York 1066 to 1500

A history of York after the Norman

Conquest

There is an

accompanying York chronology, with references

to source material. This page needs more work.

Norman

York

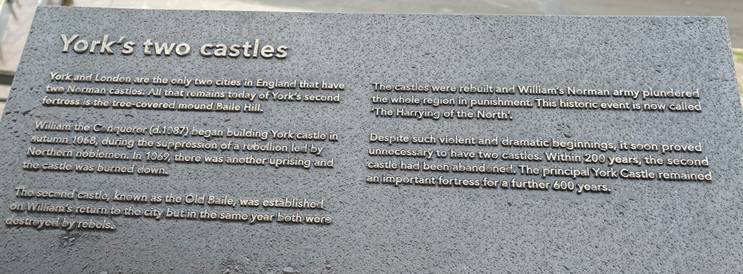

In 1068, two

years after the Norman conquest of England, the people of York rebelled.

Initially they were successful, but upon the arrival of William the Conqueror

the rebellion was put down. William at once built a wooden motte and bailey

fortresses at the site of Clifford’s Tower.

In 1069,

after another rebellion, the king built another timbered castle across the

River Ouse. The original wooden castles were destroyed in 1069 by another

rebellion supported by the Danish King Sweyn II Estridsson.

The Norman

response was to set fires that destroyed swathes of York, including the

Minster. William bribed the Danes to leave, then stamped out local rebellion

during the Harrying of the

North. and rebuilt the City and the two

castles. The remains of the rebuilt

castles, now in stone, are visible on either side of the River Ouse.

The first

stone minster church was badly damaged by fire in the uprising, and the Normans

built a minster on a new site, parts of which can be seen in the modern undercroft. Around the year 1080, Archbishop Thomas started

building the first Norman Cathedral that in time became the current Minster.

Religious

communities emerged, including the hugely wealthy Benedictine monastery of St

Mary’s Abbey, the ruins of which are in gardens of the Yorkshire Museum. The

original church on the site was founded in 1055 and dedicated to Saint Olaf.

After the Norman Conquest the church came into the possession of the

Anglo-Breton magnate Alan Rufus who granted the lands to Abbot Stephen and a

group of monks from Whitby. The abbey church

was refounded in 1088 when the King, William Rufus,

visited York in January or February of that year and gave the monks additional

lands.

Within a few

decades, as many as 40 parish churches stood within the city of York, giving an

indication of its growing population. York once more had become an important,

bustling commercial city.

Plantagenet

York

By the

twelfth century York prospered as a major wool trading centre and became the

capital of the northern ecclesiastical province of the Church of England.

Under the

protection of its sheriff, York had a substantial Jewish community. In 1190,

Clifford’s Tower was the site of an infamous massacre of its Jewish

inhabitants, in which at least 150 Jews died.

The city,

through its location on the River Ouse and its proximity to the Great North

Road, became a major trading centre. King John granted the city's first charter

in 1212, confirming trading rights in England and Europe. The city was no

longer controlled by a sheriff, but headed by a mayor

elected by the citizens.

During the

later Middle Ages, York merchants imported wine from France, cloth, wax,

canvas, and oats from the Low Countries, timber and furs from the Baltic and

exported grain to Gascony and grain and wool to the Low Countries.

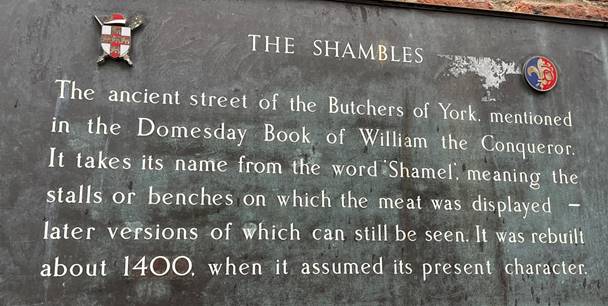

The Shambles

was originally a street for butchers, and the outdoor shelves and hooks on

which meat was hung are still visible.

York became

a major cloth manufacturing and trading centre. Edward I further stimulated the

city's economy by using the city as a base for his war in Scotland.

In 1226 work

started on the construction of York’s town walls.

Royal

government relocated to York during the Scottish Wars.

Clifford’s

Tower housed the royal treasury.

The city was

the location of significant unrest during the so-called Peasants' Revolt in

1381.

The city

acquired an increasing degree of autonomy from central government including the

privileges granted by a charter of Richard II in 1396. The timber-framed

Merchant Adventurers’ Hall, built in the mid fourteenth century, is a remnant

of that era.

During the

fifteenth century the city fathers built a new guildhall and St Williams

College as accommodation for the Minster’s Chantry priests.

York

Minster, the largest Gothic cathedral north of the Alps, was finally completed

in 1472.

However, the

cloth industry, the mainstay of the city’s economy, had gradually moved to

other parts of Yorkshire, Halifax, Wakefield, Leeds, where trade was less

strictly controlled and regulated. The population fell, houses were abandoned.

The city underwent a period of economic decline during Tudor times. Under King

Henry VIII, the Dissolution of the Monasteries saw the end of York's many

monastic houses, including several orders of friars, the hospitals of St

Nicholas and of St Leonard, the largest such institution in the north of

England.

This led to the Pilgrimage of Grace, an

uprising of northern Catholics in Yorkshire and Lincolnshire opposed to

religious reform. Henry VIII restored his authority by establishing the Council

of the North in York in the dissolved St Mary's Abbey. The city became a

trading and service centre during this period. The

reestablishment of the King’s Council in the North, turned York again

into a major administrative and judicial centre.

or

Go Straight to Chapter 9 – The Merchants of York

Or explore: