|

|

The Church

The evolution of the Church as it impacted on northern England

|

|

Headlines are in brown.

Dates are in red.

Hyperlinks to other pages are in dark blue.

References and citations are in turquoise.

Context and local history are in purple.

Geographical context is in green.

See also the

Farndales and religion.

563 CE

The Hiberno-Scottish mission was a

series of expeditions in the 6th and 7th centuries by Gaelic missionaries

originating from Ireland that spread Celtic Christianity in Scotland, Wales,

England and Merovingian France. Celtic Christianity spread first within

Ireland. Since the 8th and 9th centuries, these early missions were called 'Celtic Christianity'.

Columba was an Irish prince born in 521

and educated at the Bible school at Clonard. At the age of 25, Columba’s first

mission involved the establishment of a school at Derry. Following this,

Columba spent seven years allegedly establishing over 300 churches and church

schools.

In 563, Columba came to Iona from

Ireland with twelve companions, and founded a monastery. It developed as an

influential centre for the spread of Christianity among the Picts and Scots.

580 CE

The historian Procopius

(500 to 565 CE) described the people of Brittia

as Angiloi to Pope Gregory the Great, Gregory

had seen fair haired slaves for sale and replied that they were not Angles,

but angels. His pun is sometimes taken to define the origin of the English

and Gregory continued to class them as a single peoples.

Hence there grew a single

and distinct English church. It adopted Roman practices in its dogma and

liturgy (as later confirmed at the Synod of Whitby in 663 CE), but it venerated

English saints and developed its own character.

597 CE

Pope Gregory sent

Augustine, prior of a Roman monastery to Kent on an ambassadorial and religious

mission to convert the Angli, and he was welcomed by

King Aethelberht.

The English church would

come to own a quarter of cultivated land in England and it brought back

literacy. English identity began in a religious concept.

627 CE

Edwin converted to the

Christian religion, along with his nobles and many of his subjects, in 627 and

was baptised at Eoforwic. Edwin built the first church at Eoforwic (York) amidst the Roman ruins and it was

later replaced by a larger stone church.

Stone

crosses or spelhowes/spel crosses started to appear in the landscape, which seem to have been

meeting places of early local government. There is a story that Kirkdale church

was first built on the site of such a stone cross.

634 CE

Edwin's successor, Oswald, was sympathetic to the Celtic church and around 634

he invited Aidan from Iona to found a monastery at Lindisfarne as a base for

converting Northumbria to Celtic Christianity.

Aidan soon established a

monastery on the cliffs above Whitby

with Hilda as abbess.

Further monastic sites were established at Hackness

and Lastingham and Celtic Christianity became more

influential in Northumbria than the Roman system.

There is a traditional

story that a monastery was built at Oswaldkirk in

Ryedale, but was never finished.

659 CE

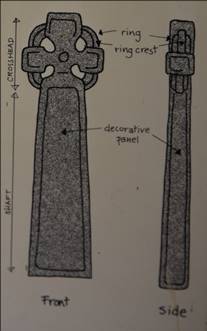

Christianity in Ryedale and the stone

crosses of the Ryedale School

Many local churches in Ryedale date back

to the Anglo-Saxon period. The churches are not the earliest evidence of the

arrival of Christianity to the north of England. The first evidence was the

establishment of a chain of monastic sites from Lindisfarne down the coast to Whitby, their influence then extending

inland to Crayke, Lastingham

and Hackness. The Venerable Bede recorded that in 659

CE the monk Cedd hallowed an inauspicious site at Lastingham

and established there the religious observances of Lindisfarne where he had

been brought up. By the time Bede was writing in circa 730 CE, there was a

stone church at Lastingham.

Christianity was spread through the work

of missionaries who travelled the countryside, often erecting preaching

crosses. They were originally made of wood, but with the re

introduction of building in stone, stone crosses became the norm. These

preaching crosses depicted scenes from the Bible and were often elaborately

decorated with motifs from the Mediterranean. The carvings may have originally

been painted in bright colours. In the central part of Ryedale there were local

Craftsman who produced such crosses which were unique in their design. A

typical Ryedale School cross was about 6 feet tall with a slightly tapering,

flat, oblong section shaft. The style occurs in Kirkbymoorside, Levisham and Middleton. The Ryedale dragon is an

ornamentation on the back panel of the cross shaft. A single beast, often in an

S shape, filled the whole panel.

