Ironstone Mining

The engine of Cleveland’s Victorian

development was its mineral supply, particularly its ironstone. In the

nineteenth century there was an extensive network of mines throughout the area.

Ironstone

Between 206

and 150 million Years Before Present (“YBP”), in the Jurassic era, the

rocks forming the Cleveland Hills were deposited in a warm, shallow sea, which

was later the site of a river delta. Over geological time, these sediments were

compacted to form mudstones, shales, siltstones and sandstones. The Cleveland

Ironstone Formation formed in the Lower Jurassic (about 200 to 175 million YBP)

comprised hard beds of sideritic and chamositic

ironstone.

Ironstone includes

iron-bearing minerals with other elements, but the iron content is generally

low at about 30%. Two significant minerals are siderite or iron carbonate and bethierine or iron silicate. The minerals were formed

biochemically on the sea floor from iron either dissolved or suspended in

seawater. Higher parts of the Jurassic sequence include the Jet, alum shales and sometimes coal seams, all of

which had an economic value.

The economic

value of ironstone depended on the iron content; the thickness of the seam; the

presence of shale within the seam; and the amount of deleterous elements, especially sulphur.

The

Cleveland Orefield extends over 1,000 square kilometres. The main seam was up

to five metres think at Eston and then thinned southwards. The typical iron

content of Loftus was about 28%, which was significantly

less than the Eston mines. As mining proceeded it became necessary to separate the

shale as waste.

Unlocking

the potential

Ironstone mining

began in the Iron Age and mines at Malton and Pickering continued in operation from

Roman times.

There are

extensive heaps of slag around Rievaulx

Abbey, where water was diverted to help with the movement of the stone to

the monastery. The abbey and its ironworks were acquired by the Earl of Rutland

after the Dissolution of the Monasteries, who continued working the ironworks.

By 1545, four furnaces were smelting iron ore under the management of John

Blackett, the vicar of Scawton. The vaulted undercroft of the refectory was used to store the charcoal

used as fuel. A blast furnace was added in 1577 and a

forge was re-equipped between 1600 and 1612. Local supplies of timber for

charcoal were all but exhausted by the 1640s and the ironworks closed. There

was similar early ironworking in Bilsdale, Bransdale

and Rosedale. Many of these early workings appear to have concentrated on the

Dogger Seam.

There were

various attempts to mine ironstone in the early nineteenth century, focused

mainly on coastal outcrops. The Pecten seam was discovered at Grosmont during the construction of a cutting for the

Whitby and Pickering Railway. The newly formed Whitby Stone Company sent a

cargo of ironstone to the Birtley Iron Company in 1836, but it was rejected as

being of poor quality. After some experimentation, the two companies soon agreed

a sales contract.

The Mining

and Collieries Act 1842 prohibited all underground work for women and

girls, and for boys under 10.

On 7 August

1848, the first mine in Cleveland opened in Skinningrove. It was not until

August 1850 that Bolckow and Vaughan made a trial of

the main Cleveland seam by quarrying near Eston. Underground mining started

shortly afterwards, using pillar and

stall. Over half a million tons of ironstone was raised annually by the mid 1850s.

Industrial

Cleveland

The Tees

Valley became a powerhouse of the Industrial Revolution. At its peak, eighty three ironstone mines provided a source of iron to

make railways and bridges across the globe, including the Sydney Harbour Bridge.

Around 35

mines opened between Eston, Great Ayton

and Hinderwell on the coast. There was a small group of mines at Grosmont and others in Rosedale.

Railways

were extended to serve the mines, and new settlements including North Skelton, Boosbeck, Margrove Park, Lingdale and Carlin How, emerged which encouraged

labour for the mines from the predominantly rural area. Rows of terraced

cottages emerged in Skelton,

Brotton, Skinningrove, Liverton and Loftus.

After an

initial rush there followed a period of consolidation as iron companies

absorbed smaller ventures and workings were rationalised. Marginal mines

closed.

There was a

downturn during the depression of the 1870s.

A new

generation of iron works on Teesside from the 1880s used Bessemer

convertors to turn the iron into steel. By 1883 production of Cleveland

iron ore peaked at six and three-quarter million tons.

The quarter

century before the First World War saw many older mines close with further

consolidation of companies and some new sinkings.

Rock drills

and mechanised haulages were used to increase efficiency and trim costs.

Around

twenty mines closed in the inter-war years. Many of the old companies were

absorbed by Dorman, Long & Co. Ltd, which dominated the industry at the

start of World War II.

Only nine

mines, all in the area between Guisborough

and Brotton, survived the Second World War.

Efforts were made to make mining more efficient. Diesel haulage was introduced

below ground. However the mines could not compete with

imported ore or the opencast mining around Scunthorpe and Corby.

North

Skelton Mine was the last to close in January 1964.

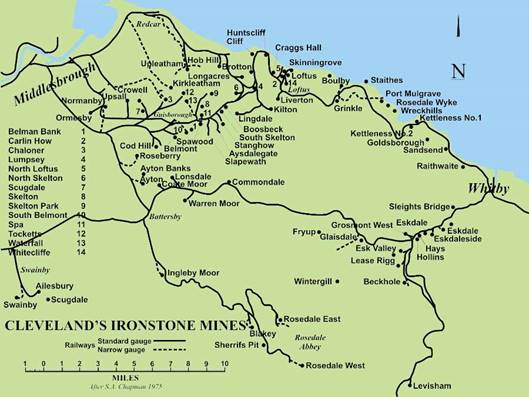

Cleveland

Ironstone Mines

There is a list of the Cleveland Ironstone Mines

and the Land of Iron website includes an interactive map.

Kilton

mine

The Kilton mines were sited to the south of

Kilton Thorpe and were opened in 1871. A large spoil tip still dominates the

skyline. Both Kilton and Lumpsey mines were served by

railways and the abandoned embankments and cuttings of the railways can still

be seen. The mines finally closed in 1963.

The

establishment of an ironstone mine at Lumpsey in the

late nineteenth century led to the destruction of the farm and no buildings

survive. The Lumpsey mine was opened in 1881, after

the shafts were first sunk in 1880. The ironstone companies had followed the

veins south and east from the Eston hills. The mine closed in 1954 but a number of the mine buildings still survive.

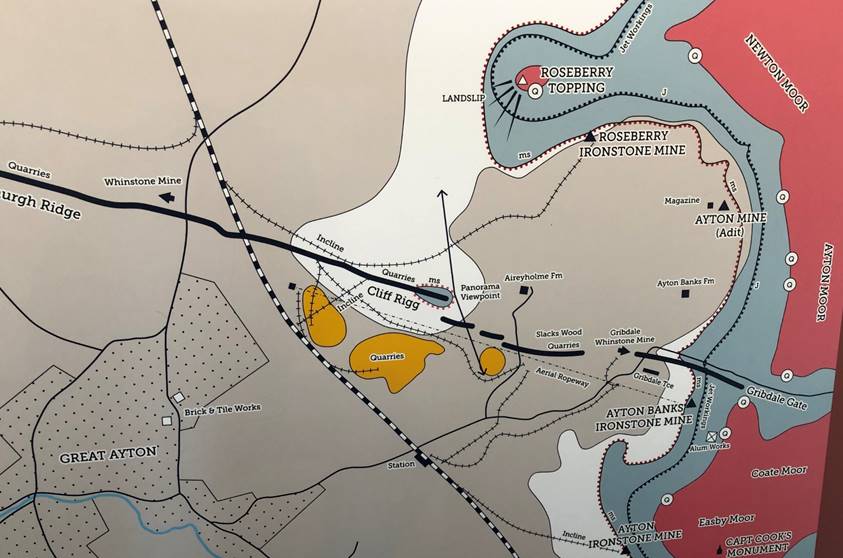

Three mines

operated around Great Ayton in the

first thirty years of the twentieth century – Rosebury, Gribdale

or Ayton Banks and Ayton Mine. Ayton Banks was a small concession operated from

1910 to 1921 by Tees Furnace Company. The mine worked the Peckten

seam of ironstone, which was named after the type of fossil found in the ore.

The

ironstone was mined by drifts or adits in

Ayton, almost exclusively from the main seam, which was the last of the beds to

be laid down. They used the pillar and

stall method of working. The Ayton mine workings were extensive, stretching

as far as a second entrance north of Ayton Banks Farm. The ore from the Roseberry

and Ayton mines was taken by tramway to the main railway line. Ayton Banks

ironstone was sent by aerial ropeway to the railhead. The site was not

accessible even for a narrow gauge railway, so an

overhead cable way was constructed, carried on metal pillars supported by

concrete bases, some of which can still be seen.

Ironstone

Mining at Great Ayton

or

Go Straight to Chapter 18 – The

Ironstone Miners