The Family members who served in the

First World War

The story of the many soldiers from

the family who took up arms in the First World War

The male members of the family who

happen to have been born between about 1890 and 1900, were, in all probability,

destined for the horrors of industrial war in the second decade of the

twentieth century. A table of those who served summarises the

forty members of our family, who served in the First World War.

Rudyard Kipling, after the death of

his son at the Battle of Loos, mourned If any question why we died, Tell

them, because our fathers lied. Wilfred Owen denounced the Roman poet Horace’s patriotic maxim, Dulce et decorum est pro patria mori, It is sweet and fitting to die

for one's country as the old Lie. The Great War still haunts the

British memory. 750,000 lives, one in three of all British males aged 19 to 22

in 1914, were lost and nine million soldiers died in Europe. It was a struggle

for freedom, and HG Wells’ War that would end all wars.

There was certainly heroism. For all

the horrors, there were acts of self-sacrifice, often by soldiers who just

happened to be born at a certain time, and to find themselves in a certain

place. This part of our family story is a poignant one and the actions and

memories of these members of our family, some of whom did not have the chance

to live longer lives, are an integral part of this history. It was Charles

Dickens in a Tale of Two Cities, who wrote, I see the lives for which

I lay down my life, peaceful, useful, prosperous and happy, in that England

which I shall see no more. It is a far, far better thing that I do, than I have

ever done; it is a far, far better rest that I go to than I have ever known.

Robert Laurence Binyon (1869-1943) wrote They shall grow not old, as we that

are left grow old, Age shall not weary them, nor the years condemn. At the

going down of the sun and in the morning We will remember them. They mingle not

with their laughing comrades again; They sit no more at familiar tables of

home; They have no lot in our labour of the day-time; They sleep beyond

England's foam.

There was

little choice, but when faced with unspeakable challenges, these were ancestors

who were called on to show courage, and did so.

The Leeds

Pal

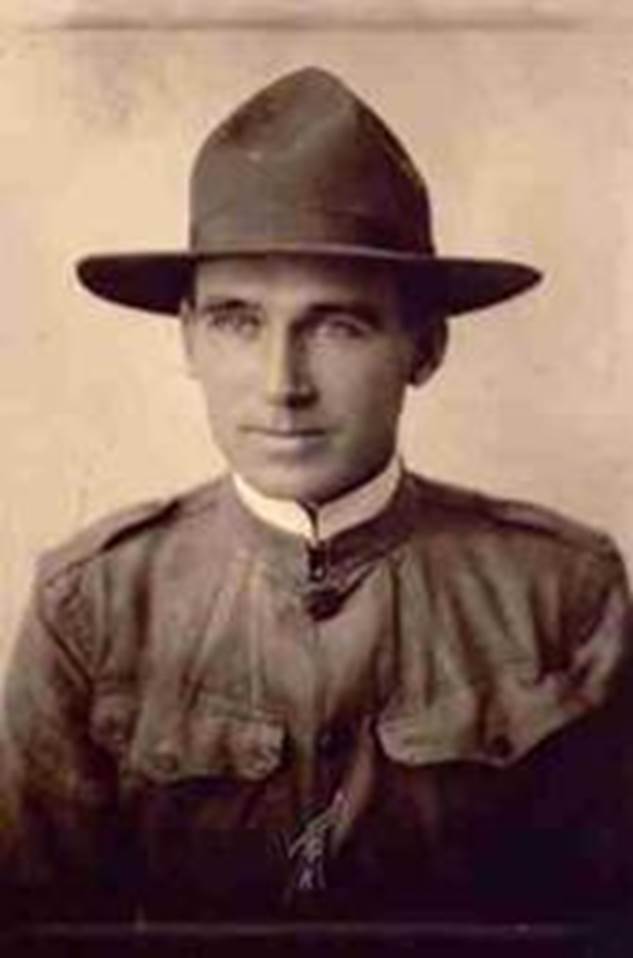

Private (later Lance Corporal) George Weighill Farndale, the son of Thomas and Mary

Hannah (nee Weighill) Farndale was born at Whitkirk,

Leeds in 1886. By 1911, he was working as a

warehouseman in the Hunslet area of Leeds. He was a member of the Colton Institute,

which is a cricket club in Leeds. He also

worked for Messrs Ashworth, Brown, and company, of St Pauls Street in Leeds who were silk and woollen goods

retailers. The family lived at Whitkirk and Colton, which are adjoining districts at the

eastern edge of modern Leeds.

George

served with 15th Battalion (1st Leeds), The Prince of Wales’s Own

(West Yorkshire Regiment), known as the Leeds Pals. The Battalion was formed in Leeds in

September 1914 by the Lord Mayor. In June 1915, the Battalion came under orders

of 93rd Brigade, and 31st Division. There were two

Bradford Pals Battalions that made up 93rd Brigade with the Leeds

Pals. In December 1915 the Battalion went to Egypt to defend the Suez Canal

from the threat of the Ottoman Empire, and then deployed to France in March 1916

to join the British build up for the Battle of the Somme. George arrived in

Egypt on 22 December 1915 before moving to France a few months later.

On the first

day on the Somme, on 1 July 1916, the 31st Division attacked towards the

village of Serre and the Leeds Pals advanced from a line of copses

named after the Gospels. The battalion was shelled in its trenches before Zero

Hour at 07.30 hours and when it advanced, it was met by heavy machine gun fire.

A few men got as far as the German barbed wire but no further. Later in the

morning the German defenders came out to clear the bodies off their wire,

killing any that were still alive. The battalion casualties, sustained in the

few minutes after Zero, were 24 officers and 504 other ranks, of which 15

officers and 233 other ranks were killed. Private A.V. Pearson, of the Leeds

Pals later wrote, the name of Serre and the date of 1st July is engraved

deep in our hearts, along with the faces of our 'Pals', a grand crowd of chaps.

We were two years in the making and ten minutes in the destroying. John Harris' novel Covenant

With Death is a fictional account of a private in the Sheffield City

Battalion from their formation until the first day of the Battle of the Somme.

George was

wounded in July 1916, presumably in the Somme offensive. He seems to have been

relatively lucky but what horrors he witnessed can only be imagined. On

Tuesday ten more wounded soldiers arrived at Portal. They are all most

cheerful. They were conveyed from Chester Station by motor cars, kindly lent by

the Honourable Mrs Marshall Brooks, Mrs Gordon Houghton, Mr Broughton, Mr G

Bebington. Sister Searl met them at the station. Another employee of Messrs

Ashworth, Brown, and company wounded is Private G W Farndale, whose home is at

Colton. His wound is in the shoulder. He is in hospital at Tarporley, Cheshire.

The hospital

at Tarporley in Cheshire, later a cottage hospital founded in 1919, was

originally a Red Cross Hospital in the First World War which had cared for

injured soldiers from October 1914 when local stalwarts the Honourable and Mrs

Marshall Brooks were determined the village should have its own hospital.

George was on a list of wounded under a Roll of Honour in August 1916, W

Yorks, Farndale (319), G.

A year

later, 15/319 Lance Corporal George Farndale was Killed in Action, aged 30, in France

on 3 May 1917, serving with the Leeds Pals. He is commemorated at Bay 4, the

Arras Memorial, France.

Among the

Leeds men who had fallen in action are the following. Lance Corporal G W

Farndale, the only son of Mr Thomas Farndale, of Colton. The Toll of War in

Yorkshire. Brave ones who have fallen in the fight. The following casualties

were also reported to Leeds men. Lance Corporal G Weighill Farndale, killed, of

Colton. Lance Corporal George W Farndale, only son of Mr and Mrs Farndale, of

Colton, died whilst on active service on April 30th. The deceased,

who was in the West Yorkshire Regiment, was well known in the district.

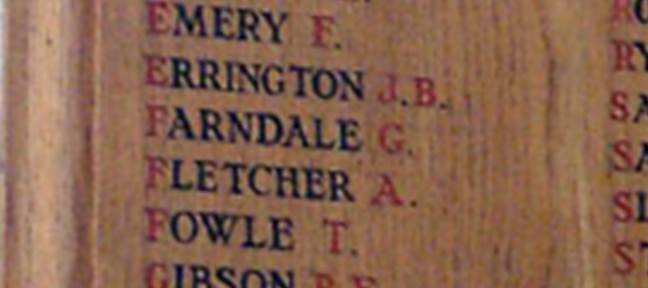

George is

listed in an

alphabetical list of the

Leeds Pals.

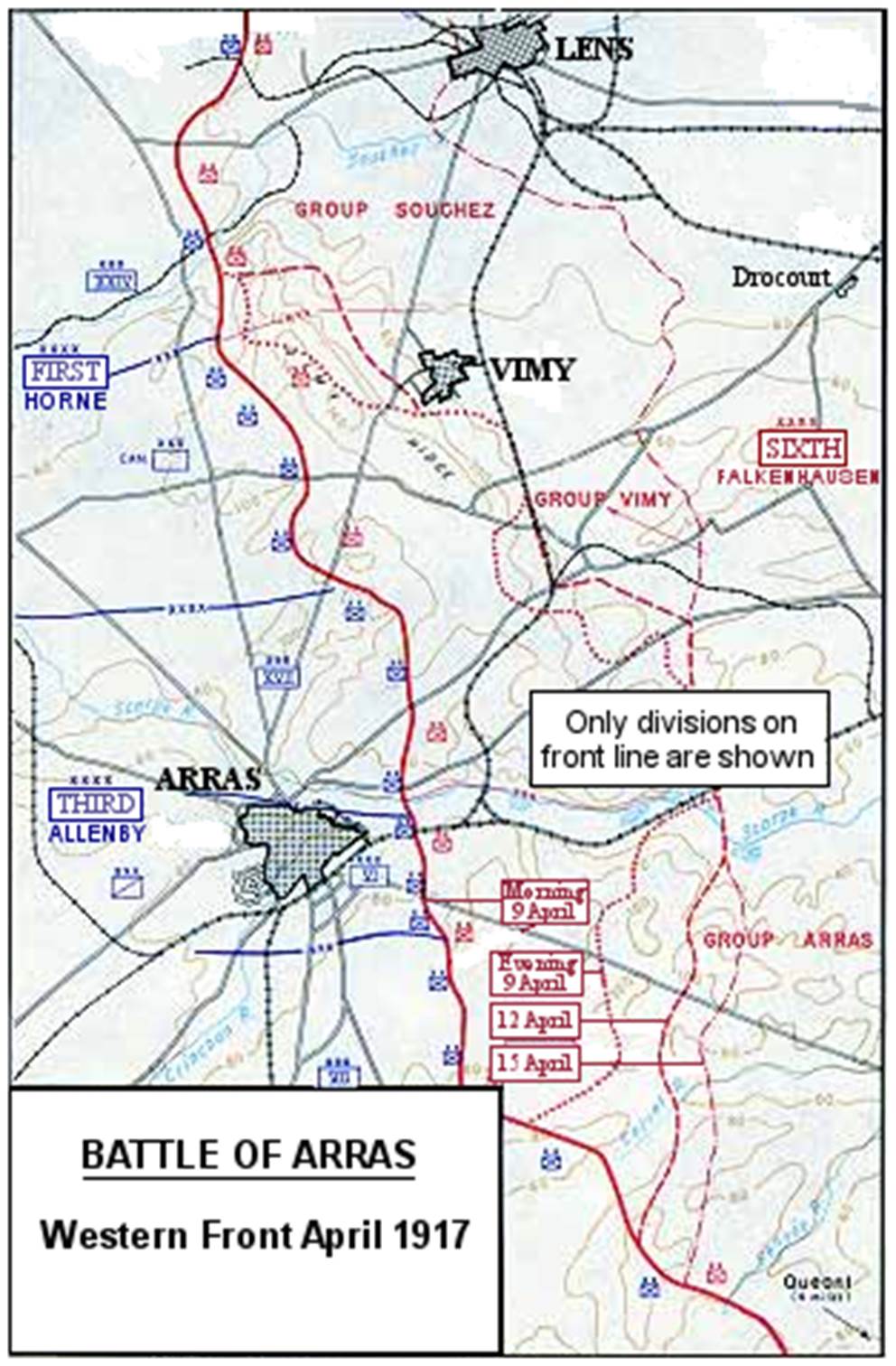

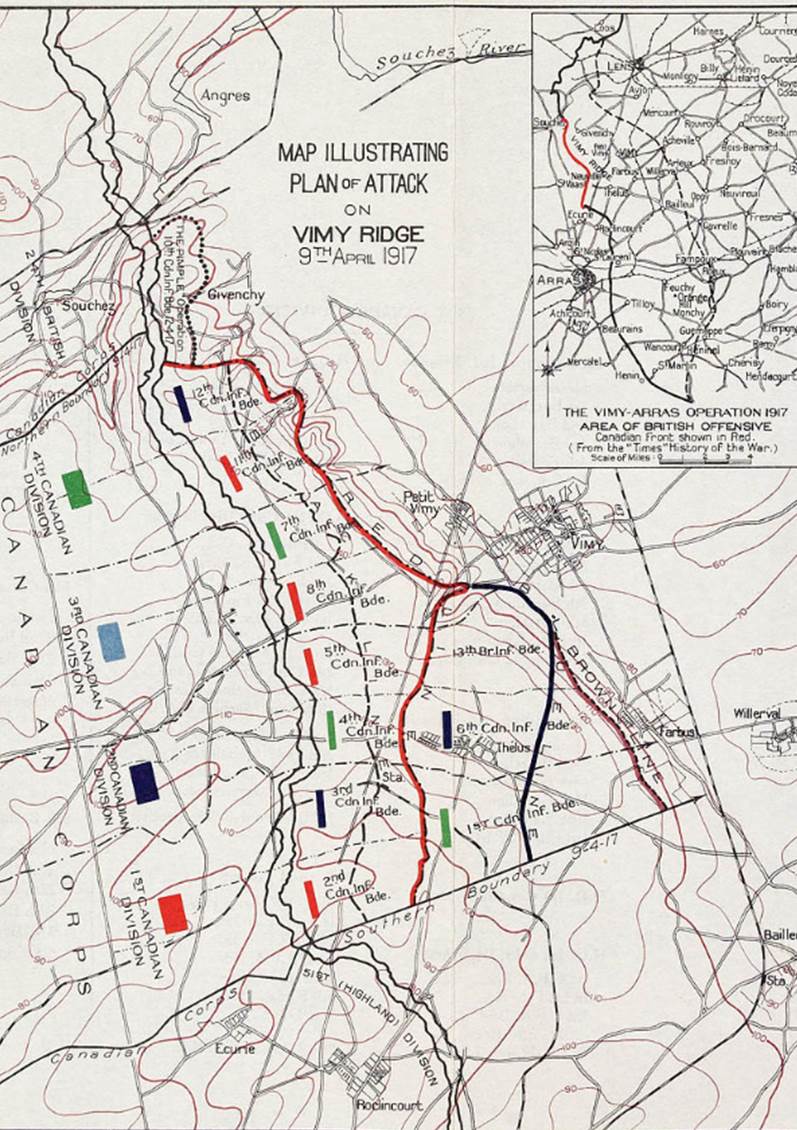

For much of

the war, the opposing armies on the Western Front had been at stalemate, with a

continuous line of trenches from the Belgian coast to the Swiss border. The

Allied objective from early 1915 was to break through the German defences into

the open ground beyond and engage the numerically inferior German Army, the Westheer, in a war of movement. The British attack at

Arras was part of the French Nivelle Offensive, the main part of which was the

Second Battle of the Aisne. The aim of the French offensive was to break

through the German defences in forty-eight hours. At Arras the Canadians were

to re-capture Vimy Ridge, dominating the Douai Plain to the east, advance

towards Cambrai and divert German reserves from the French front.

The French

handed over Arras to Commonwealth forces in the spring of 1916 and the system

of tunnels upon which the town is built were used and developed in preparation

for the major offensive planned for April 1917. The Second Battle of Arras was

the same British offensive during which George Farndale

had been killed twenty four days before his kinsman George Weighill Farndale.

From 9 April to 16 May 1917, British troops attacked German defences near the

French city of Arras on the Western Front. The British achieved the longest

advance since trench warfare had begun, surpassing the record set by the French

Sixth Army on 1 July 1916. The British advance slowed in the next few days and

the German defence recovered. The battle became a costly stalemate for both

sides and by the end of the battle, the British Third and First Army had

suffered about 160,000 and the German 6th Army about 125,000 casualties.

The British

effort was an assault on a relatively broad front between Vimy In the

north-west and Bullecourt to the south-east. After a long preparatory

bombardment, the Canadian Corps of the First Army in the north fought the

Battle of Vimy Ridge and took the ridge. The Third Army in the centre advanced

astride the Scarpe River and in the south, the British Fifth Army attacked the

Hindenburg Line, Siegfriedstellung, but made

few gains. The British armies then engaged in a series of small operations to

consolidate the new positions. Although these battles were generally successful

in achieving limited aims, they came at considerable cost.

The Third

Battle of the Scarpe took place on 3 to 4 May 1917. Having survived the Somme

offensive, George was ordered forward once again. After securing the area

around Arleux at the end of April, the British

determined to launch another attack east from Monchy to try to break through

the Boiry Riegel and reach the Wotanstellung,

a major German defensive fortification. This was scheduled to coincide with the

Australian attack at Bullecourt to present the Germans with a two–pronged

assault. British commanders hoped that success in this venture would force the

Germans to retreat further to the east. With this objective in mind, the

British launched another attack near the Scarpe on 3 May. However, neither

prong was able to make any significant advances and the attack was called off

the following day after incurring heavy casualties. Although this battle was a

failure, the British learned important lessons about the need for close liaison

between tanks, infantry and artillery, which they would use in the Battle of

Cambrai, 1917.

Front

lines at Arras prior to the attack

The Third

Battle of the Scarpe on 3 to 4 May 1917 was an unmitigated disaster for the

British Army which suffered nearly 6,000 men killed for little material gain.

First

Battle of Scarpe

The Arras Offensive

When the

battle officially ended on 16 May, the British had made significant advances

but had been unable to achieve a breakthrough. New tactics and the equipment to

exploit them had been used. To some extent, the British had absorbed the

lessons of the Battle of the Somme. They had learnt how to mount set-piece

attacks against fortified field defences. After the Second Battle of Bullecourt

between 3 and 17 May 1917, the Arras sector became a quiet front, that typified

most of the war in the west, except for attacks on the Hindenburg Line and

around Lens, culminating in the Canadian Battle of Hill 70 from 15 to 25

August.

George

Weighill Farndale was awarded the Victory Medal, British war Medal, 15

Star. He is buried and commemorated at the Arras Memorial, Pas de Calais,

France. The Arras Memorial is in the Faubourg-d’Amiens

Cemetery, which is in the Boulevard du General de Gaulle in the western part of

the town of Arras. The cemetery is near the Citadel, about two kilometres west

of the railway station.

The

Commonwealth section of the Faubourg-d’Amiens

Cemetery was begun in March 1916, behind the French military cemetery

established earlier. It continued to be used by field ambulances and fighting

units until November 1918. The cemetery was enlarged after the Armistice when

graves were brought in from the battlefields and from two smaller cemeteries in

the vicinity. The cemetery contains 2,651 Commonwealth burials of the First

World War.

The Arras

Memorial commemorates almost 34,738 servicemen from the United Kingdom, South

Africa and New Zealand who died in the Arras sector between the spring of 1916

and 7 August 1918 and have no known grave. The main events of this period were

the Arras offensive of April to May 1917, and the German attack in the spring

of 1918.

George W

Farndale, is also remembered on the Memorial, St Mary the Virgin Church, Whitkirk, now southeast Leeds. There is also a memorial at

Temple Newsam, West Yorkshire.

The Quiet

and Gentle Boy

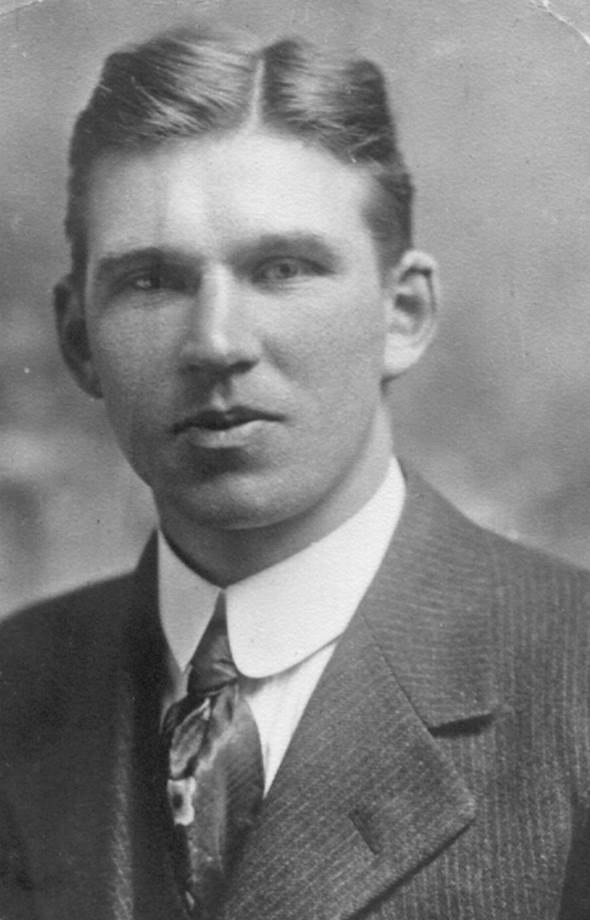

G333852 Private

George Farndale was born in Egton in

1891, the youngest son of John Farndale, a

Deputy in an ironstone mine, and Susannah, nee Smith, Farndale. The

family soon moved to Loftus, and by 1911,

then aged 20, George was a

blacksmith striker. He was an assistant to a blacksmith and his work often

involved swinging the heavy sledgehammer and striking the hot iron in the metal

forging process. He also worked for an ironmonger. He enlisted on 9 February

1916, probably into the one of the Yorkshire Regiments at Whitby, but was transferred to the Highland

Light Infantry on 1 May 1916.

On Sunday 8

April 1917, he wrote to his sister, en

route France.

Dear

Sister

Just a

line to tell you that I arrived at Folkestone at 7 o clock this morning and I

am in a rest camp now waiting of a ship. It is quite a fine place here. I think

we shall leave here at 10.45 am for the ship which I think will take us to

Boulogne where we will stay over night. I got a very

decent breakfast here and had an extra tea before we left Catterick. They also

gave us 20 packet of cigarettes each. Well tat-ta for

the present will write you again as soon as possible.

With Love

Geo

On 19 April

1917, he wrote another letter to his sister.

Dear

Sister

Received

letter on Tuesday last and parcel today. I must say the parcel was extra. The

cake is excellent, also must say that you could not have sent a more suitable

parcel. Well I must send you my sincere thanks for your kindness also for

writing to the Girl. I am sorry I had to send home for some money, but I only

get 5 francs here, and I want to get some of those French cards to send you as

I know you would like some of them. I am pleased to hear you are all keeping

well. I wrote to the Girl on Sunday so I am expecting to hear from her anytime.

Will you send me one of your photos as I would like one with me out here,

please put your name on it. Remember me to all and Give them my best respects,

also down John St. How is Father keeping hope he isn’t worrying about me as I

am alright. Well I think this is about all I have to say so I must draw to a

close thanking you once again for parcel also hoping to hear from you again

soon. Well tud-a-lu

With Love

from Your

Loving Bro Geo.

P.S. I am

not afraid about the watch and parcel, as I know the young man I left with is

honest and straight in every way, and I told him he wasn’t to go down special

with it, he was to post it anytime when he was going to town.

With Love

again

Geo.

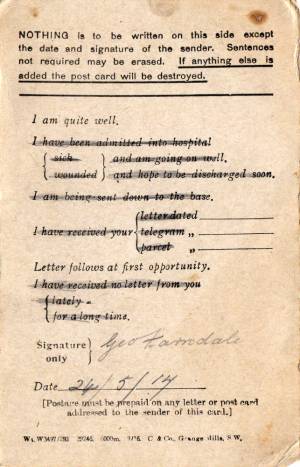

By 24 April

1917, he was expecting to move up to the front line as he wrote to his sister

again, accompanied by a standard form.

Dear

Annie

I am just

sending you a line to tell you that I am in a draft and expecting to go out any

day. If you haven’t wrote and sent the things I asked for don’t trouble, as I

may be gone before they arrive and I sharn’t be able

to take them with me. If I should be here over the weekend I will write you

again on Sunday if not I will try and send you a line before I leave. I have

got all my kit ready for going but I don’t think I shall go before Saturday or

Monday. Well be sure and don’t worry about me and

tell Father not to, as I shall be alright, and I must say before I go that you

and Father have been very kind to me as I never wanted for anything and I must

say you have done more than your duty towards me. Of course it may be weeks

before I go into the trenches as am sure to be kept at the base for a week or

two. If I should send for anything when I get to France, be sure and register

it, as it will make it more sure of me receiving it. Well don’t write any more

until you hear from me again and don’t think anything is wrong if you don’t

hear from me for a short time, but I promise you to write you as soon as I

possibly can. Well this is all I have time to say just now, so I will now

close, trusting this finds you all well. Remember me to all. Well be sure and don’t worry about me, and look on the

bright side of it as I shall soon be back again.

With

Love, From Your Loving Bro Geo

PS. If

the writing pad comes I will give it to some of the boys as it won’t be worth

sending it back. I shall very possibly be sending some shirts home.

A month

after writing to his sister, on 20 May 2017, George was involved in an attack when

we went over and took the German front line trench, which we held for 2 days

and then were relieved. He was with his mate, Private R Sellers that day.

George was

killed in action a week later on 27 May 1917, aged 26, while serving with the 1st/9th

(Territorial Glasgow Highlanders) Battalion of the Highland Light Infantry

which was part of 100th Infantry Brigade of 33rd Infantry

Division in operations against the Hindenburg Line, during the Battle of Arras,

barely a month after arriving in France. He was struck in the trenches by a

German mortar round, and killed instantly. This was twenty four days after his

kinsman, George

Weighill Farndale, had been killed in the same offensive. George was

awarded the Victory Medal and the British War Medal.

The Highland

Light Infantry Regiment raised a total of 26 Battalions, these included 3 pals

battalions which were formed as part of Lord Darby’s scheme. The Glasgow

battalions were not pals battalions and they had nicknames for each other. The

15th was the Boozy First, the 16th, the Holy

Second and the 17th, the Featherbeds. The Regiment was

awarded 65 Battle Honours and 7 Victoria Crosses losing 10,030 men during the

course of the war.

1/9th

(Glasgow Highland) Battalion Territorial force in April 1914 had been stationed

in Glasgow as part of the H.L.I. Brigade of the Lowland Division before they

moved to Dunfermline. In November 1914, they mobilised for war and landed in

France and transferred to the 5th Brigade of the 2nd

Division and engaged in various actions on the Western Front including the

Battle of Festubert and the Battle of Loos. In 1916 they were engaged at the

Battle of Albert, the Battle of Bazentin, the attacks

on High Wood, and the capture of Boritska and Dewdrop

Trenches.

Then in

1917, the Battalion took part in the First and Second Battle of the Scarpe.

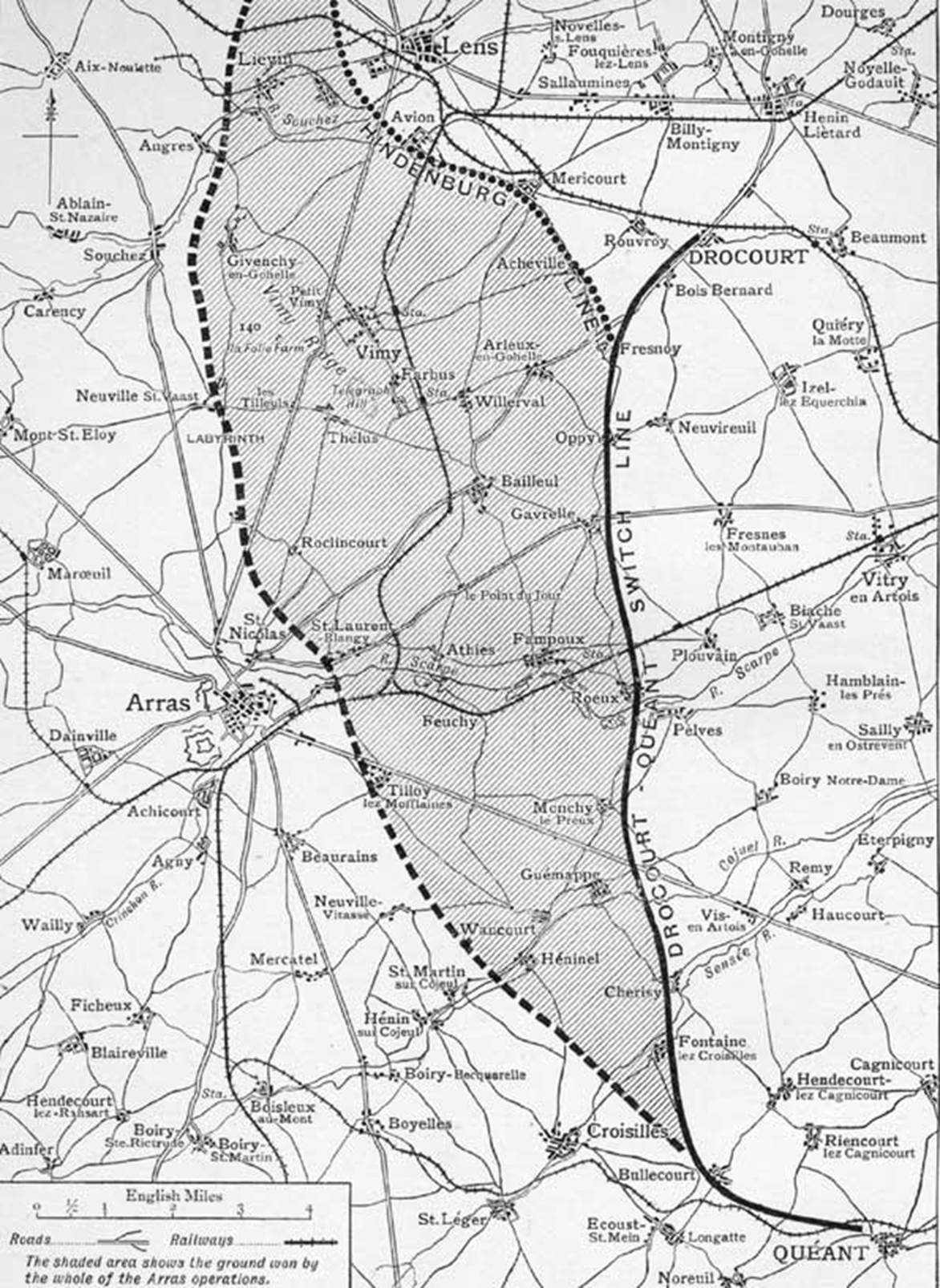

Between 9

April and 16 June 1917 the British were called upon to launch an attack in

support to a larger French offensive as part of the Arras offensive. The

opening Battle of Vimy and the First Battle of the Scarpe were encouraging, but

the offensive, often known as the Battle of Arras, soon became bogged down into

an attritional slog. Final attempts to outflank the German lines at Bullecourt

proved costly.

British

troops moving up to the trenches near Arras, 29 April 1917 The Battle of

Arras April to May 1917

George is

buried at Bay 8, Arras Memorial. He is also commemorated at the War Memorial at

East Loftus on the junction of High Street and Water Lane behind the town hall

at St Leonard’s Church, Water Lane, Loftus. Mr. John Farndale, 10, Cleveland

St, Broughton, has received official intimation that his son, Private George

Farndale, Highland Light Infantry, was killed in action on May 27th.

Previous to joining the colours he was employed by Mr J D Robinson, ironmonger,

Loftus. He was 26 years of age and enlisted on 9th February, 1916.

He had only four month’s service on the Western Front, the remainder of his

soldiering career having been spent in England.

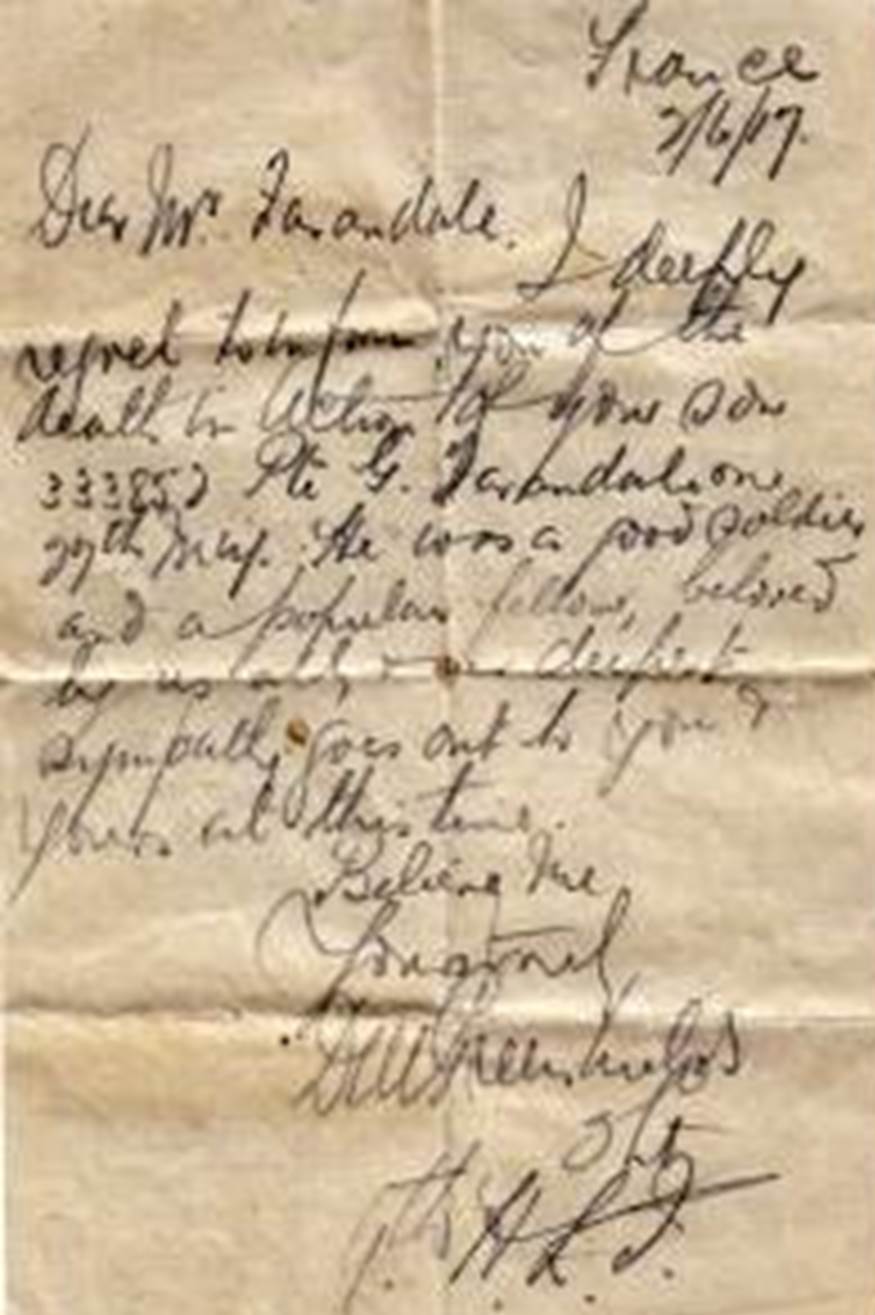

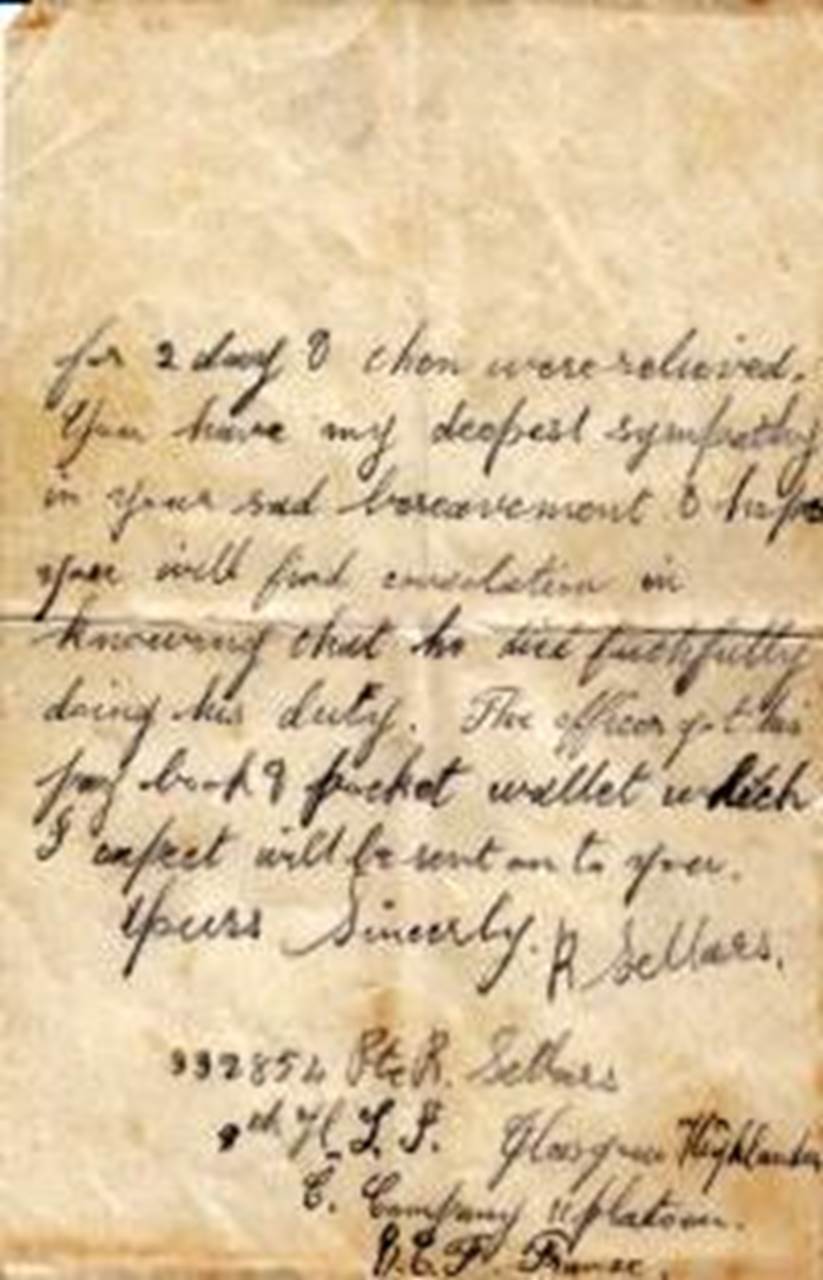

George’s

father received the news on 2 June 1917, accompanied by a rather less formal

account from one of George’s pals.

France,

2/6/17

Dear Mr Farandale

I deeply regret

to inform you of the death in Action of your son 333852 Pte G Farandale on 27th May. He was a good soldier and

a popular fellow, beloved by us all and our deepest sympathy goes out to you

and yours at this time.

Believe

me, Yours truly, D W Greenhulds, 2Lt, 9th

HLI.

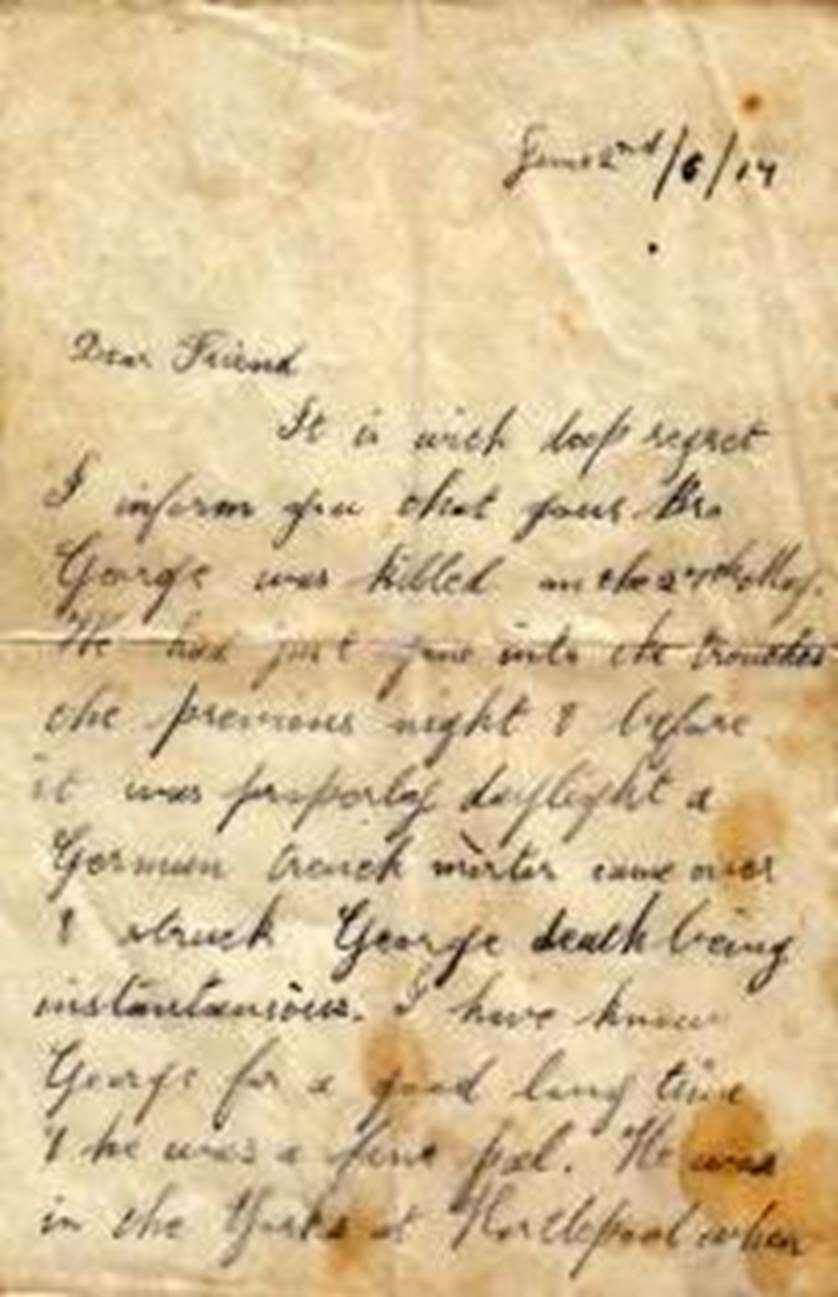

June 2nd/6/17

Dear

Friend

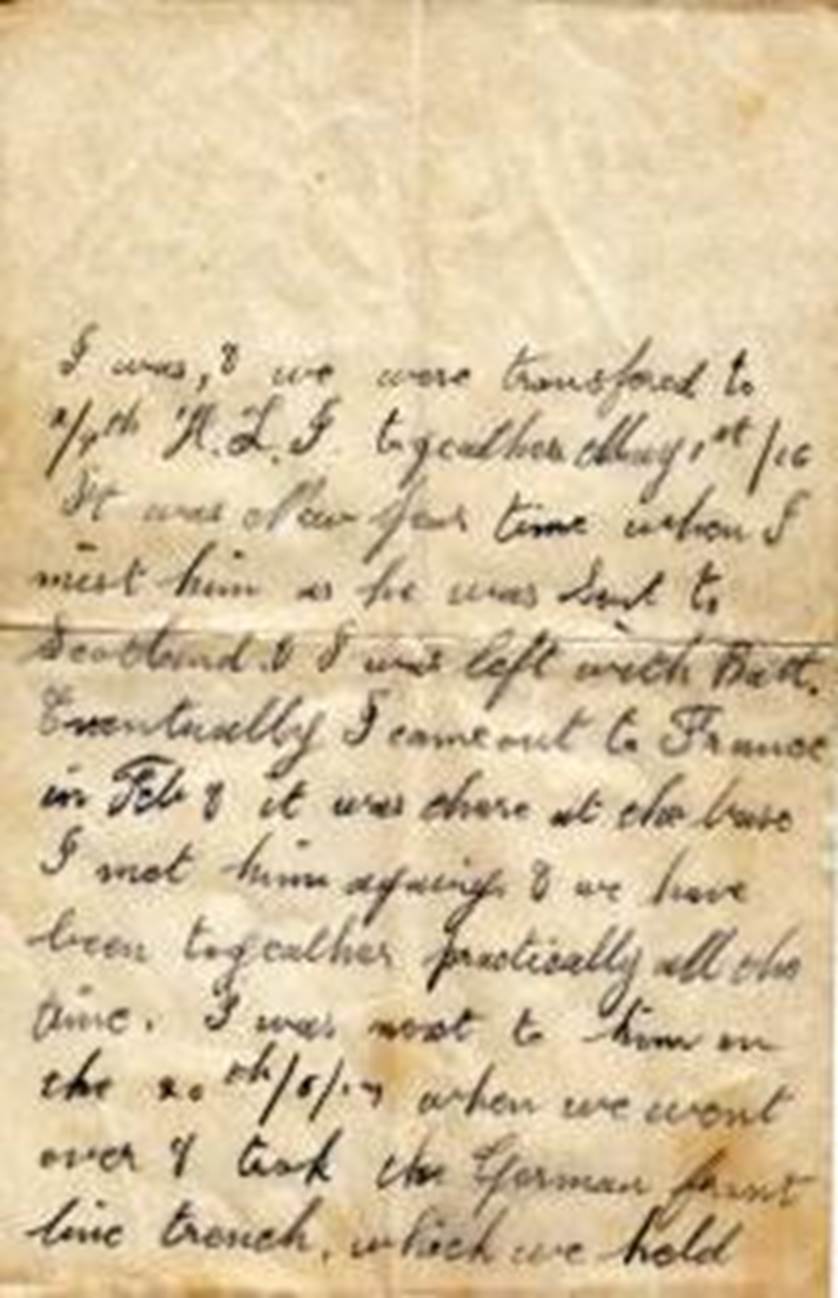

It is

with deep regret I inform you that your Bro George was killed on the 27th

May. He had just gone into the trenches the previous night and before it was

properly daylight a German trench mortar came over and struck George death

being instantaneous. I have know George for a good

long time and he was a fine pal. He was in the Yorks at Hartlepool when I was, and we were

transferred to 2/9th HLI together May 1st/16. It was New

Years time when I mist him as he was sent to Scotland

and I was left with Batt. Eventually I came out to France in Feb and it was

there at the base I met him again and we have been together practically all the

time. I was next to him on the 20th/5/17

when we went over and took the German front line trench, which we held for 2

days and then were relieved. You have my deepest sympathy in your sad

bereavement and hope you will find consolation in knowing that he died

faithfully doing his duty. The officer got his pay book and pocket wallet which

I expect will be sent on to you.

Yours

Sincerely

R Sellars

332854

Pte R Sellars 9th H.L.I. Glasgow Highlanders

C.

Company 11 platoon.

B.E.F.

France.

Another

letter followed to George’s sister. It was sent from Shingle

Hall in Hertfordshire which operated as an aircraft landing ground from

April 1916 until November 1918, and it seems that George had some involvement

with Shingle Hall before he went to France. He may have worked

there, as part of an agricultural contingent before he joined the army.

This letter was perhaps from the mysterious Girl who George referred to

in his letter of 19 April 1917, so perhaps this was a girl he had met when

working at Shingle Hall before joining the army.

Shingle

Hall, Sawbridgeworth, Herts. Thursday

Dear Miss

Farndale:-

It will

be awfully kind of you to copy those letters for me and shall be most pleased

to receive them.

Yes dear,

I will see about another doz. P.cs. being copied and

will write and let you know, as I shall be only too pleased to do anything for

you, for the sake of the dear one I have just lost.

He sent

me the Yorkshire badge (as he said no one else should have it but me) also the

cap badge of the H.L.I. and bought me a small regimental brooch of the H.L.I.

so I shall always think of the dear boy.

Now dear

Miss Farndale I will draw to a close trusting you will all accept our deepest

sympathy once more.

With

fondest love hoping to hear from you again soon

I remain

Your

sincere Friend

Dolly.

P.S.

Please excuse pencil.

The

Canadian

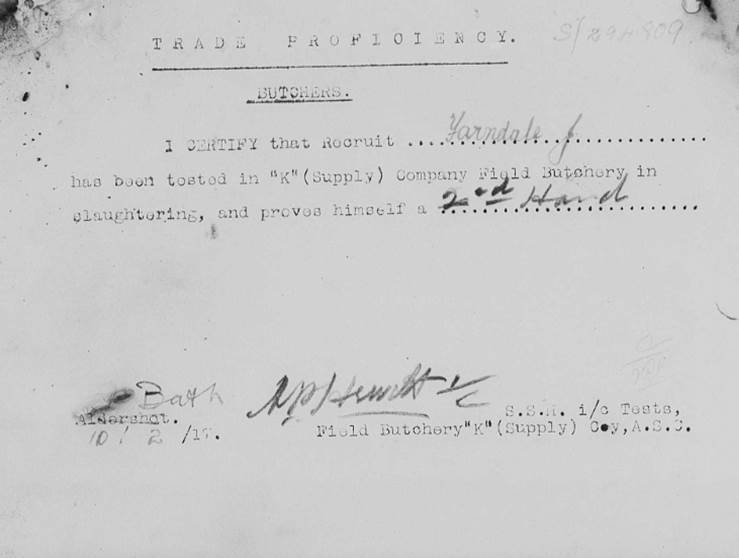

104060 Private William Farndale, was the ninth child of twelve of Martin and

Catherine Farndale, born at Tidkinhow Farm on 29 January 1892. We met the

Tidkinhow family in Act 25. He is my

great uncle. His parents called him

William after the child who had died in infancy, two years before. He left

school at 14 in 1905 and became an apprentice butcher in Saltburn with a Mr Ormsby. He then

served in a butcher's shop. Later he had a butchers shop in Charltons

which he shared with his elder brother Jim, who we will

meet again shortly. They then took another butcher’s shop in Commondale. They

began with a share in a bullock with a man in Guisborough who had a slaughter house.

Later they were selling three bullocks a week and were well remembered in their

horse drawn delivery van. His brother Alfred,

who we will also meet again shortly, remembered him at their mother's funeral

on 14 July 1911, as William consoled him.

William,

sitting on the right, with his brothers at Tidkinhow in 1911. Jim is sitting on

the left. Alfred is the small boy standing between

them

William

emigrated to Alberta in Canada in about 1913, following his brothers. We met

the Alberta emigrants in Act 27. He

then moved to Earl Grey near Regina, in Saskatchewan in 1914 and continued his

trade as a butcher.

William

in about 1914

He joined the Canadian Army on 19 April 1916 at Regina, Saskatchewan and went to

France. He served with the Canadian Army, with the 28th Saskatchewan Regiment.

28th

Battalion (Northwest) of the Canadian Expeditionary Force was authorised on 7

November 1914 and embarked for Britain on 29 May 1915. It disembarked in France

on 18 September 1915, where it fought as part of the 6th Infantry Brigade, 2nd

Canadian Division, in France and Flanders until the end of the war. The

Battalion originally recruited in Saskatoon, Regina, Moose Jaw and Prince

Albert, Saskatchewan and Fort William and Port Arthur, now Thunder Bay, Ontario

and was mobilised at Winnipeg, Manitoba.

His younger brother Alfred, who he has consoled at their mother’s funeral in 1911, had already

joined to British Army in late 1915, though strictly, he was a little younger

than he should have been. His older brother, Jim, who had moved on from Canada to the United States, joined the US Army

in 1917, shortly after the USA joined to conflict. Three brothers, served in

three different armies, for the common cause.

