|

|

Rievaulx

Historical and geographical information

|

|

Dates are in red.

Hyperlinks to other pages are in dark blue.

Headlines are in brown.

References and citations are in turquoise.

Contextual history is in purple.

This

webpage about the Rievaulx has the

following section headings:

- Farndale

family history and Rievaulx

- Rievaulx

Abbey, overview

- Timeline of

Rievaulx’s history

- The abbots of

Rievaulx

- Photographic

record

- Links, texts

and books

Farndale family history and Rievaulx

The name Farndale, first occurs in

history in the Rievaulx Abbey Chartulary. See FAR00002.

The relevant year for Farndale history is 1154 when a record appeared I the

Rievaulx Chartulary.

Gundreda, on behalf of her guardian, Roger de

Mowbray, gave land to Rievaulx abbey land which included a place called Midelhovet,

where Edmund the Hermit used to dwell, and another called Duvanesthuat,

together with the common pasture within the valley of Farndale.

The name Farndale, first occurs in history in the Rievaulx

Abbey Chartulary in a Charter granted by Roger de Mowbray to the Abbot

and the monks of Rievaulx Abbey in 1154. By it Roger bestowed upon the

Monastery, ‘….Midelhovet, that clearing in

Farndale where the hermit Edmund used to dwell; and another clearing which is

called ‘Duvanesthuat’ and common of pasture in the

same valley of Farndale….’

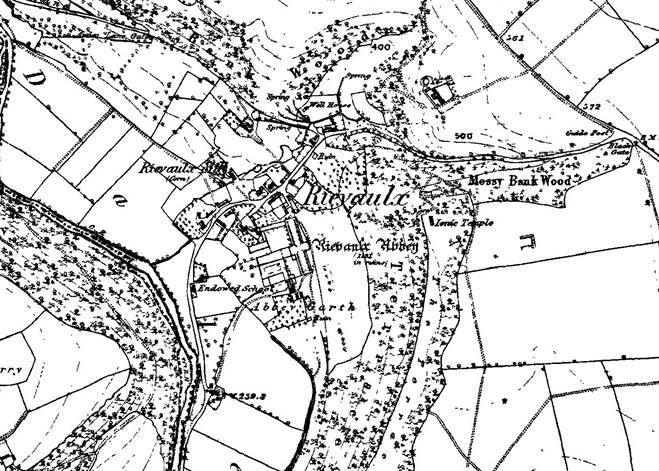

Rievaulx Abbey

The Victoria County History – Yorkshire, A History of the

County of York: Volume 3 Houses of Cistercian monks: Rievaulx, 1974: The monastery of Rievaulx, the earliest

Cistercian house in the county, was founded by Walter Espec in 1131. The abbey

is situated at the head of a deep valley formed by a bend of the River Rye

below Old Byland. It stands on a plateau, partly of natural and partly of

artificial origin, through being cut into the bank behind which slopes gently

down from the famous terrace above. Opposite to the abbey rise the wooded sides

of Ashberry Hill, and the valley is narrowed in at its lower end by another

wooded bank.

Rievaulx, 1857

Timeline of Rievaulx’s History

1098

Rievaulx was an abbey of the Cistercian

order, which was founded by St Bernard of Clairvaux at Cîteaux,

near Dijon, France, in 1098. The Cistercian order emerged in France in the late

11th century and spread rapidly across Europe.

It was to become one of the most

remarkable European monastic reform movements of the 12th century, placing an

emphasis on a return to an austere life and literal observance of the rules set

out for monastic life by St Benedict in the 6th century.

A major regional reason for the success

of the Cistercians was the rigour of their religious life. The order sought to

live according to the purest possible interpretation of the rule of Benedict.

Their services were dignified but simple, allowing more time for reading and

manual work. The Order’s art and architecture was austere.

1128

The Cistercians first appeared in

England at Waverley, Surrey, in 1128.

The Cistercian Order of ‘white monks’

(as they came to be called, after their dress which distinguished them from the

black-clad Benedictines) was founded in Citeaux, France, in 1098, upon the

initiative of a number of dissident Benedictine monks.

These Benedictines had grown dissatisfied with the extent to which their own

ancient Order had gradually departed from the austere manner of living which

had characterised the earliest forms of monasticism based upon the Rule of St

Benedict. Like the Desert Fathers includikng John the

Baptist the first monks sought to associate spiritual devotion with a strict

material asceticism; and this was one of the ideals to which the Cistercian

Order committed itself to return. Alongside this, the

Cistercians devoted themselves to the ideal of taking on manual labour as part

of their objective of self-sufficiency.

Like other Orders, they accepted gifts

of land on which to build their monastery, farm sheep for wool and grow food,

or from which to extract minerals, quarry stone and retrieve timber for

building and repairs. However, initially at least, they would accept only

undeveloped land. Land on which rent-paying tenants were already settled, mills

which took tolls from tenants obliged by feudal laws to use them, manors with

feudal rights which generated income or which bound tenants to give a certain

number of unpaid working days to the lord, and churches owning the right to

exact tithes from their lands, all these they (initially) declined to accept,

partly on the grounds that such assets conflicted with the ideology of

self-sufficiency, partly because their management would entail an inescapable

engagement with the secular world and the risk of a corrupting materialism

which monastic isolation was designed to avoid.

Initially, then, the Cistercian

monastery might be distinguished by the sight of the white

monks labouring in the fields, diverting streams through monastic

water-systems, hauling timber from the woodlands, and suchlike physical,

non-intellectual, non-scholarly activities, scheduled to alternate with the

appointed hours of formal religious devotions. But it was not long before

individual monasteries began to engage commercially with the secular world

beyond their boundaries.

1131

Walter Espec encouraged the founding of the

Cistercian abbey at Rievaulx in 1131. These austere monks sought

detachment from the world, in contrast to the Benedictines and the

Augustinians.

A breakaway group from St Mary’s Abbey

in York established Fountains Abbey and Kirkham Priory.

The

Victoria County History – Yorkshire, A History of

the County of York: Volume 3 Houses of Cistercian monks: Rievaulx, 1974:

The abbey of

Rievaulx, the earliest Cistercian monastery in the county, was founded in 1131

by Walter Espec, who gave to certain of the monks sent to England about 1128 by

St. Bernard from Citeaux land near Helmsley, in the valley of the Rye, on the

north side of which the monastery was built. From its position it received the

name of Ryedale, or Rievaulx.

Although the house was meagrely endowed

by the founder, it speedily received other donations of land of considerable

extent and value, so that within probably half a century from the foundation of

the abbey it had acquired possession of no less than 50 carucates of land

besides other property; all are fully described in alphabetical order by Burton.

… the number of monks who first came to Rievaulx must have

largely exceeded the number usually sent to form a new convent, and it implies

that Rievaulx was regarded as the source from which other Cistercian

monasteries might be peopled.

The Cistercians’ way of life was guided

by the rule of St Benedict.

The choir monks’ day was structured

around the celebration of eight daily services in the church which were

dedicated to the Virgin Mary. Reading was an important part of the monastic

day. Time was also set aside for manual work including copying manuscripts.

Lay brothers formed part of the monastic

community. Mostly literate, they had their own daily routine of short church

services and work on the Abbey estates. In the later Middle Ages servants

replaced the lay brothers.

Walter Espec (died 1154) was lord of

nearby Helmsley and a royal justiciar. He was an active supporter of

ecclesiastical reform and had founded Kirkham Priory for the reformist

Augustinian canons in about 1121.

The arrival of the reform-minded

Rievaulx community sent shockwaves through the older Benedictine houses of the

north. The foundation at Rievaulx was carefully planned by Bernard of Clairvaux

to spearhead the monastic colonisation of northern Britain.

1132

William was the founding Abbott from

1132 to 1145, with twelve monks. Rievaulx’s first abbot, William, dispatched

colonies to establish daughter houses at Warden in Bedfordshire and Melrose in

1136, Dundrennan in 1142 and Revesby in 1143.

The first buildings at Rievaulx were

temporary wooden structures.

