|

|

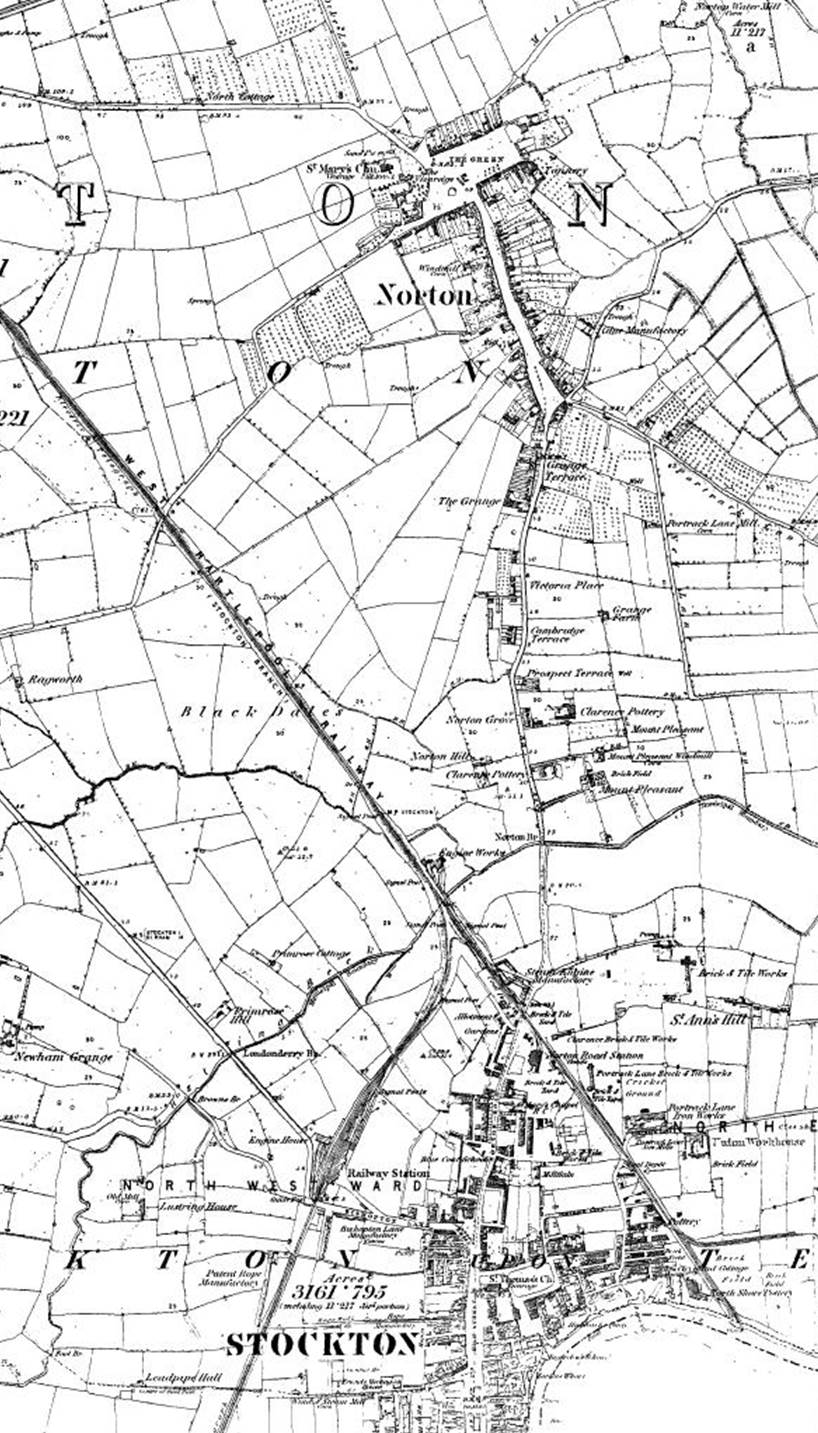

Stockton

Historical and geographical information

|

|

Dates are in red.

Hyperlinks to other pages are in dark blue.

Headlines are in brown.

References and citations are in turquoise.

Contextual history is in purple.

This

webpage about the Stockton has the

following section headings:

- Farndale

family history and Stockton

- Stockton,

overview

- Timeline of

Stockton history

- The Stockton

and Darlington Railway

- Links, texts

and books

The Farndales of Stockton

The Stockton

1 Line are the descendants of John Farndale (FAR00230), 1796 to

1868, farmer, farm labourer, then iron foundry labourer in Stockton.

John Farndale (FAR00305)(born

1829) was a grocer’s warehouseman of Stockton. Peter Farndale (FAR00373), 1847

to 1895 was a solicitor’s clerk of Stockton. The Stockton 2 Line are the

descendants of Robert Farndale (FAR00254), 1814

to 1866, was a master grocer of Stockton (grocer's assistant in 1861). Robert

Edward Farndale (FAR00363)

1844 to 1875 was a plasterer and cement maker of Stockton who later lived in

Birmingham. The Stockton 3 Line are the

descendants of William Farndale (FAR00386), born

1851, was a footman of Hutton Ambro and later a labourer in a wine vault. James

Farndale (FAR00833),

1916 to 1941 was a private of the West Yorkshire Regiment who died of wounds on

16th March 1941 in Eritrea.

John Farndale (FAR00217), the

author lived in Stockton.

Stockton

Stockton-on-Tees is

a market town in County Durham.

Stockton is an Anglo-Saxon name with the typical

Anglo-Saxon place name ending 'ton' meaning farm, or homestead. The name is

thought by some to derive from the Anglo-Saxon word Stocc meaning

log, tree trunk or wooden post. 'Stockton' could therefore mean a farm built of

logs. This is disputed, because when the word Stocc

forms the first part of a place name it usually indicates a derivation from the

similar word Stoc, meaning cell, monastery or place. 'Stoc' names

along with places called Stoke or Stow, usually indicate farms which

belonged to a manor or religious house. It is thought that Stockton fell into

this category and perhaps the name is an indication that Stockton was an

outpost of Durham or Norton which were both important

Anglo-Saxon centres. This is a matter of dispute, but Stockton was only a part

of Norton until the eighteenth century, when it became an independent parish in

its own right. Today the roles have been reversed and Norton has been demoted

to a part of Stockton.

Stockton Timeline

125,000 BCE

Stockton

is known to be the home of the fossilised remains of the most northerly hippopotamus ever

discovered on Earth. In 1958, an archaeological dig four miles north-west of

the town discovered a molar tooth from a hippo dating back 125,000 years ago.

However, no-one knows where exactly the tooth was discovered, who discovered

it, or why the dig took place. The tooth was sent to the borough's librarian

and curator, G. F. Leighton, who then sent to the Natural History Museum, London.

Since then the tooth has been missing, and people are trying to rediscover it.

Anglo Saxon

Stockton

began as an Anglo-Saxon settlement on high ground close to the northern bank of

the River Tees.

The Victoria County History – Durham, A History of the County

of Durham: Volume 3 Parishes: Stockton on Tees, 1928: The early

history of Stockton is bound up with that of Norton. From the names it may be surmised

that Stockton was the original Anglian settlement formed upon a defensible site

beside the river, and that Norton afterwards grew up to the north either as

pleasanter to dwell in or more secure from attack. Later, while the church was

built at Norton, which thus gave a name to the parish, the bishops preferred to

establish their manor-house at Stockton, which provided a name for the ward or

administrative division of the county.

1138

The manor of

Stockton was created around 1138.

1189

The

manor of Stockton was purchased by Bishop Pudsey of Durham in

1189.

Thirteenth century

During

the 13th century, the bishop turned the village of Stockton into a borough.

When the bishop freed the serfs of Stockton, craftsmen came

to live in the new town. The bishop had a residence in Stockton Castle,

which was just a fortified manor house.

1310

Stockton's

market can trace its history to 1310 when Bishop Bek of Durham granted a

market charter: to

our town of Stockton a market upon every Wednesday for ever. The town grew

into a busy little port, exporting wool and

importing wine which

was demanded by the upper class. However even by the standards of the

time, medieval Stockton-on-Tees was a small town

with a population of only around 1,000, and did not grow any larger for

centuries.

1376

The first

recorded reference to the castle was in 1376.

1569

The

Victoria County History – Durham, A History of the

County of Durham: Volume 3 Parishes: Stockton on Tees, 1928: According to Sir

George Bowes in 1569 'the best country for corn' lay around Stockton. The

district was in 1647 described as a 'champion country, very fruitful, though a

stiff clay'; there was no wood growing on the castle demesne or elsewhere in

that part of the country. In an official report of the end of the 18th century

the soil was described as loamy or rich clay; the flat grounds near the Tees,

which were of considerable extent, were drained by means of wide ditches

commonly called 'Stells.' Wheat and other cereals are grown. A chamber of

agriculture was formed in 1888.

Seventeenth century

Shipbuilding

in Stockton, which had begun in the 15th century, prospered in the 17th and

18th centuries. Smaller-scale industries began developing around this time,

such as brick, sail and rope making, the latter reflected in road names such as

Ropery Street in the town centre. Stockton became the major port for County Durham,

the North Riding of Yorkshire and Westmorland during

this period, exporting mainly rope made in the town, agricultural produce

and lead from

the Yorkshire Dales.

1644

The Scots captured

Stockton Castle in 1644 and occupied it until 1646. It was destroyed at the

order of Oliver Cromwell at the end of the Civil War.

1735

The

Town House was built in 1735.

1740

The

Victoria County History – Durham, A History of the

County of Durham: Volume 3 Parishes: Stockton on Tees, 1928: In 1740 there was a great disturbance

here; wheat was scarce, and in May and June the populace refused to allow any

to be exported from the town. Soldiers were brought in to overawe them, some

prisoners were made and sent to Durham, but there the mob released them.

Troops, this time Germans, were again brought to Stockton in 1745–6 during the

alarm caused by the early successes of the Scottish Jacobites under Charles

Edward the Young Pretender, and their advance to Carlisle and Derby. Their

final defeat at Culloden was celebrated in festive manner; among other

illuminations was that provided by a raft laden with combustibles on fire and

sent floating down the Tees. Wesley, who visited the town many times, gives the

following account of a press-gang raid in July 1759:

I

began near Stockton market-place as usual. I had hardly finished the hymn when

I observed the people in great confusion, which was occasioned by a lieutenant

of a man-of-war who had chosen that time to bring his press-gang and ordered

them to take Joseph Jones and William Allwood. Joseph Jones telling him, 'Sir,

I belong to Mr. Wesley,' after a few words he let him go; as he did likewise

William Allwood, after a few hours, understanding he was a licensed preacher.

He likewise seized upon a young man of the town, but the women rescued him by

main strength. They also broke the lieutenant's head, and so stoned both him

and his men that they ran away with all speed.

1766

The

first theatre in Stockton opened in 1766.

1771

In

1771, a five arch stone bridge was built replacing the nearby Bishop's Ferry.

Until the opening of the Middlesbrough Transporter Bridge in

1911, this was the lowest bridging point on the Tees.

1779

The Victoria County History – Durham, A History of the County

of Durham: Volume 3 Parishes: Stockton on Tees, 1928: The wars with the

French in the latter part of the 18th century contributed in certain ways, as

in shipbuilding, to the material prosperity of the town, but alarm was caused

in 1779 by the appearance of Paul Jones, the American privateer, off the mouth

of the Tees, where he captured a sloop. A small band of volunteers was raised

about that time for the defence of the town, and another corps in 1798 called

the Loyal Stockton Volunteers or 'Blue Coats.' These were disbanded in 1802,

but again enrolled in 1803, and finally disembodied in 1813.

Late Eighteenth Century

From

the end of the 18th century the Industrial Revolution changed

Stockton from a small and quiet market town into a flourishing centre of heavy

industry. The town grew rapidly as the Industrial Revolution progressed, with

iron making and engineering beginning in the town in the 18th century.

1807

Wordsworth

wrote part of the White Doe of Rylstone while on a visit to the

Hutchinsons at Stockton in 1807.

1851

The

town's population was 10,000 in 1851. .

The discovery of iron ore in the Eston Hills resulted

in blast furnaces lining the River Tees from

Stockton to the river's mouth. In 1820 an Act set up the Commissioners, a body

with responsibility for lighting and cleaning the streets. From 1822

Stockton-on-Tees was lit by gas.

1825

In

1825, Stockton witnessed an event which changed the face of the world forever

and heralded the dawn of a new era in trade, industry and travel. The first

rail of George Stephenson's Stockton and Darlington Railway was

laid near St. John's crossing on Bridge Road. Hauled by Locomotion No

1, the great engineer himself manned the engine on its first journey

on 27 September 1825. Fellow engineer and friend, Timothy

Hackworth acted as guard. This was the world's first passenger

railway, connecting Stockton with Shildon.

The opening of the railway greatly boosted Stockton, making it easier to bring

coal to the factories; however the port declined as business had moved down

river to Middlesbrough.

1827

Stockton

witnessed another discovery in 1827. Local chemist John Walker invented the friction

match in his shop at 59 High Street. The first sale of the

matches was recorded in his sales-book on 7 April 1827, to a Mr. Hixon, a

solicitor in the town. Since he did not obtain a patent, Walker received

neither fame nor wealth for his invention, but he was able to retire some years

before his death. He died in 1859 at the age of 78 and is buried in the parish

churchyard in Norton village.

1834

In

1833 the then Bishop of Durham, William Van Mildert (1765 - 1836) gifted five

acres and the land of an existing burial site called "The Monument"

(originally a mass grave from a prior cholera outbreak) to the town of

Stockton. Upon this land, the process of building of and designing the gothic

style Holy Trinity Church began, using funds originally allocated for church

building in the Commissioners' church Act of 1818. It was designed by John and

Benjamin Green, and construction began in 1834. It was consecrated as an

Anglican church on December 22, 1835.

1856

The

first bell for Big Ben was cast by John Warner and Sons in Norton on 6 August 1856, but became

damaged beyond repair while being tested on site and had to be replaced by a

foundry more local to Westminster.

1858

The Victoria County History – Durham, A History of the County

of Durham: Volume 3 Parishes: Stockton on Tees, 1928: A weekly newspaper,

the Stockton and Thornaby Herald, is published at Stockton on Saturdays. It was

founded in 1858. The earliest newspaper published here was the Advertiser,

begun in 1858, but lasting only a year. A local magazine called the Stockton

Bee began in 1793 and continued until 1795; it contained essays, poems, puzzles

and other miscellaneous articles. The Gazette was founded in 1859 by the

efforts of Robert Spears, a Unitarian minister then stationed at Stockton. It

continues as the North-eastern Gazette, published at Middlesbrough. The News

and Advertiser, begun in 1864, and the Examiner, later, did not succeed.

1867

1877

A

hospital opened in Stockton in 1862 and a public library opened in 1877.

1881

Steam trams began running

in the streets in 1881 and were replaced by electric trams in 1897. Buses

replaced the trams in 1931.

1901

Stockton’s

population had reached over 50,000 in 1901.

1928

The

Victoria County History – Durham, A History of the

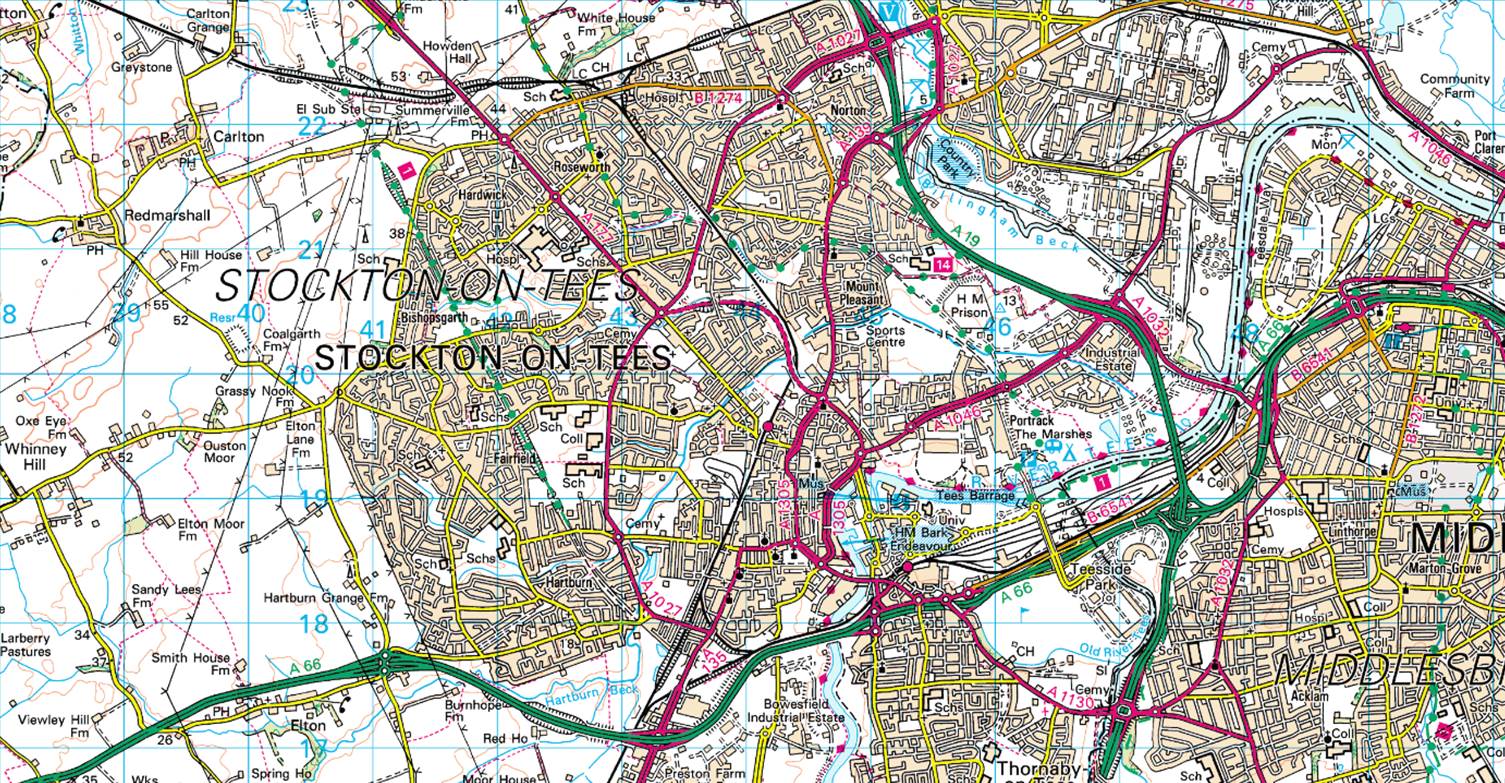

County of Durham: Volume 3 Parishes: Stockton on Tees, 1928: The town of

Stockton grew up on the elevated tongue of land between the Tees and Lustring

Beck, along the road going north from the Bishop of Durham's manor-house or

castle, long ago destroyed, to the old parish church at Norton…. Stockton is now

mainly urban, but it was formerly a rich agricultural district. … The main

part of the town of Stockton, centrally placed in its township, stands well up

above the river, here flowing north, whereas on the opposite Yorkshire bank the

land is low and flat; but to the east of the town is a large low-lying tract of

marsh land, and on the north and west is the valley of the Lustring Beck. The

winding course of the Tees to the east of the town caused serious inconvenience

to shipping even when sea-going vessels were very small compared with their

modern successors.

1930s

In the

1930s slums were cleared and the first council houses were built. At this time,

Stockton was still dominated by the engineering industry and there was also a

chemicals industry in the town.

1933

On

10 September 1933 the Battle of Stockton took place, in which

between 200 and 300 supporters of the British Union of Fascists were taken

to Stockton and attempted to hold a rally in the town, but they were driven out

by up to 2,000 anti-fascist demonstrators.

1990s

In

the late 20th century manufacturing industry severely declined, although

the service industries grew, and today are the

town's main employers.

The Ragworth district near the town centre was the scene of rioting

in July 1992, when local youths threw stones at buildings, set cars alight and

threw missiles at police and fire crews. The area later saw a £12million

regeneration which involved mass demolition or refurbishment of the existing

properties, as well as new housing and community facilities being built.

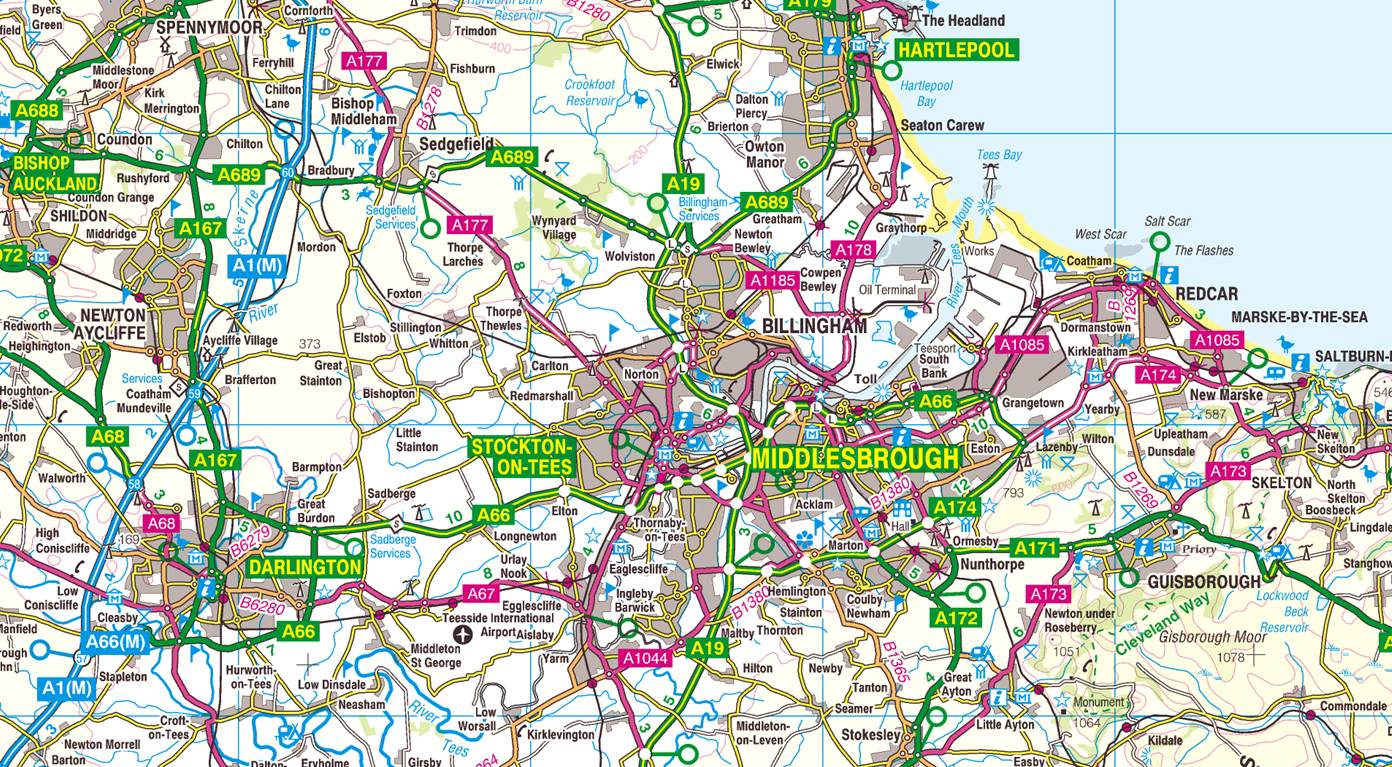

The Stockton and Darlington Railway

The Stockton and Darlington Railway (“S&DR”)

was a railway company that operated in north-east England from 1825 to 1863.

The world's first public railway to use steam

locomotives, its first line connected collieries near Shildon with Stockton-on-Tees and Darlington,

and was officially opened on 27 September 1825. The movement of coal to ships

rapidly became a lucrative business, and the line was soon extended to a new

port and town at Middlesbrough. While coal waggons were hauled

by steam locomotives from the start, passengers were carried in coaches drawn

by horses until carriages hauled by steam locomotives were introduced in 1833.

The

S&DR was involved in the building of the East Coast Main Line between York and Darlington,

but its main expansion was at Middlesbrough Docks and west into Weardale and

east to Redcar.

It

suffered severe financial difficulties at the end of the 1840s and was nearly

taken over by the York, Newcastle and Berwick Railway,

before the discovery of iron ore in Cleveland and the subsequent increase in

revenue meant it could pay its debts.

At

the beginning of the 1860s it took over railways that had crossed the Pennines to

join the West Coast Main Line at Tebay and Clifton, near Penrith.

The

company was taken over by the North Eastern Railway in

1863, transferring 200 route miles of line and about 160 locomotives, but

continued to operate independently as the Darlington Section until 1876.

The opening of the S&DR was seen as

proof of the effectiveness of steam railways and its anniversary was celebrated

in 1875, 1925 and 1975. Much of the original route is now served by the Tees Valley

Line, operated by Northern.

The seal of the Stockton & Darlington Railway

The Victoria County

History – Durham, A History of the County of Durham: Volume 3 Parishes:

Stockton on Tees, 1928: Stockton

has a prominent place in the history of railways, for the first line on which

locomotive engines were used is that from Stockton to Darlington. This was

begun in 1822 and formally opened on 27 September 1825. The station was at the

south end of the town and is now a goods station. The line was continued along

the line of quays. In 1830 a suspension bridge was thrown across the Tees to

carry a line to Middlesbrough; this had to be supported by timber struts, and

in 1844 was replaced by an iron bridge. Coals were delivered at Stockton by the

Port Clarence railway in 1833. A railway to Hartlepool was opened in 1841, the

station being in Bishopton Lane; the company was incorporated in 1842. In 1852

it was amalgamated with the Hartlepool West Harbour and Dock Company as the

West Hart!epool Harbour and Railway Company, and took

over the Port Clarence line. In 1846 the Leeds and Northern railway, now the

North Eastern, obtained powers to make a branch to Stockton by way of Yarm and Egglescliffe, and the station in Bishopton Lane was opened

on 15 May 1852. By amalgamation in 1854 and later all the lines have been

united in the North Eastern system, and the Bishopton Lane station has been

enlarged and made the only passenger station in the parish, that called Eaglescliffe Station being just outside on the south. There

is a branch goods line with a station in Norton Road, at the north end, running

to the river side; near this point there is a ferry across to Thornaby. The

Stockton and Castle Eden branch passes on the west through Stockton and East

Hartburn. The tramways through Stockton connect the town with Thornaby,

Middlesbrough and North Ormesby in one direction and with Norton in another;

they were first formed in 1882, and are owned by a private company. Before that

time there was an omnibus service to Norton.

Eighteenth century

Coal from the inland mines

in southern County Durham was taken away on packhorses,

and then horse and carts as the roads were improved. A canal was proposed

by George Dixon in 1767

and again by John Rennie in 1815, but both schemes

failed. Meanwhile, the port of Stockton-on-Tees,

from which the Durham coal was transported onwards by sea, had invested

considerably during the early 19th century in straightening the Tees in order to

improve navigation on the river downstream of the town and was subsequently

looking for ways to increase trade to recoup those costs.

A few years later a canal

was proposed on a route that bypassed Darlington and Yarm, and a meeting was

held in Yarm to oppose the route. The Welsh engineer George Overton was

consulted, and he advised building a tramroad. Overton carried out a survey and

planned a route from the Etherley and Witton

Collieries to Shildon, and then passing to the north of Darlington to

reach Stockton.

1818

The Scottish

engineer Robert Stevenson was

said to favour the railway, and the Quaker Edward Pease supported

it at a public meeting in Darlington on 13 November 1818, promising a five per

cent return on investment. Approximately two-thirds of the shares were

sold locally, and the rest were bought by Quakers nationally.

1819

A private bill was

presented to Parliament in March

1819, but as the route passed through Earl of Eldon's estate and one of

the Earl of Darlington's fox

coverts, it was opposed and defeated by 13 votes.

1820

Overton surveyed a new line

that avoided Darlington's estate and agreement was reached with Eldon, but

another application was deferred early in 1820, as the death of King George

III had made it unlikely a bill would pass that parliamentary

year. The promoters lodged a bill on 30 September 1820, the route having

changed again as agreement had not been reached with Viscount Barrington about the line passing

over his land. The railway was unopposed this time, but the bill nearly

failed to enter the committee stage as the required four-fifths of shares had

not been sold.

Pease subscribed £7,000;

from that time he had considerable influence over the railway and it became

known as "the Quaker line".

1821

The Act that

received royal assent on 19 April 1821 allowed for

a railway that could be used by anyone with suitably built vehicles on payment

of a toll, that was closed at night, and with which land owners within 5 miles

could build branches and make junctions; no mention was made of steam

locomotives. This new railway initiated the construction of more railway

lines, causing significant developments in railway mapping and cartography,

iron and steel manufacturing, as well as in any industries requiring more

efficient transportation.

Concerned about Overton's

competence, Pease asked George

Stephenson, an experienced engine-wright of the collieries of

Killingworth, to meet him in Darlington.

On 12 May 1821 the

shareholders appointed Thomas Meynell as Chairman and Jonathan Backhouse as

treasurer; a majority of the managing committee, which included Thomas Richardson, Edward

Pease and his son Joseph Pease, were

Quakers.

The committee designed a

seal, showing waggons being pulled by a horse, and adopted the Latin motto Periculum

privatum utilitas publica ("At private risk for public

service").

By 23 July 1821 it had

decided that the line would be a railway with edge rails, rather than a plateway,

and appointed Stephenson to make a fresh survey of the line. Stephenson

recommended using malleable iron rails, even though he owned a share of the patent

for the alternative cast iron rails, and both types were used. Stephenson

was assisted by his 18-year-old son Robert during

the survey, and by the end of 1821 had reported that a usable line could

be built within the bounds of the Act, but another route would be shorter by 3

miles and avoid deep cuttings and tunnels.

1822

Overton had kept himself

available, but had no further involvement and the shareholders elected

Stephenson Engineer on 22 January 1822, with a salary of £660 per year.

On 23 May 1822 a ceremony

in Stockton celebrated the laying of the first track at St John's Well, the

rails 4 feet 8 inches apart, the same gauge used

by Stephenson on his Killingworth Railway.

Stephenson advocated the use of steam

locomotives on the line. Pease visited Killingworth in mid-1822 and

the directors visited Hetton colliery railway, on which

Stephenson had introduced steam locomotives.

1823

A new bill was presented, requesting

Stephenson's deviations from the original route and the use of

"loco-motives or moveable engines", and this received assent on 23

May 1823. The line included embankments up to 48 feet high, and Stephenson

designed an iron truss bridge to cross the River Gaunless. The stone bridge over the River Skerne was

designed by the Durham architect Ignatius

Bonomi.

In 1823 Stephenson and Pease

opened Robert Stephenson and Company, a locomotive works

at Forth Street, Newcastle, from which the following

year the S&DR ordered two steam locomotives and two stationary engines.

1825

On 16 September 1825, with the

stationary engines in place, the first locomotive, Locomotion

No. 1, left the works, and the following day it was advertised that

the railway would open on 27 September 1825.

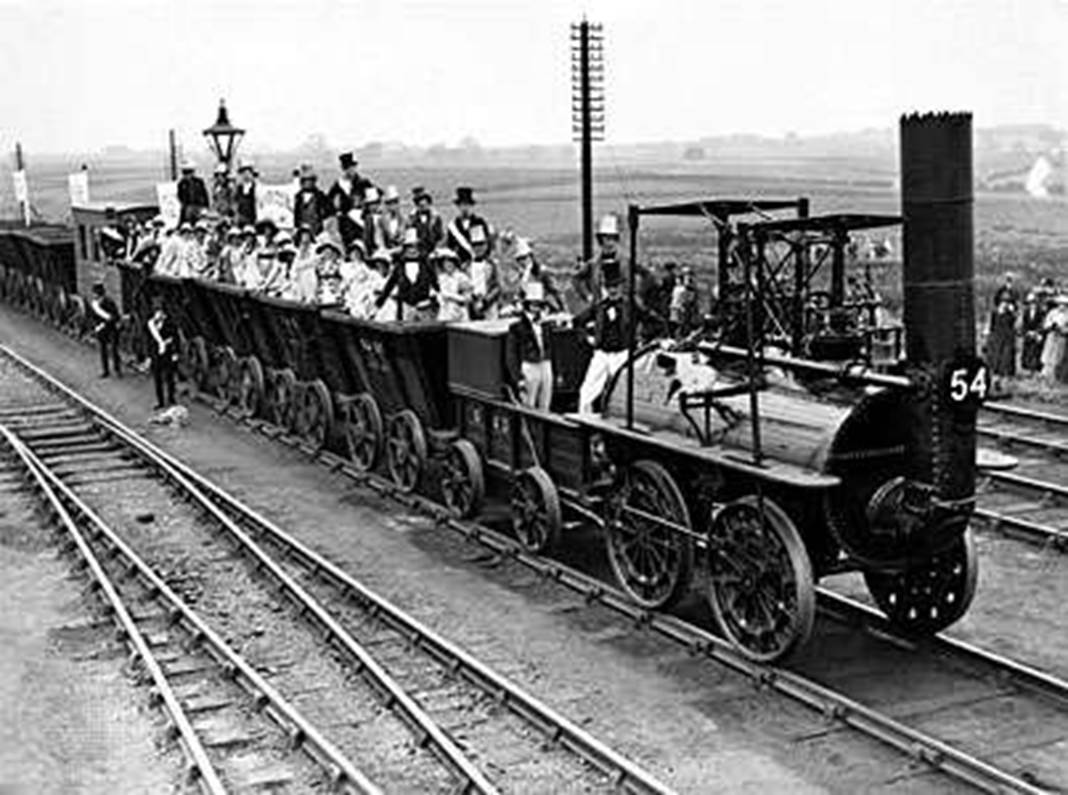

The opening procession of

the Stockton and Darlington Railway crosses the Skerne bridge

The cost of building the

railway had greatly exceeded the estimates.

By September 1825 the

company had borrowed £60,000 in short-term loans and needed to start earning an

income to ward off its creditors. A railway coach, named Experiment, arrived

on the evening of 26 September 1825 and was attached to Locomotion No. 1,

which had been placed on the rails for the first time at Aycliffe Lane station following the completion

of its journey by road from Newcastle earlier that same day. Pease, Stephenson

and other members of the committee then made an experimental journey to

Darlington before taking the locomotive and coach to Shildon in preparation for

the opening day, with James Stephenson, George's elder brother, at the

controls.

On 27 September 1825,

between 7am and 8am, 12 waggons of coal were drawn up Etherley

North Bank by a rope attached to the stationary engine at the top, and then let

down the South Bank to St Helen's

Auckland. A waggon of flour bags was attached and horses hauled the

train across the Gaunless Bridge to the bottom

of Brusselton West Bank,

where thousands watched the second stationary engine draw the train up the

incline. The train was let down the East Bank to Mason's Arms Crossing at

Shildon Lane End, where Locomotion No. 1, Experiment and 21 new

coal waggons fitted with seats were waiting.

The directors had allowed

room for 300 passengers, but the train left carrying between 450 and 600

people, most travelling in empty waggons but some on top of waggons full of

coal. Brakesmen were placed between the waggons, and

the train set off, led by a man on horseback with a flag. It picked up speed on

the gentle downward slope and reached 10 to 12 miles per hour, leaving behind

men on field hunters (horses) who had tried to

keep up with the procession.

The train stopped when the

waggon carrying the company surveyors and engineers lost a wheel; the waggon

was left behind and the train continued. The train stopped again, this time for

35 minutes to repair the locomotive and the train set off again, reaching

15 mph before it was welcomed by an estimated 10,000 people as it came to

a stop at the Darlington branch junction.

Eight and a half miles had

been covered in two hours, and subtracting the 55 minutes accounted by the two

stops, it had travelled at an average speed of 8 mph. Six waggons of coal

were distributed to the poor, workers stopped for refreshments and many of the

passengers from Brusselton alighted at Darlington, to

be replaced by others.

Two waggons for the Yarm

Band were attached, and at 12:30pm the locomotive started for Stockton, now

hauling 31 vehicles with 550 passengers. On the 5 miles of nearly level track

east of Darlington the train struggled to reach more than 4 mph. At Eaglescliffe near Yarm crowds

waited for the train to cross the Stockton to Yarm turnpike. Approaching

Stockton, running alongside the turnpike as it skirted the western edge

of Preston Park, it gained

speed and reached 15 mph again, before a man clinging to the outside of a

waggon fell off and his foot was crushed by the following vehicle. As work on

the final section of track to Stockton's quayside was still ongoing, the train

halted at the temporary passenger terminus at St John's Well 3 hours, 7 minutes

after leaving Darlington. The opening ceremony was considered a success and

that evening 102 people sat down to a celebratory dinner at the Town Hall.

The railway

that opened in September 1825 was 25 miles long and ran from Phoenix Pit, Old Etherley Colliery, to Cottage Row, Stockton; there was also

a ½ mile branch to the depot at Darlington, ½ mile of the

Hagger Leases branch, and a ¾ mile branch to Yarm. Most of the track

used 28 pounds per yard malleable iron rails, and 4 miles of 57 ½

lb/yd cast iron rails were used for junctions. The line was single track

with four passing loops each mile; square sleepers supported each rail

separately so that horses could walk between them.

Stone was used for the

sleepers to the west of Darlington and oak to the east; Stephenson would have

preferred all of them to have been stone, but the transport cost was too high

as they were quarried in the Auckland area. The railway opened with the company

owing money and unable to raise further loans; Pease advanced money twice early

in 1826 so the workers could be paid.

1827

By August 1827 the company

had paid its debts and was able to raise more money. That month the Black Boy

branch opened and construction began on the Croft and Hagger Leases branches.

During 1827 shares rose from £120 at the start to £160 at the end.

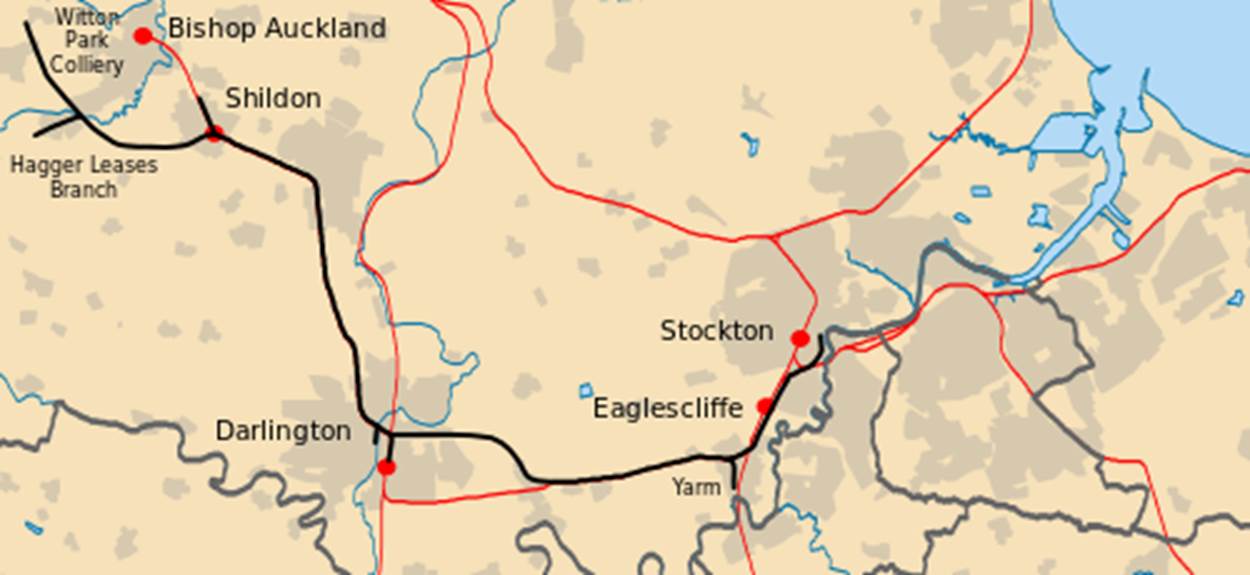

The route of the Stockton &

Darlington Railway in 1827, shown in black, with today's railway lines shown in

red

Initially the line was used

to carry coal to Darlington and Stockton, carrying 10,000 tons in the

first three months and earning nearly £2,000. In Stockton the price of coal

dropped from 18 to 12 shillings, and by the beginning of 1827

was 8 shillings 6 pence (8s

6d). Initially the drivers had been paid a daily wage, but after February

1826 they were paid ¼ d per ton per mile; from this they had to pay

assistants and fireman and to buy coal for the locomotive.

The 1821 Act had received

opposition from the owners of collieries on the River Wear who

supplied London and feared competition, and it had been necessary to restrict

the rate for transporting coal destined for ships to ½ d per ton per

mile, which had been assumed would make the business uneconomic. There was

interest from London for 100,000 tons a year, so the company began

investigations in September 1825.

In January 1826 the first staith opened at Stockton, designed so waggons over a

ship's hold could discharge coal from the bottom. A little over 18,500

tons of coal was transported to ships in the year ending June 1827 and this

increased to over 52,000 tons the following year, 44 ½ per

cent of the total carried.

The locomotives were

unreliable at first. Soon after opening, Locomotion No. 1 broke a

wheel, and it was not ready for traffic until 12 or 13 October. Hope,

the second locomotive, arrived in November 1825 but needed a week to ready it

for the line. The cast-iron wheels were a source of trouble. Two more

locomotives of a similar design arrived in 1826; that August 16s 9d was spent

on ale to motivate the men maintaining the engines. By the end of 1827 the

company had also bought Chittaprat from

Robert Wilson and Experiment from Stephenson. Timothy

Hackworth, locomotive superintendent, used the boiler from the

unsuccessful Chittaprat to build the Royal

George in the works at Shildon and it started work at the end of

November. John Wesley Hackworth later published an account stating

that locomotives would have been abandoned were it not for the fact that Pease

and Thomas Richardson were partners with Stephenson in the Newcastle works, and

that when Timothy Hackworth was commissioned to rebuild Chittaprat it was "as a last experiment"

to "make an engine in his own way". Both Tomlinson and

Rolt stated this claim was unfounded and the company had shown earlier

that locomotives were superior to horses, Tomlinson showing that coal was being

moved using locomotives at half the cost of horses. Robert Young states

that the company was unsure as to the real costs as they reported to

shareholders in 1828 that the saving using locomotives was 30 per cent. Young

also showed that Pease and Richardson were both concerned about their

investment in the Newcastle works and Pease unsuccessfully tried to sell his

share to George Stephenson.

New locomotives were

ordered from Stephenson's, but the first was too heavy when it arrived in

February 1828. It was rebuilt with six wheels and hailed as a great

improvement, Hackworth being told to convert the remaining locomotives as soon

as possible. In 1828 two locomotive boilers exploded within four months, both

killing the driver and both due to the safety valves being left fixed down

while the engine was stationary. Horses were also used on the line, and

they could haul up to four waggons. The dandy cart was

introduced in mid 1828: a small cart at the end of the

train, this carried the horse downhill, allowing it to rest and the train to

run at higher speed. The S&DR made their use compulsory from November 1828.

Passenger traffic started

on 10 October 1825, after the required licence was purchased, using

the Experiment coach hauled by a horse. The coach was initially

timetabled to travel from Stockton to Darlington in two hours, with a fare of

1s, and made a return journey four days a week and a one-way journey on

Tuesdays and Saturdays.

In April 1826 the

operation of the coach was contracted for £200 a year; by then the timetabled

journey time had been reduced to 1 ¼ hours and passengers were

allowed to travel on the outside for 9d. A more comfortable coach, Express,

started the same month and charged 1s 6d for travel inside. Innkeepers

began running coaches, two to Shildon from July, and the Union, which

served the Yarm branch from 16 October. There were no stations. In

Darlington the coaches picked up passengers near the north road crossing,

whereas in Stockton they picked up at different places on the quay.

Between 30,000 and 40,000

passengers were carried between July 1826 and June 1827.

Links, texts and books