Atlantic Crossings in the early

twentieth century

Alfred

Farndale in the Atlantic on RMS Carmenia, 1928

The story of five brothers and two

sisters who crossed the Atlantic in the age of Titanic to emigrate to Canada

We saw a

great iceberg this morning. It was a great sight. This is a great rock of ice.

So you must know we were passing through a cold front. This is a big vessel

about two hundred yards long I should think. Every body

seem quite happy.

Martin Farndale in a letter dated 21 June 1905

You might

enjoy this some music

and a scene setter.

Martin

Farndale, June 1905

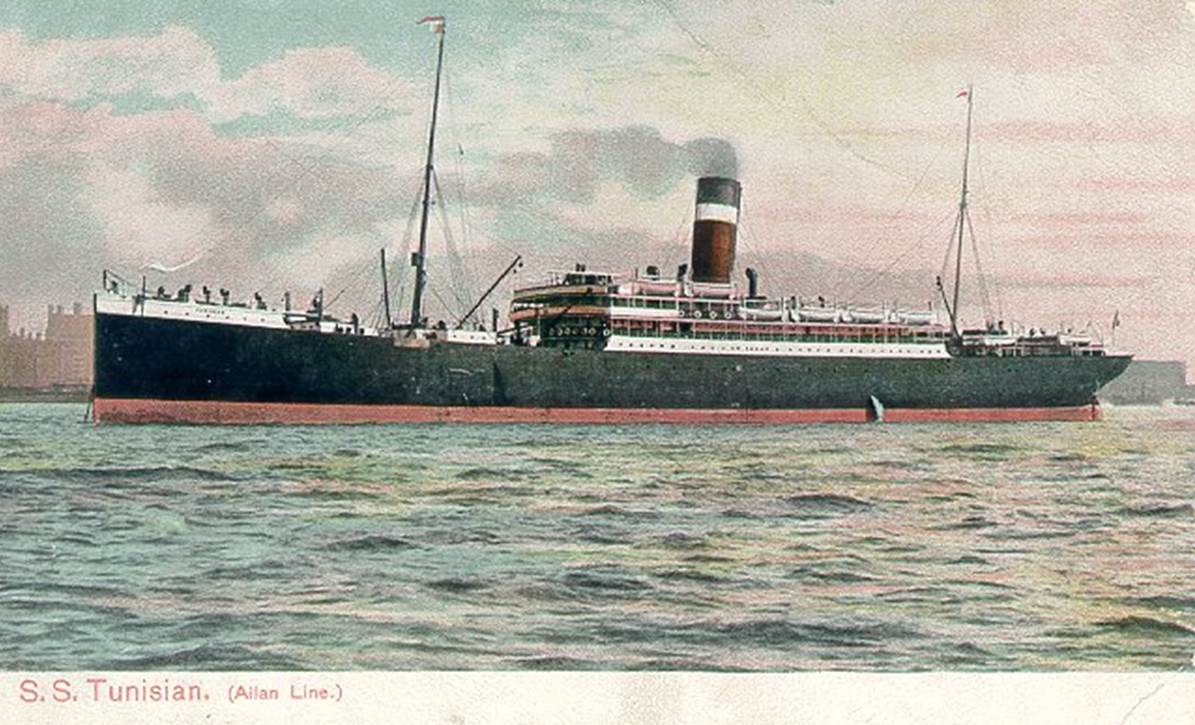

Martin Farndale was the first of the

Tidkinhow family to emigrate to Canada. He homesteaded on the Trochu land in Alberta and raised cattle. He

left home without telling his parents, and embarked on 15 June 1905 from

Liverpool on the SS Tunisian.

![]()

From the

passenger list for SS Tunisian 1905

Launched in

1900, the Allan Line's SS Tunisian was built by Alex Stephen & Son

of Glasgow. She took her maiden voyage on 5 April 1900, from Liverpool to

Halifax and Portland, Maine. A month later, she made her first trip to Québec

and Montréal. The Tunisian boasted refrigeration, good heating and ventilation.

It also had hot and cold, fresh and salt water on tap and four-birth emigrant

cabins with spring mattresses. In 1912, five days before the RMS Titanic

sank, the SS Tunisian reported heavy ice in the area that was to become

the site of the disaster. The Tunisian was travelling eastbound at this

time from St. John to Liverpool.

As he headed

into the Atlantic, he wrote a letter home to his sister, Lynn.

June 16th

1905

Friday

morning

Dear

Sister

Just a

few more lines. I left Liverpool on Thursday night for Canada on SS Tunisian. I

have had a good night's sleep. I have booked second class on board and is very

comfortable. We are passing by the north of Ireland this [ ]. The ship makes a

call here to take on more passengers. This letter will be sent on from here. I

shall not be able to post any more letters till I land at yond side. I am

enjoying the trip well so far. I hope mother will not fret if she get to know

before I write. I will send a letter to her as soon as we land. I am going to

do best . I am going a long way up the country. I am to Calgary in Alberta. It

is chiefly cattle farming there. There is several more young men on ship that

are going out from there can catch. But I have not meet any lady that is my way

yet. You must try and cheer mother up. There is nothing for her to trouble

about. I am as safe here as riding on the railways in England. I shall be about

other 7 days on the water. I will send a few letters off before I start my land

journey. I have not time write more. I want to up on deck. We are just about to

land at Londonderry I believe.

I must

leave hoping you are all well.

M

Farndale

A week

later, as Newfoundland was sited, he wrote another letter.

Letter

cannot be posted for England till we land so you will know if you get this that

I landed all right.

Wednesday

June 21st 1905

Dear

Sister

I shall

soon get my sea trip over now. Land was sighted today Newfoundland I believe. Every body is beginning to lighten up now. But it will be

Saturday morning before we land at Montreal.

I have

enjoyed voyage up to now. I had one day sea sick. It was awful. I don't want

that any more. We have had few very cold days. It is always cold in this part

of the Ocean. We saw a great iceberg this morning. It was a great sight. This

is a great rock of ice. So you must know we were passing through a cold front.

This is a big vessel about two hundred yards long I should think. Every body seem quite happy. There is a smoke room and a

music room. And the best of everything to eat. Third class seems to be rough

quarters. But they are in another part of the ship. There will be about eight

hundred passengers on board all together. Some men pulling long faces when the

vessel left Liverpool. I never thought anything about it. But I was like the

rest. I watched England till it disappeared out of sight. I hope mother will

not trouble about me. I will be all right. I thought it was my best thing to

do. I had nothing to start in business with in England. I shall be able to get

about £50 per year and board with the farmers out here. If I can stand the

climate. And I can settle. I shall be able to start farming for myself in about

two years.

Thursday

All

letters are to be posted tonight on board so that they will get away as soon as

we land. They don't [ ] to a few hours when they land. So all has to be ready.

First and

Second class are having a Grand On Board tonight. We shall be quite lively.

I now

finish. Hoping you are all well. And remain your affectionate Bro.

M

Farndale

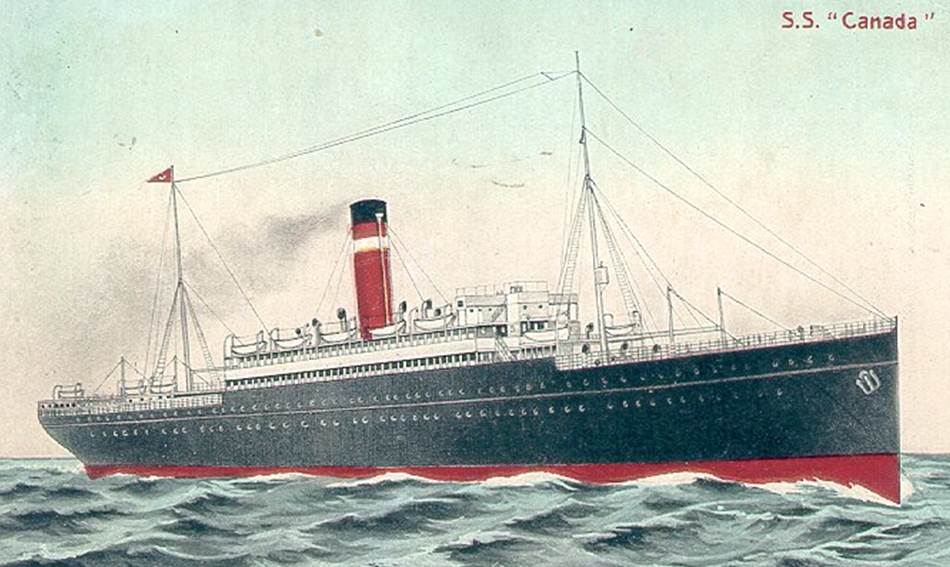

Jim

Farndale and George Farndale, March 1911

On 31 March 1911,

almost exactly a year before the RMS Titanic sank in a similar part of

the Atlantic Ocean, James

(“Jim”) Farndale sailed to Canada on the SS Canada of the same White

Start Line as Titanic. Jim departed

Liverpool and arrived Halifax, Nova Scotia on 10 April 1911.He travelled with

his brother, George

Farndale, who emigrated with him. There is a transcript of Jim’s diary

recording his emigration to Canada.

