Kirkdale Sundial

A unique treasure whose secrets

reveal an extraordinary insight into the world of the eleventh century upon which

you can stare today, imagining our ancestors who did the same a thousand years

ago

Visiting

Kirkdale

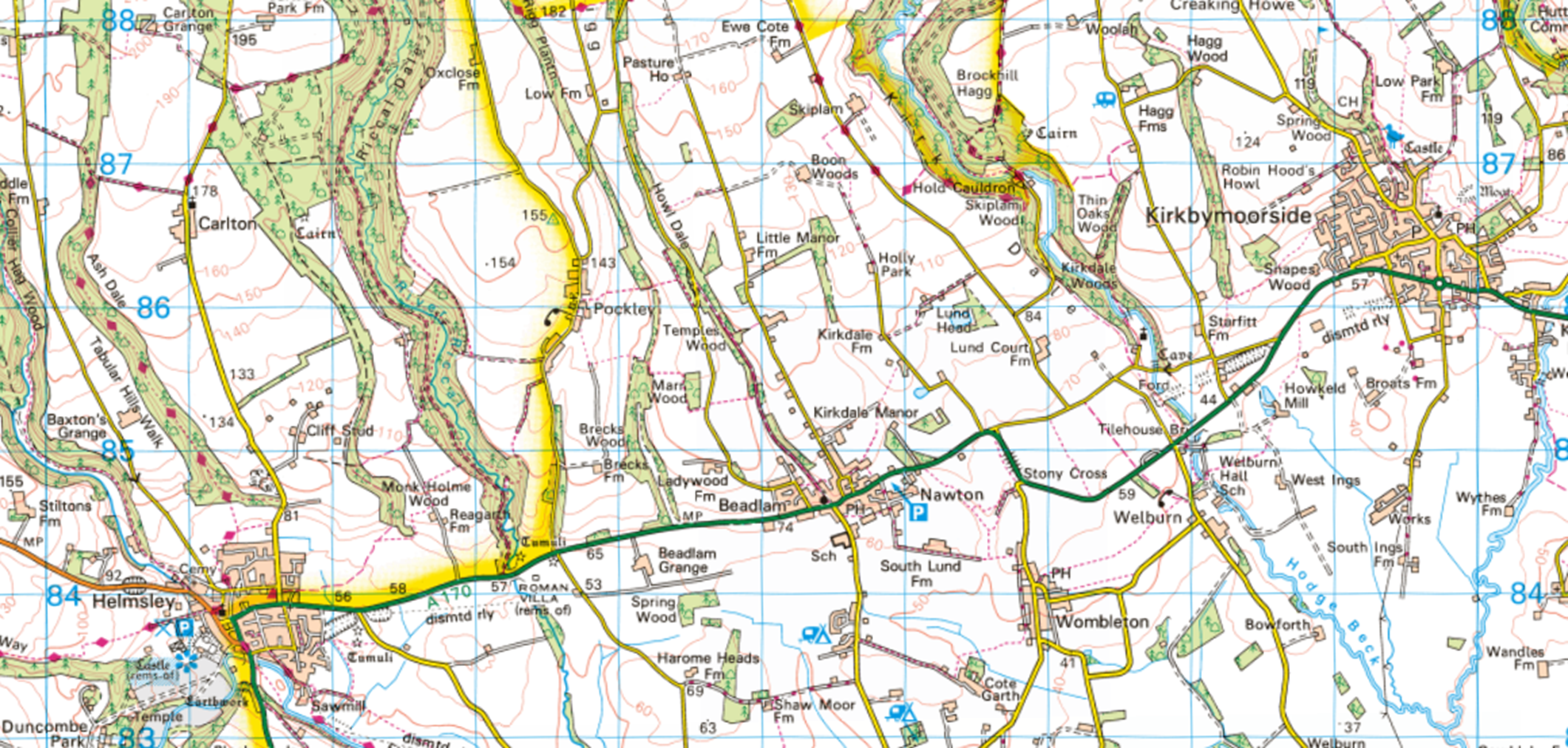

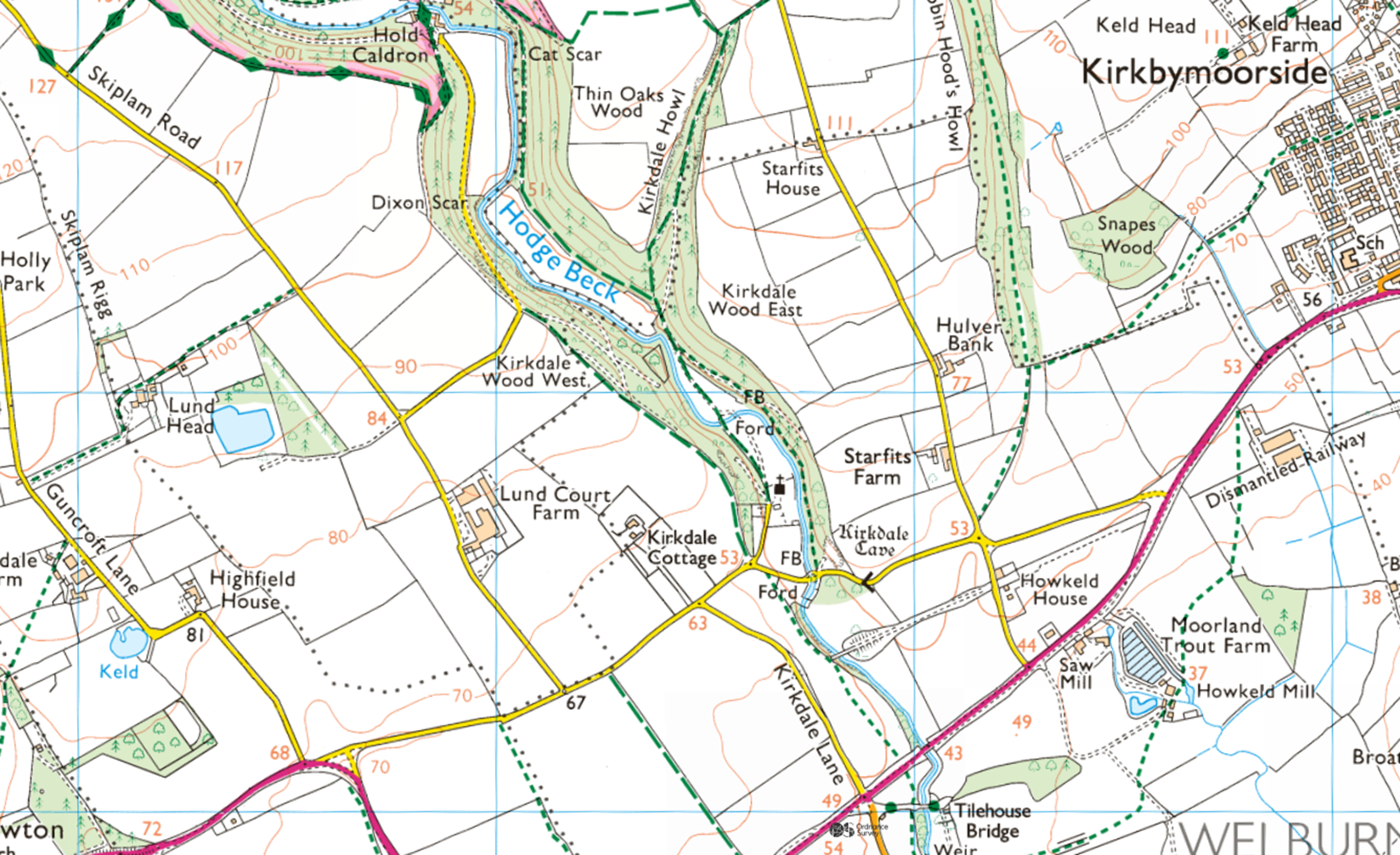

About a mile

west of Kirkbymoorside, south of the North York Moors, you will find a treasure

of the history of our family ancestors and of Ryedale. Head towards Helmsley on

the A170 and at the Welburn junction head north on Kirkdale Lane. Turn right at

the crossroads and you can park in a large carpark beside the minster.

