The History of Doncaster to 1500

The History of pre

industrial Doncaster from its Roman inception as Danum to the end

of the sixteenth century

The

Crossing Place on the Don

The Deanery

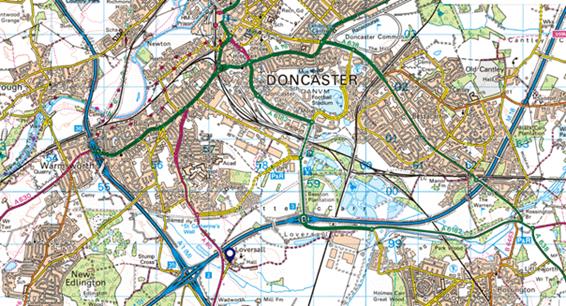

of Doncaster is one of three historic divisions of the old West Riding of

Yorkshire. This is an area rich in coal and iron. Modern Doncaster is strongly

characterised by its industrial past. In the fourteenth century, though

Doncaster was a very different place.

It was the

place of a significant Roman Fort. After the Norman Conquest, Nigel Fossard had

built a Norman Castle. By the thirteenth century, Doncaster was a busy town. In

1194 Richard I had given the town recognition by bestowing a town charter.

There was a disastrous fire in 1204 (fires seem to feature heavily in

Doncaster’s history) from which the town slowly recovered.

In 1248, a

charter was granted for Doncaster Market to be held in the area surrounding the

Church of St Mary Magdalene, which had been built in Norman times. In time the

parish church was transferred to the church of the old Norman castle, the

castle which by then was in ruin. The new parish church was the original Church

of St George. During the fourteenth century, large numbers of friars arrived in

Doncaster who were known for their religious enthusiasm and preaching. In 1307

the Franciscan friars (Greyfriars) arrived, as did Carmelites (Whitefriars) in

the mid fourteenth century. Other major medieval features included the Hospital

of St Nicholas and the leper colony of the Hospital of St James, a moot hall, a

grammar school and a five-arched stone town bridge with a chapel dedicated to

Our Lady of the Bridge.

Doncaster

1857

Doncaster’s

origins are rooted in the need for a crossing of the Don at this place. The

sixteenth century historian, John Leland, wrote I marked that the North parte of Dancaster tonne standith as an isle: for Dun river

at the West side of the towne castith

oute an arme, and sone

after at the Este side of the town cummith into the

principal streame of Dun again. The fluvial islands

probably attracted early settlement and the islands might have been the home of

the ferry man. The island and the relatively low banks might have been the best

place for a road to cross in time.

The Don was

the approximate southern boundary of the Celtic Brigantes,

dividing them from the Coritani to the south. At the

crossing place of the Don where Doncaster now stands, the Brigantes

may have had a small settlement.

Danum

From 43 CE,

Roman influence had transformed the culture of people in southern and eastern

Britain. The emperor Claudius commanded a force of some 40,000 men, even

supported by elephants. They were grouped into four legions supported by

auxiliaries.

The Romans built an alliance with the Brigantes’ Queen, Cartimandua, and established a

defensive line along the line of the Don. The Romans built a series of advanced

forts at Derby, Templeborough and Castleford. The

rectangular fort at Templeborough stood on the south

bank of the Don, about twelve miles southwest of the site of modern Doncaster,

where Rotherham now stands. 800 soldiers of the 4th Cohort of Gauls were stationed there.

When

Cartimandua had a relationship with her armour Bearer, Vellocatus,

Cartimandua’s husband, Venutius began a civil war

against her in 57 CE but Cartimandua was protected by

the Roman Ninth Legion. In 69 CE, during a period of instability under Emperor

Nero, Venutius attacked again and Cartimandua fled

leaving Venutius in control of the region and in

conflict with Rome.

At Templeborough the timber fort was replaced with a new

sandstone fort.

In 71 CE the

newly appointed Roman Governor, Petillius Ceralius marched north to occupy Brigantes

and Parisii territory. The Ninth Legion marched north

from Lincoln into the new northern territories and erected a large camp near

where Malton, northeast of York, stands today. A significant military camp was

founded by the Romans as Eboracum

(modern day York) in 71 CE.

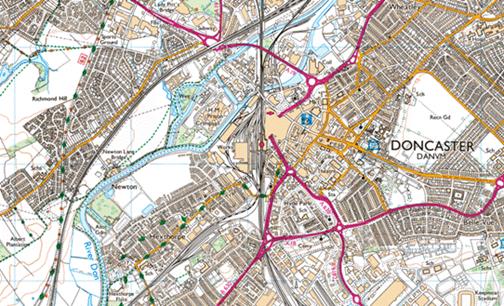

The passage

over the Don at the Doncaster site would require protection. This was also the

site of the limit of inland navigation for coastal vessels. The place of the

modern St George’s Minster was favourable for a Roman castrum. The

establishment of a castrum and a company of soldiers was an inducement

to settlers.

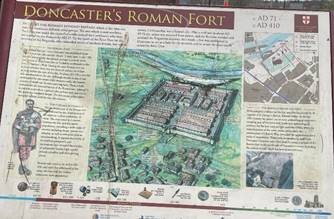

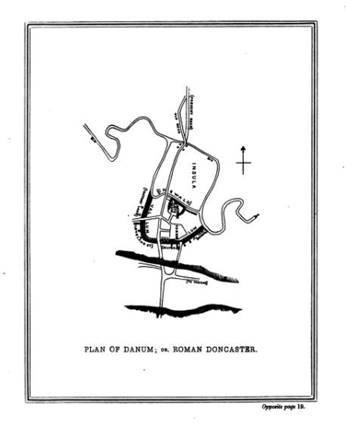

A fort at Danum,

on the site of modern Doncaster, was established soon after 70 CE and occupied

a large footprint of some nine and a half acres, with timber buildings and a

cobbled road. This original fort was abandoned at the time of the building of

Hadrian’s Wall in 122 CE and rebuilt on a smaller scale from 160 CE, then

stretching to about six acres protected by an 8 foot thick

stone wall.

Danum fell at the southern edge of the

Roman province of Maxima Caersariensis, "The Caesarian province of Maximus", also known as

Britannia Maxima.

Strictly Danum

was the Roman name for the river and the Roman’s referred to the place itself

as Castrum ad Danum. To the south side of the river at Roman Danum

emerged new building works, based on the favoured plan of two streets

intersecting at right angles. The two streets divided the town into four

quarters, together with the island in the Don. In one quarter was the castrum

and its praetorium (headquarters) and in another quarter there would

have been a market. There were two gates, the Sepulchre Gate and Baxter Gate.

