Rievaulx Abbey

The history of the Cistercian

monastery of Rievaulx, in whose Chartulary the name Farndale was first recorded

in 1154

There is a Rievaulx Chronology, with references to

source material.

If you’d

like to visit Rievaulx Abbey, here are some

notes to help you.

The

founding of Rievaulx

The

Cistercian order of white monks was founded at Cîteaux, near Dijon, in France, on 21 March 1098. The

monks had come from the Benedictine monastery of Molesme

which had been founded by a group of hermits who had sought a more austere

lifestyle, but which aspirations had been lost as Molesme had matured.

In the

remote forest of Citeaux, the monks agreed to a new approach, with simpler

clothing, bedding, diet and building structures. They paid particular attention

to Chapter

73 of the Rule which sought inspiration from the Desert Fathers and the

early monks of Thebaid.

Stephen

Harding, from Dorset, became their third abbot. In 1111 Stephen sent a group of

12 monks to start a daughter house in Chalon sur Saône

in La Ferté, founded on 13 May 1113. In 1112, a

charismatic Burgundinian nobleman, Bernard arrived at

Cîteaux with 35 of his relatives and friends to join

the monastery. Bernard led twelve other monks to found

the Abbey of Clairvaux, where he cleared the ground and built a church and

dwelling.

Cîteaux

soon had four daughter houses at Pontigny, Morimond, La Ferté and Clairvaux.

With

Bernard's influence, the Cistercian order began a period of international

expansion. As his fame grew, the Cistercian movement grew with it. The order

spread rapidly across Europe.

This new

monastic restoration was part of European monastic reform movements of the

twelfth century, which placed an emphasis on a return to an austere life and

literal observance of the rules set out for monastic life by St Benedict in the

6th century. These were not protests against the Rule

of St Benedict, but against how the rules had come to be interpreted since the

sixth century.

The rigour

of Cistercian religious life was the basis of its success. The order sought to

live according to the purest possible interpretation of the rule of Benedict.

Their services were dignified but simple, allowing more time for reading and

manual work. The Order’s art and architecture was austere. The Cistercians followed an ideal of manual

labour as part of their objective of self-sufficiency. This was an attempt at

isolation from the secular world.

The

Cistercians first came to England in 1128, first appearing at Waverley Abbey,

Surrey, founded by William Gifford, Bishop of Winchester. It was colonised with

12 monks and an abbot from Aumone in France. By 1187

there were 70 monks and 120 lay brothers at Waverley.

Walter

Espec, a prominent military figure, Lord of nearby Helmsley Castle and a royal

justiciar, founded the Cistercian abbey at Rievaulx in 1131. Espec was a huge

man with a penetrating voice. He was an active supporter of ecclesiastical

reform and had founded Kirkham Priory for the reformist Augustinian canons in

about 1121. At about this time a breakaway group from St Mary’s Abbey in York

established Fountains Abbey.

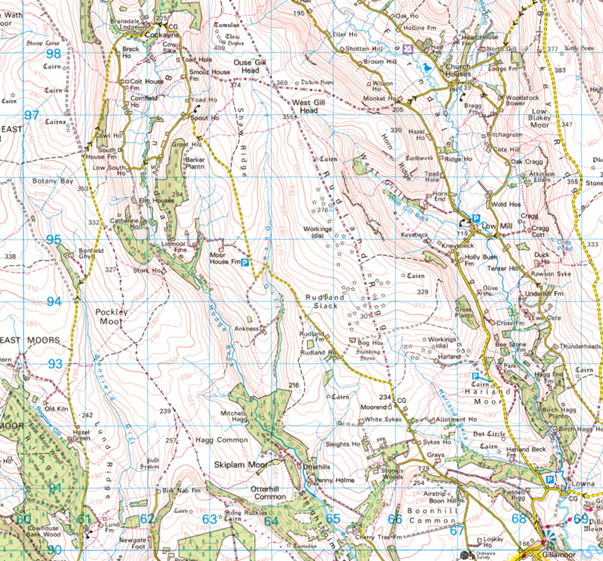

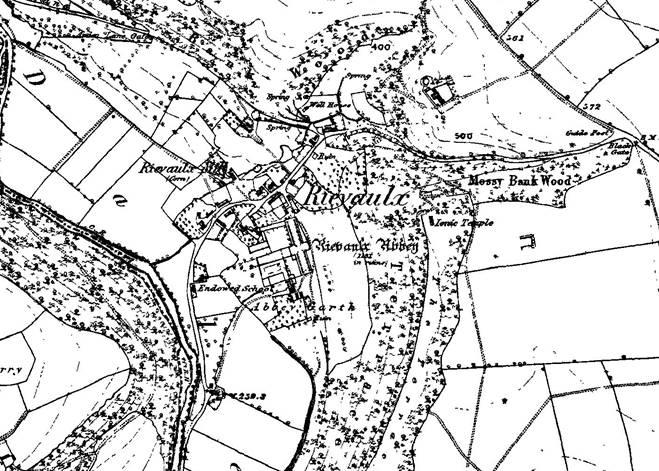

From its

position on the River Rye, the new Cistercian monastery became known as

Rievaulx, which later also gave its name to Ryedale.

William was

the founding Abbott from 1131 to 1145, with twelve monks. The continuous and

monotonous round of prayer and study, separated from the outside world,

attracted folk from elite classes of society.

The first

buildings at Rievaulx were temporary wooden structures.

William

dispatched colonies to establish daughter houses at Warden in Bedfordshire and

Melrose in 1136, Dundrennan in 1142 and Revesby in

1143.

An earlier

monastery was founded at Melrose

by Aidan of Lindisfarne. King David I wanted the new

abbey to be built on the same site, but the Cistercians chose a new site with

better land. It was said to have been built in ten years. Its first community

came from Rievaulx Abbey.

An early

agreement was reached between the monks of Rievaulx and the canons of

Augustinian Kirkham

Priory. Kirkham was to cede to Rievaulx the whole of Kirkham, with its

church and associated lands, a wagon and 100 sheep. In return Rievaulx as

patron was to give them alternate land at Linton and Hwersletorp.

The prior of Rievaulx and his sui auxilarii

(assistants) were to build them a church and other monastic

offices on this new land. It seems that it was intended that Kirkham

should become Cistercian, with Rievaulx as its mother house. Those who disliked

this arrangement were to have a new house built for them elsewhere. Walter

Espec was still alive when the agreement was drawn up. He preferred the

Cistercian order and indeed became a monk at Rievaulx later in his life. It

seems that Espec wished that his three foundations, Kirkham, Rievaulx, and

Warden should be of the Cistercian order. The agreement, however, fell through.

The early

white monks laboured in the fields, diverted streams through monastic

water-systems, hauled timber from the woodlands, and spent significant time in

physical, non-scholarly activities, scheduled to alternate with the appointed

hours of formal religious devotions.

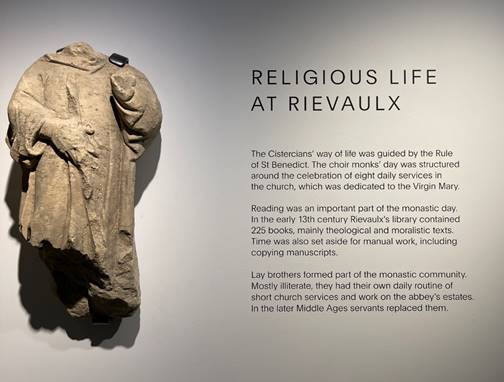

The choir

monks’ day was structured around the celebration of eight daily services in the

church which were dedicated to the Virgin Mary. Reading was an important part

of the monastic day. Time was also set aside for manual work including copying

manuscripts.

Lay brothers

formed part of the monastic community. Mostly literate, they had their own

daily routine of short church services and work on the Abbey estates. In the

later Middle Ages servants replaced the lay brothers.

The arrival

of the reform-minded Rievaulx community sent shockwaves through the older

Benedictine houses of the north. The foundation at Rievaulx was carefully

planned by Bernard of Clairvaux to spearhead the monastic colonisation and

reformation of northern Britain.

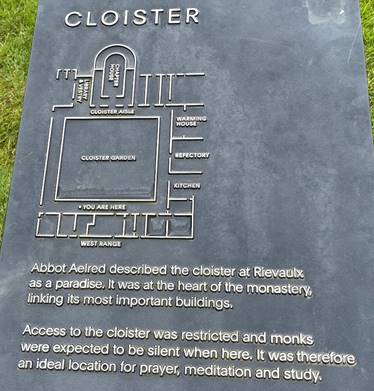

In the late

1130s Abbot William began the construction of stone buildings around the

present cloister. The northern part of his west range, which housed the abbey’s

lay brothers, still survives, as does a fragment of the south range.

It

was not long before individual monasteries began to engage commercially with

the secular world beyond their boundaries. Although the new monastery was given

limited land by its founder, it soon received other donations of land of

considerable extent and value, so that within half a century from the

foundation of the abbey it had acquired possession of some 50 carucates of land

besides other property. The number of monks who first came to Rievaulx must

have largely exceeded the number usually sent to form a new convent, and

Rievaulx came to be a source from which other Cistercian monasteries might

develop.

Aelred

Aelred

was the son of Eilaf, a priest from Hexham. He was a Northumbrian of old

English descent raised at court in Scotland. Aelred had become a steward in the

court of David I of Scotland. During a visit to Yorkshire

he was welcomed at Walter Espec’s castle at Helmsley and was taken to meet the

monks at Rievaulx. As a young man he joined Rievaulx as a postulant in 1134.

Abbot

William made him a member of the Council and he was sent on diplomatic missions

including to Rome. He became novice master of a community which quickly grew to

about 300. He then became abbot of Revesby in Lincolnshire, a daughter house of

Rievaulx. Five years later in 1147, he became abbot of Rievaulx. He continued

as abbot until his death in 1167.

Aelred was a

significant writer and biblical scholar. At its height in the mid twelfth

century (exactly the time of the Farndale

interest) Rievaulx was home to 140 monks and 500 lay brothers and servants.

Spiritually and architecturally Rievaulx was the most important Cistercian

Abbey in England.

Aelred wrote

extensively. He described the abbey lifestyle.

Our food

is scanty, our garments rough, our drink is from the stream and our sleep is

often upon our books. Under old tired limbs there is

but a hard mat. When sleep is sweetest, we must rise at the bell’s bidding. Self will has no scope. There is

no moment for idleness or dissipation. Everywhere peace, everywhere serenity,

and marvellous freedom from the tumult of the world. To put all in brief, no

perfection expressed in the words of the gospel or of the apostles or in the writings

of the fathers, or in the sayings of the monks of old is wanting to our order

and our way of life.

The monk

Walter Daniel, a contemporary of Aelred, wrote a biography of his Abbot, The

Life of Ailred of Rievaulx. This described how under Aelred’s

compassionate leadership Rievaulx became “the home of party and peace, the

abode of perfect love of God and neighbour.” Aelred’s vision of monasticism

was founded on a spiritual love for his fellow monks.

Monasticism

evolved considerably during the Middle Ages. The Abbey 's magnificent buildings

provide evidence of these changes. Spiritually and architecturally Rievaulx was

the most important Cistercian Abbey in England.

This

increase in numbers required much larger buildings. Many of the standing

buildings today date from Aelred’s rule. A monumental church was begun in the

late 1140s, one of the earliest great mid twelfth century Cistercian churches

in Europe.

Rievaulx

attracted the support of important benefactors, many of whom were buried here.

They believed that burial at the Abbey and prayers of the monks would hasten

the passage of their souls through purgatory to heaven.

The abbey

lies in a wooded dale by the River Rye, sheltered by hills. The monks diverted

part of the river several yards to the west in order to

have enough flat land to build on. They altered the course of the river twice

more during the twelfth century. The old course is visible in the grounds of

the abbey. This is an illustration of the technical ingenuity of the monks, who

over time built up a profitable business mining lead and iron ore, rearing

sheep and selling wool to buyers from all over Europe.

Rievaulx was

the hub of a trade network but extended as far as Italy. Fleeces from the

Abbey’s flocks were highly prized and Rievaulx became wealthy.

Abbot

Aelred's monastery at Rievaulx in the mid Twelfth Century

Aelred was

credited with several characteristics associated with saints including an

ability to perform miraculous cures. Rievaulx monks regarded Aelred as a saint

almost from the moment of his death in 1167.

Economic

activity

Like other

monastic orders, the monastery at Rievaulx accepted gifts of land on which to

build their monastery, farm sheep for wool and grow food, or from which to

extract minerals, quarry stone and retrieve timber for building and repairs.

However, initially at least, they would accept only undeveloped land because

managing tenanted land would entail an engagement with the secular world which

monastic isolation was designed to avoid.

Significant

land grants were given to the monasteries. Rievaulx soon had a great swathe of

properties, throughout Ryedale and stretching to Teesmouth

and Filey.

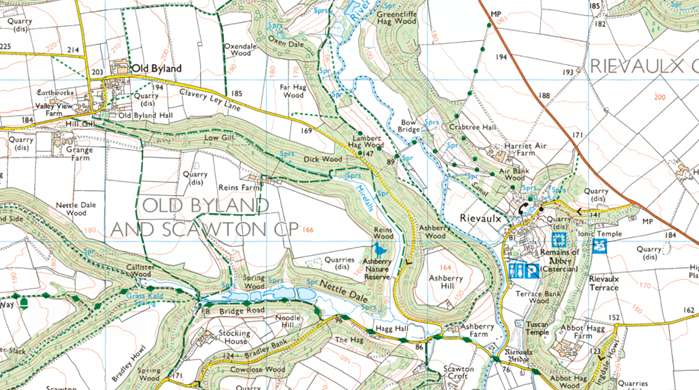

In 1143

Roger de Mowbray granted Old

Byland to the convent of monks who had left Calder, intending that they should

build their monastery on the south side of the River Rye, but the site was too

near Rievaulx, and each house heard the bells of the other. The monks of Byland

moved further off, but the lands of the two houses were still close, and to

avoid possible disputes an agreement was entered into between Aelred, Abbot of

Rievaulx, and Roger, Abbot of Byland, in about 1154. This agreement began by a

mutual engagement of masses and prayers for deceased brothers of the two houses

and a combined strategy for protection against oppression or misfortune by

fire. The agreement then defined the relations of the two houses regarding

their adjoining lands, both in the immediate vicinity of the two houses and

their properties at a distance, where they adjoined each other. As to the

homelands, the Byland monks conceded to their brethren of Rievaulx that they

should have their bridge so constructed that it should hold back the wood they

conveyed by the River Rye, and also a road from the bridge through the wood and

field of Byland to a place called Hestelsceit,

18 feet in width, which the monks of Byland were to keep in repair. They were

to have mutual rights on each others' banks of the

river.

Over time

Rievaulx received grants of land totalling 6,000 acres. Most grants of common

pasture to the monasteries were made early. Rievaulx soon acquired land in

Welburn (1138 to 1143); Wombleton (1145 to 1152);

Farndale (pre 1155). Some grants of sheep pasture were

very large and caused the monastery to set up their granges nearby.

The name Farndale, first occurs in

history in the Rievaulx

Abbey Chartulary in a Charter granted by Roger de Mowbray to the Abbot and

the monks of Rievaulx Abbey in 1154. By it Roger bestowed upon the Monastery, ‘….Midelhovet, that clearing in Farndale where the

hermit Edmund used to dwell; and another clearing which is called ‘Duvanesthuat’ and common of pasture in the same valley of

Farndale….’

The monks

had a large area given to them at Skiplam, north of Kirkdale, by Gundreda de Mowbray.

This allowed for expansion since it was this grant that included Farndale Head

and Bransdale, about 18 square miles of dale pasture land.

In some

areas the monks might not have been clearing new land in an area entirely

unused. Although the extent of existing settlement and cultivation was small,

it had existed in some of these places. Some of the land might have gone out of

cultivation. The monks’ task would then have been one of reestablishment rather

than the colonisation of new land.

At Skiplam the greater part of the area had never been settled

for or tilled, but there is evidence that the monks began to work some areas of

this land which had already or recently been cultivated. Gundreda’s

grant, for instance included de culta terra

(“of cultivated land”), as well as a grant ubi culta

terra deficit versus aquilonem (“where the

cultivated land declines towards the north”). Of course

the subsequent work of the monks in all these places did result in a very great

extension of the cultivated land. However the

Cistercians, whilst solitaries, seem to have benefitted to some extent from

previous lay efforts. In fact, it was largely the success or failure of lay

farmers in a particular area which helped the monks to see the potentialities

it offered them.

The granges

had easy access to two types of pasture - moorland and valeland.

Skiplam, for instance, had extensive pasture in the

moorland dales, only a few miles north. There was the saltum (rough

pasture) of Farndale Head and common pasture in Farndale and Bransdale. It had,

too, the meadow of the clayland at its disposal. This

was even nearer, being no more than three miles to the south. The plough teams

from Skiplam could easily pasture at Welburn, where

the monks had common pasture rights, or at Rook Barugh, Muscoates,

and several other places, just as the animals from Griff went to Newton grange

for pasture. The limestone hills had then a great deal to recommend them for

the observant eyes of the monks.

The

Cistercians became active farmers. During the twelfth century one of the gifts

to Rievaulx was a pasture with sixty mares and their foals. As well as sheep,

they were engaged in rearing pigs. Aelfred’s letters suggest that the monks

grew flax which they made into linen at Rievaulx. There may have ben a tannery

during Aelred’s abbacy.