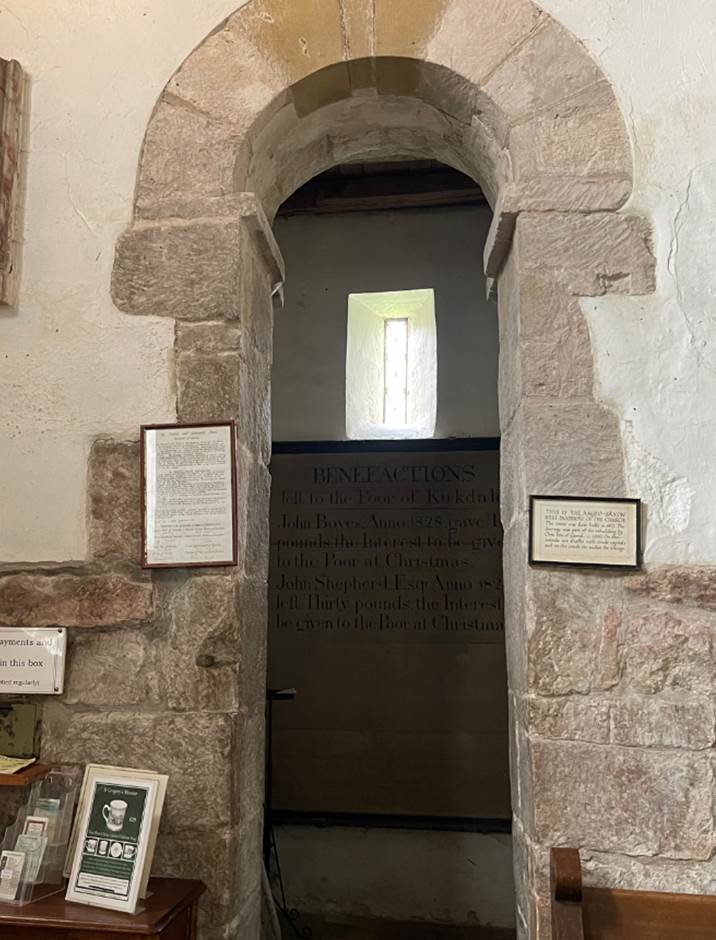

Walk up to

the church and through the metal gate to the porch at the west door which is

now the main entrance to the church. Look up and you will find a Yorkshire

treasure, which will transport you back a thousand years to the decade

immediately before the Norman Conquest in 1066.

