Act 10

Medieval Warfare

The story of our soldier ancestors,

Archers and Men and Arms of the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, who joined

the armies of Richard II, Henry IV and Henry V

|

This

is a new experiment. Using Google’s Notebook LM, listen to an AI powered

podcast summarising this page. This should only be treated as an

introduction, and the AI generation sometimes gets the nuance a bit wrong.

However it does provide an introduction to the themes of this page, which are

dealt with in more depth below. |

|

Orson

Welles takes us to the heart of medieval warfare in one of the epic medieval

battle scenes of cinema. |

Scene 1 – The Wars under Richard II

Domestic

tensions meet open hostility with France and Scotland

When Edward,

the Black Prince, died at Westminster on 8 June 1376, after long illness, he

left his widow, Joan the Fair Maid of Kent, descendant of House Stuteville, the Farndale overlords, to protect

their young son Richard, second in line to the throne and still only nine years

old. When Edward III died a year later on 21 June 1377, Joan was left to

manoeuvre through complex interests, to ensure her son’s coronation as Richard

II on 16 July 1377.

Edward III

had left an inheritance of instability in three potentially rival houses

amongst the proud Plantagenet descendants. The Crown passed to the senior royal

house of Richard II, protected by Joan. The House of York was a dormant threat

to the primary line, still to be awoken. The powerful House of Lancaster, whose

patriarch was John of Gaunt, was not so dormant. An uneasy truce during Richard

II’s minority ensued.

|

The

dynastic struggles of the Plantagenets, leading to the Wars of the Roses, the

events of which our ancestors were direct witnesses |

The Hundred

Years War had become embedded in the national psyche as permanent struggle with

France and their ally Scotland, since 1337, but after Crecy

and Poitiers,

the Treaty

of Bretigny of 1360 had marked an end to the

first phase of the struggle.

In 1369, on

the pretext that Edward III had failed to observe the terms of the treaty, the

king of France had declared war once again. By the time of the death of the

Black Prince in 1376 and the death of Edward III in 1377, English forces had

been pushed back into their territories in the southwest, around Bordeaux.

By 1383,

tensions between Richard II and John of Gaunt had been increasing over the

approach to the war in France. While the King and his court preferred

negotiation, Gaunt and Buckingham urged a large scale campaign to protect

English possessions. However Richard II chose to send what he called a crusade

led by Henry le Despenser, Bishop of Norwich, which

failed miserably. Faced with this setback on the continent, Richard turned his

attention instead towards France's ally, the Kingdom of Scotland.

The last

round of hostilities with Scotland had ended in 1357, with an agreement that

the English would occupy significant portions of southern Scotland, known as the

English pale. However by the time of

Edward III's deteriorating health and English military reverses in

France in the late 1370s, the Scots had begun to gradually recover much of this

territory. The Scottish government's standard diplomatic line was that this was

the work of over-mighty magnates who were not under control of the Scottish

Crown. In reality the Scottish Crown were probably coordinating attacks on

English-held territory. By the early 1380s the over-mighty magnates

excuse was wearing a bit thin, and lost all credibility when in 1384 the Scots,

whose confidence had been boosted by a decade and a half of small scale

successes, turned to open war with England.

In February

1384, a Scottish force led by Archibald Douglas the Grim, Lord of

Galloway, and supported by his cousin William, Earl of Douglas, and George

Dunbar, Earl of March, captured Lochmaben Castle, the former Annandale stronghold of

the House Brus. With Lochmaben, the English lost Annandale, the seat of the

Scottish line of the Bruce family, their last remaining possession in the west

of Scotland.

This

Scottish military activity could no longer go unanswered and an expedition by

John of Gaunt was organised in some haste.

Farndale

soldiers in the Scottish Wars

On 3 April

1384, an English army entered into Scotland under the command of John of Gaunt,

in direct response to the fall of Lochmaben Castle.

On the retinue roll on 18 January and 1 February 1384 was John Farndale, of

the line of Farndales who had settled

in York. He served under John of Gaunt’s overall command, and under the

captaincy of Henry Percy, Sir William Fulthorpe and

Walter FitzWalter.

John of

Gaunt (1340 to 1399) was the Lancastrian patriarch, whose son Henry Bolingbroke

seized the throne from Richard II two decades later. In the 1380s, the

Lancastrians were still loyal to the Crown. Gaunt was the King’s uncle, and he

felt responsibility for success of his nephew after his brother, the Black

Prince’s premature death. Yet he was growing increasingly frustrated at

everything his nephew did and tensions were growing between John of Gaunt and

the King.

Henry Percy

(1364 to 1403), known as Harry Hostpur was an English

knight who fought in several campaigns against the Scots on the northern border

and against the French during the Hundred Years' War. The nickname Haatspore or Hotspur was given to him

by the Scots as a tribute to his speed in advance and readiness to attack. The

heir to the leading Percy family in northern England, rivals to the Nevilles of Sheriff Hutton, Hotspur

was to be one of the earliest and primary movers behind the deposition of King Richard

II in favour of Henry Bolingbroke in 1399. His nickname was later adopted by

Tottenham Hotspur FC.

Walter

FitzWalter (1368 to 1406) came from the noble FitzWalter family, with estates

in Essex and elsewhere.

John Farndale was

part of John of Gaunt's army as it marched up the east coast, burning

Haddington and then Leith. The Scots had become adept at a scorched earth

policy whenever the English invaded, and John of Gaunt's men seem to have

struggled to find ways to overcome the Scots strategically. John of Gaunt

himself showed reticence in causing damage. He is known to have spared the

abbeys of Melrose and Holyrood from destruction. In 1381 John of Gaunt had

briefly fled to Scotland to escape the Peasants' Revolt, and this might have

given him some sympathies within Scotland. At that time, John of Gaunt seems to

have resided mostly at Holyrood, hosted by John, Earl of Carrick, the future

Robert III of Scotland. John of Gaunt had been considered as a possible

successor to David II of Scotland back in the 1360s, and in 1384 he may still

have harboured vain hopes of some day pressing his

claim to be King of Scots. Nevertheless, John of Gaunt extracted a hefty sum of

money from the citizens of Edinburgh to spare the town from harm, and this

agreement may have included the condition for Holyrood’s safety.

In all, the

English spent less than three weeks in Scotland, and by 23 April 1384 Gaunt was

in Durham handing responsibility for the defence of the marches to Henry Percy

(1341 to 1408), the First Earl of Northumberland, Harry Hotspur’s dad.

Later in

1384, the Scots resumed their aggressive policy towards England, this time with

the Earl of Douglas bringing Teviotdale back under Scottish control.

In 1385, the King himself led a punitive expedition to the north. John Farndale was probably a soldier in this second expedition, probably directly under Harry Hotspur’s command. The English King had only recently come of age, and it was expected that he would play a martial role just as his father, Edward the Black Prince, and grandfather Edward III had done.

On 8 July 1385 a force of French knights had marched south from Edinburgh wearing black surcoats with white St Andrew's crosses sewn on, alongside 3,000 Scottish soldiers. However the Scots hosts were not so cooperative with the French and relations deteriorated between them. The threat was repulsed by a counterattack from Henry Hotspur. John might have been involved in that counter attack.

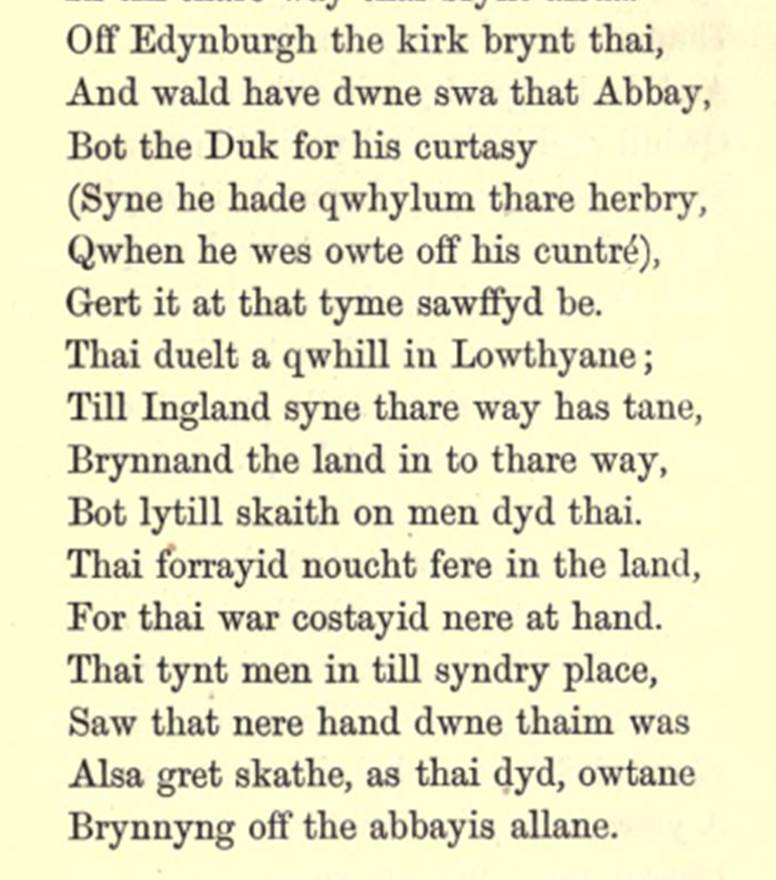

On 11 August

1385 the English army entered Edinburgh, which was deserted by then. Three days

earlier Richard had received news from London that his mother, Joan, Countess

of Kent, his principal mentor, had died the previous day. Most of Edinburgh was

set alight, including St Giles' Kirk. According to the contemporary chronicler Andrew

of Wyntoun in his Cronykil

of Scotland, the English army was given free and uninterrupted play for

slaughter, rapine and fire-raising all along a six-mile front. However

there was indecision amongst

the English military command whether to proceed or withdraw and the campaign

came to nothing. The army had to return without ever engaging the Scots in

battle.

From the Cronykill of Scotland

Meantime the

French threatened an invasion of southern England.

John of

Gaunt remained in the north to oversee a new truce with Scotland, after the

King returned to England, but the relationship between the Lancastrian John of

Gaunt and Richard II was worse than it had ever been. In 1386 John of Gaunt

left for the Continent to pursue his claim to the throne of Castile, which

efforts would come to nothing.

Two years

later, in 1388, Richard II was aged 21 and starting to establish some authority

when the north of England fell victim to another Scottish incursion. The

Battle of Otterburn took place on 5 August 1388 as part of the continuing

border skirmishes between the Scots and English. A Scottish attack on Carlisle

Castle was timed to take advantage of divisions on the English side between Ralph Neville, 1st Earl of Westmorland

and Henry Percy, 1st Earl of Northumberland who had just taken over defence of

the border and partly in revenge for King Richard II's invasion of Scotland of

1385.

Henry Percy

Senior, the First Earl, again sent his sons Harry Hotspur and Sir Ralph Percy

to engage with the Scots, while he stayed at Alnwick to cut off the Scottish

retreat. Despite Percy's

force having an estimated three to one advantage over the Scots, Froissart

records 1,040 English were captured and 1,860 killed whereas 200 Scots were

captured and 100 were killed. The Westminster Chronicle estimates Scottish

casualties at around 500. Hotspur's rashness and eagerness to engage the Scots

might have added to the exhaustion of the English army after its long march

north.

The Scottish

ballad, the Battle of Otterburn mocked, It fell about the Lammas

tide, When the muir-men win their hay, The doughty Earl of Douglas rode Into

England, to catch a prey.

|

The

Scottish Ballad which mocked the English. |

In retort, the

English Ballad

of Chevy Chase told of Percy’s hunting party or Chase in the Cheviot

hills, as an allegory to his chevauchée into

Scotland.

John of

Gaunt returned to England in 1389 and settled his differences with the King,

after which the old statesman acted as a moderating influence on English

politics. Richard

assumed full control of the government on 3 May 1389, claiming that the

difficulties of the past years had been due solely to bad councillors. He

promised to lessen the burden of taxation on the people significantly. Richard

ruled peacefully for the next eight years, having reconciled with his former

adversaries.

John Farndale with his two brothers, Henry Farndale and William Farndale had another venture into Scotland in June 1389 when they

served under Thomas Mowbray. The

Mowbrays were still nominally feudal overlords of the lands of

Kirkbymoorside and Farndale,

John’s ancestral home, though effective control of those lands had long passed

to the House Stuteville, the

family from which the Fair Maid of Kent, Richard II’s mum, descended.

Thomas Mowbray had been with Richard II during the Scottish

invasion of 1385, but his friendship with the young King was waning. Richard

had a new favourite, Robert de Vere, and Mowbray became increasingly close to

Richard Fitzalan, Earl of Arundel. The King already distrusted Arundel, and

Mowbray's new circle included the equally estranged Thomas of Woodstock, Duke

of Gloucester. Together they plotted against the King's chancellor, the Duke of

Suffolk who was impeached, and a council was appointed to oversee the king’s

increasingly distrusted administration. However Mowbray gradually became

disillusioned with his comrades and by 1389, he was back in the king's favour.

In early 1389 Mowbray’s estates were restored to him by the King and he was

pardoned for having married without the King's licence.

In March

1389, Thomas Mowbray was

appointed warden of the East March and castellan of Berwick Castle, receiving

wages of £6,000 in peacetime and twice that in time of war. This was the

context wherein John,

Henry and William Farndale

were part of the standing force in the East March of Scotland.

|

c1352 to c1425

John Farndale, and

his brothers Henry and William, were archers and men at arms called to fight

in Scotland in 1389 John was later a

butcher made freeman of York in 1408 |

However Thomas

Mowbray’s appointment was not a success and he fell out with the traditional

lord of the north, Henry Percy. Mowbray held no lands in the north and had few

contacts among the gentry, upon whom he needed to rely to raise his army.

Mowbray's tenure in the East March was effectively doomed from the start.

His

ineffectiveness became obvious in June 1389, when a Scottish incursion ravaged

the north of England and, with little opposition, went as far south as

Tynemouth. Mowbray, the Westminster Chronicle reports, refused the Scottish

offer of a pitched battle and retreated to Berwick Castle.

Thomas Mowbray was later banished by

Richard II after his rivalry with Henry Bolingbroke, in 1399, but died soon

afterwards in Venice.

Richard

Farndale and War with France during the reign of Richard II

Richard Farndale (c

1357 to 1435) was the son of William

and Juliana Farendale and was probably born at Sheriff Hutton, the

heart of the Neville lands, in about 1357, assuming that he was about 78 when

he died and 40 when he was an executor and beneficiary of his father’s will.

When he died

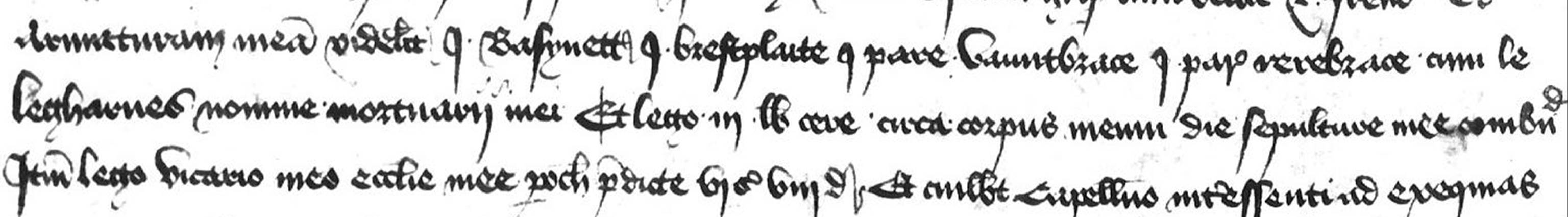

in 1435, he left his own will. His first bequest was that his impressive

collection of military equipment was to be used as his mortuary payment. He

left three daughters and no sons.

