The first historical reference to

Farndale

Rievaulx

Chartulary, 1154

Subsequent

references to Farndale in the twelfth and thirteenth century

Farndale, where Edmund

the Hermit used to live

FAR00002

|

Return to the Home

Page of the Farndale Family Website |

The story of one

family’s journey through two thousand years of British History |

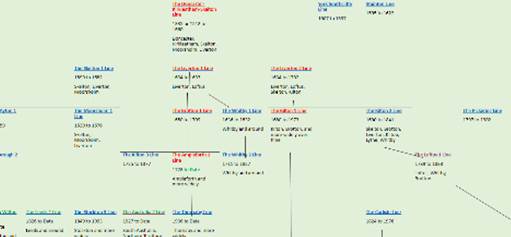

The 83 family lines

into which the family is divided. Meet the whole family and how the wider

family is related |

Members of the

historical family ordered by date of birth |

Links to other pages

with historical research and related material |

The story of the

Bakers of Highfields, the Chapmans, and other related families |

Dates are in red.

Hyperlinks to other pages are in dark blue.

Headlines are in brown.

References and citations are in turquoise.

Context and local history are in purple.

This page is divided into the following sections:

·

The First Reference to Farndale in the Rievaulx Chartulary

·

Monastic grants

·

Edmund the Hermit

·

The Fern

·

Subsequent references to Farndale in the twelfth and thirteenth

century

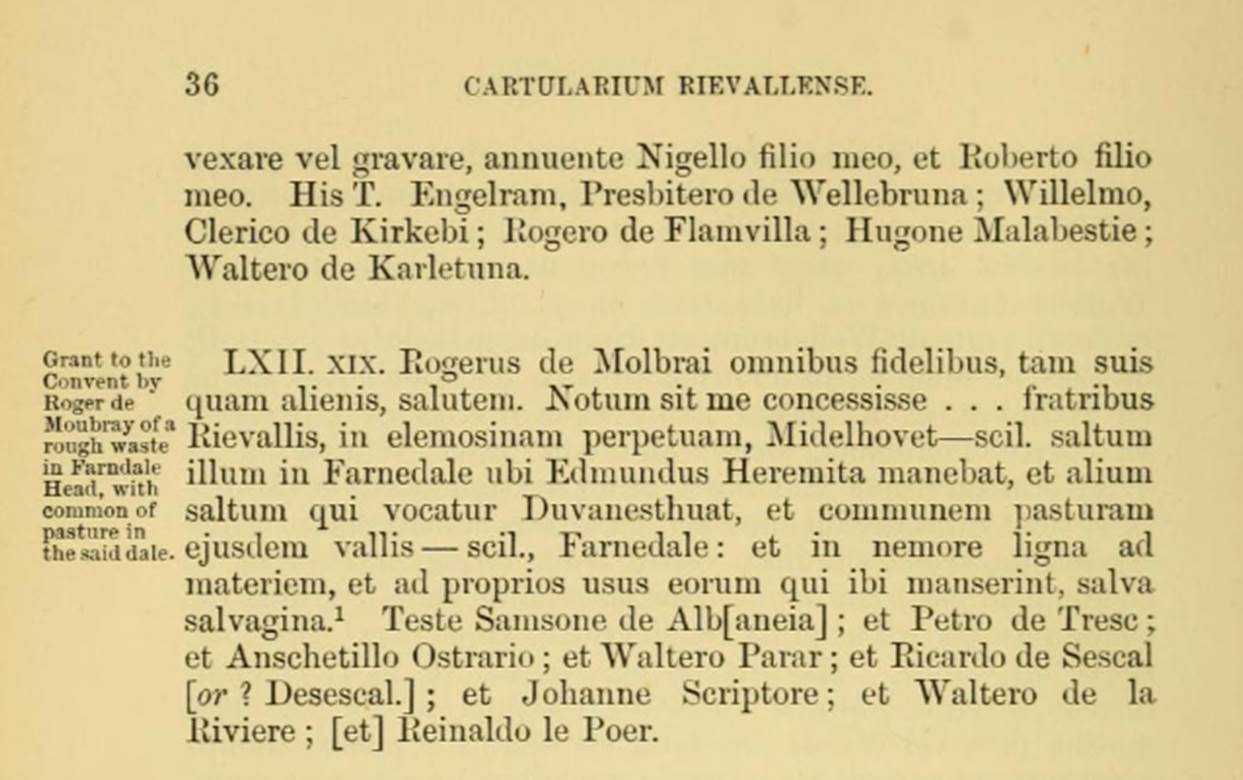

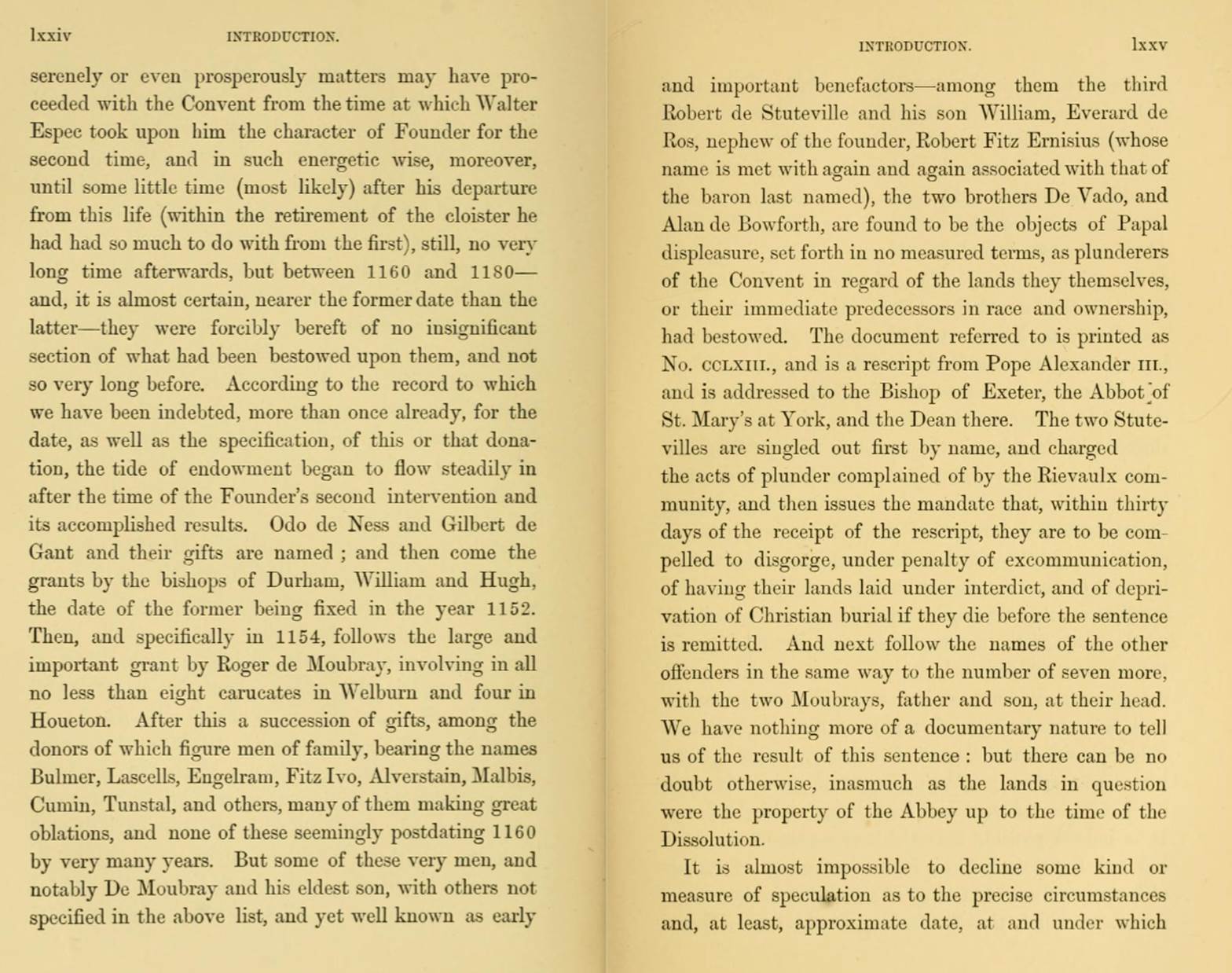

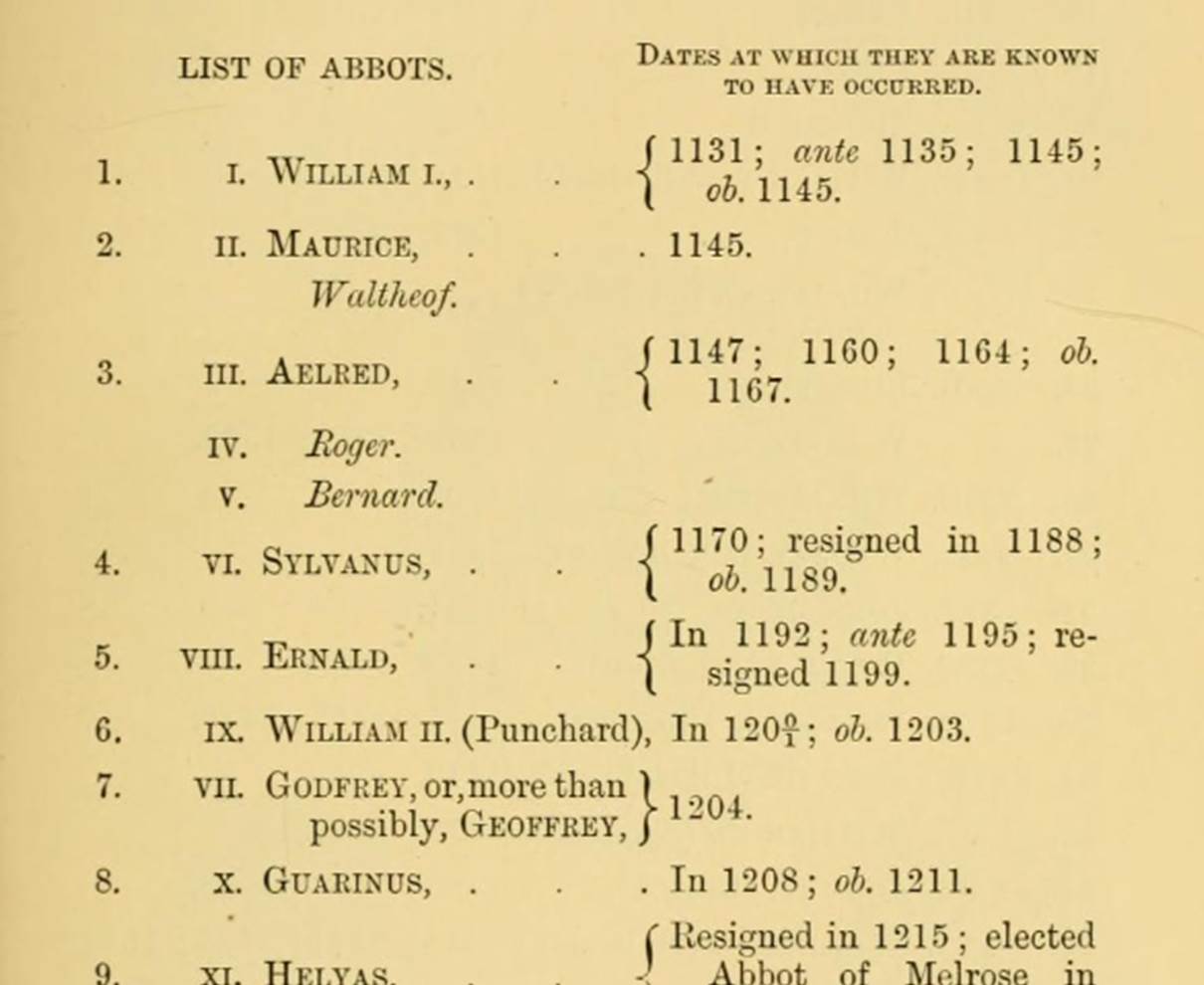

The First reference to

Farndale in the Rievaulx Chartulary

Gundreda, on behalf of

her guardian, Roger

de Mowbray,

gave land to Rievaulx abbey land which

included a place called Midelhovet, where Edmund the Hermit used to

dwell, and another called Duvanesthuat,

together with the common pasture within the valley of Farndale.

The name Farndale,

first occurs in history in the Rievaulx

Abbey Chartulary in a Charter granted by Roger de

Mowbray to

the Abbot and the monks of Rievaulx Abbey in 1154. By it Roger bestowed upon

the Monastery, ‘….Midelhovet, that clearing in Farndale where the hermit

Edmund used to dwell; and another clearing which is called ‘Duvanesthuat’

and common of pasture in the same valley of Farndale….’

Rievaulx

Abbey

Rievaulx and Farndale

Midelhovet is probably

Middle Head at the head of Farndale near the source of the river Dove, 3.5

miles NW of Farndale East.

Duvanesthuat could be Dowthwait in Farndale, but is more likely to be Duffin

Stone, grid 646987 on the west side of High Farndale.

Middle Head and

Duffin Stone at the northern end of Farndale

Middle Head in

2021

Gundreda, wife of Nigel

de Albaneius, greetings to all the sons of St. Ecclesiff. Know that I have given and … confirmed, with the

consent of my son, Eogeri de Moubrai,

God and St. Marise Eievallis and the brothers there.

. . for the soul of my husband Nigel de Albaneius,

and for the safety of the soul of my son, Roger de Molbrai,

and of his wife, and of their children, and for the soul of my father and

mother, and of all my ancestors, whatever I had in my possession of cultivated

land in Skipenum, and, where the cultivated land

falls towards the north, whatever is in my fief and that of my son, Roger de Moubrai, in the forest and the plain, and the pastures and

the wastins, according to the divisions between Wellebruna and Wimbeltun, and as

divided from Wellebruna they tend to Thurkilesti, and so towards Cliveland,

namely Locum and Locumeslehit, and Wibbehahge and Langeran, and Brannesdala, and Middelhoved,

as they are divided between Wellebruna and Faddemor, and so towards Cliveland.

Middlehoved is Middle Head

at the north end of Farndale. See above.

Roger of Molbrai, to all the faithful, both his own and strangers.

Let it be known that I have granted . . to the Rievallis

brothers, in perpetual alms, Midelhovet - scil. that

meadow in Farnedale where Edmund the Hermit dwelt,

and another meadow called Duvanesthuat, and the

common pasture of the same valley - scil., Farnedale: and in the forest wood for material, and for the

own uses of those who remained there, save the salvage.

Witness Samson de

Alb[aneia]; and Peter of Tresc;

and Anschetillo Ostrario;

and Walter Parar; and Eicardo de Sescal

[or ? Desescal.]; and John the Scribe; and Walter de la Eiviere;

[and] Eiinaldo le Poer.

In the same town

I gave them two oxen in full land, with a stable, and other appurtenances and

appurtenances, as I had granted them in Mideltune,

and they shall have for the shepherds of their animals one lodge of length xv

feet and of the same width. And it must be known that this logia emanates in

the upper part from Eskletes, and that the aforesaid

brother, with two servants, will attend the aforesaid house of horses, as

prescribed, without a larger family and without occasion. But if, in these

pastures, the cattle have passed their set goals, without having been guarded,

my men will turn them away without trouble.

Monastic Grants

The Yorkshire Archaeological Journal, Vol 40, Page 481. The

Monastic Settlement of North East Yorkshire:

… After the

foundation, sometimes a very large grant as at Guisborough and Whitby, or a

very niggardly ones as at Rievaulx, the accumulation of lands and rights was

rapid, alarmingly so. At Rievaulx, for example, the greater parts

of the lands were acquired and a very large number of granges established by

the end of the twelfth century. Even by 1170 the monks had required all Bilsdale, Pickering Marshes, parts of Farndale and

Bransdale, the Vills of Griff, Tileson, Stainton,

Welburn, Hoveton, and the lands of Hummanby, Crosby, Morton, Wedbury,

Allerston, Heslerton, Folkton, Willerby, Reighton...

Some donors had apparently not bargained for such a rapid increase in monastic

possessions. It came as a shock to find that the monks were not “all that was

simple and submissive; No greed, no self-interest …” The result was that men

like Roger de Mowbray, Robert de Stuteville, Everard de Ros and other great

Lords, formerly great donors and foundations, began unsuccessfully, to evict

the monks from certain lands, but monastic expansion continued...

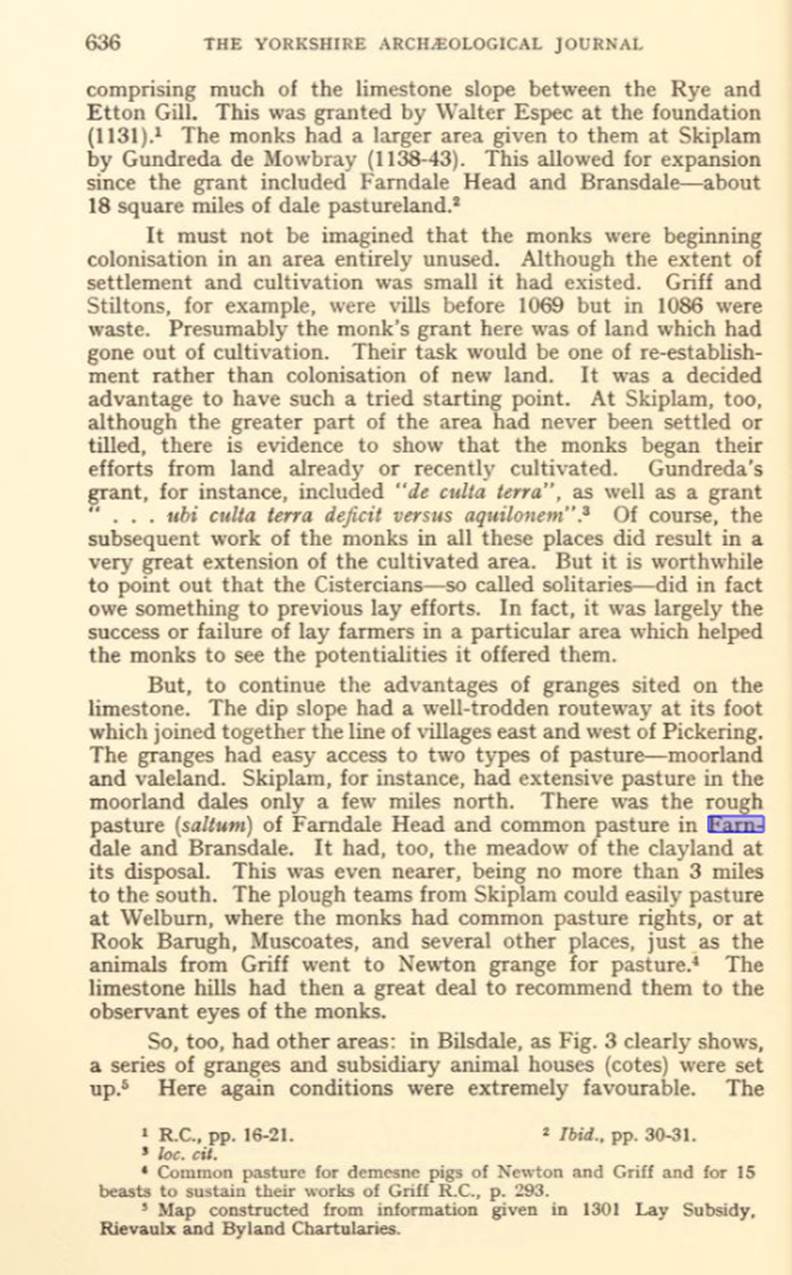

The Yorkshire Archaeological Journal, Vol 40, Page 636:

… The monks had a

larger area given to them at Skiplam by Gundreda de Mowbray (1138 to 1143). This

allowed for expansion since the grant included Farndale Head and Bransdale,

about 18 square miles of dale pasture land.

It must not be

imagined that the monks were beginning colonisation in an area entirely unused. Although the extent

of settlement and cultivation was small it had existed. Griff and Stiltons, for example, were vills

before 1069 but in 1086 were waste. Presumably the monks grant here was of land

which had gone out of cultivation. Their task would be one of

reestablishment rather than the colonisation of new land. It was a

decided advantage to have such a tried starting point. At Skiplam, too, although the greater part of the area

had never been settled for or tilled, there is evidence to show that the

monks began the efforts from land already or recently cultivated. Gundreda’s grant, for instance cover included

“de culta terra” (“of cultivated land”), as well as a

grant “ubi culta terra deficit versus aquilonem” (“where the cultivated land declines towards the

north”). Of course the subsequent work of the monks in all these places did

result in a very great extension of the cultivated land. But it is

worthwhile to point out that the Cistercians, so-called solitaries, did in fact

owe something to previous lay efforts. In fact, it was largely the success or

failure of lay farmers in a particular area which helped the monks to see the

potentialities it offered them.

…. The granges

had easy access to two types of pasture - moorland and valeland.

Skiplam, for instance, had extensive pasture in the

moorland dales, only a few miles north. There was the rough pasture (saltum) of

Farndale Head and common pasture in Farmdale and

Bransdale. It had, too, the meadow of the clayland at

its disposal. This was even nearer, being no more than three miles to the

south. The plough teams from Skiplam could easily

pasture at Welburn, where the monks had common pasture rights, or at Rook

Barugh, Muscoates, and several other places, just as

the animals from Griff went to Newton grange for pasture. The limestone hills

had then a great deal to recommend them for the observant eyes of the monks.

The Yorkshire Archaeological Journal, Vol 40, Page 636:

Although arable

granges would require access to pasture land this would be more important to

pastoral granges in which movement of animals, sometimes over great distances,

was an economic necessity. Most grants of common pasture to the monasteries

were made early. Rievaulx had common in Welburn (1138 to 1143); Wombleton (1145 to 1152); Farndale (pre 1155), for

example, and sometimes the privilege was purchased, eg

Arden Hesketh (pre 1159) 1 ½ marks,

Morton (1158 to 1160) 1 mark... Some specific grants of sheep pasture were very

large... and undoubtedly induced the monasteries to set up their granges nearby.

The Yorkshire Archaeological Journal, Vol 40, Page 636:

A closer

inspection of the map suggests that some vital changes had occurred by 1301.

This comprised an extension of the settled area. Those areas colonised since

Domesday were mainly of two kinds: in the marshy vale lands and in

the moorland dales. In the latter, Bilsdale,

Farndale, Bransdale and Eskdale were mainly concerned. In the former the

Vale of Pickering especially in its central part was affected, but settlement

on the limestone dip slope to the north had also increased, eg

Skiplam, Carlton.

One outstanding

fact is evident, that the monastic share in the expansion of settlement

after 1086 was very great indeed. In Bilsdale,

for example, Byland and Rievaulx between them had settled almost the whole

of the valley by 1301 while lay settlement was confined to a few vills in the north of the valley, e.g. Raisdale, Broad Fields, Bilsdale,

and these were largely dominated by Rievaulx. In Eskdale too, a whole series of

new settlements had been established by Guisborough Priory at Skelderskew, Wayworth, Dibble

Bridge, Glaisdale... Rosedale was entirely a monastic settlement although the

ironstone in the dale was to attract lay settlers there by the mid 14th century. Bransdale and Farndale had apparently

been colonised by laymen, although even here Rievaulx had twelfth

century pasture rights which presumably led to some form of small settlement.

At any rate, by 1282 lay settlement here was considerable. There were for

instance 90 natives in Farndale and 54 natives and bondsman in Bransdale.

Along the north east fringe of the moors at Stanghow, Scaling, Sandsend ... and

in certain spots deeper in the moors, eg Hartoft,

laymen had played a major part in the expansion of settlement.

Significant as

the monastic colonisation of uninhabited areas was it must be remembered that their

greatest contribution was the development of the already settled areas.

Their granges were often inside vills or on the

outskirts of them. In the north east, the monastic contribution to the revival

of settlement after 1069 was great. The great extent of waste presented them

with an unsurpassed economic opportunity. If so much waste had not existed it

is quite possible that the donations to the monasteries would have been less;

that the chance to secure and enlarge a foothold would have been decreased….

Monasteries were

more than prayer ‘powerhouses’, they were an integral part of local

communities, providers of charity and landlords of urban and rural property.

They often had close interaction with parishes and parish churches.

When the Normans

arrived in Yorkshire in the late eleventh century, the ancient Anglo Saxon

monastic communities had long disappeared. Within three years of the conquest

in 1066 a Benedictine House was established at Selby, followed shortly

afterwards by foundations at Whitby and St Mary, York.

By the 1120s the

monastic fashion switched from the Benedictines to the Rule of St Augustine.

In the 1130s, the

Cistercians arrived, an international movement spreading out from Burgundy in

France.

Thus in a small

area are to be found:

· The great

Benedictine housed of St Maty’s York with landholdings at Lastingham and

Kirkbymoorside.

· The Augustinian

house of Newburgh and the Augustinian priory at Kirkham and Marton

· The Cistercian

abbeys of Rievaulx and Byland

Janet Burton

identified four important trends in the history of these monastic orders over

parishes in the Norman period.

1.

The granting of parish churches to monasteries.

In the 1070s or

1080s, William granted to the Benedictine monks of Whitby, the parish church at

Lastingham. There followed a brief period of Benedictine occupancy of

Lastingham until they moved to York by 1086 where they founded the abbey

dedicated to St Mary. Augustinian canons too became involved with the

development of parishes. However the Cistercians from the 1130s initially

rejected acceptance of parish churches and monastic income, rejecting outside

influence or reliance on the work of others.

So when Roger de

Mowbray offered Abbot Roger of Byland the churches at Thirsk, Kirkbymoorside

and Hovingham, they were rejected, saying Roger had given them quite enough

already.

However by

contrast Walter Espec, an influential noble of Henry I’s court in the north,

granted Kirkham church to the Augustinians and this was accepted and formed the

nucleus of a new foundation. This adoption of a parish into a monastic order

would have impacted on parochial arrangements. This created tensions between

local parishioners and the monastic community as questions arose regarding use

of p[laces of worship and costs of upkeep.

Roger de Mowbray

first settled Cistercian monks at Hood near Sutton Bank in 1138 and this was

almost certainly the place of an existing church, which also became the nucleus

for the monastic community.

In 1142, Roger de

Mowbray moved the Cistercians to Old Byland near Rievaulx.

Over the

following years Roger added further churches to the Augustinian Newburgh’s

portfolio including St Gregory’s Minster at Kirkdale,

described as Welburn.

It is clear that

Roger de Mowbray was engaged in the wholesale transfer of the churches within

his demesne to the monastic order in a systematic way. So the lay founders must

have seen advantage in the transfer of churches into the hands of the religious

orders.

From the mid

eleventh century, there was an increased movement, promoted by the pope, to

minimise lay intervention. The pope sought to reduce his influence from

emperors and kings and at parish level there was an attempt to limit secular

intervention in the church. The Council of Westminster in 1102 had required

monks only to accept churches from bishops, in order to reduce the influence of

lay people. This came with a growing recognition of limitations of rights of

the laity in parish churches.

2.

The influence over parish churches through patronage.

Parish churches

had a pastoral (the cure of souls) and temporal (material property) aspect. A

monastery receiving the grant of a parish church would expect to exercise a

right of patronage and the choice of the bishop, with influence in the

ecclesiastical affairs of the community.

The grant of a

parish church might bring financial award through a pension or as a general

means of income.

When Henry de

Neville granted the church of Sheriff

Hutton to St Mary’s York, he provided for the parson of the church to make

payment of a yearly sum of 20 marks (£13 6s 8d), providing a source of revenue

for the monastic house.

3.

The involvement of monastic houses in pastoral care through parish

churches.

Monasteries might

also seek rights to appropriate a church in proprios

usus, or to its own uses. This gave complete control top a monastery

over church affairs. So while Abbot Roger of Byland did not wish to accept the

offer of churches in the 140s, attituides changed

when it became possible to appropriate full rights. Monasteries could expect

financial benefits, though these came with responsibilities to provide for the

cure of souls. In that regard monasteries had a number of choices:

· It could delegate

one of its monks to perform these duties, but this would involve the removal of

an individual from the discipline of communal monastic life.

· It could appoint

a stipendiary chaplain, though there was then no control over the size of the

emolument.

· The usually

preferred course was therefore to present a vicar to serve on its behalf, and

for the vicar to be paid from a portion of the church revenues.

4. Difficulties

which arose from monastic influence in parishes.

The significant

numbers of monastic foundations in the twelfth century could lead to conflict.

The main source of income for a parish church was the tithe, one tenth of the

produce of the land intended to sustain the parish priest. Where churches were

appropriated to monasteries, these funds came to the monasteries.

In the first

fifteen years after the foundation of Rievaulx, it obtained modest grants of

land, generally waste land, meadow and common pasture, within twelve miles of

the abbey. Roger de Mowbray, via his mother Gundreda

of Gournay gave lands at Welburn (Kirkdale) as well as Skiplam,

Farndale and Bransdale. At about the same time as the

Farndale grant, Roger granted the whole of the vil of Welburn with six bovates of land (but excepting the Church

of Kirkdale)

to Rievaulx.

This land had been in the possession of the Augustinian priory of Newburgh.

Another source of conflict arose when the Cistercians obtained

papal freedom from payment of tithes on land which they cultivated themselves

Edmund the Hermit

Edmund the hermit

of Farndale was

a legendary figure who lived in a cave in the North York Moors in the Twelfth

century. He was said to be a holy man who performed miracles and healed

the sick. He was also reputed to be a descendant of King Alfred the Great

and a cousin of King Stephen.

However, there is

no historical evidence to support his existence or his royal lineage. He

may have been a fictional character created by local monks to attract

pilgrims and donations to their monastery. Alternatively, he may have been

based on a real person who lived in the cave, but whose identity and story

were embellished over time. Some scholars have suggested that he may have

been a Norman knight who fled to the cave after the Battle of the

Standard in 1138, or a Saxon rebel who resisted the Norman conquest.

The cave where

Edmund supposedly lived is known as Hob Hole and is located near

Westerdale in Farndale. It is a natural limestone cave that has been

enlarged by human activity. It has two chambers, one of which may have served

as a chapel. The cave is now a scheduled monument and is protected by law. You

can see some photos of the cave.

In Christianity,

the term Hermit was originally applied to a Christian who lives the eremitic

life out of a religious conviction, namely the Desert Theology of

the Old Testament.

In the Christian

tradition the eremitic life is an early form of monastic

living that preceded the monastic life in the cenobium.

The Rule of St Benedict listed hermits among four kinds

of monks. In the canon law of the Episcopal Church they are referred to as

"solitaries" rather than "hermits

Often, both in

religious and secular literature, the term "hermit" is also used

loosely for any Christian living a secluded prayer-focused life, and

sometimes interchangeably with anchorite/anchoress, recluse and

"solitary”

Religious hermits

were the original residents of many of Ryedale's most remote outposts. Edmund

was first at Farndale, Osmund at Goathland and the Saintly Godric in Eskdale.

The Fern

The name Farndale seems to come from the Celtic ‘farn, or fearn’

meaning ‘fern’ and the Norwegian ‘dalr’,

meaning ‘dale;’ and so was the ‘dale where the ferns grew.’

Of course whilst

Farndale is today dominated by moorland bracken and ferns, ferns are naturally

a woodland plant, so it must have been the ferns of the forested Farndale which

gave rise to its name. Perhaps it was Edmund who must have known the valley intricately,

first chose its name.

The ferns in

Farndale, from which Farndale gets its name