The

Sundial

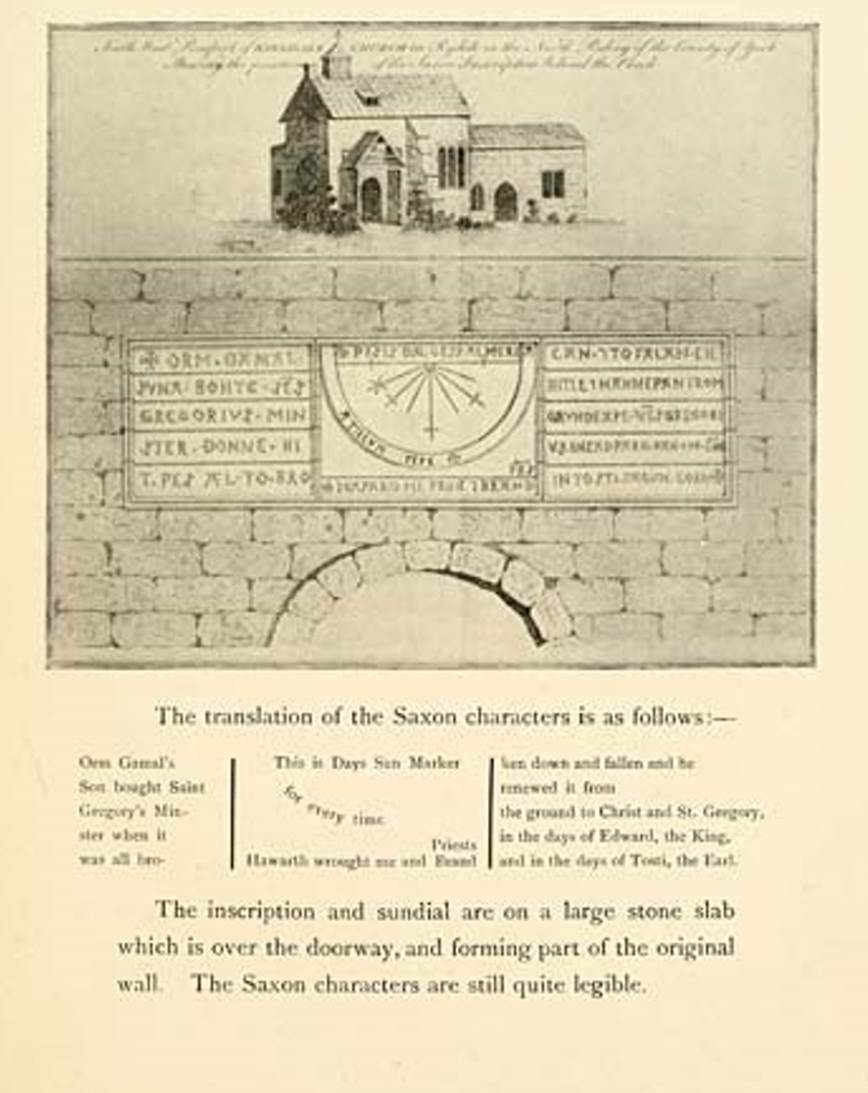

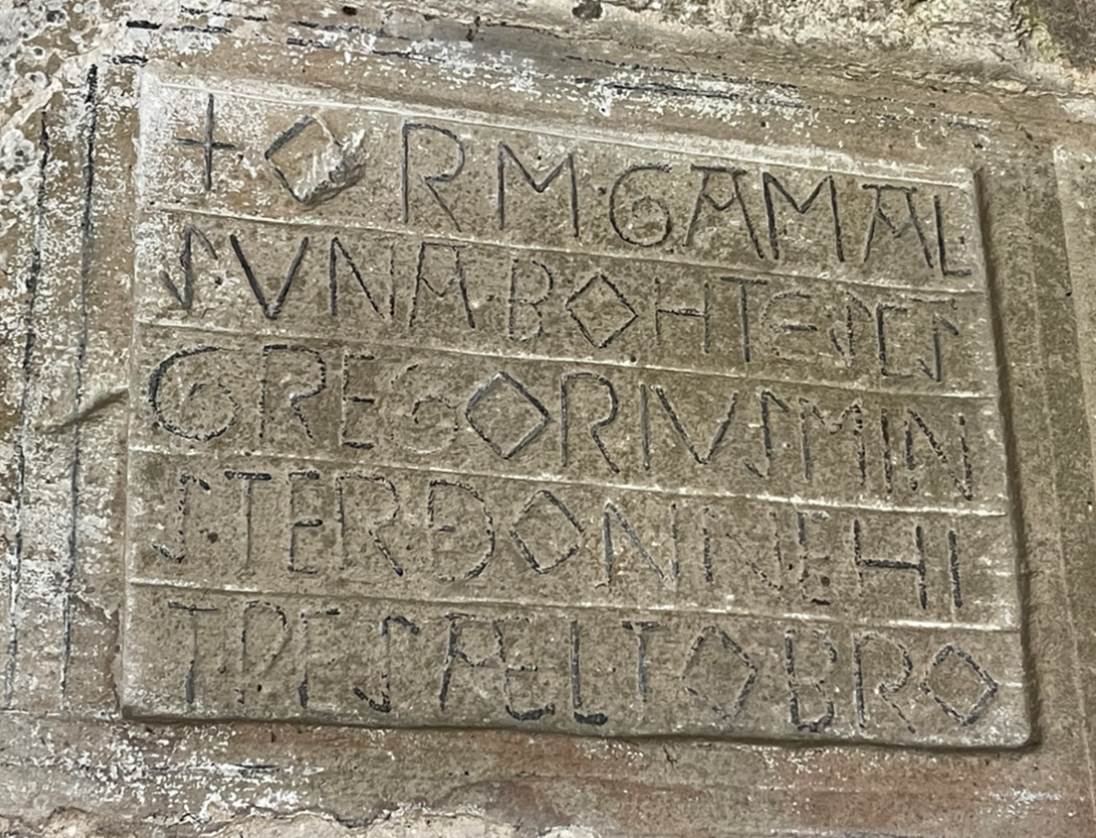

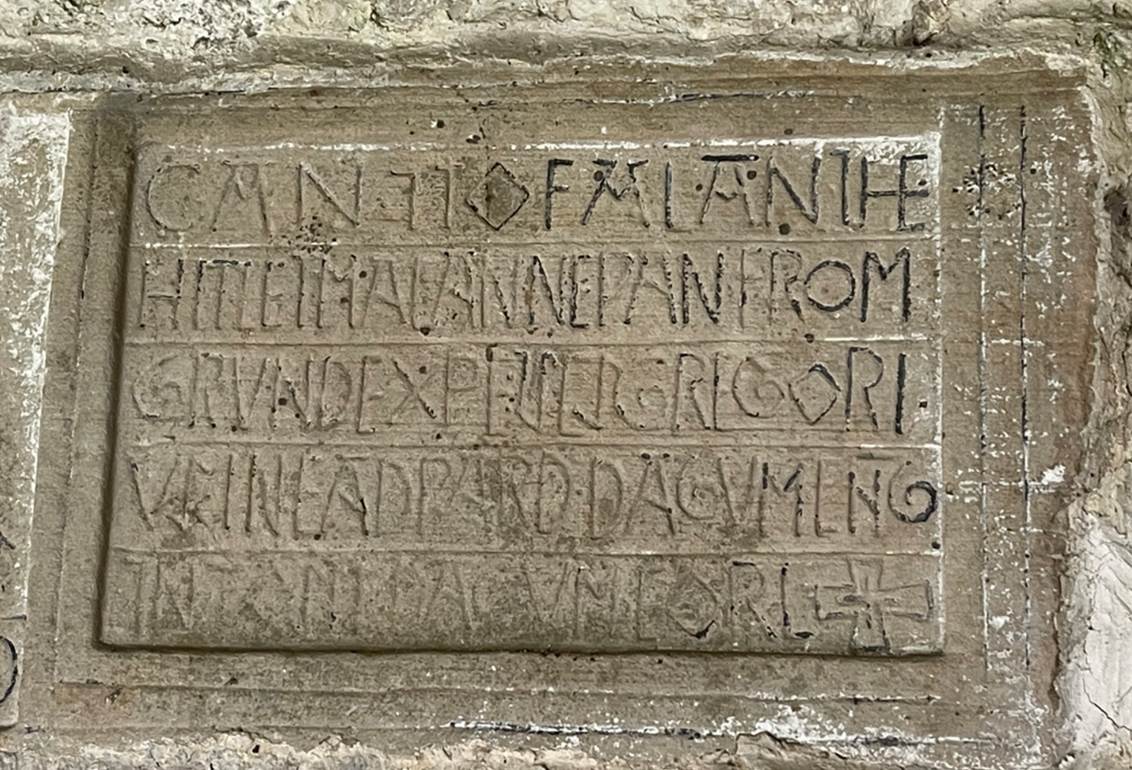

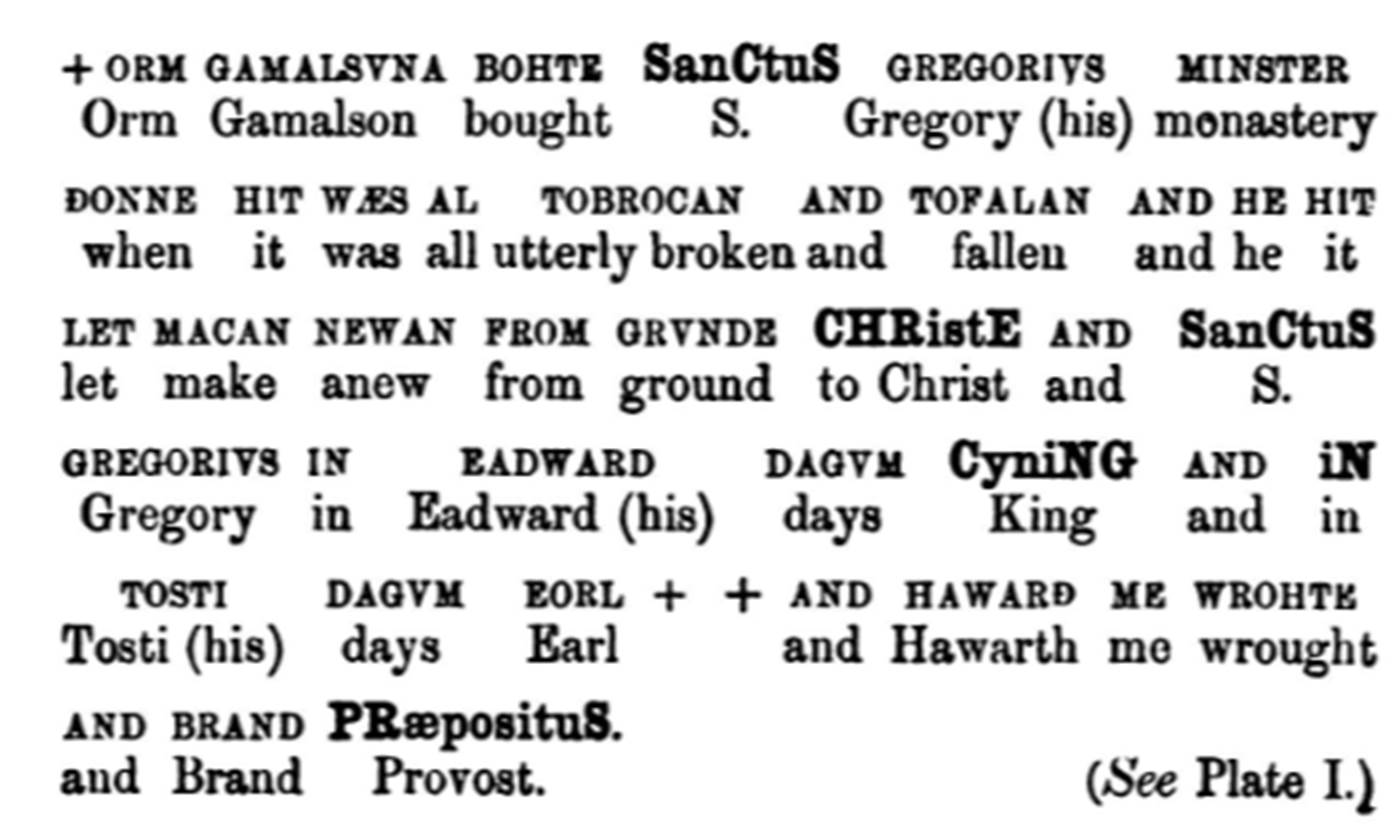

Above the

south doorway within the porch, you will see a sundial from the

Anglo-Saxon-Scandinavian period, which bears the following inscription:

“Orm the

son of Gamal acquired St Gregory’s Minster when it was completely ruined and

collapsed, and he had it built anew from the ground to Christ and to St Gregory

in the days of King Edward and in the days of Earl Tostig”.

