Richard Farendale

c 1357 to 20 December 1435

A

medieval soldier who fought in the armies of Richard II and Henry V

We few, we happy few, we band of brothers …

FAR00044

|

Return to the Home Page of the Farndale Family

Website |

The story of one family’s journey through two

thousand years of British History |

The 83 family lines into which the family is divided.

Meet the whole family and how the wider family is related |

Members of the historical family ordered by date of

birth |

Links to other pages with historical research and

related material |

The story of the Bakers of Highfields, the Chapmans,

and other related families |

Dates are in red.

Hyperlinks to

other pages are in dark

blue.

Headlines are in brown.

References and

citations are in turquoise.

Context and local

history are in purple.

|

c 1357 to 20

December 1435

A veteran soldier of the armies of Richard II, Henry IV and Henry

V who fought in the French and Scottish Wars |

|

Tales of

archers and men at arms who fought with Richard II, Henry IV and Henry V and

an observation post in the home of the Nevilles and Richard III from which to

view the Wars of the Roses |

1357

Richard Farendale, son of William and Juliana Farendale

(FAR00036),

may have been born Sheriff Hutton

in about 1357 (See the Will of William (FAR00036)).

If he was 78 when

he died then he may have been born in about 1357 which makes sense with his

father’s will.

1380

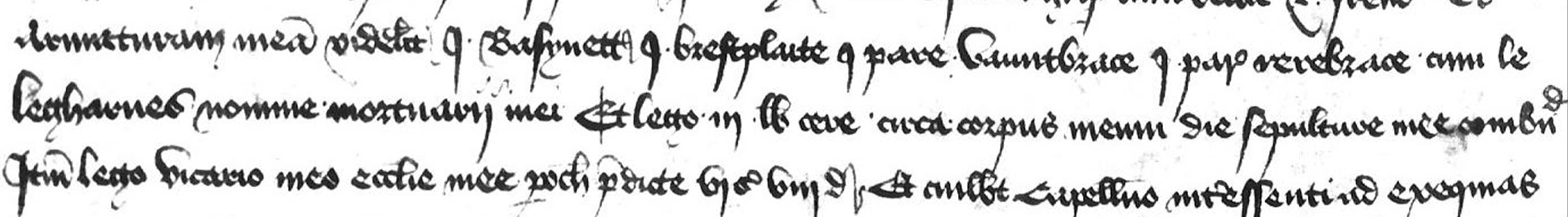

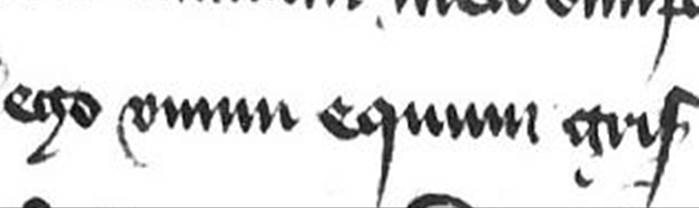

We know from his

will in 1435, that Richard Farendale bequeathed a

grey horse with saddle and reins and his armour, comprising a bascinet, a

breast plate, a pair of vembraces and a pair of rerebraces with leg harness. He appears to have been

impressively armed for military service when he died, so it seems likely that

he pursued a military career.

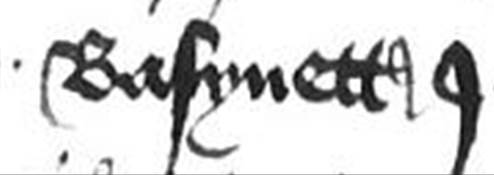

A bascinet was a

medieval combat helmet:

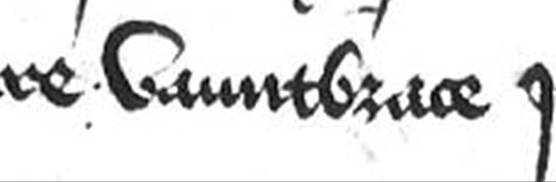

Vembraces or vambraces

were armoured forearm guards:

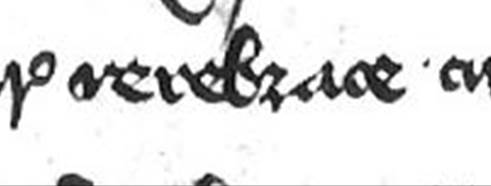

A rerebrace was a piece of armour designed to protect the

upper arms (above the elbow):

So he was well

armoured by the time he died in 1435.

There was a

Richard Farnham or Farneham, listed in records of medieval

soldiers, who joined an expedition to France as an archer on 28 June 1380

under the captaincy of Sir William Windsor, and the command of Thomas of

Woodstock, Duke of Gloucester. It is not certain that this was him, because the

spelling of the surname is different, but this was a time of fluidity in

surname spellings. Given his military equipment listed in his will, 55 years

later, it seems likely that Richard would have started a military career at

about this time. He would have been about 23 at this time. Whilst we cannot be

certain, it is possible, perhaps even quite likely, that this was Richard in

his early military exploits in France.

Before

the Hundred Years War, warfare was rooted to the principles of chivalry, with

which commoners were not participants. By the 1320s experienced soldiers fought

on foot alongside commoners. Ideas of feudal service were replaced by

professional soldiers, who undertook operations contrary to the chivalric code

including ambush, siege, raids, looting, burning, rape. The archers were the

prime example of new commoner forces, firing arrows which could easily

penetrate knights’ armour. The commoners were given opportunities to accumulate

significant wealth through war booty, and ransoms, as well as their pay.

1380

was in the midst of a crisis in the French Wars in the time of Richard II. The

Peasant’s Revolt of 1381 arose due to high taxes required to fund the French

Wars. Richard II was not a popular King, and the cost of these French wars were

not welcomed at home.

Richard’s

commander, Thomas of Woodstock had been in command

of a large campaign in northern France that followed the War of the Breton

Succession of 1343–1364. During this campaign John IV, Duke of Brittany had

tried to secure control of the Duchy of Brittany against his rival Charles of

Blois.

John

returned to Brittany in 1379, supported by Breton barons who feared the

annexation of Brittany by France. An English army was sent under Woodstock to

support his position. Due to concerns about the safety of a longer shipping

route to Brittany itself, the army was ferried instead to the English

continental stronghold of Calais in July 1380.