William was wounded in action at Vimy Ridge on 13 December

1916 while serving with the 28th Battalion. He took a gunshot wound in the

right forearm and

was in hospital in Epsom, in England. The Ottowa

press on 19 December 1916 reported simply, Wounded, Pte W Farndale, England.

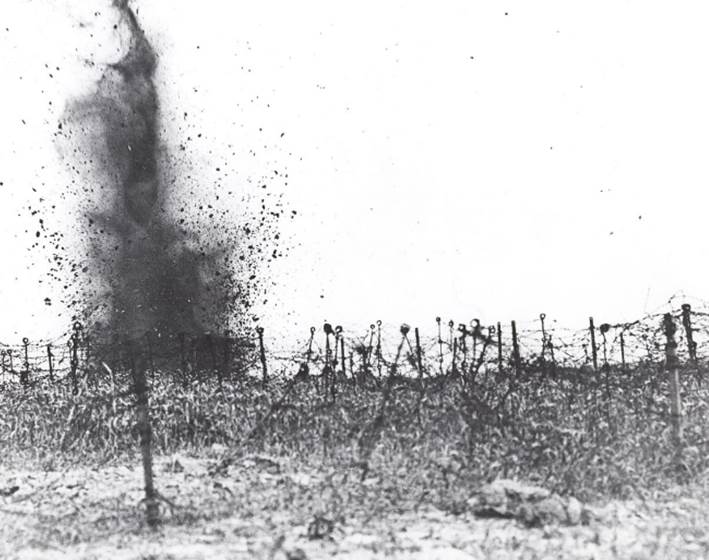

The

strategic escarpment known as Vimy Ridge was a focus of fighting from early in

the War. In 1915, the French suffered some 150,000 casualties in their attempts

to gain control of Vimy Ridge and surrounding territory. The French Tenth Army

was relieved in February 1916 by the British when the French transferred to

join in the Battle of Verdun. The British soon discovered that German

tunnelling companies had taken advantage of the relative calm on the surface to

build an extensive network of tunnels and deep mines from which they would

attack allied positions by setting off explosive charges underneath their

trenches. The Royal Engineers sent specialist tunnelling companies to the ridge

to combat the German mining operations and German artillery and trench mortar

fire intensified in early May 1916.

The Canadian

Corps relieved IV Corps along the western slopes of Vimy Ridge in October 1916.

On 28 May 1916, Lieutenant-General Sir Julian Byng took command of the Canadian

Corps from Lieutenant-General Sir Edwin Alderson. Discussions for a spring

offensive near Arras began, following a formal conference of corps commanders

held at the First Army Headquarters on 21 November 1916.

Trench

raiding involved making small-scale surprise attacks on enemy positions, often

in the middle of the night for reasons of stealth. All belligerents employed

trench raiding as a tactic to harass their enemy and gain intelligence. In the

Canadian Corps trench raiding developed into a training and leadership-building

mechanism. The size of a raid would normally be anything from a few men to an

entire company, or more, depending on the size of the mission.

Artillery

fire at Vimy Ridge

When William

was wounded on 13 December 1916, he later told his sister that he had four

operations in two weeks.

In March

1917, the army HQ formally presented Byng with orders giving Vimy Ridge as the

Canadian Corps objective for the Arras Offensive. The later Battle of Vimy Ridge

fought from 9 to 12 April 1917, was part of the Battle of Arras, the same

battle where the two George Farndales later fell. The 6th Canadian

Infantry Brigade formed the leading Brigade in the assault.

The details

of his injury were later recorded. Loss of function, right arm, penetrating gun shot

wound at forearm with compound comminuted fracture of

radius, bullet entered inner surface of forearm, two inches below elbow, and

passed directly through the arm, coming out on the other side, and splintering

the radius in its passage. Severe inflammation of the arm followed, and

inflammation, and sequestrum formed and was removed. Had erysipilis

while in hospital, 23rd CC Station, 24th General Hospital (British) Etaples from 17 Jan to 23 April 1917, Reading War Hospital

from 23 April to 12 July 1917, MC Hospital Epsom, since 12 July 1917, wounds

all healed. The wound and exit wound shows the remains of a sinus from the

radius not discharging now. Has wrist drop, and is wearing a dorsiflexion

splint. Flexion and extension of elbow are greatly limited and pronation and

supination are absolutely stopped, in a position of partial supination. Is

otherwise normal.

Alfred, his younger brother, remembers asking for leave to visit

him in hospital in Exeter, but since he was under orders himself for France, he

was not allowed to go. Indeed later William went on leave to Trochu and Tidkinhow

and the family remember questioning him about France and the fact that Alfred was, by then, in Ypres.

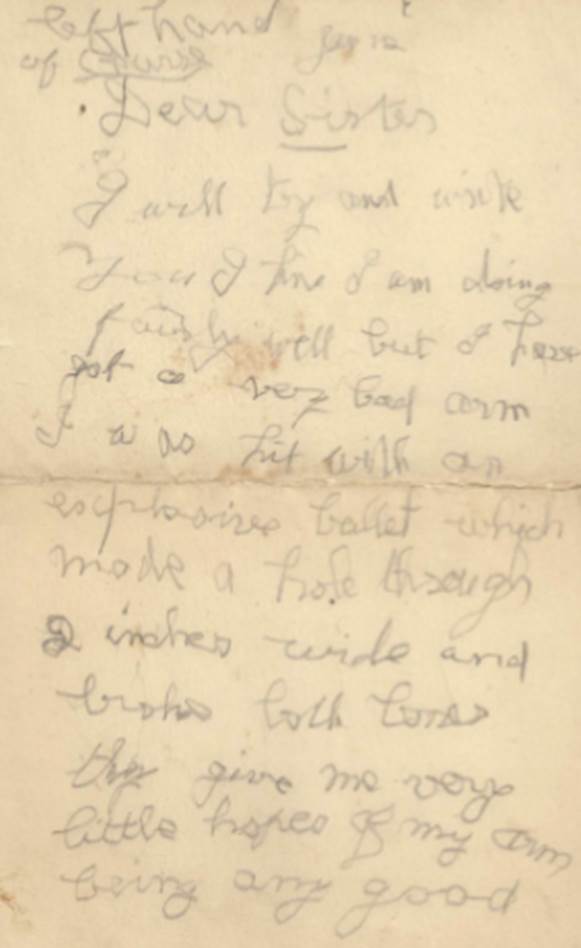

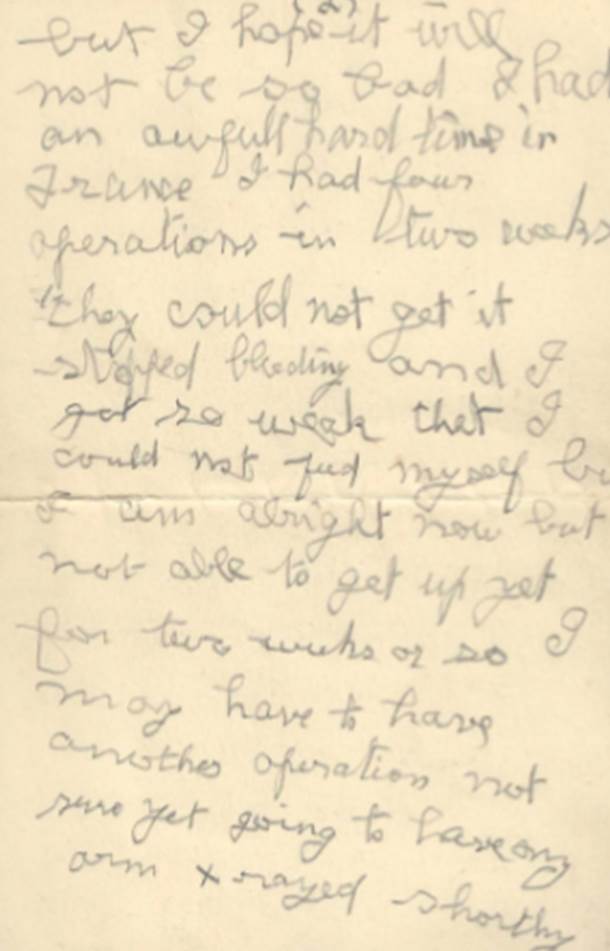

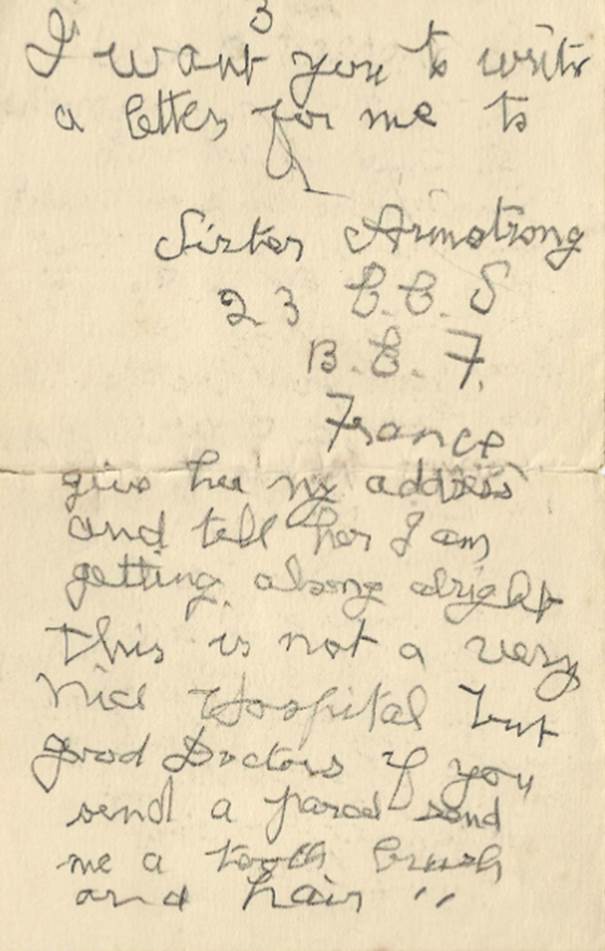

He wrote from hospital, almost certainly in 1917, to his

sister Grace.

Left hand of course

Jan 12

Dear Sister

I will try and write to you. I find I

am doing fairly well but I have got a very bad arm. I was hit with an explosive

bullet which made a hole through two inches wide and broke both bones. They

give me very little hope of my arm being any good but I hope it will not be so

bad. I had an awful hard time in France. I had four operations in two weeks.

They could not get it stopped bleeding and I got so weak that I could not feed

myself. But I am alright now, but not able to get up yet for two weeks or so. I

may have to have another operation. Not sure yet. Going to have my arm x-rayed

shortly. I want you to write a letter for me to Sister Armstrong, 23 CCS, BEF,

France. Give her my address and tell her I am getting along alright. This is

not a very nice hospital, but good doctors. If you send a parcel, send me a

toothbrush and hairbrush. I expect I will be here three months. I tried to get

into Yorkshire so you could come and see me, but this is as far as I could get.

If my arm does not get better it is likely I will get sent back to Canada in

the Spring, but I will never see France any more. I am awful sorry that Alf had to go. If ever he gets to France I will want to go back again.

Your

affectionate brother

W.F.

After his return to Regina, he used

his car to take patients to hospital during the great influenza epidemic of

1918. He caught the ‘flu while still weak from his wound and died at Earl Grey,

Saskatchewan, Canada, aged 25 years on 23 November 1918. He was buried in Earl

Grey, Saskatchewan.

William had been engaged to a girl in

Earl Grey at the time of his death. She wrote to some members of the family but there was no

trace of her since.

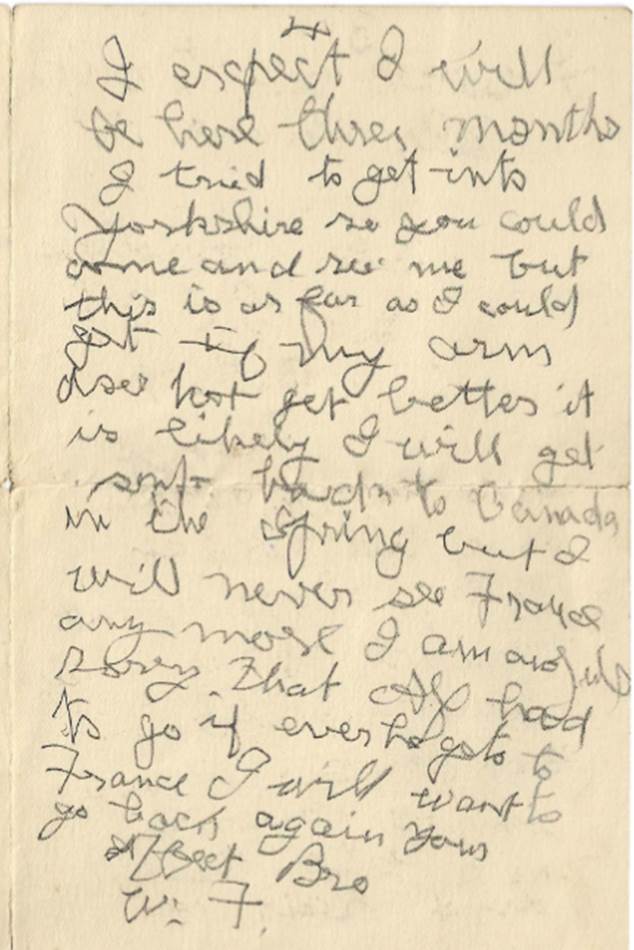

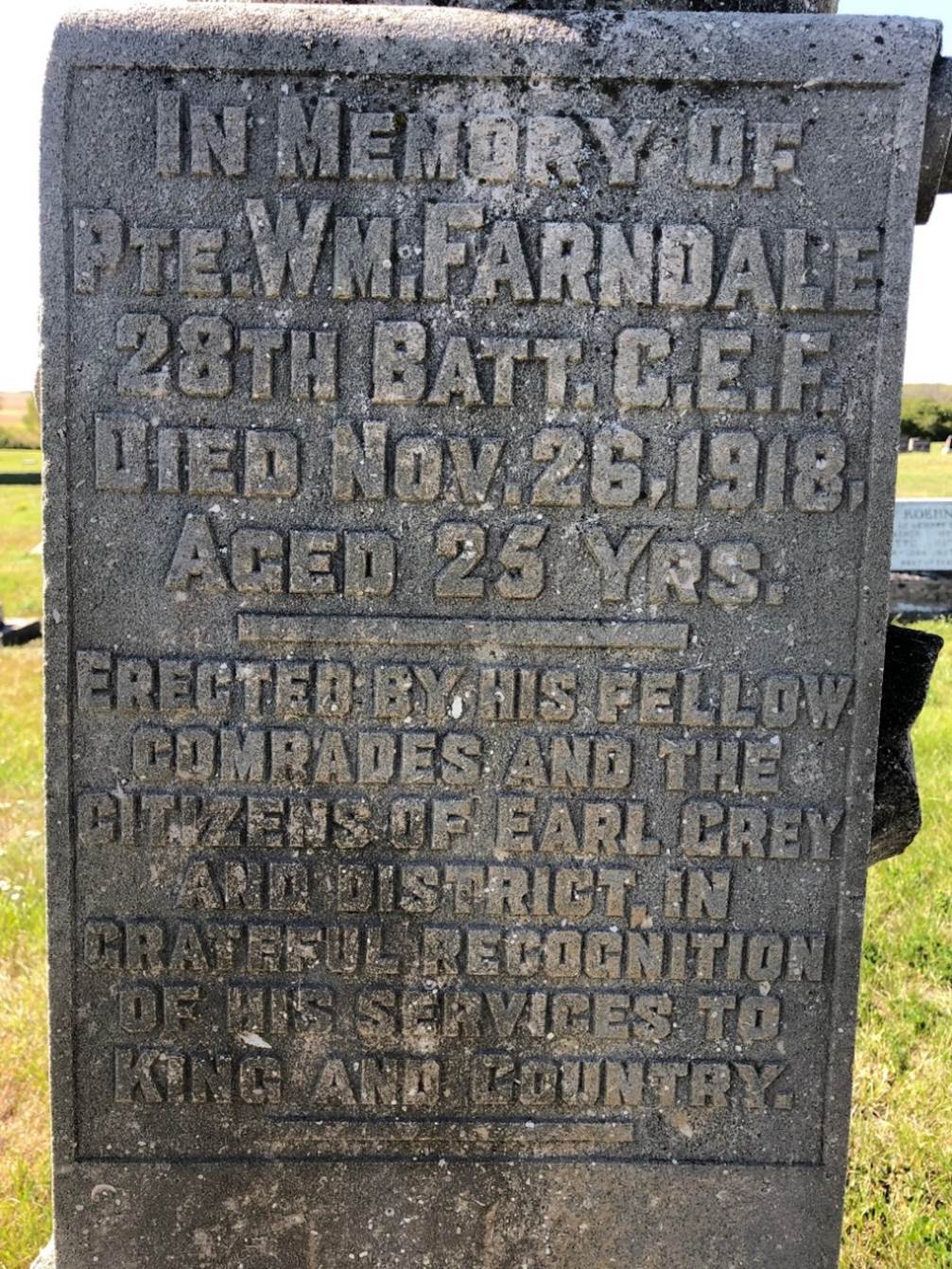

His memorial

reads, Farndale. 28th. In Memory of Pte Wm Farndale, 28th Batt. UEF. Died

Nov 26th 1918, aged 25 years. Erected by his fellow Comrades and the citizens

of Earl Grey and district, in grateful recognition of his services to King and

Country.

