Anglo-Saxon-Scandinavian Kirkdale

Kirkdale from the beginning of the

Scandinavian period in about 800 CE to the Norman Conquest in 1066

Then a short summary of its history

after 1066

Scandinavian

disruption

It had been

suggested that the minster fell into ruin, perhaps as a result of Danish raids,

long before the sundial tells us that Orm Gamalson rebuilt it. Recent

interpretation suggests this was not the case.†

There is

little evidence from the period of transition from the Anglo Saxon to the Anglo

Scandinavian period. However the archaeologists have found the presence of

graves which appear to be from the early Anglo-Scandinavian period.

There may

well have been unrest, disruption to religious observance and bursts of

violence during the early Anglo Scandinavian period. Yet Kirkdale was nested

away at the edge of the dales, far from the places where Viking upheaval is

known to have occurred. It is possible that there was a relatively smooth

transition in culture and leadership at this time. It seems possible that the

church at Kirkdale might have assumed greater responsibility for a dispersed

population around it, while a larger concentration at the settlement of

Kirkbymoorside may have become disconnected from the inhabitants around

Kirkdale.

There was

certainly a process of sub dividing previously extensive estates into smaller

units and Kirkdaleís place in that process is not

known. The ninth century was a period of fresh feudal ownership by a new elite

and the gradual reestablishment of settlements focused on manors.

When the

Scandinavian government was exercised from York,

Kirkdale might have found itself in more regular contact with York. The elite

associated with Kirkdale in time acquired property in York. This was likely to

have increased its connection to York.

|

The

Scandinavian centre of northern England |

The

Scandinavian dominance was the beginning of a period of more profound change.

It began a new sense of northern-ness, as a counterpoint to the southern

English court.

Fears for

the end of the world

Whilst

Kirkdale might have escaped the worst ravages of the early Scandinavian period,

by the turn of the first millennium in the Common Era, there was a widespread

heightened anticipation and fear of apocalypse. As the year 1000 passed, the

anticipation did not wither, only the uncertainty about the precise date when

it would occur.

Wulfstan was

appointed Archbishop of York in 1002 during

the turbulent times of fresh waves of settlement from the wicinglas,

the people of the fjord settlements. By the end of the tenth century, England

had become a sophisticated state on the European stage. Wulfstan assumed a

sophisticated model of society. However 1014 was a year of crisis. King Aetheraed had been driven into exile, expelled by Sweyn

Forkbeard who was accepted as King of the English before dying in 1014. His

young son Cnut then became King.

Wulfstan had

long served in Aethelraedís administration. It was in this context that he

wrote his sermon to the English people, Sermo

Lupi ad Anglos (Lupi being the Latin for wolf, Wulfstanís pen name).

The sermon provided a contemporary definition of morality and foreboding.

The sermon

began with a sense of foreboding. Beloved people, know that this is true. This

world is in haste and it approaches its end. And so, because of the nationís

sins, things must of necessity grow far more evil before Antichristís advent:

and then indeed they shall be appalling and terrible widely throughout the

world.

It continued,

the devil has too much led astray the nation. If we are to expect any cure,

then we must deserve it of God better than we hitherto have done. Godís houses

are too cleanly despoiled. Nor has anyone been faithful in thought towards

another as duly he should. People have not very often cared what they have

wrought by word or by deed.

He then

recounted that there was a historian in the days of the Britons called

Gildas, who wrote about their misdeeds, how they by their sins so overly much

angered God that in the end he permitted the army of the English to conquer

their lands and destroy withal the Britons power.

He therefore

continued and let us do as our need is, submit to what is right and in some

measure abandon what is not right.

|

Archbishop Wulfstanís Sermon to the English People

Wulfstanís

ominous warnings as the Millennium turned. |

Kirkdale

in the late Anglo Saxon period

The archaeologists

suggest that St Gregoryís minster might have reached its most extensive size

before it was rebuilt in about 1055. However the nave, the central part of the

church which accommodates most or all of the congregation, was not larger, so

this does not necessarily mean that there were more parishioners. It probably

continued in its original Anglo Saxon form and not Anglo Scandinavian in form.

It has been suggested that we might get some idea of the church at that time by

comparing it with St Maryís, Deerhurst in Gloucestershire.

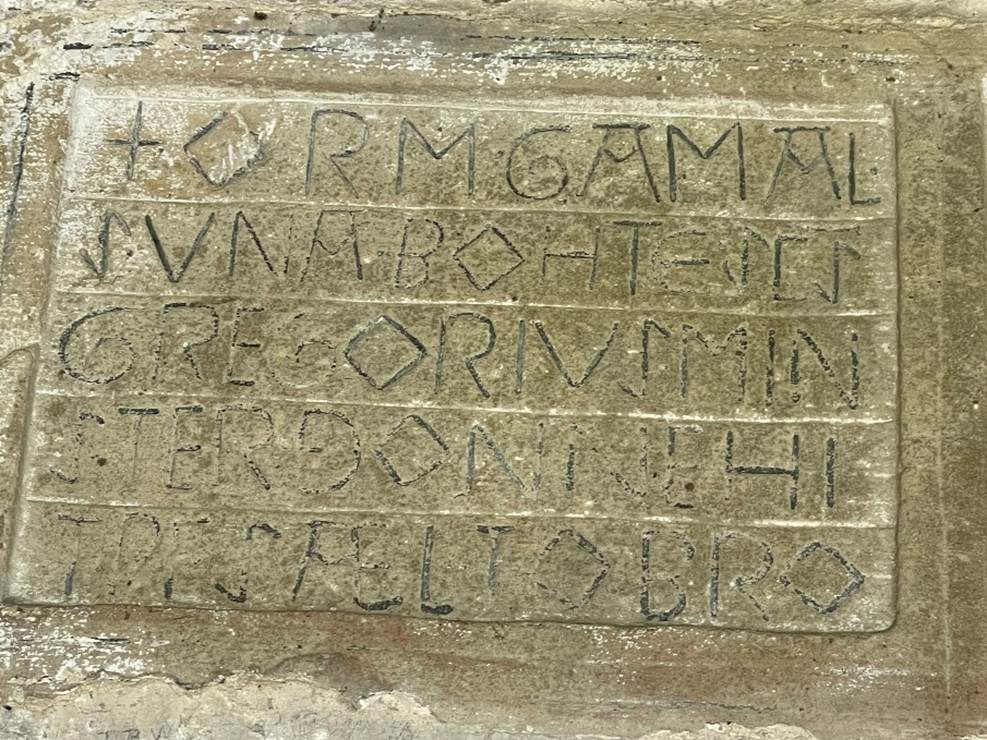

The sundial

does not make clear how long before its rebuilding Orm Gamalson had purchased the

church. We are told that he acquired St Gregoryís Minster when it was

completely ruined and collapsed. If, as seems likely, the fire occurred

shortly before it was rebuilt, then although he appears to have been an

extensive feudal landowner including of the Kirkbymoorside estate since shortly

after the invasion of Sweyn Forkbeard and Cnut in 1016, his interest in the

church itself would have been acquired towards the middle of the century.

If the fire

occurred a little earlier than that, say in the 1020s, then Orm might have had

ownership of the church for a period of time in its late Anglo Saxon form. It

is possible he would have exercised significant patronage in the last years of

development of the ancient church. Perhaps it was the activity of extensive

rebuilding work by Orm that caused the fire.

Alternatively

the minster might already have burned down before Cnutís invasion and before

the Orm family interest.

The

Phoenix emerges

We do know

that there is archaeological evidence of burning. The church appears to have

been destroyed by fire, most evident in excavations on its south side. The

interior fittings of wood and cloth were inflammable and it seems most likely

that the fire occurred in the early to mid eleventh

century, shortly before it was rebuilt and may just have been an accident.

When Orm

rebuilt Kirkdale minster, with its

sundial created by Hawarth, and served by the

priest Brand, this was an ancient, ruined, minster church whose cemetery was

still used by the local people for the burial of their dead.

|

The

powerful figure at the heart of the aristocracy, who rebuilt Kirkdale and put

our ancestral lands firmly onto the national political stage |

|

A unique treasure whose secrets transport us into the

world of the eleventh century upon which you can stare today, imagining

direct ancestors who did the same a thousand years ago |

Disturbed

graves at the west exterior of the church reflect the chaos of the fire and its

aftermath. The area of Trench II became a workshop for the rebuilding work.

Debris from the church was taken to this area and later components of the new

building programme were prepared within the shelter of a shed like building.

The destruction of the old church was so extensive that much of the previous

structure required to be rebuilt, but the previous church seems to have been

used as the basic template for the new foundations.

No evidence

has been found of a residence at this time, so we donít know where the priest

lived.

What

survives of Orm's church in the existing visible fabric appears to be the

south, west, and what remains of the east walls of the nave; the archway in the

west wall of the nave (now opening into the much later west tower) which

probably formed the original entrance to Orm's church; and the jambs,

angle-shafts, bases and capitals of the arch which leads from the nave into the

chancel. The latter archway is some four centuries later than Orm's church, but

it appears that the masons who were responsible for it re-used what they could

of an earlier chancel arch. It is therefore reasonable to infer that Orm's

church had a chancel, though not all Anglo-Saxon

parish churches did. It was probably a great deal smaller than the existing

one.

Much of the

present nave in undoubtedly Ormís building. The western entrance arch and the

responds of the chancel arch belong to that period. Old masonry including grave

slabs and crosses, was later used in the west and south walls.

It was the

Scandinavian named Orm who rebuilt the minster. Kirkdale does not appear to

have suffered Viking destruction, but Scandinavian reconstruction.

Sir

Herbert Edward Read, art historian, poet and critic was born at Kirkdale

and wrote a poem about Ormís church in his collection, A World within a War:

|

I, Orm,

the son of Gamal Found

these fractured stones Starting

out of the fragrant thicket The

river bed was dry |

The

rooftrees naked and bleached, Nettles

in the nave and aisleways, On the

altar an owlís cast And a

feather from a wild doveís wing |

There

was peace in the valley; Far

into the eastern sea The foe

had gone, leaving death and ruin And a

longing for the priestís solace††††††††† |

Fast

the feather lay Like a

sulky jewel in my head Till I

knew it had fallen in a holy place Therefore

I raised these grey stones up again |

The years

after the Conquest

Although the

story of our familyís journey, of which this website tells, departs in its

direct interest with Kirkdale after the Conquest, the family shares much of its

story over the following centuries.

Walter Espec

encouraged the founding of the Cistercian abbey at Rievaulx in 1131. These austere

monks sought detachment from the world, in contrast to the Benedictines and the

Augustinians. A breakaway group from St Maryís Abbey in York established

Fountains Abbey and Kirkham Priory. The twelfth century boundaries of Rievaulx

suggest that Kirkdale was an island amidst abbey land. By this time

Kirkdale was clearly attached with Welburn, a section of the Kirkbymoorside

estate. Kirkdale was by then surrounded by abbey lands.

Roger de Mowbray granted the church to

Newburgh Priory, who held it until the dissolution. The field to the immediate

north of Kirkdale Church which retains prominent earthworks of ridge and

furrow, evidence that this field was in arable use by the twelfth century, although

we have already noted its arable use long before that.

At about the

same time as the

Farndale grant in 1154, Roger granted the whole of the vil

of Welburn with six bovates of land (but excepting the Church of Kirkdale) to Rievaulx. This land had been in the

possession of the Augustinian priory of Newburgh.

A scheduled

site at the farm still named Skiplam Grange, situated

above Hodge Beck not far north-west of St Gregoryís Minster, preserves an

earthworks, associated buried remains and some above-ground remains of

buildings from the grange maintained there by Rievaulx Abbey up to the date of

the Dissolution. Skiplam was part of the large grant

of land given to Rievaulx Abbey by Gundreda d'Aubigny between 1144 and 1154 and later confirmed by her

son Roger de Mowbray. This grant included some land in cultivation along with

previously unexploited land which the abbey was allowed to assart,

or improve and bring into productive use, as they wished. By the time of Abbot

Ailred of Rievaulx (1147-1167), Skiplam was operated

as a grange.

Under Pope

Nicholasí taxation of 1292, Kirkdale was taxed at £23 6s 8d.

The

Cistercians obtained papal freedom from payment of tithes on land which they

cultivated themselves. The Cistercians tenaciously maintained their tithe

privileges.

In 1432, the

prior and convent of Newburgh brought a case in the consistory court of York

against Robert Hewlott and Richard Page for non payment of tithes of coppice wood, by virtue of their

possession by that time of the parish church of Welburn. The records of the

case provide a description of the parish church at Kirkdale at that time:

The

parish church of Welburn, otherwise known as Kirkdale, built and dedicated in

honour of St Gregory, of the said diocese, which has been canonically united,

annexed and appropriated to their said priory [Newburgh] to their own uses.

He

submits and intends to prove that for the whole periods stated above there was,

was accustomed to be, and is, in the said diocese of York, a certain parish

church with the cure of souls, universally and commonly known as Welburn or

Kirkdale. It has well known boundaries by which it is distinguished, divided

and separated from the other neighbouring parishes. It has a goodly number of

parishioners of both sexes, a baptismal font, cemetery, and other attributes of

a parish church.

He

submits and intends to prove that the right to take an enjoy tithes of whatever

kind, both personal and predial, and great and small, and especially tithes of

coppice wood issuing from whatsoever places within the parish of the said

church [of Welburn] otherwise

known as Kirkdale, and the boundaries, borders and places liable to tithe

located within the parish belonged and belongs under common law, by sufficient

legal right and praiseworthy custom, which has been observed peacefully and

inviolately, to the parish church of Welburn, otherwise known as Kirkdale, and

the said religious men, the prior and convent, and their monastery or priory in

the name of the said church.

On 23

January 1539, Newburgh was dispossessed of Kirkdale. This was no doubt part of

the Reformation redistribution.

†

†

Go Straight to Chapter 3 Ė

Scandinavian Kirkdale

or

If your interest is in Kirkdale then I suggest you visit the

following pages of the website.

∑ The community in Anglo Saxon Times

∑ The church in Anglo Saxon Times

∑ The Kirkdale

Anglo Saxon artefacts

∑ The community in Anglo Saxon Times

You will

find a chronology, together with source material at the Kirkdale Page.