Yet Yorkshire folklore remains rooted in

Anglian and Norse paganism including tales of the erection of Freeborough Hill by the devil and of hobs. Dragons hunted in Cleveland,

with tales in Loftus.

663 CE

The competing influences

of the Roman Church and the Celtic Christianity originating from Iona caused

conflict within the church until the issue was resolved at the Synod of Whitby

in 663 by Oswiu of Northumbria opting to adopt the Roman system.

The schism had come about

because the church in the south were tied to Rome, but the northern church had

become increasingly influenced by the doctrines from Iona. The Synod was held

in the monastery at Streoneschalch near to Whitby.

665 CE

Cuthbert of Lindisfarne

(c. 634 – 20 March 687) was an Anglo-Saxon saint of the early

Northumbrian church in the Celtic tradition. He was a monk, bishop and hermit,

associated with the monasteries of Melrose and Lindisfarne in the Kingdom of

Northumbria, today in north-eastern England and south-eastern Scotland. Both

during his life and after his death, he became a popular medieval saint of

Northern England, with a cult centred on his tomb at Durham Cathedral. Cuthbert

is regarded as the patron saint of Northumbria.

Cuthbert grew up in or

around Lauderdale, near Old Melrose Abbey, a daughter-house of Lindisfarne,

today in Scotland. He decided to become a monk after seeing a vision on the

night in 651 that Aidan, the founder of Lindisfarne, died, but he seems to have

experienced some period of military service beforehand. He was made

guest-master at the new monastery at Ripon, soon after 655, but had to return

with Eata of Hexham to Melrose when Wilfrid was given the monastery instead.

About 662 he was made Prior at Melrose, and around 665 went as Prior to

Lindisfarne. In 684 he was made bishop of Lindisfarne, but by late 686 he

resigned and returned to his hermitage as he felt he was about to die. He was

probably in his early 50s.

685 CE

By about 685 CE, the early

church at Kirkdale was dedicated to St Gregory. There are two elegant tomb

stones within its grounds which are once said to have borne the name of King Oethelwald. More recent excavations tend to suggest that

the church at Kirkdale was important.

The origin of parish

churches emerged at about this time. A parish was a district that supported a

church by payment of tithes in return for spiritual services. Some churches

were linked to manor houses and others originated as the districts of missioning

monasteries. The church at Whitby was near a major settlement, whilst the

church of St Gregory’s at Kirkdale was located remotely in a dale. By 1145,

Kirkdale was described as the church of Welburn.

Pope Gregory had

encouraged the conversion of pagan holy places to Christianity and the church

at Kirkbymoorside is near a large burial mound.

731 CE

The Venerable Bede (672 or

673 to 26 May 735) (“Saint Bede”) was

an English monk and an author and scholar who wrote the Ecclesiastical History

of the English People which he completed in about 731 CE. He was one of the

greatest teachers and writers during the Early Middle Ages, and is sometimes

called "The Father of English History". He

served at the monastery of St Peter and its companion monastery of St Paul at

Monkwearmouth and Jarrow in the Anglian Kingdom of Northumbria.

The Life of

the Venerable Bede, on the state of Britain in the seventh century,

begins: In the seventh century of the Christian era, seven Saxon kingdoms

had for some time existed in Britain. Northumbria or Northumberland, the

largest of these, consisted of the two districts Deira and Bernicia, which had

recently been united by Oswald King of Bernicia ... The place of his birth is

said by Bede himself to have been in the territory afterwards belonging to the

twin monasteries of Saint Peter and Saint Paul at Weremouth

and Jarrow. The whole of this district, lying along the coast near the mouths

of the rivers Tyne and Weir, was granted to Abbot Benedict by King Egfrid two

years after the birth of the Bede.... Britain, which some writers have called

another world, because from its lying at a distance it has been overlooked by

most geographers, contained in its remotest parts a place on the borders of

Scotland, where Bede was born and educated. The whole country was formed

formerly studded with monasteries, and beautiful cities founded therein by the

Romans, but now, owing to the devastations of the Danes and Normans, has

nothing to allure the senses. Through it runs the Were, a river of no mean

width, and of tolerable rapidity. It flows into the sea and receives ships,

which are driven thither by the wind, into its tranquil bosom. A certain Benedict

built churches on its banks, and founded there two monasteries, named after St

Peter and St Paul, and united together by the same rule and bond of brotherly

love.

