Skelton and the Old Church

The History of Skelton-in-Cleveland

Having recently arrived in Wilton near

Kirkleatham from Campsall near Doncaster, in about 1588 the family moved again

to Moorsholm in the Parish of Skelton, in a period of religious tension.

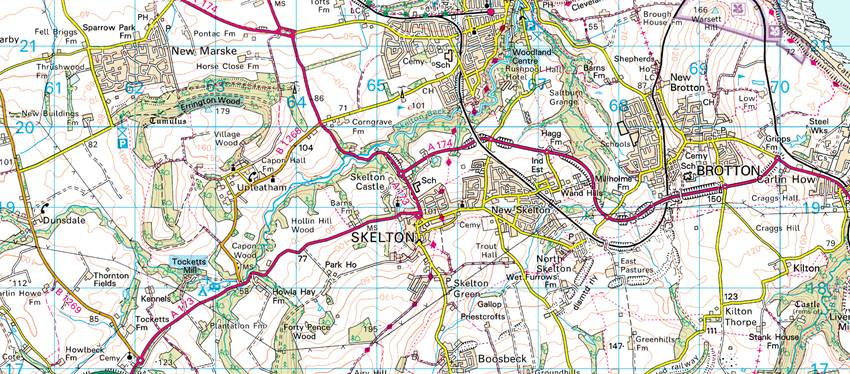

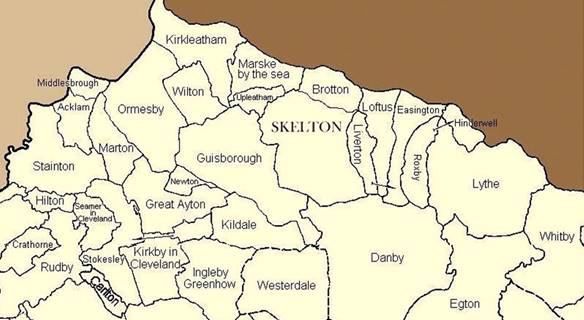

Directions

Approach

Skelton on the A173 from Guisborough or the A174 from Brotton and Loftus.

I suggest

you head for the Old Church beside Skelton Castle on the approach to Skelton

from Guisborough, and take in Skelton’s history from

there.

Skelton’s

early history

Sceltun or Scheltun in the eleventh

century; Scelton in the twelfth century; Sceltona, Scheltona

and Skeltona in the thirteenth century; Skolton in the fourteenth century,

Skelton-in-Cleveland comprises North Skelton, Skelton Green and New Skelton.

Its name derives from skell, a brook or rivulet and tun, a town

or village.

John Walker

Ord’s History and Antiquities of Cleveland, 1846 summarised Skelton’s

history. From this little nook of Cleveland sprang mighty monarchs, queens,

high chancellors, archbishops, earls, barons, ambassadors, and knights, and,

above all, one brilliant and immortal name, Robert Bruce, the great Scottish

patriot, who, when liberty lay vanquished and prostrate in the dust, and the

genius of national freedom had fled shivering from her native hills, bravely

stood forth, its latest and noblest champion, and, in defiance of England's

proudest chivalry, achieved for Scotland a glorious independence, and for

himself imperishable fame.

Skeletons of

wild ox and deer have been found in peat bogs just a few miles from Skelton and

have been dated to around 7,000 BCE. Many Bronze Age burial sites or howes

on the hills around Skelton provide the first real evidence of humans in these

parts.

It is

thought that the people buried at Hob Hill in the Anglo Saxon

period were outlying settlers of the Anglo Saxon region called Deira and spent their lives in the Skelton

area, possibly using Skelton beck as a water supply.

The first

church might have been a simple timber building. Anglo-Saxon-Scandinavian

coffins suggest its early origin. There are three medieval stone coffins and a carved coffin

lid in the church.

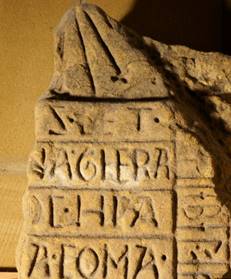

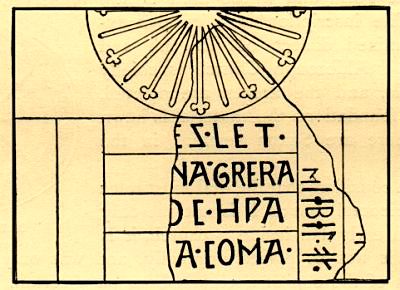

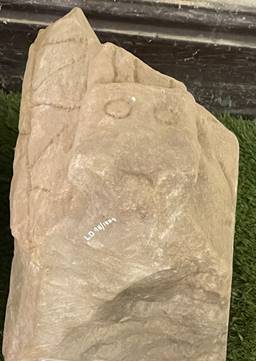

In the

1840’s a carved stone was found in the old Churchyard, near the Castle. It

appears to be part of a sun-dial,

like Orm Gamalson’s

Kirkdale sundial of the original Farndale lands, and must have come from

the old Anglo-Saxon Church which was replaced in 1325.

Part of the

sundial’s semicircle remains and four hour lines, just

like the Kirkdale sundial, two of which are crossed, likely representing midday

and 2pm. Like Kirkdale, the sundial had probably been divided into twelve hour spaces.

Below the

lines of the sundial are what remains of four lines an inscription in Old

Norse, with part of a line of runes down the side.

Margaret

Scott Gatty (1809 to 1873) quoted Bishop Browne’s conclusion that The runes, I read as DIEBEL OK, which Mr Magnusson

says is good Danish, of latish date, for ‘devil and’. He tells me that

GRERA is part of the word ‘to grow’, and COMA is ‘to come’. The words ‘devil

and’ may well be a pious curse on creatures of that kind.

From the

style of the inscription this stone appears to belong to the early part of the

twelfth century.

Two

Anglo-Scandinavian Cross shaft fragments from the tenth or eleventh century, Fragment of a

Scandinavian child’s tombstone with a dragonesque hogback and a rudimentary

probably

sandstone quarried at Egton

carving of a creature, about tenth century

Both Displayed

in Skelton Old Church

Norman

Conquest

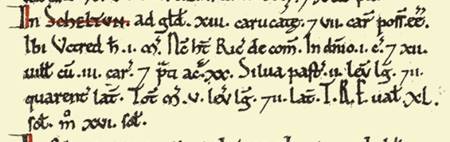

The Skelton

lands were held by Uhtred prior to the Conquest and comprised a manor and

thirteen carucates (a carucate being the land which a team of eight oxen could

plough in a year). They were recorded in the Domesday Book as

including seven ploughlands with one lord’s plough team and three men’s plough

teams, 20 acres of meadow and mixed woodland stretching two leagues by two

furlongs. There were twelve villagers. The value of £2 reduced to 16s after the

Conquest, perhaps the consequence of the harrying of the north.

The lands were given to Count Robert of Mortain and Richard of Sourdeval was the tenant in chief.

There have

been suggestions that an earlier ancestor of the House Bruce, Robert de Brix, served

under William the Conqueror during the Norman Conquest and suppressed the

northern rebellions during the harrying of the north. It is now thought that

this came from the evidence of unreliable lists compiled in the later Middle Ages.

Rather the

Bruce interest arose when Henry I defeated his elder

brother and rival Robert Curthose at the Battle of Tinchebrai

in Normandy in 1106. After his victory Henry I redistributed land from Robert Curtose’s supporters, including Robert de Stuteville

to his new men, including Nigel d’Albini, ancestor of

the Mowbray family and Robert de Brus.

The Bruce family thus came to hold

large estates based on Skelton, Danby and in Kildale.

Skelton

therefore followed the same ownership as Danby

until the division in 1272 of the lands of the third Peter de Brus, when the

castle and manor of Skelton with five knights' fees passed to Walter de Fauconberg and his wife Agnes.

