|

|

Agriculture

Agriculture has always been the heart of the Farndale communities

|

|

Dates are in red.

Hyperlinks to other pages are in dark blue.

Headlines are in brown.

References and citations are in turquoise.

Context and local history are in purple.

This page has the following sections:

·

Introduction

·

The

Farndale farmers

·

Farndale

agricultural workers

·

Agriculture

in the Middle Ages

·

Serfdom

·

Tenancy

·

Sixteenth

Century

·

Seventeenth

Century

·

Eighteenth

Century

·

Farming

methods

·

Rural

Life around the North York Moors

·

Agricultural

Labourers

·

Agricultural

Change

·

The

path to modern farming

·

Links,

texts and books

Introduction

Whilst of course the family in the

twenty first century comprises a large range of folk, many now living in urban

areas, the historical family is rooted in the land and agriculture. Until the

industrial revolution, most of the British population was rural and horizons

were small.

Our family’s recorded history began with

the clearing of the land in Farndale by about 1230. There was pastureland

in Farndale by at least 1225.

Even by 1280 there were folk such as William

the Smith of Farndale who specialised in supportive trades. By 1338 people

such as Walter

de Farndale, later Vicar of Haltwhistle, Lazonby and

Chelmsford, and William

Farndale later Vicar of Doncaster, had become chaplains. By 1363, Johannis

de Farndale had moved to York and was working as a saddler in an urban

setting, and his family would stay there for generations, his grandson being a

butcher. There were large numbers of the family who joined the Armed Forces. There were several

policemen.

However the bulk of the family remained

in a rural setting, working for others on the land, and occasionally becoming

tenant farmers themselves.

Indeed even as the family moved its

centre of gravity to the area of Cleveland when Nicholas

Farndale’s family moved there in perhaps about 1565, the focus remained

rural for another four centuries. It is true that there were groups of the

family who moved to the larger urban port town of Whitby

where many turned to the sea for work,

and when the industrial revolution came, others found work in the mines, whilst some large

groups of the family moved to urban centres such as Leeds

and Bradford, particularly to work in the textile

industry. However the bulk of the family continued to work in agricultural

roles and mostly within a comparatively small radius of not more than about ten

miles around Guisborough.

This web page tells the story of the

Farndales and agriculture.

The Farndale farmers

The Farndales who became tenant farmers

included John Farndale, “Old Farndale of Kilton” (FAR000143);

William Farndale, Farmer of Craggs (FAR000146);

William Farndale (FAR00152)

perhaps for a time; John Farndale (FAR00167); John

Farndale (FAR00177);

William Farndale (FAR00183);

Elias Farndale of Ampleforth (FAR00184); John

Farndale, for a time before he turned to trade and agency and became a writer (FAR00217); Matthew

Farndale, who then emigrated to Australia where he became rooted to the land of

Victoria (FAR00225);

John Farndale (FAR00230);

Martin Farndale of Kilton (FAR00236); John

Farndale (FAR00240);

John Farndale of Whitby (FAR00244); George

Farndale of Kilton (FAR00252); Elias

Farndale of Ampleforth (FAR00274);

Charles Farndale of Kilton Hall Farm (FAR00341);

George Farndale of Brotton (FAR00350C);

Martin Farndale of Tidkinhow (FAR00364);

Matthew Farndale of Craggs (FAR00383);

William Farndale of Gillingwood Hall, Richmond (FAR00531); John

William Farndale of Danby (FAR00537);

John Farndale at Tidkinhow (FAR00553); Martin

Farndale, cattle farmer of Alberta (FAR00571);

George Farndale, farmer at Three Hills, Alberta (FAR00588);

Catherine Farndale and the Kinseys in Alberta (FAR00601);

Herbert Farndale of Craggs (FAR00652);

Grace Farndale and Howard Holmes (FAR00659);

William Farndale of Thirsk (FAR00665);

Alfred Farndale of Wensleydale (FAR00683) and

Geoff Farndale of Wensleydale (FAR00922).