My

Grandfather

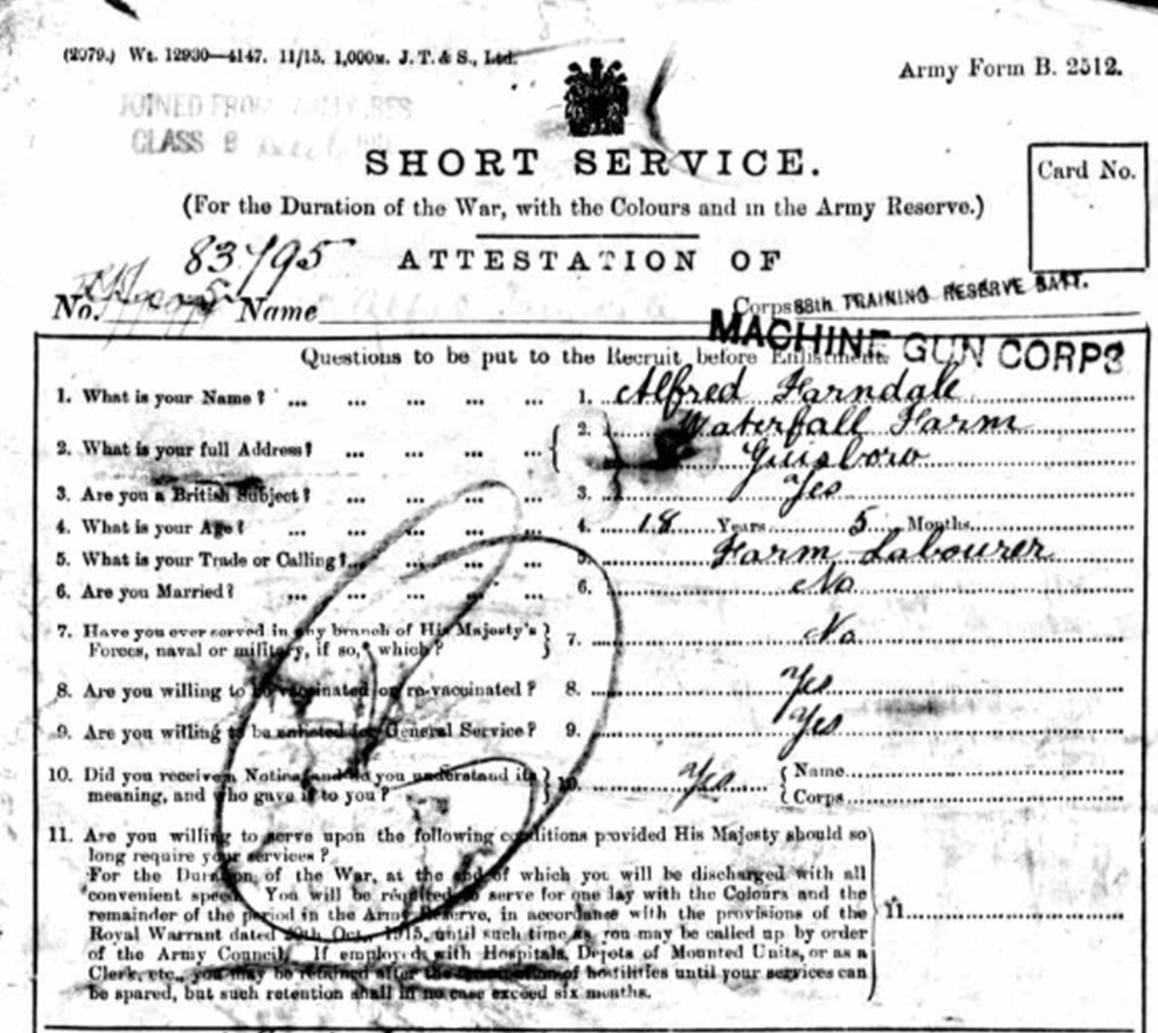

83795

Private (later Acting Sergeant) Alfred Farndale enlisted into 88th

Training Reserve Battalion at Northallerton

on 13 December 1915 and joined the East Yorkshire Regiment in 1916, but then

volunteered for the Machine-Gun Corps and served on the front line with 239th

Company at Ypres in France until mid 1917 when he

went to Mesopotamia and served in action there until the end of the war. He

served in France, Iraq and India. He saw service with the colours from 6

December 1916 to 18 March 1920, three years and three months.

He later

recalled, the war came in 1914 and I was just 17. I

wanted to join up so I ran away and joined up at the local recruiting office at

Northallerton,

somewhere in South Parade I think. I joined the West Yorks but my father found

out and said I was under age, which I was. The CO wanted me to stay on the

band, but father wouldn’t hear of it and I came out. I remember being very

proud of my first leave in uniform. Then one day they called for volunteers for

the Machine-Gun Corps and I stepped forward. We went to Belton Park, near

Grantham for training. I joined 239th Company MGC and we were

attached to the Middlesex Regiment.

Machine Gun Corps at Belton Park, Grantham in 1917

In 1917

we sailed for Calais and went to “Dickiebush” Camp. A MGC

Transferral Oder showed him proceeding to the British Expeditionary Force

in France on 12 July 1917. He embarked at Southampton on 13 July and

disembarked at Le Havre on 17 July 1917, part of 239th Company MGC

BEF 13 July 1917. His Medical

History Record showed he was 5 ft 6 ¼ inches height and 133 lbs. We were

first in action at Westbrook and Polygon Wood. He saw service with the BEF

for a three month period from 13 July to 13 October 1917.

The Battle

of Pilckem Ridge from 31 July to 2 August 1917 was

the opening attack of the Third Battle of Ypres in the First World War. In

follow on operations by 4 August 1917, the Gheluvelt

Plateau was a sea of mud, flooded shell craters, fallen trees and barbed wire.

Troops were quickly tired by rain, mud, massed artillery bombardments and lack

of food and water. A rapid relief of units spread the exhaustion through all

the infantry, despite fresh divisions taking over. The Fifth Army bombarded the

German defences from Polygon Wood to Langemarck

but the German guns concentrated their fire on the Plateau. Low cloud and rain

grounded British artillery-observation aircraft and many shells were wasted.

The 25th Division, 18th (Eastern) Division and the German

54th Division had taken over by 4 August but the German 52nd

Reserve Division was left in line; by zero hour on 10 August, both sides were

exhausted. Some troops of the 18th (Eastern) Division quickly

reached their objectives but German artillery isolated those around Inverness Copse and Glencorse Wood. German counter-attacks recaptured

the Copse and all but the north-west corner of

Glencorse Wood by nightfall. The 25th Division on the left reached

its objectives by 5:30 a.m. and rushed the Germans in Westhoek. Both

sides suffered many casualties during artillery bombardments and German

counter-attacks.

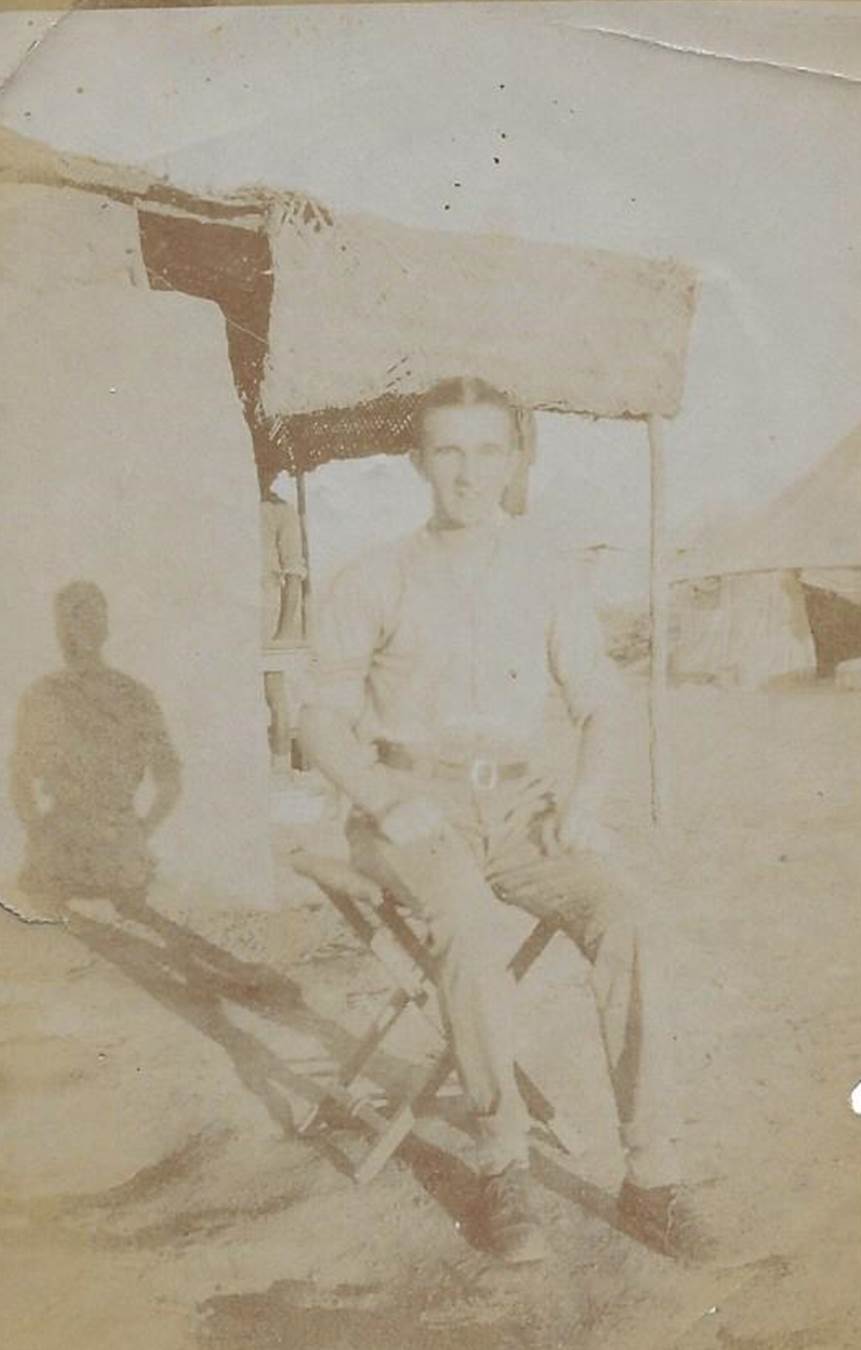

Ypres, France, 1917 (Alfred centre, rear)

I remember an incident on the Menin Road galloping up with

two limbers of ammunition towards the gun positions at Hooge. I was a Private

but I was giving a lift to Quarter Master Sergeant Zaccarelli. The Germans

started to shell us. They could clearly see us. I had one horse killed and I

managed to cut him free and I then rode the other. Zaccarelli was killed; it

was quite a party when I reported it. My Captain asked if there were any

witnesses but there were none, otherwise I might have got something. I remember

an officer coming up to me when we were under bombardment at Ypres and saying

“How would you like to be in Saltburn now, Farndale?” We saw some action

at Zonnebeke, Ploegstraat

and Arras.

Then suddenly we were ordered to

Marseilles and got on a troopship for Basra in Mesopotamia. He then saw service overseas Iraq and India from 14 October 1917 to 9 January 1920, a period of two

years and three months. His later service was recorded with 239 Company in Mesopotamia. After about 14 days we were in the Suez Canal and then the Red Sea.

We landed at Basra and marched to Kut-el-Amara as

part of a force under General Maud to relieve Townsend. About the middle of

1918 the Turks surrendered. We hung around for quite a while. I cut my thumb on

a bully beef tin and it got poisoned. I was in hospital in Kut when 239th

Company left for England. There is a record of an accidental injury and in a separate statement, he

wrote While opening a tin of canned beef on 2 February 1919 at Baiju Station

with Jack Knife, the knife slipped and cut my right thumb. A Farndale.

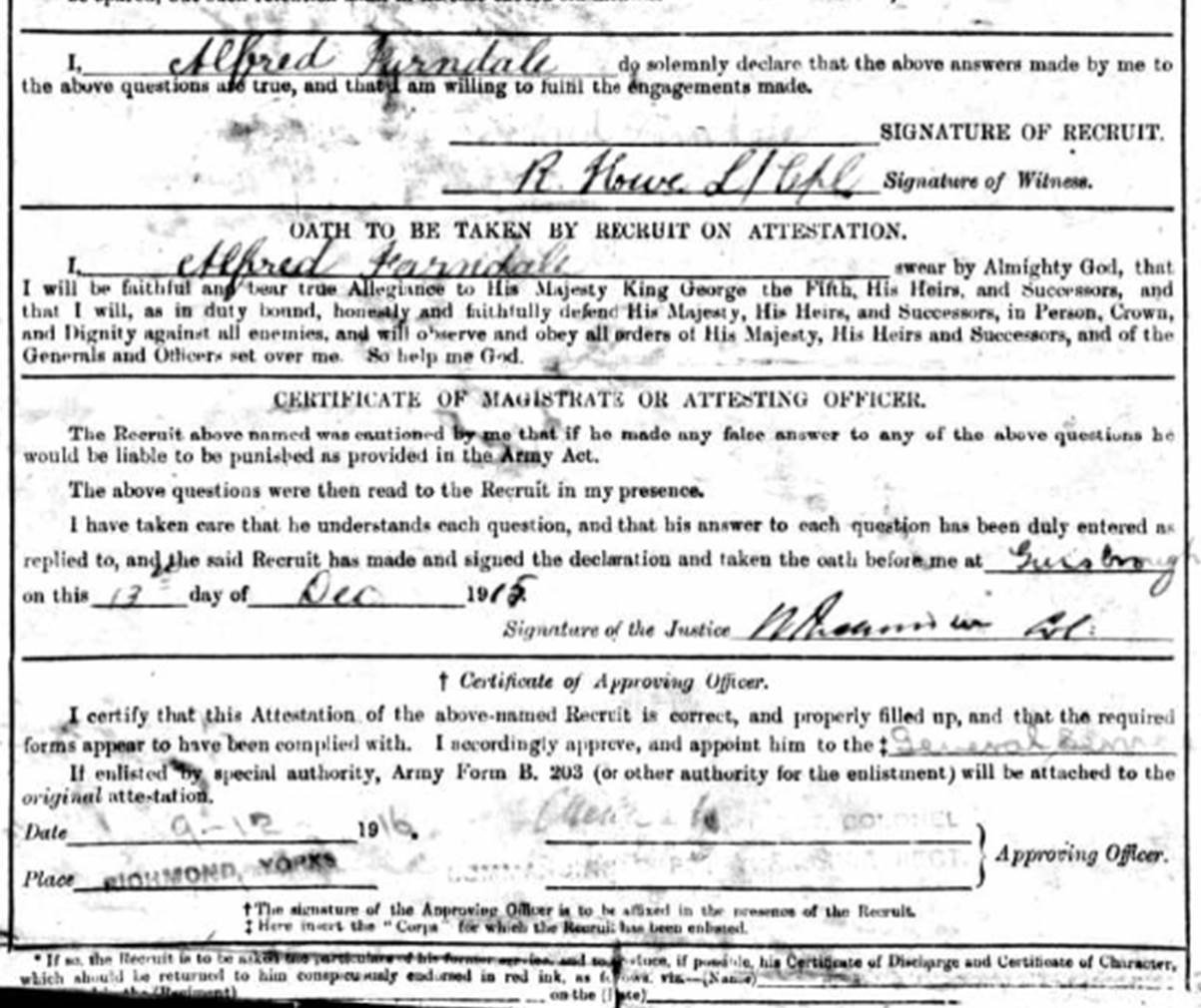

Alfred in

Mesopotamia 1917 to 1918, a corporal and a sergeant

I

eventually got to Mosul where I thought my unit was and met my platoon

commander Lieutenant Pearson. He asked me where I had been and put me in charge

of the officers mess. We had some Punjabi officers at the time and they used to

knock me up to try to get whiskey! Later in 1918 we were ordered to Bombay. He was posted to 18th

Indian Divisional Battalion 10 January 1919 and to 17th Indian

Divisional Battalion 10 January 1920.

I remember I had to take my stripes down on the troopship. We were sent

up to the Afghan frontier for a while and we had quite a lot of trouble in the

local bazaars.

Eventually

in early 1919 I think, we got a troopship to England. We landed at Southampton.

I remember we were told that we could keep our greatcoats or take £1 when we

were demobbed on Salisbury Plain. I took the £1! I remember arriving at Middlesbrough station very late at night

and sleeping on the platform. I got the first train next day to Guisborough and actually arrived at Tidkinhow before they were up! This would

be in 1919. I know that I was clear of the army by the start of 1920. I wish I

had stayed in. I really did like the army life. But I had to come out.

Alfred

transferred to Class Z Army Reserve on demobilisation on 19 March 1920 and was

discharged on 31 March 1920 on General Demobilisation. His Identify

Certificate was issued on his dispersal on 20 February 1920. His address

for pay was Tidkinhow, Boosbeck.

His (most recent) theatre of War was recorded at Mesopotamia. The place

for rejoining in case of emergency was Clipstone. He was granted 28 days

furlough from the stamp date. The standard

form completed by all soldiers regarding any disability, showed that he had

none at the time of his discharge. He was awarded the British War Medal, issued

17 March 1922 and the Victory Medal, issued 17 March 1922.

His grandson, Nigel Farndale, later wrote of his military career. For my grandfather, Private Alfred Farndale, who died

in the mud of Passchendaele, and again seventy years later in his bed. In

Farndale’s view, every man died in that battle, even those who survived. For

the dark, life-sapping shadow that descended on them all snuffed out a vital

spark. The battle raged for

100 days. More than half a million Allied troops and a quarter of a million

German were killed. The dead would be buried under a deluge of soil only to be

disinterred by the next shell, and reburied by the next. In his novel, The Blasphemer,

partly inspired by young Alfred’s traumatic experiences, Farndale vividly

brings to life the horrors young men endured. As a boy, he had listened to his

grandfather’s tales of war as they worked together on the family farm near

Leyburn. But the silences were just as memorable: “He was an affable man but

prone to dark mood swings. There were long periods, maybe three weeks at a

time, when he wouldn’t talk. I had little doubt what lay behind it, having

grown up listening to his stories of life in the trenches. It deeply affected

him,” he says.

Alfred’s

eldest son, Farndale’s uncle, went on to join the Army against his wishes

and rose to the rank of general. The fact that a former private’s son was able

to go on to claim the title General

Sir Martin Farndale, Commander-In- Chief of the British Army of the Rhine

is perhaps partly due to the social upheaval that followed the Great War.

Alfred’s beginnings were much more humble. He was the youngest of 12 children

and in a reserved occupation looking after the stock on his parents’ farm near Guisborough when, against their wishes, he

lied about his age at 17, signing up at the local Army recruitment office in

Northallerton. Despite being sent home because he was too young, he volunteered

again as soon as he was able. Alfred knew something of the realities of life on

the Front Line and would have been very aware of what he was letting himself in

for. “My grandfather had two older brothers fighting in the trenches and one

had been shot in the elbow. His distant relative George had been

killed at Arras in May 1917. There were widespread reports of the 20,000 men

killed and 40,000 injured on the first day of the Somme. It was quite a

frightening prospect.”

Alfred

certainly rose to the challenge. He was, undoubtedly, a hero, and an unsung one

at that. One of the stories he told his family, about a daring dash under fire

to deliver much needed ammunition to the Front Line, revealed an act of bravery

that had gone unnoticed in the chaos of battle. “My grandfather was haunted by

this incident,” says Farndale who, in 2007 visited the battlefield with his

father to mark the 90th anniversary of Passchendaele. “It was a

moving experience. When we came to the notorious spot known as Hellfire Corner,

we remembered the story he told us. He and Quartermaster Sergeant Zaccarelli

had been galloping up to the Front with an ammunition limber when the Germans

started to shell them. Zaccarelli was killed, along with a horse. My

grandfather managed to cut the dead horse free, drag Zaccarelli’s body into a

ditch and carry on up to the Front on one horse with his delivery of

ammunition. “It amounted to family legend because there were no witnesses or

dates, just this memorable surname. We came across a small British war cemetery

and there was the surname, only spelt slightly differently. Company

Quartermaster Sergeant John Zaccarelli died on August 28, 1917, a month into

the battle of Passchendaele. He was 27. “Until that moment we didn’t really

believe it had happened. He was a real person after all, not a myth, and when

we stood before his grave my father and I felt the hairs on the backs of our

necks rise. “It was so arbitrary; this man happened to die and my grandfather

happened to live. This meant my father had been given life, and so too had I.”

For

Farndale, visiting the site of the battlefield brought much of what his

grandfather had told him to life. He recalls Alfred explaining the complex

trench systems and the nicknames they used to describe them. As he stood there,

Farndale could even sense the smells his grandfather and comrades had to

endure, “an acrid combination of cordite, mustard, chlorine, sweat and

putrefying horseflesh,” he says. “He would tell me about the noise, which was

so loud, so deafening, it gave men mild concussion. They couldn’t even remember

their names, they weren’t able to count to three. During one particularly heavy

bombardment, his first commanding officer from the Yorkshire Regiment

recognised him. “I bet you’d rather be in Saltburn now, Farndale’,” he said.

Alfred

talked a lot about the mud. “The drainage system on this reclaimed marshland

had been destroyed by shelling. It was a landscape of mud, one big bog. As well

as constantly dodging bullets, soldiers who slipped off the slippery duckboard

walkways, just 18 inches wide, were drowned in an orange sea of bubbling,

gas-poisoned mud. It was a death trap. “In winter on the farm, when we got

stuck in deep mud, he would say ‘This was like the dry bit in Passchendaele,

dry enough to sleep on’. We talked a lot. We would go round the stock together,

singing World War One songs. I don’t think I quite got the brutality of it when

I was young, but the War seemed very immediate to me.”

Inspired

by his grandfather’s story, Farndale, 47, did more in-depth research into the

experiences of young men in the First World War. In The Blasphemer, which takes

place partly in the present day and partly in the First World War, he explores

what happens when our courage is put to the test. “My generation didn’t have

the experience of war to test our courage. That is what I wanted to explore,”

he says. He read letters and diaries written by troops in the trenches, as well

as personal accounts written after the war. “Many of them left school at 14,

but they wrote such vivid descriptions, in such beautiful handwriting. The

letters, written by 17 and 18- year-olds, were very humbling. When the last of

the veterans died, our remaining link with that war was broken. All we have now

is empathy.”

“He was

among those British troops sent to India. He ended up in Iraq and Basra for a

short time. That saved his life,” says Farndale. When he returned to England,

aged 22, Alfred was offered the choice of taking £1 or keeping his greatcoat.

He took the pound. Other than that, he had nothing. With little work around, he

farmed for a while in Canada, before returning to Yorkshire. “Things had

changed. There wasn’t the same deference,” says Farndale. “He was working in a

field once when a local aristocrat, who had managed to avoid fighting in the

war, came along and told him to open the gate. He told him to ‘open it

yourself’.”

Alfred

and his wife Peggy went on to have four children and he died in 1987, just a

few weeks short of his 90th birthday. “As I said in my dedication,

he did survive Passchendaele. But he died then as well,”

The

American

1111619 Sergeant James Farndale was the older brother of William and Alfred.

In 1915 he had left Alberta and got into Dulath High

School from where he got himself a place at Valpraiso

University in Indiana. There he met he met Edna Adams whom he married on 25

September 1917, shortly after he had enlisted into the US Army on 31 August

1917. The USA declared

war on Germany on 6 April 1917.

James in

Plymouth, Indiana in 1917 With Edna,

in uniform

He sailed

home, 1111619 Sergeant James Farndale, on the Empress of Russia, as part

of E Company Repair Unit, and arrived in New York on 17 September 1918. His

next of kin was Adelbert E Adams, a friend, and he was returning to Plymouth.

He returned to France, and on 15 July 1919, he sailed from Brest in France on

the South Carolina to an army base at Norfolk, a sergeant in the Motor

Transport Corps who served 14 Section, 309 Repair

Unit.

309th

Motor Repair Unit was part of the US Motor Transport Corps. They served as

electrical and mechanical engineers. The Motor Transport Corps was formed out of the United States

Army Quartermaster Corps on 15 August 1918, by General Order No. 75. The

American Expeditionary Force that deployed to France during World War I was in

need of an organization that could log, track and maintain all needed motor

transportation. Men needed to staff this new corps were recruited from the

skilled tradesmen working for automotive manufacturers in the US. It is

possible that Jim had been transferred to the MTC after the War, and we are not

sure about his service during the war itself.

He caught a

very bad dose of influenza from which he never fully recovered. He was

discharged from the US Army on 1 August 1919 At the end of the war, he managed

to visit Tidkinhow again. He eventually

became State Senator for Nevada.

The

Military Medal Holder

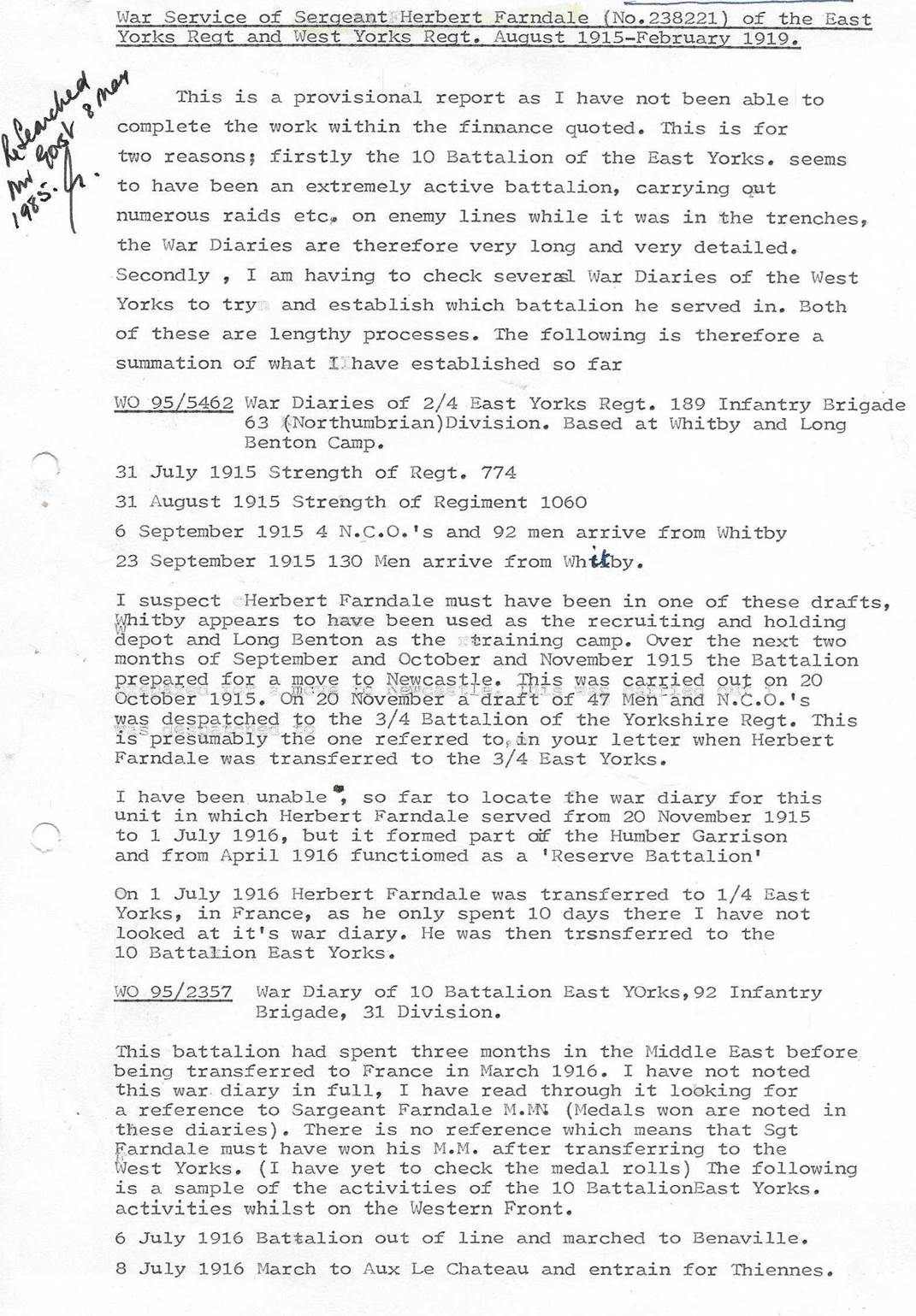

Herbert Farndale (1892 to 1971) was born on 30 March

1892, into the Craggs Hall Farm family.

Herbert

served with 2/4th Battalion of the 2nd West Yorkshire

Regiment. He first joined for duty on 11 August 1915 at Middlesbrough, with Medical Grade A1 His

medical examination on enlisted took place in Middlesbrough on 11 August 1915. He was

a farmer and 23 years old and was five foot six and a half inches high. There

is a form which he signed confirming that he was not engaged in the manufacture

of munitions for war and agreed to be inoculated.

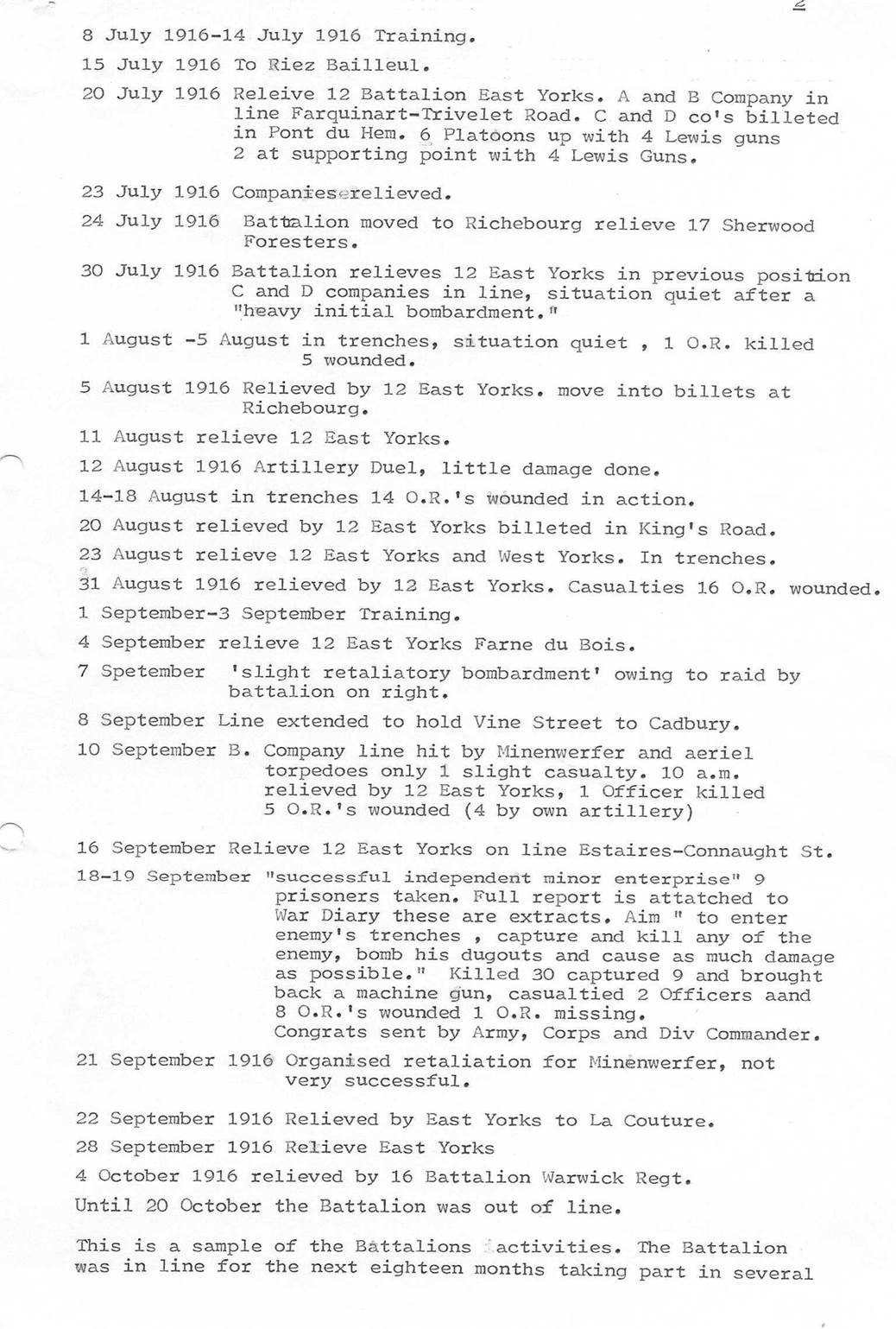

Herbert

sailed from Southampton to Le Havre on 29 and 30 June 1916. On 10 September

1916 he was posted to 10th Battalion The Yorkshire Regiment. He

joined the Battalion on 12 July 1916.

In June 1917

His Majesty the King has been graciously pleased to award the Military Medal

for bravery in the field to the under mentioned non

commissioned officers and men, 36143 Private H Farndale, Yorks Regt.

His Military Medal for bravery in the field arose for service from 11 August

1915 to 30 June 1916 and particularly on 1 July 1916, with the Expeditionary

Force in France.

On 1 July 1916, the 10th Battalion East Yorkshire

Regiment was part of the 92nd Infantry Brigade in support of the 31st

Division’s assault on the first day of the Battle of the Somme. The 10th Battalion had

trained at Wareham and was sent to France in July 1915. It saw action in and

around the Hooge and Bluff sectors and at Fricourt on

1 July, suffering enormous casualties on the opening day of the Somme offensive

in 1916. Eleven officers and 299 other ranks were killed in total.

The village

of Fricourt lay in a bend in the front line, where It

turned eastwards for three kilometres before swinging south again to the Somme

River. The XV Corps was to avoid a frontal assault and attack either side of

the village, to isolate the defenders. The 20th Brigade of the 7th

Division was to capture the west end of Mametz and swing left, creating a

defensive flank along Willow Stream, facing Fricourt

from the south, as the 22nd Brigade waited in the British front

line, ready to exploit a German retirement from the village. The 21st

Division advance was to pass north of Fricourt, to

reach the north bank of Willow Stream beyond Fricourt

and Fricourt Wood. To protect infantry from enfilade

fire from the village, the triple Tambour mines were blown beneath the Tambour

salient on the western fringe of the village, to raise a lip of earth, to

obscure the view from the village. The 21st Division made some

progress and penetrated to the rear of Fricourt and

the 50th Brigade of the 17th (Northern) Division, held

the front line opposite the village.