This

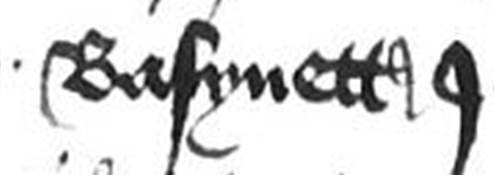

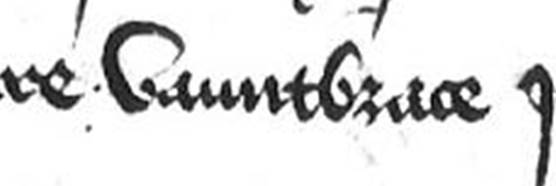

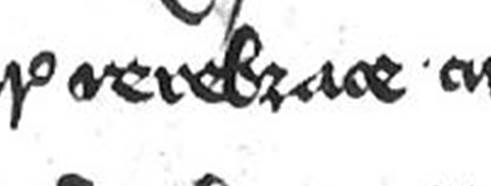

military bequest included a grey horse with saddle and reins and his armour,

comprising a bascinet, a breast plate, a pair of vembraces

and a pair of rerebraces with leg harness.

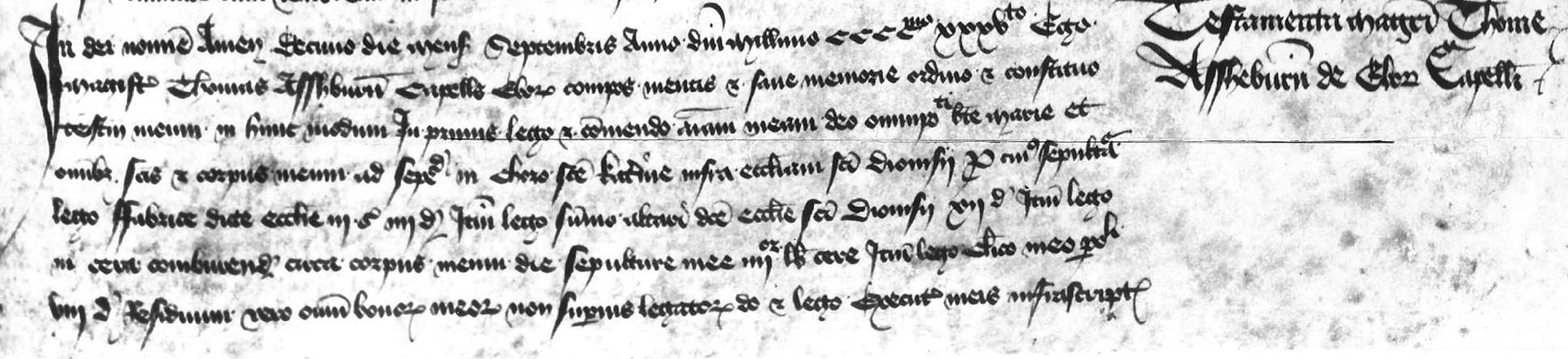

Extract

from Richard Farndale’s will of 1435

His grey

Horse

His bascinet

His breastplate

His vambraces His

rerebraces

A

bascinet was a medieval combat helmet Vembraces

or vambraces were armoured forearm guards

A rerebrace was a piece of armour designed to

protect the upper arms (above the elbow)

Richard was

impressively armed for military service when he died, so it seems certain that

he pursued a military career. He was a veteran soldier.

The Hundred

Years War with France lasted from 1337 to 1453. Before the Hundred Years War,

warfare was rooted to the principles of chivalry, which focused the exploits of

the nobility. By the 1320s experienced soldiers fought on foot alongside

commoners. Ideas of feudal service were replaced by professional soldiers, who

undertook operations contrary to the chivalric code including ambush, siege,

raids, looting, burning, and rape. The archers were the prime example of new

commoners’ forces, firing arrows which could easily penetrate knights’ armour,

upsetting the ancient equilibrium. The commoners were given opportunities to

accumulate significant wealth through war booty, and ransoms, as well as their

pay.

There was a

Richard Farnham or Farneham, listed in records of medieval

soldiers, who joined an expedition to France as an archer on 28 June 1380

under the captaincy of Sir William Windsor, and the command of Thomas of

Woodstock, Duke of Gloucester. It is not certain that this was him, because the

spelling of the surname is different, but this was a time of fluidity in

surname spellings. Given his military equipment listed in his will, 55 years

later, it seems likely that Richard would have started a military career at

about this time. He would have been about 23 at this time. Whilst we cannot be

certain, it is possible, perhaps even quite likely, that this was Richard in

his early military exploits in France.

1380 was in

the midst of a crisis in the French Wars in the time of Richard II. The

Peasant’s Revolt of 1381 arose due to high taxes required to fund the French

Wars. Richard II was not a popular King, and the cost of these French wars were

not welcomed at home.

Richard’s

commander, Thomas of Woodstock had been in command of a campaign in northern

France that followed the War of the Breton Succession of from 1343 to 1364.

During this campaign John IV, Duke of Brittany had tried to secure control of

the Duchy of Brittany against his rival Charles of Blois. John returned to

Brittany in 1379, supported by Breton barons who opposed the risk of annexation

of Brittany by France. An English army was sent under Thomas Woodstock to

support the Duke of Brittany. Due to concerns about the safety of a longer

shipping route to Brittany itself, the army was ferried instead to the English

continental stronghold of Calais in July 1380.

As Thomas

Woodstock marched his 5,200 men east of Paris, they were confronted by the army

of Philip the Bold, Duke of Burgundy, at Troyes. However the French had learned

from the Battle of Crécy in 1346 and the Battle of Poitiers in 1356 not to

offer a pitched battle to the English. Eventually, the two armies simply

marched away. French defensive operations were then thrown into disarray by the

death of King Charles V of France on 16 September 1380.

Woodstock's

army engaged in a chevauchée, a practice common during the

Hundred Years War, comprising an armed raid into enemy territory leading to

destruction, pillage, and demoralisation, generally conducted against civilian

populations. The English army chevauchéed

westwards largely unopposed, and in November 1380 the army laid siege to Nantes

and its vital bridge over the Loire towards Aquitaine. However, the army did

not succeed in establishing an effective stranglehold, and urgent plans were

put in place for Sir Thomas Felton to bring 2,000 reinforcements from England.

By January, though, it had become apparent that the Duke of Brittany was

reconciled to the new French King Charles VI, and with the alliance collapsing

and dysentery ravaging his men, Woodstock abandoned the siege.

So in 1380 Richard Farndale engaged in a spot of chevauchée in France and may well have benefitted

financially from doing so.

A

possible Irish campaign

There was a Richard Farnworth or Farnysworth who served in a standing force in Ireland under Sir John Stanley and mustered on 21 October 1389, and it is very probable that this was the veteran soldier of the French Wars. Richard II had assumed full control of the government on 3 May 1389, and this was a period of fragile peace.

Sir John

Stanley KG (c 1350 to 1414) of Lathom, near Ormskirk in Lancashire, was

Lord Lieutenant of Ireland. John Stanley had been appointed as deputy to Robert de Vere, Duke of

Ireland in 1386 after an insurrection created by friction between Sir Philip

Courtenay, the English Lieutenant of Ireland, and his appointed governor James

Butler, 3rd Earl of Ormond. Stanley led an expedition to Ireland on behalf of

de Vere and King Richard II to quell it. He was accompanied by Bishop Alexander

de Balscot of Meath and Sir Robert Crull. Butler

joined them upon their arrival in Ireland.

Because of

the success of the expedition, Stanley was appointed to the position of Lord

Lieutenant of Ireland, Alexander was appointed to Chancellor, Crull to be

Treasurer, and Butler to his old position as Governor. In 1389 Richard II

appointed Stanley as Justiciar of Ireland, a post he held until 1391. Stanley

was heavily involved in Richard's first expedition to Ireland in 1394 to 1395.

It is possible that Richard

Farndale was involved in these campaigns in Ireland in 1389.

First

signs of the peril of Richard II’s dynasty

Seventeen

years after the French campaign in which Richard Farndale

likely took part, Ralph Neville,

Lord of Sheriff Hutton,

supported Richard II's proceedings against Richard’s former commander Thomas of

Woodstock in an early sign that the King’s rule was unsafe. By way of reward

Ralph Neville was created Earl of Westmorland on 29 September 1397. However

Ralph had married the daughter of the Lancastrian John of Gaunt, and by the end

of the century the Nevilles had switched to oppose Richard II and to support a

new Lancastrian dynasty.

The soldier,

Richard Farndale

was also an inhabitant of Sheriff

Hutton in the lands of Ralph Neville, and he and his family were front seat

witnesses to the dynastic duels about to unfold.