Excavations in 1976 revealed that the civilian settlement was of considerable

scale.

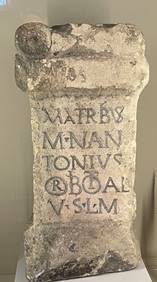

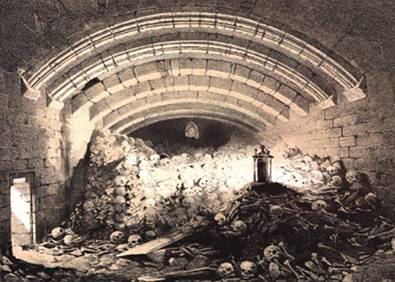

Remains

of the Roman castrum in the grounds of the modern minster

The

Doncaster altar, which can be seen today at the Doncaster library, was found at

the Sepulchre Gate and was inscribed To the Mother Goddess. Nonnius Antonius has freely and deservedly fulfilled his

vow. There have also been finds of a coin hoard and pottery and glass.

Danum was built at the place where

Icknield, or Ricknield, Street, which ran from

Bourton to Eboracum, crossed the Don. The Romans adapted much of this road from

an ancient route. The main road from Lincoln approached

Danum from the south with a minor crossing at Rossington Bridge, just

south of Doncaster, in the approximate area of Loversall.

There is considerable evidence of Iron Age and Roman field systems in this

area. The road then continued to cross the Don at Danum. From Danum

the road then continued joining the line of the modern A1 and passing near to Campsall,

through the forest of Barnsdale.

Four miles south of Doncaster and in the vicinity of the fort

at Rossington Bridge, the rich farm lands encouraged wealthy Roman Britons to

build their villa at Stancil, which was later the place of a medieval village. A wide range of

vessels have been found in this area which evidence trade as far north as

lowland Scotland.

In Roman

Doncaster, the present market-place was in all

probability used then for the same purpose that it is now. It would also

contain, as most Roman market-places did, the public

Temple.

The Roman

fort was regarrisoned and was occupied until at least 390 CE, towards the end

of the Roman period. There seem to have been town defences by the end of the

Roman era.

Anglo

Saxon Doncaster

By the sixth

century CE, the River Don was the boundary between Deirans,

and later the Northumbrians, and the Mercians to the south. The old Roman roads

continued in use, but settlements tended to develop in more secluded places,

some distance away from the roads.

When

Augustine came to Britain, he does not appear to have attempted to bring his

mission to Northumbria. However Edwin King of

Northumbria (586 to 633 CE) married the daughter of Ethelbert, the converted

King of Kent and it was agreed that she should freely exercise her religion.

She was accompanied by a zealous pupil of Augustine, Paulinus, and this

provided the basis for Edwin’s conversion. Edwin of Northumbria was baptised in York about 15

years after the death of Augustine. From that time, Paulinus was increasingly

employed in conversion across the region of Northumbria.

Bede

described that Paulinus instructed crowds in Bernicia and in Deira during his

conversion missions. He often followed river courses and baptised along the

river Swale, where it flows beside the town of Catterick and

also in Cambodonum, where there was also a royal

dwelling. At Cambodonum he built a church which

was afterwards burnt down, together with the whole of the buildings, by the

heathen who slew Edwin (this was when Penda defeated Edwin at Hatfield in

633 CE). In its place later kings built a dwelling for themselves in the

region known as Loidis. This altar escaped from the

fire because it was of stone, and is still preserved

in the monastery of the most reverend abbot and priest Thrythwulf,

which is in the forest of Elmet.

Loidis is modern Leeds. Cambodonum

has been interpreted as various locations in the West Riding, but it probably

derives from “Field of the Don” and is more likely a reference to Doncaster.

So, it is

likely that a church was erected in the place of modern Doncaster at this time.

If this is correct, then Paulinus also tells us that Edwin had a royal

residence (villa regia) at Campodonum.

The praetorium of the Roman castrum might have been an ideal site

for an occasional royal residence. Bede’s record also suggests that the church

at Doncaster was burnt down by Penda after the Battle of Hatfield Chase in 633

CE.

Bede’s

record also suggests that a second Christian church, after the church at York in 627 CE, was built in Doncaster

under Paulinus’ supervision.

In 633 CE,

Edwin was killed by the pagan Penda of Mercia and Cadwallon from North Wales at

the heath field on Hatfield Chase, ten kilometres northeast of Doncaster. It

appears that Penda immediately attacked Doncaster and destroyed the church, and

probably the royal residence, as we don’t hear of Northumbrian kings returning.

However the altar was preserved in a monastery in the

wood at Elmet, around modern Leeds. There is a debate as to whether the site of

the battle was in fact in Nottinghamshire where a mass grave was found, but the

marshy land of Hatfield Chas is still generally regarded as the site of the

battle.

After the

battle whilst King Oswald revived Christian Northumbria two years later, this

part of the Kingdom was ruled over by the Mercians until Penda was killed in

654 CE when it reverted to Northumbrian rule.

Celtic

Christianity was much weaker in South Yorkshire, so it did not fall so clearly

into the debate that led to the Synod

of Whitby between Roman and Celtic traditions.

In 764 CE

the chronicler Symeon of Durham in his Historia Regum

groups referred to a number of places including York,

London and Doncaster, repentino igne vastatae, destroyed by a

sudden fire.

Multae urbes, monsteriaque,

atque villae, per diversa loca necnon

et regna, repentino igne vastatae sunt; verbi gratia, Stirburgwenta civitas, Homunic, Lundonia civitas, Eboraca

civitas, Donacester, aliaque

multa loca illa plaga concepit.

“Many

cities, towns, and villages, in different places, as well as kingdoms, were

destroyed by a sudden fire; for example, the city of Stirburgwent,

Homunich, the city of London, the city of York,

Doncaster, and many other places were conceived by that plague.”

There is

evidence of fire in the area of the Roman castrum,

but these marks may have been the result of the devastation by Penda.

Scandinavian

Doncaster

The

earliest recorded Viking raid in Britain was the attack on Lindisfarne in AD

793. The early Scandinavian raiders generally picked largely undefended,

wealthy targets such remote monasteries. The Norse raiders quickly learned that

ecclesiastical centres provided easy and plump reward.

Alfred of

Beverly recorded the destruction of the monastery at the mouth of the Don,

which may have been a reference to Doncaster. Monasterium

ad ostium Doni amnis precaverunt,

sed non impune, “They

prayed to the monastery at the mouth of the river Don, but not with impunity”.