The sundial

itself bears the inscription “This is the day’s sun circle at each hour”

and then “The priest and Hawarth me wrought and

Brand”.

As you look

at the sundial, you might glimpse, from the corner of your eye, the shadowy

figure of a direct ancestor who shares the genes we have inherited, also

looking at the same inscription. Give some thought to how that ghostly spirit

might have interpreted the sundial, and what significance might once have been

drawn from it.

The

inscription refers to Edward the Confessor and to Tostig, the son of Earl

Godwin of Wessex and brother of Harold II, the last Anglo Saxon King of

England. Tostig was the Earl of Northumbria between 1055 and 1065. It was

therefore during that last relatively peaceful decade, immediately before the

Norman conquest, that Orm, son of Gamal rebuilt St Gregory’s Church.

The sundial

consists of a stone slab nearly eight feet long (236 cm) by about twenty inches

wide (51 cm), divided into three panels. The central panel contains the dial,

and the Old English inscription above it may be translated as "This is

the day's sun-marker at every hour."

The panels

to left and right contain the further inscription in Old English which

furnishes precious information about the early history of the church.

The

left-hand panel provides the first half of the main inscription: "Orm

the son of Gamal acquired St. Gregory's Minster when it was completely ruined.”

The

right-hand panel completes the information: “and collapsed, and he had it

built anew from the ground to Christ and to St. Gregory, in the days of king

Edward and in the days of earl Tosti."

At the foot

of the central panel a further inscription reads: "Hawarth

made me: and Brand (was) the priest."

Tostig, the

son of Earl Godwin of Wessex and the brother of Harold II the last Anglo-Saxon

king of England, was earl of Northumbria from 1055 to 1065. It was therefore

during that decade that Orm the son

of Gamal rebuilt St. Gregory's church. It is very rarely that we can date the

construction of an early medieval church so precisely.

The sundial

was preserved in a coat of plaster until it was discovered in 1771.

The sundial

was placed over the south doorway, There can be no certainty that the sundial

was built into the new church as it was constructed, but the general dating of

the fabric suggests this was so. It was probably built into the new church at

the time of the rebuilding in about 1055. At that time the main entrance to the

church was the west doorway so another possibility is that it was originally

housed there.

“We cannot be sure that its present position is its

original position … The sundial could even have originally been separate from

the church structure itself; but there is a strong probability, given the

dedicatory nature of the associated inscription … that it always comprised a

prominent display on the face of Orm’s rebuilt church – on the south side of

the building, that is, in order the catch the sun.” (S A J Bradley MA FSA,

Professor Emeritus, University of York).

It is not unlike the seventh century inscription of St

Paul’s Church, Jarrow, which reads In hoc singulari

signo vita redditur mundo, “In this singular symbol, life is restored to

the world”.

The characters of the inscriptions are mostly in the

Latin alphabet. They are in Old English, apart from the conventional Latinate

forms of sanctus (which is abbreviated to

SCS), Christus (christe, abbreviated to

XPE), and Gregorius. Otherwise the wording is of late Old English.

The inscription introduces us to a number of

individuals. Orm is Orm Gamalson,

but his name is not written in its Norse form of Ormr,

but in anglicised form. Tosti is Earl Tostig of Northumbria. Eardward refers to Edward the Confessor. It is likely that Hawarth was the sculptor who undertook the work. Brand was

the priest, perhaps custodian of the science of the computus

which may have lain behind the conception of the sundial.