The Victoria County History – Yorkshire, A History of the

County of York: Volume 3 Houses of Cistercian monks: Rievaulx, 1974: Quite early in the history of the house

a strange agreement was entered into between the monks of Rievaulx and the

canons of Kirkham, whereby the latter were to cede to Rievaulx the whole of

Kirkham, with its church and the canons' buildings, gardens, and mills, as well

as Whitwell and Westow, and 4 carucates of land in Thixendale,

and of their stock a wagon and 100 sheep, on condition that the patron would

give them the whole of Linton and ' Hwersletorp.'

Their prior and his assistants

(sui auxilarii) were to build them a church and other monastic offices. It seems that there must

have been a proposal that Kirkham should become Cistercian (a proposal which

caused a division in that house), and that it was intended that Rievaulx should

take over Kirkham as a Cistercian monastery, the dissentient canons having a

new house built for them elsewhere. It is clear that Walter

Espec was living when the agreement was drawn up, and his preference for

the Cistercian order as evidenced by his entry as a monk at Rievaulx, may have

made him wish that his three foundations, Kirkham, Rievaulx, and Warden should

be of the Cistercian order; the agreement, however, fell through.

1134

In 1134 Aelred, then a young man, became

a monk at Rievaulx. He came

to Rievaulx as a postulant in 1134, rising quickly to be elected abbot in 1147.

He enjoyed a reputation as a brilliant writer and England’s most revered

biblical scholar, Latin stylist and pastoral master.

1138

In the late 1130s Abbot William began

the construction of stone buildings around the present cloister. The northern

part of his west range, which housed the abbey’s lay brothers, still survives,

as does a fragment of the south range.

Rievaulx received grants of land

totalling 6,000 acres. The Yorkshire Archaeological

Journal, Vol 40, Page 636: Although arable granges would require

access to pasture land this would be more important to

pastoral granges in which movement of animals, sometimes over great distances,

was an economic necessity. Most grants of common pasture to the monasteries

were made early. Rievaulx had common in Welburn (1138 to 1143); Wombleton (1145 to 1152); Farndale (pre 1155), for

example, and sometimes the privilege was purchased, eg

Arden Hesketh (pre 1159) 1 ½

marks, Morton (1158 to 1160) 1 mark... Some specific grants of

sheep pasture were very large... and undoubtedly induced the monasteries to set

up their granges nearby.

1143

The Victoria

County History – Yorkshire, A History of the County of York: Volume 3 Houses of

Cistercian monks: Rievaulx, 1974: In 1143 Roger de Mowbray granted

Old Byland to the convent of monks who had left Calder, intending that they

should build their monastery on the south side of the River Rye, but the site

was too near Rievaulx, and each house heard the bells of the other.

1147

Aelred

was Abbot between 1147 and 1167. He was a Northumbrian of old English descent

raised at the court in Scotland. He wrote several quite extensively:

Our food is scanty, our garments rough,

or drink is from the stream and our sleep is often upon our books. Under old tired limbs there is but a hard mat. When sleep is

sweetest, we must rise at the bell’s bidding. Self will

has no scope. There is no moment for idleness or

dissipation. Everywhere peace, everywhere serenity, and marvellous freedom

from the tumult of the world. To put all in brief, no perfection expressed

in the words of the gospel or of the apostles or in the writings of the

fathers, or in the sayings of the monks of old is wanting to our order and our

way of life.

The monk Daniel Walter Daniel, a

contemporary of Aelred, wrote a biography of his Abbot. This describes how

under Aelred’s compassionate leadership Rievaulx became “the home of party

and peace, the abode of perfect love of God and neighbour.” Aelred’s vision

of monasticism was founded on a spiritual love for his fellow monks.

At its height in the mid twelfth century

Rievaulx was home to 140 monks and 500 lay brothers and servants. Cistercian

monasticism evolved considerably during the Middle Ages. The Abbey 's

magnificent buildings provide evidence of these changes. Spiritually and

architecturally Rievaulx was the most important Cistercian Abbey in England.

This increase in numbers required much

larger buildings. Many of the standing buildings today date from Aelred’s rule.

A monumental church was begun in the late 1140s, one of the earliest great

mid-12th-century Cistercian churches in Europe.

