St Mary in York.

Fossard gave the church of Doncaster to the new abbey

as well as lands in the area.

Twelfth

century

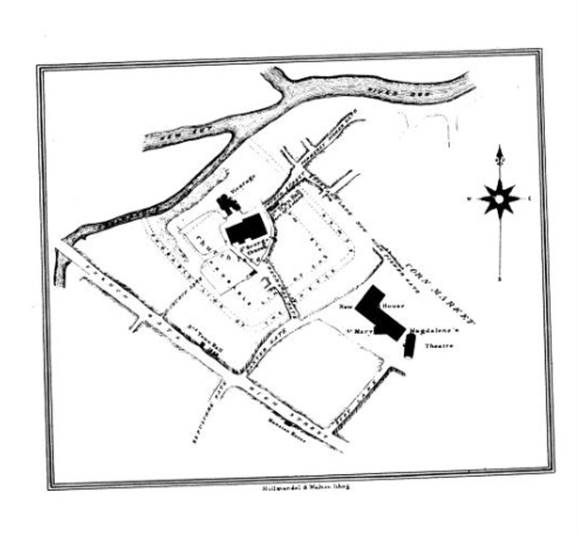

The church of

St Mary Magdalene stood in the market place and may have been the early parish

church of Doncaster, but it soon served as a chapel.

By the reign of

Henry II (1154 to 1189), it was a chapel.

By 1248, a

charter was granted for Doncaster Market to be held in the area surrounding the

Church of St Mary Magdalene.

(See also South Yorkshire, the History and Topography of the

Deanery of Doncaster in the Diocese and County of York by Rev Joseph Hunter,

1828, page 20).

c1200

Robert

de Turnham tried to recover the rights in the church which Nigel Fossard had given to St Mary’s Abbey, York, but had to

acknowledge the continued rights of the abbey, but was given a right to the

chapels at Loversall and

Rossington, which were part of the parish of Doncaster.

1204

There was a

disastrous fire in 1204 which appears to have completely destroyed the town, from

which the town slowly recovered.

At some stage

during the reign of King John, there were two rectors of the parish church,

called Hugo and John.

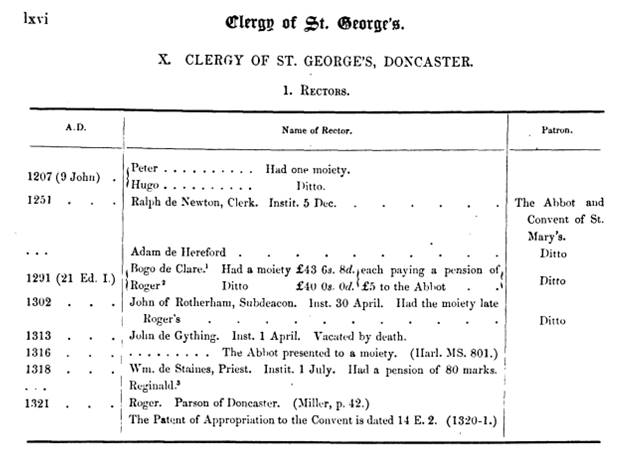

1291

The ecclesiastica taxatio

listed the parish churches of England and Wales in 1291 to 1292 and listed St

George’s at Doncaster, whose patronage was to the Benedictine St Mary’s Abbey

at York, assessed for tax at £93 6s 8d.

The main source

for St George’s Parish Church is the History of

St George’s Church, Doncaster, Destroyed by Fire, February 28, 1853, by the Rev J E Jackson.

Rev

Jackson suggested “according

to Leland, an eye-witness about A.D. 1510, the late Parish Church stood upon

area and within the walls (some of their foundations then remaining) of the

ancient Castle of Doncaster. Whether the Castle, whilst used as such, had

contained any spot of consecrated ground ; whether that ground had been

occupied by a parish church or only a chapel; at what time the whole area of

the Castle became consecrated and parochial ; and in what style any first

churches may have been built, are points that will receive from this Volume

little or no aid to solution.”

From

excavations after the fire in 1853, Jackson concluded that if the church had

been of Norman origin, it would have lasted scarcely a hundred years as the

fire of Easter 1204 consumed the town of Doncaster so if it had existed it must

have been destroyed.

