Act 11

The Vicar of Doncaster

The story of the Family of William

Farndale, the Fourteenth Century Vicar of Doncaster

Having left

Farndale and crossed the Vale of York to York and Sheriff Hutton, our family

next found themselves in medieval Doncaster. For two centuries the direct

ancestors of the modern family seem to have lived there, shifting their centre

of gravity a little north into Barnsdale Forest and Campsall, a place with deep

historical links to the legend of Robin Hood

|

This

is a new experiment. Using Google’s Notebook LM, listen to an AI powered

podcast summarising this page. This should only be treated as an

introduction, and the AI generation sometimes gets the nuance a bit wrong.

However it does provide an introduction to the themes of this page, which are

dealt with in more depth below. |

|

Scene 1 – The Vicar of Doncaster

Medieval

Doncaster

Modern

Doncaster is strongly characterised by its industrial past. However the Doncaster to which we now turn

our attention was a very different place. It was the place of the significant

Roman Fort of Danum. After the Norman Conquest, Nigel Fossard had built

a Norman Castle. By the thirteenth century, Doncaster was a busy town. In 1194

Richard I had given the town recognition by bestowing a town charter. There was

a disastrous fire in 1204 from which the town slowly recovered.

In 1248, a

charter was granted for Doncaster Market to be held in the area surrounding the

Church of St Mary Magdalene, which had been built in Norman times. But over

time the parish church was transferred to the church of the old Norman castle,

the castle which by then was in ruin. The new parish church was the original

Castle Church of St George.

During the

14th century, large numbers of friars arrived in Doncaster who contrasted to

the settled monks by their itinerant lifestyles. In 1307 the Franciscan friars

(Greyfriars) arrived, as did Carmelites (Whitefriars) in the mid-14th century.