A Royal

Charter in 1124 by David I of Scotland granted Robert De Brus the Lordship of Annandale in

Scotland. Robert De Brus was a friend and supporter of David, and his second

son, also called Robert married the heiress to Annandale. The Bruce lines then

split, with Robert’s eldest son Adam 1 de Brus continuing the senior Skelton

line, and the second son, Robert II de Brus beginning the Annandale line. In

time, Robert’s In time the Scottish decent would pass

to Robert the Bruce, crowned as the Scottish King on 27 March 1306, to lead the

fight for Scottish independence against Edward I of England. Robert rallied his

troops at Bannockburn, By Oppression’s woes and pains! By your Sons in servile chains! We will drain our dearest veins, But

they shall be free!,

and establish an independent Scottish monarchy.

In the

Declaration of Arbroath, this descendant of Skelton would declare of Scotland, As

the histories of old time bear witness, it has held

them free of all servitude ever since. In their kingdom one hundred and

thirteen kings of their own royal stock have reigned, the line unbroken by a

single foreigner.

Only a

decade after the grant of Annandale, Henry I in died in 1135. David of Scotland

refused to recognise Henry's successor, King Stephen. Instead, David supported

the claim of his niece and Stephen's cousin, Empress Matilda, to the English

throne. Robert of Skelton and Annandale fell out with David and he bitterly

renounced his homage to David before taking the English side at the Battle

of the Standard at Northallerton in 1138.

Before the

battle, Robert made an impassioned plea to David. The appeal was rejected.

Robert, and his eldest son Adam, joined the English army, while his younger

son, Robert, hoping to recover his recently acquired Scottish inheritance,

fought for David. At the Battle of the Standard in 1138 the elder Robert took

prisoner his own son, the younger Robert, Lord of the lands of Annandale.

Skelton was

thus the principal seat of the de Brus

family early in the twelfth century. The castle was probably built in about

1140 and was lived in by eight generations of the de Brus family until the

death of Peter de Brus III in 1272.

The medieval

castle has not survived. The site of the castle is situated on high ground near

the Skelton Beck in the north of the parish, and the house which was later

built on the same site is surrounded by park lands and woods and on three sides

by a moat. The castle and its successor mansion has

been the dwelling place successively of the House Brus, and later the Fauconbergs, Conyers, Trotters, Stevensons and Whartons.

The first

Lord, Robert de Brus was buried in Guisborough

Priory in 1141. The new lord of Skelton was Robert’s eldest son, Adam I de

Brus, who had fought with his father at the Battle of the Standard.

Whilst still

a minor, Adam II de Brus of Skelton was dispossessed of his castle at Danby in about 1145 by his guardian and uncle,

William d’Aumale, Earl of York.

Plantagenet

Skelton

In 1196

Peter I de Brus inherited the barony of Skelton but was soon in heavy debt.

Initially he had been a faithful follower of King John, accompanying him to

Normandy. Peter was given his first chance to rejuvenate the Skelton barony and

buy back the vill and forest of Danby which he did for £1,000. In 1207 he

purchased the wapentake of Langbaurgh, near Great Ayton, which included the

whole tenant of Cleveland. In 1208, in order to obtain

the money demanded by King John. Peter de Brus made an agreement with his

Cleveland tenants within Langbaurgh, by which he agreed to limitations in the

exercise of his authority in return for a guarantee that the knights and free

tenants would make up any shortfall in the rent of forty marks charged by the

king. The witnesses were Roger de Lacy, Robert de Ros, Eustachia

de Vescy, Walter de Faucumberge.

The Charter

made between Peter de Brus and the tenants of Cleveland was lodged with the

Prior of Guisborough. It has been suggested by some that it was a pre-cursor to

Magna Carta, when the Barons strove to place similar limitations on King John’s

powers. Peter de Brus held 11 “knights fees” of the honour of Skeltone in Yorkshire.

Also in

1208, Peter de Brus was given custody of his Scottish relative, William de

Brus, Third Lord of Annandale, as a hostage of King John to ensure the

behaviour of the King of Scotland.

However

Peter de Brus became increasingly disillusioned with King John when John

abrogated the Magna Carta and in February 1216, he had to flee Skelton Castle

to avoid capture by the king.

From the 8

to 10 February 1216, King John attacked and took Skelton Castle. Peter de

Brus’s men were taken prisoner. On 15 February 1216, John agreed to receive

Peter de Brus and Robert de Ros under safe conduct with all such as they should

bring with them unarmed, to a conference, to treat with him about making their

peace with him; and the said safe conduct shall hold good for one month from St

Valentine’s day. And for greater security our lord the

King wills that …..Archdeacon of Durham, Wydo de Fontibus,

Frater Walter, Preceptor of the Templars in the district of Yorkshire, with one

of Hugh de Bailloel’s retinue, shall go with them in

person to the Lord King, and escort them; and they have Letters Patent from the

King to that effect; and the said letters are the same day handed to the

aforesaid parties, Thomas, Canon of Gyseburn, being

further added to their numbers.

On 26

February 1216 King John issued the following mandate: We command you that

you receive and see to the safe keeping of the prisoners whose names are

underwritten, taken at Skelton Castle, who will be sent to you by Dame Nicholas

de Haya –that is to say, Godfrey de Hoga, Berard de Fontibus,

Anketil de Torenton, Robert

de Molteby, Stephen Guher,

William de Lohereng, Robert de Normanby, Roger le

Hoste, Robert de Gilling, John de Brethereswysel,

Thomas Berard’sman and Ralph de Hoga.

In July and August the King issued further orders that prisoners taken

at Skelton Castle should be ransomed.

King John

died later in 1216 and Henry III became King aged 9.

In 1219 Peter de Brus was forgiven for his opposition to King John and

recovered Carlton and other manors in Cleveland, which the Crown had taken from

him.

In 1227,

Peter de Brus was given licence to hold a Market at Skelton on Mondays.

In 1265,

Skelton castle was surrendered to Henry III by Peter III who was suspected of

supporting Henry’s son, Prince Edward.

There are records

of the castle being used for keeping prisoners from the reign of King John and

during the reign of Henry III.

In 1269 a

deed recorded a quitclaim by Alice and Helena, Agnes and Hauisia

sisters, to Peter de Bruis the third, of all their land of Scelton

late belonging to Richard, the reeve, (prepositi) their uncle, viz., a toft and

croft at the entrance of the town of Scelton towards

the east late held by Walter Blevent; 1 acre in Scelton fields lying between the tilled land of Sir Peter

de Bruis called Roskeldesik and the half ploughland

belonging to the Mills; an assart late of Wm. Winde,

lying between Langhacres and the vale

of meadows of Scelton; 1 acre given by Wm. Cusin to Ralf, son of Wine, lying between Roskeldesic and the half ploughland belonging to the lord’s

mills; and 2 1/2 acres in the territory of Scelton on

Lairlandes; for the rents of 1d. to them and their

heirs, heirs of Wm. Cusin for the acre between Roskeldsic and the half ploughland, 2d. to the same for the

2 1/2 acres on Lairlandes, 1d. to the heirs of Rolf

son of Wine for the acre given to Ralf by Wm. Cusin,

and 1d. to Richard Briton for the assart. Witnesses :- Sir Adam de Hilton, Sir Simon de Bruis, Sir

Stephen de Rosel, Sir Berard de Fontibus, John de Tocotes, John de Nutel, Wm. Pitwaltel, Robt de Tormodeby,

Geoffrey the Cook (Coco) Hugh Hauberger, Matthew the

Clerk (clerico)

North of the

castle is a mill on the Skelton Beck, which is probably the site of one of the

mills appurtenant to the manor in 1272, and to the east is a fish-pond

also mentioned at that date.

Peter de

Brus III of Skelton Castle died in 1272. For nearly two hundred years six

generations of the De Brus family of Skelton Castle had had male heirs. Their

possessions had grown through marriage as the law directed that on marriage the

property of the wife became the husband’s property. Peter de Brus III’s elder

sister had pre-deceased him and both were childless. The de Brus Estates were

therefore divided between his four remaining sisters.

At this time

the de Brus estates were divided amongst four

daughters, Agnes, Lucia, Margaret and Laderina. The first two daughters stayed within the

Cleveland area. Agnes married into the de Fauconberg

family and inherited Skelton castle and nearby estates, whilst Lucia married

into the de Thweng family of Kilton

castle.

