|

|

Doncaster

Historical and geographical information

|

|

Introduction

Hyperlinks

to other pages are in dark

blue.

Headlines

of the history of the Doncaster are in brown.

References

and citations are in turquoise.

Contextual

history is in purple.

This webpage about the Doncaster has the following

section headings:

·

The

Farndales of Doncaster

·

The

History of Doncaster

·

Doncaster

Timeline

See also the History of

the Parish of Doncaster and Loversall and Campsall.

The Farndales of Doncaster

The following Farndales are associated

with Doncaster:

(Sir) William

Farndale (FAR00038), was Vicar of Doncaster between about 1396 and 1403. We

first see his name in a grant of land in Latin by Walter de Thornton, the vicar

of Doncaster, and Wm de Farndell, his chaplain on 11 April 1355. Perhaps

William may have been about twenty then, so perhaps he was born in about 1335.

The Black Death had ravaged Doncaster from about 1349, and its population had

been reduced to about 1,500. So William must have survived the Black Death.

Perhaps he was already a chaplain then, experiencing the horrors with pastoral

responsibilities. Or perhaps it was his survival of those horrors that was his

path to the church. We then spot him again in the patent rolls

of 1358. On 7 December 1368, Robert Ripers

transferred five acres of land at Lovershall (just

south of Doncaster) to Sir William Farndale, still chaplain. The term ‘sire’

was used as an address to religious men such as priests, it does not denote a

knight. ‘Know men present and to come that I Robert Ripers

of Loversall have given, granted, and by this my present charter confirmed to

Sir William Farndale, chaplain, 5 acres of land with appurtenances lying in the

fields of Loversall, extending from the meadows of the Wyke to the Kardyke, of which 1 acre 1 rood lie in Wykefield

between the land of Robert son of John son of William, son of Robert on both

sides. And 2 1/2 acres lying in the Midelfild between

my own land on the west and the land of Richard son of Robert on the east. And

1 rood lying in Wodfild between my own land on the

west and the land of John of Wakefield on the east. To have and to hold the

said 5 acres of land with appurtenances to the said William and his heirs and

assigns, freely, quietly, well and in peace, from the chief lords of the free

by the services then owed and customary by right. And I, said Robert, and my

heirs, will warrant the said 5 acres with appurtenances to the said Sir

William, his heirs and assigns against all men for ever. In witness whereof I

have affixed my seal to this present charter. These being in witness; Sir John

of Loversall, Chaplain; William Vely, Robert Clerk,

Richard Rilis, John son of William son of Roger and

others. Given at Loversall on Thursday after the Feast of St Nicholas, 42

Edward III. (7 Dec 1368).’ Sir William Farndale then became the Vicar of

Doncaster from 8 January 1397 (aged about 61) to 31 August 1403 (aged about 68)

when he resigned.

William

transferred his land at Lovershall to John Burton in

1402; “‘Know men present and to come that I, William Farndalle,

Vicar of the Church of Doncastre, have given, granted

and by this present charter confirmed to John Burton of Waddeworth,

his heirs and assigns 5 acres of land with appurtenances lying in the fields of

Loversall. Viz, those 5 acres of land which I had as gift and feoffment of

Robert Ryppes of Loversalle

and which extend from the meadows of the Wyke to the Kardyke

as the charter drawn up for me by Robert Ryppes more

fully sets out. To have and to hold the said 5 acres of land with appurtenances

to the said John Burton, his heirs and assigns from the chief of the lords of

the fee by the services thence owed and customary by right. And I William Farndalle and my heirs will warrant the said 5 acres of

land with appurtenances to the said John Burton, his heirs and assigns against

all men for ever. In witness whereof I have affixed my seal to this present

charter. These being witnesses; John Yorke of Loversalle,

Robert Oxenford of Loversalle, William Ryppes of the same, John Millotte

of the same, William Clerk of the same and many others. Given at Loversalle 6 April 3 Henry IV. (6 April 1402).”

In 1403 we see

the installation of William Couper as the vicar of Doncaster, on William

Farndale’s resignation.

On 29 October 1564 a

wedding took place between a William

Farndell and a Margaret Atkinson in the Church of St Magdalene in the

village of Campsall, which is only a few miles north of Doncaster. So on a

balance of probabilities, it seems more likely than not that William Farndell

who married in 1564 came from the same line of Farndales as William Farndale,

the vicar of Doncaster. There must have been a generation or two between them.

It is possible that William the Younger was descended from a brother of William

the Elder, or perhaps he was a direct descendant.

It is believed

that Nicholas Farndale (FAR00059)

and Agnes Farndale (FAR00060),

who both died in Kirkleatham, were born in Campsall or thereabouts, around

Doncaster, perhaps in about 1512 and 1516 respectively. If so, they were likely

descended from William Farndale (FAR00038),

the Vicar of Doncaster, or at least from his wider family (his brother

perhaps). William Farndale junior (FAR00063)

was born in say 1538, and Jean Farndale (FAR00064)

in say 1540 to Nicholas and Agnes. William Farndale married Mary Atkinson at

the Church of St Mary Magdalene in Campsall in 1564. Between 1564 and 1567, the

family moved to Kirkleatham. We don’t know why. Maybe that was Agnes’ ancestral

home. Perhaps more likely Jean had met Richard Fairly, a relatively well

established fellow, whose family were Scottish, but who had more recently

become associated with Cleveland and Kirkleatham. Perhaps the family saw

opportunities by a move north. On 16 October 1567, Jean married Richard Fairley

in Kirkleatham. The family lived generally at Kirkleatham until Nicholas and

Anne’s death in 1572 and 1586, though William had by then realigned slightly

eastward, to Skelton. This established the family tree

for the Doncaster-Kirkleatham-Skelton

Line of Farndales.

Others associated with Doncaster were

William Farndale (FAR00063);

Thomas Farndale (FAR00474);

James Farndale (FAR00669)

who worked in animal husbandry and served with animals in both world wars.

The History of

Doncaster

The Deanery of

Doncaster is one of three historic divisions of the old West Riding of

Yorkshire. This is an area rich in coal and iron. Modern Doncaster is strongly characterised by its

industrial past. However the Doncaster of relevance to the history of the

Farndale family was a very different place.

It was the

place of a significant Roman Fort. After the Norman Conquest, Nigel Fossard had built a Norman Castle. By the thirteenth

century, Doncaster was a busy town. In 1194 Richard I had given the town

recognition by bestowing a town charter. There was a disastrous fire in 1204

(fires seem to feature heavily in Doncaster’s history) from which the town

slowly recovered.

In 1248, a

charter was granted for Doncaster Market to be held in the area surrounding the

Church of St Mary Magdalene, which had been built in Norman times. But over

time the parish church was transferred to the church of the old Norman castle,

the castle which by then was in ruin. The new parish church was the

original Church of St George. During the 14th century, large numbers

of friars arrived in Doncaster who were known for their religious enthusiasm

and preaching. In 1307 the Franciscan friars (Greyfriars) arrived, as did

Carmelites (Whitefriars) in the mid-14th century. Other major medieval features

included the Hospital of St Nicholas and the leper colony of the Hospital of St

James, a moot hall, a grammar school and a five-arched stone town bridge with a

chapel dedicated to Our Lady of the Bridge.