|

The History of Doncaster to 1500 The

History of pre industrial Doncaster from its Roman inception as Danum

to the end of the sixteenth century |

|

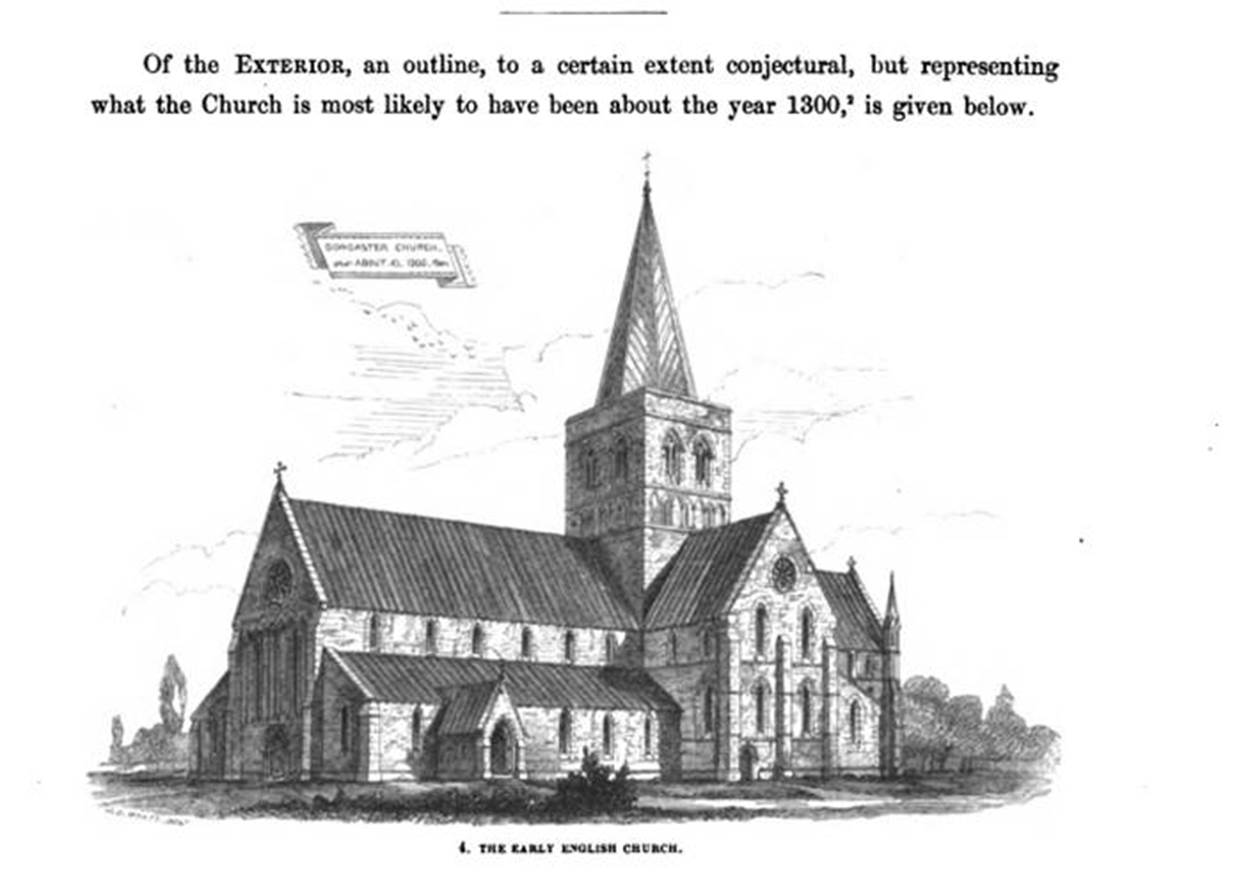

Medieval Doncaster and its minster

The Victorian Parish church, later Minster, of

Doncaster rebuilt in 1853, but on the site of the earlier Parish church of

which William Farndale was chaplain and later vicar in the years after the

Black Death |

William

Farndale

It is in

this setting that we meet William Farndale.

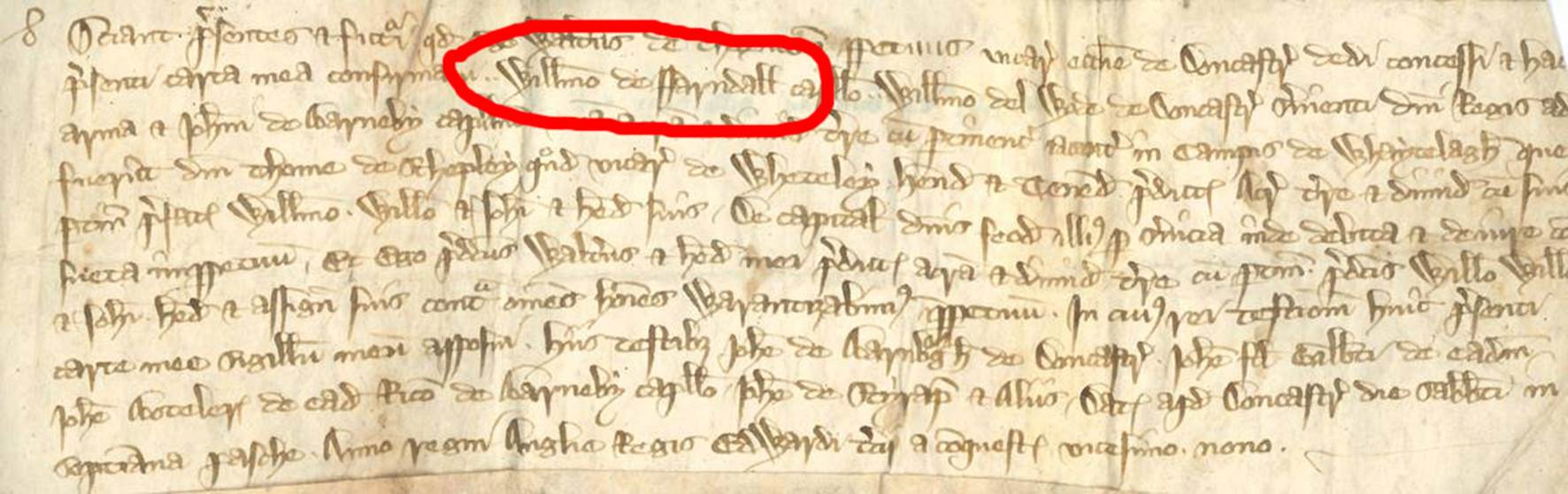

We first see his name in a grant of land in Latin by Walter de Thornton, the

vicar of Doncaster, and William de Farndell, his chaplain on 11 April 1355.

Perhaps William may

have been about twenty then, so perhaps he was born in about 1335. The Black Death had ravaged Doncaster

from about 1349, and its population had been reduced to about 1,500. So William must

have survived the Black Death. Perhaps it was his survival of those horrors

that was his path to the church.