Rievaulx attracted the support of

important benefactors, many of whom were buried here. They believed that burial

at the Abbey and prayers of the monks would hasten the passage of their souls

through purgatory to heaven.

The abbey lies in a wooded dale by the

River Rye, sheltered by hills. The monks diverted part of the river several

yards to the west in order to have enough flat land to build on. They altered

the course of the river twice more during the 12th century. The old course is

visible in the grounds of the abbey. This is an illustration of the technical

ingenuity of the monks, who over time built up a profitable business mining

lead and iron ore, rearing sheep and selling wool to buyers from all over

Europe.

Rievaulx was the hub of a trade network

but extended as far as Italy. Fleeces from the Abbey’s flocks were highly

prized and Rievaulx became wealthy.

Abbot Aelred's monastery at Rievaulx in

the mid Twelfth Century.

Monastic

Farming

The Cistercian way of life was simple.

The Cistercian abbots accepted donations of land but generally avoided settled areas, or cleared them (as at Hoveton

and Welburn near Kirkbymoorside).

Significant

land grants were given to the monasteries. Rievaulx soon had a great swathe of properties,

throughout Ryedale and stretching to Teesmouth and Filey. At

its peak it had 140 monks and 400 lay brothers. They

tended to site their granges away from villages. Monastic farms were a separate

economic force. The sheep grange was dominant in Yorkshire with many examples,

including at Farndale, of donations of rights to pasture a fixed number of

sheep.

An interesting example relates to the

market in wool. Traders in wool outside the monasteries were interested in

buying up any surpluses the monks produced from their sheep-farming. Cistercian

houses such as Byland Abbey (North Yorkshire) began to deal in the market, and built ‘woolhouses’

where not only was wool stored but facilities were provided for merchants to

come and inspect the monks’ surplus produce and negotiate their price. Byland Abbey, distinguished for its wool

production, for a time maintained a woolhouse in

York, a city which had mercantile links by the Ouse and Humber rivers to

continental markets.

Likewise, the Cistercian abbey of

Rievaulx established ‘granges’ - farms they owned and managed themselves -

where they grew food and raised sheep, cattle and horses, as well as producing

various raw materials. Beyond supplying the monastic community at the mother

house with its needs, they were expected to produce a surplus which could then

be marketed to yield an income.

1154

The Victoria

County History – Yorkshire, A History of the County of York: Volume 3 Houses of

Cistercian monks: Rievaulx, 1974: … the monks

of Byland moved further off, but the lands of the two houses were coterminous,

and to avoid possible disputes an agreement was entered into between Aelred,

Abbot of Rievaulx, and Roger, Abbot of Byland, about 1154. This agreement began

by a mutual engagement of masses and prayers for deceased brothers of the two

houses and a combined action against oppression or misfortune by fire or

otherwise, and then defined the relations of the two houses as to their

adjoining lands, both the homeland of the two houses and their properties at a

distance, where they adjoined each other. As to the homelands, the Byland monks

conceded to their brethren of Rievaulx that they should have their bridge so

constructed that it should hold back the wood they conveyed by the River Rye,

and also a road from the bridge through the wood and field of Byland to a place

called Hestelsceit, 18 ft. in width, which the monks of

Byland were to keep in repair. They were to have mutual rights on each others' banks of the river.

The name Farndale, first occurs in history in the Rievaulx Abbey Chartulary

in a Charter granted by Roger de Mowbray to the Abbot and the monks of Rievaulx

Abbey in 1154. By it Roger bestowed upon the Monastery, ‘….Midelhovet,

that clearing in Farndale where the hermit Edmund used to dwell; and another

clearing which is called ‘Duvanesthuat’ and common of

pasture in the same valley of Farndale….’

1159

The Victoria

County History – Yorkshire, A History of the County of York: Volume 3 Houses of

Cistercian monks: Rievaulx, 1974: Another

incident in the early history of the house is also difficult to understand. It

is revealed in a rescript from Pope Alexander III (1159-81) to the Bishop of

Exeter, the Abbot of St. Mary, York, and the Dean of York directing them to see

that amends were made for the spoliation of the property of the abbey of

Rievaulx by certain persons named, and the strange thing is that the offenders

were some of the chief benefactors of the abbey. Robert and William de

Stuteville had been guilty of various acts of depredation, and the pope ordered

that within thirty days they were to make restitution, under pain of

excommunication. Seven other offenders are named, including Roger de Mowbray

and his son Nigel.