Bede gave intellectual and religious

significance to as burgeoning nation at Jarrow from where many centuries later John

William Farndale was the youngest member of the Jarrow marchers. Bede first

defined an English identity. Bede produced the greatest volume and quantity of

writing in the western world of his time. At his monastery at Jarrow he had

access to a university library with more books than were in the libraries of

Oxford or Cambridge 700 years later. (Robert Tombs,

The English and their History, 2023, 24, 26).

871 CE

Alfred

the Great (871 to 899 CE) has been

remembered in history as educated and practical, a Christian philosopher king.

959 CE

There was an English

church and English saints.

1009

This was the time of Archbishop Wulfstan

was very involved in the reform of the English church, and was concerned with

improving both the quality of Christian faith and the quality of ecclesiastical

administration in his dioceses (especially York, a relatively impoverished

diocese at this time). He urged the casting out of heathen practices,

witchcraft and idols. He wanted to see the observation of Sundays.

There was some revival of the Church in

the later Scandinavian period and this may have been a time of some church

building, especially in places called Kirkby.

1030

The Horn of

Ulph is an eleventh-century oliphant (a horn carved from an

elephant's tusk). It is two feet four inches long, and has a diameter at the

mouth of five inches. Given its size and condition, it is a particularly good

example of a medieval oliphant. Tradition holds that it is a horn of tenure,

presented to York Minster by a Norse nobleman named Ulph sometime around 1030.

This suggests that a powerful Scandinavian nobleman was willing to donate a

very valuable object to the Christian church by this time.

1053

It is not clear how strongly held

Christian belief were at a local level. Many pagan customs continued. The days

Tuesday through to Friday are still named after Anglian and Norse Gods. Hills

remained dedicated to the Norse Gods Odin and Woden,

Much Yorkshire folklore remains rooted in Anglian and Norse traditions. Hobs

and boggles remained in field names. However masonry at churches evidences

Christian assimilation. The settlement at Chirchebi that would be the

burgeoning lands of Kirkbymoorside was a small rural community focused around

the church of St Gregory and its priest. The eleventh century sundial at

Kirkdale is the best preserved of several including others at Edstone and Old Byland.

1078

A mission arrived from Evesham Abbey

Mercia in York, were joined by Stephen of York and established a Benedictine

monastery in the old ruins at Whitby. Some

of the monks went to Lastingham and they partly build

a large church there.

The monks led by Stephen of York built

St Mary’s Abbey from 1088 to 1089.

1100

After the

Norman Conquest, the church remained a powerful force.

The Normans reorganised the local

church. Many parish churches were rebuilt in stone.

The Rectors received regular tithe

incomes, a tenth of any increase of crops or stock within the whole parish

area.

Oral teaching was mainly in English (in

order to converse with the indigenous population), but they wrote in Latin and

Franch (with some English). Some English religious and cultural traditions

continued.

1128

First Cistercian abbey at

Waverley.

Monastic orders, such as Rievaulx

in 1128 arrived in England. They became important agricultural communities and

sometimes were involved in iron and coal mining.

Some chose different routes to their

religious goals and hermits started to

appear in the records, often the first known residents of more remote places,

such as Edmund the Hermit of Farndale.