We then spot

William of

Doncaster again in the patent rolls

of 7 December 1368, when Robert Ripers transferred

five acres of land at Loversall, just

south of Doncaster, to Sir William Farndale, still a chaplain. The term sire

was used as an address to religious men such as priests. It doesn’t denote a

knight.

|

The

history of a small village and church just south of Doncaster, where William

Farndale held land |

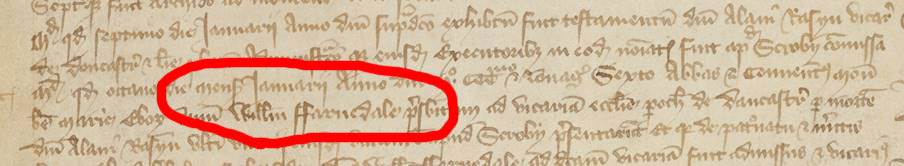

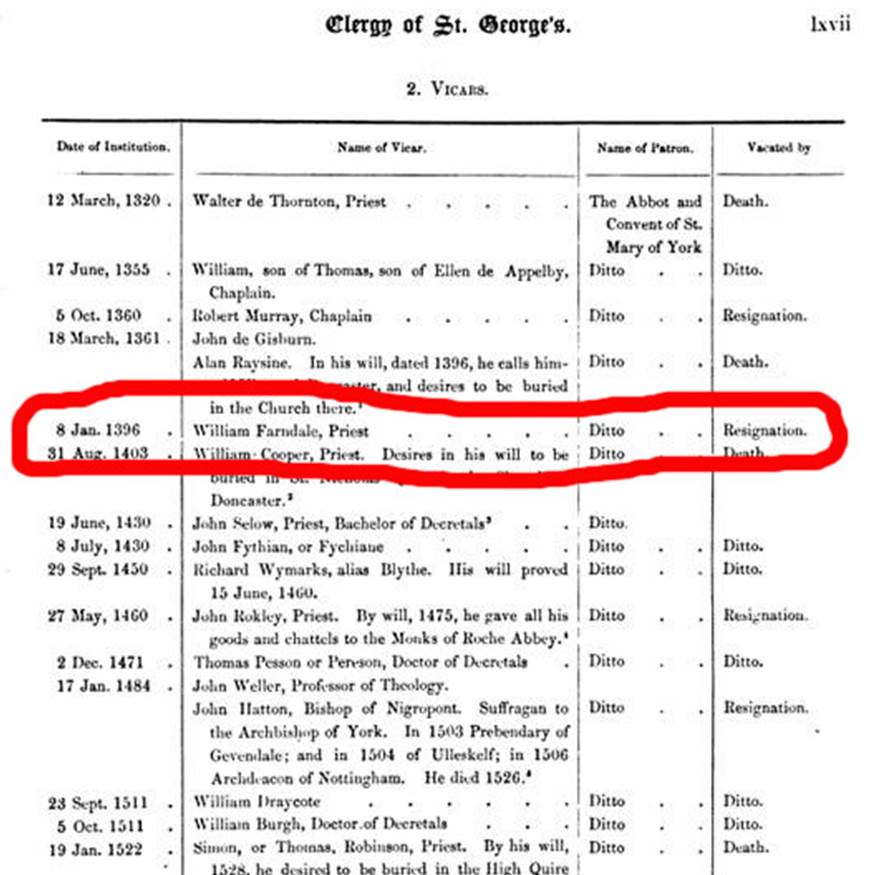

William then

became the Vicar of Doncaster from 8 January 1397, aged about 61, to 31 August

1403, aged about 68, when he resigned.

So William was

the vicar of the early Church of St George’s at the end of the fourteenth

century. Whilst not yet of the stature of the impressive Doncaster Minster of

St George’s, which was rebuilt on the site after a fire destroyed the early

church in 1853 and which was given Minster status in 2004, it was even by then

an impressive church.

