|

|

Newcastle

Historical and geographical information

|

|

Dates

are in red.

Hyperlinks

to other pages are in dark

blue.

Headlines

of the history of the Newcastle are in brown.

References

and citations are in turquoise.

Contextual

history is in purple.

This

webpage about the Newcastle has the following section headings:

- The Farndales of Newcastle

- Newcastle

- South Shields

- Jarrow

- Links,

texts and books

The Farndales of Newcastle

The following Farndales were associated

with Newcastle and South Shields: Jane Ellen Farndale (FAR00458);

John Willie Farndale (FAR00591);

Albert Farndale (FAR00604); Georgina

Farndale (FAR00679);

John Arthur Farndale (FAR00723);

Thomas Farndale (FAR00732);

Joseph Farndale (FAR00739);

Elizabeth Farndale (FAR00758); William

Farndale (FAR00770);

James Farndale (FAR00784);

Emily Farndale (FAR00802);

William A J Farndale (FAR00829);

Margaret L Farndale (FAR00838);

John W Farndale (FAR00854);

Catherine Farndale (FAR00864); George

T Farndale (FAR00871);

Barbara Farndale (FAR00877);

William Farndale (FAR00893);

Janet Farndale (FAR00906);

George H A Farndale (FAR00926);

John H Farndale (FAR00940);

John Farndale (FAR00978);

William Farndale (FAR01013);

Denise Farndale (FAR01020);

John Anthony Farndale (FAR1021);

James Farndale (FAR01022);

John W Farndale (FAR01023);

Janet C Farndale (FAR01025);

Joseph W Farndale (FAR01026);

Maron Farndale (FAR01028);

Margaret E Farndale (FAR01039);

George W Farndale (FAR01040);

and George William Farndale (FAR01209).

The South Shields 2 Line are a

large family who descended from John Willie Farndale (FAR00591)

who settled from Barrow in Furness in the South Shields area (especially

Jarrow) by about 1905. The South

Shields 1 Line was a small family who settled in South Shields in about

1933.

Farndale Master Mariners operating out of Whitby regularly traded coal out of Newcastle in the nineteenth

century.

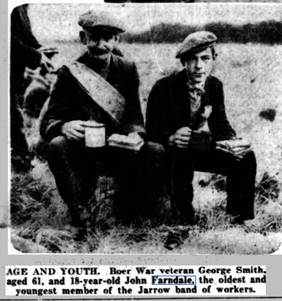

Between 5 and

31 October 1936, John William Farndale was the youngest

member of the 185 men who set off on the Jarrow marches. See his webpage for

more about the Jarrow marches and John’s involvement.

Newcastle

Newcastle upon Tyne, commonly

known as Newcastle, is a city in Tyne and Wear, North

East England, 103 miles south of Edinburgh and 277 miles (north

of London on the northern bank of the River Tyne,

8.5 miles from the North Sea. Newcastle

is the most populous city in the North East, and forms the core of

the Tyneside conurbation, the eighth most populous urban area in

the United Kingdom.

Newcastle was part of the

county of Northumberland until 1400, when it became a county of

itself, a status it retained until becoming part of Tyne and Wear in

1974. The regional nickname and dialect for

people from Newcastle and the surrounding area is Geordie.

Newcastle also houses Newcastle University, a member of the Russell Group,

as well as Northumbria University.

Roman

The city developed around

the Roman settlement Pons Aelius.

1080

Newcastle was named after

the castle built in 1080 by Robert Curthose, William the

Conqueror's eldest son.

Fourteenth century

The city grew as an

important centre for the wool trade in the 14th century, and later

became a major coal mining area.

Sixteenth century

The port developed in the

16th century and, along with the shipyards lower down the River Tyne, was amongst the world's

largest shipbuilding and ship-repairing centre

1530

From 1530, a Royal Act

restricted all shipments of coal from Tyneside to Newcastle

Quayside, giving a monopoly in the coal trade to a cartel of Newcastle

burgesses known as the Hostmen. This

monopoly, which lasted for a considerable time, helped Newcastle prosper and

develop into a major town.

1538

The phrase taking

coals to Newcastle was first recorded contextually in 1538. The

phrase itself means a pointless pursuit.