This was a

time when Alcuin of York, in the Kingdom

of Charlemagne, was despairing of the fate of his homeland.

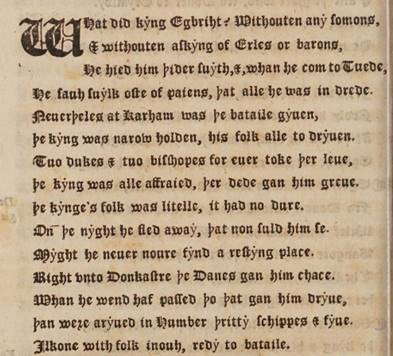

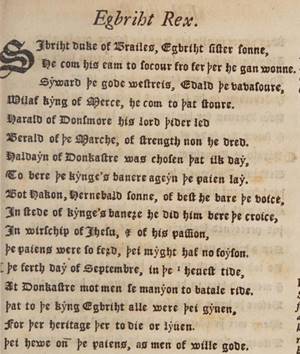

By 833 CE

the Danes were dominating the lands around the Humber estuary. King Ecgbert of Wessex

had some success in resisting the Danes and appears to have had some success in

a battle at Doncaster. The story of this encounter was told in the thirteenth

century in a rhyme by Peter

Langtoft, an Augustine canon and chronicler from the village of Langtoft in

the East Riding of Yorkshire.

What did

king Egbriht? Without any summons. And withouten

asking of Erles or barons … Right unto Doncastre ye Danes gan him chase

… At Donkastre mot men se manyon

to batale ride …

The

substantial Great Heathen Army landed in East Anglia on the east coast of

England in 865 CE, but soon turned northwards.

In 866 CE,

when Northumbria was internally divided, the Danes captured York. The Danes

changed the Old English name for York from Eoforwic

to Jorvik. They destroyed most of the

early monasteries in the region. Some of the minster churches survived the

plundering.

The Late

Anlo-Saxon-Scandinavian Period

In time, the

Danish leaders were themselves converted to Christianity. Jorvik became the

capital of the Anglo-Saxon-Scandinavian lands and it

would reach a population of 10,000. Jorvik became an important economic and

trade centre for the Danes. Jorvik perhaps prospered from its trade with

Scandinavia.

The Danish

suppression of South Yorkshire seems to have been led by Guthrum

from the East Midlands. A number of settlements in the

lower Don valley have Scandinavian names.

Modern

Doncaster is generally identified with Cair

Daun listed as one of thirty three British cities in the Ninth century History

of the Britons traditionally ascribed to Nennius.

It was

certainly an Anglo-Saxon burh, and in the late Anglo

Saxon Scandinavian period, it received its modern name. Don, Old English

Donne, derives from the settlement and river and caster (ceaster) from an Old English version of the Latin castra,

a military camp or fort.

The area of

modern Doncaster was likely not to have been open land, but forested until it

started to be cleared in the late Saxon period. The forests of this area have

been described as the Great Brigantian Forest. At

some stage, perhaps from late Saxon times, areas were cleared for settlement in

the process called assarting. The growth of population and villages, including Campsall and Loversall, by the time of Edward the

Confessor suggest that assarting had been pursued on a significant scale by

that time.

Rev Joseph

Hunter in South Yorkshire, The History and Topography of the Deanery of

Doncaster, 1828, lists 170 vills of human

settlement by the late Saxon period. He suggested that settlements might have

grown at places where there was a need to cross a watercourse, but often may

have been the inclination of a family to settle on land, which later grew into

a larger habitation. This informal process was soon replaced by recognition of

rights of occupancy from the lands of the elite class who owned large estates.

It became no longer open to every citizen to clear woodland for his own use,

but by the Doomsday record, a right had been recognised in overlordship.

The Saxon

lords came to surround themselves with dependents who held portions of land

from him, in return for rendering services. This is reflected in culture.

Particularly in the story of Beowulf,

which provided an encouragement to live within the protection of the elite

class, as protection against the perils of unsettled places.

It was Conisbrough, within the modern city of Doncaster, which

appeared as the dominant estate in Anglo-Saxon and Scandinavian South

Yorkshire. It was mentioned in the 1003 will of Wulfric Spott, a wealthy

Mercian nobleman who founded Burton Abbey. By the Conquest it was owned

directly by King Harold. It was then the centre of a large former royal estate

which reached to Hatfield Chase. Conigsborough was

head of an extensive fee. The Saxon lords of Doncaster, Laughton and Hallam

also had many dependencies. It was also an early ecclesiastical centre.

Dadesley

(now Tickhill) and Doncaster both emerged as burgesses. Other small centres

were emerging including Campsall, which

was valued at £5 in a census of Edward the Confessor, being one of the larger

settlements.

The larger

seats of population came to be governed under the authority of a bors holder who was elected at a general

assembly. Townships were grouped in tens under a hundreder,

a superior officer who held courts. These hundreds came to be called wapentakes

in the areas to the north. Doncaster and Loversall

fell within the Wapentake of Strafford. Campsall fell

within the Wapentake of Osgodcross.

Just before

the Conquest, the area was probably still covered in native forest, but which

was not dense, so that sheep and oxen rove among the trees. Islands of land

were cultivated, varying from 200 to 2,000 acres, where agriculture was

undertaken and sometimes these settlements had mills, and Christian places of

worship. Doncaster and Tickhill, and perhaps Rotherham, had by this time become

small towns.

The lands of

Doncaster were held by Tostig (Tosti), of Godwin descent, who rebelled against

his brother Harold, and died alongside the Dane Harold Hardrada at the Battle

of Stamford Bridge. He was a man of blood, and

perished by the sword at the battle of Stamford Bridge just before the

Conquest.

Norman

Conquest

In 1066 the

Danes, led by the Norwegian King Harold Hardrada, sailed up the Ouse, with

support from Tostig Godwinson and after the Battle of Fulford, when they

defeated Morcar and Edwin, they seized York.

King Harold

of England then marched his army north to York in four days to take the

invaders by surprise. The rebels were defeated at the Battle of Stamford

Bridge, about 60 kilometres northeast of Doncaster, in which Harold Hardrada

and Tostig were killed.

The trouble

of course was that Harold then had to march his exhausted army south again, to

confront the second threat from William of Normandy, near Hastings, and in that

episode, he didn’t do so well.

After the successful Norman invasion of England in 1066,

the north was not immediately subdued under Norman rule. However the harrying of the north meant

that most of England was under the Norman thumb by 1086, which was the date

when the Domesday Book recorded the extent of Norman domination two decades

after the invasion.

