Alcuin of York and the birth of

modern education

The world of Ecgbert and Aethelbert,

successors to Bede, and their pupil Alcuin, who took York’s powerhouse of

knowledge to the court of Charlemagne to pioneer the European educational

system

The Teacher of York

Alcuin

of York was a scholar, clergyman, poet, and teacher from York, then part of the Kingdom of Deira, later Northumbria. He was influential

as a writer, as a mathematician, and in his writing. His work gave rise to the

revival of intellectual life in the area around York which extended across

Europe.

He brought

the educational traditions and teaching methods from York to the court of Charlemagne,

extending those traditions across Europe. He laid the foundations of the

educational system, focused on monasteries and cathedral schools north of the

Apls, which prevailed until the emergence of universities in the twelfth century.

There is an In Our Time podcast about him and another Podcast in the BBC Series

Anglo Saxon Portraits, is an essay on Alcuin, the Scholar by

Mary Garrison.

Renaissance

The Venerable Bede died in Jarrow in 735 CE, having

established a renaissance of learning following the chaotic centuries since the

end of the Roman empire, focused on the Benedictine study of the Bible. Bede’s

work was the inception of an educational system based upon training in Latin

and loosely on the liberal arts (liberalia

studia), the basic literary and numerical studies adopted from Roman

education.

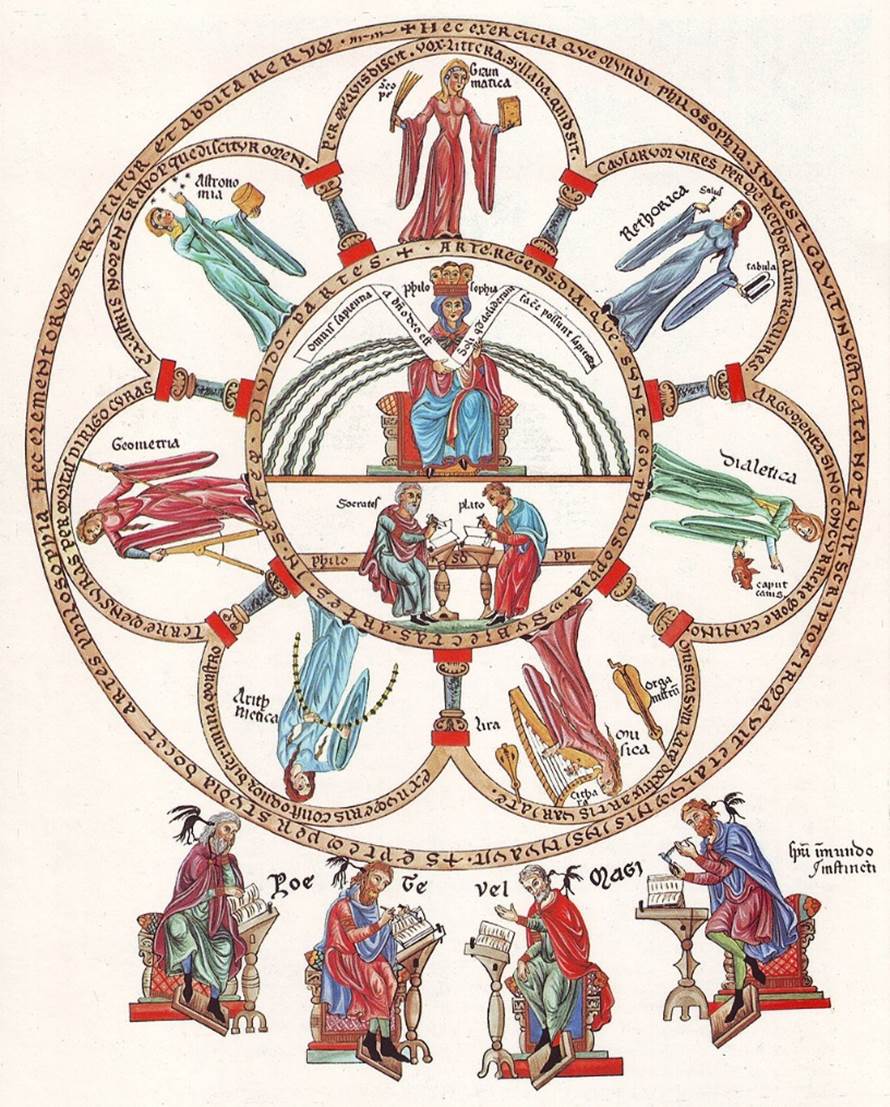

Pythagoras had speculated that there

was a mathematical and geometric harmony to the cosmos or the universe and his

followers linked the four arts of astronomy, arithmetic, geometry, and music

into one area of study to form the "disciplines of the medieval quadrivium".

Over time, rhetoric, grammar, and dialectic (or logic) became the educational

programme of the trivium. Together the quadrivium and the trivium

came to be known as the seven liberal arts. Bede

did not wholly embrace the Liberal Arts himself, but his monastic endeavours

created the philosophical landscape for their revival not so far from the coast

at Whitby.

The

Liberal Arts

The

Benedictine monasteries had become the main focus of learning by the sixth

century, following the disintegration of the Roman empire. Benedictine

monasteries were repositories of learning as they focused on prayer, study and

manual labour. Study was intended to assist an understanding of the Bible

through copying scripts alongside a learning of the liberal arts. Roman

knowledge through an understanding of Latin was an instrument to assist

Christian understanding. Over time, this became the basis of early education.

Among Bede’s

pupils was Ecgbert, brother of the Northumbrian King Eadberht (who reigned from

737 CE to 758 CE). When King Eadberht founded an archbishopric at York, Ecgbert became Archbishop of York

in the year of Bede’s death. It was at York, that Ecgbert continued Bede’s

work.

Ecgbert

founded a school attached to the cathedral for the sons of local nobles.

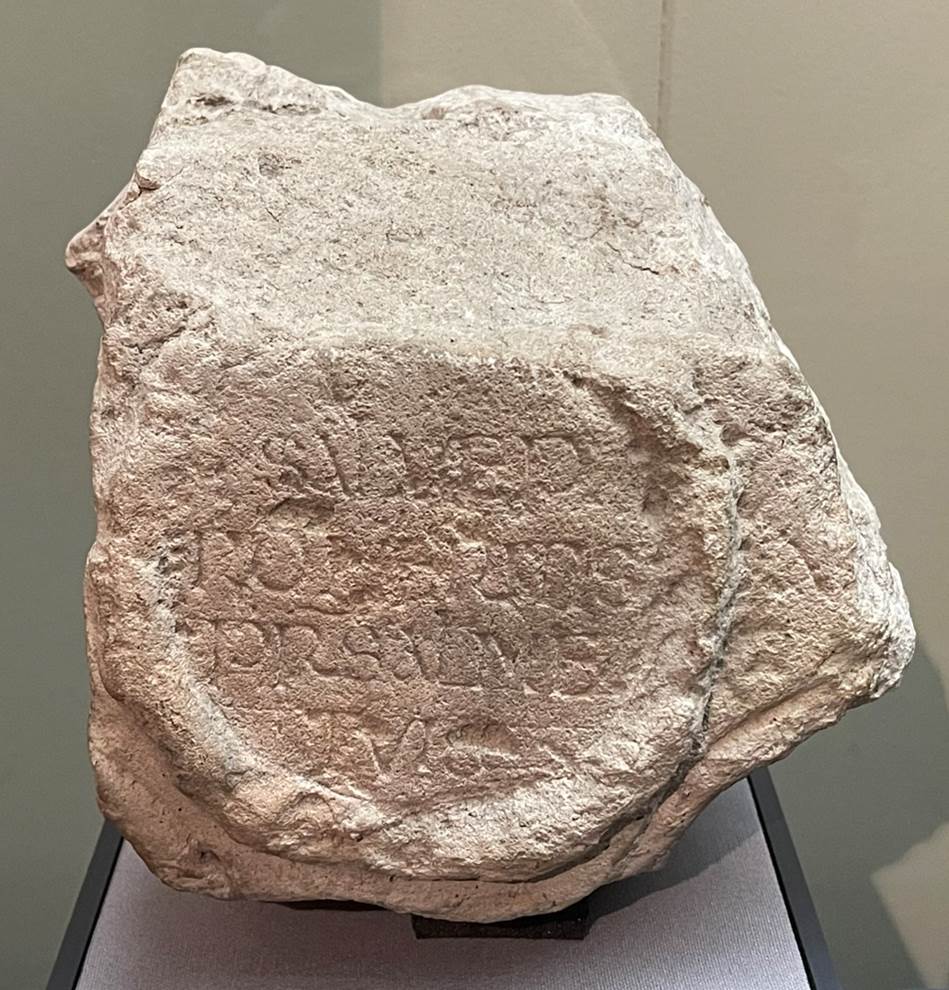

Silver

coin of King Eadberht and Archbishop Ecgbert from Fishergate, York, circa 758

CE (Yorkshire

Museum)

Education

provided moral teaching to support the aims of Augustine’s Christian Doctrine.

Augustine had advocated the harnessing of education to Christian ends.

These were

peaceful and stable years in Northumbria, before the arrival of the Vikings at

Lindisfarne in 793 CE.

As Ecgbert’s

responsibilities increased, he entrusted the running of the school to his

kinsman and pupil, Aethelbert. The fame of the school grew under Aethelbert and

pupils came from across the country and from overseas. Aethelbert travelled to

the Continent to collect books and he spread knowledge of the school. He made

it his mission to collect books from across Europe and used his own private

wealth to amass a remarkable library at York.

Alcuin, in his longest poem, later included a bibliography of this remarkable

library.

Where

books are kept

Small

roofs hold the gifts of heavenly wisdom;

Reader,

learn them, rejoicing with a devout heart.

The

Wisdom of the Lord is better than any treasures

For the

one who pursues it now will have the pathway of light

(Alcuin, Carmen, 105, i: Dümmler 1881, p. 332)

Aethelbert

pursued his religious ambitions through the assembly of knowledge at York. He

was primarily a scientist. Because York was a cathedral, and not a monastery

like Bede’s Jarrow, students came from far places such as Ireland and Freisland, and then left again with their learning. A

cathedral school was able to attract bright individuals from afar. Indolis egregiac iuvenes quoscumque videbat Hos sibi

coniunxit, docuit, nutrivit, amavit, “He

attached to himself, taught, nurtured, and loved all the young men of excellent

character whom he saw."

Prior to this

period of Renaissance at York, education had contracted to a narrow range of

studies, for purely religious purpose. What stood out at York was the evolution

of a range of learning far wider than a focus on salvation and the saving of

souls. Aethelbert was particularly interested in natural science and studied

plants and animals. His view was that the rationality of the universe had been

divinely created, and so human activity which helped to understand it was also

theologically justified. He believed that reason had a divine purpose and

envisaged the five zones of heaven – the seven planets; the regular motions of

the stars; the rising and setting of celestial objects; movement of the air and

tremors of earth; and the nature and diversity of men, livestock, and wild

beasts and birds.

It was

during Aethelbert’s time that Alcuin joined the school and became Ecgbert and

Aethelbert’s favoured pupil and a great friend of Aethelbert.

The young

Alcuin therefore came to the cathedral church of York during the golden age of

Archbishop Ecgbert and his brother, the Northumbrian King Eadberht. King

Eadberht and Archbishop Ecgbert oversaw the re-energising and reorganisation of

the English church, with an emphasis on reforming the clergy and on the

tradition of learning that Bede had begun. Ecgbert was devoted to Alcuin, who

thrived under his tutelage.

York became

an exceptional centre of leaning during the second half of the eighth century.

Ecgbert

promoted learning for its own sake at York, beyond merely religious learning.

Inspirer

of knowledge

Alcuin had a

profound love of poetry. He studied the liberal arts and Latin authors such as

Pliny (for natural history), Cicero (for rhetoric), the Anglo Saxon Aldhelm

(for grammar) and poets including Virgil, Lucan and Statius. He studied the

Bible, and the works of Gregory the Great, Cassiodorus and Bede. The study was

not particularly original, but aimed at conserving and digesting the heritage

of the past into handbooks for the survival of established teaching as a tool

for Christian knowledge.

Alcuin

accompanied Aethelbert on his travels at least once, and as Aethelbert grew

older, Alcuin became involved in teaching.

