Act 19

Dark Satanic Mills

The Farndale Story met Leeds,

Bradford, Middlesbrough, Hartlepool and Stockton

through the period of industrial transition

|

This

is a new experiment. Using Google’s Notebook LM, listen to an AI powered

podcast summarising this page. This should only be treated as an

introduction, and the AI generation sometimes gets the nuance a bit wrong.

There are a some instances in this podcast where there are mistakes about the

exact relationships and an overlap of generations. However it does provide an

introduction to the themes of this page, which are dealt with in more depth

below. Listen to the podcast for an overview, but it doesn’t replace the text

below, which provides the accurate historical record. |

|

A

flavour of Victorian innovation |

Industrial

Change

A demographic boom increased the

population of England from 5.2 million in 1701 to 17.9 million in 1851. A trend

in increased wages and new job opportunities started in the eighteenth century.

People married younger and had more children. Rev

Thomas Malthus wrote his Essay on

the Principle of Population in 1798. A volcanic

eruption of Mount Tambora in present day Indonesia peaked on 10 April 1815.

This disrupted the climate and caused widespread famine. In the rest of Europe

the consequence of this trend of population growth was sharp deterioration, but

this didn’t happen in Britain. There was no economic disaster. Living standards

were maintained at a relatively high level. Prosperity focused on the growth of

urban areas such as London, Birmingham, Manchester and Liverpool. This was a

period of the growth of new jobs, and a degree of support for incomes through

the Poor Laws.

From the

1850s there was a second stage of industrialisation, boosted by cheap energy

from the new mineral economy. A new clothing demand also drove the industrial revolution. Cotton

was adopted for its colour and brightness. Folk bought goods for enjoyment and self invention. This was a time of self

expression and ambition.

Proponents of change, such as David Hume and Adam Smith welcomed a new

commercial society, and saw a remedy to poverty, and provision of a more

stable, peaceful and civilised society, with new economic freedoms. Wages were

already high, and people had new aspirations and choices. Opponents of change

criticised its moral, social and aesthetic consequences. Skills were devalued

and health deteriorated. Infant mortality was high. People’s physical condition

deteriorated, and people’s heights declined. Real wages barely rose from their

already high levels, about 4% from 1760 to 1820, but food prices rose.

Coketown, to which Messrs Bounderby and Gradgrind now walked, was a

triumph of fact; it had no greater taint of fancy in it than Mrs. Gradgrind

herself. Let us strike the key-note, Coketown, before pursuing our tune.

It was a

town of red brick, or of brick that would have been red if the smoke and ashes

had allowed it; but as matters stood, it was a town of unnatural red and black

like the painted face of a savage. It

was a town of machinery and tall chimneys, out of which interminable serpents

of smoke trailed themselves for ever and ever, and never got uncoiled. It had a black canal in it, and a river that

ran purple with ill-smelling dye, and vast piles of building full of windows

where there was a rattling and a trembling all day long, and where the piston

of the steam-engine worked monotonously up and down, like the head of an

elephant in a state of melancholy madness.

It contained several large streets all very like one another, and many

small streets still more like one another, inhabited by people equally like one

another, who all went in and out at the same hours, with the same sound upon

the same pavements, to do the same work, and to whom every day was the same as

yesterday and to-morrow, and every year the counterpart of the last and the

next.

These

attributes of Coketown were in the main inseparable

from the work by which it was sustained.

You saw

nothing in Coketown but what was severely workful.

The jail

might have been the infirmary, the infirmary might have been the jail, the

town-hall might have been either, or both, or anything else, for anything that

appeared to the contrary in the graces of their construction. Fact, fact, fact, everywhere in the material

aspect of the town; fact, fact, fact, everywhere in the immaterial. The M’Choakumchild school was all fact, and

the school of design was all fact, and the relations between master and man

were all fact, and everything was fact between the lying-in hospital and the

cemetery, and what you couldn’t state in figures, or show to be purchaseable in the cheapest market and saleable in the

dearest, was not, and never should be, world without end, Amen.

(Charles

Dickens, Hard

Times, Chapter V, The Keynote)

Between 1790

and 1850, the sudden industrialisation caused a loss of status for some and

sudden wealth and power for others. Many saw insecurity, disorientation, slum

living and disease. There was uncertainty as to whether the new era would end

in wide prosperity or mass starvation.

The dark

side of the industrial revolution was emphasised in Arnold

Toynbee’s Lectures

on the Industrial Revolution in England and Engels’ anticipation of a

proletarian revolution. There was a bleak interpretation of the industrial

revolution trapping the poor in smoke and squalor.