In the 18th century, the

American entrepreneur Timothy

Dexter, regarded as an eccentric, defied this idiom. He was

persuaded to sail a shipment of coal to Newcastle by merchants plotting to ruin

him; however, his shipment arrived on the Tyne during a strike that had

crippled local production, allowing him to turn a considerable profit.

In the Sandgate area, to

the east of the city, and beside the river, resided the close-knit community

of keelmen and their families. They

were so called because they worked on the keels, boats that were used to

transfer coal from the river banks to the waiting colliers, for export to London and elsewhere.

1636

In the 1630s, about 7,000

out of 20,000 inhabitants of Newcastle died of plague, more than one-third

of the population. Specifically within the year

1636, it is roughly estimated with evidence held by the Society of

Antiquaries that 47% of the then population of Newcastle died from the

epidemic. This may also have been the most devastating loss in any British city

in this period.

1644

During the English

Civil War, the North declared for the King. In a bid to gain Newcastle and

the Tyne, Cromwell's allies, the Scots, captured the town of Newburn.

In 1644, the Scots then captured the reinforced fortification on the Lawe

in South Shields following a siege and the city was besieged for

many months. It was eventually stormed "with roaring drummes" and sacked by Cromwell's allies. The

grateful King bestowed the motto "Fortiter Defendit

Triumphans" ("Triumphing by a

brave defence") upon the town. Charles I was imprisoned in Newcastle by

the Scots in 1646–7.

Eighteenth century

In the 18th century,

Newcastle was the country's fourth largest print centre after

London, Oxford and Cambridge, and the Literary and Philosophical Society of

1793 with its erudite debates and large stock of books in several

languages, predated the London Library by half a century.

Newcastle also became a

glass producer with a reputation for brilliant flint glass.

1806

A permanent military presence was

established in the city with the completion of Fenham

Barracks in 1806.

1817

In 1817 the Maling

company, at one time the largest pottery company in the world, moved to the

city.

1842

The Victorian industrial

revolution brought industrial structures that included

the 2 1⁄2-mile (4 km) Victoria Tunnel, built in 1842,

which provided underground wagon ways to the staithes.

1832

An engraving

by William Miller of Newcastle in 1832

1854

The Great fire of

Newcastle and Gateshead was a tragic and spectacular series of events

starting on Friday 6 October 1854, in which a substantial amount of property in

the two North East of England towns was destroyed in a series of fires and an

explosion which killed 53 and injured hundreds.

1879

On 3 February 1879, Mosley

Street in the city, was the first public road in the world to be lit up by

the incandescent lightbulb. Newcastle was one of the first cities in

the world to be lit up by electric lighting. Innovations in Newcastle and

surrounding areas included the development of safety

lamps, Stephenson's Rocket, Lord Armstrong's

artillery, Be-Ro flour, Joseph Swan's electric

light bulbs, and Charles Parsons' invention of the steam

turbine, which led to the revolution of marine propulsion and the production

of cheap electricity.

1882

The status of city was

granted to Newcastle on 3 June 1882.

In the nineteenth

century, shipbuilding and heavy engineering were central to

the city's prosperity and the city was a powerhouse of the Industrial Revolution. This

revolution resulted in the urbanisation of the city.

In 1882, Newcastle became

the seat of an Anglican diocese, with St. Nicholas'

Church becoming its cathedral.

1886

Based at St James' Park since

1886, Newcastle United F.C. became Football League members

in 1893. They have won four top division titles (the first in 1905 and the

most recent in 1927), six FA Cups (the first in 1910 and the most

recent in 1955) and the Inter-Cities Fairs Cup in 1969. They

broke the world transfer record in 1996 by paying £15 million

for Blackburn Rovers and England striker Alan Shearer,

one of the most prolific goalscorers of that era.

1901

Newcastle's public

transport system was modernised in 1901 when Newcastle Corporation

Tramways electric trams were introduced to the city's streets, though

these were replaced gradually by trolley buses from 1935, with the tram service

finally coming to an end in 1950.

With the advent of the

motor car, Newcastle's road network was improved in the early part of the 20th

century, beginning with the opening of the Redheugh

road bridge in 1901 and the Tyne Bridge in 1928.

1904

The city acquired its

first art gallery, the Laing Art Gallery in 1904, so named after its

founder Alexander Laing, a Scottish wine and spirit merchant who wanted to

give something back to the city in which he had made his fortune. Another art

gallery, the Hatton Gallery (now part of Newcastle University),

opened in 1925.