Alcuin

graduated to become a teacher during the 750s by which time Alcuin taught an

extraordinarily wide curriculum.

In York,

Alcuin drew inspiration for the school he would lead at the Frankish court. He

revived the school with the trivium and quadrivium disciplines,

writing a codex on the trivium, while his student Hraban wrote one on the

quadrivium.

It was

during this time in 766 CE that Charles I became King of the Franks.

Aethelbert

succeeded Ecgbert as Archbishop on 24 April 767. Alcuin’s ascendancy to the

headship of the York school, the ancestor of St Peter's School, began after

Aethelbert became Archbishop of York. Around the same time, Alcuin became a

deacon in the church. He was never ordained a priest and there is no evidence

that he took monastic vows, though he lived as if he had. Religious boundaries

were fluid at that time without a sharp division between disciplines.

Alcuin

taught the seven Liberal Arts. He stressed the correct use of Latin and wrote

textbooks in Latin. He followed Bede’s method of question and answer. He

promoted the study of the calendar, the computus,

and especially the once

controversial calculation of the date of Easter. He gave elementary

instruction in music, arithmetic and geometry.

He enjoyed riddles,

jokes and puns in his teaching methods. He made arithmetical

puzzles and seems to have been an excellent communicator. This was a very

Anglo Saxon teaching technique. The BBC Discovery podcast, Alcuin of York, is an

examination by Philip Ball of Alcuin’s famous river crossing riddle.

Alcuin

developed a friendly literary circle where its members had nicknames,

Alcuin was called Flacchus and a favoured pupil, Sigewulf, was known as Vetulus,

‘little old fellow”.

Alcuin wrote

about the beautiful inscriptions given to the Church in York by Bishop Wilfred.

This one reads “Hail, gracious priest, on account of your merits”, from St

Mary’s Church, Bishophill, York (Yorkshire

Museum)

Alcuin later

wrote a lengthy poem

recalling the magnificence of his beloved York at this time.

|

My heart is set to praise my home And briefly tell the ancient cradling Of York's famed city through the charms of verse. It was a Roman army built it first , High-walled and towered, and made the native tribes |

Of Britain allied partners in the task – For then a prosperous Britain rightly bore The rule of Rome whose sceptre ruled the world – To be a merchant-town of land and sea, A mighty stonghold for their

governors, |

An Empire's pride and terror to its foes, A haven for the ships from distant ports Across the ocean, where the sailor hastes To cast his rope ashore and stay to rest. The city is watered by the fish-rich Ouse |

Which flows past flowery plains on every side; And hills and forests beautify the earth And make a lovely dwelling-place, whose health And richness soon will fill it full of men. The best of realms and people round came there |

In hope of gain, to seek in that rich earth For riches, there to make both home and gain |

Alcuin

In 778 CE,

Eanbald became Archbishop of York and Alcuin became sole head of the school.

The

European Stage

In 781 CE,

King Elfwald sent Alcuin to Rome to confirm the

election of the new archbishop, Eanbald I, by collecting his vestment, the pallium.

He had already been to continental Europe at least once, and probably had

previously met Charlemagne.

On his way

home, on 15 March 781, he met Charlemagne in the Italian city of Parma. At this

time, Charlemagne was King Charles of the Franks, but he later became

Charlemagne, the Great, after his coronation as Holy Roman Emperor in 800.

Charlemagne

meeting Alcuin

(British Library)

Charlemagne

had already gathered a circle of poets and scholars and asked Alcuin to direct

the education of the royal and noble children. Charles I had conquered the

Lombards, so the first scholars he gathered were generally Italian. Charles was

first a warrior, but also sought to grow the cultural authority of his kingdom:

fortitudo et sapientia,

wisdom and might, an idea derived from the Virgilian

hero. At the invitation of Charlemagne, Alcuin became a leading scholar and

teacher at the Carolingian court, where he remained a figure in the 780s and

790s.

Since the

beginning of his reign, Charles had been focused on successfully fighting

Lombards, Saxons, and Saracens. In boyhood he would have been engaged in the

usual routine of hunting, riding, swimming, and the use of weapons. Yet he had

an eye for scholarship and the development of national culture.

Alcuin later

wrote to Charlemagne. I knew how strong was the attraction you felt towards

knowledge, and how greatly you loved it. I knew that you were urging everyone

to become acquainted with it and were offering rewards and honours to its

friends in order to induce them to come from all parts of the world to aid in

your noble efforts.

Alcuin left

York for Charlemagne’s court in 782. There is a suggestion that he was in York

for a while longer and didn’t leave for Charlemagne’s court until 786.

Alcuin's

joined the illustrious group of scholars whom Charlemagne had gathered around

him, at the heart of the Carolingian Renaissance. These scholars included Peter

of Pisa (a Latin Grammarian), Paulinus of

Aquileia, Rado, and Abbot Fulrad, and Paul

the Deacon (a Lombard historian). Alcuin would later write, the Lord was

calling me to the service of King Charles.

Charlemagne

gathered the best scholars from across his Kingdom and beyond, so that his

realm became more than just a centralised state, but adopted ideas from afar.

It seems that he made many of these men his closest friends and counsellors.

They referred to him as David, a reference to the Biblical king David.

Alcuin soon found himself on intimate terms with Charlemagne and the other men

at court, where pupils and masters were known by affectionate and jesting

nicknames. Alcuin himself continued to be called Flaccus and sometimes Albinus.

While at Aachen, Alcuin bestowed pet names upon his pupils, derived mainly from

Virgil's Eclogues. Alcuin loved Charlemagne and enjoyed the king's esteem,

but his letters reveal that his fear of him was as great as his love.

Alcuin

became master of the Palace School of Charlemagne in Aachen (Urbs Regale)

in 782. It had been founded by the king's ancestors as a place for the

education of the royal children (mostly in manners and the ways of the court).

However, Charlemagne wanted to include the liberal arts, and most importantly,

the study of religion.

|

The

centre of Charlemagne’s world into which Alcuin stepped. |

From 782 to

790 CE, Alcuin taught Charlemagne himself, his sons Pepin and Louis, as well as

young men sent to be educated at court, and the young clerics attached to the

palace chapel. Bringing with him from York his assistants Pyttel,

Sigewulf, and Joseph, Alcuin revolutionised the

educational standards of the Palace School, introducing Charlemagne to the

liberal arts and creating a personalised atmosphere of scholarship and

learning, to the extent that the institution came to be known as the school

of Master Albinus.

Alcuin

continued and built upon his methods of teaching which had been developed at York. He brought his Anglo Saxon teaching

techniques, including his riddles to liven up the rather dry Lombard teaching

methods. He made learning attractive. The collection of mathematical and

logical word problems, Propositiones ad acuendos juvenes

("Problems to Sharpen Youths") has been attributed to Alcuin.

Alcuin helped

Charlemagne to write official decrees, including those aimed at the development

of literacy across the Kingdom. He pioneered Charlemagne's Admonitio

generalis, a collection of legislation issued in

789 CE, which covered educational and ecclesiastical reform within the Frankish

kingdom. This framed what Charlemagne sought to achieve, including the

establishment of schools throughout Francia.

It was

generally felt that a successful kingdom required three classes of people -

warriors, workers, and those who would pray and converse with God, through an

understanding of wisdom, including by understanding Latin. Alcuin was called

upon to lead the development of the third of these classes.

Alcuin

became interested in Aachen in logic and abstract philosophical reasoning,

which were applied to theological questions, such as proving God’s existence or

defining his nature. He wrote a text on logic and revised the study of

Boethius’ works.

Alcuin engaged

with women in the court through his letters, in Francia, Northumbria and

Mercia. He saw engagement with women in correspondence as a means to influence

those in places of power. He engaged in correspondence on scholarly matters and

they exchanged gifts. These letters tell us about the politics of the court.

Women were also his pupils.

He wrote

poems. They were not always of the highest standard. They were often long

poems. He also wrote private poems in his letters.

He also

focused on theology and wrote treatises, including two against the Adoptionist heretics in Spain; and on the Trinity. He

revised the Latin version of the Bible. There was a revision of the liturgy.

Alcuin

established a new curriculum and teaching methods, which were then adopted

across Charlemagne’s empire. Royal decrees founded schools in each diocese and

monastery. There was a standardisation of handwriting through the adoption of

the new Carolingian miniscule.

He continued

the question and answer technique of learning, exemplified in "The

Disputation of Pepin the most Noble and Royal Youth with Albinus the Scholastic":

"What

is Language? "The Betrayer of the Soul."

"What

generates language? "The tongue."

"What

is the tongue? "The Whip of the Air."

"What

is Air? "The Guardian of Life."

"What

is Life? "The joy of the happy; the expectation of Death."

"What

is Death? "An inevitable event; an uncertain journey; tears for the

living; the proving of wills; the stealer of men."

"What

is Man? "The Slave of Death; a passing Traveller; a Stranger in his

place."

Alcuin

helped Charlemagne to lay the foundations for a European system of education,

which kept learning alive during the turbulent ninth and tenth centuries.

Alcuin’s

letters are a rich historical record of a time of profound historical

change in Europe. He revealed his inner thoughts and longing for Northumbria.

They tell much of the history of Northumbria. Alcuin’s letters make the late

eighth century the most documented period of this era. We learn personal

information about Alcuin from his letters, such as his favourite food which was

porridge with butter and honey.

Alcuin was the

most learned man anywhere to be found, according to Einhard's The

Life of Charlemagne (c. 817–833). Alcuin is considered among the

most important intellectual architects of the Carolingian Renaissance.

Among his

pupils were many of the dominant intellectuals of the Carolingian era.

Alcuin

established a great library at Aachen, for which Charlemagne obtained

manuscripts from Monte Cassino, Rome, Ravenna and other places. Books are

naturally attracted to centres of power and influence, like wealth and works of

art and all that goes with a prosperous cultural centre.

During this

period, he perfected Carolingian minuscule, an easily read manuscript hand

using a mixture of upper and lower case letters. Carolingian minuscule was

already in use before Alcuin arrived in Francia. However there was a diversity

of script between monasteries. Most likely Alcuin was responsible for copying

and preserving the script while at the same time restoring the purity of the

form. Alcuin spread correct Latin learning and common script which was mutually

legible. The script is the basis for the script used today and Times

New Roman font has

origins in the common text developed at this time. Each letter is distinctly

formed, separated and unique from another, so it became the tool for print many

centuries later.

The

Carolingian Miniscule script needed less time to write, and was probably an

adjunct of the new State educational project, the greatest ever undertaken in

the Western World. For such an enterprise the employment of an accelerated

script was an important element.

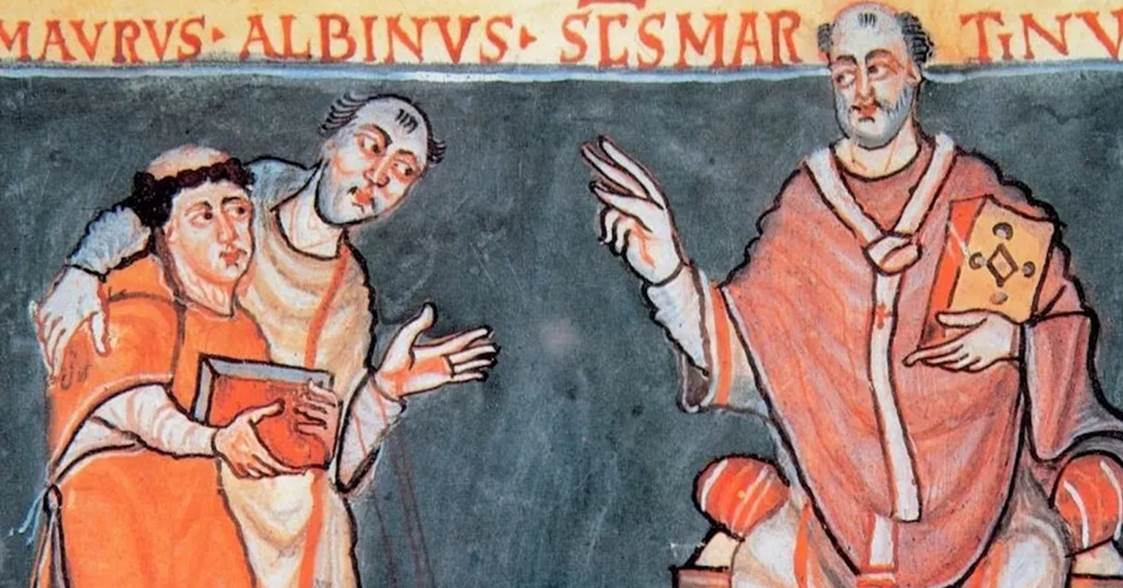

Rabanus

Marus (left), Alcuin (middle) and Archbishop Odgar of Mainz (right) (Carolingian manuscript)

At Aachen,

Alcuin composed a trialogue between a master, a 14 year of Frank and a 15 year

old Anglo Saxon. He also compiled a textbook of synonyms.

In this role

as adviser, he dissuaded the emperor's policy of forcing pagans to be baptised

on pain of death, arguing. Faith is a free act of the will, not a forced

act. We must appeal to the conscience, not compel it by violence. You can force

people to be baptised, but you cannot force them to believe. His arguments

seem to have prevailed. Charlemagne abolished the death penalty for paganism in

797 CE.

Alcuin

returned briefly to York in 789 CE. In 790 CE,

Alcuin again returned from the court of Charlemagne to York, and he lived at

York until 793 CE.

In 793 CE

Charlemagne invited Alcuin back to help in the fight against the Adoptionist heresy, which was at that time making

significant progress in Toledo, the old capital of the Visigoths and still a

major city for the Christians under Islamic rule in Spain. Alcuin is believed

to have had contacts with Beatus of Liébana, from the Kingdom of Asturias, who

fought against Adoptionism.

Alcuin had

been reluctant to leave York, but the first Viking attack at Lindisfarne in

that same year 793 CE, followed by Jarrow in 794 CE and mounting anarchy

culminating in the murder of the Northumbrian King Ethelred in 796 CE caused

Alcuin to remain in Francia, under the safety of the strong rule of

Charlemagne. His distress and horror at the fate of Lindisfarne in 793 comes

over very strongly in his letters both to the Bishop of Lindisfarne and the

Northumbrian king. Having failed during his stay in Northumbria to influence

King Æthelred in the conduct of his reign, Alcuin

never returned home.

As he

returned to Charlemagne's court, he wrote a series of letters to Æthelred, to Hygbald, Bishop of

Lindisfarne, and to Æthelhard, Archbishop of

Canterbury in the succeeding months, dealing with the Viking attack on

Lindisfarne in July 793. These letters and Alcuin's poem on the subject, De

clade Lindisfarnensis monasterii

(“On the destruction of the monastery at Lindisfarne”), provide the only

significant contemporary account of these events. In his description of the

Viking attack, he wrote, never before has such terror appeared in Britain.

Behold the church of St Cuthbert, splattered with the blood of God's priests,

robbed of its ornaments.

In his

letter to Hygbald, Bishop of Lindisfarne he wrote, When

I was with you, the closeness of your love would give me great joy. In

contrast, now that I am away from you, the distress of your suffering fills me

daily with deep grief, when heathens desecrated God's sanctuaries, and poured

the blood of saints within the compass of the altar, destroyed the house of our

hope, trampled the bodies of saints in God's temple like animal dung in the

street.

Alcuin saw

the Viking horrors as divine retribution for the moral decline of the

Northumbrian people.

In his

letter to Hygbald he wrote, what security is there

for the churches of Britain if St Cuthbert with so great a throng of saints

will not defend his own? Either this is the beginning of greater grief or the

sins of those who live there have brought it upon themselves.

Alcuin’s

lonely end

Alcuin was

pressured to return to York by the Archbishop of York

in 795 CE. Yet 796 CE was a year of misery and the death of Kings. Ethelred’s

successor was expelled after only a month. Alcuin decided to remain in Europe.

Charlemagne perhaps later gave Tours to Alcuin as compensation for his lost

lands in Northumbria.

Upon the

death of Abbot Itherius of Saint Martin at Tours, in 796 CE, a year of

devastation in Northumbria, Charlemagne appointed Alcuin to be abbot of Marmoutier Abbey, in Tours, in Western Francia, near

Orleans, where he remained until his death. Charlemagne did so with the

understanding that Alcuin should be available if the King ever needed his

counsel.

In 796 CE,

Alcuin was probably in his sixties.

