The Known Unknowns

The family history is remarkably

complete. We explore here where it has been necessary to rely on the most

probable narrative where certainty has been impossible

|

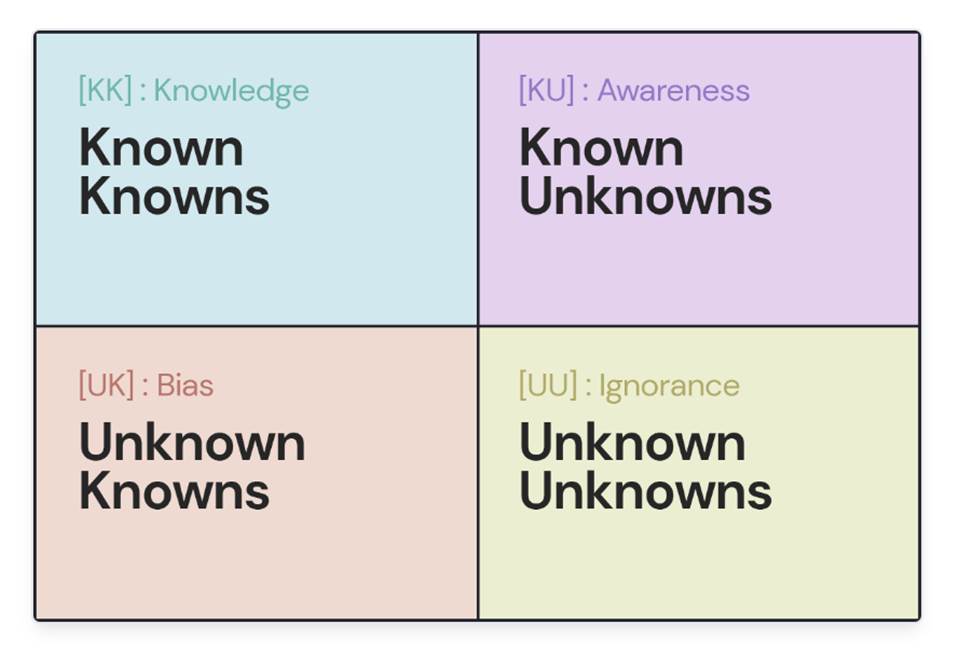

The Observation of Donald Rumsfeld

Recognising

what we know and what we don’t know. |

From

science to story telling

Genealogy

begins as a scientific enterprise. Whilst the first step in a genealogical

journey begins by gathering stories from relatives, it quickly becomes

necessary to build increasingly complicated family trees. The primary tools in

that exercise are records of births, marriages and deaths, made possible by the

start of parish records in the mid sixteenth century, and cross checking these

with census records, which show how families relate together, and where they

lived. Modern search resources, such as those provided by Ancestry

and Find

my Past, mean much of the work can be done from a home computer.

However the

listing of names and how they relate to each other is only a first step. In

themselves, family trees are not very interesting. What is more interesting is

the stories of the individuals who make up those trees. The more interesting research begins when the

family tree is complete, or as complete as it can be, and the time comes to

turn to other records, like military records, medieval records of freemen or

poachers and by turning to newspaper articles, with an exploration of the

history of the places where groups of the family lived.

Rory

Stewart’s 2024 podcast on BBC Sounds, The History of Ignorance,

is a call to combine the scientific approach with imagination and an artistic approach, to

complete the narrative. Genealogy becomes most interesting, and more useful,

when it is a roadmap through history, and a source of inspiration and pattern, building

upon

Standards

of proof

In 2002

Donald Rumsfeld made his well known observation that as we know, there are

known knowns; there are things we know we know. We also know there are known

unknowns; that is to say we know there are some things we do not know. But

there are also unknown unknowns—the ones we don't know we don't know.

It becomes

increasingly obvious in genealogical research that it is possible to find known

facts from written records, but it is inevitable that no genealogist, nor

historian, is able to tell an entire history with certainty.

Parish

records from the sixteenth century allow many families to be assembled to a

near complete family record from that time, though inevitably with gaps where

records no longer exist. From the nineteenth century, census records provide

the additional information which makes the exercise much easier, but census

records are also not always complete. Where there is a record of an individuals

birth, marriage, death or circumstances in a census year, it is possible to be

pretty certain of that fact.

Even before

the sixteenth century, the richness

of medieval sources, means that significant elements of a family story can

be synthesised with perseverance.

Sometimes

the known facts can be glued together with other facts, to build up the matrix

of the family story.

It is

generally impossible to achieve absolute certainty about a family story, but it

is still possible to use intelligence and imagination to fill gaps and to build

up the picture of the whole.

The known

unknowns in the Farndale Story

Generally the Farndale Story and the underlying

details of Family

Lines and individual records, for the period after 1560, is now based on a

pretty solid historical record. Much of the picture for this modern era of the

Farndale history meets the test of known knowns. There are errors and many of

them are recognised, needing more work to steadily make the history more and

more accurate. In a genealogy of this size, there will inevitably be mistakes.

The most

significant known unknown in the story of the modern Farndale impacts on the Ampleforth Line and all those

who descend from it. That large section of the family descend from Elias Farndale

(1733 to 1783) who lived in Thirsk and whose son moved to Yearsley. The trouble is that I have not been able to

find a birth record and can’t therefore put his parentage beyond doubt. My

preferred theory is that he was a son of William Farndale

of the Brotton 1 Line. William

Farndale married Mary Butrick in 1724 and their son, George Farndale was

born in 1725 at Stainton, southwest of Middlesbrough. That would reconcile with

a window between say 1727 to 1735 during which time Elias might have been born

to that family. Weighing up the facts that are available, that seems to be the

most probable explanation. The analysis might need to change in time, or it

might be correct.

I have similarly

pooled the historical evidence concerning Nicholas

Farndale and Agnes

Farndale, and their children William Farndale

and Jean

Farndale, to explain the most probable course of events that led our family

who seems to have been living around Campsall north of Doncaster in 1564, but

probably moved north to Cleveland shortly afterwards. There is also still some

uncertainty that George

Farndale, through whom the line then descends, was William and Margaret’s

son. If I am correct then all modern Farndales descend through a common

ancestor in George and Margery, and then back through William and Margaret, and

then Nicholas and Agnes, back to the Farndales of Campsall and Doncaster. This

analysis is based on a probable interpretation of the evidence, but it could be

wrong. More evidence might still come to light to cause an adjustment to this

narrative.

The

narrative of the family story before the sixteenth century is necessarily based

on the most probable interpretation of evidence. From a significant weight of

medieval evidence which is available, I have compiled the earliest family tree of

the family. It is inevitable that it will contain errors. Yet the exercise is

helpful because it provides a likely narrative for the family story. The facts

upon which the family tree is based are known knowns, based on historical evidence.

It is very likely that the early family tree provides a relatively good picture

of how these known stories, and the individuals who were their actors, relate

to each other and to the modern family.

Before the

thirteenth century, it is impossible to identify individual people who might

have been our ancestors. Yet the relationship of the place where they first

adopted the name to an estate which was an area of stability and agriculture

back to Roman times, means that by telling the story of the place, we are

almost certainty continuing our family story.

We start

with known knows, and as we pass back through history, it is inevitable that we

encounter the unknown. That does not prevent the story from continuing, but it

means that there are more gaps to tell, in weaving together the family story.