Act 4

Anglo Saxon Kirkdale

c560 CE to c793 CE

Kirkdale and the Chirchebi

Estate and the birth of the English nation

Kirkdale Minster

only five kilometres south of the place that would come to be called Farndale,

and part of the same estate lands, was at the centre of a stable area for most

of the Anglo Saxon period. There is every reason to suppose that the

agricultural lands around Kirkdale and Kirkbymoorside, were the lands of our

ancestors for centuries.

|

This

is a new experiment. Using Google’s Notebook LM, listen to an AI powered

podcast summarising this page. This should only be treated as an

introduction, and the AI generation sometimes gets the nuance a bit wrong

(for instance the link between Kirkdale and Cornu Vallis is more opaque than

the AI summary picks up). However it does provide an introduction to the

themes of this page, which are dealt with in more depth below. |

|

As

a scene setter, you might enjoy a burst of Gregorian Chant |

Scene 1 – Order from Chaos

Fifth

Century CE

What

happened to the Roman estates and populations around Kirkdale

in the post Roman period is uncertain, but the interests of some of the

dominant landholders probably continued.

At nearby Beadlam, a large

number of coins date to the later fourth century CE and might reflect locally

secure conditions that may have been sustained for a period after the Romans

had left. The old Roman villa of Beadlam seems to

have continued as an important supplier of grain, evidenced by the presence of

a grain dryer from this time. Beadlam’s material

culture suggests continued post Roman activity. It cannot be said with any

certainty that Kirkdale had any association with Beadlam,

but its proximity might suggest its continued importance during this opaque

period.

It seems

likely that there may have been some religious site at Kirkdale in the late

Roman period, whether pagan or Christian or an amalgam of both. There is

evidence of an early burial, including an infant, to the north east of the

church. The first recognised structural phase at Kirkdale are some foundations

to the north of the church, which used blocks which might have been dated to

the Roman period, or might have been reused. This may have been part of a

detached structure, such as a funerary building or mausoleum.

Further to

the south, the Saxon invaders were given land to settle on the isle of Thanet,

perhaps to secure their help against the threat from the northern Pictish folk. It seems that the native population didn’t

make good their promises to the Saxons who punished them spectacularly in about

440 CE. The chaos of the period was reflected in the monk Gildas’ De Excidio Britanniae, The Ruin of Britain, who

wrote that the barbarians drive us to the sea, the sea throws us back on the

barbarians. Thus two modes of death await us. We are either drowned or

slaughtered.

There was a

tendency of those who had most embraced Roman living to flee northward and

westward, so that Wales and Cornwall became the land of the old Britons as the

pagan cultures of the Anglo-Saxons and the Jutes was planted in the east.

Nevertheless,

the evidence of Anglo Saxon culture in the area around Kirkdale

was slow to arrive. There is an absence of obviously culturally Anglo

Saxon grave goods in the early years of Anglo Saxon influence in eastern

England. In seems likely that the population in the area remained more

indigenous, at least for a while, rather than being immediately overwhelmed by

the Anglo Saxon incomers.

Over time

however, the population was gradually assumed into a new mixed Anglo Saxon

identity.

Inspired by

J G Frazer’s famous book, The Golden

Bough, a local archaeologist felt that the unusual characteristics of Kirkdale make it a likely location

for pre Christian ritual. It has been suggested that it might have been a Druid

site and it may have been a place of Anglo Saxon pagan influence for a while.

The Hodge Beck at Kirkdale dries up in times of hot weather, but continues to

flow under ground, to reappear downstream. The

quietness, beauty and timelessness of the site, and its disappearing water

trick, might explain its likely religious importance even before Christian

times.

The unusual

flow of the stream and the tranquilness of the place was something unusual that

was likely to have promoted an ancient reaction to the landscape, in its

variable physical setting of the beck. The spectacle of the waters of the Hodge

Beck on either side of the site of the later Church, which are periodically

lost to sight, provides a suitable location for pre Christian phenomenological

experience. The Hodge Beck was not the only example of disappearing water, with

similar occurrences at Lastingham.

Underground openings might have been used to communicate, using discolouration

by means of dyes, and meetings might have been timed to coincide with water

flow changes.

The location

of Kirkdale is accessible,

whilst not obvious. It could be accessed by long distance routeways, but its

location was aside and at the edge of the more populated vales.

If there

were pre Christian practices at Kirkdale,

then the shift from pre Christian to Christian might have been a more natural

one.

Deira

The Kingdom

of Deira emerged from the mid fifth century

and Bede’s Ecclesiastical

History of England (731 CE) suggested that there was a gradual

consolidation of smaller groups into larger units.

The absence

of hillforts and the non defensive nature of places

like Hovingham is reflective of a period of anarchy in which warlords fought

for dominance in a chaotic world.

By about 560

CE the area of eastern Yorkshire was generally subjugated by a single political

group. The name the Angles gave to the territory was Dewyr,

or Deira. Early rulers of Deira extended

the territory north to the River Wear and King Aelli

ruled Deira in about 569 to 599 CE.

The Anglo

Saxon poem Beowulf

was written between the seventh and tenth centuries CE, and reflects a

fantastical idea of a timbered hall and a ruing giving lord, who provided the

hall’s protection to the free warriors or ceorls, and the folk who

relied on their protection, from a wild and chaotic land which surrounded them.

|

The

people who dominated our ancestral lands |

|

A

Scandinavian saga which reflects the political structure of the sixth and

seventh centuries |

Scene 2 - Christianity

Conversion

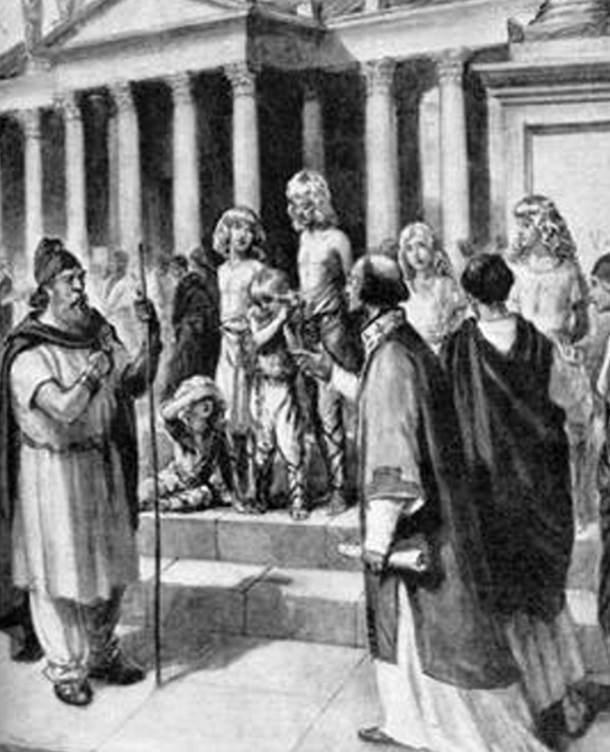

In Rome in

580 CE Pope Gregory saw fair haired slaves in the market and he asked about

them. The historian Procopius (500 to 565 CE) had previously described the

people of Brittia as Angiloi.

Gregory was now told that these slaves were Angles from the Kingdom of Deira,

the lands between the Humber and Tees, the realm of King Aelli.

Gregory was in a humorous mood that day, and he made three famous puns:

He mused

that they were not Angles, but angels, worthy of conversion, defining a

distinct nation that would one day be called England.

He amused

himself that the Deirans were de ira, or of anger, and that they were to be saved

from wrath.

And he

directed that Allelujah, a pun on the Deiran King’s name, Aelli, should

be sung in those parts.

His pun is

sometimes taken to define the origin of the English nation and Gregory

continued to class the Kingdoms of Britain as a single people. The story

represents the origin myth of the English nation.

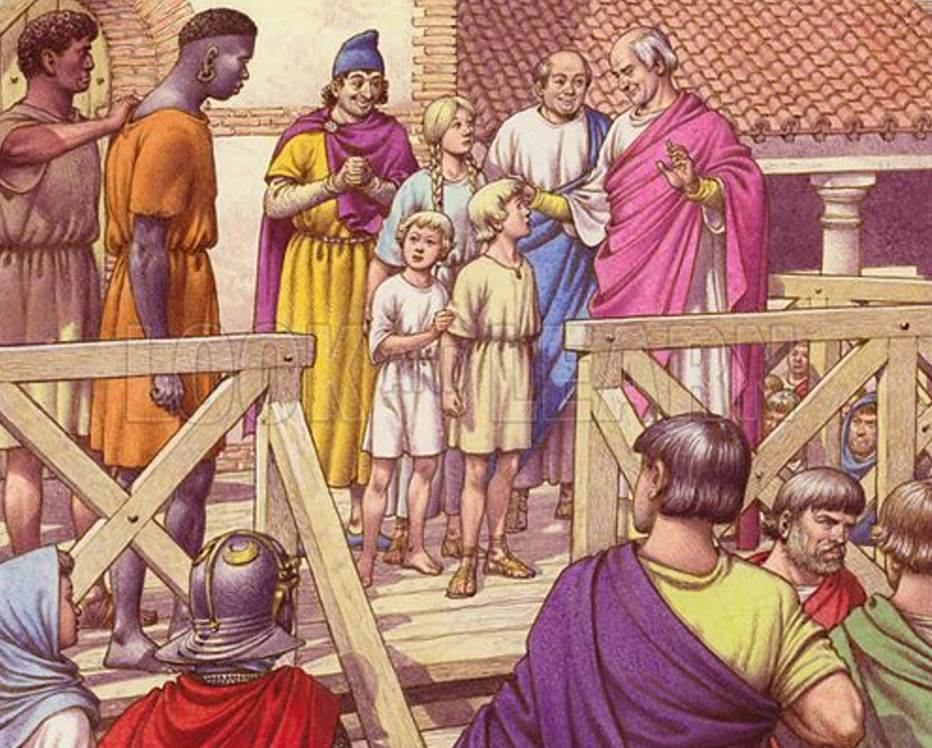

Bede told

the full story in his Historia

Ecclesia:

Nor must

we pass by in silence the story of the blessed Gregory, handed down to us by

the tradition of our ancestors, which explains his earnest care for the

salvation of our nation. It is said that one day, when some merchants had

lately arrived at Rome, many things were exposed for sale in the market place,

and much people resorted thither to buy: Gregory himself went with the rest,

and saw among other wares some boys put up for sale, of fair complexion, with

pleasing countenances, and very beautiful hair. When he beheld them, he asked,

it is said, from what region or country they were brought? and was told, from

the island of Britain, and that the inhabitants were like that in appearance.

He again inquired whether those islanders were Christians, or still involved in

the errors of paganism, and was informed that they were pagans. Then fetching a

deep sigh from the bottom of his heart, “Alas! what pity,” said he, “that the

author of darkness should own men of such fair countenances; and that with such

grace of outward form, their minds should be void of inward grace.” He

therefore again asked, what was the name of that nation? and was answered, that

they were called Angles. “Right,” said he, “for they have an angelic face, and

it is meet that such should be co-heirs with the Angels in heaven. What is the

name of the province from which they are brought?” It was replied, that the

natives of that province were called Deiri. “Truly

are they De ira,” said he, “saved from wrath, and

called to the mercy of Christ. How is the king of that province called?” They

told him his name was Aelli; and he, playing upon the

name, said, “Allelujah, the praise of God the Creator

must be sung in those parts.”

|

The

monk of Jarrow-Monkwearmouth who provides us with the primary source for the

history of Anglo-Saxon England |

Kirkdale, which lay at the centre

of Deiran lands, found itself firmly within the ambit

of England’s origin story, and the place of a church which soon afterwards was

dedicated to Pope Gregory.

In 597 CE

Gregory followed up on his direction at the slave market when he sent Augustine

to convert the Angli.

