Eoforwic (York)

The Anglian York Helmet, eighth

century

Deirian and Northumbrian York, a political,

cultural and educational Hub on the European stage

There is an

accompanying York chronology, with references

to source material.

Germanic

invasion

The end of

the Roman imperial period was likely to have seen a dispersal of settlement

into rural areas. It is possible that some centralised government by local

leaders from the old city of Eboracum continued.

The Germanic

invasions may not have impacted on the region of the Vale of York at first and

little is known of the old Roman city in the fifth and sixth centuries.

Cemeteries dating from this period suggest that Germanic people may have

settled in the area as early as the fifth century.

The Middle

Saxon Period in the rest of Britian is generally referred to as the Anglian

Period (600 to 850 CE) in the area around York.

By the first

decade of the seventh century, and perhaps earlier, the old city lay within the

Anglian kingdom of Deira. From about 600

CE, York became capital of the Anglo-Saxon kingdom of Deira. Reclamation of parts of the town was

initiated in the seventh century under King Edwin of Northumbria, and York

became his chief city.

Its

Anglo-Saxon name, Eoforwic, suggests that it was an important

commercial centre. Towns ending in ‘-wic’

were important trading centres. By the early seventh century, it was also a

royal base for the Northumbrian kings.

Christianity

When Gregory

the Great sent Augustine’s mission to convert the Angles, he planned to divide

Britain into two sees, one of which was to have its centre at Eoforwic. His intention was that the Bishop of York,

like Augustine in the southern province centred on London, was to ordain twelve

bishops and enjoy the rank of metropolitan. This apparently sudden reappearance

of Eoforwic in the role of an internationally

recognized metropolis was likely to have reflected its place as a population

and commercial centre. The Roman roads would have continued to focus

Northumbrian communications and commerce to reestablish Eoforwic

as the largest urban settlement in the north. Gregory was no doubt also aware

of the city’s status in Roman times and, in particular, he may have been

reminded by his advisers that the city had been the centre of a bishopric in

the fourth century.

It was here

that King Edwin was baptised in 627 CE. In his Ecclesiastical History, Bede wrote So King Edwin, with all the nobles

of his race and a vast number of the common people, received the faith and

regeneration by holy baptism in the eleventh year of his reign, that is in the

year of our Lord 627 and about 180 years after the coming of the English to

Britain. He was baptised at York on Easter Day, 12 April, in the church of St

Peter the Apostle, which he had hastily built from wood while he was a

catechumen and under instruction before he received baptism. He established an

episcopal see for Paulinus, his instructor and bishop, in the same city.

Paulinus was

established as bishop as the first wooden minster church was built in Eoforwic.