Cuthbert had retired in 676, and moved

to a more contemplative life. With his abbot's leave, he moved to a spot which

Archbishop Eyre identifies with St Cuthbert's Island near Lindisfarne, but

which Raine thinks was near Holburn, at a place now

known as St Cuthbert's Cave. Shortly afterwards, Cuthbert moved to Inner Farne island, two miles from Bamburgh, off the coast of

Northumberland, where he gave himself up to a life of great austerity. At first

he received visitors, but later he confined himself to his cell and opened his

window only to give his blessing. However he could not refuse an interview with

the holy abbess and royal virgin Elfleda, the daughter of Oswiu of Northumbria,

who succeeded St Hilda as abbess of Whitby in 680. The meeting was held on

Coquet Island, further south off the Northumberland coast.

This was an age of giving to religious

orders and the barons had vast empty lands which they could easily donate. This

was a form of insurance policy and generally gifts of land were rewarded by

monks’ prayers to help the passage of the nobility into the after

life.

·

Robert

de Brus gave most of his lands at Guisborough to form a

priory in about 1119 to 1124.

·

Walter

Espec founded Kirkham Priory in 1121 to 1122.

1131

Walter Espec encouraged the founding of the

Cistercian abbey at Rievaulx in 1131. These austere monks sought

detachment from the world, in contrast to the Benedictines and the

Augustinians.

A

breakaway group from St Mary’s Abbey in York established Fountains Abbey and

Kirkham Priory.

Monastic Farming

The

Cistercian way of life was simple. The Cistercian abbots accepted donations of

land but generally avoided settled areas, or cleared them (as at Hoveton and Welburn near Kirkbymoorside).

Significant land grants were given to

the monasteries. Rievaulx soon had a great swathe of properties,

throughout Ryedale and stretching to Teesmouth and Filey. At its peak it had 140 monks and 400 lay brothers.

They tended to site their granges away from villages. Monastic farms were a

separate economic force. The sheep grange was dominant in Yorkshire with many

examples, including at Farndale, of donations of rights to pasture a fixed

number of sheep.

Nunneries

The Cistercians

opposed the establishment of religious houses for women until the early

thirteenth century.

Robert de

Stuteville gave a tract of land to the east of Kirkbymoorside for the

establishment of a nunnery at Keldholme Priory.

1200

By 1200 the organisational structure of

the church had been established:

·

The

provinces of Canterbury (primacy established by 1353) and York;

·

9,500

parishes

The parish had existed before the Norman

Conquest. Parishes had their own guilds and associations and provided social

cohesion through feats and charitable affairs. Church wardens were elected from

the thirteenth century.

The Church, perhaps along with

professional lawyers, was an avenue for a person to rise to wealth within a

generation.

1220s

The preaching orders of

friars arrived, including

the Franciscans or Greyfriars and Dominicans or Blackfriars. Towns

started to see a growth of religious houses.

1221

Dominicans (black friars) began to

arrive in England.

There is an In Our Time podcast on the religious orders of the

Dominicans and the Franciscans, the Blackfriars and Greyfriars,

who were a great force for change in Catholic Europe.

1224

Franciscans (grey friars) began to

arrive in England.

1300

By the fourteenth century, the Church

remained the second most powerful institution.

Tithes were an important part of church

revenue. Local priests gained a secure living with a definite income and

sometimes even a pension. Some clergymen became wealthy. The vicar of

Kirkbymoorside was able to go on pilgrimage to Compostella in Spain.

An important role of vicars was moral

leadership. There was a focus on the Seven Deadly Sins. Even the nobility were

not exempt from reprimand. Occasionally criminals might find sanctuary in

churches. The church became a focus of regular patterns of local life and

important events such as baptisms, marryings, the

churching of women, and funerals, were administered by the church.

1400

John Wycliffe was an

Oxford theologian who, with his followers, nicknamed the

Lollards, or the mumblers, translated the

Bible, seeing this as a return to the traditions of Bede. It coincided with a

wish by lay people to become more actively invested in religious life.

There was however concern about the use

of English, no longer seen as ‘angelic’, accentuated by attempts to translate

wine as cider.

In 1401, heresy was made a capital

offence.

The Constitutions of Oxford

1408 started an unprecedented period of the policing of belief. The

translation of the Bible into English was forbidden.

(Robert Tombs, The English and their History, 2023,

130).