1917

Newcastle city centre, 1917

1920

Council housing began

to replace inner city slums in the 1920s, and the process continued into the

1970s, along with substantial private house building and acquisitions.

1930s

Unemployment hit record

heights in Newcastle during the Great Depression of the 1930s.

1934

Efforts to preserve the

city's historic past were evident as long ago as 1934, when the Museum of

Science and Industry opened, as did the John G Joicey

Museum in the same year.

1939

During the Second World War the city and

surrounding area were a target for air raids as heavy

industry was involved in the production of ships and armaments. The raids

caused 141 deaths and 587 injuries. A former French consul in Newcastle called

Jacques Serre assisted the German war effort by describing important targets in

the region to Admiral Raeder who was the head of the German Navy.

1956

The city's last coal pit

closed in 1956, though a temporary open cast mine was opened in 2013. The

temporary open cast mine shifted 40,000 tonnes of coal, using modern techniques

to reduce noise, on a part of the City undergoing

redevelopment. The slow demise of the shipyards on the banks of the River Tyne happened in the 1970s, 1980s, and 1990s.

View northwards from the Castle Keep,

towards Berwick-on-Tweed in 1954

1960s

The public sector in Newcastle began to

expand in the 1960s. The federal structure of the University of

Durham was dissolved. That university's colleges in Newcastle, which had

been known as King's College, became the University of Newcastle upon Tyne (now

known as Newcastle University), which was founded in 1963, followed

by a Newcastle Polytechnic in 1969; the latter received university status in

1992 and became the Northumbria University.

1983

Further efforts to preserve the city's

historic past continued in the later twentieth century, with the opening of

Newcastle Military Vehicle Museum in 1983 and Stephenson Railway

Museum in 1986. The Military Vehicle museum

closed in 2006. New developments at the turn of the 21st century included

the Life Science Centre in 2000 and Millennium Bridge in

2001.

South Shields

South Shields is a coastal town in

the North East of England at the mouth of the River Tyne,

about 3.7 miles downstream from Newcastle upon

Tyne. Historically part of County Durham, it became part

of Tyne and Wear in 1974. According to the 2011 census, the town had

a population of 76,498, the third largest in Tyneside after Newcastle

and Gateshead. It is part of the metropolitan

borough of South Tyneside which includes the towns

of Jarrow and Hebburn. The demonym of a person

from South Shields is either a Geordie or

a Sand dancer.

Pre

historic

The first evidence of a settlement

within what is now the town of South Shields dates from pre-historic

times. Stone Age arrow heads and an Iron Age round house

have been discovered on the site of Arbeia Roman

Fort.

160 CE

The Roman garrison built a fort here

around 160 CE and expanded it around 208 CE to help supply their soldiers

along Hadrian's Wall as they campaigned north beyond the Antonine Wall. Divisions

living at the fort included Tigris bargemen from Persia and modern

day Iraq, infantry from Iberia and Gaul, and Syrian archers and

spearmen.

Fourth century CE

The fort was abandoned as the Roman

Empire declined in the 4th century CE. Many ruins still exist today and some structures have been rebuilt as part of a

modern museum and popular tourist attraction.

Post Roman

There is evidence that the site was used

in the early post-Roman period as a British settlement. It is believed it

became a royal residence of King Osric of Deira; records show that his son

Oswin was born within 'Caer Urfa', by which name the fort is thought to be

known after the Romans left.

647 CE

Bede records Oswin giving a parcel

of land to St Hilda for the foundation of a monastery here in c.647;

the present-day church of St Hilda, by the

Market Place, is said to stand on the monastic site.

Ninth century CE

In the 9th

century, Scandinavian peoples made Viking raids on

monasteries and settlements all along the coast, and later conquered the

Anglian Kingdoms of Northumbria, Mercia and East

Anglia. It is said in local folklore that a Viking ship was wrecked at Herd

Sands in South Shields in its attempts to disembark at a cove nearby. Other

Viking ships were uncovered in South Shields Denmark Centre and nearby Jarrow.

1245

The current town was founded in 1245 and

developed as a fishing port. The name South Shields developed from the Schele

or 'Shield', which was a small dwelling used by fishermen.

Another industry that was introduced,

was that of salt-panning, later expanded upon in the fifteenth century,

polluting the air and surrounding land.

1642

In 1864, a Tyne Commissioners dredger

brought up a nine-pounder breech-loading cannon; more cannonballs have been

found in the sands beside the Lawe; these artifacts belonged to the English

civil war. At the outbreak of the war in 1642, the North, West and Ireland supported

the King; the South East and Presbyterian Scotland supported

Parliament. In 1644 Parliament's Scottish Covenanter allies, in

a lengthy battle, seized the town and its Royalist fortification, the

fortification was close to the site of the original Roman fort. They also

seized the town of Newburn. These raids were done to aid their

ongoing siege of the heavily fortified Newcastle upon Tyne, and in a bid to

control the River Tyne, and the North, and the Shields

siege helped cause their battalions to manoeuvre south to York; this may

have also led to a brief winter skirmish on the outskirts of Boldon,

though the topography is not favourable for a battle.

Nineteenth century

In the 19th century, coal mining,

alkaline production and glass making led to a boom in the town.

1801

The population was 12,000 in 1801

1832

With the Great Reform Act, South Shields

and Gateshead were each given their own Member of Parliament and

became boroughs, resulting in taxes being paid to the Government instead of the

Bishops of Durham.

The rapid growth in population brought

on by the expansion of industry made sanitation a problem, as evident by

Cholera outbreaks and the building of the now-listed Cleadon

Water Tower to combat the problem.

1850s

'The Tyne Improvement Commission' began

to develop the river, dredging it to make it deeper and building the large,

impressive North and South Piers to help prevent silt build up within the

channel. Shipbuilding (along with coal mining), previously a monopoly of the

Freemen of Newcastle, became another prominent industry in the town,

with John Readhead & Sons Shipyard the largest.

1861

The population had increased to 75,000,

bolstered by economic migration from Ireland, Scotland and

other parts of England.

1916

During World War I,

German Zeppelin airships bombed South Shields in 1916.

1939

During World War II,

the German Luftwaffe repeatedly attacked the town and caused massive damage to

industries which supported the war effort, killing many innocent residents.

Particularly, a bomb shelter in the market place of

South Shields, where the deceased were commemorated in a cobblestone of the

British flag.

Twentieth century

Gradually throughout the

late 20th century, the coal and shipbuilding industries were closed during the

Thatcher political era, due to competitive pressures from more cost effective sources of energy and competitive

shipbuilding in Eastern Europe and in South East Asia.

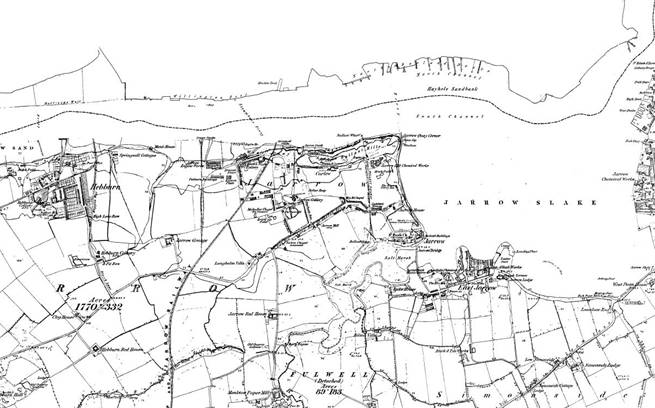

Jarrow

Jarrow is a town in South

Tyneside in the county of Tyne and Wear, England. It is on the south bank of

the River Tyne, about 3 miles from the east coast.

731 CE

In the eighth century, the

monastery of Saint Paul of Tarsus in Jarrow (now Monkwearmouth, Jarrow Abbey)

was the home of The Venerable Bede, who is regarded as the greatest Anglo-Saxon

scholar and the father of English history. Bede’s whose most notable works

include Ecclesiastical History of the English People and the translation

of the Gospel of John into Old English. Along with the abbey at Wearmouth,

Jarrow became a centre of learning and had the largest library north of the

Alps, primarily due to the widespread travels of Benedict Biscop,

its founder.

