Medieval Farming

Medieval rural lives

Medieval

Farming

After the

Norman Conquest a new landed elite resettled the landscape with freeholders,

villeins and cottagers. The bondsmen were settled as unfree men, sometimes

referred to as serfs or villeins. The Norman, Fleming and Breton landowners

formed a new ruling class of manor lords. Freemen were sometimes created in

return for service. Roger de Mowbray

settled freeholds near Thirsk on his butler, usher, cook, baker and musicians.

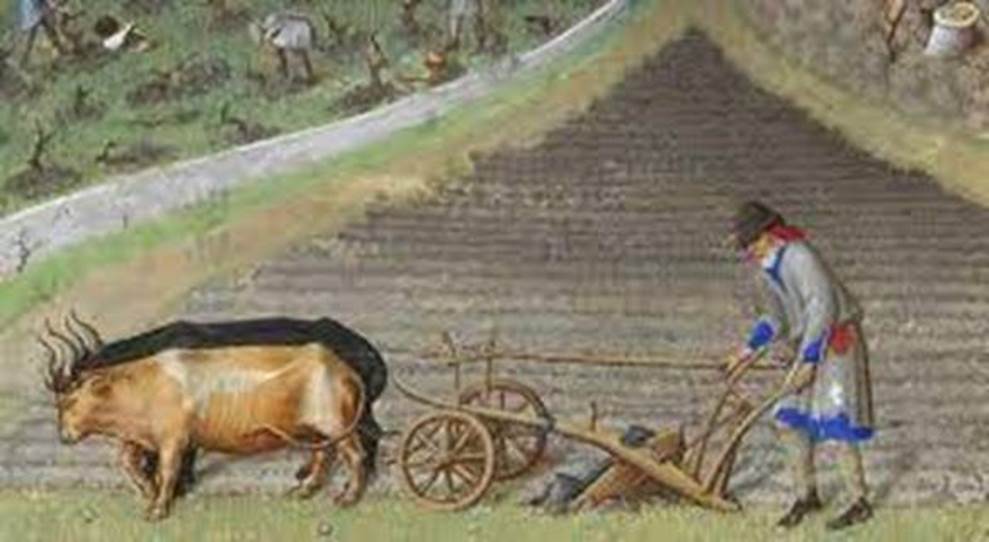

The Norman

conquest broke the continuity of ploughing for a period, but then there was a

recovery and the old fields were quickly restored.

At this time

settlements of bondsmen and villeins worked two or three adjoining fields,

which were each sub divided into a dozen or so furlongs. Each furlong was a

section of the larger field usually about 5 to 10 yards wide. The fields were

cultivated collectively, but each strip was cropped by the tenant. Two oxgangs

were quite commonly held by a villein.

The villages

may well have been laid anew by the Normans. Often the lord’s manor house was

at the end. Nearer to the moors, large greens with ponds, provided a source for

watering stock, as at Fadmoor.

Some land

was not included within the system of oxgangs and new thwaites or clearings

appeared including at Duvansthwaite in Farndale. Sometimes fringe land

near the main fields was cleared, often called of names.

Significant

land grants were given to the monasteries. Rievaulx soon had a significant

swathe of properties, throughout Ryedale and stretching to Teesmouth

and Filey. The monasteries tended to site their granges away from villages.

Monastic farms were a separate economic force. The sheep grange was dominant in

Yorkshire with many examples, including in Farndale,

of donations of rights to pasture a fixed number of sheep.

Our family’s

recorded history began with the clearing of the land in Farndale by about 1230.

There was pastureland in Farndale by at least 1225.

With the

recovery of agriculture, manors started to invest in mills to grind grain.

These were a major investment, but were a means for a lord to gain an income

from their lands.

Even by 1280

there were folk such as William the

Smith of Farndale who specialised in supportive trades. By 1363, Johannis de

Farndale had moved to York

and was working as a saddler in an urban setting, and his family would stay

there for generations, his grandson

being a butcher.

Agricultural

land was sometimes connected by the King’s Highways, which fell under legal

protection and generally linked to the market towns. There were a few long

distance routes, often called great ways or magna vias. A magna via

through Huttons Ambo led to York. Routes across the high moors were sometimes

called riggways. There were a small number of

bridges generally on lower ground, for instance at Kirkham. More local routes

often formed a start of routes in the immediate neighbourhood, whose pattern

changed between summer and winter. There were few signs or markers, but

occasionally crosses would mark a junction, such as Whinny cross on Yearsley

moor.

Tolls may

have been taken, though locally they were not often recorded and might have not

been worth it for the lack of traffic. Gatelaw

was a road tax levied in Pickering Forest.

Early rural

industry was focused on corn milling. Some castles and monasteries had more

specialised industries and most of them had bakehouses and breweries. There is

some evidence of medieval pottery, for instance pottergates

of Pickering and Gilling.

Corn mills

inevitably belonged to the manor. A water corn mill was a substantial

investment, but provided a lord with a steady source of income. Occasionally

windmills were found on low flat lands. Village fulling mills were sited on

streams, including at Farndale.

The number

of village blacksmiths suggests the extraction of ironstone at some scale.

Barned arrow rents suggest than iron was readily available in Farndale.

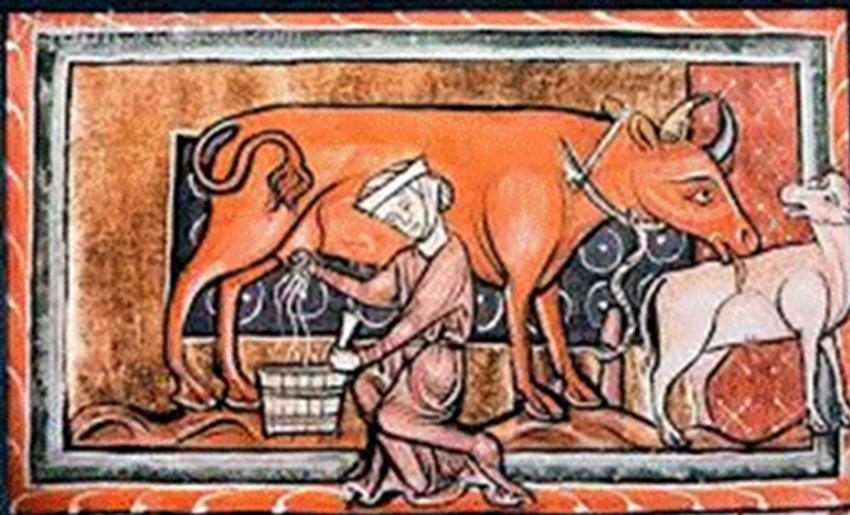

Villein

woman milking a cow, mid Thirteenth Century

The Commons

Act in 1236 was part of the

Statute of Merton, the first written law agreed by the Lords in Parliament,

during the reign of Henry III. It set principles of land law and allowed

manorial lords to enclose common land for their own use.

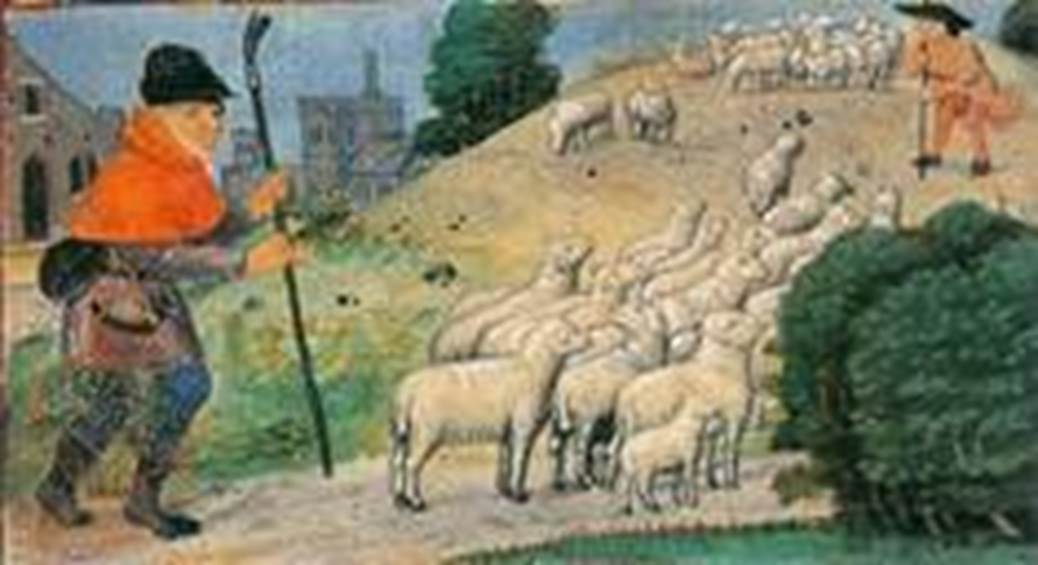

John

the shepherd of Farndale was a herdsman in Farndale by about 1270.

By 1276

there was perhaps 545 acres of cultivated land in Farndale. By

1282 there was perhaps 768 acres in cultivation in Farndale.

By this time

there were some 800,000 oxen and 400,000 horses in England, which enhanced the

power of labour some six or seven times.

Wool was the

most significant export, with some 12 million fleeces exported each year.

As the

population spread into less settled regions, with poorer soils needing more

labour, a collective open field system spread. Each vill

was divided into two or three huge open fields. One field was left fallow. The

fields were ploughed in a ridge and farrow pattern, with the undulations often

still visible today, as at Kilton and

around Kirkdale church.

Households would own strips of land in each field, but the use of the fields

was well controlled. This open field system reached its peak in the fourteenth

century.

Most people

lived in a village, worshipped in a parish and worked in a manor. A lord might

possess many manors, or one. A manor operated as a large collective.

Senior

villagers held offices, such as constable or church warden.

About two

thirds of manorial tenants were not free in 1200, but were villeins or serfs.

Villeins usually paid part of their rent in labour. Strictly, they could not

leave the manor without permission. They could be sold.

The common

law gradually extended to all free men and even unfree men had certain rights

and could even pass on their land to their heirs.

At a local

level, the Lord was the pinnacle of local society and the political, cultural

and economic focal point.

Norman

feudalism only lasted in a purer form for about a century and it was replaced

by a primitive system of land tenure. Over time this was increasingly paid for

by money rather than service. Villeins were replaced by husbandmen who paid

rents. The lord provided land, justice and protection. In return the lord

expected obedience and deference; support to profit from the land; and military

assistance when necessary.

By the 1300s

there were some 20,000 individuals and 1,000 institutions who made up the

landowners in the country.

In the

second half of the thirteenth century there was a disastrous fall in global

temperatures, which led to a succession of storms, frosts and droughts. The

Great Strom of 1289 ruined harvests across the country. Real wages fell by

about 20% between 1290 and 1350. Wars in Asia Minor from the 1250s and war with

France disrupted trade.

By

1301, there was a sizeable agricultural community in Farndale, with 39 names

associated with the place and the identification of farmed settlements which

can still be identified today.

The Thames

froze in 1309 to 1310. In 1315 to 1316, two years of continual rain ruined

harvests. A great famine across Europe lasted for 7 years. These were years of

perhaps the worst economic disaster that Britain has faced. Half a million

people died of hunger and disease. Water levels rose in the lowlands and the

banks at Rillington were raised in 1342 by the monks

of Byland Abbey. The tidal rivers of the Humber rose 4 feet above average in

1356.

In 1349 came

the Black Death. Indeed the plague

attacked the population four times in thirty years and became endemic for three

centuries. The reduced population eased the demand on arable crops, but the

market still sought mutton and beef, wool and hides. In sizeable estates, fields

could be allocated for rearing and fattening. Agriculture became more complex.

Many of the

folk living in a late medieval village would have had a one room house. The

villagers provided most of what they needed for themselves and their daily

routine was governed by the seasons.

Reconstruction

from the Ryedale Folk Museum

The family

lived at one end of the building and the animals, kept for milk, meat and wool,

at the other. The hearth, where the meals were cooked, was the centre of the

home. The smoke would escape through the thatch.

The cottage

was also used to store tools and those used for raking, hoeing, scything and

chopping varied little over centuries. Hay and grain, needed over winter, were

stored in the loft and salted meats hung from the roof beams.

The most

precious possessions were stored in wooden chests. All the furniture could be

easily moved to allow the room to be used for other purposes.

Economic

growth meant that peasant families could manage their small holdings and earn

some funds on the side, by spinning or brewing ale etc. This meant that they

could marry earlier and they started to buy furniture, clothes, utensils,

pottery etc and to eat puddings and pies and drink ale.

People of

this period tended to be taller than at the start of the nineteenth century.

There is no sign that girls were undervalued at this time.