William

transferred his land at Loversall to John Burton in 1402. “‘Know men present

and to come that I, William Farndalle, Vicar of the

Church of Doncastre, have given, granted and by this

present charter confirmed to John Burton of Waddeworth,

his heirs and assigns 5 acres of land with appurtenances lying in the fields of

Loversall. Viz, those 5 acres of land which I had as gift and feoffment of

Robert Ryppes of Loversalle

and which extend from the meadows of the Wyke to the Kardyke

as the charter drawn up for me by Robert Ryppes more

fully sets out. To have and to hold the said 5 acres of land with appurtenances

to the said John Burton, his heirs and assigns from the chief of the lords of

the fee by the services thence owed and customary by right. And I William Farndalle and my heirs will warrant the said 5 acres of

land with appurtenances to the said John Burton, his heirs and assigns against

all men for ever. In witness whereof I have affixed my seal to this present

charter. These being witnesses; John Yorke of Loversalle,

Robert Oxenford of Loversalle, William Ryppes of the same, John Millotte

of the same, William Clerk of the same and many others. Given at Loversalle 6 April 3 Henry IV. (6 April 1402).”

In 1403 we

see the installation of William Couper as the vicar of Doncaster, on William Farndale’s

resignation.

|

C1330 to c1415 The Chaplain and

Vicar of Doncaster, who held lands at Loversall, of whom we have significant

records |

Scene 2 – The Vicar’s Brother

Peasants

Revolt

At about

this time, Nicolaus

de ffarndale, whose wife was Alicia, paid 4d in

the second of three impositions of a poll tax in 1379 at Doncaster.

|

1332 To 1400 Nicholas paid the

4d Poll Tax of 1379 which led to the Peasant’s Revolt |

It was these

three poll taxes imposed in the early reign of Richard II, the son of Joan the

Fair Maid of Kent of Stuteville

descent, and the Black Prince, that led to the Peasants Revolt in Kent and

Brentford in 1381. In reality this was the revolt of a new middle class

disgruntled at barriers to their aspirations. It seems likely that Nicolaus

was William’s

brother.

Shortly after meeting the protestors in London, by 22 June

1381 Richard II was showing no sympathy for the rebels. You wretches detestable on

land and sea, you who seek equality with lords are unworthy to live. Give this

message to your colleagues: rustics you were, and

rustics you are still; you will remain in bondage, not as before, but

incomparably harsher. For as long as we live we will strive to

suppress you, and your misery will be an example in the eyes of posterity.

However, we will spare your lives if you remain faithful and loyal. Choose now

which course you want to follow.

The

emergence of the Robin Hood legends

at about this time was likely to have been inspired in part at the general

grievances of the new aspiring middle class which led to the peasant’s revolt.

The Farndales were after all descendants of the poachers of

Pickering Forest. They may not have taken kindly to being told, rustics

you were, and rustics you are still.

The record

in Doncaster then goes

silent until 1564, and there is more research to be done in Doncaster local

records.