As

Woodstock marched his 5,200 men east of Paris, they were confronted by the army

of Philip the Bold, Duke of Burgundy, at Troyes, but the French had learned

from the Battle of Crécy in 1346 and the Battle of Poitiers in 1356 not to

offer a pitched battle to the English. Eventually, the two armies simply

marched away. French defensive operations were then thrown into disarray by the

death of King Charles V of France on 16 September 1380. Woodstock's chevauchée continued westwards largely unopposed, and in November

1380 he laid siege to Nantes and its vital bridge over the Loire towards

Aquitaine.

However,

he found himself unable to form an effective stranglehold, and urgent plans

were put in place for Sir Thomas Felton to bring 2,000 reinforcements from

England. By January, though, it had become apparent that the Duke of Brittany

was reconciled to the new French king Charles VI, and with the alliance

collapsing and dysentery ravaging his men, Woodstock abandoned the siege.

1397

Seventeen years

after the French campaign in which Richard Farndale likely took part, Ralph Neville, John Neville’s son, supported Richard

II's proceedings against Richard’s former commander Thomas of Woodstock and the Lords Appellant, and by way

of reward was created Earl of Westmorland on 29 September 1397. Richard

Farndale was an inhabitant of Sheriff Hutton in the lands of Ralph Neville.

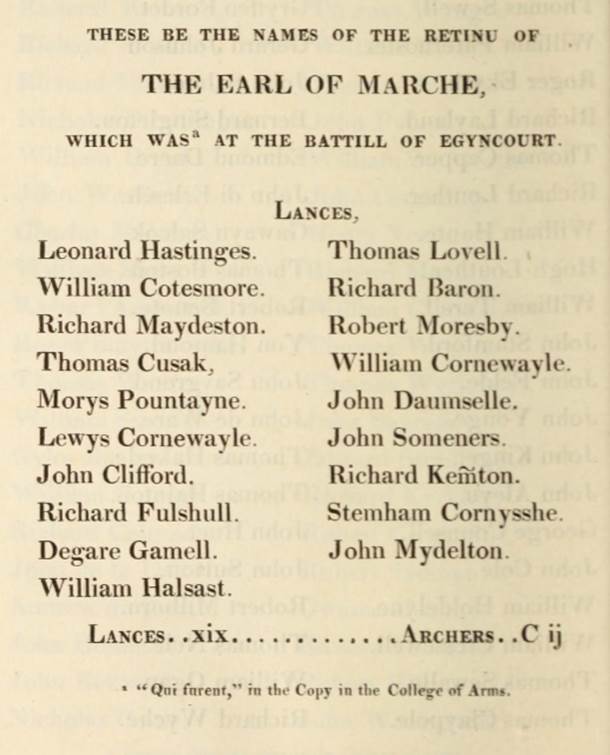

Joint

administration of his father’s Will was

granted on 13 March 1397 or 1398, so he may have been about 40 then, as the

eldest of three siblings.

Sheriff Hutton (Shyrefhoton)

1400

Given the likely

ages of his children, perhaps he married in about 1400. There is no mention of

his wife who may have pre-deceased him.

There was a

Richard Farendon who was archer and man at arms in a

Scottish Expeditionary Force who appeared in Retinue Lists on 24 June

1400. This could have been Richard. By this time he would have been in his

early forties. He held his horse and armour until his death in 1435, so it

seems likely that he became an experienced soldier who may have joined the many

armies of this time, when called upon to do so. The Nevilles were key players

in national affairs, so it seems likely that he would have been encouraged to

join national armies when called to do so.

The

English invasion of Scotland of August 1400 was the first military campaign

undertaken by Henry IV of England after deposing the previous king, his cousin

Richard II. Henry IV urgently wanted to defend the Anglo-Scottish border, and

to overcome his predecessor's legacy of failed military campaigns. A large army

was assembled slowly and marched into Scotland. Not only was no pitched battle

ever attempted, but the king did not try and besiege Scotland's capital,

Edinburgh. Henry's army left at the end of the summer after only a brief stay,

mostly camped near Leith (near Edinburgh) where it could maintain contact with

its supply fleet. The campaign ultimately accomplished little except to further

deplete the king's coffers, and is historically notable only for being the last

one led by an English king on Scottish soil.

Although

Henry had announced his plans at the November 1399 parliament, he did not

attempt a winter campaign, but continued to hold quasi-negotiations 'in

which he must have felt the Scots were profoundly irritating.' At the same

time, it appears that the House of Commons was not keen on the forthcoming war,

and, since extravagance had been a major complaint against Henry's predecessor,

Henry was probably constrained in requesting a subsidy. At this point, parliament

was clearly still opposed to a Scottish war, and may even have believed a

possible French invasion the imperative issue. In June 1400, the king summoned

his Duchy of Lancaster retainers to muster at York, and they in turn brought

their personal feudal retinues. At this point, with the invasion being obvious

to all, the Scots attempted to re-open negotiations. Although Scottish

ambassadors arrived at York to meet the king

around 26 June, they returned to Scotland within two weeks.

Although

the army was summoned to assemble at York on 24 June, it did not approach

Scotland until mid-August. This was due to the gradual arrival of army supplies

(in some cases, with much delay — the King's own tents, for example, were not

dispatched from Westminster until halfway through July). Brown suggests that

Henry was well aware of the delays these preparations would cause the campaign.

At some point before the army left for Scotland, the muster was met by the

Constable of England, Henry Percy, Earl of Northumberland, and the Earl

Marshal, Ralph

Neville, Earl of Westmorland. Individual leaders of

each retinue present were then paid a lump sum to later distribute in wages to

their troops: Men-at-arms received one shilling a day, archers half that, but

captains and leaders do not appear to have been paid at a higher rate.

Richard Farendale of Shyrefhoton came

from Sheriff Hutton in the lands

of Ralph Neville, so there is strong evidence that this was the same person as

Richard Farendon who joined these Scottish Wars..

The

army left York on 25 July 1400 and reached Newcastle-upon-Tyne four days later;

it was plagued by shortages of supplies, particularly food, of which more had

had to be requested before even leaving York. As the campaign progressed, bad

weather exacerbated the problem of food shortages, and Brown has speculated

that this was an important consideration in the short duration of the

expedition.

It

has been estimated that Henry's army was around 13,000 men, of which 800

men-at-arms and 2000 archers came directly from the Royal Household This was

"one of the largest raised in late medieval England;"

Brown notes that whilst it was smaller than the massive army assembled in 1345

(that would fight the Battle of Crécy), it was larger than most that were

mustered for French service. The English fleet also patrolled the east coast of

Scotland in order to besiege Scottish trade and to resupply the army when

required. At least three convoys were sent from London and the Humber, the

first of which delivered 100 tonnes of flour and ten tonnes of sea salt to

Henry's army in Scotland.

Henry

crossed the border in mid-August. Given-Wilson has noted the care Henry took

not to ravage or pillage the countryside on their march through Berwickshire

and Lothian. This was in marked contrast to previous expeditions, and

Given-Wilson compares it specifically to the 'devastation wreacked' in last such campaign, by Richard II in 1385.

This he puts this down to the presence in the English army of the earl of

Dunbar, whose lands they were. Brown has suggested the king envisaged ... a

punitive expedition' with either a confrontation or such a chevauchée

that the Scots would be eager to negotiate. In the event, they offered no

resistance as the English army marched through Haddington.

Common

during the Hundred Years War, the chevauchée was an

armed raid into enemy territory. With the aim of destruction, pillage, and

demoralization, chevauchées were generally conducted

against civilian populations.

However,

Henry's army never progressed further than Leith; there the army could keep in

physical contact with the supporting fleet. Henry took a personal interest in

his convoys, at one point even verbally instructing that two Scottish fishermen

fishing in the Firth of Forth were to be paid £2 for their (unspecified)

assistance. However, Henry never besieged Edinburgh Castle where the Duke of

Rothsay was ensconced. By now, Brown says, Henry's campaign had been reduced to

a 'war of words.'

By

29 August, the English army had returned to the other side of the border.

1402

Although

the 1400 campaign ended the Wars directly into Scotland, the Scvottish Wars

continued with encounters south of the Border. Shakespeare’s play Henry IV Part

1 opens with word brought to the King in about 1402, a few years in to the new

Lancastrian dynasty of Henry Bolingbroke, son of John of Gaunt, then Henry IV,

of the Wars with Wales and Scotland.

The

Battle of Holmedon Hill was a battle between English

and Scottish armies on 14 September 1402 in Northumberland. The battle was

recounted in Shakespeare's Henry IV, part 1.

Here

is a dear, a true-industrious friend,

Sir

Walter Blunt, new lighted from his horse,

Stained

with the variation of each soil

Betwixt

that Holmedon and this seat of ours,

And

he hath brought us smooth and welcome news.

The

Earl of Douglas is discomfited;

Ten

thousand bold Scots, two-and-twenty knights,

Balked

in their own blood, did Sir Walter see

On Holmedon’s plains. Of prisoners Hotspur took

Mordake,

Earl of Fife and eldest son

To

beaten Douglas, and the Earl of Atholl,

Of

Murray, Angus, and Menteith.

And

is not this an honorable spoil?

A

gallant prize? Ha, cousin, is it not?

(Henry

IV Part 1, Shakespeare, Act 1, Scene 1)

We

don’t know whether Richard was still part of the army at this stage, but we get

a Shakespearean flavour of these times.

1415

It is possible

that, as a veteran soldier, Richard might have later fought in Henry V’s

Agincourt campaign.

I

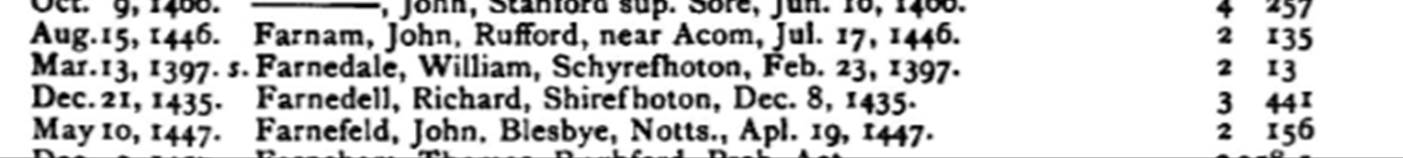

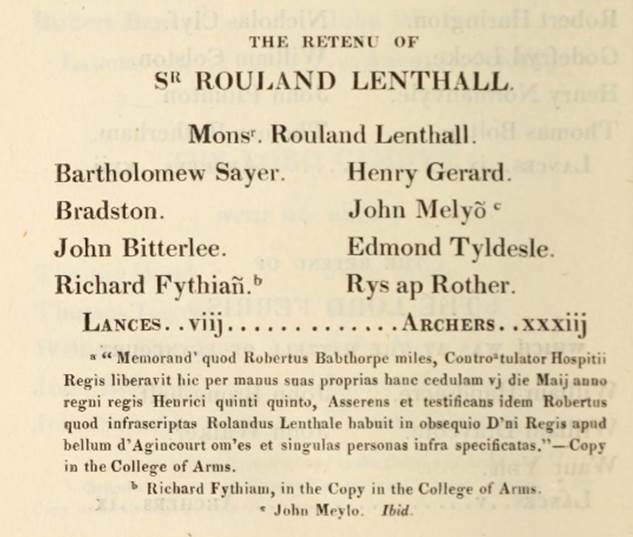

haven’t yet found him in the list of known soldiers at Agincourt. Sir Nicholas Harreis’

History of the battle of Agincourt, and of the expedition of Henry the Fifth

into France, in 1415; with The roll of the men at arms, in the English army,

1832 includes a Roll of the men at arms at Agincourt, p394. There is

no Richard Farendale listed, unless he was Richard Fulshull (p336), a Lancer in the retinue of the Earl of

Marche, or Richard Fythian (p344). It doesn’t seem

likely that these were the same man.