Augustine,

Prior of a Roman monastery, initially travelled to Kent on an ambassadorial and

religious mission, and he was welcomed by King Aethelberht.

English

identity began in a religious ambition. The English church would come to own a

quarter of cultivated land in England and reintroduce literacy at least amongst

the Church. Over the next few centuries, there grew a single and distinct

English church. After the Synod

of Whitby in 663 CE, it adopted Roman practices in its dogma and liturgy,

but it venerated English saints and developed its own character.

St Gregory

died on 12 March 604. He had been the bishop of Rome from 3 September 590 to

his death. The Gregorian mission was an ambitious project to convert the then

largely pagan Anglo-Saxons. Gregory was a prolific writer and the mainstream

form of Western plainchant, standardised in the late ninth century, was

attributed to Pope Gregory I and so took the name of Gregorian

Chant.

By the early

seventh century CE, there was a political structure across the area of modern

Ryedale, under King Edwin of Deira’s

peripatetic government, which held gatherings on estates where food was

consumed. Eoforwic,

the next of the many historic designations of modern York, was at its centre. Edwin converted to the

Christian religion, along with his nobles and many of his subjects in 627 CE

and was baptised at Eoforwic

in the first wooden church amidst the Roman ruins which was later replaced by a

larger stone church. The site of this first church was probably beside the old

Roman principia or military headquarters, to the north of the current

minster, in the current Dean’s Park.

When Edwin

died overall control of the Kingdom of Northumbria passed to the northern

Kingdom of Bernicia. Edwin’s successor King Oswald dominated the northern

region from Bamburgh. He gave Lindisfarne to his Bishop Aidan who built a

monastery there in 635 CE in the Iona tradition.

The Battle

of the Winwead was fought on 15 November 655 between

King Penda of Mercia and Oswiu of Bernicia, ending in the Mercians' defeat and

Penda's death. According to Bede, the battle marked the effective demise of

Anglo-Saxon paganism. It marked a temporary Northumbrian ascendency.

There

followed religious foundations in Eoforwic after the Battle of Winwead

in the Vale of Pickering and in the area

between Eoforwic

and Whitby, which included Lastingham, Kirkdale, Coxwold, Hovingham and

Kirby Misperton.

|

Deirian and Northumbrian York, a political,

cultural and educational Hub on the European stage |

|

The

founding of a Celtic Christian monastery by Cedd, close to the entrance to

Farndale |

Whitby was an important port. The first

monastery was founded in 657 CE by the Anglo-Saxon King of Northumbria, Oswiu,

sometimes called Oswy.

In 659 CE, Cedd, the elder brother of Chad, brought the

Celtic Christian traditions of Iona and Lindisfarne to found a monastery at Lastingham, at the site of an old Roman

nymphaeum. So Celtic Christianity had arrived only two kilometres from the

entrance to Farndale’s valley.

Bede, in his

Historia

Ecclesia recorded a small monastic community was founded at Lastingham under royal patronage, to

prepare an eventual burial place for Æthelwald,

Christian king of Deira, and to tame trackless moorland wilderness haunted by

wild beasts and outlaws.

|

A place of wild beasts and men

who lived like wild beasts Bede’s description of the wilderness of Farndale as a

place of dragons and wild beasts |

|

The founder of Lastingham |

Bede, wrote

of how Oidilwald, the son of King Oswald,

who reigned among the Deiri, finding Cedd to be a

holy, wise, and good man, desired him to accept some land whereon to build a

monastery, to which the king himself might frequently resort, to pray, and

where he might be buried when he died. So then, complying with the king's desires,

the Bishop chose himself a place whereon to build a

monastery among steep and distant mountains, which looked more like

lurking-places for robbers and dens of wild beasts, than dwellings of men; to

the end that, according to the prophecy of Isaiah, “In the habitation of

dragons, might be grass with reeds and rushes;” that is, that the fruits of

good works should spring up, where before beasts were wont to dwell, or men to

live after the manner of beasts.

So in this

place Cedd built his monastery, near to the

entrance to Farndale, vel bestiae commorari vel hommines

bestialiter vivere conserverant,

a land fit only for wild beasts, and men who live like wild beasts.

European

Union, Brentrance

There was

now a problem. There were two forms of Christianity competing in the same

lands, Celtic from Ireland via Iona and Lindisfarne and Roman from the papal

tradition in Rome. In a spirit that was to define English history for the next

thousand years, petty religious differences were enough to cause turmoil.

Different views on such things as the computes, the calculation of the

date of Easter, and the cut of the tonsure, the practice of shaving hair on the

scalp as a sign of religious humility, were issues of extreme aggravation.

However on

this occasion, a compromise was reached at the Synod at Whitby in 664 CE, only thirty kilometres

northeast of Kirkdale, when the

two traditions agreed to a reconciliation between the Celtic and Roman

Christian traditions, agreeing to adopt the Roman approach.

|

The

momentous agreement at Whitby, not so far from Farndale, which resolved

incompatibilities between Roman and Celtic Christian traditions, and placed

Britain onto the European stage |

As always, the

Europeans won the negotiation. The nation had chosen to join the European world

in the first days of its conception.

This was all

firmly within the sphere of Kirkdale’s experience, and

the people there likely lived in the same world where these momentous events

were unfolding. One day, far in the distant future, Whitby would become the home of several significant Farndale

families, including many seventeenth and eighteenth century mariners.

Scene 3 – Ancestral Lands

Saxon

Ghosts

At this time

in about 650 CE a Saxon princess was

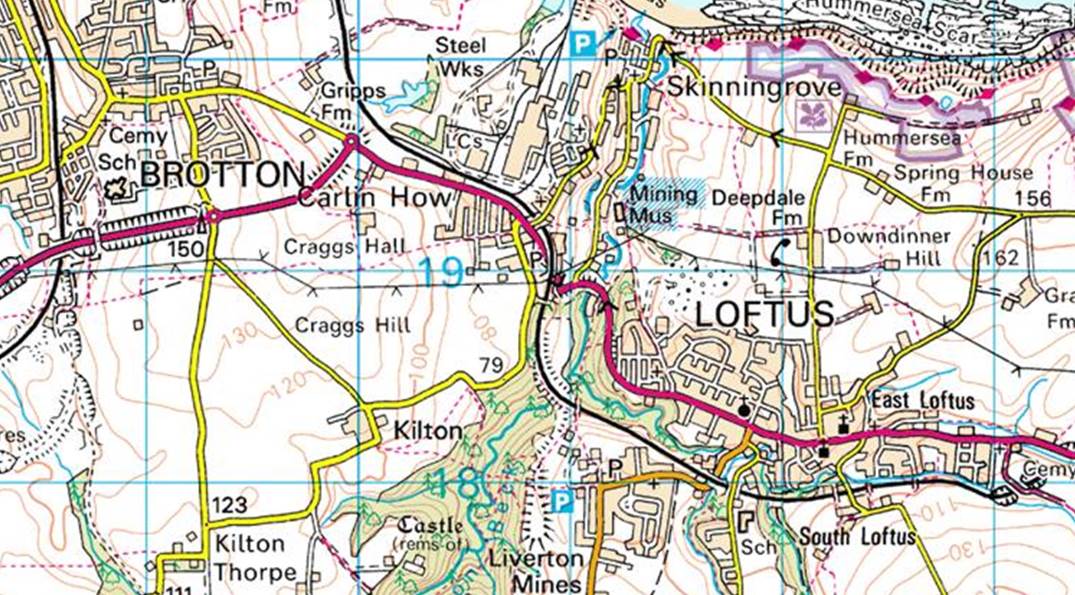

laid to rest at the place now called Street House near Loftus and Carlin How in Cleveland.

This was a

period of transition from paganism to Christianity in England. This location

would have been just within the northern border of Deira.

|

The

burial ground of a Saxon princess who lay for thirteenth centuries

overlooking the Hill of Witches where the Craggs line of Farndales would

later make their home |

The cemetery

was superimposed on an old prehistoric monument and there lay a high ranking

woman on a bed surrounded by 109 graves. The royal princess watched over Carlin

How, the hill of witches, for thirteen centuries until she was excavated in

2005. In Victorian times, the Craggs

line of Farndales would make Craggs Farm at Carlin How, their home, in this

place of Saxon ghosts.

Kirkdale

In about 685

CE, a minster was first built at Kirkdale,

possibly with close associations with Lastingham

and Kirkbymoorside.

It was

probably at this time that it was dedicated to St Gregory, the same Pope

Gregory who had put the land of the Angles onto the European political map, and

the dedication to the Roman pope, reaffirmed the new association with Rome and

the Pope recently agreed at the

Synod of Whitby. The Deiran monarchs became

closely associated with Rome, and with Gregory in particular. As did Kirkdale

itself.

|

Kirkdale

from its founding in about 685 CE to the beginning of the Scandinavian period

in about 800 CE |

|

Ornate sarcophagus lids and Saxon artefacts to be

found in Kirkdale Minster and embedded into its walls which will transport

you to the Eighth century CE |

Kirkdale became a religious and

political focal point of the relatively stable and prosperous lands in its

vicinity. So the distant ancestors of modern Farndales likely lived in this

place of profound influence on the future evolution of a nation.

There’s a

suggestion that Kirkdale may

have been the place known as Cornu Vallis, the horn of the valley. Cornu

Vallis was referred to as a place where Abbot Ceolfrith

of Monkwearmouth-Jarrow visited, and this might suggests links between Kirkdale

and the Tyne valley and Jarrow, where Bede

wrote his histories.

Kirkdale and Lastingham are about six kilometres apart

and have long been closely associated. It is likely that Kirkdale also had a close

relationship with the growing secular town of Kirkbymoorside.

The Kirkdale

archaeologists have found evidence of symbolism and the burial of special

dead, so in the middle Anglo Saxon period, Kirkdale likely had a special

significance to the local hierarchy of that time. Kirkdale might have been

attached to a local estate and the presence of the church at Kirkdale must have been a spiritual

force which consolidated local hierarchies, providing social cohesion. It must

have been an important expression of Christianity which would have created

local identity.

Kirkdale probably had an important

relationship by the eighth century with what was by then already perceived as

the past. This can be seen in its use of earlier Roman materials and as a

symbol of its close associations with Christian Rome, including through its

dedication to St Gregory. The archaeologists found blown glass, an object they

referred to as GL2, in the Roman fashion which might suggest a continuation of

techniques from the Roman period. There may have been an importance of Romanitas, a Latin word, coined in the third

century, meaning Roman-ness a link with things Roman, the collection of

political and cultural concepts and practices by which the Romans defined

themselves. Another artefact, called ST42, of the early ninth century may have

been imported from a significant, possibly Italian centre and was perhaps a

relic fragment.

There are

significant above ground grave structures, ST 7, ST8 and OM 3, likely

associated with elite members of society. Their position in the building might

have been focused with vibrant paint and possibly the play of light. The

symbolism of these finds was likely understood by an informed audience. One

design was probably reference to a chalice. There were probable theological

messages and symbolism of these finds has been linked to Bedean end of the

world millenarianism.

Our

ancestors lived amongst a rich cultural group near the centre of political

influence.

Cultural

and Educational powerhouse

In the 750s,

a young man called Alcuin came to the

cathedral church of York during the golden age

of Archbishop Ecgbert. Ecgbert had been a disciple of the Venerable Bede. The York school was known by

then as a centre of learning in the seven liberal arts, literature, and

science, as well as in religious matters and Alcuin

revived the school. In 781 CE, Alcuin was sent to Rome to petition the pope for

official confirmation of York's status as an archbishopric. On his way home, he

met Charlemagne in the Italian city of Parma. At the invitation of Charlemagne,

Alcuin became a leading scholar and teacher at the Carolingian court, where he

remained a figure in the 780s and 790s.

|

Alcuin

and the birth of modern education The

world of Ecgbert and Aethelbert, successors to Bede, and their pupil Alcuin,

who took York’s powerhouse of knowledge to the court of Charlemagne to

pioneer the European educational system |

|

|

So nearby York

was a centre of learning by the eighth century, with links to the court of the

Frankish King Charlemagne, soon to be crowned Holy Roman Emperor.

At the

northwest corner of the great agricultural lands of Pickering and York,

Kirkdale, our ancestral home, was firmly on the European stage in the eighth

century.

Anglo

Saxon Farming Community

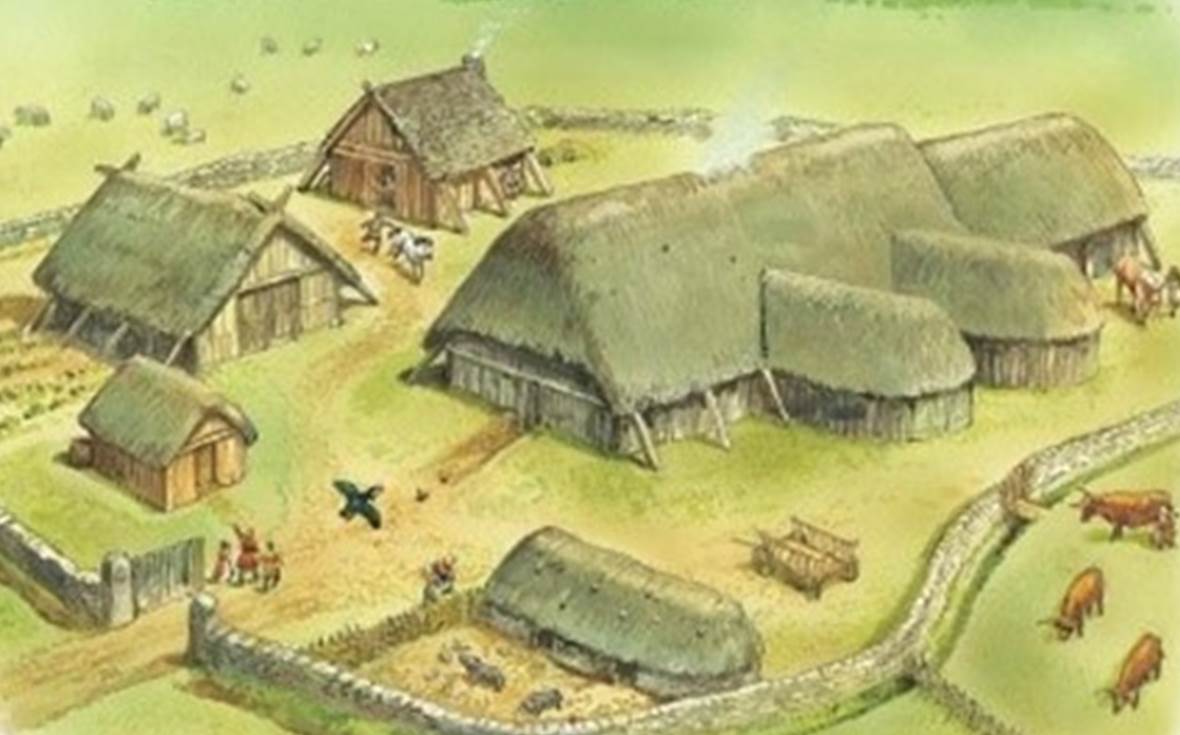

The

overwhelming majority of the English population of Anglo-Saxon England lived in

the countryside, grew crops, herded livestock and were self-sufficient.

The land had

been worked intensively during the Roman era. The villa owners grew rich by

exporting wheat to feed the armies across the Empire. Intensive cereal

production collapsed after the decline of Roman influence. Evidence of pollen

samples nevertheless suggests that secondary woodland did not expand

dramatically over the land where wheat had been grown. There may have been a

period during which sheep, cattle and pig rearing allowed the indigenous

population to draw their protein from secondary products including milk, butter

and cheese. Early Anglo-Saxon settlers may have focused their efforts on lush

meadows to provide winter fodder and herds may have grazed over wide tracts of land. The human population may have

been increasingly dispersed and often mobile, driving herds between summer and

winter grazing.