Tours was

very well resourced. It was there that Alcuin encouraged the work of the monks

on the beautiful Carolingian minuscule script, ancestor of modern Roman

typefaces.

Whilst at

Tours Aluin wrote further works on the Trinity and another revised version of

the Bible. There was concern that the Bible text was becoming less pure. Tours

started to produce complete volumes of the Bible in one volume.

Much of the

surviving written material about Alcuin, including two thirds of his letters,

come from his period at Tours.

He was

increasingly drawn to a monastic life of prayer, fasting and stricter

observance.

Alcuin

suffered from fever (malaria), failing eyesight, and arthritis. His old friend

Eanbald died that year. There is a suggestion of melancholy in Alcuin’s years

at Tours. His letters suggest a sense of isolation. There is a sense of longing

for his former home. He wrote of struggling with the uncultured minds of Tours

and of boys pesting me with their little questions.

He wrote the

rather sad poem.

|

All the

beauty of the world is quickly upturned, And all

things in their time are transformed. For

nothing remains forever and nothing is immutable, Dark

night obscures even the clearest day. |

A

freezing winter cold strikes down gorgeous flowers, And a

bitter wind unsettles calm seas. On

fields where the pious boy once hunted deer, A tired

old man now stoops with his walking stick. |

Why do

we wretched ones love you, O fleeing world? Always

crashing down, you still flee from us. |

After the

death of Pope Adrian I in 795 CE, Alcuin was commissioned by Charlemagne to

compose an epitaph for Adrian. The epitaph was inscribed on black stone quarried

at Aachen and carried to Rome where it was set over Adrian's tomb in the south

transept of St Peter's basilica just before Charlemagne's coronation in the

basilica on Christmas Day 800.

Charles

became Emperor of the Holy Roman Empire on Christmas Day 800. Alcuin was at

Tours, which was distant from Charlemagne’s court. Charles had been peripatetic

as other kings of that time, but by about 795 CE he invested in his centre of

power at Aachen. In the build up to his coronation, Charlemagne toured his

Kingdom and went to Tours where he spent a considerable period of time with

Alcuin. So at this pivotal moment, Charles sought Alcuin’s advice, although

Alcuin did not travel with Alcuin to Rome as his health was failing.

The idea of

reviving the Western Empire, since the end of the Roman Empire and the

emergence of an empire in the East, must have been in the minds of both Pope

and King long before the stirring events of the year 800 CE. Alcuin, as adviser

both in temporal and spiritual affairs to the Frankish Court, was well aware of

the intended project.

The folk of

Ryedale and the lands around York, shared

vicariously through Alcuin in another pivotal moment in the evolution of

western civilisation.

O thou who passest

by, halt here a while, I pray, and write my words upon thy heart, that thou

mayst learn thy fate from knowing mine.

What thou art, once I was, a wayfarer

not unknown in this world. What I am now, thou soon shalt be.

Once was I wont to pluck earthly joys

with eager hand and now I am dust and ashes, the food of worms.

Be mindful then to cherish thy soul

rather than thy body, since the one is immortal, the other perishes. Why dost

thou make to thyself pleasant abodes? See in how small a house I take my rest,

as thou shalt do one day.

Why wrap thy limbs in Tyrian purple,

so soon to be the food of dusty worms? As the flowers perish before the

threatening blast, so shall it be with thy mortal part and worldly fame.

O thou who readest,

grant me in return for this warning, one small boon and say: 'Give pardon, dear

Christ, to thy servant who lies below.’ May no hand violate the sacred law of

the grave until the archangel's trump shall sound from heaven. Then may he who

lies in this tomb rise from the dusty earth to meet the Great Judge with his

countless hosts of light.

Alcuin, ever a lover of Wisdom, was

my name. Pray for my soul, all ye who read these words.

Legacy

Charlemagne

died in 814 CE and was succeeded by Louis the Pious, who had been influenced by

Alcuin’s teachings.

The Great

Library of York was either exported to mainland Europe or destroyed in the

devastating Viking attacks on York and Northumbria in 866 and 867. The school

and library of York were the finest in eighth-century Europe.

Go Straight to Chapter 4 – Anglo

Saxon Kirkdale

or

You will

find a chronology, together with source material about Alcuin.