1450s

The discipline of philology (the study

of words, especially the history and development of the words in a particular

language or group of languages.) led to a rejection of ideas deriving from the

fourth century Doctrine of Constantine.

Besides natural colour, life was

monotone, except in the churches where painted walls and cloth added colour to

drab worlds. The wall

paintings at Pickering Church shared

stories of religious belief in the fifteenth century.

By this time, there was a trend away

from donations to monasteries towards abstinence and piety and less worldly

involvement.

However saints and their shrines

remained powerful talisman. For instance a girl from Ampleforth contracted

marriage before the tomb of St William of York.

The priest was expected to teach the creed,

then ten commandments, the seven deadly sins, the sacraments, the lord’s

prayer.

(Robert

Tombs, The English and their History, 2023, 144, 145).

1466

Printing from the 1430s and cheaper

paper gave opportunities for a wide distribution of new forms of the Bible.

Printed Bibles appeared in German (1466), Italian, Dutch, French, Spanish,

Czech in the 1470s.

1509

The European context in 1509 was

challenging:

·

Geopolitical

crises were tearing Europe apart

·

Western

civilisation was challenged

·

Portends

of the end of the world were rife

·

After

the capture of Constantinople, Muslim forces were threatening Europe

·

1494 – War

between France and the Hapsburg Holy Roman Empire

·

1495 -

Savonarola, a Dominican friar, established a theocratic dictatorship in

Florence

·

1527 – Rome

was sacked by the Hapsburgs

·

1530 to 1527 – Muslim raiders took a million Europeans

into slavery

·

1618 to 1648 – the Thirty Years War

In this context there grew a new

interest in Greek and Roman antiquity, and classical styles of literature.

This was taught by the umanisti, the humanists, who started to mock

tradition religious teaching. Humanists included:

·

John

Colet, Dean of St Pauls

·

Thomas

More, lawyer

There is an In

Our Time podcast on Humanism.

Traditional religious teaching was

marked by ceremony, ritual, pilgrimage and indulgences (the remission of

punishment of sin by payment of cash donations to the church).

In England anti Lollard legislation

hampered challenges to traditional medieval Christianity. However there was a

new desire to focus on what God said, rather than rely on traditional

interpretations of what God meant. There was increasing intellectual scepticism.

1516

Erasmus of Rotterdam produced a Greek

New Testament in Latin with changes in wording.

1517

Martin Luther, an Augustinian friar, openly

challenged the established church and its practice of indulgences, and nailed

his critique of the religious authorities to a church door in Wittenburg.

The established church came to be

criticised as hopeless, itself blasphemous, and ruled by corruption.

Luther’s idea initially appealed to

educated folk in German and Swiss towns. The nobility took to his ideas as a

challenge to their natural rivals in the Church.

Soon statues were smashed in churches.

1524

The Peasants’

War swept across Europe.

1526

William Tyndale, an Oxford scholar printed copies of

his English translation of the New Testament from Greek from his base in

Cologne. 16,000 copies were smuggled into England.

1527

After failed attempts to negotiate with

the Pope regarding his marriage to Catherine of Aragon, Henry began to question

whether the Pope had the authority to interpret God’s law and whether he was

superior to a Christian King. These were the underlying issues debated in the

1520s and 1530s.

1529

Henry dismissed Wolsey and confiscated

his property, including Hampton Court.

1530s

In the 1530s fierce debates raged

regarding the positions of the sun and the earth. The discovery of the Americas

from 1492 led to a discovery of new worlds. This all led to a re-examination of

traditionally held beliefs.

1533

Henry appointed Thomas Cranmer as

Archbishop of Canterbury.

There followed a succession of

parliamentary acts to remove the English church from papal jurisdiction.

The Act

in Restraint of Appeals 1533 ended legal recourse to Rome. England was

declared an empire.

1534

The Reformation

The First

Act of Succession 1534 declared Catherine’s marriage ended and conferred

the succession on Anne’s issue.

Two Acts of Supremacy

confirmed that Henry was the only supreme head of the Church of England, under

pain of treason. Every man in the Kingdom was required to take an oath to

accept the new law.

