Act 5

Scandinavian Kirkdale

c 793 CE to 1066

Kirkdale Minster

Kirkdale under Scandinavian influence

It might be

thought that the period of Viking invasion which impacted heavily on northeast

England from the mid ninth century CE, would have been devastating for our

ancestors. However the lands of Kirkdale were nestled at the protective edge of

the moors and dales, and were not at the heart of Viking violence. Whilst they

cannot have escaped disruption and some experience of violence, the cultivated

region seems to have been quickly subsumed into a new Anglo-Saxon-Scandinavian

culture.

|

This

is a new experiment. Using Google’s Notebook LM, listen to an AI powered

podcast summarising this page. This should only be treated as an

introduction, and the AI generation sometimes gets the nuance a bit wrong.

However it does provide an introduction to the themes of this page, which are

dealt with in more depth below. |

|

As

a scene setter, you might enjoy a dramatic interpretation of the Viking

threat. It is fictional, but might help to set a scene. |

Scene 1 – Becoming Scandinavian

Attack

The best

known Viking raid on the British Isles was the attack on Lindisfarne off the

modern Northumbrian coast in 793 CE. There had in fact been attacks from

Scandinavia before that time, mostly further to the north.

The

Judgement Day Stone, Lindisfarne

The effects

of Viking raids on the indigenous population, who were exposed to violence and

enslavement, must have been profound. Opportunistic raids by Viking warrior

seamen continued over the next half century. By 835 CE larger Viking fleets

began to engage in more significant confrontations with royal armies.

A great

Scandinavian army arrived in 865 CE. The Anglo Saxon

Chronicle, written in the age of King Alfred, recorded that year that

there sat the heathen army in the isle of Thanet, and made peace with the

men of Kent, who promised money therewith; but under the security of peace, and

the promise of money, the army in the night stole up the country, and overran

all Kent eastward. By 867 CE, the army went from the East-Angles over

the mouth of the Humber to the Northumbrians, as far as York. And there was

much dissension in that nation among themselves; they had deposed their king

Osbert, and had admitted Aella, who had no natural claim. Late in the year,

however, they returned to their allegiance, and they were now fighting against

the common enemy; having collected a vast force, with which they fought the

army at York; and breaking open the town, some of them entered in. Then was

there an immense slaughter of the Northumbrians, some within and some without;

and both the kings were slain on the spot. The survivors made peace with the

army. The same year died Bishop Ealstan, who had the

bishopric of Sherborn fifty winters, and his body lies in the town. Given

the proximity of York, this must have been a traumatic time for the region.

However, by 876 CE Healfdene shared out the land of the Northumbrians, and

they turned to ploughing and making a living for themselves. Place name

evidence of settlement, especially in North Yorkshire, is plentiful.

By the late

ninth century there was an increasing influence of Scandinavian culture

including upon the language. Many words of modern use in local dialect have

Norse origins, including dale, from the Norwegian ‘dalr’,

valley; beck, stream and fell, mountain.

It is likely

that rather than a wholesale transplanting of Scandinavian culture into the

Anglo-Saxon world, the old Anglo Saxon world continued, but increasingly

absorbed new traditions and ideas to create an Anglo-Saxon-Scandinavian

culture, especially in the region around the new Scandinavian heart of Jorvik.

|

The

Scandinavian centre of northern England |

|

A reconstructed journey into Scandinavian Yorkshire

and a glimpse of Scandinavian objects which tells its story |

Settlement

For the

lands around Kirkdale

the evidence of the early Scandinavian period is slim. Whilst our

ancestors there might have witnessed unrest, disruption and violence, Kirkdale was off centre to

the known locations of Danish upheaval. In fact Kirkdale might have found

itself with more responsibility over an increasingly dispersed population. By

the time the Scandinavian government was more firmly established at Jorvik, Kirkdale might have become

directly associated with the city, and by the later Scandinavian period, the

local elite had acquired property in York.

It therefore

seems likely that the home of distant ancestors of modern Farndale family was a

place of general stability, and likely political influence for most of the

thousand years from the Roman period to the Norman. This stability probably

continued through the Scandinavian period, perhaps with some violent and

unstable interludes.

Scene 2 – Thinking like a

Scandinavian

Rebuilding

The

archaeological record shows that the old church of Kirkdale was destroyed by

fire, probably at about the turn of the first millennium. It had previously

been thought that the church might have fallen during the Viking period, but it

seems more likely that the church suffered a fire perhaps not many years before

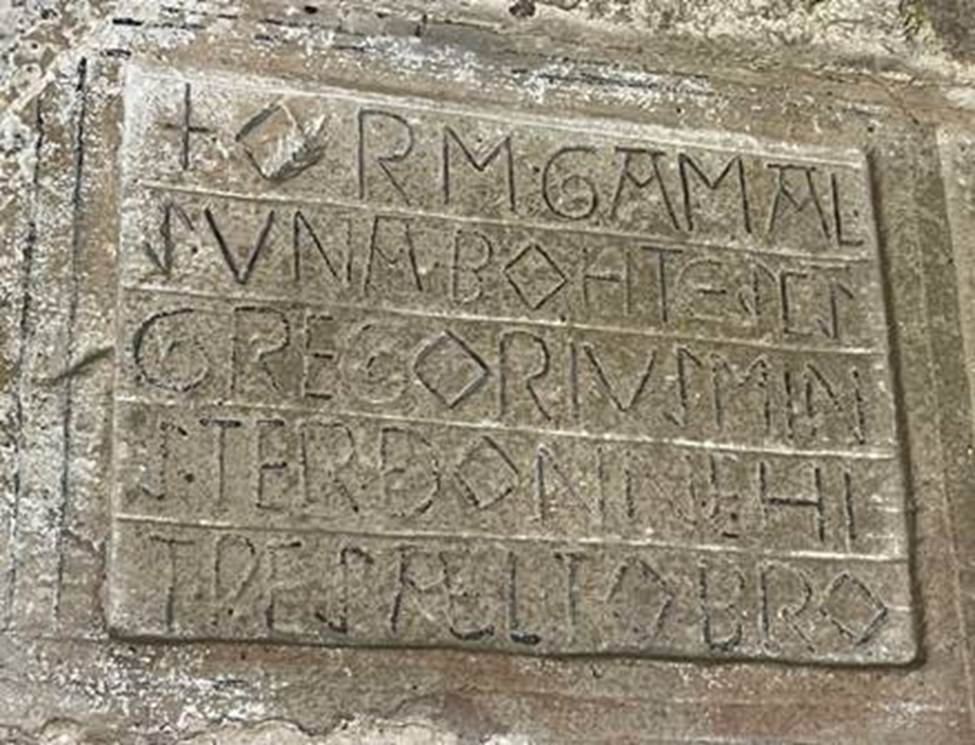

Orm Gamalson, as he recorded on

his sundial, rebuilt Kirkdale Church in about 1055.

|

Anglo-Saxon-Scandinavian Kirkdale Kirkdale

in the Anglo-Saxon-Scandinavian period from about 800 CE to 1066 |

|

The

powerful figure at the heart of the aristocracy, who rebuilt Kirkdale and put

our ancestral lands firmly onto the national political stage |

|

A unique treasure whose secrets transport us into the

world of the eleventh century upon which you can stare today, imagining

direct ancestors who did the same a thousand years ago |

Although

we’re not certain that the sundial

was built into the church during the 1055 building work, it’s likely that it

was, possibly in its current position.

The south

doorway with the sundial

The original west doorway which was part of Gamal’s rebuilding

The

sundial’s inscription refers to Edward the Confessor and to Tostig, the son of

Earl Godwin of Wessex and brother of Harold II, the last Anglo Saxon King of

England. Tostig was the Earl of Northumbria between 1055 and 1065 who rebelled

against his brother Harold Godwinson to join the Dane, Harold Hardrada in the

invasion of northern England which immediately preceded the Battle of Hastings.

It was therefore during that last relatively peaceful decade, immediately

before the Norman conquest, that Orm, son of Gamal rebuilt this Church,

dedicated to St Gregory and when he did, he placed that sundial in the doorway.

Our

ancestors found themselves at a place of historical significance in the year

1066, not so far from the first of the two great battles of that year, the most

significant year of change in English history. And our ancestors’ home had

direct cultural and political links with the world of Edward the Confessor,

Tostig and Harold Godwinson and others, who were the main actors in that story.

Orm Gamalson was clearly a substantial figure,

and the place he chose to articulate his power was Kirkdale. Kirkdale had political significance in this

pivotal historical episode.

An

Anglo-Saxon-Scandinavian World

The sundial is written in the Old

English of the late Anglo Saxon period.

“Orm the

son of Gamal acquired St Gregory’s Minster when it was completely ruined and

collapsed, and he had it built anew from the ground to Christ and to St Gregory

in the days of King Edward and in the days of Earl Tostig”.

The sundial

itself bears the inscription “This is the day’s sun circle at each hour”

and then “The priest and Hawarth me wrought and

Brand”.

There is a

single Old Norse word, solmerca, which means

sundial. The old Norse word might just have been borrowed from the Norse

language. The Scandinavian names, particular Orm, have been Anglicised from the

Norse Ormr. So when you first interpret the

words of the sundial, it doesn’t seem particularly Scandinavian.

It would

appear that Orm rebuilt an ancient, ruined church, which he re-dedicated to St

Gregory, rejecting the disorder of the earlier Viking attacks, in order to

restore the Christian traditions of the pre-Scandinavian period. The sundial

might reflect a rejection of Scandinavian culture and a recovery of the earlier

Anglo-Saxon Christian period.

And yet,

there is tangible evidence of Scandinavian culture on the local community.

The

inscription provides the names of Orm Gamalson, the elite landholder; of a

priest called Brand and of Hawaro, probably an

artisan. It therefore records a reasonable cross section of society. There is

little doubt that Orm Gamalson

came from a Scandinavian tradition and probably was of Scandinavian descent.

Brand was the priest and was likely to have been responsible for the design of

the sundial. Brandr was a common personal name from Denmark and Iceland.

Hawaro was probably the craftsman, responsible for

the inscription. This is also a Scandinavian name, as in the Icelandic saga of

Hávarður of Ísafjörður.

The use of a

Scandinavian name might evidence Scandinavian descent, or simply an increased

use of fashionable Norse names. Yet the way that names were used in this period

followed strict genealogical form. Orm Gamalson had a father and son each

called Gamal son of Orm, and his grandfather was probably also Orm Gamalson.

Names were used in a carefully controlled manner. They bound families together

and created a network of obligations. Analysis of the Domesday Book shows the

proportion of Old Norse to Old English names was more than two to one. The

highest of all such names was in Yorkshire and the Ryedale Wapentake, which

included Kirkdale, had a higher than county average. There were 92 Old Norse to

8 Old English names. Although Norman names were adopted in large numbers after

the conquest, the total number of different names adopted from the

Normans was very small. Yet the use of Norse names at the time of the Norman

invasion reflected a large number of different names which were used.

By the tenth

century there was extensive interaction between England and Scandinavia.

In 1016 the

Danish King Cnut assumed the throne from his conquering father Swein Forkbeard and granted estates to many of those who

had supported the reconquest. Orm’s father Gamal probably benefited from this

redistribution of land. In later marrying Ealdred’s daughter Aethelthryth, Orm

became embedded into the Scandinavian and English elite society.

Old Norse

was still spoken at the eve of the Norman Conquest, particularly in Yorkshire.

Old Norse speakers continued to arrive, with another influx during the reign of

Cnut. The Old Norse language flourished in Cnut’s court. In the north there was

a rich culture of elite poetry, read in the Old Norse language for English

audiences.

The language

of the Kirkdale sundial was Old English, as were four similar inscriptions in

the area at Aldbrough (Ulf had this church built for his own

sake and for Gunnvor's soul), the Traveller’s Clock at Great

Edstone (Loðan

made me; Orlogium Iatorum, “The Traveller’s Clock” ); Old Byland (Sumarleoi’s house servant made me); and St

Mary Castlegate, York (and Grim and Aese raised this church in the name of the holy Lord Christ

and to St Mary and St Martin and St Cuthbert and All Saints. It was consecrated

in the … year in the life of …). Yet Old Norse had never become a written

language using the Roman alphabet. The two written traditions were Latin and

Old English. Since Old English and Old Norse were related languages, the

Scandinavian elite did not worry themselves about using existing traditions of

Old English and Latin for the written record.

Whilst

Scandinavian culture was originally pagan, by the tenth century the

Anglo-Saxon-Scandinavian community had adopted Christianity. There is extensive

evidence of religious piety particularly through Scandinavian inspired stone

sculpture. There are at least nine examples of such inscription at Kirkdale,

apart from the sundial. They were probably funerary monuments for the new local

Scandinavian elite.

Kirkdale is

a place where Scandinavian, Latin and English traditions met and found

expression. It was at the heart of the Anglo-Saxon-Scandinavian world.

A concept

of Time

The

sundial’s inscription, This is the day’s sun circle at each hour, takes us

into the imaginations and perceptions of our ancestors who conceived of the

sundial and looked up at it as they regularly walked through the door. It was

unlikely to have been a practical time telling mechanism, given its position on

the minster’s wall surrounded by high ground. It is more likely, particularly

given its position over the doorway into the minster, that the real purpose of

the sundial was not practical and secular, but religious and profound. Indeed

the practice was to bury the dead who had been faithful on the south side of

the church, so the exterior of the south wall was a logical place for such

symbolism.

It was

probably intended to be a symbolic reminder of temporal progression. Time was

perceived as the linear temporal space within which the world moved towards its

final judgement and dissolution. By the fourth century CE, Christian theology

had focused on God’s plans for how life on earth was lived. This brought with

it a conception of history and the passage of time.

This was an

uneasy generation of the period just after the end of the first millennium. In

1014, Wulfstan, Archbishop of York, had published his sermon addressed to

the English nation. He anticipated the coming of the Antichrist and found moral

decline in the nation. There was always some uncertainty about the exact span

of the thousand years. What was in doubt was the precise date, but not of the

fact of a Second Coming. So it is possible that Orm’s sundial created not so

long after the turn of the millennium, was recording the passing of the last of

days. If that is so, it is difficult to tell whether it was created with a

sense of foreboding, or whether it was a more optimistic symbol.

In 325 CE

the Council of Nicaea ruled that Christians should hold Easter on the same day,

always a Sunday. The computational method involved complex cycles of years. It

never worked well. Bede’s De temporum ratione

was an attempt to help calculate the dates of Easter up to the millennium and

beyond. There was a renewal of computus

learning in the late tenth and early eleventh centuries. Aelfric’s De temporibus anni was a development of Bede’s earlier

work. With guidance from texts such as Bede’s and Aelfric’s, it had become

possible for a reasonably educated cleric to make his own calculations. There

was likely to have been a network of ecclesiastical connections, leading to the

restored library at York. Kirkdale’s likely

associations with York would probably have given access to Kirkdale’s

priest, Brand, to these works.

So Brand may

have been a priest who, with Orm’s patronage, was able to articulate complex

ideas of the passage of time, reinforcing the correct calculation of time

through computus science, with a primarily

theological symbolism, inspiring our ancestors to use their time wisely and

piously, particularly against the perceived threat of an ending of time.

So when you

look at the sundial today, it is worth reflecting on what it might have meant

to a person who might be a direct but distant relative. If he or she was

contemplating time, the sundial might now be a portal across a thousand years,

to provide some linkage into our ancestor’s minds.

The

Community in the last days of the Anglo-Saxon-Scandinavian world

The Domesday

Book records two churches within the estate of Chirchebi, with one at

Kirkdale and the other being the site of Kirkbymoorside Parish Church.

It evidences

that Kirkdale by the mid eleventh century comprised ten villagers, one priest,

two ploughlands, two lord’s plough teams, three men’s plough teams, a mill and

a church living in an area of five caracutes

of land.

If you visit

Kirkdale today, walk through the gate to the west of the church and into the

field beyond. Look carefully at the ground and you will see that the field is

marked by long ridges in the grass. Ridge and furrow describes the

archaeological pattern of ridges and troughs which evidences the system of

ploughing used during the Middle Ages, typical of the open-field system. It is

predominant in the North East of England and in Scotland. Walk across the field

and imagine the community that lived there in the late Anglo-Saxon-Scandinavian

world, listed in some detail in the Domesday Book.

Go Straight to Act 6 – Game of Thrones

or

If your interest is in Kirkdale then I suggest you visit the

following pages of the website.

· The church in Anglo Saxon Times

· The Kirkdale

Anglo Saxon artefacts

· The community in Anglo Saxon Times

· The church in Anglo Saxon

Scandinavian Times

You can also

read about Jorvik.

There is a

chronology, together with source material at the

Kirkdale research Page.