|

|

The Military Farndales

Exploring the Farndales who served in the armed forces

|

|

Introduction

Dates are in red.

Hyperlinks to other pages are in dark blue.

Headlines of the history of the

Middleham are in brown.

References and citations are in turquoise.

Contextual history is in purple.

Those members of our family who gave their lives in service for

their country

The Royal Navy in 1741

Able

Seaman Giles Farndale (FAR00137) was a

press ganged sailor in the Caribbean, who served on HMS Experiment, and

was buried: At Sea, at Port

Royal, West Indies on 9 May 1741.

The First World War

3758 & 201065 Private Richard

Farndale (FAR00681)

died in France either from wounds, enemy shelling or sickness, on Monday 26th

February 1917 aged 19 while serving with 150th Infantry Brigade of the 50th

Northumbrian Division. He was buried at La Neuville Communal Cemetery, Corbie,

Somme. His name is on a War Memorial at Coatham.

15/319

Private (later Lance Corporal) George Farndale

(FAR00617)

was killed in Action at the Battle of Arras, on Thursday 3rd May 1917.

333852

Private George Farndale (FAR00646) was

killed in Action at the Battle of Arras on the 27th

May 1917.

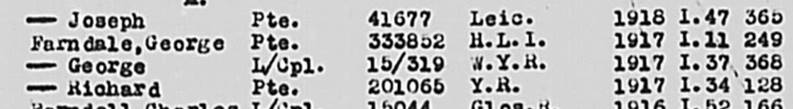

Name

Rank No Unit Year Vol Page

Index to War Deaths 1914-1921 – Army

(Other Ranks)

William Farndale (FAR00647) was

wounded in action at Vimy Ridge

on 13 December 1916 while serving with the 28th Battalion. He had a gunshot

wound in the right forearm and was in hospital in Epsom, England. He was

discharged from the Army at Calgary on 18 February 1918. He was awarded the

British War Medal and the Victory Medal. After his return to Regina, despite

his weakness from his wounds, he used his car to evacuate the sick during the

great ‘flu epidemic of 1918. He caught the ‘flu while still weak from his wound

and died at Earl Grey, Saskatchewan, Canada, aged 25 years on 23 November 1918.

The Second World War

4460826 Private James Farndale (FAR00833) aged

24 of the West Yorkshire Regiment died of wounds on 16th March 1941 in Keren

Eritrea. His memorial is 3.A.3 at Keren War Cemetery in Eritrea.

1824896 Sergeant Bernard Farndale

(FAR00783)

115th Squadron RAF, was killed in action over Denmark on 30 August

1944 during a bombing raid.

521789 Corporal Henry Stewart Farndale (FAR00832) died

on 11 May 1945 aged 28. He was a pilot under training whose aircraft crashed.

His memorial is at section V Grave 265, Leeds (Lawns Wood) Cemetery.

For the Fallen

Poem by Robert Laurence Binyon

(1869-1943)

|

With proud thanksgiving, a mother for

her children, Solemn the drums thrill: Death august

and royal |

There is music in

the midst of desolation They went with songs to the battle,

they were young, |

They shall grow not old, as we that

are left grow old: They mingle not with their laughing

comrades again; |

But where our desires are and our

hopes profound, As the stars that shall be bright when

we are dust, |

The memorial at Great Ayton |

“I see the lives for which I lay down my life,

peaceful, useful, prosperous and happy, in that England which I shall see no

more. It is a far, far better thing that I do, than I have ever done; it is a

far, far better rest that I go to than I have ever known.”.

A Tale of Two Cities, Charles Dickens

Medieval Farndale Soldiers

Given the multiplicity of spellings of

surnames in medieval times, a

table has been compiled to explore possible medieval soldiers who may have

been part of the family.

It seems likely that John Farendon was John de Farendale (FAR00035A)

of the York Line, who probably

served as an archer with expeditionary forces to Scotland in 1383 to 1389,

later joined by his probable brothers Henry Farendon

(FAR00035B)

and William Faryndon (FAR00035C).

Richard Farendale of Sherifhoton (FAR00044)

may have served in the Hundred Years War in Brittany in 1380; an expeditionary

force to Scotland in 1400; and may have served with Henry V in the Agincourt

campaign or afterwards, with records in 1417 and 1421 possibly placing him at

Harfleur and the Siege of Mantes. When he died he left

an impressive catalogue of military equipment including a horse, saddle and

reins, and armour, comprising a bascinet (medieval combat helmet), a breast

plate, a pair of vembraces (armoured forearm guards)

and a pair of rerebraces (armour designed to protect

the upper arms) with leg harness.

Naval service in the Caribbean

1740

Able

Seaman Giles Farndale (FAR00137) served

with the Royal Navy from 29 June 1740 until he died at sea in the Caribbean on

9 May 1741. It seems very likely that he was press-ganged at Whitby, when he would have been 27 years old. The Muster

Book for HMS Experiment, a brig with a compliment of 130, shows

Giles Farndell as No 101 Able Seaman, impressed on 29 June 1740.

He is present at every muster until 9 May 1741 when he is marked ‘DD’

(“Discharged Dead”). No circumstances are recorded which probably means that he

died of sickness on 9 May 1741.

He

almost certainly took part in the

War of Jenkins’ Ear in the Spanish Main under Admiral Vernon and was

probably involved in the Battle

of Cartagena de Indias in March 1741.

The

‘Experiment’ was commissioned under Captain Hughes at Deptford between Mar and

Jun 1740. On 29 June 1740 the ‘Experiment’ was at The Nore where

Giles Farndell (or Farndale; he is listed under both names in

different Muster Books), came on complement. From there she sailed for

Port Royal, Jamaica where she arrived on 15 Sep 1740. From there until

June 1741 the ship was either in Port Royal, at sea, or in Cartagena (Adm 36/1081 & 1082).

Since Giles was not recorded as ‘from…another ship’ he probably had not served

on another.

HMS Experiment taking the Telemaque, 8

July 1757

The Crimean War

Private John George Farndale (FAR00337) saw

service between 1853 and 1856 possibly first with the Coldstream Guards and

then with the 28th of Foot.

He served in the Crimean War in 1854 and 1855. There is a

full record of his service on his webpage.

His letters home included the following records:

We then started for Sebastopol, and

reached it after eight or nine days’ march; we had to go a great way round. As

soon as we got in front and settled, we commenced throwing up batteries and

breast works, under fire of the enemy. We finished them after about five days

and nights’ hard working, and opened fire on them on

the 17th of last month, and have been battering away ever since, and are likely

to continue doing so for some time to come. We have greater opposition than we

expected. There was a faint attack made on our rear army a few days ago, which

cut up our cavalry fearfully, but were defeated in the end. Our loss is not so

great, considering all the circumstances of the case. I have escaped as yet, thank God! I have had a narrow escape: one morning,

as we were relieving guard, two privates and a sergeant were shot close by me

with one ball.

I have been laid up in my tent with frost bitten feet nearly

all this month, but I am better again and fit for duty.

The siege is progressing very slowly

but I think we will soon open a new siege. Things begin to look a little

better. We have received the winter clothing and are getting provisions a

little better. We want the wooden houses next, although I think as we have done

so long without, we could manage without them altogether. However I hope that

before you get this, Sebastopol will be ours and then we will be thinking about

returning to old England again.

If I live to see it over and get back to old England again,

which by the blessing of God I hope to do, I will tell you tales that will make

your hair stand on end!

The Period of the Franco Prussian War and the British Expedition to

Abyssinia

There was a John Farndale, who was discharged from

the Grenadier Guards on 25 July 1872. He received £10 compensation. He served

for 3 years and 323 days (Chelsea Pensioners

Discharge Documents). This was most likely to have been John Farndale of

Clerkenwell London (FAR00379).

The Boer War

N Farndale, served during the Second Boer War 1899

to 1902, Regimental Number 4505, Second Battalion The

Buffs East Kent.

The Second Battalion, the Buffs. Roll of

Individuals entitled to the South Africa Medal and Clasp under Army Order

Granting the medal, issued 1st April 1901. … 4805, Pte, Farndale N.

The Mid

Sussex Times, 22 August 1899: The local team’s opponents on Thursday

were the Buffs, who, batting first, knocked up 151 … The Buffs … Private

Farndale, caught Allen, bowled G A Hammond, 6 runs.

The 2nd Battalion, 3rd

Battalion, 1st Volunteer (Militia) Battalion and 2nd Volunteer (Weald of Kent)

Battalion all saw action during the Second Boer War with Captain Naunton Henry

Vertue of the 2nd Battalion serving as brigade major to the 11th Infantry

Brigade under Major General Edward Woodgate at the Battle of Spion Kop where he was mortally wounded in January 1900.

