Act 14

Spreading out from Brotton and Loftus

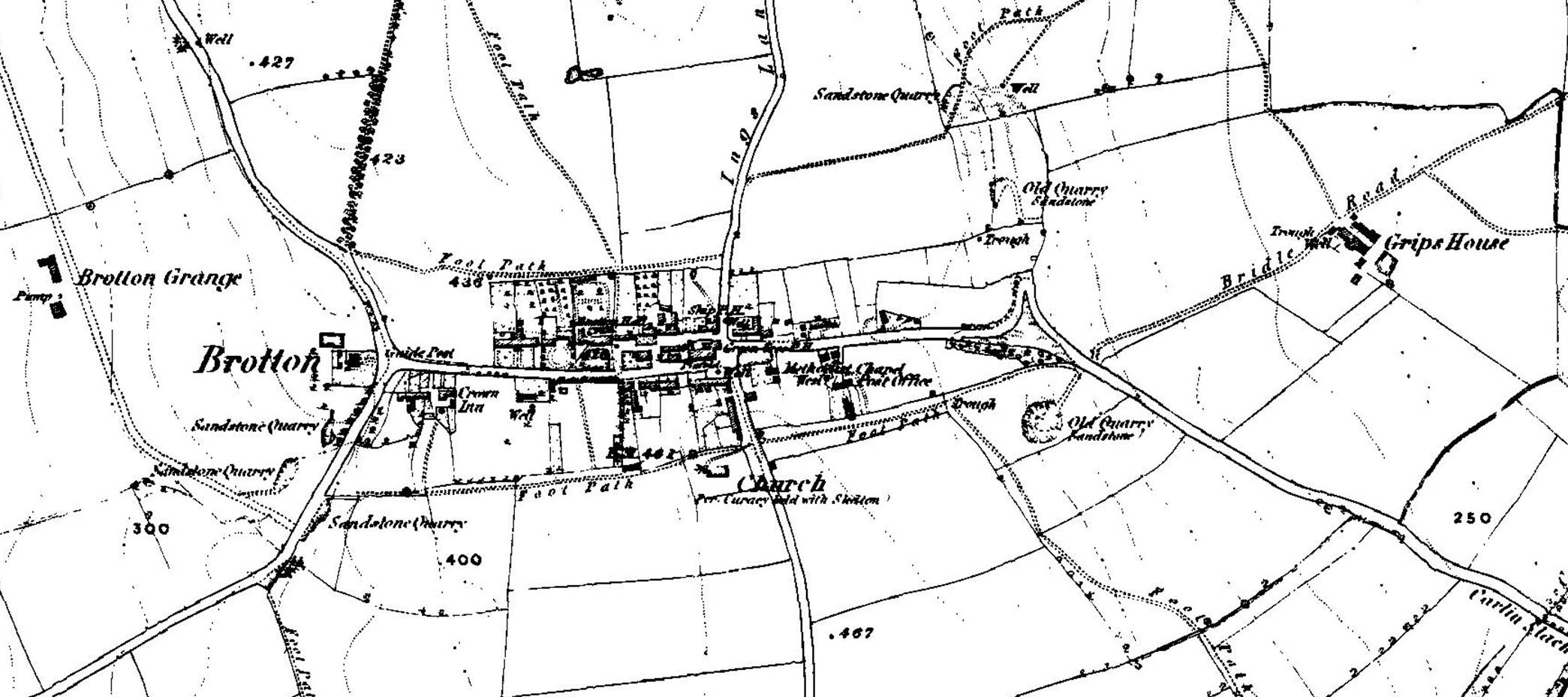

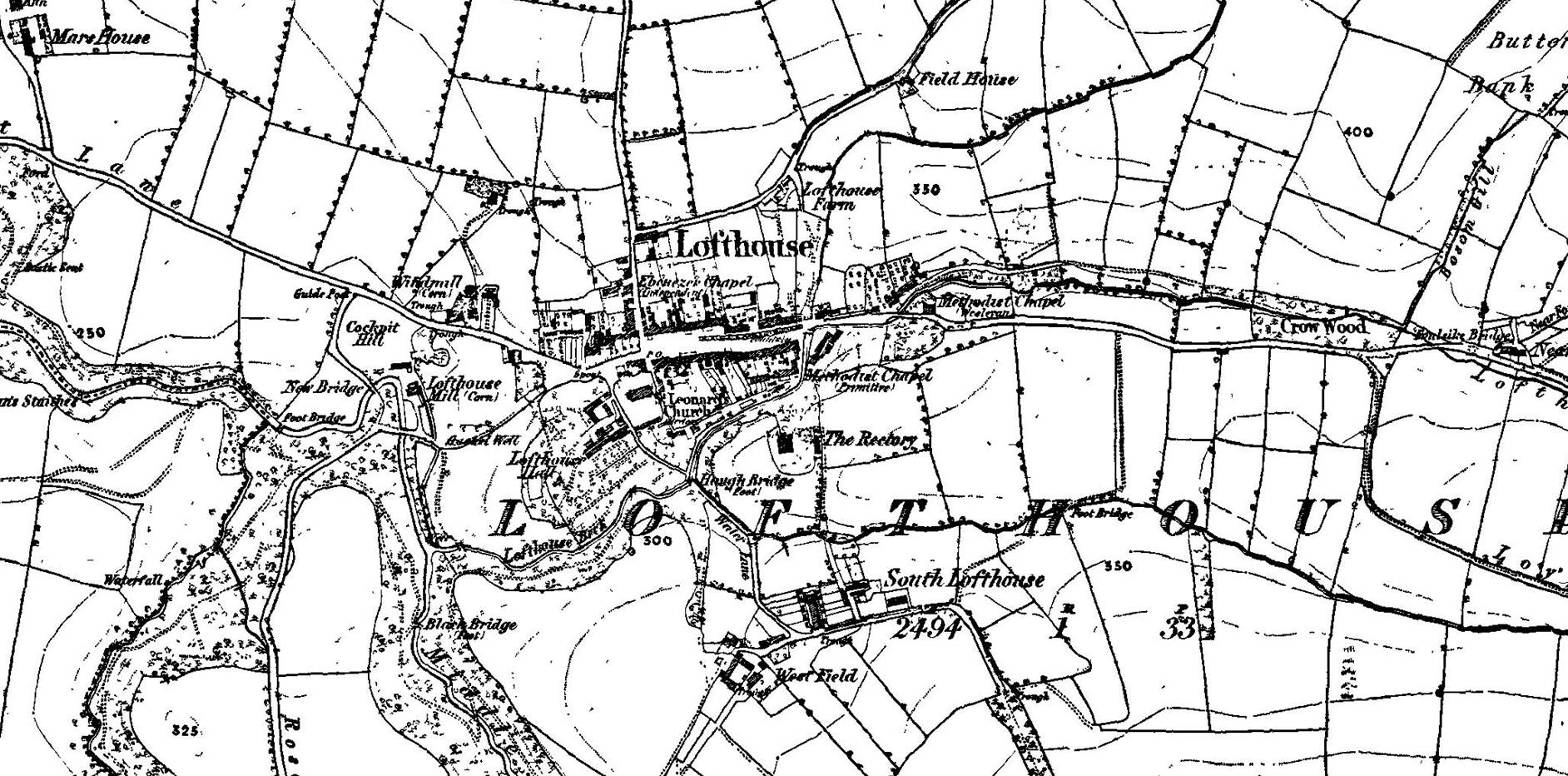

Brotton and Loftus in about 1850

The story of a second large family

whose heart was around Brotton and Loftus and comprise another substantial

division of the family

|

This

is a new experiment. Using Google’s Notebook LM, listen to an AI powered

podcast summarising this page. This should only be treated as an

introduction, and the AI generation sometimes gets the nuance a bit wrong.

However it does provide an introduction to the themes of this page, which are

dealt with in more depth below. The

AI chat wrongly concludes that John Farndale’s works have been lost. We will

explore them elsewhere on this website. |

|

The Stockton to Darlington Railway

A

quick introduction to the Stockton to Darlington Railway, a backdrop to this

section of our family history. |

We now meet

the second Hub of the family. This was another large section of the family who

initially also made Kilton their home for a

generation as the Kilton 2 Line,

before dispersing across Cleveland and beyond. They are a little more difficult

to define geographically as they dispersed widely. However the heart of the

family was Loftus, also once known as

Lofthouse, two kilometres east of Kilton,

and Brotton, two kilometres north of Kilton. So this family were living in close

proximity to their relatives of the

Kilton 1 Line, who we met in the last Act.

This was a

family who left the protection of the rural extended family, and struggled for

survival in Georgian and Victorian Britain. Their resilience against the odds

is sometimes inspiring, often tragic, and reflects the challenges of Victorian

Britain. Some made successful lives for themselves, but many suffered,

particularly during the terrible decade of the 1870s, the decennium

horribilis.

From 1873 to

1896, a period sometimes referred to as the Long Depression, most European

countries experienced a drastic fall in prices. This was a period of two

decades of stagnation, and this family suffered the worst of these years of

agricultural and economic struggle.

The stories

of struggle, alongside achievements against the odds, reveals a quiet

determination by this stoic branch of the family.

When

sorrows come, they come not single spies, but in battalions.

(Hamlet, Act

IV, Scene V)

Scene 1 – The Loftus Farndales

William Farndale

(1690 to 1782) was the son of George and Ellis

Farndale of Liverton and Loftus. We met George in Act 12 and you might remember

that he was fined for letting his horse graze on the Common at North Loftus in 1700.

William was

born in Liverton and baptised there on 23

November 1690. He was a church warden at Skelton in 1729 and in 1738 he

married Mary Butterwick of Brotton. He

seems to have lived in Kilton, and they

had five children who were baptised at Skelton church, but were

probably born in Kilton which lay within

the Skelton estate. He died

in 1782 and was buried at Brotton.

William and Mary

had five children. The youngest was John Farndale who

worked in Ormesby now in Middlesbrough

and later took property with his brother, William, in Loftus. William Farndale The Younger

(1739 to 1813) was the older brother, baptised in Skelton on 3 January 1739. William married

Hannah Toes of Lythe in 1761, where they

lived until about 1765 before they moved to Loftus.

Loftus was the family home of William’s

grandparents, George

and Ellis Farndale, so this probably felt like moving back to the paternal

family home. William seems to have quickly established himself in Loftus and in 1781 at this Court Leet

William Farndale was elected and sworn as Constable for the year for South and

North Loftus.

Law

enforcement and policing before the eighteenth century were not administrated

nationally, but organised by local communities such as town authorities. Within

local areas, a constable could be attested by two or more Justices of the

Peace. From the 1730s, local improvement Acts made by town authorities often

included provision for paid watchmen or constables to patrol towns at night,

while rural areas had to rely on more informal arrangements. In 1737, an Act of

Parliament was passed for better regulating the Night Watch of the City

of London which specified the number of paid constables that should be on duty

each night. Henry Fielding established the Bow Street Runners in 1749 and

between 1754 and 1780, Sir John Fielding reorganised Bow Street like a police

station, with a team of efficient, paid constables. Parish constables, played a

variety of roles, and in more populated areas could make a reasonable living

from fees. They were professional, competent, and entrepreneurial. They were

regulated to some extent by systems of legal incentives and warnings. The main

form of oversight on them, and limit on their power, was the possibility that

they might be subject to a lawsuit. Watchmen in towns were waged, with less

legal power than constables, and subject to more supervision, including periods

of definite duty.

By 1784, William Farndale

The Younger was a freeholder and tenant of property in South Loftus. Hannah died in 1801 and William The Younger

lived until the age of 75 and was buried in Loftus

on 19 June 1813.

William Farndale

The Younger and Hannah had a family of five, the Loftus 1 Line.

Their

youngest son was John

Farndale (1772 to 1842). John married Jane Pybus at Skelton in 1794 and they in

turn had a family of eight, the

Brotton 3 Line, all baptised in Brotton. John and Jane’s family might have lived in Brotton itself, or might have lived in the

associated township of Kilton. John was a

farmer, and his son George Farndale

was also a farmer, and he certainly farmed in Kilton.

Of John’s

family of eight, Jane

Farndale and Mary

Farndale seem to have died in infancy. Hannah Farndale

suffered a rape in 1819 when she was only 14 years old at Brotton, but in 1825 she married Francis

Cooper. Then almost 20 years later, presumably after Francis had died, in 1843

she married a farmer, George Ventress, with whom she had three children. Mary Ann

Farndale married a cartwright called John Porritt of Moorsholm.

It is the

stories of the other four siblings, who we now follow.

Scene 2 – A Stockton Family

John Farndale (1796 to 1868) was the eldest son of John and Jane Farndale

born on 16 March 1796 in Brotton. He

married Elizabeth Wallace in 1827 and worked for a while on farms at Kildale

near Great Ayton before he became a Yeoman Farmer in Skelton. In 1830 a Bill of

indictment for felony was issued against Hannah Bradley and Jane Mark both

single women, lately of the House of Correction at Northallerton, for stealing

three pecks of wheat value 3s, the property of John Farndale. The offence was

committed at the parish of Skelton on 6 October 1830.

In 1831, a

certain Masterman Patto appointed John Farndale and

William Hugill to act as trustees and executors to resolve the division of

Masterman Patto’s farm between his daughters after he died. The somewhat

complex arrangements suggest that John Farndale was

respected in the local community in Skelton. However he seems to

have then worked on an off as a farmer and farm worker particularly around Coatham.