A Charter in

the eighth regnal year of Edward I, Hammer of the Scots, on 25 May 1280 declared

For Walter de Fauconberg. The King to Archbishops,

greeting. Know ye that we have granted, and by this our Charter confirmed to

our beloved and faithful Walter de Faucunberge, that

he and his heirs for ever have free warren in all his demesne lands of Skelton,

Stanghow and Mersk, Uplithum, Redker,

Grenrig and Estbrune in the

County of York. Provided that those lands be not within the bounds of our

forest, so that no one enter those lands to hunt in them, or to take anything,

which may belong to the warren, without the licence and will of him the said

Walter, or his heirs, upon forfeiture to us of £10; wherefore he will….

In 1291 a

dispute arose between Skelton Castle and Guisborough Priory over an area of

land around what is now Skelton Ellers, called ‘Swarthy Head’ and then called Swetingheved. This was on the edge of the Skelton

hunting park which stretched east to the castle and south over Airy Hill to Margrove Park. Walter de Fauconberg

agreed to maintain the hedges and ditches to prevent the deer straying onto the

prior’s meadows and arable land and to pay tithes on the deer themselves.

The Lay Subsidy

of 1301, authorised by a Parliament at Lincoln, was a tax on the whole

population and was based on a fifteenth part of each person’s movable

possessions. Among the taxpayers of Skelton were a merchant, a fuller, a

weaver, a potter, a tanner, a baker, a smith, a butcher, two carpenters and

three carriers (pannierman, wainman

and a carter). There were 63 taxpayers in Skelton who paid a total of £5 13s.

Multiplying this by 15 gives the total value of these villagers’ possessions as

£84 6s. The number of taxpayers in other places in the North Riding of

Yorkshire, for comparison, were Guisborough 85, Whitby 96, Marske and Redcar

89, Yarm 72. There were likely many poorer, labouring people who did not pay

tax.

Walter de Fauconberg died in about 1304 and was succeeded by his son

Walter, who died in about 1318, his heir being John his son, who died in 1349.

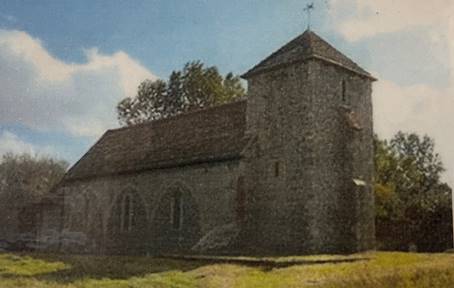

A new church

seems to have been built in stone by the Fauconberg

family in about 1324. Part of the fabric of the older church was incorporated

into this new church. It was probably of a similar size as the church which

stands today.

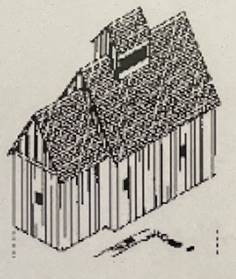

The

fourteenth century church was later replaced but might have looked something

like this

In the Lay

Subsidy of 1334 Skelton was assessed at £2, compared with Yarm £9, Guisborough

£4 and Stokesley £1 4s.

In 1349, the

twenty third regnal year of Edward III, an Inquisitiones

Post Mortem surveyed the assets of the Fauconbergs on the death of John Fauconberg.

In demesne, 24 bovates of weak and Moorish land, each worth 4

shillings…before the mortality of men in these parts this year. 30 acres of

meadow each worth 1 shilling per annum before the Death. 3 water mills of which

one is weak and ruinous….worth £4 before the Death.

The castle

was described in this year as being difficult to maintain. This was the year

that the Black Death hit Yorkshire,

which may well have ben the cause of John’s death

There was

also mention of a park of oaks with game, called le Wespark

and Maugrey Park with deer. The area to the west

of Skelton Castle, to Skelton Ellars and over Airey Hill to Margrove

Park was part of the private woodland hunting reserve of Skelton Castle.

In this and

the following years the plague killed a half to two thirds of the population of

England. It would seem from the above that most of the population of Skelton

died.

A carved

sandstone effigy of a knight with hands clasped in prayer. His shield is

decorated with three birds and his sword hangs below. Chain mail armour is

visible. He is probably a member of the Thweng

family, or Sir Robert Capon who died in 1346. The effigy is in Skelton’s Old Church.

John’s son

Walter died in 1361 and was succeeded by his son Thomas de Fauconberg.

A third of the manor, passed as a dower to Walter’s widow Isabel. Thomas

granted his two-thirds of the castle and manor and the reversion of Isabel's

third, for his lifetime, to Henry Percy Earl of Northumberland, who held the

whole manor on the death of Isabel in 1401.

The Skelton

estate was then taken into the custody of Henry IV, due to Thomas Fauconberg’s intermittent mental health issues. In 1403 the

King granted custody of the estate to Robert and John Conyers.

The mentally

ill Thomas Faucomberge died in 1407 when the estate

settled on Walter de Fauconberg, the son of Sir Roger

de Fauconberg, who was a brother of Sir Thomas.

The

Inquisition Post Mortem shows the estate included a

waste burgage, four waste messuages, and cottages either ruinous or

waste or paying nothing. The condition probably reflected the decimation

of the population of Skelton, after the Black Death, which was about 400 at the

beginning of it. Among the long list of possessions, which also includes the

Manor of ‘Mersk’ and Upleatham and many areas of land with now unrecognisable

names is:

In the

town and territory of Skelton in Cleveland: 1 built messuage with garden; 1

croft and 6 bovates held by William Shupherde; 1

built messuage with garden; 2 crofts and 1 bovate held by John Proctour; 1 waste messuage and 1 bovate by John Walkere; 2 bovates by John Harpour;

3 waste messuages and 1 bovate by William Mason senior; 1 burnt messuage, a

close called ‘Cadycroft’ and a parcel of land called

‘le Wanles’ by the same; a third part of a messuage

and of a bovate by Roger Homet; with all the services

of these tenants; 4 a. of foreshore at ‘Thilekelde’,

‘Roskeldesyke’ and ‘Grenwalde’

held by John Proctour; 1 close of herbage in ‘Burghgate’ and 1 called ‘Copyncroft’

by John Donaldeson; 1 built cottage by Thomas de

Newsom, and 1 by John Byrde; 1 with garden and croft by William Whytekyrke; 1 garden and croft with 9 a. by William Syng; 1

built cottage with 2 crofts by Robert Hogeson, the

lord’s villein; 1 ruinous cottage by Sibota Westland;

1 croft of herbage called ‘Bruyscroft’ by William

Westland; 1 built burgage and 1 croft by John Pottere;

1 close of herbage called ‘Kyrkebyclos’ and 1 plot

used for making pots (pro ollis inde

faciendis) by the same; 2 waste cottages in ‘Marketgate’ next William Lambard’s tenement on the south,

let for a rent of 12d.; 1 cottage now in the lord’s hands, formerly held by

William Westland for 20d., now paying nothing; In a place called Stanghow 1

built cottage, 2 waste cottages, 1 bovate and a tenement called ‘Blackhall’

held by Thomas Carlele; and 1 built messuage, 2 waste

messuages and 4 bovates by John West. Also a third part of 3 watermills in

Skelton with its members, called ‘Holbekmyll’, ‘Saltbornmyll’ and Skinningrove mill; a third part of a

fulling mill, and of the profits of the oven, toll, market and fair there, of

the assize of bread and ale, of the court of Skelton, of agistments in pasture

and feedings not in severalty, of waste, of casualties arising in wood or

plain, as in hawks, sparrowhawks, falcons, and other birds of prey or game, of

warren and free chase, waifs and strays, etc. and of the mining of lead, iron,

marl and coal and of quarrying of slate and other mines in the lordship of

Skelton and its members.

Walter died

in the same year that he inherited the estate, which then passed to his

daughter, Joan. She inherited the estate as an infant. She was described as an

‘idiot’ from birth. Joan married Sir William Neville, son of Ralph Neville, the

Earl of Westmorland. The castle therefore passed, by her marriage, to Sir

William Neville. They made

alterations to the castle in 1428. William Neville was summoned to Parliament

as Lord Fauconberg in 1429, and

was created Earl of Kent in 1461. He died in January 1463 seised

of Skelton in right of his wife, who being of unsound mind held no lands after

his death.