Doncaster 1857

Doncaster Timeline

The true

origin of Doncaster is evidently to be found in the necessity for some means of

crossing the Don at this place.

The sixteenth century historian, John Leland,

wrote I marked that the North parte of Dancaster tonne standith as an

isle: for Dun river at the West side of the towne castith oute an arme, and sone after at the Este side of the town cummith into the principal streame

of Dun again. The fluvial islands probably attracted early settlement and

the islands might have been the home of the ferry man. The island and the

relatively low banks might have been the best place for a road to cross in

time. (South Yorkshire, the History and Topography

of the Deanery of Doncaster in the Diocese and County of York by Rev Joseph

Hunter, 1828, page 1).

The Don was the approximate southern

boundary of the Celtic, Brigantes, dividing them from

the Coritani to the south. At the passage over the

Don where Doncaster now stands, it is probable that the Brigantes

had a settled residence (South

Yorkshire, the History and Topography of the Deanery of Doncaster in the

Diocese and County of York by Rev Joseph Hunter, 1828, page iii).

43 CE

From the year 43 CE, Roman

influence had transformed the way of life of people in southern and eastern

Britain. The emperor Claudius commanded a force of some 40,000 men, with

elephants to boot. They were grouped into four legions supported by auxiliaries.

Initially the

Romans did not venture north of the line of the Humber and Don, but traded with

the Parisii,

though the Brigantes generally remained hostile.

54 CE

The

Romans built a series of advanced forts at Derby, Templeborough

and Castleford to support Cartimandua, the Brigantes’

Queen. The rectangular fort at Templeborough stood on

the south bank of the Don, about 12 miles southwest of the site of modern

Doncaster, where Rotherham now stands. 800 soldiers of the 4th

Cohort of Gauls were stationed there until 69 CE,

after which Venutius overthrew the Brigantes queen. This led to the Romans consolidating their

position by moving the Ninth Legion from Lincoln to York in 71 CE. At Templeborough the timber fort was replaced with a new

sandstone fort. (The Making of South Yorkshire,

David Hey, 1979, p13).

71 CE

In 71 CE the newly appointed Roman

Governor, Petillius Ceralius

marched north to occupy Brigantes and Parisii territory. The Ninth Legion perhaps erected a large

camp near where Malton, northeast of York, stands today.

A significant

military camp was founded by the Romans as Eboracum

(modern day York) in 71 CE.

The passage

over the Don at the Doncaster site would require protection. This was also the

site of the limit of inland navigation for coastal vessels. The local of the

modern St George’s Minster was favourable for a Roman castrum. The

establishment of a castrum and a company of soldiers was an inducement

to settlers.

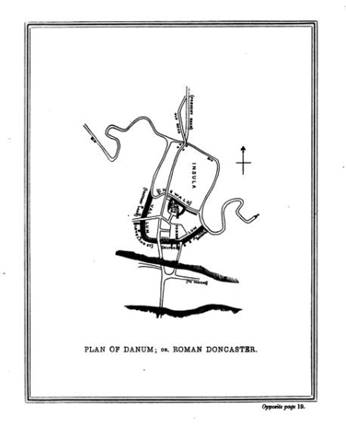

A fort at Danum (modern

Doncaster) was established soon after 70 CE and was large, stretching to about

nine and a half acres, with timber buildings and a cobbled road. This original

fort was abandoned at the time of the building of Hadrian’s Wall in 122 CE and

rebuilt on a smaller scale from 160 CE, then stretching to about 5.85 acres

surrounded by a stone wall which was 8 feet wide. (The

Making of South Yorkshire, David Hey, 1979, p13).

More

substantial settlement on the Doncaster site grew up around the Roman fort

known as Danum of the 1st century CE. This was within the Roman province

of Maxima Caersariensis. Strictly Danum was

the Roman name for the river and the Roman’s referred to the place as Castrum

ad Danum. Around Roman Danum emerged building to the south side of the

river, based on the favoured plan of two streets intersecting at right angles.

The town was thus divided into four quarters and the island in the Don. In one

quarter was the castrum and its praetorium (headquarters) and in another

quarter there would have been a market. There were two gates, the Sepulchre

Gate and Baxter Gate. Excavations in 1976 revealed that the civilian settlement

was much larger than originally thought.

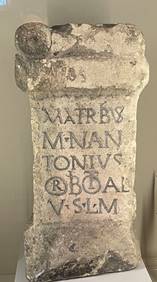

The Doncaster

altar (to be seen today at the Doncaster library) was found at the Sepulchre

Gate and was inscribed To the Mother Goddess. Nonnius

Antonius has freely and deservedly fulfilled his vow. There have also been

finds of a coin hoard and pottery and glass.

Danum rose where Icknield (or Ricknield) Street, which ran from Bourton to Eboracum

crossed the Don. The Romans adapted much of this road from a prehistoric route.

The main road from Lincoln approached Danum from the south with a minor

crossing at Rossington Bridge, just south of Doncaster, in the approximate area

of Loversall. There is considerable evidence of

Iron Age and Roman field systems in this area. The road then continued to cross

the Don at Danum. From Danum the road then continued joining the line of the A1

and passing near to Campsall, through the forest of

Barnsdale. (The Making of

South Yorkshire, David Hey, 1979, p14 to 16).

Four miles south

of Doncaster and in the vicinity of the fort at Rossington Bridge, the rich

farm lands encouraged wealthy Roman Britons to build their villa at Stancil,

which was later the place of a medieval village. A wide range of vessels have

been found in this area which evidence trade as far north as lowland Scotland.

In Roman

Doncaster, the present market-place was in all probability used then for the

same purpose that it is now. It would also contain, as most Roman market-places

did, the public Temple. At all events, on whatever other site such Temple may

have stood, it could hardly have been on that of the Church of St. George; for,

in the times of which we are speaking, that site was unquestionably the true

Castrum, or Pretorian Camp, a military fortress, or barrack, enclosed within

special defences of its own

(from Rev Jackson, History of the ruined church of Mary

Magdalene, 1853)

The Roman fort

was regarrisoned and was occupied until at least 390 CE, towards the end of the

Roman period. There seem to have been town defences by the end of the Roman

era.

Sixth

Century

The Don became

the boundary between Deirans (later the Northumbrians)

and the Mercians to the south.

The old Roman

roads continued in use, but settlements tended to develop in more secluded

places, some distance away from the roads.

627

CE

Edwin of

Northumbria (586 to 633) was baptised in York about 15

years after the death of Augustine.

When Augustine

came to Britain, he does not appear to have attempted to bring his mission to

Northumbria. However Edwin, King of Northumbria, married the daughter of

Ethelbert, the converted king of Kent and it was agreed that she should freely

exercise her religion. She was accompanied by a zealous pupil of Augustine,

Paulinus, and this provided the basis for Edwin’s conversion. From that time,

Paulinus was increasingly employed in conversion across the region of

Northumbria. One of the areas of Paulinus’ conversion was on the banks of the

Gleni and the Swale and at Campodonum (South Yorkshire, the History and Topography of the

Deanery of Doncaster in the Diocese and County of York by Rev Joseph Hunter,

1828, page xiv, Bede’s Ecclesiastical

History, Chapter 9, 14).

Bede describes

the catechizing and baptising of Paulinus during times when he

instructed crowds in Bernicia and in Deira. He often followed river courses and

baptised along the river Swale, where it flows beside the town of Catterick and

in Cambodonum, where there was also a royal

dwelling, he built a church which was afterwards burnt down, together with the

whole of the buildings, by the heathen who slew Edwin [this was when Penda

defeated Edwin at Hatfield in 633 CE]. In its place later kings built a dwelling

for themselves in the region known as Loidis. This

altar escaped from the fire because it was of stone, and is still preserved in

the monastery of the most reverend abbot and priest Thrythwulf,

which is in the forest of Elmet. (Bede’s

Ecclesiastical History, Chapter 14). Loidis

is modern Leeds. Cambodonum has been

interpreted as various locations in the West Riding, but it probably derives

from “Field of the Don” and is more likely a reference to Doncaster.

So, it is

likely that a church was erected in the place of modern Doncaster at this time.

If this is correct, then Paulinus also tells us that Edwin had a royal

residence (villa regia) at Campodonum.

The praetorium of the Roman Castrum might have been an ideal site for an

occasional royal residence. This would suggest that the church at Doncaster was

burnt down by Penda after the Battle of Hatfield Chase in 633 CE.

Bede’s work

also suggests that a second Christian church, after the church at York in 627

CE, was built in Doncaster under Paulinus’ supervision.

(South Yorkshire, the History and Topography of the

Deanery of Doncaster in the Diocese and County of York by Rev Joseph Hunter,

1828, page 4 to 5)

Edwin was killed by the pagan Penda of

Mercia and Cadwallon from North Wales at the heath field on Hatfield Chase,

10km northeast of Doncaster. It appears that Penda immediately attacked

Doncaster and destroyed the church, and probably the royal residence, as we

don’t hear of Northumbrian kings returning. However the altar was preserved in

a monastery in the wood at Elmet, around modern Leeds. There is a debate

as to whether the site of the battle was in fact in Nottinghamshire where a

mass grave was found, but the marshy land of Hatfield Chas is still generally

regarded as the site of the battle.

After the battle whilst Oswald revived

Christian Northumbria two years later, this part of the Kingdom was ruled over

by the Mercians until Penda was killed in 654 CE when it reverted to

Northumbrian rule.

Celtic Christianity was much weaker in

South Yorkshire, so it did not fall so clearly into the debate that led to the

Synod of Whitby between Roman and Celtic traditions.

764 CE

In 764 the chronicler Symeon of Durham in his Historia Regum groups York with London, Doncaster, and other places,

repentino igne vastatae (destroyed by a sudden fire). (A

History of the County of York: the City of York. Originally published by

Victoria County History, London, 1961).

Multae urbes, monsteriaque, atque villae, per diversa loca necnon et regna, repentino igne vastatae sunt; verbi gratia, Stirburgwenta civitas, Homunic, Lundonia civitas, Eboraca

civitas, Donacester, aliaque

multa loca illa plaga concepit.

Many cities,

towns, and villages, in different places, as well as kingdoms, were destroyed

by a sudden fire; for example, the city of Stirburgwent,

Homunich, the city of London, the city of York,

Doncaster, and many other places were conceived by that plague.

There is

evidence of fire in the area of the Roman castrum, but these marks may have

been the result of the devastation by Penda.

This was a time

when Alcuin of York,

in the Kingdom of Charlemagne, was despairing of the fate of his homeland.

793

CE

The Viking attack on Lindisfarne.

813

CE

Alfred of Beverly recorded the destruction of the

monastery at the mouth of the Don, which may have been a reference to Doncaster

– Monasterium ad ostium Doni amnis precaverunt, sed non impune; “They prayed

to the monastery at the mouth of the river Don, but not with impunity”.

833

CE

By 833 CE the Danes were dominating the lands around

the Humber estuary. King Ecgbert of Wessex had some success in resisting the

Danes and appears to have had some success in a battle at Doncaster. The story

of this encounter was told in the thirteenth century in a rhyme by Peter

Langtoft, an Augustine canon and chronicler from the village of Langtoft in the

East Riding of Yorkshire.

What did king Egbriht?

Without any summons.

And withouten asking of Erles

or barons …

…Right unto Doncastre ye

Danes gan him chase …

… At Donkastre mot men se manyon to batale ride …

(South Yorkshire, the History and Topography of the

Deanery of Doncaster in the Diocese and County of York by Rev Joseph Hunter,

1828, page 6)

866

CE

In 866 CE, when

Northumbria was internally divided, the Vikings captured York.

The Danes changed the Old English name for York from Eoforwic, to Jorvik. The Vikings

destroyed all the early monasteries in the area and took the monastic estates

for themselves. Some of the minster churches survived the plundering and

eventually the Danish leaders were converted to Christianity. Jorvik became the

Viking capital of its British lands and it would reach a population of 10,000.

Jorvik became an important economic and trade centre for the Danes. Saint

Olave's Church in York is a testament to the Norwegian influence in the area.

Jorvik perhaps prospered from its trade with Scandinavia.

The invasion of South

Yorkshire seems to have been made by Guthrum from the

East Midlands. A number of settlements in the lower Don valley have

Scandinavian names.

Late Saxon Period

Modern

Doncaster is generally identified with Cair

Daun listed as one of 28 British cities in the Ninth century History of the Britons traditionally ascribed to Nennius.

It was certainly an Anglo-Saxon burh,

and in that period received its present name: Don (Old English: Donne)

from the settlement and river and caster (ceaster)

from an Old English version of the Latin castra (military camp; fort).

The area of modern Doncaster was likely

not open land, but forested until it started to be cleared in the late Saxon

period. It has been described as the Great Brigantian

Forest. At some stage perhaps from late Saxon times, areas were cleared for

settlement in the process called assarting. The growth of population and

villages, including Campsall and Loversal, by the time of Edward the Confessor

suggest that assarting had been pursued vigorously by that time (South Yorkshire, the History and Topography of the Deanery

of Doncaster in the Diocese and County of York by Rev Joseph Hunter, 1828, page

ix).Joseph Hunter lists 170 vills of human

settlement by the late Saxon period. He suggested that settlement might have

been influenced by the need to cross a watercourse, but often may have been the

inclination of a family to settle on land, which larger grew into a larger

habitation. However he recognises that this informal process was soon replaced

by recognition of rights of occupancy from the lands of the elite class who

owned large estates. It therefore ceased to be open to every citizen to clear

woodland for his own use, but by the Doomsday record, a right had been

recognised in overlordship.

Thus Saxon lords came to surround

themselves with dependents who held portions of land from him, in return for

rendering services. This is reflected in culture such as Beowulf, which provided an encouragement to

live within the protection of the elite class, as protection against the perils

of unsettled places.