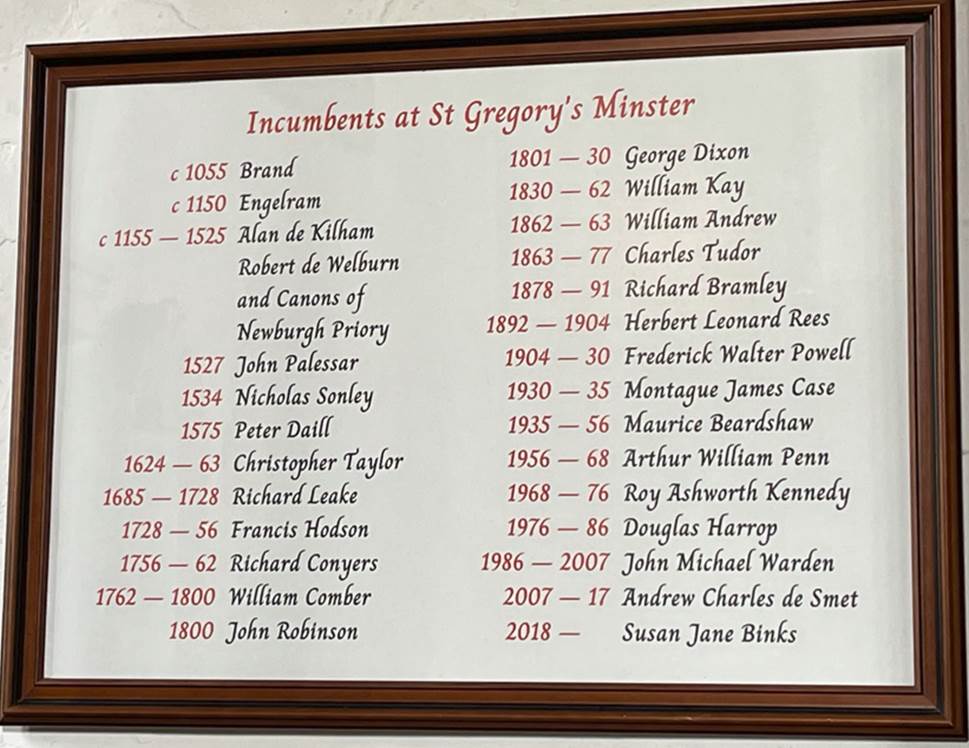

It happens

that there was a Provost Brand, who was elected abbot of Peterborough in 1066.

Perhaps the Kirkdale Priest moved south in the following decade, at the time of

the Conquest.

Kirkdale is

now recognised to have been at the forefront of contemporary English

architecture, with comparisons to St Mary’s Deerhurst and even to Westminster

Abbey, the masterpiece of Edward the Confessor. There may have been

influence from Ealdred Archbishop of York from 1061 to 1069, who had also been

bishop of Worcester and who later crowned William the Conqueror at Westminster

on Christmas Day 1066. Orm Gamalson

held property in York, and may well have been subject to Ealdred’s ideas. It

might have been Ealdred who influenced Orm Gamalson to commission the

inscription. Ealdred was a diplomat, almost a ‘prince bishop’.

The stone

for the rebuilding was from local sources and reused material. If the stone

came from the quarry of North Grimston near Wharram Percy, 27km south east of

Kirkdale, this might have been an asset of Orm Gamal’s family.

Symbolism

had continued in its importance from the Anglo Saxon into the late Scandinavian

period. The sundial itself is a relic of sophisticated allusion, with symbolic

and liturgical meaning. It provides a continuity of experience to the period

when Ryedale was a part of the empire of Rome and Romanitas,

the treasuring of Roman concepts, was important.

The sundial

provides an extraordinary wealth of information conveying Scandinavian, Latin

and English associations. It links to an antique past, Roman, Anglo Saxon and

then Scandinavian.

It is the

first known reference to the dedication of the church to St Gregory, but the

inference is that the church was already dedicated to Gregory. The inscription

reaffirms the importance of Kirkdale’s connections

with Rome.

Earl Tostig,

referred to in the inscription, with Archbishop Ealdred of York, had been on a

pilgrimage to Rome in 1061.

The

inscription is the first surviving reference to the church being a minster, but

it is likely that the church was founded as a minster, though the meaning and

connotations of that definition was likely to have changed over time.

A Short

History of Time

An

interpretation by Professor Bradley of the sundial and its inscription: “This

is the day’s sun circle at each hour”, takes us into the imaginations and

perceptions of our ancestors who conceived of the sundial and looked up at it

as they regularly walked through the door.

Whilst

sundials were already old in England by the mid eleventh century, the Kirkdale

community’s gadgetry for the purpose of telling the time was not particularly

sophisticated. The folk of Kirkdale would have been as well off using such

things as the shadow of hill tops or other features of the landscape as natural

shadow clocks. Professor Bradley therefore suggests that it is highly likely

that the folk of Kirkdale would have used natural features for time telling and

its steep sided valley would have offered good opportunities for such methods.

This might be more consistent with such records as the Prologue to Chaucer’s Canterbury

Tales, in which the narrator was able to calculate that it was foure of the clokke

by a calculation based on his own shadow.

It therefore

seems more likely, particularly given its position over the doorway into the

minster, that the real purpose of the sundial was not practical and secular,

but religious and profound. Indeed the practice was to bury the dead who had

been faithful on the south side of the church, so the exterior of the south

wall was a logical place for such symbolism.

The sundial

has eight divisions. This matches the division of the 24 hour day into eight

sections in the New Testament, with daylight divided into four periods each

corresponding to three hours starting at 6am.

It has therefore

been proposed that the sundial was intended to be a symbolic reminder of

temporal progression or pilgrimage. Time was perceived as the linear temporal

space within which the world moved towards its final judgement and dissolution.

By the

fourth century CE, Christian theology had focused on God’s plans for how life

on earth was lived. This brought with it a conception of history and the

passage of time.