Rev

Jackson suggested that the

original church “had been in its previous (we dare not say original) state,

essentially and throughout of the order known as “ First Pointed ," or

Early- English. The period usually allowed for that style is about 118 years,

from 1 Richard I to 35 Edward I.” So this suggests the origin of the parish

church to have been 1189 to 1307.

He then says “we

are not wholly without grounds for suggesting the names of one or two principal

promoters”:

·

“The

cost of the chancel would be provided by the owners of the Rectorial

property, then the Abbot and Convent of St. Mary's at York. Under such

influence, that part might be expected to correspond (as from the pattern

remaining in the old side -windows appears to have been the case) with the more

enriched variety of this style, of which that Abbey was itself an exquisite

specimen”. Note the

connection of the Stutevilles to the Convent of St Mary at York in the early

history of Farndale.

·

“Amongst

contributors to the rest of the Church, without ranging vaguely beyond the bounds

of reasonable conjecture, one may perhaps be identified in the person of Robert

de Turnham , a Crusader under Richard I., distinguished by special notice

in metrical chronicles of the day.” “He was, in fact ( by marriage with

the heiress of the Fossards) , Lord of Doncaster, and

actual owner of the estates now possessed by the Corporation.” “he was

contemporary with, and must have been a sufferer in property by, the Fire of

A.D. 1204, is certain ; for he did not die until six years after it, in A.D. 1210.”

1300

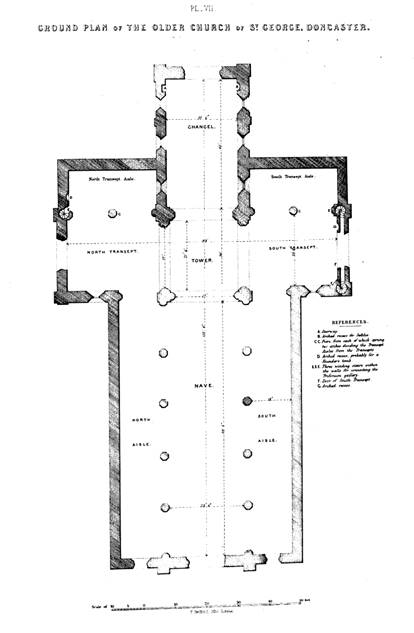

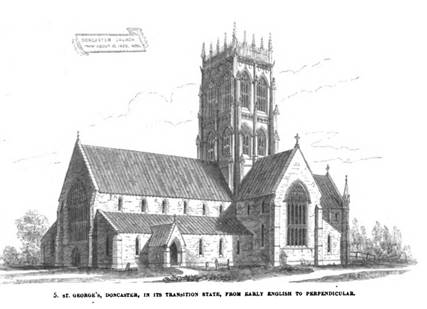

As to a

description of the church of William Farndale’s day:

·

“the

width of the Nave (50 feet)”

·

“The

form , that of the Latin Cross, having Nave and Chancel; with Transepts (North

and South ), to each of which was appended on their eastern side a small aisle

or chapel.”

·

“At

the west end … it is not unlikely that there may once have been a Norman Door.”

·

“The

nave was formed by two large arcades, each consisting of five obtusely -

pointed arches rising upon massive octangular pillars. The capitals and

mouldings were without ornament, and of the earliest period of this order of

architecture, dating probably from about A.D. 1190 to A.D. 1200.”

·

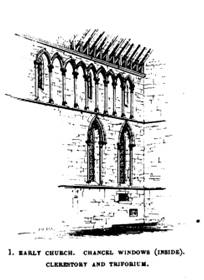

“Above

these large arches (between them and the roof) there was originally a range of

low windows (forming the Clerestory)”

·

“Behind

them, and within the thickness of the Church wall, ran a narrow gallery known

as the “ Triforium ” passage”

·

“Four

massive piers at the cross were ready to support some kind of steeple”

This is his

ground plan for the older church:

“Of the

exterior, an outline, to a certain extent conjectural, but representing what the

Church is most likely to have been about the year 1300, is given below:”

So this seems

to be the best representation of the church in the time of William Farndale.