As well as recording the comprehensive regime change, the

Domesday Book also evidences the administrative efficiency of the new

overlords. A millennium later, that efficiency provides us with the tools with

which to have eyes on the historical events of our very distant past. The

Domesday Book, written in Latin, recorded every important place in the country

- what was there, who owned it prior to the conquest, and to whom it was

transferred after the Conquest. It established the taxable values of all the boroughs

and manors across the nation. The record was held in two large books, which are

still held by the National Archives and accessible at Domesday Online. The

surveyors visited 13,000 villages over the course of about a year. The whole

landed property of England then totalled a value of £37,000, which puts

subsequent inflationary increases into some perspective.

Thereafter

the area, along with the nation of which it was a part, fell under the Norman Yoke.

By the

Norman Conquest, 28 townships in what is now South Yorkshire belonged to the

Lord of Conisbrough. William the Conqueror gave the

whole lordship of Conigsbrough to William de Warenne. Shortly after the Norman Conquest, Nigel Fossard

refortified the town and built Conisbrough Castle.

Joseph

Hunter tells us that the wider lands of the Deanery of Doncaster were

distributed in very unequal parts to twelve persons, including Nigel Fossard

and William de Warren, William de Perci, Ilbert de Laci and others.

By the time

of Domesday Book, Hexthorpe in the wapentake of Strafforth

was said to have a church and two mills.

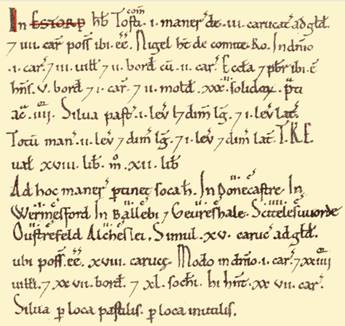

In Estorp, Earl Tosti had one manor of three carucates for

geld and four ploughs may be there. Nigel has [it] of Count Robert. In the

demesne, one plough and three villanes and three

bordars with two ploughs. A church is there, and a priest having five bordars

and one plough and two mills of thirty two shillings

[annual value]. Four acres of meadow. Wood, pasturable, one leuga

and a half in length and one leuga in breadth. The

whole manor, two leugae and a half in length and one leuga and a half in breadth. T.R.E., it was woth eighteen pounds, now twelve pounds. To this manor

belongs this soke – Donecastre (Doncaster) two carucates, in Wermesford (Warmsworth)

one carucate, in Ballebi (Balby) two

carucates, in Geureshale (Loversall) two carucates, Oustrefeld (Austerfield) two carucates and Alcheslei (Auckley) two carucates. Together fifteen

carucates for geld, where eighteen ploughs may be. Now [there is] in the

demesne one plough and twenty four villanes

and thirty seven bordars and forty sokemen. These have twenty

seven ploughs, wood, pasturable in places, in places unprofitable.

These

settlements referred to in the Domesday Book, described the area of modern

Doncaster. The street name Frenchgate suggests that

Fossard invited fellow Normans to trade in the town.

Estorp (Hexthorpe) is a small village now part of Doncaster and at

the time about a mile downstream from the main town. It comprised three caracutes of land. More extensive holdings were

appended to Estorp, which included Doncaster and Loversall and other places. Doncaster

comprised two caracutes which have been

assessed by historians as about 200 acres of arable land; two mills; and forty

soke men, villeins and borderers who cultivated the soil. There was no doubt a

church there. The value of the soke at the time of the Conquest was £18 but only

£12 by the time of the survey, which suggests the devastation of the harrying

of the North. The lands had been held by Tostig before the conquest, but passed

after the Conquest to Robert, the Earl of Mortain,

who was King William’s half brother. An interest in

the lands was also held by Richard the Deaf.

The focus

moved away from Hexthorpe as a centre after the Conquest.

A sokeman

belonged to a class of tenants, found chiefly in the eastern counties,

especially the Danelaw, occupying an intermediate position between the free

tenants and the bond tenants, in that they owned and paid taxes on their land

themselves. Forming between 30% and 50% of the countryside, they could buy and

sell their land, but owed service to their lord's soke, court, or jurisdiction.

The carucate

was a medieval unit of land area approximating the land a plough team of eight

oxen could till in a single annual season.

Tickhill,

ten kilometres south of Doncaster, was referred to as Dadsley

in the Domesday Book. Its ownership passed from Also, son of Karski to Roger

the Bully and it comprised 54 villagers, 12 smallholders, 1 priest, 1 man at

arms and 31 burgesses, with 8 ploughlands, 7 Lord’s plough teams and 26.5 men’s

plough teams. It had two acres of meadow, woodland, 3 mills and a church. It

was valued at £14. Dadsley was an Anglo

Saxon settlement meaning Daedi’s clearing.

The

Feudal Landholders after the Conquest

Robert,

Count of Mortain in Normandy and Earl of Cornwall in

England was handsomely rewarded for his service at Hastings. Robert's

contribution to the success of the invasion was clearly regarded as highly

significant by the Conqueror, who awarded him a large share of the spoils. He

received 797 manors. In 1088, he joined with his brother Odo in revolt against

their nephew William Rufus. William

Rufus returned the Earldom of Kent to Odo but it

wasn’t long before his uncle was plotting to make Rufus’s elder brother, Robert

Curthose, King of England as well as Duke of Normandy. Rufus attacked Tonbridge castle where Odo was

based. When the castle fell Odo fled to

Robert in Pevensey. The plan was that

Robert Curthose’s fleet would arrive there, just as William the Conqueror’s had

done in 1066. Instead, Pevensey fell to

William after a siege that lasted six weeks. William Rufus pardoned his uncle

Robert and reinstated him to his titles and lands. Robert died in Normandy in

1095.

Nigel

Fossard held lands from the Earl of Mortain. He was

one of the principal under-tenants of Count Robert, of whom he held some 91

manors, a substantial portion of the Mortain lands.

Hexthorpe was his chief holding in Yorkshire. It is very likely that on the

forfeiture of Count Robert’s estates, Nigel was made a tenant in capite, that is, he held his lands directly from the

King.

Nigel

Fossard therefore came to possess the lands formerly held by Tostig, including

the feudal superiority of Doncaster. Fossard had a house at Doncaster, but his

principal residence was at Mulgrave Castle. His descendants held Doncaster

until the reign of Henry VI, though not directly through the male line after

William Fossard.

He gave

extensive property to the church. Included in his gifts to the Abbot and

Convent of St Mary, York, was the gift of the church of Doncaster and

neighbourhood. He was succeeded by his son Adam, who founded the priory of

Hode, now Hood

Grange.