SS Canada

was one of

Dominion's original contributions to the White Star-Dominion Line. Built by

Harland & Wolff, Belfast, she was launched in 1896 and SS Canada

departed on her maiden voyage on 1 October 1896 from Liverpool with a stop at

Quebec before arriving in Montreal. She was used as a troopship during the Boer

War from November 1899 to Autumn 1902. In April 1912, SS Canada's

captain had claimed he was in the same ice field as the Titanic, ignored

wireless warnings and maintained her full speed. She resumed troop service

after the outbreak of World War I from 1914 to 1918.

Jim recorded

his voyage.

Friday

31 March 1911

I left

home on March 31. It will be remembered,

how we hurried to station and were just in time, also that George had gone the

night before, and was to meet me at Darlington.

It was on the afternoon of this day, I was on the Guisborough and met two ladies, one of

them looked very hard at me, and caused me to wonder why she did so. When my friends pushed me into train with my

luggage. I know nothing of who was inside the compartment, but on looking round

I saw the young lady whom I had seen on my way to station, but the rather

curious thing about it, was, she had spent six years as a nurse in Canada. (She is a nurse at Middlesborough) and had

been to Webster’s seeing their sick bay.

She told me they had been talking about me in the afternoon, and she

thought I must be the person. She knew

all about Canada and was quite interesting to talk to. When we got to Middlesbrough I felt quite sorry for I’d

been learning so much.

I was met

by my friend, Harry Watson, at Middlesbrough,

who had come from South Shields to see me off and stayed with him till the last

night to Darlington, so you see how my

evening was spent. I never had a chance

of feeling lonely.

Beckwith

(a young fellow going out on the same boat) whom I had previously met at Redcar

passed through Middlesbrough and was

going to spend the evening in Darlington

so we agreed to meet there later.

It is

rather curious how things happen, Watson whom I have referred to had known

Beckwith before he went to America the first time, and Beckwith knew the young

lady, also whom I’ve referred to, but none of them knew that I knew any one of

them. Again, another coincidence.

I got

into the train and parted from my friends at Middlesbrough and took my seat in the

compartment, when a lady sprang up and challenged me. It was a family from Bolton some of you may

remember how I heard of them going on same boat and called to see them at

Bolton, but only saw the lady, although I did not at first recognise her. Well,

now if I’ve made it plain it would almost appear as though this had all been

arranged, but it all just happened.

On

reaching Darlington I was met by George, and later

towards train time Beckwith strolled up.

We now learned that there was an excursion to Liverpool, which was to

leave an hour later than we intended going, and arrived two hours earlier, but

as we had luggage some of us were bound to travel with it; George took the

exit: leaving Beckwith and I to follow and he saved about 7/6. Our train was so crowded that they allowed us

to go in a 1st class compartment. We had a good time and were very comfortable

till we reached a place call Northampton, where we had to change and wait an

hour and about 3am we had a quick stroll through this place, which was fast

asleep. We laughed as we thought how

foolish we were. Next train we were not

so fortunate, but we managed to keep everybody out of our compartment so as to

be able to get a little rest for after having had a long two days running

about, we were sorely in need of it. We

thought, and were told, we had no more changes till we reached Liverpool, we

had taken off our boots, put on slippers and were having a little rest, when

the “fools” told us to change, so we had to rush up and pack.

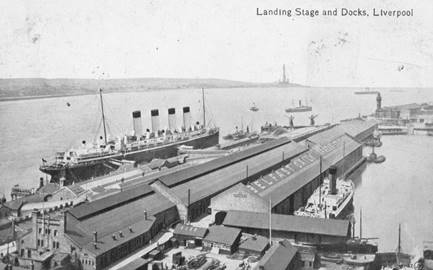

It was

about 8am when we reached Liverpool and were filthy somewhat like sweeps and

very tired. George who had been there a

good while, met us. Our first step was

to look after luggage. All we had to do

was to check them and give our names.

The ship company: officials are there to meet train so it is quite

simple. We went on and got to business,

had breakfast, and washed which was most necessary. We strolled round town, doing our little

business, got tickets made all alike, money changed, and made a few purchases

etc.

I got

some cards to send off, but the others wouldn’t wait, so had to write them in

the street when I had time.

We went

down to Dock about twelve o’clock, but the boat was not in and it was about

2.30pm when she steamed in. The place

was packed with people and was very difficult moving about.

However

they were soon ready for us to go on. We

just walk past the Doctor bare headed and he looked savagely at us and we

passed right on. We went ahead to find

our berths, which was a simple matter.

As our hand luggage was very heavy we got the Co to take it along with

the others, so had been taken on board early.

They sort it all out and take the wanted baggage to the berths for us,

but it is some hours before some of it gets there and we wanted certain things

as soon as we landed on board and it was with great difficulty that we secured

if from the others. They would not allow

us to pass with it.

Our next

move was to book seats at table, of course the seat you book first you keep all

the voyage through and we had up our minds that we would book first sitting if

possible, the reason why is; that it gets very late before second sitting and

one has to walk about passing time away in the morning, which makes one feel

sick. They begin booking seats straight

away in the saloon and give us our numbers.

Another difficulty arose; I went to book seats, and took the three

tickets with me, but as Beckwith was not on same deck as George and I, he

could not sit at same table, and he very much wanted to, but after a lot of

persuasion I succeeded in getting us all seated together.

I found

out there was time to write some letters (the pilot takes off mail about an

hour after sailing). I was busy with my

letters when she began to move. I

hurried out to see the scene, people were shouting from both sides and clouds

of handkerchiefs and hats were waived as far as we could see but we were soon

out of sight of it all and away out at sea.

People

were allowed on board to see off friends until time of sailing, when they are

ordered off, but some had been left on and had to be put off at sea on another

boat.

The mail

had come on board and was spread out on saloon table for us to sort for

ourselves. There were lots of letters

and telegrams. We sailed into a very

smooth sea and the night was just perfect, we soon passed away from land.

Saturday

3 April 1911

We did

not land at Ireland, but sighted and passed it about 8pm on Saturday

night. This was the last we saw of

Britain. We dined at 6pm. The boat is gently rolling everybody seems

tired, especially ourselves so went to bed in decent time.

Sunday

2 April 1911

Very fine

morning, and everybody seems in good spirits, there is, of course, no sickness

as yet, but there are some pale faces and judging from myself a few giddy

heads. At breakfast:- the tables all

filled up, the sun is shining very brightly and is so warm and many people are

sitting and lying in the sun.

Personally

I do not take much breakfast but soon strolled out into the fresh air and left

the others behind, they chaff me a little; of course they are old hands at this

business. The food is really very good, and there is everything necessary. This had been a truly glorious day, sea very

smooth.

About

10.30am we went to service in the largest saloon, the Chaplain is a fine young

fellow, he’s a pastor going to the States and is acting as Chaplain, he gave a

very nice address and the serviced passed off well and was short.

We can

hire deck chairs at 3/6 each, we get tickets and put our names on, they are

very comfortable and lots of people sit on deck all day, some bring their own

chairs, but they must be a lot of trouble.

This

afternoon we amused ourselves taking some snapshots, as it was so fine.

There is

a library, which is a very comfortable room; we can get books at a certain time

each day, and ours to pay a trifle for.

There is also plenty of writing material and good accommodation for

writing.

There is

a smoke room and a bar, with attendants, who seem to be pretty busy most of the

time. Amongst the men, there is a lot of

gambling, of course everyone is trying to do some thing

to pass away time if its only sleeping.

