Georgins ffarndayle

16 March 1602 to 17 August 1693 (buried)

FAR00073

|

Return to the Home

Page of the Farndale Family Website |

The story of one

family’s journey through two thousand years of British History |

The 83 family lines

into which the family is divided. Meet the whole family and how the wider

family is related |

Members of the

historical family ordered by date of birth |

Links to other pages

with historical research and related material |

The story of the

Bakers of Highfields, the Chapmans, and other related families |

George lived

during the English Civil War and certainly experienced local battles and may

have been involved directly.

Headlines of

George Farndale’s life are in brown.

Dates are in red.

Hyperlinks to

other pages are in dark

blue.

References and

citations are in turquoise.

Context and local

history are in purple.

1602

Georgins ffarndayle

was born 16 March 1602 and baptised at Skelton

on 28 March 1602, the son of George ffarndayle and

Margery nee Nelson Farndale (FAR00067) (Skelton PR).

A now off-line website (www.birdsinthetree.com) indicated that

George Farndale born 16 March 1602 and that his mother was Margery Nelson (with

no information about father) and we know that George Farndale married

Margery Nelson.

When George

Farndale was born in 1602, his father, George, was therefore 32 and his mother,

Margery nee Nelson, was also 32. George lived at Moorsolm. This is

consistent with his father.

1607

George’s father,

George Farndaile was buried on 9 March 1607 at

Skelton (Skelton Parish Records). He was

probably only about 42. George was only five. They may have been living at Moorsholm by then.

1609

George’s father’s

will: ‘The Dean of Cleveland grants guardianship of William Farndaile, Susan, George and Richard Farndaile, children of George Farndale, deceased, together

with administration of their affairs, goods, rights and portions to Margery

Farndale by choice of the said children.’ (York

Wills).

1623

George farnedayle must

have married between 1623 and 1624, given the dates of birth of his children.

His wife’s name was probably Jane or Jaine (sic) Farndale (1610-1678)

who died at Liverton on 26 August 1678 (Liverton PR).

1625

William Farndale was born at Liverton on 20

November 1625 (FAR00078) (Liverton

PR).

1634

Nicholas Farndale, was born at Liverton on 6 July

1634 (FAR00082) (Liverton

PR).

1636

Jane Farndale, was born Liverton on 17 November

1636 (FAR00086) (Liverton

PR).

1637

Isabell Farndale, was born Liverton on 18 March

1637 or 1638 (FAR00088) (Liverton

PR).

1642

The

English Civil War which began in 1642 was part of the wider Wars

of the Three Kingdoms 1639 to 1653. Parliament voted on 12 July 1642 to raise a force under the

command of the Third Earl of Essex and required an oath of allegiance. The King issued commissions of array

to allow the raising of militias and raised his flag at Nottingham on 22 August

1642. Each side seized

towns, strongpoints and military stores. The King was locked out of the largest

military depot at Hull. Counties

petitioned for compromise. Counties such as Yorkshire dragged their feet.

It is too

simplistic that the war was just a fight between liberty on the part of the

Parliamentarians against the tyranny of Stuart absolutism. Nor was it primarily

about class struggle. The ancient peerages tended to back the Parliamentarians

as they disliked the novelties of Stuart government. Religion was the clearest

dividing line, but religious spectrums were fluid and nearly everyone belonged

to the Church of England. A third of Puritans in 1643 were Royalist. Instead

there was division everywhere and every town and village and many families were

divided. Most fought because they were conscripted. Families split. There were

shifting coalitions and people changed sides.

Early in the

Civil War there was a campaign

for the north in 1643. When the first great battle of the Civil War, at Edgehill

on 23 October 1642, failed to deliver the expected resolution, both Royalists

and Parliamentarians rushed to take control of extensive territories as the

basis from which to support a long campaign. In the north the King gave this

task to the Marquis of Newcastle. By November 1642 the Royalist city of York was coming under increasing threats from the

Parliamentarian forces of the Hothams and Cholmley

from the north east and the Fairfaxes from the west.

The Royalist

Marquis of Newcastle raised an army some 6,000 to 8,000 strong and marched to York. He initially swept away the

Parliamentary opposition and took York as a

key strategic hub. Parliamentarian opposition in Yorkshire was led by

Ferdinando Lord Fairfax and his son Sir Thomas. The heartland of their power

was in the cloth towns of the West Riding. They had become cut off from their

main port at Scarborough. However they

were able to recruit a significant force of musketeers from their cloth towns

base.

The

Parliamentarian strategy was to interrupt the Royalist supply of arms. In mid January Sir Hugh Cholmley led a small Parliamentarian

army from Malton to Guisborough.

A

small skirmish took place somewhere between Skelton and Guisborough, in the immediate vicinity of

the new Farndale homes of Moorsholm and Liverton, on 16 January 1643 between

Royalists under the command of Colonel Guildford Slingsby and Parliamentarians

under Sir Hugh Cholmley and Sir Matthew Boynton. The Parliamentarian army of

about 380 men seem to have approached the battlefield from the moors and they

were met by Slingsby’s force of about 400 foot and 100 horse, who were being

drilled in Guisborough. Slingsby

took the initiative by charging his cavalry against Cholmley’s

horse with some success. However, his foot soldiers were forced back by the

Parliamentarians, and he withdrew to rally his inexperienced recruits. As he was doing so, he was caught by case

shot from the parliamentarian artillery and mortally wounded. The Royalist

force crumbled and many were captured.

George

Farndale was 41 in 1643, living at Moorsholm and his

brother Richard Farndale

was 39, living at Liverton. They were both

about eight kilometres from the battle. It is difficult

to find lists of civil war soldiers. Loyalties were divided. It is quite

possible that one or more of the brothers were part of the newly recruited army

of Colonel Guildford Slingsby who were being drilled in Guisborough. This was a pretty chaotic

period of time. Whether the brothers took part of the battle, it must have been

a significant event. They must have smelt it, heard it, seen it perhaps.

Cholmley

returned over the moors to Malton and later defected to the Royalists, but he

had sent his force on to a bridge crossing over the River Tees at Yarm,

south of Stockton, to try to stop a large

Royalist munitions convoy travelling from Newcastle to York on 1 February 1643.

The Parliamentarians, who may

have set up barricades, were quickly overwhelmed, losing over thirty men killed

and many wounded and captured. Others fled. The prisoners were marched to

Durham. The defeat may have helped influence parliamentarian Sir Hugh Cholmley

to change sides a few weeks later.

The attempt

to disrupt the Royalist army moved its focus to the Tadcaster area and there

was another Parliamentarian defeat at Seacroft

Moor near York on 30 March 1643.

The Battle

of Marston Moor took place west of York on

2 July 1644. During the summer of 1644, the Parliamentarians had been besieging

York. Prince Rupert had gathered a

Royalist army which marched through the northwest of England, gathering

reinforcements to relieve the city. The convergence of these forces made the

ensuing battle the largest of the Civil War. Rupert outmanoeuvred the Parliamentarians

to relieve the city and then sought battle with them even though he was

outnumbered. Both sides gathered their full strength on Marston Moor, an

expanse of wild meadow west of York. Towards

evening, the Parliamentarians themselves launched a surprise attack. After a

confused fight lasting two hours, Parliamentarian cavalry under Oliver Cromwell

routed the Royalist cavalry from the field and, with the Earl of Leven's

infantry, annihilated the remaining Royalist infantry. After their defeat the

Royalists effectively abandoned Northern England, losing much of the manpower

from the northern counties which were strongly Royalist in sympathy and also

losing access to the European continent through the ports on the North Sea

coast. The loss of the north was to prove a fatal handicap the next year, when

they tried unsuccessfully to link up with the Scottish Royalists under the

Marquess of Montrose.

In December

1644, a New Model Army of 22,000 men was formed by the Parliamentarians under

Lord General Sir Thomas Fairfax. This was the nation’s first professional army.

There was a new officer corps. The Self Denying Ordinance removed Members of

Parliament from military command, though with the notable exception of the MP

Oliver Cromwell, who was given command. The army was detached from civilian

society. Harsh discipline was imposed with penalties for drunkenness and

blasphemy. Sir Thomas Fairfax came from a Yorkshire gentry family. The Fairfaxes were among Parliament's leading supporters in

northern England.

The Royalist

forces suffered painful defeats in 1645. Nevertheless, there was factionalism

amongst the Parliamentarians. The Scottish Alliance had brought with it the

threat of an authoritarian system based on Scottish Presbyterianism. A faction

of Independents emerged within the Parliamentarians who sought liberty of

conscience. Many in the Army supported the Independents.

The New

Model Army soon became a problem. Its cost and the need for taxation caused

resentment. The army came to be hated by the civilian population. But

disbanding was also a problem with significant arrears of pay, amounting to

£3M. The army was seeking its own terms, including protection from being sent

to fight in Ireland and indemnity from prosecution for acts during the war.

By 1645,

many clergy who could not agree with puritan ideals were removed from their

livings and Marske Parish records of this time shows evidence of this amongst Skelton

folk.

In July

1647, the army commanders offered conciliatory terms, Heads of Proposals, which

included tolerance for the Anglicans. Charles was initially conciliatory, but

eventually rejected the terms. Charles was taken to Hampton Court.

Active

political debates were started in the period of political instability following

the end of the civil war. The Putney Debates were held

from 28 October to 8 November 1647 which discussed such ideas as every man

that is to live under a government ought first by his own consent to put

himself under that government. The Levellers

came to prominence at the end of the Civil War, led by John

Lilburne, and were most influential immediately

before the start of the Second Civil War. Leveller views and support were found

in the populace of the City of London and in some regiments in the New Model

Army. The Levellers wanted limited government, though Lilburn denied that he wanted to level all men’s estates.

A Second

Civil War restarted in 1648. In June 1648 Royalists sneaked into Pontefract

castle, only a few miles north of the old Farndale home of Campsall,

and took control. The Castle was an important base for the Royalists, and

raiding parties harried Parliamentarians in the area. Oliver Cromwell led the

final siege of Pontefract Castle in November 1648. Charles I was executed in

January 1649, and Pontefract's garrison came to an agreement and Colonel

Morrice handed over the castle to Major General John Lambert on 24 March 1649.

Following requests from the townspeople at a grand jury at York, on 27 March 1649 Major General Lambert was

ordered by Parliament that Pontefract Castle should be totally demolished

& levelled to the ground and materials from the castle would be sold

off.

1673

George farndaile had one hearth at Moorsome

in 1673 (Hearth Tax Returns).

1674

George ffarndaile hath

two hearths at Moorsome in 1674 (Hearth Tax Returns).

1678

Jaine Farndale, probably his wife (although it could have been his daughter),

was buried at the Anglican Church of St Michael at Liverton on 26 August 1678. Their

daughter Jane had died at birth, so this was probably George’s wife, also Jane.

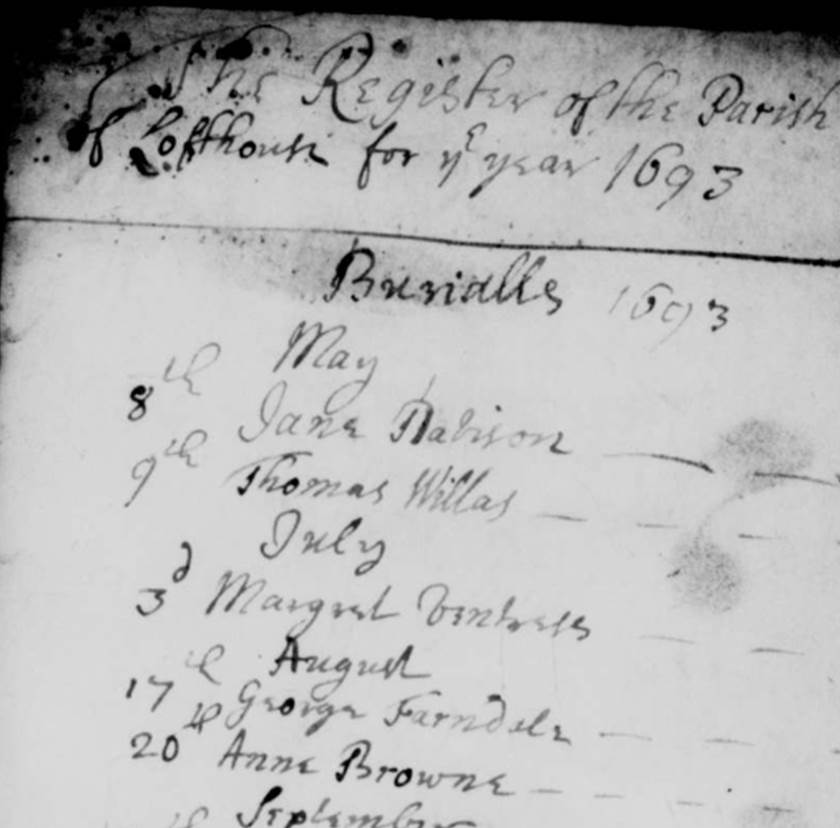

1693

George Farndale

died in August 1693 in Loftus,

Yorkshire, at the impressive age of 91. Loftus

might have been the registration if he was still living at Moorsholm.

George Farndale

was buried at Loftus on 17 August 1693.