Alicia

Neville was the daughter of Joan Fauconberg and Sir

William Neville. She married Sir

John Conyers (1435 to 1469), later Lord Conyers.

Inheritance

of Skelton was always a little messy. At Joan's death in 1490 her heirs were

her grandson James Strangways, son of her daughter Elizabeth, wife of Sir

Richard Strangways, and William Conyers, son of her daughter Alice who married

Sir John Conyers of Hornby. Skelton came to the Conyers, although the

Strangways seem to have held some interest in the manor, which followed the

descent of the manor of West Harlsey.

Tudor

Skelton

In 1490

Skelton Castle was inherited by William Conyers, when it was described as

ruinous. William Conyers married Anne Neville

(1475 to 1550).

The Lay

Subsidy of 1542 evidenced that in Skelton well over half the taxpayers assessed

for the Lay Subsidy paid at the lowest rate, on goods valued at less than £1 or

240 d. As before, the Lay Subsidy was a taxation system based in rural areas of

a fifteenth part of a person’s moveable goods including crops. In towns it was

a tenth.

After the

dissolution of the monasteries in about 1545, the Church at Skelton was granted

to the see of York. The Archbishop is still patron of the

living, and therefore controls appointment, payment, and vicarage of local

vicar.

The Conyers

estate passed via Christopher Conyers to John Lord Conyers, on whose death in

1557 it was divided among his daughters and co-heirs, three of whom, Anne wife

of Anthony Kempe, Katharine wife of John Atherton and Elizabeth wife of Thomas

D’Arcy, survived. The fourth daughter, Joan (or Margaret), died a minor in

1560.

Nicholas and Agnes

Farndale, with their son William Farndale and

his new wife Margaret, and their daughter Jean Farndale

settled in Wilton near Kirkleatham in

about 1565, after William and Margaret’s wedding in St Mary Magdalene Church in

Campsall in 1564 and before Jean’s

wedding to Richard Fairley in Kirkleatham in 1567.

They lived there,

about five kilometres west of Skelton, but within about a decade or so, William

and Margaret and their family moved to Moorsholm, in the parish of Skelton.

This

emigration occurred in the midst of the Elizabethan

age, thirty years after the Reformation during Henry VIII’s reign (1509 to

1547) had fundamentally transformed English society by removing Rome’s

supremacy. The First

Act of Succession in 1534 had resolved Henry’s marital and succession

issues and two Acts

of Supremacy confirmed Henry VIII as supreme head of the church of England.

This was the first time England had brexited from the

European world. To most ordinary folk, these issues were probably remote and

caused little to change, but there was a heightened awareness of religious

difference which impacted everywhere. This religious difference would have

impacted on the Farndales living around Doncaster in 1536 when the Pilgrimage of Grace

reached both York and Doncaster. It probably impacted all corners of the nation

during the reign of Bloody Mary (1553 to 1558), which brought a devastating

Counter Reformation and the burning of protestants, cruel heresy laws, when

John Foxes’s Actes and Monuments of these

Latter and Perillous Days, known as the Book of

Martyrs, compiled the shocking stories of the persecutions.

Elizabeth I

(1558 to 1603) brought some calm and toleration back to her realm. The Act of Supremacy

1558 was An Acte restoring to the Crowne its

Jurisdiction over the State Ecclesiasticall and Spirituall, and abolyshing all Forreine Power repugnaunt to the

same, The

Act of Uniformity 1559, authorised a book of common prayer which was

similar to the 1552 version but which retained some Catholic elements, and the Thirty

Nine Articles 1563 provided a compromise return to a new Anglican world.

This was the foundation of a new religion which was later called Anglicanism. “It

looked Catholic and sounded Protestant.” It was a religious middle way. It

was a compromise and perhaps the foundation of the British spirit of

compromise. It contrasted to a time of Catholic versus Protestant polarisation

in Europe. Elizabeth had little sympathy for hardliners from either wing of the

religious divide. She stopped heresy trials. This was a brave new world, though

still to be threatened for a while by Spanish invasion plans and a medley of

plots.

Over time

however, there were acts by her monarchy which supressed Catholicism, which was

still popular in Yorkshire. The Recusancy

Acts in 1558 required attendance at Church of

England services, returning to Henry VIII’s Reformation. Those who refused to

do so were called Recusants and were

brought to Court to face penalties. In Cleveland, at first Egton, with 9 Recusants, was its only

centre. By 1586, Brotton had 19 presentations for

Recusancy, Egton 13, Hinderwell 10

and Skelton 8.

The mid 1560s were therefore a period of renewed hope, whilst

still threatened by opposing ideas. It was in 1568 that Mary Queen of Scots

escaped from Loch Leven Castle and fled to England and was interred in a

succession of castles, including Bolton Castle in Wensleydale. Soon after Mary’s arrival, a

rebellion began in the pro Catholic north of England led by the earls of

Northumberland and Westmoreland. The Rising

of the North of 1569, also called the Revolt of the Northern Earls or

Northern Rebellion, was an unsuccessful attempt by Catholic nobles from

Northern England to depose Queen Elizabeth I of England and replace her with

Mary, Queen of Scots.

It was at

this time that Jean Farndale had married Richard Fairley in Kirkleatham on 16

October 1567. This was the first event which marked the family’s arrival there.

The

Fairleys were a Scottish family once known as de

Ros who adopted the name Fairlie when they were granted lands at Fairlie

(Ayrshire) by Robert the Bruce, that

Scottish King of Yorkshire descent. This is a locative name from Fairlie in

Ayrshire near the mouth of the Forth of Clyde. By 1881 the later family were

centred around Midlothian and Lanarkshire, but also Durham and Northumberland.

The family was also in Ireland. The two branches of the Bruce family had lands

in Annandale in Scotland and around Skelton.

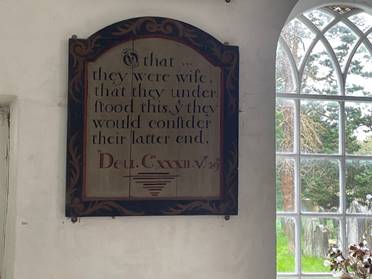

This sign

on the wall of the Old Church at Skelton might reflect the mood as the family

set up home there, where they continued to live through the English Civil War

There is

record of disagreement between the three husbands. The story goes that each

allowed their part of the castle to fall into disrepair so that the others

wouldn’t have any benefit of it.

Anthony

Kempe, the husband of Anne Conyers sold their part of the Skelton Estate to

Robert Trotter. Robert was the son of a Robert Trotter senior of Pickering and married to Margaret who came

from Pudsey.

As the sixteenth century ended, there were early signs of

the future industrial

revolution which would soon reinvent Cleveland. By

1595, Sir Thomas Chaloner established alum works at Belman Banks. The first

profitable alum site in Yorkshire was opened in 1603 at Spring Bank, Slapewath, which was then part of Skelton. John Atherton, possibly in

conjunction with his brother-in-law’s family, the D’Arcys,

opened Springbank alum

works at Slapewath in about 1603. This was probably

the first alum works in north-east Yorkshire.

Britain had been an agricultural nation and wool was its

chief export. Alum was used in the dyeing process as the setting agent and was

also needed in the tanning of hides. It was a highly valued product, which

previously had been imported. In 1610, James I made Alum production a monopoly

of the Crown. By 1616 alum production began at Selby Hagg, near Hagg Farm,

Skelton. Ships anchored off Saltburn to

transport the finished product. They brought with them casks of urine, which

was mixed with the liquid that had been obtained from the calcined shale as

part of the process. This was probably done in an Alum House near Cat Nab in Saltburn. The shale liquid ran

from Selby Hagg by gravity down a trough that followed the course of Millholme Beck.

In 1577,

Anthony Kempe (1529 to 1597) sold his share in the estate, including the

castle, to Robert Trotter

Meantime the

Skelton Parish Registers for baptisms started from 1571, marriages from 1568

and burials from 1567.

Seventeenth

Century Skelton

In the

turbulent years of the early seventeenth century, there were some folk of Skelton who were getting themselves into trouble as Papists.

Recusants were people who refused the sacraments of the Church of

England. In Skelton the list included William Milner and Allison his wife.