This was a sudden and dramatic change in

the affairs of the Church.

To most ordinary folk, these issues were

remote and caused little issue.

Henry’s own religious doctrine remained

conservative. He insisted on the transubstantiation (the conversion of the body

and blood of Christ into bread and wine). He felt that salvation came from good

work. He was inclined to a degree of moderation in his views of the established

church.

1535

Tyndale was tracked down to Antwerp and

burned for heresy.

However from 1835, Henry, wishing to

prevent the likes of More and Fisher becoming modern Thomas a Beckets, had the

shrine of Becket destroyed and a process started of visitations and stocktaking

of religious houses.

Commissioners

were appointed to assess the wealth of churches. One commissioner, Thomas

Layton wrote of ‘great corruption among religious persons’ in Yorkshire.

The commissioners sacked Prior Cockerill of Guisborough.

(John Rushton, The History of Ryedale, 2003,

167).

1536

The Dissolution of the monasteries 1536

to 1539.

Rievaulx

Abbey had 27 buildings in two courtyards, as fulling mill, iron smithy, corn

mill, tannery, houses for craftsmen.

The Earl of Rutland took over Rievaulx

and expended its iron workings

Byland Abbey had 1,500 ewes. It had 4

watermills, a fish house and 3 fulling mills.

The churches at the monasteries were

stripped of their lead rooves.

Henry started to accumulate chests of

gold stored in his bed chamber. There was vast looting and thousands of objects

and works of art taken, and often melted down.

Some historical material was preserved,

for instance by Matthew Parker, Master of Corpus Christi, Cambridge, who saved

many ancient documents.

The significant wealth accumulated from

the Church by the monarchy was spent on creating a new navy and on a futile war

with France in 1544.

The Pilgrimage

of Grace.

1538

It was ordered that the English Bible

should be put into every parish church.

1544

In May 1544, war with France gave rise

to the first officially approved church service in English and to the litany in

the Book of Common Prayer. It was written by Cranmer to encourage prayers for

victory.

1547

The six year reign of Edward VI was a

period of religious consistency.

·

The

reformist Archbishop Cranmer was able to take greater control over religious

affairs

·

There

was a tendency for the evangelists across Europe and in England to become

stricter

·

There

was an extension of the use of English in services

A 1547 edict required the removal of

shrines, candlesticks, effigies and paintings. Poor boxes were to be placed

into churches.

The

Book of Common Prayer became the compulsory liturgy. This would also become the

focus of the growth of the English language, and many phrases which came into

common use derived from it.

1552

A more reformist version of the Book of

Common Prayer was adopted.

1553

Queen Mary (1553 to 1558) wanted to

restore the authority of Rome in the Counter

Reformation.

1556

At first Mary had used subtlety hoping

to encourage a return to the Papal fold. She appointed her cousin, Cardinal

Reginald Pole to negotiate with Rome as legate, and procure a forgiveness of

past sins and a return to the Roman Church.

However Cardinal Pole was not trusted in

Rome and Pope Paul; IV rejected him and revoked his legacy.

Ironically Mary found herself using her

royal; power over the English church to defy the wishes of Rome.

There were also practical difficulties

in returning to the traditional church, since religious objects had been

disposed of and religious buildings now used for other purposes.

The Evangelicals continued to meet and

resist the changes.

And so it was that Mary and Cardinal

Pole turned to force, earning Mary the nickname Bloody Mary

·

There

followed the most intense persecution of the time in Europe

·

280

Protestants burned at the stake.

·

Possession

of heritable literature was subject to the death penalty

·

The

Heresy Laws were reenacted in 1554

·

Bishop

Latimer of Worcester, Bishiop Ridley of London and Archbishop Cranmer were

burned at the stake.

In London there was some sympathy for

stamping down on heresy. However there was increasing sympathy for the victims

of the persecution.