750 CE

The town's name is

recorded around 750 CE as Gyruum, from Old

English Gyrwum " the marsh

dwellers", and from gyr meaning "mud"

or "marsh". Later spellings are Jaruum

in 1158, and Jarwe in 1228. In the

Northumbrian dialect it is known as Jarra.

794 CE

In 794 Jarrow became the

second target in England of the Vikings, who had plundered Lindisfarne in 793.

Nineteenth century

From the middle of the

19th century until 1935, Jarrow was a centre for shipbuilding.

Jarrow remained a small

mid-Tyne town until the introduction of heavy industries such as coal mining

and shipbuilding.

1852

Charles Mark Palmer

established a shipyard, Palmer's Shipbuilding and Iron

Company, in 1852 and became the first armour-plate manufacturer in the world.

John Bowes, the first iron

screw collier, revived the Tyne coal trade, and Palmer's was also responsible

for the first modern cargo ship, as well as a number of

notable warships.

Around 1,000 ships were

built at the yard, they also produced small fishing boats to catch eel within

the River Tyne, a delicacy at the time.

1857

1904

Jarrow Town Hall was

erected in Grange Road and officially opened in 1904.

1915

The Jarrow rail disaster

was a train collision that occurred on the 17 December 1915 at the Bede

junction on a North Eastern Railway line. The

collision was caused by a signalman's error and seventeen people died in the

collision.

1918

1920s

Although the First World War caused an economic boom in Britain,

it masked a slow industrial decline from the country's Victorian heyday. As

wartime demands gradually fell away, these failings again came to the fore and

during 1920 Britain was plunged into an economic slump accompanied by high

levels of unemployment and poverty.

1929

The situation was made far worse by the world-wide recession of

1929 and, having remained relatively

constant, though high, at 10% throughout the 1920's, unemployment peaked at 22%

in 1932.

Britain's traditional industries were particularly hard hit

meaning that the North of England, Wales and

Scotland, which had economies heavily dependent upon manufacturing, were

disproportionately affected by the slump. This meant that these regions actually suffered far higher levels of unemployment

than those suggested by the national average. And the effects were

long-lasting, rather than following a regular economic cycle of prosperity and

recession.

During the 1920's, the National Unemployed Workers' Movement (“NUWM”)

organised a serious of 'hunger marches' to London in the hope that these would

force the Government to radically rethink its economic policies. The term

'hunger march' was a recent one, first coined to describe a march by London's

poor in 1908. The marches achieved nothing, however, the official view being

that they were being high-jacked to serve

the aims of their 'Communist' organisers.

1932

The end of the world-wide recession in 1932 allowed Britain to

begin a slow path to recovery.

1936

By 1936, economic growth had reached 4% and mini-booms were being seen in housing and consumer

spending. The recovery was badly uneven, however, with those areas which had

seen their traditional employers devastated during the slump slow to see any

improvement.

The town of Jarrow, lying on the southern bank of the River Tyne, had undergone a massive period of expansion

during the Victorian era. However its

economy was based on precisely those industries - iron, steel, shipbuilding -

which were so badly hit by the recent depression. Charles Mark Palmer, the

so-called 'King of Jarrow', had created an industrial empire in the town but

gradually each of these businesses failed in turn. Unemployment stood at 3,300

in 1930 (75% of the working population) and at 6,793 in 1932 (80% of the

insured population). When Palmer's Shipyard failed in 1934, the town lost its

last purpose for existing. As the town's newly elected MP, the firebrand 'Red

Ellen' Wilkinson, so forcefully pointed out in the Commons in December,1935:

"The years go on and nothing is done ... this is a desperately urgent

matter and something should be done to get work to these areas which, heaven

knows, want work."

The hunger-march had become an accepted form of protest and

in July 1936 the town's political leaders set in progress plans to

mount a march from Jarrow to deliver a petition to Parliament calling for the

opportunity to work.

Over 1,200 men came forward to take part, but it was decided to

limit numbers to the 200 fittest and hardiest to make the logistics manageable.

A fund was started to pay for supplies and equipment and

this would continue to collect donations as the men marched south. Rallies were

scheduled for the march's overnight stops to spread the word of what it was

trying to achieve. As one marcher put it: "We were more or less

missionaries of the distressed areas, [not just] Jarrow."

On Monday, 5 October, the date set for the start of the March, the

Marchers received the blessing of the Bishop of Jarrow at a dedication service

in Christ Church. This gained the venture a boost in credibility, but the

service was condemned by Hensley Henson, the Bishop of Durham, who was

unflinchingly opposed to the Trades Union movement and Socialism. Henson

condemned the hunger marches as a whole as nothing

but a vehicle for the Labour Party and his colleague in Jarrow, James Gordon,

was later obliged to state that the service was not intended to condone the

March. To add injury to insult, the Marchers later discovered that their dole

had been stopped as the March had made them unavailable for work!

Immediately after the service, the Marchers assembled at Jarrow

Town Hall and made their last preparations before setting off. Although 200 men

had been accepted for the venture, only 185 made it to the start-line due to

sickness, changes in personal circumstance, etc. Around half of those taking

part were veterans of the First World War and the Marchers walked in step and

in military ranks to show their discipline and proclaim their past service.

They took a 10-minute break every hour, in the military manner, and a harmonica

band encouraged the singing of popular songs of the day to keep their spirits

up. Before them they carried a blue-and-white banner proclaiming the ‘Jarrow

Crusade’ though in Jarrow it was never known as anything other than ‘The March’. Again in the military tradition, behind them followed a

bus with a field kitchen, a medical facility, and camping equipment for when

beds were not available.

It would be a mistake to think that the Jarrow March took place in

isolation. The sixth National Hunger March was setting off from 6 regional

centres and these were due to unite in London a week after the arrival of the

Jarrow men. Meanwhile, a group of blind veterans were marching in protest at

the treatment of the nation’s 67,000 registered blind persons. The National

Marches were seen as hostile and confrontational, and this undoubtedly aided

the high level of publicity given to the Jarrow March which, by contrast, was

recognised for its moderation and quiet dignity.

Ellen Wilkinson temporarily left the march at its first stopping

point, in Chester-le-Street, to attend the

Labour Party's annual conference in Edinburgh. Although it was proclaimed to be

non-political, the Jarrow March was very much a product of the town’s

Labour Council and she may have hoped to

gain some support from her colleagues. In this she was to be disappointed,

however. The Parliamentary Labour Party (“PLP”) was a minority part of the

National Government of the time and anxious to distance itself from any

accusations of ‘Communism’. So, neither this nor the Trade Union Congress (“TUC”)

would offer its endorsement. David Riley, the Chairman of Jarrow Borough Council and a leading light in the organisation of the

March, later complained that they felt that they had been "stabbed in the

back".

As they moved south, the reception extended to the Marchers varied

from indifferent to warm and welcoming. Local accommodation was secured in a

series of Schools, Church Halls or other

spacious buildings, and often gifts were made of food and clean clothing. What

soon became clear was that the reception received bore no link to the political

affiliation of the local Councils and the organisers of the March were at pains

to avoid any action that might alienate any political body. Often the weather

was bad, cold with driving rain.

Very quickly the March began attracting wide publicity and the

Government in London, afraid that it was gaining Royal attention, acted to

limit sympathy for it, claiming that such Marches only resulted in “unnecessary

hardship for those taking part in them”. Wilkinson continued to push for an

official reception for the Marchers, but received

no encouragement from Prime Minister Stanley Baldwin during heated exchanges in

the Commons. In truth Baldwin was in an impossible position, for opening

Parliament’s doors to the Jarrow Marchers would have set a dangerous precedent.

The March reached Edgware in northern London on Friday, 30

October, leaving a relatively short 8-mile walk to Marble Arch the following

day. It had been denied permission to deliver its petition to Parliament and so

Ellen Wilkinson had to make the last stage of the journey alone. The original

petition, calling for Government aid for the Town, had 11,000 signatures and

was carried in an oak box. An additional petition had been made available to

those who had wanted to sign on the way.

A new session in the House of Commons was convened on 3 November –

the March had been timetabled to take advantage of this – and next day the

Petition was presented. A (very) brief discussion followed

after which the House returned to its normal business.

The March garnered a lot of publicity, a lot of soft words, but

achieved little real change. This was not lost on the marchers themselves and

the return journey home by train was a sombre affair.

1939

Not until the outbreak of the Second World War in 1939 did the

Town start to recover from its long period of depression. When ‘Red Ellen’

published her history of Jarrow that same year she titled it: "The Town

that was Murdered”.

Links, Texts and Books

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|