Agnes, the wife of Robert Allenbye. Jane, the wife of

Robert Nelson. Alice, the wife of John Staynhous.

Robert Sawer. Elizabeth Staynhous. Recusants 8 or 9 yeares, but poore laborers. Robert Trotter Esquier,

Margaret his wife ; noncommunicants

this last yeare. Private baptisme

“Xpofer Burdon” husbandman had a childe

secretly baptised, where and by whome they know not.

Robert Allanbye, Joan, the wife of William Nelson.

Jane, the wife of Richard Locke. Jebbs widowe Burton widowe r Averell

wife of Xpofer Burdon, John Staynehous.

Thomas Staynhous, Richard Staynhous.

Poore labouring people which came to church before the xxvth

of Marche 1603 & since are become Recusantes.

Robert

Trotter died in 1611 and was succeeded by his son Henry, who died in 1623.

Henry's son and heir George was succeeded by Edward, who married Mary daughter

of Sir John Lowther, bart, of Lowther, to whom he

conveyed the manor in 1659.

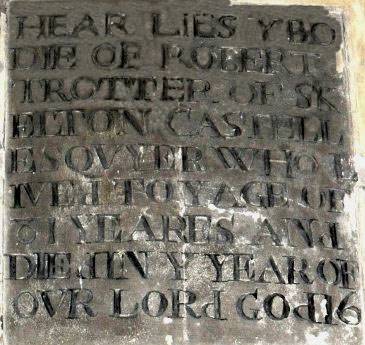

Skelton Old

Church. Here lies y bodie of Robert Trotter of

Skelton Castle Esqvyer who lived at y age of 81 yeares and died in

Year of Our Lord God 1611.

In April

1613, at the Quarter Sessions held at Thirsk Robert Tose, Curate of Skelton in

Cleveland, was charged with keeping an alehouse there, contrarie

to the statute in such case made and provided.

The oldest grave-stone still to be found in the old Church yard at

Skelton was placed in September 1632, commemorating John Slater.

Folklore has

it that Cromwell passed close to Skelton, but missed the Castle hidden in the

woods. The locals, however, were heard and given a good beating on Flowston. A small skirmish took place somewhere between

Skelton and Guisborough between Royalists under the command of Colonel Slingsby

and Parliamentarians under Sir Hugh Cholmley and Sir Matthew Boynton. Slingsby

was taken prisoner and some of his men killed. The story of the Civil War is

told in more detail in Chapter

12 of the Farndale Story.

The current

Old Church of Skelton was rebuilt in 1785, so the modern structure is from a

later period. Its austere feel however seems to transform you into a world of

seventeenth century puritanism.

It has been suggested

that the brasses on the Fauconberg blue marble stone

in the floor of the old church at Skelton were torn off by the Puritans during

the Protectorate in about 1653.

On 3 October

1670 at Malton Quarter Sessions it was ordered That

John Tooes of Skelton in Cleveland having been bound

to appear at the Sessions to answere for alluring and

entycing’ mens wifes and on other complaints is to find good sureties for

his good behavious and to appear at next Sessions.

Edward

Trotter was lord of the manor in 1681.

Trotter died

in 1708, and was succeeded by his grandson Lawson Trotter, son of his son John.

Lawson Trotter still held the manor in 1721 and in 1729, but afterwards sold it

to Joseph Hall, his sister's husband, probably before 1732.

The

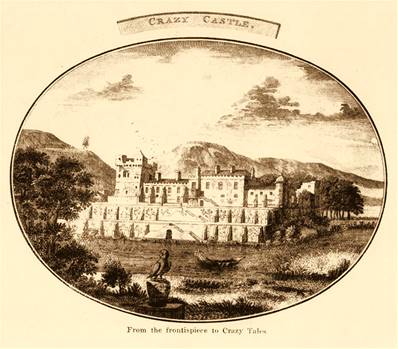

Hall-Stevensons and the Crazy Castle

Joseph Hall

died in 1733 and was succeeded by his son John Hall, who assumed the name of

Stevenson in addition to his own. John Hall Stevenson was lord of the manor

till his death in 1785. His son Joseph William, who succeeded him, died a year

later, his heir being his son, another John Hall Stevenson, who assumed the

name of Wharton.

John Hall

Stevenson (Lord of the Manor of Skelton from 1733 to 1785) was quite a

character. He married Anne Stevenson and added Stevenson as his surname after

his marriage to Anne, the daughter of Ambrose Stevenson and Ann Wharton. He was

a Cambridge scholar and poet. John was an author (including Crazy

Tales) and friend of Laurence Sterne, who wrote “The Life

and Opinions of Tristram Shandy, Gentleman”.

John Hall

Stevenson in 1741

John had a

reputation for throwing wild parties for his friends (including Lawrence

Sterne, Zachary Moore and Panty Lascelles) who were known collectively as the “Demoniacs”.

He was

something of a hypochondriac and wouldn’t get out of bed if there was an east

wind blowing. The story goes that Sterne paid a youth to fix the weathervane so it never showed an east wind.

The castle

at this time was in a state of disrepair, earning for itself the nickname “Crazy

Castle”.

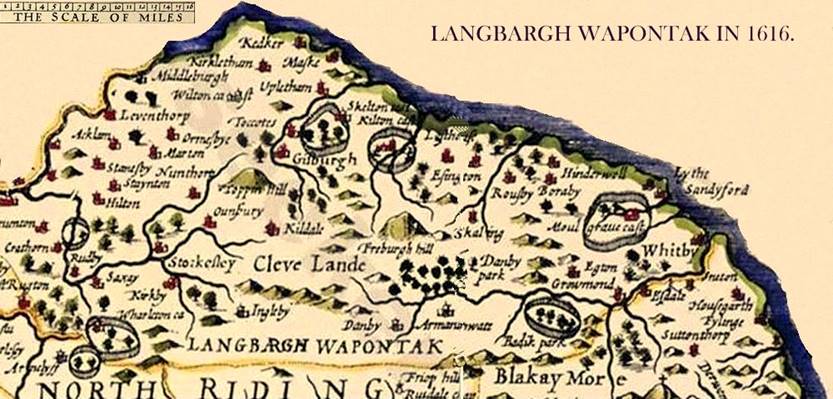

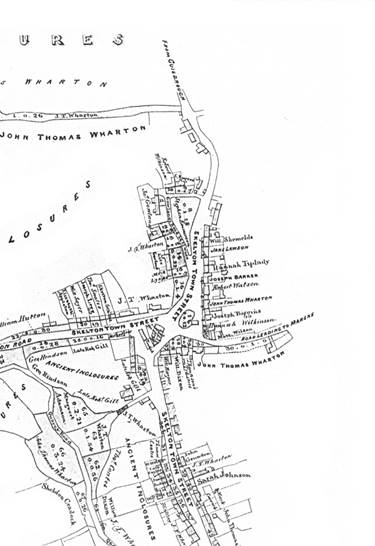

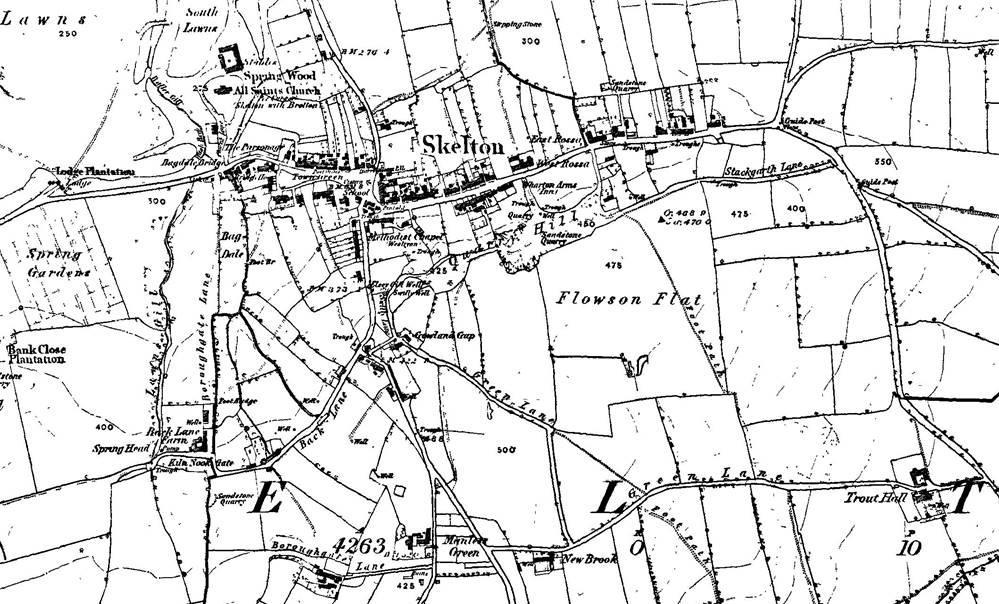

Map of Skelton,

1740

In 1764, the

Archbishop of York, Robert Hay Drummond, sent out a Questionnaire to all his

Parish priests. The Skelton in Cleveland, Curate, Thomas Kitching replied as

follows:

Admitted

20 August 1760. Deacon 18 December 1743, [Samuel Chester]. Priest 22 September

1745, Samuel Chester. 1. There are about 240 families, 5 of which are Quakers

and 4 are Papists. 2. The Quakers have a meeting house at ‘Moorsholme’,

but whether it is licenced or not I do not know. They assemble there every

Sunday in the morning in small numbers. Their speaker is one Philip Narzleton of Moorsholme

aforesaid. 3. There is no publick or charity school

within this Parish. 4. There is no alms-house or hospital in this Parish. There

are some lands and some cottages belonging to the Church, the profits of which

are ‘applyed’ [and I believe very honestly] to the

repairs of the nave or body of the Church. This Curacy was augmented in the

year 1718 by a benefaction of £200 from the Trotter family and others who had

connexions with that family, by £200 more given by the directors of Queen Ann’s

Bounty and by £25 given by the late curate. An estate called ‘Sadler Hills’ in

this Parish was purchased 1735 and the yearly rent is £18. 5. I do reside in

the parsonage-house. 6. I have no curate. 7. I perform divine service at

Skelton on 2 Sundays in the mornings and in the afternoons. I attend Brotton,

which is annexed to the curacy of Skelton. On the third Sunday I perform divine

service at Brotton in the morning and in the afternoon

I attend Skelton. I preach twice every Sunday and I

make service at Skelton on holy days. 8. I know of none who come to church that

are not baptized, neither do I know of any of a competent age, who are not

confirmed. I have baptized no adults since your Grace came to be Archbishop. 9.

I catechise at Skelton and Brotton alternately from the beginning of Lent till

Whitsuntide. Many of my parishioners send their children, but very few of their

Servants. At your Grace’s last confirmation, or rather before it, the Servants

did attend me at the times appointed and I did all I could to meke them understand the principles of our holy religion. I

know of no exposition they make use of. 10. The sacrament is administered once

every quarter both at Skelton and Brotton. I give notice of it on the preceding

Sunday in the form appointed by the Book of Common Prayer. The number of

communicants in the parish may amount to 375. At Easter 156 did communicate. At

other times the number is not so great. I have refused the sacrament to none

since I was admitted curate. 11. The chapel at Brotton is annexed to the cure

of Skelton and is served in the manner above specified. It is distant from

Skelton about 3 measured miles. There is no particular

endowment belonging to Brotton. We have no chapel in ruins. 12. There

has no public penance been performed since your Grace came to be Archbishop,

neither do I know of any commutations of penance made by any of my parish

within that time.

On 24

November 1770 William Smith, a Miller, was murdered at night in his bed at home

in Skelton in Cleveland by Luke Atkinson who also lived in the village. On

Sunday evening he told Mr Wharton that he had without the least provocation for

3 weeks before the perpetration of the murder several times a strong

inclination to commit it; but had always got the cruel thought driven from his

mind, till the unhappy night in which he effected it, when he went to bed, but

could not rest; that he arose from out of his bed and fell to prayer, in hopes

of diverting these thoughts; but so irresistible was the impulse, that he at

last went to the house of William Smith armed with a mattock and hatchet, broke

open the door with the mattock, and found him asleep in bed, where he struck

him several times on the head, but whether with the mattock or hatchet he did

not remember; and that afterwards he took the deceased’s purse containing one

half guinea, a quarter guinea, about five shillings in silver and sixpence in

copper. He declared that his wife was ignorant of the murder and died

penitently.

Upleatham’s Big Stone in the old church at Skelton. It marked the spot

of a duel where a member of the Smallwood family was killed. It may originally

have been a village cross or a graveyard monument.

The old

church near Skelton Castle was rebuilt for a third time in 1785. This is the

present, now redundant, Church. It was funded by a sizeable donation from John

Hall-Stevenson and by selling leases on the pews. The names of many of the

subscribers can still be seen, painted on the end walls of the box pews.

The 1785

church is a plain structure. There is also a kind of transept, forming a pew,

in the middle of the north wall, with a fireplace at its north end. This pew

was reserved for the Skelton Castle family. The triple decker pulpit is

opposite the Skelton Castle family pew. The vicar preached from the top pew;

lessons from the Bible were read from the middle level, and the parish clerk

sat on the lowest tier from where he took a register of the names of those who

attended the service. Between 1593 and 1650, it had been a punishable offence

to fail to attend an Anglican church, so perhaps the pulpit originated in the

second church.

The eighteenth century church prioritised hearing the words of

the Bible over Holy Communion at the altar, sol the pews between the pulpit and

the chancel arch face backwards. During Communion, these churchgoers had to

stand up to face the altar.

The

Wharton Era

John Hall

Stevenson Junior was the son of Joseph William Hall Stevenson. He changed his

surname to Wharton to comply with the terms of a legacy in

order to inherit his great-great-aunt Margaret Wharton’s estate at Gilling, near Richmond. He inherited a

considerable fortune from his aunt, much of which he spent of demolishing the

castle and building his new home.

The castle

was thus rebuilt between 1788 and 1817 and later extended to become a country

house in the nineteenth century. It was constructed for John Wharton, by then

Member of Parliament for Beverley who had inherited the ruined Skelton Castle

from his father Joseph in 1786.

Skelton

Castle

The present

house is built of dressed sandstone with a roof of Lakeland slate. It is a

two-storey block with a five bay frontage. It

incorporates some remains of the medieval castle.

Practically

the whole of the site of the old castle was cleared and the hill on which a

keep seems to have once stood was destroyed. Some terraces which overhung the

moat were also removed. John

Farndale wrote the present Skelton Castle, comparatively speaking, is a

modern structure. Nothing now, it is said, remains of the castle in the olden

time, nor of the baronial fortress of De Brus. A writer speaking on this

subject says that “It was built about 1140, and was a

beautiful specimen of antiquity and picturesque loveliness, being nearly

surrounded by a deep glen, finely wooded.” In the year 1783, the whole of this

beautiful edifice was pulled down, and in its stead, the present castle was

erected; but though it may not be thought equal in splendour and beauty to its

ancient predecessor, yet standing, as it does, in the centre of sylvan

landscapes, which scarcely can be surpassed for loveliness, and being

associated with recollections of the chivalrous achievements and illustrious

history of the De Bruces, who resided here many years after the Norman

conquest, this castle and its environs will always be looked upon with more

than usual interest by the antiquarian and the tourist. The present possessor

of this large and ancient domain being fond of agricultural pursuits, has been

indefatigable in improving the property since he came into possession of it,

and no gentleman could have done more than he has towards making the poor of the

district comfortable by alloting them portions of

land and building them more commodious abodes.

Ord recorded

in his History of Cleveland that the old ruined castle had a magnificent tower,

and it was described in the Cotton

manuscripts as an ancient castle all rent and torn, it seemed rather by

the wit and violence of man than by the envy of time. This was its ruinous

condition in John Hall Stevenson's time that earned it the title of Crazy

Castle.

Later

internal alterations were made in 1892 and in 1908.