Richard’s

father, William

Farndale died in 1398 and Richard was an executor with his mother, Juliana

and beneficiary of his father’s will made on 23 February 1398. He received a

legacy of £4 and, with his mother and sister Helen, the residue of his father’s

estate. He was probably about 40 years old. It might have been with these

inherited funds that he bolstered his military armoury.

Richard must

have married at about this time, perhaps in about 1400. We don’t know the name

of his wife, as she is not mentioned in his will and might have died before he

did. Mysteriously Richard bequeathed a substantial sum of 40s and his bed to a

lady called Joan Brantyng in his will in 1435. It

might be possible that Joan was his wife and later remarried. Perhaps this was

a more recent acquaintance after his wife had died. We can read whatever we like into Richard’s

relationship with the mysterious Joan Branting.

Richard had

three daughters, Margorie

perhaps born in about 1409, Agnes

born in about 1411 and Alice

born in about 1413. They would each witness the Wars of the

Roses from the heart of the Neville lands.

Scene 2 – Fighting under the

Lancastrians

Regime

Change

The

relationship between Henry Bolingbroke and Richard II came to a crisis in 1398.

A remark about Richard's rule by Thomas

de Mowbray, 1st Duke of Norfolk, was interpreted as treason by John of

Gaunt’s son, Henry Bolingbroke, who reported it to the king. The two dukes

agreed to undergo a duel of honour at Gosford Green near Caludon

Castle, Mowbray's home in Coventry. However before the duel could take place,

Richard II decided to banish Henry from the kingdom to avoid further bloodshed.

It was claimed that this was with the approval of Henry's father, John of

Gaunt. It is not known where he spent his exile. Mowbray was also exiled for life,

and died soon afterwards in Venice.

In William

Shakespeare play of Richard II, Act 1, Scene 3, Henry Bolingbroke mourned his

sentence of exile. How long a time lies in one little word! Four lagging

winters and four wanton springs end in a word. Such is the breath of kings.

The breath

of Kings would now rock the lands of England, and particularly the ancestral

Neville lands, and the lives of the Farndale family, for generations.

Richard II’s

rule was increasingly arbitrary and unpopular. In Shakespeare’s depiction, as

the Lancastrian John of Gaunt lay dying in 1399, he mourned where Richard had

taken his Kingdom.

|

The Lancastrian Patriarch’s

lament for this sceptred isle. |

Methinks I am a prophet new inspired

and thus expiring do foretell of him. His rash fierce blaze of riot cannot

last, for violent fires soon burn out themselves. Small showers last long, but

sudden storms are short. He tires betimes that spurs too fast betimes with

eager feeding food doth choke the feeder. Light vanity, insatiate cormorant, consuming

means, soon preys upon itself.

This royal throne of kings, this sceptred

isle, this earth of majesty, this seat of Mars, this other Eden, demi-paradise,

this fortress built by Nature for herself against infection and the hand of

war, this happy breed of men, this little world, this precious stone set in the

silver sea, which serves it in the office of a wall or as a moat defensive to a

house, against the envy of less happier lands, this blessèd

plot, this earth, this realm, this England. This nurse, this teeming womb of

royal kings, feared by their breed and famous by their birth, renownèd for their deeds as far from home for Christian

service and true chivalry as is the sepulcher in

stubborn Jewry of the world’s ransom, blessèd Mary’s

son. This land of such dear souls, this dear dear

land, dear for her reputation through the world, Is now leased out, I die

pronouncing it, like to a tenement or pelting farm.

England, bound in with the triumphant

sea, whose rocky shore beats back the envious siege of wat’ry

Neptune, is now bound in with shame, with inky blots and rotten parchment

bonds. That England that was wont to conquer others hath made a shameful

conquest of itself. Ah, would the scandal vanish with my life, how happy then

were my ensuing death!

(Richard II,

William Shakespeare, Act 2, Scene 1)

The tension

came to a head when Richard II was campaigning in Ireland, perhaps with Richard Farndale in

his army. His banished cousin, son of the recently dead John of Gaunt, Henry

Bolingbroke, Duke of Lancaster, landed with a small force at the Spurn

peninsula, then the since eroded Ravenspurn, at the

mouth of the Humber in 1399. He marched to his Pickering

Castle, rallying supporters including the Nevilles from Sheriff Hutton and

Kirkbymoorside. He claimed that this was ostensibly to reclaim his lands and

uphold the rules of succession. Richard II was soon captured and taken to

Pontefract castle. This was within the geographical ambit of the Farndales of Doncaster,

who had their home there at this time. He was crowned Henry IV, to start a new

dynasty of the House of Lancaster.

Henry

Bolingbroke’s return from exile and his seizure of the Crown in 1399 was a bold

power grab, an invasion from France in a struggle for the Crown, unseen since

the invasion of William the Conqueror in another succession struggle between

Normans and Godwinsons.

As the

events of 1066, the coup of 1399 was also played out across the same lands that

had been associated with the Farndales for generations. In Shakespeare’s

version of the story, Richard II was left to tell sad stories of the death of

Kings.

|

The

son of the Fair Maid of Kent, proprietor of the Farndale lands, laments that

the King after all is the same as his subjects. |

Of

comfort no man speak. Let’s talk of graves, of worms, and epitaphs, make dust

our paper, and with rainy eyes, write sorrow on the bosom of the earth. Let’s

choose executors and talk of wills. And yet not so, for what can we bequeath save

our deposèd bodies to the ground? Our lands, our

lives, and all are Bolingbroke’s, and nothing can we call our own but death and

that small model of the barren earth which serves as paste and cover to our

bones.

For God’s

sake, let us sit upon the ground and tell sad stories of the death of kings. How

some have been deposed, some slain in war, some haunted by the ghosts they have

deposed, some poisoned by their wives, some sleeping killed, all murdered.

For

within the hollow crown that rounds the mortal temples of a king keeps Death

his court, and there the antic sits, scoffing his state and grinning at his

pomp, allowing him a breath, a little scene, to monarchize, be feared, and kill

with looks, infusing him with self and vain conceit, as if this flesh which

walls about our life were brass impregnable; and humored

thus, comes at the last and with a little pin bores through his castle wall,

and farewell, king!

Cover

your heads, and mock not flesh and blood with solemn reverence. Throw away

respect, tradition, form, and ceremonious duty. For you have but mistook me all

this while. I live with bread like you, feel want, taste grief, need friends.

Subjected thus, how can you say to me I am a king?

(Richard II,

William Shakespeare, Act 3, Scene 2)

Shakespeare

depicted the scene of Edmund Duke of York handing the Crown to Henry. Great

Duke of Lancaster, I come to thee, from plume-plucked Richard, who with willing

soul adopts thee heir, and his high sceptre yields to

the possession of thy royal hand. Richard II had given up the Plantagenet

Dynasty. With mine own tears I wash away my balm. With mine own hands I give

away my crown.

This assault

on the stability of the rules of succession which protected the nation from

chaos, was a concern to the elite classes. Henry Bolingbroke’s seizure of the

throne was precarious from the start. Uneasy lies the head that wears a

Crown (Henry IV, Part II). However Richard had become too problematic as

King, and by then was controlling the nation as a tyrant. The nobility

therefore reluctantly supported Henry. The main support for Henry came from the

great northern family, the Percys.

The Percys

and the Nevilles, the elite families

of the lands of our Farndale ancestors, were rivals and key players in the

nation’s story of the fifteenth century.

The Epiphany

Rising in late 1399 was an attempt to seize Henry IV during a tournament,

kill him, and restore Richard II to the throne, but it failed. The rebellion

convinced Henry IV of the threat posed by Richard while deposed and imprisoned

but still alive. Richard would come to his death by means unknown in

Pontefract Castle by 17 February 1400.

In order to

cement support for his new dynasty, Henry IV was forced to make concessions,

and hint at and end to the heavy taxation which was a strong element of Richard

II’s unpopularity, and that he would uphold property rights and respect the

peoples’ will. He delivered his claim to the throne in London in English, to be

understood by all. His claim had to be rooted in public support because his

claim under the traditional rules of succession was so tentative. That would

prove a millstone for Henry IV, as a modern political party bound by its

manifesto promises.