1160

By 1160 the

Abbey was home to 640 men.

1167

1170

The Yorkshire

Archaeological Journal, Vol 40, Page 481. The Monastic Settlement of North East Yorkshire: … After

the foundation, sometimes a very large grant as at Guisborough and Whitby, or a

very niggardly ones as at Rievaulx, the accumulation of lands and rights was

rapid, alarmingly so. At Rievaulx, for example, the greater parts

of the lands were acquired and a very large number of granges

established by the end of the twelfth century. Even by 1170 the

monks had required all Bilsdale, Pickering Marshes, parts

of Farndale and Bransdale, the Vills of Griff, Tileson,

Stainton, Welburn, Hoveton, and the lands of Hummanby, Crosby, Morton, Wedbury,

Allerston, Heslerton, Folkton, Willerby, Reighton...

Some donors had apparently not bargained for such a rapid increase in monastic

possessions. It came as a shock to find that the monks were not “all that was

simple and submissive; No greed, no self-interest …” The result was that men

like Roger de Mowbray, Robert de Stuteville, Everard de Ros and other great

Lords, formerly great donors and foundations, began unsuccessfully, to evict

the monks from certain lands, but monastic expansion continued...

The

Yorkshire Archaeological Journal, Vol 40, Page 636:

… The monks had a larger area given to them at Skiplam

by Gundreda de Mowbray (1138 to 1143).

This allowed for expansion since the grant included Farndale Head and

Bransdale, about 18 square miles of dale pasture land.

It must not be imagined that the monks were beginning colonisation in an area

entirely unused. Although the extent of settlement and cultivation

was small it had existed. Griff and Stiltons, for

example, were vills before 1069 but in 1086 were

waste. Presumably the monks grant here was of land which had gone out of

cultivation. Their task would be one of reestablishment rather than

the colonisation of new land. It was a decided advantage to have such a

tried starting point. At Skiplam, too,

although the greater part of the area had never been settled for or tilled,

there is evidence to show that the monks began the efforts from land already

or recently cultivated. Gundreda’s

grant, for instance cover included “de culta

terra” (“of cultivated land”), as well as a grant “ubi culta

terra deficit versus aquilonem” (“where the

cultivated land declines towards the north”). Of course

the subsequent work of the monks in all these places did result in a very

great extension of the cultivated land. But it is worthwhile to point out

that the Cistercians, so-called solitaries, did in fact owe something to

previous lay efforts. In fact, it was largely the success or failure of lay

farmers in a particular area which helped the monks to see the potentialities

it offered them. …. The granges had easy access to two types of pasture -

moorland and valeland. Skiplam,

for instance, had extensive pasture in the moorland dales, only a few miles

north. There was the rough pasture (saltum) of Farndale Head and common pasture

in Farmdale and Bransdale. It had, too, the meadow of

the clayland at its disposal. This was even nearer,

being no more than three miles to the south. The plough teams from Skiplam could easily pasture at Welburn, where the monks

had common pasture rights, or at Rook Barugh, Muscoates,

and several other places, just as the animals from Griff went to Newton grange

for pasture. The limestone hills had then a great deal to recommend them for

the observant eyes of the monks.

1220

In

the early 13th century Rievaulx’s library contained 225 books mainly

theological and monastic texts.

1270

1279

The Victoria

County History – Yorkshire, A History of the County of York: Volume 3 Houses of

Cistercian monks: Rievaulx, 1974: Rievaulx being a Cistercian abbey

and so exempt from episcopal visitation, very little is known of its internal

affairs or history. One incident of interest is recorded in 1279. William de

Aketon, a monk of Rievaulx, evidently wishing to abandon monastic life, came to

the prior, Nicholas of York, and said that he was a leper and could no longer

dwell with the brethren, and therefore begged leave to depart.

