Poaching in Pickering Forest

A study of the nature of poaching in

Pickering Forest

This section

relies on David Rivardís The

Poachers of Pickering Forest 1282 to 1338, a detailed study of poaching

in Pickering.

The

Blakey Moor Expedition

On 23 March

1334 Nicholas Meynell led an expedition out on Blakey Moor above Farndale, to poach for deer in

Pickering Forest. This suggests that many of the records of medieval poaching

at Pickering which involved folk from Farndale, may have been to offences

committed in the forests in and around Farndale, which might have been

administered as part of the larger forest.

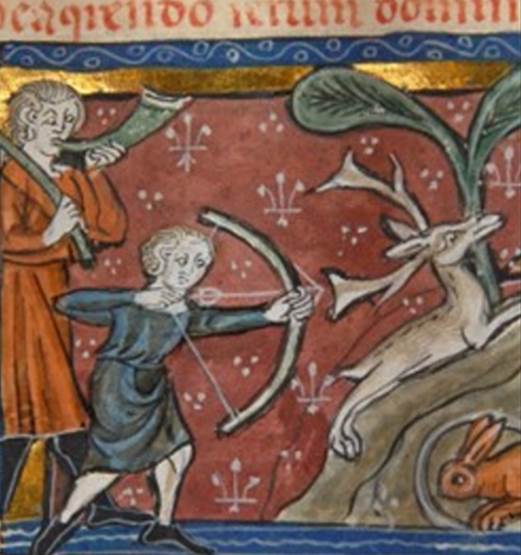

Meynell was a

nobleman with a band of at least forty men and boys, including tenants and

under tenants, clergymen and knights, and the young Peter de Mauley, Baron of

Mulgrave. They carried bows and arrows and led gazehounds, or

greyhounds, who would track their prey.

The party

slew forty two harts and hinds that day. They

brazenly left the decapitated heads of nine harts,

impaled on stakes on the moor.

Seven months

later, the noblemen of the hunting party appeared before the Justices of the

Forest, whilst the poorer ordinary folk were outlawed.

Categories

of Poachers

Poaching

activity cut across class lines. It was a lark for noble gentry, and an act of

desperation for those of ordinary rank. The elite ranks produced handbooks for

the ritual and practical conduct of hunts and lyrical and epic poetry was

composed to describe the chase. For the lower social orders the hunting of deer

bore more risk, a breach of the increasingly sophisticated forest law. Fear and

suspicion accompanied the expansion of regulation. The laws prevented the

control of game when crops were at risk, required the mutilation of dogs

prevent them from hunting within the forests, and forbad the carrying of a bow

within the forest. Hunting therefore became associated with freedom, feasting,

and rebellion against authority. By poaching, the locals around Pickering expressed

themselves in competition with the forest administration.

David Rivard

studied 509 cases from the eyre

records, identifying 399 individuals, 365 poachers and 34 receivers of venison,

between 1282 and the close of the eyre in 1338. He identified three subgroups

of poachers. The elite poachers included the peerage and higher gentry. The

middling poachers included the clergy, servants of clergymen, forest

officers, lesser gentry folk, artisans, tradesmen, urban poachers, and

receivers. His largest group were the lowly poachers, the peasantry.

Elite

poachers included Peter de Mauley, fourth baron of Mulgrave, who was with Lord

Meynell involved in the Blakey Moor raid. Peter had inherited his father's

lands in 1309, an estate that embraced at least six knights' fees, four capital

messuages, three parks, and the castle and orchard

of Mulgrave. A pardoned supporter of Thomas, earl of Lancaster, Peter seems to

have been a regular hunter. His expeditions seem to have been large, social

gatherings. Another episode recorded him in the company of many others

unknown taking two harts in Wheeldale Rigg.

Sir John Fauconberg was another knight with a taste for illegally

hunting in the royal forests. Having taken three deer in the forest of Pickering and the woodlands of Whitby in 1323, Sir John was arrested by Hugh

Dispenser junior, imprisoned, and fined the vast sum of £66 13s 4d. He appealed

to the king's mercy from prison and was released after paying a tenth of the

fine.

Knights

often hunted at the head of poaching parties in Pickering Forest. In 1334, Edmund Hastings,

who held four oxgangs in Roxby and the forestership

of Parnell de Kingthorpe, went out with members of

his household and hunted a hart on Midsummer Eve, perhaps to provide the

main course for a seasonal feat. He was caught and forced to present a letter

of pardon from Earl Thomas to secure his release.

Sir John

Percy and his brother Sir William, heirs of the Percy family of Kildale, a

cadet branch of the powerful Percys were also present in the expedition of Lord

Meynell and the Baron of Mulgrave, for which they were imprisoned and ransomed

for £2 27s. Sir Thomas of Bolton, lord of the manors of Hutton-upon-Derwent and

Hinderskelfe, went poaching with a large party of the

gentry and hounds and killed two hinds.

However

Rivardís review of the lay subsidy

records suggests that only a small fraction of the poachers had adequate wealth

to tax. Of the 365 poachers he studied, only forty two, comprising 11 percent,

paid taxes in the period he studied, so the majority of Pickering poachers were

probably too poor to pay the tax. The vast majority of the poachers he studied

possessed goods valued at £3 or less.

By 1300 the

Crown had set the minimum income necessary for knightly status, the distraint

of knighthood, at £40 of landed income. For most of the population a yearly

income of £10 seems to have been the benchmark of wealth. The small amount of

goods possessed by the Pickering poachers

suggests that all but the richest poachers remained not too distant from a very

modest standard of living.

The artisans

and tradesmen suggested a pattern of family poaching similar to that of the

elite gentry. William and Roger Carter, accompanied by Gascon militiamen from Scarborough Castle, hunted hares. William

Cooper of Scarborough and his

apprentice travelled several miles into the forest in 1307, taking a stag for

their friend William Russell, who provided the hounds for the hunt and hosted

the feast. Hugh the Barker, of Whitby,

hunted a deer in Ellerbeck and was outlawed. Adam the Spicer was indicted for

hunting in the company of Nicholas Hastings in 1305 and for the shooting of two

deer calves. Millers, smiths, and coopers were amongst the poachers included in

the Pickering records. †

Poacher-receivers

received the carcasses for resale, but also poached themselves.

Forest

officials, especially the lower-class foresters and woodwards,

had a reputation for corruption and often took to a little poaching themselves.

These included William Vescey, a justice of the

forest; William Latimer, who held the officer of verderer at the time of

an eyre; and even the Warden of the Forest, Ralph Hastings. Two

foresters-turned-poachers were engaged by the abbot of Rievaulx, and were branded confirmed

poachers, suggesting that they were regularly brought before the justices.

The frequency of this designation suggests that many officers profited from

exploiting their commoner neighbours and their masters at the same time. The

foresters John Gosnargh and Walter Smith were both

branded common poachers and accused of sending venison to John

Wintringham, a monk of Whitby. Besides

these cases of habitual offenders, there were other officers who took advantage

of their privileged position. Richard the Forester accompanied Sir John Fauconbergís party of 1323. Ingram the Forester found

himself charged for an incident in which he resorted to using an axe to slay a

young doe but succeeded only in maiming it, until his dog could track it to the

ditch where the deer was killed. These activities suggest an abuse of power in

Pickering Forest. Although forest officials enjoyed a salary, they also

probably benefited from extortion as well as their own hunting expeditions.

Of the 365

cases studied by Rivard, 80 percent or 293 of poachers fall into the more lowly

class, most of them leaving no record save their appearances in the eyre rolls.

†

Amongst

these were the garciones, or servant boys who

led the hounds in the hunts of the gentry. John Pauling, the lad of Peter

Acklam took part in the hunt of a deer on Yarnolfbeck

in 1322 and of another on Hutton Moor in 1323. Nicholas of Levisham,

lad of Geoffrey of Everley, poached with his master and helped slay three harts and three hinds in Thrush Fen on the Monday

before Whitsunday, presumably to provide food for his master's holiday table. The

garciones poachers were generally outlawed.

Their loyal service to a local lord did not save them from the full penalty of

the law.

Most of the

lowly poachers of Pickering were not folk whose names appeared in the lay

subsidies, and their poaching activities seem to have been of a seasonal

nature. Sixty one percent of these people never paid a fine to the eyre, but

were outlawed.

There was a

significant time lag, often more than thirty years, between eyre. So non appearance might simply have reflected disappearance

for various reasons including death. Many offenders might have simply evaded

the eyre for fear of the punishment they faced. Of the 143 poachers studied by

Rivard who paid, 61 percent paid fines of 1 mark or less, while a quarter paid

fines of 6s 6d or less. Fines were imposed by the eyre operated on an ability

to pay scale. The low level fines indicates that most Pickering poachers

possessed little wealth.

Edward

Miller in his study of northern peasant holdings concluded that 12 percent of

the population of Yorkshire might be classed as rich peasantry, possessing

holdings of over thirty acres. The majority of the lowly poachers in Rivardís

study fell below that standard. Non appearance in the

tax subsidies suggests that most were of very meagre wealth, and likely to have

been poverty stricken. Holding lands of comparative small size, much of which

may have been recently reclaimed from infertile moor and woodland in the

assarting boom of the thirteenth century, these poachers could easily have felt

compelled to supplement their meagre diets with the venison of Pickering.

Edward Miller felt that the thirteenth and fourteenth century forest dwellers

of Pickering were on a journey to the margin, so opportunities for

venison must have been too tempting to resist.

Drivers

of poaching activity

There was a

rise in poaching activity during periods of hardship and political instability.

The periods 1315 to 1317 and 1322 to 1323 were disastrous years of torrential

rain and crop failure, when the price of grain rose because of the great

scarcity of wheat and there was a general scarcity of food across the

countryside. Under such desperate conditions, a dramatic rise in the number of

individuals poaching for those years might be expected. Yet there was no such

increase and indeed, there are no recorded incidents for the year 1315, and

1316 and 1317 each saw only five cases per year. However the major crop of the

lands around Pickering was oats. Oats seem to have continued their normal

levels of production. Bolton Priory estates in the West Riding of Yorkshire

produced 80 per cent of their normal yield of oats in 1316 and cropped only

11.5 percent of rye and 12 percent of beans. A crisis that struck primarily at

the staple crops of wheat and barley will certainly have caused problems, but

may not have provided a strong enough incentive for poaching. Nevertheless

other constraints did produce notable increases in poaching. The high rates of

1311 and 1331 to 1332 coincided with the poor oats harvests recorded in the

estate records of the bishop of Winchester for those same years. So on analysis

there seems to have been a definite link between poaching and the periods when

the harvest threatened the livelihood of the farming folk.

|

Recorded

indictments for poaching |

Comments |

|

Year |

Recorded

indictments for poaching |

Comments |

|

Year |

Recorded

indictments for poaching |

Comments |

|

|

1282†† |

5 |

|

|

1314††††††††††††††††††††††††††† |

3 |

|

|

1333 |

13 |

|

|

1292 |

5 |

|

|

1316 |

5 |

Great

Famine and sheep and cattle epidemic (ďmurrainĒ) |

|

1334††††††††††††††††††††††† |

45†††††††††††††† |

Beginning

of eyre |

|

1293 |

24 |

|

|

1317 |

5 |

Great

Famine & murrain |

|

1336††††††††††††††††††††††† |

32††††††††††††† |

Scottish

campaign ended |

|

1294 |

14 |

|

|

1321 |

4 |

Famine |

|

1337††††††††††††††††††††††† |

3 |

|

|

1304 |

5 |

|

|

1322†††††††††††††††††††††† |

20††††††††††††††††† |

Famine and

political turbulance |

|

1338††††††††††††††††††††††† |

6 |

|

|

1305 |

41 |

|

|

1323†††††††††††††††††††††††† |

32 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

1306 |

13 |

|

|

1324†††††††††††††††††††††† |

12 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

1307 |

23 |

|

|

1325†††††††††††††††††††††† |

11 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

1308 |

6 |

|

|

1326†††††††††††††††††††††††††† |

3 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

1309 |

6 |

|

|

1328††††††††††††††††††††††† |

7 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

1311 |

35 |

Poor

harvest |

|

1329 |

20 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

1312††† |

17 |

|

|

1330 |

8 |

Scottish

campaign began |

|

|

|

|

|

1313 |

10 |

|

|

1331†††††††††††† †††††††††† |

15††††††††††††††† |

Poor

harvest |

|

|

|

|

(From David

Rivardís case studies)

The famine

year of 1321 to 1322 also witnessed a strong upswing in the number of cited

poachers. Although the cause of the agricultural difficulties that provoked the

famine are not known, bad weather, perhaps caused by drought instead of heavy

rains, and the devastating sheep murrain that struck England from 1315 to 1318

must have played a role.

It is likely

that the political turbulence of the time also contributed. In 1321 there were

only four reported poachers but in 1322, there were twenty. This increase might

be explained by the defeat in battle of the master of the forest, Earl Thomas

of Lancaster, at the

Battle of Boroughbridge, who was captured and executed by Edward II. In the

same year Edward was defeated and fled before the Scots at the Battle

of Byland. The death of the immediate overlord of the forest must have been

an irresistible invitation to poachers to exploit the unprotected deer of

Pickering. Indeed, a special commission was appointed by Edward II that year to

investigate the rise in forest crime. The defeat of the king, the nominal

master of the forest following the death of Thomas, must have increased the

temptation to take deer at the expense of an absent, impotent authority.

Political

unrest might also have been responsible for the relatively high rates of

poaching in the years 1331 to 1336 when Edward III actively pursued his

campaign against the Scots from his court at York.

This was a period of an increased demand for resources caused by political

unrest, and a high incidence of violence in Yorkshire. The disturbances brought

about by a resident army and the imminent threat of invasion might have

inspired an increase in the rate of poaching. Foraging soldiers and hungry

peasants alike would have sought out deer in unstable times, when the risk of

detection might seem lessened by the presence of more immediate external

threats enemies to occupy the attention of the forest authorities.

Repeated

Scottish raiding on the North Riding throughout the last years of Edward II and

the early reign of Edward III also probably contributed to high levels of

poaching. Constant raids carried off many chattels and destroyed property, so

much so that the crown in 1319 found no taxable property in 128 vills of the North Riding. Widespread devastation

must have had an impact on the high levels of poaching in the decade of the

1320s, as peasants and lords deprived of their property took to the forest to

find food.

The

seasonality of poaching offenses in Pickering Forest suggests that the poachers

did not simply follow the traditional hunting season during the "time of

the grease," the season for the elite stag hunt in which the deer were

fattest, which was from 24 June to September. Of 464 dateable instances of

poaching in Rivardís survey, only a third took place in the optimum season for

recreational hunting. The Spring months particularly March, when the first

break in the upland winter might have occurred, and May, when spring was in

full bloom tended to coincide with the final depletion of the winter larder,

when high grain prices and hunger might drive poachers to seek Pickering's

deer, and were common periods for poaching. Winter saw the least activity,

because the harsh northern and moorland weather impeded opportunities for

hunting. Poaching was a year round activity, but the pattern also reflected the

periods when ordinary folk might have been most driven to supplement their

diets.

Pursuing

game, often with anonymity, the majority of Pickering poachers from the lower

classes and must have sought game because they were driven to do so by their

poverty, and the removal of their ancestorís rights to hunt freely for food.

Uncertainty and poverty, during times of war, famine, and disease, and

resentment of the new forest laws, were powerful drivers. Ties of family,

friendship, patronage, and common need, together with a unified resentment of

forest law, bound groups of these poachers together.

This is the

context in which we meet the poachers of Pickering forest who came from

Farndale, many of whom were ancestors of the Farndale family.