Robert

Fossard, who succeeded Adam, paid a fine of 500 marks to the King to repossess

the Lordship of Doncaster, which he had parted to the King to hold in

demesne for twenty years. The reason for the surrender to the King and the

high price for the repossession is not known. It is possible that Robert had

not paid the whole of the fee due to the King when he succeeded to his

patrimonial inheritance, hence the lease and release. It is possible that the

King just needed to raise funds.

William

Fossard succeeded Robert. He was the last of the Fossards

in the male line. He was one of the northern barons who fought against the

Scots in the

Battle of the Standard. In 1142 he was with Stephen’s forces against the

Empress Maude at the

Battle of Lincoln and was taken prisoner. From time to time he paid scuttage, a tax paid in lieu of military service by

those who held land by Knights service, of £12, £21 and a further sum of £31

10s, the last amount was levied upon him because he was not in the Irish Wars.

He was exempted from contributing for the redemption of King Richard I. He left

a daughter, Joan, who was married to Robert de Turnham.

Robert de

Turnham had two sons, Robert and Stephen. It was Robert the Younger who married

Joan Fossard. Robert the Younger was a crusader. He appeared to be with the

King in the Holy Land, and was entrusted to bring the

King’s harness back to England. For the services on that journey

he was discharged from the payment of scuttage

levied for the Kings ransom. Being in the King’s confidence he managed to

obtain from the king a charter confirming to the burgesses of Doncaster

whatever ancient privileges they then possessed. He obtained a grant of two

more days to be added to the fair that had anciently been kept at his manor of

Doncaster in County Ebor, on the eve and day of St James the apostle. At his

death in 1199, the yearly value of the lands held by him in right of Joan, his

wife, was entered at £411 9s 2d.

He left a

daughter, Isabell, who became a ward of the King. She married Peter de Mauley,

a Poictevin.

A long line

of Peter de Mauleys, claiming descent from Nigel Fossard, successively held the

Lordship of Doncaster. The first of these is said to have committed an infamous

crime at the instigation of King John. On the death of King Richard, his

brother John, knowing that he could not succeed him by reason that Arthur,

son of Geoffry of Brittany, was alive, got Arthur into his power and implored

Peter de Mauley, his esquire, to murder him and in reward gave him the heir of

the barony of Mulgref. There are some doubts

about this allegation. If Mauley really did commit the act at the instigation

of John, and was led to expect that he would receive

the King’s ward to marry with the free enjoyment of her lands, he was

disappointed. Peter de Mauley paid a fine of 7000 marks for entrance to the

inheritance of the daughter of Robert de Turnham. He gave the body of his

wife to be buried at the Abbey of Meux, Holderness, endowing the Abbey with a

rent of Sixty shillings per year. He died before 1241. In 1247 the King took

the homage of his heir, Peter, for all his father’s lands. Some six years later

this Peter de Mauley obtained a charter of Free Warren in his demesne lands,

which included Doncaster. He died in 1279.

The next

Peter de Mauley paid £100 relief for all lands held of the King in capite of the inheritance of William Fossard. From a

document from 1279 we catch a glimpse of a part of the Mauley holdings for

which this relief was paid. He married Joan, the daughter of Peter Brus of Skelton.

There

followed another six Peter de Mauleys.

Alongside

the Mauleys, other descendants of Nigel Fossard had interests in Doncaster.

The

landowners enjoyed significant revenues from rents, fines, reliefs,

benevolences, maritages (the fee paid by a vassal following the feudal

lord’s decision on a marriage), wardships and opportunities for escheat

(the reversion of land when owners died without heirs). They were also relieved

of many of the costs of running modern estates, because they were owed duties

of service. The value of these estates is best seen not in monetary terms, but

in the works they were able to undertake. The castles

at Coningsborough and Tickhill were obviously works of significant labour. The

growth of monasteries also reflected the power held by the nobility, including

the costs of building churches.

The

growth of Doncaster

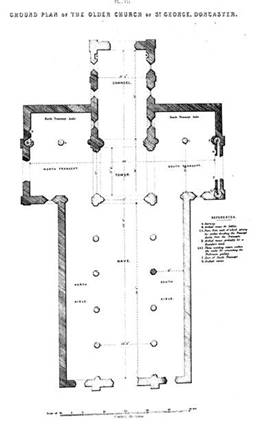

The Roman

fort at Danum was had been replaced by an Anglo Saxon

burh or fortified settlement, before a Norman castle was built at

Doncaster. The Doncaster castle has long disappeared. The motte of the Norman

Castle has been located to be under the east end of St George’s Minster.

There was

significant building of monasteries and parish churches during this period.

The building

of churches was attractive as this enabled the lords to extract tithes from

distant churches to which it had been paid and settle it on churches of their

choosing, perhaps closer to their own residence. During this period churches

were built at places including Coningsborough, Campsall, and

Doncaster. Joseph Hunter lists 60 places where Churches were built.

Most of

these churches had one officiating minister at their foundation, the persona

or rector. The churches were often placed under the patronage of monastic

institutions.

Early in the

reign of William II (William Rufus), in about 1088, Nigel Fossard was amongst

the benefactors who founded the abbey of St Mary in York. Fossard gave the

church of Doncaster to the new abbey as well as lands in the area.

The church

at Doncaster was distinguished from others by being given the title of dean.

Certain of

these churches were parish churches in form, but were also referred to as

chapels, which meant that they were given rights of baptism, nuptial

benediction and of sepulture, but were not able to

participate in tithes from the lands around them. These churches included St

Mary Magdalene at Doncaster and the chapel at Loversall.

At Doncaster

there was a college, for the residence of chantry priests, so that they need

not mingle with the public. This was built near the parish church and the

priests officiated in the parish church and at St Mary Magdalene chapel, living

a collegiate life as it was felt inappropriate for their social character to

mix too freely with the people of the town.

A borough

was created at Doncaster after the soke had been granted directly to

Nigel Fossard on the banishment of William’s half brother

Robert, Count of Mortain.

Doncaster

was ceded to Scotland in the Treaty of Durham and never formally returned to

England. The first treaty of Durham was a peace treaty concluded between kings

Stephen of England and David I of Scotland on 5 February 1136. In January 1136,

during the first months of the reign of Stephen, David I crossed the border and

reached Durham. He took Carlisle, Wark, Alnwick, Norham

and Newcastle-upon-Tyne. On 5 February 1136, Stephen reached Durham with an

imposing troop of Flemish mercenaries, and the Scottish king was obliged to

negotiate. Stephen recovered Wark, Alnwick, Norham

and Newcastle, and let David I retain Carlisle and a great part of Cumberland

and Lancashire, alongside Doncaster.

In February

1136, Henry, prince of Scotland, did homage to Stephen for Doncaster and the

honour of Huntingdon.

Tickhill

acquired markets and fairs long before the system of royal licences started in

the late twelfth century. The town grew rapidly.

The story of

Doncaster is not only told through the history of the noble families. The

burgesses and inhabitants of the town followed the 40 soke men referred to in

Domesday book, and came to enjoy increasing

privileges. The earliest record might be the Pipe Roll of the third regnal year

of Henry II, 1156, when Adam Fitz Swein was

discharged of £60 due for the rent of Doncaster. Adam Fitz Swein

owed £45 of rent for Doncaster and £15 had been paid for a quarter part of the

year. It appears therefore that the burgesses held Doncaster from the King for

a rent of £60 per annum and an individual was appointed to account for it.

In 1157,

Malcolm, King of Scotland, did homage to Henry II for Cumberland, in Doncaster.

In 1163,

Malcolm of Scotland was again in Doncaster to do homage and fell dangerously

ill there.

In 1191,

during Richard I’s absence on crusade, John seized the castles of Tickhill and

Nottingham.

However by

1194 Richard I had given the town recognition by bestowing a town charter. The

charter was the first article of the Miller’s Appendix and declared that the

King had granted to the burgesses of Doncaster the soke and town of Doncaster

to hold by the ancient rent and 25 marks of silver more to be paid into the

exchequer with all liberties and free customs. The burgesses paid 50 marks to

the king for the charter. It seems that the burgesses must have gained

something more tangible from the charter, though it is not clear exactly what.

Amongst the privileges gained was the right to hold a fair and market held at

St James’ Tide.

The

Charter at Doncaster Library

Doncaster

had by this time become the dominant settlement in the region. Its position on

the great road from London to York, and en

route to the Scottish border, made it a place where strangers rested.

The area

around Doncaster appears to have enjoyed relative peace after Norman rule had

been established. Conisbrough Castle never endured a siege and Pontefract

Castle, which was seen as the key of the North, was

not attacked until the English Civil War.

Conisbrough Castle

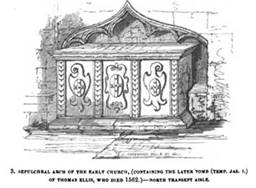

In the time

of the Fossards, Doncaster had consisted of a few

public buildings of stone, amidst a town of wooden houses. The original public

building was the castle which stood at the location of the present Doncaster

Minster. John Leland (1503 to 1552) in his Itinery

later recorded: The Church stands in the very area where ons

the castelle of the towne stoode, long sins clene decayed.

The dikes partely yet be scene, and the foundation of

partte of the waulles.

The Wall of the Castle is mentioned in a grant of 1416.

Beside the

parish church was the church or chapel of St Mary Magdalene, which was founded

before the year of King John. There were hospitals of St James, with a chapel

annexed, and St Nicholas, which had lands at Loversall,

which would have provided some relief to the poor and the aged. There were also

public mills on the Don. This was the town as it must have appeared before the

great fire of 1204.

There was a

chapel of our lady at the bridge.

When John

seized the throne in 1199, he acquired Tickhill and during his reign he spent

over £300 strengthening its defences.

There was a

disastrous fire in 1204 which appears to have completely

destroyed the town, from which the town slowly recovered.

The revival

of the town after the fire is first recorded in a warrant of King John

addressed to the bailiffs of Peter de Mauley, who had married Isabella de

Turnham, the heiress of Doncaster. The bailiff was instructed to enclose the

town along the course of a ditch and to fortify the bridge. This appears in the Close Rolls. It appears therefore

that Doncaster was protected by a ditch and possibly a mound and Leland later

indicates that Doncaster did not become a walled town. Doncaster continued to

comprise mainly wooden buildings at least until the time of Henry VIII. Only

the public buildings were of stone.

By 1215 the

whole town was enclosed by an earthen rampart and ditch, which was filled with

water from the Cheswold, the original course of the

Don. By this time it had four substantial stone gates

as entrances at St Mary’s Bridge, St Sepulchre Gate, Hall Gate and Sun Bar.

In 1248, a

charter was granted for Doncaster Market to be held in the area surrounding the

Church of St Mary Magdalene, which had been built in Norman times.

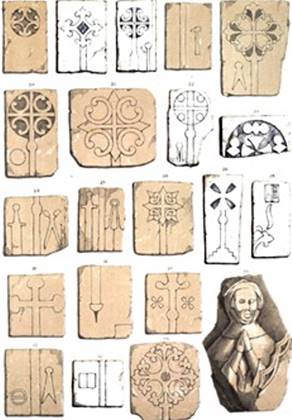

The

burgesses grew their wealth and significance during this period. A principal

class of merchants appeared and the Don was gradually

made navigable. Many merchants’ marks were made on the old parish church and

the richness of its development evidences the

increasing opulence of the merchant class.

Doncaster

became the most prosperous medieval town in South Yorkshire.

Urban

expansion in the early medieval period was accompanied by an increase in the

size of the rural population and colonisation of new lands.

The Survey

of the County of York in 1277 by John de Kirkby known as Kirkby’s

Inquest, (the Nomina Villarum for Yorkshire) was taken in the fifth reign of

Edward I, and it described the ownership of the main settlements of the

Wapentake of Strafford.

Early during

the reign of Edward II from 1282, there was a feud between the Earl of Warren

at Coningsborough and the Earl of Lancaster at Pontefract. The Earl of

Lancaster called his followers together at Doncaster and attacked Tickhill

Castle, but the enterprise came to nothing.

Nomina Villarum (“Names of Towns”) was a survey

carried out in 1316 and included a list of all cities, boroughs and townships

in England and the Lords of them.

In these Inquisitions

Nonarum during the reign of Edward III, eight

merchants were said to be residing in Doncaster, which was more than in other

similar towns. At Tickhill there were seven merchants

so this was an area of commercial significance. There is rare evidence of

summons being sent to Doncaster and Tickhill directing them to send burgesses

to Parliament.

In late 1321

Thomas, Earl of Lancaster, the great baron at Pontefract, opposed royal

authority and called on many barons to meet at Doncaster. On 12 November 1321

the King forbade this meeting on penalty of forfeiture of their lands. An open

rebellion ensued, joined by Lord

Mowbray. On 18 March 1322 the King was in Doncaster and the Battle

of Boroughbridge was fought on 17 March 1322 when the rebels were defeated

and Thomas was executed at Pontefract

In 1334 the

inhabitants of Doncaster contributed £17 in taxes, compared with £12 10s 0d in

Tickhill and £7 3s 4d from Sheffield. Doncaster owed its wealth mainly to its

weekly markets and its annual fairs, which had become nationally famous. There

was a huge market place in the south east corner of

the medieval town, and as was common, it was an extension of the churchyard.