Rev

Jackson went on to explain

that “yet, within little more than two centuries, we shall find that almost

every other part of it had been once more renewed”. He ponders why it was

necessary to carry out such extensive renovation so soon. However this would

seem to take us beyond the time of William Farndale. There are however some

observations which help:

·

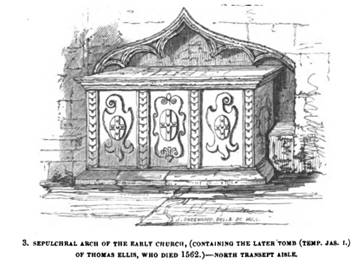

“The

first and almost the only monument of any quality or consequence in Doncaster

Church was of the year 1465.” (ie after William

Farndale)

·

However

“the cross slabs discovered (chiefly ) about the Foundation of the South

Transept, besides those above mentioned in the roof of the Crypt, are indeed of

the thirteenth century” (ie before William

Farndale)

·

And

“some of the ' inscriptions copied by De la Pryme

(as will be seen on referring to them in a later page) bear dates between A.D.

1330-1413” (ie during William Farndale’s time.

·

“These

would have been in or belonging to the Church before it was altered : but no

memorial of any kind better than a simple gravestone appears until the Church

had been made almost new again.”

1303

As the size of

the church grew it was felt that the pension was not sufficient to maintain two

rectors and an appeal was made to Archbishop Corbridge. A perpetual vicarage

was ordained and the vicar was to have 50 marks sterling for his support paid

quarterly by the abbot and the convent, with a penny paid for every funeral.

The vicar was also exempted from tithe payments for his cattle and the general

tithe rate for the church lands was reduced to a quarter (South Yorkshire, the History and Topography of the Deanery

of Doncaster in the Diocese and County of York by Rev Joseph Hunter, 1828, page

34).

Jackson wrote: “in A.D. 1303 , the Monks of

St. Mary's … discovered that for two Rectors to divide the profits between them

, leaving only a small pension to the Abbey, could never have been the meaning

of Nigel Fossard. So having succeeded in convincing

Archbishop Corbridge, and the other ecclesiastical authorities in such cases

appealed to, that the Latin of Fossard's charter

ought to be differently translated, they obtained leave to appropriate the

Rectory to themselves. The act of appropriation does not appear to have taken

effect for about 17 years ; as the institution of Rectors continued to 1318 ,

and it was not until 1320-1 that the Royal Patent was granted, and that

Archbishop Melton confirmed the proceedings. The two Rectors at that time

were Roger and William de Staines. The former probably died about that

time; as we find only the latter pensioned off, with the liberal allowance of

80 marks per annum for his life. From this time all the tithe, both great and

small (“ totam ” in Fossard's

charter) flowed to the treasury of St. Mary's at York ; and one clergyman,

under the title of Perpetual Vicar, was appointed to be the resident guardian

of parochial duties. One of the two Rectory houses, “ with the whole place,”

was assigned to the Vicar, with the annual stipend of 50 marks (331. 6s. 8d .

), to be paid him by the Abbey. With the amount of this provision, considering

the times, no fault was to be found ; nor would his successors in the Vicarage

have had any reason to complain, if the stipend had been proportionately

increased according to the change in the value of money : but in this material

point the endowment was neglected. Whilst the Abbey and all succeeding owners

of the Tithe altered the amount of their receipts, no change was for a very

long time made in the original figures of the Vicar's stipend. Besides this

money payment, the Ordination awarded to him , “ his vigils for his labour,

with the penny offered at funerals and the penny at the Church door for

marriages : " in other words , certain perquisites resembling modern

" surplice fees. ” He was to be exempt from payment of tithe upon his own

cattle , but was burdened with one - fourth part of the charges upon the

Rectory. Archbishop Melton, in giving his sanction to this arrangement,

stipulated with the Monks for two pensions out of the Rectorial

tithes: one of 10l. a-year to himself and his successors in the see of York ,'

the other of five marks a-year (31. 6s. 8d .), to be distributed amongst the

poor ” of Doncaster for ever.” The period of the Rectors continued until

1320 when Walter de Thornton was appointed as the first Priest/Vicar.