As Henry

IV’s reign became increasingly threatened, particularly by the challenges of Owen Glyndwr and Gwilym

ap Tudur in Wales and by the Earl of Douglas

in Scotland, his rule was not easy, but his strength of character was

sufficient to find a route to somehow keep things together and his iconic

heroic son Henry V was then able to bind the nation together after his

successes in France.

The

depiction of the young Prince Hal enjoying the taverns of London with Falstaff,

while Harry Hotspur of the Percy family gallantly protected the nation from

their foes provided an amusing side plot for Shakespeare, who suggested he

envied Percy’s Harry over his own Plantagenet Harry.

Yea,

there thou makest me sad and makest

me sin in envy that my Lord Northumberland should be the father to so blest a

son, a son who is the theme of honour's tongue; amongst a grove, the very

straightest plant who is sweet Fortune's minion and her pride, whilst I, by

looking on the praise of him, see riot and dishonour stain the brow of my young

Harry. O that it could be proved that some night-tripping fairy had exchanged in

cradle-clothes our children where they lay, and call'd

mine Percy, his Plantagenet! Then would I have his Harry, and he mine.

(Henry IV

Part 1, Act 1, Scene 1)

It was not

historic reality however, not least because the future Henry V was still a

young teenager and would soon be active in the Wars in Wales, whilst Henry

Percy (1364 to 1403) was in his thirties, a contemporary of Henry IV, not his

son, and would soon turn against the Lancastrian dynasty.

Nevertheless,

at this point Harry Hotspur was the heroic knight. In their Rest

is History Podcast, Tom Holland and Dominic Sandbrook jest that He’d

love rugby. He’d love going to rugby, and cheering on England at Murrayfield.

He’s a brilliant fighter against the Scots, and it’s actually the Scots who

were the first to call him hotspur.

The

Lancastrian dynasty had thus begun and the Percys and Nevilles had supported

its rise. The Farndales were soon dragged in to the fortunes of the new

dynasty. The winds from the breath of Kings were felt by our ancestors

as they tried to find their own paths.

Henry IV’s

military focus was in his struggles against the freedom fighters of Wales led

by Owen Glyndwr, and the flurries into England from Scotland, particularly as

the English armies came under threat from both Wales and Scotland. Wales had

been subject to an apartheid of the native Welsh since draconian laws by Edward

I, and this was a point when that cauldron bubbled over. Owen Glyndwyr claimed to be the Prince of Wales in direct

challenge to Prince Hal’s title.

Another

flurry into Scotland under the new dynasty of Henry IV

There was a Richard Farendon who was archer and man at arms in a Scottish

Expeditionary Force who appeared in Retinue Lists on 24 June

1400. This was almost certainly a record of Richard Farndale’s next

military exploit, perhaps freshly armed with funds from his father’s will. By

this time he would have been in his early forties. It seems likely that he

became an experienced soldier who may have joined a series of campaigns. The

Nevilles were key players in national affairs, so it seems likely that he would

have been encouraged from his Sheriff Hutton home to

join national armies when called to do so.

The English

invasion of Scotland of August 1400 was the first military campaign undertaken

by Henry IV of England after deposing his cousin Richard II. Henry IV urgently

wanted to defend the Anglo-Scottish border, and to overcome his predecessor's

legacy of failed military campaigns.

Although

Henry had announced his plans as soon as the November 1399 parliament, he did

not attempt a winter campaign, but continued with negotiations though became

increasingly frustrated by the Scottish response. Parliament was not keen on

the forthcoming war, and, since extravagance had been a major complaint against

Henry's predecessor, Henry was probably constrained in requesting a tax

subsidy. The general feeling was that a French invasion might be a more

imminent threat.

In June

1400, the King summoned his Duchy of Lancaster retainers to muster at York, and they in turn brought their

personal feudal retinues. At this point, with the invasion being obvious to

all, the Scots attempted to re-open negotiations. Although Scottish ambassadors

arrived at York to meet the king around 26 June, they returned to Scotland

within two weeks.

Although the

army was summoned to assemble at York on 24 June 1400, it

did not approach Scotland until mid August. This was

due to the gradual arrival of army supplies. There were supply delays. The

King's own tents, for example, were not dispatched from Westminster until mid July. Henry must have realised how these logistical

delays would impact on his campaign. At some point before the army left for

Scotland, the muster was met by the Constable of England, Henry Percy, Earl of

Northumberland, and the Earl Marshal, Ralph Neville, Earl of Westmorland. Individual

leaders of each retinue present were then paid a lump sum to later distribute

in wages to their troops. Men-at-arms received one shilling a day, archers half

that, but captains and leaders do not appear to have been paid at a higher

rate.

Richard Farendale of Shyrefhoton came

from Sheriff Hutton in the lands of Ralph Neville, so

there is strong evidence that this was the same person as Richard Farendon who joined these Scottish Wars.

The army

left York on 25 July 1400 and reached Newcastle-upon-Tyne four days later. It

continued to suffer shortages of supplies, particularly food, of which more had

had to be requested before even leaving York. As the campaign progressed, bad

weather exacerbated the problem of food shortages.

It has been

estimated that Henry's army was around 13,000 men, of which 800 men-at-arms and

2,000 archers came directly from the Royal Household. This was one of the

largest raised in late medieval England. Whilst it was smaller than the

massive army assembled in 1345 at the Battle of Crécy, it was larger than most

that were mustered for service in France. The English fleet also patrolled the

east coast of Scotland in order to besiege Scottish trade and to resupply the

army when required. At least three convoys were sent from London and the

Humber, the first of which delivered 100 tonnes of flour and ten tonnes of sea

salt to Henry's army in Scotland.

Henry

crossed the border in mid August. He took care to

prevent his army from ravaging the countryside on their march through

Berwickshire and Lothian in contrast to previous campaigns when for instance

Richard II had devastation wreacked in the

campaign of 1385. This may well have been because the lands they marched

through belonged to the Earl of Dunbar, who had joined the army.

Even so, the

King probably envisaged some confrontation or such a chevauchée

that the Scots would be eager to negotiate. In the event, they offered no

resistance as the English army marched through Haddington.

However,

Henry's army never progressed further than Leith. Not only was no pitched

battle attempted, but the king did not try and besiege Scotland's capital,

Edinburgh nor its castle where the Duke of Rothsay was ensconced. Henry's army

left at the end of the summer after only a brief stay, mostly camped near

Leith, near Edinburgh, where it could maintain contact with its supply fleet.

Henry took a personal interest in his convoys, at one point even verbally

instructing that two Scottish fishermen fishing in the Firth of Forth were to

be paid £2 for their unspecified assistance.

The campaign

ultimately accomplished little except to deplete the king's coffers, and is

historically notable only for being the last one led by an English king on

Scottish soil.

By 29 August

1400, the English army had returned south of the border.

Although the

1400 campaign ended the Wars directly into Scotland, the Scottish Wars

continued with encounters south of the Border. Shakespeare’s play Henry IV Part

1 opens with word brought to the King in about 1402, a few years into the new

Lancastrian dynasty of the Wars with Wales and Scotland.

The Battle

of Homildon Hill was a battle between English and

Scottish armies on 14 September 1402 in Northumberland. A picture of that

battle was painted by Shakespeare. Here is a dear, a true-industrious

friend, Sir Walter Blunt, new lighted from his horse, stained with the

variation of each soil Betwixt that Holmedon and this

seat of ours, and he hath brought us smooth and welcome news. The Earl of

Douglas is discomfited; ten thousand bold Scots, two-and-twenty knights, balked

in their own blood, did Sir Walter see on Holmedon’s

plains. Of prisoners Hotspur took Mordake, Earl of Fife and eldest son to

beaten Douglas, and the Earl of Atholl, Of Murray,

Angus, and Menteith. And is not this an honorable

spoil? A gallant prize? Ha, cousin, is it not?

We don’t

know whether Richard

Farndale was still part of the army at this stage, but it seems likely that

that he continued to fight in these campaigns and we get a Shakespearean

flavour of these campaigns.