However,

twenty years later in 1851, John seems to have lost his farm and was working as

a farm labourer, having suffered bankruptcy. By 1861 the family had moved to Stockton, where John was working

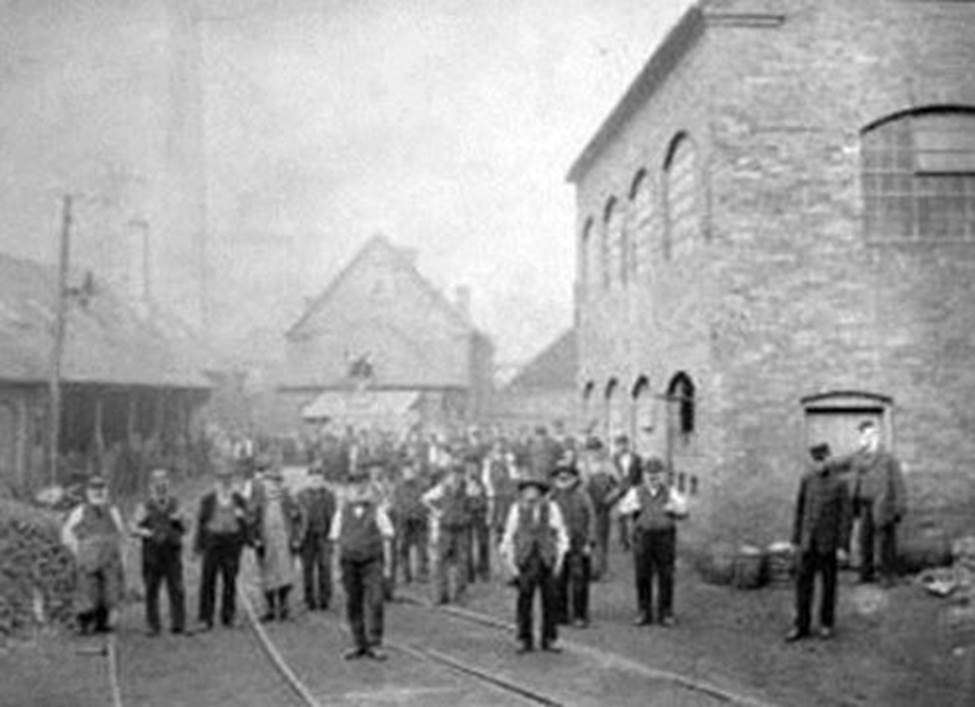

in the iron foundry.

Iron

Foundry, Stockton

John died in Stockton in 1868.

John and Elizabeth Farndale had a large family of ten children, the Stockton 1 Line, who made Stockton their home. This was a time of

momentous change in Stockton. In 1822, Stockton witnessed an event which heralded the dawn of a new era in industry and

travel. The first rail of George Stephenson's Stockton and Darlington Railway

(“S&DR”) was laid near St John's crossing on Bridge Road. Hauled by

Locomotion No 1, the great engineer himself manned the engine on its first

journey on 27 September 1825. The S&DR operated from 1825 to 1863.

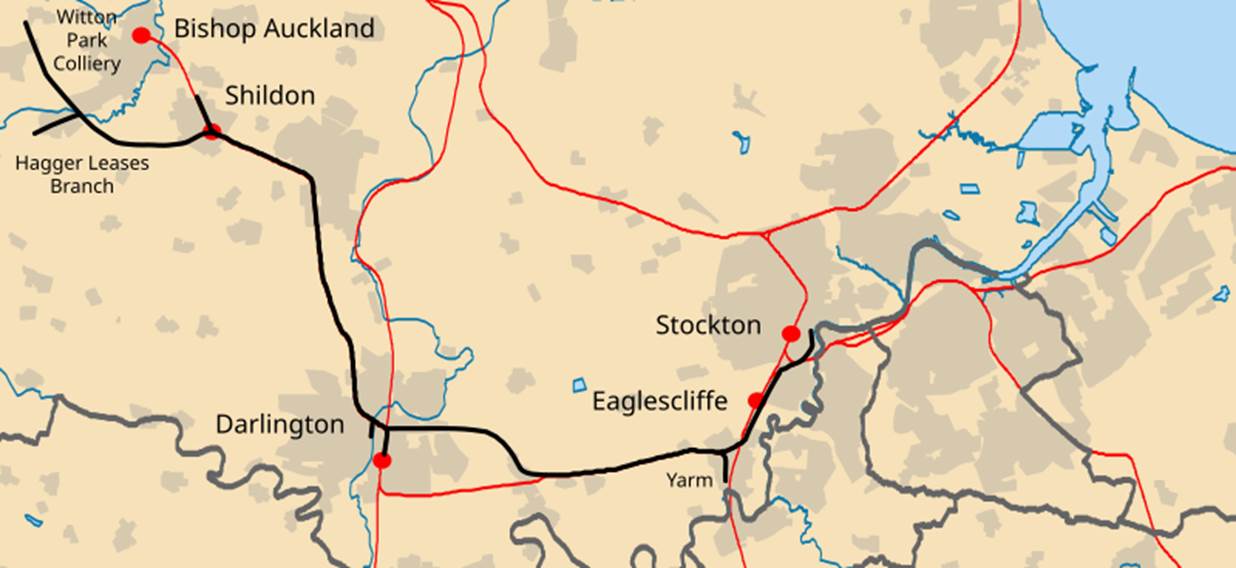

The route of the Stockton &

Darlington Railway in 1827, shown in black, with today's railway lines shown in

red

John

and Elizabeth Farndale’s eldest son was John Farndale

(1829 to 1899) who became a grocery warehouseman in Stockton. After his first wife Ann Thrattles died he married his sister in law, Ellen Thrattles in 1873. John and Ann had five children.

Their second

son was George

Farndale (1835 to 1887) who became a druggist and grocer in Stockton. George married Catherine Wemyss Leng at Stockton in 1865. In 1873 George, like his

father, was forced to petition for bankruptcy and his chemist, druggist and

grocery business went into liquidation. In 1875 George served on

a jury in Northallerton, by which time he had restarted a chemist business.

However he seems to have been made bankrupt again in 1878.

In 1850, in The

Personal History and Experience of David Copperfield the Younger, Charles

Dickens, reflected on the hardships of Victorian bankruptcy. Mr Micawber was

waiting for me within the gate, and he went up to his room (top storey but

one), and cried very much. He solemnly conjured me, I remember, to take warning

of his fate; and to observe that if a man had twenty pounds a year for his

income, and spent nineteen pounds nineteen shillings and sixpence, he would be

happy, but that if he spent twenty pounds one, he would be miserable.