But to these lists of named individuals were unnamed lists of

lances and archers, so he could have been amongst these ordinary unlisted

soldiers. And if he wasn’t at Agincourt, he may have been in the other battles

in those French campaigns. Living firmly within the Neville lands, it seems

likely that he would have fought in the King’s battles with France. The family

also originated from the lands of the wife of the Black Prince and the lands of

the Stutevilles and the Mowbrays.

Background to Agincourt

After the Norman Conquest, a subject of the King of

France was also King of England. The Dukes of Normandy were frequently in

dispute with their neighbours, including the Dukes of Brittany. By the

thirteenth century, the French noble lines were eager to drive out the English

from their Norman lands. During John’s reign, the English lost their Norman

lands, and from the reign of Henry III, there was a desire to win back the

Norman lands. Edward III died in 1377 having failed to do so, his son the Black

Prince having died in 1376, leaving Richard II as King, to be overthrown by

Henry IV of the Lancastrian line., who reign was marred by constant civil war.

When Henry V became King in 1413, his ambitions to

restore English interests in France would also serve to unite the warring

factions at home.

The Agincourt campaign

In 1415, the 29 year old Henry V launched his

invasion of Normandy. He landed not on the wider French lands, but in Normandy,

reinforcing his ambitions to restore the lands which the English believed to be

theirs. He landed with a huge army of 12,000 men.

A quarter of those were men at arms, who wore heavy

armour and had a horse. Men at arms were paid 1s to 2s a day, depending on

their status.

Three quarters of the force were archers, paid only

6d a day. They were cheaper, and acted as a force multiplier. They were armed

with the longbow. They could should a rapid rates (12 to even 20 arrows a

minute), accurately over long distances.

Henry’s army initially besieged the town of

Harfleur, which is modern day Le Havre, at the mouth of the Seine, the launch

site of previous Viking raids on Paris. There was a long siege at Harfleur,

and Henry V directed the siege himself, using artillery effectively against the

walls. The inhabitants of Harfleur eventually surrendered.

The siege of Harfleur ended in September as the

campaigning season was coming to an end. However Henry V decided to march home

through Normandy via Calais, perhaps to demonstrate his new hold on Normandy.

He challenged the rather pacific and lazy Dauphin to single combat, which was

declined. Henry left perhaps 1,200 men to garrison Harfleur and had lost

perhaps 2,000, so he had perhaps 8,000 left.

|

Once more unto the breach,

dear friends, once more, Or close the wall up with our

English dead! In peace there’s nothing so

becomes a man As modest stillness and

humility, But when the blast of war

blows in our ears, Then imitate the action of the

tiger: Stiffen the sinews, summon up

the blood, Disguise fair nature with

hard-favored rage, |

Then lend the eye a terrible

aspect, Let it pry through the portage

of the head Like the brass cannon, let the

brow o’erwhelm it As fearfully as doth a gallèd rock O’erhang and jutty his confounded base Swilled with the wild and

wasteful ocean. Now set the teeth, and stretch

the nostril wide, Hold hard the breath, and bend

up every spirit |

To his full height. On, on,

you noblest English, Whose blood is fet from fathers of war-proof, Fathers that, like so many

Alexanders, Have in these parts from morn

till even fought, And sheathed their swords for

lack of argument. Dishonor not your mothers. Now attest That those whom you called

fathers did beget you. Be copy now to men of grosser

blood |

And teach them how to war. And

you, good yeomen, Whose limbs were made in

England, show us here The mettle of your pasture.

Let us swear That you are worth your

breeding, which I doubt not, For there is none of you so

mean and base That hath not noble luster in your eyes. |

I see you stand like

greyhounds in the slips, Straining upon the start. The

game’s afoot. Follow your spirit, and upon

this charge Cry “God for Harry, England,

and Saint George!” |

(Henry V, Shakespeare, Act 3, Scene 1,

The Gates of Harfleur)

The French army blocked the English advance on the

Somme, but the English crossed. The armies eventually met around 45 miles south

of Calais, at Agincourt. Henry placed his bowmen in a V shape on either

flank. The l,ongbowmen were a known threat to the

French. A tradition evolved after the battle that the French threatened to cut

off the middle two fingers of any bowmen captured to stop them firing again,

and the archers responded to the French with the defiant V sign. The French

planned to take the archers with their cavalry, but Henry ordered his archers

to take the initiative to advance until they were in range and then fire into

the French horses and soldiers, depriving them of the opportunity.

|

We would not die in that man’s

company That fears his fellowship to

die with us. This day is called the feast

of Crispian. He that outlives this day and

comes safe home Will stand o’ tiptoe when this

day is named |

And rouse him at the name of

Crispian. He that shall see this day,

and live old age, Will yearly on the vigil feast

his neighbors And say “Tomorrow is Saint

Crispian.” Then will he strip his sleeve

and show his scars. |

Old men forget; yet all shall

be forgot, But he’ll remember with

advantages What feats he did that day.

Then shall our names, Familiar in his mouth as

household words, Harry the King, Bedford and

Exeter, Warwick and Talbot, Salisbury

and Gloucester, Be in their flowing cups

freshly remembered. |

This story shall the good man

teach his son, And Crispin Crispian shall

ne’er go by, From this day to the ending of

the world, But we in it shall be rememberèd— We few, we happy few, we band

of brothers; |

For he today that sheds his

blood with me Shall be my brother; be he

ne’er so vile, This day shall gentle his

condition; And gentlemen in England now

abed Shall think themselves

accursed they were not here, And hold their manhoods cheap whiles any speaks That fought with us upon Saint

Crispin’s day. |

The French lost perhaps 10,000 whilst the English

were said to have lost only 100 to 200. Amongst the dead was Richard Duke of

York, father of Richard of York who would become to nemesis of the

Lancastrians, but at this stage the Yorkists were loyal to the King.

After the victory, Henry marched to Calais and

besieged the city until it fell soon afterwards, and the king returned in

triumph to England in November and received a hero's welcome. The brewing

nationalistic sentiment among the English people was so great that contemporary

writers described first hand how Henry was welcomed

with triumphal pageantry into London upon his return. These accounts also

describe how Henry was greeted by elaborate displays and with choirs following

his passage to St. Paul's Cathedral.

Henry V returned to London in triumph and paraded like a Roman Emperor.