The 10th West Yorkshire Regiment was required to advance

close by Fricourt and suffered 733 casualties, the worst battalion losses of the day. A company from the 7th

Green Howards made an unplanned attack directly against the village and was

annihilated. Reserve Infantry Regiment 111, opposite the 21st

Division, were severely affected by the bombardment and many dug-outs were

blocked by shell explosions. One company was reduced to 80 men before the

British attack and a reinforcement party failed to get through the British

artillery-fire, taking post in Round Wood, where it was able to repulse the 64th

Brigade. The rest of the regimental reserves were used to block the route to Contalmaison. The loss of Mametz and the advance of the 21st

Division made Fricourt untenable and the garrison was

withdrawn during the night. The 17th Division occupied the village

virtually unopposed early on 2 July and took several prisoners. The 21st

Division suffered 4,256 casualties and the 50th Brigade of the 17th

Division 1,155.

The 92nd

Brigade was formed from East Yorkshire Regiment battalions and also fought on

the Western Front. Following heavy casualties in April 1918, the 92nd

and 93rd Brigades were amalgamated as the 92nd Composite

Brigade. However, they were reformed soon after.

A payment

record shows Herbert’s pay as Private from 11 August 1915, but he was posted on

20 November 1915, and was Acting Lance Corporal from 11 April 1917, and then

Lance Corporal from 17 August 1917. He was a Corporal from 12 September 1917

and Sergeant from 11 January 1918.

Herbert

Farndale wearing military medal in Green Howards Herbert Smith at officer training

unit in 1918

He was

commissioned in 1919. On

16 February 1919, 238221 Sergeant Farndale of 2/4 Yorks Regiment, was transferred

on being disembodied. This is not as bad as it sounds, but is a reference

to him transferring to be an officer cadet. Another further document on 16

February 1919 also refers to him disembodied on demobilisation but struck

off to England for admin to Cadet. To England Candidate for a Temp Commission.

On 13 May

1919 the under mentioned cadets to be temporary 2nd Lieutenants under

the provisions of the Royal Warrant dated 30 December 1918, promulgated in Army

Order 42 of 1919. West Yorkshire Regiment, 5 March 1919, Herbert Farndale, MM.

Herbert was

awarded the Military Medal as well as the Victory Medal, and British War Medal.

My grandfather, Alfred

Farndale, knew him and we have many of his papers and his medals.

The

Casualty

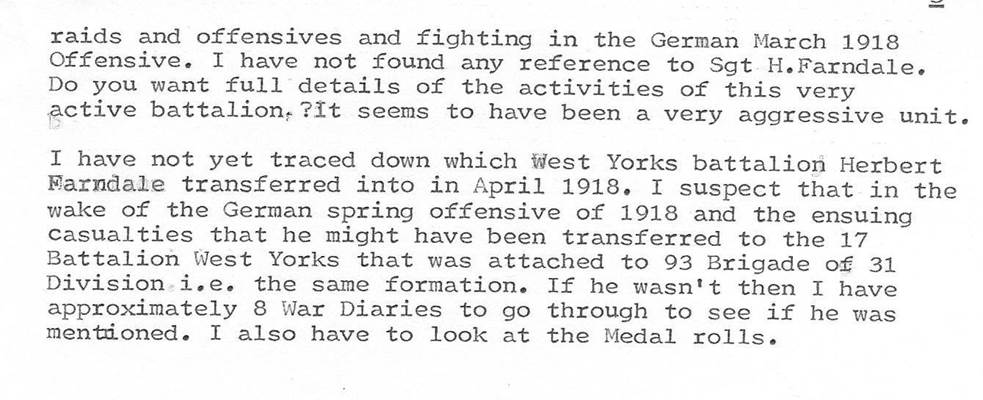

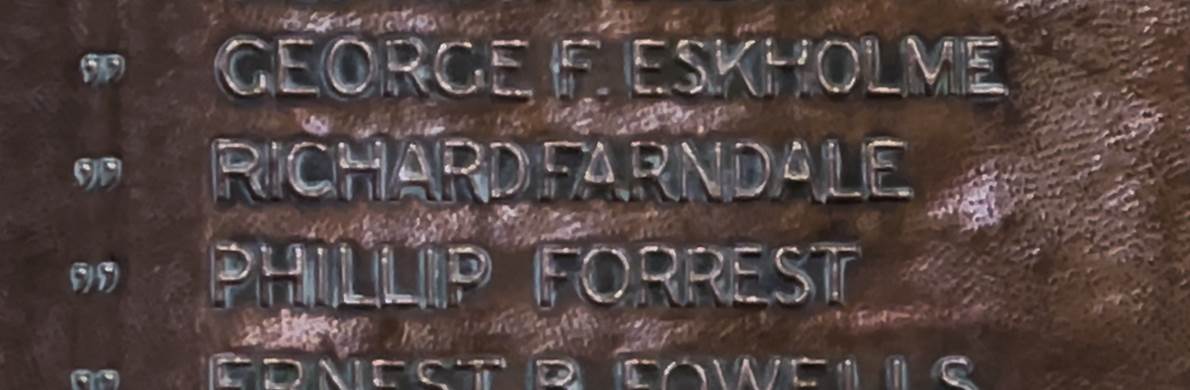

3758 and 201065 Private Richard Farndale was the son of George and Mary

(“Polly”) Farndale and born into the

Coatham Line at Coatham in 1897.

Richard joined the colours in May 1915, at the age of

eighteen. He had previously been released as unskilled labour in response to

Lord Kitchener’s request for release for munitions output. However in May 1915,

he enlisted into the 1/4th Battalion, the Princess of Wales’ Own Yorkshire Regiment, also known as the Green Howards.

The Battalion served with the 150th Infantry brigade of the

50th Division. On 31 December 1916 it had been at Bazentin le Petit and in

reserve at Flers on 7 January 1917. On 11 January

1917 the Battalion moved to the front line at Hexham Road. It was on the

front line from 30 January to 11 February 1916 at Genercourt.

The battalion moved to Proyart on 19 February 1917.

Richard died at 21st Casualty

Clearing Station in France of broncho-pneumonia on 25 February 1917. He was

presumably badly wounded at Hexham Road or Genercourt

or Proyart and evacuated to No 21 Casualty Clearing

Station at La Neuville, where he later died of pneumonia. In April 1916, No 21 Casualty Clearing Station came to La Neuville and

remained there throughout the 1916 Battles of the Somme, until March 1917.

Richard is buried at La Neuville

Communal Cemetery, Corbie, Somme. La Neuville British Cemetery was opened early in July 1916,

but burials were also made in the communal cemetery. Most of them date from

this period, but a few graves were added during the fighting on the Somme in

1918. The communal cemetery contains 186 Commonwealth burials of the First

World War. The graves form one long row on the eastern side of the cemetery.

Corbie is a village 15 kilometres south-west of Albert and about 23 kilometres

due east of Amiens. La Neuville Communal Cemetery is north of the village.

He was

awarded the British War Medal and the Victory Medal posthumously on 21 January

1921. His name is on a War Memorial at Coatham.

The gas

victim

131820 Lance Corporal William Farndale was born into the Great Ayton 2 Line on 22

January 1890. By 1911, aged 21, he was working as a joiner in Great Ayton.

At the age

of 25, on 17 November 1915, he enlisted into 235th Army Troops Company, Royal

Engineers. He was promoted to Lance Corporal, Royal Engineers Class ‘P’ AR, on

4 March 1917. He was a carpenter by trade. A record on 3 February 1917 shows

his skill as a carpenter and joiner were superior.

His service

record shows that he was in England from 17 November 1915 to 8 March 1916, with

the British Expeditionary Force in France from 9 March 1916 to 28 July 1917,

and then in England from 29 July 1917 to 19 September 1918.

A further

Active Service Form shows that he was promoted to

Corporal in March 1917 and was wounded in a gas attack in April 1917 when he

was transferred to England to 2 General Hospital.

His Medical

report shows that he was gassed with a disability originating on 12 July 1917,

but he appears to have been released for coal mining. However a

Memorandum from the Eastern Command Discharge Centre to Chatham on 1 June 1918

said This NCO having been placed in Grade II (which is equivalent to

Military Category Bi) by the Civilian Medical Board at this Centre, he is not

now eligible for transfer to the Army Reserve as a Coal Miner. AFW 3980 has

accordingly been returned to the War Office. Another Medical report

confirms he was gassed in 1917. A

continuation shows he suffered 20% disability. Consequently, he received a

pension for his gas disability. His symptoms were described in another form. He

was less than 20% disabled by the gas attack. His pension was renewed.

This was also confirmed in an Award Sheet.

On 10

January 1918 he overstayed his pass for 22 hours, but was admonished.

A record

addressed to the Eastern Command Discharge Centre at Sutton in Surrey on 16

September 1918 said Owing to the Medical Authorities being extremely busy,

this NCO could not be Boarded until this day, and he has been directed to

report to you on the 17th instant. Another record on that date at Chatham

certified William as free from contagious disease and fit to travel by train.

He received

a weekly pension of 6 shillings from 20 September 1918 to be reviewed in 52

weeks. He was transferred to the reserve on 21 September 1918.

He was

discharged from the army on 30 December 1918. The cause of discharge was Para

392 (xvia)(Gas psng).

He was

awarded the Victory Medal, British Medal and Silver Badge Roll 11 November

1919. The Silver War Badge was awarded to most servicemen and women who were

discharged from military service during the First World War, whether or not

they had served overseas. Expiry of a normal term of engagement did not count

and the most common reason for award of the badge was King’s Regulations

Paragraph 392 (xvi), meaning they had been released on account of being

permanently physically unfit. This was as often a result of sickness, disease

or uncovered physical weakness and war wounds.

Soldiers

discharged during the war because of disabilities they sustained after they had

served overseas in a theatre of operations could also receive a King’s

Certificate. Entitlement to the Silver War Badge did not necessarily entitle a

man to the award of a King’s Certificate, but those awarded a Certificate would

have been entitled to the Badge. The main purpose of the badge was to prevent

men not in uniform and without apparent disability being thought of as

shirkers. It was evidence of having presented for military service, if not

necessarily serving for long.

The

Flying Ace

The younger brother of Florence Farndale, Rev William Edward Farndale’s wife, Lieutenant Graham Price, was a World War One pilot of the Royal Army Flying Corps, killed in

action, in a duel with a German aeroplane at 8,000 feet. He had written a

letter to his parents shortly before he died, If anything happens to me do

not grieve, but feel thankful that you had a son to give to the country. In

another letter, seeming to understand his fate, he had written I would not

have been without my experiences for anything in the world, Au Revoir. His

commanding officer wrote This letter is in confirmation of the telegram of

yesterday’s date notifying you of your son’s death. It happened in a flight in

which he was observing for one of our batteries over enemy lines. His machine

was attacked by a German aeroplane and after fighting for fifteen minutes at a

height of 8,000 feet, your son received a direct hit in the heart and was

killed immediately. It was a wonderfully plucky fight against heavy odds, and

although the result was fatal for him, I know that this was the end that he

would have chosen for himself, to die fighting, hot headed, in a great fight in

the greatest of all causes. He was a very fearless and gallant officer, so dead

keen on his work and so thoroughly efficient. I feel that his loss is

irreplaceable. The Chaplain had

written Your son put up a most glorious fight, and has sacrificed himself

for his country and friends. Greater love hath no man than this, that he lay

down his life for his friends.

It was later reported Lieutenant

Graham price, the young airman who has just been killed at the front was the

youngest brother of Mrs Farndale, The Avenue, Birtley, wife of the Rev W E

Farndale, the second minister of the Chester le Street circuit. He went out to

Flanders in September, 1914, as a despatch rider, and did a lot of excellent

work. Near the end of last year he transferred to the Royal Flying Corps, and

his promotion there was very rapid, and he had already reached the rank of

pilot. He held the record of his squadron for the number of air duels he had

fought, 15. He was killed in the last fight, when he received a bullet in the

heart. He was at the time engaged in observing for the artillery over the enemy

lines.

The

Artillerymen

204344 Regimental Quarter Master Sergeant Henry Farndale, the son of John and Rose

Farndale, was born in Leeds. By the age of

27, in 1911, he was working as an engineer draughtsman in Leeds and he later worked as a shipbroker’s

clerk and became a member of the Leeds Stock Exchange. He married Grace Bell in

1913.

His

attestation on 3 December 1915 showed he was an accountant, 31 years and 11

months old, married, living at 8 Wrangthorn Avenue,

Hyde Park, Leeds. His descriptive report on enlistment shows that he was 5 ft

and 7 inches and his next of kin was his wife, Grace Elizabeth Farndale who he

had married on 27 December 1913 at Wrangthorn Church,

Leeds. The same form records that he had two children, Edward Francis

Farndale born on 14 November 1914 and Henry Stewart

Farndale, born 27 September 1916, both in Leeds. Henry was killed in the

Second World War in training as a pilot in a Tiger Moth.

There is a

record of a 204344 Gunner H Farndale, of E Battery, Royal Field Artillery,

admitted to Catterick Military Hospital on 14 January 1918. He had been

gassed. There is a record of severe gas

poisoning in his military papers. A casualty form also records that he was

gassed in about November 1917.

On 2 August

1918 was attached to a unit in London. On 10 August 1918 Acting Bombardier H

Farndale of 35th Reserve Battery RFA, 6th ‘B’ Reserve Brigade RFA was posted to

12th Brigade, 67th Divisional Artillery with effect from 9 August 1918. A War

Office letter on 10 August 1918 confirms that he was appointed as paid acting

Sergeant.

There is a

record of his movements from June 1918 to March 1919. A War Office letter dated

3 January 1919 confirms that Acting Sergeant H Farndale had been sent to RH and

RFA Records, Blackheath, Tower of London to work in connection with cost

accounting. On 20 March 1919 he was promoted to Acting Regimental Quarter

Master, for cost accounting duty at 416 Agricultural Company, Bowerham Barracks, Lancaster. There is an undated note

requesting that Acting Sergeant Farndale be traced as keen to meet. A

Special Confidential Report dated 23 October 1919 at Lancaster recommended

Henry’s promotion to the substantive rank of Warrant Officer. He had been

engaged on a Cost Accounting Scheme from 1 January 1919 and had handled the

accounts of the King’s Own Lancaster Regiment, 416 Agricultural Co, Labour

Corps, 210 TF Depot and the Prisoner of War Camp at Lancaster. He was reported

as capable and industrious, with a sound knowledge of bookkeeping.

As Acting

Regimental Quarter Master Sergeant, he sought his discharge by 21 July 1920 at

Western Command, Chester. This had also been confirmed in a letter from the

Depot at Bowerham Barracks, Lancaster on 19 May 1920.

This

followed an interesting exchange of correspondence with the War Office. On 7

May 1920, the War Office proposed the permanent transfer of Acting RQMS H

Farndale RFA to the Corps of Military Accountants, as Accountant Staff

Sergeant. He would have been required to complete seven years with the Colours,

less his mobilised service since 4 August 1914. Another letter on 7 May 1920

also seems to confirm this extension, also commenting that he should not be

rejected on medical grounds unless this would prevent him from sedentary

duties. The Form for completion for extension to the Corps of Military

Accountants dated 7 May 1920 was sent to Henry. However Henry’s reply on 11 May

1920 did not accept this extension. A Certificate of Identity issued on his

discharge and dated 15 August 1920 granted 28 days furlough and graded him in

medical category B11. He was discharged on demobilisation at Woolwich on 2

September 1920. His conduct sheet was certified no entry by the

Adjutant.

He served

with the Royal Field Artillery and was awarded the Victory Medal, and British

War Medal. He was gassed in November 1917. He was then promoted to Regimental

Quarter Master Sergeant and was engaged working on a cost accounting scheme

after the War ended. He died in Leeds in

1951.

104633

Gunner Albert Edward Farndale was born into the Loftus 2 Line in 1895. He

served with the Royal Garrison Artillery and was awarded the Victory Medal and

the British War Medal. He died in Northallerton on 17 April 1971.

89289 Gunner

John Joseph Farndale was born in Great Ayton on 22

January 1882. He enlisted into the Royal Garrison Artillery on 4 December 1915.

He lived at Low Green House,

Great Ayton and his trade was a builder. His Descriptive Report showed he was 5

feet and 8.75 inches tall and Church of England by religion. His next of kin

was his wife, Mary Ann Farndale or Low Green House, Great Ayton who he had

married at Great Ayton on 2 July 1914. His service record showed that he

attested on 4 December 1915 and was transferred to the Army reserve on 17

December 1915.

John was

mobilised on 30 May 1916 and posted to the Heavy Artillery Depot at Woolwich on

30 June 1916. His character was very good. On 1 October 1917 he was appointed

wheeler and posted to RSG Sheerness Garrison. He was at Ripon in April 1918.

There was a medical board held in April 1918 and he appears to have been

transferred to the Reserve. He was certified a skilled wheeler.

He was

discharged on 14 December 1918. He was awarded the Campaign Medal and was on

the Silver War Badge Roll.

