Act 3

Roman Kirkdale and Beadlam

71 CE to 580 CE

The lands which would become the

lands of Kirkdale and Chirchebi in Roman and Pagan times

The lands

around Kirkdale were stable and settled for much of their early history,

nestled for protection at the edge of the North Yorkshire high lands. The

association of the estate lands where our family originated, with Roman villas

of Beadlam and Hovingham and the regional centre of Isurium Brigantum,

as well as with the eventual provincial capital of Eboracum, means that we can

continue our story to Roman imperial Britain.

|

This

is a new experiment. Using Google’s Notebook LM, listen to an AI powered

podcast summarising this page. This should only be treated as an

introduction, and the AI generation sometimes gets the nuance a bit wrong.

However it does provide an introduction to the themes of this page, which are

dealt with in more depth below. |

It was those small families who

cleared Farndale from the early thirteenth century who we met in Act 1, at the same time that names started

to be used in a way that would soon become hereditary, who allow us to begin to

recount stories of individuals and their experiences. Before that time it is

impossible to identify individuals other than the most noble or royal families.

Names of ordinary folk were just not being used, still less recorded, in a way

which would allow us to claim direct links.

However because we know that our

family emerged into recorded history in a distinct place, a wooded valley in

the dales flowing south from the North York Moors, we are able to continue to

explore the likely path of our ancestors further back in historical time. We

know that by the Norman Conquest, the wild forested lands of Farndale were part

of the great estate of Chirchebi and within that estate there were

settled lands nestled into the northeast corner of the Vale of York as the

agricultural plains met the lower dales. The settled lands of our family were

focused around the place that later came to be known as Kirkdale. So although the name Kirkdale will

not emerge until the seventh century CE, in the Farndale Story we can call

those lands “Kirkdaleland”.

Before the Romans arrived and

expanded their interests to include Kirkdaleland by perhaps around 100 CE, we

should restrict our ambition to pursue the family ancestors to a general

perception that they probably emerged from the primeval swamp of the stone,

bronze and iron ages, which were the subject of Act 2 of our story. However after the

Romans incorporated Kirkdaleland into its Empire, those ancestral lands became

a place of settlement, agriculture and stability. There is every reason to

suppose that our family story shares the story of Kirkdaleland from the time

those lands were tamed by the Romans.

Our family story will soon follow the

trail from the aftermath of Empire Britain to the birth of the English nation,

the spread of Christianity, and the remarkable ambit of York which became a powerhouse of

intellectual achievement in the Anglo Saxon age and disseminated knowledge and

teaching techniques via the court of the Holy Roman Emperor, Charlemagne across

Europe. When we pick up the story again after 1200, we will meander our way

through Plantagenet England, to the industrial age, which we will experience

from the heart of the lands of mills and mines. The family will spread to

become farmers across the new worlds of the British empire and will fight in

the terrible wars of the twentieth century.

Before we embark on that later

journey we start our path in a time of empire, when Kirkdaleland was a northern

region of a unified territory that stretched to Assyria and Mesopotamia in the

east and to North Africa to the south. This might give us a sense of

perspective.

Our family’s journey is only a

perspective on one family’s travels through its own history, which happens to

closely follow the fortunes of England and later Britain. There were countless

families in other places across the globe following different histories, with

equally exciting stories of other national paths. One route into the global

perspective of world history is the podcast series by William Dalrymple and

Anita Anand, Empire, which although touching on the history of the British Empire is far

more an exploration about multiple civilisations and world history. For

instance William Dalrymple has explored the Ashokan Empire of India, which was also within the Roman

ambit, a theme which he explores in his 2024 book, the Golden Road.

As we follow our own path of course

we find a route through our own national experience, but when we use our twenty

first century eyes, we have the privilege of understanding that story within a

global perspective. As the Roman world touched the North York Moors, it was

also within the experience of remarkable civilisations such as India, which

would spread its numbers and conception of zero, as well as its gold, back

westwards.

So now, we can continue the story of

this particular family, by finding ourselves in the midst of a western empire,

whose stretch had reached the agricultural lands of Kirkdaleland.

Scene 1 – Arrival

Empire

In Virgil’s Aeneid,

Jupiter announced that I have set upon the Romans bounds neither of time nor

space. With memories of a failed invasion of Britain by Julius Ceasar in 55

BCE, the Roman Empire by the early first century CE, had adopted an

aggressively imperialistic stance. The Romans came to Britian, to stay, from 43

CE when the Emperor Claudius (41 to 54 CE) rapidly annexed the south and east

of the country. The Romans found diversity in those who they subjugated, with

differing views regarding the benefits of Roman occupation. Their policy was to

exploit internal conflicts between different groups and between squabbling

sons, such as those of Cunobelinus, who Shakespeare called Cymbeline.

