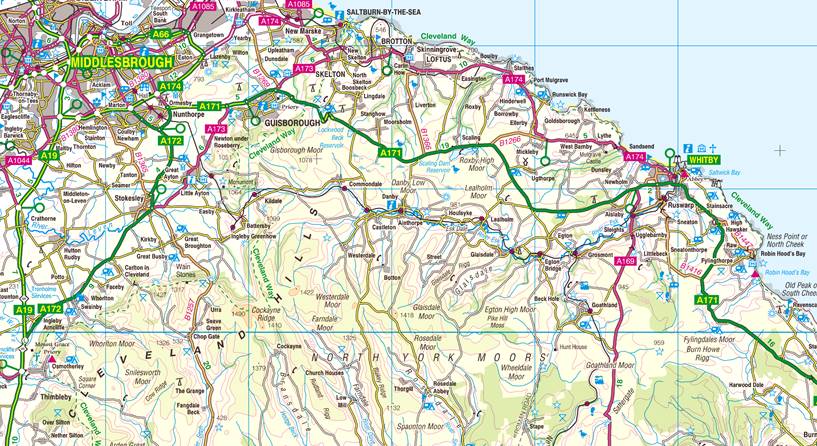

The Story of Farndale to 1500

The story of the dale of Farndale

told by those who still bear its name

|

This

is a new experiment. Using Google’s Notebook LM, listen to an AI powered

podcast summarising this page. This should only be treated as an

introduction, and the AI generation sometimes gets the nuance a bit wrong. It

makes an error in suggesting that stone tools were made 20,000 years ago

above Farndale, as this could not have been earlier than 10,000 years ago and

Joan of Kent was Edward I’s granddaughter and was not killed in the Black

Death. However it does provide an introduction to the themes of this page,

which are dealt with in more depth below. Listen to the podcast for an

overview, but it doesn’t replace the text below, which provides the accurate

historical record. |

|

The dale

comes to life

Until the

early thirteenth century the area that came to be known as Farndale was a wild

and remote forested location, occasionally used for hunting, from which small

parcels had been granted to monks as a source of timber. An organised campaign

of slashing and burning the land for cultivation began in the thirteenth

century.

Over time,

people started to adopt names which described them by place or occupation. The

villeins of Farndale were our earliest ancestors, and included individuals such

as Nicholas de

Farndale, the first personal name linked to Farndale, Peter de

Farndale, Gilbert

de Farndale, William

the Smith of Farndale, John

the Shepherd of Farndale, Roger

milne (miller) of Farndale and Simon the miller of

Farndale.

That process

signalled the start of a spread of our ancestors out of Farndale to the

surrounding lands. At that time, such movements were no doubt as bold and

significant as later family migrations to Australia, Canada and New Zealand. We know for

instance that De Willelmo

de Farndale moved to Danby and De Johanne de Farndale

moved further afield to Egton.

In this

genealogical exploration of the Farndale family,

we are therefore most interested in Farndale the place before about 1400. After

that, those who chose to define themselves as of Farndale were generally

those who had moved on to live in other places. By the fifteenth century there

were no members of the family still living in Farndale, and none have returned.

Nevertheless

an exploration of the earliest history of Farndale the place is integral to our

family story. It is our beginnings. It is the cradle of the Farndale family. It

is where it all started.

The name

Farndale seems to come from the Celtic farn, or fearn meaning fern

and the Norwegian dalr, meaning dale. It was the dale where

the ferns grew.

Of course

whilst Farndale is today dominated by moorland bracken and ferns, ferns are

naturally a woodland plant, so it must have been the ferns of the forested

Farndale which gave rise to its name, which it had adopted by 1154. Perhaps it

was Edmund the Hermit who roamed Farndale in the early twelfth century and must

have known the valley intricately, who first chose its name.

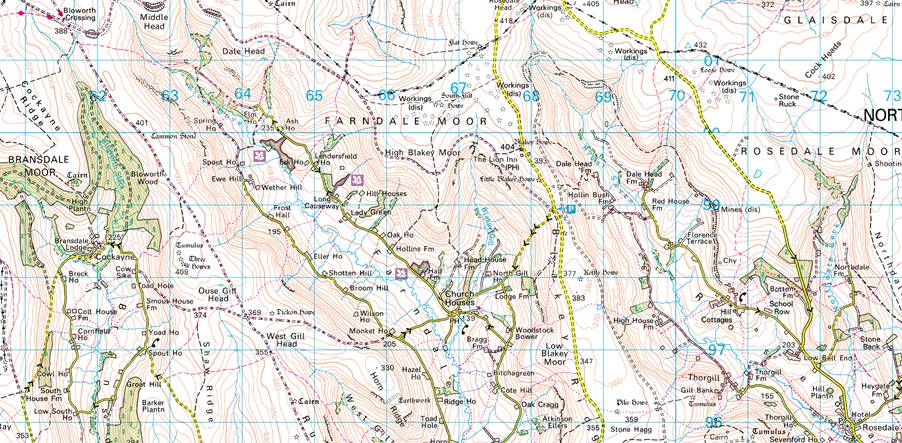

Neolithic,

Bronze Age and Iron Age Farndale

Neolithic

microlith sites have been found on the moors at Bransdale and Farndale

including flint and stone chippings and basic tools. The area between the heads

of Farndale and Westerdale is one of the richest series of flint sites in

Britain. Large collections have been made at Common Stone, near Ash House, and

at Blakey Howe. Petit

tranchet microliths or arrowheads, have been found at the Farndale

sites.

Sander van

der Leeuw has identified the real significance of the evolution of

neolithic tool making in expressing the new cognitive ability of the human

brain. The simplest early tools had natural points and edges. Our Palaeolithic

ancestors then learned to create a sharp edge, by flaking off part of the stone

by hitting it against another surface. They then started to create tools with

multiple flaked edges. By 20,000 YPB on a global

scale, with the new technology spreading more recently in places like the

moors, they mastered tool making in three dimensions, by removing flakes at

specific angles to create sharpened points, involving the intersection of three

planes. Early stone tool making found its ultimate expression in the Levallois Technique,

which involved a mental reasoning and understanding of multiple stages in

making a tool. This ability emerged from the increased cranial capacity of the

human brain from about two million years ago, which in turn expressed a new

uniquely human ability for planning and long term thinking. Van der Leeuw found

advances in stone knapping

techniques reflected a step change in the human mind.

In other

words these very earliest expressions of human activity on the edge of

Farndale, are representative of a global evolution of humans into thinking,

reasoning and forward thinking people.

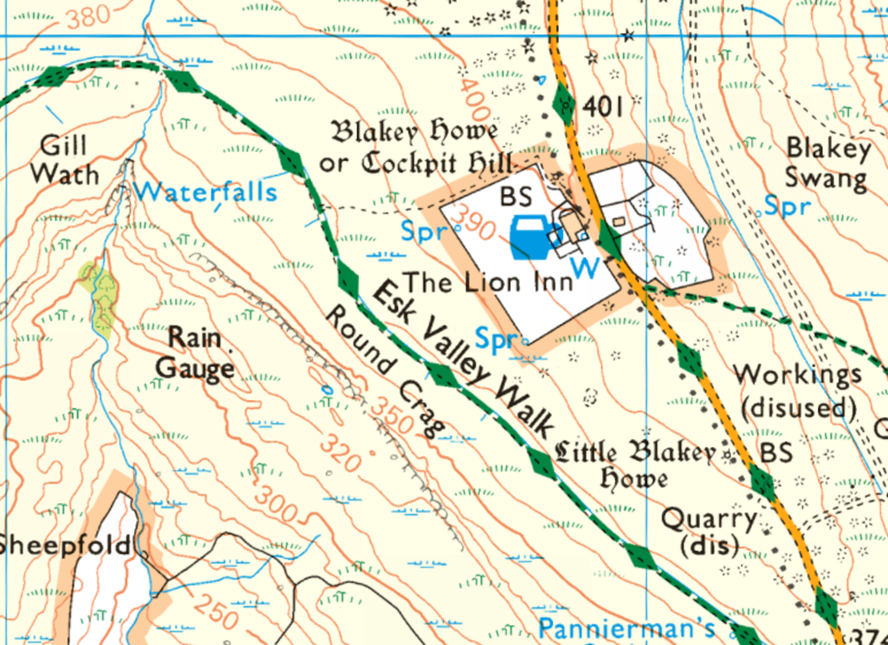

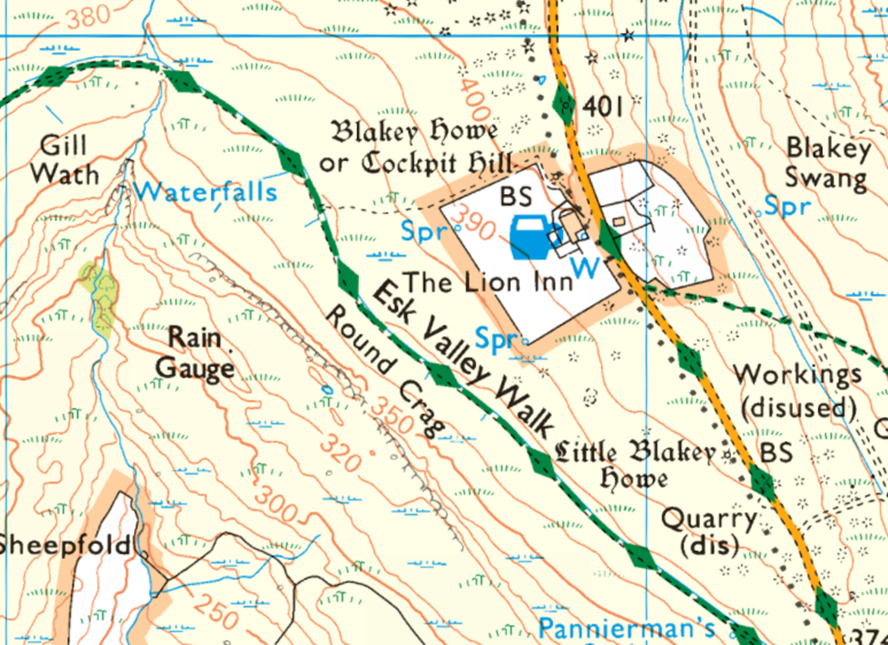

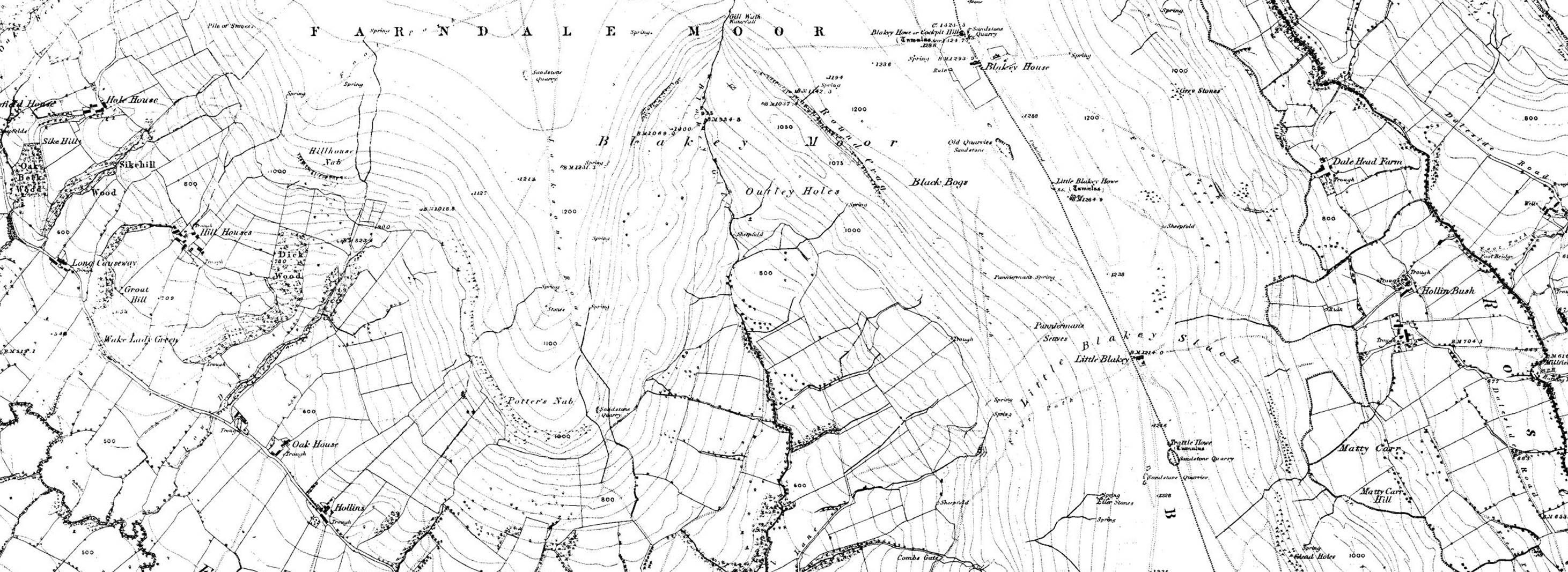

There are

also barrows

on the high ground around Farndale. Blakey Howe is a round barrow which

includes buried and earthwork remains of a prehistoric burial mound, also known

as Cockpit Hill, topped by an eighteenth century boundary stone. It is located

eighty metres from the Lion Inn. It survives in an area which was later

extensively worked for coal, an activity which has left behind several spoil

heaps along the ridge. Referred to as Blakenhow in a Charter of

Gisborough Priory in 1200, the round barrow sits on a natural rise on the spine

of Blakey Ridge and has line of sight to other prominently located barrows in

the area. Constructed of earth with some stone, it is just over twenty metres

in diameter and stands two metres high with an ancient excavation hollow six

metres in diameter and up to one and a half metres deep. This hollow is thought

to have been later used for staging cockfights, explaining the barrow's

alternative name.

On the rim

of this hollow, on the southern side, there is a one and a half metre high

boundary stone which tapers towards its top. On its west face it is inscribed

with the initials TD above four more weathered characters. This is a

reference to Thomas Duncombe who owned the Duncombe Estate west of Helmsley in

the early eighteenth century. It is possible that this stone is a redressed and

reset prehistoric standing stone.

These sites are

all on the high moorland ground which surrounds Farndale. So it seems likely

that early habitation from Neolithic through the Bronze and Iron ages was on

the high ground overlooking an impenetrable wooded valley. There is no reason

to suppose that the valley itself was a place of settlement, even on a small

scale.

Roman

Farndale

One day in

the second or third century CE, a

Roman soldier dropped his arm purse, close to a prehistoric cairn, above

and overlooking Farndale. It was later found in 1849 and is currently to be

seen displayed in the British Museum. When the Roman legionary looked over

Farndale it remained a wild forested place.

As it was found above Farndale, it doesn’t evidence Roman

activity within the dale, but it does suggest patrolling across high moorland

tracks, overlooking the dale.

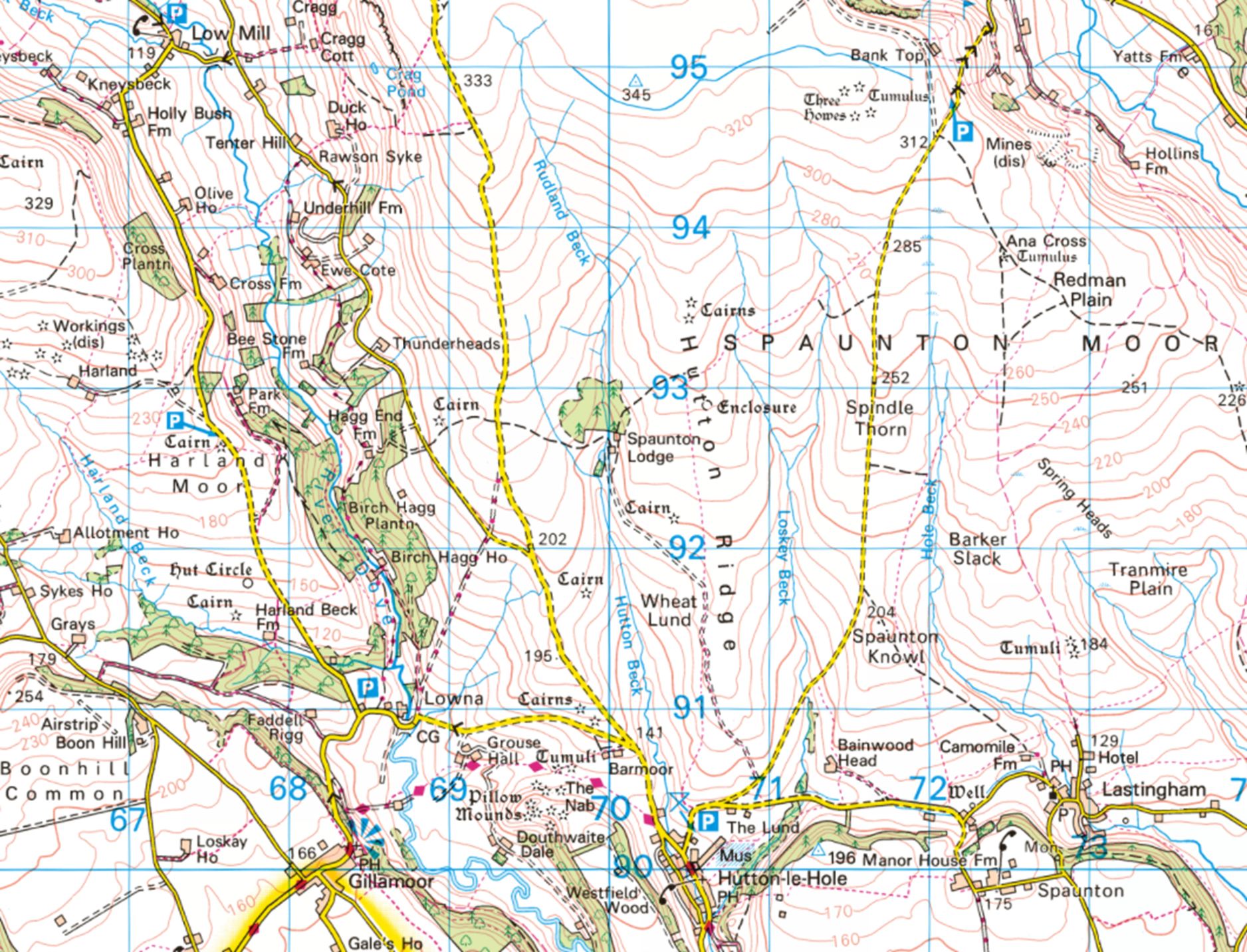

Close to the entrance to Farndale, but to its south,

between Hutton-le-Hole and Spaunton and Lastingham, Roman remains suggest that Romano British

people were living in a clearing between tracts of forest and moorland, on a

site which may have been occupied in Neolithic through to Iron Age periods. The

site was discovered in 1962 when pot sherds were found. There was evidence of a

domestic hearth or oven and animals bones of ox, pig, horse, goat and

red deer. There were some similarities to finds at a villa at Langton. These

were likely to have been smallholder farmers producing for themselves, but

subject to Roman tax levies in corn or hides. A larger farmstead was found nearby,

which included primitive hypocausts. In all there were four isolated farms.

These were probably small families of native Britons in touch with Roman

culture, but whose daily life probably varied little, if at all, from

that of their early Celtic ancestors.

The nearby Roman military fortification at Cawthorn was built for

practice rather than for operational military use and there were certainly

military routes which passed over the moors.

The wild

lands of the Anglo Saxon world

During the

chaos of the post Roman years, the wooded dale slept quietly, a place known

only to the wild forest animals who made it their home.

When Cedd established the early Celtic monastery at Lastingham in 653 CE, only a few miles

south from the entrance to Farndale, he deliberately chose a place at the edge

of civilisation. The Venerable Bede when he

recorded the event a century later described the

area where Farndale lay, vel bestiae commorari vel hommines bestialiter

vivere conserverant, ‘a land fit only for wild beasts, and men who live

like wild beasts.’ These early monks must have gazed across the wild Spaunton

Moor in the direction of the wooded valley that would become Farndale, and felt

they had reached a place at the end of the world.

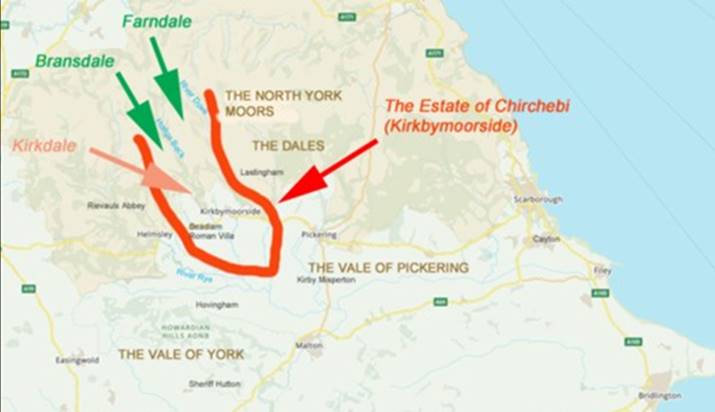

By the

eleventh century, on the eve of the Norman Conquest, the lands which would come

to be known as Farndale were still a remote place, but fell within the great

estate of Chirchebi (later Kirkbymoorside), extending to some twelve by

seven leagues (about forty two miles by seven), part of the multiple lands

across Ryedale and beyond, which belonged to the Anglo-Saxon-Scandinavian

overlord, Orm Gamalson.

Except for

the tiny farmsteads around Lastingham, settlement was focused to the south

within the protection of the edge of the high ground, but extending into the

rich fertile lands of the Vales of Pickering and York. The centres of

civilisation were the small urban settlement at Kirkbymoorside and the ancient

minster dedicated to Pope Gregory the Great, at Kirkdale. These were the lands

where the ancestors of those who would one day extend their area of cultivation

into the dales still lived.

The Norman

Conquest saw regime change and the harrying of the north

brought the northern lands firmly under the Norman yoke.

The nascent

dale remained a deep forest during these tumultuous years, but came to be

included within possessions of land which the elite class would rely upon as

signs of their wealth, and trading stakes for secular enrichment or for

immortality. The dales might occasionally have been used for hunting, or for

collecting wood and other resources in their more accessible peripheral

regions.

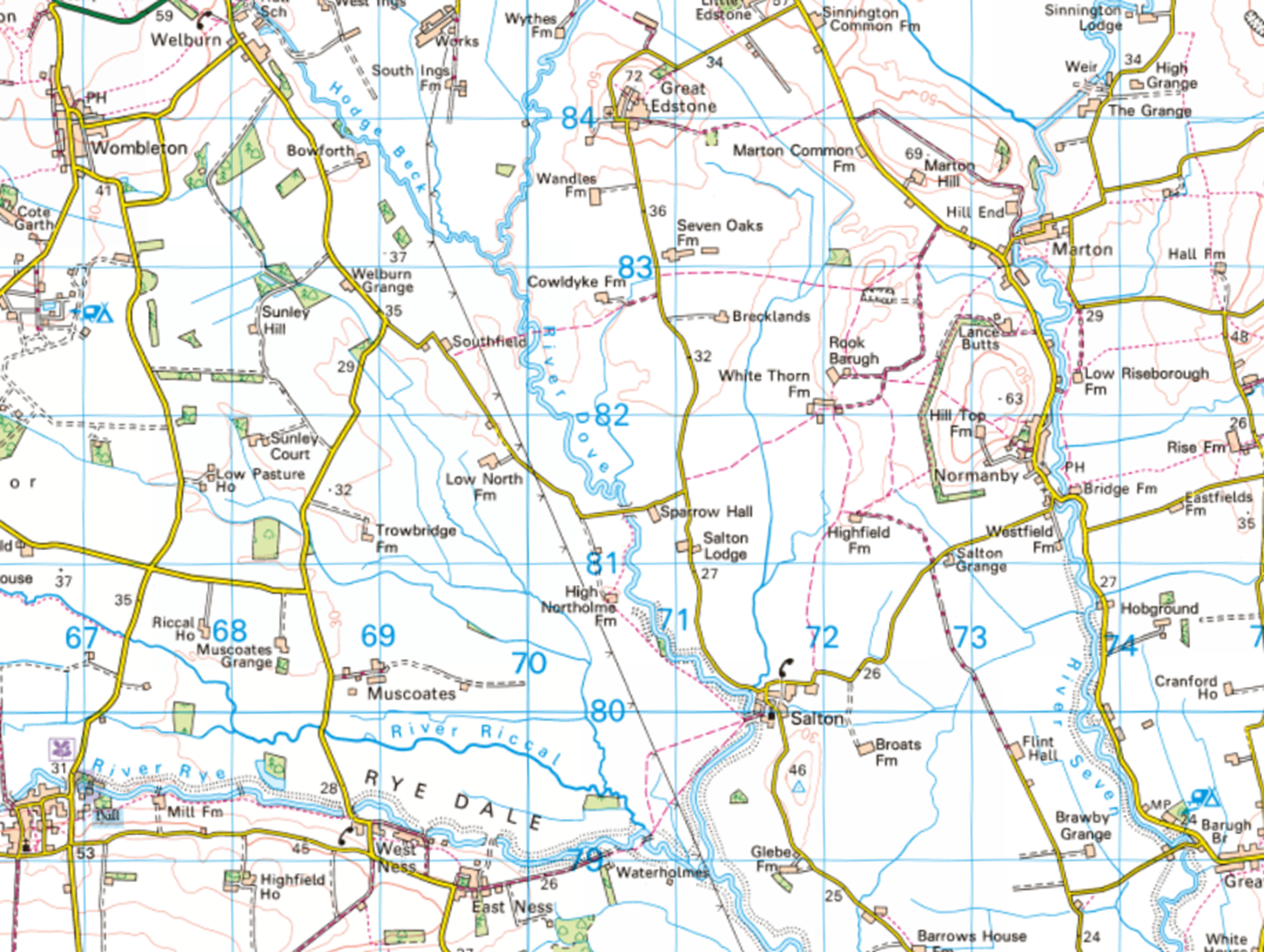

As early as

the reign of Henry I (1068 to 1135), the woodland in the vicinity of the River

Dove was a preserve of hunting. l order that the abbot and monks of York may

hold in peace and with honour all their woodland, and the land from the water

of Dove to the water which is called Seven, as once they held it before the

forest was made. I also grant to the abbot and his successors the whole of my

forestry, and he shall cause to be preserved all my needful things, the hart

and the hind, the wild boar and the hawk, in the same land. Between the

waters of the Dove and the waters of the Seven' is a phrase which often

occurs in charters granted to St Mary’s Abbey at York, but it probably refers

to the lower reaches of the river Dove and not to that part of it which flows

through Farndale.

The lands of

Chirchebi were the arena for a

game of thrones between the House

Mowbray and the House

Stuteville.

Farndale

blinks into the sunlight

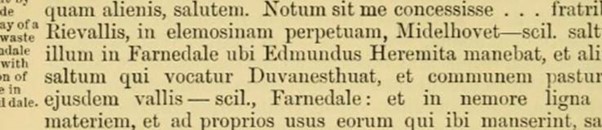

In 1154

Roger de Mowbray, lord of the lands of Kirkbymoorside, gave land in perpetual

alms to the brothers of Rievaulx

Abbey. The lands included Midelhovet where Edmund the Hermit used to

dwell and another meadow known as Duvanesthuat, lands in the valley of

Farndale, together with common pasture rights and permission to take building

timber and wood for those who stay there. Duvanesthuat

is an Irish Norse personal name, but there is nothing to suggest that it

was a functioning settlement by the mid Twelfth century. The whole area was

regarded as a private forest of the Mowbrays. The grant was made saving

Roger’s wild beasts, and it seems to have been anticipated that the monks

would want to build a new dwelling there, probably to use as a grange or cote.

A prior

grant had been made to the Rievaulx brothers, during Roger’s minority, by his

mother Gundreda, which was probably in about 1135. This earlier grant, whilst

not referring to Farndale by name, did include land in Bransdale and in Middelhoved.

There is a suggestion that some of these lands were already cultivated, or

under pasture. This might suggest that there was some early cultivation of

these remote places from the twelfth century, but this was probably on a small

scale, and may not have extended into Farndale.

Both grants

appear in the Chartulary of Rievaulx Abbey, so it is in the records of the Cistercian

monastery, founded only a few years previously, that the name Farndale first

appears in the historical record.

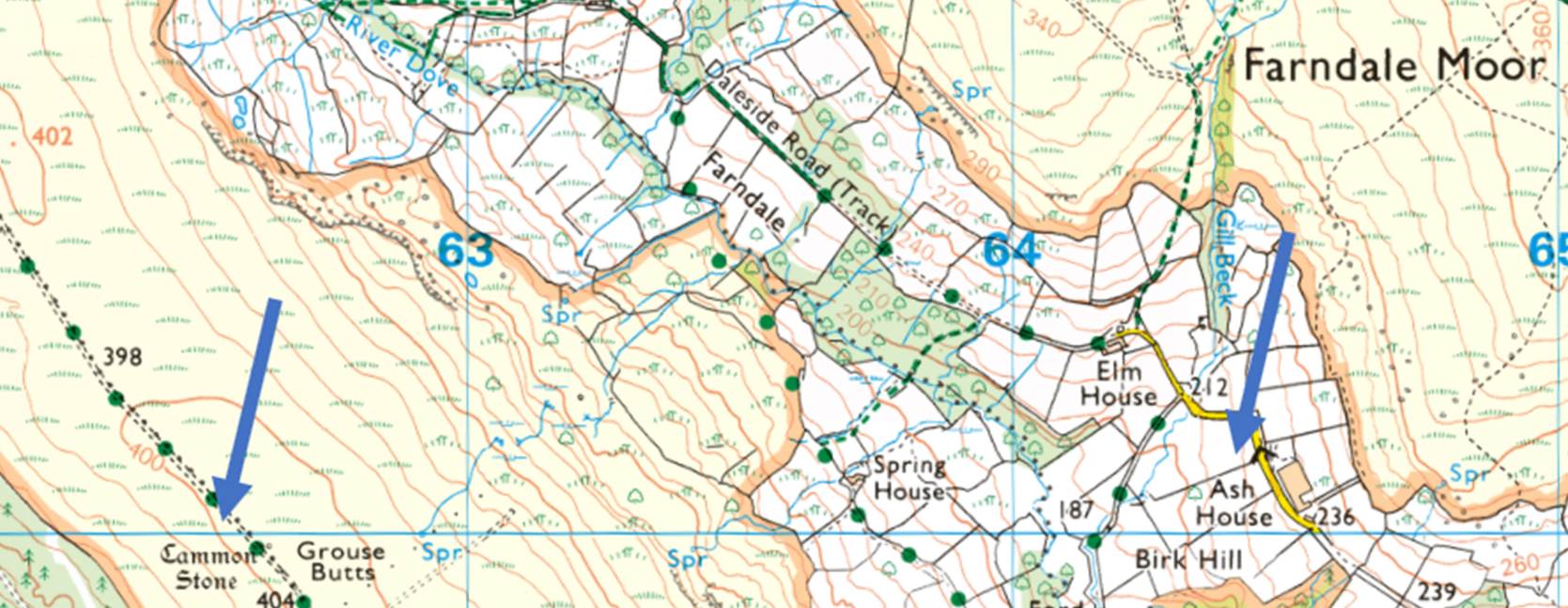

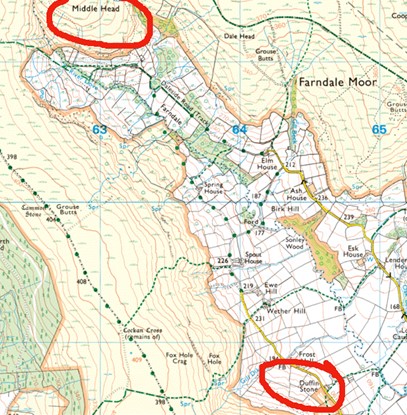

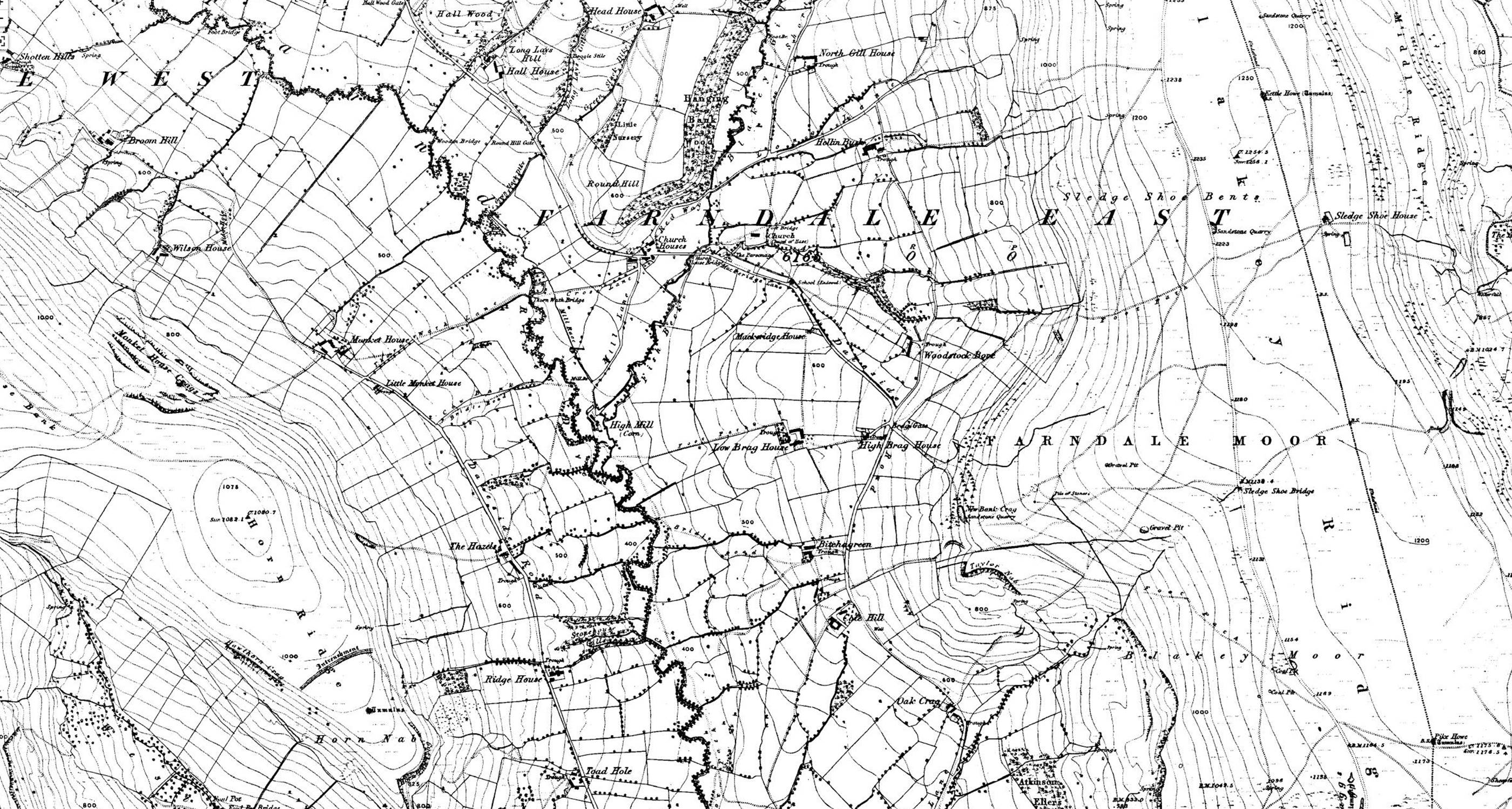

Midelhovet is almost certainly the area in

Farndale known today as Middle Head. Duvanesthuat is probably the place

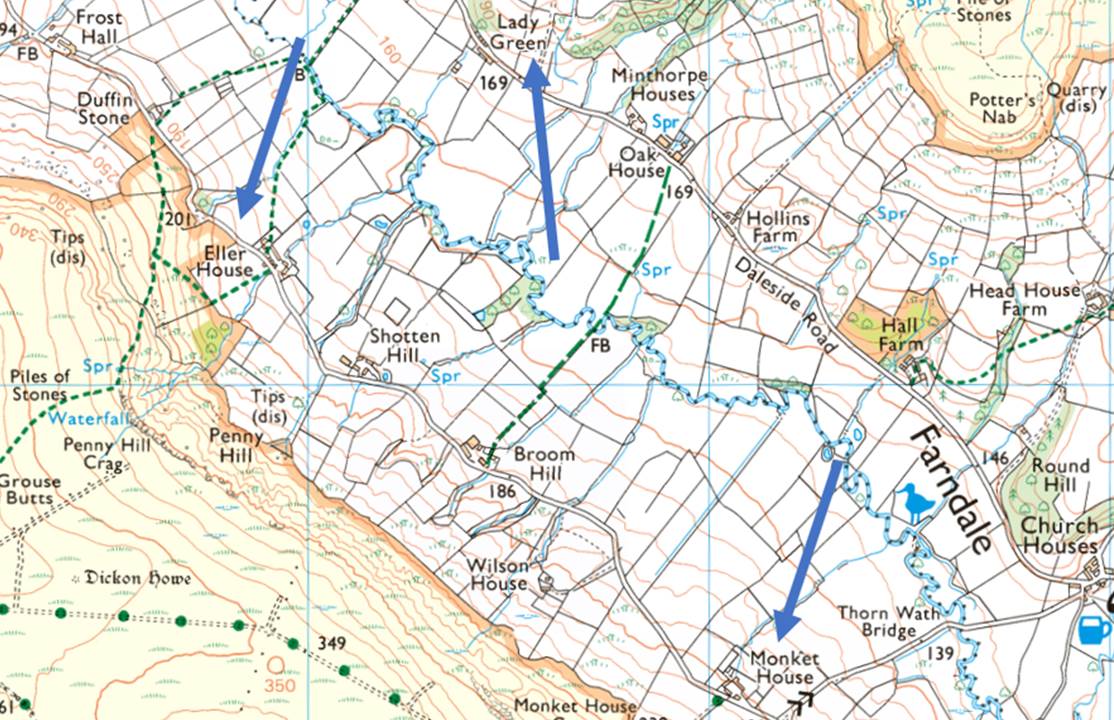

where the Duffin Stone lies today. They both still appear on the Ordnance

Survey map of Farndale.

We’re also

introduced to the first individual who roamed the lands of Farndale, who used

to live at Midelhovet some years prior to 1154. Edmund the hermit of

Farndale was a legendary figure who lived in a cave in the North York Moors in

the twelfth century.

Edmund has

been associated with Hob Hole north of Farndale in Westerdale moor.

Hob Hole

However the

Rievaulx record places him firmly in the craggy area of Middle Head, at the

northern moorland reaches of Farndale, a perfect place for a hermit.

Middle

Head

He was said

to be a holy man who performed miracles and healed the sick. He was also

reputed to have been a descendant of King Alfred the Great and a cousin of King

Stephen. I don’t suppose he was our ancestor, since he was a hermit, but this

is our first introduction to a character roaming the place.

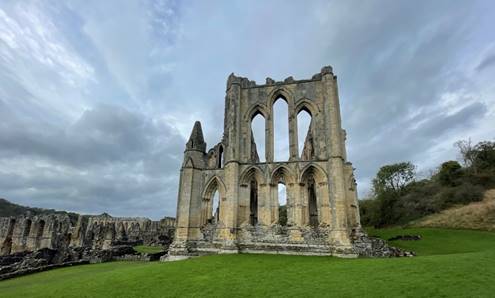

In 1154

those living in the communities of the Kirkdale lands would have wondered in awe at

the Elven halls of the Cistercians of Rievaulx

Abbey, which had risen out of the soil on a vast scale in a nearby valley

on the Rye in only twenty years since the Cistercian monks had first arrived

there. This was a Lord of the Rings world of strange lands of a

Middle Earth, which included such places as Midelhovet and Duvanesthuat,

dimly known to the folk of the shires around Kirkdale, where strange monks had so recently

arrived, bringing French Cistercian traditions and constructing wondrous

towering halls.

Tolkein’s

Rivendell

Rievaulx

The

taming of the lands of monsters and wild beasts

The Stutevilles, who came into

possession of the Kirkbymoorside estate, favoured the Benedictine monks of

Saint Mary's Abbey, York, and their own small House of nuns founded by them at Keldholme, just

to the east of Kirkbymoorside. Rievaulx Abbey therefore went out of favour in

its claim to Farndale. In about 1166 Robert de Stuteville granted to Keldholme

Priory the timber and wood in Farndale.

In 1209 the Abbot

of the Benedictine Abbey of St Mary’s in York

obtained rights

in the forest of Farndale from King John. By 1225 there was reference to pastures

in Farndale.

The

accumulation of lands and rights by the monasteries was rapid. At Rievaulx, for

example, the greater parts of the lands were acquired and a very large number

of granges established by the end of the twelfth century. Even by 1170 the

monks had acquired all Bilsdale, Pickering Marshes, the parts of Farndale and

Bransdale, the vills of Griff, Tileson, Stainton, Welburn, Hoveton, and

the lands of Hummanby, Crosby, Morton, Wedbury, Allerston, Heslerton, Folkton,

Willerby, Reighton. Some

donors had apparently not bargained on such a rapid increase in monastic

possessions. It came as a shock to find that the monks were not all that was

simple and submissive; no greed, no self-interest. The result was that men

like Roger de Mowbray, Robert de Stuteville, Everard de Ros and other men of

the nobility, formerly significant donors and founders, began to attempt to

evict the monks from some of these lands, though monastic expansion continued.

The

monastery at Rievaulx accepted gifts of land to farm sheep for wool and grow

food, or from which to extract minerals, quarry stone and retrieve timber for

building and repairs. Initially they would accept only undeveloped land because

managing tenanted land would entail an engagement with the secular world which

strict Cistercian monastic doctrine was designed to avoid. This changed over

time. Gundreda’s grant at Skiplam, which lies south of Farndale and a short

distance north from Kirkdale,

for instance, had never been settled for or tilled. Elsewhere though, there is

evidence that the monks began to work some areas which had already, perhaps

recently, been cultivated since grants included de culta terra, “of cultivated land”, as well as a grant ubi culta terra deficit versus aquilonem, “where the

cultivated land declines towards the north”. So the Cistercians, whilst solitaries, seem to have

benefitted to some extent from previous lay efforts. It was often the success

or failure of lay farmers in a particular area which helped the monks to see

the potential it offered them. They received saltum or rough

pasture at Farndale Head on the higher ground and common pasture in Farndale

and Bransdale. The

subsequent work of the monks in all these places must have resulted in the

extension of any previously cultivated land. The Cistercians became active farmers. During the twelfth

century one of the gifts to Rievaulx was a pasture with sixty mares and their

foals. As well as sheep, they were engaged in rearing pigs. Aelred’s

letters suggest that the monks grew flax

which they made into linen at Rievaulx. There may have been a tannery

during Aelred’s abbacy

The

Cistercian abbey of Rievaulx established granges or farms which they owned and

managed themselves, where they grew food and raised sheep, cattle and horses,

as well as producing various raw materials. Beyond supplying the monastic

community at the mother house with its needs, the granges were also expected to

produce a surplus which could then be marketed to yield an income. The monks

and lay brothers tended to site their granges away from villages. Monastic

farms became an independent economic force. The sheep grange was dominant in

Yorkshire with many examples, including at Farndale, of donations of rights to

pasture a fixed number of sheep.

These were

the days of the early evolution of a wool industry that in time would provide

Britain with its primary economic power source. Our family story has taken us

to the powerhouse that would guide the national progression.

So we can

imagine that small clearings emerged in the late twelfth and early thirteenth

century in the dales which included Farndale, and perhaps pathways were cleared

through the woods for access. It seems likely that this early clearance would

have been at the periphery. There might have been some limited pastural grazing

and there was certainly removal of timber, though this must have been on a

relatively small scale.

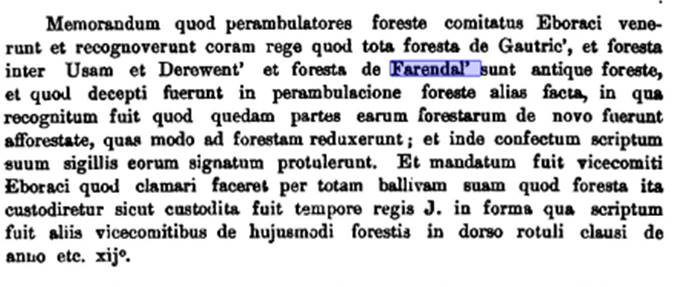

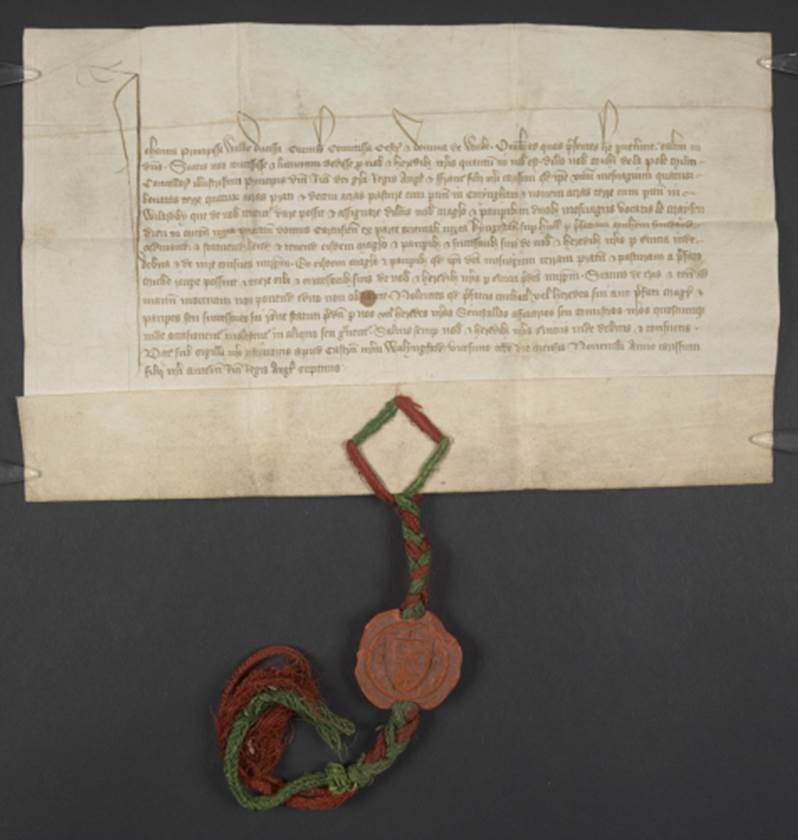

In 1229

Henry III decreed that the forest of Galtres, the forest between the Ouse

and the Derwent, and the forest of Farndale, were ancient forests and the

forest should be guarded, there being no right of passage. The forest of

Farndale had become part of the royal forests, reserved for the King.

The Close

Rolls in the thirteenth regnal year of 13 Henry III, in 1229 declared that it

should be remembered that the walkers of the forest of the county of York came

runt and recognized before the King that the whole forest of Gautric and the

forest between Usam and Derewent and the forest of Farendal are ancient forest,

and that they had been deceived in the perambulation of the forest other times

in which it was recognized that certain parts of those forests had been

reforested , which they just brought back to the forest; and thence they

brought forth the finished writing, which was sealed with their seals.

However in

1233, the Abbot of St Mary’s came to an agreement with the Stuteville family granting

free passage through the wood and pasture of Farndale. The

Abbot granted that if the cattle of Nicholas or of his heirs or

of his men at Kikby, Fademor, Gillingmor or Farndale, hereafter enter upon the

common of the said wood and pasture of Houton, Spaunton and Farendale, they

shall have free way in and out without ward set; provided they do not tarry in

the said pasture.

The feudal

lord of the Kirkbymoorside estate, William de Stuteville was succeeded by his

brother Nicholas I de Stuteville, the Lord of Liddell. Nicholas was one of the

barons who met at Stamford in 1216 and fought against King John at the

Second Battle of Lincoln on 20 May 1217 and he was taken prisoner there by

William Marshall. The manors of Kirkbymoorside and Liddell were required to pay

1,000 marks as his ransom. His son Nicholas II de Stuteville in 1232

quitclaimed, or relinquished, common of pasture in Farndale to the Abbot of St.

Mary's, York.

His son,

Nicholas II de Stuteville, gave to St Mary’s Abbey, who held the nearby manor

of Spaunton, as much timber and wood as they required together with pasture and

pannage of pigs in Farndale. The contemporaneous documents suggest that

Farndale was regarded primarily as a resource for timber and pasture in the mid

twelfth century, with little evidence of settlement. References to the Botine

Wood and the Swinesheved suggests that cattle and pigs were being

grazed there. The Abbot grants that if the cattle of Nicholas or of his

heirs or of his men at Kikby, Fademor, Gillingmor or Farndale, hereafter enter

upon the common of the said wood and pasture of Houton, Spaunton and Farendale,

they shall have free way in and out without ward set; provided they do not

tarry in the said pasture.

Since 1154

the Cistercians had interests in Farndale and may have used it first to supply

wood to their monastic empires and might also have used meadows as pasture for

the sheep which would give them their wealth.

Settlement

By about

1230, perhaps a little earlier, the

House Stuteville, were putting villeins into their land holdings in Farndale,

to clear the land, and then for all time coming, or so they hoped, to allow

them to eek out a desperate living from the land, whilst more importantly

paying rent, agreeing to loyalty, and providing service when required, to the

Stutevilles for the right to do so. Thereby, in a clever rouse, the Stutevilles

turned the areas of their landholdings that had provided them with little

benefit into a profitable enterprise.

We might

suppose that the clearing of Farndale was undertaken by the villeins who were

then put onto the land to work it, compelled to pay rents of 1s per acre for

tiny holdings of marginal land. The evidence of rents being applied in Farndale

by 1276 suggest a campaign on a large scale. The villeins who were relocated

into Farndale were likely to have been Anglo-Saxon-Scandinavian

agriculturalists of the lands around Kirkdale reduced to

serfdom by the Norman yolk.

In 1233,

Nicholas II de Stuteville

died, and the estate passed to his daughter Joan, the wife of Hugh Wake, who

became the Lady of Liddell and to his other daughter Margaret, wife of William

de Mastac.

By 1241,

Joan’s first husband was dead and she married Hugh le Bigod. When her sister

Margaret died in 1255, Joan inherited Margaret’s lands too.

Regarding

the royal forests, in

1253, The King committed to Hugh le Bigod the whole forest of

Farnedala, which the king had lately recovered by consideration of the

court against the abbot of St. Marie Ebor, to be kept until the return of the

King from Vasconi, or as long as it pleased the king. This was confirmed in

1255, for a payment of 500 marks. The Close Rolls of 1255 confirmed For Hugh

le Bygod. It was ordered to John de Lexinton, justiciar of the King's forest

beyond Trent, that the charter which the king caused to be made to Hugh le Bygod

concerning the forestry of the forest of Farendale he shall make a law

before him, and that grant shall be held according to what is contained in the

same charter: and he shall admit the foresters, greenkeepers and other

ministers of the forest for whom the same Hugh is willing to answer for his

presentation in the aforesaid forest.

The Calendar

of the Liberate Rolls for 1255 also ordered Allocate to Hugh le Bygot, in

his fine of 500 marks for the forestership of Farndale, paid at

Westminster to Ernald de Mone Pesaz. The associated index entries: Farndale,

Farendale, foresterhip of, Forests, chaces, hays, parks, warrens and woods

named … Farndale … forestership of Farndale.

The Close

Rolls at this time suggests a dearth of deer in the area to the south of

Farndale. The Keeper of the Royal Forests reported the forest of Spaunton

between the Dove and the Seven is so confined that deer do not oft repair

thither. The Stutevilles’ attention was starting to turn from hunting to

cultivation.

So Joan, the

Lady of Liddell, through husbands Hugh Wake and Hugh le Bigod, held the primary

interest in the lands which included Farndale by 1233. The King withheld the

forests, including the Farndale forests, from 1229 as royal hunting grounds,

but this did not appear to stop the Stutevilles starting to clear areas of land

for agriculture, whilst the deeper forested areas had become royal hunting

grounds. By 1253 the Farndale forests passed back into Stuteville hands for

payment of a significant sum of money.

In the mid

thirteenth century, Lady Joan de Stuteville successfully prosecuted the Abbot

of St Mary’s York, for exceeding his rights taking wood from Farndale by

assarting 100 acres of land, perhaps clearing the offending area of its trees.

Joan de Stuteville was also said to be afforesting her woods here in the reign

of Edward I (1239 to 1307). So this suggests a pattern of clearance and

reforesting across the dale. It must have been a busy place.

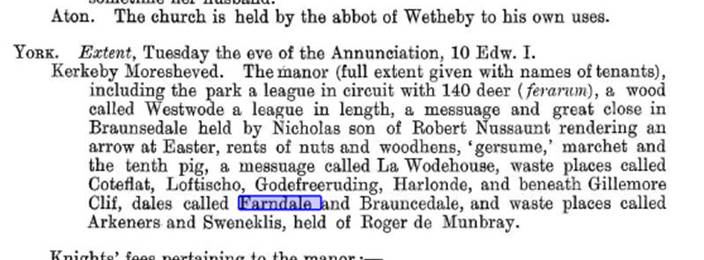

An

Inquisition in 1249 recorded holdings at Farndale. Tuesday the eve of the

Annunciation, 10 Edward I: Kerkeby Moresheved. The manor (full extent given

with names of tenants), including the park a league in circuit with 140 deer

(ferarum), a wood called Westwode a league in length, a messuage and great close

in Braunsedale held by Nicholas son of Robert Nussaunt rendering an arrow at

Easter, rents of nuts and woodhens, 'gersume,' marchet and the tenth pig, a

messuage called La Wodehouse, waste places called Coteflat, Loftischo,

Godefreeruding, Harlonde, and beneath Gillemore Clif, dales called Farndale

and Brauncedale, and waste places called Arkeners and Sweneklis, held of Roger

de Munbray. Knights' fees pertaining to the manor.

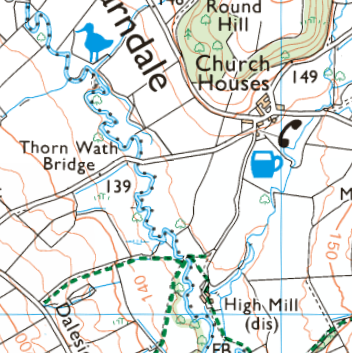

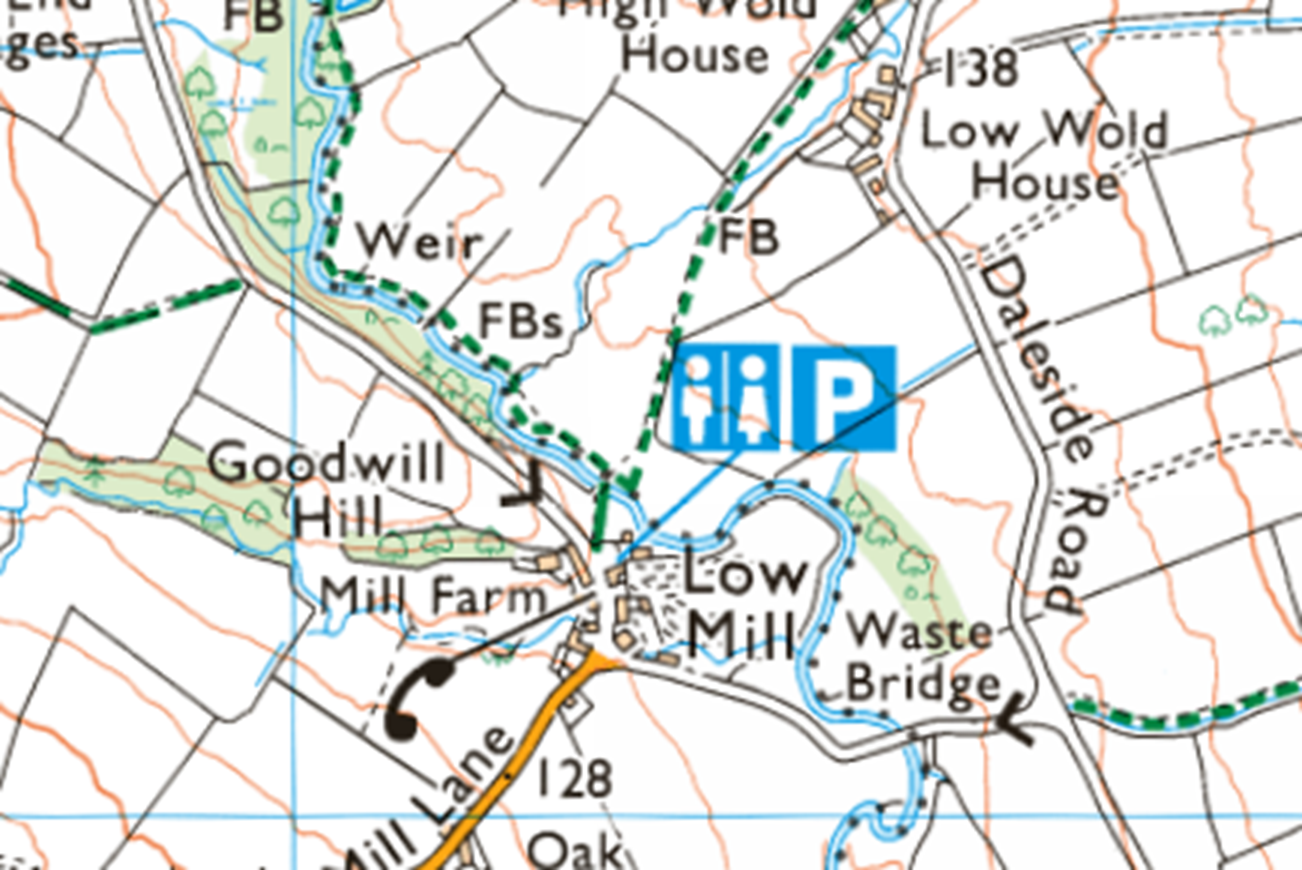

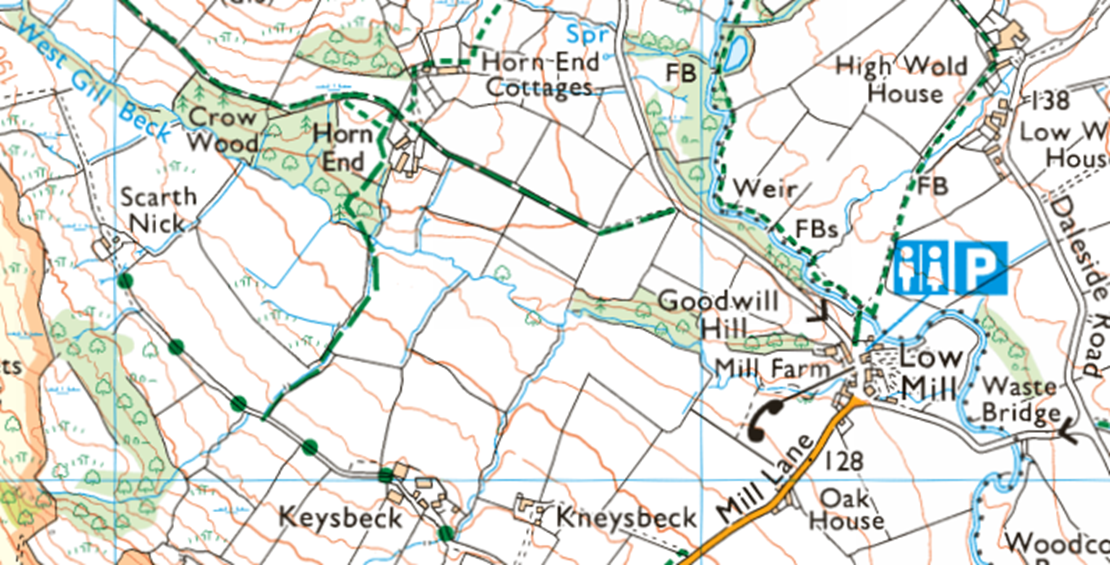

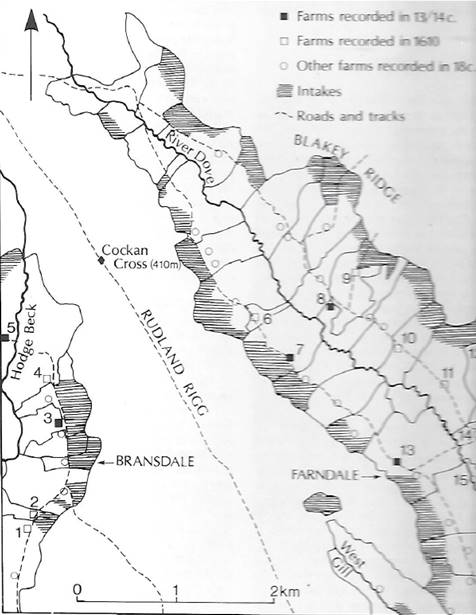

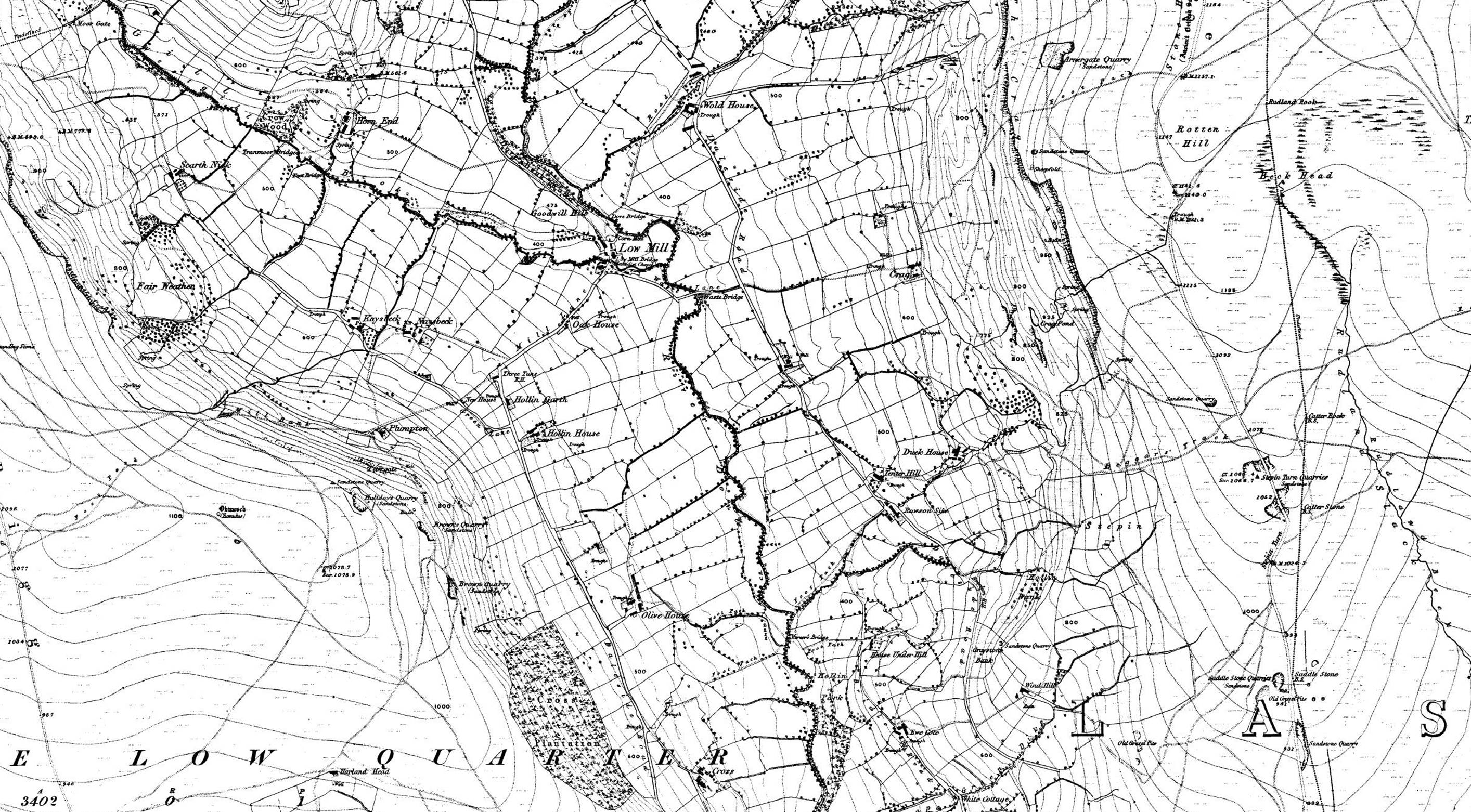

The location of the now disused High

Mill, now known better for the Daffy Café.

By the mid thirteenth century

Farndale was a thriving community of two watermills and we can meet Simon the Miller of Farndale, who was clearly a substantial figure. We can also meet Nicholas de Farndale, who might be the first to have adopted the name Farndale, and who must

have been one of the earliest pioneers of the dale.

The River Dove would have provided an

optimal source of power for milling. There was a nineteenth century watermill at High Mill on Mill Lane south of Church Houses, Farndale, which is almost certainly the site

of an earlier mill. The hamlet of Low Mill was also the site of an earlier mill

on the River Dove and is located where the fast flowing West Gill Beck flows

down from the high ground to meet the River Dove. Both these mills were located

centrally within the valley. There are also remains of a watermill at Low Elm House in neighbouring Bransdale.

Our

understanding of the thirteenth century dale is greatly improved by medieval

records which provide us with three remarkable snapshots of life in Farndale in

1276, 1282 and 1301.

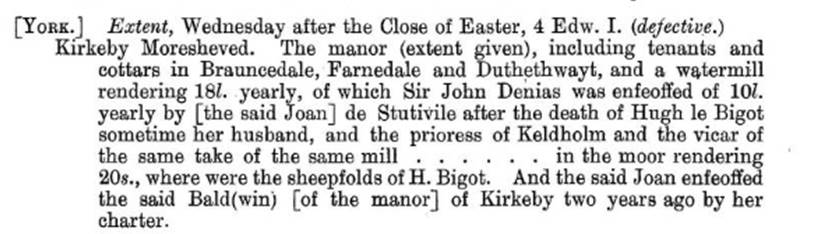

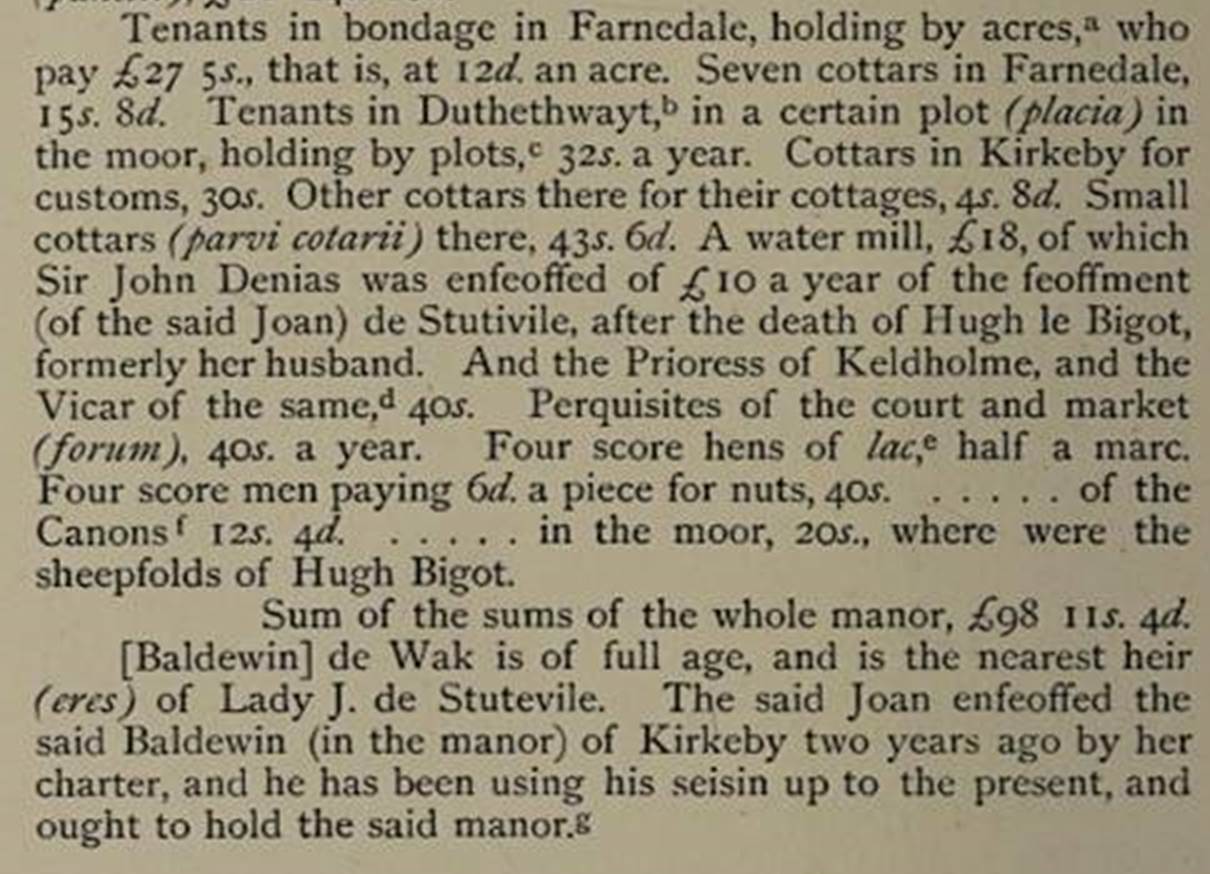

The Inquisition

Post Mortem taken in 1276 after the death of Joan de Stuteville, the Lady

of Liddell, reveals cultivation on a grand scale. In Farndale, bonded tenants

were paying a standard rent of 1s for each acre. This produced total income of

£27 5s, suggesting a cultivated acreage in Farndale of 545 acres (for those who

like the maths, 27 x 20s in the pound plus 5s). There were seven cottars or

small scale farmers recorded, and one of the two watermills we know to have

existed by 1249. The tenants of Duthethwayt,

which presumably is Duvanesthuat of the 1154 Rievaulx grant, further

up the dale, was recorded separately.

The Inquisition

Post Mortem of Joan’s Son, Baldwin Wake, taken only six years later in

1282, shows a considerable increase over that of 1276. The Farndale rents then

amounted £38 8s 8d together with a nut rent and a few boon

works so if the rate of 1s per acre still applied, this would give a total

acreage held in bondage of 768 acres. For the first time the number of villeins

were given. There were twenty five in neighbouring East Bransdale and ninety in

Farndale. Amongst these folk must have been our ancestors.

Baldwin’s son, John Wake enfeoffed the King of his lands in 1298. In other words he bent the knee. The lands were regranted to him and his wife Joan in fee simple in the same year.

Now this is

where it gets a little complicated because there are a lot of Joans. We have

already met Joan de Stuteville, the Lady of Liddell who was the daughter of

Nicholas and the sister of Margaret. She married Hugh Wake. It was at this

point that the Stuteville inheritance became that of the Wake family. Joan

later married Hugh le Bigod.

We have also

already met Baldwin Wake, Joan’s son, who took homage from the King in 1276.

Baldwin’s son was Sir John Wake, the first Baron Wake of Liddell who inherited

the estate in 1282 but for some reason did not take homage from the King until

1298 (or perhaps this was a refreshed bending of the knee to Edward I

Longshanks, who reigned 1272 to 1307). Sir John Wake married another Joan, Joan

de Fiennes. Sir John died in 1300 and his son, Thomas Wake, inherited before he

had come of age.

Joan de

Fiennes outlived her husband, Sir John, when he died in 1300, and became

another Lady of Liddell during the minority of her son Thomas Wake. The custody of the boy was granted to

Henry de Percy, who transferred it to the Society of the Ballardi of Lucca. The

Society of Bellardi Merchants of Lucca, with interests in London and Paris,

were money lenders to the Kings of England and France.

The young

Thomas’ minority interests were ratified by the King, but later, not

recollecting his confirmation of the grant, he caused the manor, then in

the hands of the merchants, to be taken into his hands, and he delivered it

with its fees &c. to the said Thomas, a minor and in his custody, who since

he has held the said manor has received £340 out of the issues thereof, for

which Henry de Percy has made supplication to the king to cause satisfaction to

be made to the merchants for his exoneration. The King promised to make

payment of the sums taken on the estate to Thomas.

Sir John also had a daughter, Margaret Wake, who married Edmund, the sixth son of Edward I, with whom she had four children, including another Joan, who we will meet again soon.

The Stuteville history will

continue to provide an exotic subplot to lives of the ordinary folk of

Farndale.

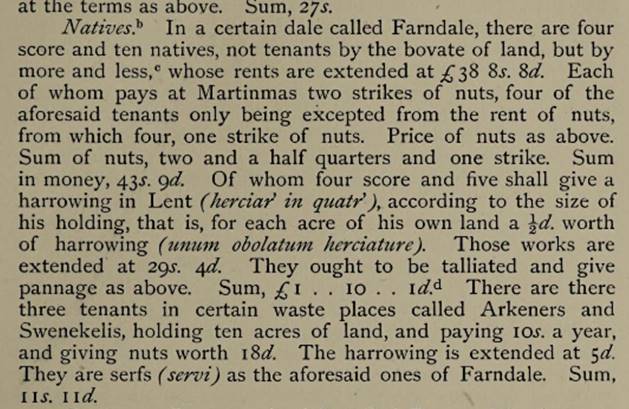

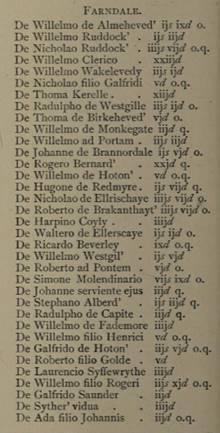

In 1301

Edward I levied a tax of one fifteenth of the value of every person's goods, to

pay for his war against the Scots. Collectors were appointed for various parts

of the country, and the

returns for the North Riding of Yorkshire still exist in their entirety in

the Public Record Office. The lay

subsidy assessments of 1301, imposed by Edward I to

fund his wars with Scotland, give us another detailed picture of the

settlement pattern in Farndale, listing the contributors and bearing the names

of the farms which are still to be found at Farndale today and which are

scattered all around the dale.

The list of

thirty five tax payers showed that they paid varying amounts from 3d to 7s 9d

paid by Simon the

Miller of Farndale. By comparison at that time a cart horse and a cow each

would cost 5s; a sheep 12d; a bullock 2s; a bed 4s; a pound of wool 3s and a

poor robe about 4s. In Farndale, thirty-four men and one woman, a widow,

contributed a total of £3 7s 33d. This compared to £2 3s 83d paid by twenty

seven inhabitants of Kirkbymoorside (in addition to which the lord of the

manor, John Wake, himself paid over two pounds), and £3 8s 43d paid by thirty

six villagers of Helmsley. Farndale was clearly a thriving community.

Since the

tax was a fifteenth of the value of each person’s wealth, the wealth of these

individuals can be calculated by multiplying the tax by fifteen. Simon the

Miller had a wealth of about £5 16s 3d, perhaps about £4,500 in today’s money,

the value of about six horses or 12 cows. Simon the Miller’s tax payment of 7s

9d in 1301 was almost as much as that paid by all ten of the Bransdale

contributors and greatly in excess of what the majority of the individual

inhabitants of Ryedale paid.

That Edward

intended to tax even the very poor is shown by the fact that some of the

amounts paid by individuals in other parts of Ryedale were as low as one and a

half pennies, meaning that their entire goods were valued at less than half a

crown. The record of the subsidy imposed on Farndale is therefore likely to

have been a record of the whole working population of the dale. The record also

evidences the range of wealth in the dale at the turn of the fourteenth

century.

We are also

provided with a glimpse of the settlement pattern, listing several contributors

bearing the names of the farms which is still to be found at Farndale. For

instance Wakelevedy is known as Wake Lady Green

today.

Monkegate today provides modern accommodation

at Monket House.

Ellerscaye and Ellrischaye is called Eller House today.

Westgille and Westgil’ is the West Gill

Beck which flows rapidly down from the high lands to Low Mill, where it joins

the river Dove.

Other

individuals such as John de Brannordale, Godfrey de Hoton and William de

Fademore, were clearly inhabitants of the dale who had come originally from

outside Farndale, and took the names of their places of origin.

So during

the thirteenth century, we have a picture of serfs, who together formed a body

of folk who must have included our ancestors, toiling the soil at first in a

dreadful battle of survival, but who by the end of that century seem to have

acquired a degree of wealth, sufficient to be tapped for relatively significant

royal taxes.

Those

individuals who came to be the first inhabitants of Farndale had been plucked

from the primeval sludge of

Bronze Age Beaker Folk, Iron Age Settlers, Brigantes and Deirans who had

roamed the moors, dales and vales of Yorkshire since about 9,000 years BCE,

most likely settling by Roman times in the cultivated lands around Kirkdale, a place of

even greater antiquity, which has left us the remains of interglacial age hippopotami.

There are a

large number of individuals from Farndale at this time who can be individually

identified. I have assembled those who were most likely to have been ancestors

of the modern Farndale family into a probable genealogical tree. We are

introduced to the hard working agriculturalists who first cleared the land and

started working the virgin soil in the thirteenth century. The second

generation included a large number of their wayward offspring who regularly

participated in poaching

expeditions, though to be fair to them, they might have been driven to

supplement their diets in desperate times of poor harvests and plague. By the

end of the thirteenth century the pioneers

then left Farndale to start lives in new lands, establishing our family as they

did so.

The Eyre

Court of 1334, in the eighth regnal year of Edward III, on the pleas of the

forest of Henry, earl of Lancaster, of Pikeryng, held at Pickering before

Richard de Wylughby [Willoughby], Robert de Hungerford and John de Hambury,

justices itinerant on this occasion assigned to take pleas of the said forest

in Yorkshire, recorded that in 1310 to 1311 (the fourth regnal year of

Edward II), one oxen and two stirks [a stirk is a yearly bullock or

heifer], which were of Robert the smith of Farndale, worth 7s 4d; and

5 oxen, which were of Walter, son of the same Robert, of the same, worth

20s; and 3 oxen, which were of John son of Simon of the same, worth 12s;

and one cow and one stirk, worth 4s 8d, which were of Hugh Leverok of the

same; and 4 oxen and 3 stirks, which were of Simon Cundy of Kirkeby Morset

[Kirkbymoorside], worth 21s; and 6 oxen, which were of William Stibbyng of

Farnedale, worth 24s; and 5 oxen, 4 cows and 4 stirks, which were of William

de Waldehus of the same, worth 38s 8d; and 4 oxen and one stirk, which were

of John, son of Walter of the same, worth 17s 8d; and one cow which was

of Alice daughter of Roger, worth 3s; and 6 oxen, 2 bullocks and 2

beasts of burden, which were of Henry, son of Hugh of the same, worth

38s; and 6 oxen and one cow, which were of Nicholas, son of Adam of the same,

worth 27s; and 6 oxen, which were of Hugh del Radmire of the same, worth

24s; and 5 oxen, which were of William ad Portam [literally means

‘of the gate’] of the same, worth 20s; and 9 oxen, one cow and

one stirk, which were of John the shepherd of the same, worth 41s 8d;

and one bullock, which was of Roger, his groom, worth 4s; and one ox and

one bullock, which were of Nicholas de Harland of the same, worth 7s;

and 4 oxen and two cows, which were of Alan de Wrelton of the same,

worth 19s; and 2 bullocks and one ox, which were of Stephen son of William,

worth 12s … were found in the said forest [of Pickering] there

by the watch, and they were forfeited to the lord at the said price.

Therefore each of them is to answer for the price of his beasts. Sum total

forfeited, £30.

The list is

of a large number of Farndale folk by 1334 and suggests they were heavily

penalised for allowing their animals to stray into the royal forest. Although

the reference is to Pickering Forest, it must have referred to the parts of

Farndale which were subsumed into the great royal forest of Pickering. It

suggests a tension between the new farming folk of Farndale, who had by then

been cultivating its land for a century, with the forest laws of the ancient

royal forests.

In 1315, one

of Britain's worst storms halved the crop yield and half a million died as a

result. Thus, the price of crops increased driving many to hunt illegally. Folk

took to hunting but where they did so in royal forests, such as Pickering, it was a significant risk. Such

men must have been skilled bowmen, potentially also those who might be called

upon to fight for their king. However, when they hunted in the royal forests

they were criminals. The hunters were chased by the king's foresters and were

often caught and hauled up at Pickering Castle to answer for their crimes. Such

exploits later sparked the legend of Robin

Hood, a Yorkshire legend before its association with Nottingham. It was

also these skilled bowmen who in time would form the backbone of the successful armies at Crecy and

Agincourt. The story of the many folk of Farndale whose lives were recorded

because they were summoned for poaching offences is told on another website page.

A petition

of 1325 related to Thomas Wake’s costs for his service with the King with foot

soldiers at Berwick and Edinburgh. It also asked the King to order that the

Earls of Leicester and Richmond and Arundel be ordered to accept one homage for

Kirkby in the fee of Mowbray to pay off their demand for homage. Thomas Wake

was John Wake’s son, and Lord of the Stuteville-Wake estates between 1300 and

1349, but, it will be recalled, in his minority until about 1318. The

Stutevilles continued to hold the primary interest in the estates as tenant in

chief, but strictly the feudal overlordship was still held by the Mowbrays.

The 1325

petition also asked that the justice of the forest should be commanded to

deliver his wood of Farndale. It seems that the Wakes were in a dispute with

the forest administration regarding rights in Farndale. The King seems to have

replied that he should deliver a writ to the justice of the forest to certify

the reason for taking the wood. The King (Edward II, 1307 to 1327) was asking

for the case for the defence, before making his judgement.

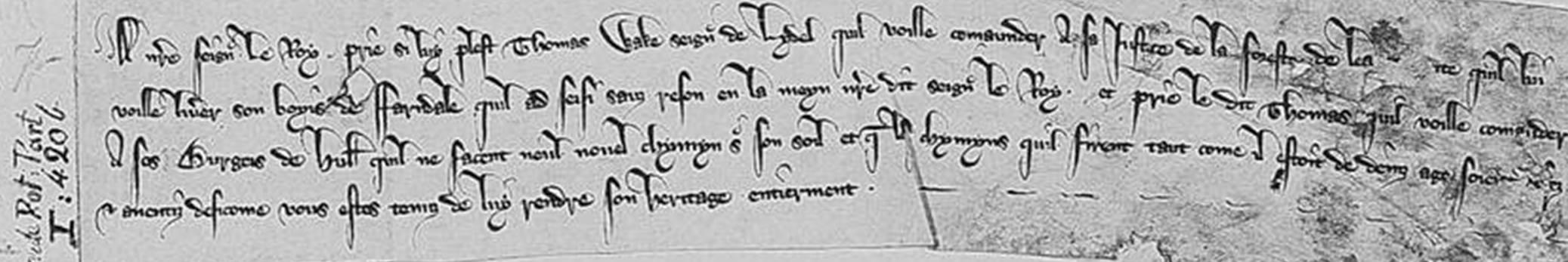

In a

subsequent document, Thomas Wake then asked that the justice of the forest

should be commanded to deliver his wood of Farndale and added that he seized it

without reason. Thomas also asked in the document that the burgesses of Hull

should be ordered not to build any new road on his land and to destroy the

roads they had made during the period when Thomas had been underage, as Thomas

argued that he was entitled to his inheritance in full.

A few years

after he had taken full control of his estates, he seems to have been asserting

control over interests that were perhaps exploited during his minority.

Thomas

Wake requests that the king command his Justice of the Forest north of the

Trent to deliver to him his wood of Farndale, which he has seized into the

king's hand for no reason. He also asks him to order the burgesses of Hull not

to build any new road on his land, and to destroy the roads they made when he

was under age, as the king is obliged to render him his inheritance in full.

Coram rege. With regard to the wood, the Justice of the Forest is to be ordered

to do justice to him, according to the law and usage of the forest. With regard

to the roads, he is to have recourse to common law. Date given on the evidence

of Rot. Parl. JRS

Phillips.

It seems

that the justice of the forest was then ordered to do justice to Thomas Wake,

according to the usage and law of the forest. However with regard to the roads,

Thomas should resort to the common law. The King seems to have fudged his

decision, as judges so often do.

Friars,

Plague and a Fair

The different

orders of

friars were well represented in the area by the fourteenth century. In York itself there were houses of Dominicans,

Franciscans, Carmelites, Austins, and of the short-lived Order of the Sack. In

1257 Walter de Kirkham, Bishop of Durham, granted four acres of land at

Osmotherley for the establishment of a priory of Crutched Friars, and on 30

July 1345 Thomas Lord Wake of Liddell had royal licence to grant a toft and 10

acres in Blakehowe Moor in Farndale for the foundation of a house of the

same order. It is generally assumed that these Friars never established

themselves in Farndale, but therein lies a mystery.

The Patent

Rolls recorded that at Reading. Licence for the alienation in Frank Almoin

by Thomas Wake of Lyde to the friers of the Holy Order of the Holy Cross of a

toft and 10 acres of land in the moor of Blakenhowe in Farndale, for them to

found a house of the Order there and to build an Oratory and dwelling houses.

The Friars of the

Holy Cross, also called the Crutched, Crouched, or Crossed Friars, were not

one of the four principal Mendicant Orders of Friars and they struggled in

their bid for recognition. They began to settle in York at the beginning of the

reign of Edward II but were discountenanced by the Archbishop of York.

However four

years later, in the Inquisition Post Mortem on the death of Thomas Wake in

1349, Farndal. A house with a chapel of the brethren of Charity (de sancta

Caritate)(“of holy charity”) was of the avowson of the said Thomas (referring

to Thomas Marcand of Aton) and the said brethren hold their tenements there

of the said Thomas in frank almoin.

The Brethren

of Charity, de Sancte Caritate, "of Holy Charity”, do not appear

elsewhere in the medieval records. The Charters and Patent Rolls of this period

do not refer to any grant of land in Farndale to a religious community other

than these references. Religious bodies were often granted land for building

which they never in fact occupied. It was partly in an attempt to prevent

abortive grants of land that Edward I passed the Statute of Mortmain in

1279. Yet these Brethren of Holy Charity do seem to have had a chapel at

Farndale.

The 1345

record indicates that the chapel was to have been built in the moor of

Blackhowe in Farndale. This suggests that the chapel was not built in the

valley, but on Blakey Howe. It has been surmised that the Lion Inn at Blakey

might have been built on the same site as the friars’ chapel.

The

Inquisition post mortem on John's estates recorded 'Advowson of the chapel

of the brethren of the Holy Trinity in Farndale. Trinity for Charity may have been a

scribe's error. In the later Middle Ages there was some confusion between the

Trinitarians and the Friars of the Holy Cross. It is therefore possible that

the Brethren of Holy Charity who had their house and chapel in Farndale, were

the same people as the Crutched Friars to whom Thomas Wake gave land in 1347.

There was

therefore likely to have been a friary established above Farndale at the windy

Blakey Howe in about 1345.

By 1349,

merchant ships transported rats carrying the black death to Britain. The black

death soon swept through the villages in the south and then the north of

Britain. Soon it swept through most

villages in Britain.

Plantagenet

Farndale

Thomas Wake

died childless in 1349 as the Black

Death swept across the country. Presumably the date was not a coincidence.

His sister

was Margaret Wake.

Margaret’s

first husband, John Comyn, had been killed at Bannockburn in 1314. A decade

later in 1325 Margaret had married Edmund of Woodstock, the youngest son of

Edward I. So Margaret Wake of Stuteville descent, had married into the

Plantagenet royal dynastic line. In modern parlance, she was punching above her

weight.

When Edward

I had died, Edmund loyally supported his half brother, Edward II. Even as

Edward II’s popularity grew, after failures in France and favouritism of the

unpopular Piers Gaveston and the Dispenser family, Edmund stayed loyal. In 1321

he was made Earl of Kent and assumed vast landholdings with that title. It was

at this time that Edmund married Margaret Wake.

Unpopularity

then led to Queen Isabella’s plot with her lover, Roger Mortimer, which led to

invasion and Edward II’s relinquishment of the throne to Edward and Isabella’s

son, Edward III. Edmund, who had steadfastly supported Edward, had finally

joined the Mortimer rebellion, despising the Dispensers more than he distrusted

Mortimer. He was initially rewarded by the new regime with new lands previously

held by the Dispensers.

Edward III’s

minority was under the de facto control of Mortimer. The Mortimer

administration itself became unpopular for its maladministration and failures

in the struggle with Scotland. In 1328, Edmund and his brother Thomas, Earl of

Norfolk, joined with Henry of Lancaster in a plot against the Mortimer regime,

but had cold feet when success was not assured.

Then, in

1330, a second plot against the royal regime by Edmund was uncovered. Edmund

was condemned to death as a traitor. His lands were stripped from him. The

disgraced Margaret and her young family were placed under house arrest at

Arundel Castle in Sussex.

And yet, it

was probably the execution of the young King, Edward III’s brother, that

stirred the King to realise the threat that his Protector posed to his own

regime. Aided by his close companion William Montagu, 3rd Baron Montagu, and a

small number of other trusted men, Edward took Mortimer by surprise and

captured him at Nottingham Castle on 19 October 1330. Mortimer was executed and

Edward's personal reign began. Among the charges against Mortimer was that of

procuring Edmund's death, and the charges against the late Earl of Kent were

annulled.

So it was

later in the same year that Margaret Wake’s husband had been executed for

treason, and her family shamed, that she had the Kent lands returned to her, as

Countess of Kent.

Margaret was

a powerful woman, married into the Plantagenet dynasty, with extensive

landholdings, though having experienced the trauma of her husband’s execution

and her short-lived shaming as the widow of a traitor.

When her

brother Thomas Wake died of the plague in 1349, Margaret Wake assumed the old

Stuteville lands, including Farndale. By now the Countess of the vast

landholdings of the duchy of Kent, these lands were added to her now vast noble

landholding.

Margaret’s

misfortune had not ended however, and only four months later, on 19 September

1349, Margaret too, died from the plague.

The old

Stuteville lands passed to the son of Margaret and Edmund, John Wake, who

became the third Earl of Kent in September 1349. By 1352, he too was dead. The

plague was taking its toll on the family.

It was

therefore that in 1352, the twenty six year old Joan, brother of John, daughter

of Margeret Wake and the executed Edmund of Woodstock, granddaughter of Edward

I, brought up in the royal court, inherited the titles of Fourth Countess of

Kent and Fifth Baroness Wake of Liddell, and with it the Farndale lands.

Meantime, in

a sign that social distancing was not taken so seriously in the Yorkshire

dales, despite the Black Death, an Inquisition

taken at Kirby Moorseved in the twenty third year of the

reign of Edward III, in 1350, recorded a yearly fair,

and Wednesday market in Farndale by that time.

The most

beautiful woman in all the realm of England

It is worth

a diversion to savour in the life of Farndale’s most exotic proprietor who took

title to the Stuteville lands when her brother John died in 1352.

Farndale was

part of the lands which fell to the Stuteville/Wake and Kent heir, Joan Plantagenet

(1328 to 1385), who came to be known as the Fair Maid of Kent, the daughter of

Edmund of Woodstock, 1st Earl of Kent, and Margaret Wake, 3rd Baroness Wake of

Liddell.

The young

Joan had been brought up, a royal princess in the Plantagenet court of Edward III and

her domain was the royal courts in southern England and France. She was cousin

of the King. She was under the charge of Queen Philippa.

In 1340,

aged only thirteen, Joan had secretly married the twenty six year old Thomas Holland,

her Knight. She had not first gained royal consent, which she was required to

do as a royal princess. Shortly after the wedding, Holland left for the

continent as part of the English expedition into Flanders and France. The

following winter, while Holland was still overseas, Joan's family arranged for

her to marry William Montagu, son and heir of William Montagu, 1st Earl of

Salisbury, who had helped Edward secure his throne from the Mortimer regime. It

is not known if Joan confided to anyone about her first marriage before

marrying Montagu, who was her own age. Later, Joan suggested that she had not

announced her existing marriage with Thomas Holland because she was afraid it

would lead to Holland's execution for treason. She may also have been influenced

to believe that the earlier marriage was invalid by the Montagu family and her

ambitious mother, Margaret Wake.

William

Montagu's father died in 1344, and William Montagu became the 2nd Earl of

Salisbury.

When Holland

returned from the French campaigns in about 1348, his marriage to Joan was

revealed. Holland confessed the secret marriage to the King and appealed to the

Pope for the return of his wife. Salisbury held Joan captive so that she could

not testify until the Church ordered him to release her. In 1349, the

proceedings ruled in Holland's favour. Pope Clement VI annulled Joan's marriage

to Salisbury and Joan and Thomas Holland were ordered to be married in the

Church.

Joan had

relinquished her place in the Salsbury title, for the lowly, though impressive,

knight, Thomas Holland.

Joan and

Thomas had five children.

So it was

Joan, the royal princess, who inherited the titles 4th Countess of Kent and 5th

Baroness Wake of Liddell after the death of her brother John, 3rd Earl of Kent,

in 1352. Far to the north from the royal court, part of her landholdings

included Farndale.

It is not

likely that she ever visited her lands at Kirkbymoorside and so sadly was

probably never seen in Farndale. If she did visit her lands there, perhaps

riding side saddle as was her want, she would have caused a stir. She was more

interested in royal politics and courtly intrigue than in the tedious

administration of her distant landholdings.

In 1353 an

Inquest taken at York during Edward III’s reign confirmed Joan’s Stuteville

holdings in Kirkbymoorside. Kirkeby Moresheved. The manor with its members in

Farndale, Gillyngmore, Brauncedale and Fademore (extents given, with field

names), held of John de Moubray by service of 1½ knights’ fees. The extent of

Kirkeby includes a weekly market on Wednesday and a fair on the feast of the

Nativity of the Virgin; and the manor is charged time out of mind by the

ancestors of the earl with 26s. 8d. yearly to the prioress of Keldholm and 13s.

4d. yearly to the vicar of the church of Kirkeby for tithe of the mill.

Decrease in value of land &c. through the pestilence.

The

Wednesday market was continuing and a fair on Marymas, 8 September each year.

Thomas

Holland, whose modest possessions were unlikely to have kept Joan in the style

to which she was accustomed, but whose military charm seems to have

nevertheless entranced her, therefore took title to Joan’s lands, though he was

not summoned to take the formal title of Earl of Kent until 1360. With the Kent

and old Stuteville landholdings, the couple could live more luxuriously.

The years of

happy marriage between Thomas and Joan were short. By 1154, Thomas had been

sent to Brittany to represent the King’s interests during the minority of the

Duke of Brittany. By 1359 he was appointed captain general of England’s

possessions on the continent. Then, on 28 December 1360, he died of illness in

Normandy.

On the death

of Thomas Holland in 1360, the Close Rolls of 20 February 1361, recorded her

personal hold of Farndale. Westminster. To William de Nessefeld escheator in

Yorkshire. Order to deliver to Joan who was wife of Thomas de Holand

earl of Kent the manors of Cotyngham, Witherton, Buttercrambe, Kirkeby

Moresheved (with lands in Farndale, Gillyngmore, Brauncedale and

Fademore), Cropton (with tenements in Middleton and Haretoft), Aton and

Hemelyngton, with the members, lands etc thereto pertaining, taklen into the

king’s hand by the death of the earl, together with the issues from the date of

his death; as it is found by inquisition, taken by the escheator, that Thomas

at his death held no lands in that county in chief in his demesne as of fee,

but held the premises of right of his said wife, and that the manors of

Cotyngham, Witherton, Buttercrambe and Cropton, one messuage and 14 bovates of

land in the manor of Aton are held in chief, and the residue of that manor and

the manor of Hemelyngton of others than the king; and the king has at another

time taken the homage of the earl for the lands of Joan’s heritage by reason of

issue between them begotten.

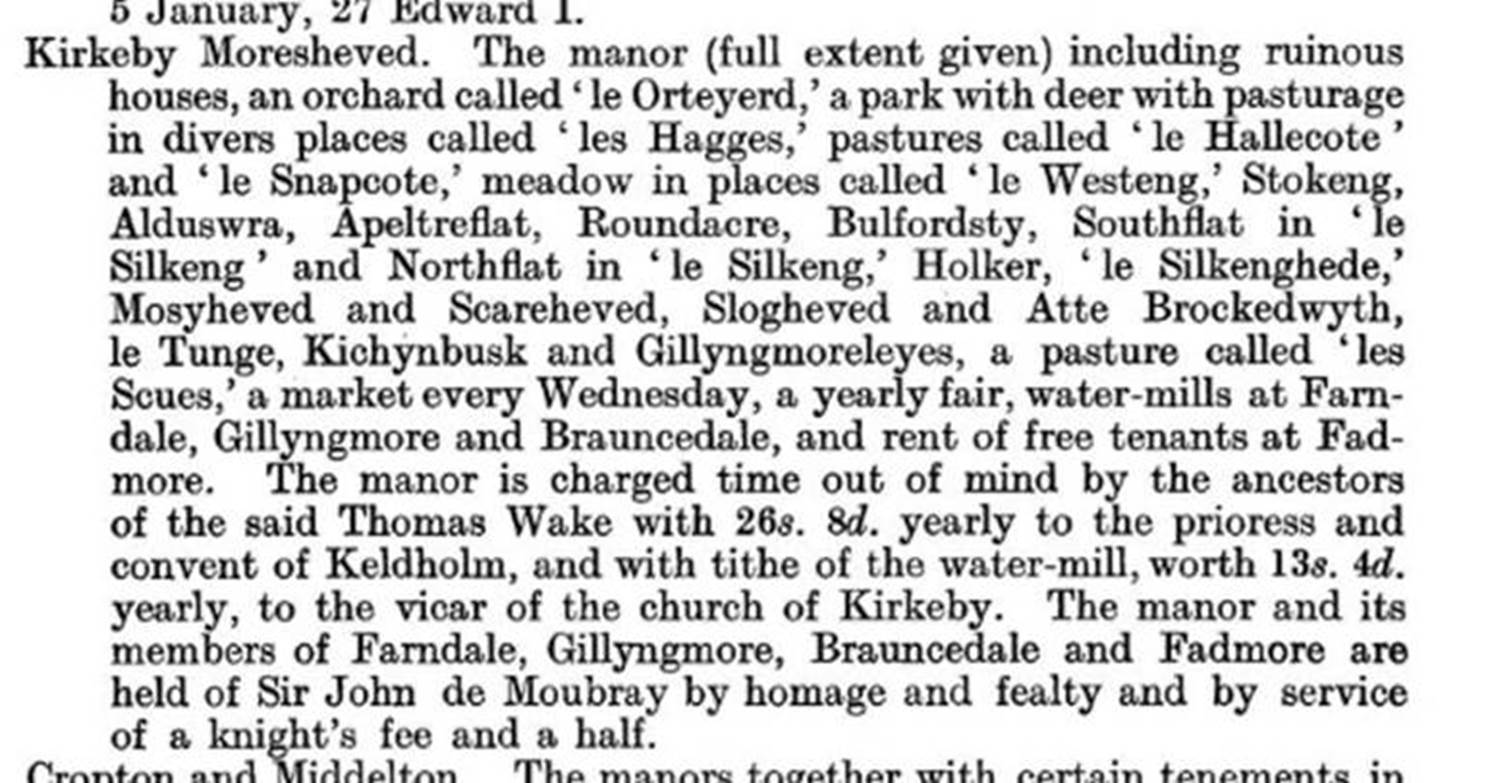

Inquest

taken at Buttercrambe, Thursday after the Purification, 35 Edward III.

Cotyngham and Wytheton. The manors held of the king in chief as of the crown by

homage and fealty and by service of a barony and by service of finding a

mounted esquire suitably armed to bear the king’s coat of mail (lorica) in the

war in Wales for forty days at his own costs, if there is war in Wales.

Buttercrambe. The manor held of the king in chief as of the crown by homage and

fealty and by service of a knight’s fee. Kirkeby Moresheved. The manor, with

lands &c. in Farndale, Gillyngmore, Brauncedale and Fademore, held of

John de Moubray by homage and fealty and by service of a knight’s fee and a

half.

So the Kent

and old Stuteville lands passed to Joan.

The lovely

Joan did not have to wait long before marrying the heir to the throne. It is

suggested that Ned, the young Prince of Wales, already had eyes for Joan, who

he had grown up with during their childhood. Joan was the King’s cousin, so Ned

was of a different generation, but there were only a few years in age between

them.

On 10

October 1361 Joan married her cousin Edward, the Black Prince, son of Edward

III, the Prince of Wales. As the Black Prince and Joan were related, the prince

also being godfather to Joan's elder son Thomas, a dispensation was obtained

for their marriage from Pope Innocent VI, though they appear to have been

contracted to marry before it was applied for. Joan was somewhat reckless. The

marriage was performed at Windsor, in the presence of King Edward III, by Simon

Islip Archbishop of Canterbury. According to Jean Froissart the contract of

marriage between Ned and his cousin Jeanette was entered into without

the knowledge of the king. The prince and his wife resided at Berkhamsted

Castle in Hertfordshire though many sources suggest it was used more as a

hunting lodge.

For a short

while Farndale was held directly by the Prince of Wales, the Black Prince

himself.

In 1365 Joan

and her new husband, the Black Prince, formally settled the Kirkbymoorside

manor on her son by her former husband, Thomas Holland, the Second Earl of

Kent, and Alice FitzAlan, his wife and their heirs, with reversion to the

prince and herself. So Joan’s direct interest in Farndale passed on to her

Holland sons. Perhaps her elevated lifestyle meant that by 1365 she was not so

bothered about retaining her northern lands in her direct ownership. The Kent

and Kirkbymoorside lands thus passed down to the line of the Hollands.

There is a

record though that the Black Prince ordered his keeper of the Farndale wood to

deliver a single oak, suitable for shingles, for the roofing of Gillamoor

chapel. So Joan and the heir to the throne did retain some interest over the

Farndale lands. Farndale had after all been a royal hunting ground.

Joan and the

Black Prince had two sons of their own, Edward of Angouleme (1365 to 1370) and

Richard who became Richard II of England.

Edward the

Black Prince was the son and heir apparent of King Edward III. He was famously

encouraged by his father to earn his spurs. Froissart's

Chronicles referred to the Black Prince at the battle of Crécy in 1346, and

the instruction given by his father Edward III that those with the prince

should suffre hym this day to wynne his spurres, often quoted as Let

the boy win his spurs.

The French

chronicler Jean Froissart called Joan en son temps la plus belle de tout la roiaulme d'Engleterre et

la plus amoureuse,

"the most beautiful woman in all the realm of England, and the most

loving", although the immortal title of the "Fair Maid of Kent"

seems to have been adopted later, though Froissant did refer to her as cette

jeune damoiselle de Kent. She was described in the Herald Chandos’ Le

Prince Noir, as Une dame de grant pris, Qe belle fuist, plesante et

sage, “a lady of great worth, who was beautiful, pleasant, and wise.”

It was Joan

whose honour, it was later suggested, Edward III protected in a famous incident

which was claimed to have given rise to the motto of Edward’s new Order of the

Garter, honi soi qui mal y pense. The story goes that Edward III was dancing with Joan of Kent,

his first cousin and daughter-in-law, at a ball held in Calais to celebrate the

fall of the city after the Battle of Crécy. Her garter slipped down to her

ankle, causing those around her to laugh at her humiliation. Edward placed the

garter around his own leg, saying, Honi soit qui mal y pense. Tel qui s'en

rit aujourd'hui, s'honorera de la porter, "Shame on anyone who thinks

evil of it. Whoever is laughing at this thing today will later be proud to wear

it." The story is almost certainly apocryphal, and has also been

associated with the Countess of Salisbury, but it is the founding myth of the

Order of the Garter. Thomas Holland became one of the small number of selected

founding knights who joined to order in 1348. Joan herself was made a Lady of

the Garter in 1378.

The incident

clearly caused hilarity in the most famous satirical history book which was

written in the 1930s.

The

impression of Joan’s seal depicted a lady riding on horseback sideways, a style

which she is said to have been the first to adopt.

By 1371, the

Black Prince was no longer able to perform his duties as Prince of Aquitaine

due to poor health. Joan and her prince returned to England, shortly afterwards

burying their eldest son. In 1372, the Black Prince attempted a final but

abortive campaign in an effort to save his father's French possessions, but the

exertion was too much. He returned to England for the last time on 7 June 1376,

a week before his forty-sixth birthday, and died in his bed at the Palace of

Westminster the next day.

Joan's son

Prince Richard was now next in line to succeed his grandfather Edward III, who

died on 21 June 1377. Richard was crowned as Richard II the following month at

the age of 10. As Queen Mother, Joan exercised considerable influence during

the early years of her son's reign. She enjoyed respect as a venerable royal

dowager.

Early in his

reign, the young King faced the challenge of the Peasants' Revolt. The

Lollards, religious reformers led by John Wyclif, had enjoyed Joan's support,

but the violent climax of the popular movement for reform reduced the feisty

Joan to a state of terror. Nevertheless, on her return to London from a

pilgrimage to Thomas Becket's shrine at Canterbury Cathedral in 1381, when she

found her way barred by Wat Tyler and his mob of rebels on Blackheath, she was

not only let through unharmed, but she was saluted with kisses and provided

with an escort for the rest of her journey.

In January

1382, Richard II married Anne of Bohemia, daughter of Charles IV, Holy Roman

Emperor and King of Bohemia.

Joan died on

7 August 1385 aged 57, at Wallingford Castle. She was buried beside her first

husband, Thomas Holland, as requested in her will, at the Greyfriars in

Stamford, Lincolnshire. The Black Prince had built a chantry chapel for her in

the crypt of Canterbury Cathedral in Kent, where he himself had been buried

with ceiling bosses sculpted with likenesses of Joan’s face.

There are plenty of historical novels written about the fair maid including The Shadow Queen, 2018 by Anne O’Brien; The Fair Maid of Kent, 2017 by Caroline Newark and The First Princess of Wales, 2020 by Karen Harper. They provide fictional depictions to fill the unknown gaps between the historical evidence, of Joan of Kent's life at the English court in which her mother, Margaret is a supporting character. There are also many biographies such as by Anthony Goodman, 2017.

The Fair

Maid did not likely know Farndale, but it was a part of her possessions and she

adds some glamour to our story. Her life must have impacted on those who lived

there, especially in the thirty years between 1352, when she took title to the

lands, and 1385, when she died.

Farndale

in the later Middle Ages

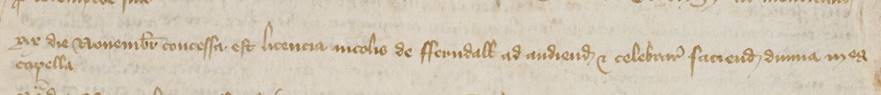

The York Archbishop Registers on 19 November 1388 recorded licence for the inhabitants of fferndall

to have masses celebrated in the chapel of Farndale.

That there

was a chapel in Farndale is evidenced by its being marked on Christopher

Saxton's 1577 map, and also by reference to it in the will of William

Folancebye made on 3rd May 1537, ''also I bequethe to Farnedall chapell ij

torches and ij yowes'. This is the earliest reference to a chapel in the

dale. It is possible that De Willelmus Clerico, William the Clerk, named in the

Lay Subsidy Roll of 1301 could have been the chaplain there by the turn of the

fourteenth century.

In 1397

Joan’s son, Thomas Earl of Kent died and Alice was left in possession of his

lands. Of Alice’s sons, Thomas the Elder was beheaded as a traitor in 1399 and

his brother Edmund died before his mother in 1408, when the earldom of Kent

fell into abeyance.

The Wake

line ended in three co-heiresses, one of whom married the Earl of Westmoreland,

who succeeded to the barony of Kirkbymoorside, and it remained in the

possession of this family until 1570.

Whilst the Stutevilles and their

successors the Wakes had lordship

over Kirkbymoorside and Farndale since about 1200, they had strictly held

those lands as sub tenants still to the

original Mowbray interest who continued to hold the tenancy in chief of the

King. In 1397, Thomas Mowbray, the twelfth baron, was created 1st Duke of

Norfolk, but in the following year he was accused of treason. He was banished

by Joan’s son, Richard II, and his estates were forfeited. The manor of

Kirkbymoorside and with it Farndale reverted into the King's hands. The tenancy

in chief in the manor then reverted more formally to the Holland family, the

Earls of Kent who were closely related to Richard II.

It is in the

inquisition post mortem held into the estates of Alice, late wife of Thomas

late Earl of Kent, in 1415, that we read The said Alice also held the

advowson of the chapel of the Brethren of Holy Charity in Farndale, worth 10s a

year. It seems that the friary had continued on Blakey Howe since it had

been established in 1345. It seems likely therefore that there was a chapel in

the valley where the inhabitants of the dale worshipped, and a friary above the

dale at Blakey Howe, with its own chapel.

Whenever the

Farndale chapel might have been founded, the medieval inhabitants of Farndale

could also attend the chapel of ease at Gillamoor whose parent church was the

parish church of Kirkbymoorside. They also had access to Kirkdale, which might

have been their ancestral home.

Until the Dissolution

of the Monasteries, the Prior and Convent of Newburgh Priory provided priests

to both the churches at Gillamoor and Kirkbymoorside. It was for the repair of

the church at Gillamoor that the Black Prince, in December 1363 ordered John

Forestier, keeper of the wood of Farendale to deliver an oak suitable for

'shengel' towards roofing.

After the Black Death and a series of

famines, depopulation had led to a food excess, which was sold for profit to

create a new middle class and led in time to greater prosperity. As taxes,

continued to be levied, particularly those taxes imposed after 1349, resistance

grew, leading to the

Peasants' Revolt in 1381, which the Fair Maid had encountered with her son.

Wat Tyler demanded There should be equality among all people save only the

king. There should be no serfdom and all men should be free and of one

condition. We will be free forever, our heirs and our lands. Richard II had

at first greeted the protestors and suggested concession, but before long he

had supposedly declared Rustics you were and rustics you are still; you will

remain in bondage, not as before but incomparably harsher. The disdain of

Joan’s son for the rural community became apparent.

Whilst the

rebel leaders were executed, the changed circumstances meant that serfdom was

slowly replaced in England, so that an alternative path was pursued in England

to that which many of the European nations continued to follow.

The young

men of the dale meantime continued to prove an unruly lot. In 1371, the

Prioress of Keldholm entered a complaint in the Court of Common Pleas against

Thomas del Ker of Farndale for breaking her close and houses at Morehous in

Kirkebymoreshead, and taking goods and chattels to the value of 40s.

In 1372 John Porter, Hugh

Bailly and Adam Bailly, ranging rather farther afield, were accused by William

Latymer, of entering his free chase of Danby hunting therein without licence

and taking deer therefrom and assaulting his men and Servants.

In 1396,

Robert de Wodde of Farndale was pardoned for the death of John Hawlare of

Kirkbymoorside whom he killed there on Monday the eve of the Purification,

in the eighteenth year. The Wood family appears thus early in Farndale

records and their name occurs regularly in wills throughout the sixteenth and

seventeenth centuries and subsequently on the rent rolls and field books of the

Duncombe estate.

About the

same period, in the closing years of the fourteenth Century, a certain Thomas

Wolthwayt of Farndale was accused by Hugh Gascoigne, the parson of Stonegrave, of

breaking into his close and houses at Stonegrave, assaulting him, fishing in

his several fishery there and taking away fish and goods and chattels to the

value of 200 marks, as well as 1000 marks in money, and assaulting his men and

servants.

There were

others who terrorised the wild and lonely moors above Farndale, including John

of Wighall and John Webster of Beverley who were indicted in 1361 as common

robbers and thieves who used to lie in wait on Blakey Moor. The list

of their crimes included robbing William Chapman of Battersby, draper, of five

marks in silver; robbing John of Durham, at a spot in the moor near Ingleby

Greenhow of 17s and 6d; and other similar attacks on wayfarers. They were both

hanged.

Perhaps

though we have to interpret these records as overly emphasising the law

breakers, whilst ignoring the many folk of the dale who continued to go about

their everyday lives.

By 1422,

when Henry VI came to the throne, Farndale had been assigned to Elizabeth Neville,

and for nearly a hundred and fifty years the Nevilles, as Earls of Westmorland,

were lords of the manor. A family

of Farndale descendants lived at Sheriff Hutton by then.

Some from that family fought in the

Scottish and French Wars with Richard II and Henry V. That family lived in

the main ancestral home of the Neville family, and of Richard III, during the

period of the

Wars of the Roses.

The

glamourous lives of the Farndale overlords was unlikely to have significantly

changed the daily life of the Farndale inhabitants. The life of ordinary folk

in Ryedale in the fourteenth century was the subject of a 1976 article in

the Ryedale Historian. The inhabitants of the dale no doubt continued to spend

most of their time in agricultural labour and the challenges of daily

existence. There is no evidence from signs left in the land or in the field

names of Farndale that the three field system of agriculture operated in

Farndale. The chief crop was probably barley which would have been taken to one

or other of the two

mills in the dale. By 1334, Simon the Miller had been succeeded by two recorded

millers and in 1553 when John Wood made his will he wrote, also I give to

the mendyng of the upper mylne bridge iiij pence and to the mending (sic) of

the nether mylne bridge iiij pence. The upper mylne is the present

site of High Mill, below Church Houses, and the nether mylne is Low

Mill. Both these mills continued operated well into the twentieth century. They

were naturally watermills, built on the banks of the Dove, but in 1560 there

were also in the manor of Kirkbymoorside six windmills though there is no

evidence that windmills were built in Farndale.

In 1446

William Thornburgh of Farndale was appointed with four other commissioners to

levy and collect one of Henry VI's taxes throughout the North Riding. He must

have been a man of some standing and substance. And William Folancebye left two

torches and two ewes to Farndale chapel, bequeathed more substantial gifts to

his relatives, also I bequethe to John Folancebye ii furred gownes, one

furred with white lambe and the other with blacke lambe. Also I bequethe to the

said John Folancebye my sword, one velvet dublet, (and) my best horse. - also I

bequethe to Robert Folancebye, my brother, one russet gowne.

When, in

1569, the rebellion known as the Rising of the North had been crushed, the

estates of its leaders amongst whom the Earl of Westmorland was one, were

forfeited to the crown. Three commissioners were appointed by Elizabeth to

survey these estates and this survey has become known by the name of the chief

of these commissioners as Humberston's

Survey. His account of the manor of Kirkby contrasted the wealth between

the inhabitants of the dales and the town of Kirkbymoorside itself.

Humberstone’s

survey of Farndale in 1570 recorded seventy one tenements in Farndale, forty

on the east side and thirty one on the west, together with two mills and a few

cottages paying altogether just over £54 in rent. It tells us that the

hamlets and dales of Farndale, Bransdale, Fadmore and Gillamoor were inhabited

with many wealthy and substantial men and they have very good farms by reason

of the great and large commons and wastes; and all the tenants except the town

of Kirkby hold their farms and tenants by indenture for terms of years whilst

the town of Kirkby is a market town inhabited all with poor people and they

hold their cottages by copy of court roll and they have no lands or other

commodities to their cottages.

The view

and surueie of the lordship of Kyrkeby Moresyde, in the county of Yorke,