Genealogy

A discipline which starts as a

science, but finds richness as an art

Some notes on the sources and methods

used to compile and bring alive the lineage of a family

|

This

is a new experiment. Using Googleís Notebook LM, listen to an AI powered

podcast summarising this page. This should only be treated as an

introduction, and the AI generation sometimes gets the nuance a bit wrong.

However it does provide an introduction to the themes of this page, which are

dealt with in more depth below. Listen to the podcast for an overview, but it

doesnít replace the text below, which provides the accurate historical

record. |

|

Types of

Families

Where a

family descends from noble and aristocratic lines, the records are extensive

and pave a course well back in time. Sometimes families can find a gateway

ancestor, a link to a relative of pedigree, whose ancestry has already been

studied and recorded in detail and which might provide a direct route to

medieval noblemen and perhaps royalty. The Farndale family are not such a

family. That would be no fun.

The

Farndales, like most British families, were not aristocratic folk. Such

families bind and explain the social fabric of society through the ages. They

are the bedrock of society, and it is their graft and experience which provided

the engine room for a nationís story. So if we can take such a family, and

explore it through time, it is likely to provide a unique insight into British

social history.

Surnames are generally of four types.

Occupational

surnames derive from historical jobs, like Baker which was my grandmotherís

name, until the names become fixed over time.

Patronymic

names allow a fellow with a Christian name to link himself to his father,

providing more continuity to who he is, like Orm Gamalson, who we meet in the Anglo-Saxon-Scandinavian

history of Farndale Story, the Saxon/Viking feudal lord of Kirkbymoorside.

Descriptive

names originated in nicknames until they became fixed as surnames, like

Whitelock from the complexion of hair, or Pybus from pikebush

describing a prickly character, both being examples of families who have

married Farndales.

The fourth

type of surname is a locative name. Those fortunate to have a locative name

have an advantage in genealogy, because as the records dim over time, there is

still a route to find more about the people who lived in the place, and about

the place itself. Where that placed is relatively small, and easy to place in

time, particularly a rural spot which is nevertheless identified and described

in history, then it becomes possible to build up the fullest history back to

the earliest of times.

The three

eras of genealogy

A

genealogist perceives history in three distinct eras.

1560 to

Date

For

genealogists of English history, their exploration becomes easier when

exploring their ancestors from 1538, when parish records started to be made,

and even easier as births deaths and marriages were recorded more formally and

centrally, and census records started from 1801.

In reality

parish records often did not permeate into local parishes until a little later

in the sixteenth century. So the period from about 1560 to date is a period

about which, if pursued with enough passion and belief, a comprehensive family

record can be compiled. Sometimes a record is missing and a dilemma just canít

be resolved, but generally the whole family and its inter-relationships, can be

compiled from about 1560, if pursued with sufficient determination.

1200 to

1560

Before 1560

genealogists donít have clear records of family relationships. That means, save

some aristocratic and royal family lines where lineages have been recorded, it

is not possible to construct a definitive family tree. However, that does not

mean that the family story ends in about 1560. There are extensive medieval

records available from the Norman Conquest.

Names which passed down through generations

did not start to be used by most ordinary families until the thirteenth

century. So medieval records do not assist until then because they simply donít

record individual people who might have been members of the family being

researched. However if you start a search in the medieval records, you might

just start to find individual records as building blocks from which to compile

a family story, as they start to emerge in the thirteenth century. The task of

compiling such a story from the medieval period might just be too difficult for

the Petersons, the Smiths or the Taylors. However if a family has the privilege

of a locative name of some uniqueness, the magic of recovery of a medieval

history becomes a possibility. For every time Farndale appears in the medieval

records, it will inevitably be a reference to the place where our ancestors

lived, or to an individual person. Sometimes those records even provide

evidence of relationships, where for instance they refer to Robert,

son of Simon the

Miller of Farndale, being caught poaching. With enough records, it becomes

possible to build a picture of some accuracy of the relationships and lives of

a family back to the thirteenth century.

The art of medieval genealogy is explored

in another webpage.

Before

1200

Before the

time individuals started to use heritable names, it follows that individual

stories canít be followed. However that may not be the end of a genealogical

journey. If you can link back the genealogical story to a particular place, the

story of that place is the likely to hold a story of deeper ancestry.

If you can

trace your family history to a particular place, particularly where the family

adopted a locative name which is rooted in that place, there is value in

continuing your journey to explore the community who lived there, since that is

likely to be the story of the familyís deeper history. Having traced the

Farndales to the valley from which they took their name, it turned out that the

valley was part of a larger estate which was relatively stable from Roman,

through Anglo Saxon and Scandinavian, to Norman times. So whilst I was not able

to identify individual ancestors before the thirteenth century, I was able to

explore the history of the valley and the wider estate of which my more distant

ancestors were likely to have been associated. Of course that exploration

should take account of historic migrations and fluidity of populations, but

where the history stumbles across a place of mobility, the historical and

archaeological record is likely to provide a useful tool in pushing the

boundaries of a familyís history further back in time.

For anyone

beginning a genealogical journey, I suggest you start by understanding the

distinct disciplines of research for the periods (1) 1560 to date; (2) 1200 to

1560; and (3) before 1200. The first begins an exercise in pure genealogy, but

which can be enhanced by the context of a wider historical understanding. The

second is an exercise in medieval

genealogy, which may take a very different approach, sometimes more like

detective work, but which has the capacity to provide passage to more distant

worlds. The third is a historical and archaeological exercise, to explore the

place of ancestry, and take a journey back into deep time.

The

approach to historical evidence

My

professional discipline is in law. I was involved in the resolution of complex

construction and engineering disputes in court and arbitration. The heart of my

discilpine was an understanding of the legal rules of

evidence, which determined how facts would be interpreted, and from which legal

conclusions, and judgements, could be made. I have therefore tended to approach

genealogy from the stand point of my legal experience.

There are

two distinct standards by which legal evidence is assessed. The first standard

is a tougher one, by which criminal cases are assessed, since they can lead to

a loss of freedom or other privilege. The standard requires facts to be

determined beyond reasonable doubt. There must be near certainty that a

fact is a true fact, if it is to form part of the jigsaw to determining an

outcome. In a legal context this often involves corroboration, so that a fact

is proved from more than one source. I think this standard might reasonably be

used by a genealogist as the gold standard to which he or she aspires. Finding

two sources of a fact might well be helpful, but sometimes a single record,

such as a birth certificate, might be enough to put beyond doubt the basic

facts of an individualís history, and it might provide certainty on such

relationships as a personís parents. The approach I take is, particularly for

the period 1560 to date, that a genealogist should strive to prove each primary

fact to this higher standard of proof in the first instance.

The second

standard of proof is used in civil cases where rights and obligations between

individuals or organisations have to be weighed up and assessed. It is a

balancing act, and the standard of proof reflects that. Civil cases are proved

on a balance of probabilities, that is on the basis that a fact is

accepted if it is more likely than not. Generally this is taken to be a

51% likelihood that a fact is correct. When piecing together a family story for

the period before 1560, it is likely that the higher standard of proof will not

be possible to reach. Yet it is possible to assemble a rich body of evidence

which can still be pieced together to establish the most likely factual

narrative. Sometimes for the period after 1560, try as you might, it is possible

that a vital factual clue has been lost from the records. There again, it is

not necessary to accept defeat and give in, but rather to accept the reality,

and consider the body of evidence that is most likely, and build the family

story based on the most probable interpretation of the facts. Weigh up each

fact, and where certainty is not possible, follow the most likely

interpretation. Of course if facts subsequently come to light that disprove an

assumption, such factual interpretation will need to be reassessed. Yet by

following this approach, the narrative will be the most likely one, and by

building on the most likely factual interpretation, a bigger picture will

emerge, which can itself make more sense of the family story.

Having built

the factual narrative, adopting the highest standard of assessing evidence that

is practical to achieve, it is possible to start to narrate a story, which

binds the whole together, into a journey into the past. There is I think even a

place for borrowing literary accounts of the past to enhance that story. The

depth of Shakespeareís prose can sometimes enhance an encounter with medieval

history. The starkness of Dickensí descriptions of Victorian social change can

bring aspects of a family story to life. The perception of Flora Thompson in

her descriptions of late Victorian rural life can make sense of experiences

which our own ancestors must have felt.

Historical

fiction is a discipline which is governed by its own rules. It starts from

historical facts which are known and established. If authentically approached,

the historical facts are not altered but historical novelists use their

imagination to fill the gaps between those facts with what is perceived to be a

likely scenario. Of course the aim is to write an interesting story, and

novelists may well be attracted to the more interesting scenario. Yet such

novelists fill an important void, in capturing likely, if imagined, pictures of

what might well have been, where the historical facts will never reveal what

actually was.

Genealogy

must start as a science, cold and disciplined. We should start work in the

mindset of Dickensí Thomas Gradgrind. Now, what I want is, Facts. Teach

these boys and girls nothing but Facts. Facts alone are wanted in life. Plant

nothing else, and root out everything else. You can only form the minds of

reasoning animals upon Facts. Nothing else will ever be of any service to them.

This is the principle on which I bring up my own children, and this is the

principle on which I bring up these children. Stick to Facts, sir! We start

the exercise bound by the rules of a criminal prosecutor, to strive to prove

each fact, methodically, beyond reasonable doubt.

We then

continue, having relaxed the rules a little, to pull together the evidence

which is available, to find paths through the what can be ascertained to

provide the most likely interpretation. Having started the exercise like Mr

Gradgrind, this slightly less formal approach will help to build a broader

picture of a familyís history.

Finally,

though never seeking to alter the facts which have been already established by

the first two stages of the exercise, we leave the discipline of science, and

adopt the approach of the artist, to tell a story which will take us on a

journey through time. That might involve the application of imagination, of

which Gradgrind would disapprove.

The

Scaffolding

The

genealogical journey therefore begins by the construction the scaffolding. It

is a scientific pursuit. At first the tools are very limited, and itís best to

keep them so.

A

genealogical novice will first be encouraged to speak to immediate relatives,

and that must be the sagest advice. The starting point must be to build up a

simple family tree to link together a familyís relationship as deeply and

broadly as it is possible to do from family knowledge.

I was

fortunate because my father, Martin Farndale, had extensively researched the

familyís history before me, though in pre computer days when remarkably he had

to work painstakingly through written records in different parishes and other

sources. So when I took over responsibility for the work at about the turn of

the Millenium, the structure was already well in place.

It might be

tempting to leap to an interesting individual of the right name and see if a

link can be found. Occasionally there might be a place for such an exercise,

but certainly not early on. Gradgrind would disapprove of that approach. If you

start from the known fact of a more contemporary relative, it is far better to

work backwards in a more methodical way, taking each step backwards in time in

a more confident way, establishing the route as a scientist, from known fact to

new known fact. As a rule, it is always best, indeed it is essential really, to

work backwards, from what is known with certainty, into the unknown past. So

the work should start in the modern age, with trails followed backwards. When

trying to solve a problem, start with what is known for certain in more modern

times, and work back to try to use records to fill in what happened in earlier

times.

There are

occasions when a scattergun approach can help. With a name like Farndale, it is

certainly worth finding a medieval record set, and just searching the name to

find what comes up. That will help with some building blocks, then to be

slotted in. It is not though the place to start.

Having

exhausted family knowledge, there are then two key tools which can be used to

continue the scaffolding construction project. The first tool is records of

births, marriages and deaths, or ďBMDĒ as generally abbreviated. The

second tool, available in English genealogy from 1801 (though generally

becoming more useful from 1841), is census records. You might also find help in

more recent voter registration records, but I tend to find these records of

secondary use to BMD and census records.

Records of

BMD will be found from about 1560 in parish records, and more recently in the

form of formal certificates, which provide more information.

A record of

birth will generally provide a date of birth, which will help to define an

individual and locate them on a timeline. Hopefully they will also provide

information† of that individualís father

and hopefully (but not always) their mother and motherís maiden name. It should

also provide a place of birth. It might provide some more information† of interest, such as parentsí occupations.

Sometimes the record is of a baptism rather than a birth, and the date might be

the date of baptism. Generally, though not always, this will be close to the

date of birth. It is more likely that baptisms were soon after birth as you go

further back in time.

†

†

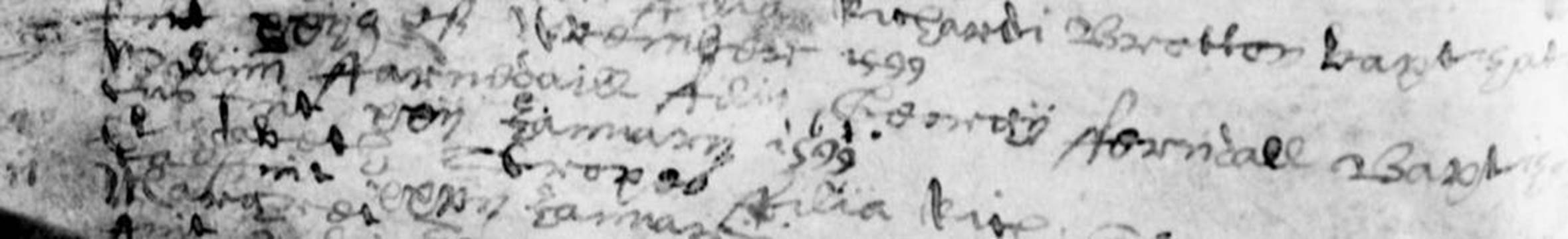

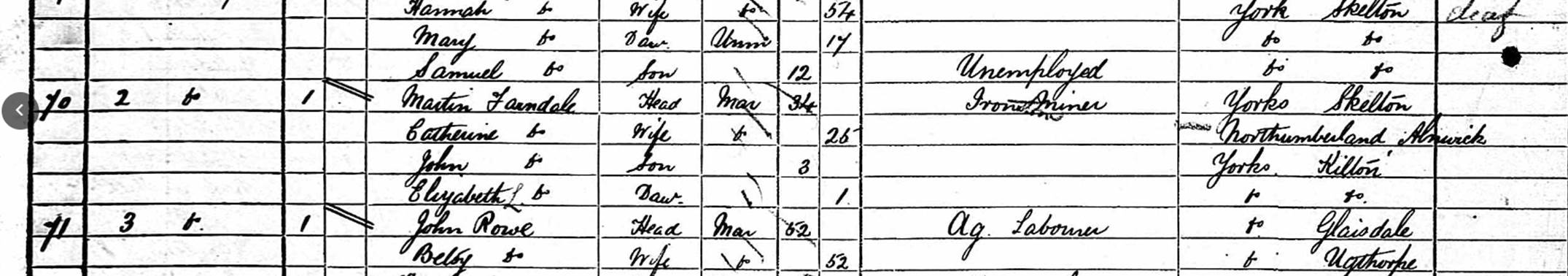

William Farndaleís

baptism recorded in Skelton Parish Records in 1599††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††

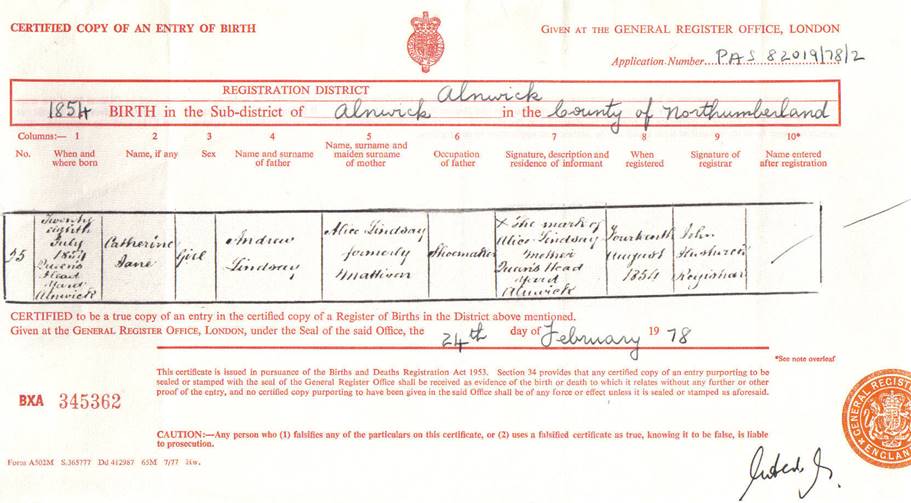

Catherine Lindsayís birth

certificate, 1854

A birth

record is the basic building block to create a tree of family relationships. By

linking an individual to their parents, a family tree can be created. If the

parentsí birth records can be found too, the family tree can be expanded. Birth

records alone have the potential to establish the whole scaffolding of a family

story.

There is

more help from parish records and from official certificates, because they also

provide evidence of marriages. Sometimes the information provided will be

limited to a date and record of the betrothed. However over time, marriage

records started to include records of fathers (rarely mothers until more

recently), so that they also provide corroborative evidence to an individualsí

line of descent. They might also provide a record of the occupation of those

getting married and of a fatherís occupation, so the marriage record of a son

or daughter might help to build up the occupational record of their father at

the date of the marriage. There are sometimes additional records of banns of

marriage available, which rarely provide more evidence than the marriage record

itself, but might serve as a substitute if the marriage record itself canít be

found.

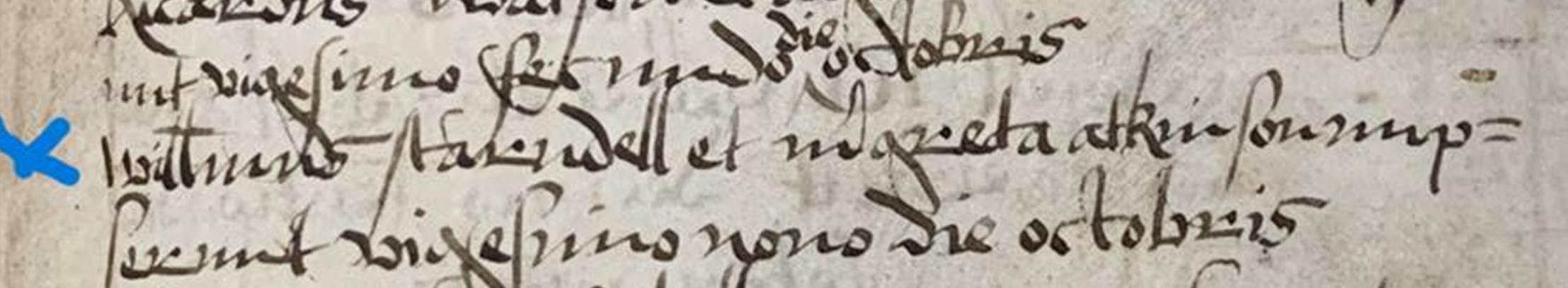

William

Farndaleís marriage to Margaret Atkinson, recorded in Campsall Parish

records in 1564

†††††††††††††††††

†††††††††††††††††

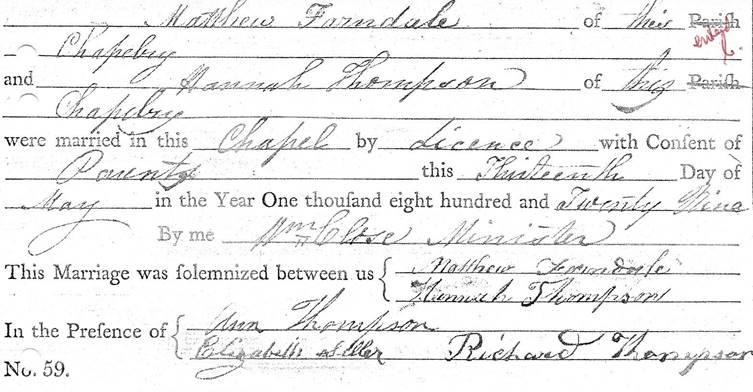

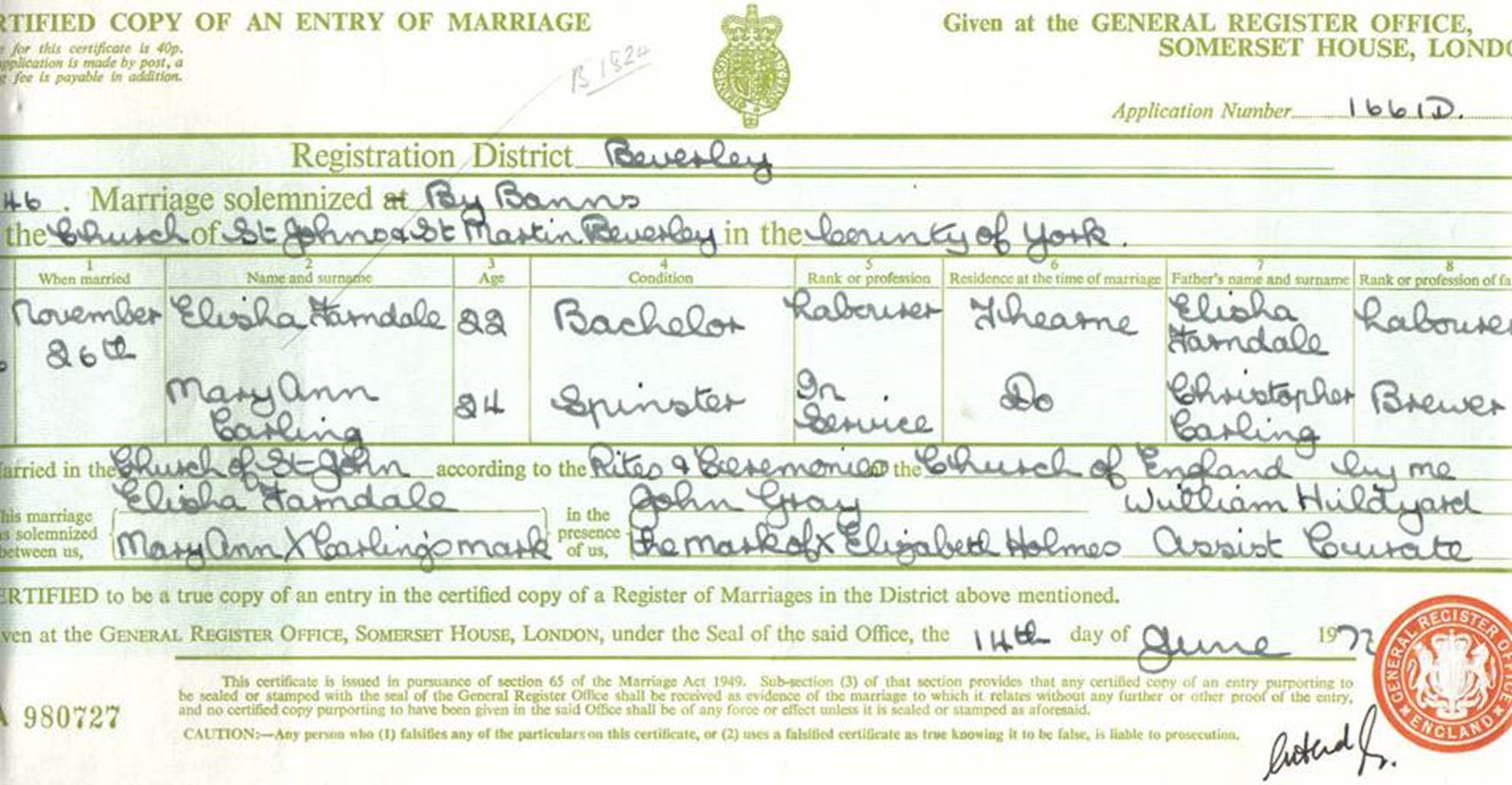

Record of

the marriage of Matthew

Farndale and Hannah Thompson in Brotton Parish records††††††† Marriage Certificate of Elisha Farndale

and Mary Ann Carling, 1846

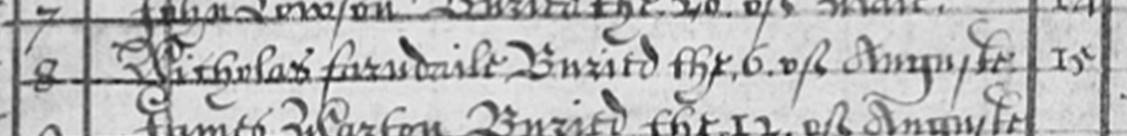

The third

event of an individual life which generally appears in records after about

1560, is their last, a record of their death. Where such a record appears

shortly after parish records started to be kept, as Nicholas

Farndaleís death in 1572, and Agnes

Farndaleís death in 1586, both in Kirkleatham, it might be all we know. Yet

from that information, we might conclude that it is likely that Nicholas and

Agnes were married, and that they might have been born in the early sixteenth

century, allowing us to predict a possible year of birth. Then, if we find that

another, called Jean Farndale,

was married in that same place, Kirlleatham on 16 October 1567, we might

conclude that Jean was probably their daughter. A snippet of information can

unlock the basis of a family tree.† †

†

†

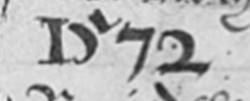

The death of Nicholas

Farndale, recorded in Kirkleatham in 1572

A death certicate enables us to draw out the timeline of a pesonís life,

from birth to death. It might corroborate the name of their spouse, where they

lived, sometimes their occupation or that from which they had by then retired,

and often the cause of their death.

Catherine Lindsayís death certificate,

1911

BMD thus

provide the building blocks of a family story, and alone might allow an

accurate family tree to be compiled to take the story back to about 1560, with

estimated birth dates extending the family story into the Tudor age of Henry

VIII.

The spelling

of surnames was not always consistent in more distant records. A little

detective work is sometimes requires to decide whether ffarndaile,

or farndell, is an individual from the same

family Farndale, or from some other tribe. Contemporary search tools sometimes

make it easier to recover likely variations of a spelling, and once you get

your eye in, when considering new facts against the wider factual narrative

which has already emerged, it is generally possible to solve these dilemmas.

Then there

is another tool, which can consolidate your work, available from 1801, but more

useful from 1841, and that is census records.

1881

Census Records showing Martin

Farndaleís family

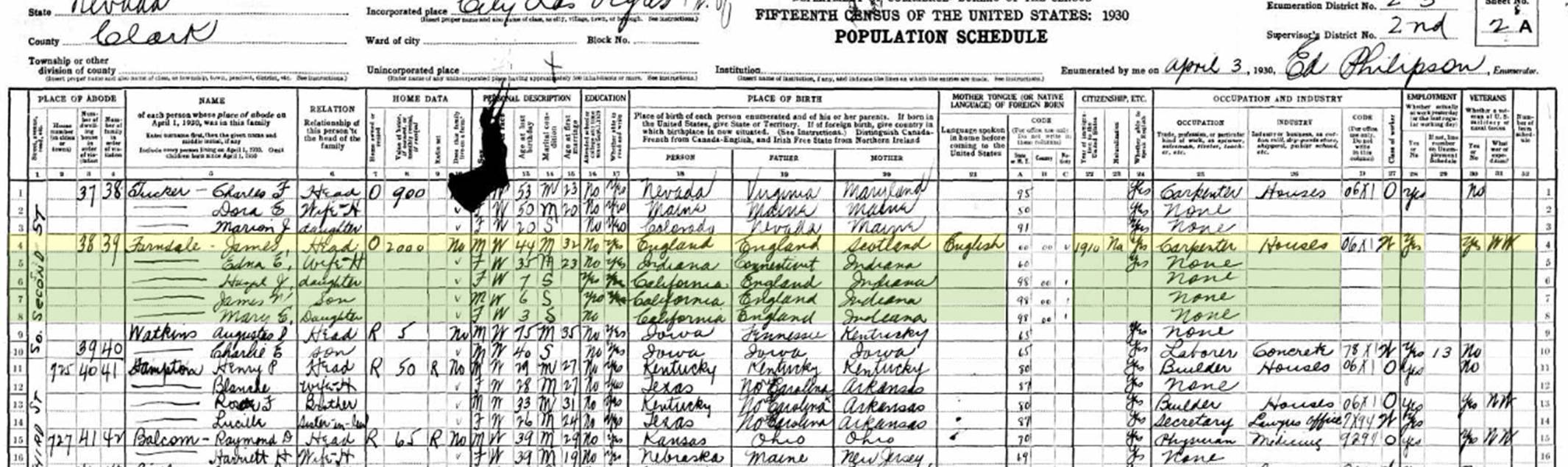

Census

record of Jim

Farndaleís family in Las Vegas, USA in 1930

Census

records pull together the story of a whole family at a particular place and

time. They corroborate relationships and generally show a whole family Ė mum

and dad and siblings, together in a place. They give an age and place of birth

from which the date of birth of each individual can be calculated. Occasionally

some interpretation is necessary. What might appear to be a son, might be a

nephew, in years where this is not clearly recorded. Combine the information

from a census record, and the powerful tool of BMD is corroborated and

sometimes missing pieces can be found. Furthermore census records provide

additional information often including addresses and occupations.

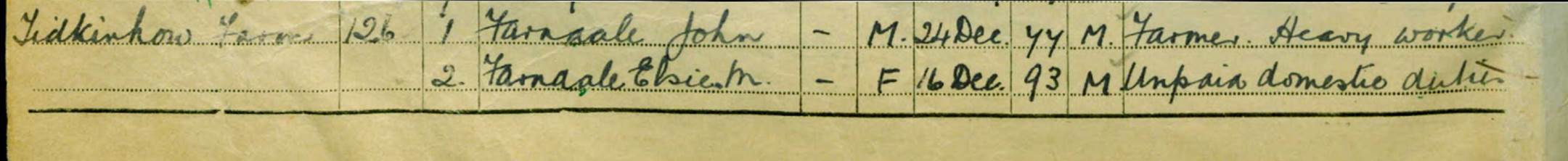

Census

records are presently available until 1921 for data protection reasons, but for

a historical journey, that is likely to provide everything that might be

needed. In addition though there was a register of occupations taken

immediately before the Second World War in 1939, which like a census record

places individuals into their family groups at that time, locates them, and

records their occupation. Furthermore, unlike the earlier census records, the

1939 records include a date of birth, and this can sometimes fill that piece of

the jigsaw where other clues have failed.

1939

Register, John and

Elsie Farndale of Tidkinhow

BMD and

census records of the tools for Thomas Gradgrind. They provide us with facts

and nothing else. They enable us to build the scaffolding for a family story.

So far, we have adopted the discipline of the scientist, starting with facts,

sometimes experimenting with the facts to find how they properly link together,

but never departing from the constraints of the historical record.

Whereas

Martin Farndale had to travel from church to church to find parish records and

build up his analysis, we can do so from a personal computer. There are

genealogical databases which are available to provide direct access to the

material, and they are almost always fully searchable. I subscribe to both Ancestry and Find my Past, which provide direct

access to available parish records and to census records. They will provide

links to the material itself, but also provide search tools, to assemble all

the relevant material. They make the task much easier. There is also a free database

of family records called Family Search, which

is the resource of the Mormon Church in Utah, which does also provide access to

a wealth of information. The International

Genealogical Index (ďIGIĒ) is the main database of their genealogical

records, originally created in 1969.

Dipping

into wider record sets

The

scientific journey does not end there, but it will probably make the research

easier in the longer term, to hold back from venturing beyond BMD and census

records, until a reasonable effort is made to compile the wider family tree.

There are

tools which further enhance the preliminary exercise of building up the basic

structure. For instance Find a grave

is a database of millions of memorials across the world, and if nothing else it

is worth searching against the surname of interest to see what it reveals. It

can provide further building block information, and may provide additional

historical narrative, including a photograph of an individualís memorial.

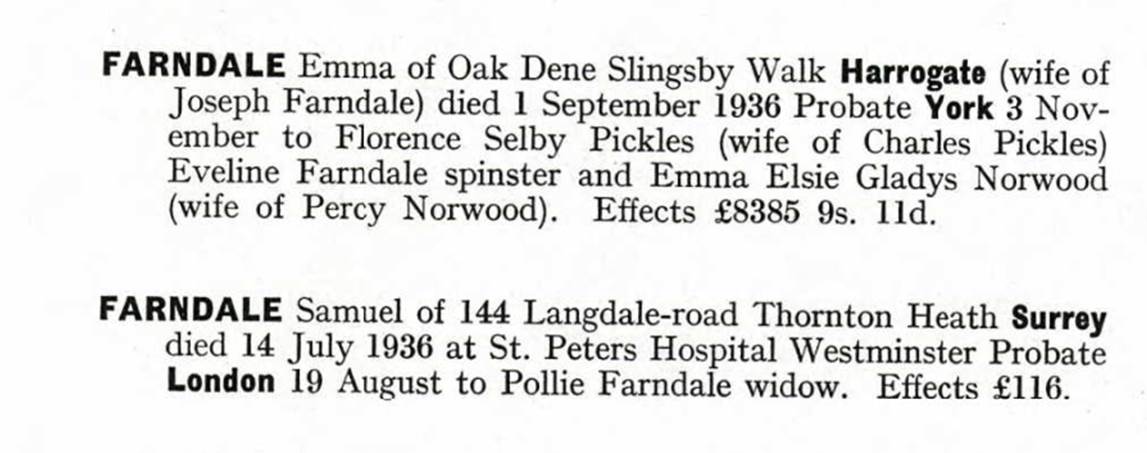

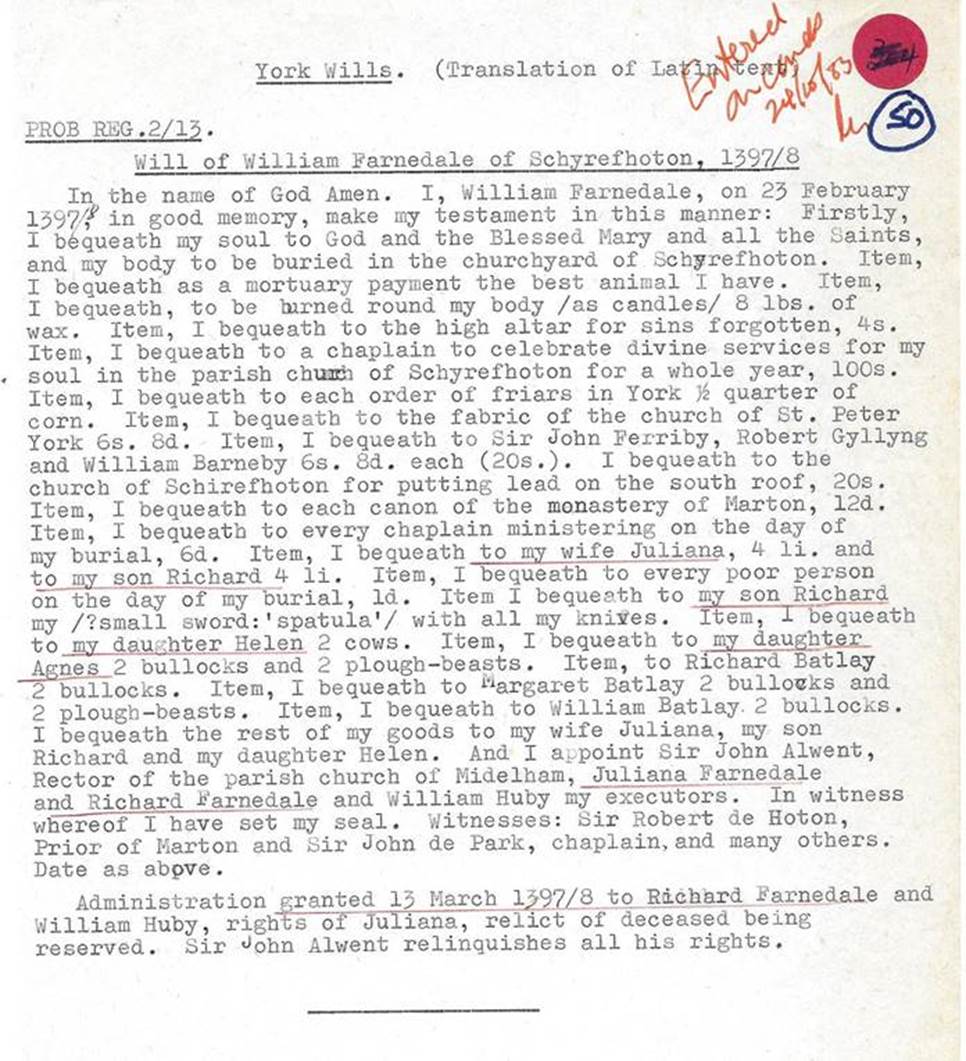

Wills and

probate records are a very helpful. Probate records generally confirm the exact

date of death and residence and often include details of next of kin.

Wills can

provide much more detailed narratives, that not only provide evidence of family

tree relationships, but can provide extraordinary details of a personís life.

The will of Richard

Farndale (1357 to 1435) includes a description of his impressive armoury of

military equipment, which transports us to a world of medieval warfare.

†

†

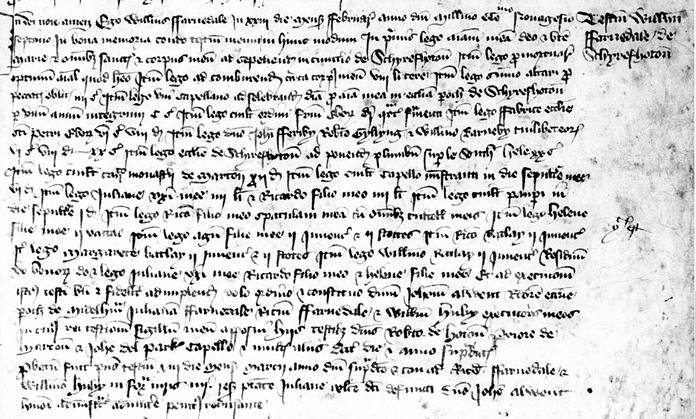

The Will

of William

Farndale of Sheriff Hutton, 1397

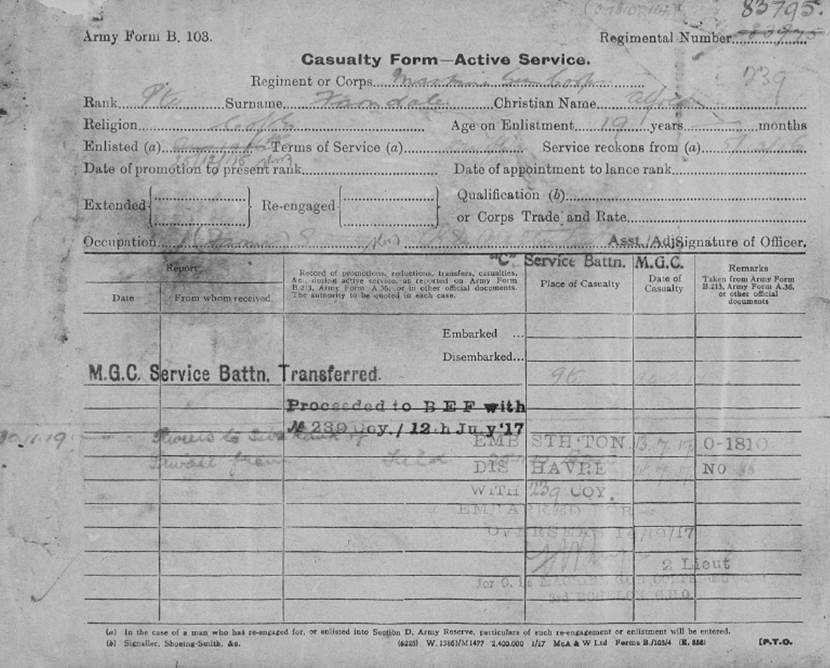

There are

extensive military records available, which sometimes provide access to

Victorian military records, and are rich in detail in the twentieth century,

providing a wealth of information about servicemen who served in the first and

second world Wars. They can provide descriptive details of height and eye

colour and confirm the date of enlistment and the units in which they served.

Sometimes they provide a record of theatres of service. These rich records sets

can then be enhanced by exploring the history of particular units at the places

where an individual was known to have served, including war diaries and other

accounts of particular battles.

Alf

Farndaleís transfer papers, 1917

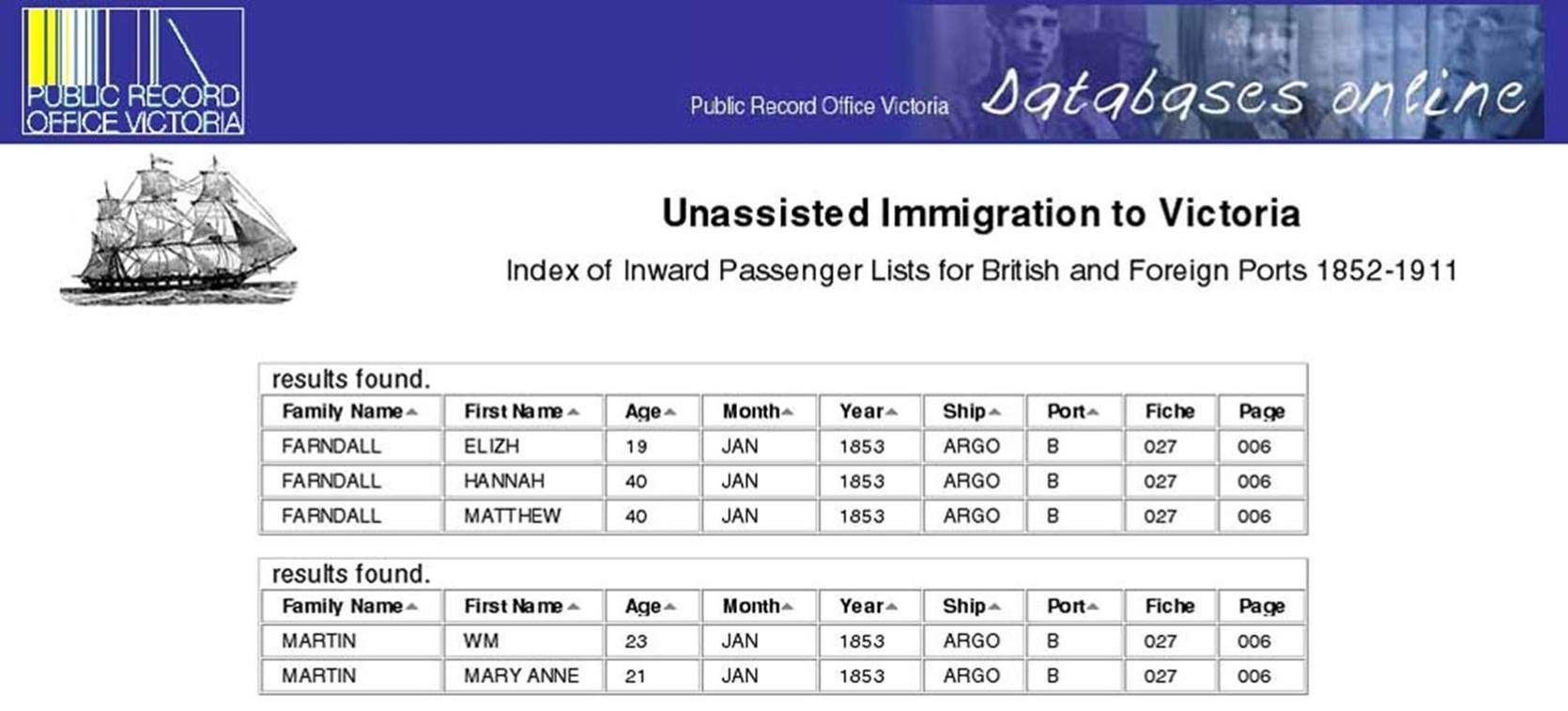

Emigrations

were often recorded in the passenger records of sea voyages.† These can provide important material in a

familyís story. I have found records of the emigrations of my grandfather and

his siblings across

the Atlantic at about the time of the Titanic sinking. It can be

interesting to explore the history of the ships in which they sailed. A search

of the Ellis island

database might reveal individuals who emigrated to the United States.

The

emigration of the Australian

Farndales in 1853

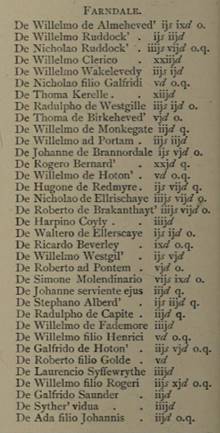

Taxation

records have provided a valuable source material from the earliest times. The

Yorkshire Lay Subsidy of 1301 provides an invaluable glimpse into all the

tenants of Farndale at the beginning of the fourteenth century.

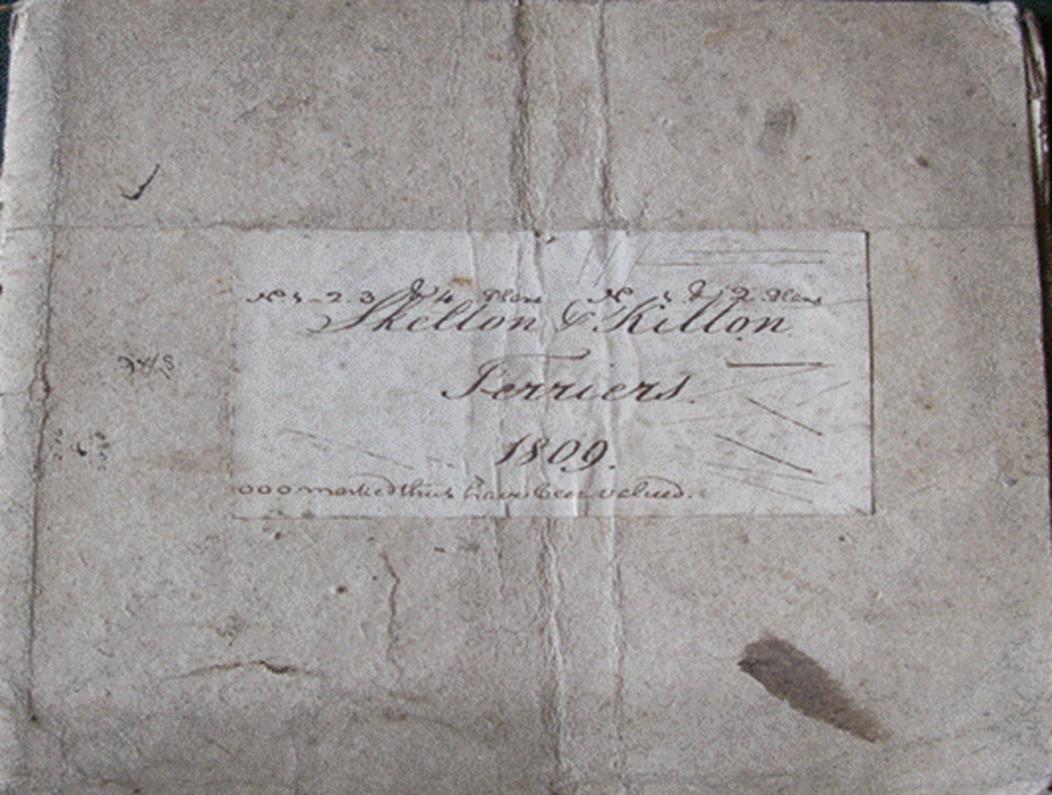

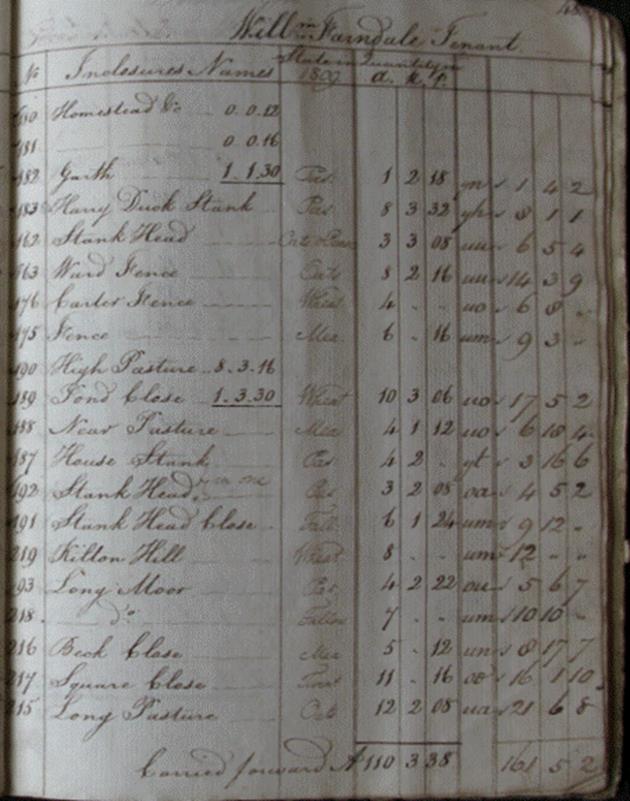

Hearth tax

returns provide evidence of relative wealth in the seventeenth century. Land tax assessments

and Church Rates take the story into the eighteenth century, as do overseers accounts

and churchwardens accounts. Extraordinary insights can be gathered from

terriers, which recorded field names, acreages and land usages within tenanted

farms, as well as value and rent.

†

†

Terrier,

1809, William

Farndale

The Official

Gazette provides access to notifications of many official events from

bankruptcy to honours. The

London (and Edinburgh and Belfast) Gazette provides free on line access.

The National Archives (often

referred to as ďTNAĒ) comprise the national collection of historical records at

Kew. They provide access to a wealth of historical information, manorial

records, and medieval record sets, and includes helpful guidance to make best

use of the collection. Many records are available online and the site gives

access to a monthly limit of records after free registration.

County

Records offices are also helpful and the Farndale Story has benefitted from the

resources provided by the North

Yorkshire County Record Office, Malpas Road, Northallerton, North

Yorkshire, DL7 8TB, open Tuesday to Friday, 9.30am - 4.30pm. The

catalogue can be searched online, but it might be necessary to visit in

person to access material which is often still available in hard copy form,

including microfiche storage.

Itís not

really necessary to visit Parish Churches to access parish records, but many

churches do still have books of records which are available to flick through,

if you visit a relevant church. Church records can often help to identify

relevant gravestones, to avoid painstakingly viewing every gravestone in a

relevant church to try to find an ancestor. Sometimes history groups have

formed and helpfully catalogued all the parish records of a relevant parish.

For instance the Skelton

History Group provides a searchable database of that parishís registers of

births, marriages and deaths. This should coincide with the information that is

likely to be available in datasets of such organisations as Ancestry and Find

my Past, but sometimes they provide an alternative course from which to find

something new.

There are

similar organisations which provide a focus for family research and membership

might provide access to new streams of information. An example is the Cleveland Family History Society.

Similarly

there are helpful local history societies, which can help to fill gaps, such as

the Skelton History Group,

and the invaluable timeline, Skelton-in-Cleveland

History, created by Bill Danby and which is maintained on line by the

History Group.

Another rich

source of primary historical information can be found in local museums, such as

the

Kirkleatham Museum; the Yorkshire

Museum at York, and the Land of Iron

at Skinningrove.

In general

these sources help to build on the scaffolding of family relationships, to

start to bring out the activities and experiences of a family story.

Newspapers

Newspapers

are an invaluable source and Find my Past provides access to The British Newspaper Archive

and Ancestry to Newspapers.com,

which are both a rich resource of archived newspaper records. It is worth

holding back a newspaper search until a little later in a genealogical project.

For a name like mine, it is possible to follow a generic search for my surname,

and to recover multiple records which are all potentially valuable. If the

structure of the genealogy is already completed, it is much easier to match

newspaper record to individual. The alternative is to try to search for

everything that can be found about a particular individual, but that can

sometimes be challenging.

The result

is the recovery of a rich source of stories, which perhaps more than any other

records, can bring the family story to life. There are for instance extensive

records of individuals such as Joseph

Farndale, the Victorian Chief Constable of Birmingham and William

Edward Farndale, the President of the Presbyterian Church, from which a

detailed life story can be built.

Obituaries are

very useful when they can be found, as they summarise a whole life.

DNA

It is now

possible to unlock ancestral secrets by spitting into a test tube and waiting a

few weeks for its analysis. Ancestry will do this for you. You may shy away

from the data protection implications of sharing your DNA, though there are

some assurances given about that. The exercise is unlikely to reveal much that

you canít uncover from the more thorough exercise of genealogical research. Yet

it can be interesting to understand the geographical makeup of your genes,

which can be split between your male and female lines of descent.† The exercise can also connect you with other

relatives who have done the same thing, and who have some interest in their

family history too.

Organising

the data

It is likely

that it wonít be too long before an exercise in genealogical research will

recover an extremely large dataset. Some organisation to continued research

then becomes a necessity. In the early days Martin Farndale used card indexes

to try to make sense of the family records. He then settled on a directory

which listed every individual member of the family in the order of their birth.

The Farndale Directory still

exists and it is a part of the Farndale Family Website. It is quite a useful

tool to enable someone interested to find an individual they know, perhaps

their direct relative, and then follow relationships through the website.

We quickly

found that giving each individual a reference number is helpful. It is best to

do this at a later stage when most of the individuals have already ben found, so that the numbering system can be

chronological from the earlier records. Each individual member of the family

has a reference number starting FAR00001. That means that the computer will

sort individual records into their chronological order. Gaps in numbering are

left to allow for some later additions and when there are no gaps left, individuals

can be added by giving them a prefix, FAR00301A, FAR00301B and so on. Sometimes

I have started to work on a related family and explored that family in more or

less depth. For my grandmotherís family I have therefore used a similar system,

but starting BAK00001.

I soon

progressed to use Microsoft Excel to sort the primary data about each

individual. I might have used Microsoft Access which was designed as a

database, but Excel does much the same thing and I find it more suitable. My

Excel Chart has columns for the Reference number (FAR00001 etc); the last

review date (so I know when I last worked on an individual record; Name; Sex;

Geographical locations with which the person was associated; Comments to allow

some free text; the Family Line into which I have placed the person; the

Directory Volume in which the person appears; Occupations; birth date; marriage

date; death date; Motherís surname; Wifeís Christian and surname; Where buried;

Significant emigration; Military service; and a column for issues needing more

work/resolution.

It is a

brilliant tool as it can be easily organised in different ways and searched

against. For instance the whole dataset of individuals can be searched for

wivesí maiden names, when trying to identify a new individual whose motherís

maiden name is known. When I find a newspaper article the excel table generally

pieces together some clues to identify who it is in seconds.

The

relationships between an extended family through time can give rise to a very

large family tree. Both Ancestry and Find My Past provide tools to organise

data into family trees and I use both as organisational tools to help explore

the structure of the whole family. However I have also found that it is useful

to break the family down into family lines, which are logically structured

generally to coincide with new geographical locations where sections of the

family formed themselves into new branches. I have thus divided the Farndale

family into 84

family lines, which can each be managed more easily to better understand

the narrative of each part of the family. They can be drawn together by the interface chart,

which links the family lines together in a master family tree.

This creates

a hierarchy from the Interface Chart to each Family Line to each Individual.

Presenting

the story

I explored

genealogy programmes, which form family trees and provide databases to organise

information, but found them too restrictive, because in the end they provide a

finite structure within which the family story has to be told. I concluded that

the best approach to display the family story is to revert to the most basic of

contemporary tool, and that is word processing software which seems to have

universally adopted the form of Microsoft Word. By starting with a generic

tool, I have found that I can build the family story exactly as I want to tell

it.

There is one

simple invention in the evolution of computer programmes, which makes

everything work. That is the hyperlink. A hyperlink provides the chance to

build up complex stories by linking related stories to each other. Instead of

the constraints of a single page of text, or even the flow of a single book, a

story can be told in easily digestible chunks, from which hyperlinks will lead

to related parts of the story, which can be visited at the whim of the reader.

In a complex story like a genealogy that quickly builds up to multiple paths,

which creates a whole cohesive story, but one which has a multiplicity of

different paths. It can be consumed by the particular interest of the reader,

not being overwhelmed by too much information at once, but digesting each

stage, and moving on to the next stage in a way that best suits them.

The simple

starting point is to create a page

for every individual who makes up the whole family. I create a page even

for the child who died as it was born, and didnít have the time to construct a

complex story. Each page includes details of the individualís parents, their

spouse, and their children and each is linked by a hyperlink that will take you

to their relatives story. It therefore becomes possible to follow your own

direct lineage through each of your direct relatives, to the earliest

characters who ap[pear in the family story. If you choose you can follow side paths

through uncles and aunts to explore other parts of your lineage.

I save each

word document not in the usual fashion of the .doc format, but as a webpage

ending .html. That immediately unlocks the usual constraints of a printable

page, and allows the look of a page to be enhanced with colour and structure.

More importantly, in this format, the page can be published on the internet, to

be shared with others who might be interested.

Each family line can

be portrayed in similar fashion, showing their family tree structure, with

hyperlink built in to the family trees to link directly back to individual

pages.

As the

structure of the individual pages and family lines was built up, a story

emerged, which could be told in the form of the

Farndale Story, which I chose to structure as a time travellerís portal to

pages which each tell a part of the story, which I wrote in consecutive Acts,

with explanatory pages to expand each era of the story.

The exercise

of posting the story onto the internet involves first purchasing a domain name

Ė I use names.com for that. You then need a

server on which to upload your work. A friendly IT specialist helps me with

that. I use a tool called FileZilla

to upload material from my computer onto the server.

When

organising the material its important to keep it all

together in a single folder. I use a single folder for my whole family website

material, which can then be divided into folders for individuals, family lines,

the narrative story pages etc.

Once the

structure is up and running I just post the material up onto the website from

time to time and it all works well. This structure, based on simple word

documents, creates a project with the scope to develop indefinitely and I much

refer it to the constraints of a bespoke genealogy programme.

Context

As the

family story has grown, it is helpful to explore Local History and wider

historical paths. Sometimes this is through web searches or museum collections.

Sometimes it is through journeys to the places that feature in our story.

Sometimes the family story provides a route into history books, which take on

far more meaning than they would if read in isolation. Those journeys provide

context, which in turn refine the family story.

Archaeological

records are particularly useful for the earlier history. The

Ryedale Historian is a useful source for my own family story, as is the Yorkshire Archaeological & Historical

Society, and the journals and other material which it produces.

Historical

Novels can provide some gloss and provide context for rural communities. They

can help tell the story, to bring life to the underlying historical evidence.

Contemporary works paint a picture of the experiences of the time, and can add

a new perspective to genealogical story telling. Works which can be helpful in

this regard are the books by Thomas Hardy; by Charles Dickens including David

Copperfield, The

Pickwick Papers, Little Dorrit

and Hard

Times. Middlemarch,

1869, by George Elliot, is set in a fictional English Midlands town in 1829 to

1832, and topics include the status of women, the nature of marriage, idealism,

self-interest, religion, hypocrisy, political reform, and education, the 1832

Reform Act, early railways, and the accession of King William IV, medicine of

the time and reactionary views in a settled community facing unwelcome change. Lark

Rise written in 1939, Over to Candleford in 1941 and Candleford Green in 1943, by Flora Thompson, are

descriptive of late nineteenth century rural communities in Oxfordshire. Cider

with Rosie, 1959, by Laurie Lee, is a record of a childhood in

Gloucestershire in the period just after the First World War.

If you start

with historical facts, and then work on context and tools which help to fill

the gaps and bring out the story, a fuller picture will emerge, which will help

to capture the spirit of the family story.