Jamie

Farndale, descendant of the medieval soldiers of the English armies of Henry IV

and Henry V, fighting for the Scots six hundred years later

A later

Shakespearean legend painted the death of Harry Hotspur in 1403, at the hands

of the young Prince Hal, future Henry V after the Percy rebellion against Henry

IV. He was wrongly portrayed as the same age as his rival, Prince Hal, by whom

he was slain in single combat. O Harry, thou hast robb’d

me of my youth! I better broke the loss of brittle life than these proud titles

thou hast won of me. They wound my thoughts worse than sword my flesh.

Scene 3 – Fighting with Henry V

Richard

the veteran soldier in the armies of Henry V, the soldier King

Henry V was

crowned in 1413.

Richard Farndale

appears in the military records again in 1417, after the Agincourt campaign, but

it is possible that, as a veteran soldier, Richard might also have fought in

Henry V’s Agincourt campaign of 1415. By this time he was in his late fifties.

I haven’t

yet found him in the list

of known soldiers at Agincourt. In a Roll

of the men at arms at Agincourt, there is no Richard Farndale

listed. But to these lists of named individuals were unnamed lists of lancers

and archers, so he could have been amongst these ordinary unlisted soldiers.

Living firmly within the Neville

lands, it seems likely that he would have fought in the King’s battles with

France. The family also originated from the lands of Joan of Kent, wife of the

Black Prince and the lands of the

Stutevilles and the Mowbrays.

It is

possible that he participated in the main Agincourt campaign, as archer or man

at arms. It is also possible though that, as an old veteran, he was recruited

after the Agincourt campaign, when reinforcements were required from the older

ranks.

After the

Norman Conquest, the Dukes of Normandy, subjects of the King of France were

also King of England. That was tricky. The Dukes of Normandy were frequently in

dispute with their neighbours, including the Dukes of Brittany. By the

thirteenth century, the French noble lines were eager to drive out the English

from their Norman lands. During King John’s reign, the English lost their

Norman lands, and from the reign of Henry III, there was a desire to win back

the Norman lands. Edward III died in 1377 having failed to do so, his son the

Black Prince having died in 1376, leaving Richard II as King, to be overthrown

by Henry IV of the Lancastrian line, whose reign was marred by campaigns in

Wales and Scotland.

When Henry V

became King in 1413, his ambitions were to restore English interests in France,

which would in turn unite the warring factions at home.

In 1415, the

29 year old Henry V launched his invasion of Normandy. He landed in Normandy,

reinforcing his ambitions to restore the lands which the English believed to be

theirs. He landed with an army of 12,000 men.

A quarter of

those were men at arms, who wore heavy armour and had a horse. Men at arms were

paid 1s to 2s a day, depending on their status.

Three

quarters of the force were archers, paid only 6d a day. They were cheaper and

acted as a force multiplier. They were armed with the longbow. They could fire

at rapid rates, from 12 to even 20 arrows a minute, accurately over long

distances.

Richard Farndale might have been an archer or a man

at arms within that army, but we can’t be sure. He was certainly at Harfleur

two years after its siege.

Henry’s army

initially besieged the town of Harfleur, which is modern day Le Havre, at the

mouth of the Seine, the launch site of previous Viking raids on Paris. There

was a long siege at Harfleur, and Henry V directed the siege himself, using

artillery effectively against the walls. The inhabitants of Harfleur eventually

surrendered.

It was at

the Gates of Harfleur that Shakespeare depicted Henry V’s rally.

|

Henry

V inspires his army. |

Once more

unto the breach, dear friends, once more, or close the wall up with our English

dead! In peace there’s nothing so becomes a man as modest stillness and

humility, but when the blast of war blows in our ears, then imitate the action

of the tiger, stiffen the sinews, summon up the blood, disguise fair nature

with hard-favored rage, then lend the eye a terrible

aspect, let it pry through the portage of the head, like the brass cannon, let

the brow o’erwhelm it as fearfully as doth a gallèd rock o’erhang and jutty

his confounded base, swilled with the wild and wasteful ocean.

Now set

the teeth, and stretch the nostril wide, hold hard the breath, and bend up

every spirit to his full height. On, on, you noblest English, whose blood is fet from fathers of war-proof, fathers that, like so many

Alexanders, have in these parts from morn till even fought, and sheathed their

swords for lack of argument. Dishonor not your

mothers. Now attest that those whom you called fathers did beget you. Be copy

now to men of grosser blood and teach them how to war.

And you,

good yeomen, whose limbs were made in

England, show us here the mettle of your pasture. Let us swear that you are

worth your breeding, which I doubt not, for there is none of you so mean and

base that hath not noble luster in your eyes.

I see you

stand like greyhounds in the slips, straining upon the start. The game’s afoot.

Follow your spirit, and upon this charge cry “God for Harry, England, and Saint

George!”

(Henry V, Shakespeare, Act 3, Scene

1)

Might Richard Farndale have been witness to such a speech?

The siege of

Harfleur ended in September as the campaigning season was coming to an end.

However Henry V decided to march home through Normandy via Calais, perhaps to

demonstrate his new hold on Normandy. He challenged the rather pacific Dauphin

to single combat, which was declined. Henry left perhaps 1,200 men to garrison

Harfleur and had lost perhaps 2,000, so he had perhaps 8,000 left.

The French

army blocked the English advance on the Somme, but the English crossed. Having

already portended the D Day invasion of 1944, the Agincourt campaign next found

itself in the battlefields

of 1916.

The armies

eventually met around 45 miles south of Calais, at Agincourt

on 25 October 1415. Henry placed his bowmen in a V shape on either flank. The

longbowmen were a known threat to the French. A tradition evolved after the

battle that the French threatened to cut off the middle two fingers of any

bowmen captured to stop them firing again, and the archers responded to the

French with the defiant V sign.

Did Richard Farndale

flick the V sign to the French that day?

Shakespeare

imagined Henry V’s next stirring speech before Agincourt.

|

Henry

V’s rally at Agincourt. |

We would

not die in that man’s company that fears his fellowship to die with us. This

day is called the feast of Crispian. He that outlives this day and comes safe

home will stand o’ tiptoe when this day is named and rouse him at the name of

Crispian. He that shall see this day, and live old age, will yearly on the

vigil feast his neighbors and say “Tomorrow is Saint

Crispian.” Then will he strip his sleeve and show his scars. Old men forget;

yet all shall be forgot, but he’ll remember with advantages what feats he did

that day. Then shall our names, familiar in his mouth as household words, Harry

the King, Bedford and Exeter, Warwick and Talbot, Salisbury and Gloucester, be

in their flowing cups freshly remembered. This story shall the good man teach

his son, and Crispin Crispian shall ne’er go by, from this day to the ending of

the world, but we in it shall be remembered.

We few,

we happy few, we band of brothers, for he today that sheds his blood with me shall

be my brother; be he ne’er so vile, this day shall gentle his condition; and

gentlemen in England now abed shall think themselves accursed they were not

here, and hold their manhoods cheap whiles any speaks

that fought with us upon Saint Crispin’s day.

Could Richard Farndale have been amongst the happy few, the

band of brothers? If he was not, he must have known those who were, and later

joined them on the fields of France.

The French

planned to overcome the archers with their cavalry, but Henry ordered his

archers to take the initiative and to advance until they were in range and then

fire into the French horses and soldiers, depriving them of the opportunity.

The French

lost perhaps 10,000 whilst the English were said to have lost only 100 to 200.

Amongst the dead was Richard Duke of York, father of Richard of York who would

become to nemesis of the Lancastrians, but at this stage the Yorkists were

loyal to the King.

After the

victory, Henry marched to Calais and besieged the city until it fell soon

afterwards, and the king returned in triumph to England in November and

received a hero's welcome.

Henry V

paraded like a Roman Emperor. The brewing nationalistic sentiment among the

English people was so great that contemporary writers described first hand how Henry was welcomed with triumphal pageantry

into London upon his return. These accounts also describe how Henry was greeted

by elaborate displays and with choirs following his passage to St Paul's

Cathedral.

Support for

the King mean that Parliament eagerly voted new taxes to fund further campaigns

against the French. Agincourt also fomented support for the new Lancastrian

dynasty.

The

victorious conclusion of Agincourt, from the English viewpoint, was only the

first step in the campaign to recover the French possessions that Henry felt

belonged to the English crown. Agincourt also presented an opportunity that

Henry's pretensions to the French throne might be realised. Henry V returned to

France in 1417 to establish his reconquest of Normandy. In this second

campaign, Richard

Farndale was firmly back in the records.