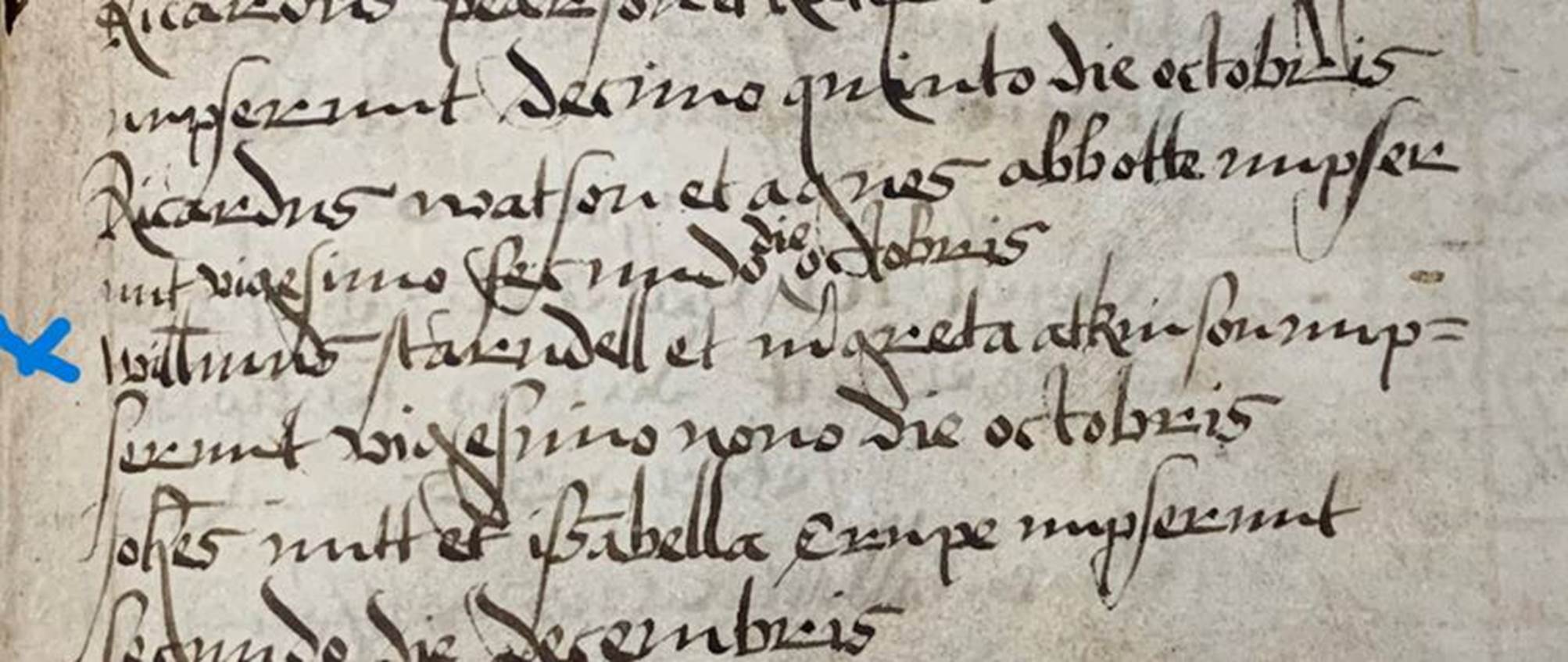

Scene 3 – Barnsdale Forest

Campsall

Our radar

warms up again on 29 October 1564 when a wedding took place between a William Farndell and a Margaret Atkinson

in the Church of St Magdalene in the village of Campsall, which

is only a few miles north of Doncaster.

It seems

very likely that William

Farndell who married in 1564 just north of Doncaster

came from the same line of Farndales as William Farndale,

the vicar of Doncaster two hundred years earlier. There must have been a

generation or two between them. It seems quite likely that William the Younger

was descended from William the

Elder’s brother, Nicholaus de ffarnedale.

So it seems

reasonable to suppose that there was a family of modern Farndales’ ancestors

living around Doncaster

back to William

the Vicar’s time, whose centre of gravity moved a little north of Doncaster to Campsall or its

environs by the sixteenth century.

We see the

names William and Nicholas continue to be used by the main family line from the

sixteenth century. William was a well used name, but

the continuity with the environs of Doncaster and the continued use of the

names Nicholas and William adds to the evidence that it was from this Doncastrian family that modern Farndales descend.

Campsall is

a town which was then dominated to the west by the inaccessible and waterlogged

marches of the Humber levels and to the west, by Barnsdale Forest, an area

closely associated with the legend of Robin

Hood.

|

The

history of the village of Campsall north of Doncaster, where we find our

ancestors in the sixteenth century |

|

St Mary Magdalene Church,

Campsall

The church in Barnsdale forest of which the literary

character of the Middle Ages, Robin Hood, wrote I made a chapel in

Bernysdale, That seemly is to se, It is of Mary Magdaleyne, And therto would I

be. Nearby sites associated with Robin Hood including

Robin Hood’s Well at the side of the A1 |

By the fifteenth century the villagers

at Campsall north of Doncaster, had formed a fraternity, and hired

their own priest to pray for the parishioners living and the souls departed.

Over time the Church dedicated to St Mary

Magdalene at Campsall came to resemble a collegiate church. Alongside the

vicar and deacon were also chantry priests in the vicinity who sang masses for

the repose of the souls of individuals who left endowments to the church. The

chantry priests were extras to the parish clergy and may have

been involved in teaching. It has been suggested that the first

floor chamber above the vaulted west bay of the south aisle at St Mary

Magdalene, dating from the late thirteenth century, might have been a space

used for such a purpose.

The

emergence of the theologian Richard of Campsall (c1280 to c1350) suggests

a well established tradition of teaching in Campsall. Richard of

Campsall, or Ricardus de Campsalle, was a

secular theologian and scholastic philosopher at the University of Oxford.