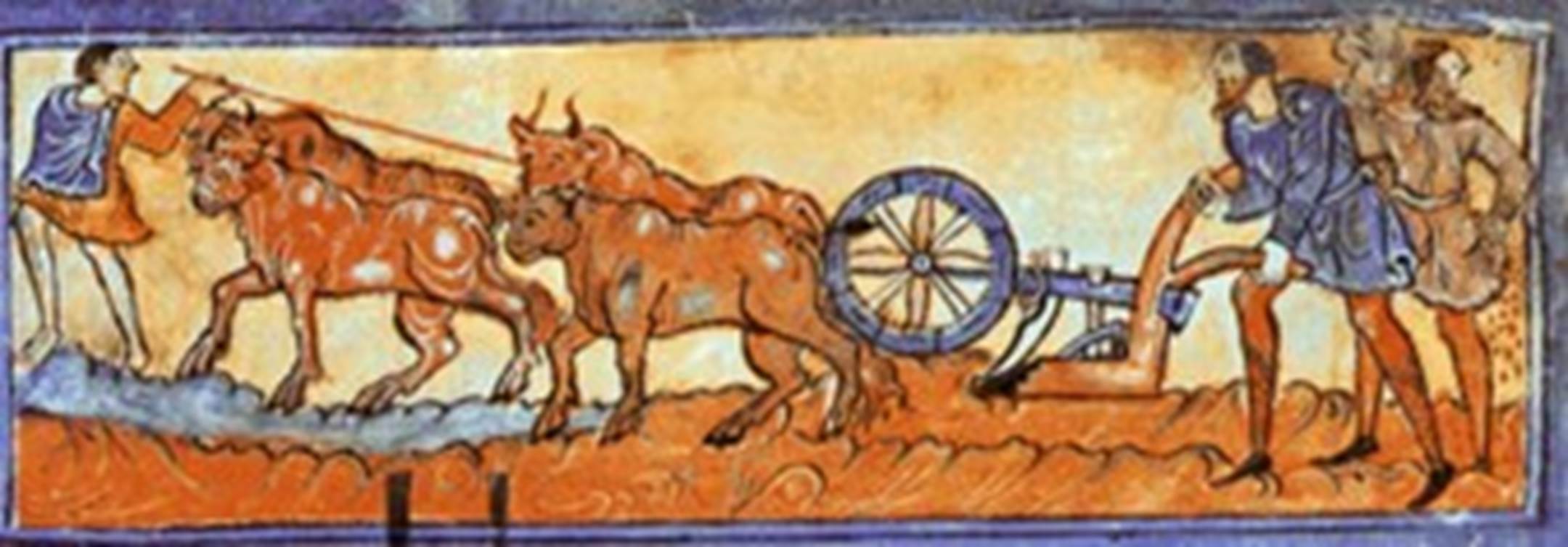

By the Middle Anglo-Saxon

period of the seventh to early ninth centuries, Anglo-Saxon farmers turned back

from pastoralism to rely increasingly on arable farming, growing wheat and

barley. This was probably the period when the open-field system materialised.

There is mixed evidence of the timing of the transition and no doubt it varied

across different regions.

Kirkdaleland

seems to have been a stable region, and the individuals who are the subject of

the Farndale Story, were likely to have been amongst the pioneers who ploughed

the land and reestablished arable crops in the Middle Anglo Saxon period.

Go Straight to Act 5 –

Scandinavian Kirkdale

or

If your interest is in Kirkdale then I suggest you visit the

following pages of the website.

· The church in Anglo Saxon Times

· The Kirkdale

Anglo Saxon artefacts

· The church in Anglo Saxon

Scandinavian Times

· The community in Anglo Saxon

Scandinavian Times

You might also like to read more

about:

· The Deira, Bernicia and

Northumberland

· Alcuin and the birth of modern

education

· Carlin How and Saxon witches

You will

also find a chronology, together with source material at the Kirkdale Page.