Initially

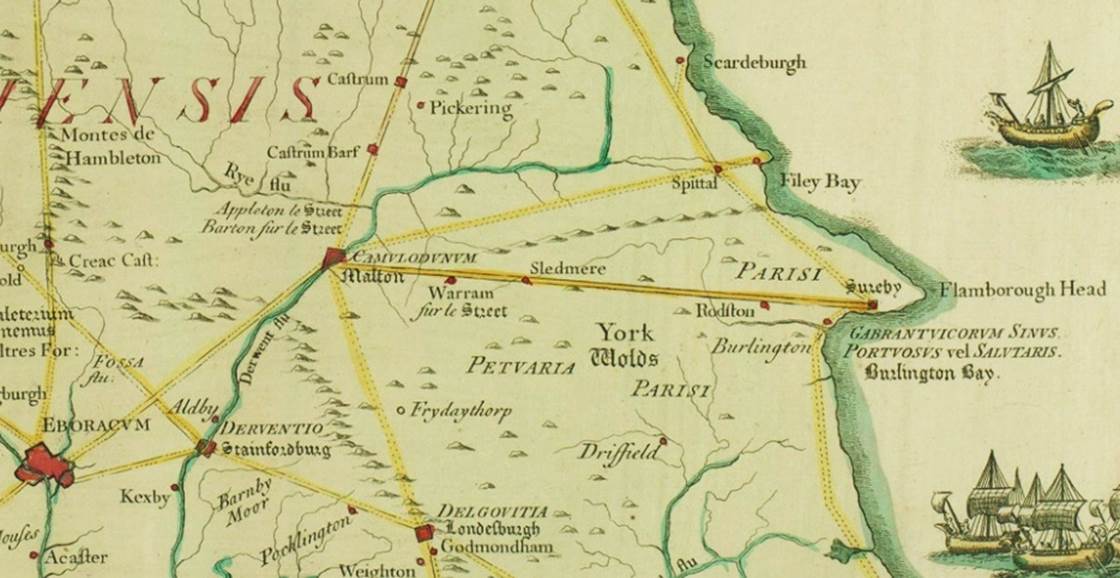

the Romans didn’t venture north of the Humber and Don, but traded with the Parisii, and followed a complicated political path

with the Brigantes.

Claudius’

successor was Nero (54 to 68 CE) who was less enthusiastic about the costs of

maintaining an army in Britain, so expansion slowed.

Nero was

succeeded by Vespasian (69 to 79 CE) at the end of the

Year of the Four Emperors, Vespasian was the commander of the Syrian Army,

and had served in the army in Britain under Claudius. He appointed Gneaus Julius Agricola (40 to 93 CE) as his general.

Agricola extended the Roman occupation across large swathes of northern

Britain, well into Scotland. Agricola’s biography, The

Agricola, was written by his son in law Tactitus.

Roman

experience around the Mediterranean was of city states and centralised groups,

who were susceptible to defeat on the death or subjugation of their leaders.

However in northern Britain they encountered a region where large stable

political units were less usual. The Roamn referred to the people who lived in

the Vale of York, the moors and the dales, and across the Pennines, as the Brigantes.

They appear to have treated them as a centralised group, but this was probably

a mistake. The Brigantes may have been a loose grouping of hill

people, which the Romans might have mistaken as a tribal name.

Claudius had

formed an alliance with Queen Cartimandua, who

Tacitus referred to as Queen of the Brigantes. She and her husband Venutius were, according to Tacitus, loyal to Rome. They

seem to have had their base at an old iron age fortification at Stanwick near

modern Scotch Corner. In 51 CE, Caratacus,

leader of the Catuvellaunians, being roughly the

place of modern Bedfordshire, had sought sanctuary with Cartimandua, but she

had handed him over to the Romans.

When

Cartimandua had a relationship with her armour Bearer, Vellocatus,

her husband Venutius began a civil war against her in

57 CE, but Cartimandua was protected by the Roman Ninth Legion. In 69 CE,

during a period of instability under Emperor Nero, Venutius

attacked again and Cartimandua fled leaving Venutius

in control of the region and in conflict with Rome.

In 71 CE, Nero’s successor Vespasian sent an army under

Quintus Petillius Ceralius to march north and occupy Brigantes

and Parisii territory. The Ninth Legion

erected a large camp near where Malton, northeast of York. stands today. They

also built a fort at Roecliffe, near to modern Aldborough, which was occupied between about 71

to 85 CE. Roecliffe was one of a string of forts

along the line of the modern A1, which provided the main Roman transport

corridor.

A large

military camp was constructed by the Romans as Eboracum, modern day York, in 71 CE.

Urban

settlements grew around the Roman fortifications at Eboracum and Malton.

Eboracum in time became the Roman provincial capital. The Emperors

Hadrian, Septimius Severus, and Constantius I all held court in Eboracum

during their various campaigns. Constantine the Great was proclaimed emperor

there. To the south Roman urban settlements grew around fortifications at Calcaria, Tadcaster, and Danum, Doncaster.

Agricola was

made consul and governor of Britannia in 77 CE.

Domitian (81

to 96 CE), who succeeded Titus (79 to 81 CE), completed Agricola’s campaigns,

but was distracted by imperial interests elsewhere, so withdrew from the areas

furthest to the north, which would lead in time to the reconciliation of Roman

occupation to the wall which would later be fortified as Hadrian’s Wall.

Roman

domination was absolute. Tacitus’ imagined words of a defeated Caledonian

commander, perhaps best reflect the mastery of Rome over the subjugated.

We, at

the furthest limits both of land and liberty, have been defended to this day by

the remoteness of our situation and of our fame. The extremity of Britain is

now disclosed; and whatever is unknown becomes an object of magnitude. But

there is no nation beyond us; nothing but waves and rocks, and the still more

hostile Romans, whose arrogance we cannot escape by obsequiousness and

submission. These plunderers of the world, after exhausting the land by their

devastations, are rifling the ocean: stimulated by avarice, if their enemy be

rich; by ambition, if poor; unsatiated by the East and by the West: the only

people who behold wealth and indigence with equal avidity. To ravage, to

slaughter, to usurp under false titles, they call empire; and where they make a

desert, they call it peace.

(Tacitus, Agricola,

30)

Scene 2 – Ancestral Lands

The

family ancestral lands of Kirkdaleland

After the

shock and awe of the first century CE, the years passed, and the lands of north

east Britain settled into easy going provincial domains, drawing on the

benefits of international communications. The nightmare years had passed. Urban

settlement emerged where native folk could learn some Latin, and take some part

in local government.

The lands of

Kirkdaleland are only about twenty five kilometres north of the major Roman

regional capital, Eboracum (York). Eboracum would have become

increasingly accessible from Kirkdaleland during the Roman period, with the

construction of new roads.

Thurkilesti was an ancient road from Cleveland across the North York

Moors which passed close to the west side of Kirkdale and on to Welburn, just

south of the Kirkdale ford and to Hovingham where it later joined the Roman

roads. It was later referred to in Roger de Mowbray’s grants of land to Rievaulx. Kirkdaleland was a

peripheral region, but with connections to the wider political world.

During the

Roman period, Kirkdaleland was in the Roman hinterland. By the late Roman

period, Kirkdaleland was probably part of a stable, well

regulated area with dispersed settlement, probably dependent on major

villa based estates such as at Beadlam and Hovingham.

The

significance of Ryedale was reinforced by an extensive Roman road network.

Wade’s Causeway ran from Malton across Wheeldale Moor

towards Whitby. A Roman road ran from Malton

to the Vale of York via the Coxwold and

Gilling gap where it joined Hambleton Street which stretched from Bernicia to

Lincoln.

The Roman

villa at Beadlam,

only two kilometres west of Kirkdale, was discovered in the 1960s. Beadlam lay within the region formerly controlled by the

kingdom of the Brigantes. After the Roman conquest, the region was

administered from the newly built Roman town of Isurium Brigantum, modern Aldborough, near Boroughbridge. Isurium was a strategic regional capital on the main

transport corridor of Dere Street and along that transport corridor to the

south was Calcaria, Tadcaster; Lagentium, Castleford; and Danum, Doncaster.

|

Isurium Brigantum (Aldborough) The

Roman Regional Capital of the lands around Kirkdale |

|

A

Roman Villa on palatial scale just south of Kirkdale |

|

A

Roman Villa only 2km from Kirkdale in the heart of our ancestral lands |

So by the

later Roman period, Kirkdaleland was part of a stable and well

regulated region, in close proximity to the regional capital of Eboracum.

Only two kilometres to the west of Kirkdale the Roman villa of Beadlam consisted

of about thirty rooms, probably constructed in about 300 CE and occupied until

about 400 CE. The fourth century CE was a time when elite Romano Britains were investing in private villas. An enclosure

ditch and walled compounds for livestock pre-dated the villa, which suggests

the site was in use earlier.

|

The

Roman Capital of northern England where Constantine was proclaimed Emperor |

It’s

possible that any Roman presence at Kirkdale itself might have been related to

a place for the burial of the dead from Beadlam.

Hovingham was a Roman villa, perhaps on a

palatial scale, about ten kilometres southwest from Kirkdale. Hovingham might

have had very extensive holdings, which could have embraced a wider estate

including Beadlam and Kirkdaleland.

Villas at

Appleton le Street, Blandsby Park and Langton

indicate that Ryedale was a major agricultural producer in the Roman period.

The landscape of the Vale of Pickering was also likely to have been well

settled. Agricultural produce would have been required at significant scale to

support the northern Roman army.

In the Roman

period, the area around Kirkdale probably included a small number of dominant

settlements in this area of rural hinterland. The population would have been

within the military and administrative orbits of the Roman interests.

A Roman

Port Key

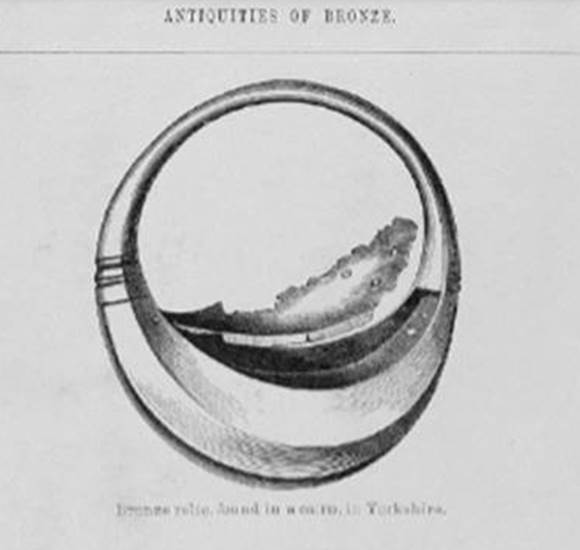

One day in

the second or third century CE, a

Roman soldier dropped his arm purse, close to a prehistoric cairn, above

and overlooking Farndale.

It was later found in 1849 and is currently to be seen displayed in the British

Museum. When the Roman looked over Farndale

it remained a wild forested place.

Roman copper

alloy arm-purses were worn by soldiers. British examples include finds from

Corbridge, South Shields, a site near Housesteads on

Hadrian’s Wall, Colchester, and this one found at Farndale. As it was found above Farndale, it doesn’t evidence

Roman activity within the dale, but it does suggest patrolling across high

moorland tracks, overlooking the dale. Go and see this purse in the British

Museum and you’ll be in direct contact with the land of our ancestors, two

millennia ago.

|

A Roman arm purse which can be seen in the British

Museum in London today, found in about the second century CE by a cairn

overlooking Farndale, which will transport you back 2,000 years |

Scene 3 – The End of Empire

Breakup

Constantine

(272 to 337 CE), who had been declared emperor in York in 306 CE, elevated the status of Christianity throughout

the Roman world and built a new imperial residence in the East centred on New

Rome which came to be called Constantinople and later Byzantium.

The problems

which started to beset the Roman empire in the late third century CE, were not

British problems. By this time the folk of Britain were lapping up the benefits

of the Roman empire. New threats came from the east, reflected in a deflection

of Roman defensive effort from Hadrian’s wall to a new chain of Saxon shore

forts, constructed along the eastern and southern shorelines, during the

time of the military commander, Marcus Aurelius Mausaeus

Carausius. The eastern threat deflected Roman legions away from Britain at a

time when Anglo Saxons threatened Britain and penetrated the lines of shore

forts.

Military

weakness led to economic crisis. An age of cattle and sheep rustling was born.

In 410 CE Rome was sacked by the Visigoths from eastern Europe and Roman

control of Britain ceased by about this time. It was about this time that the

Emperor Honorius wrote to the elite of Britain to tell them they were on their

own. The year 410 CE was a momentous year for the fate of Britain. Civilisation

collapsed very rapidly. The trauma can only be imagined. The immediate threat

came from the northern regions of Germany, Denmark, Jutland and Lower Saxony.

The

Romano-British kingdom rapidly broke up into smaller kingdoms. In time, York

became the capital of a British kingdom of Ebrauc.

Go Straight to Act 4 – Anglo

Saxon Kirkdale

or

Before you

do that, you can explore more detail about the Roman history of the region:

· Beadlam

· Isurium Brigantum (Aldborough)

· Eboracum (York)

If your

interest is in Kirkdale then I suggest you visit the following pages of the

website.

· The community in Anglo Saxon

Times

· The church in Anglo Saxon Times

· The Kirkdale Anglo Saxon

artefacts

· The community in Anglo Saxon

Times

· The church in Anglo Saxon

Scandinavian Times

You will

find a chronology, together with source material at the Kirkdale Page.