In his

autobiography, From

Crow Scaring to Westminster, the Methodist George Edwards described the

challenges of mid Victorian Britain. It was in the year 1855 when I had my

first experience of real distress. On my father's return home from work one

night he was stopped by a policeman who searched his bag and took from it five

turnips, which he was taking home to make his children an evening meal. There

was no bread in the house. His wife and children were waiting for him to come

home, but he was not allowed to do so. He was arrested, taken before the

magistrates next day, and committed to prison for fourteen days' hard labour

for the crime of attempting to feed his children ! The experience of that night

I shall never forget. The next morning we were taken into the workhouse, where

we were kept all the winter. Although only five years old, I was not allowed to

be with my mother. On my father's release from prison he, of course, had also

to come into the workhouse. Being branded as a thief, no farmer would employ

him. But was he a thief ? I say no, and a thousand times no ! A nation that

would not allow my father sufficient income to feed his children was

responsible for any breach of the law he might have committed. In the spring my

father took us all out of the workhouse and we went back to our home. My father

obtained work at brickmaking in the little village of Alby, about seven miles

from Marsham. He was away from home all the week, and the pay for his work was

4s per thousand bricks made, and he had to turn the clay with which the bricks were made

three times. He was, however, by the assistance of one of my brothers, able to

bring home to my mother about 13s per week, which appeared almost a godsend. In

the villages during the war hand-loom weaving was brought to a standstill, and

thus my mother was unable to add to the family income by her own industry.

George and

Catherine suffered further tragedy when their three daughters, Mary Frances

Farndale, Catherine

Wiley Farndale, and Annie Louisa

Farndale, all died aged 7, 4 and 3 within nine days of each other at

Christmas, between 17 and 26 December 1874. There was a smallpox pandemic in

1870 to 1874, which originated in France. The Vaccination

Act 1853 helped to mitigate its effect in England, but perhaps this was the

cause of three sisters dying in the same year. There was also a cholera

epidemic at the time. This was also at the time when George’s grocery

business was struggling. When the last of the three girls died in such short

succession, an unspeakably sad notice on 2 January 1875 seemed to summarise the

ill fortune that the family had met, Death on the 26th Dec, at

Newport Road, Middlesbrough, Annie Louisa, aged three years, the beloved and

last surviving daughter of Mr Geo Farndale. The 1870s was the Stockton

Farndales decennium horribilis.

However, out

of these tragic circumstances, the younger brother, William Leng

Farndale, survived, and he has a story to tell, which we will pick up

again.

After his

second bankruptcy, George

and Catherine moved to 22 Great Oxford Street, Liverpool, where he was a

druggist’s assistant, lodging with a Russian and German family of tailors. He

died aged 52 in Gateshead.

The youngest

sons of John and

Elizabeth Farndale were William Farndale

and Peter Farndale,

who both became solicitors’ and court clerks in Stockton.

Both brothers took active roles in legal proceedings in the Stockton courts during the second half of the

nineteenth century.

Peter Farndale

regularly helped to clarify the law on various matters. For instance on 18 May

1878 a case of threat and assault came before the court when there was a

complaint about the milk being short, and the female accused had replied

to her complainant that she wanted none of her nonsense. Further altercation

ensued and Mrs Oliver ejected the female from the cow byer. She quickly

returned and said that if she did it again she would smash her face, and to a

certain extent carried out that threat by doubling her hand into prosecutrix’s

face. Mrs Oliver also called the defendant a “wizen faced old devil”. The male

prisoner, having heard the disturbance went towards them and told his wife that

if she didn't smash prosecutrix’s face he would smash hers. He told his wife to

“pull the cat and croker.” The accused gave

evidence that she knew nothing about watering the milk that was to be sent

to the Union, as the doctor would not allow it. She might have used the words

“wizen faced old devil”, but not a stronger expression. John Finlowe, a lad who said he was groom; George Barker, the

milk boy; John Kilgore, another boy; and the manservant, Stephen Davey, all

spoke to Mrs Oliver putting the female prisoner out of the byer, and then the

latter threatening her if she did that again. Mr Hutchinson, the

magistrate, said the question of the water had not come out in evidence. Mr

Draper replied that he could produce the girl who would prove it. Mr

Farndale, the deputy clerk, said the prisoner could not call witnesses in a

case of this nature. The female prisoner was then discharged, and her

husband bound over to keep the peace for two months, himself in £10, and one

surety in £5. Mr Hutchinson observing as he left the bench that he did not

think all the evidence had come out. There had been some intimidation amongst

the boys. Mr Draper denied anything of the kind on his on the part of his

clients.

Peter was not

shy of directly enforcing the peace in Stockton. On Tuesday 15 October 1878 an

Irishman named Samuel O'Neill was brought before the Stockton Borough Bench

today (Tuesday) on a warrant charging him with having been drunk and disorderly

in the street, and also with having committed an aggravated assault upon his

paramour, Jane Johnson. It appears that the prisoner brutally ill treated the woman a few days ago, and pawned a quantity

of her clothing to supply himself with drink. On Monday morning he continued to

threaten to take the woman's life, and the woman in consequence went to the

police court and requested the magistrate to grant a warrant for the prisoner’s

apprehension. The bench told the woman to go to the office of the magistrates

clerk in Finkle Street. This she did; But whilst there, the prisoner entered

the office brandishing a knife and threatening to murder her. Mr Jennings, the

deputy magistrates clerk, and Mr Farndale, one of the clerks, immediately

seized the infuriated man and prevented him carrying out his rash intention.

Inspector Caisely and Police constable Grey were then

called in, and after handcuffing the prisoner they took him to the police

station.

A few days

later on 18 October 1878, at Stockton Police Court, a dejected looking

female named Mary Hayward, a tramp, was committed to Durham Gaol for 14 days

for being found secreted in the office of the town clerk for an unlawful

purpose. Prisoner was found by Mrs Sanderson, the office keeper, sitting behind

a corner in the passage leading into the offices. She informed Mr Farndale

that she had had a drop of drink, but meant no harm. When people got drunk

they went into strange places. She just went there to smoke her pipe.

In September

1879, a man named David Porter, living in Bowser Street, was charged with a

breach of the peace. When asked if he had any defence he at once commenced a

long speech, telling the magistrates clerk, Mr Farndale, not to interrupt,

and when the bench seemed impatient adjured them with “don't be so fast, your

honours.” He then went on to say he had been 16 years in the town, was a

ratepayer, and had never done any wrong except perhaps taking a glass of drink

and being rather noisy etc. The bench cut him short with the inevitable 5s and

5s 6d costs, or 14 days.

Peter’s older brother George had suffered by the death of his three girls in 1874 during the smallpox

pandemic in 1870 to 1874, which originated in France and Peter may well have had little time for those who refused to be vaccinated.

The Vaccination Act 1853 which had prevented many deaths, was nevertheless controversial and

there was a strong anti-vaccination

movement in late Victorian Britain.

On 22 June

1891, an ironworker alleged a double marriage on the part of his wife after his

wife complained in court that her husband had stayed out several nights last

week, and she had not seen him since Friday. There had been nothing but trouble

since defendant had commenced to go down to the betting ring on the quayside.

He wanted to pull a ring from her finger to pledge it to bet. The accused

ironworker seems to have counter attacked his wife when he alleged she had

been married before. Her first husband’s name was Jas Fawcett. She could not

swear he was dead, but seven years ago she was told by a friend who saw him in

America he was living with another woman and had a family. She afterwards heard

he was dead. She was married to defendant in November 1888. Mr Thomas applied

that only an order should be made on defendant to contribute to the child, the

parentage of which he admitted. Mr Farndale the clerk, said there was only a

statement but no actual proof as to bigamy, and accordingly the bench

ordered defendants to pay 7s to complainant.

A special

meeting of the Stockton police court was held on 22 March 1892 to investigate charges of shop

breaking against several young fellows who supposed recent escapades have

created quite a sensation of alarm in the town. Evidence was given that

when he came into the police station the accused said “I don't know anything

about these tools.” Elsey: “Might I say a few words gentlemen? I believe he has

been in the habit of reading “the Boys of London” and the “Detective” week by

week. You might be as lenient as you can on account of my wife.” Mr

Farndale, the assistant clerk: “you had better not say anything”. Anderson, in

reply to Mr Farndale’s query as to whether he wished to ask any questions,

said: “He, witness, says we took a box of chocolate, but we never took any”.

William and Peter Farndale

were clearly at the centre of the colourful tales of Victorian Stockton.

When Peter died in

June 1895, his obituary read To a very wide circle, especially in the legal

profession, the intelligence we now record of the death of Mr P Farndale, or 52

Hartington Road, Stockton, will be startlingly sad information. Mr Farndale was

a native of the Coatham district, but since his boyhood had been in the offices

of Mr Faber and Messrs Faber, Fawcett and Faber. His special department, which

he held for over 20 years, was that of clerk to the present Mr Faber, and also

his father, in connection with their clerkships to the Stockton borough and

county justices. He was a gentleman with wide and accurate knowledge of

criminal law and general police court work. Reticent by nature, he was

nevertheless both courteous and obliging and imparting his knowledge to those

whose duties brought them in contact with him. Most regular and methodic in his habits, he was thoroughly reliable and

correspondingly respected. Last Friday, in pursuit of his duties, he had

occasion to visit Port Clarence, where he caught a chill, but no serious

consequences were apprehended, for both on Saturday and on Monday morning he

went to his duties as usual. About ten o’clock, however, on Monday morning,

after he had made his usual preparations for attending the petty sessions, he

complained and went home. He became worse, the attack resolving itself into one

of diphtheria, and on Tuesday afternoon he succumbed shortly after undergoing

the operation of tracheotomy. He had no children, but leaves a widow, who was a

member of the well known family of Devereux, of

Stockton, and with whom much sympathy is felt.

John Farndale,

the author, of the Kilton 1 Line

was also at the heart of colourful Victorian Stockton.

|

1791 to 1878

The Author A man of sphinxian complexity who wrote extensively and has passed

down stories of the family and of change in early Victorian Yorkshire |

The family

witnessed Stockton, at the peak of its

Victorian influence, suffering its Victorian trials, but also participating in

its excitement.

Scene 3 – the Struggles of the Family

of Ladgates Farm

William Farndale

(1801 to 1876) was the third child of John and Jane Farndale,

born at Craggs House, Brotton, on

9 August 1801. He married a lass from Hartlepool

called Jane Scott on 31 May 1841 at the Chapelry at Brotton. He lived next door to his brother, Robert Farndale,

who was the Brotton grocer.

Ten years

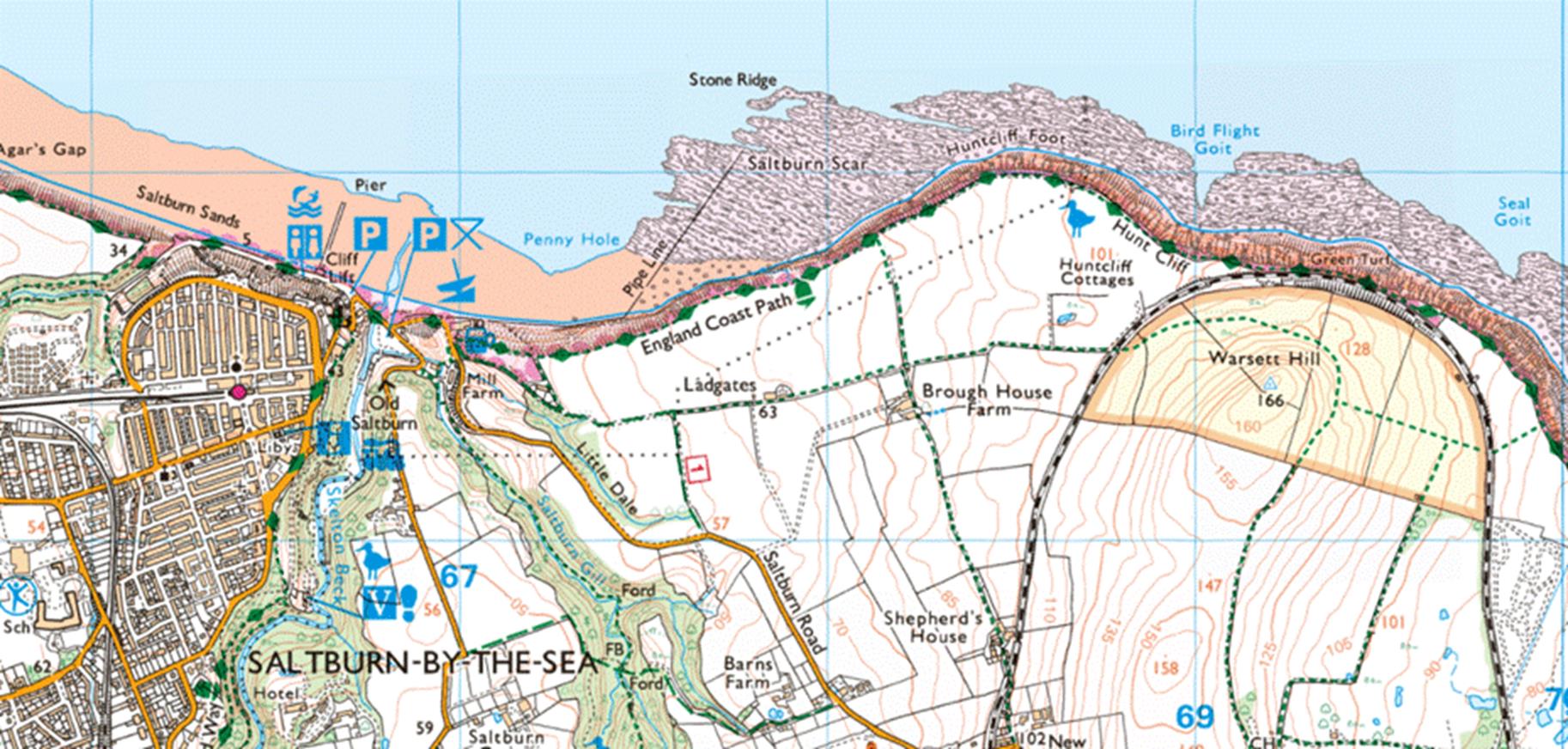

later by 1851, he was a farmer at a small coastal farm of 35 acres, a kilometre

to the east of Old Saltburn, called Ladgates.

William was a

tenant at Ladgates Farm when it was sold at auction

by its owner, a gentleman, in 1860. The life interest of a gentleman,

aged 40, was sold in August 1860 including Ladgate

Farm and premises, at Brotton aforesaid, containing 100 A, 2 R 26 P, of the

annual value of £30, in the occupation of William Farndale. It comprised a

farm house and outbuildings, and about 35 Acres of Arable, Meadow, and Pasture

Ground adjoining.

It appears

that there was a reservation for ironstone and minerals and a railway from Brotton to join the Middlesbrough and Guisborough Railway was intended to pass

close to the farm leased by William Farndale.

The Vendors reserve the right to themselves of working and taking away

ironstone and other minerals, upon the whole or any part of the Premises, and

the right of making Tramways and other Roads for taking and carrying away the

same, but they will pay the purchaser of any Lot any surface or other damage he

may sustain thereby. A railway is in the course of formation from Brotton to

join the Middlesbrough and Guisborough railway at Guisborough, and is intended

to pass over or close to the farms in the occupation of Henry Elot and William Farndale. Another Railway is about to be

formed, to join the North Yorkshire and Cleveland railway, at Ingleby, with the

Middlesbrough and Guisborough railway, at or near to the Nunthorpe station,

which will pass through the Wood Land and Premises at Easby.

The railway

craze had reached the Saltburn

coast by 1860.

William and Jane

Farndale had three daughters, Mary Jane

Farndale, Hannah

Farndale and Sarah

Ann Farndale. All three married, but all three, with their children, lived

with their parents in Marske by 1871.

By 1873, William was

working in Saltburn

when he raised a complaint against an engine fitter, for obtaining by false

pretensions the sum of 10s from William Farndale, of Saltburn, labourer.

The defrauder was imprisoned for a month after he gained possession of 10s

from Mrs Farndale on the representation, which was untrue, that he had been

sent for the money by her son in law, Richard Agar, a drainer of Saltburn.

William died on

20 February 1876 in Saltburn,

by which time he had been working as a cartman. Later that year his wife Jane

seems to have started a grocery business, which went into liquidation. All three of the girls had died young in

their late twenties in the early 1870s, and left their own children to be

brought up by their now widowed grandmother, who struggled to keep her family

afloat by working as a laundress.

The 1870s

was also the Saltburn Farndales’ decennium horribilis.

Jane

Farndale, who clearly struggled against the odds to see her four grandchildren,

Eva Appleby, Fenna and Sarah Agar, and Lily Purdy into adulthood, lived until 2

January 1900 when she was buried at Saltburn.

William and Jane Farndale also had a son, William George Farndale, who married but by 1908 was struggling when William George Farndale,

a labourer, of no fixed abode, was on Tuesday at Guisborough fined 21s, with

the alternative of a month’s imprisonment for obtaining food and lodgings by

false pretences from Catherine Cogan, of West Dyke, Redcar. The evidence showed

that he obtained board and lodgings by representing that he was employed by Mr

F Senior in asphalting in connection with the new school at Redcar. He came to

her house on March 28th, and Mr Senior was today called to prove that he left

his service on March 21st, and that he had no authority to say that he was

working for him at Redcar schools. Inspector Hall stated that when Farndale was

charged with false pretences he replied, “It is alright, she will be paid.”

Superintendent Rose said the defendant was a joiner by trade, and a native of

East Cleveland, but he had lived a roaming life. However by 1911, he was

working as a butcher in Marske, but he died aged 57 in 1915 in the workhouse at

Guisborough.

For all of John Farndale’s enthusiasm at the ambition of the new Victorian seaside town, life was

not easy at Saltburn.

Scene 4 – The Farmer of Kilton

George Farndale (1807 to

1847) was the fifth child of John and Jane Farndale

baptised on 15 March 1807 at Brotton. He

became a farmer in the parish of Brotton,

where he married Ann Child, a widow, and sister of George Ventress, who had

married George’s older sister, Hannah Farndale.

His farm was

in Kilton, that generational hub of the

Farndale family, where the family lived at Sykes House. So George had moved

back into the fold of the rural extended family, which seems to have been a

better place to weather the storms of the later Victorian period.

He died in

1847 when he was only 40, but his determined widow, Ann Farndale, took on the Kilton farm where she ran the farm business

with three employees.

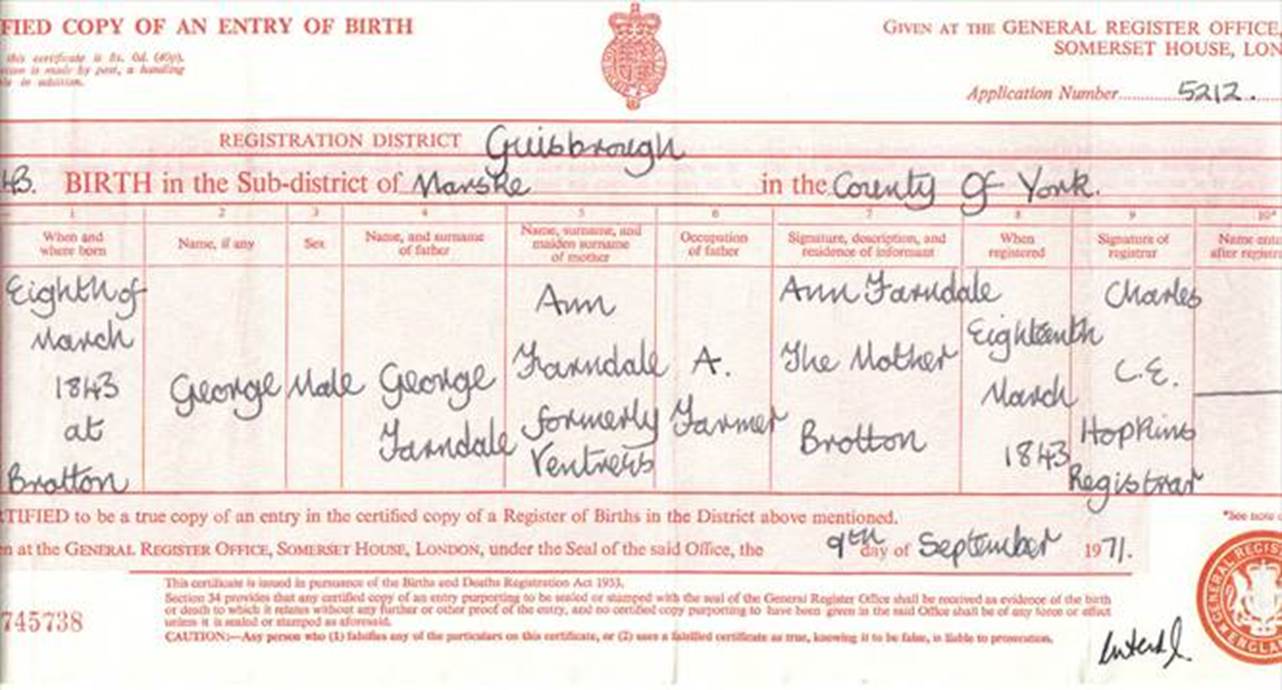

George and Ann

Farndale had one child, a son, George Farndale

(1843 to 1917), born on 8 March 1843 and baptised on 12 March 1843 in Brotton.

By the age

of 18, in 1861, George was still at Kilton and took work with the millers of Kilton mill, John and Eliza Child. In 1867 he

married Hannah Mary Walker, the daughter of a blacksmith at Loftus, and by 1871, George was

working as a blacksmith himself at 54 Lambs Lane, Liverton. By 1875, George was working as an ironstone miner.

George was

clearly a person of artistic talent and in August 1883, he exhibited in the eighth

annual exhibition of the Horticultural and Industrial Society run by the

Skinningrove Miner’s Association. The exhibition took place in a field

pleasantly situated within half a mile at the village of Skinningrove and the

German ocean. It was Queen’s weather. The sun from early morning shone out

magnificently, and although at noon the heat was somewhat intense, the gentle

breezes wafted up the valley from the sea so tempered the burning rays as to

make the day and most enjoyable one. In the ornamental and mechanical

department there was a great improvement, especially in fretwork, the first

prize being awarded to Mr George Farndale for a magnificent clock frame, the

design being purely gothic, made of black walnut and white Maple, nicely

varnished.

In August

1884, at the Spennymoor Floral and Industrial Exhibition, the fretwork duchese dressing table cut by G Farndale, Loftus, which

has already at other shows been so much admired, received premier honours again.

In September 1884 at the Durham Floral, Horticultural and Industrial Show, Mr

George Farndale, Loftus, entirely merited the first prize for a beautiful

toilet table, which was a marvel of fretwork.

By 1891, George was

working as a joiner in Middlesbrough.

By 1903, he was a member of the religious Order

of Rechabites. The Independent Order of Rechabites, also known as the Sons

and Daughters of Rechab, was a fraternal organisation and friendly society

founded in England in 1835 as part of the wider temperance movement to promote

total abstinence from alcohol.

At the age

of 68, in 1911, George

was working as a picture framer in Middlesbrough,

where he died in 1917.

George and Hannah

Mary Farndale had a family of four, who comprise a section of the family

tree of the Loftus 2 Line.

Their eldest

son, William George Farndale

was a clerk in Middlesbrough, who

clearly followed his father’s passion for social reform and temperance and in

June 1892, succeeded in keeping large numbers of men out of the public

houses by providing a pleasant musical programme. I’m not sure if that

would work today. It was also in 1892 that William married

Annie Emma Bell.

In 1896 William was

acting as a returning officer for council elections for Great Ayton. By 1901 he was an assistant

bookkeeper working in a part of Great

Ayton known as California where he also started translating books

from Spanish. Houses were built in north east Great Ayton for hundreds of men who came

to the village to work as whinstone and ironstone miners. This large scale

immigration was likened to the American gold rush, which is why it became known

as California. There was no street planning and anyone in the village

who owned land put up terraces of houses wherever they could, hence the

irregular street plan. In 1901 an advertisement appeared for Erimus, Impressions of Middlesbrough

from the Spanish of F Alderete Sanchez, translated by W G Farndale. The

public were given a taster of the translated story about their hometown. The

train has arrived. The streets have become quiet and still, and a dull silence

reigns over the town. Here and there the stern athletic figure of a policeman

stands out, vigilant and alert, passing along his beat with slow and measured

step, imperturbably scrutinising each belated passer by hurrying rapidly

homewards. The town hall clock has just struck the hour of 12, and the echoes

of the last peel are slowly dying away. “Erimus” has

given himself over to repose. But yonder on the other side of the river there

is no such thing as repose. Human energy is always in full activity. It matters

little that daylight fades; in that extensive suburb of Middlesbrough.

Why there

was a necessity to translate a novel set in Middlesbrough from Spanish is not

explained. It all seems rather bizarre.

William and

Annie emigrated to the USA in 1907 and by 1910 they had settled in Riverside

City, California, where William had become a naturalised citizen and was

working as an accountant. It is tempting to suppose that William was so

impressed with the attempt to recreate California in Great Ayton, that he couldn’t resist

experiencing the real thing. The reality seems to be that Annie had relatives

in California, and they ended up living with Eliza Bell in Riverside, which may

explain how William

became naturalised so quickly.

George and Hannah

Mary Farndale’s second child was Sarah Anne

Farndale who lived in Great Ayton

with her husband Arthur Wilks, and later, as a widow, in Sheffield. Their

fourth child, Edith Emily

Farndale, was a milliner, who later married John Smith, and settled in Middlesbrough.

George and Hannah

Mary Farndale’s third child was Arthur Edwin

Farndale (1875 to 1962), who became a clerk at the Battersby Rail Junction

with the North Eastern Railway Company. Arthur married Mary Annie Burns in 1896

and they had six children. Arthur and Mary’s eldest son, George

William Farndale (1897 to 1953) became a shipping clerk and financial

accountant and a clerk with the Army Pay Corps and Army Service Corps during

the First World War. Their second son, Arthur Edwin

Burns Farndale (1901 to 1952) was an assistant manager and accountant with

a finance company in Wiltshire. Their third son, Alfred Farndale,

was an engine cleaner with the North Eastern Railway Company and Railway Engine

Firemen at Middlesbrough. Their son Bernard

Farndale (1912 to 1944) was shot down over Denmark in a bombing raid during

the Second World War, and we will pick up his story again later. Their youngest

son Albert

Farndale (1914 to 1986) was an airman and Corporal in the Royal Air Force

in the Second World War and later settled in Chichester.

Their

grandchildren included John

Alan Farndale (1932 to 2012) who also emigrated to USA, whose descendants

are the American 3 Line, and Brian

Picton Farndale (1934 to 2009), son of the bomber

flight engineer, who settled in Wales, and whose family are the Wales 1 Line.

The family

of the Kilton farmer had diversified to a

wealth of different experiences by the twentieth century.

Scene 5 – The Master Grocer of

Stockton

Robert Farndale

(1814 to 1866) was the seventh child of John and Jane Farndale.

By 1841, he was the grocer in Brotton and

he married Sarah Taylor in 1841, the daughter of John Taylor of the

Preventative Service. The

Preventative Service were engaged in preventing the smuggling trade, and I

wonder if John Taylor might have come from the same family as Elizabeth Taylor,

granddaughter of the notorious smuggler John

Andrew, who married Martin Farndale

in 1842. Poachers and gamekeepers lived in worlds that were not so far apart.

In 1844

Robert and Sarah moved to Stockton where

Robert continued working as a grocer.

By 1862, he

was the proprietor of his own grocery business and on 16 May 1862 he announced Near

the North Eastern and Hartlepool Railway Station. R Farndale, announces to his

friends and the public in general, that he has Opened the Shop lately occupied

by Mr M Welch, where he intends to carry on the above business in all its

respective branches. Having had 19 years experience

in one of the largest establishments in the town, RF trusts that by diligent

attention to business and supplying a good article, to merit a share of public

patronage and support. Bishopton Lane, Stockton, 8th May, 1862.

Robert died

at the age of 51, by which time he was a Master Grocer.

Robert and

Sarah had six children, the

Stockton 2 Line.

Robert

Edward Farndale (1844 to 1875) was an Iron ship builder’s clerk and later a

plasterer and cement maker of Stockton

who later lived in Birmingham. His business was bankrupted, and he died five

years later.

Thomas

William Farndale (1848 to 1899) was a brass polisher at the brass foundry

in Stockton.

Mary Emily

Farndale (1860 to 1923) was a private school teacher in Stockton.

Thomas

William Farndale married Elizabeth Shinton White and they had three

children. William

James Farndale became a solicitor’s clerk, and he married Mabel Hills, and

their son William

Hills Farndale (1917 to 2009) became a gas and chemical engineer, who

invented a coal effect fire.

Scene 6 – The Rothbury Farndales

You will

recall that William Leng

Farndale (1876 to 1932) was the last surviving child of George and Catherine

Farndale, who had suffered so much hardship in Stockton in the 1870s. He was born in Middlesbrough and moved with his family

to Liverpool and then to Gateshead by 1891, where William became a clerk in an

iron foundry. In 1896 he married Margaret Johnston and they moved to Rothbury,

north of Morpeth in Northumberland. Rothbury is the town adjacent to the

remarkable house at Cragside, the home of the visionary Victorian inventor

Lord William Armstrong and his wife Lady Margaret Armstrong. In the late

nineteenth century, probably shortly before the arrival of the Farndales in

Rothbury, William Armstrong had been building his extraordinary home fitted

with the most pioneering technology and powered by renewable energy, mainly

hydro power.

William Leng

Farndale served with the Northumberland Imperial Yeomanry (Hussars) and

probably took part in the Second Boer War between 1900 and 1902, when that

Regiment was used as mounted infantry.

William was

a sergeant in the Northumberland Hussars by 1902. In November 1902, perhaps

shortly after their return home, there was an annual dinner and reunion

of those who had fought in South Africa when William held the Colonel’s Cup

shooting prize. In 1905 he was awarded the Imperial Yeomanry Long

Service Medal.

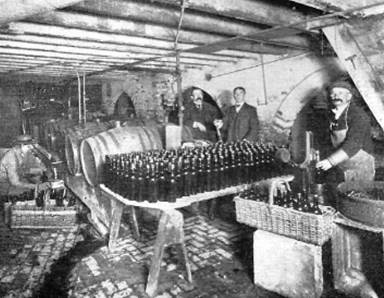

By 1907 he

was managing the Rothbury brewery, continuing the business of Brewers and Wine

Merchants which had been trading as Geo Storey and Company.

William was

regularly involved in social activities in Rothbury and by 1916, he was leading

decision making of the local victualling trade.

Then in

February 1920, he was involved in a violent burglary at his brewery in

Rothbury. A Rothbury policeman was attacked by two Russian seaman during an

attempted robbery at the brewery and William had been called to help.

|

1876 to 1932

Brewer and

Northumberland Hussar of Rothbury, Northumberland |

William and

Margaret Farndale had seven children

who lived in Rothbury, working variously as a clerk at the brewery, hotel

waitresses and a heavy worker at roadstone quarries. One of their sons, Kenneth Farndale

went to Quebec, Canada in 1927 at the age of sixteen amongst boys brought to

Canada by the British

Immigration and Colonisation Association. This was a scheme for British

Boys aged 14 to 18, to work as farm hands and eventually become permanent

citizens. The settlers were selected

carefully as to their health, physical and mental characteristics, previous

records and adaptability. Kenneth

returned to Northumberland in 1931.

Scene 7 – A small Kilton Family

Briefly

turning the hour glass backwards again, there was another family who settled at

Kilton in about 1750. William Farndale

(1725 to 1789), the son of William and Mary

Farndale of the Brotton 1 Line,

married Mary Taylor in 1750 and he became a farmer at Craggs. William and Mary Farndale had

two sons and the younger son, John Farndale

(1755 to 1829) was a husbandman and later a farmer in Kilton too. Their family are the Kilton 3 Line.

John married

Hannah Wilson and they had a family of six, including Wilson Farndale

(1794 to 1857) who worked as an agricultural labourer in Kilton

and Lythe, and John Farndale

(1799 to 1877) who was a farmer of 143 acres at Long Newton near Stockton and sat on a jury in 1845. In 1847 John Farndale the

Younger was praised at a meeting with Lord Londonderry. We also beg to

recommend to your Lordship the names of the following tenants who deserve

commendation for the spirited manner in which they have cultivated their farms,

viz Mr Farndale, Long Newton.

The twenty

first century Farndale family does not descend from this small Kilton family.

However the

larger family of Act 14, of Kilton, Brotton, Loftus,

Stockton, Northumberland and beyond, has

many descendants amongst the twenty first century Farndales.

or

Go Straight to Act 15 – The

Mariners of Whitby