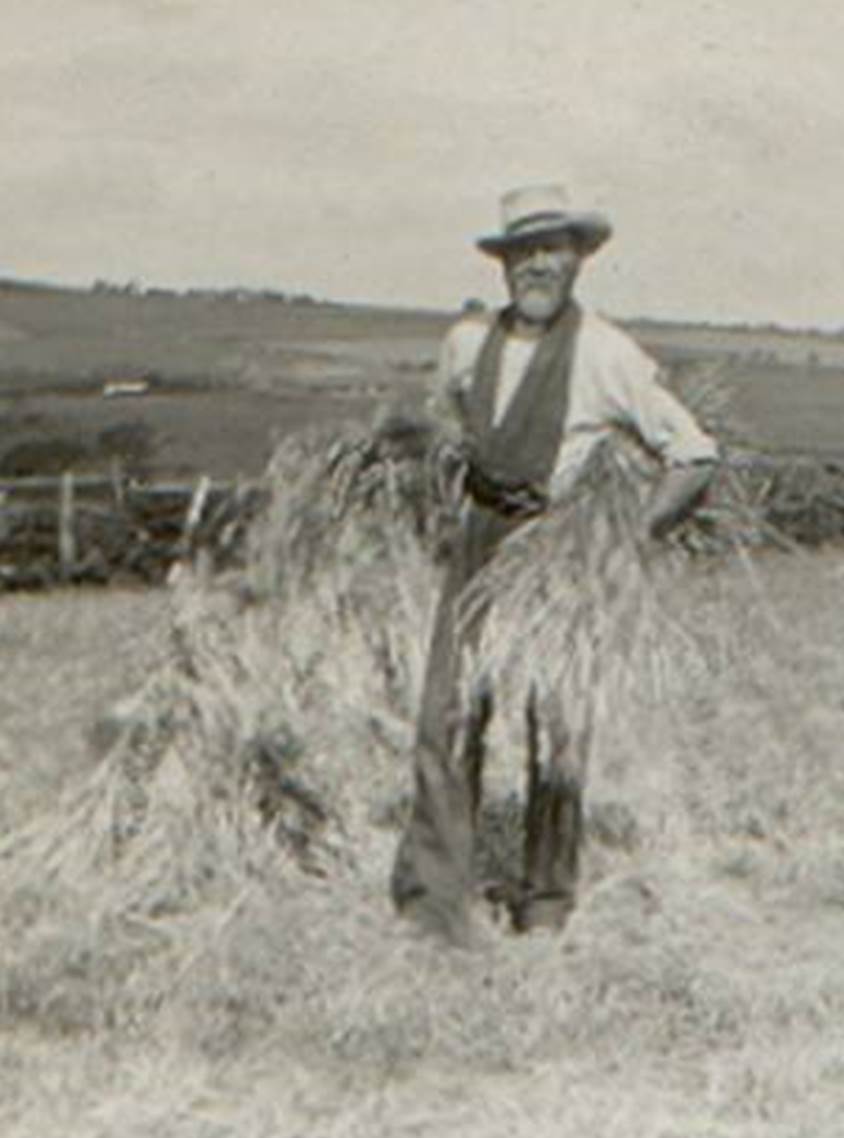

Martin

Farndale

at Tidkinhow about 1920

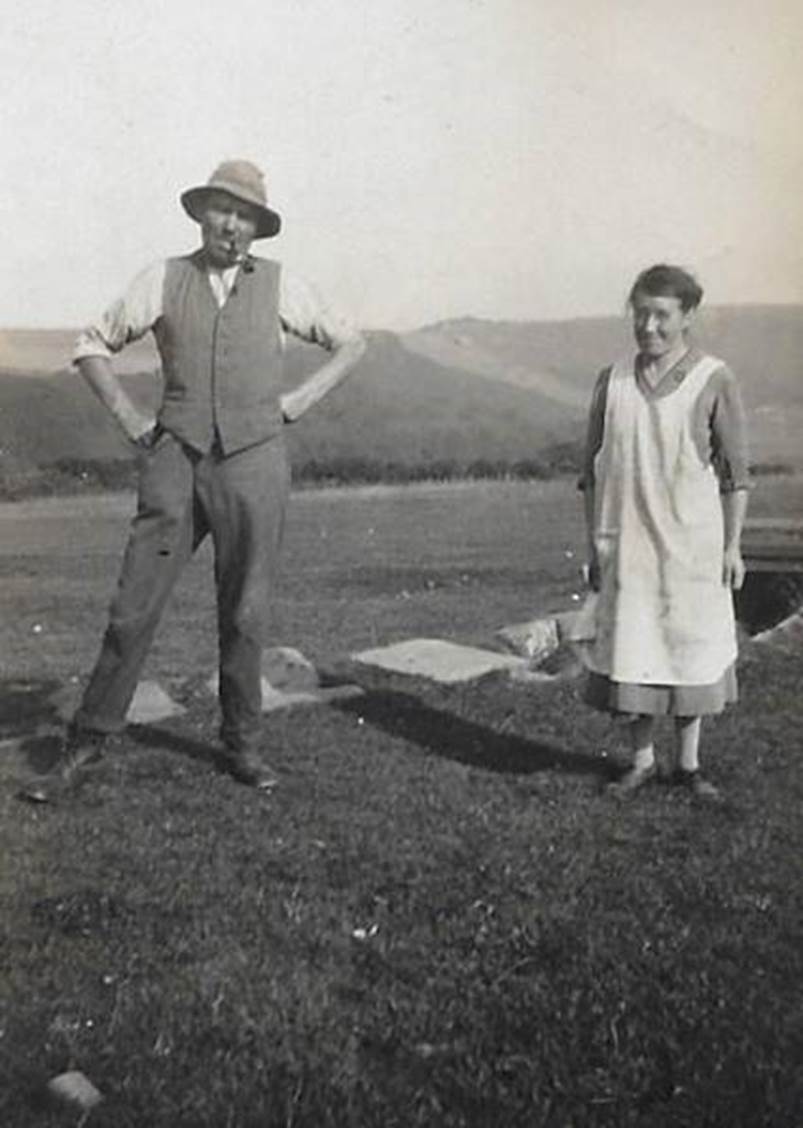

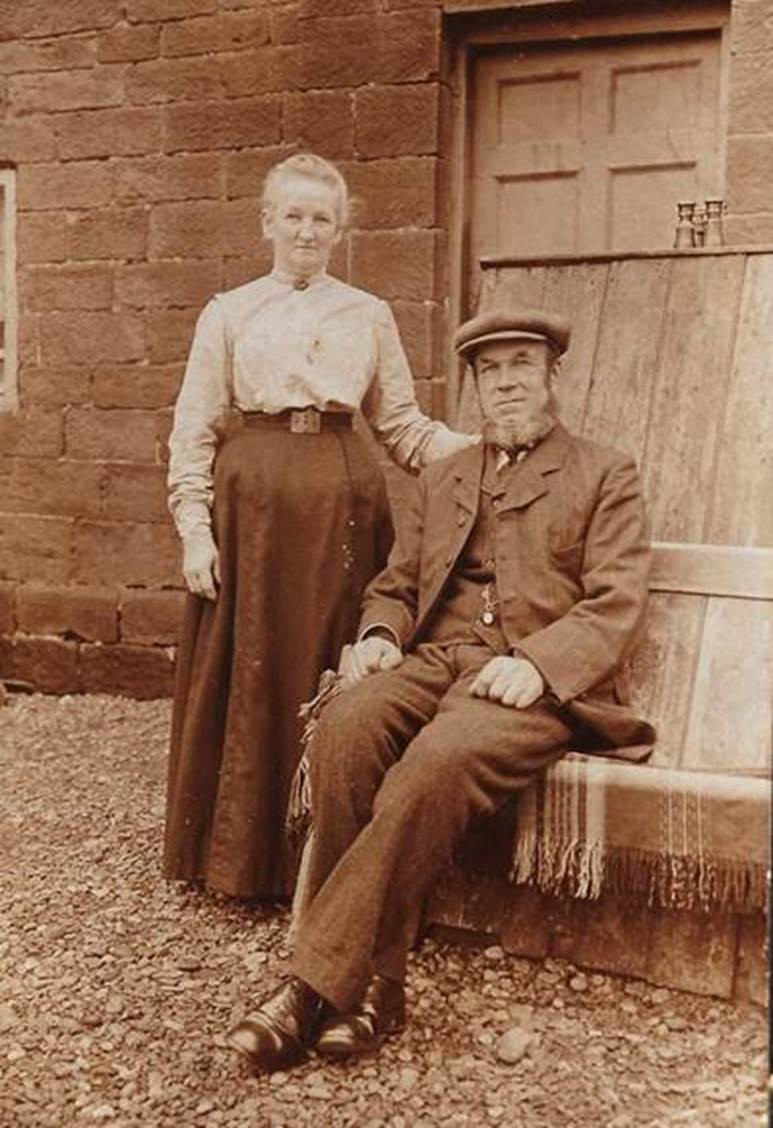

John

Farndale

at Tidkinhow about 1937 Matthew

Farndale and Mary Ann

at Craggs Hall Farm, about 1900

George

Farndale,

of Kilton Hall Farm, about 1925

The Farndale Farm

Labourers

The

lives of many members of the family through time, was a life of work for others

on the fields. Many of the farmers listed above spent periods of time working

for others on the land before they acquired land to farm for themselves.

Examples of those who worked as ‘agricultural labourers’ included George

Farndale of Brotton (FAR00215); Jethro Farndale of Ampleforth (FAR00218); Wilson Farndale (FAR00227); Henry Farndale of Great Ayton (FAR00229); William Farndale of Brotton (FAR00243); William Farndale of Whitby (FAR00257); William Farndale of Seltringham (FAR00258); John Farndale of Eskdaleside (FAR00262); Martin Farndale of Kilton (FAR00264); William Farndale of Great Ayton (FAR00283); Joseph Farndale of Whitby (FAR00285); William Farndale of Ampleforth (FAR00286); John Farndale of Kilton (FAR00287); Richard Farndale of Great Ayton (FAR00288); Matthew Farndale of Coatham (FAR00297); John Farndale (FAR00305); John George Farndale before he

emigrated to Ontario (FAR00337); William Farndale of Loftus (FAR00378); Thomas Farndale of Ampleforth (FAR00474) and George Farndale of Loftus (FAR00627).

Agriculture in the Middle Ages

1086

By 1086, Farndale was an unknown place in thick

forested land. However there was a tiny settlement which comprised ten

villagers, one priest, two ploughlands, two lord’s plough teams, three men’s

plough teams, a mill and a church around the Chucrh

of St Gregory in Chirchebi, now at Kirkdale. It had been a community under

Orm’s suzerainty since at least 1055 and no doubt well before that.

Medieval

land units

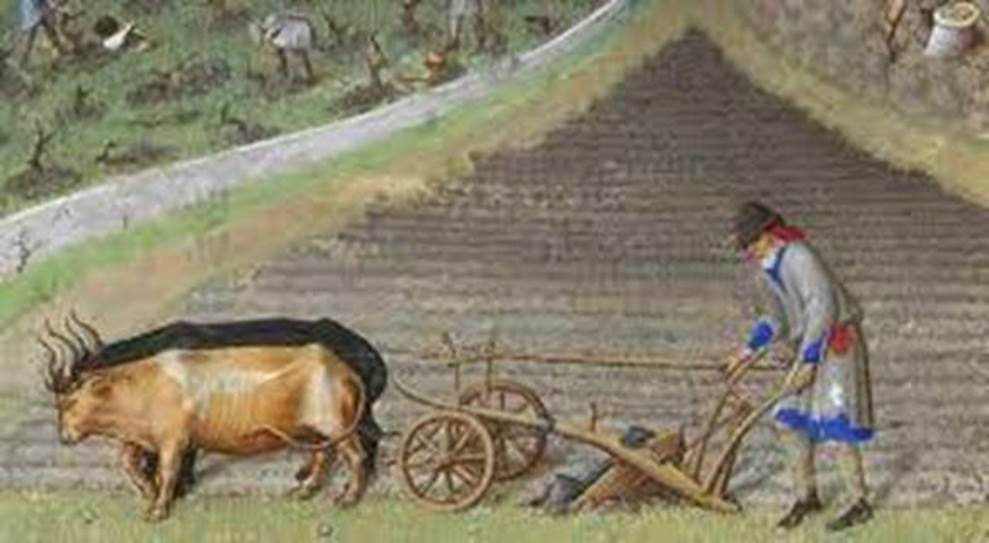

The rod

is a historical unit of length equal to 5+1/2 yards. It may have originated

from the typical length of a mediaeval ox-goad. There are 4 rods in one chain.

The furlong

(meaning furrow length) was the distance a team of oxen could plough without

resting. This was standardised to be exactly 40 rods or 10 chains.

An acre

was the amount of land tillable by one man behind one team of eight oxen in one

day. Traditional acres were long and narrow due to the difficulty in turning

the plough and the value of river front access.

An oxgang

was the amount of land tillable by one ox in a ploughing season. This could

vary from village to village, but was typically around 15 acres.

A virgate

was the amount of land tillable by two oxen in a ploughing season.

A carucate

was the amount of land tillable by a team of eight oxen in a ploughing season.

This was equal to 8 oxgangs or 4 virgates.

After

his victory he visited York and Pickering. Henry I redistributed land from Robert

Curtose’s supporters, including Robert de Stuteville to his new men, including Nigel d’Albini, ancestor of the Mowbray family and Robert de Brus.

The

new barons resettled the landscape with freeholders, villeins and cottagers.

The bondsmen were settled as unfree men, sometimes referred to as serfs or

villeins. The Norman, Fleming and Breton landowners formed a new ruling class

of manor lords.

Freemen were sometimes created in return

for service. Roger de Mowbray settled freeholds near Thirsk on his

butler, usher, cook, baker and musicians (John

Rushton, The History of Ryedale, 2003, 49).

The Norman conquest broke the continuity

of ploughing for a period, but then there was a recovery and the old fields

were quickly restored.

At this time settlements of bondsmen and

villeins worked two or three adjoining fields, which were each sub divided into

a dozen or so furlongs. Each furlong was a section of the larger field usually

about 5 to 10 yards wide. The fields were cultivated collectively but each

strip was cropped by the tenant. Two oxgangs were quite commonly held by a

villein.

The villages may well have been laid

anew by the Normans. Often the lord’s manor house was at the end. Nearer to the

moors, large greens with ponds, provided a source for watering stock, as at Fadmoor.

(John Rushton, The History of Ryedale, 2003, 58-59).

With the recovery of agriculture, manors

started to invest in mills to grind grain – these were a major investment, but

were a means for a lord to gain an income from their lands.

Some land was not included within the

system, of oxgangs and new thwaites (clearings) appeared including Duvansthwaite at Farndale. Sometimes fringe land near the main

fields was cleared, often called ofnames.

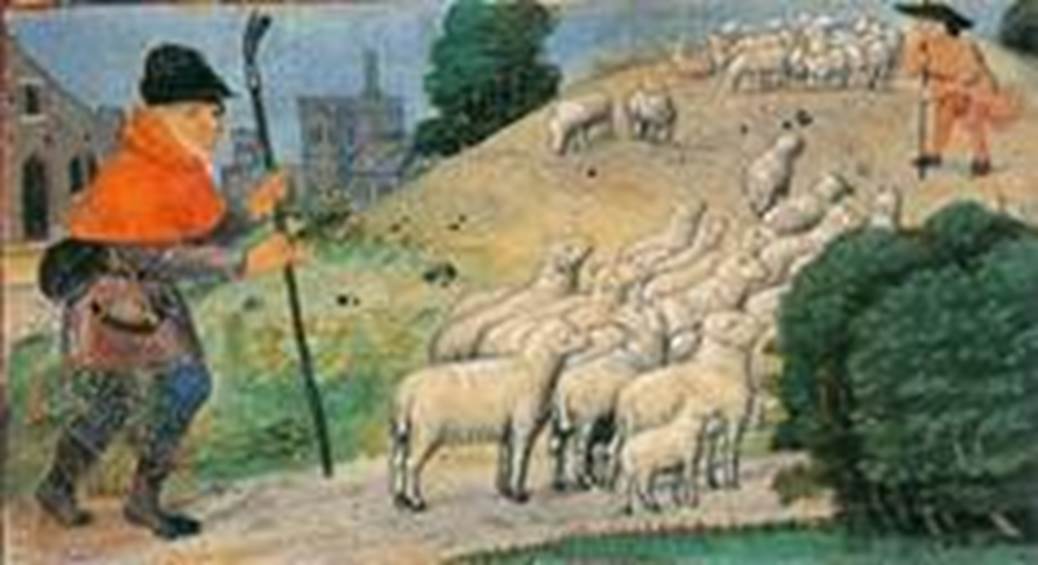

Significant

land grants were given to the monasteries. Rievaulx soon had a great swathe of

properties, throughout Ryedale and stretching to Teesmouth

and Filey. At its peak it had 140 monks and 400 lay brothers. They tended to

site their granges away from villages. Monastic farms were a separate economic

force. The sheep grange was dominant in Yorkshire with many examples, including

at Farndale,

of donations of rights to pasture a fixed number of sheep.

Road systems

The

agricultural areas were sometimes connected by the King’s Highways,

which fell under legal protection and generally linked to the market towns.

There were a few long distance routes, often called great ways or magna

vias. A magna via through Huttons

Ambo led to York. Routes across the high moors were

sometimes called riggways. There were a small

number of bridges generally on lower ground, for instance at Kirkham. More

local routes often formed a start of routes in the immediate neighbourhood,

whose pattern changed between summer and winter. There were few signs or

markers, but occasionally crosses would mark a junction, such as Whinny cross

on Yearsley moor.

Tolls

may have been taken, though locally they were not often recorded and might have

not been worth it for the lack of traffic. Gatelaw

was a road tax levied in Pickering Forest.

Early rural industry was focused on corn

milling. Some castles and monasteries had more specialised industries and most

of them had bakehouses and breweries. There is some evidence of medieval

pottery, for instance pottergates of Pickering

and Gilling.

Corn mills inevitably belonged to the

manor. A water corn mill was a substantial investment, but provided a lord with

a steady source of income.

Occasionally windmills were found on low

flat lands.

Village fulling mills were sited on

streams, including at Farndale.

The number of village blacksmiths

suggests the extraction of ironstone at some scale. Barned arrow rents suggest

than iron was readily available in Farndale.

1233

The Abbot granted that if the cattle of

Nicholas or of his heirs or of his men at Kikby, Fademor, Gillingmor or Farndale, hereafter enter upon the common of the said

wood and pasture of Houton, Spaunton and Farendale, they shall have free way in

and out without ward set; provided they do not tarry in the said pasture.’ 17th

year of the Reign of Henry III. (Yorkshire

Fines Vol LXVII) (FAR00007)

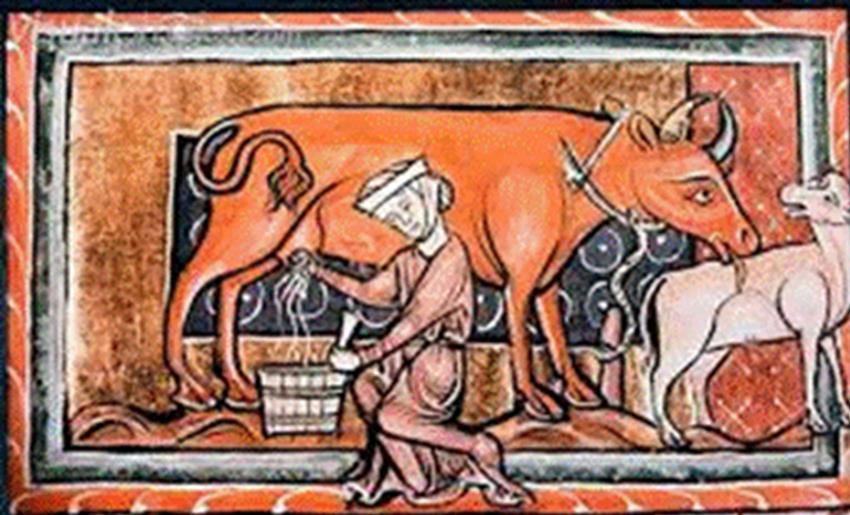

Peasant woman milking a cow, mid Thirteenth Century

1236

The Commons Act allowed manorial lords to

enclose common land for their own use.

1270

John

the shepherd of Farndale must have been a herdsman by about 1270.

By 1276 there was perhaps 545 acres of cultivated land

in Farndale.

By 1282 there was perhaps 768 acres in cultivation in

Farndale.

‘In a certain dale called Farndale there are

fourscore and ten natives, not tenants by bovate of land, but by, more and

less, whose rents are extended at £38 8s 8d. Each of whom pays at Martinmas two

strikes of nuts, four of the aforesaid tenants only being excepted from the

rent of nuts. Price of nuts as above. Sum of nuts, two and a half quarters and

one strike. Sum in money 43s 9d of whom four score and five shall be harrowing

at Lent according to the size of his holding, that is, for each acre of his own

land a 1/2d worth of harrowing. Those works are extended at 29s 4d. They ought

to be talliated and given pannage as above.

The sum of £1 10s 1d. There are there three tenants in waste places

called Arkeners and Swenekelis, holding ten acres of land, an paying

10s a year and giving nuts worth 18d. The harrowing is extended at 5d. They are

serfs as the aforesaid ones of Farndale. Sum 11s 11d.’

By this time there were some 800,000 oxen and

400,000 horses in England, which enhanced the power of labour some six or seven

times.

Wool was the most significant export, with some

12m fleeces exported each year.

As the population spread into less settled

regions, with poorer soils needing more labour, a collective open field system

spread. Each vill was divided into two or

three huge open fields. One field was left fallow. The fields were ploughed in

a ridge and farrow pattern, with the undulatios

still visible today, as at Kilton. Households would own strips of land in each

field, but the use of the fields was well controlled. This open field system

reached its peak in the fourteenth century.

Most

people lived in a village, worshipped in a parish and worked in a manor (Robert

Tombs, The English and their History, 2023, 92).A lord might

possess many manors, or one. A manor operated as a large collective.

Senior

villagers held offices, such as constable or church warden.

About 2/3

of manorial tenants were not free in 1200, but were villeins or serfs. Villeins

usually paid part of their rent in labour. Strictly, they could not leave the

manor without permission. They could be sold.

The

common law gradually extended to all free men and even unfree men had certain

rights and could even pass on their land to their heirs.

At a

local level, the Lord was the pinnacle of local society and the political,

cultural and economic focal point. Norman feudalism only lasted for about a

century and it was replaced by a primitive system of land tenure. Over time

this was increasingly paid for by money rather than service. The lord provided

land, justice and protection. In return the lord expected obedience and

deference; support to profit from the land; and military assistance when

necessary.

By the

1300s landlords comprised about 20,000 individuals and 1,000 institutions (Robert Tombs, The English and their History, 2023,

94).

1301

By 1301, there was a sizeable agricultural community

in Farndale, with 39 names associated with the place and the identification of

farmed settlements which can still be identified today, including Wakelevedy’ (Wake Lady Green), ‘Westgille’

(West Gill), Monkegate (Monket

House) and ‘Elleshaye (Eller House).

1310

‘In 1310, 20 oxen the property of Nicholas the

parker, worth 8s, 6 oxen and 3 stirks of William in the horn worth £1 9s, a cow

and a stirk of Hugh Laverock 4s 8d and 6 oxen of William Stibbing

de Farndale…….’

1289

In

the second half of the thirteenth century there was a disastrous fall in global

temperatures, which led to a succession of storms, frosts and droughts. The

Great Strom of 1289 ruined harvests across the country.

1290

Real

wages fell by about 20% between 1290 and 1350. Wars in Asia Minor from the

1250s and wear with France disrupted trade.

1309

The

Thames froze in 1309 to 1310.

1315

In

1315 to 1316, two years of continual rain ruined harvests. A great famine

across Europe lasted for 7 years.

These

were years of perhaps the worst economic disaster that England has faced. Half

a million people died of hunger and disease.

1342

Water

levels rose in the lowlands and the banks at Rillington

were raised in 1342 by the monks of Byland Abbey.

1356

The

tidal rivers of the Humber rose 4 feet above average in 1356.

Villein

services were being replaced by money dues. Villeins were replaced by

husbandmen and paid rents.

1349

In

1349 came the Black Death. Indeed the plague attacked the population four times

in thirty years and became endemic for three centuries.

The

reduced population eased the demand on arable crops, but the market still

sought mutton and beef, wool and hides. In sizeable estates, fields could be

allocated for rearing and fattening. Agriculture became more complex.

Life as a Medieval Farmer

Many

of the folk living in a late medieval village would have had a one room house.

The size of the house, the way it was built, and the contents reveal the

simplicity of the home. The villagers provided most of what they needed for

themselves and their daily routine was governed by the seasons.

Reconstruction from the Ryedale Folk Museum

The

family lived at one end of the building and the animals, kept for milk, meat

and wool, at the other. The hearth, where the meals were cooked, was the centre

of the home. The smoke would escape through the thatch.

The

cottage was also used to store tools and those used for raking, hoeing,

scything and chopping varied little over centuries. Hay and grain, needed over

winter, were stored in the loft and salted meats hung from the roof beams.

The most precious possessions were

stored in wooden chests. All the furniture could be easily moved to allow the

room to be used for other purposes.

Serfdom

Further

research required.

Tenancy

By the late

Victorian period, Lark Rise, Flora Thomson, Chapter

I, Poor People's Houses : The first

charge on the labourers' ten shillings was house rent.

Most of the cottages belonged to small tradesmen in the market town and the

weekly rents ranged from one shilling to half a crown. Some labourers

in other villages worked on farms or estates where they had their cottages rent

free; but the hamlet people did not envy them, for 'Stands to

reason,' they said, 'they've allus got to do just

what they be told, or out they goes, neck and crop, bag and baggage.' A

shilling, or even two shillings a week, they felt, was not too much to pay for

the freedom to live and vote as they liked and to go to church or chapel or

neither as they preferred.

Sixteenth Century

Seventeenth Century

Eighteenth century

Enclosures spread rapidly around Malton,

for instance at Huttons

Ambo

and Appleton le Street.

(Robert Tombs, The English and their History, 2023,

253).

Local power depended on deference, but

by the early eighteenth century, deference had to be earned. There was a

growing confederacy between those working on the land who increasingly saw the

Squire’s property as fair booty and who colluded to help each other against

punishment.

Victorian period

This was a period of exponential growth

in the production of coal, pig iron and the consumption of raw cotton, dwarfing

the equivalent in France and Germany.

The growth in non

agricultural production meant the population had to be fed by imports.

Since 1822 Britain’s balance of trade has remained permanently in deficit. It

had to be balanced by invisible earnings from banking, insurance and shipping,

and returns from foreign investments.

This brought new kinds of wealth

(commerce, manufacturing, food and drink, tobacco) and new wealthy families,

like the Rothschilds and the Guinness’s. Someone of the very richest, like the

Duke of Westminster, continued to derive their wealth from their land holdings,

but now because they benefitted from mineral rights.

There were very significant disparities

of wealth:

By 1914, 92% of wealth was owned by 10%

of the population.

In the 1860s:

·

The

population was around 20M.

·

4,000

people had incomes over £5,000 per year.

·

1.4M

had around £100.

·

A

farm labourer might earn £20.

·

Women

workers earned about half of men’s wages.

There was a rise in wages from mid century, with a significant rise in 1873.

However in rural areas, wages lagged

behind.

Living standard improved with a fall in

the birth rate. The sharpest increase in spending was tobacco – the

mechanically produced Wills Woodbines at 1d for five were popular from the

1880s to the 1960s. The consumption of alcohol fell sharply.

(Robert

Tombs, The English and their History, 2023, 477 to 492).

Farming methods

Further

research required.

Rural Life around the North York Moors

Further

research required.

…

There is a manufacturer of wood burning

stoves in Pickering which keeps up the tradition, and they have a Farndale Stove!

…

Supplying

water to a nineteenth century house could be

a challenge. Few of the poorer houses had indoor taps and people relied upon

communal supplies such as rivers, wells and springs. Two buckets might be

carried with a yoke.

Local

rural communities would have relied upon local businesses

such as blacksmiths and iron foundries, such as these,

reconstructed at the Ryedale Folk Museum near Farndale today.

Agricultural Labourers

In

the late Victorian period …

Lark Rise, Flora Thomson,

Chapter III, Men Afield: Very early in the morning,

before daybreak for the greater part of the year, the hamlet men would throw

on their clothes, breakfast on bread and lard, snatch the dinner-baskets

which had been packed for them overnight, and hurry off across fields and over

stiles to the farm. Getting the boys off was a more difficult matter. Mothers

would have to call and shake and sometimes pull boys of eleven or twelve out of

their warm beds on a winter morning. Then boots which had been drying inside

the fender all night and had become shrunk and hard as boards in the process

would have to be coaxed on over chilblains. Sometimes a very small boy would

cry over this and his mother to cheer him would remind him that they were only

boots, not breeches. 'Good thing you didn't live when breeches wer' made o' leather,' she would say, and tell him about

the boy of a previous generation whose leather breeches were so baked up in

drying that it took him an hour to get into them. 'Patience! Have patience, my

son', his mother had exhorted. 'Remember Job.' 'Job!' scoffed the boy. 'What

did he know about patience? He didn't have to wear no leather breeches.'

The elders stooped, had gnarled and

swollen hands and walked badly, for they felt the

effects of a life spent out of doors in all weathers and of the rheumatism

which tried most of them.

The men's incomes were the same to a

penny; their circumstances, pleasures, and

their daily field work were shared in common; but in themselves they

differed; as other men of their day differed, in country and town. Some

were intelligent, others slow at the uptake; some were kind and helpful, others

selfish; some vivacious, others taciturn. If a stranger had gone there looking

for the conventional Hodge, he would not have found him.

Their favourite virtue was endurance.

Not to flinch from pain or hardship was their ideal. A man would say, 'He says,

says he, that field o' oo-ats's got to come in afore

night, for there's a rain a-comin'. But we didn't

flinch, not we! Got the last loo-ad under cover by midnight. A'moost too fagged-out to walk home; but we didn't flinch.

We done it!' Or,'Ole bull he comes for me, wi's head down. But I didn't flinch. I ripped off a bit o'

loose rail an' went for he. 'Twas him as did th' flinchin'. He! he!' Or a

woman would say, 'I set up wi' my poor old mother six

nights runnin'; never had me clothes off. But I

didn't flinch, an' I pulled her through, for she didn't flinch neither.' Or a

young wife would say to the midwife after her first confinement, 'I didn't

flinch, did I? Oh, I do hope I didn't flinch.'

The farm was large,

extending far beyond the parish boundaries; being, in fact, several farms,

formerly in separate occupancy, but now thrown into one and ruled over by

the rich old man at the Tudor farmhouse. The meadows around the farmstead

sufficed for the carthorses' grazing and to support the store cattle and a

couple of milking cows which supplied the farmer's family and those of a few of

his immediate neighbours with butter and milk. A few fields were sown with

grass seed for hay, and sainfoin and rye were grown and cut green for cattle

food. The rest was arable land producing corn and root crops, chiefly wheat.

Around the farmhouse were grouped the

farm buildings; stables for the great stamping

shaggy-fetlocked carthorses; barns with doors so wide and high that a

load of hay could be driven through; sheds for the yellow-and-blue

painted farm wagons, granaries with outdoor staircases; and sheds for

storing oilcake, artificial manures, and agricultural implements. In the

rickyard, tall, pointed, elaborately thatched ricks stood on stone

straddles; the dairy indoors, though small, was a model one; there was a

profusion of all that was necessary or desirable for good farming.

The field names

gave the clue to the fields' history. Near the farmhouse, 'Moat Piece',

'Fishponds', 'Duffus [i.e. dovehouse] piece',

'Kennels', and 'Warren Piece' spoke of a time before the Tudor house took the

place of another and older establishment.

One name was as good as another to most

of the men; to them it was just a name and meant nothing. What mattered to

them about the field in which they happened to be working was whether the

road was good or bad which led from the farm to it; or if it was comparatively

sheltered or one of those bleak open places which the wind hurtled through,

driving the rain through the clothes to the very pores; and was the soil easily

workable or of back-breaking heaviness or so bound together with that 'hemmed'

twitch that a ploughshare could scarcely get through it.

There were usually three or four

ploughs to a field, each of them drawn by a team of three horses,

with a boy at the head of the leader and the ploughman behind at the

shafts. All day, up and down they would go, ribbing the pale stubble with

stripes of dark furrows, which, as the day advanced, would get wider and nearer

together, until, at length, the whole field lay a rich velvety plum-colour.

The labourers worked hard and well

when they considered the occasion demanded it and kept up a good steady pace at

all times. Some were better workmen than others, of course; but the

majority took a pride in their craft and were fond of explaining to an outsider

that field work was not the fool's job that some townsmen considered it. Things

must be done just so and at the exact moment, they said; there were ins and

outs in good land work which took a man's lifetime to learn. A few of less

admirable build would boast: 'We gets ten bob a week, a' we yarns every penny

of it; but we doesn't yarn no more; we takes hemmed good care o' that!' But at

team work, at least, such 'slack-twisted 'uns' had to

keep in step, and the pace, if slow, was steady.

Lark

Rise, Flora Thomson, Chapter XV, Harvest Home:

After the mowing and reaping and binding

came the carrying, the busiest time of all. Every man and boy put his best foot

forward then,

Harvest home! Harvest home!

Merry, merry, merry harvest home!

Our bottles are empty, our barrels won't

run,

And we think it's a very dry harvest

home.

the farmer came out, followed by his

daughters and maids with jugs and bottles and mugs, and drinks were handed

round amidst general congratulations.

the harvest home dinner everybody

prepared themselves for a tremendous feast

Agricultural change

Rural society was in decline during the Industrial revolution.

The

enclosure of the land between about 1720 and 1820 divided up the remaining

common land. The agricultural system changed to large scale land ownership

(larger farms supported by fertiliser, artificial feed and machinery), tenant

farming and wage labour.

By about

1850, about 7,000 people and institutions owed 80% of land in the UK. 360

estates of over 10,000 acres held 25% of the land in England. About 200,000 tenants of relatively large

farms employed over 1.5M people. A third of the population was involved

directly or indirectly in agriculture.

The

agricultural workforce peaked in the 1850s.

The Corn

Laws did not have an immediate effect, but railways and steamships and later

refrigeration, brough imports of wheat and later livestock from North America,

Russia, Canada, and then Argentina, Australia and New Zealand. In 1880 frozen

Australian beef sold at Smithfield at 5 ½ d a pound. Meat consumption

increased. New eating habits emerged – fish and chips were born in Oldham in

the 1860s.

These new

trends led to a Great Depression in agriculture during

the late nineteenth century which is usually dated from 1873 to 1896.

Farmers

shifted from cereals towards milk, meat, fruit and vegetables.

A typical

farmer employed 5 or 6 people in 1851, but 2 or 3 in 1901, assisted by

mechanisation and new methods. Rural England lost 4M people between 1851 and

1911. The repeal of the Corn Laws in 1846 was only revered by Britain’s

accession to the European Common Agricultural Policy (“CAP”) in 1873 so

that home grown temperate produce was over 90% of consumption in 1830, fell to

40% by 1914, and rose back to 90% during the period of the CAP.

Cheap

food had economic benefits, but was traumatic alongside the loss of the common

land which had traditionally helped the rural poor.

By the

nineteenth century, rural workers were dependent on wages at a time of downward

pressure on agricultural prices.

The revolt

of the field

in 1872 to 1873, led by Joseph

Arch

sought an elevation in the status of the agricultural labourer.

The landlords took some of the strain –

rents fell by a third between 1870 and 1900. Landlords sought to protect the

political and social influence of their ownership of land and subsidised their

estates, but there was the start of a trend to sell off estates of land.

There remained a sentiment of rural

England, but no political will to protect it:

·

The

Commons

Preservation Society

1865

·

The

English

Dialect Society

1873

·

The

Society

for the Preservation of Ancient Buildings 1877

·

The

Folklore Society 1878

·

The

Lake

District Defence Society

1883

·

The

Society

for the Protection of Birds

1889

·

The

National

Trust for Places of Historic Interest or Natural Beauty 1895

·

The

Folk

Song Society

1898

·

The

English Folk Dance Society 1911

·

The

National

Trust Act 1907

allowed the Trust to declare land inalienable.

In many cases, these new organisations

were largely driven by the provision of amenity for town dwellers.

(Robert

Tombs, The English and their History, 2023, 486 to 489).

By 1870 John

Farndale

was writing about the dramatic impact of

agricultural change on the rural landscape of Kilton. Realising the profound effect of

change on his homeland, he has recorded the events which occurred in his

native place, Kilton and the neighbourhood, and which took place when spinning

wheels ad woollen wheels were industriously used by every housewife in the

district, and long before there were such things in the world as Lucifer match

boxes and telegraphs, or locomotives built to run, without horse or bridle, at

the astonishing rate of sixty miles an hour (Guide

to Saltburn by the Sea and the Surrounding District, John Farndale, 1870).

Kilton had started to realise the impacts of the "monstre

farm" and the Industrial Revolution. "And now dear Farndale, the

best of friends must part, I bid you and your little Kilton along and final

farewell. Time was on to all our precious boon, Time is passing away so soon,

Time know more about his vast eternity, World without end oceans without sure."

In his depictions of rural life in

semi-fictional Wessex, Thomas

Hardy

has sometimes been charged with romanticising rural life and portraying the

pastoral instead of the real. His characters frequently inhabit agricultural

communities, which form the basis of their lives and livelihoods. In tension

with the pastoral, romanticised village is the recognition of agriculture as a

capitalist venture: Hardy’s writings capture the end of the old sense of land

as a natural relative and the shift to land as an exploitable resource.

A E Housman’s A

Shropshire Lad

1896:

X

Into my heart an air that kills

From yon far country blows:

What are those blue remembered hills,

What spires, what farms are those?

That is the land of lost content,

I see it shining plain,

The happy highways where I went

And cannot come again.

There was a pastoral air to the music of

Edward Elgar, Frederick Delius, Ralph Vaughan Williams, but it was not as

richly pastoral as Hungarian, Czech, Finnish and Russian music. It was rooted

in a world culture and even Elgar drew on European folk traditions.

There was a stubborn emotional

attachment to the rural past, but the political will was firmly fixed on an

industrial future.

Lark

Rise, Flora Thomson, Chapter IV, At the ‘Wagon and Horses’:

All

times are times of transition; but the eighteen-eighties were

so in a special sense, for the world was at the beginning of a new era,

the era of machinery and scientific discovery. Values and conditions of

life were changing everywhere. Even to simple country people the change was

apparent. The railways had brought distant parts of the country

nearer; newspapers were coming into every home; machinery was superseding hand

labour, even on the farms to some extent; food bought at shops, much of it from

distant countries, was replacing the home-made and home-grown. Horizons were

widening; a stranger from a village five miles away was no longer looked upon

as 'a furriner'. But, side by side with these changes, the old country

civilization lingered. Traditions and customs which had lasted for

centuries did not die out in a moment. State-educated children still

played the old country rhyme games; women still went leazing,

although the field had been cut by the mechanical reaper; and men and boys

still sang the old country ballads and songs, as well as the latest music-hall

successes. So, when a few songs were called for at the 'Wagon and Horses', the

programme was apt to be a curious mixture of old and new.

Lark Rise, Flora Thomson, Chapter III, Men Afield: Machinery

was just coming into use on the land.

Every autumn appeared a pair of large traction engines, which, posted

one on each side of a field, drew a plough across and across by means of a

cable. These toured the district under their own steam for hire on

the different farms, and the outfit included a small caravan, known as 'the

box', for the two drivers to live and sleep in. In the 'nineties, when they

had decided to emigrate and wanted to learn all that was possible about

farming, both Laura's brothers, in turn, did a spell with the steam plough, horrifying

the other hamlet people, who looked upon such nomads as social outcasts.

Their ideas had not then been extended to include mechanics as a class apart

and they were lumped as inferiors with sweeps and tinkers and others whose work

made their faces and clothes black. On the other hand, clerks and salesmen of

every grade, whose clean smartness might have been expected to ensure respect,

were looked down upon as 'counter-jumpers'. Their recognized world was made

up of landowners, farmers, publicans, and farm labourers, with the butcher, the

baker, the miller, and the grocer as subsidiaries.

Such machinery as the farmer owned was

horse-drawn and was only in partial use. In some

fields a horse-drawn drill would sow the seed in rows, in others a human sower would walk up and down with a basket suspended from

his neck and fling the seed with both hands broadcast. In harvest time the

mechanical reaper was already a familiar sight, but it only did a small part of

the work; men were still mowing with scythes and a few women were still reaping

with sickles. A thrashing machine on hire went from farm to farm and its use

was more general; but men at home still thrashed out their allotment crops and

their wives' leazings with a flail and winnowed the

corn by pouring from sieve to sieve in the wind.

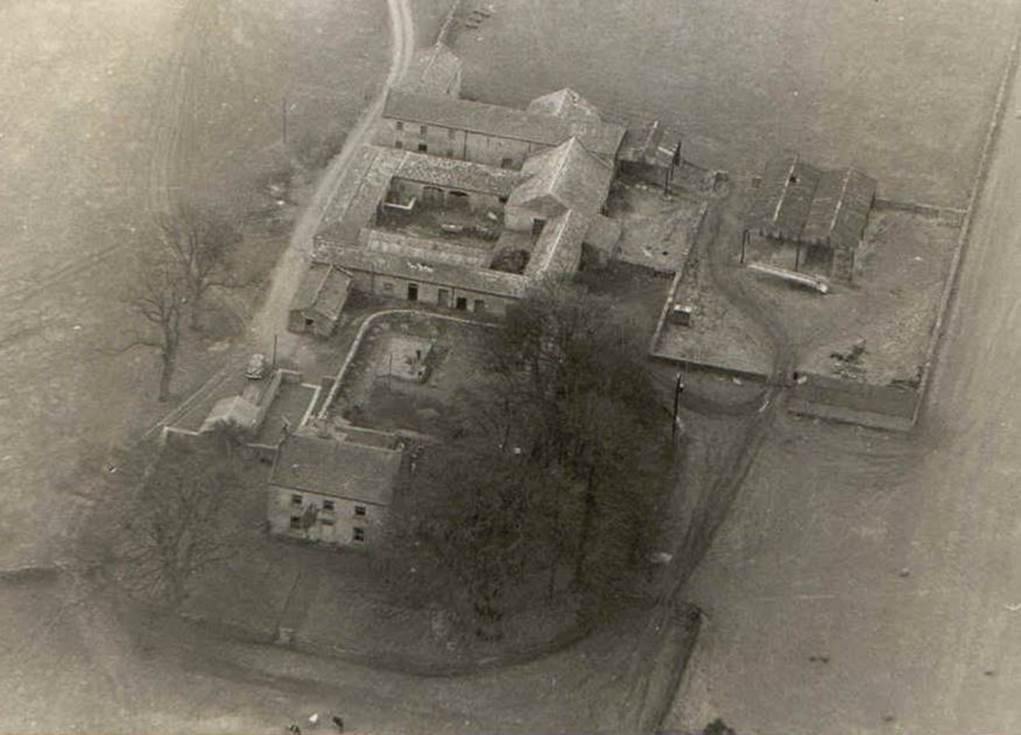

The path to modern farming

Gale

Bank Farm, Wensley where Alfred and Geoff

farmed.

Gale

Bank Farm

early twentieth century

Links, texts and books

|

|

|