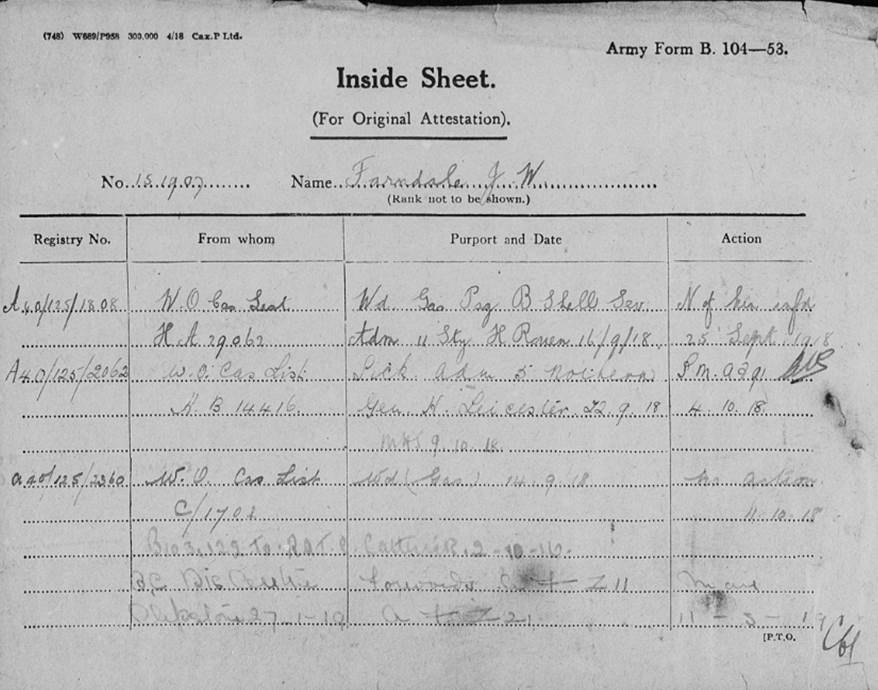

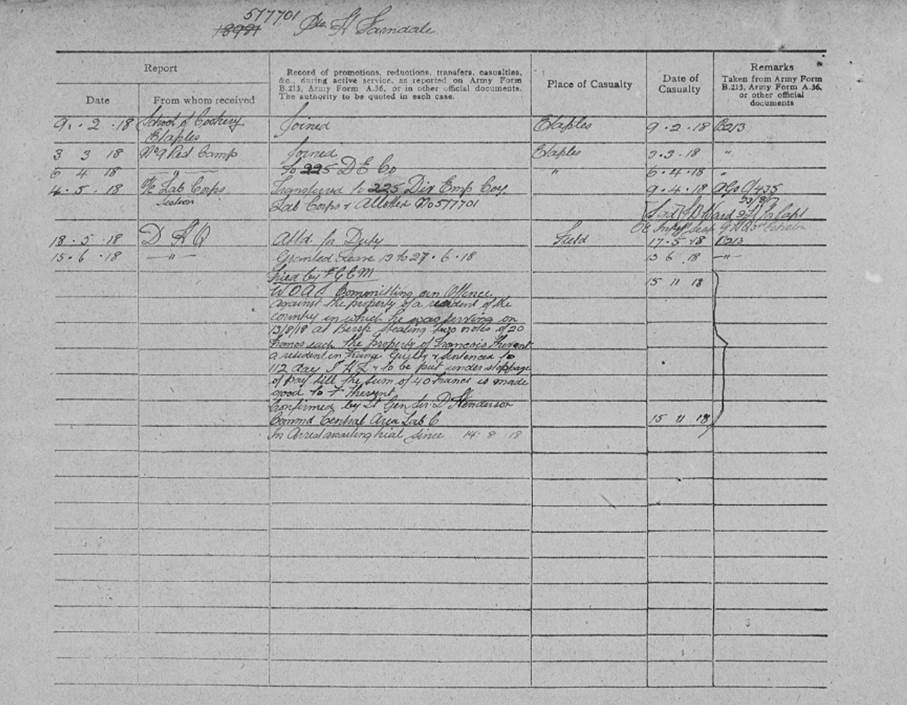

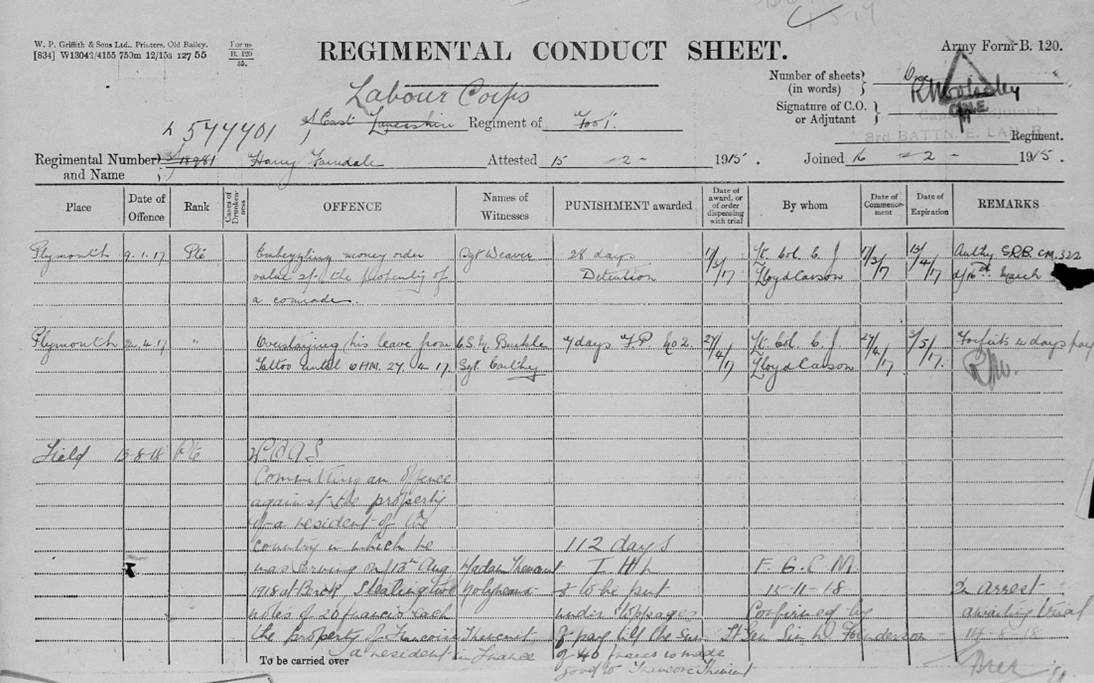

L/28839

Driver John W Farndale was born in Huttons

Ambo in 1894. He served with the Royal Field Artillery (“RFA”). When

he attested into the army on 7 June 1915, he was 21, single, and a farm

servant. He was originally enlisted into 176th (Leicester) Brigade Royal

Field Artillery. He was 5 feet and 6.5 inches tall. He was posted to 238

Brigade, RFA from May 1916 he was in France with the Expeditionary Force. His

Active Service record shows he travelled to Le Havre from Southampton on 8 and

9 January 1916 and was in the Field with R Battery (later D Battery 235th

Brigade RFA). On 4 June 1916 his brother, it is not clear from the signature

which one, wrote a letter to the Secretary of State asking for any news of John

who the family had not heard from for some time. His address was given as 28839

JW Farndale, R Battery, A Sub, 8th London Brigade RFA, 47th (2nd London)

Division, BEF, France.

The 8th

London (Howitzer) Brigade, Royal Field Artillery was a new unit formed when

Britain's Territorial Force was created in 1908. Together with its wartime

duplicate the brigade served during the First World War on the Western Front,

at Salonika and in Palestine where it was the first British unit to enter

Jerusalem. At the end of October 1914 training was stepped up, despite bad

weather and equipment shortages. Brigade and divisional training began in

February 1915 and it received its orders for the move to France on 2 March

1915. By 22 March 1915 all the batteries had reached the divisional

concentration area around Béthune, but

this was before John’s time.

On 19

January 1916 the batteries of 1/VIII London Brigade were re-equipped with

4.5-inch howitzers, for which they had been training since August. On 4

February it was joined by B (H) Bty and a subsection

of the Brigade Ammunition Column from CLXXVI (Leicestershire) Howitzer Brigade,

a newly arrived Kitchener's Army unit, followed by R (H) Bty of CLXXVI Bde on 4 April

1916, so this was the unit which John had joined.

In the

spring of 1916, 47th Division took over the lines facing Vimy Ridge. Active

mine warfare was being conducted by both sides underground at this time. In May

1916, the Germans secretly assembled 80 batteries in the sector and on 21 May

1916 carried out a heavy bombardment in the morning. The bombardment resumed at

15.00 hours and an assault was launched at 15.45 hours, while the guns lifted

onto the British guns and fired a Box barrage into Zouave Valley to seal the

attacked sector off from support. 47th Divisional Artillery reported 150 heavy

shells an hour landing on its poorly covered battery positions and guns being

put out of action, while its own guns tried to respond to desperate calls from

the infantry under attack, though most communications were cut by the box

barrage. During the night the gun pits were shelled with gas, but on 22 May the

artillery duel began to swing towards the British, with fresh batteries brought

in, despite their shortage of ammunition. A system of one round strikes

was introduced. Whenever a German battery was identified every gun in range

fired one round at it, which effectively suppressed them. British

counter-attacks were attempted, but when the fighting died down the Germans had

succeeded in capturing the British front line. Throughout their stay in the

Vimy sector the batteries suffered heavily from German Counter Battery fire.

On 1 August

1916 47th Division began to move south to join in the Somme Offensive. While

the infantry underwent training with the newly introduced tanks, the divisional

artillery went into the line on 14 August in support of 15th (Scottish)

Division. The batteries were positioned in Bottom Wood and near Mametz Wood,

and became familiar with the ground over which 47th Division was later to

attack. Casualties among Forward Observation Officers and signallers was heavy

in this kind of fighting. Between 9 and 11 September 1916, 47th Division took

over the front in the High Wood sector, and on 15 September the Battle of Flers-Courcelette was launched, with tank support for the

first time. The barrage fired by the divisional artillery left lanes through

which the tanks could advance. However, the tanks proved useless in the tangled

tree stumps of High Wood, and the artillery could not bombard the German front

line because No man's land was so narrow. Casualties among the attacking

infantry were extremely heavy, but they succeeded in capturing High Wood and

the gun batteries began to move up in support, crossing deeply-cratered ground.

Casualties among the exposed guns and gunners took their toll, but a German

counter-attack was broken up by gunfire. Next day the division fought to

consolidate its positions round the captured Cough Drop strongpoint.

When the infantry were relieved on 19 September 1916, the artillery remained in

the line under 1st Division.

4.5 inch

howitzer dug in on the Somme, September 1916

He was

demobilised in March 1920. He had a clean conduct sheet. He was awarded the

Victory Medal and the British War Medal.

151907 Gunner John W Farndale was born in Leeds on 18 May 1886. He

was attested on 21 February 1916 when he was transferred to the Army Reserve.

His Descriptive Report confirms his next of kin as his wife, Dorothy Doris

Chamberlain of 22 Laurel Road, Leicester who he had married at Leicester on 21

April 1916. They had a daughter at the time, Pauline Margaret

Farndale who was born at Leicester on 22 February 1917. He was 5 feet and

7.5 inches tall. He had been a commercial traveller in Leeds. He was mobilised

on 2 February 1917, to join 434th (Siege) Battery, Royal Garrison Artillery. He

was embarked on 5 April 1917, although another record suggests he was at Hull

and Glen Parva, Leicester in April and May 1917. He had first joined for duty

at Ripon on 6 April 1917.

434 Siege

Battery Royal Garrison Artillery was formed on 21 April 1917 at the Humber. The

Battery deployed to the Western Front on 5 September 1917 and took over 6 inch

guns from 198 Siege Battery. In late 1917, most of the Heavy and Siege

Batteries of the Royal Garrison Artillery were transferred to come under orders

of a Heavy Artillery Group with which they then remained. Before this, they had

frequently been transferred from Group to Group. 434th Siege Battery

became part of 25th Heavy Artillery Group and became Army Troops

from April 1918.

Second

Lieutenant Nathaniel Croger of 434th Siege

Battery was killed on 25 September 1918, in what may have been the same action

that Hohn Farndale was gassed.

6’’ Gun

of the 484th Siege Battery, Royal Garrison Artillery

He was evacuated after a gas attack in September 1918. He was

on the casualty list as a result of being wounded by a gas ‘B’ shell sev, which may have meant severe. This

suggests he was admitted to Rouen on 16 September and later to the General

Hospital at Leicester on 22 September 1918.

In May 1915,

a denouncement of the horrors of asphyxiating gases, was given in the

Leeds newspapers. The use of poisonous gases by the Germans in their latest

offensive in the western area of the war will be no surprise to those who know

well the German character, or to those who have studied the record of their

disregard for all the humane rules and conventions of war during the past nine

months. That a nation, whose sovereign and rulers have ignored solemn treaty

obligations when it has suited their convenience to do so, and have been

responsible for the murder and pillage of the civilian populations of Belgium

and Poland should ignore Article 23 of The Hague convention, which forbids the

use of poisonous or asphyxiating gas in civilised warfare, was only to be

expected to, and the only surprising fact is that this new barbarism of the

military oligarchy in Germany was not brought into use earlier in the war.

Since the German defence is that the French and ourselves began this new style

of warfare by using shells emitting poisonous gases, it may well be as well to

examine discharge, and to show how far it is from the truth.

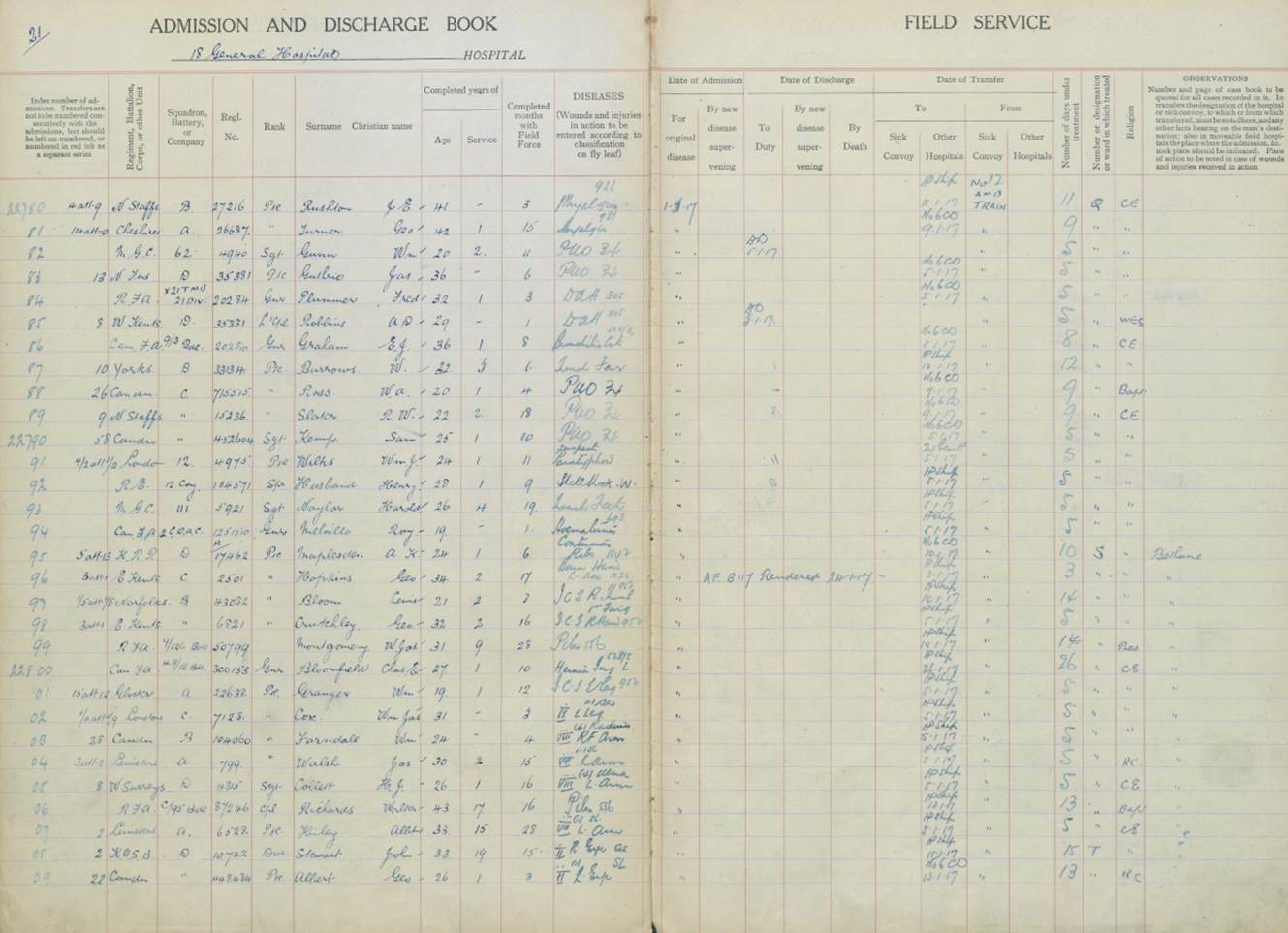

151907

Gunner Farndale, L Battery, was listed in the Hospital Admission and Discharge

registers at Catterick Military Hospital. Another record suggests he was

admitted on 9 September 1918. The record lists previous inoculations. Another