A History of Campsall

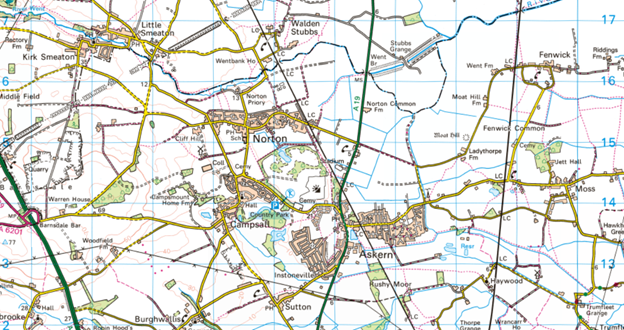

The history of the village of

Campsall north of Doncaster, where we find our ancestors in the sixteenth

century

Settlement

There was a small

Roman Fort, Burghwallis,

about two kilometres southwest of Campsall where the A1, the once Roman Road,

crossed the small River Skell, close to where Robin Hood’s Well is today.

The area

around modern Doncaster was forested until it started to be cleared in the late

Saxon period. At some stage perhaps from late Saxon times, areas were cleared

for settlement in the process called assarting. The growth of population and

villages, including Campsall and Loversall,

by the time of Edward the Confessor suggest that assarting had been pursued

vigorously by that time.

There were

about 170 vills of human settlement by the late Saxon period.

Settlement

was sometimes the result of the need to cross a watercourse, where permanent

crossing points were found. Sometimes settlement might have been no more than

the inclination of a family to settle on land, which later grew into a larger

habitation.

The informal

process of settlement was soon replaced by a recognition of rights of occupancy

of land by an elite class who came to own large estates. Thereafter it was no

longer open to every citizen to clear woodland for his own use, Well before the

Norman Conquest a right had been recognised in overlordship.

Saxon lords

came to surround themselves with dependents who held portions of land from him,

in return for rendering services. This is reflected in culture, in such tales

as Beowulf, which focused a desire to live

within the protection of the elite class, as protection against the perils of

unsettled places.

By the turn

of the first millennium, Dadesley (now Tickhill) and Doncaster had emerged as

burgesses. Other centres were also emerging including Campsall, which was

valued at £5 in a census of Edward the Confessor, being one of the larger

settlements.

The larger

seats of population came to be governed under the authority of a bors holder

who was elected at a general assembly. Townships were grouped in tens under a hundreder,

a superior officer who held courts. These hundreds came to be called wapentakes

in the areas to the north. Doncaster

and Loversall fell within the Wapentake

of Strafford. Campsall fell within the Wapentake of Osgodcross.

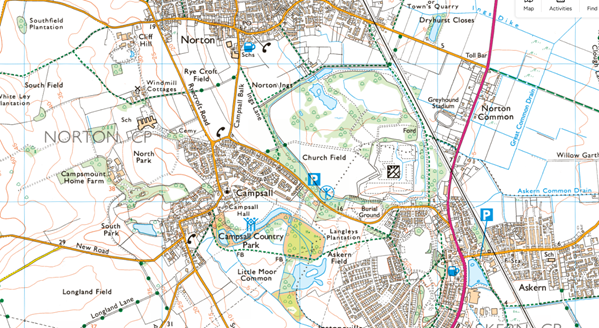

From early

times the parish of Campsall consisted of six townships or hamlets of Campsall,

Askern, Fenwick, Moss, Norton and Sutton.

Norman

Campsall

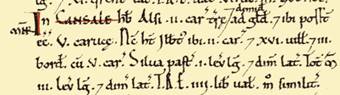

At the time

of the Domesday

survey in 1086, the area was in the possession of Ilbert de Lacy, the

founder of Pontefract Castle. Campsall appeared twice in the Domesday Survey

and both times was referred to as Cansale. Before the conquest Alsi had

two and a half caracutes there.

Campsall

then comprised 5 ploughlands with two Lord’s plough teams and 5 men’s plough

teams. There was also woodland of about 1 by half a league, or 5.5 kilometres

by 2.75 km.

There were

sixteen villagers and 3 smallholders.

It was rated

at £4 before and after the Conquest.

The fact

that Domesday does not mention a church at Campsall does not necessarily mean

that there was no Saxon church. The existing church includes some pre-Conquest

evidence. There might have been a chapel attached to the manor without

parochial rights. The earliest existing work in the church dates to the twelfth

century.

The manor of

Campsall thrived after the Conquest, rather than retracting, and was owned

directly by Ilbert de Lacy. Ilbert de Lacy was given a broad belt of land

across what became the West Riding of Yorkshire. He took the whole wapentakes

of Staincross and Osgodcross. Pontefract was head of his fee, so his estate was

called the honour of Pontefract.

St Mary

Magdalene at Campsall

Campsall

Priory was an Augustinian priory founded in the twelfth century. The priory

played a significant role in the local community and religious life. Only ruins

remain today.

The Church

of St Mary Magdalene had at least two main phases of twelfth century

construction which have been identified. At first it had a cruciform plan and

later nave aisles enclosing a west tower were added. Campsall church has the

most ambitious Norman west tower of any parish church in the Riding.

Subsequently, alterations were made to the aisle arcades, windows, chancel and

south doorway.

By the reign

of Richard I (1189 to 1199) Adam de Reineviles had recovered seizin of half

the church of Camsale against Henry de Puteaco and Dionysia, his wife. This

is the earliest mention of a church at Campsall.

Rev Joseph

Hunter in his South Yorkshire, the History and Topography of the Deanery of

Doncaster in the Diocese and County of York wrote that Campsal church

was the joint work of the Lacis, the chief lords, and the Reineviles, the

subinfudatories. It exceded the churches of Bramwith, Owston and Burgh in

magnificence as much as it did in the extent of country that was attached to it.

The Lacis

and the Reinvilles seem to have united in the foundation of the church at

Campsall. There were originally two rectors, one appointed by each family and

this continued until about the time of Henry III. Much of the church of

Campsall is the church erected at this time.

The

Reinevilles appear to have been succeed in the sub tenancy of the Campsall

lands by the Newmarches.

There is a

record in the Patent Rolls in 1285,

during the reign of Edward I, to deliver the gaol of Oxford of William de

Campsale, who was put in exigent …

The benefice

of Campsall was in the Taxatio

of Pope Nicholas IV in 1291. It had an annual value

of £66 13s. 4d, under the patronage of Henry de Lascy, Earl of Lincoln. By

a curious arrangement, the chapel

of St. Clement in Pontefract Castle had a one ninth share in the tithe from

Campsall (or the church’s right to a one tenth levy). This was probably because

Ilbert de Lacy and his successors held both estates and adopted this method of

supporting their Pontefract chapel.

The

evolution of Campsall into a centre of learning

Henry de

Laci, Earl of Lincoln, in the reign of Edward II, left a daughter, who was the

wife of Thomas, Earl of Lancaster, the grandson of Henry III. On the accession

of the House of Lancaster to the throne, the estates of the Lacis came to be

held directly by the Crown, but were still held by tenants.

In 1293,

during the reign of Edward I, Henry Lacy, Earl of Lincoln, Lord of the Honour

of Pontefract, obtained a royal charter for a market at Campsall, which would

suggest that it was a place of some consequence by that time. This charter

entitled the village to hold a weekly Thursday market and an annual four-day

fair each July during the festival of St Mary Magdalene. The fair continued

until 1627.

Over time

the Church dedicated to St Mary Magdalene came to resemble a collegiate church.

By the sixteenth century, the Valor

Ecclesiasticus records indicate that there was a vicar and a deacon at

Campsall. There were also chantry priests in the vicinity who sang masses for

the repose of the souls of individuals who left endowments to the church. The

chantry priests were supernumerary to the parish clergy and may have been

involved in teaching. It has been suggested that the first floor chamber above

the vaulted west bay of the south aisle at St Mary Magdalene, dating from the

late thirteenth century, might have been a space used for such a purpose.

The

emergence of the theologian Richard of Campsall (c1280 to c1350) suggests a

well established tradition of teaching in Campsall. Richard

of Campsall, or Ricardus de Campsalle, was a secular theologian and

scholastic philosopher at the University of Oxford.

He was

arguably one of the most important philosophers at Oxford just before the time

of William of Ockham.

Recent research suggests that several views described as Ockhamist by the end

of the fourteenth century might have originated with Richard of Campsall. A

fellow of Balliol College prior to 1306, Richard of Campsall became a fellow of

Merton College in 1306. By 1308 he was a regent master of arts. From 1322 to

1324 he was regent master of theology and in 1325 he served as locum tenens

for the chancellor. How long he lived is not known but he probably lived until

about 1350 or 1360.

Richard

of Campsall’s extant works include his Quaestiones super librum Priorum

analeticorum (c 1308), the Contra ponentes naturam (on universals),

a short treatise on form and matter (Utrum materia possit esse sine forma),

and Notabilia de contingencia et presciencia Det, all of which were

probably written about 1317 or 1318. Campsall’s Sentences commentary is

not extant, but Walter Chatton, Adam of Wodeham, Rodington, Robert Holcot, and

Pierre de Plaout cite him in their Sentences commentaries.

In the Questions

on the Prior Analytics Richard of Campsall proposed that training in logic

was the basis for all other sciences. He discussed the concepts of syllogism,

consequences, and conversion. He argued that the crux of logical thinking was

the syllogism and knowledge of consequences and conversion was necessary for

the study of syllogism, especially for converting “imperfect” syllogisms into

“perfect” syllogisms. In the area of supposition

theory, Campsall proposed views usually first attributed to Ockham,

including his distinction between simple and other types of supposition.

This was

deep stuff. Campsall must have been the crucible of some serious intellectual

debate to have produced a person such as Richard.

Meantime

there was continued ecclesiastical drama

in Campsall.

Writing to

the Dean of Doncaster, on 14 July 1324, the archbishop directed the Prioress at

Campsall to make Thomas de Raynevill undergo a penance imposed upon him for

committing the sin of incest with Isabella Folifayt, a nun of Hampole. The

penance was that on a Sunday, while the major mass was being celebrated in the

conventual church of Hampole, Thomas de Raynevill was to stand, wearing only a

tunic and bare-headed, holding a lighted taper of a pound weight of wax in his

hand, which after the offertory had been said he was to offer to the celebrant,

who was to explain to the congregation the cause of the oblation. The

punishment continued that on two festivals more penitencium he should be

beaten (fustigetur) around the parish church of Campsall.

The Patent Rolls, on 14 July 1328 during the

reign of Edward III referred to Meldon, parson of the church of Campsale.

The folk of

Campsall paid £7 2s 0d in taxation in 1324, the fourth highest contribution in

South Yorkshire.

In 1335 and

1336, there was a composition under the sanction of William, Archbishop of

York, in the time of Thomas de Bracton, rector and William de Mundene,

prebendary of the prebend in the chapel at Campsall, by which 100 shillings was

paid annually by the rector in lieu of tithe.

The Close Rolls in June 1335, during the

reign of Edward III referred to Thomas de Brayton, parson of Campsale

church, diocese of York.

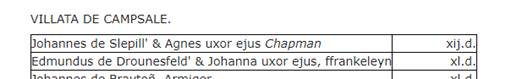

The 1379

Poll Tax included records of taxes paid by a chapman (or ‘middleman’) and

twelve craftsman, which suggests a degree of trade through Campsall. It is

likely at this time that the town did not become more than a local trading

centre.

On 19

October 1391 a pardon was given to John Wayte, Parson of Campsall, alias of

Aldborough, for non-appearance to answer Roger Broun of Boston, or Walter

Godard, citizen and brewer of London, for debts of £34 and £33 2s respectively.

The

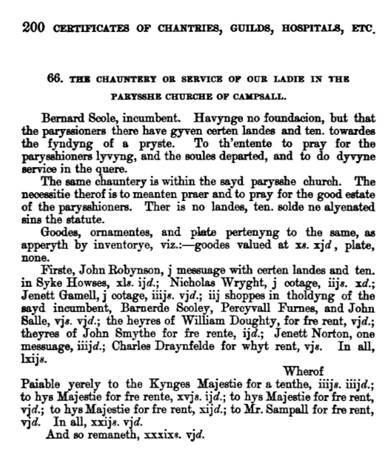

crucible of the Robin Hood stories

By

the fifteenth century the villagers at Campsall had formed a fraternity,

and hired their own priest to pray for the parishioners living and the souls

departed.

Most English

writers of the fifteenth century had at least some association with the Church.

Those who captured the rymes of Robehod into the written word were

therefore likely to have had some ecclesiastical background.

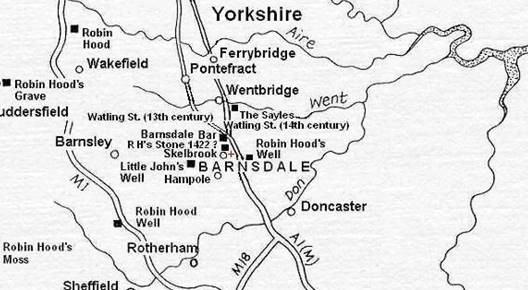

The earliest

references to Robin Hood are more associated with

Barnsdale Forest than Sherwood. Many of the names given to geographical

locations in Sherwood Forest were given in the nineteenth century. Some names

though are much older, such as Barnsdale’s Stone of Robin Hood, about 500m

north of Robin Hood’s Well, which was mentioned as a boundary marker in about 1540 by John Leland, in his Itinery in or about the years 1535-1543.

Robin

Hood and the Potter named Wentbridge (Went breg) in Barnsdale. In Robin Hood and

Guy of Gisborne, the action took place in Barnsdale, and the sheriff was

slain when he tried to flee to Nottingham.

![]()

![]()

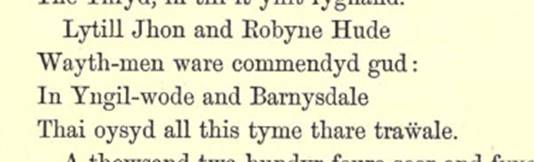

Robin Hood’s

association with Barnsdale was included in early written records of the tales

including by the Scottish poet and Augustinian canon Andrew of Wyntoun in his Cronykil

of Scotland of circa 1420.

Robin

Hood in Barnesdale Stood was quoted in a case by a judge in the court of Common Pleas in 1429.

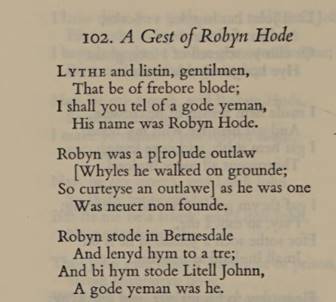

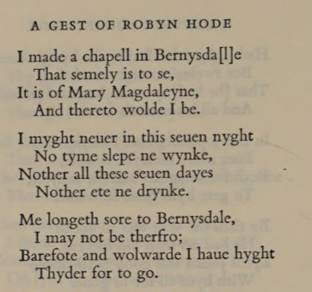

In the late

fifteenth century, the tales were brought together into A Gest of

Robyn Hode, which was structured into sections or fyttes. Various

editions of the Gest were printed between 1490 and 1550. The Gest

of Robin Hood places Robin Hood firmly in Barnsdale.

The

references in the stories of Robin Hood,

including Barnsdale, the Saylis and Wentbridge suggest a very local knowledge

of those who captured the stories into writing. Doncaster is just seven miles

to the south. By 1540 its population was about 2,000.

The

locations with which Robin Hood is associated, like the stories themselves, are

imagined over centuries of storytelling. The places, like to stories, are

ephemeral and locating the green wood precisely is not the right approach to

take. Yet there is no doubt that the idea of the green wood has a very close

association with Barnsdale, Campsall, and the area immediately to the north of

Doncaster. Robin Hood’s domain, though flexible to the imagination of countless

story tellers, clearly stretched to Doncaster. My purpos was to haue dyned

to day; At Blith or Dancastere (Gest, Fytte 1, 22). Robin Hood’s ultimate

betrayal was to the knight, Sir Roger of Doncaster. Barnsdale forest was then

at the eastern edge of the great swamp land that dominated the land westward to

the Humber estuary.

There is no

forest at Barnsdale today, but a large area around Campsall was once forested.