It is tempting

to think that Richard

might have participated in the wider campaign from 1415 to 1421. If he was

indeed a semi professional soldier, this seems

likely. On the other hand, he may have joined the post Agincourt campaign in

1417. It might be that after the losses sustained during the 1415 campaign,

older veteran soldiers were called upon to fill gaps in the ranks, which might

make sense of Richard forming part of the post Agincourt garrison at Harfleur.

What we do

know is that Richard

Farndale was part of Henry V’s army by 1417.

Richard Farndale was

descended from the

poachers of Pickering Forest only a hundred years previously. It was such

men who certainly inspired the stories

of Robin Hood and whose archery skills would foresee the bowmen of ordinary

folk who would one day fight at Agincourt. Richard’s own father had partaken in

a poaching expedition to take fish, deer, hares, partridges and pheasants from

Pickering Forest in 1367, for which Thomas Mowbray’s father, John Mowbray had

brought him to justice.

Outlawry and

military heroism were not so far apart.

|

c 1357 to 20

December 1435

A veteran soldier

of the armies of Richard II, Henry IV and Henry V who fought in the French

and Scottish Wars |

Richard

might have been about 58 years old by this stage, so if he was part of a

medieval army, he would have been an old soldier. However if it was he who had

fought in France in 1380 and in Scotland in 1400, it is likely that this old

soldier had become a campaign warrior. His impressive armoury which he left at

his death in 1435 suggests an old campaigner who had risen to possess the

armoury of a man at arms. He seems to have alternated between or perhaps progressed

from being an archer to a man at arms.

The

principal consolidated source for participation in the Agincourt campaign is

the University of Southampton databases on the

English Army in 1415 in their data on the Soldier in Medieval England.

Amongst the candidates

for Farndale ancestors amongst medieval armies, there was a Richard Farndon

who was an archer mustered in the Garrison at Harfleur under Thomas Beaufort,

Earl of Dorset and Duke of Exeter in 1417. After the

Siege of Harfleur from 17 August to 22 September 1415, the town would have

been garrisoned in the following years. It was at the gates of Harfleur that

Henry V had delivered his inspiring speech in 1415.

The 1417

record of Richard Farndon at Harfleur suggests that Richard Farndale was

an old veteran fighting in those campaigns, either part

of the 1415 Agincourt campaign and continuing in the wars that followed, or

joining the English force after Agincourt in their subsequent campaign up to

1421.

The victory

at Agincourt inspired and boosted English morale, while it caused a heavy blow

to the French as it further aided the English in their conquest of Normandy and

much of northern France by 1419. The French, especially the nobility, who by

this stage were weakened and exhausted by the disaster, began quarrelling and

fighting among themselves. This quarrelling also led to a division in the

French aristocracy and caused a rift in the French royal family.

By 1420, a

treaty was signed between Henry V and Charles VI of France, known as the

Treaty of Troyes, which acknowledged Henry as regent and heir to the French

throne and also married Henry to Charles's daughter Catherine de Valois.

In 1421,

Richard Farendon or Farndon appeared again in the list of medieval

soldiers, as part of a Standing Force in France as a foot soldier or Man at

arms and as an archer, under Richard Woodville the elder (1385 to 1441) and

Richard Baurchamp, Earl of Warwick.

1421 was the

year of the Battle

of Bauge, the defeat of the Duke of Clarence and his English army by the

Scots and French army of the Dauphin of France. The battle took place on 22

March 1421. The Duke of Clarence, King Henry V’s younger brother commanded the

English army. The Earl of Buchan commanded the Franco-Scottish army. The

English army numbered around 4,000 men, of whom only around 2,500 men took part

in the battle. The Franco-Scottish army comprised 5,000 to 6,000 men.

Richard

Woodville or Wydeville, later the First Lord Rivers

and father of Elizabeth Woodville later wife of the Yorkist Edward IV, under

whom Richard Farendon served, was granted various

domains, lordships and bailiwicks in Normandy in 1419 and 1420, culminating in

1421 with appointment as Seneschal of the province of Normandy.

Richard

Beauchamp, 13th Earl of Warwick held high command at sieges of French towns

between 1420 and 1422, at the sieges of Melun in 1420, and of Mantes, to the

west of Paris, in 1421-22. The more significant siege was of Meux to the east

of Paris.

In 1420 the

town of Melun in France surrendered to King Henry V. The siege had rumbled on

since June and had been fairly dramatic at times, with close combat taking

place literally beneath the walls as the besiegers and the garrison dug mines

and countermines in an attempt to bring the siege to an end. James I of

Scotland (1397 to 1437, crowned 1424) was present at the siege, brought to

France in 1420 as Henry's trump card against the Scots serving on the

Continent.

Siege of

Melun from a late 14th century manuscript

The siege of

Meaux was fought from October 1421 to May 1422. Paris was threatened by French

forces, based at Dreux, Meaux, and Joigny. The king

besieged and captured Dreux quite easily, and then went south, capturing Vendôme and Beaugency before

marching on Orléans. Henry then marched on Meaux with an army of more than

20,000 men. The town's defence was led by the Bastard of Vaurus,

by all accounts cruel and evil, but a brave commander. The siege began on 6

October 1421. Mining and bombardment soon brought down the walls.

The English

also began to fall sick rather early into the siege, and it is estimated that

one sixteenth of the besiegers died from dysentery and smallpox while thousands

died thanks to the courageous defence of the men at arms inside the city. As

the siege continued, Henry himself grew sick, although he refused to leave

until the siege was finished.

News reached

Henry from England that on 6 December 1421, Queen Catherine had borne him a son

and heir at Windsor.

On 9 May

1422, the town of Meaux surrendered, although the garrison held out. Under

continued bombardment, the garrison also surrendered on 10 May 1411, following

a siege of seven months. The Bastard of Vaurus was

decapitated, as was a trumpeter named Orace, who had once mocked Henry. John

Fortescue was then installed as English captain of Meaux Castle.

It seems

likely that Richard

Farndale took part in some or all of these siege campaigns around Paris in

1421.

Richard Farndale of Sheriff Hutton appears

to have been an old soldier who campaigned with Henry V, and perhaps built up

his small wealth on campaign.

Henry V died

in 1422 and left a nine month old baby son, Henry VI. The inter noble rivalry

would soon pick up again.

Scene IV – The Wars of the Roses

The Wars

of the Roses loom

Henry VI had

no father to guide him to Kingship and he relied on his advisors. He became

timid and passive. At this point in history, the nobility needed strong

leadership to control their ambitions. After the expensive battles in France,

financial resources were depleted. The young king was easily controlled by the

rival noble families.

This

unpopularity would ferment displeasure with the Lancastrian dynasty, which

under Henry V had been so popular, and would stir up a Yorkist uprising.

In time the

Yorkist cause came to be supported by the Nevilles of Sheriff Hutton. Cecily

Neville married Richard, Duke of York, the main protagonist of the Yorkist

cause. Their son, Edward IV would found the Yorkist royal dynasty in 1461.

Richard Neville, Earl of Warwick, the Kingmaker, was the main political

strategist to the Yorkist cause, in the early stages of the Wars of the

Roses.

|

The History of Sheriff Hutton to 1500

A

history of Sheriff Hutton which will take you to the lands of the Nevilles

and Richard III during the Wars of the Roses |

|

The Church of St Helen and the Holy Cross and the

Chapel of St Nicholas, the heart of the Neville lands, and place of the

alabaster effigy of the young son of Richard III |

|

This

history of the family who influenced the Wars of the Roses in whose seat our

ancestors lived |

Richard Farndale was about 65 by this time, too old

perhaps to take an active role himself. However he lived in Sheriff Hutton, at the

heart of the cauldron that started to bubble amongst the Yorkists. As a proud

old soldier of Henry V he was likely to have been appalled at the failures of

Henry VI, stirred on no doubt by his landlords, the Nevilles. In the last dozen

years of his life, we can imagine Richard over dinner

with his daughters spitting with rage at where things had got to under Henry

VI, and yearning for the new glamour of the Yorkist cause. In an old chest in

his bedroom perhaps, his armour of bascinet, breastplate and arm and leg

fittings must have lain. His grey horse rested in the stables. He probably

would have put them on and rode out with the Nevilles if he had been asked to

do so.