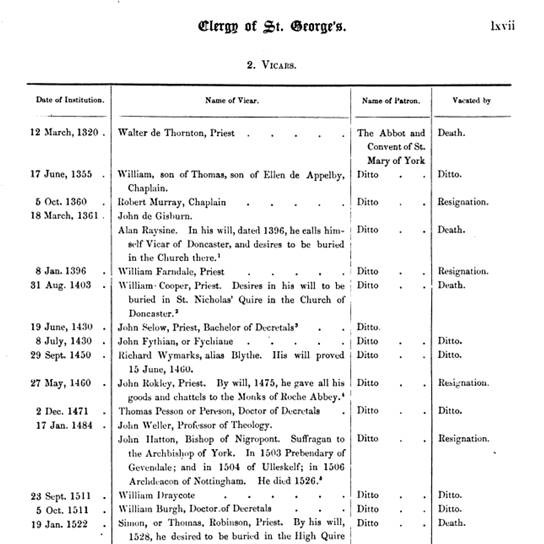

1320

The arrangement

was confirmed in 1320 when it was also ordered that the religious community

should distribute ten marks to the poor of Doncaster, or corn to that value.

Walter de

Thornton became the first Vicar of Doncaster on 12 March 1320.

1323

Hunter refers

to a chantry of St Nicholas founded by the chaplain Thomas de Fledburgh, in 1323. He says this was done with consent of

the rector and confirmed by Archbishop Melton on 15 February 1329 (South Yorkshire, the History and Topography of the Deanery

of Doncaster in the Diocese and County of York by Rev Joseph Hunter, 1828, page

40).

1349

John de Mekesborough became the chantry priest or cantorist on 31 July 1349 on the death of John Plumer. He

was succeeded on his death by William de Hexthorpe on 21 December 1369 (South Yorkshire, the History and Topography of the Deanery

of Doncaster in the Diocese and County of York by Rev Joseph Hunter, 1828, page

40).

1355

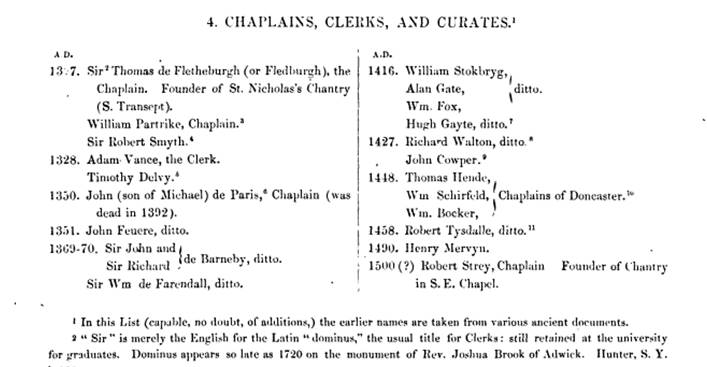

Jackson listed

the chaplains, which include William

Farndale for 1369 to 1370, but he concedes in the notes that his list is no

doubt capable of additions, and we have other evidence of William’s chaplaincy

in 1355 so he was presumably chaplain for a longer period than shown below.

William, son of

Thomas, son of Ellen de Apelby became Vicar of Doncaster

on 17 June 1355 and continued until he died.

1360

Robert Murray

became Vicar of Doncaster on 5 October 1360 and continued until he resigned the

following year.

1361

John de Gisburn

became the Vicar on 18 March 1361.

At some point

Alan Raysine became the Vicar and continued until he

died. He directed in his will that he be buried in the Doncaster church.

1392

Jackson surmised there may have been another

fire at some point.

He thinks that

“About A.D. 1392, the large Perpendicular window was inserted in the West

Front. That this was done, the rest of the Church being still Early, is clear

from an arrangement made for continuing the Triforium Gallery across the new

window by a double row of mullions in the lower tier, between which it was

conducted . The date of this insertion is supplied by the will of one Robert

Usher, of East Retford, who, in this year, bequeathed “ 5 marks towards the

construction of a window at the western end of the Church of St. George, at

Doncaster.” I At this period, therefore, the Nave would be lighted by the large

window at the end and the small narrow lights of the clerestory at the sides.”

So this was four years before William became the Vicar, while he was presumably

still the chaplain.

Jackson thought the renovated Church might have

ended up looking something like this, but this would have been after William’s

time, unless the surmised fire or some of the reconstruction had started when

William was the vicar. It was probably a bit later though.

The Rectory of

Doncaster

1396

Jackson listed the clergy of St George’s

including William

Farndale who was vicar from 8 January 1396 to 31 August 1403 when he

resigned.