William Blake’s

Jerusalem contrasted nostalgia for England’s green and pleasant land

with the new industrial landscapes.

|

And did

those feet in ancient time, Walk

upon England’s mountains green: And was

the holy Lamb of God, On

England’s pleasant pastures seen! |

And did

the Countenance Divine, Shine

forth upon our clouded hills? And was

Jerusalem builded here, Among

these dark Satanic Mills? |

Bring me

my Bow of burning gold: Bring

me my Arrows of desire: Bring

me my Spear: O clouds unfold: Bring

me my Chariot of fire! |

I will

not cease from Mental Fight, Nor

shall my Sword sleep in my hand: Till we

have built Jerusalem, In

England’s green & pleasant Land. |

In reality

the famous hymn, written between 1804 to 1820, which became a great patriotic

song in the first world war, is difficult to comprehend. It was written in

consequence of the Napoleonic Wars and envisaged an ancient English order as

God’s chosen people rebuilding Jerusalem, harping back to the long debate since

the Civil War holding underlying rights held to have existed in Anglo Saxon

times before they were swept away by the Normans. Whilst dark satanic mills

have long been associated with the Industrial Revolution, there are

interpretations that the phrase was a criticism of the conformity of the

established Church of England, and that the phrase was an attack on ambitious

church building projects.

Scene 1 - Worsted Spinning in

Bradford

Worsted is a

high-quality wool yarn. The name derives from Worstead,

Norfolk which was a manufacturing centre for yarn and cloth in the twelfth

century, boosted by weavers from Flanders who moved to Norfolk. Worsted yarns

and fabrics are stronger, finer, smoother, and harder than more traditional

woollens. Worsted wool fabric

is preferred in tailoring items such as suits, whilst woollen wool tends

to be used for knitted items such as sweaters.

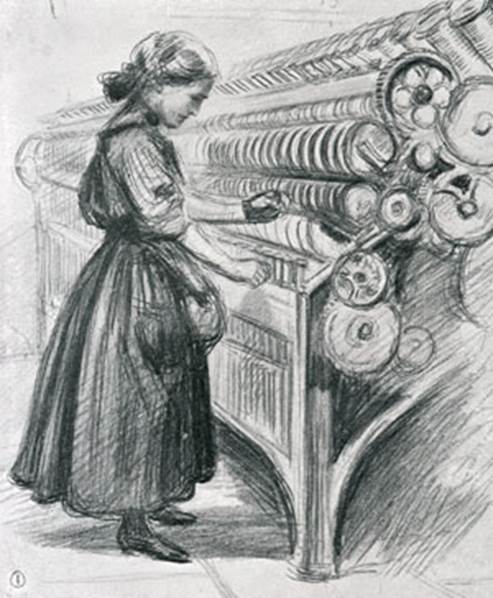

John

Farndale was baptised in Bishop Wilton near York on 23 April 1849 and

became a groom by the age of 21 in 1871. He married Catherine Todd in 1872 and

soon afterwards they moved to Eccleshill and then Clayton in modern Greater Bradford.

John continued to work as a groom in Clayton, but his family all took work in

the worsted industry. By 1891, Annie

Farndale, aged 19, was a worsted drawer and John Farndale, 15

and James

Arthur Farndale, 13, were working as worsted spinners. Annie continued to

work as a drawer until she married Frank Robinson in 1902 after which she

worked as a mill hand until the family emigrated to Massachusetts, where Frank

worked in a paper mill. Cloth drawers, or finishers, inspected the cloth and

used a needle to make any necessary repairs to small holes or blemishes in the

fabric. They were paid relatively well, 30s a week for a drawer compared to 18s

a week for a hand loom weaver and 9s for a power loom weaver, in 1858. Their

sister, Mary

Farndale was working as a worsted spinner by 1901, aged 17 and her sister Maggie Farndale

was a mill hand by 1911, aged 25.

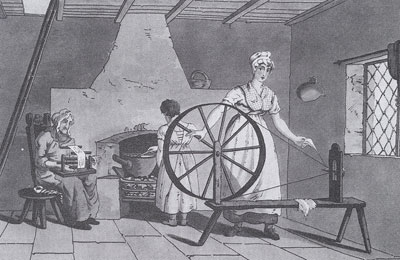

In the

eighteenth century there was a rich tradition of hand loom weaving and

spinning, as well as shoe making and mending, in the cottages of the village of

Clayton. The completed work was sold in Bradford

and at Piece Hall, Halifax. By the early nineteenth century Clayton had over

1,500 hand loom weavers working in their homes.

