The Smugglers of Old Saltburn

Stories of smugglers, led by my four

times great grandfather known as the King of the Smugglers, and the undoubted

involvement of our forebears

You could

begin with some sea shanties from the Saltburn Smugglers’.

|

Smugglers of Old Saltburn Podcast This

is a new experiment. Using Google’s Notebook LM, listen to an AI powered

podcast summarising this page. This should only be treated as an

introduction, and the AI generation sometimes gets the nuance a bit wrong.

However it does provide an introduction to the themes of this page, which are

dealt with in more depth below. |

|

Rudyard

Kipling’s vision. |

|

If you

wake at midnight, and hear a horse's feet, Don't

go drawing back the blind, or looking in the street; Them

that ask no questions isn't told a lie. Watch

the wall, my darling, while the Gentlemen go by! |

Five

and twenty ponies, Trotting

through the dark - Brandy

for the Parson, 'Baccy for the Clerk. Laces

for a lady; letters for a spy, Watch

the wall my darling while the Gentlemen go by! |

Running

round the woodlump if you chance to find Little

barrels, roped and tarred, all full of brandy-wine, Don't

you shout to come and look, nor use 'em for your

play. Put the

brishwood back again - and they'll be gone next day

! |

|

If you

see the stable-door setting open wide; If you

see a tired horse lying down inside; If your

mother mends a coat cut about and tore; If the

lining's wet and warm - don't you ask no more! |

If you

meet King George's men, dressed in blue and red, You be

careful what you say, and mindful what is said. If they

call you " pretty maid," and chuck you 'neath the chin, Don't

you tell where no one is, nor yet where no one's been! |

Knocks

and footsteps round the house - whistles after dark - You've no

call for running out till the house-dogs bark. Trusty's

here, and Pincher's here, and see how dumb they lie They

don't fret to follow when the Gentlemen go by! |

|

'If You

do as you've been told, 'likely there's a chance, You'll

be give a dainty doll, all the way from France, With a

cap of Valenciennes, and a velvet hood - A

present from the Gentlemen, along 'o being good! |

Five

and twenty ponies, Trotting

through the dark - Brandy

for the Parson, 'Baccy for the Clerk. Them

that asks no questions isn't told a lie - Watch

the wall my darling while the Gentlemen go by! |

|

The Smuggler’s

Song, Rudyard

Kipling, 1906

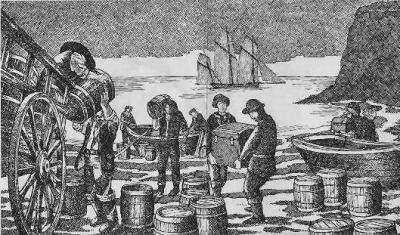

Smuggling

at Skinningrove and Cats Nab, Old Saltburn

As a result

of the government’s imposition of Customs and Excise duties on gin, brandy,

tea, tobacco and textiles, the smuggling trade grew more and more profitable

from about 1745 and the running of contraband from coastal inlets to local

villages continued for the next 70 years.

In 1763, a

30 ton sloop went aground at Saltburn

after the crew had gone ashore and left a boy on board the anchored vessel. It

was carrying contraband including over one thousand gallons of brandy and three

hundred gallons of gin. Two men from Skelton, Tommy Tiplady and

Bill Richardson, were to help unload it. The Customs and Excise tax on a gallon

of brandy was over 5 shillings, which was the equivalent of a week’s wages and

some thought the high profits to be made were worth the risk of the heavy

penalties if they were caught. Apart from the tax on wine and spirits, a duty

was levied on imported tobacco, tea, coffee, linen and even some household

items. The event was recorded in Ralph

Jackson’s diary in October 1763. Sunday the Second, a prodigious stormey day, much Rain, & Wind excessive high at N.E: I

went to Church in the forenoon, and ab 3 o’Clo. took

Jack wth me to Marsk, to meet Mr Wardell at Mr

Smith’s, but the former did not come, & the latter was upon the Land

attending 2 vessels that are drove on Shore, one, a small Sloop with Mercht’s Goods from Hull to Stockton, the other a Smugler Sloop, - I return’d

without alightinge.

Saltburn’s

geography contributed to its embrace of a smuggling tradition. The cliffs

provided an effective hiding place and the wooded coves provided cover for

offloading cargo and transporting it inlandBy the end

of the eighteenth century, the area became had become notorious. The Newcastle

Chronicle warned, on 20 June 1778 We are advised from Coatham, Redcar and

other places on the Yorkshire coast, that the smugglers there land in a most

flagrant manner.

With the

British navy engaged in wars with America and France, the Cornish and North

East coasts soon became flooded with contraband goods. Pursuits by customs

officers of local smugglers often involved the wider community, the community

generally supporting the smuggling trade. There is a story of an old woman

hiding a keg of spirits underneath her voluminous skirts whilst customs

officers performed a spot raid of her house. According to Reverend Grant’s

sympathetic account of the area’s smuggling antics, the ladies of nearby Marske

delighted in hoodwinking the officers. They sanded the streets at night with

leaves of tea, leading the officers to believe that the contraband had gone in

a certain direction and when the latter were busily engaged following the

supposed track, the men of Marske were equally busy in transferring the tea to

a totally opposite direction.

There is

another story of a horse, able to find her way home from the River Tees to

Saltburn without a rider, carrying smuggled tobacco on her back. One

enterprising mother who found herself victim of a surprise search, wrapped a

jar of spirit in her baby’s clothes, and walked past the guards with it cradled

in her arms.

Saltburn’s John Andrew

proved that smuggling was not a barrier to respectability and polite society.

Born in Scotland, Andrew moved to Saltburn and became landlord of the village’s

Ship Inn in 1780. Andrew’s Scottish family were wealthy and well connected. He

had attained the sublime degree of Master Mason in Scotland. In

partnership with a local brewer, Andrews co-ordinated the area’s smuggling

trade from his two properties, the Ship Inn and White House. He was christened King

of the Smugglers by his grand daughter. John

Andrew came close to being arrested on a number of occasions, the most famous

of which has entered local legend. Legend has it that John Andrews had a secret

cellar underneath one of his stables where he deliberately kept a vicious mare

who could be counted upon to kick and bite any strangers!

When the

Napoleonic Wars came to an end, the Saltburn smugglers came under increasing

pressure from customs officers. Forced to unload his latest cargo further

afield, John Andrew found himself at Blackhall, north of Hartlepool, when he was discovered by

customs officers. Legend has it that he galloped across the Tees, whose level

was apparently very low, to Coatham. He

then asked the Coatham coastguard for the time in order to give him an alibi.

The judge at his trial reasoned that he could not have travelled across the

River Tees in the time that had elapsed, and so could not have been at

Blackhall.

In Saltburn,

John Andrew was a respected member

of the community. In 1817 he was elected Master of the newly formed Cleveland

Hounds, demonstrating his high standing in the area. Andrew also managed to

combine being one of the area’s most prolific criminals with a prominent position

in the Corps of Cleveland Pioneer Industry. Ironically, this branch of the

local militia was occasionally called in to assist preventive officers in their

battle against smugglers.

William

Garbutt of Loftus Mill, John King, a brewer

of Kirkleatham, and John Andrew of the White House at Saltburn were joint owners of a cutter, the

Morgan Rattler, a very fast vessel. That vessel was used to run cargoes of

wine, gin, brandy, silk and Flemish lace to various places along the coast from

Runswick Bay to Marske. Some of the cargoes were hidden at Loftus Mill and

delivered around Loftus in the miller's

wagon. Other cargoes were carried away by pack-horse. The horses used were

Cleveland Bays, able to cover a hundred miles in a day, and so could get from

the mill at Loftus to the sign of the

Withered Tree in Ladhill Gill under cover of

darkness.

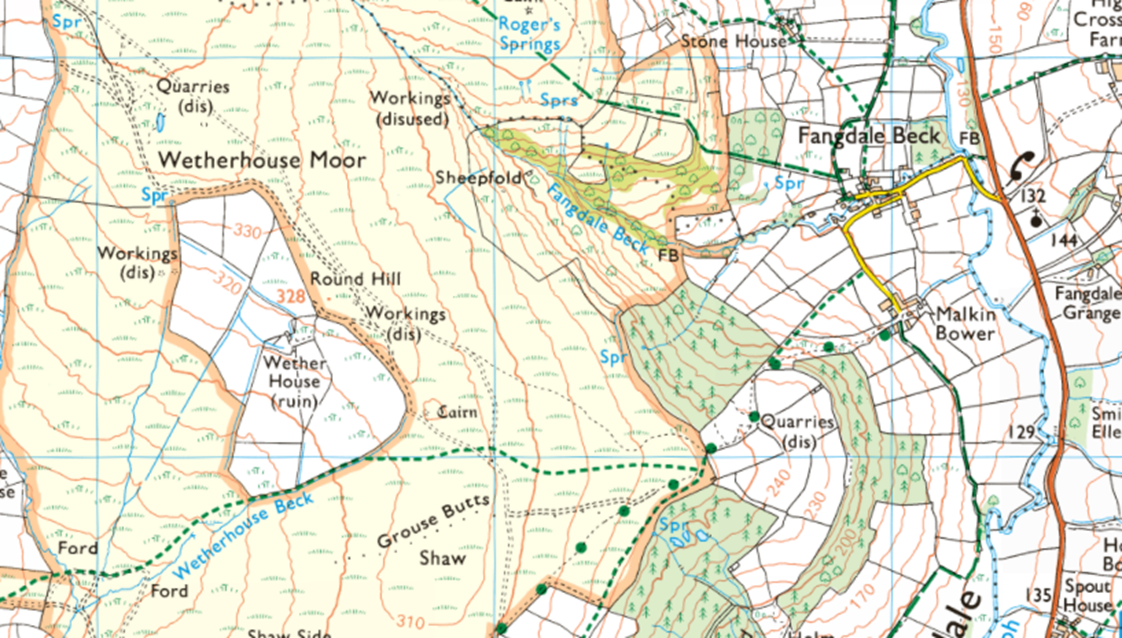

The Sign

of the Withered Tree was at the ruined farmstead now marked as Wether House, near Fangdale Beck

They

travelled from the mill to Gate House in Danby

Dale, a farm opposite the road up to Lumley House, where the farmer, John

Garbutt, hid some of the smuggled goods. Then they travelled on to Rosedale,

where Thomas Garbutt was landlord of the White Horse. Next they passed over the

moor to High Mill in Farndale,

back to the family’s original ancestral home, where the goods were hidden by

the miller, Leonard Hardwick. From Farndale they went along the moor causeway ,

across Bransdale Moor and Cockayne Ridge to Todd Intake and down by the Black

Intake to William Beck in Bilsdale.

From there

deliveries were made to Robert Medd at the Shoulder of Mutton Inn, Michael

Johnson at the Buck Inn at Chop Gate, and Thomas Medd at the Fox and Hounds at

Urra. The rest of the cargo was taken via William Ainsley at Spout House to the

Sign of the Withered Tree, at this time a drovers' inn, where John Garbutt was

the last landlord. It was here that the bolts of lace and silk were hidden and

later taken to York, to a seamstress who had a

shop in Stonegate. It is believed that the wedding trousseau of the bride of

the fifth Earl Fitzwilliam was made of some of the smuggled silk, but who

delivered it is not known.

Jack Sample,

who was landlord of the Feversham Arms in Helmsley in about 1936 he was born at

Saltburn where his father was a coastguard. His ancestors were Prentive Men who knew about these smuggling

activities.

John Andrew’s son, also called John

Andrew was later caught at Hornsea and spent two years in prison at York Castle.

In reality

local smuggling was very often bloody and violent. As pressure to suppress the

contraband trade increased, battles between the preventive officers and

smugglers became more frequent and violence ensued. In 1778, the Newcastle

Chronicle carried many reports of the increasingly brutal tactics employed by

the smugglers. It is the practise for fifteen or twenty to come on shore

armed with muskets, blunder busses etc,. threatening death and destruction to

anyone who dare offer to oppose them.

A menacing

letter was left by smugglers warning off the area’s custom officers. Dam

your ferry, and Parks blast your Ise you say that will Exchequer all Redcar but

if you do dam my Ise if we don’t smash your brains out you may as well take

what we give you as other Officers do and if you don’t we’ll sware that you take bribes.

A letter of

1775 from three customs officers working in the Markse

area describes the severe injuries they sustained from an altercation with a

group of smugglers. Accompanying the letter is a surgeon’s bill and a request

that the cost be met by Customs Office. We attempted to prevent the said

Goods being Run and having siesed part thereof, the

Crew belonging to the said Boat, consisting of seven unknown persons rescued

what we had seized and with handspikes and Bludgeons desperate Beat and Maimed

us.

Local legend

portrayed the smugglers as lovable rogues, who got one over on the

establishment. There was a reality of violence and threat as well though.

The

Smuggler’s Cove was a secluded bay, concealed by towering cliffs, which served

as the perfect hideout for smugglers. Under the cover of darkness, they would

dock their ships in the cove and unload their illicit goods, ranging from

contraband spirits to luxury items, avoiding the prying eyes of customs

officials. Local folklore is rife with tales of secret passageways and hidden

tunnels that facilitated the movement of smuggled goods, creating an air of

mystery and adventure.

The Saltburn

Gang was a well known band of smugglers, led by

charismatic figures, such as Black Jack Thompson and Gentleman George.

They formed a tight-knit network of individuals engaged in smuggling

operations. Their intimate knowledge of the coastline, the tides, and the

terrain allowed them to outmanoeuvre law enforcement effortlessly. The gang’s

reputation for evading capture and their ability to operate discreetly made

them legends in the annals of Saltburn’s history.

The

smugglers of Saltburn were engaged in a constant cat and mouse game with the

authorities. The customs officers, armed with the task of preventing illegal

trade, were determined to bring down the smuggling operations. Yet, the

smugglers proved to be a formidable adversary, employing various tactics to

outwit their pursuers. From utilizing hidden compartments in carriages and

secret compartments in houses to bribing officials and engaging in high-speed

chases along the coast, the smugglers demonstrated remarkable ingenuity and

resourcefulness.

What makes

the story of Saltburn’s smugglers even more intriguing is the involvement of

the local community. Many residents were sympathetic to the smugglers, as they

often relied on the trade for their livelihood. Smuggling offered employment

opportunities, boosted the local economy, and provided access to goods that

would otherwise be unaffordable. The smugglers enjoyed a level of protection

from the community, who would provide warnings of approaching authorities or

even help transport the contraband under the cover of darkness.

The

Farndales and the smuggling trade

John Andrew’s granddaughter, Elizabeth

Taylor later married Martin Farndale,

the author’s great great grandfather.

John Farndale

wrote that his grandfather, Johnny Farndale,

who was a Kiltonian, employed many men at

his alum house, and many a merry tale have I

heard him tell of smugglers and their daring adventures and hair breadth

escapes.

The lime

kilns and coal yard were kept by old Mr William Cooper, whose sloop, “The Two

Brothers”, was continually employed in the coasting trade. Behind the alum

house, Thomas Hutchinson, Esq., late of Brotton

House, made an easy carriage road from Saltburn to that place, which road will

always be a lasting monument to his memory.

In former

days, there were frequently seen lying before Old Saltburn three luggers at a time,

all laden with contraband goods, and the song of the crews used to be:- “If we

should to the Scottish coast hie, We’ll make Captain Ogleby,

the king’s cutter, fly”

The

government, however, being determined to put a stop to this nefarious traffic,

a party of coast guards, with their cullasses,

swords, spy glasses, and dark lanterns, were sent to the Blue House, at Old

Saltburn. This came like a thunderbolt upon the astonished Saltburnians.

They made, however, two more efforts to continue the trade – one proved

successful, the other not.

The last

lugger but one bound to Saltburn was chased by the King’s cutter, and running

aground at Marske, she was taken by the coast guard, and all the crew were made

prisoners, and put into the lock up. While the coast guard were busy enjoying

their prize, all the prisoners escaped except one, who was found in Hazlegrip, and whom the King’s officers sadly cut up. Lord

Dundas, of Marske Hall, threatened to bring them to justice if the man died.

The last luggar that appeared on the coast was successful in

delivering her cargo. Two of the crew, fierce lion-looking fellows, landed, and

they succeeded in capturing two of the coast guard, whom they marched to the

other wide of Cat Nab, where they stood guard over them till the vessel got

delivered. While these jolly smugglers had the two men in custody, they sent to

the lugger for a keg of real Geneva, and at the point of the sword they

compelled the poor fellows to drink of that which was not the King’s portion.

After releasing their prisoners, and then telling them to go home, the

smugglers returned to their vessel, setting sail, they left the beach with

light hearts and a fair breeze.

Since the

merry days alluded to the glory of Old Saltburn has departed – its smuggling

days have passed away – its gin vaults have disappeared – and the gay roysterers who were wont to make Cat Neb and the adjacent

rocks resound with laughter, now rest in peace beneath the green hillocks in

the retired grave yards of Brotton and Skelton.

… Of late

years many buildings of Old Saltburn have fallen beneath the ruthless hand of

Time, and all that remain now are two or three humble looking cottages, with a

respectable inn, possessing good accommodation, the fair hostess being a grand daughter of the well known

and worthy huntsman, Mr John Andrews, sen.,, one of

the most ardent admirers of the sports of the field in that fox hunting

locality. In old Mrs Johnson’s days this inn was noted for furnishing visitors

with what were termed “fat rascals” and tea, a delicious kind of cake stuffed

with currants, and which the present obliging hostess, Mrs Temple, who is an

adept in the culinary art, can make so as to satisfy the most fastidious palate.

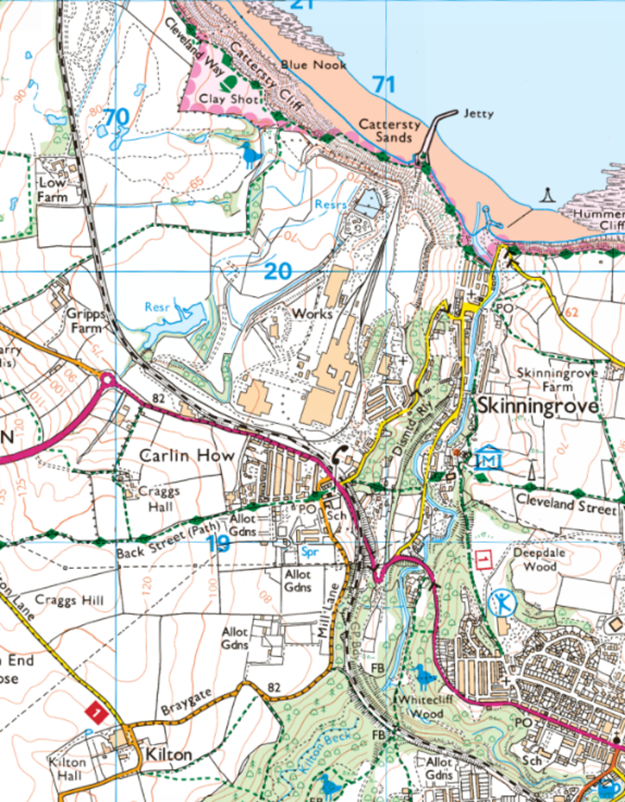

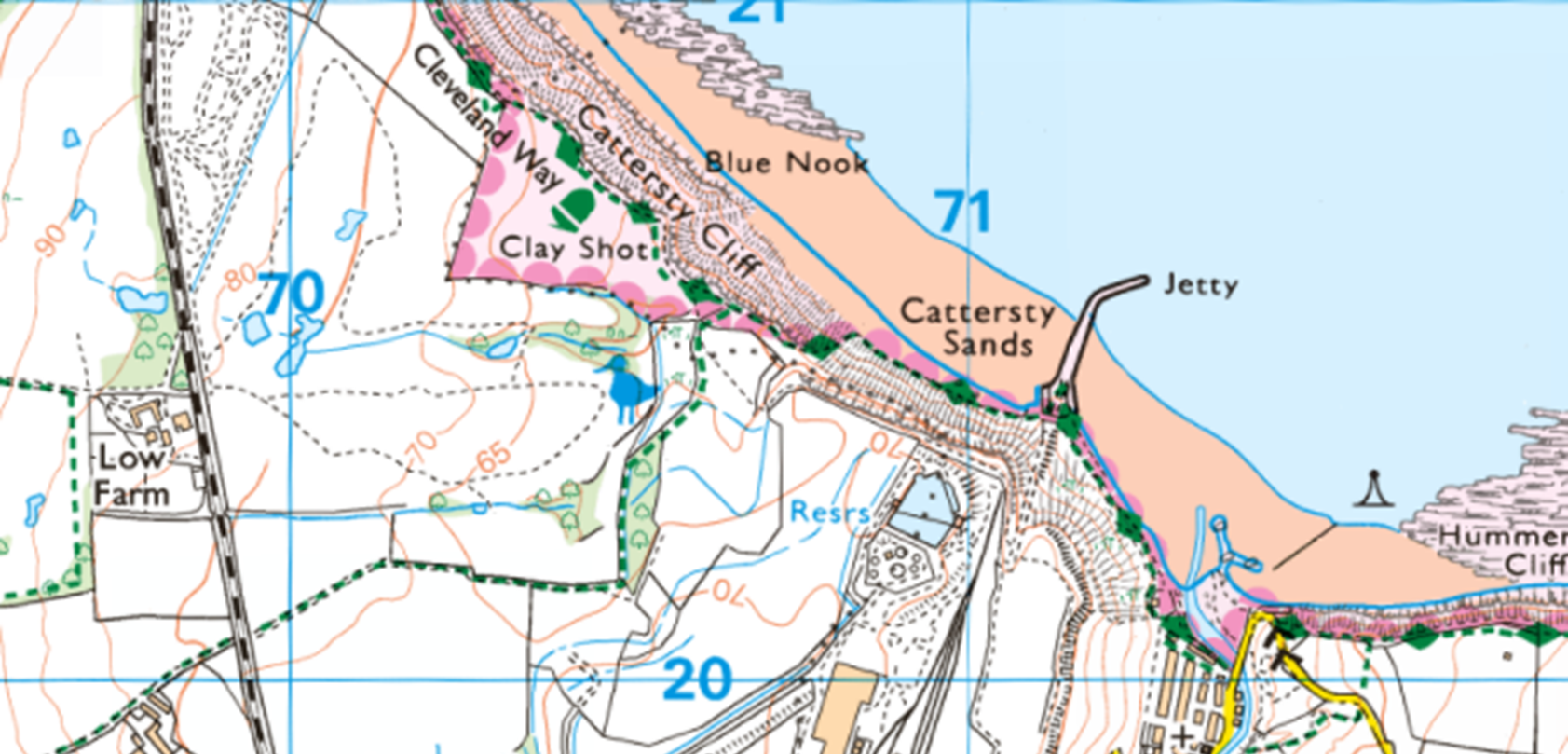

Then

passing down Cattersty Creak, where many a cargo

of smuggled goods have been delivered here, is a very choice place. The

last I remember in this place is that Tom Webster strangled himself by carrying

gin tubs round is neck. Once more I stand on Skinningrove duffy

sands, where I have seen it crowded with wood and corf rods for the North by the said Wm and John Farndale.

But what crowds of horses, men, and waggons, when the gin ship appeared in

view. Our friends had no dealings with those Samaritan gin runners, yet they

had great dealings at Skinningrove seaport, both in export and import, as well

as supplying the hall of F Easterby Esq., with corn,

wheat, oats, beans, butter, cheese, hams, potatoes &c, &c, and once, a

year at Christmas – they balanced

accounts, over a bottle of Hollands gin, and after eulogising each other, the

squire would rise and say, “Johnny, when you are gone, there will never be such

another Johnny Farndale”.

Cattersty

Cliffs and Cattersty Sands are along the shoreline

west of Skinningrove. The names Cattersty, Hummersea and Skinningrove are all Scandinavian in origin.

The cliffs to the south of the village are the highest on the east coast. It is

associated with the tale of the

Skinningrove Merman.

Among ponderous

blocks of freestone falling from the cliff, fearful to behold, (when a ship

founders here in high water, there is no way to escape) there are many fine

specimens of stone you may find, until you arrive at Cattersty

Creek, once famous for the delivery of Geneva ships – numbers have delivered

their cargoes here. The last I remember was when Tom Wesbter,

of Brotton, fell down dead while carrying a tub of Geneva up this creek. Next

is Skinningrove, second to none for the contraband trade, and here, Paul Jones,

the pirate, threatened to land, and the tale is of the seaman caught, confined,

but made his escape to sea. This tale is still extant. Forget not the Alum

House, return by the cliff, the beacon, by Huntcliff,

safe home, and this ramble for varied interest can scarcely be excelled.

Our

association with the smugglers of Cat Nab at Old Saltburn.

The

decline of Smuggling at Cat Nab and Skinningrove

The scale of

smuggling during the golden age of smuggling was a significant problem for the

Government. In 1784 the Prime Minister William Pitt the Younger, suggested that

of the 13 million pounds in weight of tea consumed in Britain, only 5.5 million

had been brought in legally. Teams of Government Preventive Officers patrolled

the coasts, aiming to prevent or catch the smugglers. But there were not enough

officers and the smugglers often avoided detection. Staff from the onshore

Customs Houses were supplemented by Customs Revenue Cruisers who watched the

coast from the sea and from 1698 riding officers on horseback joined in the

coastal patrols.

Although

many people enjoyed the illicit gains from smuggling, the reality was brutal.

Local people were fearful of violent reprisals on informers, Revenue officers

were murdered and corruption meant that captured smugglers were able to avoid

harsh punishments.

In 1809 the

Board of Customs introduced the Preventive Water Guard, a force which used

nimble small boats to patrol the coasts. By 1816 the Guard was strengthened

with 151 stations, organised into 31 districts. The chief officers were

experienced naval seamen or fishermen and armed with ammunition, stores and

oars for rowing. They were at sea as much as possible.

By about

1822, the threat of Napoleon was receding into history and 7,000 sailors were

redeployed as coast guards to fight the smuggling trade. The coastguards’

cottages, still at that time considered part of Skelton (Saltburn was just the

few buildings around the Ship Inn) were built to house a section of

coastguards.

or

The Ryedale

Historian, Volume 16, Page 10, The Smuggler’s Road

from Loftus to Bilsdale, J R Garbutt.

A book about

John Andrew called Watch

the Wall my Darling, 2009, has been written by Richard Swale.