Support for the King mean that Parliament eagerly voted new taxes to fund

further campaigns against the French. Agincourt also fomented support for the

new Lancastrian dynasty.

1417

The 1417 campaign

The victorious conclusion of Agincourt, from the

English viewpoint, was only the first step in the campaign to recover the

French possessions that Henry felt belonged to the English crown. Agincourt

also held out the promise that Henry's pretensions to the French throne might

be realized. Henry V returned to France in 1417 to establish his reconquest of

Normandy.

Richard Farndale was descended from the poachers

of Pickering Forest only a hundred years previously. It was such men who certainly

inspired the stories of Robin Hood and whose

archery skills would foresee the bowmen of ordinary folk who would one day

fight at Agincourt.

Richard might have been about 58 years old by this stage, so if he

was part of a medieval army, he would have been an old soldier. However if it

was he who had fought in France in 1380 and in Scotland in 1400, it is likely

that this old soldier had become a campaign warrior. His impressive armoury

which he left at his death suggests an old campaigner who had risen to possess

the armoury of a man at arms. He seems to have alternated between being an

archer and a man at arms.

There is a separate page which explores possible

candidates for Farndale ancestors amongst medieval armies.

There was a

Richard Farndon who was an archer mustered in the Garrison at Harfleur under

Thomas Beaufort, Earl of Dorset and Duke of Exeter in 1417. The Siege

of Harfleur from 17 August to 22 September 1415 had preceded the Battle

of Agincourt on 25 October 1415. So the town would have been garrisoned in

the following years. It was at the gates of Harfleur that Henry V had delivered

his inspiring speech in 1415:

Could Richard

Farndale of Sheriff Hutton have been inspired by Henry’s words? It is tempting

to think that Richard might have participated in the wider campaign from 1415

to 1421. If he was indeed a semi professional

soldier, this seems likely. On the other hand, he may have joined the post

Agincourt campaign in 1417. It might be that after the losses sustained during

the 1415 campaign, older veteran soldiers were called upon to fill gaps in the

ranks, which might make sense of Richard forming part of the post Agincourt

garrison at Harfleur.

The 1417 record

of Richard Farndon at Harfleur might indicate that Richard Farndale, who we

know from his will was a military man, was an old veteran fighting in those

campaigns, either part

of the 1415 Agincourt campaign and continuing in the wars that followed, or

joining the English force after Agincourt in their subsequent campaign up to

1421.

The principal

consolidated source for participation in the Agincourt campaign is the

University of Southampton databases on the

English Army in 1415 in their data on the Soldier in Medieval England.

1419

The

victory at Agincourt inspired and boosted the English morale, while it caused a

heavy blow to the French as it further aided the English in their conquest of

Normandy and much of northern France by 1419. The French, especially the

nobility, who by this stage were weakened and exhausted by the disaster, began

quarrelling and fighting among themselves. This quarrelling also led to a

division in the French aristocracy and caused a rift in the French royal

family, leading to infighting.

Margorie

Farndale (executor to Richard’s will) might have been

born in about 1419 (FAR00049).

Her birth date is estimated, so whilst she could have been conceived during

some home leave if Richard was engaged throughout the Agincourt campaign, or

her year of birth might have been different if Richard was campaigning

throughout.

1420

By

1420, a treaty was signed between Henry V and Charles VI of France, known as

the Treaty of Troyes, which acknowledged Henry as regent and heir to the French

throne and also married Henry to Charles's daughter Catherine of Valois.

1421

Agnes Farndale, Richard’s second daughter, might

have been born in about 1421 (FAR00050).

Richard Farendon or Farndon appeared again in the list of medieval soldiers,

as part of a Standing Force in France as a foot soldier (Man at arms) and as an

archer, under Richard Woodville the elder (1385 to 1441) and Richard Baurchamp,

Earl of Warwick.

1421 was the year

of the Battle

of Bauge, the defeat of the Duke of Clarence and his English army by the

Scots and French army of the Dauphin of France. The battle took place on 22

March 1421 during the Hundred Years War. The Duke of Clarence, King Henry V’s

younger brother commanded the English army. The Earl of Buchan commanded the

Franco-Scottish army. The English army numbered around 4,000 men, of whom only

around 2,500 men took part in the battle. The Franco-Scottish army comprised

5,000 to 6,000 men.

On the other hand

Richard Woodville (or Wydeville) (later the First

Lord Rivers and father of Elizabeth Woodville later wife of the Yorkist Edward

IV), under whom Richard Farendon served, was granted

various domains, lordships and bailiwicks in Normandy in 1419 and 1420,

culminating in 1421 with appointment as Seneschal of the province of Normandy.

Richard

Beauchamp, 13th Earl of Warwick held high command at sieges of French towns

between 1420 and 1422, at the sieges of Melun in 1420, and of Mantes, to the

west of Paris, in 1421-22. The more significant siege was of Meux to the east

of Paris.

In

1420 the town of Melun in France surrender to King Henry V. The siege had

rumbled on since June and had been fairly dramatic at times, with close combat

taking place literally beneath the walls as the besiegers and the garrison dug

mines and countermines in an attempt to bring the siege to an end. James I of

Scotland was present at the siege, brought to France in 1420 to be Henry's

trump card against the Scots serving on the Continent.

Siege

of Melun from a late 14th century manuscript

The

siege of Meaux was fought from October 1421 to May 1422 between the English and

the French during the Hundred Years' War. Paris was threatened by French

forces, based at Dreux, Meaux, and Joigny. The king

besieged and captured Dreux quite easily, and then went south, capturing Vendôme and Beaugency before

marching on Orléans. Henry then marched on Meaux with an army of more than

20,000 men. The town's defence was led by the Bastard of Vaurus,

by all accounts cruel and evil, but a brave commander all the same. The siege

commenced on 6 October 1421, mining and bombardment soon brought down the

walls. Many allies of King Henry were there to help him in the siege. Arthur

III, Duke of Brittany, recently released from an English prison, came there to

swear allegiance to the King of England and serve with his Breton troops. Duke

Philip III of Burgundy was also there, but many of his men were fighting in

other areas: In Picardy, Jean de Luxembourg and Hugues de Lannoy,

master of archers, accompanied by an Anglo-Burgundian army attacked, in late

March 1422 and conquered several places in Ponthieu and Vimeu

despite the efforts of troops of Joachim Rouhault

Jean Poton de Xaintrailles

and Jean d'Harcourt while in Champagne, Count Vaudemont was defeated in battle by La Hire. Casualties

