Act 6

Game of Thrones

1066 to 1200

The Kirkbymoorside (Chirchebi)

Estate from the eve of the Norman Conquest

We now find ourselves

in the century and a half before our ancestors first settled in Farndale. The

story takes us from the eve of the Norman Conquest to the chess games of the

great Norman noble Houses over the lands where our ancestors lived.

|

Our Own Game of Thrones Podcast This

is a new experiment. Using Google’s Notebook LM, listen to an AI powered

podcast summarising this page. This should only be treated as an

introduction, and the AI generation sometimes gets the nuance a bit wrong

(for instance there are aspects of the relationship between the Stutevilles

and the Mowbrays that are more accurately to be found in the text and links

below). However it does provide an introduction to the themes of this page,

which are dealt with in more depth below. |

|

Some

introductory music to set the scene. |

Scene 1 – Harold and Tostig

The Final

Days

The

Anglo-Saxon-Scandinavian overlord of the ancestral lands of the Farndale family

on the eve of the Norman Conquest was Orm

Gamalson who was associated with sixty one locations, including the estate

of Chirchebi, now Kirkbymoorside, the estate which included the lands

which would become Farndale.

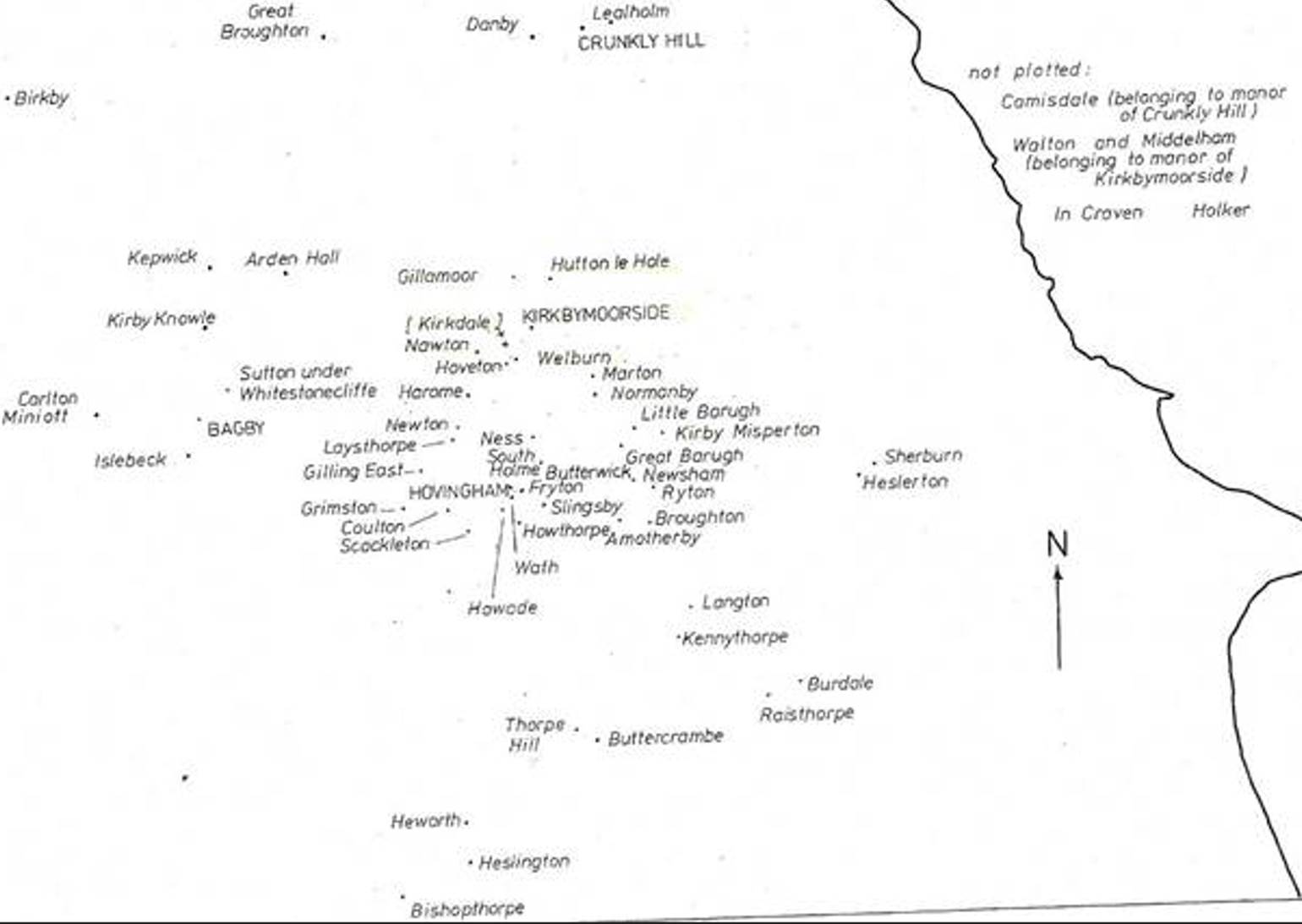

Lands of

Orm Gamalson before the Conquest

At the same

time that Orm had rebuilt Kirkdale

Minster in the decade before the Norman Conquest, Tostig Godwinson became

the Anglo-Saxon Earl of Northumbria. Tostig was the third son of the

Anglo-Saxon nobleman Godwin, Earl of Wessex and Gytha Thorkelsdóttir,

the daughter of a Danish chieftain. So he had parental associations with both Godwins and Scandinavians.

In 1051,

Earl Godwin's opposition to Edward the Confessor’s policies had brought England

to the brink of civil war. The Godwins' opposition

led Edward to banish the House Godwinson in 1051. The banished Godwin family, including

Gytha and Tostig, together with Sweyn and Gyrth,

sought refuge with his brother-in-law the Count of Flanders. However. they

returned to England the following year with armed forces, gaining support and

they demanded that Edward restore Tostig's earldom.

Three years

later in 1055, Tostig became the Earl of Northumbria upon the death of Earl

Siward. His relationship with his brother-in-law, Edward the Confessor,

improved and in 1061 he visited Pope Nicholas II at Rome in the company of

Ealdred, the Archbishop of York. Tostig’s role in Yorkshire was to strengthen

the King’s influence in this, from the south’s perspective, unruly land.

Tostig

proclaimed Earl of Northumbria

Godwin and his sons

Tostig

wasn’t popular with the Northumbrian ruling class, who were an ethnic mix of

Danish invaders and Anglo-Saxon survivors. Tostig was heavy-handed with those

who resisted his rule. He murdered several members of leading Northumbrian

families. In late 1063 or early 1064, Tostig had Orm’s son Gamal and Ulf son of

Dolfin assassinated when Gamal visited him under safe conduct. Gamal was

murdered in his house at York, probably part

of the ongoing multigenerational feud.

This might

have been the start of a period of disorder, during which Tostig changed his

allegiance in 1066 from the West Saxon house in favour of the Scandinavian

side, to die soon afterwards at Stamford Bridge.

Tostig was

frequently absent from the court of King Edward in the south and was lacklustre

in his efforts against the raiding Scots. The Scottish King was a personal

friend of Tostig, and Tostig's unpopularity made it difficult to raise local

levies to combat them. He resorted to using a strong force of Danish

mercenaries known as housecarls as his main force.

Local biases

might have played a part in his unpopularity. Tostig was from the south of

England, a distinctly different culture from the north, and Northumbria had not

been governed by a southern earl for several generations. In 1063, still

immersed in the confused local politics of Northumbria, his popularity

plummeted. Many of the inhabitants of Northumbria were Danes, who had enjoyed

lesser taxation than in other parts of England.

On 3 October

1065, the thegns of York and the rest of

Yorkshire descended on York and occupied the city. They killed Tostig's

officials and supporters, then declared Tostig outlawed for his unlawful

actions and sent for Earl Morcar, younger brother of

Edwin, Earl of Mercia. The northern rebels marched south to press their case

with Edward the Confessor. They were joined at Northampton by Earl Edwin and

his forces. There, they were met by Earl Harold Godwinson, Tostig’s older brother,

who had been sent by King Edward to negotiate with them and had not come with

an armed force. After Harold, by then the King's right-hand man, had spoken

with the rebels at Northampton, he probably understood that Tostig would not be

able to retain Northumbria. When he returned to Oxford, where the royal council

was to meet on 28 October, he had probably already made up his mind.

Harold

Godwinson persuaded King Edward to agree to the demands of the northern rebels.

Tostig was outlawed because he refused to accept the deposition of Edward. It

was likely that Harold had exiled his brother to promote peace and loyalty in

the north. This led to confrontation and enmity between the two Godwinson

brothers. At a meeting of the king and his council, Tostig publicly accused

Harold of fomenting the rebellion.

When Harold

became King in 1066, his immediate priority was to unify England in the face of

the threat from William of Normandy, who had openly declared his intention to

take the English throne.

Tostig,

however, plotted vengeance. Along with his family and some loyal thegns, he

took refuge with his brother-in-law, Baldwin V, Count of Flanders. He travelled

to Normandy and attempted to form an alliance with William, who was related to

his wife. Baldwin provided him with a fleet and he landed in the Isle of Wight

in May 1066, where he collected money and provisions. He raided the coast as

far as Sandwich but was forced to retreat when King Harold II mobilised land

and naval forces.

Tostig

therefore moved north and after an unsuccessful attempt to get his brother Gyrth to join him, he raided Norfolk and Lincolnshire. The

Earls Edwin and Morcar defeated him decisively.

Deserted by his men, he fled to his ally, King Malcolm III of Scotland. Tostig

spent the summer of 1066 in Scotland.

Then, he

made contact with King Harald III Hardrada of Norway and persuaded him to

invade England. One of the sagas claims that he sailed for Norway, and greatly

impressed the Norwegian king and his court, managing to sway an unenthusiastic

Hardrada, who had just concluded a long and inconclusive war with Denmark, into

raising a levy to take the throne of England.

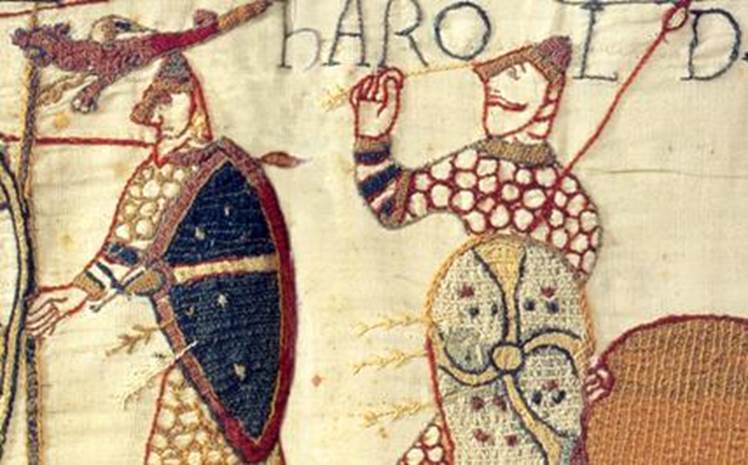

Scene 2 – Norman Conquest

Defeat

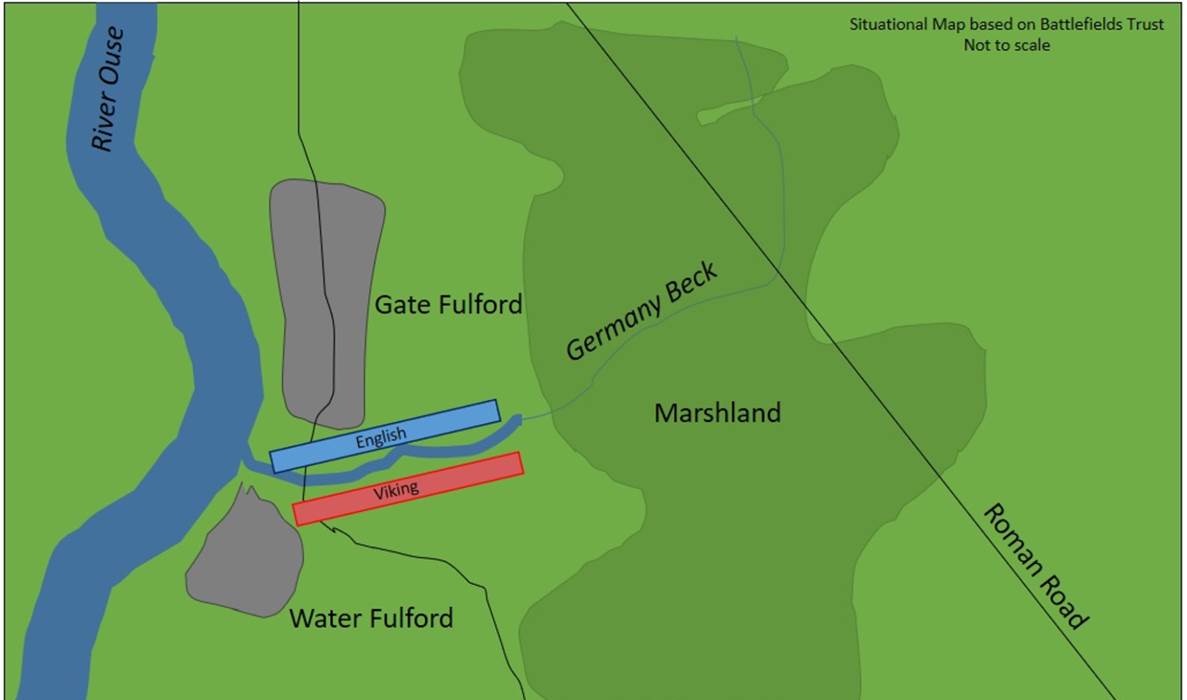

In 1066 the

Norwegian King Harold Hardrada, sailed his army up the Ouse, with support from

Tostig Godwinson and after the

Battle of Fulford, when they defeated Morcar and

Edwin, they seized York.

King Harold

of England then marched his army north to York

in four days to take the invaders by surprise. The rebels were defeated at the Battle

of Stamford Bridge, only thirty kilometres south of Kirkdale, in which

Harold Hardrada and Tostig were killed.

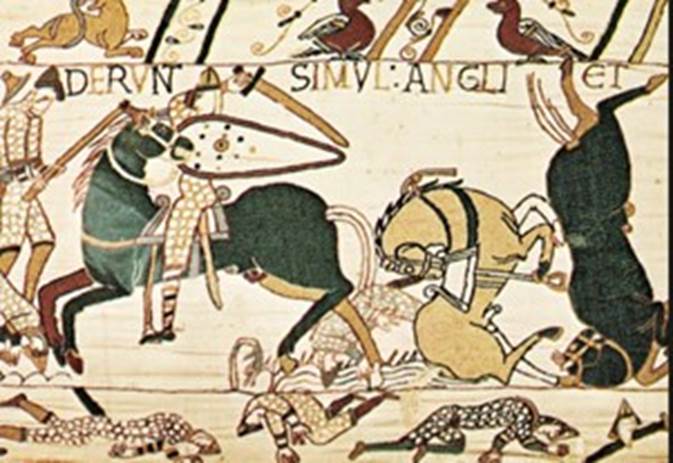

So far so

good for Harold.

The

trouble of course was that Harold then had to march his exhausted army south

again, to confront the second threat from William of Normandy, near Hastings,

and in that episode, he didn’t do so well.

After the

Conquest, Orm Gamalson was stripped of all his lands. The years immediately

following 1066 saw regime change with unparalleled thoroughness.

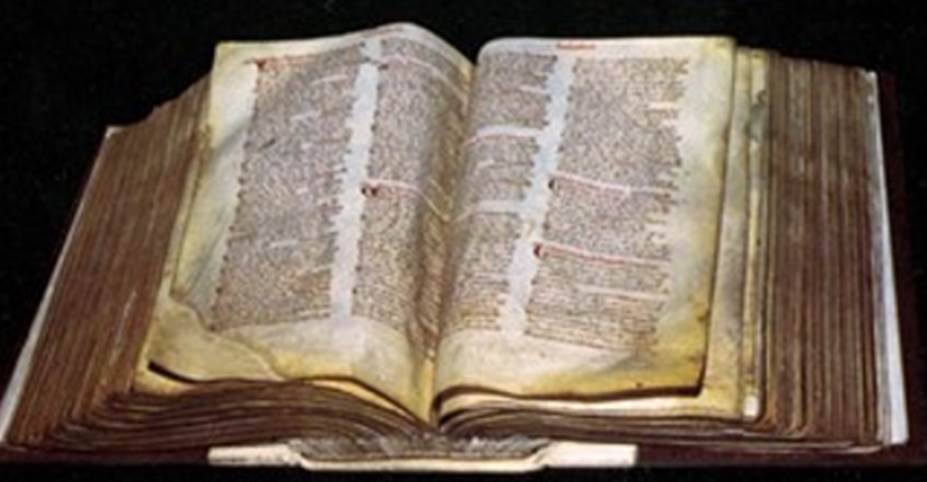

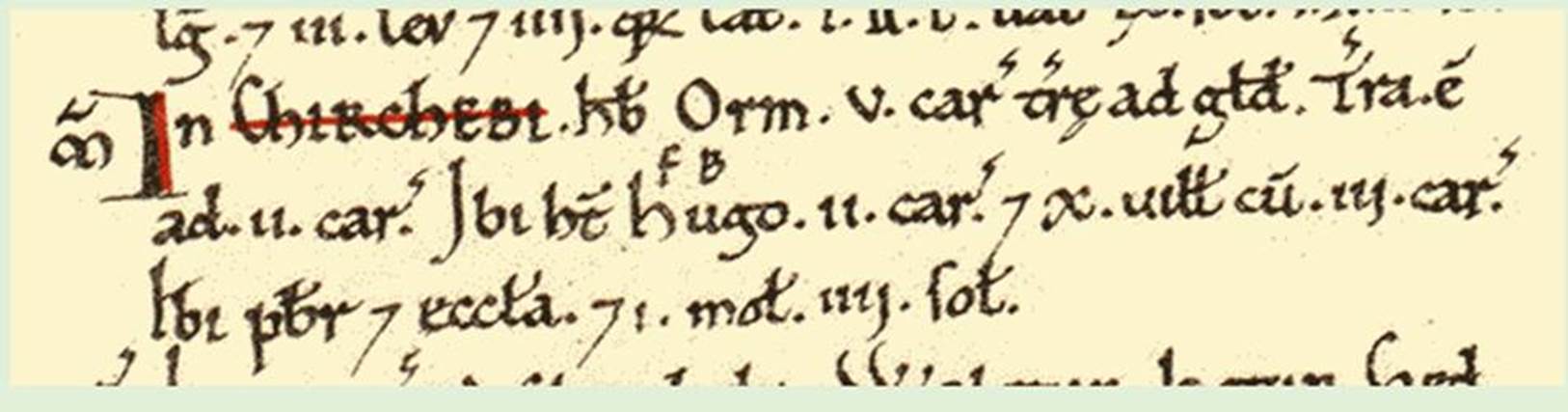

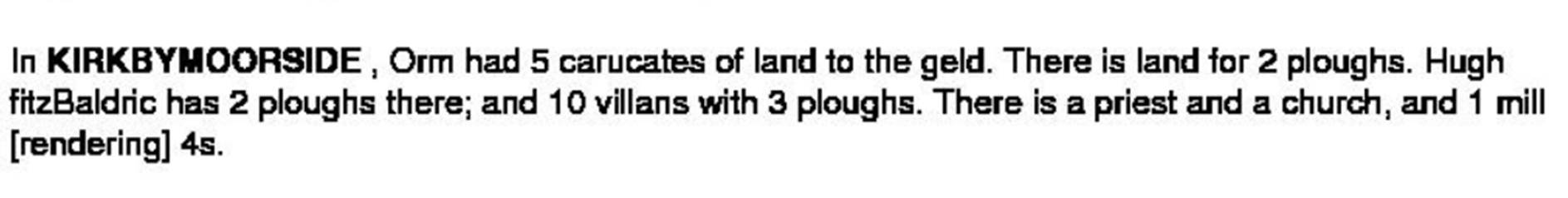

Domesday

After the

Norman invasion of England in 1066, the north was not immediately subdued under

Norman rule. However the harrying

of the north meant that the Kirkbymoorside estate was under the Norman

thumb by 1086, which was the date when the

Domesday Book recorded the extent of Norman domination two decades

after the invasion.

|

|

|

The

ruthless suppression of our ancestral home by the Normans |

As well as

recording comprehensive regime change, the Domesday Book also evidences the

administrative efficiency of the new overlords. A millennium later, that

efficiency provides us with the tools with which to have eyes on the historical

events of our very distant past. The Domesday Book, written in Latin, recorded

every important place in the country, what was there, who owned it prior to the

conquest, and to whom it was transferred after the Conquest. It established the

taxable values of all the boroughs and manors across the nation. The record was

held in two large books, which are still held by the

National Archives and accessible at Domesday

Online. The surveyors visited 13,000 villages over the course of about a

year. The whole landed property of England then totalled a value of £37,000,

which puts subsequent inflationary increases into some perspective.

We therefore

know from the Domesday Book, that Chirchebi, of which the Farndale lands

were a part, was in the possession of Orm at the time of the Conquest.

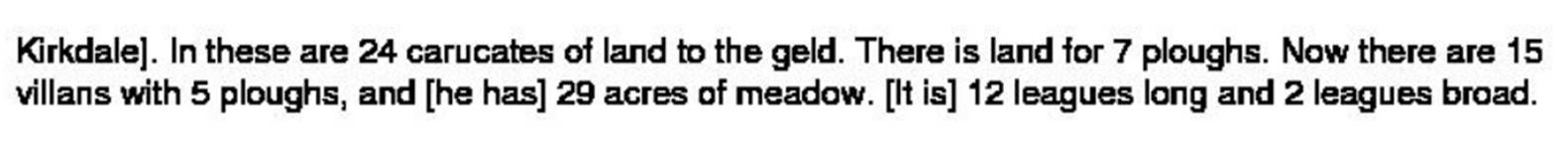

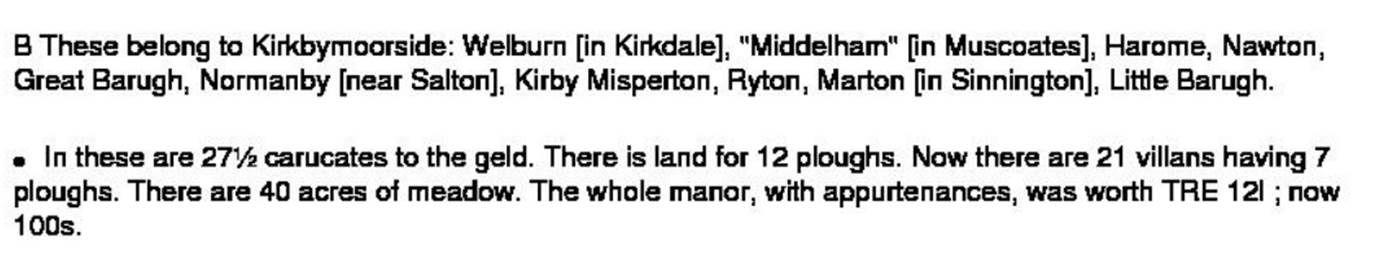

The Domesday

Book also evidences the settlement patterns across wider Kirkdaleland.

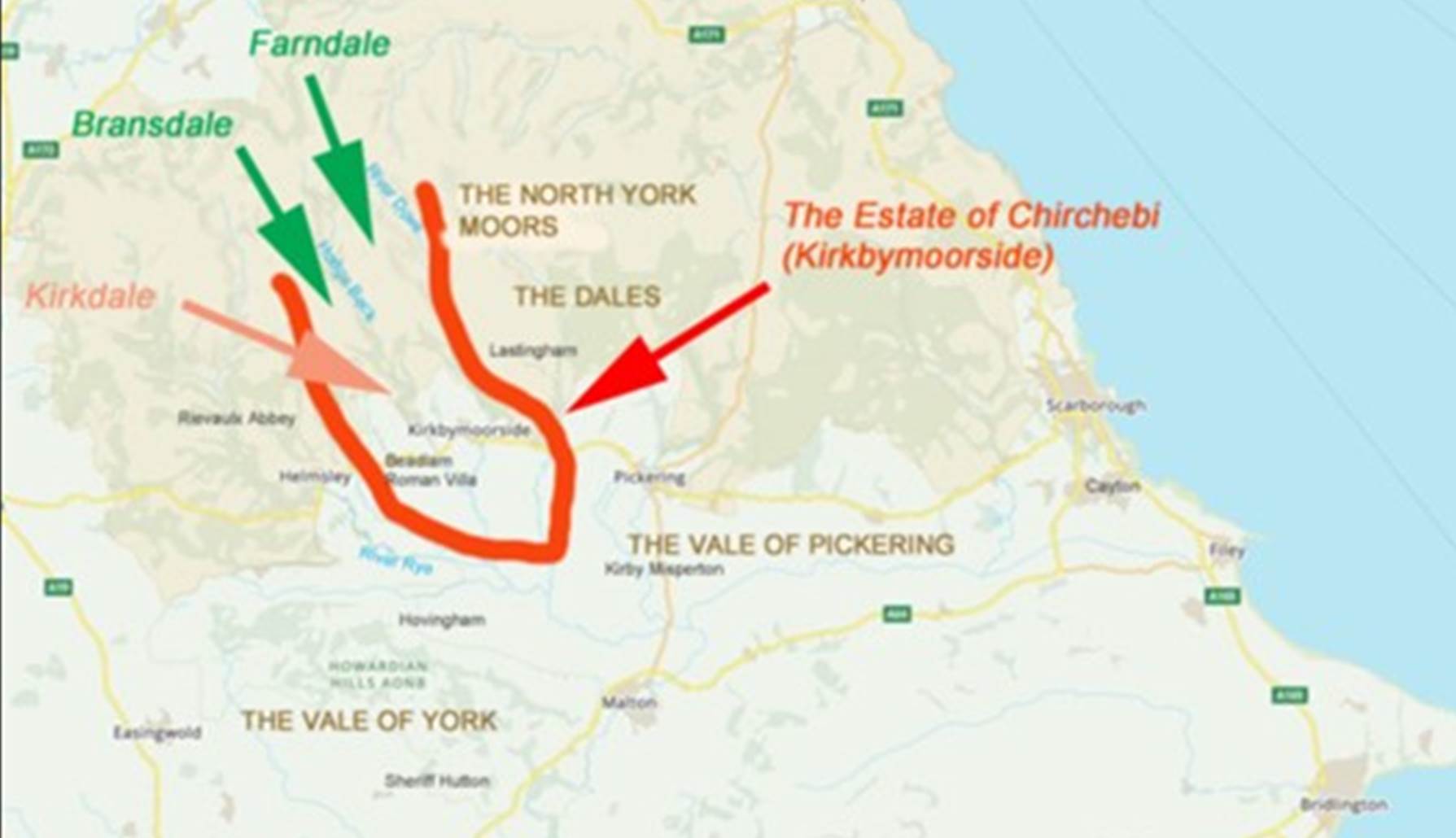

The wider

estate of Chirchebi stretched 12 leagues (about 42 miles) long by 2

leagues (about 7 miles) broad. It included Kirkbymoorside itself, and also the

wider area stretching south to Kirkby Misperton and north to Gillamoor, the agricultural lands of Orm’s day.

One of the

lands held by Orm in the Domesday record, was an area of five carucates of

cultivated land which included ten villagers, one priest, two ploughlands, two

lord’s plough teams, three men’s plough teams, a mill and a church. This was

the community around the church at Kirkdale. A carucate was a medieval

land unit based on the land which a plough team of eight oxen could till in a

year.

The wider

holding also included cultivated lands at Hutton le Hole and Gillamoor up into the southerly ends of Bransdale and Farndale, though the extent of

cultivation did not reach into those dales. It included Hoveton

believed to have been around Fadmore, Welburn, Harome, Nawton, Great Barugh,

Normanby, Kirby Misperton, Marton and Little Barugh. So this helps us to

clearly define the area of the likely home of our Farndale ancestors in Roman,

Anglo Saxon, Viking and early Norman times, before Farndale itself was

cultivated.

Most of the

northern reaches of this large Norman estate was forested and probably largely

impenetrable, and certainly not settled. It may have been used for hunting.

However the lands to the south in the northwest corner of the Vale of York,

were ancient agricultural lands.

Within the

northern part of the estate, there lay a forested valley, which was then wild

and remote, but which was nestling quietly in those woods, the place which in

time would come to be known as Farndale.

Farndale was little more than a possession, and a place which the owner himself

did not likely know, and which after the Conquest, would continue to be

possessed, transferred, perhaps sometimes hunted within, for another two

centuries.

So our

ancestral home was to become the tactical theatre of two great noble houses to

play their political manoeuvres across. Our ancestors then must have been

pawns, crushed or saved, at the whims of the noble houses.

Scene 3 – The Games the Noblemen Play

The Noble

Houses

The House

Stuteville 1066 to 1106

After the

Conquest, the estate of Chirchebi was forfeited to Hugh Fitz Baldric,

Hugh, the son of Baldric, a German archer who had

served William the Conqueror and became the Sheriff of the County of York in

1069. Hugh died in 1086 and the estate passed to de

Stuteville family. So in the game of Norman barons,

Kirkbymoorside started in the possession of House Stuteville.

The House

Mowbray 1106 to 1154

However the

Stutevilles were deprived of the estate of Kirkbymoorside in 1106 when it was

granted to Nigel d’Aubigny, one of Henry I’s new

men. So now our ancestors were pawns to the whims of the House Mowbray.

|

The

descendants of Robert de Stuteville to whom our ancestors owed their

allegiance in the eleventh and then from the late twelfth century |

|

The

descendants of Nigel D’Aubigny to whom our ancestors owed their allegiance in

the twelfth century |

|

The Royal Line and the Noble Houses The

relationship between the Royal Dynasties of England and the Noble Houses who

directly influenced our family history |

On Nigel d’Aubigny death in 1129, Roger became a ward

of the Crown and Gundreda administered the estate on

his behalf.

It was Roger’s mother Gundreda, administering the estate on behalf of her under

aged son Roger de Mowbray, who had made a grant of lands which included Middelhoved in Farndale to the sons of St Ecclesiff. The exact date of this grant is unclear from the

Rievaulx Chartulary where it is recorded, but it must have been prior to 1138

when Roger took his majority. On reaching his majority, in 1138, Roger de Mowbray took

title to the lands awarded to his father by Henry I both in Normandy including Montbray, as well as the substantial holdings in Yorkshire

and around Melton.

Roger de

Mowbray was a supporter of King Stephen, with whom he was captured at Lincoln

in 1141. The Mowbrays were significant

benefactors of several religious institutions in Yorkshire. In 1154, the name Farndale appeared for the first

time in the Chartulary of Rievaulx Abbey when Roger de Mowbray, gave

land to the abbey, which included Midelhovet and Duvanesthuat

in Farndale. This story is told in Act 1 of the Farndale

Story.

The lands

around Farndale, which Bede had described as

a land of monsters, of wild beasts and men who live like wild beasts,

was finally being tamed.

A period of

transition between House Mowbray and House Stuteville 1154 to about 1200

In that same

year 1154, Robert de Stuteville, grandson of the first Robert de Stuteville,

laid claim to the barony which had been forfeited by his grandfather. Roger

gave him Kirkbymoorside for 10 knights’ fees in satisfaction of his claim. This

arrangement however was not ratified in the King’s courts. This was the start

of a refreshed interest in the Kirkbymoorside lands from the House of the de Stutevilles.

At about the same time Robert gave to

Saint Mary's Abbey, who held the nearby Manor of Spaunton,

as much timber and wood as they required together with pasture and pannage of

pigs in Farndale. The records suggest that Farndale was provided primarily as a resource

of timber and pasture in the mid twelfth century, with limited evidence of

settlement.

Roger de Mowbray supported the Revolt of 1173 to 1174

against Henry II and fought with his sons, Nigel and Robert, but they were

defeated at Kirkby Malzeard and Thirsk.

The Stutevilles came back into favour with the

accession of Henry II and Roger de Mowbray was compelled to hand back

Kirkbymoorside, along with many others fees.

Robert III de Stuteville died in 1186.

The arrangement of 1166 between Roger

de Mowbray and Robert III de Stuteville had not been not ratified in the King's

courts, and the dispute broke out again between William de Stuteville, son of

Robert, and William de Mowbray, grandson of Roger, in 1200. However in time,

William de Mowbray confirmed the previous agreement and gave 9 knights' fees in

augmentum.

The House Stuteville from 1200

Robert de Stuteville had given the

nuns of Keldholme the right of getting wood for burning and building in

Farndale, and in or about 1209 the Abbot of St. Mary's obtained from King John

rights in the forest of Farndale which the king had recovered from

Nicholas de Stuteville. Keldholme Priory had right of pasture in Bransdale and

Farndale by grant of its founder, Robert de Stuteville.

In 1216, Joan de Stuteville was born,

the heiress of the Stuteville estates. She married Hugh Wake, feudal lord of

Bourne and later Hugh Bigod, Chief Justice of England, but as a widow she

continued to be known as Joan de Stuteville, the Lady of Liddell.

It is during

the time of Joan de Stuteville, that we meet the first settled inhabitants of

Farndale. It was now the Stutevilles who were the overlords of the

Kirkbymoorside estate and therefore of the lands of Farndale during the

following centuries, as our ancestors started to work on the land there.

By the mid

fourteenth century another Joan of Stuteville descent, had inherited the

estate. She married Thomas Holland, made Earl of Kent in 1360, and Joan became

known as the Fair Maid of Kent.

Later Joan married Edward the Black Prince and their son was Richard II.

You could

now remind yourself of Act 1 – the Cradle,

which tells of our family’s settlement in Farndale. Or you could go straight to

Act 7 – the

Poachers of Pickering Forest, to pick up the story with the second

generation of known ancestors.

Before you

do that you could:

Read about the House Stuteville

or just

There is a

are research notes with a chronological history of Farndale, with source

material, including its Norman history on the Farndale page.