The phrase ‘Steady the

Buffs!’ was popularised by Rudyard Kipling in his 1888 novel ‘Soldiers

Three’. The origins of this phrase come

from Adjutant John Cotter during garrison duties in Malta, who encouraged the

men of the 2nd Battalion with ‘Steady the Buffs! The Fusiliers are watching

you’ as he did not want to be shown up in front of his former Regiment The 21st

Royal Fusiliers.

Following the end of the

war in South Africa in June 1902, 540 officers and men of the 2nd battalion

returned to the United Kingdom on the SS St. Andrew leaving Cape Town in early

October, and the battalion was subsequently stationed at Dover.

Sergeant William Leng Farndale (FAR00539)

was a Sergeant in the Northumberland Hussars in 1902. They had served in the

Second Boer War, so he may have served there.

There was an F A

Farndale-Williams who was a second lieutenant with the Moulmein Volunteer

Rifles on 30 March 1907 who appeared under Indian Army Orders (Homeward Mail from India, China and the East, 3 June 1907).

The First World War

If any question why we died,

Tell them, because our fathers lied.

Rudyard Kipling, after the death f his

son at the Battle of Loos

Wilfred Owen denounced Horace’s

patriotic maxim, “Dulce

et decorum est pro patria mori,” (“It is sweet and fitting to die for one's country”)

as “the old Lie”.

The Great War haunts the British memory.

750,000 lives (one in three of all British males aged 19 to 22 in 1914) were

lost and 9M soldiers in Europe died.

It was seen as a struggle for freedom,

HG Wells’ the War that would end all wars.

The causes

Tensions between France, Russia, Britain

and Germany had been increasing since the turn of the century.

Britain had been most concerned by

French rivalry in Africa and Russian rivalry in Persia.

Things grew complicated though when

Germany started to increase its navy from 1900. Lord Selbourne, first lord of

the Admiralty, saw this as a direct threat to Britain, though in reality it was

probably an attempt by Germany to force Britain out of any war by threat.

The ententes with France in 1904 and

Russia in 1907 were aimed at curbing German military build ups and in 1909

Britain had pledged to outbuild Germany in its navy, with Lloyd George’s

People’s Budget enabling it to build more Dreadnaughts.

From 1908 Germany, France and Russia all

started to build up gold reserves in case of war.

In 1908, the German general staff

developed the Schlieffen Plan in secret. Its strategy was to launch a

devastating attack through Belgium to defeat France within a month before

turning to Russia before it had time to mobilise. Speed and surprise were of

the essence. An attack on the Belgium city of Liege was scheduled for Day 3.

There was still the possibility of war

with France and Russia, but Germany continued to increase its battleship

programme from 1912. The British ambassador in Vienna predicted the coming

crisis with significant accuracy.

The Admiralty responded with a naval

treaty with France, so that France would focus on defending the Mediterranean

and Britain the North Sea.

Yet Germany and Britain remained the

biggest trading partners. Admiral von Tirpitz, head of the German navy sent his

daughters to Cheltenham Ladies College, and German naval officers bought their

dress uniforms in Saville Row. By 1913 relations with Germany were improving.

The Balkans had become the arena of

tension and a growing antagonism between Austria-Hungary and Russia. Slav

nationalism threatened multinational Austria-Hungary.

By 1914, German confidence was ebbing.

Helmut von Moltke felt the French and Russians would be too strong by 1917 and

it was now or never. If an ultimatum to Serbia could intimidate Russia and

France into backing down, all would be fine.

Britain still regarded Germany as

leading the way in the arts and sciences. It was more concerned about Ireland.

However it was worried about making an enemy of Russia if it failed them now

and a desperate French ambassador threatened that if Britain let France down,

it would watch the future ruin of the British empire.

The events that led to war

On 28 June 1914 the

open topped car carrying Archduke Franz Ferdinand, heir to the Austro-Hungarian

throne, took a wrong turning in Sarajevo, Bosnia and reversed, allowing a

Bosnian Serb student, trained by the Serbians, to kill him with two bullets.

On 23 July 1914

Austria-Hungary delivered its ultimatum to Serbia to formally and publicly

condemn the "dangerous propaganda" against Austria-Hungary; to accept

an Austro-Hungarian inquiry into the assassination; and to take steps to root

out and eliminate terrorist organisations within its borders including the

Black Hand believed to have helped the assassin.

On 24 July 1914,

Asquith and Grey mentioned the Serbian crisis in the first discussion of

foreign affairs for a month. The Liberals and its Labour allies were

overwhelmingly opposed to war. Bankers and businessmen were aghast at the

thought. So Grey invited Germany, France and Italy to

a conference in London.

On 28 July 1914

Austria-Hungary declared war on Serbia and bombarded Belgrade.

On 1 August 1914,

George V on foreign office advice urged Russia to stop its mobilisation in a

letter addressed to Dear Nicky, from Georgie.

On 2 August 1914

Asquith made a statement to the Commons asserting that to stay neutral would

sacrifice Britain’s reputation. This changed public opinion in favour of

intervention.

On 4 August 1914

Germany attacked Belgium. The British Empire declared war on Germany at

midnight.

Was there any alternative?

The Russians had assumed that Britain

would join the war, and war with Britain caused no significant hesitation in

Berlin.

There was certainly a misunderstanding

of the consequences of decisions in 1914, anticipating a likely duration of 3

to 8 months.

Germany would probably have been

victorious if not for British intervention. An optimistic view might have

foreseen German victory leading to an European Union

eight decades ahead of schedule. Germany did not have war aims when war broke

out. However Belgium would likely have become a vassal

state and German bases would directly have threatened Britain. Holland might

have become dependent and Germany would likely have

established a continuous central African colonial empire and the vast

territories of Russia would have been thrust back as far as possible, German

rulers were likely intending to establish authoritarian rule rather than

struggle for democracy, What German soldiers did in massacring over 6,000

civilians in France and Germany might give some indication of the threat.

War was not taken lightly in Britain.

The myths of a thrill for the fight was in reality

more marked by foreboding and alarm. The New York

Times reported that there was no flag waving; once war began

civilians rallied to send off their troops, which is often depicted in

photographs. A quick and easy victory was not really expected, the all over by Christmas phrase appearing

only in 1917.

The Start of the War

On 6 August 1914,

the British Expeditionary Force (“BEF”) comprising all UK based regular

troops supplemented by reservists, totalling 11,000 men of whom 75,000 were

combat troops, was sent to northern France using 1,800 special trains, 240

requisitioned ships and 165,000 horses, even with some London buses.

By then there were 1.7M German and 2.4M

French troops on the battlefield.

It was expected that 75% would be killed

or wounded, which was to prove an underestimate.

The BEF came in the path of 580,000

Germans advancing through Belgium.

On 23 August

1914, the BEF fought a defensive battle at Mons.

On 26 August

1914, they fought another defensive battle at Le

Cateau.

They inflicted heavy casualties on a

tightly packed German force.

In October 1914 the

first of four bloody battles was fought at Ypres.

These were the deadliest battles of the

war. By the end of 1914, the French had lost 528,000; the Germans 800,000 and

the BEF were generally wiped out, having lost 90,000. On the Eastern Front the

Russian steamroller had also been halted, by a smaller German force.

Mobilisation

Kitchener realised this was to be a long

haul. He appealed for volunteers. However time was now needed to train them, so

there could be no significant reinforcement from volunteers until late spring

1915. Britain would continue to rely on volunteers until 1916 as conscription

was unpopular, and there was no system in place for it.

By the end of 1915, 2,466,000 men had

volunteered, about a third of those eligible. Industrial workers including

miners and railwaymen formed more than half the army. Agricultural workers

joined in lesser numbers, partly as the land still had to be tilled, but partly

because they tended to be older due to the prewar rundown of agriculture. There

was a significant response from the upper and middle classes, from public

schools, the peerage, and bankers. Asquith lost a son as did the Irish

Nationalist leader John Redmond.

A volunteer force, whilst less efficient

at fast mobilisation, provided a force of high morale, motivated and

enthusiastic. There was a degree of choice allowing more time to adjust, and giving more control over the nature of service.

Their discipline was often founded on friendship. Pals Battalions drew on

neighbourhoods, churches and political identities. Scotland provided

particularly high numbers and the empire supplies millions more. There was

considerable moral pressure to join.