In each saloon there is a piano and lots of people to play, having

brought music with them for the purpose.

We

breakfast 7.30, second sitting at 8.30.

Lunch at 12 and dine at six. They

bring round something they pretend is leaf tea (serving ladies first) also tea

and biscuits in the afternoon. There is

plenty of fruit and if anyone is sick they will bring us anything we need

either to bed or on deck. So there’s no

fear of starving.

Sunday

has passed off very well and in splendid weather. People seem slow to make friends at the

beginning of the journey.

Any

announcements the officials wish to make are placarded

up in saloon entrance.

The

collection I have just noticed at service is 30/- and I think it goes to

Seamen’s charities.

We

noticed on board a lot of women, wearing a blue bow and we wondered why they

did so, we have since found out, they are being sent out by the B.U.P.A and are

in the charge of a Matron. I understand

they are shipping some out every month.

A lot of them are going right west to the coast and some to

Calgary. There is forty of this party,

quite a squadron. They all sit together

at table, three tables full of them.

There are a lot of women on this boat.

I’ve heard lots of people say they never saw so many on a boat. I should say more than half second class are

women.

Monday

3 April 1911

Very fine

morning, but sea just a little choppy and not so warm, boat rolling a

little. There is not much signs of

sickness although some are looking a little pale and a few are absent at table.

A big

steamer passed us today going same way, it was out of sight in a few

hours. Anything of this kind draws a

crowd everybody is interested at any sign of life. This was a very fast boat; it must have been

a Cunard liner. It was rather annoying

to be left behind so quickly, but our boat is not travelling so fast about

fourteen miles an hour.

I had a

little talk with the pastor, he said he was afraid he would be sick on Sunday

whilst he was performing his duties but he was quite all right today. His wife is on board and they are both busy

writing letters of introduction for people, when they reach their destinations.

Today we

received a wireless message from England but only short, it was put up for us

to see.

I was

talking to a nurse who has been all her life in Canada (Toronto) and has been

over to England and Ireland for six months.

I asked her about the winters in Canada.

She said it was the only thing she had missed during her holiday. She thinks the winters are splendid in

Canada.

I was

sitting in the library near some ladies, writing today, when one of them turned

round and asked me if I was an author, I, of course said no, but I may as well

have said yes. She said I was making

such copious notes she was sure I was writing a book (“of course ladies want to

know everything”).

I have

met several young men who are going to Calgary.

One gentleman I met, who is travelling round the world, with a party

they are going to Vancouver then east to Japan and back through Europe. He told me he was going to try and speculate

a bit in Vancouver and was quite interested in land.

There are

a lot of nice people on board, to look at the whole crew one would wonder what

they were going for, they are more like a pleasure seeking party, than anything

else. There is a lot of Clerks etc. and

many of them say they are going on the land.

I have met several surveyors and engineers.

Tuesday

3 April 1911

This

morning the sea is rather rough and there is a strong wind facing us and the

spray, for the first time, is blowing up on deck, from the waves, it is also a

little colder and the boat is rolling more than ever today. There is a little sickness this morning.

Later in

the day:

The

weather has become quite changed. The wind having risen and raining a

little. We are now being “Rocked in the

cradles of the Deep”. Most of us are

feeling it a little now. I myself am

feeling very bad, and cannot eat much, it is not a nice feeling, but it is

something new and all interesting. There

are lots of very interesting people on board, and as time goes on one makes

lots of friends.

Wednesday

4 April 1911

This is what

happened on Wednesday:

I have

missed a day out, which was very rough all day; towards evening the wind rose

and the sea at bedtime was very heavy and we thought we were in for a rough

night. I’ve not been able to eat at all

today; there has been a lot of sickness.

We passed

some sailing vessels. I don’t know how they live at all; they were tossing just

like corks on the boiling sea. We soon

left them. There was a lecture on Esporantos, but I was feeling too ill to do down to hear

it, and one feels best in fresh air on deck.

There are some gifted singers on board.

Some professionals. There is

music and singing every night.

Esperanto is the world's

most widely spoken constructed international auxiliary language. Created by the

Warsaw based ophthalmologist L. L. Zamenhof in 1887, it was intended to be a

universal second language for international communication, or the international

language, la Linguo Internacia.

Zamenhof first described the language in Dr.

Esperanto's International Language, Unua Libro,

which he published under the pseudonym Doktoro

Esperanto. Early adopters of the language liked the name Esperanto and soon

used it to describe his language. The word esperanto

translates into English as one who hopes.

Thursday

5 April 1911

Has

brought a great change over us all after a terrible rocking all night everybody

or nearly so is sick, half in bed including myself. I had something brought to me to eat, but

very little (although I’m so bad I cannot eat).

I was forced to laugh when George and the other fellows were getting up,

every few minutes the boat would give a big heave, and one of these fellows a

young “fool” (sleeping on opposite side to us) instead of going out to wash was

washing in room, when suddenly the boat gave a big swing and his water was

dashed all over, and came on to George’s bed, practically everything was moving

in the room. I had some bottles on

washstand, one of Eucalyptus oil was broken and spilled, they are all growling

about the smell of oil. They had to

dress by instalments as they could not stand for long at a time. Our berth is an outside one, with a port

hole, or little round window and as we lie we look right on a level with the

sea and watch the great waves rising mountains high, beating away and rising

again.

I’m told

there were very few people at breakfast this morning. The little window was sunk deep into the

water, and then right into the air, making the room first dark and then

light. Which was rather unpleasant and

making one more dippy. I tried several

times during the morning to get up and failed, but at last after dressing at

intervals, unwashed and collarless, with overcoat and rug, I managed to crawl

on deck, and found there a fine state of affairs, which was quite a novelty to

me. The fore part of deck, as the wind

and rain was facing in the night before they had run canvasses round to keep

out the storm which formed a good warm shelter on each side of deck.

Instead

of people walking gaily round deck, they were huddled in these covers lying, a

helpless mass of human beings anyhow to get ease. However I took my place and lay for hours on

the hard deck with just my rug. This was

the most any of us did.

There

were, of course, a few people moving about and could afford to laugh at us but

everyone was effected more or less and those who walked staggered like drunken

men, and it was only by the aid of stormy ropes that anyone was able to walk. On these occasions they tie strong ropes from

side to side and from end to end of deck, for supporting passengers, the waves

are rising and splashing on deck.

It is

indeed a fine sight to watch a rough sea and it is fine also to be right in the

midst of it, and have the same sight all round.

There were no chairs used today they would not allow anyone to use them

and I should think, no one would wish to use them. The Stewards and Stewardesses were busy all

day attending helpless people on deck and in bed, for very few people went to

meals. Towards evening the sea calmed

slightly and many of us began to walk about a little. I walked a good deal and by bedtime felt a

lot better but stayed out very late on deck and we saw a decided change in the

weather, before retiring. This will

appear to have been a bad storm but a storm is not very bad and there is

nothing takes it place and I must say I have enjoyed

it more than anything else all the way and after it was over was glad I’d been

in it; for it is an experience worth having.

They say

we passed some more sailing vessels today.

George

and Beckwith had been chaffing me all the way, about being ill, and said it was

homesickness, but on this particular day they had not much to say. George was ill a little, but Beckwith was not

much affected; he had been in to every meal; even he was a bit pale.

Friday

6 April 1911

This

morning the sea is quite calm, but there is some fog, and it is a bit chilly,

although there are a few sick people, most of them have turned out today, but

are still looking pale. Everybody seems in better spirits and there is much

more activity on board. There are

notices up this morning urging us to get our money changed; that the Purser

will change money at certain times during the day. Also asking Halifax passengers to sign their

names to a list in saloon entrance so that their luggage may be sorted. The next time I travel over here I shall be

on a quicker boat, six days is long enough unless it was in Summer when it

would be very pleasant. We have been in

a thick fog today, and the fog signal is most deafening. I was looking forward to my voyage but am now

looking more eagerly to the end of it. I

don’t like the smell of the sea now.

The party

of “blue bow ladies” are having a meeting, I suppose arranging for landing.

On the

two stormy days the guards were round the tables to keep the things, they are

not a little inconvenient they just resew them on the edges over the table

clothes.

Saturday

7 April 1911

There is

a strong wind blowing, but the sea is very calm. Rather cold and foggy; everybody is looking

anxious and the chief topic of conversation is; what time shall we reach

Halifax tomorrow, for after today’s reports we now know that if all goes well

we shall land tomorrow. Everyday they put up the report on progress and we know how

many miles we have done and how many still to go; it is shown on a chart just

how we are going and the route. The

tables are all filled today and everybody seems quite recovered. There is, tonight, a concert organised by

passengers, it is the final. They have

got our programmes and are 3/- each and are going for seamens

orphans etc.

My

seasickness cure did no good, or perhaps I didn’t give it the chance. I simply hadn’t energy to take it. I should never bother with anything except a

little special diet. I have been told by

many people to eat whether having an appetite or not, but I will never act on

that advice again. I think that is

wrong; fasting for a few days is more likely than the other. Sea-sickness is not worth thinking about, as

it never kills, its no obstacle, but there is a great

difference in people; an old Sea Captain told me (who’s been a sailor all his

life) that he is still sick every time he goes to sea and some folks are

half-dead, whilst others are not affected in the least.

The

clocks have been put back half an hour each night at midnight since we left

Liverpool. The sea is tonight very calm;

the sky is quite clear and I’ve been watching the first American sunset which

is exceedingly pretty.

I have

been down several times looking among the 3rd class, the conditions are very

bad, the people are fearfully crowded, and they have no room to walk about as I

escaped on the stormy days they could not go out on deck as they are only a

trifle above the water line, they would be washed overboard. There are a good

many foreigners down there, also, but there aren’t any on 2nd class.

The

concert passed off very well, the proceeds were £6-17/-. There was a collection in addition to the

selling of programmes, and it all goes to same cause. The chair was taken by the Chaplain and the

saloon was packed.

Tomorrow

we breakfast half an hour earlier, as they expect an early landing.

Sunday

8 April 1911

Everybody

is astir early, and the deck is crowded with people looking for land. It is a very clear morning, but severely

cold. People are packing and getting out

their baggage, the gangway is being crowded with piles of baggage.

After

breakfast we tipped the Stewards; each passenger tipped their bedroom and table

steward. I expect they are very badly

paid and so probably rely on tips. It is

rather a nuisance, but there is one good point about it, they are much more

obliging. When they expect something,

each table steward has about eight to attend and bedroom steward so many rooms,

so they will make a good thing as some will give each a dollar, some more, and

of course many less.

About 9

o’clock:- they slow down and are waiting and watching for pilot everyone is

flocking to the decks . We all expected

we had our last meal on board, when to our great disappointment, a dense fog

set in and presently it came on a snow storm and blew very hard and we all had

to retire to saloons, there to await developments. There are all kinds of rumours that the pilot

is lost and that we are scouting round finding him, once we came to a stop, for

first time in nine days, but there is no news of pilot.

However

the storm still goes on, and we have now turned round and going back into sea,

and it is definitely settled that we shall not land today. We are just hovering around passing away

time in a thick fog and blinding snowstorm.

So we have, after all our preparation to settle down again.

This

afternoon a good many people were in the saloon and the Chaplain invited a vote

as to whether he should have a service and we had one, which was very nice and

put time on. A woman down in 3rd class broke her leg and they are gathering for

her and will be delayed in port, they have collected about £10.

I was

really glad we were staying on all night, as I’m afraid we should have spent a

rough day on land probably at Halifax and we were quite safe on board.

Monday

9 April 1911

They were

all astir quite early about six o’clock.

I went out on deck and found we were sailing right into port with land

on each side. The hills were all covered

with snow and looked very rugged. The

snow the previous day had made the deck very slushy and was fast melting.

After

breakfast, everybody seemed to be on deck and there was tremendous bustle and

excitement as we sailed up to Halifax.

Unfortunately,

however, there was another large Ocean boat sailing in ahead of us and of

course that meant delay. It was the “Hesprian”, which sailed the day after us. There was a rumour that she had nearly run

into us the night before, amidst the fog, but she no doubt was a little too

near us.

The

Doctor and Inspectors came on and went down amongst the 3rd class passengers.

Tugboats

were steaming about and after what seemed a very long wait they pulled us up to

the landing stage. They were soon at

work getting out the baggage and everything was brisk. Halifax looks a very old-fashioned town. There was quite a lot of sleighing going

on. We could see them in the streets

from the boat. We however, again lunched

on board and it was somewhere about 2pm when they headed us all in the largest

saloon and the inspectors were soon at work.

We have to produce our sailing tickets and a ticket which is given in

the day before by boat officials and all families together. They want to know what we have done in

England? How much money? What are we

going to do and are we going to stay?

They give us a stamped ticket and its

over. We pass on.

Halifax

pier 1905

The

Doctor just sits and watches us all pass; of course there is a Doctor on board

all journeys and he talks with Gov and so suppose he knows if any one on board ails anything.

It was

about 3 o’clock when they at last allowed us to go off and we just had to show

the ticket given us. We carried our bags

which were very heavy and the man at the further end of custom houses passed

them and allowed us to pass out.

We moved

on to a restaurant in the town, where we left our hand baggage and had supper.

We then

found Post Office and posted letters, had a look through town. There was not much but fast melting snow;

hence the slush. It is not a very large

place, but has its car service. It lies

in a very hilly position, right on a hillside.

There does not seem to be much business going on here, the shops are

small and mean looking. So that there

was nothing worth wasting time over.

Some of our party were inclined to stay all night but we finally decided

to get out as soon as possible.

It was

quite unnecessary but we felt safer having it with us. The stewards from boat carry it right into

Customs House for us, and its quite a simple matter

getting them to do if, if one looks after them.

Our next

business was rather more difficult, sorting out our heavy luggage and getting

it passed. It is just piled up in huge

heaps, tons of it and it is difficult in such a crowd. There were two boats landed on this

particular day and two before were estimated 5,000 landed in three days;

imagine the crowds, it was intense; so it will be easy to imagine the slowness

of the process of sorting luggage. There are no porters to do everything as in

England but everybody has to look after their own. However, after a lot of trouble turning over

heavy bags we finally found each of our own.

The customs men just walk round with chalk and mark them but the

difficulty lies in getting them, as everyone wants them at same time, so that

when one comes our way, we just have to make a rush at him, and try to persuade

him to work at ours, so at last we were successful. He asked what we’d got in, if we’ve anything

he can collect duty on. Its so easy to say no but we had high hopes and quite

prepared to let him have a look if he was so inclined. However he passed it without further trouble.

We next

had to proceed to RG checking office, a very important matter, we showed our

tickets and they gave us checks, one of which had to be put on boxes. When we came to mine, the fellow fumbled

asking if it contained lead. I informed

him there was not more than 300lbs and asked if he wished to see what it

contained but he said they would not allow so much weight in our package,

however he finally passed it over and I was alone with it for the time being.

The

trains had all been sent off, they could not get the immigrants away quick

enough; we found it would be hours before we could be away.

People

were lying about in the shelters, it was so crowded, the place very hot, but we

were bound to stay there and wait.

