Eboracum (York)

The Roman Capital of northern England

where Constantine was proclaimed Emperor

There is an

accompanying York chronology, with references

to source material.

The Eagle

of the Ninth

The Romans

came to Britain, to stay, from 43 CE. Initially the Romans didn’t venture north

of the Humber and Don, but traded with the Parisii and Brigantes.

The area of modern York was part of the lands of a Celtic tribal confederation,

the Brigantes.

Cartimandua

was the Brigantes’ queen. Her position was threatened

by an open revolt by her husband, Venutius. It may

have been this revolt that provided a purpose for Roman intervention.

In 71 CE the

new Roman Governor, Quintius

Petillius Ceralius

marched north from Lincoln to occupy Brigantes

and Parisii territory. The

Ninth Legion, known as Hispana, erected a

large camp at Delgovicia, near where Malton, to the northeast of

York, stands today.

Legionary

Tile, 70 to 120 CE (Yorkshire Museum)

The area of

modern York was an ideal site for a fort in a potentially neutral zone between

the Brigantes and the Parisii.

A larger military camp was therefore constructed by the Romans on an elevated

plateau beside the Ouse, and it became known as Eboracum, the ‘place of

the yews’. The River Ouse provided a navigable route

for supplies through the Humber Estuary. Other rivers such as the Foss and

Derwent were navigable by smaller vessels. The river systems also provided

natural lines of defence. The Romans initially built an earth and timber fort

on the north east side of the Ouse, which formed the

basis for York’s city centre today. Eboracum became the base of some

5,000 legionaries who made up the Ninth Legion.

The

Ninth Legion was at York from 71 CE to about 120 CE. It disappeared from

the records after about 120 CE and the legion was once thought to have been

wiped out in about 108 CE in northern Britian. The story was immortalised in

Rosemary Sutcliff’s 1954 novel, The Eagle of the Ninth.

However later evidence of the Ninth Legion from Nijmegen suggests that the

Legion had a later fate on continental Europe.

Soldiers

stationed in Eboracum came from across northern Europe, though only a

small number came from Italy and very few from Rome itself. The Ninth and later

their replacement the Sixth Legions had been previously stationed in Spain,

Africa, Germany and Pannonia.

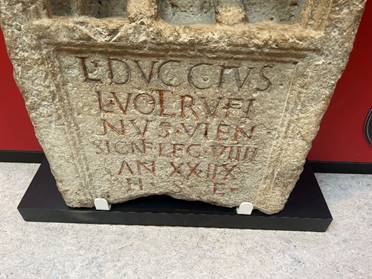

The standard

bearer, Lucius Duccius Rufinus was a 28 year old soldier from Viennes

in France who died in Eboracum.

Lucius Duccius Rufinus, a 28 year old

standard bearer from Viennes, France (Yorkshire

Museum, found in Mickelgate, York)

The

imperial metropolis

As this

fortress grew in importance, a civilian settlement developed on the opposite

bank of the river. The civilian settlement provided

shops and craftsmen and other services.

Urban

settlements grew around the Roman fortifications at Eboracum, Malton and

Stamford.

Roman

coinage (The Yorkshire Museum)

The civilian

settlement was just across a bridge or reached by ferry. Soldiers from the

fortress could relax there and soldiers and officers sometimes lived in

residential properties or large private houses alongside the civilian

population. The early civilian settlement comprised camp followers and the

families of the legionaries. Civilian settlement south west

of the Ouse grew significantly in the mid second century CE. A forum emerged at

its centre and a public bath house. There were likely to have been multiple

temples where cults were celebrated including to the gods of the classical

pantheon as well as deceased emperors. There is evidence of worship of the cult

of the Egyptian goddess Isis, with ideals of rebirth after death. The cult of Mythras was popular in Britain, a Persian sun god, engaged

in a struggle between good and evil. In all Mythraic

temples the god displayed a similar pose slaying a bull from which the blood of

life flowed.