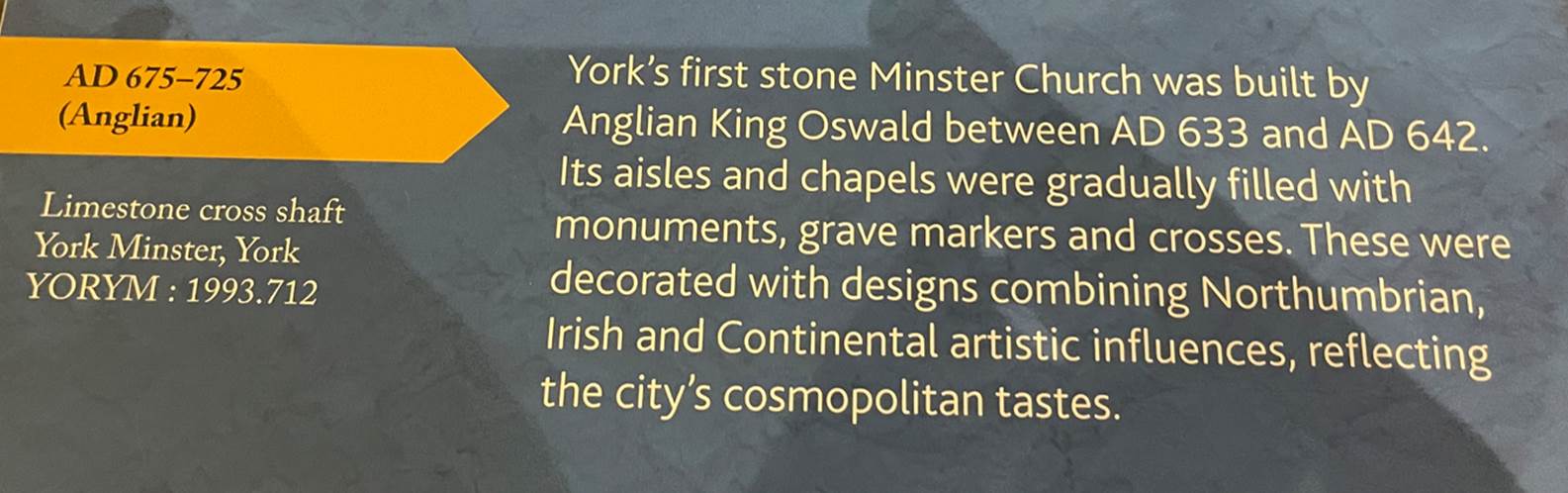

Edwin

ordered the small wooden church be rebuilt in stone. However, he was killed in

633 CE, and the task of completing the stone minster fell to his successor, the

Bernician Oswald. It was dedicated to St Peter. The

original stone church was likely to have been constructed adjacent to the

modern minster in the modern Dean’s Park.

Oswald’s

focus shifted back to the Bernician royal seat at

Bamburgh and he established a new monastic and religious focus on the island of

Lindisfarne. Eoforwic’s fortunes might have

declined once again. However one of Paulinus’ companions, James

the Deacon remained at Eoforwic and the Synod of Whitby called by

Oswald’s successor Oswy in 664 CE established the Roman form of Christianity

and a bishopric was reestablished in Rome, as Gregory had intended.

By 735 CE

the status of Eoforwic was elevated to an archbishopric and

Archbishop Aethelberht (766 to 779 CE) built a new church dedicated to Holy

Wisdom, which might have been part of the wider cathedral complex.

Intellectual

powerhouse

By the end

of the eighth century an extraordinary library and school at Eoforwic continued the more isolated, monastic

intellectual traditions of Bede and

Jarrow-Monkwearmouth. James the Deacon taught music. Wilfred contributed books

to the library. Aethelberht was a prolific collector of books from across

Europe and his pupil Alcuin became master there in 767 CE. Alcuin of York honed his intellect in the

cathedral school. He had a long career as a teacher and scholar, first at the

school at York, and later as Charlemagne's leading advisor on ecclesiastical

and educational affairs.

Alcuin’s

poem On

the Bishops, Kings and Saints of the Church of York provided a description

of eighth century York and a somewhat politically influenced account of its

history.

York,

with its high walls and lofty towers, was first built by Roman hands, that

summoned only the native Britons as comrades and partners in the labour, for at

that time, the Romans, rightly supreme throughout the world, held fertile

Britain in their sway, to be a general seat of commerce by land and sea alike,

both a powerful dominion, secure for its masters, and an ornament to the

empire, a dread bastion against enemy attack …

After the

Roman troops, their empire in turmoil, had withdrawn, intending to rout their

savage foe and to defend Italy, their native realm, the slothful race of

Britons then held sway over York. Overwhelmed by almost unending struggle

against the Picts, finally vanquished, they yielded to burdensome slavery…

Between the

peoples of Germany and the outlying realms there is an ancient race, powerful

in war, of splendid physique, called by the name of the rock because of its

toughness. This people the Britons’ leaders tried to enlist by sending bribes

to protect their fatherland and ward off their foe….

Alcuin went

on to describe Bede’s account of how the indigenous British people paid the

Germanic armies to protect them until the Germanic demands were too steep.

Somewhat dismissively of the indigenous folk, Alcuin went on:

In His

goodness God determined that the wicked race should lose its fathers’ kingdoms

for its wrongdoing and that a more fortunate people should enter its cities …

He then went

on to recount how Edwin, the descendant of ancient kings, a native of York

and future lord of all the land converted to Christianity.

or

Go Straight to Chapter 4 – Anglo

Saxon Kirkdale

Or explore: