Alum

Our family involvement in the

important alum trade.

The Textile

Fixing Agent

Alum has

been used since ancient times for many purposes including medicinal. It has

variously been used as cure for haemorrhages, nits and dandruff, and other

ailments. From the Middle Ages it began to be used to increase the suppleness

and durability of leather and in the textile industry as a mordant to make

vegetable dyes fast.

Until the

middle of the fifteenth century the supply of alum primarily came from Turkey.

There was a flourishing trade between Asia Minor and Italy. The Italians used

alum for their dyeing establishments. After the capture of Constantinople by

the Turks in 1453, they looked for alternatives to Muslim sources. John di

Castro, who had been a dyer of cloth in Constantinople and had watched the

manufacture of alum, discovered an alum rock at Tolfa, a commune of Rome and

part of the papal states, and an industry began there which still exists. There

was soon a papal monopoly in alum.

The economy

of England, prior to the Industrial Revolution, centred around wool and linen.

This was very much a legacy of the monasteries. They had established the

rearing of sheep, in very large numbers, from which to produce the wool, and

the cultivation of flax, from which to produce the linen. The elite classes of

Tudor England liked to wear bright, rich colours. The only dyes available at

that time were derived from plants and minerals. These were not colour fast

during washing. To fix these natural dyes to the natural fibres of the wool and

linen cloth, it was necessary to soak the cloth in a mordant before putting it

through the dye bath. Alum could be used as a mordant.

Until the

reign of Henry VIII, alum had been sourced from the Italian sources which

remained under the tight control of the Pope. When Henry VIII seized domestic

control of religion from the Pope, it became imperative to find a domestic source

of alum. After some fifty years of prospecting and experimenting, a viable

process evolved for manufacturing alum from a rock stratum that was

particularly abundant in north east Yorkshire.

The earliest

prospecting for alum, towards the end of Henry VIII’s reign, took place in

Ireland, around Wexford. During the reign of Elizabeth I, further prospecting continued on Lambay Island, off

the Irish east coast. In England, the earliest attempts to make alum were on

the Isle of Wight and in Hampshire.

Elizabeth I

encouraged the domestic mining of minerals in order to escape customs payments

to the Pope, and she invited to Britain certain foreign chymistes

and mineral masters. Among them was Cornelius Devoz,

to whom was granted the privilege of mining and digging in our realm of

England for allom and copperas.

The

Process

Alum a

colourless crystal, is a double sulphate of aluminium and one other element, usually

either potassium or ammonium. The manufacturing process was very slow. From

first quarrying the alum shale, to shipping the first cargo of alum crystal,

could take twelve months or more.

Alum was

extracted from quarried shales through a large scale and complicated process

which took months to complete. The process involved extracting then burning

huge piles of shale for nine months, before transferring it to leaching pits to

extract an aluminium sulphate liquor. This was sent along channels to the alum

works where human urine was added.

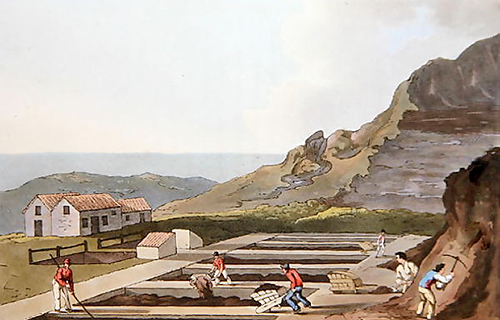

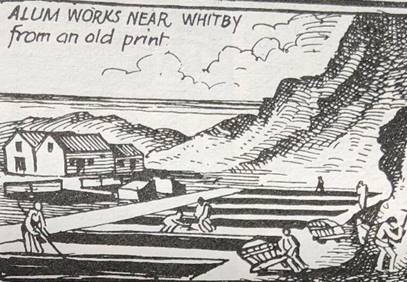

The first

part of the production process took place outdoors in a quarry. The quarry was

known as the Alum Works, which included all its associated fittings such as

bared rock, a burning place, steeping pits and storage cisterns.

Here men

would use pickaxes to excavate the rock from the quarry face, and then use

mauls to break the pieces down to a more usable size. Shovels would be used to

load the broken rock into wooden wheelbarrows, in which it was transported

along wooden planks, later iron plates, to the burning place. Here the rock

would be calcined in heaps known as clamps.

The clamps

were created by laying down a base of brushwood, about five metres across and a

metre high. Around and on top of this, the rock was added until the pile was two

metres high. At this point the brushwood was lit and the burning started. More

rock was added to the heap and around its sides, until the clamp was perhaps fifty

metres in diameter and twenty metres high. The clamp was then left to burn, in

a controlled manner. The skilled eye of the heap controller would gauge when

the burn had progressed to a suitable state.

At that

point, the burnt rock, now called mine by the alum workers, was removed

and placed in an empty steeping pit. Spring water and collected rainwater was

used to leach the soluble salts out of the mine, resulting a solution

called the liquor. The steeping process was a complicated affair, involving

pumping of the liquor from one pit to another in a carefully regulated

sequence. Eventually, the liquor arrived at the strength desired. It was then

pumped into a holding cistern, to await being sent to the alum house. When it

was required at the alum house, it would be transported there along wooden

troughs or stone conduits.

The Alum

house was the collection of buildings in which the liquor from the steeping

pits was processed through to the finished product, the alum crystals.

On arrival

at the alum house, the liquor was run into cisterns and left to stand

overnight. This allowed debris and detritus to fall to the bottom or float on

the surface. Either way, the clarified liquor could then be used in the alum

house. It would first be run into large evaporating pans set over open coal fired

furnaces. The pans were made of lead and were around three metres long, two

metres wide and one metre deep. They were set on iron plates which, in turn,

were set on iron bars, with the coal fires below them. The liquor was brought

to the boil and kept there until the desired strength was arrived at.

When it

arrived at the appropriate strength, the liquor was run off into settlers where

an alkali was added. The effect of the alkali was twofold. First, it brought

about reactions whereby unwanted chemicals were precipitated out. Second, it

reduced the acidity to the point at which the alum crystals could form. Once

the waste products had precipitated, the liquor was run off into coolers which

were large wooden casks with numerous wooden frames suspended in them. Here the

alum crystals had large numbers of surfaces on which they could form and grow.

Next the

mixture was transferred to small coolers to crystallize. The resulting crystals

of alum were then further boiled and condensed to get rid of impurities.

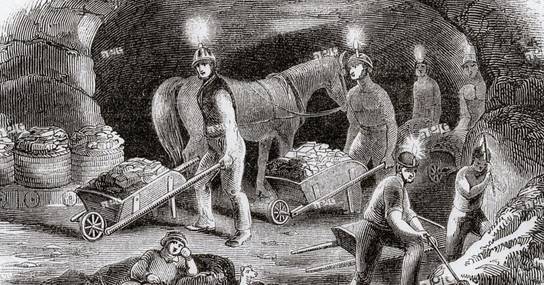

It was recorded

that the workers suffered terrible conditions. The heaps of shale gave off

poisonous sulphurous fumes. Their wages of 6d a day were often withheld or they were given in half rotten meat and corn.

The alum workers were described as poor snakes, tattered and naked, ready to

starve for want of food and clothes.

During the

final part of the process the crystals were scraped off the frames and the

sides of the coolers and washed with fresh spring water, to remove any remaining

surface impurities. The crystals were transferred to a roaching pan, smaller

than the evaporating pans but made of lead. Just enough hot water was then

added to dissolve the crystals. The liquor, after a final check on its

strength, was transferred to the roaching casks. Here it would cool for about

10 days. The outer cask would then be dismantled, revealing a column of solid

alum crystal. This would be left for another ten to fifteen days to allow the

liquor within the column to have a chance to crystalize further. At the end of

that period, the column would be broken into. The saleable alum was finally

bagged, ready for transport.

Alum in

Cleveland

Alum Shale

is found in beds immediately beneath the sandstone of the North York Moors.

The first

alum works in Cleveland started at Belman Bank in Guisborough Woods at the turn of the seventeenth

century by Sir Thomas Chaloner the Younger, who suspected the presence of alum

because the trees in the district were of a weak colour. He had visited alum

works in the Papal States where he observed that the rock being processed was similar to that under his Guisborough estate. He seems to

have induced Italians to leave the papal works at Tolfa and come to Yorkshire,

for which he was personally excommunicated. Thomas Chaloner of Guisborough is

reputed to have sold his own urine for one penny a firkin, which was about nine

gallons. There were many

odd names for imperial measures including pecks and gills and a firkin a fortnight

for urine.

Alum was

produced near Sandsend Ness five kilometres from Whitby in the reign of James

I.

In the Skelton area alum production

began from about 1603. The first profitable site in Yorkshire was opened in

1603 at Spring Bank, Slapewath, which was then part

of Skelton. This was the project of John Atherton, joint owner by marriage of a

third part of the Skelton Estate. Robert Bell wrote There was a house at

Spring Bank, near Mygrave (Margrove

Park) erected, but not completed for the manufacture of Alum. On the 15th

November 1603 an agreement was made between John Atherton and Katherine his

wife of the one part and Mr Leycolt of the other,

under which the Athertons were, at their own cost, to

complete the house and furnish it with the necessary appliances, namely, four

Furnaces and four pans of lead and iron for boiling Alum, Coolers of lead for

congealing , and convenient Cisterns of lead for keeping and saving the

"mothers" or strong liquors of alum and Copperas (green vitriol

or Iron Sulphate). They were also to set up a lead-finer with furnace, a balnium for trial of the earth for alum and copperas, pits,

pipes, vessels for draining the earth and making liquors and all other

necessary implements.

Once the

industry was established, imports were banned. Britain gradually became

self-sufficient. Whitby grew significantly

as a port as a result of the alum trade and by

importing coal from the Durham coalfield to process it. In 1610 James I made alum

production a monopoly of the Crown.

In 1616 alum

production began at Coombe Bank, Boosbeck and Selby

Hagg between Skelton and Brotton, located to the east of Hagg Farm and

would seem to have had three distinct periods of operation.

It is said

that ships anchored off Saltburn

to transport the finished product. They brought with them casks of urine, which

was mixed with the liquid that had been obtained from the calcined shale. We

don’t know where this process was carried out initially, but it was later done

in an Alum House sited near Cat Nab in Saltburn. The shale liquid ran from

Selby Hagg by gravity down a trough that followed the course of Millholme Beck.

From the

early seventeenth century until the 1860s it was extensively mined at Guisborough and along the East Cleveland

coast. The actual extraction of alum from shale was a long and expensive

process and it took an average of fifty tons of shale to produce one ton of

alum.

The early

works consistently struggled to make alum. There was little chemical knowledge

to turn to. Everything was done by trial and error. Large sums of money were

spent in trying to perfect the process. Something like £150,000 pounds or more

had been spent between 1550 and 1630. At least half a dozen prospectors were

bankrupted.

Nevertheless

after 1630, alum works sprang up all around the northern escarpment of the

North York Moors and along the coastal cliffs from Loftus to Ravenscar.

Competitor works started to emerge at Pleasington in

Lancashire, at Hurlet and Campsie in Scotland, and at

Neath in South Wales.

In the mid

eighteenth century the price of alum was particularly high and reached a peak

of £24 per ton in 1765. It therefore became commercially viable to mine in more

difficult locations. Several new mines were therefore opened including one east

of Ayton at Ayton Bank, just north of

Hunter’s Scar. Cockshaw Alum Works at Gribdale

quarried and processed the shale to produce alum crystals in the eighteenth

century.

At the peak

of alum production the industry required two hundred

tonnes of urine every year, equivalent to the produce of 1,000 people. The

demand was such that it was imported from London and Newcastle. Buckets were

left on street corners for collection and public toilets were built in Hull in order to supply the alum works. This unsavoury liquid was

left until the alum crystals settled out, ready to be removed. An intriguing

method was used to judge when the optimum amount of alum had been extracted

from the liquor by testing whether an egg could be floated in the solution.

The Alum

workings at Hummersea, Loftus

were worked well into the 19th Century.

By the mid

nineteenth century, an industrial process for making alum was patented by Peter

Spence. His works at Pendleton, Lancashire and Goole, Yorkshire were each

capable of producing more alum in one month than the entire Yorkshire alum

shale works ever produced in a year.

By 1871 the

last two alum works in northeast Yorkshire had ceased operation. They were driven

out of business by more efficient production processes and the arrival on the

market of synthetic dyes that did not require a mordant to make the colour

fast.

5 –

Belman Bank; 8 – Selby Hagg; 9 – Saltburn (the alum house for Selby Hagg); 10 –

Loftus; 11 – Boulby; 12 – Kettleness; 13 – Sandsend; 20 –

Eskdaleside

The

Farndales and the alum industry

John Farndale

wrote that Johnny

Farndale, who was a Kiltonian,

employed many men at his alum house, and

many a merry tale have I heard him tell of smugglers and their

daring adventures and hair breadth escapes.

He also

recalled in his works of

about 1870 Lofthouse, and their long famed alum

works, which has been the support of Lofthouse for ages gone, but now

discontinued. How well I remember my school days when we faced all weather

through Kilton Woods, and how I respected my masters – the Rev Wm Barrick, Mr

Wm King, the great navigator, and Captain Napper, steward to the works. The

popular Midsummer Lofthouse fair was the only fair we children were allowed to

attend.

or

Go

Straight to Chapter 17 – John Farndale and the Industrial Revolution

The

Alum Industry of North-East Yorkshire, Chris Twigg, 17 January 2018

A Brief

History of the Alum Industry in North Yorkshire 1600-1875, Roger L Pickles, The Cleveland

Industrial Archaeologist Issue no.2, 1975

Boulby Alum: The Works Diary

of George Dodds 1772-1788, K Quinn, Cleveland Industrial

Archaeology Society Research Report No 9, 2010

The Alum Farm, Major Robert Bell Turton Whitby,

Horne & Sons, 1938