began to mount in the English army, including John Clifford, 7th Baron de

Clifford who had been at the siege of Harfleur, the Battle of Agincourt, and

received the surrender of Cherbourg. Also killed in the siege was 17-year-old

John Cornwall, only son of famous nobleman John Cornwall, 1st Baron Fanhope. He died next to his father, who witnessed his

son’s head being blown off by a gun-stone. The English also began to fall sick

rather early into the siege, and it is estimated that one sixteenth of the

besiegers died from dysentery and smallpox while thousands died thanks to the

courageous defence of the men-at-arms inside the city. As the siege continued,

Henry himself grew sick, although he refused to leave until the siege was

finished. Good news reached him from England that on 6 December, Queen

Catherine had borne him a son and heir at Windsor. On 9 May 1422, the town of

Meaux surrendered, although the garrison held out. Under continued bombardment,

the garrison gave in as well on 10 May, following a siege of seven months. The

Bastard of Vaurus was decapitated, as was a trumpeter

named Orace, who had once mocked Henry. John Fortescue was then installed as

English captain of Meaux Castle.

It seems likely

that Richard Farndale took part in some or all of these siege campaigns around

Paris in 1421.

If these records

are indeed Richard Farndale of Sheriff Hutton, then he appears to have been an

old soldier who campaigned with Henry V, and perhaps built up his small wealth

on campaign.

1422

Henry V died in 1422 and

left a nine month old baby son, Henry VI. The inter noble rivalry

would soon pick up again.

Henry VI had no father

to guide him to Kingship and he relied on his advisors. He became timid and

passive and focused on religion. At this point in history, the nobility needed

strong leadership to control their ambitions. After the expensive battles in

France, financial resources were depleted. The young king was easily controlled

by the rival noble families.

This unpopularity would

ferment displeasure with the Lancastrian dynasty, which under Henry V had been

so popular, and would give stir up a Yorkist uprising.

The Yorkist cause was

most strongly supported by the Nevilles of Sheriff Hutton. Cecily Neville

married Richard, Duke of York, the main protagonist of the Yorkist cause. Their

son, Edward IV would found the Yorkist dynasty in 1461. Richard Neville, Earl of

Warwick, the King Maker, was the main political strategist to the Yorkist

cause, at least in the early stages of the Wars of the Roses.

Richard

was about 65 by this time, too old perhaps to take an active role himself.

However he lived in Sherif Hutton, at the heart of the cauldron that started to

bubble amongst the Yorkists. As a proud old soldier of Henry V he was likely to

have been appalled at the failures of Henry VI, stirred on no doubt by his

landlords, the Nevilles. In the last dozen years of his life, we can imagine

Richard over dinner with his daughters spitting with rage at where things had

got to under Henry VI, and yearning for the new glamour of the Yorkist cause.

In an old chest in his bedroom perhaps, his armour of bascinet, breastplate and

arm and leg fittings must have lain. His grey horse rested in the stables. He

probably would have put them on and rode out with the Nevilles if he had been

asked to do so.

However

at this stage Henry VI was just a young King, not yet a hopeless adult one and

the Wars of the Roses did not kick off until 1455, twenty years after Richard’s

death. He would leave his three daughters to live through the years of Yorkist

and Lancastrian rivalry. We only know their names. Perhaps they were passive

witnesses to the events which would follow. Perhaps their husbands and their

sons engaged in those Wars. We don’t know.

Richard’s

armour was bequeathed to the church, to pay for his funeral. Perhaps when the

civil war kicked off, they were taken by some other man at arms who likely

fought with the Yorkists, under the Neville banner.

1423

Alice Farndale, his third daughter, might have

been born in about 1423 (FAR00051).

1435

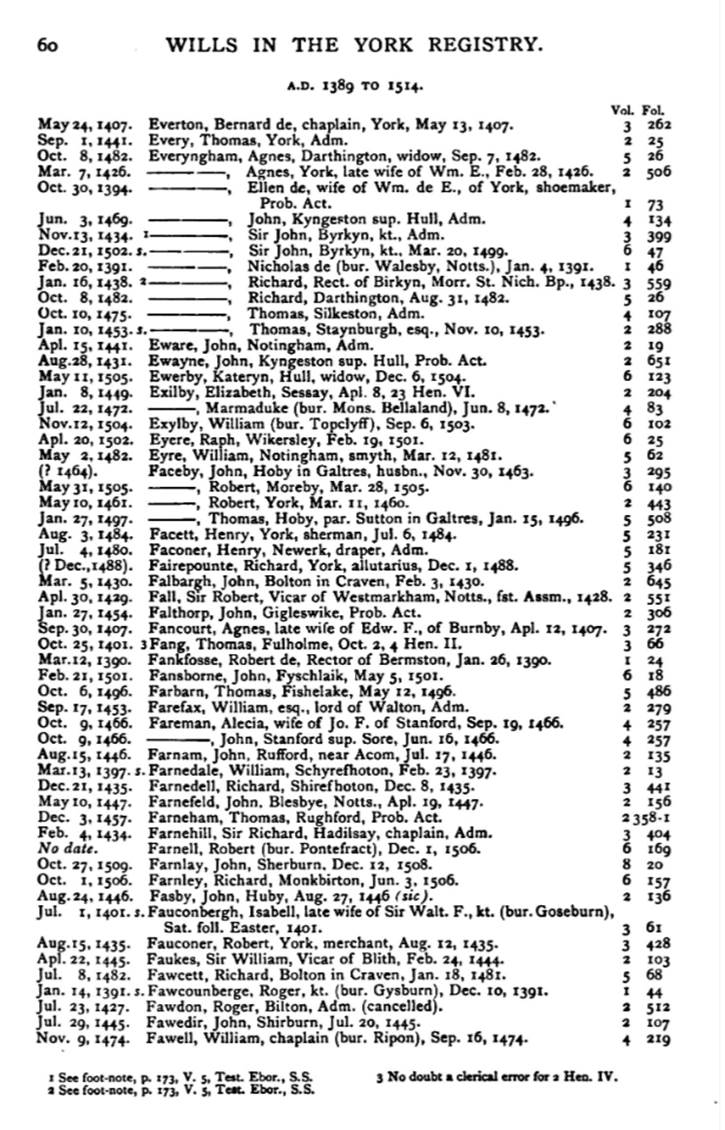

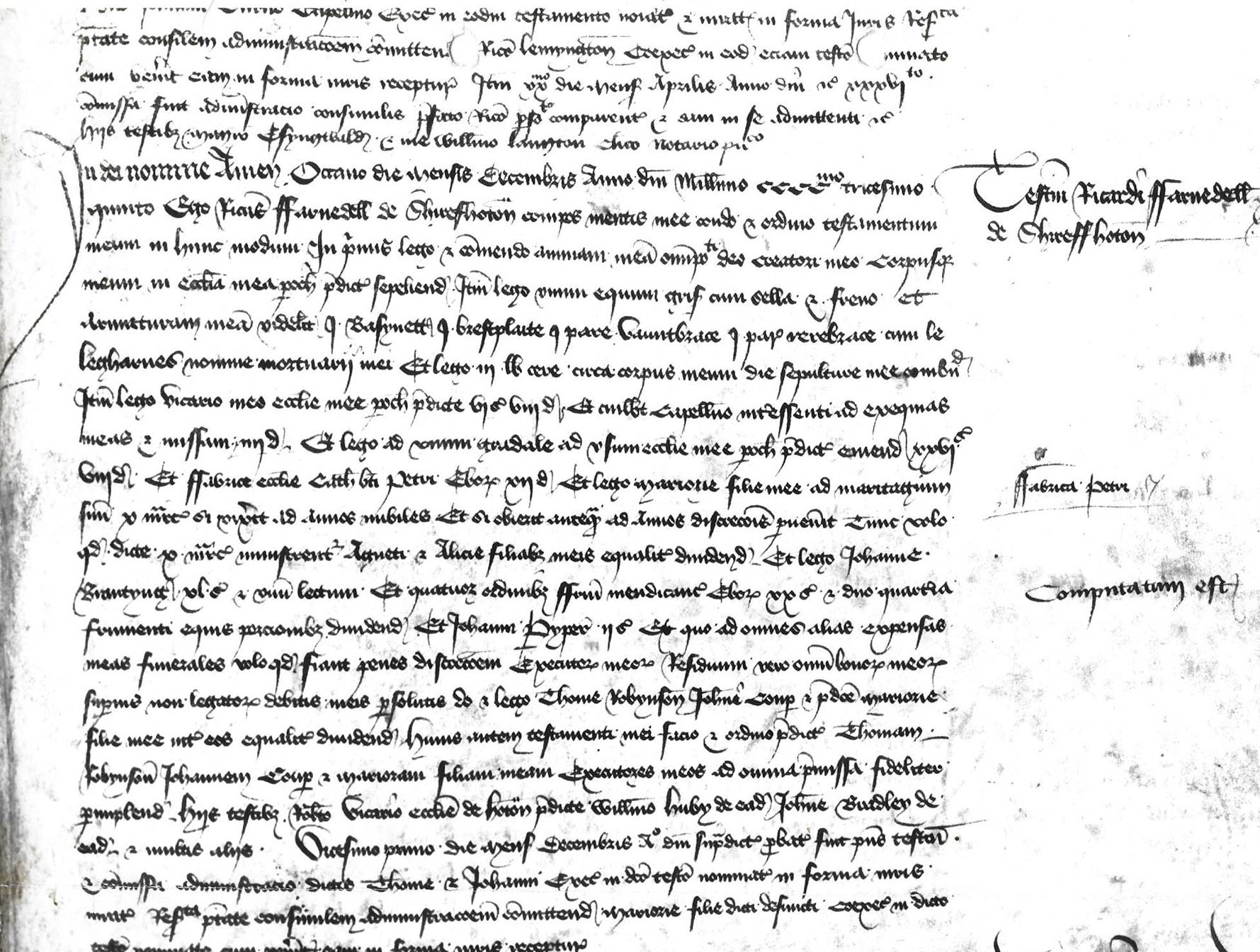

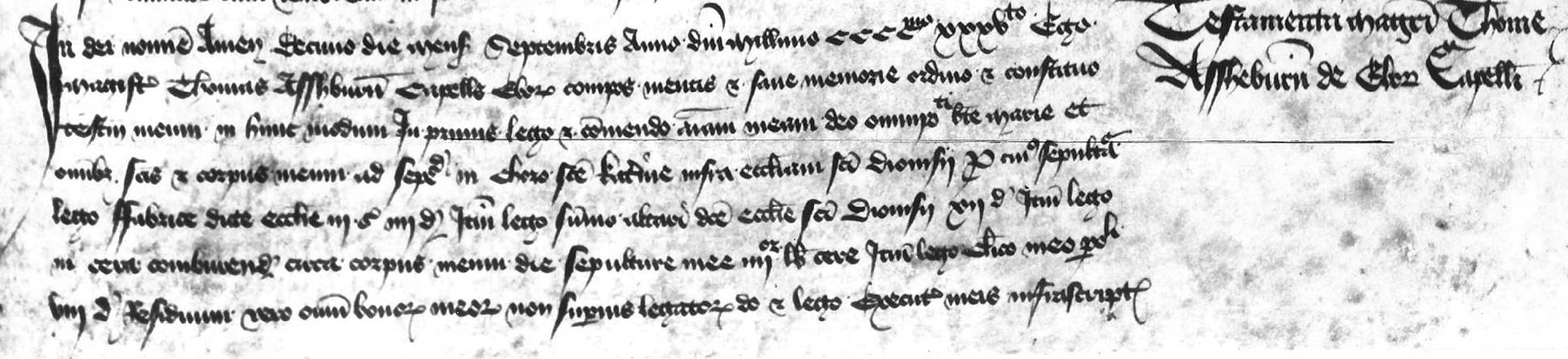

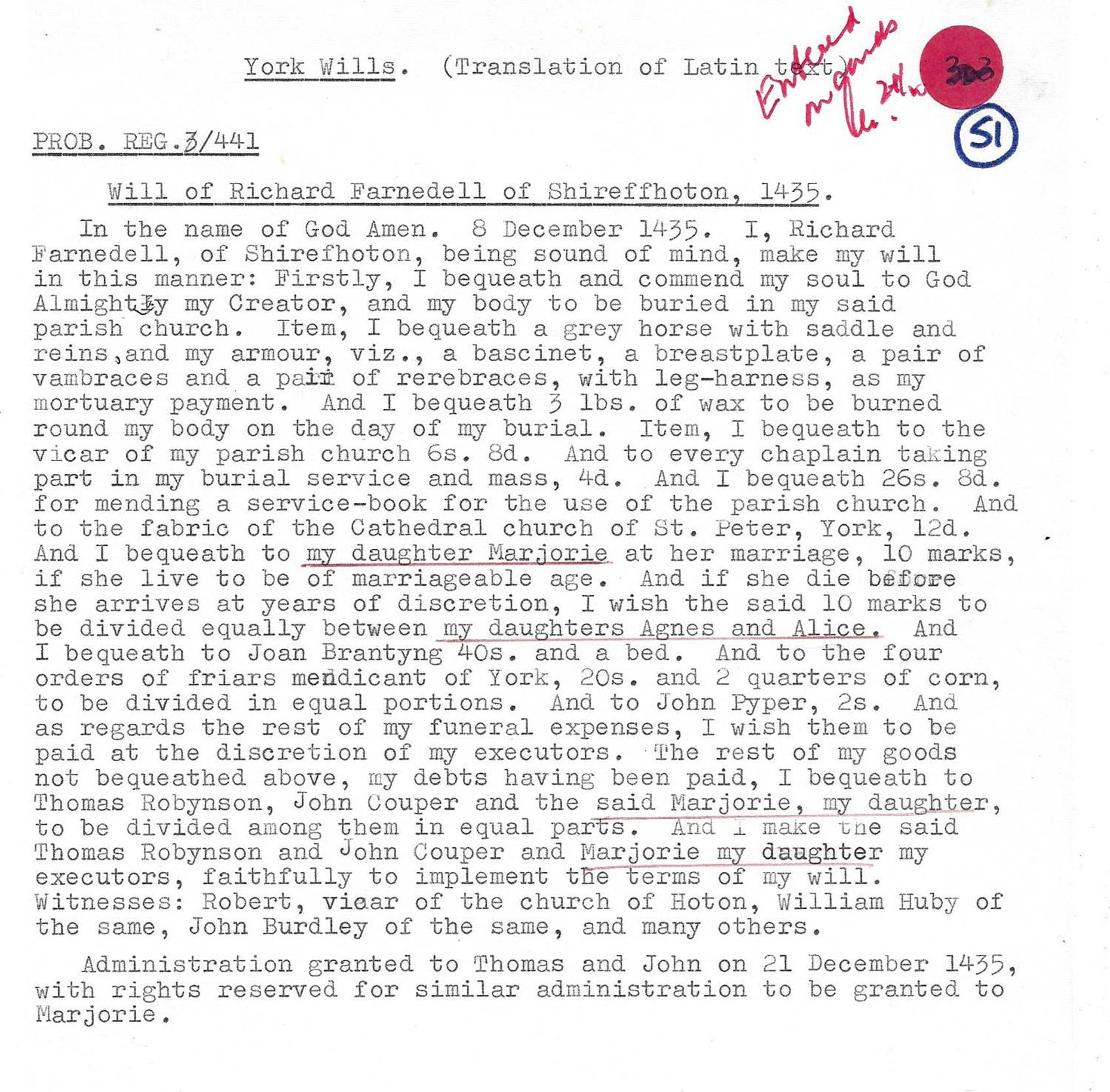

The Will of Richard Farendale, proved at

Sherifhoton 21 Dec 1435.

‘In the name of God Amen, 8th December 1435. I Richard Farndell

being of sound mind make my will in this manner. Firstly, I bequeath and

Commend my soul to God Almighty, My Creator, and my body to be buried in my

said Parish Church.

Item. I bequeath a grey horse with saddle and

reins and my armour, viz: a bascinet, a breast plate, a pair of vembraces and a

pair of rerebraces with leg harness as my mortuary payment. And I bequeath 3

lbs of wax to be burned around my body on the day of my burial.

Item. I bequeath to the Vicar of my Parish Church

6s 8d and to every chaplain taking part in my burial service Mass, 4d.

And I bequeath 26s 8d for mending a service

book for the use of the parish church.

And to the fabric of the Cathedral Church of

St Peter York, 12d.

And I bequeath to my daughter Margorie at her

marriage 10 marks, if she live to be marriageable age. And if she die before

she arrives at her years of discretion, I wish the said 10 marks to be divided

equally between my daughters Agnes and Alice.

And I bequeath to Joan Brantyng 40s and a bed.

And to the four orders of friars mendicant of

York 20s and two quarters of corn to be divided in equal portions.

And to John Pyper 2s.

And as regards the rest of my funeral

expenses, I wish them to be paid at the discretion of my executors.

The rest of my goods, not bequeathed above, my

debts having been paid, I bequeath to the said Margorie, my daughter, to be

divided among them in equal parts.

And I make the said Thomas Robynson and John

Couper and Margorie my daughter, my executors, faithfully to implement the

terms of my will.

Witnesses; Robert, Vicar of the Church of Hoton,

William Huby of the same, John Burdley of the same and many others.’

Administration granted to Thomas and John on 21st

December 1435 with rights reserved for similar administration to be granted to

Margorie.

(Translated from Latin text of Will held at York.

Prob. Reg. 3/441).

Richard Farndale therefore died between 8 and 21

December 1435.

York Prerogative & Exchequer Courts, Will;

Language: Latin; Will date: 8 Dec 1435; Probate date: 21 Dec 1435; Reference code: ProbReg 3; Folio: 441r, York Medieval

Probate Index, 1267-1500

(York Wills)

Richard’s Armour and horse:

His grey Horse

His bascinet His

breastplate

His vambraces His rerebraces

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|