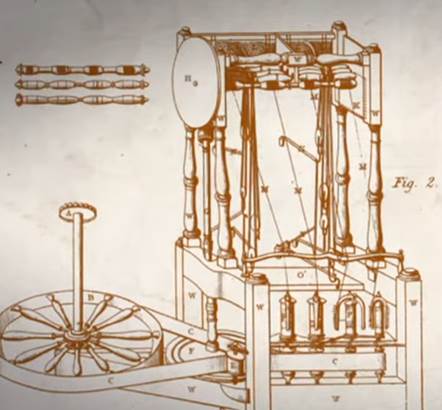

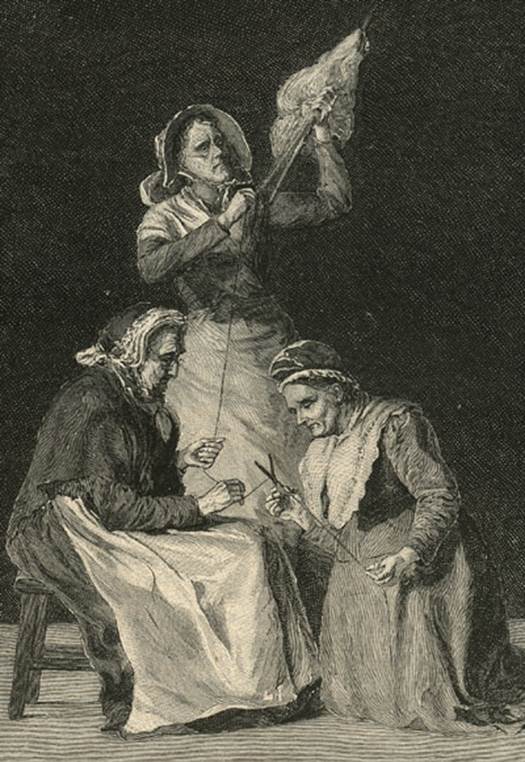

In 1760

England, yarn production from wool, flax and cotton was a vibrant cottage industry.

Fibres were carded and spun by hand using a spinning wheel. As the textile

industry expanded its markets and adopted faster machines, yarn supplies became

scarce especially due to innovations such as the doubling of the loom speed

after the invention of the flying shuttle. High demand for yarn spurred the

invention of the Spinning Jenny in 1765, followed closely by the invention of

the Spinning Frame, later developed into the water frame which was patented in

1769. New technology increased the production of yarn so dramatically that by

1830 the yarn cottage industry in England could no longer compete and all

spinning was carried out in factories.

The

mechanisation of the industrial revolution transferred Clayton’s industry

around a growth of new mills. The first mill to be built in the Clayton area

was Brow Top Mill. Alfred

Wallis, Asa

Briggs and Joseph Benn were the principal manufacturers at Oak Mills and

later Joseph Benn and Sons at Beck Mill. Clayton was well served by public transport from the late

nineteenth century. In October 1874 the Great Northern Railway opened to

Clayton, followed in October 1878 by the Bradford and Halifax lines.

James Arthur Farndale (1877 to 1952) was baptised in Clayton. As a boy Mr

Farndale commenced working at Messrs Joseph Benn and Sons, Beck Mills, Clayton,

eventually becoming an overlooker and after being associated with that firm for

26 years, he was appointed drawing room manager at Saltaire Mills. He

married Florence Edith Greenwood in 1905 at the Wesleyan Chapel in Claton. He was

appointed drawing room manager at Saltaire Mills in January 1914.

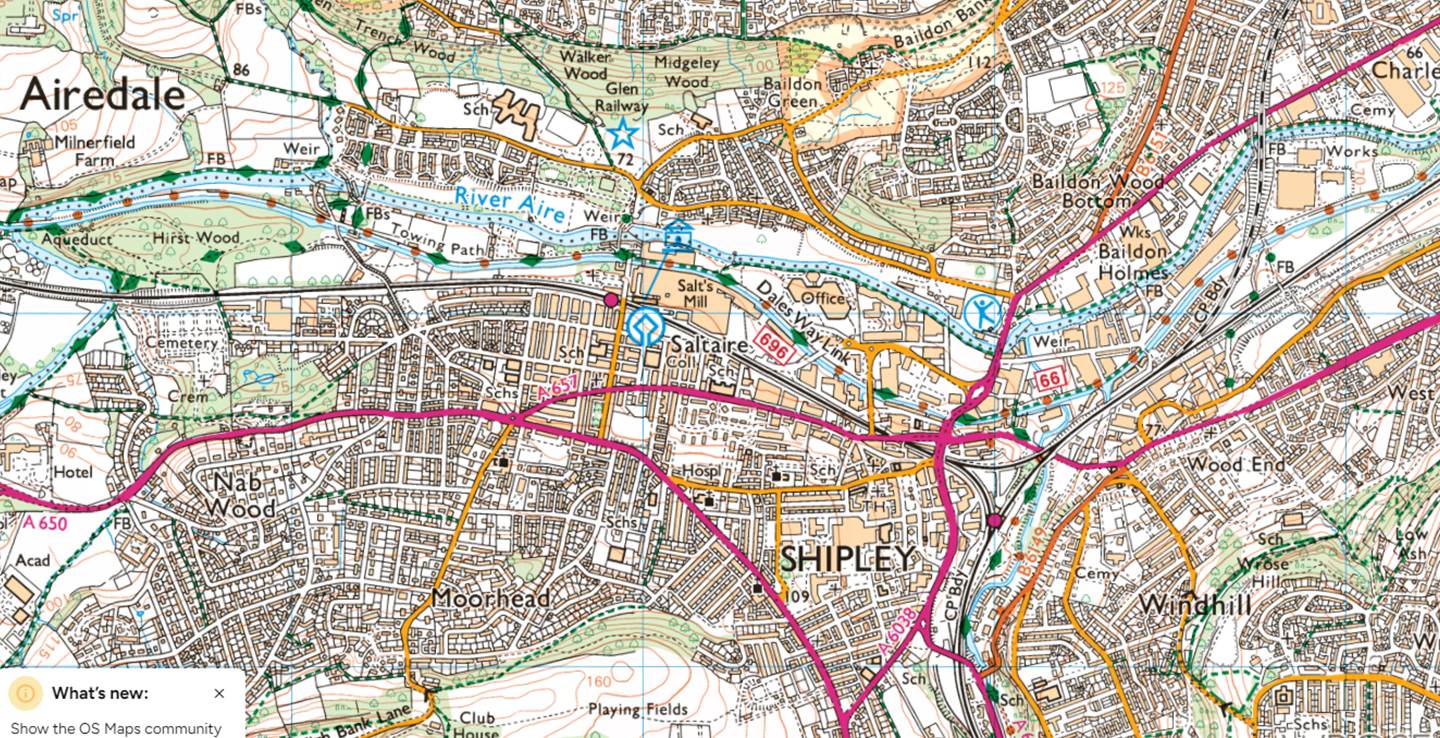

Salts Mill was a textile mill in Saltaire,

Shipley, to the north of Bradford, and

about six kilometres north of Clayton. It was commissioned and financed by the

industrialist and philanthropist, Sir Titus Salt and opened in 1853. Working

conditions in factories were appalling by the mid nineteenth century, with most

workers suffering disease, low wages and labour exploitation. Dangerous

machinery and long hours, sometimes exceeding sixteen hour working days,

resulted in frequent accidents. Titus Salt acknowledged this and built a

factory and surrounding village with which he intended to improve the working

conditions for his employees. The mill was, at the time, the largest industrial

building in the world by total floor area. It was built beside the River Aire. Salts Mill Mill is now a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

James became

attached to Saltaire Cricket Club on coming to live in Albert road in 1914, and

his keenness for cricket in general and this club in particular continued

unabated to the end. During the First World War there were a number of

hearings of the Shipley Military Tribunal which excused James, by then braiding

manager, from military service.

On 31 May

1918, George V and Queen Mary visited Shipley and was welcomed amongst others

by the Chief Constable of Bradford, Joseph

Farndale, who we will meet in Act 21. The object of

their Majesties’ visit, for their three days tour of the West Riding of

Yorkshire - beginning at Bradford on

Wednesday morning and terminating to date today at Leeds,

was really an inspection of representative textile factories that are engaged

on work of national importance. Consequently, local interest could not have

been a greater stimulus, and, so far as circumstances permitted the residents

expressed their appreciation of the royal favour that was conferred on them.

They crowded the places of interests, displayed a large quantity of decorations

in street, shop and residence considering there was no organisation behind this

sort of compliment to their Majesties; and in in a variety of other ways they

indicated the warmth and sincerity of their welcome. It was the first time for

the visit of a King and Queen and the inspection of Saltaire mills was also

high testimony to the industrial importance of the town and to the eminence of

the enterprising spinning and manufacturing Firm, Sir Titus Salt, Bart and sons

and co limited.

Shipley's

association with Royalty began in 1882 when the late King Edward VII and Queen

Alexandra stayed two nights at Milner field, where, at the Prince as the Prince

and Princess of Wales, they came for the opening of the Bradford Technical

College. Coming to Saltaire Station by train, they were received by the

representatives of the town in the grounds of the Saltaire Congregational

Church, a roadway having been cut through the railway embankment. Next morning

they drove from Milner field through Saltaire and Shipley, being received by

the representatives of Bradford at the boundary of Frizinghall.

Among the decorations was an imitation gothic arch at the Frizinghall

entrance to Lister park, and the present permanent arch was afterwards erected

as a memorial of the visit. In May 1887, Royalty was again at Milner Field,

Princess Beatrice being the visitor. She had come to open the Saltaire Jubilee

Exhibition. The late Mr Titus Salt and Mrs Salt were on both occasions resident

at Milner Field. On September 27th 1916 her Imperial Highness the Grand Duchess

George of Russia came to Saltaire from Harrogate, accompanied by her two

daughters, the Princess Nina and Zenia, to open a patriotic bazaar.

The King and

Queen arrived at Sir Titus Salt’s spinning and manufacturing mills at Saltaire,

where James

Farndale was the worsted drawing manager, at 3pm and stayed until 3.40.

By 1925,

James’ family were established in Shipley’s Society. At Christmas in 1924 and

1925, Florence Farndale, James’ wife, handed out Christmas presents to children

of the Fire Brigade and James and Florence were active supporters of the Fire

Brigade, various galas and local sporting events. As well as a keen interest in

cricket, he played bowls and won the gold medal and silver rose bowl in 1926.

Indeed, in

November 1936, their support of the Fire Brigade paid dividends when, after

a thrilling dash through the fog over frost bound roads a Bradford fire brigade

engine reached Baildon in the remarkable time of 11 minutes yesterday to deal

with an outbreak of fire at the home of Mrs James Arthur Farndale, of Oakley,

Sandals Road, Baildon. The fire appears to have originated in one of the

bedrooms and have been caused by an electric radiator becoming overheated. When

the brigade arrived on the scene the upper floor was filled with dense clouds

of smoke, and it was necessary to use oxygen apparatus in order to approach the

seat of the fire. The flames were quickly brought under control, but it is

thought that the damage may exceed £100. The house was “Oakley”, the property of Mr. James A

Farndale.

James

retired in 1942 after having held the position of manager of the drawing

room at Saltaire mills for 28 ½ years, a good record of service. Mr R W

Guild, managing director, on behalf of the directors, presented Mr Farndale

with a cheque; the managers and staff also gave him a cheque; and all connected

with the drawing room gave him as a parting gift a beautiful electric clock. Mr

Guild in making the presentation on behalf of the directors spoke very highly

of the excellent services rendered by Mr Farndale in his capacity as manager of

the drawing room and assured him that he left with the best wishes of all those

connected with the firm. Mr O Dennison, spinning manager, who made the

presentation on behalf of the managers and staff spoke in a similar vein, and

of the high esteem in which he was held by everybody.

He has

been actively connected with the sports activities of the firm and was formerly

a playing member of the Salts Bowling Club, whilst he has been a member of the

Saltaire Football Club. Mr Farndale has also taken a keen interest in Saltaire

Cricket Club, of which he is vice president and an active member of the

committee. He is held in huge esteem by the directors, managers and work people

of Saltaire Mills, when on Friday everybody gave tangible expression of their

esteem. A life member of Saltaire Cricket

Club, he had voluntarily tended their Roberts Park ground for five seasons.

On 1 March

1952, James collapsed in a bus while returning from Saturdays football match

at Park Avenue and died almost immediately.

We will meet

his son Wilfred

Farndale, who became a locally renown cricketer and Shipley’s sanitary

inspector, in Act 33.

James’

brother, William

Farndale started a plumbing partnership in Bradford

and his daughters, Edith

Farndale and May

Farndale were both bookkeepers at the Infant Clinic in Bradford. Tom Farndale became

a machine moulder and his daughter Minnie Farndale

was working as a cotton weaver in 1939 in Padiham in

Lancashire. Robert

George Farndale (1909 to 1978) left Hartlepool

to marry Winifred Sibley in 1934. He worked as a French polisher in Bradford and they had a family of six. His

son, Peter

Farndale, was secretary of the Bradford

Rugby Central League.

Scene 2 - The Cordwainer of Leeds

John Farndale was

a shoe maker’s apprentice at Crayke, a village east

of Easingwold, aged 14, in 1841. In 1856 John married Sarah Ann Brittain in Leeds and they set up home in Bramley near Leeds. By then John was working as a cordwainer,

a craftsman of new shoes distinguished at that time from the cobbler who fixed

them. John was still making shoes and boots in Bramley in 1901 by which time he

was aged 68 and a widower. He died in 1902.

As the

population of Leeds grew, so did the demand for meat,

and this meant a local supply of hides and skins for the leather industry.

The leather industry in turn

provided material for the footwear industry, which became an important trade in

Leeds from the 1830s, mostly making boots . A

major footwear producer in Leeds was Stead and Simpson who started out as

curriers and leather factors in 1834. In the 1840’s they began to make ready made boots, and shoes. Many footwear manufacturers

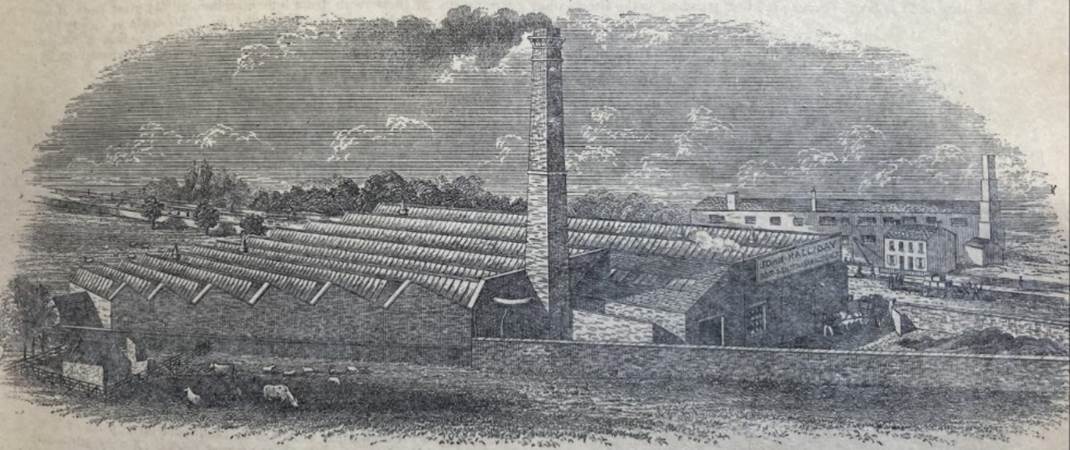

remained as small firms, but some like John Halliday outgrew his workshop in

Harrison’s Yard, Bramley, and built a large factory employing 450 people making

strong boots for the home and export market. Another large manufacturer was F

& W Jackson.

The

Halliday Factory in Bramley

John and

Sarah had a family of eleven. Their eldest son, Joseph Farndale,

was also working as a shoemaker by the age of 14. He died, aged 34, in 1891. Jethro Farndale

was also a shoemaker, and he too died young at the age of 32 in 1893. Peter Farndale

was another shoemaker. Mary

Farndale, Alice

Farndale, Elias

Farndale, and William

Farndale, all died in infancy. Elizabeth

Farndale worked as a shoemaker machinist by 1881 and continued to work as a

boot machinist after she was married to an iron miller, John Gall. She died

when she was 47. The youngest son, John Farndale,

became a boot rivetter.

Scene 3 - Heavy Industry in Stockton

John Farndale (1796 to 1868) was a farm labourer at Brotton who married Elizabeth Wallace in

1827. They had a family of ten, the Stockton 1 Line. The family then moved to Middlesbrough, where John was working as a

labourer and merchant in 1851, and he became bankrupt. By 1861, John was

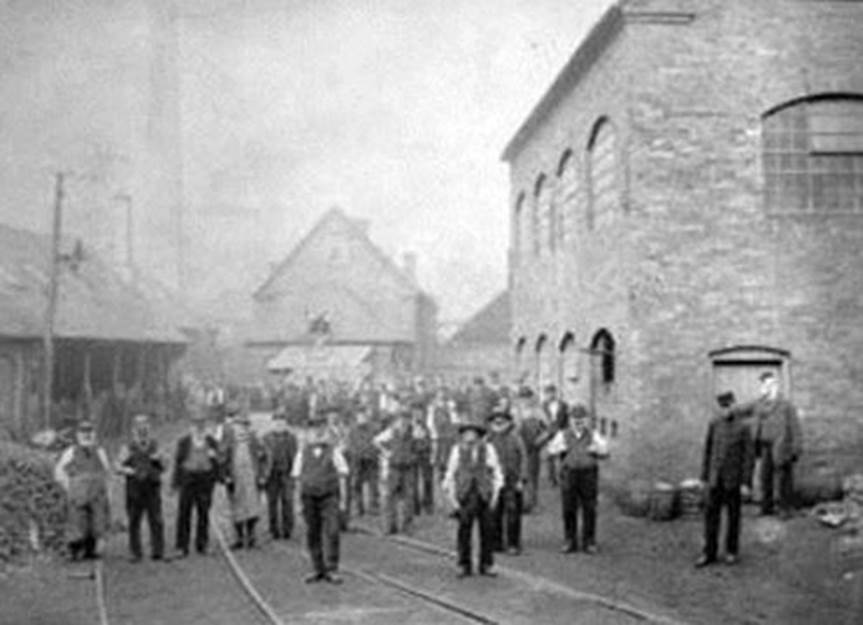

working in the iron foundry in Stockton.

Iron Foundry, Stockton

We met his sons William Farndale and Peter Farndale, who were solicitors’ clerks in Stockton, and George Farndale, the grocer, in Act 14 Scene 2.

Robert Farndale (1814 to 1866) also became a grocer in Stockton. He married Sarah Taylor of Saltburn in 1841 and they had a family of

six. Robert Edward Farndale was an iron ship builder’s clerk and later a plasterer and cement maker

of Stockton but his business was bankrupted, and

he died five years later in Birmingham.

William Farndale (1849 to 1927) was a footman when he married Jane Gale at Bedale on 8 February 1870. William and Jane

had their own family of seven, the Stockton 3 Line. In about 1881, the family moved to Stockton, where William became a car man and

later a boilersmith labourer. Their son William Farndale moved to Norwich, and we will meet him in Act 20. Their son, James Farndale

worked in an iron foundry and for a time in steam engine works in Stockton. In 1909 James Farndale became a

brother of the Order of Druids Friendly Society and later joined the committee.

He joined the Royal Field Artillery in the First World War. Their son Tom Farndale became

a general and fitter’s labourer and machine helper whose children included Wilf Farndale

who was an aircraft engineer who later emigrated to New Zealand.

Scene 4 – Shipbuilding and heavy

industry in Hartlepool

Robert George

Farndale (1834 to 1900) grew up in Great

Ayton, part of the Great

Ayton 3 Line, and worked as a farm labourer. In 1862, he married Mary

Butterworth in West Hartlepool, by which

time he was working as a shoemaker. They had seven children, the Hartlepool Line. He was

still working as a shoemaker in 1892, when he was involved in the proposal of

Christopher Furness, a steamship owner and shipbuilder, as the liberal

candidate for West Hartlepool. He became a master boot and shoe maker. He had a

low point in 1898 when an old man named Robert Farndale was summoned at the

West Hartlepool Police Court this morning for non payment

of improvement and highway rates amounting to £1 16s 10d. It was stated that

great efforts had been made to recover the money, but in vain. A distress

warrant was issued, but it had been returned endorsed “no goods.” Farndale was

ordered to be sent to gaol for 14 days in default of payment. He died of

pneumonia at 18 Benson Street, West Hartlepool, on 14 January 1900.

When

Isambard Kingdom Brunel visited Hartlepool

in December 1831, he described it as a curiously isolated old fishing town –

a remarkably fine race of men. Went to the top of the church tower for a view.

In 1831 the population of Hartlepool was still only 1,300. In 1833, the council

agreed to the formation of the Hartlepool Dock and Railway Company (“HD&RCo”) to extend the existing port by

developing new docks, and link to both local collieries and the developing

railway network in the south. In 1835, a railway link was established from the

South Durham coal fields, and new docks opened in 1835. From 1836 there was a

gas supply for gaslight. This expansion led to the new town of West Hartlepool.

West Hartlepool grew out of a dispute between the owners of the railway and the

owners of the docks. The owners of the railway decided to build their own docks

south west of the town. The eight acres West Hartlepool Harbour and Dock opened

on 1 June 1847. Almost immediately the new town of West Hartlepool sprang up nearby. In 1878 the

William Gray & Co shipyard in West Hartlepool launched the largest tonnage

of any shipyard in the world. By 1881, old Hartlepool's population had grown to

12,361, but West Hartlepool had a population of 28,000. Ward Jackson helped to plan the

layout of West Hartlepool and was responsible for the first public buildings.

He was also involved in education and welfare. In the end, he was a victim of

his own ambition to promote the town, with accusations of corruption and legal

battles, left him in near-poverty. He spent the last few years of his life in

London, far away from the town he had created. In 1891 the two towns had a combined population of

64,000. By 1900 the two Hartlepools were, together,

one of the three busiest ports in England.

By 1913,

there were forty three ship-owning companies located in the town, with

responsibility for 236 ships. This made it a key target for Germany in the

First World War. One of the first German offensives against Britain was the

raid on the east Yorkshire coast on the morning of 16 December 1914, when the

Imperial German Navy bombarded Hartlepool,

West Hartlepool, Whitby and Scarborough.

Hartlepool was hit by 1,150 shells,

killing 117 people.

Robert and

Elizabeth’s oldest son, John George

Farndale was working as a labourer in Hartlepool,

at the age of 17, by 1881 and by the turn of the century he was working as a

cement trimmer in West Hartlepool. He

became treasurer of the Hartlepool Branch of the Royal Antediluvian Order of

Buffaloes, known as the Buffs to members, one of the largest fraternal

movements which started in 1822 and which spread throughout the former British

Empire. Henry

Farndale was working as a sailor in Hartlepool

by the age of 22, in 1891. In 1892, he married Elizabeth Armin, and they had

eleven children. By 1901 he was working as a barman in Middlesbrough, but had returned to West Hartlepool by 1911, then working as a

shipwright’s labourer. He played football for local teams. He was reported as a

deserter from the Royal Navy in 1916, but rejoined his ship, the Pembroke,

and was ordered not to be apprehended. He served as a stoker with the Royal

Navy Reserve. By 1921, he was an Able Seaman with the Mercantile Marine,

working for the Eagle Oil Transport Company. Founded as the Eagle Oil Transport

Company in 1912, the Company was sold to Royal Dutch Shell in 1919. It was

renamed Eagle Oil and Shipping Company in about 1930, and remained a separate

company within the Royal Dutch Shell group until it was absorbed in 1959. William Farndale

was a hotel barman in Stockton and by 1911

he was working on a poultry farm in Darlington.

By 1921, he worked there as a fitter’s labourer with J Finsley

Limited who were hauling engineers at Westfield Engine Works. Robert Farndale,

a football back, was a hotel manager in West Hartlepool

by 1906, and later like his two brothers, he also worked as a barman. Robert

was wounded in the First World War, and worked as a labourer in the shipyards

in Hartlepool after the War, including

with Irain Shipbuilding, but in 1921 he was out of work.

Of the third

generation of this family, Ethel Farndale

was a fish dealer’s assistant in Hartlepool

by 1911. Hilda

Farndale and Olive

Farndale married two brothers, Fred Wager and Hezekiah Wager in 1920 and

1922. Henry

Farndale was a general labourer with E A Fortlind

Timber Merchants of West Hartlepool

before he moved to Bradford by the Second

World War where he worked as a public works contractor. John Armin

Farndale was a labourer working in Hartlepool

in December 1915 when at about two o’clock, he was in his own room on the

top landing, when he heard a child screaming. He ran downstairs, and at the

first landing he saw the little girl in flames. He started to tear the clothes

from the child, and whilst doing so a Mrs Hogg ran to his assistance. Someone

wrapped a blanket around the child, and carried her into a room. The room in

which the child was burnt was that of Mrs Mann, and not a room in her own

house. Mrs Mann, the wife of a soldier, said the mother of the child shouted to

her “Maudie, my bairn, has been burned.” After the War, John was working as

a Coggie Tram Driver at plate rolling mills, at the

South Durham Steel and Iron Company in Hartlepool,

but he was out of work in 1921. In 1854 John Pile, a shipbuilder, founding the

West Hartlepool Rolling Mills Company which based its business on an iron works

which supplied materials to build iron ships. He travelled to New York on the

Queen Elizabeth in 1957 and later settled in Bradford.

Doris Farndale

also moved to Bradford and by the outbreak

of World War Two, she was working as a fly frame spinner. James

Armin Farndale also moved to Bradford

and worked as a labourer there. William Farndale

became an engineer in Bradford.

William

Robert Farndale was an oiler with the North Eastern Railway Company, by 1921,

working at Bank Top Railway Station in Darlington.

His sister Lily

was a hairdresser there at the outbreak of the Second World War when brother Sidney was

working as a labourer and Reginald was

working as a moulder’s labourer.

or

Go Straight to Act 20 – The Southerners

There is an

In Our Time podcast on the

Industrial Revolution, on the far-reaching consequences of the Industrial Revolution,

which brought widespread social and intellectual change to Britain and on Isambard Kingdom Brunel,

the Victorian engineer responsible for bridges, tunnels and railways still in

use today.