Class distinctions were maintained in

the ranks, but officers felt a gentlemanly duty to their subordinates and an

obligation of courage and leadership. By the end of the war, a third of

officers were from the lower middle and working classes, all expected to

emulate traditional standards.

Conscription started in 1916. By then it

had popular support, with growing hostility to ‘shirkers’.

The first units of Kitchener’s New Army

sailed in summer 1915, and by summer 1916, there were 30 divisions in the

field. They included men like Siegfried Sasson, Robert Graves, Rupert Brooke,

Wilfred Owen, Harold Macmillan and J R R Tolkien, who

found some of the inspiration for Lord of the Rings.

It took time to convert the experience

of colonial campaigns to the realities of industrial warfare.

In 1914, the BEF had only 24 heavy guns,

by 1918, it had 2,000. By 1916 fifty times the prewar annual output of TNT was

used each day.

Few generals believed in a quick

breakthrough, the exception being the commander in chief, General Sir Douglas

Haig.

Eastern theatres of

operation

A group emerged, the ‘Easterners’,

hoping to avoid the horrors of France, by opening an alternative front. The

biggest idea was pressed for by the First Lord of the Admiralty, Winton

Churchill, to send a fleet to Constantinople and force the Turks to surrender.

On 18 March 1915,

an Anglo French fleet sailed into the Dardanelles and in the face of mines and

shore batteries, British, French Australian and New Zealand (“ANZAC”) troops

were forced to land on the Gallipoli

peninsula, where they were fought to a standstill. They were finally evacuated

in December 1915 and January 1916. Allied casualties were some 390,000. The

determination and ability of the Turks had been underestimated.

After Gallipoli the Turks forced the

whole British-Indian army in Mesopotamia to

surrender. A British and Indian army marched from Basra to Baghdad in 1915, but

was forced to surrender after the Siege

of Kut in 1916.

In 1916 support was given to an Arab

revolt against the Turks, involving the young Oxford archaeologist, T E

Lawrence, the only romantic hero of the war.

British, Indian and ANZAC troops

eventually took Jerusalem, Damascus and Baghdad in 1917.

The Balfour

Declaration

in November 1917 committed Britain to a National Home for the Jewish people

in Palestine. It seemed a clever plan, and would

please a Jewish population influential in America. In time this would lead to

an intractable and damaging problem.

The Western Front

The French, Russians, British and Serbians

agreed to simultaneous offensives in summer 1916. The biggest effort was a

Franco attack along the Somme.

The Germans struck first and aimed to

‘bleed the French army to death’ in the killing ground of Verdun.

The Easter Uprising in Ireland was in

April 1916.

On 4 June 1916 the

Russians launched a long and costly offensive and the Italians followed on 15

June 1916.

The British prepared for the attack at the Somme. General

Charteris worried that the casualty list would be long – Wars cannot be won

without casualties. I hope people at home realise this.

On 1 July 1916 the

British army began one of the bloodiest battles in its history. At 7.30am after

an artillery bombardment of 12,000 tons of shells, 55,000 British and French

soldiers advanced out of their trenches, with 100,0000 to follow. In places the

advance seemed to go well; Siegfried Sassoon noted that men were cheering as in

a football match. However the artillery bombardment

had failed to destroy the barbed wire and the attack soon became nightmarish,

with soldiers mown down. By the end of the first day, there were 19,240 dead

and 37,646 wounded, including 75% of the officers.

The Battle of the Somme continued over a

for an a half month campaign. More attacks between 3

and 13 July resulted in a further 25,000 casualties. But,

gradually, the British tactics improved.

The Germans soon felt the strain. The

Germans lost heavily and their army would never be the

same again. Strategically the French army was preserved after the Verdun

disaster. Total casualties were 420,000 British, 200,000 French and 465,000

German.

The Russian army and state fell apart in

1916 to 1917.

There were mass surrenders and

desertions in the Austrian army.

The British army was largely amateur and

there was some resistance to free discussion of ideas, and no system for

learning and applying lessons, but similar issues arose in other armies,

including the German high command. Some senior officers, including Haig, were

ill equipped for the challenge, but there were new younger generals and

brigadiers emerging.

The Allies agreed to another offensive

in 1917.

In March 1917,

the French army launched an offensive in Champagne in which they lost 130,000

casualties.

The Battle

of Arras (also known as the Second Battle of Arras) was a British offensive

on the Western Front during the First World War. From 9

April to 16 May 1917, British troops attacked German defences near the

French city of Arras on the Western Front. The British achieved the longest

advance since trench warfare had begun, surpassing the record set by the French

Sixth Army on 1 July 1916. The British advance slowed in the next few days and

the German defence recovered. The battle became a costly stalemate for both

sides and by the end of the battle, the British Third Army and the First Army

had suffered about 160,000 casualties and the German 6th Army about 125,000.

In July 1917 the

British began the Third Battle of Ypres (Passchendaele), with Haig convinced

that this was a critical moment in the war. Unseasonable August rain slowed

progress and soon the advancing force found itself bogged down and sinking,

with soldiers crawling for shell holes and sinking in the mud. The British lost

about 275,000 and the Germans 200,000.

In October 1917 the

Italian army collapsed at the Battle

of Caporetto.

The German army was starting to show

signs of disintegration.

The British army

Soldiers were not permanently in the

trenches. They generally spent about 15 months on the Western Front, with

perhaps a third of the time, in short periods, on the line. They relieved

stress with superstitions, religion, folklore, letters and sport. A black

humour developed and satirical newspapers like the Wipers Times. However trench warfare was a drudgery. The British army

remained remarkably cohesive. It kept the soldiers busy. On the dark side, the

British executed more of its own men, about 400, 75% for desertion, than the

Germans. However the junior officers supported by

chaplains generally instilled loyalty and strong motivation. There was

reasonable food, regular leave and rest, and means to let off steam. There was

also a general acceptance of the rightness of the cause.

War at Sea

The War at sea saw early action when the

Australian ship HMAS

Sydney was sunk by a German cruiser and a German squadron was destroyed

near the Falklands.

German cruisers attacked British

shipping from the start of the war. Most were caught and sunk.

Britain used its commercial and naval

power.

There were two opposing fleets in the

North Sea – the German High Seas Fleet and the British Grand Fleet at Scapa

Flow and Rosyth, with 28 dreadnaughts and 9 battlecruisers.

The Germans had some success with

bombardments on Scarborough and Hartlepool. But German naval commanders were no match

for the British fleet, at best ambushing smaller units.

On 31 May 1916 a German fleet stumbled

across the whole British fleet commanded by Admiral Sir John Jellicoe. The Battle of

Jutland involved 250 ships and was the biggest concentrated naval battle in

history. It only lasted about 2 hours. The German fleet escaped and inflicted

higher casualties on the British fleet, sinking 3 battlecruisers. However in

practice the differences were small, and whilst proving the vulnerability of

British battlecruisers, from a strategic perspective, the battered German fleet

fled back to port and never risked action again,. An

American newspaper explained that the German fleet had attacked its gaoler, but remained in gaol.

Between August 1914 and October 1916,

trade with the US quadrupled. Britain subsidised its allies, advancing them

£1.6B, mainly to Russia and France, most of which was never repaid.

However Britain’s blockade of Germany was not

decisive and as it continued to trade with states like Holland and Scandinavia,

it could not significantly degrade German commerce without impacting on its own

financial institutions.

An Order of Council on 7 July 1916

procured the buying of neutral goods to deprive Germany. Meat consumption in

Germany fell and its economy came under increasing pressure, sinking by 30%,

with a spread of disease in the population.

The Germans retaliated with its U boat

campaign and to work it required to torpedo shipping without warning, which was

seen internationally as a war crime. After the Lustitania sank in Mau 1915,

American anger caused a temporary suspension of the attacks, but by January

1917, when US involvement became inevitably, the attacks resumed. By early

1917, the Admiralty and government were alarmed as the scale of large scale

sinkings.

One of the motives for Passchendaele was

to seize submarine bases on Belgium.

US entry into the war

After uncovering a German plot that

Mexico would attack to recover Texas and Arizona if the US entered the war, USA

declared war in April 1917, with a series of peace initiatives at first.

The last German offensive

In March 1918 war in the east ended with

the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk, when the Bolsheviks sought peace.

German troops now concentrated on the

western front and aimed at a decisive victory before US troops could swing the

balance. Field Marshall von Hindenburg and the Kaiser planned the offensive.

The main blow would be against the BEF at a chosen weak point where the British

and French armies met.

The German

attack, Operation Michael, started on 21 March 1918.

After a barrage of 3M shells, 59 German divisions led by storm troopers with

flame throwers and machine guns, cloaked by fog, attacked 26 British divisions.

The British were outnumbered 8 to 1. Gaps opened in the British lines and

between 23 to 26 March 1918, the British were

forced to retreat. The Germans advanced about 40 mile4s on a front of 50 miles

and the German fleet was ordered to disrupt a likely British evacuation from

Dunkirk.

By 28 March 1918,

the British reinforced by the French, started to stop the German advance. In

the face of air attacks from the British and devasted ground, the Germans grew

exhausted. Having committed 90 divisions to the attack, they lost 240,000. They

had not taken their key objective, the key railway hub at Amiens. By April 1918, they were bogged down and stuck.

Another German offensive further north

also became bogged down.

Still, at this stage, the German idea of

an acceptable peace was unrealistic.

The Germans shifted their attacks to the

French lines and began a devastating surprise attack at Chemin des Dames, 70

miles north east of Paris on 27

May 1918. Despite local successors, they did not achieve strategic

success.

The Allied counter

offensives

A French counter offensive on 18 July 1918, involving British, American and Italian

troops, showed the German army was out of steam.

On 8 August 1918,

the Germans were completely surprised by a counter offensive near Amiens

by 552 British tanks leading Canadian, Australian, British and French infantry.

The massing of tanks allowed the Allies to push forward 8 miles, one of the

longest one day advances of the war.

The most decisive campaign was fought in

Autumn 1918. The Germans were dug in to the Hindenburg line, six layers deep.

On 29 September 1918 the 46th (North Midland) Division stormed

across the deep Saint

Quentin canal, where it was assumed to be impossible to cross, and the

Germans started to fall back from a continuous British attack.

The end

Few expected the end when it came. The

British were anticipating that the war might continue to 1920 by this stage. However the German army, state and society were collapsing.

On 5 October 1918 the Germans asked

President Woodrow Wilson for an armistice, based on his ‘Fourteen points’

proposed in January 1918, with a withdrawal from occupied territory, but with

continued German self government, and no punishment

for Germany. The Allies didn’t relish invading and governing Germany.

On 11 November 1918 at 11 o’clock, the

fighting stopped. The BEF, now 1,859,000 men, half of then teenagers, halted

just north of Mons, where it had all begun.

The memory

The memory of the Great War is uniquely

poignant. It came to occupy a place in the national culture. The war had

involved the whole nation, one household in three suffered a casualty, one in

nine a death.

The emphasis in commemoration was not on

victory but on the deaths. Kipling called the dignified Cenotaph ‘the place of

grieving’. The memory was marked by the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier at

Westminster, by vast war cemeteries continuously maintained by the Commonwealth War Graves Commission, and by

Armistice Day, a time of collective mourning of sacrifice and incomparable

loss, and the two minute silence.

The incomprehension at the memory left

no narrative of idealism, as against Fascism in the Second World War.

Disillusion continued to grow after the

Treaty of Versailles failed to match the idealised hopes for aftermath.

By the 1920s the League of Nations

seemed to have hopes of success. By the 1930s, the population had been left

with urgent reasons to reject war, which might have led to wrong choices made

then.

The horrors of the war were remembered

in R C Sheriff’s Journey’s

End (1928), the memoires of Robert Graves, Goodbye to

All That (1929) and Siegfried Sassoon, Memoirs

of an Infantry Officer (1930) and the German Erich Maria Remarque’s

novel All

Quiet on the Western Front (1929).

The First World War had not ended war.

By the 1960s it was remembered with mockery and pathos as in Joan Littlewood’s Oh

what a lovely war.

(Robert

Tombs, The English and their History, 2023, 582, 597 to 644).

Perhaps though the situation was very

different to opposing Hitler’s threat in 1939, and the First World War arose

out of mutual misunderstanding and mistrust, and might

have been avoided by dialogue beginning in sufficient time to have unwound the

spring. Mediation and dialogue might have had a place in avoiding the

catastrophe in 1914, whilst appeasement had no place in retrospect in opposing

a maniac in 1939.

Farndales in the First

World War

The

Battle of Arras, where two Farndales gave their lives

There

is a Table showing the

details of all Farndales who served during World War 1.

104633

Gunner Albert Edward Farndale (FAR00667)

served with the Royal Garrison Artillery. He was awarded the Victory Medal

and the British War Medal. He died in Northallerton

on 17 April 1971.

83795

Private Alfred Farndale (FAR00683) served

with the Machine Gun Corps after initially joining the East Yorkshire Regiment.

My grandfather, he was born 5th July 1897, joined in 1916 and served in France

and Mesopotamia. He was discharged in 1920. He was awarded the Victory Medal,

the British War Medal, and the Police Medal WW2. He died in May 1989 and is

buried in Wensley, Yorkshire.

Alfred Farndale, East Yorks, 1914 Alfred

Mesopotamia

See also Pilgrimage

to Passchendaele, a killing field haunted by family memories.

2216 Private Alfred Farndale, 9th Lancers (FAR00690) served

with the 9th Lancers. He was awarded the British War Medal, Victory

Medal and 14 Star.

2483

Private Charles E Farndale (probably FAR00656, born

1893) served with the Hertfordshire Regiment and was awarded the 15 Star with

Clasp.

Charles Farndale served with the

8th/18th Hussars.

3/28913

Private Charles Farndale (FAR00629)

served with the Leicestershire Regiment & 19th London Regiment and

was awarded the Victory Medal. He was born in Knaresborough in 1888 and died at

Ripon on 16 February 1941.

15/319

Private (later Lance Corporal) George Farndale (FAR00617)

served with 15th Battalion The West Yorkshire Regiment (Prince of

Wales’s Own) and was awarded the Victory Medal, British war Medal, 15 Star. He

was born in Guisborough in 1888; arrived in Egypt

on 22 December 1915 but was Killed in Action at Arras on Thursday 3rd May 1917.

He is buried and commemorated at the Arras Memorial, Pas de Calais, France.

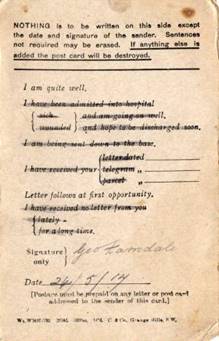

333852

Private George Farndale (FAR00646) served

with the Highland Light Infantry (“HLI”). Born about 1891 in Egton, youngest son of John Farndale (a Deputy in an

ironstone mine, born about 1851 in Egton, Yorkshire) and Susannah nee Smith

(born 1853 in Cropton, Yorkshire, a resident of Loftus,

he enlisted at Whitby probably into the Green Howards

and was then transferred to the HLI. He was killed in action on 27th May 1917

aged 26 while serving with the 1st/9th (Territorial Glasgow Highlanders)

Battalion of the Highland Light Infantry in 100th Infantry Brigade of 33rd

Infantry Division in operations against the Hindenburg Line. George Farndale

was killed in action on the 27th of May 1917, during the Battle of Arras,

barely one month after arriving in France. He was awarded the Victory Medal and

the British War Medal.

Sunday 8/4/17, Dear Sister

Just a line to tell you that I arrived at

Folkestone at 7 o clock this morning and I am in a rest camp now waiting of a

ship. It is quiet a fine place here. I think we shall leave here at 10.45 am

for the ship which I think will take us to Boulogne where we will stay over night. I got a very descent breakfast here and had an

extra tea before we left Catterick. They also gave us 20 packet of cigarettes

each. Well tat-ta for the present will write you

again as soon as possible. With Love Geo

19/4/17

Dear Sister

Received latter on Tuesday last and parcel today. I

must say the parcel was extra. The cake is excellent, also must say that you

could not have sent a more suitable parcel. Well I

must send you my sincere thanks for your kindness also for writing to the Girl.

I am sorry I had to send home for some money, but I only get 5 francs here, and

I want to get some of those French cards to send you as I know you would like

some of them. I am pleased to hear you are all keeping well. I wrote to the

Girl on Sunday so I am expecting to hear from her

anytime. Will you send me one of your photos as I would like one with me out

here, please put your name on it. Remember me to all and Give

them my best respects, also down John St. How is Father keeping hope he isn't

worrying about me as I am alright. Well I think this

is about all I have to say so I must draw to a close thanking you once again

for parcel also hoping to hear from you again soon. Well

tud-a-lu

With Love

from Your Loving Bro Geo.

P.S. I am not afraid about the watch and parcel,

as I know the young man I left with is honest and straight in every way, and I

told him he wasn't to go down special with it, he was to post it anytime when

he was going to town.

With Love again

Geo.

Dear Annie

I am just sending you a line to tell you that I am

in a draft and expecting to go out any day. If you haven't wrote and sent the

things I asked for don't trouble, as I may be gone before they arrive and I sharn't be able to take them with me. If I should be here

over the weekend I will write you again on Sunday if

not I will try and send you a line before I leave. I have got all my kit ready

for going but I don't think I shall go before Saturday or Monday. Well be sure and don't worry about

me and tell Father not to, as I shall be alright, and I must say before I go

that you and Father have been very kind to me as I never wanted for anything

and I must say you have done more than your duty towards me. Of

course it may be weeks before I go into the trenches as am sure to be

kept at the base for a week or two. If I should send for anything when I get to

France, be sure and register it, as it will make it more sure

of me receiving it. Well don't write any more until you hear from me again and

don't think anything is wrong if you don't hear from me for a short time, but I

promise you to write you as soon as I possibly can. Well

this is all I have time to say just now, so I will now close, trusting this

finds you all well. Remember me to all. Well

be sure and don't worry about me, and look on the bright side of it as I shall

soon be back again.

With Love, From Your Loving Bro Geo

PS. If the writing pad comes

I will give it to some of the boys as it won't be worth sending it back. I

shall very possibly be sending some shirts home.

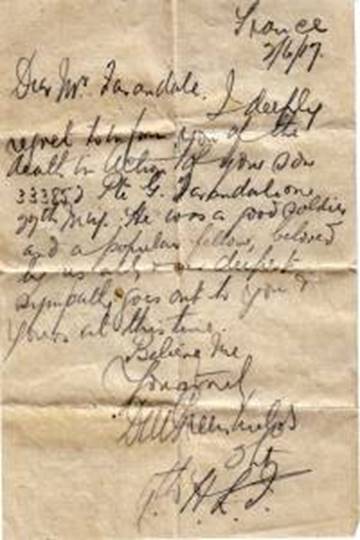

France,

2/6/17

Dear Mr Farandale

I deeply regret to inform you of the death in Action of your son 333852 Pte G Farandale on 27th May. He was a good soldier and a popular

fellow, beloved by us all and our deepest sympathy goes out to you and yours at

this time.

Believe me, Yours truly, D W Greenhulds, 2Lt, 9th HLI.

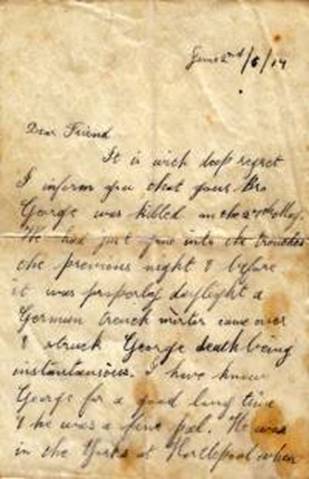

June

2nd/6/17

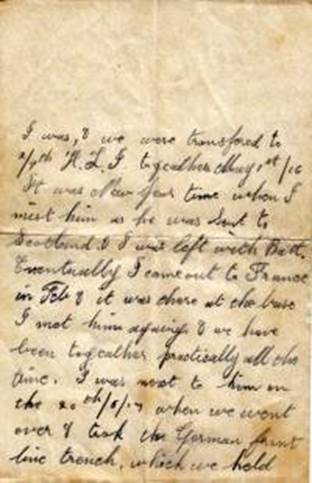

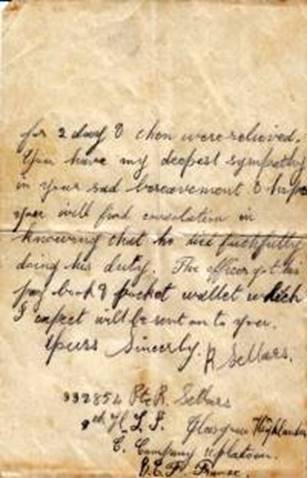

Dear Friend

It is with deep regret I inform you that your Bro George was killed on the 27th May. He had just gone into the trenches the previous

night and before it was properly daylight a German trench mortar came over and

struck George death being instantaneous. I have know George for a good long time and he was a fine

pal. He was in the Yorks at Hartlepool when I was, and we were transferred to

2/9th HLI together May 1st/16. It was New Years time when I mist

him as he was sent to Scotland and I was left with

Batt. Eventually I came out to France in Feb and it

was there at the base I met him again and we have been together practically all

the time. I was next to him on the 20th/5/17 when we went over and took the

German front line trench, which we held for 2 days and then were relieved. You

have my deepest sympathy in your sad bereavement and hope you will find

consolation in knowing that he died faithfully doing his duty. The officer got

his pay book and pocket wallet which I expect will be sent on to you.

Yours Sincerely

R Sellars

332854 Pte R Sellars 9th H.L.I. Glasgow Highlanders

C. Company 11 platoon.

B.E.F. France.

Shingle Hall, Sawbridgeworth, Herts.

Thursday

Dear Miss Farndale:-

I am deeply grieved on hearing from you yesterday

morning that dear George has been killed in action, and all at Shingle Hall

including myself wish to express our deepest sympathy with you all in this dark

hour of sadness.

It was an awful blow to me dear, and is one that I

shall never forget. He was such a nice quiet and gentle boy and was very much

liked by all who knew him in Sawbridgeworth, and no fellow could not think so

much of a girl as your dear brother did of me, and had he been spared to come

back safely we intended getting married. I don't know if he ever spoke about it

to you.

It will be awfully kind of you to copy those

letters for me and shall be most pleased to receive them.

Yes dear, I will see about another doz. p.cs. being copied and will write and let you know, as I

shall be only too pleased to do anything for you, for the sake of the dear one

I have just lost.

He sent me the Yorkshire badge (as he said no one

else should have it but me) also the cap badge of the H.L.I. and bought me a

small regimental brooch of the H.L.I. so I shall always think of the dear boy.

Now dear Miss Farndale I will draw to a close

trusting you will all accept our deepest sympathy once more.

With fondest love hoping to hear from you again

soon

I remain

Your sincere Friend

Dolly.

P.S. Please excuse pencil.

011374

Corporal George William Farndale (FAR00614)

served with the Royal Army Ordnance Corps and awarded the Victory Medal and

the British War Medal. He was born

in Middlesbrough in 1897 and died on 21 August

1954.

19318

Private George Farndale (FAR00646A)

served with the East Yorkshire Regiment and was awarded the Victory medal,

British medal, and 15 Star. He arrived in the Balkans on 12 November 1915. He

was born in Whitby in 1891 and died in Lancaster on 15

May 1954.

G/445

Lance Corporal George James Farndale (later Sergeant) (FAR00653)

served with the Second Battalion, The Royal Sussex Regiment and went to France

on 31 May 1915. He was awarded the Victory medal, British medal, 15 Star and

the Military Medal for bravery.

S4/199459

and TR9/16884 and

18216 George William Farndale (FAR00678)

served with the Army Service Corps and Army Pay Corps. There are quite

extensive military records with his own record.

18981

and 577701 Private

Harry Farndale (FAR00688) served

with the 7th

Battalion, The East Lancashire Regiment. Harry enlisted on 15 February 1915 at

Liverpool. He served in France and Belgium from May 1915 to July 1916 and from

May 1917 to April 1919. He was awarded the Victory medal,

British medal, 15 Star. There are extensive military records on his own page.

204344

Regimental Quarter Master Sergeant Henry Farndale (FAR00681A)

served with the Royal Field Artillery and was awarded the Victory Medal, and

British War Medal. He was gassed in November 1917. He was then promoted to

Regimental Quarter Master Sergeant and was engaged working on a cost accounting

scheme after the War ended. There are extensive records about him on his

personal page. He was born in Leeds in 1883 and died in

Leeds in 1951.

4857

Sergeant Herbert Farndale later 238221 2nd Lieutenant H Farndale (FAR00652)

served with the 10th Yorkshire Regiment (The Green Howards) & 2nd West

Yorkshire Regiment. He was awarded the Military Medal as well as the Victory

Medal, and British War Medal. My grandfather knew him

and we have many of his papers. He lived at Brotton.

He was born Guisborough 30 March 1892 and died on

23 June 1971 at Cleveland Cottage Hospital, Brotton.

Herbert Farndale wearing military medal

in Green Howards Herbert Smith

at officer training unit in 1918

2898

Private Herbert Arthur

Farndale (FAR00664)

served with the Norfolk Yeomanry, then as 43302 in the Northern Regiment,

then as 37425 in the Royal Berkshire Regiment He was awarded the British War

Medal and the Victory Medal.

19832

Private James Farndale (FAR00669) served

with the 1st Devonshire Regiment, then as 35864 in the Wiltshire

Regiment. He arrived in Egypt on 9 October 1915. He served in both World Wars. In WW1 he

tended the horses. His war service was 31 Aug 1914 to 10 Mar 1919 and from 1939

to 1941. He was awarded the Victory medal, British medal, and 15

Star.

TR/5/211407 and 211407 Private W James

Farndale (FAR00704B)

served with 53rd Battalion, West Yorkshire Regiment. He joined very

shortly before the War ended, immediately upon coming of age.

James Farndale (FAR00607) served

with the US Army. He joined up in 1917. He went to France. He left

the Army in 1919 and eventually became State Senator for Nevada.

James in Plymouth, Indiana

in 1917

S/294809 Private John Farndale (FAR00640) served

with the Army Service Corps and was awarded the Victory medal, British medal.

89289 Gunner John Joseph Farndale (FAR00581)

served with the Royal Garrison Artillery. He enlisted on 4 December 1915 and

was discharged on 14 December 1918.

38005 A/Corporal John W Farndale (FAR00698)

served with the Lincolnshire Regiment, then as 29415 in the Labour Corps and

was awarded the Victory Medal and the British War Medal. He was born in Guisborough 1899 and died in 1970.

26042 Private John W Farndale (FAR00653A)

served with the East Yorkshire Regiment, then as 570018 in the Labour Corps and

was awarded the Victory Medal and British War Medal.

L/28839 Driver John W Farndale (FAR00663)

served with the Royal Field Artillery and was awarded the Victory Medal and the

British War Medal. He was born in Malton in 1894 and died on 29 June 1954.

151907 Gunner John W Farndale (FAR00615)

served with the Royal Garrison Artillery and was awarded the Victory Medal

and the British War Medal. He was born in 1893 and died on 2 March 1973.

247529 T/Warrant Officer Class I Joseph

Farndale (FAR00593) served

with the Army Service Corps and was awarded the Victory Medal and British War

Medal.

016314 Private Joseph Farndale (FAR00675) served

with the Army Ordnance Corps and was awarded the Victory Medal and British War

Medal.

James

Farndale (FAR00521)

probably signed up immediately at the start of World War 1 and joined the Royal

Field Artillery, though I have not found records afterwards of his military

service.

3758 & 201065 Private Richard

Farndale (FAR00681)

aged 20 joined the 1/4th

Battalion The Yorkshire Regiment, the Princess of Wales’

Own Yorkshire Regiment, also known as the Green Howards. He died at 21st CCS in

France of broncho-pneumonia on 25th February 1917. He enlisted at Redcar, resident at Coatham.

The battalion served with the York and Durham Brigade of the Northumbrian

Division, renamed in 1915, the 150th Infantry brigade of the 50th Division. At

the time of his death the battalion was not in the line but in reserve at Proyart. On 31 December 1916 it was at Bazentin

le Petit and in reserve at Flers on 7 January 1917.

On 11 January the battalion moved to the front line at ‘Hexham Road.’ It was

again in the front line from 30 Jan to 11 Feb at Genercourt.

The battalion moved to Proyart on 19 Feb 1917. He was

awarded the British War Medal and the Victory Medal posthumously on 21 Jan

1921. He was presumably badly wounded at Hexham Road or Genercourt

or Proyart and evacuated to No 21 Casualty Clearing

Station at La Neuville, where he later died of pneumonia. He was the son of

George and Mary Farndale of 6, High Street, Coatham, Redcar Yorkshire. His name

is on a War Memorial at Coatham. He is buried at La Neuville Communal Cemetery,

Corbie, Somme .

44768 Private Robert Farndale (FAR00552) served

with the King’s Own Yorkshire Light Infantry, then as 426393 in the Labour

Corps, then as G/30179 in the Royal Sussex Regiment. He was awarded the British

War and Victory Medals.

Z/6840 Thomas Henry Farndale (FAR00699)

served in the Royal Navy Reserve in London in the first World War. He was a

telegraphist.

William Farndale (FAR00647)

served with the Canadian Army, 28th Saskatchuan

Regiment. He served in France where he was wounded from bayonet wounds. In 1918

he was back in Regina taking people to hospital when he contracted ‘flu from

which he died. William

Farndale, joined the

Canadian Army on 19 April 1916 at Regina, Saskatchewan and went to France. He

was wounded in action at Vimy Ridge

on 13 December 1916 while serving with the 28th Battalion; he had a gunshot

wound in the right forearm and was in hospital in Epsom, England. He was

discharged from the Army at Calgary on 18 Feb 1918. He was awarded the British

War Medal and the Victory Medal. After his return to Regina, he used his car to

evacuate the sick during the great ‘flu epidemic of 1918. He caught the ‘flu

while still weak from his wound and died at Earl Grey, Saskatchewan, Canada,

aged 25 years on 23 Nov 1918. He was buried in Earl Grey, Saskatchewan.

See also the For

King and Country website.

William Farndale of Tidkinhow

131820 Lance Corporal William Farndale (FAR00639), 25,

from Great Ayton, served in 235th

Army Troops Company, Royal Engineers. He achieved the rank of Lance Corporal,

Royal Engineers Class ‘P’ AR. He enlisted on 17 November 1915 and was

discharged on 30 December 1918. The cause of discharge was Para 392 (xvia)(Gas psng).

He was awarded the Victory Medal, British Medal and Silver Badge Roll 11

November 1919. The Silver War Badge was awarded to most servicemen and women

who were discharged from military service during the First World War, whether or not they had served overseas. Expiry of a normal

term of engagement did not count and the most common reason for award of the

badge was King’s Regulations Paragraph 392 (xvi), meaning they had been

released on account of being permanently physically unfit. This was as often a

result of sickness, disease or uncovered physical weakness and war wounds.

Soldiers discharged during the war because of disabilities they sustained after

they had served overseas in a theatre of operations (an area where there was

active fighting) could also receive a King’s Certificate. Entitlement to the

Silver War Badge did not necessarily entitle a man to the award of a King’s

Certificate, but those awarded a Certificate would have been entitled to the

Badge. The main purpose of the badge was to prevent men not in uniform and

without apparent disability being thought of as shirkers – it was evidence of

having presented for military service, if not necessarily serving for long.

27364 Private William Farndale served with the East

Yorkshire Regiment and was awarded the Victory Medal and the British War Medal.

15271 Private (later Corporal) William

Farndale (FAR00651)

served with the Yorkshire Regiment (Green Howards). He arrived in France on

27 August 1915. He was awarded the Victory Medal, British Medal, and 15 Star.

1813 and 475088

Private William Claude Farndale

(FAR00682)

served with the 1/2 East Anglian Area Field Ambulance

Company, Royal Army Medical Corps. He was attested on 16 September 1913 at

Norwich, aged 17 years and 2 months (in fact he was 16, so perhaps gave an

older age in order to enlist), a tinsmith at Barrow

Works. He lived at 19 Onley Street. There is a record on 7 May 1919 of his

bounty of £15, with £5 for present use and £10 to be issued subsequently as

laid down in the Army Order. His Medal

Records show he served in the Balkans and was awarded the Victory Medal and

British War Medal and 15 Star. He was demobilised on 3 August 1919.

12035 Private William H Farndale (FAR00655)

served with the Royal Army Medical Corps, then as 53270 in the Lancashire

Fusiliers. He arrived in France on 12 September 1915 and was awarded the

Victory Medal, British Medal, and 15 Star.

436

and 403261 Private William Jameson Farndale (FAR00677)

served with the Royal Army Medical Corps and was awarded the Victory Medal and

British War Medal.

Lieutenant Graham Price was the brother in

law of the Rev W E Farndale (FAR00576).

He went to Flanders in 1914 as a despatch rider. Towards the end of 1915 he

transferred to the Royal Flying Corps. He held the record in his squadron for

the number of air duels (fifteen) he had fought. He was also an artillery

observer over enemy lines. He was killed in action on 21 March 1916 when he

received a bullet in the heart in an air battle. See Lieutenant

Graham Price.

The Inter War Years

543695 Charles Farndale (FAR00738) was

born at Huttons Ambro and became a groom. He enlisted into the Royal Tanks

Corps on 9 May 1924. He attested at Winchester. He served with the 13/18th and

15th/19th Hussars in 1924 and 1925.

The West

Sussex County Times, 23 November 1934: ROYAL SUSSEX REGIMENT WIN

REPLAY. 4TH BATTALION QUEEN’S ROYAL REGIMENT 0; 4TH

BATTALION ROYAL SUSSEX REGIMENT 5 (Pte Farndale 4, Pte Burchell). The side

representing the 4th Battalion Royal Sussex Regiment was in splendid form on

Saturday when it defeated the 4th Battalion Queens Royal Regiment at Mitcham by

five goals to nil. It was a replayed match in the first round of the

Territorial Army Cup Competition. Play was fairly even

at the start but gradually the Royal Sussex began to assert themselves and they

showed a marked superiority. After 10 minutes, Birchell on the visitors left

wing, centred for Farndale to score. The Royal Sussex kept up the pressure and

again from Burchell’s centre Farndale headed in a lovely goal shortly after the

resumption. Standing started a movement which resulted in Burchall

racing forward and driving home number three. Farndale scored his third when he

gathered a nice centre from Fenner, and shot well out

of Salter’s reach. The Royal Sussex were well on top during the closing stages

and the home side's defence underwent a severe gruelling. Five minutes from

time Farndale beat Salter for possession and had no difficulty in putting in

the fifth goal. 4th battalion the Royal Sussex Regiment: Private Stanford,

Private Kent, Private Boxall, Private Lawrence, Corporal Ansell, Lance Corporal

Linfield, Sergeant Fencer, Lieutenant Woolcock, Private Farndale, Private

Standing and Private Burchall.

The Second World War

The outbreak of War

At 11am on 3 September 1939, Chamberlain, in a 5

minute broadcast on the Home Service, announced that as Hitler had failed

to respond to British demands to leave Poland, "this country is at war

with Germany". Chamberlain added that the failure to avert war was a

bitter personal blow, and that he didn't think he could have done any more.

There was an anticipation of air attack.

Following the Prime Minister's speech there were a series of announcements. All

places of entertainment were to close with immediate effect, and people were

discouraged from crowding together, unless it was to attend church. Details of

the air raid warning were also given and it was

emphasised that tube stations were not to be used as shelters. In London the

air raid sirens sounded only 8 minutes later, and many of those remaining,

including commentator John Snagge, donned tin helmets

and rushed to the roof of Broadcasting House to watch the bombs falling.

Sandbags appeared everywhere. Cities were blacked out. The paintings in the

National Gallery were moved to a mine in North Wales.

The Official evacuation plan, Operation

Pied Piper, was part of widespread evacuations totally 3.5M people.

Poland was lost. However

an immediate threat to Britain was a false alarm. Nazi bombers were still out

of range. The Allies had 3:1 superiority in manpower and 5:1 in artillery. The

Royal Navy was dominant at sea. The FAR were capable of precision bomining. Italy and Japan had not yet joined the war. In

time the US might join. The British and French population was 90M and GDP

$470M, the German-Austrian 76M and GDP £375M.

There was a perception that the French

Army and the BEF could repulse a westward attack on the Continent.

However Russia’s pact with Germany had upset

the calculations. Scandinavia was also an important strategic consideration,

particularly as a source of iron ore.

Phoney War

The early months were a period of

stalemate. The

Phoney War was an eight-month period at the start of World War 2 during

which there was only one limited military land operation on the Western Front,

when French troops invaded Germany's Saar district.

On 9 April 1940,

the Germans invaded Norway.

The Battle for France

On 10 May 1940 a

sudden German attack began on Holland, Belgium and France at 5.35am.

After criticism of Chamberlain for the

disastrous Norwegian campaign, Churchill became Prime Minister that afternoon.

Chamberlain remained Deputy Prime Minister and Lord Halifax remained Foreign

Secretary.

On 13 May 1940 Winston Churchill, in his first address as

Prime Minister, told

the House of Commons of the United Kingdom, "I have nothing to

offer you but blood, toil, tears, and sweat." He felt “that all my

past life had been but a preparation for this hour and for this trial.”

The German attack on France was in

desperation, Hitler fearing that he would lose a long war. The German army

thrust through the woods of the Ardennes, and used surprise and speed, gained

by tanks and aircraft, crossing the River Meuse on 13

May 1940.

By 15 May 1940,

7 armoured Panzer divisions were thrusting forward into France. The Allies,

trained for static warfare, could not stop the advance. The allied defensive

force ran out of ammunition and fuel. Most of the British army comprised raw

territorials. In the European theatre, Britain only had 14 hastily assembled

divisions, to 141 German, 104 French and 22 Belgian. A minor success by the

British at Arras

on 21 May 1940, was not enough. The French Prime Minister rang Churchill to

tell him they were defeated.

On 19 May 1940,

only a week in to the German offensive, the British

began a fighting withdrawal to Dunkirk. Churchill declared in his

radio broadcast: Today is Trinity Sunday. Centuries ago

words were written to be a call and a spur to the faithful servants of truth

and justice: Arm yourselves, and be ye men of valour, and be in readiness for

the conflict; for it is better for us to perish in battle than to look upon the

outrage of our nation and our altars. As the will of God is in Heaven, even so

let it be.

Hitler was also losing confidence,

worried about counter offensive and a pincer movement. Alarmed at the risks,

Hitler ordered a halt on 24 May 1940.

On 26 May 1940

the Dunkirk

evacuation, Operation Dynamo, began. It was organised by Admiral Bertram

Ramsay and his staff in Dover between 26 May and 3 June 1940. A broadcast appeal

was responded to by fishing boats, weekend sailors, lifeboats and by barges and

tugs from, the Port of London. The RAF lost 177 planes and shot down 244

Luftwaffe planes. Some 300,000 British and Allied troops were evacuated and

another 130,000 escaped later from ports still in French hands. However 54,000 vehicles, 2,500 artillery pieces and 68,0000

soldiers were lost.

On 4 June 1940,

Churchill gave his

defiant response, We shall fight on the beaches, we shall fight on the

landing grounds, we shall fight in the fields and in the streets, we shall

fight in the hills; we shall never surrender.

On 7 June 1940,

German panzer divisions pierced the French defensive line.

On 10 June 1940,

Mussolini declared war.

On 12 June 1940,

the French army began a general retreat.

On 14 June 1940 the

Germans reached Paris.

Churchill suggested to France that

Britain and France become a single Franco-British nation. The Anglophobic

deputy Prime Minister, Marshall Philippe Petain rejected the proposal as an

invitation to marry a corpse.

Talk of negotiations had ended in

Britain. On 16 June 1940 Churchill told the

cabinet that Britain was fighting for her life, and no chink should appear in

her armour.

On 17 June 1940 Petain

became Prime Minister and ordered fighting to stop.

On 18 June 1940

Churchill made his Finest

Hour speech. Let us therefore brace ourselves to our duties, and so bear

ourselves that if the British Empire and its Commonwealth last for a thousand

years, men will still say, 'This was their finest hour.'

Britain was left without European

allies.

Facing the threat

The British population soon grew used to

the new state of things. Evacuees drifted back home. People stopped carrying

their gas masks.

There were still those who called for

peace through appeasement. The problem however was that any such ambition

rested on assumptions that Hitler’s intentions were limited, whilst his central

aim remained racial conquest and the winning of vast living space. It was not

Hitler’s primary aim to destroy Britian, but he had a hatred of London and New

York as centres of ‘Jewish’ capitalism.

The polls showed that 75% of the

population wished to fight on.

People sought strong leadership. At this

point in the war in particular, Churchill’s leadership was an important factor.

He was a master of words, making 2,000 speeches during his lifetime. Attlee

later said Churchill’s main contribution to the war was talking about it. He

was satirised as Winstonocerous. The Chief of

the Imperial General Staff, General Brooke found working with him to be

unbearable; he didn’t know the detail and only got half the picture in his

mind. He led Britain into total war, without much thought, but with a single

purpose, to destroy Hitler’s ambitions.

Amongst the general population there was

a rush of marriages and 300,000 men and women volunteered for the reserve and

1.5M for the Auxiliary Fire Service, Air Raid Precautions (“ARP”) and the

Special Constabulary.

The Military Training Act 1939 had

required young men to undergo 6 months training.

The National

Service (Armed Forces) Act 1939 extended the obligation to all men between

18 and 41, with universal

registration of men and their occupations.

The threat to Britain was still very

real. The Germans were starting to plan an invasion of Britian, Operation

Sealion, scheduled for late September 1940. A Black Book had been prepared of

targets for arrest, the Germans having shown themselves capable of murdering

the elite in order to reduce the nation to slavery.

The already weak German navy had

suffered badly in the Norwegian invasion. The Luftwaffe had heavy losses in

France, but still had 750 long range bombers, 250 dive bombers and 750 fighters

to Britain’s circa 750 fighters. Britain had developed a system of control

stations integrating radars and spotters. However the

limited range of radar meant only a few minutes warning, which then took 4

minutes to reach RAF fighter stations, so fighters had to scramble into action

and start fighting even before the whole squadron was airborne.

The Battle of Britain

The Battle of Britain, the only decisive

battle fought entirely in the air, began in August 1940, which was a month of

intense daytime aerial combats.

On 20 August

1940 Churchill gave his famous speech,

echoing Shakespeare’s Henry V: The gratitude of every home in our Island, in

our Empire, and indeed throughout the world, except in the abodes of the

guilty, goes out to the British airmen who, undaunted by odds, unwearied in

their constant challenge and mortal danger, are turning the tide of the World

War by their prowess and by their devotion. Never in the field of human

conflict was so much owed by so many to so few.

On 5 September

1940 the German attack switched to cities, especially London, Birmingham

and Liverpool in the Blitz. On 7 September a large raid started fires across

the East End.

On 15 September

1940 German attacks on London were met by massed fighters in Battle of

Britain Day. It started to become clear that German air strength was not

sufficient to gain air superiority.

Between July and October

1940 the RAF lost 790 planes to the Luftwaffe 1,300.

The Germans switched to night attacks on

cities. By mid November the Luftwaffe had dropped

13,000 tons of high explosives and a million incendiaries on London.

What ended the Blitz was the diversion

of the Luftwaffe to Russia. Its effect on Britian’s economy had been limited,

and its attempted impact on morale was counter productive.

Across Europe resistance against German

aggression saw in Britain what had been seen in the Spanish Republicans – a

sense of cheerfully stoical defiance, a ‘mustn’t grumble’ attitude.

During the war 6,000 civilians were

killed, half in London. Only 4% of the population used the tube and most didn’t

use shelters. ARP wardens, policemen and firemen worke3d tirelessly. There were

very few psychological breakdowns, and involvement in important work was the

therapy. Suicides fell.

The global war

Britain was at war with Germany and

Italy and Japan was threatening on the other side of the world. Britain had the

resources and manpower of its empire, 2.5M in India, 500,000 in Africa, 1M in

Canada, 1M in Australia and 3000,000 in New Zealand.

Leaders across the world started to

judge and make calculations as to who might win. Vichy France and Franco’s

Spain contemplated joining the war on Germany’s side. Many disliked Jewish

settlement in Palestine and anti semitism attracted some Arab support. King

Farouk in Egypt faltered in June 1940 and the pro Nazi

nationalist Rashid Ali seized power in Iraq. There were moves towards self government in India. However

Britain’s continued fight denied the claim that Germany had won. Goebbels

concluded from a Commons debate in June 1941 that there was no sign of

weakness.

The Italian army was defeated in

Abyssinia and eastern Libya by smaller British forces between October 1940 and April 1941.

The Italian army invaded Greece

unsuccessfully in October 1940 but again in April 1941 with

German assistance.

Crete fell in May

1941.

The Germans came to the aid of their

Italian allies in north Africa by the dispatch of General Erwin Rommel (“the

Desert Fox”)’s Afrika Corps in February 1941.

However with no obvious way to defeat Britain,

Germany started to contemplate its Plan Z, to build a huge battle fleet and

long range bomber force by 1948, to attack US.

The War at Sea

The Atlantic routes to Canada and US

were the principal lifeline. The Mediterranean was the embattled route to north

Africa, the Suez canal, and the Arab oilfields. The

south Atlantic was important for imports of meat and grain from South America.

Meantime the Royal Navy attempted a blockade on Germany.

Germany was much weaker at sea than in

1914. In December 1939 the pocket battleship the Graf Spee was tricked

into scuttling itself in Montevideo harbour. The Bismark managed a six day sortie in May 1941 and Sank the Hood, but was

damaged by the Prince of Wales. The German navy largely lurked away in

Norwegian fjords. It was also constrained by a lack of fuel. It could still

wreak havoc though – in July 1942 the codebreakers revealed that the Tirpitz

was about to go to sea, and the targeted convoy was ordered to scatter, but was

then picked off by aircraft and submarines.

In the Mediterranean, Italy’s most

effective military force was its navy. It suffered significant losses in the Battle of Taranto

on 11 to 12 November 1940. The Mediterranean was

bitterly contested at sea and in the air until 1943. The exposed Royal Navy

outpost of Malta was constantly attacked, with 75% damage to the houses of

Valetta, uniquely awarded the George Cross for he

whole island in April 1942.

The peak of losses in the Atlantic was

between June 1940 to March 1941, when over a million tons of British shipping

was sunk. Perhaps 9,000 convoys were escorted using the global convoy system.

Wolf packs of several dozen U boats attacked them. However

Germany struggled to maintain its submarine campaign. The biggest difficulty

for Britain was protection in the 600 mile Atlantic

Gap, the mid ocean area which was beyond air cover.

On 19 August

1942 a largely Canadian raid on Dieppe brought the Allies briefly onto

French soil.

By summer 1943 the

Battle of the Atlantic had ben won. The mastermind was Admiral Sir Max Horton

who trained support groups of anti submarine ships

and aircraft carriers coordinated by long range shore based

patrol aircraft.

Breaking codes

The Germans used the encoding machine

Enigma developed in Germany in 1923. The Polish intelligence service had begun

to succeed n breaking its code in the early 1930s and shared its work with

France and Britain. The British continued the work at Bletchley Park and began

to decipher messages by April to May 1940. The Bletchley staff, often academics

and students, increased its staff from 150 in 1939 to 3,500 in 1942 and 9,000

in 1945. Prominent members of the team were Max Newman and Alan Turing.

The deciphering system was codenamed Ultra, and used new computer technology and native cunning.

Great care was taken to conceal its successes from the enemy. An important

driver of the work was the use of regular phrases, such as Heil Hitler. Daring

actions allowed the recovery if lists of Enigma key settings, including a

daring recovery from a sinking submarine on 30 October 1942.

War in the East up to 1943

By July 1940 Hitler started to consider

an attack on his accomplice, Russia, a target for living space, lebenstraum, and conceived to be strategically

advantageous as the elimination of Russia would free up Japan’s power in the

Far East, then America would be diverted to war with Japan.

Stalin had taken advantage of his pact

with Hitler to invade Poland, Estonia, Lithuania, Latvia, Finland and Romania.

On 22 June 1941,

Germany attacked Russia, Operation Barbarossa, who were taken by surprise and

quickly defeated, but recovered to temporarily stop the German advance in December 1941.

On 7 December

1941 Japan launched simultaneous strikes on the American naval base at

Pearl Harbour in Hawaii and against British colonies.

On 8 December

1941 the Japanese attacked the Philippines, Malaya and Hong Kong.

The battleship Prince of Wales

and Battlecruiser Repulse were sent to disrupt Japanese landings on the

cost of Malaya but were sunk on 10 December 1941.

The Japanese marched into Malaya with ruthless efficiency.

The Japanese occupied Hong Kong on 25

December 1941, in a spree of rape and killing.

Churchill survived a vote of no

confidence in the Commons in January 1942.

The Japanese Empire captured the British

stronghold of Singapore, with fighting lasting from 8

to 15 February 1942. At the outset, the headmaster of Raffles school

asked what his boys saw and Lee Kuan Yew, later first president of an

independent Singapore replied, “the end of the British Empire”.

Singapore was the foremost British military base and economic port in

South–East Asia and had been of great importance to British interwar defence

strategy. The capture of Singapore resulted in the largest British surrender in

its history.

The Japanese had taken Hong Kong,

Malaya, Singapore, Burma, and North Borneo for the loss of 5,000 soldiers.

However on 4 June 1942 the

Americans caught a Japanese fleet at Midway and sank four aircraft carriers.

In summer 1942,

Gandhi and the Congress Party called for a huge campaign of civil disobedience

in its Quit India movement.

Famine in Bengal in the summer of 1943

was exacerbated by world food shortages and later mitigated by an improved

harvest and a drive by the new viceroy, Field Marshall Viscount Wavell.

In January 1943,

the Germans faced their first disaster on the eastern front when the survivors

of the German 6th Army surrendered at Stalingrad.

War in North Africa and

Italy

In Libya, Rommel’s forces tipped the

balance when they took the key port of Tobruk in June

1942.

However the Axis forces in North Africa were