By this

time, Doncaster had two churches. St George’s was still within the bounds of

the castle, and St Mary Magdalene stood at the market place.

It is now generally accepted that St Mary Magdalene was the original parish

church. However as the castle fell into disuse, and

pressure for space at the market had increased, the old church was abandoned in

favour of St George’s. St Mary Magdalene was reduced to the status of a chapel,

and later a chantry. After the Reformation it became a town hall and school.

St Mary

Magdalene, from Rev Jackson’s Book

The Friars make Doncaster a literary centre

During the

thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, large numbers of friars arrived in

Doncaster who were known for their religious enthusiasm and preaching. In 1307

the Franciscan friars (Greyfriars) arrived, as did Carmelites (Whitefriars) in

the mid fourteenth century.

The friars

were itinerant and applied themselves to instruction and religious edification.

There was a house of Augustinian friars at Tickhill and houses of Franciscans

and Carmelites at Doncaster. To the public buildings there were added the

houses of the Carmelite and Franciscan friars.

The friars

brought literary knowledge and were centres of literature in the middle ages. The establishment of the two societies of

friars and their educational achievements further enhanced the growth of the

town as a place of significance.

The

Franciscans or Grey Frairs were divided into seven

wards or custodies in England. The Custody of York included Doncaster.

These Friars

Minors established themselves on the island formed by the rivers Cheswold and Don, at the bottom of French or Francis gate,

at the north end of the bridge known as the Friars' Bridge, some

time in the thirteenth century. On 1 September 1290 Pope Nicholas IV

granted an indulgence to those who visited their church. Archbishop Romanus in

1291 encouraged the friars to preach the Crusade at Doncaster, Blyth in

Nottinghamshire, and Retford.

Edward I

gave the friars 10s, through Friar Edmund de Norbury, on the occasion of his

visit to Doncaster on 12 November 1299. In January 1300

he gave them 20s for two days' food and 6s 8d for damages to their house when

he was at Doncaster, through Friar de Portynden. On 8

June 1300 his son Edward gave them 10s and in January 1301

he gave them 10s for the exequies of Joan, nurse of

Thomas of Brotherton. The friars at this time numbered thirty.

In 1316 Sir

Peter de Mauley, lord of the town of Doncaster, granted the Friars Minors a

plot of land adjacent to their dwelling-place.

In 1332

Thomas de Saundeby, the warden, and Friar Nicholas de

Dighton, along with Thomas de Moubray,

William de Halton, and John de Brynsale, were sued by

John de Malghum for having seized and imprisoned him.

In 1335 the King pardoned them for acquiring in mortmain without licence

in the time of former kings various plots in

Doncaster, then enclosed with a wall and dyke, whereon they had built a church

and houses. Between 1328 and 1337 the number of the friars varied between

eighteen and twenty-seven, as is evidenced by the royal alms granted to them by

the hand of Friars John de Bilton, Nicholas de Wermersworth, and others.

Sir Hugh de

Hastings, in 1347, left the friars 100s, 20 quarters of corn and 10 quarters of

barley. Their friar, Hugh de Warmesby, was authorized

in 1348 to act as confessor to Lady Margery de Hastings, Sir Hugh's widow, and

her family. Her son Hugh was buried in the church of St. Francis at Doncaster

in 1367. Another Sir Hugh Hastings in 1482 left a serge

of wax to be burned here in honour of the Holy Rood, and a quarter of wheat

yearly for three years.

Roger de Bangwell, rector of Dronfield, gave 20s to the convent and

12d to each friar in 1366. Thomas Lord Furnival of Sheffield in 1333, and Sir

Peter de Mauley in 1381, were buried in the church. Sir Peter left his best

beast of burden as mortuary payment and 100s to the convent.

Friar Thomas

Kirkham was admitted as Director of Divinity of Oxford in July 1527, his fee

being reduced to £4 because he is very poor. in November he was relieved

of many of his Oxford duties because he was warden of the Grey Friars of

Doncaster and could not continually reside in Oxford. Thomas Strey, a lawyer of

Doncaster, left 20 marks to the convent in 1530 and 26s 8d to buy the warden a

coat.

During the

Dissolution of the monasteries, the house was quietly surrendered 20 November

1538 by the warden and nine friars, three of them novices, to Sir George Lawson

and his fellows, which were thankfully received.

A manuscript

of the chronicle of Martin of Troppau formerly belonging to the friary was in

the possession of Ralph Thoresby in 1712.

The

Carmelites or White Friars arrived in Doncaster in the mid fourteenth century.

The

Carmelite friary, which Leland

described as a right goodly house in the middle of the town was founded

in 1350 by John son of Henry Nicbrothere of Eyum with Maud his wife and Richard Euwere

of Doncaster, who gave the friars a messuage and 6 acres of land. The priors of

the order asked permission of the Archbishop of York to have the place

consecrated in 1351. The earliest recorded bequest to them was made by William

Nelson of Appleby, vicar of Doncaster, in 1360.

In 1366

Roger de Bangwell, formerly rector of Dronfield, made

his will in the house of these friars, in whose church he wished to be buried.

A provincial chapter was held at this friary in 1376. The friars in 1397

received a royal pardon, after paying 20s, for acquiring without licence

several small plots, worth 12s 6d a year, for the enlargement of the

entrance and exit of their church. Two friars of the house, John Slaydburn and John Belton, were appointed papal chaplains

in 1398 and 1402.

It is said

that John of Gaunt was one of the founders, and his son Henry of Bolingbroke on

his journey from Ravenspur in July 1399 lodged at the

friary. Edward IV was entertained at the friary in 1470, Henry VII in 1486, and

the Princess Margaret Tudor in 1503. In 1472 Edward IV conferred the privileges

of a corporation on the convent, which is of the foundation of the king's

progenitors and of the king's patronage, and he licensed the friars to

acquire lands to the yearly value of £20. At the beginning of the sixteenth

century the Earl of Northumberland claimed the title of founder of the house.