The cult

God Mythras (Yorkshire Museum, from Micklegate)

The

population of civilian Eboracum probably reached about 5,000.

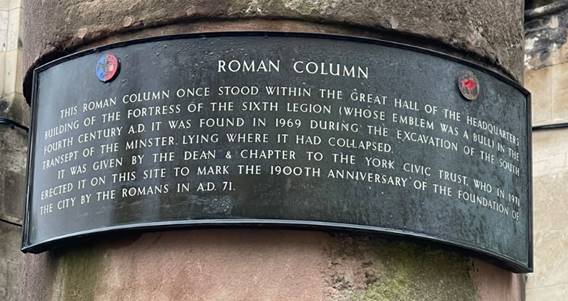

The heart of

the Roman fortress was the principia, the Headquarters. A large

courtyard was surrounded by long buildings on three sides and the larger aisled

hall of the basilica on the fourth. The remains of the Roman Basilica

can be seen in the undercroft of York Minster, and

the remains of a bathhouse in the cellar of the Roman Bath pub. The Roman sewer

lies about 4 metres below Church Street and is of significant scale.

The

principal road

leading to York passed through Lindum (Lincoln) and Danum (Doncaster) to Calcaria (Tadcaster) before turning northeast to Eboracum.

The route then continued north to Isurium Brigantum

(Aldborough) and Cataractonium (Cattrick) and, in time, to the line of Hadrian’s Wall.

Other roads joined Eboracum to Delgovicias

(Malton) and to the coast at Bridlington. The roads provided a swift means for

movement of troops as well as supply routes, supported by the river network for

heavier traffic.

The Vale of

York was richly agricultural and provided cereals and bread to maintain the

army. Supplies were also imported and local craftsman

made pottery and other items in the city.

The Sixth

Legion Victrix

In about 120

CE, Hadrian replaced the Ninth Legion with the Sixth

Legion Victrix (“the Victorious Sixth Legion”), and both the fort and the

civilian settlement were rebuilt in stone.

Emperor

Hadrian (of Spanish origin) visited the settlement during his journey to build

his border wall. Men from York’s Sixth Legion began to build Hadrian’s Wall

from 122 CE. Twenty years later, from 142 CE, they were involved in the

building of the Antonine Wall. Whilst the focus of the Sixth Legion’s activity

was focused in construction of defences to the north

over many decades, by the end of the second century CE, they were back in Eboracum

and began a period of significant reconstruction of the fortress. This included

projecting towers which advanced military technology solutions by allowing

archers to fire along the line of the fortress walls.

Legio VI

was awarded the honorary title of Britannica by Commodus in 184 CE

following his own adoption of that title.

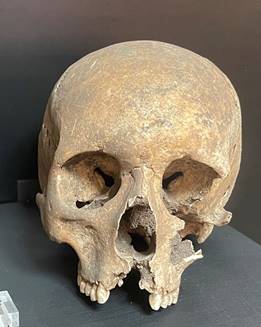

Skull of

a man in his fifties buried between York and Calcaria

(Tadcaster) (Yorkshire Museum).

Skeleton of a wealthy lady found close to the River Ouse, found

accompanied by unusual and expensive objects

(Yorkshire Museum).

Emperors

in Eboracum

During his

stay between 207 CE and 211 CE, the Emperor Septimius Severus (of Libyan

origin) proclaimed York capital of the province of Britannia Inferior,

and it is likely that it was he who granted York the privileges of a 'colonia'

or city. Severus was attended by a very large retinue of civil servants and

soldiers, including the Praetorian Guard. He also brought his wife, Julia

Domna, and their sons Caracalla and Geta. The Emperor Severus was at York while

he was conducting campaigns against the Caledonians. Accounts of his death make

some obscure references to York's topography and mention a temple of Bellona

and a domus palatina. It was at York that

Severus dated a rescript dated 5 May 210 headed Eboraci.