John Wharton

of Skelton Castle was returned as the MP for Beverley, beginning a 40 year association with that East Riding town. It was to

lead to his eventual financial downfall. Beverley had the right to send two

members to Parliament and it was a nationwide custom to bribe officials and the

electorate. The only people allowed to vote were adult males who owned land, so

called freemen, and Beverley had an above average number of these, as well as

voters who lived outside the area. It became advantageous to have more than two

candidates in order to find out who could offer the

most in sweeteners. As well as making direct payments to the voters, candidates

paid for such things as travel expenses, ribbons, innkeepers fees, musicians,

and security guards. The expenditure did not end there. The MP prior to J

Wharton paid over £650, including £50 towards flagging the streets in 1786, £20

a year on coal for poor freemen, £10 per year to the master of the grammar

school, £25 for the races, and 5 guineas to the Charity school, besides

providing a buck and a doe for the mayor’s table. John Wharton must have made

an excellent job of this bribery as he received 908 votes from the 1,069

voters, including a high proportion of the working-class and London voters.

Wharton was an active Whig with radical views. In Parliament he was a staunch

supporter of the abolition of slavery and favoured relief for Roman Catholics

and constitutional and Parliamentary reform. His resounding success in the 1790

election gained him a considerable popular following in Beverley and his overt

political position led to the development of clear Whig and Tory factions in

the town. It was said by the Whig grandees, It

is beyond the power of imagination to conceive the popularity of Wharton here

… Perhaps it has never happened in the History of Electioneering that out of

1,050 voters 908 should be on one side in favour of our friend and his

principles.

John Wharton

lost the election in Beverley in 1794 after he disagreed with some of his

previous supporters over the war with France. He was made a Captain in the

North Riding of Yorkshire Yeoman Cavalry.

The winter

of 1794 to 1795 was one of the severest in living memory with hard frosts and

snow from December to March. Snow still lay on the Cleveland hills in May. Bad

weather conditions had a more serious effect on people’s lives then than today.

Most worked in agriculture and were wholly dependant

on the land. Fuel was used up. The fact that the country was at war with France

added to the problems. There was a shortage of corn, which drove up the price

of bread and there were riots in some places. Poaching was rife. The landed

classes had always considered that any wildlife that moved across their

property belonged to them. From Norman times, and

probably long before, any peasant who trespassed on the Lord’s hunting preserve

was liable to harsh penalties. To save a family from starvation the risk was

often taken in Skelton. In these difficult times the punishments were severe.

From 1760 night poachers were liable to 3 to 6 months

prison with hard labour and second offenders given 6 to 12 months with a public

whipping. From 1782 to 1799 there were only 26 convictions for poaching in the

North Riding of Yorkshire.

Despite

these harsh punishments it was recorded by October 1780 the game upon the

manors of John Wharton of Kilton, Skelton and Brotton was

nearly destroyed.

So, in 1800

new legislation made convicted poachers liable to 2 years hard labour and a

whipping. Offenders over 12 could be sent for military service.

John Wharton

was returned to Parliament in 1799 as the MP for Beverley, coming second in the

bye-election which had been caused by the death of the sitting MP. He now stood

as an Independent and was opposed by J. B. S. Morritt of Rokeby Park in the

North Riding of Yorks. He had mixed success in the elections which followed up

to 1826.

Meantime in

1801, the first national census was carried out by house to

house enquiry, by the local Overseers of the Poor. The population of

England and Wales was estimated to be 9 million. The population of Skelton was

700. There were 317 males and 383 females. There were 167 inhabited houses,

with 180 families. 6 houses were uninhabited. 171 people worked in agriculture

and 279 in trades. In the 20 years from 1781 to 1801 there were 612 baptisms,

399 burials and 168 marriages.

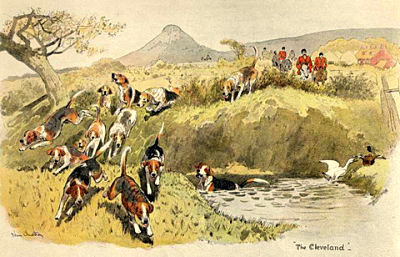

The Roxby

and Cleveland Hounds were formed on 5 June 1817 and John Andrew, the notorious smuggler,

and direct ancestor of the author of this website, of the White House, Saltburn

Lane was made Master.

A E Pease in

The

Cleveland Hounds set the scene.

At the

Angel Inn at Loftus, on a summer’s

afternoon, we may picture John Andrew Snr, Isaac Scarth, Henry Clarke, Henry

Vansittart Esq, Thomas Chaloner Esq and the other signatories to the rules then

drawn up, sitting with their tumblers of punch, making a treaty.

In 1817,

Mr John Andrew was appointed master. The Hounds were taken to Saltburn, then

but a fishing hamlet on the sea-shore, where, for more

than fifty years, the management was in the hands of the Andrew family. They

hunted foxes in the winter, and, with a few of the old Hounds, otters in the

summer. A few years after this the Roxby was dropped from the name of the pack,

and they became the Cleveland. John Andrew hunted them until 1835, assisted by

his son, John Andrew Jun, who took them when his father gave them up. John Jun

was master until 1855, when they were taken by his son, Tom, who had them until

1870, having, previous to becoming master, acted as

huntsman to his father. Tom, altogether, hunted the Hounds for thirty-three

years, having many grand runs, and sometimes hunting when the snow was deep on

the ground.

By 1821, the

population of Skelton Parish was 1235, as recorded by the local Curate, William

Close. Skelton villages’ population was approximately 700.

On 4 August

1821 a most dreadful storm of thunder and lightning occurred at Marske and

Skelton in Cleveland. At Skelton Mr Mackereth, surgeon of Guisbrough,

was passing from one part of the village to the other, over some fields and in

the middle of the pasture was knocked down and laid insensible for two or three

minutes. Two women in the adjoining field, making hay, were struck down, but

providentially, the whole three have perfectly recovered.

The Topographical

Dictionary of Yorkshire by Thomas Langdale of 1822 described Skelton Castle

situated on the brink of a large sheet of water, in many places 50 feet

deep, which nearly surrounds the castle, except an opening to the south.

Skelton was described as in the parish of Skelton, east division of the

wapentake and liberty of Langbarugh, Skelton Castle

the seat of John Wharton Esq, 3 ½ miles from Guisbrough,

11 ½ from Stokesley, 16 from Stockton, population 700.

Baines

Directory for 1823 listed the inhabitants of Skelton, with a population of

around 700: Castle: John Wharton MP. Curate: Rev William Close. Attorney:

Thomas Nixon. Blacksmiths: Thos Crater, Robert Robinson, William Young.

Butchers: William Lawson, Isaac Wilkinson, William Wilkinson. Corn Millers:

Robert Watson, William Wilson. Farmers and Yeoman: William Adamson, John

Appleton, Thomas Clarke, James Cole, James Colin, William Cooper, Steven

Emerson, John

Farndale, Robert Gill, William Hall, Edward Hall, Jackson Hardon, William

Hutton, Sarah Johnson, William Lockwood, John Parnaby, Thomas Rigg, William

Sayer, William Sherwood, John Taylor, William Thompson, Robert Tiplady, William

Wilkinson, Richard Wilson. Grocer and Drapers: John Appleton, William Dixon,

Ralph Lynass, Thomas Shemelds,

John Alater. Flax dresser: McNaughton D. Joiners:

William Appleton, Leonard Dixon, Mark Carrick, Joseph Middleton. Schoolmasters:

Atkinson M, John Sharp. Shoemakers: Robert Bell, Luke Lewis, Thomas Lowls, George Lynass, Thomas

Steele. Stonemasons: Thomas Bryan, John Pattinson. Straw hat makers: Sarah Sarah, Esther Shields. Weavers: Stephen Edelson, Thomas

Dawson, John Robinson, Robert Wilson. Land agent: John Andrew. Victuallers:

William Bean at Duke William, William Lawson at Royal George. Woodturner: James

Crusher. Gamekeeper: Frank Thomas. Plumber and Glazier: William Gowland.

Sadler: Thomas Taylor. Shopkeeper: Eliza Wilkinson. Carriers: Marmaduke Wilson

- to Guisborough on Tuesday and Friday, departing 8am and returned 4pm; Robert

Wilkinson to Stockton on Wednesday and Saturday, departing 4am and return 8pm,

to Lofthouse on Monday and Thursday departing 9am and return at 6pm; Letters

were brought to Guisborough by coach and thence to Skelton by daily horse post

arriving at 10am and mail taken back at 3pm.

John Wharton

was defeated in the election at Beverley in 1826 and retired from politics,

heavily in debt.

Victorian

Skelton

By 1831, the

population of Skelton was 781. In the last 30 years its population had

increased by 81. The national population about 14 million. The number of

females in Skelton was 396. Males numbered 385. Of these 138 were over 20. An

entry in the Parish Register for this year recorded 174 Families living in

172 Inhabited houses with 12 uninhabited. There was no current house building.

This record further divided these families into 100 employed in Agriculture, 42

in Trade/Manufacture and 24 Others. Agriculture occupiers

1st Class 39, 2nd Class 73 and Labourers 26. Manufacturers – None. Retail

trades and Handicraft – 43. Wholesale and Capitalists, Clergy, Office Clerks,

Professional and other Educated Men – 1 [presumably the Vicar]. Labourers non Agriculture – 15. All other males over 20 – 1. Male

servants 20 and over – 18. Male servants under 20 – 10. Female servants – 22.

The Great

Reform Act 1832 extended the right to vote slightly and altered constituencies.

Up to this time only about 3 % of householders qualified to vote, based on land

ownership. The new rules were still based on wealth and now about 5 % had the

vote. Skelton was part of the North Riding of Yorkshire and there were only 4

representatives for the whole County. Up to 1821 this had been only 2.

Voting

boundaries in 1832

One of the

longest cold periods, beginning January 1837, with temperatures down to -20 at

Greenwich, and lasting some 7 to 8 weeks.

In 1841, the

Rev J C Atkinson, a local historian, described visiting local cottages.

We then

went to two cottage dwellings in the main street. As entering from the street

or roadside, we had to bow our heads, even although some of the yard-thick

thatch had been cut away about and above the upper part of the door, in order to obtain an entrance. We entered on a totally dark

and unflagged passage. On our left was an enclosure partitioned off from the

passage by a boarded screen between four and five feet high, and which no long

time before had served the purpose originally intended, namely that of a

calves’ pen. Farther still on the same side was another dark enclosure

similarly constructed, which even yet served the purpose of a henhouse. On the

other side of the passage opposite this was a door, which on being opened gave

admission to the living room, the only one in the dwelling. The floor was of

clay and in holes, and around on two sides were the cubicles, or sleeping boxes

– even less desirable than the box beds of Berwickshire as I knew them fifty

years ago – for the entire family. There was no loft above, much less any

attempt at a ‘chamber’ ; only odds and ends of old

garments, bundles of fodder and things of that sort and in this den the

occupants of the house were living.

Martin Farndale of full age, bachelor, labourer of Skelton son of George Farndale, labourer married Elizabeth Taylor of full age, spinster of Fogga, Skelton, daughter of James Taylor, farmer at the

Parish Church Skelton on 19 February 1842. Elizabeth Taylor was the

granddaughter of the smuggler king turned master of the Cleveland Hunt, John Andrew.

On 7 August 1848, the first mine in Cleveland opened in Skinningrove.

It was not until August 1850 that Bolckow &

Vaughan made a trial of the Main Seam by quarrying near Eston. Soon the

workings moved underground, using pillar and stall, and became very large scale

with over half a million tons of ironstone was raised annually in the mid 1850s.

John Wharton

died childless and in poverty in 1843 without issue and Skelton passed to his

nephew, John Thomas Wharton of Gilling.

Skelton

Tithes Map 1844

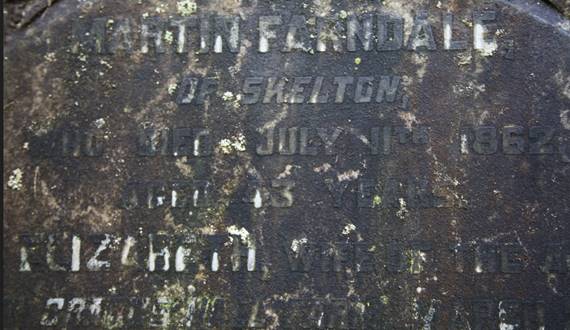

The grave of

Martin Farndale

(1818 to 1862) in Skelton Old Church yard just to the right as you enter the

metal gate.

Skelton

in 1857

In 1859 a

font in Caen stone was given to the church

The opening

of the ironstone mines had

caused a large increase in the population since 1871. The mining villages of Boosbeck and North

Skelton, to the south and southeast of Skelton village, had stations on the North Eastern railway. Lingdale,

further south, was connected by a special line with the Kilton Thorpe branch railway, and Charlton

Terrace or Slapewath (Slaipwath)

had a tramway running from the mines to the North Eastern

railway line which passed it to the north.

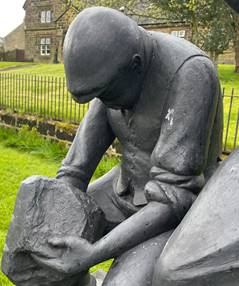

The

management of the Skelton Park pit in the 1880s

Primitive

Methodist chapels and a public elementary school were built in 1881 and

enlarged in 1894.

In 1884 a

new church, also dedicated to All Saints, was opened in High Street. The font

and one of the bells were moved to the new church.

Modern

Skelton

John Thomas

Wharton died in 1900, his heir being his son William Henry Anthony Wharton, who

was Lord of the manor until 1938.

The Victoria

County History – Yorkshire, A History of the County of York North Riding

described Skelton in 1923: The ancient parish of Skelton, including the

townships of Great Moorsholm and Stanghow, covers 11,803 acres, of which 2,219

acres are arable land, 4,657 acres permanent grass and 578 acres woods and

plantations. The soil is clay, with a subsoil of Kimmeridge clay, and the chief

crops grown are wheat, beans, oats and barley. In the north the parish forms a

kind of peninsula between the Skelton and Millholme

Becks, which have very steep banks, whence the land slopes downwards, rising

again towards the centre and also towards the south of

the parish, where there are wide stretches of moorland. The greatest height is

about 975 ft. above ordnance datum. Skelton village itself is situated on the

northern slope. The whole parish is given up to iron-stone mining, to which the

neighbourhood owes its importance.

The older

part of the village is that nearest the castle. Boroughgate

Lane approaches the western end from the south. The newer village stretches

towards the east and is straggling and uneven; in the north-east on high ground

is the new church of All Saints. There are Wesleyan and Primitive Methodist

chapels about the centre of the village, and in the south is the hospital, with

Skelton High Green to the west, and to the east Skelton Green, where there is a

public elementary school built in 1887 and enlarged in 1892 and 1900.

New

Skelton lies to the east of Skelton and has a school.

Further

east is North Skelton, where there is a church mission-room, Primitive

Methodist chapel and a Friends' burial ground. Boosbeck

lies due south of Skelton village; it was constituted an ecclesiastical parish

in 1901 with its church of St. Aidan.

William

Henry Anthony Wharton was High Sheriff of Yorkshire in 1925, and on his death

in 1938, the estate passed to his daughter Margaret Winsome Ringrose Wharton.

She had married Christopher Hildyard Ringrose, a Royal Navy captain, who had

added the additional surname of Wharton to that of Ringrose. She lived there

until at least 1986, by which time her relative, Major Wharton, actually ran the estate on account of her age.

Skelton

in 2016

or

Go Straight to Chapter 12 –

Arrival in Cleveland

Read about Nicholas and Agnes

Farndale and William Farndale

Read about Kirkleatham.

You could

also read a bit more.

The Skelton-in-Cleveland History by

the late Bill Danby, is maintained by the Skelton History Group.

The Cleveland Family History Society is

probably more useful for later periods.

You might

also be interested in John Walker Ord’s History and Antiquities of Cleveland,

1846. You can get a copy from Yorkshire

CD Books.

There is

also the History

of Cleveland Ancient and Modern by Rev J C Atkinson, Vicar of Danby,

1874, to be found in many libraries.

The History

of Cleveland by Rev John Graves, 1808.

The Victoria

History,

1923.

Skelton

Parish Records – Baptisms

– Marriages

– Burials

The webpage

on Skelton includes a chronology and

research notes.