It may even have stretched past Doncaster to merge with Sherwood. The medieval

records do not though suggest forest at Barnsdale was an administered royal

forest like Pickering,

with its forest verderers and regarders. Barnsdale or Bernysdale was

likely to have been a lightly wooded area that was not officially a forest, but

it was a place of ambush in the fourteenth century. Highway robbery in

Yorkshire in the fourteenth and fifteenth century was a significant problem and

there were recorded holdups around Barnsdale and Wentbridge. There was at least

one inn at Wentbridge, where stories would have been retold. The area along the

road from Doncaster and Pontefract at that time, was likely a melting pot of

storytelling.

In 1540 John

Leland described the road which followed the modern A1 near Campsall as bandit

country and on his journey from Doncaster to Pontefract, Leland wrote From

Dancaster to Causeby lesys by a mile and more, wher the rebelles of Yorkshir a

lately assembled. He also described the area The ground betwixt

Dancaster and Pontfract in sum places Yorkshire, meately wooddid and enclosid

ground : in al places reason- Rably fruteful of pasture and corne.

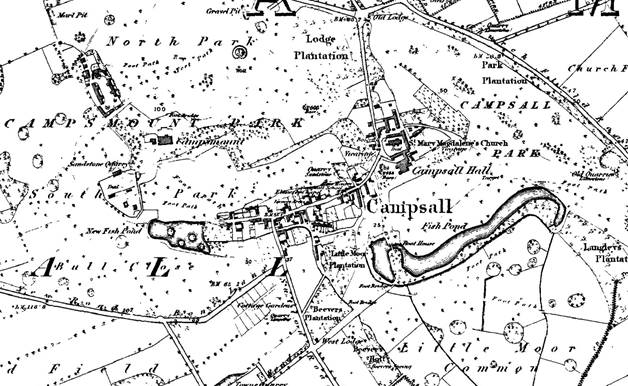

There is a

particular association of the stories with Barnsdale and Robin Hood’s chapel,

dedicated to Mary Magdalene.

The parish

church at Campsall, still the Church of St Mary Magdalene, coincides with

Robin’s chapell in Bernysdale. There were several churches dedicated to

Mary Magdelene, including the parish church in Doncaster itself, but the

church at Campsall is the most likely association as it sits in the heart of

the area associated with Barnsdale.

There is

only one church dedicated to Mary Magdalene within what might reasonably be

considered to have been the medieval forest of Barnsdale, being the church at

Campsall. Indeed, a local legend suggests that Robin Hood and Maid Marion were

married at the church of Saint Mary Magdalene, at Campsall.

Fifteenth

century Campsall

In 1415,

John was parish clerk of Campsall. In 1427 John Corngham, canon of Windsor, was

rector of Campsall. Robert Dykes became rector until he died, presented by

Henry VI. John Okham became Rector in 1429, presented by Henry VI and resigned

to go to the church of Menstoke in Winchester. William Normanton then became

Rector until he resigned. Robert Ayscough became Rector on 3 March 1443 until

he resigned. Robert Addy became chaplain of Campsall to the archbishop on 24

May 1466, presented by Edward IV.

A great

change took place in 1481 when Edward IV (in his second period of reign)

granted the rectory of Campsall to the Priory of Wallingwells in

Nottinghamshire, a small house of Benedictine nuns. It was a poor foundation

before this gift.

Peter Wylde

was presented as vicar of the church on 18 October 1483, presented by the

University of Cambridge. In the following year Thomas Rotherham, Archbishop of

York decreed that henceforth the benefice of Campsall should be served by a

Vicar, and gave the appointment to Cambridge University.

This meant

that the church at Campsall was appropriate to external influences, and the

local people were deprived from having a person from their own community.

Richard Balderstone

was presented as vicar of the church on 13 October 1505, presented by the

University of Cambridge and died while vicar. Henry Swaynborough became vicar

on 26 May 1507.

Later

History

After the

dissolution of the monasteries in 1536, under Henry VIII the rectorial tithes

passed into lay hands.

John Lommas

BA became vicar on 16 July 1552 until he died in 1574.

Robert

Middleton held the tithe of Campsall in 1557 as tenant to the Hastings family

of Fenwick.