Orm’s

octaval sundial might have been a reminder to those who passed underneath it,

to keep watch of the day and night against Christ’s Second Coming. It might

also have been an incentive to live life as a pilgrimage through time.

The

contemporaneous belief was that people were in temporary exile in the world

from a heavenly home. A symbolic reminder to follow a life of pilgrimage

therefore had a place. This was a subject that later ran through English

literature, such as John Bunyan’s Pilgrim’s Progress. The Seafarer

written in about 1000 CE described the seafarer who, despites the dangers, was

irresistibly drawn to journey onwards over the oceans.

The Kirkdale

sundial might have originally been painted in vibrant colours. It might have

been intended for those who set eyes upon it, to think upon Time. Consciousness

of time was growing through awareness of history. Bede was the national

historian of the English people and Alfred of Wessex had instilled in the

English people an understanding of the need for civilised people to keep

historical records.

The

rebuilding of Kirkdale represents a striking investment of wealth by Orm, which

reflects a revision of the English church of the late tenth and eleventh

centuries. It seems likely that the Scandinavian named Orm Gamalson was

inspired by an awareness of history.

This was an

uneasy generation of the period just after the end of the first millennium. In

1014, Wulfstan, Archbishop of York, had published his sermon addressed to the

English nation. He anticipated the coming of the Antichrist and found moral

decline in the nation. There was always some uncertainty about the exact span

of the thousand years. What was in doubt was the precise date, but not of the

fact of a Second Coming. So it is possible that Orm’s sundial created not so

long after the turn of the millennium, was recording the passing of the last of

days. If that is so, it is difficult to tell whether it was created with a

sense of foreboding, or whether it was a more optimistic symbol.

There was

also an idea that the sun in its daily course was appointed to declare mystical

truths of God’s creation. The sun and moon were understood to mirror God’s

purposes and the destiny of humankind. Perhaps the sundial on the south wall of

the church might have aspired its onlookers to gain some knowledge from the

passage of light as it charted the shadow of a perceived continuum. Orm’s

ornate sundial might have been intended to offer a glimpse into the divine

order of things.

Orm’s

sundial was also likely to have reflected the main thrust of ‘scientific’

consideration, focused on the searching for a knowledge of the Creator and his

universe, and his purposes, through the interpretation of the calendar. This

comprised the calculations of the computes, which had caused such division

within the church until a resolution was reached at the Synod of Whitby in 664 CE.

In 325 CE

the Council of Nicaea ruled that Christians should hold Easter on the same day,

always a Sunday. Its calculation was linked to the Jewish method to determine

the date of the Passover. The computational method involved complex cycles of

years. It never worked well. Bede’s De

temporum ratione was an attempt to help

calculate the dates of Easter up to the millennium and beyond.

There was a

renewal of computus learning in the late tenth

and early eleventh centuries. Aelfric’s

De temporibus anni was a development of

Bede’s earlier work.

With

guidance from texts such as Bede’s and Aelfric’s, it had become possible for a

reasonably educated cleric to make his own calculations. There was likely to

have been a network of ecclesiastical connections, leading to the restored

library at York. Kirkdale’s

likely associations with York would probably have given access to Kirkdale’s priest, Brand, to these works.

So Brand may

have been a priest who, with Orm’s patronage, was able to articulate complex

ideas of the passage of time, reinforcing the correct calculation of time

through computus science, with a primarily

theological symbolism, inspiring our ancestors to use their time wisely and

piously, particularly against the perceived threat of an ending of time.

After the

Conquest in 1074, when Orm had lost his lands, but not so long after the

rebuilding of Kirkdale, the Monastery of St Paul at Jarrow was re-established

in the 1070s by Aldwin, the Benedictine prior of Winchcombe in Gloucestershire,

inspired by reading Bede’s Ecclesiastical History to visit the holy

places of Northumbria. He had been inspired to see whether the Bedean centres

of monastic life were still thriving as recorders of history. Perhaps on his

journey from York he might have found

Kirkdale. If so, Kirkdale might have reassured Aldwin of a local understanding

of theological direction.

So when you

look at the sundial today, it is worth reflecting on what it might have meant

to a person who might be a direct but distant relative. If he or she was

contemplating time, the sundial might now be a portal across a thousand years,

to provide some linkage to our ancestral past.

or

Go Straight to Chapter 3 –

Scandinavian Kirkdale

Go Straight to the History of

Anglo-Saxon-Scandinavian Kirkdale

If your interest is in Kirkdale then I suggest you visit the

following pages of the website.

· The community in Anglo Saxon Times

· The church in Anglo Saxon Times

· The Kirkdale

Anglo Saxon artefacts

· The community in Anglo Saxon Times

· The church in Anglo Saxon

Scandinavian Times

You will find a chronology, together

with source material at the Kirkdale Page.