Hunter descries

various burials which occurred during the time of William Farndale including

that of William Jone in 1403 (“O dere frends hafe pyte

for my soule as I hafe form

many done, yet I may come to bliss”); and Johan and Alicia Rastal in 1392 and 1398; John Savyl

of Doncaster; Robert Ellius Esq, Alderman of

Doncaster in 1402 and Catharine the wife of William Smith in 1402 (South Yorkshire, the History and Topography of the Deanery

of Doncaster in the Diocese and County of York by Rev Joseph Hunter, 1828, page

41 to 42).

Lovershall

There is also a

bit about Lovershall

(where William Farndale purchased land) in Jackson’s

book:

CHAPELRY OF

LOVERSAL

By the Chapelry

of Loversal , so constantly mentioned, is meant, in

fact, the tithes of the parish of Loversal ( a

township of Doncaster ). For the ministerial duty the Vicar of Doncaster is

responsible. Upon the subject of the small endowment of this Chapelry there is

in Archbishop Sharp's MSS the following memorandum:

The Chapel of Loversal is parochial. The Curate thereof (who is at

present Mr. Pegge, Vicar of Wadworth) is paid 41. by the Vicar of D. And Sir

John Worsman " (Wolstenholme, the last of his family who was owner of Loversal, and who died 1716) useth

to give 4l This is all the profits, except Church yard and Surplice Fees.

1403

William Cooper

became Vicar of the Church on 31 August 1403 and continued until he died. He

directed that he be buried in St Nicholas Quire in the Doncaster Church. He

described it as a beautifiul specimen of a church of

about the time of Edward III (1327 to 1377).

1434

On 15 October

1434 there was an agreement with John Fichiane, then

vicar of the parish, regarding repairs to the chancel, which the vicar was

bound to undertake.

1539

The abbey of St

Mary at York was surrendered during the dissolution of the monasteries and the

rectory was included in the great exchange on 6 February 1539.

1828

Writing in

1828, Rev Joseph Hunter described the church as it was before the fire of 1853,

with narrow loop hole windows, but an extreme richness of detail in the

ornamental parts. He referred to the font being dated 1061, but was unsure

whether it was that old. He refers to the sixteenth century Leland’s account

that it was likely that when the church was erected, the ruins of the old

castle were taken as its foundation and for the building of the walls. Hunter

described a lofty tower rich with crockets and pinnacles. He felt that Doncaster

church was more opulent than others since it was owned by St Mary’s Abbey in

York. Hunter was particularly impressed by the belfry.

(South Yorkshire, the History and Topography of the Deanery

of Doncaster in the Diocese and County of York by Rev Joseph Hunter, 1828, page

37).

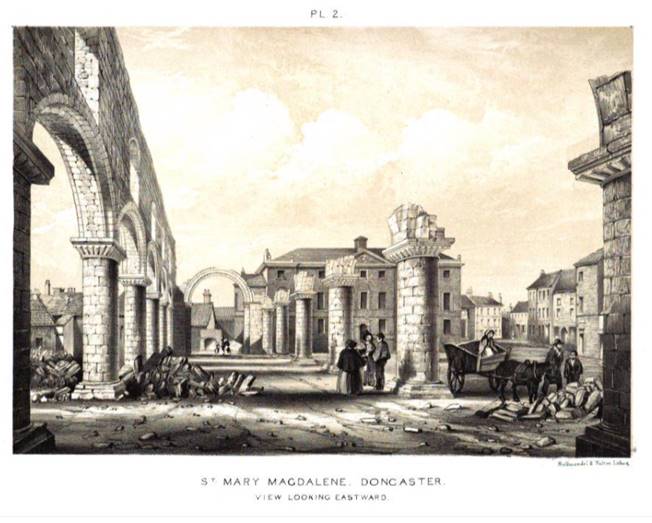

1853

The destruction

of the medieval church by fire on the night of 28 February 1853 was a great

calamity. Nevertheless, within seven days, a rebuilding committee had been

formed and raised over £11,000. The new

building, to the designs of George Gilbert Scott, took four year’s

to build. Great celebrations accompanied the consecration of the building by

the Archbishop of York on 14 October 1858.

2004

In 2004 the

church was designated as the Minster and Parish Church of St George by the

Bishop of Sheffield.

http://www.doncasterminster.co.uk/