1003

It was Conisbrough,

within the modern city of Doncaster, which appeared as the dominant estate in

Anglo-Saxon and Viking South Yorkshire. It was mentioned in the 1003 will of

Wulfric Spott, a wealthy Mercian nobleman who founded Burton Abbey. By the

Conquest it was owned directly by Harold. It was then the centre of a large

former royal estate which reached to Hatfield Chase. Conigsborough

was head of an extensive fee. The Saxon lords of Doncaster, Laughton and Hallam

also had many dependencies. It was also an early ecclesiastical centre.

Dadesley

(now Tickhill) and Doncaster emerged as burgesses. Other centres were emerging

including Campsall, which was valued at £5 in a census of

Edward the Confessor, being one of the larger settlements.

The larger seats of population came to

be governed under the authority of a bors

holder who was elected at a general assembly. Townships were grouped in

tens under a hundreder, a superior officer who

held courts. These hundreds came to be called wapentakes in the

areas to the north. Doncaster came to fall within the wapentake of Strafford.

Doncaster and Loversall fell within the Wapentake of Strafford.

Campsall fell within the Wapentake of Osgodcross.

(South

Yorkshire, the History and Topography of the Deanery of Doncaster in the

Diocese and County of York by Rev Joseph Hunter, 1828, page xi).

1050

Just before the

Conquest, the area was probably covered in native forest, which was not dense,

so that sheep and oxen rove among the trees. Islands of land were cultivated,

varying from 200 to 2,000 acres, where agriculture was undertaken and sometimes

these settlements had mills, and Christian places of worship. Doncaster and

Tickhill, and perhaps Rotherham, had by this time become small towns.

The lands of

Doncaster were held by Tostig (Tosti), of Godwin descent, who rebelled against

his brother Harold, and died alongside the Dane Harold Hardrada at the Battle

of Stamford Bridge. He was a man of blood, and perished by the sword at the

battle of Stamford Bridge just before the conquest (South Yorkshire, the History and Topography of the Deanery of

Doncaster in the Diocese and County of York by Rev Joseph Hunter, 1828, page 8).

1066

The Battle of

Stamford Bridge near York followed by Hastings.

1070

The Harrying of

the North.

The Domesday

Book records that the value of the lands in this area had declined, and there

were many areas of wasteland.

Thereafter the

area, along with the nation of which it was a part, fell under the Norman Yoke.

1086

By the Norman

Conquest, 28 townships in what is now South Yorkshire belonged to the Lord of Conisbrough.

William the

Conqueror gave the whole lordship of Conigsbrough to

William de Warenne. Shortly after the Norman

Conquest, Nigel Fossard refortified the town and

built Conisbrough Castle.

Joseph Hunter

tells us that the wider lands of the Deanery of Doncaster were distributed in

very unequal parts to twelve persons, including Nigel Fossard

and William de Warren, William de Perci, Ilbert de Laci and others (South Yorkshire, the History

and Topography of the Deanery of Doncaster in the Diocese and County of York by

Rev Joseph Hunter, 1828, page xv).

By the time of Domesday

Book, Hexthorpe in the wapentake of Strafforth

was said to have a church and two mills.

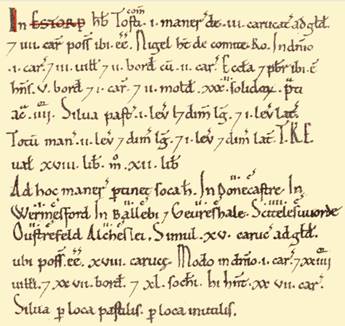

“In Estorp, Earl Tosti had one manor of three carucates for

geld and four ploughs may be there. Nigel has [it] of Count Robert. In the

demesne, one plough and three villanes and three

bordars with two ploughs. A church is there, and a priest having five bordars

and one plough and two mills of thirty two shillings [annual value]. Four acres

of meadow. Wood, pasturable, one leuga and a half in

length and one leuga in breadth. The whole manor, two

leugae and a half in length and one leuga and a half in breadth. T.R.E., it was woth eighteen pounds, now twelve pounds. To this manor

belongs this soke – Donecastre (Doncaster) two

carucates, in Wermesford (Warmsworth)

on carucate, in Ballebi (Balby) two carucates, in Geureshale (Loversall)

two carucates, Oustrefeld (Austerfield) two carucates

and Alcheslei (Auckley) two carucates. Together

fifteen carucates for geld, where eighteen ploughs may be. Now [there is] in

the demesne one plough and twenty four villanes and

thirty seven bordars and forty sokemen. These have twenty seven ploughs, wood,

pasturable in places, in places unprofitable”

The historian

David Hey says these facilities represent the settlement at Doncaster. He also

suggests that the street name Frenchgate indicates

that Fossard invited fellow Normans to trade in the

town.

Estorp (Hexthorpe) is a small village now part

of Doncaster and at the time about a mile downstream from the town became an

insignificant place after the Conquest and comprises three caracutes

of land. However to Hexthorpe were appended an extensive soke which included

Doncaster and Loversall and other places. Doncaster

comprised two caracutes which have been assessed by

historians as about 200 acres of arable land; two mills; 40 soke men, villeins

and borderers who cultivated the soil. There was no doubt a church there. The

value of the soke at the time of the Conquest was £18 but only £12 by the time

of the survey, which suggests the devastation of the harrying of the North. The

lands had been held by Tostig before the conquest, but passed after the

Conquest to Robert, the Earl of Mortain, who was King

William’s half brother. An interest in the lands was

also held by Richard the Deaf.

A

sokeman belonged to a class of tenants, found chiefly in the eastern

counties, especially the Danelaw, occupying an intermediate position between

the free tenants and the bond tenants, in that they owned and paid taxes on

their land themselves. Forming between 30% and 50% of the countryside, they

could buy and sell their land, but owed service to their lord's soke, court, or

jurisdiction.

The

carucate was a medieval unit of land area approximating the land a

plough team of eight oxen could till in a single annual season.

Tickhill 10km

south of Doncaster, was referred to as Dadsley

in the Domesday Book. Its ownership passed from Also, son of Karski to

Roger the Bully and it comprised 54 villagers, 12 smallholders, 1 priest, 1 man

at arms and 31 burgesses, with 8 poloughlandsm 7

Lord’s plough teams and 26.5 men’s plough teams. It had two acres of meadow,

woodland, 3 mills and a church. It was valued at £14. Dadsley

was an Anglo Saxon settlement meaning Daedi’s

clearing.

The

Feudal Landholders after the Conquest

Robert,

Count of Mortain in Normandy and Earl of Cornwall in England was handsomely

rewarded for his service at Hastings. Robert's

contribution to the success of the invasion was clearly regarded as highly

significant by the Conqueror, who awarded him a large share of the spoils; in

total 797 manors at the time of Domesday. In 1088, he joined with his brother

Odo in revolt against their nephew William Rufus. William Rufus returned the earldom of Kent to

Odo but it wasn’t long before his uncle was plotting to make Rufus’s elder

brother, Robert Curthose, king of England as well as Duke of Normandy. Rufus attacked Tonbridge castle where Odo was

based. When the castle fell Odo fled to

Robert in Pevensey. The plan was that

Robert Curthose’s fleet would arrive there, just as William the Conqueror’s had

done in 1066. Instead, Pevensey fell to

William after a siege that lasted six weeks. William Rufus pardoned his uncle

Robert and reinstated him to his titles and lands. He died in Normandy in 1095.

Nigel

Fossard was

not a tenant in chief, but held lands from the Earl of Mortain.

He was one of the principal under-tenants of Count Robert, of whom he held some

91 manors (much of the Mortain lands). Hexthorpe was

his chief holding in Yorkshire. It appears highly probable that on the

forfeiture of Count Robert’s estates, Nigel was advanced to the dignity of a tenant

in capite, that is, to hold his lands directly

from the King, and not through a second person as he had previously done.

Fossard thus came to possess the lands formerly

held by Tostig, including the feudal superiority of Doncaster. Fossard had a house at Doncaster, but his principal

residence was at Mulgrave Castle. His descendants held Doncaster until the

reign of Henry VI, though not directly through the male line after William Fossard.

He appears to

have been a generous man. Included in his gifts to the Abbot and Convent of St

Mary, York, was the gift of the church of Doncaster and neighbourhood. He was

succeeded by his son Adam, who founded the priory of Hode (Hood Grange,

Yorkshire).

Robert

Fossard,

who succeeded him paid a fine of 500 marks to the King to repossess the

Lordship of Doncaster, “which he had parted to the King to hold in demesne

for twenty years”. The reason for the surrender to the King and the high

price for the repossession is not apparent. It has been suggested that Robert

had not paid the whole of the fee due to the King on his succeeding to the

patrimonial inheritance, hence the lease and release; but it was not unlikely

that it was a transaction to enable the King to raise some needed cash.

William

Fossard,

his son and heir, succeeded him. He was the last of the Fossards

in the male line. He was one of the northern barons who fought against the

Scots in the Battle of the Standard. In 1142 he was with Stephen’s forces

against the Empress Maude at the Battle of Lincoln and was taken prisoner. On

the collection of scuttage, a tax paid in lieu of

Military service etc, by those who held land by Knights service, he paid £12, a

fairly large sum in those days, at other times he paid £21 and a further sum of

£31 10s, the last amount was levied upon him because he was not in the Irish

Wars. He was especially exempted from contributing for the redemption of King

Richard I. He left a daughter, Joan, who was married to Robert de Turnham.

Robert

de Turnham had two sons,

Robert and Stephen. It was Robert the younger

who married Joan Fossard.

He was a crusader, and was reputed to be a powerful and valiant man. Some

historians say that he died on an expedition to the Holy Land but there is no

evidence for this statement. He appeared to be with the King in the Holy Land,

and was entrusted to bring the King’s harness back to England. For the services

on that journey he was discharged from the payment of scuttage

levied for the Kings ransom. Being in the King’s confidence he probably exerted

himself in obtaining from the king, a charter confirming to the burgesses of

Doncaster whatever ancient privileges they then possessed. He obtained a grant

of two more days to be added to the fair that had anciently been kept at his

manor of Doncaster in County Ebor, upon the eve and day of St James the

apostle. At his death in 1199, the yearly value of the lands held by him in

right of Joan, his wife, was entered at £411. 9s. 2d.

He left a

daughter, Isabell, who became a ward of the

King. She married Peter de Mauley, a Poictevin.

A long line of Peter de Mauleys, claiming descent from Nigel Fossard, successively held the Lordship of Doncaster. The

first of these is said to have committed an infamous crime at the instigation

of King John. On the death of King Richard, his brother John, “knowing that

he could not succeed him by reason that Arthur, son of Geoffry of Brittany, was

alive, got Arthur into his power and implored Peter de Mauley, his esquire, to

murder him and in reward gave him the heir of the barony of Mulgref”.

Some doubts have arisen as to the truthfulness of this statement. If Mauley

really did commit the act at the instigation of John, and was led to expect

that he would receive the King’s ward to marry with the free enjoyment of her

lands, he was decieved; for Peter de Mauley paid a

fine of 7000 marks “for entrance to the inheritance of the daughter of

Robert de Turnham”. He gave the body of his wife to be buried at the Abbey

of Meux, Holderness, endowing the Abbey with a rent of Sixty shillings per

year. He died before 1241. In 1247 the King took the homage of his heir, Peter,

for all his fathers lands. Some six years later this

Peter de Mauley obtained a charter of Free Warren in his demesne lands, which

included Doncaster. He died in 1279.

The next Peter de Mauley paid £100 relief for all lands

held of the King in capite of the inheritance of

William Fossard. From a document from 1279 we catch a

glimpse of a part of the Mauley holdings for which the above relief was paid.

He married Joan, the daughter of Peter Brus of Skelton.

There followed

another six Peter de Mauleys (see South Yorkshire, the History and Topography of the

Deanery of Doncaster in the Diocese and County of York by Rev Joseph Hunter,

1828, page 12 to 13 for a fuller description).

Alongside the

Mauleys, other descendants of Nigel Fossard had

interests in Doncaster.

There was

significant building of monasteries and parish churches during this period.

The

building of churches was attractive since this allowed the lords to extract

tithes from distant churches to which it had been paid and settle it on

churches of their choosing, perhaps closer to their own residence. During this

period churches were built at places including Coningsborough, Campsall, and

Doncaster. Joseph Hunter lists 60 places where Churches were built.

Most

of these churches had one officiating minister at their foundation, the persona

or rector. The churches were often placed under the patronage of

monastic institutions.

The

church at Doncaster was distinguished from others by being given the title of

dean.

Certain

of these churches were parish churches in form, but were also referred to as

chapels, which meant that they were given rights of baptism, nuptial

benediction and of sepulture, but were not able to

participate in tithes from the lands around them. These churches included St

Mary Magdalene at Doncaster and the chapel at Loversall.

At

Doncaster there was a college, for the residence of chantry priests, so that

they need not mingle with the public. This was built near the parish church and

the priests officiated in the parish church and at St Mary Magdalene chapel,

living a collegiate life as it was felt inappropriate for their social

character to mix too freely with the people of the town.

(South

Yorkshire, the History and Topography of the Deanery of Doncaster in the

Diocese and County of York by Rev Joseph Hunter, 1828, page xvi to xx, 11, Doncaster

History, The Lords of Doncaster).

A

borough was created at Doncaster after the soke had been granted directly to

Nigel Fossard on the banishment of William’s half

brother Robert, Count of Mortain. [Still to

check - was this the temporary banishment after his rebellion against William

II and then remained permanent here?].

The

Roman fort at Danum was superceded by an Anglo Saxon burh

(fortified settlement) before a Norman castle was built. The castle has long

disappeared. The motte of the Norman Castle has been located to be under the

east end of St George’s Minster.

Early in the reign of William II

(William Rufus), Nigel Fossard was amongst the

benefactors who founded the abbey of St Mary in York.

Fossard gave the church of Doncaster to the new abbey

as well as lands in the area.

1136

Doncaster was

ceded to Scotland in the Treaty of Durham and never formally returned to

England. The first treaty

of Durham was a peace treaty concluded between kings Stephen of England and

David I of Scotland on 5 February 1136. In January 1136, during the first

months of the reign of Stephen, David I crossed the border and reached Durham.

He took Carlisle, Wark, Alnwick, Norham and

Newcastle-upon-Tyne. On 5 February 1136, Stephen reached Durham with an

imposing troop of Flemish mercenaries, and the Scottish king was obliged to

negotiate. Stephen recovered Wark, Alnwick, Norham

and Newcastle, and let David I retain Carlisle and a great part of Cumberland

and Lancashire, alongside Doncaster.

In February

1136, Henry, prince of Scotland, did homage to Stephen for Doncaster and the

honour of Huntingdon.

Tickhill

acquired markets and fairs long before the system of royal licences started in

the late twelfth century. The town grew rapidly.

1157

But the story

of Doncaster is not only told through the history of the noble families. The

burgesses and inhabitants of the town followed the 40 soke men referred to in

Domesday book, and came to enjoy increasing privileges. The earliest record

might be the Pipe Roll of 3d Henry II,

when Adam Fitz Swein was discharged of £60 due for

the rent of Doncaster. Adam Fitz Swein owed £45 of

rent for Doncaster and £15 had been paid for a quarter part of the year. It

appears therefore that the burgesses held Doncaster from the King for a rent of

£60 per annum and an individual was appointed to account for it.

In 1157

Malcolm, King of Scotland, did homage to Henry II for Cumberland, in Doncaster.

1163

Malcolm of

Scotland was again in Doncaster to do homage and fell dangerously ill there.

1191

In Richard I’s

absence on crusade, John seized the castles of Tickhill and Nottingham.

1194

Richard I had

given the town recognition by bestowing a town

charter. It seems that Richard I placed the right of the burgesses at

Doncaster onto a formal footing by providing a royal charter. The charter was

the first article of the Miller’s Appendix and declared that the King had

granted to the burgesses of Doncaster the soke and town of Doncaster to hold by

the ancient rent and 25 marks of silver more to be paid into the exchequer with

all liberties and free customs. The burgesses paid 50 marks to the king for the

charter. It seems that the burgesses must have gained something mor tangible

from the charter, but it is not clear exactly what. However it appears that

amongst the privileges gained, was the right to hold a fair and market held at

St James’ Tide.

(South Yorkshire, the History and Topography of the

Deanery of Doncaster in the Diocese and County of York by Rev Joseph Hunter,

1828, page 10)

Doncaster had

by this time become the dominant settlement in the region. It’s position on the

great road from London to York, and en

route to the Scottish border, made it a place where strangers rested.

The area around

Doncaster appears to have enjoyed relative peace after Norman rule had been

established. Coningsborough never endured a siege and Pontefract Castle, which

was seen as the key of the North, was not attacked until the English Civil War.

In the time of

the Fossards, Doncaster consisted of a few public

buildings of stone, amidst a town of wooden houses. The original public

building was the castle which stood at the location of the present Doncaster

Minster. Leland (1503 to 1552) recorded: The Church stands in the very area

where ons the castelle of

the towne stoode, long sins

clene decayed. The dikes partely

yet be scene, and the foundation of partte of the waulles. The Wall of the Castle is mentioned in a grant

of 1416.

Beside the

parish church was the church or chapel of St Mary Magdalene, which was founded

before the year of King John. There were hospitals of St James (with a chapel

annexed) and St Nicholas (which had lands at Loversall),

which would have provided some relief to the poor and the aged. There were also

public mills on the Don. This was the town as it must have appeared before the

great fire of 1204.

There was a

chapel of our lady at the bridge.

(South Yorkshire, the History and Topography of the

Deanery of Doncaster in the Diocese and County of York by Rev Joseph Hunter,

1828, page 11, 19)

1199

When John

seized the throne, he acquired Tickhill and during his reign he spent over £300

strengthening its defences.

There was a disastrous fire in 1204

which appears to have completely destroyed the town, from which the town slowly

recovered.

The revival of the town after the fire

is first recorded in a warrant of King John addressed to the bailiffs of Peter

de Mauley, who had married Isabella de Turnham, their heiress of Doncaster. The

bailiff was instructed to enclose the town along the course of a ditch and to

fortify the bridge. This appears in the Close Rolls. It appears therefore that Doncaster

was protected by a ditch and possibly a mound and Leland later indicates that

Doncaster did not become a walled town. Doncaster continued to comprise mainly

wooden buildings at least until the time of Henry VIII. Only the public

buildings were of stone.

1215

By 1215 the whole town was enclosed by

an earthen rampart and ditch, which was filled with water from the Cheswold, the original course of the Don. By this time it

had four substantial stone gates as entrances at St Mary’s Bridge, St Sepulchre

Gate, Hall Gate and Sun Bar.

1248

In 1248, a charter was granted for

Doncaster Market to be held in the area surrounding the Church of St Mary

Magdalene, which had been built in Norman times.

The burgesses grew their wealth and

significance during this period. A principal class of merchants appeared and

the Don was gradually made navigable. Many merchants marks were made on the old

parish church and the richness of its development evidences the increasing

opulence of the merchant class.

Doncaster became the most prosperous

medieval town in South Yorkshire.

Urban expansion in the early medieval

period was accompanied by an increase in the size of the rural population and

colonisation of new lands.

The

Survey of the County of York by John de Kirkby known as Kirkby’s

Inquest,

(the Nomina Villarum for

Yorkshire) was taken in the fifth reign of Edward I, with some reference to

Doncaster and its vicinity on pages 281 to 282.

1285

Early

during the reign of Edward II there was a feud between the Earl of Warren at

Coningsborough and the Earl of Lancaster at Pontefract. The Earl of Lancaster

called his followers together at Doncaster and attacked Tickhill Castle, but

the enterprise came to nothing (South Yorkshire,

the History and Topography of the Deanery of Doncaster in the Diocese and

County of York by Rev Joseph Hunter, 1828, page xxii, 10).

1290

In

the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, a new religious order of friars

arrived in Doncaster, who were itinerant and applied themselves to instruction

and religious edification. There was a house of Augustinian friars at Tickhill

and houses if Franciscans and Carmelites at Doncaster. The friars achieved

literary knowledge and were centres of literature in the middle ages. Therefore

to the public buildings there were added the houses of the Carmelite and

Franciscan friars.

The

establishment of the two societies of friars and their educational achievements

further enhanced the growth of the town as a place of significance.

The Franciscans or Grey Frairs

He Franciscans in England were divided

into seven wards or custodies. The Custody of York included Doncaster.

A History of the County of

York: Volume 3. Originally published by Victoria County History, London, 1974: THE GREY FRIARS OF DONCASTER

The Friars Minors established

themselves at this town on an island formed by the rivers Cheswold

and Don, at the bottom of French or Francis gate, at the north end of the

bridge known as the Friars' Bridge, some time

in the 13th century. Nicholas IV, 1 September 1290, granted an indulgence

to those who visited their church, which was of the invocation of St. Francis.

Archbishop Romanus in 1291 enjoined the friars of this house to preach the

Crusade at Doncaster, Blyth (Notts.), and Retford.

In 1299 Edward I gave the friars 10s.

through Friar Edmund de Norbury, on the occasion of his visit to Doncaster, 12

November: in January 1299-1300 he gave them 20s. for two days' food and 6s. 8d.

for damages to their house when he was at Doncaster, by the hand of Friar de Portynden. On 8 June 1300 his son Edward gave them 10s.,

and the king in January 1300-1 gave them 10s. for the exequies

of Joan, nurse of Thomas of Brotherton. The friars at this time numbered

thirty.

In 1316 Sir Peter de Mauley, lord of

the town of Doncaster, granted the Friars Minors a plot of land, 14 p. by 6

p., adjacent to their dwelling-place.

In 1332 Thomas de Saundeby,

the warden, and Friars Nicholas de Dighton, Thomas de Moubray, William de

Halton, and John de Brynsale, were sued by John de Malghum for having seized and imprisoned him. In 1335 the

king pardoned them for acquiring in mortmain without licence in the time of

former kings divers plots in Doncaster, now inclosed

with a wall and dyke, whereon they had built a church and houses. Between 1328

and 1337 the number of the friars varied between eighteen and twenty-seven, as

is proved by the royal alms granted to them by the hand of Friars John de Bilton, Nicholas de Wermersworth,

and others.

Sir Hugh de Hastings, kt., in 1347 left

the friars 100s., 20 quarters of corn and 10 quarters of barley. A friar of

this house, Hugh de Warmesby, was authorized in 1348

to act as confessor to Lady Margery de Hastings, Sir Hugh's widow, and her

family. Her son Hugh was buried in the church of St. Francis at Doncaster,

1367. Another Sir Hugh Hastings in 1482 left a serge

of wax to be burned here in honour of the Holy Rood, and a quarter of wheat

yearly for three years.

Among the bequests may be mentioned that

of Roger de Bangwell, rector of Dronfield, of 20s. to

the convent and 12d. to each friar in 1366. Thomas Lord Furnival of Sheffield,

1333, and Sir Peter de Mauley, 1381, were buried in the church; the latter left

his best beast of burden as mortuary and 100s, to the convent. …

…Friar Thomas Kirkham was admitted D.D.

of Oxford in July 1527, his composition being reduced to £4 'because he is very

poor'; in November he was dispensed from the greater part of his necessary

regency because he was warden of the Grey Friars of Doncaster and could not

continually reside in Oxford. Thomas Strey, a lawyer of Doncaster, left 20

marks to the convent in 1530 and 26s. 8d. to buy the warden a coat.

… The house was quietly surrendered 20

November 1538 by the warden and nine friars, three of them novices, to Sir

George Lawson and his fellows, who were 'thankfully received.' …

A manuscript of the chronicle of Martin

of Troppau formerly belonging to this friary was in the possession of Ralph

Thoresby in 1712.

(See also South Yorkshire, the History and Topography of the

Deanery of Doncaster in the Diocese and County of York by Rev Joseph Hunter,

1828, page 17).

1307

During the 14th century, large numbers

of friars arrived in Doncaster who were known for their religious enthusiasm

and preaching.

In 1307 the Franciscan friars

(Greyfriars) arrived, as did Carmelites (Whitefriars) in the mid-14th century.

1316

Nomina Villarum

(“Names of Towns”) was a survey carried out in 1316 and contains a list of all

cities, boroughs and townships in England and the Lords of them.

In these Inquisitions Nonarum during the reign of Edward III, eight merchants

were said to be residing in Doncaster, which was more than in other similar

towns. At Tickhill there were seven merchants so this was an are of commercial

significance. There is rare evidence of summons being sent to Doncaster and

Tickhill directing them to send burgesses to Parliament. (South Yorkshire, the History and Topography of the

Deanery of Doncaster in the Diocese and County of York by Rev Joseph Hunter,

1828, page xxi).

1321

In late 1321 Thomas, Earl of Lancaster,

the great baron at Pontefract, opposed royal authority and called on many

barons to meet at Doncaster. On 12 November 1321 the King forbade this meeting

on penalty of forfeiture of their lands. An open rebellion ensued, joined by

Lord Mowbray, On 18 March 1322 the King

was in Doncaster and the Battle

of Boroughbridge was fought on 17 March 1322 when the rebels were defeated

and Thomas was executed at Pontefract (South

Yorkshire, the History and Topography of the Deanery of Doncaster in the

Diocese and County of York by Rev Joseph Hunter, 1828, page 15).

1334

In 1334 the inhabitants of Doncaster

contributed £17 in taxes, compared with £12 10s 0d in Tickhill and £7 3s 4d

from Sheffield. Doncaster owed its wealth mainly to its weekly markets and its

annual fairs, which had become nationally famous. There was a huge market place

in the south east corner of the medieval town, and as was common, it was an

extension of the churchyard.

Doncaster now had two churches – St

George’s still within the bounds of the castle, and St Mary Magdalene, which

stood at the market place. It is now generally accepted that St Mary Magdalene

was the original parish church. However as the castle fell into disuse, and

pressure for space at the market had increased, the old church was abandoned in

favour of St George’s. St Mary Magdalene was reduced to the status of a chapel,

and later a chantry. After the Reformation it became a town hall and school.

1360

The Carmelites or White Friars

A

History of the County of York: Volume 3. Originally published by Victoria

County History, London, 1974: THE HOUSE OF WHITE FRIARS, DONCASTER

Founding in 1350

The Carmelite friary—' a right goodly

house in the middle of the town ' (Leland, I tin. i, 36. See F. R. Fairbank, 'The Carmelites of Doncaster,'

in Yorks. Arch. Journ. xiii, 262-70) —was

founded in 1350 by John son of Henry Nicbrothere of Eyum with Maud his wife and Richard Euwere

of Doncaster, who gave the friars a messuage and 6 acres of land. The priors of

the order asked permission of the Archbishop of York to have the place

consecrated in 1351. The earliest bequest to them recorded was made by

William Nelson of Appleby, vicar of Doncaster, in 1360. (Yorks. Arch. Journ. xiii, 191)

In 1366 Roger de Bangwell, formerly rector of

Dronfield, made his will in the house of these friars, in whose church he

wished to be buried; … A provincial chapter was held at this friary in 1376. (Tanner, Bibliotheca, 562) The friars in 1397

received the royal pardon, on paying 20s., for acquiring without licence

several small plots, worth 12s. 6d. a year, 'for the enlargement of the

entrance and exit of their church. (a Pat. 20 Ric.

II, pt. ii, m. 22) Two friars of the house, John Slaydburn

and John Belton, were appointed papal chaplains in 1398 and 1402. (Cal of Papal Letters, iv, 305, 315).

John of Gaunt was regarded as one of the

founders, and his son Henry of Bolingbroke on his journey from Ravenspur in July 1399 lodged at the friary, (Hardyn, Chron. (ed. Ellis), 353) where also Edward IV was entertained in 1470, Henry VII in

1486, and the Princess Margaret Tudor in 1503. Edward IV in 1472 conferred the

privileges of a corporation on the convent, 'which is of the foundation of the

king's progenitors and of the king's patronage,' and licensed the friars to

acquire lands to the yearly value of £20. At the beginning of the 16th century

the Earl of Northumberland claimed the title of founder of the house.

Writing

Several members of the house attained some

distinction as writers. Such were John Marrey,

who died in 1407, John Colley who flourished c. 1440, John Sutton, provincial

prior 1468, and Henry Parker, who got into trouble by preaching on the poverty

of Christ and His apostles and attacking the secular clergy at Paul's Cross in

1464; he is probably the author of the dialogue entitled Dives et Pauper which

was printed both by Pynson and by Wynkyn

de Worde at the end of the 15th century. John Breknoke,

keeper of the Dragon Inn at Doncaster, left the friars some books in 1505.

The House of the Carmelites was a

college of learned men. These included John Marr who later went to Oxford; John

Colley; Henry Parker and John Sutton.

Sixteenth century

… On 15 July 1524 William Nicholson of Townsburgh attempted to cross the Don with an iron-bound

wain in which were Robert Leche and his wife and their two children; being

overwhelmed by the stream they called on our Lady of Doncaster and by her help

came safely ashore; they came to the White Friars and returned thanks on St.

Mary Magdalen's Day, when 'this gracious miracle was rung and sung in the

presence of 300 people and more.' (Yorks. Arch. Journ. xiii, 558; Hist. MSS. Com. xiv, App. iv, 1)

On the eve of the Dissolution the house

was divided against itself. The famous John Bale, about 1530, being then a

friar at Doncaster, and perhaps prior, taught one William Broman 'that Christ

would dwell in no church made of lime and stone by man's hands, but only in

heaven above and in man's heart on earth.'

In the Pilgrimage of Grace, though the

lords used the White Friars as their head quarters

while negotiating with Robert Aske at Doncaster, the prior, Lawrence Coke,

supported the rebellion. He was imprisoned in the Tower and in Newgate,

condemned by Act of Attainder a few days before Cromwell's fall, but pardoned

on 2 October 1540; it is not clear whether the pardon was issued in time to

save him from execution.

The house was surrendered by Edward Stubbis, the prior, and seven friars, on 13 November 1538

to Hugh Wyrrall and Tristram Teshe, who 'made a book

of the property' and notified to Cromwell that the tenements in Doncaster were

in some decay, and that the image of our Lady had already been taken away by

the archbishop's order. The plate sent to the royal jewel house was

considerable; 25 oz. of gilt plate, 109½ oz. parcel gilt, and 48½ oz. white

plate. The net profit from the sale of the goods seems to have been £21 18s.

4d. The site with dovecot and other houses, a garden and orchard all surrounded

by a stone wall and containing 2½ acres, was let to Wyrrall

for 10s. a year. The tenements in Doncaster included an inn called 'Le Lyon' in

Hallgate, already let by the prior to Alan Malster for forty-one years at 40s. a year in 18 August

1538, a messuage in Selpulchre Gate similarly leased

on 2 September 1538 to Emmota Parsonson for 12s., and

various tenements, shops, and cottages, the whole property bringing in £10 17s.

4d. a year.

Towards the end

of the fourteenth century, Edmund Duke of York attempted to raise Stainford (Stainforth), further

down the Don into commercial importance.

1398

Henry

Bolingbroke (later Henry IV) swore at Doncaster that he came only to recover

lands of inheritance as Duke of Lancaster, during his dispute with Richard II.

Bolingbroke landed at Ravenspurn with 100 men at

arms. They reached Pickering Castle and stayed

there for two days before marching south. He then marched via Pontefract to

Doncaster, where he lodged with the Carmelites. By this time it is said that he

commanded 30,000 men. While there he took the oath, which he was later said to have

broken. By 13 October 1399, having imprisoned Richard II (who died in prison

probably of starvation) Henry was crowned Henry IV.

(South Yorkshire, the History and Topography of the

Deanery of Doncaster in the Diocese and County of York by Rev Joseph Hunter,

1828, page 15).

1450

Edward IV

granted a further charter to the burgesses recognising their rights and

privileges. They were empowered to choose a mayor annually and two sergeants at

mace, to have a common seal and to hear pleas of trespass, debt and other

matters in the Guild Hall.

1455

to 1487

During the War

of the Roses, Doncaster was a place through which the contending armies passed

and repassed.

In 1470 there

was an attempt to seize the throne from King Edward after the Battle of

Stamford, when the King came to Doncaster.

1536

The dissolution

of the monasteries. The consequence was the transfer of significant wealth and

power from ecclesiastical to private lay proprietors of manors, lands and

estates. Part of these lands fell directly into control of previous owners of

feudal interests, but often the new owners were new people who would themselves

become founders of considerable families. A new order of gentry replaced many

of the old feudal interests. The depreciation of money also had the effect of

favouring a new guard. Joseph Hunter lists the new gentry families. They

included Thomas Wray of Adwick in the Liberty of Tickhill and William Fletcher

of Campsall.

The churches

were generally respected. The chapel of St Mary Magdeleine in Doncaster fell at

this time. The fall of the Carmelite house at Doncaster likely diffused

significant literary accomplishment.

The Pilgrimage of Grace was a

backlash to the Reformation and the insurgents took Pontefract Castle and

gathered in significant numbers at Scawsby Lees near

Doncaster. The sudden rising of the Don prevented a bloody engagement.

(South Yorkshire, the History and Topography of the

Deanery of Doncaster in the Diocese and County of York by Rev Joseph Hunter,

1828, page xxiii, 16).

But the Pilgrimage

of Grace was already afoot in West Yorkshire, and the movement soon

spread into the northern part of Lancashire. In the course of October the

commons of Cartmel restored the canons to the priory. The prior, however, more

prudent or less staunch than his brethren, stole away and joined the king's forces

at Preston. This was before he heard of the general pardon and promise of a

northern Parliament granted to the rebels at Doncaster on 27 October. (A History

of the County of Lancaster: Volume 2. Originally published by Victoria County

History, London, 1908).

The royal stronghold at Tickhill

prevented the rebels from marching south and the revolt petered out after an

uneasy truce was signed at Doncaster.

1563

Eleven people died on the plague in 1563

and Doncaster seems to have suffered badly from plague in 1582 and 1583. There

appears to have been a Pesthouse to which people infected were interred.

1569

There was a rebellion by the Earls of

Westmoreland and Northumberland and Doncaster was secured by Lord Darcy.

1582

The Doncaster

Chronicle provides some record of events, for instance that there were

30 marriages at the church in Doncaster from September 1582 to September 1583.

(See also South Yorkshire, the History and Topography of the

Deanery of Doncaster in the Diocese and County of York by Rev Joseph Hunter,

1828, page 21).

1588

During the

period of threat from the Spanish Armada, the Earl of Huntingdon was at

Doncaster raising and training soldiers.

Links, texts and

books

South Yorkshire, the

History and Topography of the Deanery of Doncaster in the Diocese and County of

York by Rev Joseph Hunter, 1828.

The Making of South

Yorkshire, David Hey, 1979

A History of

Yorkshire, “County of the Broad Acres”, 2005, David Hey

A

History of Yorkshire, F B Singleton and S Rawnsley, 1988

A History of

Yorkshire, Michael Pocock, 1978