In 1159 a

rescript from Pope Alexander III to the Bishop of Exeter, the Abbot of St.

Mary, York, and the Dean of York directed them to see that amends were made for

the spoliation of the property of the abbey of Rievaulx by certain persons

named. Strangely, the offenders were some of the chief benefactors of the

abbey. Robert and William de Stuteville had been guilty of

various acts of depredation, and the pope ordered that within thirty days they

were to make restitution, under pain of excommunication. Seven other offenders

are named, including Roger de Mowbray

and his son Nigel.

By 1160 the

Abbey was home to 640 men.

The accumulation

of lands and rights by the monasteries was rapid. At Rievaulx, for example, the

greater parts of the lands were acquired and a very

large number of granges established by the end of the twelfth century. Even by

1170 the monks had required all Bilsdale, Pickering

Marshes, the parts of Farndale and Bransdale, the Vills of Griff, Tileson, Stainton, Welburn, Hoveton,

and the lands of Hummanby, Crosby, Morton, Wedbury, Allerston, Heslerton, Folkton, Willerby, Reighton.

Some donors

had apparently not bargained for such a rapid increase in monastic possessions.

It came as a shock to find that the monks were not “all that was simple and

submissive; No greed, no self-interest …” The result was that men like

Roger de Mowbray, Robert de Stuteville, Everard de Ros and

other great Lords, formerly great donors and foundations, began unsuccessfully,

to evict the monks from certain lands, but monastic expansion continued.

The

Cistercian abbey of Rievaulx established ‘granges’, farms which they owned and

managed themselves, where they grew food and raised sheep, cattle and horses,

as well as producing various raw materials. Beyond supplying the monastic

community at the mother house with its needs, they were expected to produce a

surplus which could then be marketed to yield an income. The monks and lay

brothers tended to site their granges away from villages. Monastic farms became

a separate economic force. The sheep grange was dominant in Yorkshire with many

examples, including at Farndale, of donations of rights to pasture a fixed

number of sheep.

Traders in

wool outside the monasteries were interested in buying up any surpluses the

monks produced from their sheep-farming. Cistercian houses such as Byland Abbey

began to deal in the market, and built ‘woolhouses’ where not only was wool stored but facilities

were provided for merchants to come and inspect the monks’ surplus produce and

negotiate their price. Byland Abbey,

distinguished for its wool production, for a time maintained a woolhouse in York, a city

which had mercantile links by the Ouse and Humber rivers to continental

markets.

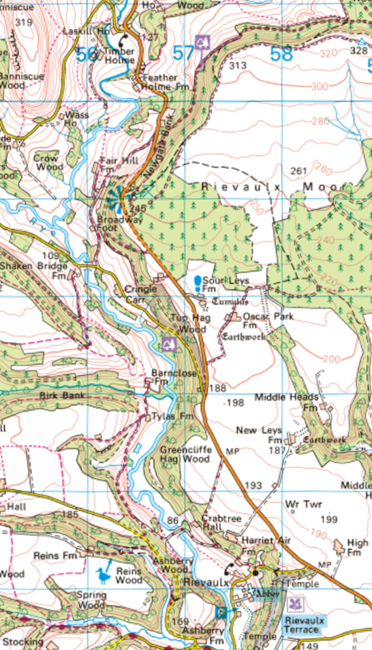

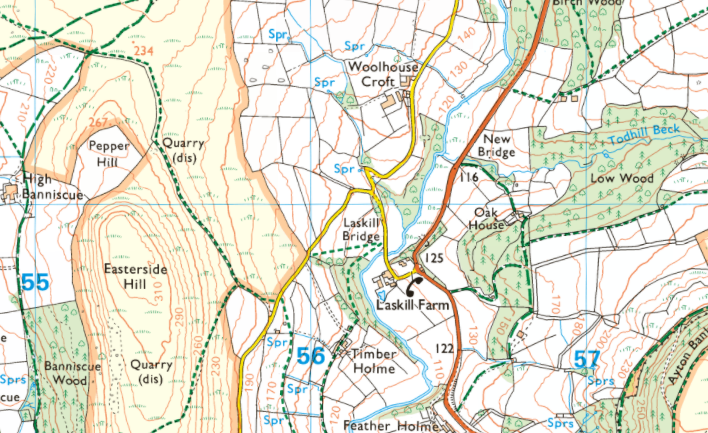

There was a

Rievaulx woolhouse at Laskill

north of Rievaulx at the mouth of Bilsdale.

The site was

excavated in 1855. Water-leaf capital and corbel survivals suggest a late

twelfth century date. The vaulted undercroft probably

had a timber-roofed upper floor providing accommodation in season for visiting

wool-buyers. Edward II visited the woohouse in the

late summer of 1323, during a hunting trip, when it was described as Glascowollehous.

In around

1220 the east end of the church was rebuilt to provide a magnificent setting

for Aelred’s mortal remains or relics. These were placed in a golden silver

shrine, which stood on a beam above the high altar. The Abbey also possessed “a

belt of Saint Aelred’, which was tied around the stomachs of local women

during childbirth in the belief that it would aid their ease their pain and

suffering.

Later

History

In the early

13th century Rievaulx’s library contained 225 books mainly theological and

monastic texts.

The period

from about 1270 to 1400 was one of change and often difficulty. In the late

13th century epidemics devastated the abbeys flocks, leaving the monastery in

debt.

Rievaulx was

badly affected by warfare between England and Scotland and was pillaged by the

Scots in 1322. The Battle

of Byland took place on 14 October 1322 and must have greatly affected the

two abbeys of Rievaulx and Byland, but nothing certainly is known as to what

happened to Rievaulx in consequence of it. The encounter between the English

and the Scots took place on the high ground between the two houses and near

Byland. The English king was at Rievaulx and not Byland Abbey when he received

news of the defeat of his army. He fled at once to York

for safety, leaving, according to the chronicler of Lanercost,

his silver plate and a great treasure behind him at Rievaulx. This fell into

the hands of the Scots, et monasterium spoliaverunt.

The Black

Death in the middle of the 14th century took a heavy toll. In 1380 there were

only 15 monks and 3 lay brothers at Rievaulx.

In 1406 a

glimpse of the life in the abbey was provided by a mandate of Pope Innocent

VII, which stated that each monk in priest's orders was bound in turn for a

week at a time to sing mass solemnly (alta

voce ad notam) at the high altar, and to say the invitatory, such monks

being called ebdomadarii, but that Thomas

Beverley had an impediment of tongue, on account of which he could not do this

becomingly, so he was granted a dispensation from performing the office.

The

concluding years of Rievaulx were difficult. The abbot, Edward Kirkby, was not

ready for impending religious charges against the monasteries. On 1 September

1533 the king's commissioners complained that Abbot Kirkby had written a letter

' to the slaundare of the kinges

heygnes, and after the kynges

lettars receivyed, dyd imprison and otharways punyche divers of hys brethren whyche ware ayenst him and hys dissolute liwing; also dyd take from one of the

same, being a very agyd man, all hys

money.' Further they complained that 'all the cuntre makythe exclamations of this Abbot of Rywax,

uppon hys abhomynable liwing and extortions

by hym commyttyd, also many

wronges to divers myserable

persens don, whyche

evidently duthe apere by bylles corroboratt to be trwe with ther othes corporal, in the presens of

the commissionars and the said abbott

takyn, and opon the same

xvi witnessys examynyd, affermyng ther exclamations to be

trwe.' The commissioners concluded by stating that

they had ' remowyed hym

from the rewlle of hys abbacie and admynistration of the

same.'

Rievaulx Abbey

was shut down on 3 December 1538, as part of the Dissolution of the Monasteries

under Henry VIII. By this time Rievaulx’s community had shrunk to only 23

monks.

The

monastery was sold to Thomas Manners (d1543), 1st Earl of Rutland, who was

closely associated with the royal court. Rutland dismantled the buildings,

reserving the roof leads and the bells for the King. His steward at nearby

Helmsley, Ralf Bawde, recorded the process of

dismantling, leaving remarkably detailed accounts of the process and the form

and contents of individual buildings.

One of the

buildings within the abbey precinct was called ‘the Yron

Smiths’. Abbey records show that this was a water-powered forge used for

making the many objects from iron for the monastery, from nails to tools and

cutlery. Under Rutland the ironworks grew in scale. By 1545 enough iron ore was

being smelted to keep four furnaces busy. The vaulted undercroft

of the refectory was used as a dry place to store the charcoal used to heat up

the ore to the temperature required to extract molten iron.

The

ironworks continued to grow throughout the later sixteenth century, with the

addition of a blast furnace in 1577, possibly the first in the north of

England.

A new forge

was built at the south end of the old monastic precinct, which was re-equipped

between 1600 and 1612.

By the

1640s, local supplies of timber for charcoal were all but exhausted, and the

ironworks was closed.

Rievaulx

1857

or

Go Straight to Chapter 2 – Game of

Thrones