1322

The

Victoria County History – Yorkshire, A History of

the County of York: Volume 3 Houses of Cistercian monks: Rievaulx, 1974:

What is generally known as the battle of Byland took place in October 1322,

and must have greatly affected the two abbeys of Rievaulx and Byland, but

nothing certainly is known as to what happened to Rievaulx in consequence of

it. The encounter between the English and the Scots took place on the high

ground between the two houses and near Byland, but according to the most

trustworthy accounts the English king was at Rievaulx and not Byland Abbey when

he received news of the defeat of his army. He fled at once to York for safety,

leaving, according to the chronicler of Lanercost,

his silver plate and a great treasure behind him at Rievaulx. This fell into

the hands of the Scots, and we are left to realize the sinister significance of

the words et monasterium spoliaverunt

without being told any details of the spoliation.

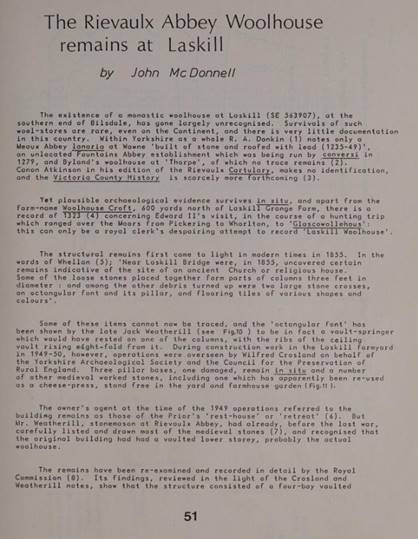

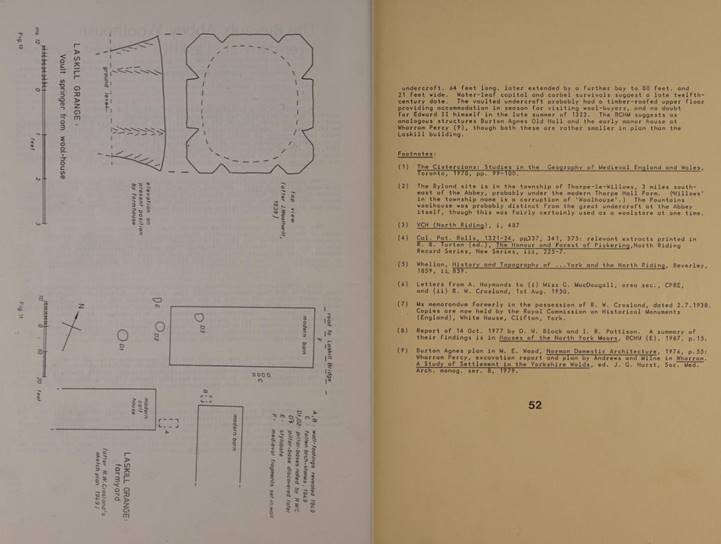

The Rievaulx Abbey Woolhouse (Ryedale Historian, 1988, Vol 14)

1348

The Black

Death in the middle of the 14th century also took a heavy toll.

1380

In

1380 there were only 15 monks and 3 lay brothers at Rievaulx.

1406

The Victoria County History – Yorkshire, A History of the

County of York: Volume 3 Houses of Cistercian monks: Rievaulx, 1974: In 1406 a glimpse of the inside life of

the abbey is afforded, with one of those little touches which give life to a

picture, by a mandate of Pope Innocent VII, which states that each monk in

priest's orders was bound in turn for a week at a time to sing mass solemnly (alta voce ad notam) at the high altar, and to say the

invitatory, such monks being called ebdomadarii, but

that Thomas Beverley had an impediment of tongue, on account of which he could

not do this becomingly, so he was granted a dispensation from performing the

office.