Severus died in York on 4 February 211 CE. He was probably cremated outside Eboracum, but was not buried there but taken to Rome.

Severus’s sons Geta and Caracalla returned to Rome and after a bloody

succession squabble Geta was murdered and Caracalla

became emperor.

Sandstone

statute of Mars 300 to 400 CE (Nunnery Lane, York, now at The Yorkshire

Museum)

Diocletian (284

to 305 CE) reasserted imperial authority and established a new governmental

system known as the Tetrarchy, by which four emperors would govern the western

and eastern empires, one senior (known as Augustus) and one junior (known as

Caesar). Britain had been the subject of a revolt by a Roman naval commander,

Carausius in 285 CE whose successor was defeated in 296 CE by Constantius I who

by then was Caesar in the west.

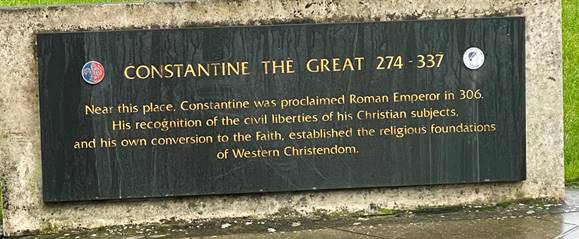

Constantius

I (Constantius Chlorus, of Serbian origin) became the second emperor to die

during his stay in Eboracum on 25 July 306 CE. He was accompanied by his

son Constantine who was proclaimed Emperor by the troops based in the fortress.

Constantine would have a profound impact on the city and on global politics.

Constantius

and Constantine (Yorkshire Museum)

The

veteran soldier Caereslus Augustinus had lost his

wife. Flavia Augustina and his two children. This stone carving (119 to 410 CE)

seems to depict his idea of how they might have grown up as a family, had they

lived. (Yorkshire Museum)

Tombstone

(200 to 300 CE) of Julia Velva. Her heir Aurelius Mercurialis

would gather at the tomb on the anniversary of her death and would have

believed she could take part. (Yorkshire Museum).

Constantine

returned to continental Europe and gradually asserted his authority over his

rivals, emerging as the supreme imperial ruler by 324 CE.

Constantine

I “the Great” supported Christianity, and in 313 CE issued an edict of

religious tolerance. Eboracum had its first bishop, Eborius,

appointed in 314 CE who attended the Council at Arles to represent Christians

from the province that year. By 391 CE Christianity had become so dominant that

Emperor Theodosius banned other religions.

The

increasing centralisation of Eboracum and its demand for supplies of

food was likely to have enriched landowners across the Vales of York and

Pickering. This stimulated the many villas from the area including at Hovingham and Beadlam. The

growth in commerce is evidenced by imported goods such as tableware from Gaul

and beakers and jars from the Rhinelands. The region was

able to export grain and agricultural products as well as jet from the Whitby area.

The Void

The Roman

Empire was under increasing pressure from the mid third century, but Britannia

seems to have avoided the worst of the unrest at first. However inflationary

pressures and disruption of trade must have been felt across the empire. Eboracum

nevertheless remained a provincial capital and military base throughout the

fourth century. However the size of the garrison

appears to have been reduced as the fourth century went on. Britannia was

probably still reasonably peaceful and prosperous until the last twenty years

of the fourth century. By the early fifth century, it was no longer a part of

the empire. This dramatic change must have been devastating to the indigenous

population, experiencing a protected and relatively prosperous lifestyle, which

turned to chaos and threat within a generation. At the turn of the fifth

century, Eboracum was deserted and much of the city abandoned. The

trauma experienced by our ancestors of that period can only be imagined.

While the

Roman colonia and fortress were on high ground, by 400 CE the town was

victim to occasional flooding from the Rivers Ouse and Foss. York declined in

the post-Roman era. The population shrank, trade declined, and buildings were

abandoned.

or

Go Straight to Chapter 5 – Roman Kirkdale

Or explore: