Agricultural Change

The evolution of farming and rural

life from the eighteenth century

Rural

lives

In their

houses the good, solid, hand-made furniture of their forefathers had given

place to the cheap and ugly products of the early machine age. A deal table,

the top ribbed and softened by much scrubbing; four or five windsor

chairs with the varnish blistered and flaking; a side table for the family

photographs and ornaments, and a few stools for fireside seats, together with

the beds upstairs, made up the collection spoken of by its owners as 'our few

sticks of furniture'. If the father had a special chair in which to rest after

his day's work was done, it would be but a rather larger replica of the hard windsors with wooden arms added.

As

ornaments for their mantelpieces and side tables the women liked gaudy glass

vases, pottery images of animals, shell-covered boxes and plush photograph

frames.

Those who

could find the necessary cash covered their walls with wall-paper in big,

sprawling, brightly coloured flower designs. Those who could not, used

whitewash or pasted up newspaper sheets.

Monday

was washing-day, and then the place fairly hummed with activity.

After

their meagre midday meal, the women allowed themselves a little leisure. In

summer, some of them would take out their sewing and do it in company with

others in the shade of one of the houses. Others would sew or read indoors, or

carry their babies out in the garden for an airing. A few who had no very young

children liked to have what they called 'a bit of a lay down' on the bed. (Lark Rise, Flora Thomson,

Chapter VI, the

Besieged Generation)

Local rural

communities would have relied upon local businesses such as blacksmiths and

iron foundries, such as these, reconstructed at the Ryedale Folk Museum near

Farndale today.

There were

many foundries across the North Yorkshire Moors that specialised in the

production of parts for ranges. People could choose features and even

decoration, as they wished – for instance one or two ovens, separate or

combined hearths, a turf plate or coal basket and left or right handed.

Complicated flues to alter the draught could be operated to transfer heat from

the main hearth to the ovens to cook.

Supplying

water to a nineteenth century house could be a challenge. Few of the poorer

houses had indoor taps and people relied upon communal supplies such as rivers,

wells and springs. Two buckets might be carried with a yoke.

Small

houses, big families

The Rev J C

Atkinson, a local historian, describes visiting local cottages at Skelton in 1841. We then

went to two cottage dwellings in the main street. As entering from the street

or roadside, we had to bow our heads, even although some of the yard-thick

thatch had been cut away about and above the upper part of the door, in order

to obtain an entrance. We entered on a totally dark and unflagged passage. On

our left was an enclosure partitioned off from the passage by a boarded screen

between four and five feet high, and which no long time before had served the

purpose originally intended, namely that of a calves’ pen. Farther still on the

same side was another dark enclosure similarly constructed, which even yet

served the purpose of a henhouse. On the other side of the passage opposite

this was a door, which on being opened gave admission to the living room, the

only one in the dwelling. The floor was of clay and in holes, and around on two

sides were the cubicles, or sleeping boxes – even less desirable than the box

beds of Berwickshire as I knew them fifty years ago – for the entire family.

There was no loft above, much less any attempt at a ‘chamber’ ; only odds and

ends of old garments, bundles of fodder and things of that sort and in this den

the occupants of the house were living.

Of the

sleeping arrangements at a farm near Kilton Castle, he wrote What I found

was one long low room, partitioned off into four compartments nearly equal in

size. But the partitions were in their construction and character merely such

as those between the stalls in a stable, except that no gentleman who cared for

his horses would have tolerated them in his hunting or coaching stable. These

four partitioned spaces were no more closed in the rear than the stalls in an

ordinary stable, and the partitions were not seven feet, hardly six and a half

in height, while the general gangway for all the occupants was along the open

back. The poor woman said to me, as she showed me the first partition, allotted

to her husband and herself and their two youngest children, the next to their

children growing rapidly up to puberty, the third to the farm girls, and the

fourth to the man and farm lad, “How can I keep even

my children clean when I can only lodge them so?”

Then

there was the sleeping problem. None of the cottages had more than two

bedrooms, and when children of both sexes were entering their teens it was

difficult to arrange matters, and the departure of even one small girl of

twelve made a little more room for those remaining. When the older boys of a

family began to grow up, the second bedroom became the boys' room. Boys, big

and little, were packed into it, and the girls still at home had to sleep in

the parents' room. They had their own standard of decency; a screen was placed

or a curtain was drawn to form a partition between the parents' and children's

beds; but it was, at best, a poor makeshift arrangement, irritating, cramped,

and inconvenient. If there happened to be one big boy, with several girls following

him in age, he would sleep downstairs on a bed made up every night and the

second bedroom would be the girls' room. When the girls came home from service

for their summer holiday, it was the custom for the father to sleep downstairs

that the girl might share her mother's bed. It is common now to hear people

say, when looking at some little old cottage, 'And they brought up ten children

there. Where on earth did they sleep?' And the answer is, or should be, that

they did not all sleep there at the same time. Obviously they could not. By the

time the youngest of such a family was born, the eldest would probably be

twenty and have been out in the world for years, as would those who came

immediately after in age. The overcrowding was bad enough; but not quite as bad

as people imagine. (Lark

Rise, Flora Thomson, Chapter X, Daughters

of the Hamlet)

Agricultural

Labourers

The historical

family is rooted in the land and agriculture. Until the

industrial revolution, most of the British population was rural dominated

by small local communities.

As the

family moved its centre of gravity to the area of Cleveland when Nicholas Farndale’s

family moved there in perhaps about 1565, the focus remained rural for another

three centuries. There were groups of the family who moved to the larger urban

port town of Whitby where many turned to

the sea for work, and when the

industrial revolution came, others found work in the mines, whilst some

large groups of the family moved to urban centres such as Leeds and

Bradford, particularly to work in the textile industry. However the bulk of

the family continued to work in agricultural roles and mostly within a

comparatively small radius of not more than about ten miles around Guisborough. The bulk of the family

remained in a rural setting, working for others on the land, and sometimes

becoming tenant farmers themselves.

The lives of

many members of the family through time, was a life of work for others on the

fields. They included George Farndale of

Brotton, Jethro

Farndale of Ampleforth, Wilson Farndale,

Henry Farndale of

Great Ayton, William

Farndale of Brotton, William Farndale of

Whitby, William

Farndale of Seltringham, John Farndale of

Eskdaleside, Martin

Farndale of Kilton, William Farndale of

Great Ayton, Joseph

Farndale of Whitby, William Farndale of

Ampleforth, John

Farndale of Kilton, Richard Farndale of

Great Ayton, Matthew

Farndale of Coatham, John Farndale, John George Farndale

before he emigrated to Ontario, William Farndale of

Loftus, Thomas

Farndale of Ampleforth and George Farndale of

Loftus.

Very

early in the morning, before daybreak for the greater part of the year, the

hamlet men would throw on their clothes, breakfast on bread and lard, snatch

the dinner-baskets which had been packed for them overnight, and hurry off

across fields and over stiles to the farm. Getting the boys off was a more

difficult matter. Mothers would have to call and shake and sometimes pull boys

of eleven or twelve out of their warm beds on a winter morning. Then boots

which had been drying inside the fender all night and had become shrunk and

hard as boards in the process would have to be coaxed on over chilblains.

Sometimes a very small boy would cry over this and his mother to cheer him

would remind him that they were only boots, not breeches. 'Good thing you didn't

live when breeches wer' made o' leather,' she would

say, and tell him about the boy of a previous generation whose leather breeches

were so baked up in drying that it took him an hour to get into them.

'Patience! Have patience, my son', his mother had exhorted. 'Remember Job.'

'Job!' scoffed the boy. 'What did he know about patience? He didn't have to

wear no leather breeches. (Lark Rise, Flora Thomson, Chapter III, Men

Afield)

The elders

stooped, had gnarled and swollen hands and walked badly, for they felt the

effects of a life spent out of doors in all weathers and of the rheumatism

which tried most of them.

The men's

incomes were the same to a penny; their circumstances, pleasures, and their

daily field work were shared in common; but in themselves they differed; as

other men of their day differed, in country and town. Some were intelligent,

others slow at the uptake; some were kind and helpful, others selfish; some

vivacious, others taciturn. If a stranger had gone there looking for the

conventional Hodge, he would not have found him.

Their

favourite virtue was endurance. Not to flinch from pain or hardship was their

ideal. A man would say, 'He says, says he, that field o' oo-ats's

got to come in afore night, for there's a rain a-comin'.

But we didn't flinch, not we! Got the last loo-ad under cover by midnight. A'moost too fagged-out to walk home; but we didn't flinch.

We done it!' Or,'Ole bull he comes for me, wi's head down. But I didn't flinch. I ripped off a bit o'

loose rail an' went for he. 'Twas him as did th' flinchin'. He! he!' Or a

woman would say, 'I set up wi' my poor old mother six

nights runnin'; never had me clothes off. But I

didn't flinch, an' I pulled her through, for she didn't flinch neither.' Or a

young wife would say to the midwife after her first confinement, 'I didn't

flinch, did I? Oh, I do hope I didn't flinch.'

The farm

was large, extending far beyond the parish boundaries; being, in fact, several

farms, formerly in separate occupancy, but now thrown into one and ruled over

by the rich old man at the Tudor farmhouse. The meadows around the farmstead

sufficed for the carthorses' grazing and to support the store cattle and a

couple of milking cows which supplied the farmer's family and those of a few of

his immediate neighbours with butter and milk. A few fields were sown with

grass seed for hay, and sainfoin and rye were grown and cut green for cattle

food. The rest was arable land producing corn and root crops, chiefly wheat.

Around

the farmhouse were grouped the farm buildings; stables for the great stamping

shaggy-fetlocked carthorses; barns with doors so wide and high that a load of

hay could be driven through; sheds for the yellow-and-blue painted farm wagons,

granaries with outdoor staircases; and sheds for storing oilcake, artificial

manures, and agricultural implements. In the rickyard, tall, pointed,

elaborately thatched ricks stood on stone straddles; the dairy indoors, though

small, was a model one; there was a profusion of all that was necessary or

desirable for good farming.

The field

names gave the clue to the fields' history. Near the farmhouse, 'Moat Piece',

'Fishponds', 'Duffus [i.e. dovehouse] piece',

'Kennels', and 'Warren Piece' spoke of a time before the Tudor house took the

place of another and older establishment. One name was as good as another to most of the men; to

them it was just a name and meant nothing. What mattered to them about the

field in which they happened to be working was whether the road was good or bad

which led from the farm to it; or if it was comparatively sheltered or one of

those bleak open places which the wind hurtled through, driving the rain

through the clothes to the very pores; and was the soil easily workable or of

back-breaking heaviness or so bound together with that 'hemmed' twitch that a

ploughshare could scarcely get through it.

There

were usually three or four ploughs to a field, each of them drawn by a team of

three horses, with a boy at the head of the leader and the ploughman behind at

the shafts. All day, up and down they would go, ribbing the pale stubble with

stripes of dark furrows, which, as the day advanced, would get wider and nearer

together, until, at length, the whole field lay a rich velvety plum-colour.

The

labourers worked hard and well when they considered the occasion demanded it

and kept up a good steady pace at all times. Some were better workmen than

others, of course; but the majority took a pride in their craft and were fond

of explaining to an outsider that field work was not the fool's job that some

townsmen considered it. Things must be done just so and at the exact moment,

they said; there were ins and outs in good land work which took a man's

lifetime to learn. A few of less admirable build would boast: 'We gets ten bob

a week, a' we yarns every penny of it; but we doesn't yarn no more; we takes

hemmed good care o' that!' But at team work, at least, such 'slack-twisted 'uns' had to keep in step, and the pace, if slow, was steady.

The first

charge on the labourers' ten shillings was house rent. Most of the cottages

belonged to small tradesmen in the market town and the weekly rents ranged from

one shilling to half a crown. Some labourers in other villages worked on farms

or estates where they had their cottages rent free; but the hamlet people did

not envy them, for 'Stands to reason,' they said, 'they've allus

got to do just what they be told, or out they goes, neck and crop, bag and

baggage.' A shilling, or even two shillings a week, they felt, was not too much

to pay for the freedom to live and vote as they liked and to go to church or

chapel or neither as they preferred. (Lark Rise, Flora Thomson, Chapter I, Poor

People's Houses)

After the

mowing and reaping and binding came the carrying, the busiest time of all.

Every man and boy put his best foot forward then,

Harvest

home! Harvest home!

Merry,

merry, merry harvest home!

Our

bottles are empty, our barrels won't run,

And we

think it's a very dry harvest home.

the

farmer came out, followed by his daughters and maids with jugs and bottles and

mugs, and drinks were handed round amidst general congratulations.

the

harvest home dinner everybody prepared themselves for a tremendous feast. (Lark Rise, Flora Thomson,

Chapter XV, Harvest

Home)

Tenant

farmers

The

Farndales who became tenant farmers included John Farndale, “Old

Farndale of Kilton”, William Farndale,

Farmer of Craggs, William Farndale

perhaps for a time, John

Farndale, John

Farndale, William

Farndale, Elias

Farndale of Ampleforth, John Farndale,

for a time before he turned to trade and agency and became a writer, Matthew

Farndale, who then emigrated to Australia where he became rooted to the

land of Victoria, John

Farndale, Martin

Farndale of Kilton, John Farndale, John Farndale of

Whitby, George

Farndale of Kilton, Elias Farndale of

Ampleforth, Charles

Farndale of Kilton Hall Farm, George Farndale of

Brotton, Martin

Farndale of Tidkinhow, Matthew Farndale of

Craggs, William

Farndale of Gillingwood Hall, Richmond, John William

Farndale of Danby, George Farndale

of Kilton, John

Farndale at Tidkinhow, Martin Farndale,

cattle farmer of Alberta, George Farndale,

farmer at Three Hills, Alberta, Catherine

Farndale and the Kinseys in Alberta, Herbert Farndale of

Craggs, Grace

Farndale and Howard Holmes, William Farndale of

Thirsk, Alfred

Farndale of Wensleydale and Geoff

Farndale of Wensleydale.

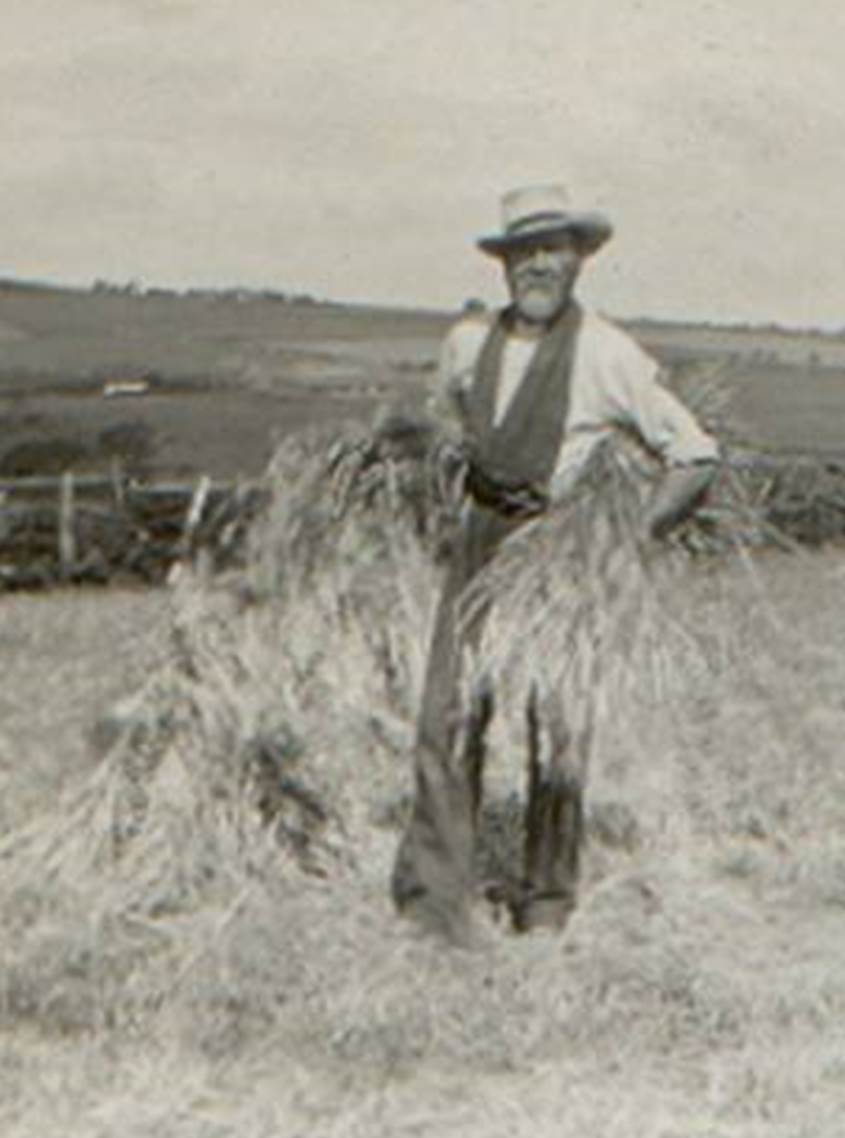

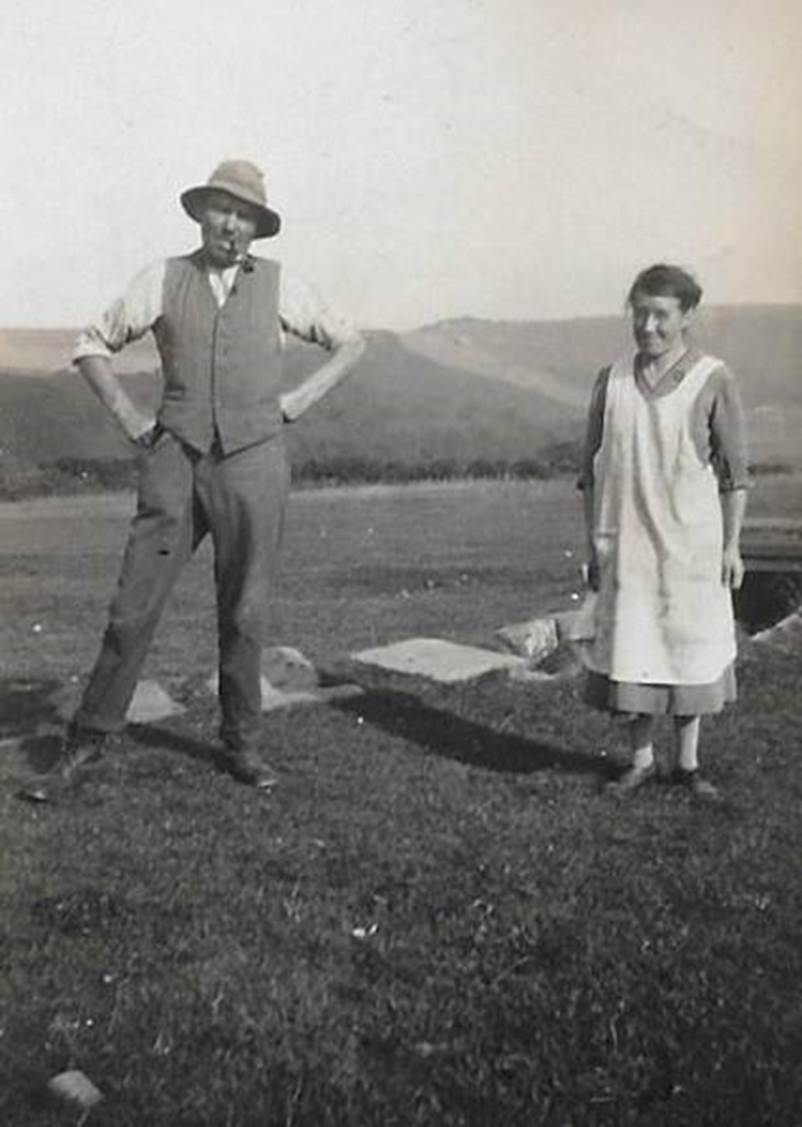

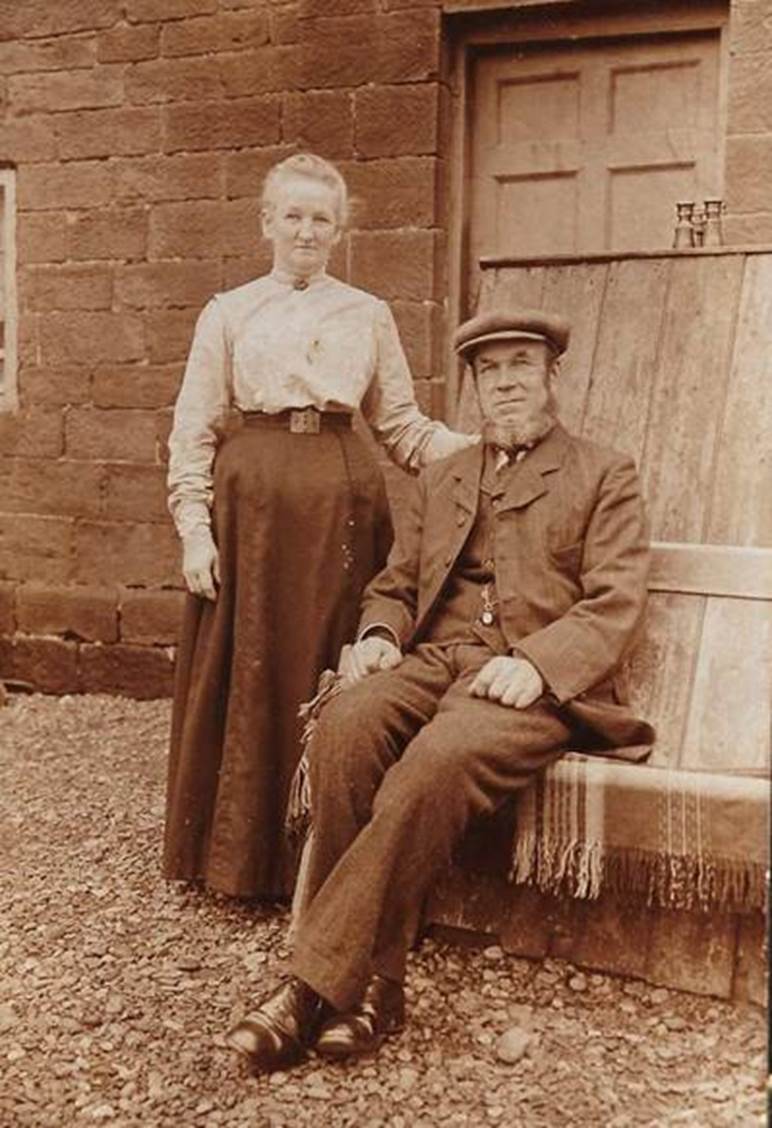

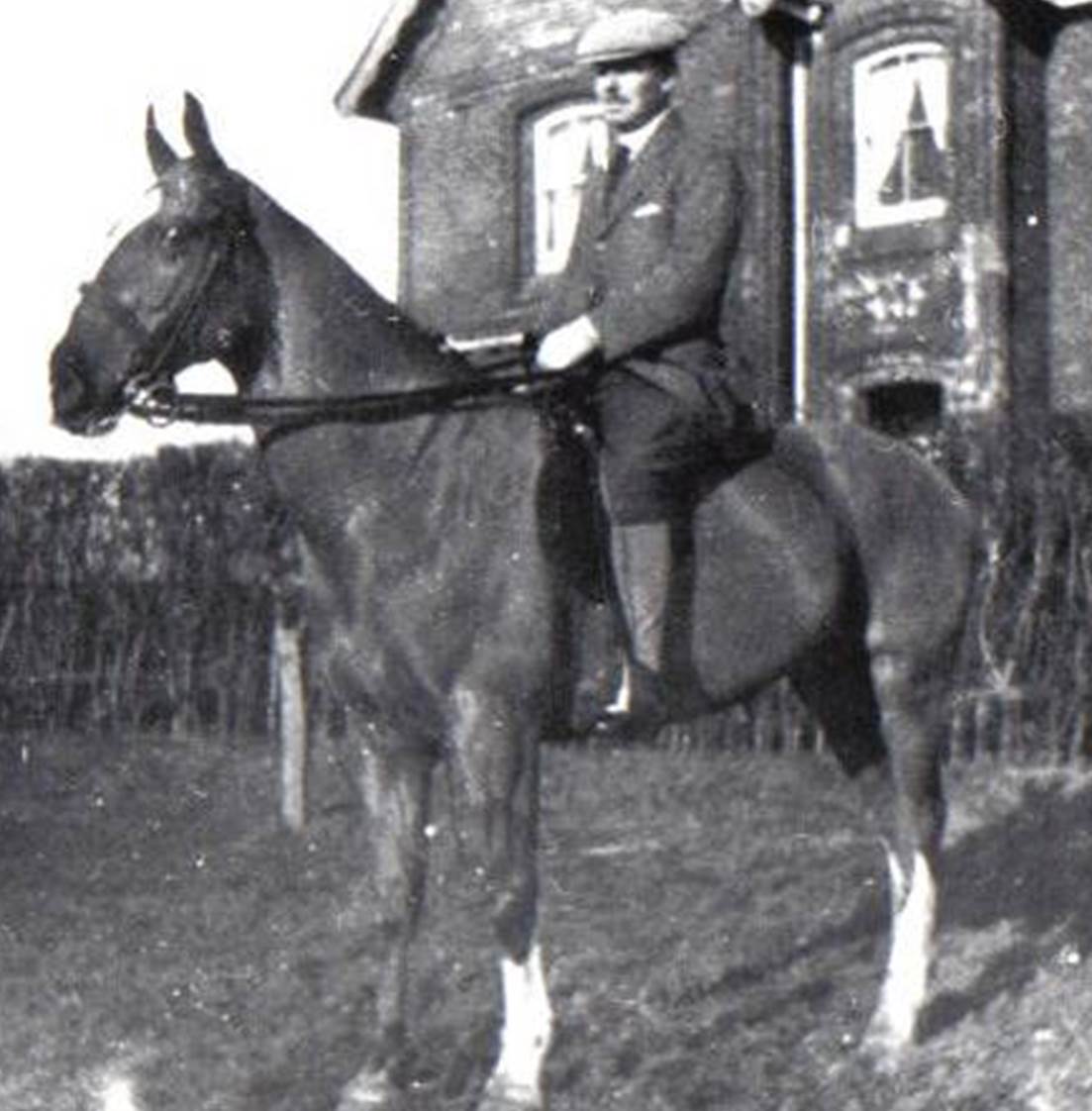

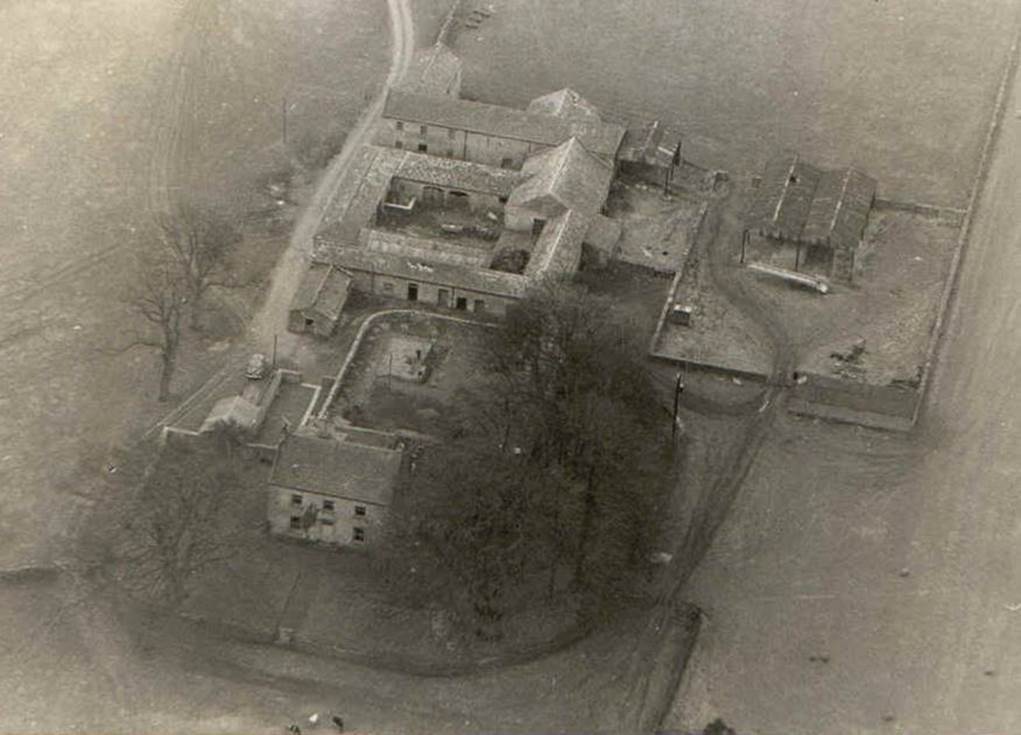

Martin

Farndale at Tidkinhow about 1920

John Farndale at Tidkinhow about 1937

Matthew Farndale and Mary Ann at Craggs Hall Farm, about 1900 George Farndale, of Kilton Hall

Farm, about 1925

…

Agricultural

change

Significant

changes were taking place quietly in agricultural practice. Commonly used local

varieties of wheat and oats were replaced or supplemented by imported seeds.

Enclosures

spread rapidly around Malton, for instance at Huttons Ambo and Appleton le

Street.

Local power

depended on deference, but by the early eighteenth century, deference had to be

earned. There was a growing confederacy between those working on the land who

increasingly saw the Squire’s property as fair booty and who colluded to help

each other against punishment.

In 1734

Jethro Tull (1674 to 1741), an agricultural pioneer from Berkshire, published essays

on improving farming including the use of the seed drill. He had perfected

a horse-drawn seed drill in 1701 that economically sowed the seeds in neat

rows. He later developed a horse-drawn hoe. Tull's methods were widely adopted

and began a new phase of revolution in agricultural techniques.

Jethro

Tull's seed drill

The

nineteenth century was a period of exponential growth in the production of

coal, pig iron and the consumption of raw cotton, dwarfing progress in France

and Germany. The growth in non agricultural

production meant a growing population had to be fed by imports. Since 1822

Britain’s balance of trade has remained permanently in deficit. It had to be

balanced by invisible earnings from banking, insurance and shipping, and

returns from foreign investments.

This brought

new kinds of wealth through commerce, manufacturing, food and drink, tobacco

and new wealthy families, like the Rothschilds and the Guinness’s. Someone of

the very richest, like the Duke of Westminster, continued to derive their

wealth from their land holdings, but they increasingly relied for the wealth

from mineral rights.

Robert

Tombs, The English and their History, 2023 suggests that there were very

significant disparities of wealth. By 1914, 92% of wealth was owned by 10% of

the population.

In the 1860s

the population was around 20M. 4,000 people had incomes over £5,000 per year.

1.4M had around £100. A farm labourer might earn £20. Women workers earned

about half of men’s wages.

There was a

rise in wages from mid century, with a significant

rise in 1873. However in rural areas, wages lagged behind.

Living

standard improved with a fall in the birth rate. The sharpest increase in

spending was tobacco. The mechanically produced Wills Woodbines at 1d for five

were popular from the 1880s to the 1960s. The consumption of alcohol fell

sharply.

Rural society saw fundamental change during the Industrial revolution. The enclosure of the land between about 1720 and 1820 divided up the remaining common land. The agricultural system changed to large scale land ownership. Larger farms wee supported by fertiliser, artificial feed and machinery, tenant farming and wage labour.

By about 1850, about 7,000 people and

institutions owed 80% of land in the UK. 360 estates of over 10,000 acres held

25% of the land in England. About

200,000 tenants of relatively large farms employed over 1.5 million people. A

third of the population was involved directly or indirectly in agriculture.

The agricultural workforce peaked in

the 1850s.

The Corn Laws did not have an

immediate effect, but railways and steamships and later refrigeration, brought

imports of wheat and later livestock from North America, Russia, Canada, and

then Argentina, Australia and New Zealand. In 1880 frozen Australian beef sold

at Smithfield at 5 ½ d a pound. Meat consumption increased. New eating habits

emerged. The delights of fish and chips were born in Oldham in the 1860s.

These new trends led to a Great

Depression in agriculture during the late nineteenth century which

is usually dated from 1873 to 1896, but its impact continued to the Second

World War. Farmers shifted increasingly from cereals towards milk, meat, fruit

and vegetables.

A typical farmer employed 5 or 6

people in 1851, but 2 or 3 in 1901, assisted by mechanisation and new methods.

Rural England lost 4 million people between 1851 and 1911. The repeal of the

Corn Laws in 1846 was only reversed by Britain’s accession to the European

Common Agricultural Policy (“CAP”) in 1973 so that home grown temperate

produce, which was over 90% of consumption in 1830, fell to 40% by 1914, and

rose back to 90% during the period of the CAP.

Cheap food had economic benefits, but

was traumatic alongside the loss of the common land which had traditionally

helped the rural poor. By the nineteenth century, rural workers were dependent

on wages at a time of downward pressure on agricultural prices.

The revolt

of the field in 1872 to 1873, led by Joseph

Arch sought an elevation in the status of the agricultural labourer.

The landlords took some of the strain.

Rents fell by a third between 1870 and 1900. Landlords sought to protect the

political and social influence of their ownership of land and subsidised their

estates, but there was the start of a trend to sell off estates of land.

In Kilton,

there was some relaxation of rents. The local landowner, J T Wharton Esq,

allowed a 50% land rental for the half year because of the Agricultural

depression, which received the thanks of the fraternity of tenant farmers.

It was reported on 13 January 1885 that there was a presentation to J T Wharton

Esq of Skelton Castle. On Monday afternoon, the half yearly rent audit of the

Skelton Estate was held at the Wharton Arms Hotel. Mr E B Hamilton (steward)

presiding, and Mr Robert Stephenson, Vice Chairman. After a splendid dinner,

provided and served up by Mr and Mrs Morgan in first class style, the Chairman

submitted “the Queen and Royal Family”, which was loyally honoured. The

Chairman then proposed the health of Squire Wharton who returned thanks in an

appropriate manner. Mr

C Farndale referred to an event which had taken place among them, as the

farmers had received 50% reduction upon the rent of their arable land for the

past half year. This was stated to have been brought about by the Squire's

compensation for the depreciation of prices as compared to any previous years

since he had become possessed of the property. (Applause). Mr Thomas Petch, on

behalf of the tenants, then presented a beautifully illuminated address in a

gold frame, which read as follows – “To J T Wharton Esq, Skelton Castle. We the

undersigned tenants of your Skelton estate most respectfully beg your

acceptance of this address as a token of our respect and appreciation of the

manner in which you have met us at the present, as also on a former occasion,

under the great agricultural depression, by returning to us 50% of the rent of

the arable land as the half yearly rent audit held January 12th, 1885 and we

earnestly hope you will long be spared in health and strength amongst us.

Martin Farndale, Kilton Hall and Charles Farndale, Kilton Hall; Matthew Young, Claphow, William. Judson, Stank House, John Smith,

Moorsholm Grange, William. Raw, Red Hall, Henry Robinson, Ralph Linus, Cambank, Thomas Petch, Barns Farm, Henry, Atkinson, West

Throttle., Robert Stephenson, Trout Hall.

There was regret at the loss of a

nostalgically remembered rural past, which saw an evolution of new

organisations to protect its legacy. The Commons Preservation

Society was formed in 1865; the English

Dialect Society in 1873; the Society

for the Preservation of Ancient Buildings in 1877; the Folklore Society in 1878; the Lake

District Defence Society in 1883; the Society for the Protection

of Birds in 1889; the National

Trust for Places of Historic Interest or Natural Beauty in 1895; the Folk Song Society in

1898; and the English Folk Dance Society in 1911. The National Trust

Act 1907 allowed the Trust to declare land inalienable. However the trend

for change was unstoppable.

By 1870 John Farndale

was writing about the dramatic

impact of agricultural change on the rural landscape of Kilton.

Realising the profound effect of change on his homeland, he recorded the

events which occurred in his native place, Kilton and the neighbourhood, and

which took place when spinning wheels and woollen wheels were industriously

used by every housewife in the district, and long before there were such things

in the world as Lucifer match boxes and telegraphs, or locomotives built to

run, without horse or bridle, at the astonishing rate of sixty miles an hour.

Kilton had started to realise the impacts of the monstre farm and the Industrial Revolution. And

now dear Farndale, the best of friends must part, I bid you and your little

Kilton along and final farewell. Time was on to all our precious boon, Time is

passing away so soon, Time know more about his vast eternity, World without end

oceans without shore.

In his depictions of rural life in

semi-fictional Wessex, Thomas

Hardy has sometimes been charged with romanticising rural life and

portraying a fictional pastoral landscape. Hardy’s writings capture the end of

an old sense of land as a natural relative and the shift to land as an

exploitable resource.

All around, from

every quarter, the stiff, clayey soil of the arable fields crept up; bare,

brown and windswept for eight months out of the twelve. Spring brought a flush

of green wheat and there were violets under the hedges and pussy-willows out

beside the brook at the bottom of the 'Hundred Acres'; but only for a few weeks

in later summer had the landscape real beauty. Then the ripened cornfields

rippled up to the doorsteps of the cottages and the hamlet became an island in

a sea of dark gold. To a child it seemed that it must always have been so; but

the ploughing and sowing and reaping were recent innovations. Old men could

remember when the Rise, covered with juniper bushes, stood in the midst of a

furzy heath—common land, which had come under the plough after the passing of

the Inclosure Acts. (Lark Rise,

Flora Thomson, Chapter I, Poor

People's Houses: Recalling the Past)

A E Housman’s A Shropshire Lad

1896:

|

Into my heart

an air that kills From yon far

country blows: What are those

blue remembered hills, What spires,

what farms are those? |

That is the

land of lost content, I see it

shining plain, The happy

highways where I went And cannot come

again. |

There was a pastoral air to the music

of Edward Elgar, Frederick Delius, Ralph Vaughan Williams, drawn from folk

traditions of Hungarian, Czech, Finnish and Russian music.

There was a stubborn emotional

attachment to the rural past, but the political will was firmly fixed on an

industrial future.

All

times are times of transition; but the eighteen-eighties were so in

a special sense, for the world was at the beginning of a new era, the

era of machinery and scientific discovery. Values and conditions of life

were changing everywhere. Even to simple country people the change was

apparent. The railways had brought distant parts of the country

nearer; newspapers were coming into every home; machinery was superseding hand

labour, even on the farms to some extent; food bought at shops, much of it from

distant countries, was replacing the home-made and home-grown. Horizons were

widening; a stranger from a village five miles away was no longer looked upon

as 'a furriner'. But, side by side with these changes, the old country

civilization lingered. Traditions and customs which had lasted for

centuries did not die out in a moment. State-educated children still

played the old country rhyme games; women still went leazing,

although the field had been cut by the mechanical reaper; and men and boys

still sang the old country ballads and songs, as well as the latest music-hall

successes. So, when a few songs were called for at the 'Wagon and Horses', the

programme was apt to be a curious mixture of old and new. (Lark

Rise, Flora Thomson, Chapter IV, At the

‘Wagon and Horses’)

Machinery was

just coming into use on the land.

Every autumn appeared a pair of large traction engines, which, posted

one on each side of a field, drew a plough across and across by means of a

cable. These toured the district under their own steam for hire on

the different farms, and the outfit included a small caravan, known as 'the

box', for the two drivers to live and sleep in. In the 'nineties, when they

had decided to emigrate and wanted to learn all that was possible about

farming, both Laura's brothers, in turn, did a spell with the steam plough, horrifying

the other hamlet people, who looked upon such nomads as social outcasts.

Their ideas had not then been extended to include mechanics as a class apart

and they were lumped as inferiors with sweeps and tinkers and others whose work

made their faces and clothes black. On the other hand, clerks and salesmen of

every grade, whose clean smartness might have been expected to ensure respect,

were looked down upon as 'counter-jumpers'. Their recognized world was made

up of landowners, farmers, publicans, and farm labourers, with the butcher, the

baker, the miller, and the grocer as subsidiaries.

Such machinery as

the farmer owned was horse-drawn

and was only in partial use. In some fields a horse-drawn drill would sow the

seed in rows, in others a human sower would walk up

and down with a basket suspended from his neck and fling the seed with both

hands broadcast. In harvest time the mechanical reaper was already a familiar

sight, but it only did a small part of the work; men were still mowing with

scythes and a few women were still reaping with sickles. A thrashing machine on

hire went from farm to farm and its use was more general; but men at home still

thrashed out their allotment crops and their wives' leazings

with a flail and winnowed the corn by pouring from sieve to sieve in the wind.

(Lark Rise, Flora Thomson, Chapter

III, Men

Afield)

The route to

modern farming

…

Gale Bank Farm early twentieth

century Gale

Bank Farm in about 1960