Several

members of the Carmelite friary attained some distinction as writers. The House

of the Carmelites was a college of learned men. They included John Marrey or John Marr, who later went to Oxford and died in

1407; John Colley who flourished in about 1440; John Sutton, provincial prior

in 1468; and Henry Parker, who got into trouble by preaching on the poverty of

Christ and His apostles and attacking the secular clergy at Paul's Cross in

1464. Henry Parker is probably the author of the dialogue entitled Dives et

Pauper which was printed both by Pynson and by Wynkyn de Worde at the end of the fifteenth century. John Breknoke, keeper of the Dragon Inn at Doncaster, left the

friars some books in 1505.

On 15 July

1524 William Nicholson of Townsburgh attempted to

cross the Don with an iron-bound wain in which were Robert Leche and his wife

and their two children. They were overwhelmed by the stream

and they called for the help of our Lady of Doncaster. It was reported that

with her help, they were able to reach the shore. They came to the White Friars

and returned thanks on St. Mary Magdalen's Day, when this gracious miracle

was rung and sung in the presence of 300 people and more.

On the eve

of the Dissolution of the monasteries, the Carmelite house was internally

divided. The well known John

Bale, in about 1530, was a friar at Doncaster, and perhaps its prior. He taught

William Broman that Christ would dwell in no church made of lime and stone

by man's hands, but only in heaven above and in man's heart on earth.

During the Pilgrimage of Grace, the White

Friars Priory was used as a head quarters

while negotiating with Robert Aske at Doncaster. The prior, Lawrence Coke,

supported the rebellion. He was imprisoned in the Tower and in Newgate,

condemned by Act of Attainder a few days before Cromwell's fall, but pardoned

on 2 October 1540. It is not clear whether the pardon was issued in time to

save him from execution.

The house

was surrendered by Edward Stubbis, the prior, and

seven friars, on 13 November 1538 to Hugh Wyrrall and

Tristram Teshe, who made a book of the property and notified to Cromwell

that the tenements in Doncaster were in some decay, and that the image of our

Lady had already been taken away by the archbishop's order. A magnificent

plate, 5 ounces of gilt plate, 109½ ounces of parcel gilt, and 48½ ounces of

white plate, was sent to the royal jewel house. The net profit from the sale of

the goods seems to have been £21 18s. 4d. The site with dovecot and other

houses, a garden and orchard all surrounded by a stone wall and containing 2½

acres, was let to Wyrrall for 10s a year.

The

tenements in Doncaster included an inn called Le Lyon in Hallgate,

already let by the prior to Alan Malster for

forty-one years at 40s a year in 18 August 1538, a

messuage in Selpulchre Gate similarly leased on 2

September 1538 to Emmota Parsonson for 12s., and

various tenements, shops, and cottages, the whole property bringing in £10 17s

4d a year.

Towards the

end of the fourteenth century, Edmund Duke of York attempted to raise Stainford (Stainforth), further

down the Don into commercial importance.

Fifteenth

and sixteenth century Doncaster

In 1398,

Henry Bolingbroke (soon to be Henry IV) swore at Doncaster that he came only to

recover lands of inheritance as Duke of Lancaster, during his dispute with

Richard II. Bolingbroke landed at Ravenspurn with 100

men at arms. They reached Pickering

Castle and stayed there for two days before marching south. He then marched

via Pontefract to Doncaster, where he lodged with the Carmelites. By this time it is said that he commanded 30,000 men. While there he

took the oath, which he was later said to have broken. By 13 October 1399,

having imprisoned Richard II, who died in prison probably of starvation, Henry

was crowned Henry IV.

During the

War of the Roses (1455 to 1487), Doncaster was a place through which the

contending armies passed and repassed.

The Yorkist

Edward IV granted a further charter to the burgesses recognising their rights

and privileges. They were empowered to choose a mayor annually and two

sergeants at mace, to have a common seal and to hear pleas of trespass, debt

and other matters in the Guild Hall.

In 1470

there was an attempt to seize the throne from King Edward after the Battle of

Stamford, when the King came to Doncaster.

The

consequence of the dissolution of the monasteries in 1536 was the transfer of

significant wealth and power from ecclesiastical to private lay proprietors of

manors, lands and estates. Part of these lands fell directly into control of

previous owners of feudal interests, but often the new owners were new people

who would themselves become founders of considerable families. A new order of

gentry replaced many of the old feudal interests. The depreciation of money

also had the effect of favouring a new guard. Joseph Hunter listed the new

gentry families. They included Thomas Wray of Adwick in the Liberty of Tickhill

and William Fletcher of Campsall.

The churches

were generally respected. The chapel of St Mary Magdeleine in Doncaster fell at

this time. The fall of the Carmelite house at Doncaster likely diffused their

significant literary accomplishments.

The Pilgrimage of Grace was a

backlash to the Reformation and the insurgents took Pontefract Castle and

gathered in significant numbers at Scawsby Lees near

Doncaster. The sudden rising of the Don prevented a bloody engagement. However the movement soon spread into the northern part of

Lancashire. In the course of October the commons of

Cartmel restored the canons to the priory. The prior, however, more prudent or

less staunch than his brethren, stole away and joined the king's forces at

Preston. This was before he heard of the general pardon and promise of a

northern Parliament granted to the rebels at Doncaster on 27 October. The royal

stronghold at Tickhill prevented the rebels from marching south and the revolt

petered out after an uneasy truce was signed at Doncaster.

Eleven

people died on the plague in 1563 and Doncaster seems to have suffered badly

from plague in 1582 and 1583. There appears to have been a Pesthouse to which

people infected were interred.

There was a

rebellion by the Earls of Westmoreland and Northumberland in 1569 and Doncaster

was secured by Lord Darcy.

The

Doncaster Chronicle of 1582 provides some record of events, for instance that

there were 30 marriages at the church in Doncaster from September 1582 to

September 1583.

During the

period of threat from the Spanish Armada in 1588, the Earl of Huntingdon was at

Doncaster raising and training soldiers.

or

Go Straight to Chapter 11 –

the Vicar of Doncaster

or

Read

about the Parish Church of St

George at Doncaster

Meet William Farndale,

the Vicar of Doncaster and his brother Nicholaus de

Farndale and his wife Alicia

You can

also read more about Doncaster:

South

Yorkshire, the History and Topography of the Deanery of Doncaster in the

Diocese and County of York by Rev Joseph Hunter, 1828. A download copy of this book is

available from Yorkshire

CD Books.

The Making of South

Yorkshire,

David Hey, 1979

A History of

Yorkshire, “County of the Broad Acres”, 2005, David Hey

A

History of Yorkshire, F B Singleton and S Rawnsley, 1988

A History of

Yorkshire,

Michael Pocock, 1978

There are

separate Doncaster and Doncaster Parish Church

webpages with research notes and a chronology.