Act 32

Soldiers, Sailors and Airmen

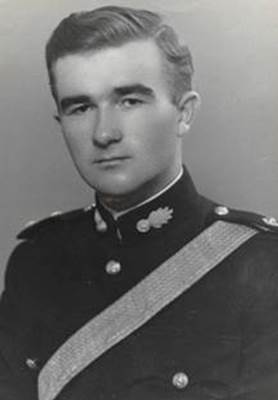

Field Marshall the Viscount

Montgomery (“Monty”) inspects the Troop of Lieutenant Farndale in 1950

The Farndales who took up arms from

the army of Henry V to the Gulf War

|

The Military Farndales Podcast This

is a new experiment. Using Google’s Notebook LM, listen to an AI powered

podcast summarising this page. This should only be treated as an

introduction, and the AI generation sometimes gets the nuance a bit wrong.

However it does provide an introduction to the themes of this page, which are

dealt with in more depth below. Listen to the podcast for an overview, but it

doesn’t replace the text below, which provides the accurate historical

record. |

|

The Battle of Arras, Spring 1917

Personal

accounts of the offensive. |

Scene 1 - Medieval Soldiers

You might

recall, in another age, in Act 10

of our Story, that we met John de Farendale who served under Harry Hotspur and others

with an expeditionary force into Scotland in 1384, and that he was later joined

by his probable brothers Henry Farendon and William Faryndon, in another flurry north in 1389.

Then we met Richard Farendale of Sherifhoton who

served in the Hundred Years War in Brittany in 1380 and was part of another

expeditionary force to Scotland in 1400. He served in the army of Henry V,

perhaps in the Agincourt campaign and certainly afterwards, at Harfleur and the

Siege of Mantes. When he died he left an impressive catalogue of military

equipment including a horse, saddle and reins, and armour, comprising a bascinet,

medieval combat helmet, a breast plate, a pair of vembraces,

armoured forearm guards and a pair of rerebraces,

armour designed to protect the upper arms, with leg harnesses.

His three

daughters witnessed the Wars of the Roses from the heart of the Neville

homeland.

|

Tales of archers and men at arms who fought with

Richard II, Henry IV and Henry V and an observation post in the home of the

Nevilles and Richard III from which to view the Wars of the Roses |

|

The History of Sheriff Hutton to 1500

A

history of Sheriff Hutton which will take you to the lands of the Nevilles

and Richard III during the Wars of the Roses |

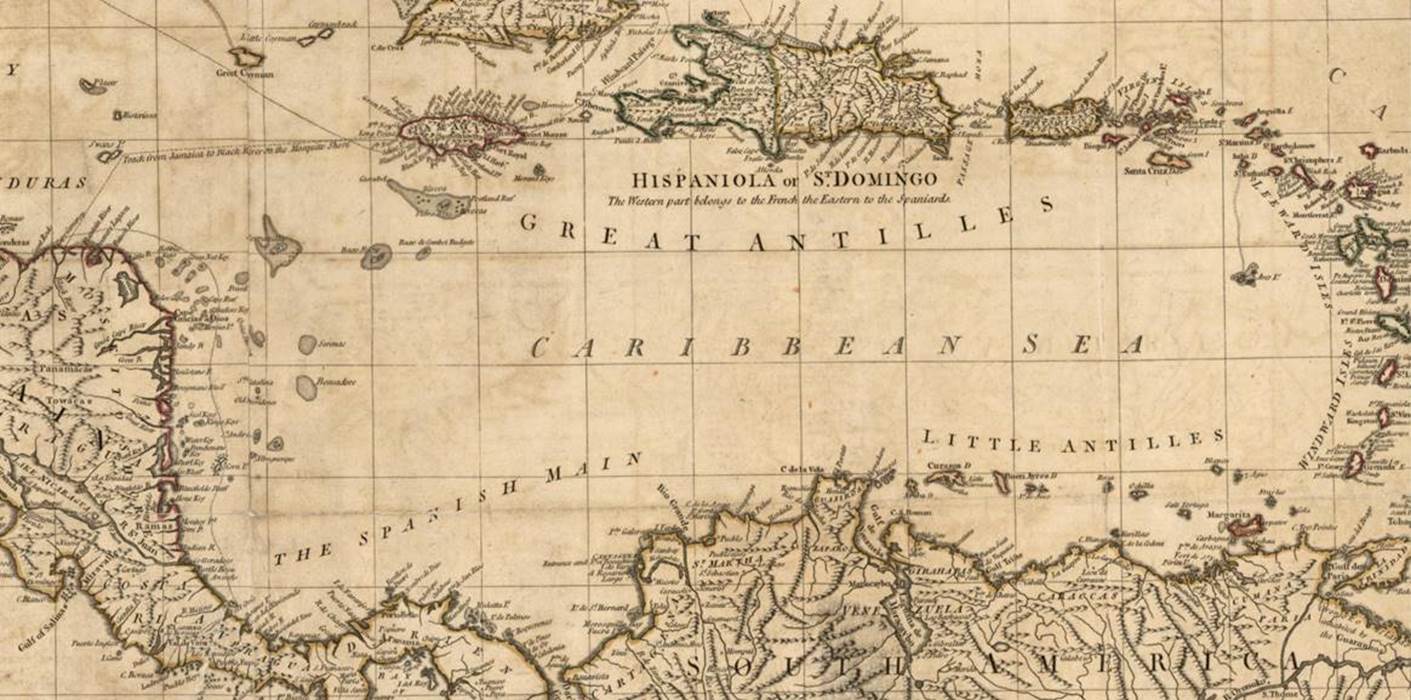

Scene 2 - The War of Jenkins Ear and

death on the Spanish Main

We have also

met Able Seaman Giles

Farndale, who served with the Royal Navy from 29 June 1740 until he died at

sea in the Caribbean on 9 May 1741. He was press-ganged at Whitby, when he would have been 27 years old.

He was posted to the HMS Experiment, a brig with a compliment of 130, as

No 101 Able Seaman.

He almost

certainly took part in the War of Jenkins’ Ear in the Spanish Main under

Admiral Vernon and was probably involved in the

Battle of Cartagena de Indias in March 1741. No circumstances are recorded

of the reason for his death, but he probably died in the aftermath of the

disaster at Cartagena, when soldiers and sailors were crammed on ships, rife

with disease.

|

1713 to 1742

Press ganged into

the Royal Navy, Giles served on HMS Experiment in the Spanish Main

during the War of Jenkins Ear where he died and was buried at sea |

Scene 3 - The Crimean War

Private

John George Farndale saw service between 1853 and 1856 possibly first with

the Coldstream Guards and then with the 28th of Foot.

He served in

the Crimean War in 1854 and 1855. From the Heights of Sevastopol, he wrote We

then started for Sebastopol, and reached it after eight or nine days’ march; we

had to go a great way round. As soon as we got in front and settled, we

commenced throwing up batteries and breast works, under fire of the enemy. We

finished them after about five days and nights’ hard working, and opened fire

on them on the 17th of last month, and have been battering away ever since, and

are likely to continue doing so for some time to come. We have greater

opposition than we expected. There was a faint attack made on our rear army a

few days ago, which cut up our cavalry fearfully, but were defeated in the end.

Our loss is not so great, considering all the circumstances of the case. I have

escaped as yet, thank God! I have had a narrow escape: one morning, as we were

relieving guard, two privates and a sergeant were shot close by me with one

ball. I have been laid up in my tent with frost bitten feet nearly all this month,

but I am better again and fit for duty. The siege is progressing very slowly

but I think we will soon open a new siege. Things begin to look a little

better. We have received the winter clothing and are getting provisions a

little better. We want the wooden houses next, although I think as we have done

so long without, we could manage without them altogether. However I hope that

before you get this, Sebastopol will be ours and then we will be thinking about

returning to old England again. If I live to see it over and get back to old

England again, which by the blessing of God I hope to do, I will tell you tales

that will make your hair stand on end!

|

Read

the full story of John Farndale’s experiences and his reports home from the

Crimean War |

The

Grenadier Guards

John Farndale

was discharged from the Grenadier Guards on 25 July 1872. He received £10

compensation. He had served for 3 years and 323 days. This was most likely to

have been John

Farndale of Clerkenwell London.

The

Grenadier Guards spent most of the late nineteenth century on garrison and

ceremonial duties in London, Windsor and Dublin. The years following the Crimean War saw changes to the

uniforms and equipment and fundamental reform brought about mainly by two

Secretaries of State for War, Sidney Herbert and Edward Cardwell. Flogging was

phased out until it was abolished in 1881 and illiteracy was reduced by better

education. The practice of enlistment for life was also phased out and the

purchase of commissions ended in 1871. Military training was changed

drastically and the guards were housed near training areas outside London, at

Warley until 1877, then Caterham until 1959, and Pirbright from 1882.

This was the

time of the

Franco-Prussian War and the British Expedition to

Abyssinia, a rescue mission and punitive expedition carried out in 1868

against the Ethiopian Empire. Emperor Tewodros II of Ethiopia, often referred

to as Theodore, imprisoned several missionaries and two representatives of the

British government in an attempt to force the British government to comply with

his requests for military assistance. The punitive expedition launched by the

British in response required the transportation of a sizeable military force

hundreds of kilometres across mountainous terrain lacking any road system. The

formidable obstacles to the action were overcome by the commander of the

expedition, General Robert Napier, who captured the Ethiopian capital, and

rescued all the hostages. Historian Harold G. Marcus described the action as one

of the most expensive affairs of honour in history.

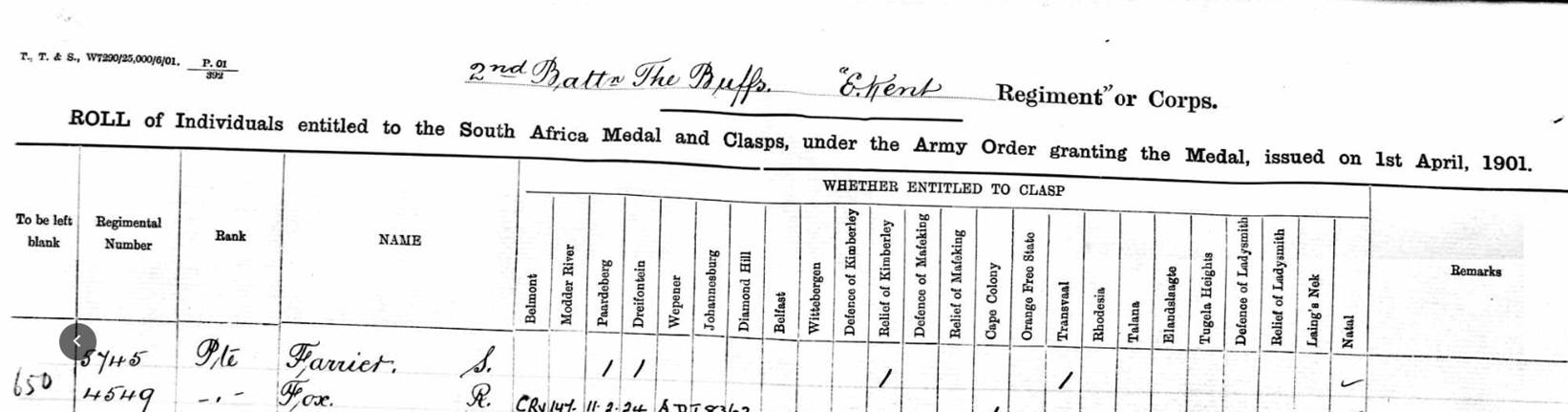

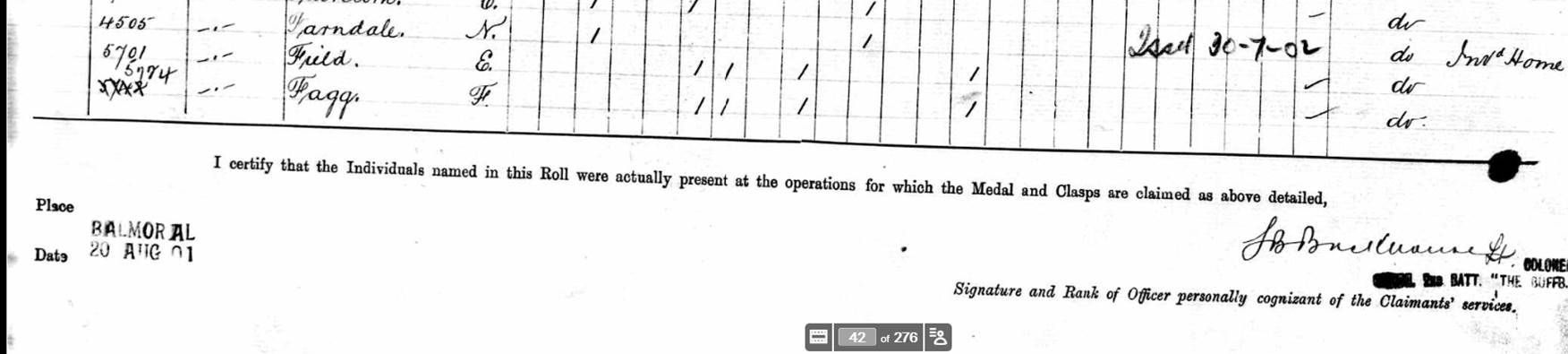

Scene 4 - The Second Boer War

4505 Private N Farndale, served during the Second Boer War,

with Second Battalion The East Kent Regiment, the Buffs. He was in

action at Paardeberg and during the Relief of

Kimberley. The war lasted from 1899 to 1902 and N Farndale was listed on a Roll

at Balmoral on 20 August 1901, as having taken part in the campaign, so he had

returned from South Africa by then.

He was still

in Sussex on 22 August 1899 when, at a cricket match, the local team’s

opponents on Thursday were the Buffs, who, batting first, knocked up 151. The

Buffs, Private Farndale, caught Allen, bowled G A Hammond, 6 runs.

The Second

Battalion saw action during the Second Boer War with Captain Naunton Henry

Vertue of the Second Battalion serving as brigade major to the 11th Infantry

Brigade at the Battle of Spion Kop where he was

mortally wounded in January 1900.

The phrase Steady

the Buffs! was popularised by Rudyard Kipling in his 1888 novel Soldiers

Three. The origin of the phrase

came from Adjutant John Cotter during garrison duties in Malta, who encouraged

the men of the 2nd Battalion with Steady the Buffs! The Fusiliers are

watching you as he did not want to be shown up in front of his former

Regiment, the 21st Royal Fusiliers.

The Battle

of Paardeberg or Horse Mountain, was fought

between 18 and 27 February 1900, during the Second Anglo-Boer War. It was

fought near Paardeberg Drift on the banks of the

Modder River in the Orange Free State near Kimberley. It was part of the

Relief of Kimberley. Lieutenant General Herbert Kitchener, had taken

overall command of the British force. Kitchener ordered his infantry and mounted troops into a

series of uncoordinated frontal assaults against the Boer laager, although

frontal assaults against entrenched Boers had cost the British time and again

in the preceding months. The British were shot down in droves. It is thought

that not a single British soldier got within 180 metres of the Boer lines. By

nightfall on 18 February 1900, some 24 officers and 279 men had been killed and

59 officers and 847 men wounded. It was the worse reverse of the war and became

known as Bloody Sunday.

Canadian

Troops at Paardeberg

Following

the end of the war in South Africa in June 1902, 540 officers and men of the

Second Battalion returned to Britain on the SS St. Andrew leaving Cape

Town in early October, and the Battalion was subsequently stationed at Dover.

Sergeant

William Leng Farndale was a Sergeant in the Northumberland Imperial

Yeomanry (Hussars) in 1902. They had served in the Second Boer War, and it is

likely that he also took part in that campaign.

The

Hussars parade through Rothbury, William’s home town in Northumberland, in 1900

The Yeomanry

was not intended to serve overseas, but due to the string of defeats during

Black Week in December 1899, the British government realised they were going to

need more troops than just the regular army. A Royal Warrant was issued on 24

December 1899 to allow volunteer forces to serve in the Second Boer War. The

Royal Warrant asked standing Yeomanry regiments to provide service companies of

about 115 men each for the Imperial Yeomanry equipped as Mounted infantry. The

regiment provided 14th (Northumberland) Company, 5th Battalion in 1900; 15th

(Northumberland) Company, 5th Battalion in 1900; 55th (Northumberland) Company,

14th Battalion in 1900, transferred to 5th Battalion in 1902; 100th

(Northumberland) Company, 5th Battalion in 1901; 101st (Northumberland)

Company, 5th Battalion in 1901; 105th (Northumberland) Company, 5th Battalion

in 1901 and 110th (Northumberland) Company, 2nd Battalion in 1901.

The mounted

infantry experiment was considered a success and the Regiment was designated

the Northumberland Imperial Yeomanry (Hussars) from 1901 to 1908.

William Leng

Farndale continued to serve with the Yeomanry until about 1907, regularly

organising social balls. He later became Rothbury’s brewer.

There was an

F A Farndale-Williams who was a second lieutenant with the Moulmein Volunteer

Rifles on 30 March 1907 who appeared under Indian Army Orders.

Scene 5 - First World War

The members

of the family who happen to have been male, and born between about 1880 and

1900, were, in all probability, destined for the horrors of industrial war in

the second decade of the twentieth century. Forty members of our

family served in the First World War.

Private (later Lance Corporal) George Weighill Farndale served with 15th Battalion (1st

Leeds), The Prince of Wales’s Own (West Yorkshire Regiment), known as the Leeds

Pals. On the first day on the Somme, on 1 July 1916, the Leeds Pals were

shelled in their trenches before Zero Hour at 07.30 hours and when they

advanced, they were met by heavy machine gun fire. A few men got as far as the

German barbed wire but no further. The battalion casualties, sustained in the

few minutes after Zero Hour, were 24 officers and 504 other ranks, of which 15

officers and 233 other ranks were killed. Private A.V. Pearson, of the Leeds

Pals later wrote, the name of Serre and the date of 1st July is engraved

deep in our hearts, along with the faces of our 'Pals', a grand crowd of chaps.

We were two years in the making and ten minutes in the destroying. George

was wounded in July 1916, presumably in the Somme offensive. He seems to have

been relatively lucky but what horrors he witnessed can only be imagined. A

year later he was Killed in Action, aged 30, during the Third Battle of the

Scarpe, part of the Arras offensive, on 3 May 1917.

The Arras

Offensive

G333852 Private

George Farndale was sent to France on 8 April 1917. Waiting for embarkation

at Folkestone, he wrote I got a very decent breakfast here and had an extra

tea before we left Catterick. From France on 19 April 1917, he told his

sister, I wrote to the Girl on Sunday so I am expecting to hear from her

anytime. On 24 April 1917, he wrote I am just sending you a line to tell

you that I am in a draft and expecting to go out any day. If you haven’t wrote

and sent the things I asked for don’t trouble, as I may be gone before they arrive

and I sharn’t be able to take them with me. If I

should be here over the weekend I will write you again on Sunday if not I will

try and send you a line before I leave. I have got all my kit ready for going

but I don’t think I shall go before Saturday or Monday. Well

be sure and don’t worry about me and tell Father not to, as I shall be alright,

and I must say before I go that you and Father have been very kind to me as I

never wanted for anything and I must say you have done more than your duty

towards me. A month after writing to his sister, on 20 May 2017, George was

involved in an attack when we went over and took the German front line

trench, which we held for 2 days and then were relieved. He was with his

mate, Private R Sellers that day. George was killed in action a week later on

27 May 1917, aged 26, in the same Arras offensive that had killed his kinsman George Weighill Farndale twenty four days earlier.

George

Farndale

On 19 April

1917, the Girl, who, it turns out, was called Dolly, wrote to George’s

sister. I am deeply grieved on hearing from you yesterday morning that dear

George has been killed in action, and all at Shingle Hall including myself wish

to express our deepest sympathy with you all in this dark hour of sadness. It

was an awful blow to me dear, and is one that I shall never forget. He was such

a nice quiet and gentle boy and was very much liked by all who knew him in

Sawbridgeworth, and no fellow could not think so much of a girl as your dear

brother did of me, and had he been spared to come back safely we intended

getting married. I don’t know if he ever spoke about it to you.

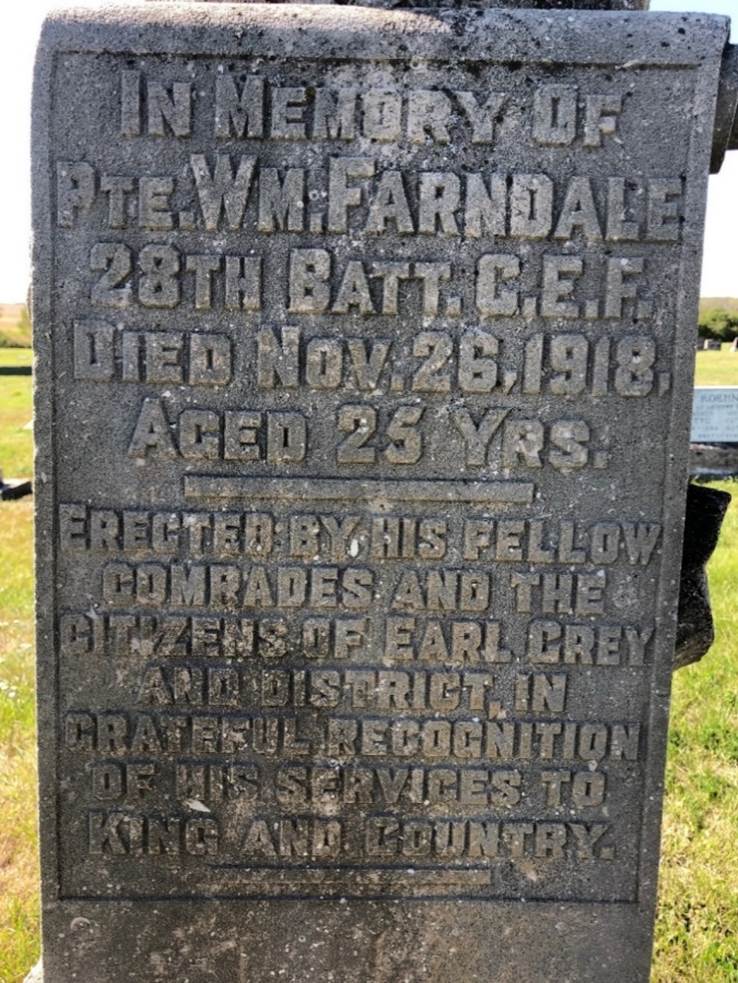

104060 Private

William Farndale was born in Tidkinhow,

but had emigrated to Saskatchewan, where he was a butcher. He is my great

uncle. He joined the Canadian Army on 19 April 1916. His younger brother Alfred,

my grandfather, who he had consoled at their mother’s funeral in 1911, had

already joined to British Army in late 1915, though strictly, he was a little

younger than he should have been. His older brother, Jim, who had moved

on from Canada to the United States, joined the US Army in 1917, shortly after

the USA joined to conflict. Three brothers, served in three different armies,

for a common cause.

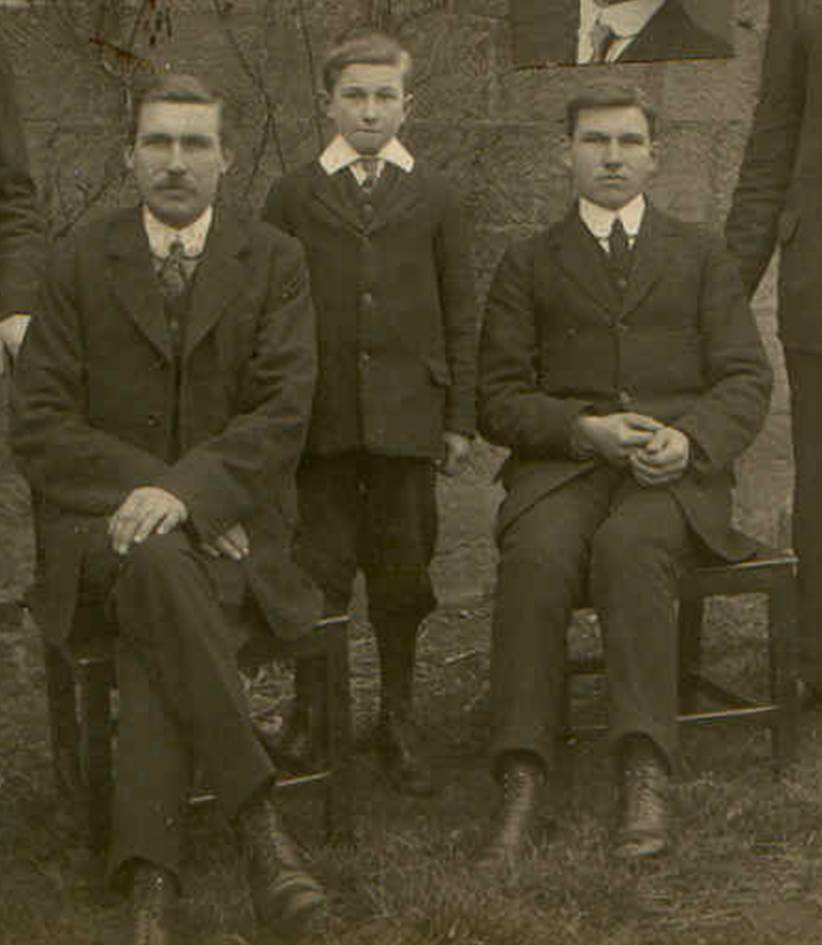

William

Farndale

James, Alfred, William at Tidkinhow

in 1911 (brothers in arms)

William was

wounded in action at Vimy Ridge on 13 December 1916 while serving with the 28th

Battalion. He took a gunshot wound in the right forearm. From December 1916 to

March 1917, the Canadian Corps executed fifty five trench raids. Competition

between units had developed with units competing for the honour of the greatest

number of prisoners captured. The policy of aggressive trench raiding was not

without its cost. A large-scale trench raid on 13 February 1917, involving 900

men from the 4th Canadian Division, resulted in 150 casualties.

He wrote

from hospital to his sister Grace

during the following month. Left hand of course. Jan 12. Dear Sister. I will

try and write to you. I find I am doing fairly well but I have got a very bad

arm. I was hit with an explosive bullet which made a hole through two inches

wide and broke both bones. They give me very little hope of my arm being any

good but I hope it will not be so bad. I had an awful hard time in France. I

had four operations in two weeks. They could not get it stopped bleeding and I

got so weak that I could not feed myself. But I am alright now, but not able to

get up yet for two weeks or so. I may have to have another operation. Not sure

yet. Going to have my arm x-rayed shortly. I want you to write a letter for me

to Sister Armstrong, 23 CCS, BEF, France. Give her my address and tell her I am

getting along alright. This is not a very nice hospital, but good doctors. If

you send a parcel, send me a toothbrush and hairbrush. I expect I will be here

three months. I tried to get into Yorkshire so you could come and see me, but

this is as far as I could get. If my arm does not get better it is likely I will

get sent back to Canada in the Spring, but I will never see France any more. I

am awful sorry that Alf

had to go. If ever he gets to France I will want to go back again.

He was

discharged from the Army at Calgary on 18 February 1918. After his return to

Regina, he used his car to take patients to hospital during the great influenza

epidemic of 1918. He caught the ‘flu while still weak from his wound and died

at Earl Grey, Saskatchewan, Canada, aged 25 years on 23 November 1918. He was

buried in Earl Grey, Saskatchewan. William had been engaged to a girl in Earl

Grey at the time of his death.

My

grandfather Alf

later recalled, the war came in 1914 and I was just 17. I wanted to join up

so I ran away and joined up at the local recruiting office at Northallerton, somewhere in South Parade

I think. I joined the West Yorks but my father found out and said I was under

age, which I was. The CO wanted me to stay on the band, but father wouldn’t

hear of it and I came out. I remember being very proud of my first leave in

uniform. Then one day they called for volunteers for the Machine-Gun Corps and

I stepped forward. We went to Belton Park, near Grantham for training. I joined

239th Company MGC and we were attached to the Middlesex Regiment.

Alf

Farndale

Machine Gun Corps at Belton

Park, Grantham in 1917

Ypres, France, 1917 (Alfred centre, rear)

I

remember an incident on the Menin Road galloping up with two limbers of

ammunition towards the gun positions at Hooge. I was a Private but I was giving

a lift to Quarter Master Sergeant Zaccarelli. The Germans started to shell us.

They could clearly see us. I had one horse killed and I managed to cut him free

and I then rode the other. Zaccarelli was killed; it was quite a party when I

reported it. My Captain asked if there were any witnesses but there were none,

otherwise I might have got something. I remember an officer coming up to me

when we were under bombardment at Ypres and saying “How would you like to be in

Saltburn now, Farndale?” We saw

some action at Zonnebeke, Ploegstraat

and Arras.

Then

suddenly we were ordered to Marseilles and got on a troopship for Basra in

Mesopotamia. He then

saw service

overseas in Iraq and India from 14 October 1917 to 9 January 1920. His later

service was recorded with 239 Company in Mesopotamia.

After about 14 days we were in the Suez Canal and then the Red Sea. We landed

at Basra and marched to Kut-el-Amara as part of a

force under General Maud to relieve Townsend. About the middle of 1918 the

Turks surrendered. We hung around for quite a while. I cut my thumb on a bully

beef tin and it got poisoned. I was in hospital in Kut when 239th

Company left for England. There is a

record of an accidental injury and in a separate statement, he wrote While

opening a tin of canned beef on 2 February 1919 at Baiju Station with Jack

Knife, the knife slipped and cut my right thumb. A Farndale.

His

grandson, Nigel Farndale, later wrote For my grandfather, Private Alfred

Farndale, who died in the mud of Passchendaele, and again seventy years later

in his bed, every man died in that battle, even those who survived. For the

dark, life-sapping shadow that descended on them all snuffed out a vital

spark.

Herbert Farndale

was born on 30 March 1892, into the Craggs

Hall Farm family. On 1 July 1916, he was a Private soldier with the 10th

Battalion East Yorkshire Regiment in support of the 31st Division’s

assault on the

first day of the Battle of the Somme. He was awarded a military medal for

bravery that day, but the citation has not survived. Herbert was later

commissioned.

Herbert

Farndale

G/445 Lance

Corporal George James Farndale (later Sergeant) served with the Second

Battalion, The

Royal Sussex Regiment and went to France on 31 May 1915. The Battalion took

part in the Second Battle of Arras in August 1918. He was awarded the Military

Medal for bravery on 23 October 1918.

3758 and

201065 Private Richard Farndale joined the colours in May 1915, at the age

of eighteen and enlisted into the 1/4th Battalion, the Princess of Wales’ Own Yorkshire Regiment, also known as the Green

Howards. The Battalion served with the 150th Infantry brigade. On 11 January

1917 the Battalion moved to the front line at Hexham Road. It was on the front

line from 30 January to 11 February 1916 at Genercourt.

The battalion moved to Proyart on 19 February 1917.

Richard died at 21st Casualty Clearing Station of broncho-pneumonia on 25

February 1917. He was presumably badly wounded at Hexham Road, Genercourt or Proyart and

evacuated to the Casualty Clearing Station at La Neuville, where he later died

of pneumonia. Richard is buried at La Neuville Communal Cemetery, Corbie, Somme

and commemorated on the war memorial at Coatham.

131820 Lance

Corporal William Farndale of Great

Ayton joined the Royal Engineers. He was promoted to Corporal in March 1917

and was wounded in a gas attack in April 1917 when he was transferred to

England to 2 General Hospital. 204344 Regimental

Quarter Master Sergeant Henry Farndale of the Royal Field Artillery was

admitted to Catterick Military Hospital on 14 January 1918 after severe gas

poisoning. 151907

Gunner John W Farndale was evacuated after a gas attack in September 1918.

He was on the casualty list as a result of being wounded by a gas ‘B’ shell sev, which may have meant severe. He was

admitted to Rouen on 16 September and later to the General Hospital at

Leicester on 22 September 1918.

Graham

Price

The younger

brother of Florence Farndale, Rev

William Edward Farndale’s wife, Lieutenant

Graham Price, was a World War One pilot of the Royal Army Flying Corps,

killed in action, in a duel with a German aeroplane at 8,000 feet. He had

written a letter to his parents shortly before he died, If anything happens

to me do not grieve, but feel thankful that you had a son to give to the

country. In another letter, seeming to foresee his fate, he had written I

would not have been without my experiences for anything in the world, Au Revoir.

His commanding officer wrote This letter is in confirmation of the telegram

of yesterday’s date notifying you of your son’s death. It happened in a flight

in which he was observing for one of our batteries over enemy lines. His

machine was attacked by a German aeroplane and after fighting for fifteen

minutes at a height of 8,000 feet, your son received a direct hit in the heart

and was killed immediately. It was a wonderfully plucky fight against heavy

odds, and although the result was fatal for him, I know that this was the end

that he would have chosen for himself, to die fighting, hot headed, in a great

fight in the greatest of all causes. He was a very fearless and gallant

officer, so dead keen on his work and so thoroughly efficient. I feel that his

loss is irreplaceable. The Chaplain had written Your son put up a most

glorious fight, and has sacrificed himself for his country and friends. Greater

love hath no man than this, that he lay down his life for his friends.

15271 Private

(later Corporal) William Farndale served with the Yorkshire Regiment (Green

Howards), having enlisted on 12 October 1914, soon after the outbreak of the

war. In October 1915, in a letter to friends at Great Broughton, he

jocularly remarks that, now he has gone, he has got the Germans on the run.

18981 and 577701

Private Harry Farndale was from Stockport, but had been a cleaner with the

United States Cotton Company, Foundry Street, Central Falls, Rhode Island, USA

shortly before the first world war. He served with the 7th Battalion, The East

Lancashire Regiment. Harry enlisted on 15 February 1915 at Liverpool. He sailed

from Plymouth to France on 25 and 26 May 1915. He served in France and Belgium

from May 1915 to July 1916 and from May 1917 to April 1919. He took a bullet

wound to his left ankle on 1 July 1916 and was taken to Brook War Hospital and

Garden Hurst Hospital. His arm was out of place caused by a broken arm, which

didn’t trouble him until it twisted out of place in 1917 by a fall at No 2 Rest

Camp while playing football.

2216 Private Alfred

Farndale, 9th Lancers worked on a splitting machine in Leeds before the

War. He served with the 9th Queen's Royal Lancers who landed in France as part

of the 2nd Cavalry Brigade in the 1st Cavalry Division in August 1914. The

Regiment participated in the final lance on lance action involving

British cavalry of the First World War. On 7 September 1914 at Montcel à Frétoy Lieutenant

Colonel David Campbell led a charge of two troops of B Squadron and overthrew a

squadron of the Prussian Dragoons of the Guard.

1813 and

475088 Private William Claude Farndale worked Norwich, in a saw mill and

later as a tinsmith. He was attested into the Army on 16 September 1913, aged

17. He served with the 1/2 East Anglian Area Field Ambulance Company, Royal

Army Medical Corps who served in Gallipoli. After the initial stalemate at

Gallipoli, in August 1915 additional regiments arrived from Britain, mainly raw

recruits from Kitchener’s New Armies. William’s Medal Records show he served in

the Balkans from 16 August 1915, which almost certainly meant he served in the

Gallipoli campaign, as part of the August reinforcement.

88th

Field Ambulance manhauling an ambulance wagon off 'W'

Beach, Cape Helles, Gallipoli, 27 April 1915

|

The full story of

the many soldiers from the family who took up arms in the First World War |

|

The

context of the First World War to the Farndale Story |

Scene 6 - The Inter War Years

543695 Charles

Farndale was born at Huttons Ambo

and became a groom. He enlisted into the Royal Tanks Corps on 9 May 1924. He

attested at Winchester. He served with the 13/18th

Royal Hussars (Queen Mary’s Own) and 15th/19th The King’s Royal Hussars

in 1924 and 1925. The 13th/18th

Royal Hussars (Queen Mary's Own) was a cavalry regiment formed by the

amalgamation of the 13th Hussars and the 18th Royal Hussars in 1922. It spent

three years at Aldershot. Lord Baden Powell was Colonel of the Regiment. The

Regimental Riding School ran a very popular musical ride and Cossack display,

and Sergeant Mennell won the All Arms at the Royal Tournament at Olympia

in 1924. The Regiment moved to Edinburgh in October 1925, to Redford Barracks,

which may have been when Charles transferred to the 15th/19th

Hussars. The 15th/19th The King’s Royal Hussars had amalgamated in 1922. At

some stage he joined 4th Battalion, the Royal Sussex

Regiment who he represented in football in 1934.

Scene 7 - The Second World War

Only twenty

one years after the end of the First World War, the nation called upon its

population to take arms again, this time against the aggressive Nazi war

machine. Many of those who had witnessed the horrors of the first war at first

hand, became witnesses to a second period of total war. A few took part in both

wars, but generally it was the sons of the Great War veterans who were called

upon to serve their country this time.

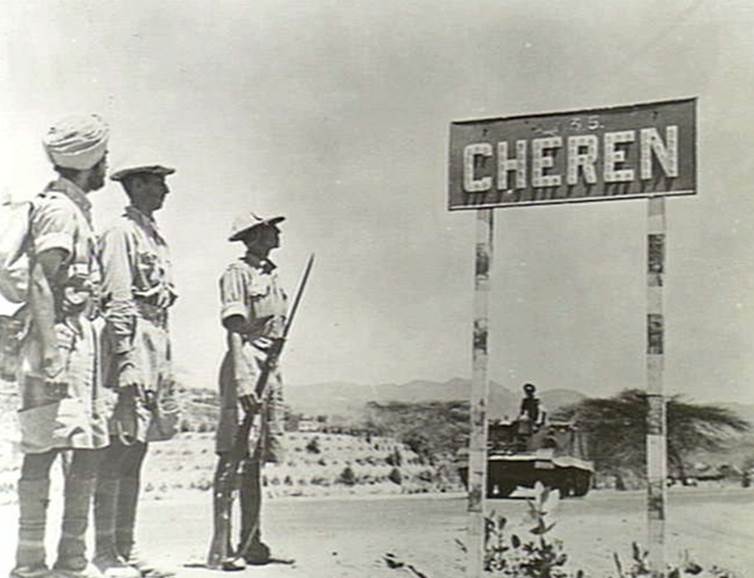

4460826 Private James

Farndale was born in Stockton in late 1916 and enlisted into Second

Battalion The West Yorkshire Regiment (Prince of Wales Own) Regiment. In March

1941, he deployed to East Africa in the operation to retake British Somaliland

from the Italians. Keren was the last Italian stronghold in Eritrea and the

scene of the most decisive battle of the war in East Africa in early 1941.

Guarding the entrance from the western plains to the Eritrean plateau, the only

road passing through a deep gorge with precipitous and well

fortified mountains on either side, Keren formed a perfect defensive

position. On these heights the Italians concentrated 23,000 riflemen, together

with a large number of well sited guns and mortars. The

Battle of Keren took place from 3 February to 27 March 1941.

At 07.00

hours on 15 March 1941, the British and Commonwealth troops of 4th Indian

Infantry Division attacked the Italian defenders from Cameron Ridge. The 2nd

Highland Light Infantry led the attack on the lower features, known as Pimple

and Pinnacle. They were pinned down, suffering casualties, and without

supply until darkness provided the opportunity to withdraw. By moonlight that

evening, there was a two battalion attack on Pimple and Pinnacle,

with a third battalion ready to pass through and attack a fort which had become

an Italian stronghold. The capture of Pinnacle that night by the 3/5th

Mahratta Light Infantry led by Lieutenant-Colonel Denys Reid, with the 3/12th

Frontier Force Regiment less two companies under command to take Pimple,

was called one of the outstanding small actions of World War II, decisive in

its results and formidable in its achievement.

In the early

hours of 16 March 1941, the Italians counter-attacked Pinnacle and Pimple

for several hours. The defences at the fort were depleted and during the

counter-attack, the 2nd West Yorkshire Regiment made their way over a seemingly

impossible knife-edge to surprise the defenders at their fort, which was

captured after a determined defence by 06.30 hours, with 40 prisoners taken.

James died of wounds on 16 March 1941 in Eritrea, aged 24. That is all we know,

but it presumably occurred during this assault. He is buried at Keren

War Cemetery in Eritrea.

1824896 Sergeant Bernard Farndale married Muriel Glenys Picton Swales in 1933 in Merthyr Tydfil and their son, Brian Picton Farndale, was born in 1934.

By 1944,

Bernard was a sergeant with No. 115 Squadron RAF, operating from RAF Witchford

near Ely.

The Squadron

was equipped with the Avro

Lancaster Mark 1 and took part in a series of raids over Germany in August

1944. Bernard was a flight engineer.

On the

evening of 29 August 1944 nearly six hundred RAF bombers flew over Denmark on bombing

raids to Königsberg and Stettin. Bernard was the flight engineer on LAN ME

718. The aircraft bound for Stettin in particular were attacked by German night

fighters, when they were passing the northern part of Jutland and the

Kattegat. Bernard’s aircraft, the Avro Lancaster I LAN ME718, was hit over Denmark when

it was attacked by a German night fighter and caught fire. At about 1 am, it

crashed near Ove northeast of Hobro, killing all onboard. The bomb load

exploded when the Lancaster hit the ground spreading wreckage and the remains

of the crew over a wide area. After being hit the Lancaster flew for a moment

through the air before it crashed like a burning torch at Ove, north of the

Mariager Fjord in Denmark. All of the bomb load exploded on impact. All of the

crew were killed.

The Germans

did not want to collect the remains of the crew and left them in the field. The

locals were appalled and collected the remains in wickerwork baskets. The

Wehrmacht ordered the Danes to hand the baskets over, and these were thrown in

the crater at the crash site and covered. When the Germans had left the area,

the locals opened the crater and placed the remains in a coffin, which was

driven to Ove church. On 4 September 1944, unknown to the Wehrmacht, the airmen

were laid to rest in Ove cemetery. Vicar A. Bundgård officiated at a graveside

ceremony. The coffin was decorated with flowers, but there were only a few

mourners. Apparently the German Wehrmacht knew nothing of this funeral.

The Crew

of ME 718

|

1912 to 1944

The full story of Bernard Farndale and the fate of flight LAN ME

718 |

19199623

James Noel (“Jimmy”) Farndale enlisted into the Army on 15 December 1942

and served with the US Army Air Corps in World War 2 in USA and in Europe. He

received his basic training in Fresno, California, and received his radio

trading at Scott Field, Illinois. He was assigned to the ferry command in

May 1944 and was then engaged in delivery of aircraft to various

theatres of war.

Jimmy

Farndale 15 April 1945, Taken

at the Derby Club, San Francisco

22 April 1945, Taken at the Derby Club, San Francisco

On 8 August

1944 and 16 October 1944 he flew missions for Air Transport Command from

Casablanca to La Guardia Airport, New York. He was a Private and 21 years old,

but promoted to Corporal by October 1944. On 14 November 1944, he flew a

mission from Prestwick in Scotland to New York. Serving as a radio operator

aboard planes being delivered to all parts of the world, Corporal James N

Farndale of Las Vegas has touched every continent in the globe except Australia

in the past six months, and made a forced landing in India. Corporal Farndale

has been spending a furlough in Las Vegas with his parents, State Senator and

Mrs James Farndale, 922 S 2nd St, and was scheduled to report back for duty

today with the 4th Ferry Group at Memphis, Tennessee.

The crash

landing occurred on a flight to India some time ago, but the pilot got the ship

down safely without injury to any crew member. The landing was made in a small

clearing in the jungle, near a native village, Corporal Farndale stated in an

interview here. “We camped right in the plane, and natives brought us food,

including breadfruit, bananas, coconuts, melons and water. Everything was free

except eggs, and we had to pay for them,” he said. A holiday was declared in

the village school so the children could see the plane. From daylight to dark

the natives crowded about the plane, just standing staring at the big machine.

The crew stretched ropes around the plane to hold the crowds back, because they

kept inching forwards closer and closer to the big ship. The children behaved

well but were very curious he said. “We visited one day in a native home,”

Corporal Farndale said. “An old man who had been reared in a missionary school

and spoke English very well was our host. He was a landowner and very proud to

show us all the things he raised on his land. Almost everything grew

bountifully there. The children of the household were very well behaved,” he

said. After three days in the grounded plane, the crew was reached by a rescue

party composed of American and British soldiers, who led them back to camp.

In March

1945, his father,

a US Senator for Nevada, wrote to his brother, Alf,

two veterans of the last War. I don't know whether or not you have heard

that Jimmy made one flight to England. He had your address but he said while he

was in England they wouldn't let him out of camp long enough to even try to

telephone or visit. He came over by way of Brazil, there crossed the Atlantic

to the coast of Africa and up north across Portugal and then landed I think in

the Land's End area, where they delivered the plane and then went through

London and north to Scotland crossing back to the US by plane. He had a great trip

but was naturally disappointed in being so close to you and yet not able to see

you. But that is the way with war as you both know from our experience in the

First World War. Jimmy made two flights to India, and was wrecked in the

jungles near Calcutta I believe, was stranded among natives for two days, and

they had to leave the plane. He has visited Cairo twice and has seen many of

India's important points. He now is in the Pacific, but he is still back in the

US. They make trips over into the various isles about every two or three weeks.

He is sure getting experience and is seeing the world. He is not satisfied when

he is not in the air. They are keeping him busy now.

521789 Corporal

Henry Stuart Farndale was granted a commission as an Acting Pilot Officer

on probation in April 1941, for the duration of hostilities. He had married

Maria Pratchett in 1940 in Bradford, but

she died, aged only 27, in late 1942. On 30 July 1943, he was a pilot under

training with No 7 Elementary Flying Training School, a Royal Air Force flying

training school at RAF Desford.

Instructor

and pupil in front of a de Havilland Tiger Moth at 7 EFTS, Desford. Both wear

1930 Pattern flying suits

521789

Corporal Henry Stuart Farndale, a pilot under training, flying Tiger Moth

T6910, died on 11 May 1945, aged 28. DH82A Tiger Moth T6910 collided with

T5982 and crashed Elmdon 11.5.45 DBF.

John Horace

Thomas Farndale, known as Horace, joined the Royal Engineers initially

repairing searchlights. His daughter, Patricia was told that he then trained to

be a Spitfire pilot and he took her to a cemetery behind RAF Coltishall where he showed her the graves of his squadron,

killed in the Battle if Britain. There were many eighteen to twenty years olds, and many were Polish. John couldn’t fly on the day

when many members of his Squadron were shot down due to a heavy nose bleed.

Horace

Farndale

He later

joined the catering branch, which he hated. He was later trained for the Far

East Theatre, and avoided being posted to Burma, where many of his friends died

on the construction of the Burma railway. John recalled seeing doddle bugs

decimate London. There was an occasion when his soldiers were training in a

gymnasium when it was hit, but John had not made it on time so was not there. He

was also trained in a secondary duty as a paramedic. On another occasion

Patricia was told that a bomb dropped next John and he curled himself up in a

ball and survived an explosion. He used to tell his family my guardian angel

was with me when that bomb exploded.

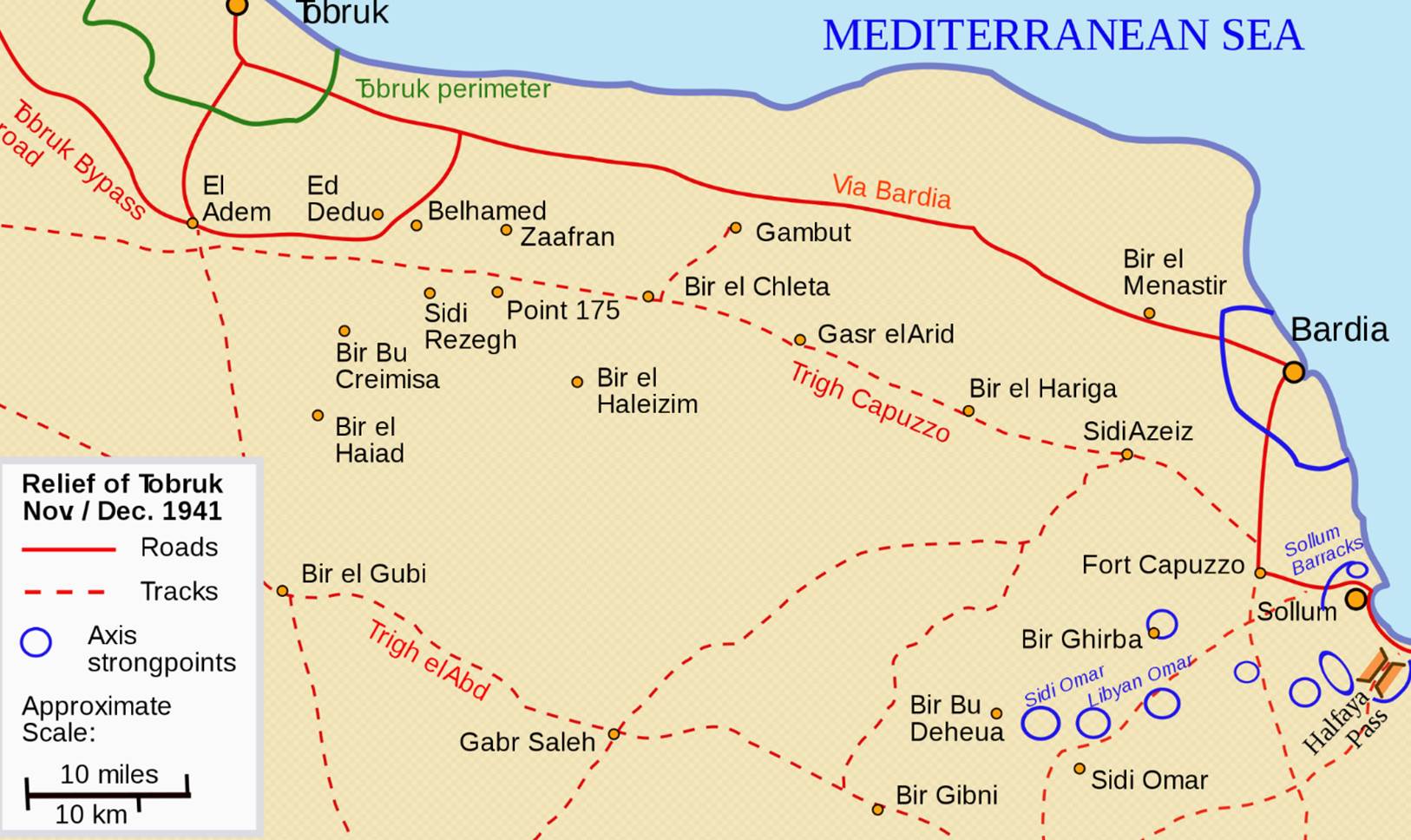

Ronald

Martin Farndale served with 6th

Field Ambulance Royal Army Medical Corps (“RAMC”) in Greece and

Crete with the Second

New Zealand Expeditionary Force. He was captured at Sidi Rezegh

in 1941 and was a prisoner of war in Italy for the rest of the war. The Battle of Point

175 was a military engagement of the Western Desert Campaign that took

place during Operation Crusader from 29 November to 1 December 1941.

4th and

6th New Zealand Field Ambulance at overnight camp, North Africa, 1 October 1942

Maurice

Muir served as Regimental Stretcher Bearer with 24 Battalion and was

captured at Sidi Rezegh on 1 December 1941 with Ronald Farndale. Maurice was

awarded the Military Medal for protecting his Regimental Aid Post from friendly

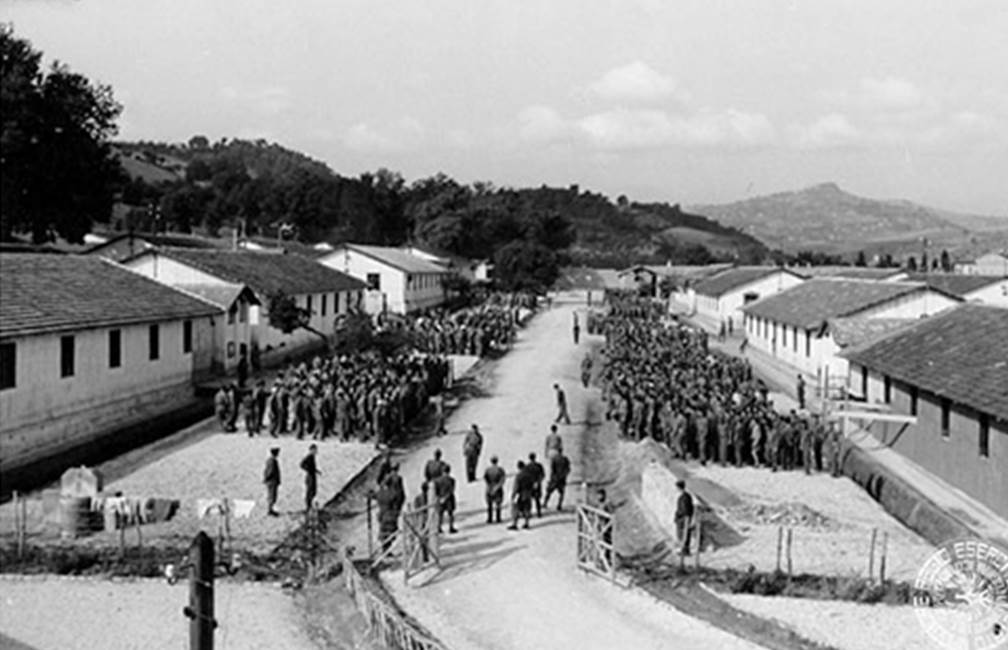

fire. They were transported by German Ship from Tripoli to Naples, then to

Capua (Campo PG 66). In March 1943, the PGN 66 camp in Capua was described as a

sorting camp with a capacity of 200 places for senior officers and 6,000 for

non-commissioned officers and troops. It was made up partly of barracks and

partly of tents. It began operating in April 1941. There is evidence of the ill

treatment of prisoners there.

Camp 59, Servigliano

They were transported to Servigliano (Campo PG59), then to Chiavari (Campo PG52).

Camp 52, Chiavari,

Italy, 1942. Photograph taken by W A Weakley. Note on back reads All beds and

gear out for a search. Note where bed slats have been taken off to provide fuel

for brewing tea.

Maurice Muir

was later transferred to Lucca Hospital (PG202) in September of 1942, and

repatriated to the UK in April 1943 along

with 400 or so British and 14 other New Zealanders who had relatives in

Britain. Ronald Farndale was with Maurice Muir.

New

Zealand Prisoners of War on their repatriation in June 1943

Ronald Farndale

970929 and

292503 Private Raymond (“Ray”) William Stainthorpe Farndale served in 59th

(Newfoundland) Heavy Regiment Royal Artillery. Ray later recalled that a

large number of my friends chose the Army, as I did. The first contingent of

volunteers from the West Coast left Corner Brook on May 12, 1940. I was not

amongst them, because it seemed unlikely that I would pass the eyesight test.

However, within two weeks I managed to pass, with the help of a young Doctor

who coached me in the eyesight requirements. Ray left Halifax on 6 June

1940. He was on the passenger manifest of the Nerissa on a voyage from

Halifax, Nova Scotia to Liverpool arriving on 6 July 1940. When they arrived in

England, the new recruits were welcomed by their commanding officer, Lieutenant

Colonel John Nelson. Another recruit, Jack

Wescott recalled that Nelson told them, You have listened to a lot of

nice things being said about you. My message is different. You’ll work so hard

that you won’t even hear the sound of the bombers when they fly overhead during

the German air raids. The Newfoundlanders are said to have responded with heavy

cheering.

In 1943,

Raymond was chosen by his Commanding Officer J W Nelson to be a candidate for

Officer training. He undertook training with 23 Office Cadet Training Unit in

Yorkshire for six months from March 1943 and was then accepted for a commission

and became a second lieutenant in September 1943.

Ray was

posted to Tonbridge, Kent to join 23rd battery, 59th Newfoundland Heavy

Regiment, Royal Artillery. 20th and 23rd Heavy Batteries were given 155mm guns

and 21st and 22nd Heavy Batteries were given 7.2-inch guns. The Regiment

trained in Northumberland but by July 1944 it was at Worthing in Sussex.

59th

during firing practice in Britain

Ray landed

at Juno Beach in Normandy on 5 July 1944, one month after D-Day. Jack

Wescott recalled, the 59th hit the beach at Courseulles-sur-Mer,

in southwestern France, better known as Juno Beach, on July 5, 1944. Within 24

hours the men were in action, firing their 7.2” howitzers and 155 mm ‘Long

Toms’ with their respective 200 lb and 95 lb shells at a concentration of

German tanks in a battle for a nearby airport. The men of the 59th would

remain in almost continuous action for the rest of the war, often firing 24

hours a day in support of Canadian, British and American troops as the Allies

fought their way through blasted out villages and ruins of towns in France,

Belgium and Holland on the way to Germany.

The Regiment

took part in the battles for Caen, when 23rd Battery provided

counter battery fire during the assault. The 59th took part in the grim

action at Caen, in the fierce fighting at Falaise, in the historic battle for

the closing of the gap (better known as the Battle of Bulge), at Esquay and Errecy, and its guns

also covered the crossing of the river Odon and the crossing of the River Seine,

wrote historian Allan

M. Fraser. Batteries of the 59th were among the first soldiers to liberate

the key supply port of Antwerp, where they were greeted by the city’s mayor who

presented each of them with a bottle of wine and a pack of cigars. In many of

the places they fought in Holland, the land was flooded and dry places to camp

were scarce. The Newfoundlanders made a name for themselves by being able to

cobble together the best shelters and for being able to navigate their guns and

trucks over the worst of the mud clogged and troop packed roads as they shifted

as much as 150 miles at a run to come to the aid of infantrymen fighting

pitched battles against the Germans.

The Regiment

suffered its first injuries on 17 July 1944, when enemy fire wounded 12 men,

causing one to lose a leg, and destroyed two guns. Following early Allied

successes in August 1944, the 59th Regiment pressed east and continued fighting

in Belgium and the Netherlands before proceeding on to Germany. The Regiment

took part in the Battle of the Falaise Pocket from 122 to 21 August 1944 and

Operation Market Garden in September 1944. During the Battle of the Bulge the

four batteries of the 59th Regiment repealed the German drive to the River

Meuse. In the Battle of the Bulge, which saw the Germans launch a desperate

surprise attack to cut off the British army from its supplies and separate them

from the American troops, the men of the 59th reinforced their reputation for

accurate firing, devising the best camps in the worst conditions, and for

manhandling their big guns and supplies over ice and snow blocked roads, all

with “exceptionally high” morale. While some American soldiers froze to death

in the harsh winter conditions, the men of the 59th gathered wood from the

ruins of bombed out houses to line the floors and walls of their two men tents,

jimmied stoves and heaters out of empty milk cans, and even, at times, rigged

up electricity to light their camps. Frustrated by their accurate firing – in one instance a

battery of the 59th snuffed out seven German observation posts in a row,

landing 26 direct hits on one position – the Nazis would order bombing raids

over the men of the 59th and their guns.

On 2 May

1945, the Regiment fired all of their batteries at the key Germany city of

Hamburg, their last rounds of the war, two days before the city’s German forces

surrendered. For the next 8 weeks, the Regiment helped in the administration

and rerouting of refugees.

Winston

Churchill with the Regiment’s howitzers

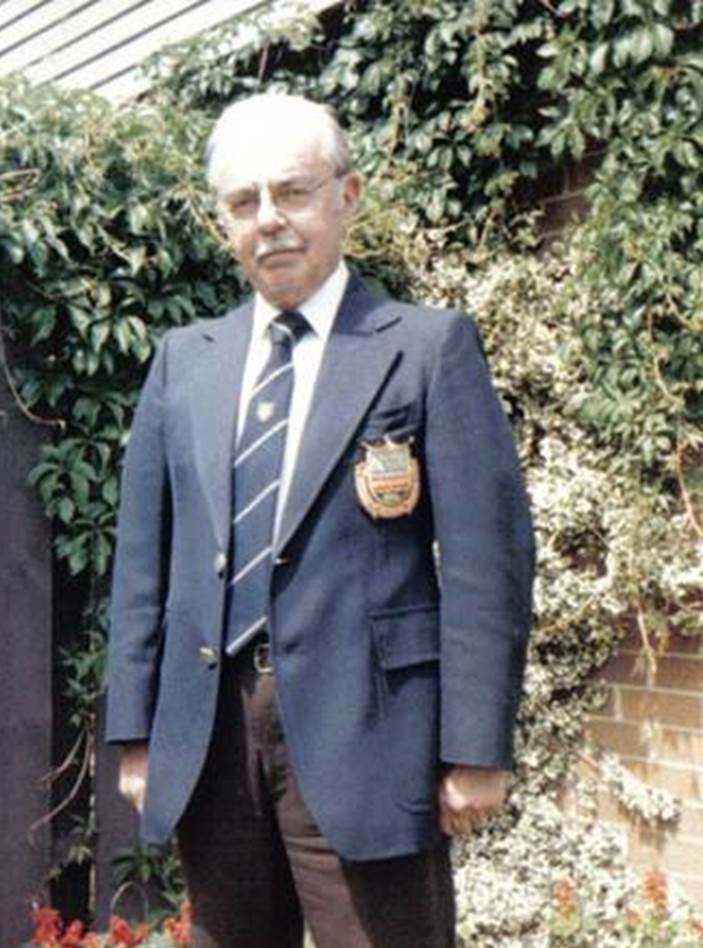

Raymond

Farndale, RCA, 1943

Ray in about 1974

Ray

continued to strongly support veterans’ affairs. He lived to be the oldest

living member of the Farndale family. In July 2015, 101 year old Veteran,

Raymond “Poppy” Farndale, sat with his medals and war scrapbook in front of his

portrait at Guelph Public Library to support the Hundred Portraits and

Hundred Poppies project. He said I thought it was an important project

to remember those who have served in the military or had some association with

the military. Not only do I feel strongly about the poppy and what it

symbolizes, my 2 grandchildren (Christopher and Emily) call me “Poppy” so it is

quite special to me. He added that I was remembering the people I met

during World War 2. I am one of the few veterans left from my regiment and I

felt I was representing all of the amazing men and women I worked alongside.

He advised, While a lot has changed since I was born, 101 years ago, some

things have remained the same. One thing I have always lived by, treat others

as you would like to be treated. If you do this, you can never go wrong.

Wilfred

Gordon (“Gordon”) Farndale was the grandson of John

George Farndale who had fought in the

Crimean War. He served as a Flight Lieutenant in the Royal Canadian Air

Force in World War 2 in Europe and later became an accountant. Clarence

Edward Farndale was Gordon’s brother, who served with the Royal Canadian

Navy. He served from 15

March 1939 to 17 August 1945 and then from 25 February 1947 to 12 August 1966.

Gordon

Farndale, 1944 Clarence

Farndale, 1960 Clarence and

Gordon Farndale (Brothers in Arms)

36014559

Private Richard William Farndale joined the army on 28 March 1941 in

Chicago, Illinois. He was a Mechanic with the 43rd Division for 32 months in

the Pacific. The 43rd Division was mobilised on 24 February 1941. The 43rd

Division was originally sent to Camp Blanding, Florida where it was based

before participating in the Louisiana Manoeuvres of 1941 and the Carolina

Manoeuvres later that same year. The division relocated to Camp Shelby,

Mississippi on 14 February 1942. On 19 February 1942, it was reorganised as a

triangular division so that it had three infantry regiments. The division

prepared for overseas operations at Fort Ord, California on 6 September 1942

and departed from San Francisco on 1 October 1942. The division arrived in New

Zealand on 23 October 1942, before being committed to combat in the South West

Pacific Theatre under the command of General Douglas MacArthur. It saw

campaigns in New Guinea, Northern Solomons, and Luzon. Rendova was the major

staging point for the assault on the island of New Georgia. The assault on New

Georgia was met with determined enemy resistance. The Japanese fought fiercely

before relinquishing Munda and its airfield on 5 August 1943. Vela Cela and

Baanga were taken easily, but the Japanese resisted stubbornly on Arundel

Island before withdrawing on 22 September 1943.

Soldiers

of 4rd Infantry Division landing on Rendova Island in the Solomon Islands on 30

June 1943

Dick

received his discharge from the Army in May 1945.

4272378 Cyril

Ernest Farndale enlisted into the Royal Artillery on 30 August 1939 and

served in 100 Anti Tank Regiment Royal

Artillery.

Sergeant

William Derrick Farndale was promoted to Sergeant and led the Withernsea

Patrol of the East Riding Home Guard on the Holderness coast.

Cecil

Farndale Phillips

Lieutenant

Colonel (later Brigadier and Major General after the War) Cecil Farndale

Phillips commanded 47 (Royal Marine) Commando during the assault in the Le

Hamel area on 6 June 1944. After the War he was promoted to Major General and

became Chief of Amphibious Warfare.

|

The Second World

War soldiers, sailors and airmen

The full story of the Farndales who took up arms in the Second World War |

|

The

context of the Second World War |

Scene 8 - The Cold War years

General

Sir Martin Farndale KCB joined Indian Army 1946 and was commissioned into

Royal Artillery October 1948 from the first intakes at the Royal Military

Academy Sandhurst. He served Egypt, Germany, Malaya, Northern Ireland, and

South Arabia. He was Commander in Chief of the British Army of the Rhine and

commander of the Northern Army Group of NATO.

Martin

Farndale started his military career in 80th Light Anti-aircraft Regiment in

the Suez Canal Zone. In January 1949, he sailed by Troop Ship to Egypt with his

great friends, John Ansell and Bill Nicholas. Soon he was selected for the

elite Royal Horse Artillery and he joined First Regiment Royal Horse Artillery

in 1950.

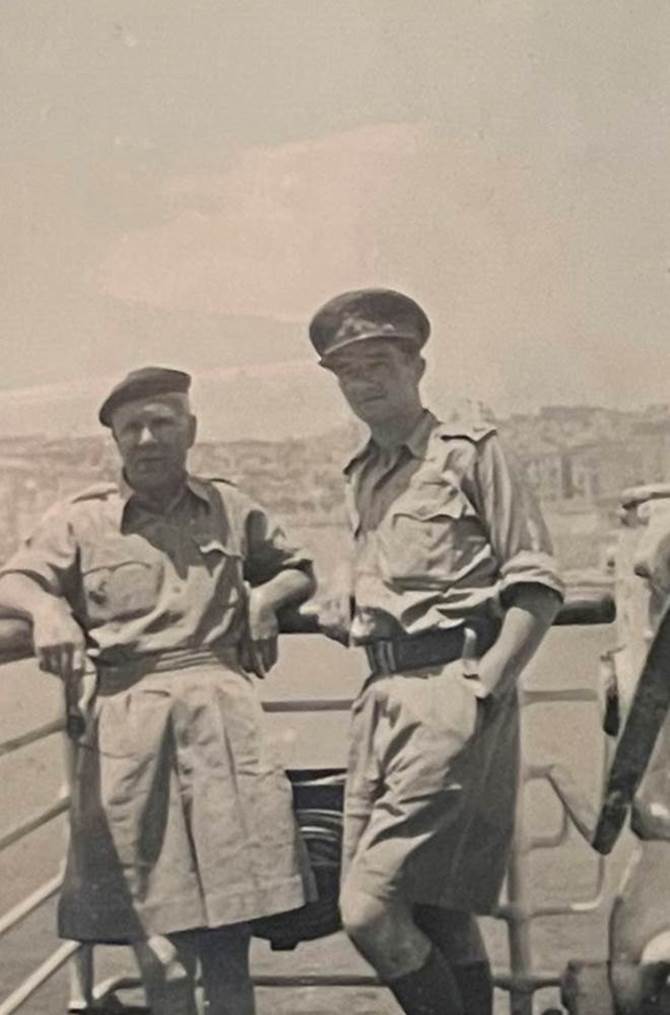

On the

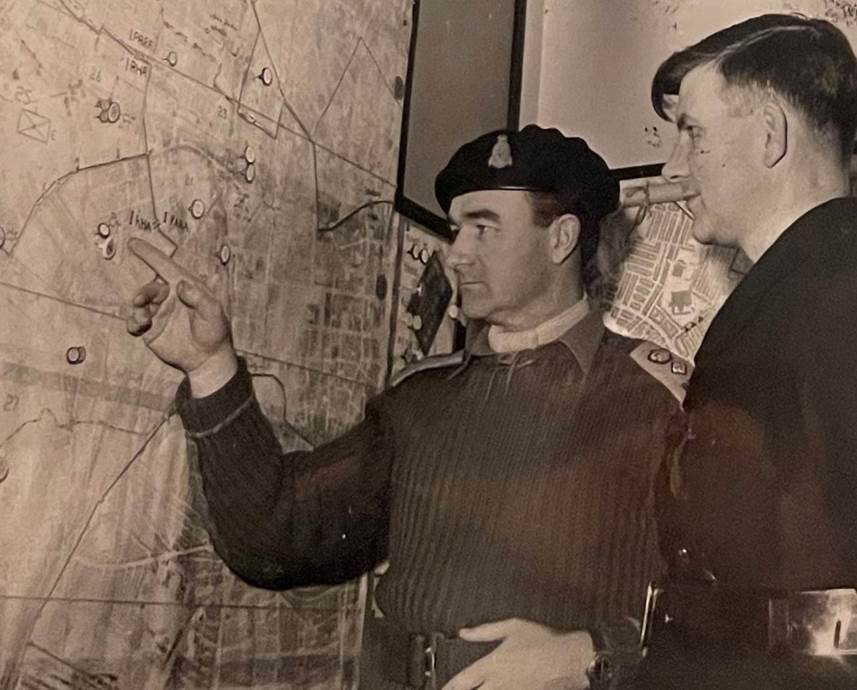

Troop Ship to Egypt Field

Marshall Montgomery (“Monty”) inspects Martin Farndale’s Troop, Fayid, Egypt

He joined the Gunner Staff of 17th Gurkha Division in Malaya from 1960 to 1962, where he saw active service during the final phases of the Malayan Campaign.

He was a

Battery Commander in Aden during the Radfan Campaign in the arid mountains of the Protectorate.

From 1969 to

1971, Martin was given command of First Regiment. He was the first artillery

commanding officer to take his regiment to Northern Ireland and to serve in an

infantry role on the streets of Belfast. He was also the first Lieutenant

Colonel to command a warship. Accommodation was sparse in those early days, so HMS

Maidstone, which was destined for the breaker's yard, was instead sailed

from Portsmouth to Belfast and acted as a maritime barracks for the Regiment.

His command included a hundred sailors, the Maidstone's maintenance team.

In his role

as Director of Operations at the Ministry of Defence Martin Farndale organised

the disarming of guerillas in order to facilitate the creation of the new

nation of Zimbabwe.

He was Colonel Commandant Army Air Corps. He learnt to fly

a helicopter and built up a considerable log of flying time, particularly

during his later commands in Germany.

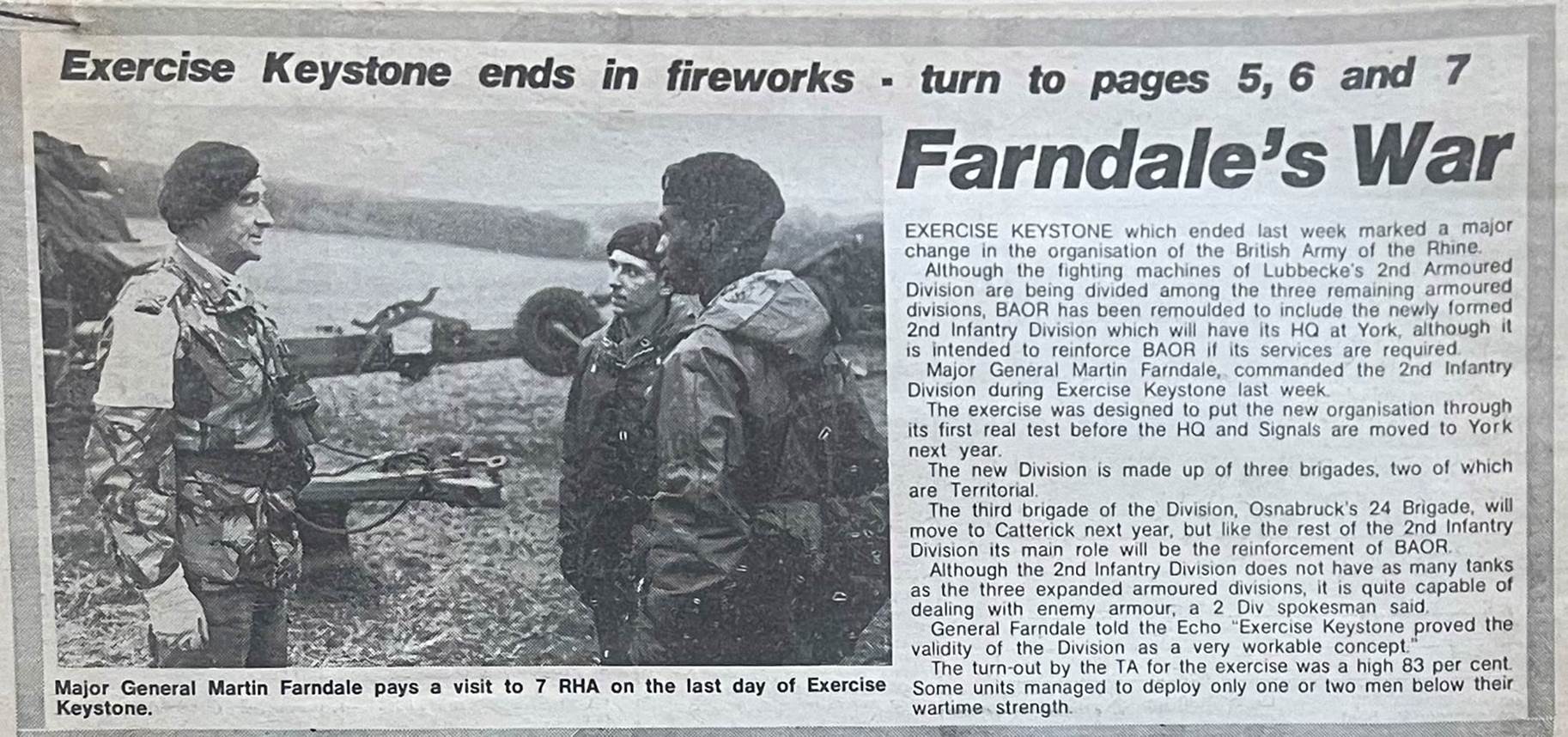

Martin commanded 2nd Armoured Division as Major General from June 1980 to March 1983. He commanded the Division during Exercise Spearpoint in September 1980, during which the Division's 14,000 men and 150 tanks took the full weight of an enemy Orange simulated Soviet break-in. He also planned Second Division's Exercise Keystone in November 1982.

Major General Farndale meets a Russian General observer

during Exercise Spearpoint 1980

He commanded 1st (British) Corps as Lieutenant General from March 1983 to 1985. This was the fighting component of the British Forces in Germany, still during the height of the Cold War. The Headquarters was at Bielefeld and he lived at Spearhead House. In those days, tests and demonstrations of ability to withstand an invasion from the east were critical to keeping the peace and winning the Cold War. In 1984, he devised and oversaw the vast Exercise Lionheart, a show of strength of the height of the Cold War, which involved 131,000 British troops, including tens of thousands or Territorials and Army Reservists and which extended over 3,700 square miles. During a second phase a further 6,300 German, 3,500 Dutch, 3,400 American and 165 Commonwealth (from Australia, New Zealand and Canada) took part. It was intended to test BAOR's reinforcement plans and was the biggest military exercise to be held since the Second World War. In September 1983, he showed the Prime Minister, Margaret Thatcher, around his Corps during an exercise, during which now infamous photographs were taken of the later Lady Thatcher riding in a Chieftain tank.

With the Prime Minster, Margaret

Thatcher With

the Defence Secretary, Michael Heseltine

Martin

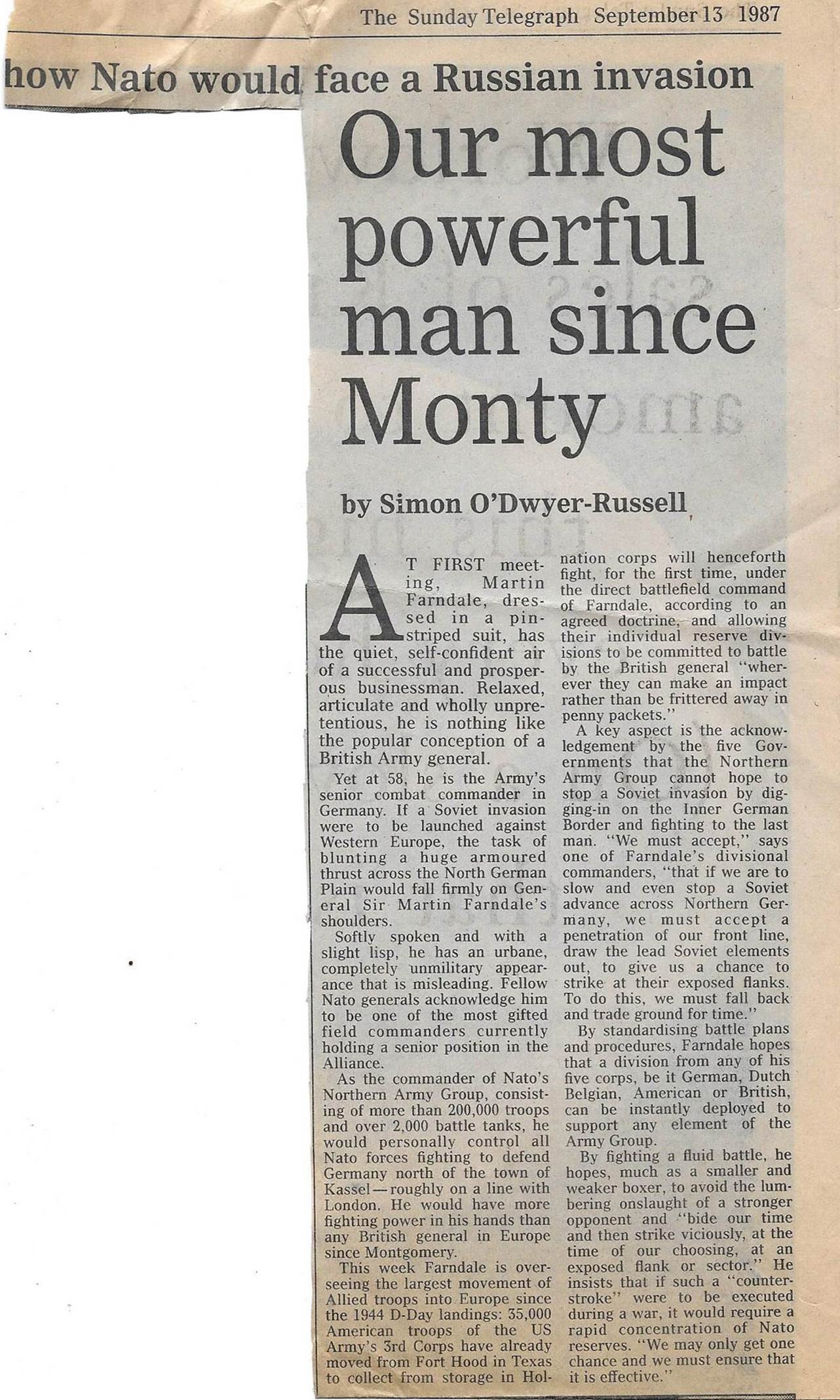

then commanded the British Army of the Rhine, at the time 55,000 strong, and

also commanded the Northern Army Group, an Army Group consisting of a British,

Dutch, German, and American Corps, from its headquarters at Rheindalen. This was from 1985 to 1987. He implemented a

revised concept of operations for the Northern Army Group. In the event of a

Soviet invasion, the new plans would enable NATO forces to bide our time and

then strike viciously, at the time of our choosing, at an exposed flank or

sector. He invented a strategic concentration of force and firepower, known

as the Farndale Cocktail.

|

An explosive blend of Farndale

firepower |

These

new plans were tested in 1987 during another major exercise, Exercise

Certain Strike, which proved itself to be the largest and most complex

field exercise of its type staged in Europe since the D-Day landings in 1944.

Martin became Master Gunner of St James' Park, an office dating back to the seventeenth century, the honorary head of the Royal Regiment of Artillery, on 5 November 1988. His principal duty as Master Gunner was to keep the Queen, the Royal Regiment's Captain General, informed of all matters pertaining to the Royal Artillery. He was also Colonel Commandant of the Royal Horse Artillery, Honorary Colonel of First Regiment Royal Hose Artillery and of Third Battalion, the Yorkshire Volunteers, his home county. He was Colonel Commandant of the Army Air Corps. He also had a close interest in the South Notts Hussars.

Martin was

a passionate historian and as well as his genealogical work, he wrote

definitive histories of the Royal Artillery, a task which he started early in

his military career and continued until he died. He wrote the History of the Royal Artillery, France 1914-1918 (published

1987). He wrote the History of the Royal Artillery, The Forgotten Fronts and

the Home Base, 1914-1918 (published 1988). He wrote the History of the Royal Artillery in the Second World War

(The Years of Defeat 1939-41) (published 1996). He wrote

the History of the Royal Artillery (The Far East Theatre

1941-1946) which was published posthumously. He also wrote many

articles for the British Army Review and the Royal Artillery Journal.

He was also

Chairman of the English Heritage Battlefields

Trust from 1993. The trust endeavours to preserve battlefields

from being destroyed by new roads of buildings. Martin succeeded in saving the

site of the Battle of Tewkesbury (1471) from developers.

Martin was

described in an obituary as an innovative army commander whose leadership

qualities took him to Malaya, Northern Ireland and NATO, unquestionably the

most distinguished gunner officer of his generation. He had an outstanding

career both in command and on the staff, but was never more at home than when

among soldiers in the field. He was an example of what can be achieved with a

combination of leadership, intellect, personality, charm and dedication.

Martin Farndale

was an exceptional man, who lived an exceptional life. He was generous of

spirit, an inspiring leader, a true comrade in arms and a firm friend. The

world is poorer for his passing but his achievements will be remembered for

many a year to come.

|

General Sir Martin

Farndale KCB 1929 to 2000

The original

author of this genealogy who led the British Army and Northern Command of

NATO in the crucial years of the Cold War |

Keith

Alan Farndale was from New Zealand, and served as a Petty Officer in the

Royal Navy.

James

Henry Farndale served with 1st Battalion Kings Own Scottish Borderers. Gary

R Farndale served with the British Army on The Rhine.

Scene 9 - Gulf War 1

Six hundred

years after his namesake was enrolled into the army of Henry V, Richard

Farndale was commissioned into the Royal Artillery in 1987 from the Royal

Military Academy Sandhurst and served in Germany, with the United Nations

Forces in Cyprus in 1990, and as an artillery forward observation officer

during the First Gulf War in early 1991. He was later Adjutant of First

Regiment Royal Horse Artillery, and after retiring from the Regular army, a

Battery Commander of 207 Battery, 105 Regiment (Volunteers) Royal Artillery

equipped with Javelin air defence missile system. He was awarded the UN Medal

for service in Cyprus, and the Gulf War Medal.

There are

still Farndales serving in the armed forces today.

or

Go Straight to Act 33 – the Modern

Family