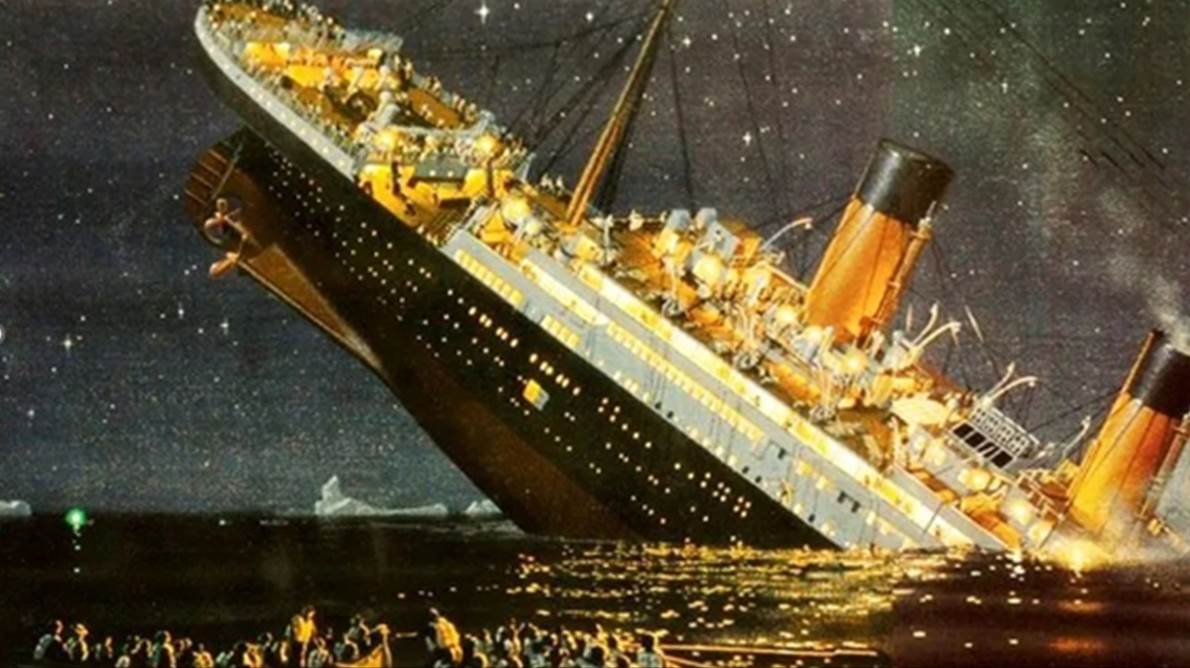

RMS

Titanic, April 1912

RMS

Titanic was a

British ocean liner that sank on 15 April 1912 after striking an iceberg on her

maiden voyage from Southampton, to New York. Of the estimated 2,224 passengers

and crew aboard, about 1,500 died. This was one of the deadliest peacetime

sinkings of a single ship.

RMS

Titanic was operated

by the White Star Line and carried some of the wealthiest people in the world,

together with hundreds of emigrants. The disaster drew public attention, and

caused major changes in maritime safety regulations. RMS Titanic was the

largest ship afloat when she entered service and the second of three

Olympic-class ocean liners built for the White Star Line. The ship was built by

the Harland and Wolff shipbuilding company in Belfast. Titanic was under the

command of Captain Edward John Smith, who went down with the ship.

Kate

Farndale, July 1913

Catherine

Jane (“Kate”) Farndale went to Canada in 1913. She travelled on the

Victorian from Liverpool to Quebec arriving on 24 July 1913.

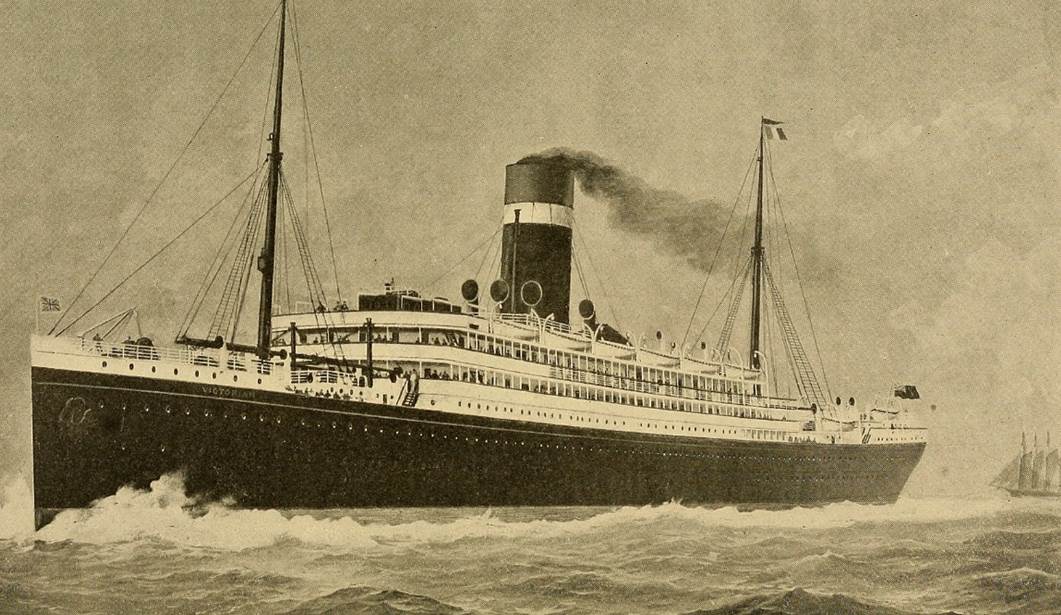

RMS

Victorian was the

world's first turbine-powered ocean liner. She was designed as a transatlantic

liner and mail ship for Allan Line and launched in 1904. She was built in

Belfast and had a sister ship, Virginian. When RMS Titanic sank

on 15 April 1912 RMS Victorian was about 300 nautical miles, some 560

kilometres, astern of her, travelling in the same direction. Victorian's

wireless operator received news of the sinking from RMS Carpathia via RMS

Baltic. The operator told Victorian's Master, Captain Outram, but

her passengers were not told until she reached Halifax. Outram said that Victorian

had to divert very far south to avoid icebergs, and that his lookouts

saw a great field of ice and 13 icebergs at one time.

William

Farndale, August 1913

William Farndale

was a passenger on the Victorian, a ship on the Allan Line, departing 13

August 1913 from Liverpool to Quebec, recorded on the manifest as a labourer,

aged 22.

Alfred

Farndale, March 1928

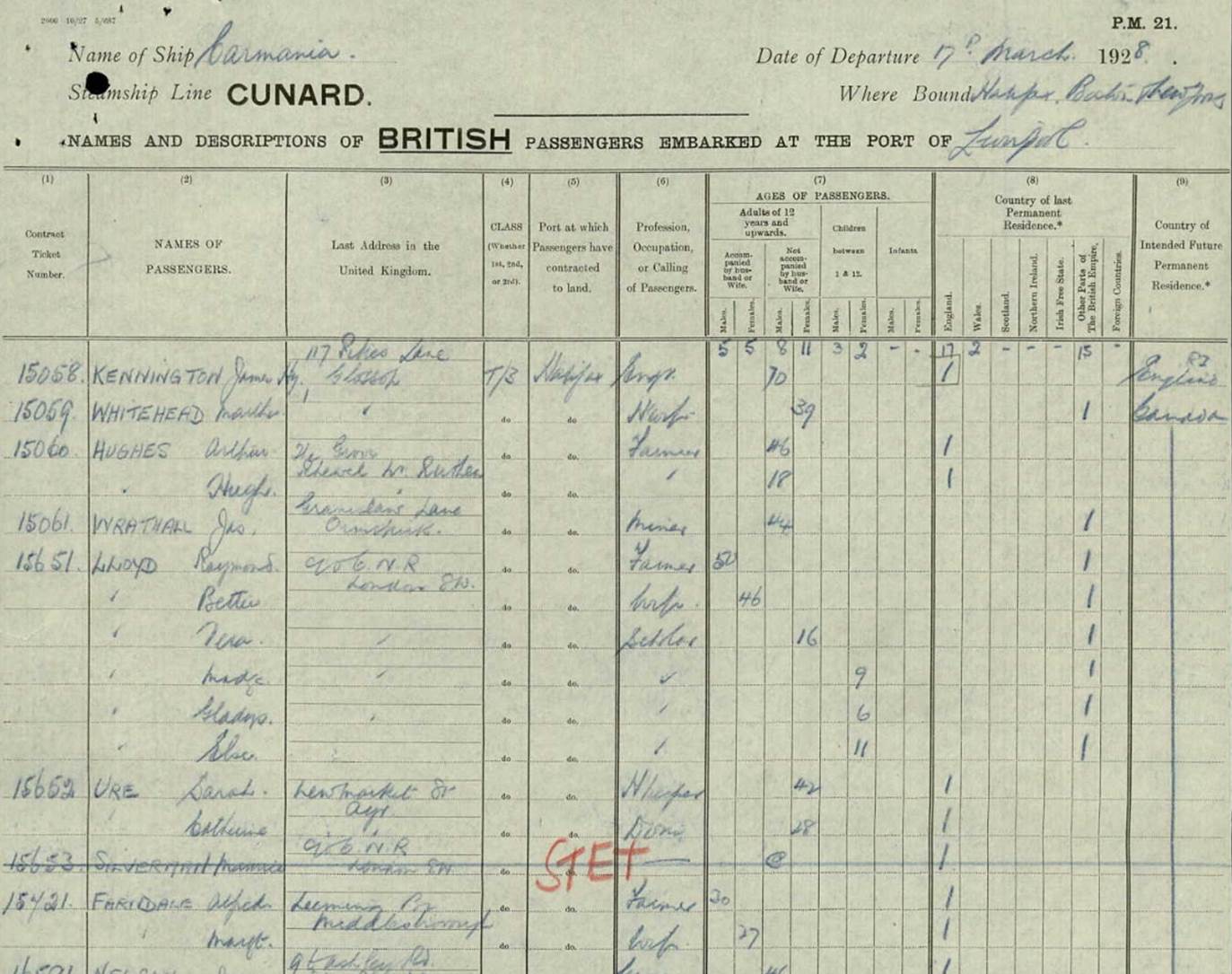

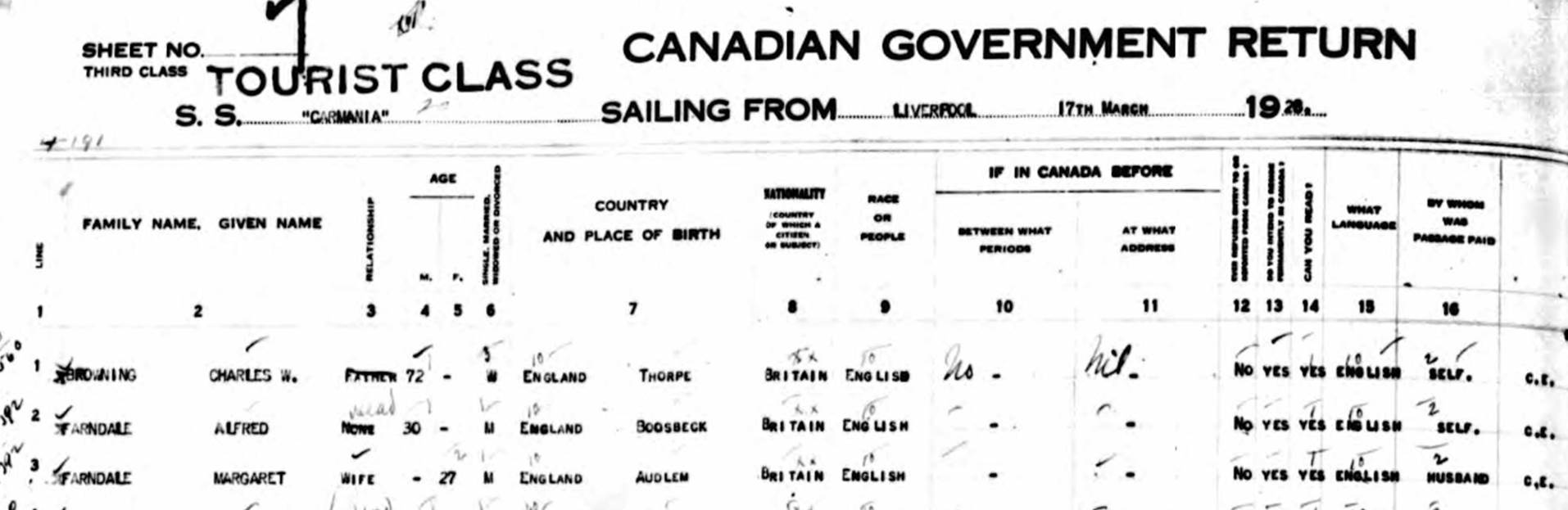

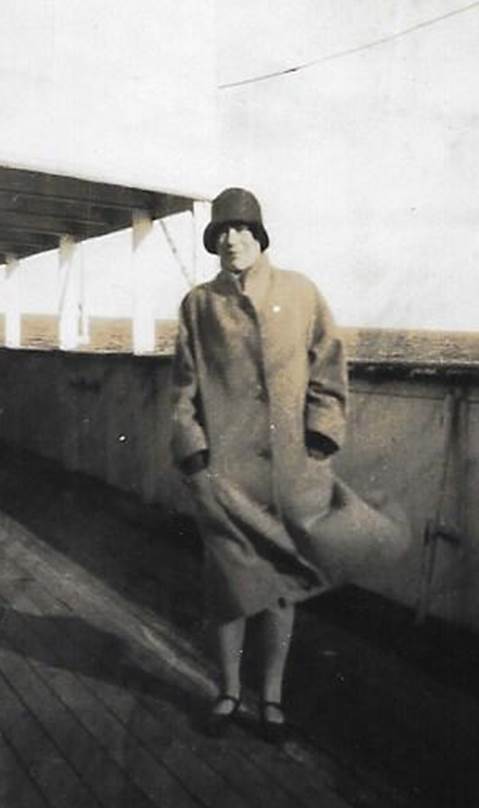

Alfred

Farndale married Peggy

Baker and Bedale church on 16 March 1928 and immediately after their

wedding they travelled to Liverpool to cross the Atlantic and start a

new life on the Prairie.

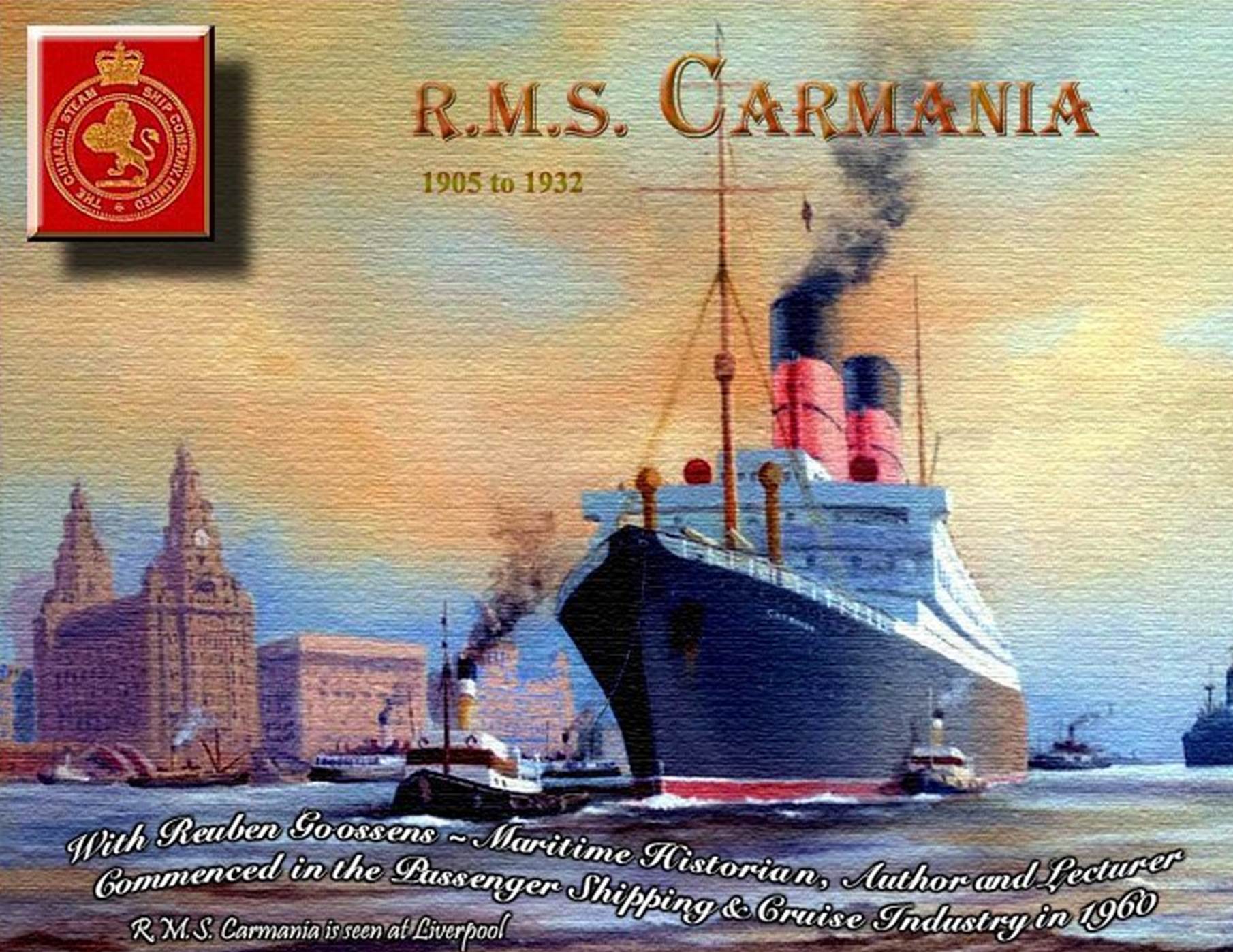

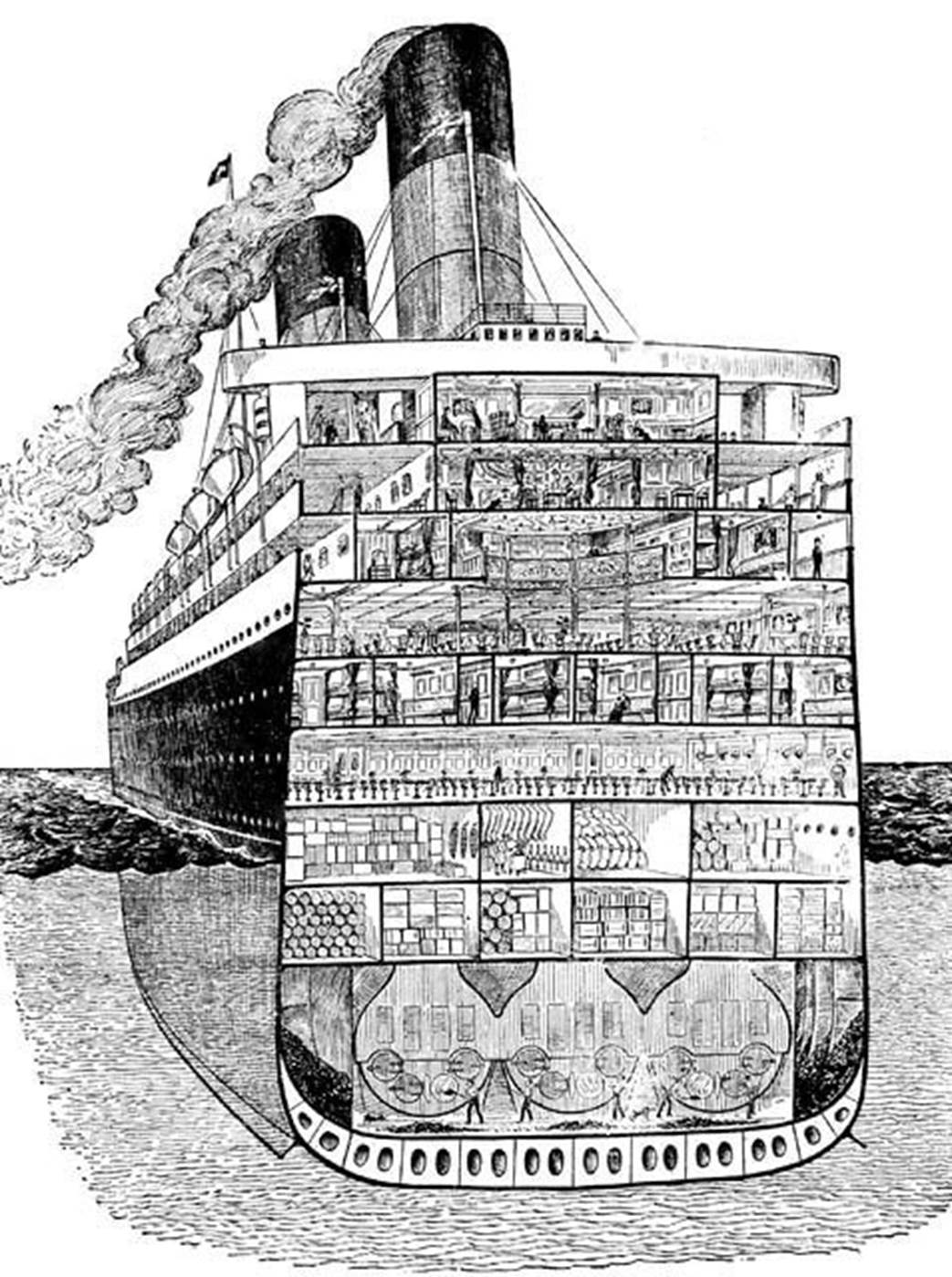

They sailed

for Halifax on 17 March 1928, the day after they were married on the Cunard

line ship, the RMS Carmania, a transatlantic steam turbine ocean liner,

in service from 1905 until she was scrapped in 1932. She had been refitted as a

cabin class ship in 1923, with 1,440 berths.

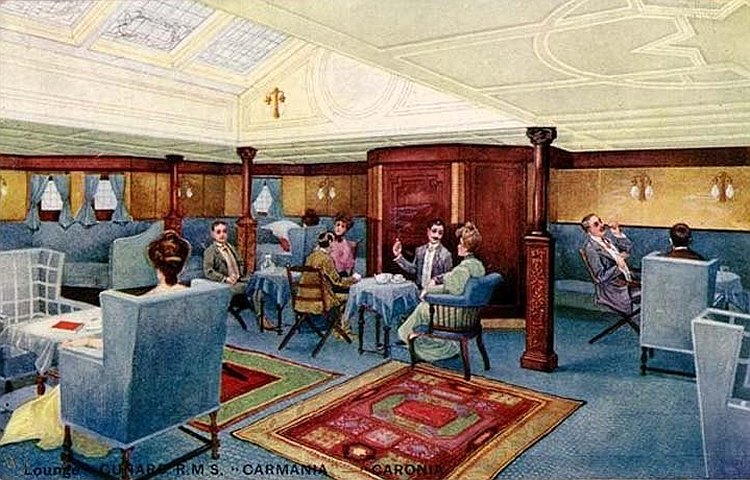

The First

Class Passengers

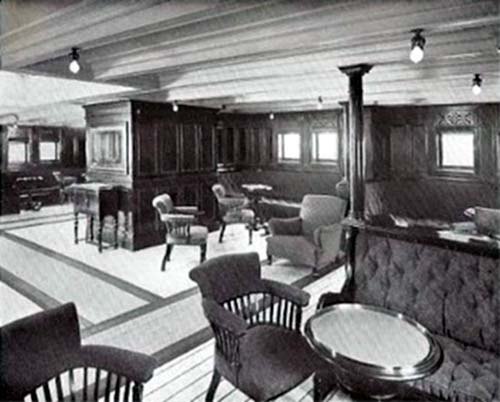

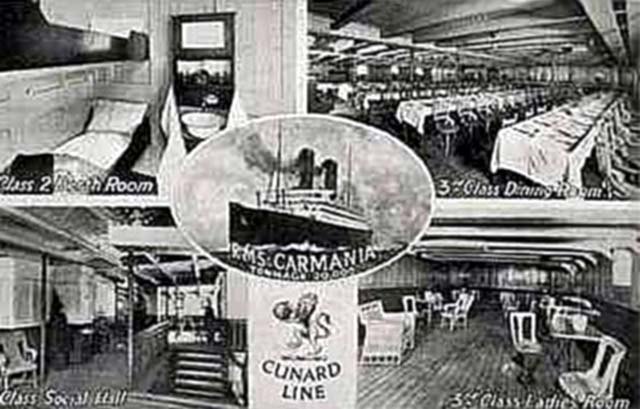

The Second Class Smoking Room

Second Class Dining Room

Third Class

had a very large Dining Room located amidships seating 500 at a time, and it

was panelled with American Ash and teak dado. The tables were fitted with

revolving fitted chairs, and there was a sideboard as well as a piano for

entertainment. There was a Smoke Room and a Ladies Room both with comfortable

lounge chairs and tables, as well as ample deck space. There were cabins for

two, four six berths, all with wardrobes and washstands. Ample public

facilities were provided and they were maintained to Cunard’s standards. The

Steerage passengers stayed in large dormitories.

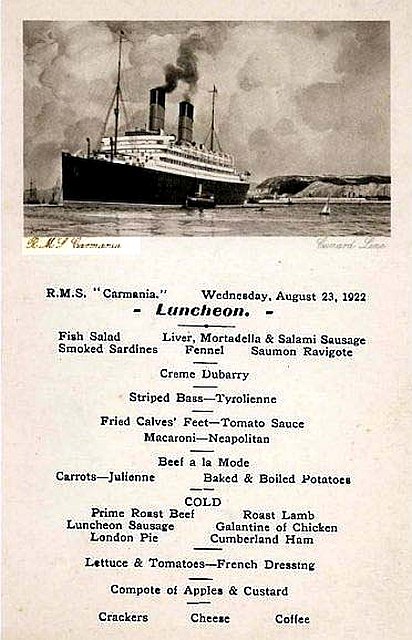

Lunch

menu in 1922

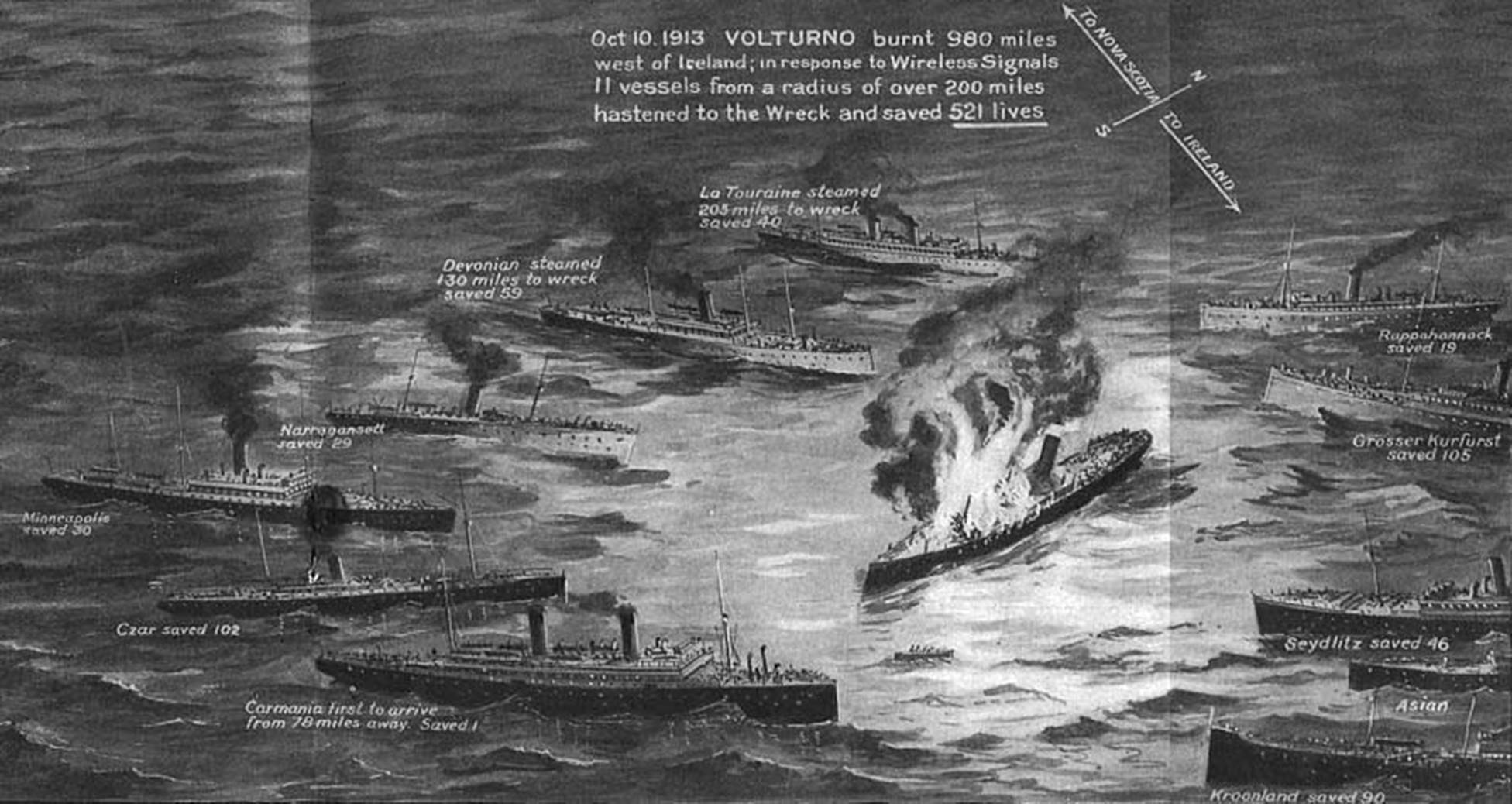

RMS

Carmania had been

involved in a rescue after the SS Volturno

caught fire in the Atlantic in 1913.

Grace

Farndale, 1928

Grace

Farndale followed her brother Alfred,

and her best friend Peggy

to Canada, crossing the Atlantic shortly after them in 1928, on the Athenea.

SS

Athenia was a steam

turbine transatlantic passenger liner built in Glasgow, Scotland, in 1923 for

the Anchor-Donaldson Line, which later became the Donaldson Atlantic Line.

After the construction of the Pier 21 immigration complex in Halifax in 1928,

Athenia became a frequent caller at Halifax, making over 100 trips to Halifax

with immigrants. She worked between the United Kingdom and the east coast of

Canada until 3 September 1939, when a torpedo from the German submarine U-30

sank her in the Western Approaches. Athenia was the first UK ship to be

sunk by Germany during World War II, and the incident accounted for the

Donaldson Line's greatest single loss of life at sea, with 117 civilian

passengers and crew killed.

I went on

the Athenia a small ship, ill-fated as it was sunk in the Second World War. It

was a nice ship. There were 1,000 third class passengers in the bowels. I was

second class and I got mixed up with a lot going on to the ship. There was a

doctor asking questions in a sort of wire cage place, about health etc and how

many illnesses we'd each had we'd had etc. He asked me the name of my doctor

and I said I hadn't one. He gave me a hard look and smiled and said, “very

good”. Martin was around and was mad and said they had no business to be

questioning me. When they found he was with me and I was going to relations and

had enough money, they let me through. Great relief! It was a great thrill

going on the boat and finding one's berth. There was a lot to do and all our

papers were again checked. One was continually pestered, and red tape. I was so

excited, I pushed back into my handbag and could never find anything.

We were

in time for lunch when we got on board. It was a bit of a scramble but an

excellent lunch. In fact the whole voyage the food was sumptious.

I shared a berth with a middle-aged woman going out to be married. She was an

old fashioned cup of tea. It was 1928 and I was amazed at the amount of

clothing she wore, woollen combs and about half a dozen petticoats, to say

nothing, over a red flannel and white embroidered one on top. I didn't know

people wore so many in that day and age. I had only a vest, girdle, stays, and

pants and pulled them off with one stroke and was into bed. This person was

very nice and told me she hadn't seen her future husband for 26 years and

wondered if he'd think she'd changed. I tried to persuade her that she would be

alright. I wondered though.

After I

got settled into my berth, I went out on deck and I met an awfully nice girl

from Pickering, a doctor's daughter, travelling alone, Joan Kirk. We chummed up

and had meals at the same table and were together the whole way. She was

visiting her brother at Hamilton, Ontario, a poultry farmer. We had a lot of

fun together. She was a tall pretty slim girl, quiet, age 21. We were both

seasick and sat on deck chairs. A very nice young waiter brought our food out

on deck for us. We had rugs and were very comfortable until we tried to walk

and we were like drunken sailors. But we never missed a meal. Joan and I did

rather keep our keep to ourselves. Martin lectured us from time to time about

not walking and getting our sea legs. But we went on sitting. There was another

girl who rather hung on to me, a nervous young person, on her own. I just had

to look after her in the end. She was delicate and couldn't cope with herself.

She was alone.

It was a

rough journey and took nine days and we were glad when we saw land. I remember Martin saying,

“take your first look at Canada.” We were held up with Canada fog before we

could enter Halifax. The minute we stopped, the sea sickness ended. I never

felt better in my life, could have jumped over the moon with joy. They made

Joan and I go through a lot of paraphernalia again when we arrived. Martin went right off and he said he would be there when I

got off. The delicate girl they found was TB and wouldn't let her enter. She

got hysterical and clung on to me saying, “don't leave me.” However they took

her away and I never knew what happened. I was distressed about her. I was

worried sick Martin wouldn't be there, we were so long in getting off the

ship. Joan and I had our hand luggage, as much as we could carry, and a black

man carried the rest for us to the train, which was wasn't far away. He set off

at such a rate, we ran and couldn't catch up to him. We giggled so much, and Martin came along, very amused.

or