1533

The

Victoria County History – Yorkshire, A History of

the County of York: Volume 3 Houses of Cistercian monks: Rievaulx, 1974:

The concluding years of Rievaulx were stormy, and it is

clear that the abbot, Edward Kirkby, was ill affected towards the

impending religious charges. It was desirable, therefore, to get him out of the

way. On 1 September 1533 (fn. 20) the king's commissioners complained that

Abbot Kirkby had written a letter ' to the slaundare

of the kinges heygnes, and

after the kynges lettars receivyed, dyd imprison and otharways punyche divers of hys brethren whyche ware ayenst him and hys dissolute liwing; also dyd

take from one of the same, being a very agyd man, all

hys money.' Further they complained that 'all the cuntre makythe exclamations of

this Abbot of Rywax, uppon hys abhomynable liwing and extortions by hym commyttyd, also many wronges to

divers myserable persens

don, whyche evidently duthe

apere by bylles corroboratt to be trwe with ther othes corporal, in the presens of the commissionars and

the said abbott takyn, and opon the same xvi witnessys examynyd, affermyng ther exclamations to be trwe.'

The commissioners concluded by stating that they had ' remowyed

hym from the rewlle of hys abbacie and admynistration of the same.'

1538

Rievaulx

was closed during the suppression of the monasteries in 1538 leaving only

shattered remains. Rievaulx Abbey was shut down on 3

December 1538, as part of the Suppression of the Monasteries that took place

under Henry VIII in 1536–40. By this time Rievaulx’s community had shrunk to

just 23 monks. It was sold to Thomas Manners (d.1543), 1st Earl of Rutland, who

was closely associated with the royal court.

Rutland

dismantled the buildings, reserving the roof leads and the bells for the king.

His steward at nearby Helmsley, Ralf Bawde, recorded

the process of dismantling, leaving remarkably detailed accounts of the process

and the form and contents of individual buildings.

1545

One

of the buildings within the abbey precinct was called ‘the Yron

Smiths’. Abbey records show that this was a water-powered forge used for making

the many objects of iron required by a monastery, from nails to tools and

cutlery.

Under

Rutland the ironworks grew in scale. By 1545 enough iron ore was being smelted

to keep four furnaces busy. The vaulted undercroft of

the refectory was used as a dry place to store the charcoal used to heat up the

ore to the temperature required to extract molten iron.

1577

The

ironworks continued to grow throughout the later 16th century, with the

addition of a blast furnace in 1577, possibly the first in the north of

England.

1600

A

new forge was built at the south end of the old monastic precinct, which was

re-equipped between 1600 and 1612.

1640

By

the 1640s, local supplies of timber for charcoal were all but exhausted, and

the ironworks was closed.

The Abbots of Rievaulx

|

William I, 1131, died 1145 Maurice, 1145 Waltheof Aelred, 1147, 1160, 1164, died 1167 Sylvanus, occurs 1170 Ernald, 1192, resigned 1199 |

William Punchard, occurs 1201-2, died

1203 Geoffrey (or perhaps Godfrey), 1204 Warin, occurs 1208, died 1211 Helyas, resigned 1215 (Abbot of Melrose

1216) Henry, 1215, died 1216 William III, 1216, died 1223 Roger, 1224 to 1235, resigned 1239 Leonias, 1239, died 1240 Adam de Tilletai,

1240-60. Thomas Stangrief,

occurs 1268 William IV (de Ellerbeck), 1268-75 William Daneby,

1275-85 Thomas I, 1286-91 |

Henry II, 1301 Robert, 1303 Peter, 1307 Henry, occurs 1307 Thomas II, 1315 Richard, occurs 3 June 1317 William VI, 1318 William de Inggleby,

occurs 1322 John I, 1327 William VIII (de Langton), 1332-4 Richard, 1349 John II, occurs 1363 William IX, 1369-80 John III, occurs 1380 |

William X, 1409 John IV, occurs 1417 William (XI) Brymley,

1419 Henry (III) Burton, 1423-29 William (XII) Spenser, 1436-49 John (V) Inkeley,

1449 William (XIII) Spenser, 1471, 1487 John (VI) Burton, 1489-1510 |

William (XIV) Helmesley,

1513-28 Edward Kirkby, 1530-1533 Rowland Blyton 1533-8 |

|

(The Victoria

County History – Yorkshire, A History of the County of York: Volume 3 Houses of

Cistercian monks: Rievaulx, 1974)

Photographic Record

Links, books and texts

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|