Richard of Campsall’s surviving works include his Quaestiones

super librum Priorum analeticorum, “Questions about the book Prior

Analytic”, the Contra ponentes naturam,

“Against Nature”, on universals, a short treatise on form and matter, Utrum materia possit esse sine forma,

“whether matter can exist without form”, and Notabilia de contingencia et presciencia Det,

“Remarks on contingency and presceience”, all

probably written about in about 1317 or 1318. In the Questions on the

Prior Analytics Richard of Campsall proposed that training in logic

was the basis for all other sciences. He discussed the concepts of syllogism,

consequences, and conversion. He argued that the crux of logical thinking was

the syllogism and knowledge of consequences and conversion was necessary for

the study of syllogism, especially for converting imperfect syllogisms

into perfect syllogisms. In supposition theory, Campsall proposed views

usually first attributed to Ockham, including his distinction between simple

and other types of supposition.

This

was deep stuff. Campsall must have been the crucible of some serious

intellectual debate to have produced a person such as Richard.

Most

English writers of the fifteenth century had at least some association with the

Church. Those who captured the rymes of Robehod into the written word were therefore

likely to have had some ecclesiastical background.

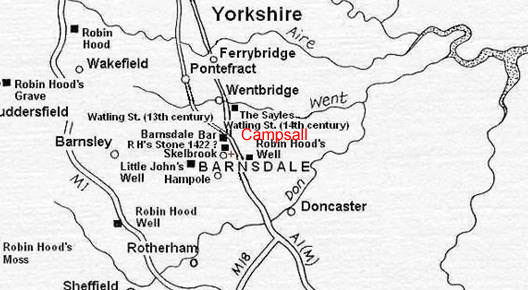

The

earliest references to Robin Hood are more associated with Barnsdale Forest than

Sherwood. Many of the names given to geographical locations in Sherwood Forest

were given in the nineteenth century. Some names though are much older, such as

Barnsdale’s Stone of Robin Hood, about 500m north of Robin Hood’s Well, which

was mentioned as a boundary marker in about 1540

by John Leland, in his Itinery in or about the years 1535-1543.

This is

where we remind ourselves of our more distant ancestors who were outlaws in Pickering

Forest, reminiscent at least of the

Robin Hood stories. Robin Hood is largely a creature of ballads composed

from the fourteenth century at the time of William Farndale,

the vicar. A map showing the geographical locations associated with Robin

Hood reveals that Campsall is in its

heart. Campsall was a centre of teaching

from the thirteenth century and quite likely to have been associated with the

recording of traditional stories.

The famous

fifteenth century ballad A Gest of Robyn Hode suggests that Robin Hood

built a chapel in Barnsdale that he dedicated to Mary Magdalene. I made a

chapel in Bernysdale, That seemly is to se, It is of

Mary Magdaleyne, And thereto wolde

I be. Given the location of the Church of St Mary Magdalene at Campsall,

this church has long been associated with the church of Robin Hood repute, and

it was here in 1564, that William Farndell married Margaret Atkinson.

|

The

legend of Robin Hood explored for its Yorkshire roots, and the Farndale

connection with the legends, first as the class of poachers who gave rise to

the inspiration, and later their fifteenth century descendants who lived in

the place where the stories emerged |

So the

Farndale family found itself at the place associated with the fourteenth

century ballads which told of the

exploits of Robin Hood, which must have been strongly influenced by the

tales such as those of our own Farndale ancestors, who outmanoeuvred the

sheriffs of Yorkshire in the forest of Pickering. There have been many

suggestions that the legend of Robin Hood may have its real roots in Yorkshire.

Our family

story finds associations both with those who must have inspired the Robin Hood

stories, and those who started to tell those stories from the fourteenth

century.

|

How do William Farndale, Nicholaus de ffarnedale and his wife Alicia relate to the modern

family? It is not possible to be accurate about the early family tree, before the recording

of births, marriages and deaths in parish records, but we do have a lot of

medieval material including important clues on relationships between

individuals. The matrix of the family before about 1550 is the most probable

structure based on the available evidence. If it is accurate, the Doncastrian

Farndales were related to the thirteenth century ancestors of the modern

Farndale family, and might have been related to the York Line. Nicholaus’

own family settled in Doncaster, with his brother William Farndale the Vicar of Doncaster, and

he and his wife Alicia might be on the direct ancestral line of the modern Farndales. |

or

Go Straight to Act 12 – Arrival

in Cleveland