However at

this stage Henry VI was just a young King, not yet a hopeless adult one and the

Wars of the Roses did not kick off until 1455, twenty years after Richard Farndale’s

death. He would leave his three daughters to live through the years of Yorkist

and Lancastrian rivalry. We only know their names. Perhaps they were passive

witnesses to the events which would follow. Perhaps their husbands and their

sons engaged in those Wars. We don’t know.

Richard’s

armour was bequeathed to the church, to pay for his funeral. Perhaps when the

civil war kicked off, they were taken by some other man at arms who likely

fought with the Yorkists, under the Neville banner.

Richard Farndale

died in 1435, exhausted from his life of adventure and chevauchée.

His will was proved at Sherifhoton on 21

December 1435.

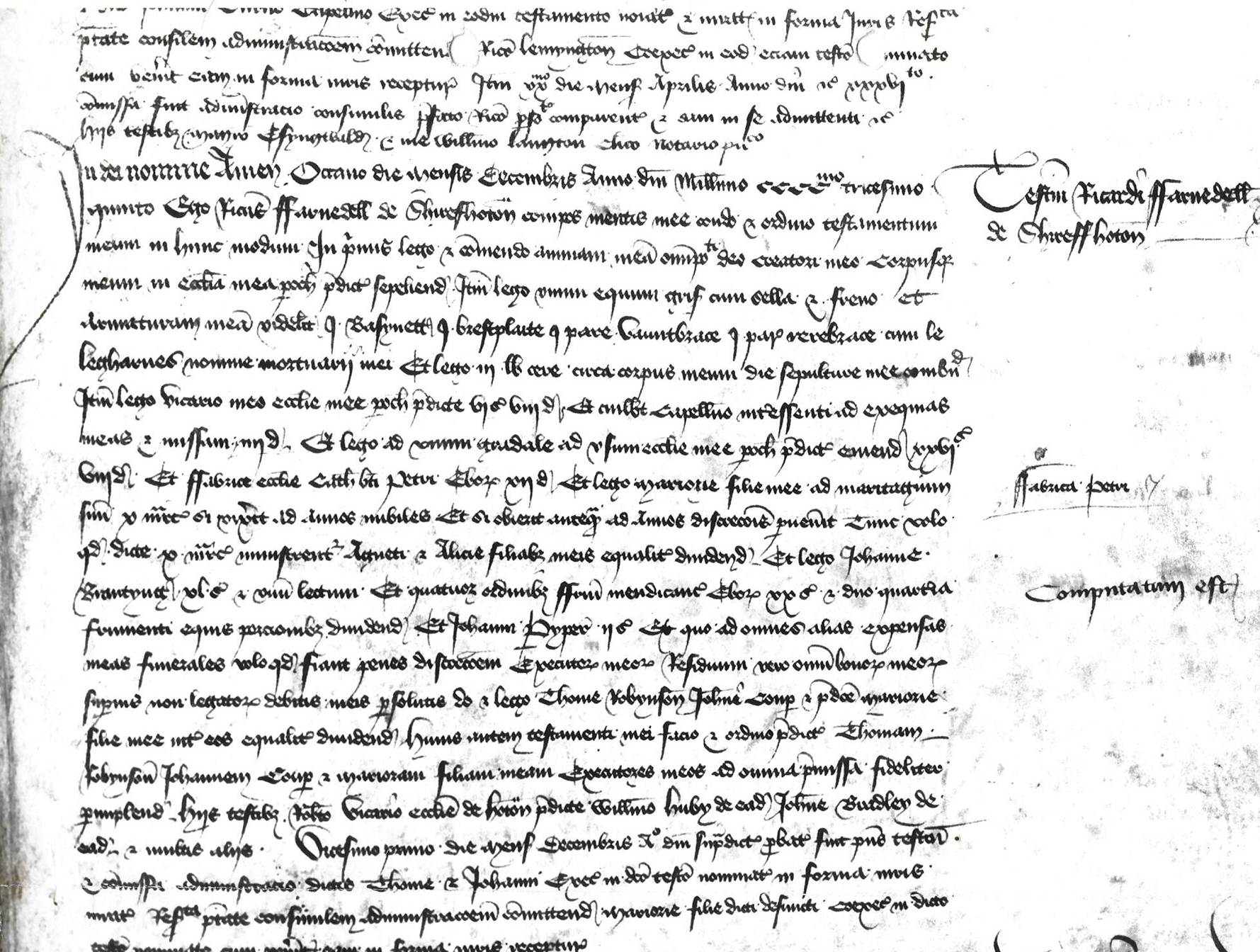

In the

name of God Amen, 8th December 1435. I Richard Farndell being of sound mind

make my will in this manner. Firstly, I bequeath and Commend my soul to God

Almighty, My Creator, and my body to be buried in my said Parish Church.

Item. I

bequeath a grey horse with saddle and reins and my armour, viz: a bascinet, a

breast plate, a pair of vembraces and a pair of rerebraces with leg harness as my mortuary payment. And I

bequeath 3 lbs of wax to be burned around my body on the day of my burial.

Item. I

bequeath to the Vicar of my Parish Church 6s 8d and to every chaplain taking

part in my burial service Mass, 4d.

And I

bequeath 26s 8d for mending a service book for the use of the parish church.

And to

the fabric of the Cathedral Church of St Peter York, 12d.

And I

bequeath to my daughter Margorie at her marriage 10 marks, if she live to be

marriageable age. And if she die before she arrives at her years of discretion,

I wish the said 10 marks to be divided equally between my daughters Agnes and

Alice.

And I

bequeath to Joan Brantyng 40s and a bed.

And to

the four orders of friars mendicant of York 20s and two quarters of corn to be

divided in equal portions.

And to

John Pyper 2s.

And as

regards the rest of my funeral expenses, I wish them to be paid at the

discretion of my executors.

The rest

of my goods, not bequeathed above, my debts having been paid, I bequeath to the

said Margorie, my daughter, to be divided among them in equal parts.

And I

make the said Thomas Robynson and John Couper and

Margorie my daughter, my executors, faithfully to implement the terms of my

will.

Witnesses;

Robert, Vicar of the Church of Hoton, William Huby of

the same, John Burdley of the same and many others.’

Administration

granted to Thomas and John on 21st December 1435 with rights reserved for

similar administration to be granted to Margorie.

(Translated

from Latin text of Will held at York).

Richard

Farndale therefore died between 8 and 21 December 1435.

The History of Sheriff Hutton

picks up the story of the Wars of the Roses, seen through the prism of the town

of the Sheriff Hutton line

of the Farndale family

When Duke of

Gloucester, Richard later Richard III, alleged murderer of his nephew princes

in the tower of London, married Lady Anne Neville of Middleham and Sheriff Hutton, they

had a son, Edward Prince of Wales who died aged only 11 in 1484 in Middleham

and his tomb effigy lies in the church of Sheriff Hutton.

Richard’s Council of the North held court in Sheriff Hutton. Richard

Farndale’s daughters lived within the events of the Wars of the Roses in the

lands of the Nevilles and Richard III.

|

How do the medieval warrior Farndales relate

to the modern family? It is not possible to be accurate about the early family tree,

before the recording of births, marriages and deaths in parish records, but

we do have a lot of medieval material including important clues on

relationships between individuals. The matrix of the family before about 1550

is the most probable structure based on the available evidence. If it is accurate, Richard Farndale

was related to the thirteenth century ancestors of the modern Farndale

family, and was part of

the Sheriff Hutton Line.

He was related to the original family who lived in the dale and then left for

new lands. He was possibly a second cousin of the Doncastrian

Farndales, from whom the modern family probably descends. John, Henry and William Farndale

were part of the York Line of

Farndales. Their father, Johannis

de Farndell, was probably the brother of William and Nicholas

Farndale of Doncaster, from whom the modern family probably descend. All these soldiers were kin of the modern family. |

or

Go Straight to Act 11 – The

Vicar of Doncaster

Or

Read the History of Sheriff

Hutton

Get to

know the medieval soldiers John, Henry and

William Farndale and Richard Farndale

Explore the genealogy

behind the Wars of the Roses

Meet House Neville

Explore Sheriff Hutton and its

church