On 29

October 1564, William

Farndell married Margaret Atkinson at St Mary Magdalene Church in Campsall.

John Brooke

became rector on 27 March 1574, appointed by the archbishop, possibly because

there were questions by then about the ownership of the university regarding

the right to present vicars. In 1579 the rectory of Campsall was granted to Sir

Christopher Hutton. In 1585 Sir Christopher Hutton conveyed the rectory to

Edward Heron of Stamford.

A Survey in

1627 recorded that The towne of Campsall had in tymes past the priviledge of

a market, which is now decayed and lost by discontinuance.

A map of

1740 shows Market Flatt to the north of the village, which was probably the

site of the market.

Continuing

Campsall’s tradition as a centre of learning, the Campsall Society for the

Acquisition of Knowledge was founded in the late 1830s when the family of Charles

Wood rented Campsall Hall and employed young scholars, including from

Continental Europe, to tutor their sons Neville, Willoughby and Charles Junior.

The father, Charles Thorold Wood, had been a captain in the Royal Horse Guards,

and was an ornithologist. His wife, Jane, was an early adherent of homeopathy. Neville

(b 1818) at this time was editor of a journal called The Naturalist, a

contributor to The Analyst and had, in 1836, published The

Ornithologist's Text-Book. Their tutors included Giacomo Chiosso, later

professor of gymnastics at University College London and inventor of the

Polymachinon, a forerunner of the modern exercise machine, Edwin Lankester,

Leonhard Schmitz and Ferdinand Moller. The Society had probably ceased to exist

by the early 1840s.

A

Topographical Dictionary of England of 1848: described Victorian Campsall, the

parish St. Mary Magdalene, in the union of Doncaster, Upper division of the

wapentake of Osgoldcross, W. riding of York; containing 2149 inhabitants, of

whom 385 are in the township of Campsall, 8 miles (N. N. W.) from Doncaster.

The parish consists of the townships of Askerne, Campsall, Fenwick, Moss,

Norton, and part of Sutton; and comprises by computation 9700 acres, of which

1470 are in the township of Campsall, including the hamlet of Barnsdale. The

village is pleasantly situated on a gentle acclivity, about seven miles distant

from the river Don on the south, and on the north the same distance from the

Aire. Stone of good quality is quarried. Camps Mount, the seat of George Cooke

Yarborough, Esq., is an elegant mansion, standing at the head of a fine lawn,

and embowered in luxuriant foliage; and Campsall Park is also a handsome

residence. The living is a perpetual curacy, valued in the king's books at £16.

16. 8.; net income, £128; patron and impropriator, Mr. Yarborough. The tithes

were commuted for land in 1814. The church is a large ancient edifice, and has

some fine specimens of Norman architecture. The remains of a Roman road may be

traced.

Campsall

1857

The church

was restored between 1871 and 1877 by G. G. Scott. Restoration of stonework on

the tower was in progress in 2005.

or

Go Straight to Chapter 11 –

the Vicar of Doncaster

Campsall

bibliography

Arts Council

of Great Britain: London, Hayward Gallery, English Romanesque Art, 1066-1200,

London, 1984

Borthwick

Institute, Faculty papers, Fac. 1871/2; Faculty Book 6, 18-19

Campsall, St

Mary Magdalene guide, The Story of St. Mary Magdalene Church, Campsall

Yorkshire, n. p., 1965/1969

K. J.

Conant, Cluny, Les églises et la maison du chef d’Ordre, Mâcon, 1968

J. Fowler,

“Note on the restoration of the west doorway of Campsall church” Proceedings of

the Society of Antiquaries of London 8 (1879-81), 130-31

J. Hunter,

South Yorkshire: The History and Topography of the Deanery of Doncaster, in the

Diocese and County of York, 2 vols. J. B. Nichols & Son, London, 1828-31

J. E.

Morris, The West Riding, 2nd ed. London, 1923

N. Pevsner,

Yorkshire: West Riding. The Buildings of England, Harmondsworth, 1959, 2nd ed,

Revised E. Radcliffe, 1967

Victoria County

History: Yorkshire, II (General volume, including Domesday Book) 1912,

reprinted 1974

There is a

separate Campsall webpage with research

notes and a chronology.