The Reformation and the Counter

Reformation:

·

Led

to the destruction of significant artistic expression

·

Whilst

mass slaughter was prevented by a royal tendency to keep things in bounds,

nevertheless some 1,000 executions for heresy (perhaps a fifth of the

executions across Europe at the time)

·

England

began to see herself as an Empire, under rulers with proclaimed rights from God

·

However

much power was increasingly influenced by parliaments who adopted increasing

functions dubbed omnicompetence

·

A

national consciousness emerged distinct from the rest of Europe which was

centred on Rome – religion became nationalised with its English bible and

prayer book

1558

Elizabeth annulled Mary’s counter

reformation. As the daughter of Anne Boleyn, she relied on royal supremacy and

the reformist principles of her father:

·

The

Act of Supremacy 1558,

An Acte restoring to the Crowne thauncyent Jurisdiction over the State Ecclesiasticall

and Spirituall, and abolyshing

all Forreine Power repugnaunt

to the same

·

The

Act

of Uniformity 1559, authorising a book of common prayer which was similar

to the 1552 version but which retained some Catholic elements

·

The

Thirty

Nine Articles 1563

This was the foundation of a unique

religion which was later called Anglicanism.

“It looked Catholic and sounded Protestant.” It was a religious middle

way. It was a compromise and perhaps the foundation of the British spirit of

compromise. It contrasted to a time of polarisation in Europe, when the badges

of Catholic and Protestant started to be used for the first time (prior to

that, the evolution of the church was seen more as turbulent schisms occurring

within a single Christian church).

·

Elizabeth

promoted choral music – she retained the choir of King’s College Cambridge

which had been restored by Mary

·

She

promoted bell ringing which purists considered to be sinful

·

She

had no sympathy for hardliners from either wing of the religious divide

·

She

stopped heresy trials

1630

Charles faced a serious religious

challenge., with a growing intensity of feeling about religion.

The parish had become the social

cohesion of local communities, about 500 to 600 folk bound together, which

reflected the social and political as well as religious hierarchy.

Puritanism was the name given to the ‘godly’ by

their opponents. Mostly Calvinists who believed in predestination and that God

had chosen an elect for salvation, God controlled everything that happened.

·

Their

beliefs caused psychological stress.

·

In

some ways they reinforced existing hierarchies and elect gentry imposed strict

order on the idle and drunk

·

They

also appealed to subversives, who saw themselves as godly with a right to

oppose and reprimand their ungodly superiors

Arminianism took its name from Jacobus Arminius,

and favoured free will, in direct opposition to the Puritans. They did not see

the Catholics as a false religion. This was the focus of Charles I and William

Laud, the Archbishop of Canterbury.

There were fears that Charles was

getting to close to Catholicism and this was reinforced by his Queen Henrietta

Maria’s practice of her Catholicism.

Charles tended to be tolerant of

religious matters and no one burned for heresy during his reign. Indeed 1569 to

1642 was a time when there was no rebellion.

Meantime Scotland, a more turbulent and

militarised society, was left to govern itself since 1603 and there was a

growth of a Calvinist model of Scottish Presbyterianism, run by committees of

lay elders and clergy and without the rule of bishops.

In 1636, Archbishop Laud ordered the use

of a Scottish remodel of Cranmer‘s Book of Common Prayer. In July 1637, there

was outrage and resistance at St Giles in Edinburgh.

By 1638 a committee of lairds, burgesses

and ministers had drafted a Covenant to uphold the Scottish kirk and resist

popery. The Covenanters were seen as rebels

by Charles.

1688

After the Glorious Revolution, the

Church of England became more and more central to everyday life from feeding

the poor to repairing roads.

The Act

of Toleration 1689 allowed dissenters a freedom to worship separately, though

not yet extended to Catholics and Jews.

Dissenters could vote and become MPs,

but the Corporation and Test Acts 1661 and 1672 required holders of public

office to be communicant members of the Church – in practice many took

communion occasionally just to qualify.

The Whig-Tory divide manifested itself in

the church, with festive, communal, royalist Tories and puritanical,

capitalistic, parliamentarian Whigs developing there own separate cultures. Merchants

and urban businessmen were often Whigs and dissenters and a non

conformist society emerged, with even the once feared Quakers becoming

rooted in the wealthy merchant class.